9 minute read

THE VELVET MAFIA

Local author Darryl W. Bullock’s latest book celebrates the huge cultural contributions made by the gay men of the music industry during the Sixties pop boom

Bristol-based author Darryl W. Bullock has come a long way since penning his first piece for the Bath Chronicle more than 25 years ago. After a decade editing the LGBT section of much-missed local listings magazine Venue, followed by several years helming the West’s alternative lifestyles magazine the Spark, in 2015 he embarked on a career as an author.

Advertisement

Since then he has written several internationally acclaimed books, including David Bowie Made Me Gay, a century-long look at LGBT recording artists. His latest, The Velvet Mafia, follows the stories of the gay men who ran the recording industry in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s. Here he shares a little of the story.

The search outside the capital for a new sound

The British pop music industry really began in 1956, and was very much centred on London. From the very beginning, the industry was run by gay men: many of the managers, booking agents, record company heads, producers and songwriters who directed the careers of such icons as Cliff Richard, Shirley Bassey, Bristol’s own Russ Conway and Pensford-born jazz star Acker Bilk were homosexual. They had to be careful, because prior to 1967 it was illegal for homosexual men to have sex or even to chat up or dance with other men, but without the knowledge of the rest of the country the biggest names behind the scenes were working together, supporting each other and, in some cases, having affairs with other high-profile industry professionals.

London may have been the centre of the industry, but some people –including artist manager Larry Parnes and Gloucestershire-born producer Joe Meek – were looking outside of the capital for the next big thing. As the ’50s became the ’60s, the passion for American rock ’n’ roll was being replaced by a need for a homegrown sound: talent scouts were in and out of Bristol looking for bands, and although Bristol might not be the first place that people think about when looking at how rock and pop music has developed in the UK, it has played a significant role.

We all know about the city’s musical heyday in the late ’80s and mid-1990s, with Smith and Mighty, Tricky, Massive Attack, Roni Size and Portishead, but you can trace the lineage right back to the birth of rock ’n’ roll, if not before. Acts like Knowle’s the Eagles and the Kestrels were really busy during the first half of the 1960s, with international tours, recording sessions and film and TV work. Since then, Bristol and the surrounding towns and cities have given us everyone from Adge Cutler and prog rock pioneers Stackridge, to The Pop Group, The Korgis, Tears for Fears, Bananarama, the Blue Aeroplanes, the Vice Squad, Robert Wyatt, hit songwriters Cook and Greenaway and so many more. In a hurry to get to London, Cochran and Vincent rented a taxi, driven by George Martin from Hartcliffe, to take them

A turning point in pop history

By macabre coincidence an event that took place around Bristol marks a major turning point in the story of pop music. Eddie Cochran died hours after appearing at the Bristol Hippodrome in 1960, as part of the Larry Parnes-produced Anglo-American rock ’n’ roll package tour. Two of the people who shared a stage with Cochran that night were Tony Sheridan and a Liverpudlian singer called Johnny Gentle. Both were under contract to Parnes and both would play a significant role in the history of the most influential British act of all time, the Beatles. Sheridan, the first British rock ’n’ roller to sing and play his own guitar live on British TV, would become best known for the recordings he made in Hamburg with the Beatles shortly before they found fame.

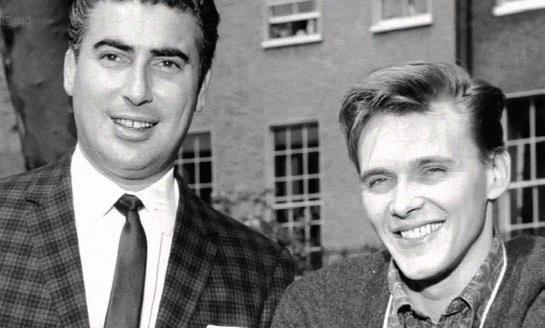

Parnes was the first manager in Britain to become as famous as his artists –the Simon Cowell of his day –with a stable of singers including Tommy Steele, Britain’s first real rock ’n’ roll star, Marty Wilde, Billy Fury, Vince Eager and others. He was also homosexual, a dangerous thing to be at a time when gay men were routinely arrested, fined or even imprisoned.

Their tour was due to take a break after a week of shows in Bristol, and Cochran and co-headliner Gene Vincent wanted to get home to America. Cochran was in a hurry to get to London, where he was going to meet up with Vince Eager before the pair flew to the States together, and Cochran and Vincent rented a private hire taxi, driven by

George Martin from Hartcliffe, to take them. Shortly after 11pm on 16 April 1960, their car set off from Bristol’s Royal Hotel (now the Bristol Marriott Royal, on College Green) for London Airport. Sadly, none of the passengers would make their flight. Less than an hour out of Bristol, Martin realised he had taken a wrong turn. On Rowden Hill, a notorious accident black spot near Chippenham, he lost control and the car spun backwards, hitting a lamppost. The impact of the crash sent Cochran up into the roof of the car and forced the rear passenger side door open, throwing him onto the road. Martin and tour manager Patrick Thompkins, who were in the front of the vehicle, were able to walk away uninjured. The three passengers who had occupied the back seat – Eddie, Gene and Eddie’s girlfriend Sharon Sheeley – were lying on the grass verge. All three were rushed to Chippenham Cottage Hospital, before being transferred to St Martin’s Hospital, just outside Bath.

