25 minute read

EDUCATION

BRISTOL UPDATES

NEWS FROM LOCAL BUSINESSES AND COMMUNITY ORGANISATIONS

Advertisement

xxx

REDUCING THE IMPACT OF POVERTY

Bristol’s only baby bank is asking for support due to a surge in demand as a result of Covid-19. Volunteer-run Baby Bank Network collects and re-distributes pre-loved items to women and children fleeing domestic and sexual abuse, families coming out of homelessness, refugees and low-income families.

The charity – also in need of donations to buy items that cannot be re-used, such as cot mattresses and bottle teats – was helping almost 170 Bristol families every month before lockdown, supplying bespoke bundles of essentials to those who could not afford them. Then, incoming items stopped, fundraising events were cancelled and regular giving was reduced as families tightened their belts, and it became clear than an emergency response was desperately needed. “We help, on average, 40 vulnerable women and families every week and for us to stop our service meant many had to go without basic supplies,” said co-founder Becky Gilbert. “Naturally more families will need our help as more people are pushed towards poverty. These could be anyone; your neighbours, friends and family members. There is a huge backlog of referrals, we have reduced warehouse space due to distancing guidelines and our volunteer capacity is greatly reduced.”

Donations of big-ticket items such as prams and cots are greatly appreciated; check the website and Twitter feed for up-to-date requirements.

• babybanknetwork.com

THE BEAUTIFUL SOUTH

South Bristol Enterprise Support – a new service for local residents and businesses – launched over the summer for those looking to start a business, and existing businesses looking to grow. Bristol City Council is leading the partnership with Knowle West Media Centre, The Princes Trust, School for Social Entrepreneurs, and YTKO Ltd.

Existing small and medium-sized enterprises and residents based in the area could be eligible for support from providers who have expertise in a range of areas including business training and mentoring, supporting young people in enterprise and digital manufacturing. The support offered includes pre-start up training packages, bursaries, access to workshops and digital manufacturing technologies at Knowle West Media Centre’s creative innovation space The Factory, plus support with product development, business coaching, a review of the business needs and specialist support.

“Working collaboratively with key city partners is going to be vital to the recovery of Bristol, and SBES will help to help people from all walks of life who have brilliant ideas to turn them into thriving businesses,” said mayor Marvin Rees.

Penny Evans, strategic lead for Knowle West Media Centre, The Factory, added: “We’ve been based in South Bristol for many years and we know that there is talent and creativity in abundance here – but many people haven’t had the opportunities or support to realise their ideas. We’re looking forward to supporting people who want to become part of a growing community of maker businesses – no previous experience of digital manufacturing or design will be required!”

The project will support any sector of business but will include specialist advice for construction, digital and food businesses. It will also provide specific support for young people, social entrepreneurs and women. Plaster Creative Enterprise, a South Bristol based marketing business, is providing support to promote the project across South Bristol. • sbes.org.uk

A LIFE-SAVING LEGACY

The defibrillator is now accessible to the public

Weston RNLI lifeboat station now has a publicly accessible heart defibrillator thanks to the generosity of the family of one of its previous crew, Brian Ward. A long-serving crew member at Weston RNLI station, Brian arranged for a defibrillator to be installed some time ago as, while volunteer lifeboat crew are highly trained in casualty care, a stopped heart needs more than sophisticated first aid.

So that the station would be able to cope with cardiac arrest, Brian arranged with the British Heart Foundation, after some research, to acquire one. It was installed in the station but because it was not protected from vandalism it was placed inside the boathouse doors which meant it was only available when crew were in attendance. Brian sadly passed away in 2019 and a year later his family held a remembrance day, raising enough money for an external cabinet for the defibrillator – now fixed in place at the station on Knightstone Plaza so anyone who needs the defibrillator can use it to help save someone, even if the crew are not in attendance. “Brian Ward was a stalwart of our crew,” said Mike Buckland, lifeboat operations manager for the Weston crew. “He was always trying to help people, hence him arranging for the defibrillator to be acquired. His family have been tremendous in helping us fund the cabinet to make it publicly accessible.” • rnli.org

