Marketplace

Where Christian faith gets down to business

A shelling solution

Ghanaian firm reduces drudgery for women ground nut farmers

Why does MEDA have an investment fund?

When selling a family business makes sense

Ember builds on Indiana family RV tradition

Are worker shortages linked to burnout?

Talking about family business succession

Business transition is the subject of several stories in this issue.

Ashley Bontrager Lehman dreamed that one day, she would head up Jayco, the Indiana recreational vehicle firm started by her grandfather. While she rose to become director of marketing at Jayco, the firm was sold in 2016 for $576 million.

That might have ended her dream of running an RV company. But in 2021, she and several partners started Ember, a new RV firm (see pg. 14).

In some cases, selling a family business makes more sense than trying to pass it on to the next generation. That was the case with Excel Industries, as Bob Mullet explains (pg. 16). The $375 million sale of Excel to Stanley Black & Decker enabled more than $100 million in charitable giving and provided an exit for many people who didn’t work for Excel and had been holding an illiquid investment.

Farm families are not immune from this dilemma, Lance Woodbury says.

Woodbury is an adviser to family-owned and closely held agriculture businesses and is a partner at Pinion, a leading US agricultural consulting firm. He also facilitates several agricultural peer-group initiatives and writes a family business column for DTN/ The Progressive Farmer.

Farms end up being split up or sold when family members have different ideas on how the business should be run or aren’t interested in participating, he suggests (pg. 18).

A young mediator

A lot of Woodbury’s work over the

course of his career has been just getting people involved in family businesses to talk to each other. That passion for mediation and reconciliation started at a young age.

Woodbury spent his formative summers in Western Kansas on a family farm that was run by his two uncles. He lived with his grandparents and was puzzled to “observe my two uncles not speaking to one another and farming right next to each other.”

So at age 14, he engineered a family meeting, renting a conference room in Goodland, Kansas, “sort of shaming them into getting together.”

Time for more conversations

More conversations about the future need to occur in family businesses, and soon.

PWC’s 2021 Global Family Business Survey found that only 30 percent of family firms have a formalized succession plan. That study surveyed over 2,800 people

on five continents.

Score.org says that 47 percent of family business owners expecting to retire in five years do not have a successor.

Will those facts lead to a wave of family business sales in the latter half of this decade? There is no clear answer.

Three-generation myth

Many articles about business succession suggest that about 40 percent of family businesses transition to a second generation, 13 percent to a third generation, with only three percent surviving to a fourth generation or beyond.

But those statistics lack modern context and have perpetuated a three-generation myth, the Harvard Business Review suggests.

The oft-repeated numbers come from a 1980s study of 200 Illinois manufacturing companies between 1924 and 1984. “On average, family businesses last far longer than a typical public company does,” the HBR article states.

Companies in which two or more family members exercise control reportedly account for half of US employment and gross domestic product.

But others give some credence to the three-generation notion. The 2018 PWC Global Family Business Survey found that the threegeneration rule of a business family going from shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations “remains a significant reality.” .

2 The Marketplace May June 2023 Follow The Marketplace on Twitter @MarketplaceMEDA Roadside stand

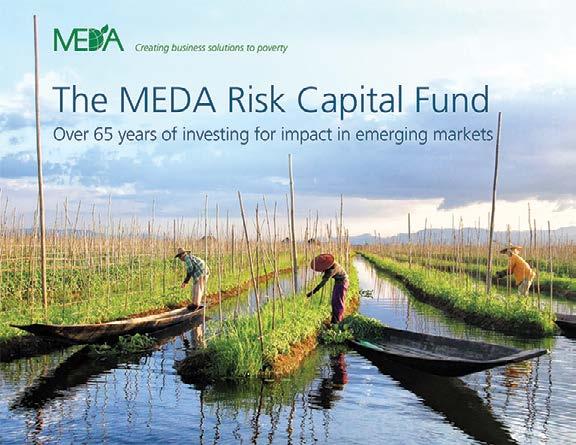

A history of investing for a better world

Fanning the embers

7 Features 14 16

Ashley Bontrager Lehman’s dream of heading an Indiana RV company was realized differently than she originally envisioned.

When it’s time to sell the family firm

Bob Mullet thinks his father, Roy, would be pleased with the sale of Excel Industries, and the amount of money that ended up going to charities as a result.

Investments have been part of MEDA’s DNA since its inception. The MEDA Risk Capital Fund has changed with the times. It is now being aligned with MEDA’s strategic goal of creating decent work for 500,000 people. 19

Addressing the burnout epidemic

Helen Hayes sees a link between worker shortages and employee burnout. She also has ideas on how to address the problem.

Shorter good

22 Roadside stand 24 Soul Enterprise 22

reads

Books in brief

In this issue

3 The Marketplace May June 2023

12

Ashley Bontrager Lehman heads Ember RV.

Dunyiya Enterprise provides jobs for women and mechanizes ground nut shelling.

Photo by Farida Latif/MEDA

Compensate Biblically

This chapter, “Habit 20,” is excerpted from Darren Shearer’s forthcoming book, The Christ-Centered Company: 37 Biblical Business Habits to Build a Thriving Company That Honors God and Blesses the World.

The book discusses real-world best practices and practical biblical commentary for all 37 “habits” surveyed in the accompanying Christ-Centered Company Assessment That assessment enables firms to measure the extent to which their company culture and habits are consistent with biblical teaching.

The Christ-Centred Company will be released in June by High Bridge Books.

Behold, the pay of the laborers who mowed your fields, and which has been withheld by you, cries out against you; and the outcry of those who did the harvesting has reached the ears of the Lord of armies.

—James 5:4

For the Scripture says, “You shall not muzzle the ox while it is threshing,” and “The laborer is worthy of his wages.”

—1 Timothy 5:18 Whatever is right, I will give to you.

—Matthew 20:4

How much should we pay our team members? What is your company’s overall compensation philosophy?

Quoting Leviticus, Jesus said, “The laborer is deserving of his wages” (Luke 10:7). But what should your team member’s “wages” be? What are God’s standards for employee compensation?

Let’s start with some basic best practices and then move into some more theologically complex matters of financial compensation.

Pay on time.

When Jesus says, “A laborer is worthy of his wages,” it would be a stretch to interpret this as Jesus meaning, “Laborers should be

paid more than they are currently earning.” This is not really an argument for raising the minimum wage, inciting labor strikes to raise wages, etc. Instead, it seems Jesus is saying workers are worthy of the wages they agreed to work for. This also means those agreed-upon wages should not be withheld but should be paid promptly as the work is performed. Withholding wages was a wicked habit more common in the first century when it was easier to get away with than in modern societies, but it still happens today.

Taking advantage of people’s efforts is something God takes very seriously. James rebukes employers who withhold wages, saying, Behold, the pay of the laborers who mowed your fields, and which has been withheld by you, cries out against you; and the outcry of those who did the harvesting has reached the ears of the Lord of armies.

(James 5:4)

Regardless of the wages you and your team members have agreed upon, ensure they are paid promptly.

Does this mean employers are living up to God’s standards of proper compensation by paying less than market rates as long as they pay on time? Let’s explore.

Pay at least a livable wage.

In Matthew 20, Jesus shares a parable about a group of day laborers who were hired at various points throughout the day to work in a vineyard. Some were hired at the beginning of the day, another group at “about the third hour,” other groups at “about the sixth and ninth hour,” and yet another at the “eleventh hour.” Although they came to work at different times, the master paid all of them a day’s wage (i.e., a denarius).

