20 minute read

ARCHITECTURE New and old builds are explored and discussed by Bath’s leading architects

by MediaClash

NOW AND THEN Bath architects share their favourite historical and contemporary Bath building

By Sarah Moolla

Advertisement

Architecture, both new and old, defi nes a city. We may marvel at the rich architectural history of Bath from the Royal Crescent to the Roman Baths but good modern architecture also has the ability to inspire, and invoke wonder. Together they create impact on our response and reactions to our surroundings. To explore this further, we asked eight local architects to talk us through their favourite old and new Bath buildings.

John Wood House is situated at the western end of Bath Street

© BATH STREET BY CHARLES / FLICKR

KEVIN MURPHY, Chartered architect and managing director Aaron Evans Architects; www.aaronevans.com

THEN

JOHN WOOD HOUSE “There are of course many significant and well-recognised historic buildings in Bath dating from the Georgian period. However, perhaps less well known are those that comprise the St John’s Hospital precinct.

“John Wood House is situated at the western end of Bath Street, immediately behind the Cross Bath and encloses the eastern side of Chapel Court. In 1726 James Brydges, Duke of Chandos, was visiting Bath to take the waters with his wife Cassandra and was not impressed by the quality of lodgings available. In 1727, seeing an opportunity, Chandos employed John Wood the Elder, aged just 22, to rebuild the existing lodging houses in the newly fashionable Palladian style envisioned by Wood.

“In 1728 Wood was again employed to build Chandos Buildings (since demolished) and another lodging house at the western end of Chapel Court known, today, as Chandos House. This is situated on Westgate Buildings, opposite Halfords. Over the following 200 or so years further buildings were developed to create the complex of buildings we see today, including Fitzjocelyn House and Chapel Court House.

“Many of the existing buildings, including John Wood House, continue to provide alms-house accommodation for the vulnerable elderly today. Chandos House was refurbished and converted into high quality apartments for the elderly in 2018. All are managed by the St John’s Foundation.

“Whilst not as grand as his later set pieces such as The Circus and Queen Square, or as substantial as The Royal Mineral Water Hospital or Prior Park, they represent an important part of John Wood the Elder’s early career, contributing significantly to the Bath we see today.”

NOW

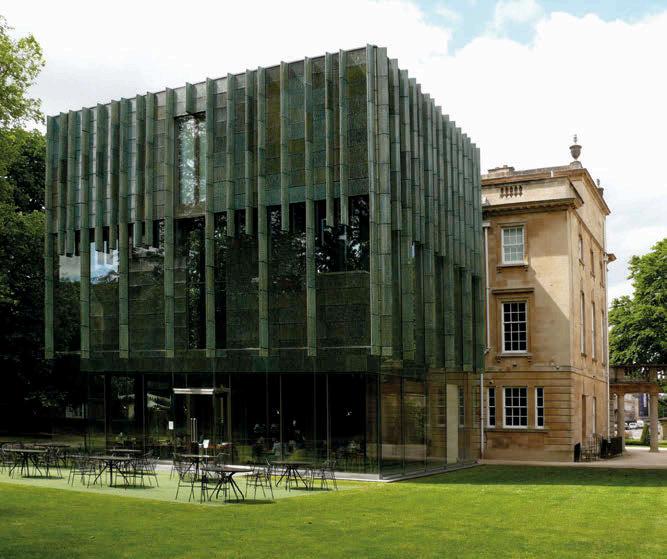

EXTENSION TO THE HOLBURNE MUSEUM “Situated at the end of Great Pulteney Street behind the grand façade of what once was the Sydney Hotel, the Holburne Museum extension makes a dramatic impression on the adjacent Sydney Gardens and Kennet and Avon Canal. Designed by Eric Parry Architects, it was completed in 2011.

“The extension was built as part of the overall refurbishment of the Museum and houses the collection of Sir William Holburne, the fifth baronet of Menstrie. This includes bronze sculptures, silver, porcelain and paintings by Gainsborough and Stubbs. The extension provided much needed additional exhibition space with more than 60 per cent of the exhibits now on show previously held in storage. The building also facilitated new disabled access, a well-frequented café accessed from both within and from the gardens to the rear alongside an educational facility.