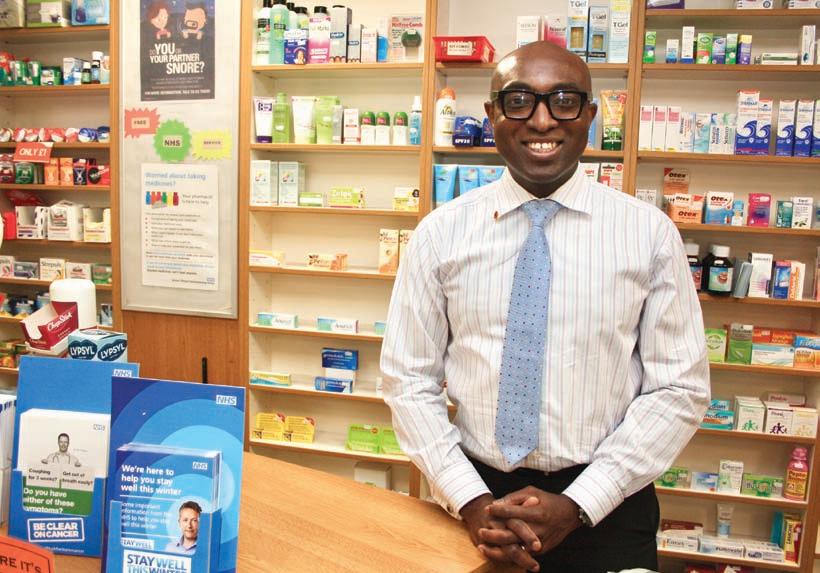

A dose of community, care and kindness

Ade Williams, lead pharmacist at Bedminster Pharmacy, community champion and brilliant ambassador for Bristol, speaks on health injustices unveiled by the pandemic, and the importance of keeping up with self-care as we head into autumn

The broader cost to society of the pandemic is becoming more evident. In the face of what has seemed like an inexorable threat to our physical and mental wellbeing, many of us have unconsciously morphed, and these accelerated changes stemming from Covid-19 have sometimes even eclipsed the virus itself.

Injustices are being laid bare as this ill wind blows away the cloak of camouflage, revealing that even in our shared experiences, social injustice means race, gender and financial status unfairly sets some people up to suffer much more.

Recent Office for National Statistics (ONS) data shows that the proportion of people in the UK suffering with depression has doubled during the Covid-19 pandemic, with stress and anxiety being most commonly reported. With daily reports of job losses –pulling the rug from under already hard-pressed families – ongoing unplanned life disruptions and our increasing lack of confidence in leadership, it can sadly feel relentless.

Amid this onslaught, here are some much needed useful tips on how to boost mental wellbeing:

• Look after yourself. Where possible, try to maintain a daily routine and prioritise your wellbeing and mental health. Caring for others and the burdens of balancing life and work can take their toll.

Remember this always: Seeking help is not weakness. • Stay connected to others. Keeping in touch with your friends and family as well as and checking in on others, especially those more vulnerable, is very important. • Talk with children. Be aware that children, even those who are very young, can tell when something is wrong. The changes in our behaviour, the impact of stress/exhaustion and most certainly the absence of some familiar faces and places will leave them puzzled and, many times, even scared. Take the time to talk with them and provide age-appropriate support to help them cope. • Only access health information from UK health organisations and reputable sources. Please avoid continually monitoring the news and social media feeds. Misinformation and inaccurate reporting cause much confusion and panic. The Coronavirus Support App (UK) created by a team of over 40 UK health professionals led by award-winning

Bristol GP Dr Knut Schroeder is certainly worth downloading.

• Act responsibly. We all have a vital part to play: wearing masks, getting tested, socially distancing, self-isolating if necessary, adhering to hand hygiene, to name a few things. Please have no doubt, your actions will not only directly impact others but may even ultimately keep them alive.