The master said to the workers who went to work at the sixth and ninth hours, “Whatever is right, I will give to you” (Matt. 20:4).

The master recognized that all his workers would need to keep up with their own living expenses, so he decided it would be “right” (i.e., just) to make sure they all received

4 The Marketplace May June 2023 Soul Enterprise

Our company pays our workers at least a livable wage, pays them on time, and pays most of them above market rate for their positions.

a full day’s livable wage, regardless of what time they were hired.

Don’t expect a day’s work if you can’t or won’t pay a day’s wage. If your company simply can’t afford to pay your workers at least a living wage, make sure he or she isn’t required to work with your company on a full-time basis. Don’t try to turn your part-time pay into someone else’s full-time livelihood. Instead, agree on a parttime work schedule and encourage your team member to get a second job, if necessary, at least until your com- pany can afford to pay him a livable wage.

There are several resources online that can show you what an estimated livable wage amounts to on a state-by-state basis in the United States. Just Google it.

Should some workers be paid more than others?

Considering all the laborers were paid the same in the Parable of the Vineyard in Matthew 20, should all our workers be paid the same, regardless of the type and quality of work they do? The Parable of the Vineyard shows us there is a minimum standard of right compensation employers ought to pay, which amounts to a living wage that ensures our workers can afford their daily necessities. But the Bible has more to teach us about the issue of assigning monetary value for different types and qualities of work at different times and places.

As Christ-centered companies, it’s likely that we’re paying different wages to different people based on the type and quality of work they perform. But is it Christlike to pay one person less money than another for one hour of work at the same workplace?

How should we assign monetary value to determine what a person’s wages should be?

In the eyes of God, is some work more valuable than others?

Work that requires significant risk is more valuable than work that doesn’t require much risk. The statement, “No risk, no reward,” is, of course, not in the Bible. However, the Bible does seem to teach that risk-taking is honored in God’s Kingdom economy. Those who wisely put their time, energy, and money at risk through investing typically earn greater rewards than those who don’t.

The “lazy” steward in Jesus’ Parable of the Talents was “thrown to the outer darkness” for taking zero risk with the resources entrusted to him by the master in the story (Matt. 25:30). His excuse was that he was “afraid.” Likewise, the average person is unwilling and often afraid to make significant investments of time, energy, and money to grow their knowledge, skills, opportunities, and professional networks. What if those investments don’t pay off as they would hope? Seth Godin encourages people to approach such investments with this reality in mind: “This might not work.” Work performed that might not produce the desired payoff is the kind that typically produces the greatest rewards in God’s economy.

Unlike the fearful and consequently lazy steward, the two stewards who invested what they had been entrusted (i.e., risktaking) earned back twice what they had risked in the marketplace. As such, it seems both reasonable and biblical to pay people more somewhat in proportion to the investments they have made in education and developing their knowledge, skills, opportunities, and professional networks.

Also consider the risks taken and investments made by your

most loyal, longest-serving team members who have sacrificed all other professional opportunities to remain at your company exclusively and help you succeed over an extended period. These people deserve to be rewarded.

Work provided at the right time and place is more valuable than work that is not.

The Bible says, “There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under the heavens” (Ecc. 3:1). The sons of Issachar were commended in the Bible for (cont’d on page 6)

Volume 53, Issue 3

May June 2023

The Marketplace (ISSN 0199-7130) is published bi-monthly by Mennonite Economic Development Associates at 532 North Oliver Road, Newton, KS 67114. Periodicals postage paid at Newton, KS 67114. Lithographed in U.S.A. Copyright 2023 by MEDA.

Editor: Mike Strathdee

Design: Ray Dirks

Postmaster: Send address changes to The Marketplace 33 N Market St., Suite 400, Lancaster, PA 17603-3805

Change of address should be sent to Mennonite Economic Development Associates, 33 N Market St., Suite 400, Lancaster, PA 17603-3805.

To e-mail an address change, subscription request or anything else relating to delivery of the magazine, please contact subscription@meda.org

For story ideas, comments or other editorial matters, email mstrathdee@meda.org or call (800) 665-7026, ext. 705.

Subscriptions: $35/year; $55/two years. Published by Mennonite Economic Development Associates (MEDA). MEDA’s economic development work in the Global South creates business solutions to poverty. MEDA also facilitates the connection of faith and work through discussions, publications and conventions for participants.

For more information about MEDA call 1-800-665-7026. Web site www.meda.org

Want to see back issues or reread older articles? Visit https://www.meda.org/download-issues/

O'Brien/MEDA

O'Brien/MEDA

5 The Marketplace May June 2023

The Marketplace is printed on Rolland Enviro® Satin and is made with 100% post-consumer sustainable fiber content, FSC® Certified to help meet client sustainability requirements, Acid Free, Elemental Chlorine Free

Cover photo by Krista

their ability to “discern the times and knowing what Israel should do” (1 Chron. 12:32). In business, one aspect of wisdom is offering the right high-quality products, services, and skills in the right places and at the right times.

Unfortunately, many people in today’s economy have confined their skills to a specific type of job that is being displaced by new and emerging technologies. They have taken neither the steps nor made the investments necessary to find new applications for their skills. Nor have they pursued the acquisition of new skills.

It seems both reasonable and biblical to pay people who offer timely, high-quality work more than people who can only offer untimely work for which there is little-tono demand.

Specialized/scarce work is more valuable than non-specialized work.

From the beginning, God has called people to “fill the earth, and subdue it” (Gen. 1:28). Certainly, filling the earth geographically is one aspect of fulfilling this commandment. At the same time, the earth must be filled economically as each person taps into her unique God-given abilities, cultivating ever-increasing opportunities for contributions of labor.

The 12 tribes of Israel were each given separate land inheritances so they would spread out and “fill the earth” geographically, numerically, and economically. They each became known for making different types of economic contributions. For example, when Jacob blessed his sons at the end of his life, he declared that the Tribe of Zebulun would “reside at the seashore; And he shall be a harbor for ships,” referring to its calling to maritime

commerce (Gen. 49:13).

In the New Testament, consider how God distributes varieties of spiritual gifts to his people through the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 12:4-11).

Nobody in the Body of Christ has the exact same mix of spiritual gifts in the exact same measures for the exact same assignments. Each person has been entrusted with a unique role in fulfilling God’s mission on Earth.

We are called to be excellent in our work, but it’s difficult for a generalist to be truly excellent at any specific type of work. The clear division of labor in God’s economy enables us to focus on being excellent in the performance of specialized work. God didn’t create people to be jacks-of-all-trades, masters-of-none. He has created and called each person to unique, specialized work although we will have multiple God-given assignments throughout our lives.

But it feels risky to specialize in a particular skill set, which is why many people don’t do it.

Don’t settle for paying just “the going rate.”

Let’s assume you’ve hired the right people who perform truly valuable work. Typically, we feel justified in paying “the going rate” for a particular line of work, but let’s consider that God may be calling Christ-centered companies to exceed these cultural norms and rise to higher standards of gratitude and generosity regarding work performed by our team members.

As Jeff Van Duzer points out, the “invisible hand” of market forces that Adam Smith wrote about in The Wealth of Nations does not necessarily equate to the sovereign hand of God. Simply

because a particular labor market will bear lower wages doesn’t mean higher wages shouldn’t be paid by a Christ-centered company. Consider the compensation philosophy examples set by these Christ-centered companies:

• Hobby Lobby pays all fulltime workers at least twice the federal minimum wage.

• At Bridgeway Capital Management, no one can earn more than seven times the lowest paid person at the firm.

