5 minute read

Local news from chefs, restaurants and producers

Advertisement

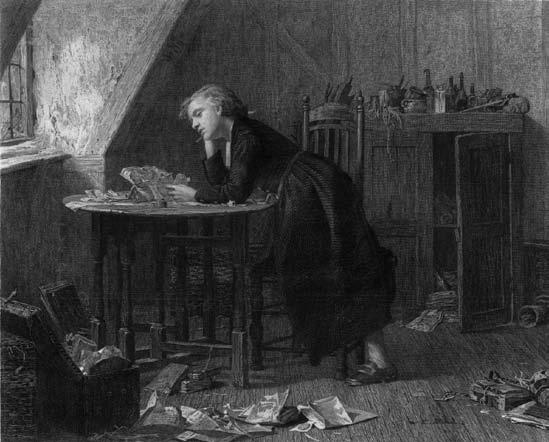

Chatterton's Holiday Afternoon engraved by William Ridgway after a picture by W.B. Morris – Bristol Reference Library

What’s left of the school that Chatterton attended, with the house (today’s café) behind it

pewterer, who was clearly interested in his forebears. Thomas was paid five shillings (getting on for £42 in today’s terms), for what turned out to be a hoax.

Considering what was to befall Chatterton, it is perhaps a surprise to learn he was a bit of a practical joker. In 1768 he appears to have conned the whole of Bristol with a faithful description ‘from an old manuscript’ (cough, cough) of the opening of Bristol Bridge (1248). More seriously, he tried to interest the playwright/publisher Robert Dodsley in his work before approaching another writer/publisher, Horace Walpole, in 1769, with a transcript of some 15th-century work (the so-called ‘Rowley Poems’, alleged to be based on the work of Bristol priest, Thomas Rowley), which convinced Walpole, prompting Chatterton to send a further batch of similar stuff, together with a sketch (C.V.) of Thomas’ own story. When the poems were examined by experts William Mason and Thomas Gray, however, they were declared ‘forgeries’. Walpole’s next letter to Chatterton was one advising the youngster to ‘stick to his calling’ (being a clerk presumably). If the allegations were true, Chatterton was not the first, or last, to try and pass off his own work as some lost gem from times past. Nevertheless, it was pretty impressive that a mere 15-year-old could nearly pull this off.

This episode seems to have precipitated the decline and downfall of Chatterton, who executed his last will and testament in April 1770, a mock suicide threat that had the happy consequence of getting him released from his hated apprenticeship (the whole episode was portentous). He then departed Bristol for London later the same month, although there was yet to be a false dawn. He arrived with his poems and possibly five guineas to his name (close to £1,000 today), taking lodgings in Shoreditch, and then Holborn. Not someone who over-indulged, and seemingly able to function with little sleep, Chatterton’s output was prodigious during this phase, as he rattled off all manner of stuff in machine-gun manner. There still seemed the chance that the golden child would come good and make his name and fortune in the city where the streets might just be paved with gold.

Publishers appeared to be flattering Chatterton at last. He obtained an interview with the Lord Mayor, William Beckford, and earned 11 guineas in just two months (what would be over £2,000 now). The budding poet sent home letters full of prospects, and even a box of presents was headed for Bristol. The turning point appears to have come with the sudden death of Beckford, who presumably had been akin to a promoter for Chatterton and other writers and publishers. The government also cracked down on editors who’d been publishing opposition polemics, including those of Chatterton. It seems there was a change of mood with publishers hunkering down, the work dried up and Chatterton soon diminished from a life of plenty to being penniless and without hope. Things became so desperate he even applied for a job as a ship’s surgeon, back in Bristol, although he had no medical training whatsoever. Unsurprisingly, he was turned down. His rent also increased: the timing was inopportune to say the least.

On 24 August 1770, 250 years ago, Chatterton locked himself away in his garret lodgings, shredded all his papers (manually you understand)

and then attended to himself. The following morning, the young poet was found, poisoned (opium and arsenic). He was laid to rest in the paupers’ pit of the Shoe Lane Workhouse. The Henry Wallis painting The Death of Chatterton depicts the scene. It seems macabre to have one’s suicide become a work of art, but then it was the single-most momentous event in the young poet’s being. It is worth nothing that some scholars of Chatterton believe his death may have been accidental, his cocktail of drugs being self-administered perhaps to try and cure himself of an STD (he was a philanderer by all accounts).

Another artwork, Chatterton’s Holiday Afternoon (an engraving after a picture by W.B. Morris) appears to show the same garret lodgings, but in happier times, ‘leaning on a table deep in thought’, with the writer’s detritus strewn about. The reference to ‘holiday’ might suggest it was a happy interlude in a troubled life, or that Thomas’ sojourn in London was intended to be temporary before he returned to his family in Bristol. For his mother and sister, the death of Chatterton must have been a grievous blow – the loss of not just a son/brother, but also a potential provider as his career took flight. He was a victim, some say, of the materialistic society of the time, who fell prey to starvation and despair, so his story evoked romanticism and inspired the Romantic poets who would follow. He found his inspiration back in the 15th century: perhaps, to him, it was a purer, simpler age.

The debate about Chatterton’s Horace Walpole manuscript raged on after his death for 80-odd years and would not finally be put to bed until Walter Skeat wrote his Chatterton (1871), in which he concluded that the bogus ‘early English’ had been ‘the boy poet’s own invention’ (in other words the Rowley Poems were a forgery). It seems Chatterton, talented as he was, continued to play the confidence trick beyond his rib-tickler regarding Bristol Bridge. He left a legacy though, as his life and work inspired Wordsworth, Coleridge, Keats, Southey, Shelley, Robert Browning and Rosetti among others. ■ “Chatterton … is the purest writer in the English Language.” (Keats) “The marvellous boy, the sleepless soul that perished in his pride.” (Wordsworth) “Not to know Chatterton is to be ignorant of the true day-spring of modern romantic poetry.” (Rosetti)

• Chronology 1752 – Birth of Thomas Chatterton in Bristol (20 November). 1760 – Chatterton attends Colston’s bluecoat hospital (until 1765). 1762 – The first poem written by Chatterton, On the Last Epiphany. 1763 – First poetry published in Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal. 1764 – Elinour and Juga, the first of the ‘literary mysteries’. 1767 – Paid five shillings for a pedigree of the De Bergham family. 1768 – Chatterton hoaxes the whole of Bristol with Bristol Bridge story. 1769 – Walpole receives Chatterton transcript, later declared a forgery. 1770 – Death of Thomas Chatterton in Holborn, London, aged 17. 1803 – Work including ‘Rowley Poems’ published by Southey & Cottle. 1871 – Skeat publishes Chatterton declaring ‘early English’ bogus.