Profoundly our collective courage has driven us to seize hold of and share hope across the city, resulting in extraordinary acts of kindness. We proactively find ways to support each other while restoring dignity through our generosity.

As an NHS professional, I know that the values shared by all colleagues include the convictions that our work is life-affirming and enhancing. Amid this upheaval, the visible demonstrations of how we have always gone about this captivated Bristolians. We are not heroes; this is our community, our city, home to our friends, neighbours and loved ones.

Please be assured that our care and expertise remains available and accessible. To keep us all safe, things may look different; likewise, the processes followed or used, but please do not ever hesitate to contact us if you need to. Together we will get through this. ■

Lawrence Hoo (image: CARGO Movement)

Shagufta Iqbal (image: Kiran Gidda)

Caleb Parkin (image: Paul Samuel White) Connor Macleod (image: Ray Roberts)

Rebecca Tantony

Poetry in motion

The art form may have been deemed temporarily expendable by Ofqual but in Bristol it’s never been more alive and well, enjoying a “brilliantly energised” renaissance as it moves forward – a tool for learning and accessible means of expression

There’s a lot going on in the world of spoken word this autumn, starting with citywide celebration marking the 250th anniversary of the death of prolific pre-Romantic poet Thomas Chatterton (the Redcliffe resident who died by suicide aged just 17, see p32). Exploring the legacy of the young literary figure, the Bristol Cultural Development Partnership project will be building on knowledge of his life and times and bigging up our vibrant, diverse poetry scene as it stands today.

But that’s by no means where things end. Here in Bristol, poetry is experiencing a resurgence not only as a popular creative art form – with our third official city poet ready and waiting in the wings to take over from Vanessa Kisuule – but also as a choice educational tool outside of traditional curricula. Over the summer, filming took place for CARGO Classroom – a new set of audio-visual teaching materials created from a collection of award-winning poet Lawrence Hoo’s writings, seeking to bring balance to history syllabi and traditionally one-sided learning around subjects such as the transatlantic slave trade.

The creative collective behind it, CARGO Movement, develops digital heritage resources for schools and the broader public – evocatively celebrating the resilience and visionary leadership of Black individuals who catalysed change and moved society forward. Its founders have long been dedicated to broadening Bristol’s understanding of its history and living legacy, putting forward missing narratives from our past and inspiring visualisation of a future full of pride and possibility. The first Classroom iteration, delivered with One Bristol Curriculum, Arts Council England and creative partners including pioneering, globally celebrated Bristolian band Massive Attack, will take the form of a set of downloadable history lesson plans for Key Stage 3 teachers. Not only innovative in their spoken word and audiovisual format, inspiring creative participation from learners, the interactive online features are innovative in their broadening of perspectives.

Elsewhere, more and more spoken word collectives are sparking into life locally – those who converse in verse often using social media to link like-minded stanza fans – and some of the best Bristol wordsmiths are steadily gaining higher profiles. It all seems a little out of step with the recent news that poetry is to be made an optional element of GCSE English literature, and later in this feature we ask a handful of our many fabulous local poets for their thoughts on the news.

Citywide celebration

In the meantime, A Poetic City – now likely to be extended into early 2021 – is set to inspire writers of the future. Woven into the programme are contemporary themes such as the nature of celebrity; fake news and fake art; ongoing barriers to accessing culture in the city; arts and mental health; artistic credulity and credibility; and the resurrection of the Gothic. Keep an eye on Festival of Ideas’ website (ideasfestival.co.uk) for readings, events and workshops led by Lyra, Bristol’s new poetry festival.

Two new publications about poetry have also been produced and will be distributed for free across the city in October – one, a comic telling the Chatterton story, and the second an anthology with 13 new poems, seven by Bristol-based poets, responding to Chatterton’s life and legacy.

Romantic Bristol: Writing the City will see two new layers to its free smartphone app, and there are plans for a new interpretation scheme for the Chatterton room at St Mary Redcliffe as well as a Chatterton sculpture commission, plus tourism content on the theme of literary Bristol and a range of panel discussions, walking tours and symposiums.