• In-N-Out pays their managers $122,011 per year on average, which is about three times the industry standard.

Christians are called to be the most grateful and generous people on the planet. If that’s true of us, Christ-Centered Company leaders would naturally want to express that greater sense of gratitude and generosity toward our team members through higher-thanaverage wages — and make sure they are paid in a timely manner.

Reflection, Discussion, and Application

What is a livable wage for your team members?

What is your company’s compensation philosophy? Do you pay your team members below, at, or above the “going rate” for their work?

How do you ensure your employees, contractors, and suppliers are paid promptly for their work? .

Darren Shearer is the founder and director of the Theology of Business Institute, which helps marketplace Christians explore and apply God’s will for business. He is the host of the Theology of Business Podcast and Houston Christian University’s Christianity in Business Podcast. Darren has authored five books, including Marketing Like Jesus: 25 Strategies to Change the World and The Marketplace Christian: A Practical Guide to Using Your Spiritual Gifts in Business. He is also the founder and CEO of High Bridge Books & Media, a multimedia agency specializing in publishing and promoting the world-changing ideas of Christ-centered influencers.

6 The Marketplace May June 2023

Darren Shearer

Investing for job creation

MEDA Risk Capital Fund aims to support the organization’s programs and strategic goals

Some MEDA supporters are surprised to learn that the organization holds a fund that makes investments.

Why does the MEDA Risk Capital Fund (MRCF) exist, they ask? And how does it relate to the organization’s strategic goal to create decent work for 500,000 people?

Investment is part of MEDA’s DNA and has been since its inception almost 70 years ago, Jessica Villanueva says.

MEDA got its start as an investment club, with people risking money to test solutions to poverty.

A group of ten Mennonite businessmen each invested $5,000 US. This allowed Paraguayan farmers to improve their dairy genetics through a successful breeding partnership that became known as the Sarona Dairy. The efforts helped to multiply milk production from a quart a day to between four and five gallons a day.

The original investment was repaid and has been reused again and again in succeeding decades.

At its inception in the 1950s, MEDA was only an investment fund, Gerhard Pries said. Pries was a long-time MEDA chief financial officer who went on to found Sarona Asset Management, a private equity firm that was spun out of MEDA in 2010.

“All of MEDA was an investment fund. There was no donation-funded program,” he said. “So, the original investment

7 The Marketplace May June 2023

Jessica Villanueva is MEDA’s senior director of technical areas of practice.

fund was called Mennonite Economic Development Associates.”

MEDA’s investment focus has evolved dramatically over its history. It started with specific investments in companies such as the Sarona Dairy, the Sinfin Tannery, and the Fortuna Shoe Factory.

As the organization matured and became more program-focused, the emphasis on investments waned.

In the late 1990s and early years of this century, MEDA began working with more systemic investments through platforms such as MicroVest and Sarona. Over time, it shifted its focus to programlinked investments which reinforce

the need for both financial and non-financial support, including technical training.

Investments made by MEDA over its 70-year history can be categorized in four different ways.

1)Debt investments into Paraguay’s Sarona Dairy or

Mountain Lion Agriculture

— a rice milling firm in Sierra Leone — have been thematic. These were designed to support the growth of individual companies.

2)Platform builds occurred in the past several decades, trying to promote the development of a new ecosystem by creating a new entity. MEDA’s equity investments into the MicroVest microfinance firm in the US, Sarona Asset Management in Canada, and US non-profit ImpactAssets are examples of this.

3)Project-linked investments emerged beginning in 2010. These took two forms. A project in Tajikistan involved equity

Blazing a trail towards equity through gender lens investing

MEDA’s strategic decision to focus on empowering women in the agri-food sector in sub-Saharan Africa is a pioneering model that should spread through the international development sector.

So says the chief investment officer of a private equity firm that focuses on women’s economic inclusion.

“We need thousands more smart actors like MEDA working in this space,” Christina Juhasz said.

Juhasz is the chief investment officer & managing partner emerging markets funds at Women’s World Banking Asset Management (WAM).

Women’s World Banking is a global non-profit that has championed women’s financial inclusion and economic empowerment for over 40 years. Nearly one billion women around the world remain underserved by the financial sector, it estimates.

WWB’s WAM subsidiary makes direct equity investments in inclusive financial institutions with an explicit focus on women through Women’s World Banking Capital Partners Funds I and II. Those funds have more than $150 million

MEDA’s early investments in Women’s World Banking funds viewed as pivotal

under management. MEDA invested in both funds.

“The majority of economically employed women in the world are actually involved in agricultural activities, and yet they are so much more vulnerable to things like climate shocks or any kind of risks because they are under-resourced,” Juhasz said. “It’s incredibly important for us to be reaching those women.”

Women who work small plots rarely receive loans and have no risk cushions, so they cannot invest in the types of seeds and fertilizers that would allow them to have better-quality harvests.

“Trying to reach those women is an absolute priority.”

MEDA’s relationship with WWB, and Juhasz herself, predates the establishment

of the funds that she oversees.

WWB collaborated in advisory work with MEDA, “particularly on financial risk management,” she said.

Shortly after she joined Women’s World Banking (WWB), Juhasz had the opportunity to work with MEDA staffer Ruth Dueck Mbeba. She found Dueck Mbeba’s work and MEDA’s research and approach to development to be “incredibly rigorous and informative.”

The relationship between the two organizations deepened when MEDA was among the first investors in the first fund Juhasz launched in 2012.

“It’s hard to overstate the value of MEDA (investing with us),” she said.

MEDA’s early support for the gender lens investing strategy was a gamechanger since it also encouraged others to invest with WAM, she said.

MEDA invested $1 million from its risk capital fund into the first WAM fund, which was a $50 million fund. It was also the only faith-based investor in that fund.

MEDA is one of the early faith-based investors that is taking steps to ensure their investment dollars are values

8 The Marketplace May June 2023

8 The Marketplace May June 2023

investments and technical supports. A project in Senegal received debt investment plus technical assistance. These investments aimed to achieve systemic impacts in countries where economic growth and development are held back by a lack of capital and technical knowledge.

Research has shown that MRCF’s project-linked investments have resulted in vastly more job opportunities for women than investments that were not linked to projects.

4) By 2012, MEDA was using a blended finance investment strategy in many projects. Blended finance combines official development assistance with other private or public resources to leverage additional funds from other investors.

MEDA aims to serve three interconnected roles in impact investing. It wants to be a catalyzer, placing resources into strategic sectors, geographies, and impact themes.

It also wants to be a convener, influencing other investors to mobilize their capital through co-

investment opportunities. Finally, it works at being a thought leader, encouraging other impact investors to apply MEDA’s learnings toward creating their own investment solutions.

The MRCF is a tool to achieve MEDA’s strategic goals. New investments are made in service

aligned, she said. “It is pioneering in values-based investing.”

Juhasz’s first fund had created almost 15,000 jobs by the end of 2021, just over 4,000 of which were for women.

MEDA also invested in WAM’s second, $103 million fund. That fund has invested in 11 portfolio companies since 2020.

Jessica Villanueva is MEDA’s senior director of technical areas of practice. She represents the organization on the advisory board for the second WAM fund.

The WAM approach aligned with MEDA's efforts to benefit women through impact investing, she said. “They have a strong gender strategy that they use to identify gender-inclusive financial intermediaries, and they provide technical assistance … to increase the number of women they are engaging.”

Both investments have provided MEDA with strong dividends and financial returns that can be re-invested in other projects.

Villanueva has been pleased by WWB’s work in tracking and measuring the impact of its investments. .