Vincent had broken his collarbone, Sheeley was badly bruised and concussed, but Cochran was seriously injured and would not regain consciousness: he died in hospital in Bath the following day. A young police cadet, David Harman, was among those called to help clear the scene after the crash. Harman would later find fame as Dave Dee, front man of the hit group Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick and Tich.

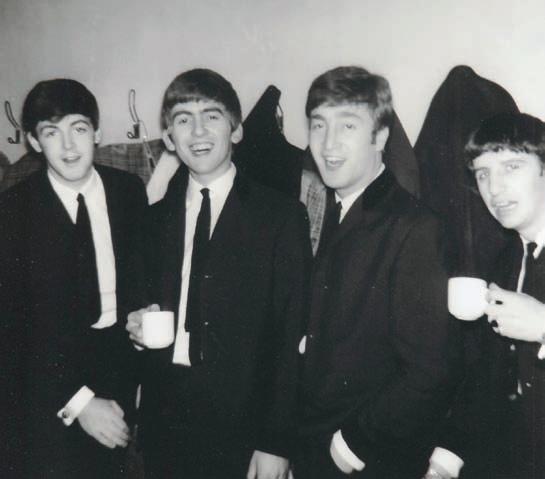

Three weeks after Cochran’s death, Larry Parnes auditioned the Beatles to act as the backing group to his big signing, Billy Fury. They did not win that booking, but he hired them to play with Johnny Gentle on a short tour of Scotland. All of the Beatles were fans of Cochran and Vincent, and lapped up Gentle’s tales of life on the road with the two big American stars. When the 17-year-old George Harrison discovered that Gentle owned the shirt that Cochran had worn on stage in Bristol for that last show he begged the singer to give it to him. The Beatles would later play Bristol several times: in November 1963, when they played at the former Colston Hall for the second time, Bristol vocal quartet the Kestrels were also on the bill. When they returned the following year their performance was flourbombed by four Bristol students.

Parnes had already made the acquaintance of a Liverpudlian furniture store manager, Brian Epstein, and a year later Epstein would become the Beatles’ manager. Parnes became something of a mentor to Epstein, who was also gay, although the younger man’s achievements soon surpassed Parnes’ own successes, and the two men would stay friends until Epstein’s untimely death in 1967.

Several years later Robert Stigwood, manager of Cream and the Bee Gees, would make a play to take over Epstein’s empire. Although the Australian emigree is probably best known as the multi-millionaire producer of such huge ’70s hits as Saturday Night Fever and Grease, he began his management career in Britain with Bristol dance troupe the Western Theatre Ballet Company, organising a tour of European and eastern Bloc countries. In 1958 the company became the first ever to have a performance filmed in Bristol broadcast by the BBC.

Bristol’s importance to LGBT politics

I’m now working on my next book, which takes a look at how Britain’s LGBT community has developed over the last half century, and Bristol plays a far bigger role in that story. There were very few LGBT venues in Bristol in the ’50s and ’60s; the best known would have been the Radnor Hotel on St Nicholas Street and Ship Inn on Redcliffe Hill, demolished in 1967, but by the early 1970s there were clubs including the Moulin Rouge in Clifton, King’s Club on Prince Street and the Oasis on Park Row. Freddie Mercury took the members of Queen to the Oasis after the band played Bristol Hippodrome in 1977, and the late Dave Prowse was once a bouncer at the Moulie.

Bristol’s importance to LGBT politics began in the early 1970s, with the establishment of a local chapter of the Campaign for Homosexual Equality, and very active gay students’ groups. In 1973 the National Union of Students held their first gay rights conference in the city, years before the Labour party fully committed itself to the advancement of LGBT rights. Bristol had its first gay festival in 1977 –a forerunner to the annual Bristol Pride – and this was held as a fundraiser for LGBT newspaper Gay News which was being taken to court for blasphemy.

The Moulin Rouge hit national notoriety in February 1976 when around 500 women convened in Bristol for the third annual National Lesbian Conference. The club had been hired out by conference organisers for their exclusive use, however the management of the venue neglected to tell their regular clientele. Conference attendees were enjoying an evening of entertainment, including live music from Bristol musicians, when a scuffle broke out between some of the women and several men who were told – in no uncertain terms – that their presence was unwanted. At least four women were injured, including one who had her jaw broken and another who was knocked unconscious. The altercation gave the police – who had raided the Moulie on several occasions – more ammunition in their fight to have the place closed down permanently.

In the mid-1970s, after Dale Wakefield set up the city’s Lesbian and Gay Switchboard, more pubs and clubs began to pop up, and in 1978 the Bristol Gay Centre opened in the now-demolished McArthur’s Warehouse, on Gas Ferry Road, although not everyone was happy about that. The vicar of a local church objected to a fundraising concert the Gay Centre wanted to hold at the Corn Exchange – which in those days hosted live concerts, boxing matches and all sorts –and the council revoked the license, but things were improving for the local LGBT community. By that time, of course, we had a whole new wave of LGBT pop stars: Elton John, Marc Bolan and David Bowie had all come out as bisexual, paving the way for the big LGBT stars to come, and by the mid-1980s music fans were becoming accustomed to seeing out-gay acts in the charts and on stage. ■

• The Velvet Mafia: The Gay Men W ho Ran The Swinging Sixties is out now, published by Omnibus Press

Harrison begged Gentle to give him the shirt Cochran had worn on stage in Bristol