Four writers-in-residence have also settled in for stints at the RWA, St Mary Redcliffe, Red Lodge and Glenside Hospital Museum. Shagufta Iqbal is the poet taking up the challenge of absorbing the archive materials at the latter – the former Bristol Lunatic Asylum, where a suicide awareness programme is also being rolled out – in order to form a creative response centred around poetry and mental health. In among work on her debut novel, new poetry and podcasts for Kiota Bristol – a collective for creatives of colour – busy Shagufta will be Festival of Ideas’ writer-in-residence at Glenside until November, with a commissioned work due to launch on World Mental Health Day (10 October) with a series of sharings and a workshop (check glensidemuseum.org.uk). They’ll present an opportunity to engage in the long history of Bristol and mental heath and a conversation on wellbeing, particularly in relation to the pandemic. Bristol has, time and time again, shown itself to be a city that really is about its communities, says Shagufta, whose aim is to create a space where people can come together and offer support to one another.

‘Day-glo queero techno eco poet and facilitator’ Caleb Parkin is another commissioned to commemorate the Chatterton anniversary. Tutor for Poetry Society, Poetry School and First Story, he takes over as Bristol’s third city poet in October and will mark the start of the new tenure with an energetic verbal manifesto before performing a second commission at Marvin Rees’ State of the City address – a sensitive piece reflecting on what a strange, difficult and – for many – traumatic year 2020 has been. “There are big questions around now and I think poetry’s place isn’t to answer them,” says Caleb. “It’s more important poems invite discussion about complexity, nuance and possibilities – about what makes each of us different, as well as what connects us.”

Curriculum vital

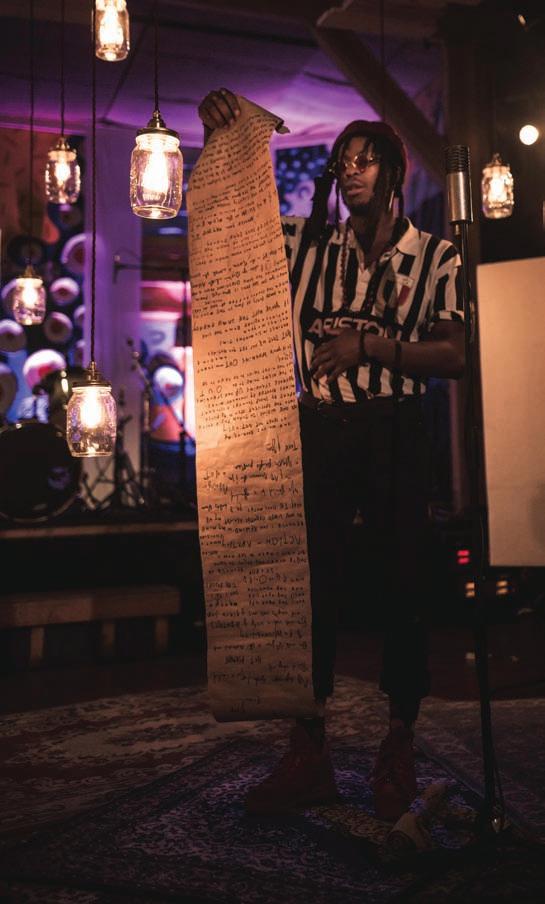

It’s why the subject has an importance place in formative education, as many local poets agree. We spoke to Caleb, Shagufta and Lawrence, along with Rebecca Tantony – writer-in-residence at St Mary Redcliffe –poet and musician Solomon O.B – also UK Slam champion 2016 and TEDx and UNICEF speaker – anarchic ‘stand-up poet’ Connor Macleod, and Tjawangwa Dema – poet, teaching artist and honorary senior research associate at the University of Bristol’s Department of English –about their views, experiences and different paths through poetry.

TBM: What was your own experience of poetry in the classroom?