9 The Marketplace May June 2023 The Marketplace

Christina Juhasz is chief investment officer & managing partner, emerging markets, at Women’s World Banking Asset Management.

of MEDA’s efforts to create decent work for 500,000 women, youth, and men in agri-food market systems.

They will work to sustainably improve these systems by using two specific lenses: gender equality and social inclusion; and environmental sustainability and climate action.

Investments will be prioritized within the context of MEDA’s development programs. They will seek to leverage knowledge developed through these programs to identify financial needs and to screen, assess, and structure investments.

The MRCF investment committee includes a group of seasoned businesspeople. MEDA

board representatives include Rob Schlegel, Jeremy Showalter, Greg Gaeddert, Chad Horning, Crystal Weaver, and Jenny Shantz.

External advisers are Tohunbok Ishmael, who provides an African perspective, Craig Pho, who provides an Asian perspective, and generalist Tara Proper.

MEDA staff representatives include CEO Dorothy Nyambi, CIO Wendy Clayson, senior vicepresident of strategy & impact Lindsay Wallace, and director of investment finance Erika Wulff.

Sarona Asset Management provides advisory and monitoring services to MEDA for the MRCF.

Improving entrepreneurs’ access to finance in the Global South is crucial, Villanueva said.

Investments at MEDA: A timeline

• 1950s: Ten Mennonite businessmen each invested $5,000 US, so Paraguayan farmers could improve their dairy genetics through a successful partnership that became known as the Sarona Dairy.

•1990s: Some MEDA members offer to lend money to MEDA to be loaned to microentrepreneurs in MEDA’s Small Business Development Program, as the microcredit program was then known.

• 1999: MEDA decides to formalize its investment strategy by establishing the Sarona Global Investment Fund. As a legally separate fund, it gives private investors a chance to support investment-based development. The Sarona fund is managed by MEDA Investments, Inc., a wholly owned subsidiary of MEDA. Its mandate includes providing loans to local microcredit lending institutions, as well as investing in agricultural cooperatives, fair trade organizations, and new enterprises, which need startup capital in order to provide a local market for small agricultural producers’ products.

• 2004: After launching MicroVest (along with two other partners), MEDA agreed to channel all microfinance investments to MicroVest and focus MEDA’s investments on other higher-risk impactful sectors.

• MEDA’s investment fund is “transformed from a general investment fund to an earlystage risk capital fund to help launch young MEDA-related initiatives…” That fund becomes known as the Sarona Risk Capital Fund.

• 2010: MEDA transfers its investment fund development to a new MEDA-owned, forprofit subsidiary, Sarona Asset Management Inc., headed by Gerhard Pries, a former MEDA chief financial officer and director of investment fund development.

• 2011: MEDA sells 90 percent of Sarona Asset Management to private management and investors. The move reduces risk for MEDA and increases the private equity firm’s appeal to institutional investors. MEDA retains a 10 percent stake in the firm.

• 2018: The Sarona Risk Capital fund name is changed to the MEDA Risk Capital Fund to avoid confusion with Sarona Asset Management.

• 2022: $200 million MasterCard Foundation Africa Growth Fund announced. MEDA heads up a consortium of partners for this initiative, which aims to create 15,000 decent jobs in the agri-food sector in sub-Saharan Africa. .

MEDA wants to use its capital “to be catalytic, to ensure that we are stimulating the response in the financial ecosystem.”

MRCF investments have been longer-term commitments with limited liquidity, so a new approach is required.

That means MEDA is “stopping investing directly into companies. Now we want to do that through financial intermediaries because we think that there’s a way to leverage our capital.”

The new approach, seen in the MasterCard Foundation Africa Growth Fund consortium that MEDA spearheads, is consistent with MEDA’s maturation.

MEDA grew from working with individuals and groups of farmers to a lead firm model in order to have greater impact. Similarly, its new approach is designed to have locally led, systemic impact.

As the $150 million capital that will be invested through the MasterCard Foundation Africa Growth Fund is returned over the next 10 to 15 years, that money will be repaid to MEDA and form part of the MRCF. That will dramatically increase the amount of money available to invest from the $22.3 million of investments MRCF held as of Sept 30, 2022.

Impact measurement will be crucial to the success of MEDA’s approach, Villanueva said. “We need to be more sophisticated on our measurement. And I think that this is still a work in progress.”

Discussions around how best to measure impact to avoid greenwashing or pinkwashing are happening in the industry now, she said.

Greenwashing is pretending to make meaningful changes around the environment and climate change. Pinkwashing is pretending to make meaningful changes with regard to gender. .