Caleb: Poetry definitely resonated with me, as a wordy, sensitive child. For me, poetry has felt like a way of honing my chattiness into an art form, seeing what squidging language into different shapes can do. At GCSE, I wrote a book of poems and the process really confirmed that poetry had a special place in my creative and inner life. If I hadn’t been offered that space to write, explore and develop, I might not have ended up carrying a notebook around with me ever since… Lawrence: I don’t recall having an interest in poetry in school. I used to love writing stories in primary school but my handwriting, spelling and grammar was poor. I was made to hold a pen between my thumb and forefinger when I naturally held it between my forefinger and middle finger. This led to me losing interest in English and storytelling. Tjawangwa: I studied in Botswana and in the classroom it was the reading of stories that drew me to language, not poetry, specifically. That said, outside of the classroom I heard (not read) poetry with some regularity. It impressed me and impressed upon me an appreciation for

how a stranger’s story can resonate personally. At university, I suddenly recognised this educational gap and wished I had been exposed to poetry earlier; its absence/sporadic presence made the climb much steeper. Connor: I loved poetry analysis as a kid. The only nickname I ever got in school was as a direct result of my passion for poetry analysis – my classmates called me Death Metaphor because I could usually argue that any particular image in a piece was somehow a metaphor for death and decay. I really resonated with this analysis and it sparked my interest in more general literary analysis which is now what I do for a job.

If we want young people to feel able to cope with uncertainty, differences of opinion –inquiring about the language around them –they’ll need poetry as much as trigonometry

Solomon: I struggled to relate to a lot of what was on the curriculum. So much so that in year nine, I asked if I could read the lyrics to Plan B’s Charmaine in place of some Shakespeare. We were reading about a love affair gone wrong. Clearly I saw more relevancy in the music I was listening to than what we were prescribed. I got onto the pathway of

poetry through rap and to this day I would say I’m more influenced by rappers than I am by poets – though that is changing of late. It’s the dexterity of what you can do at rap speed, the messages you can communicate, the energy you can convey; it’s such a powerful instrument. Then I slowly found there was more room to speak and really be heard in spoken word context. That opened me up to the importance and potency of words, when used right. Buddy Carson gave me my first ever poetry set – 2016, pub in Bedminster. That was followed with Malaika Kegode with Milk Poetry. Rebecca Tantony was always a really encouraging presence, when she was doing Hammer & Tongue Bristol. Her and Thommie Gillow were probably happier than me when I grabbed the national title! Zena Edwards was a big influence in my early development. She mentored me for around six months and that laid a lot of foundations to progress to the next level of being a performer. Shagufta: It was Bristol Black Writers that gave me the incentive, encouragement and confidence to imagine myself as a poet – without which I would not have found this love as quickly as I did. I owe Kuumba and the Bristol Black Writers an immense gratitude for providing an environment that nourished my curiosity about poetry. I also spent many years running workshops with Glenn Carmichael with the Poetry Slam, and learnt so much about performance and audience engagement from him. Bristol really will miss his commitment and drive for poetry.

Are you concerned about Ofqual’s decision?

Shagufta: It’s heartbreaking, of course. Now, more than ever, we have seen how much the arts have given people light in a very difficult time. Lawrence: Poetry is having a renaissance, connecting with diverse communities and voices who are embracing it. If ever there was a time to increase poetry’s use within the curriculum to engage and educate, you would have thought that time was now. Solomon: I am. But it falls in line with a society that has, for a long time, only placed value on certain types of intelligence. IQ, intellect. Emotional intelligence, awareness, spatial intelligence, other ways of being sensitive to the world don’t hold the same weight. But we are about to see a real shift in this. The value of being able to decode emotion and feeling and our relationship to body and mind is going to change in line with our environment. There will be a lot of suffering otherwise. Connor: Oh, Ofqual’s decision is diabolically wack. You wouldn’t make algebra an optional part of GCSE maths, would you? That being said, it completely makes sense. Education in our country has less to do with letting kids explore the world as they wish, and more to do with creating productive workers. The sciences are more employable than the arts, so of course the government is going to atomise the curriculum as a means of minimising our kids’ exposure to anything that isn’t going to get them a ‘proper job’. Tjawangwa: At the least, it is a narrow, ungenerous educational model. At worst it suggests a precursor for a model with dangerously low regard for what poetry and creative thinking offers us as human beings and the way this is connected to our capacity for thinking critically and empathetically. It is unfortunate timing for many reasons. This decision comes just as Arts Council England and the London School of Economics