10 The Marketplace May June 2023

10 The Marketplace May June 2023

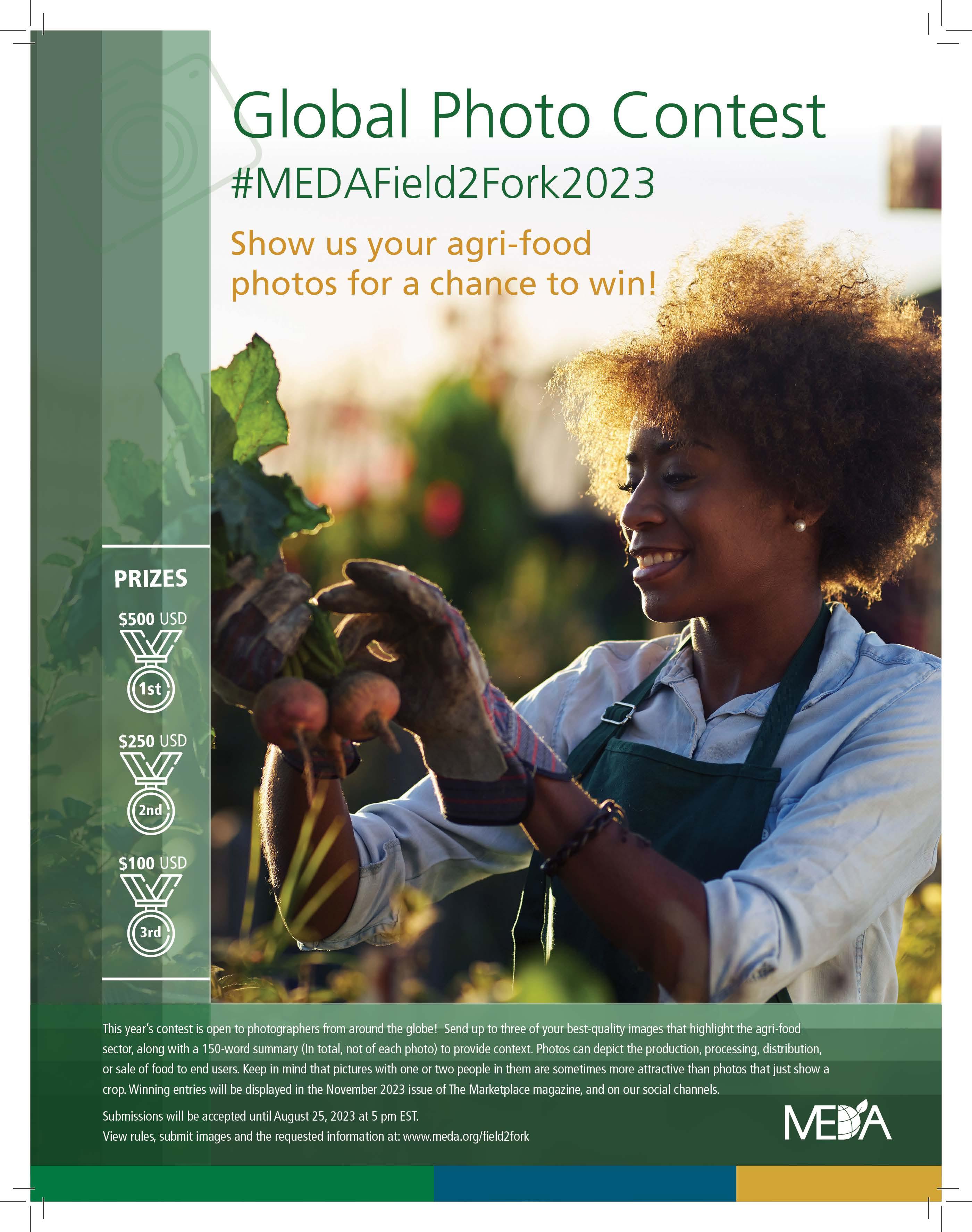

Growing in Ghana MEDA board visits groundnut processor Dunyiya Enterprise

Dunyiya is located at Banvim, a community in the Northern region of Ghana. The business is owned by Sulemana Abdul Majeed, who is a farmer and an entrepreneur.

Dunyiya opened its first groundnut shelling center in 2012. The business serves small-scale women farmers. It helps to reduce the drudgery of women shelling groundnuts (peanuts) with their own hands.

The shelling center has a capacity of shelling 16 metric tonnes of groundnuts per day for farmers, especially women. The center offers

job opportunities to women directly and aggregators who shell their groundnuts using the facility. During peak season, the facility will employ up to 30 women, many of them widows.

MEDA’s GROW2 (Greater Opportunities for Rural Women) project is negotiating with Dunyiya to provide business development services and a matching grant award of $100,000 Canadian. Dunyiya would use that money to expand its business by setting up a shelling center close to GROW2 project clients to create jobs for women entrepreneurs. — Krista O'Brien

Women harvest groundnuts and bring them to Dunyiya to remove the shells, expediting the process from ground to market. Many of the women who work to provide for their families are widows. Shelled groundnuts fetch a higher price at the market, helping to raise incomes for farmers and saving them hours of labor. To see the business in action, watch a video at https://vimeo.com/811061303

The Marketplace May June 2023

12

photo by Kelvin Dela Armstrong/ Kelldellstudio

13 The Marketplace May June 2023

Photos on this page by Kelvin Dela Armstrong/Kelldellstudios

Fanning the Embers

Indiana woman renews the family tradition of building recreational vehicles

By Marshall King

BRISTOL, Indiana — Ashley

Bontrager Lehman has a passion for her family business.

When she and several other industry veterans were creating and naming a new recreational vehicle for a new recreational vehicle (RV) manufacturer, they were going to call it Element RV, with her being the fire.

They ended up establishing Ember RV. And yes, she’s providing the spark to make this company successful.

Bontrager Lehman wasn’t born yet in 1985 when her grandfather, Lloyd Bontrager, died in a plane crash with his son Wendall and two others. Lloyd was an innovator in making campers, including a lift system for pop-up RVs. That product was the basis for a company called Jayco, which Lloyd and his wife, Bertha, co-founded in their barn near Middlebury, Indiana.

Jayco started with 15 employees who made and sold 132 campers in the first year. In the 1970s and 1980s, the family business expanded to produce other kinds of RVs, including travel trailers, fifthwheel units, and small motorhomes.

The plane crash rocked the family and company, but they forged ahead. Bertha took over the company with sons Wilbur and Derald, Ashley’s father, and worked with others to ensure success.

Ashley had grown up in Middlebury and left for Butler University. Like many, she had said she wouldn’t come back to northern Indiana. After graduating

with a degree in public relations and advertising, she moved to Washington, D.C.

But the pull of the family business was strong, and she came back in 2011. She worked in advertising and marketing and started to work her way up through the ranks.

“My family always did a great job incorporating what we called the third generation into that business,” she said. Growing up, she’d gone to family board meetings, gone on tours, and learned how the company worked. As a young woman in her 20s, she now hoped she’d someday run Jayco Inc., which had become the largest privately held RV company and a leader in the industry. It provided jobs for several thousand employees. In 2016, the millionth unit rolled off the line.

That year was also when the company closed a sale with Thor Industries, one of two giant companies that now own most of the brands in the industry. The

Bontrager family, which has a long history of philanthropy, continues that tradition of giving after the $576 million sale.

Ashley and others in her family continued to work at Jayco. She had become director of marketing prior to the sale and stayed in that role for several years before leaving the company. She both understood the family’s decision and was disappointed that she wouldn’t someday be the president/CEO of Jayco.

The urge to carry on the family legacy didn’t go away. The embers kept burning, so to speak.

“I still had the desire to run an RV company and stay in the industry,” she said.

In 2021, she had the opportunity to forge into new territory. A group of cofounders came together to establish Ember RV.

Industry veterans Chris Barth, Steve Delagrange, and Ernie Miller joined her to establish a new RV company.

14 The Marketplace May June 2023

Photos by Marshall King

Ashley Bontrager Lehman wants EMBER RV employees to enjoy coming to work.

They believed there is room in the industry for an independent RV company and started one to produce towable RVs.

The first priority was building a team of good people to create something a family can take camping. Four others from the industry joined the company’s management team.

“Our ultimate goal is to create an inviting culture that values every team member, that brings people in to do the job, but that they leave fulfilled going home to their family.”

She preaches that employees need to enjoy coming to work, feel valued, and know they’ve made a difference. She uses the phrase, “Be a good Ember citizen.”

Her Mennonite grandparents lived by the Golden Rule, and she also puts it into practice. Ashley, who attends a non-denominational church with roots in Anabaptism, said that you don’t have to be a missionary to have a mission and small actions can have a large impact on others. She leads a team with passion and fire but also care and regard. “It’s treating people well,” she said. “I never want to look at people as a tool to get the job done. Every individual has value, no matter what their role is here.” Those aren’t values always found on the assembly line of an RV factory. She purchased a production building and an office building a mile from each other near the Indiana Toll Road. They lined up

suppliers, created assembly lines, and crafted marketing to sell the new RVs.

The first product is the Overland, a towable RV you can pull with a Jeep and head into the wilderness rather than just a campground. When it debuted during the COVID-19 pandemic, campgrounds were full. This camper, with a manufacturer’s suggested retail price in the $40,000 to $60,000 range, has independent suspension, a robust solar system, and larger water tanks. She compares it to a hiking boot.

The second product, called Touring Edition, is more like a pair of running shoes, she says. It has high-quality materials but is more suited to the campground than going off-road. That unit is being compared to the iconic Airstream camper, which she said shocked and pleased her.

Bontrager Lehman loves camping and what it can do for individuals and families. She likes getting away into nature and putting away screens. She’s a wife and mother who goes to work and leads a company.

“It’s a lot of hard work,” she said. She knew that starting a company would be hard, but it brought surprises, including the challenge of getting licensing in every state for their products.

The RV industry has a good ‘ol boy feel. At a recent meeting with a local congressman, she was one of the youngest and only females in the room. She said people look down on her all the time, but she focuses on the work and inspiring others. After all, when she started Ember, she was 35 years old — the same age as her grandfather was when he started Jayco. .

Marshall V. King is a writer and journalist based in Goshen, Indiana. He is the author of “Disarmed: The Radical Life & Legacy of Michael ‘MJ’ Sharp.” You can read more of his writing at hungrymarshall.substack.com.

15 The Marketplace May June 2023

Ashley Bontrager Lehman started Ember RV in 2021, five years after Jayco, the thirdgeneration family business where she worked as director of marketing, was sold.

Sometimes, it is time to sell the business

Excel Industries decision made over $100 million available for charity, provided exit for shareholders, former executive says

Sometimes, the sale of a familycontrolled business is better than trying to pass it on to a third generation of family management.

Especially when the interests of 40 shareholders from multiple generations of several families have to be considered, Bob Mullet says.

Mullet knows of what he speaks. He had a front-row seat to the events leading to the sale of Excel Industries to Stanley Black & Decker for $375 million US.

Not only that, he thinks that his father, who headed up the firm for over two decades, would approve.

“If Roy were around, I think he would be pleased.”

Excel Industries was started in 1960 in Hesston, Kansas.

Two years later, Roy Mullet joined Excel at the encouragement of Cal Redekop. Redekop, an academic and entrepreneur who later launched The Marketplace magazine, was an Excel shareholder. He also worked at the company during a sabbatical year.

Roy Mullet became president soon after joining Excel. He served in that capacity until 1985 when he retired at age 65.

The company grew with John Regier’s creation of The Hustler, the world’s first zero-turn mower, which went into production in 1964. The design helped people mow irregular yards, and zero-turn mowers are now commonplace

within the mowing industry.

Roy Mullet’s son, Bob, worked for Excel in the summers, learning double-entry bookkeeping in the office. He was not involved in the firm directly until the mid-1980s, when he took a board position.

After leaving Kansas, Bob did part-time sales work for Excel “in the territory around Paoli,” a small town in southern Indiana.

In 1993, he moved to Kan-

sas and took on the role of chief financial officer for Excel. Eventually, he also became responsible for human resources and manufacturing. “I was kind of the, if not by title, at least the de facto COO (chief operating officer).”

Bob Mullet retired from the firm in 2018. His brother Paul joined Excel after graduating from Bethel College in 1972. Paul Mullet was Excel’s president from 1991

seated on one of Excel’s Hustler turf machines, who served as Excel’s president from the early 1960s until 1985. Others in the photo (l-r) are Paul Mullet (Excel’s president from 1991-2018), Paul’s sons Adam and Chad, Bob Mullet, and Bob’s son Luke.

16 The Marketplace May June 2023

Three generations of the Mullet family worked at Excel Industries. This 2005 photo shows Roy Mullet,

until he retired in early 2018. Then Excel recruited an external CEO.

Joe Wright, Excel’s final top executive, was no stranger to the industry. He worked for Briggs and Stratton, the world’s largest manufacturer of engines for outdoor power equipment, for most of his career.

Wright oversaw operations at Excel and prepared it for an auction that led to its sale to Stanley Black & Decker in 2021.

At the time of the sale, Excel had 630 employees. It sold its products through more than 2,500 US retailers and 25 distributors worldwide.

In the last decade before Excel was sold, the firm had about 40 shareholders. Most of those people were members or descendants of the five or six families that had been involved with Excel since the 1960s.

“I felt that Excel was, we were increasingly a company that was owned by disinterested outsiders … people that had never worked at the company,” Bob Mullet recalled.

Treating those people fairly was a challenge, he said. On the one hand, buying them out would have created an unaffordable cash drain on the firm.

Since Excel did not do that, ownership just became more and more diverse.

The group that was in charge of the company had “if not an absolute majority, at least a working majority,” Mullet recalls.

Despite paying dividends, having that many shareholders left management feeling a sense of responsibility, he said.

“I think a lot of those people were in what a financial advisor would say was a pretty bad position, which is they were undiversified. They had an illiquid investment, over which they technically had no control.”

Mullet recalls another

company, a family business in which one or two of the siblings worked in the firm. Three or four others did not. The company “got into the habit of paying a lot of dividends, so the non-inside sibling pretty much depended on that. That’s what they lived on.”

When an economic downturn came, and things got tough, the company continued to pay the dividends despite losing money. Eventually, that firm’s bank came in and told the firm they could no longer pay the dividends.

“You can imagine what that did to the family dynamics.”

In Excel’s case, the majority of shareholders were descendants of Roy Mullet, his brother, Henry, and his brother, Tim.

For the first 50 years of Excel’s existence, Mullet family members made up about half the board. Other minority shareholders were represented as well.

Prior to 2010, Excel “made a very conscious decision that we wanted to get outside board members,” Bob Mullet recalls.

Excel recruited people with diverse skills to serve. That left only Bob and Paul Mullet as family members serving on the sevenperson board.

Charitable giving was a strong part of Excel’s culture, Bob Mullet said. “My Dad was a firm believer in the 10 percent tithe (money given to charity). So, for a long time, Excel just consistently gave 10 percent of their profits. As the company got a lot larger, you know, all of a sudden, that became a really big number.”

Eventually, some people began questioning whether giving away that money was fair to shareholders.

“But in anticipation of the sale, a lot of the (Excel) stock got donated, most of it to (the philanthropic arm of) Everence (Financial). At the time of the sale, Everence actually owned 30 percent of the company.”

That means $113 million will eventually flow to charities through donor-advised funds or foundations held at Everence.

“One of the things about the sale that was to me (Bob) a clearly good thing was all of a sudden everyone’s got liquidity, and so all shareholders who had charity things in mind, now they can fund them.”

“That’s been real positive, and I think that it's also very consistent with the long-standing philosophy of Excel."

Bob Mullet had a son working at Excel, and two of his brother Paul’s sons were also working there.

“I certainly felt some sympathy, I think, to the pressure that those guys would have faced if we had said: There’s a family business you guys have to take over. You run it. I mean, that’s a big responsibility.”

“So I think that’s one of the things that family businesses have to deal with, right? If we wanna keep this going and going as a family business, number one, are there family members coming along? Do they have an interest in doing it and do they have the talent and the ability to do it?” .

17 The Marketplace May June 2023

“One of the things about the sale that was to me a clearly good thing was all of a sudden everyone’s got liquidity, and so all shareholders who had charity things in mind, now they can fund them.”

— Bob Mullet

Successful business succession can take many forms

Kansas consultant helps farm families find the best path

Lance Woodbury is annoyed when business professionals frame a succession process that doesn’t involve the next generation taking over as failure.

Consultants for accounting firms and family businesses too often use language that he views as a “terrible, terrible framing.”

Woodbury has seen situations where a family business is passed to the next generation, “but everybody hates everybody, and there’s no relationships… and the business is full of dysfunctions.”

“So you’ve kept the business going, but there is no family relationship anymore… the whole reason you had a family business is no longer…”

Woodbury, a Kansas native and son of a Presbyterian minister, has done mediation and succession consulting with family businesses across the US for almost three decades. He has authored two books on family businesses and writes a weekly e-mail newsletter entitled Faith & Family Business.

About a dozen years ago, Woodbury began focusing solely on people who are farming, ranching, or raising livestock in some other capacity.

He spends about 40 percent of his time facilitating peer group meetings with farmers and ranchers in their 30s and 40s.

There are a few recurring reasons why farms end up being split up or sold instead of being passed to the next generation, he

“The next book I want to write is a book on how to split up a family business or when splitting up is good for everyone.”

— Lance Woodbury said. Woodbury often encounters family members who have different goals for the business or “don’t have interest in participating in the business and are not sure how it will be managed.”

Given that the average age of a US farmer is 58, “often I get calls to collaboratively split up the business.”