Some poets, such as Solomon O.B – pictured performing at AiDU’s Live from the Jam Jar session in St Judes – find their entry point into the form through musical genres such as rap and hip hop (image: © AiDU) explore flagshipping SHAPE (social sciences, humanities and the arts for people and the economy); a practice-shaping acronym to hold up alongside the much more familiar STEM. But I suppose poetry is always having to prove itself – is it dead? Is it thriving? Is it valuable? Is this form ‘real’ poetry? Even in this current moment where poetry has done a fine job of ‘proving’ its attraction to and its position as a go-to for those who are faced with life events they are struggling with distilling or reconciling with their humanity, it now has this hurdle, too, to overcome. Look,

‘everyone’ engages with poetry and what this moment has taught us is that it is a life skill rooted in self-expression, it’s not merely the preserve of the elite or literary practitioners. We all benefit from a relationship with it. We know this, though the children might not yet. Poetry was here before all of us who are alive to read this and will be here after us so I’m not concerned about it as an art form. But yes, education is all the poorer for not remaining fully and consistently in conversation with poetry. My fear is that when we take steps towards removing subjects like poetry from publicly accessible and mainstream education they are lost to those who can little afford to access them any other way. Caleb: The government has said it’s just for one year, to alleviate pressures teachers and young people are under because of the pandemic. My understanding is that teachers can choose to drop one area: poetry, 19th-century novel, or post 1914 fiction and drama. But I suspect many pressured teachers would drop poetry, as many find it difficult to teach. As a thought experiment, what if they’d made one of the sciences optional instead? (I’m not denigrating other subjects and actually think cross-curricular work should be the norm.) Perhaps capacity did need to be freed up in the curriculum, but it’s interesting that poetry was viewed as the most expendable. At a time when young people were facing huge challenges already, compounded by the pandemic, and with the UK poetry scene so brilliantly energised, why drop it now? Poetry is where we go to work with language and explore ideas, that little container of words which can become a creative arena for discussion – not just a utilitarian tool for instruction manuals and legal documents (although they’re both great styles to play with in a poem). If we truly want young people to feel able to cope with uncertainty, ambiguity, ambivalence, differences of opinion – to be critical and inquiring about the language around them –then they’ll need poetry as much as they’ll need trigonometry.

Students shine, where they have otherwise been written off; the quietest transform into magical storytellers. Poetry allows us to offer the most distilled versions of our truths

Is it easier and more effective to keep poetry alive and relevant to young people outside the classroom than in it?

Connor: You could say that about any subject. Physics is a lot more exciting in BBC documentaries about the birth of the universe than it is in classrooms where you spend an hour attaching bulldog clips to lightbulbs and batteries. That isn’t to say that poetry can’t be living and relevant within classrooms, but it’s about blurring the line between the two –taking kids to poetry events, booking poets to run workshops. Poetry will always continue and remain relevant, but without its introduction into classrooms and workshops, many kids may never give it a go themselves. Rebecca: As a teenager, the poets I studied in school rarely had that resonance with me, because they weren’t contemporary and therefore relatable or igniting new reference points for the world I inhabited. Yet the language of music did offer that – listening to hip hop was my introduction to poetry and through that the recognition of craft, technique and the power of storytelling. In that sense, you could argue that poetry is something alive and relevant outside the classroom, but surely it’s about finding those ways to expand learning beyond what we think it is and where it should be found. Poetry and spoken word can offer a transformative entry point into understanding who we are, and the world around us. What better education is there than that? Solomon: It happens every day. In the charts (quality questionable), in lyrics all over. In conversations on the street without people even realising it. Poetry is alive as long as language is. Shagufta: Poetry should be part and parcel of classroom education – it encourages imagination, play and confidence with how we use language. Cutting it out, even if temporarily, at this crucial time where we are having to re-navigate the world, is a terrible decision. Caleb: It’s both/and, not either/or. We need more poetry, not less – it should be kept alive in a way that teachers and students can find inspiring within the classroom. And it should be kept alive in the classroom to honour to the fact that it will – as an ancient art form and fundamentally human means of connection – inevitably be kept alive outside of it. Tjawangwa: I do not believe this is an either/or scenario – we’ve lost already if we view it that way. Instead, it is a collaborative project that views the classroom and life spaces outside the classroom as a looped continuum. The spaces must speak to each other.