Such callers are less interested in discussing succession than in figuring out how to dissolve family businesses where people in their 50s, 60s, or 70s no longer want to hold an illiquid asset with multiple other shareholders, he said.

“The next book I want to write is a book on how to split up a family business or when splitting up is good for everyone,” he said.

The book’s goal will be to help take the fear out or give people

permission to explore selling or splitting up a family firm, he said.

Woodbury helped one family split up an 80,000-acre operation. That process took four years.

That isn’t a long engagement in his line of work. The succession process – he dislikes the word plan in this context – can stretch on for many years. He has some clients that he has worked with, on and off, for decades.

Family businesses go wrong when “the senior generation sticks its head in the sand or just says, hey, you guys need to get along.”

Trying to use generational authority to resolve a dispute instead of embracing a conflict management or conflict resolution process doesn’t fix things, he said.

“Conflict is just normal, conflict isn’t bad, conflict is a part of our lives. And what matters is how you handle it.”

But family business sales aren’t usually the result of conflict in the farm families that Woodbury works with.

Worse than conflict is uncertainty, he said. “What really causes trouble is people not knowing.”

“One of my favorite lines I use is: in the absence of a good story, people make one up.”

So if parents don’t tell a story about what will happen with the future of a farm business, “the kids are making it up, and oftentimes they’re getting into conflict because of those assumptions.” .

18 The Marketplace May June 2023

Employee burnout is contributing to North American labor shortages

Denver executive suggests ways companies can attract, keep engaged workers

Employee burnout is a major problem that is worsening labor shortages across North America, Helen Hayes says.

In a typical year, the average American works 100 hours more than a Briton, 300 hours more than a French employee, and 400 more hours than a German, Hayes said.

“No wonder the average American is burned out,” she said in a speech to the Denver Institute for Faith & Work’s annual Business for the Common Good conference.

Hayes, a former portfolio manager for Colorado investment firm Janus Capital, is the CEO of Activate Work. She started the non-profit Activate in 2016 to help diverse people move from economic struggle to economic flourishing through skills training, life coaching, and placement.

Activate’s training prepares people for success in the knowledge-based economy. Their average learner goes from earning $20,000 to $46,000 a year.

The program expects to train 1,000 people over the next five years. It focuses not on poverty alleviation but on restoring people to dignity, to their fullest potential, she said.

Traditional methods of hiring leave valuable talent out, she said. Activate takes a “more regenerative approach to the workforce that brings in and nurtures talent.”

Hayes is also the author and executive sponsor of the Colorado inclusive economy movement, a

CEO-led effort to use businesses to build racial equality and economic opportunity through job creation.

A recent Gallup poll found that 76 percent of workers experience burnout at least some of the time, she said. Half feel burnt out now, and one-quarter of employees reported being burned out at work very often, or always.

Worker shortages force staff in both the non-profit and for-profit sectors to face additional burdens of additional responsibilities. Hayes’ organization has a 14-person org chart, but currently, only ten staff.

Burnout is diagnosed by five symptoms, she said. These

include unfair treatment at work, unmanageable workload, unclear communication from managers, a lack of manager support, and unreasonable time pressures.

For Hayes, the burnout problem can be summed up in two words: “Poor management.”

“But there is hope, because good management can cure burnout.”

She cited the New Testament parables of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10) and the Sheep and the Goats (Matthew 25) to make the case that the gospel is eminently pragmatic. We love our neighbor, and our God, by meeting physical needs, she said.

19 The Marketplace May June 2023

Helen Young Hayes

Photo by Josh Barrett/Courtesy of Denver Institute for Faith & Work.

Helen Hayes leads a Denver non-profit that helps people move from economic struggle to economic flourishing.

“I believe we can proclaim the gospel most loudly and clearly in the marketplace,” she said.

Low-wage retail, hospitality, and food & beverage jobs are experiencing the highest quit rates, she said. “People are re-evaluating the value of low-value work.”

“Given the workforce exits, the balance of power has shifted to workers. They can afford to be choosy, and they are.”

Dan Kaskubar was part of a panel discussion following Hayes’ speech. SHRM, the Society for Human Resource Management, suggests 70 percent of employees’ engagement is due to their immediate supervisor, he said.

“People leave bad bosses. They don’t leave good jobs,” Kaskubar

Seismic shifts in the US workforce

• There are 2.8 million fewer workers in the US compared to February 2020

• 11 million open jobs

• 5.7 million unemployed workers, meaning there would still be five million open jobs if all available workers found positions

• Colorado has: 231,000 job openings

• 106,000 unemployed workers

• That means there are 56 workers for every 100 job openings

• Employee burnout is at record levels, and the World Health Organization has classified burnout as a medical condition, a syndrome that results from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.

• Workplace stress is costing the US economy over $500 billion annually and is the cause of 120,000 deaths a year.

• 73% of Americans say money is their dominant cause of stress.

said. “Good bosses can make any bad job tolerable, and bad bosses make any great job bad.”

Not only have workers left the workforce, but 60 percent of those who remain are disengaged, Hayes said.

Nineteen percent are “downright miserable, and over half of your workers are quiet quitters.”

Quiet quitting is reflected in workers who choose to reject the “hustle culture, and the always on, always available culture that many of us grew up in,” she said.

There are many causes for worker disengagement. Most of them stem from a lack of clarity about expectations from their managers and not feeling connected to a company’s mission and purpose.

Little to no recognition for hard work and receiving little career development also play a role.

Hayes proposes re-imagined hiring as a solution to these problems. Hiring needs to cast not only a wider net but a more equitable and inclusive net, she said.

Removing bias, skills-based hiring, writing more inviting job descriptions, and second-chance hiring are all part of the solution she proposes.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts are an important part of removing bias, she said. They can all be boiled down to the simple concept of treating people the way you want to be treated. “D, E & I is not a four-letter word and should not be in the Kingdom.”

Recognizing and removing bias at the source is the first and most important part of DEI efforts, she said.

In hiring, resumes submitted by people with African American names get 50 percent less callback than identical documents submitted by people with white-sounding names, she said.

People of color are hit first, hit hardest, and recover last, if at all, from economic shocks, she said.

Gender bias is revealed by the fact that men are viewed more favorably than women for identical qualities, such as being married and being a parent.

“When we can eliminate bias, we will enlarge our talent pool, and invite in those who are most marginalized.”

Skills-based hiring expands the applicant pool by doing away with irrelevant qualifications as a proxy for competence. College degrees, for example, are not a predictor of success on the job, she said.

“This has large implications for diversity and inclusion, and an expansive, re-imagined workforce hiring practice.”

Activate tries in its job postings to stress that “women and people of color are strongly encouraged to apply.”

Most women disqualify themselves from a job posting that an equally qualified male will apply to with eagerness, she said. “That’s one of the differences of our genders.”

Giving a chance to prospective employees who have been involved with the justice system is “one of

20 The Marketplace May June 2023

For Hayes, the burnout problem can be summed up in two words: “Poor management.”

May June 2023

Dan Kaskubar

the most redemptive acts of love at its best,” she said.

Hayes also suggested that employers must turn their attention not just to new ways of hiring but also to developing cultures of flourishing.

• Generous wages and benefits, including equal pay for equal work, top her list of suggestions.

• Job flexibility, hybrid, and remote work opportunities are the second, sometimes even the top thing that workers want, she noted.

• Addressing the mental health crisis that has resulted in widespread burnout is also critical. “We’re tired, and our workers are tired.”

• Companies can be reenergized by building inclusive, appreciative cultures, allowing people to be their authentic selves at work, she said.

• Career pathing is important. This involves asking employees where they want to be, how they want to grow, and where they see themselves contributing best.

• Talent upskilling, something most employees want, results in increased worker retention and loyalty.

• Mentorship and sponsorship are important ways for employees to navigate a company’s culture and also to be promoted or advanced within their organization.

Building a culture of flourishing results in tangible benefits, she said. “It’s good business, but it’s also great gospel.”

As the Gallup organization noted, people who feel inspired, motivated, and supported in their work do more work, she said. Such work is significantly less stressful for their overall health and well-being.

“We will be judged and known by our love, by the way we bring our employees and our cities to their fullest, God-given potential. We have a holy and high calling in the workplace. May we shine

together like a city on a hill through the shalom of our workplaces.”

Meeting those ideals can be challenging, other speakers hinted. While work is a good part of our identities, it is also part of a fallen world, said Joanna Meyer, the Denver Institute’s director of public engagement. “Let’s be honest, work stinks sometimes.”

And the tensions facing business leaders in the current environment make it doubly difficult for managers.

“It feels like we’re in a very frustrating time right now, where employers can’t afford to pay more, and people can’t afford to make less,” said Jervis DiCicco. He is the chief engagement officer with Prosperbridge, an organization that works with workers and employers to maximize benefits and wages.

For decades, wages haven’t kept pace with housing, education, and healthcare costs. Real wages declined in 2022 even after record wage increases, DiCicco said.

Fifty percent of jobs in Denver are front-line positions that pay less than $30 an hour, said Dan Kaskubar of SPUR LLC, a leadership coaching firm. “It is really hard, as a front-line worker, to support a family on less than $30 an hour,” he said.

Wages aside, employees tend to move around more often than in decades past.

“It is a challenge to attract good talent. It can often be a challenge to develop and retain good talent,” said Brian Gray, who works as vice president, formation, at the Denver Institute for Faith & Work.

Gray’s father, a civil engineer, worked for one company for 25 years. After leaving that company, he worked for three other firms over a three-year period.

“Today, business owners and business leaders are facing the challenge of — what does it look like to consider the flourishing of their employees? Not just the fiscal bottom line, not just the quality of product, and those are critical, but what does it look like to help their employees to thrive in the place where they work.”

Learning from the intersection of Christian teaching and workplace best practices can help, said Alli Horst of Denver recruiting firm Core Ventures.

“There are absolutely Christian values that overlap with good business practice,” she said. “Beauty and values shine through most in how tensions are handled.”

Thoughtful employers want workers with both humility and ambition, though many lean one way or the other, Horst said. “If you are just ambitious without humility, it’s destructive.” .

21 The Marketplace May June 2023

Jervis DiCicco

Brian Gray

The Knowledge Crisis and What to Do About It

Untrustworthy:

The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community

2022, 240pp, $24.99 US)

Reviewed by April Yamasaki

Have you noticed more fake news, more conspiracy talk, and an air of general mistrust? Do you notice polarization in politics, the church, and perhaps in your own family?

Do you see an emphasis on emotion and personal experience to the exclusion of facts? Do you see issues quickly escalate in politics, personal relationships, and every sphere of life?

In Untrustworthy, author and journalist Bonnie Kristian unpacks

all this and more as part of what she calls “the knowledge crisis” in American society: “We can’t agree about what we know or how we know it. The border between knowledge and opinion is disputed territory.”

In philosophy, the study of how we know what we know is “epistemology,” and Kristian does not shy away from using such technical terms. But she is careful to define them and uses plenty of real-life examples in her analysis.

She spends an entire chapter on defining the knowledge crisis, then turns in subsequent chapters to examine the role of media, public shaming, conspiracy thinking, skepticism, emotion, and experience.

Kristian spends her last

By Bonnie Kristian (Brazos Press,

three chapters outlining some practical alternatives: exercising humility and recognizing the limits of human knowledge; cultivating the virtues of study, intellectual honesty, wisdom, and love; developing good habits like slowing down our consumption of news, taking deliberate time away from our devices, and building genuine in-person relationships. This summary hardly does justice to the depth of analysis and the breadth of practical response in this book. I recommend you read Untrustworthy for yourself. .

April Yamasaki is an author, editor, and pastor. She lives in British Columbia.

Romaine wasn’t Built in a Day. The delightful history of food language By Judith Tschann, (Voracious/ Little, Brown, and Company 2023, 227 pages, $26 U.S.)

With Romaine Wasn’t Built in a Day, food historian Judith Tschann prepares a literary feast for people curious about the history of food names and word

nerds in general.

Her book is an informative and humorous stroll through words for what we consume in every meal of the day. It also demonstrates how much English owes to scores, perhaps hundreds of other languages and cultures around the globe.

As much as 80 percent of the vocabulary of English speakers is borrowed.

The beverages that many rely on for their morning pick up — coffee, tea, and the sugar used to sweeten either — have long and not always pleasant histories involving many cultures. Tschann notes: “the history of sugar (and coffee) is also the history of plantations, and thus, slavery.”

Such unsavory reminders of the evils of colonialism are only a garnish to her narrative, however.

More often, she sprinkles her prose with delicious, if unprovable, stories of the origins of things we eat regularly. Is it true, for instance, that the Earl of Sandwich, an 18thcentury noble with a gambling problem, came up with the idea of putting meat between two slices of bread so he could eat with one hand while holding cards in the other?

Did Romaine lettuce really get its name after a 14th-century Pope fled to Avignon during a schism in the Catholic church and planted a kitchen salad garden in that French community? The book is a worthy, if somewhat earthy, contribution to food literature. — MS

22 The Marketplace May June 2023 Books in brief

Work Pray Code: When Work Becomes Religion in Silicon Valley

By Carolyn Chen (Princeton University Press, 2022, 254 pages, $17.95 US)

Reviewed by John Longhurst

By Carolyn Chen (Princeton University Press, 2022, 254 pages, $17.95 US)

Reviewed by John Longhurst

Readers of The Marketplace believe faith and work go together. But what happens when people worship their work? That’s the question Carolyn Chen seeks to answer in her book Work Pray Code.

When Chen set out to study how working at tech companies in Silicon Valley affected the religion of employees there, she thought she’d find a thoroughly secular place. “Instead, I discovered it is one of the most religious places in America,” she said.

She found that people there spoke of their work in religious terms, such as how it “nurtures” their souls. Companies encourage

that mindset through things like yoga, meditation, and spiritual retreats. Some even have “chief spiritual officers.”

As religious affiliation and participation decline, what’s happening in Silicon Valley “helps us to see a broader trend . . . work is replacing religion,” Chen said. “People are not ‘selling their souls’ at work,” she said. “Rather, work is where they find their souls.”

What’s happening in Silicon Valley is “a cautionary tale for the rest of America,” she said, noting many people are finding meaning

in work. “What kind of society do we become when human fulfillment is centered in the workplace?”

Two comments about this thoughtprovoking book. First, Silicon Valley is a unique place; what happens there won’t necessarily occur across North America.

Second, for those who believe in the importance of combining work and faith, finding ways to balance those two things in our technological society will be an ongoing challenge. .

John Longhurst is a freelance writer and religion columnist for the Winnipeg Free Press.

23 The Marketplace May June 2023 Books in brief

O'Brien/MEDA

O'Brien/MEDA

By Carolyn Chen (Princeton University Press, 2022, 254 pages, $17.95 US)

Reviewed by John Longhurst

By Carolyn Chen (Princeton University Press, 2022, 254 pages, $17.95 US)

Reviewed by John Longhurst