Are you inspired by poets of the past? What is their classroom value?

Tjawangwa: I’m quite shameless about my preoccupation with multiple influences and voices regardless of era. I follow the work and the questions the work asks, or answers, or ignores. I often worry if, and where, the work of certain poets is excluded. I believe strongly in a growing, responsive canon that remains open to reflection and builds and dismantles itself accordingly. In the context of a canon like this I think ‘poets of the past’ would have much to offer us. In isolation, or to the exclusion of newer, or under-represented voice, they undo or skew ideas of who is capable of producing, and what counts as, great poetry. Connor: Poets and poems from the past are, of course, useful texts for exploring an evolution in language, theme and imagery as it pertains to a shifting historical context. Certain poems like First They Came ought to be essential pieces to discuss as a classroom for at least a lesson. I’m much more inspired by my contemporaries than historical poets, but I have written pieces directly inspired by classic work such as T.S. Eliot’s Lovesong of J. Alfred Prufrock before. Caleb: For me, John Donne was a contemporary thinker in the 16th century. Sometimes it feels like his poems reach across those centuries and right into my thinking, right now. But for me, the ‘canon’ as it’s currently thought of is too narrow. It tends to be a very particular demographic (ie, privileged white men) because other voices weren’t equipped to write poems, or didn’t have them documented for posterity. That’s not the case now and poetry can and should offer a much broader view. The curriculum should be truly representative, allowing teachers to make their own decisions about what will engage students. Educators might bring in poetry from across centuries to demonstrate how themes and ideas can be shared, the ways we’ve changed and, perhaps, made progress... Solomon: I am as I grow more into poetry. Khalil Gibran, Rumi. Poetry in scripture is full of amazing imagery and phrasing. I think that’s the main value it holds for me. The language and approach of a time past. We speak in a different tongue these days. It’s nice to hear the world framed in a different voice and it opens up some of the universal more for me. The eternal that was articulated as clearly then as we ever could now.

Is it important to keep introducing modern poetry in the classroom and have a diverse offering rather than just revering the past?

Shagufta: 100% – art should relate to its audience and the experience of its audience. While there are works that are timeless in their themes, it is important for young people to feel their experience/perspective is part of the poetic discourse. Otherwise poetry can seem an insular and exclusive world, and it has had a hard time trying to shake that image of itself. Connor: It’s essential to bring modern poetry, especially modern local poetry, into classrooms. It’s all well and good giving students Auden and Owen to pick apart, they are hugely influential writers after all. But without modern poetry or even poetry being written within the student’s lifetime, poetry can sometimes feel like this dead thing, an archaeological subject. It’s also vital to showcase Black poets in the same vein. My experience with Black poetry began and ended at Benjamin Zephaniah’s Talking Turkeys. I wouldn’t find out about famous contemporary Black poets like Maya Angelou and Akala until well after I left school. Solomon: As much as classic works should be admired we have to constantly update and use language to decode our times. Our selves. Young people need to have access to their own sense of language to connect to poetry. Otherwise the disconnect is quick. Tjawangwa: Absolutely. This I think has everything to do with why