“The building is wholeheartedly contemporary, not constructed from Bath stone, standing jewel-like alongside its historic counterpart. The dark green ceramic exterior cladding and glass signals the nature of the collection within whilst reflecting the trees and grass surrounding it. Inside views of the surrounding outside vegetation also ensure a strong connection between the interior spaces and their setting.

“This modern intervention has widened the appeal of the museum, created a ‘must visit’ destination within the city attracting temporary exhibitions by contemporary artists such as Bruce Munro and Grayson Perry. The extension, of course, makes no attempt to be ‘in keeping’ in terms of materiality or aesthetic but the sense of rhythm and proportion, in my view, compliment rather than detract from its historic host.”

© HOLBURNE BY ANDREW WARRAN / FLICKR

The Holburne extension built in 2011 provided much needed additional exhibition space

BEN SMITH, director of Batterham Smith Architects; www.batterhamsmitharchitects.co.uk

THEN

EAGLE HOUSE “Going slightly outside Bath I’m opting for Eagle House in Batheaston. It is at 71 Northend and anyone who passes, as I do on my intermittent jogging route from our studio towards St Catherine’s Valley, will recognise it for its striking eagle above the pediment on the east façade and wonder about its history.

“It is thought the house was built late 17th century but its signifi cance is that it was remodelled by Bath’s master architect John Wood the Elder as his own house, fi rst in 1724 and then in 1729. It is John Wood’s fi rst known building in the Bath area, prior his better known Bath masterpieces such as Queen Square and the Circus, but for me it is its more recent history that is fascinating and inspiring.

“If you believe that great buildings inspire the people who live in them, then you will be charmed by the history associated with Eagle House. Owned by the Blathwayt family at the end of the 19th century, the house must have been a hotbed for critical discussion. The extensive library was centred on nature and botany, with daughter Emily a passionate gardener.

“The house however became most famous for its focus for the suff ragette movement providing refuge for suff ragettes including those who had been released from prison after hunger strikes. Bringing together her passions for nature and women’s suff rage, Emily planted individual trees to commemorate the women’s achievements, creating an arboretum in a fi eld close to the house at the foot of Solsbury Hill.

“Sadly only one Austrian pine is said to survive and the house has now been split into apartments, but if ever there was a local building with an inspiring story of politics and ecology intertwined that could provide an inspiration to us all then it is Eagle House in Northend.”

NOW

CAMDEN MILL – BURO HAPPOLD OFFICES “Camden Mill is on the Lower Bristol Road and adjacent to the canal, and is the offi ces for the progressive engineering fi rm Buro Happold. A former steam-powered fl our mill constructed in 1879-80 and designed by a recognised regional architect of industrial buildings, Henry Williams of Bristol.

The Corridor – a little piece of glitzy pre-Victoriana

“Living on a boat in Bristol harbour, I am always seduced by the creative reuse of industrial buildings – particularly those alongside the water. The waterways and their historic buildings provide an important but sometimes forgotten life within the city, Bath being no exception. The boats on our canals after all fulfi l an interesting and alternative housing need. By breathing new life into these important historical buildings these stories and life of the city can continue.

“A bold industrial building encourages a bold design in response. The refurbishment was completed in 2008 and is recognisable for its brightly lit louvred drum hinting at the internal transformation. The designers of this building, Design Engline, have retained important historic elements – the hoists above the canal are crying out to be reused whilst contemporary elements such as the brightly lit entrance beacon hint at the light fi lled transformation inside.”

RICHARD LOCKE, associate director of BBA Architects; www.bba-architects.co.uk

THEN

THE CORRIDOR “My preferred historical building is The Corridor – a shopping arcade designed by Henry Goodridge and completed in 1825. It marks the end of the Georgian period and a transition to the more industrious Victorian. “It is one of the earliest examples of an indoor, covered shopping arcade. I particularly like the entrance features, columns, canopy and lettering. The internally glazed roof lanterns are very appealing. It’s a little piece of glitzy pre-Victoriana which is still enjoyable today.”

NOW

20 MANVERS STREET “A fi ne example of a modern design in Bath, for me, is 20 Manvers Street, a city centre refurbishment with rooftop extension. It was completed in 2017 by Stride Treglown and their client CBRE Global Investors. I particularly like its bold clean look with its views over the city from the glazed top fl oor. It is rentable offi ce space which may now become an outdated model in these pandemic times and it too may mark the end of an era – working in an offi ce!”

© BATH’S CORRIDOR BY BAZ RICHARDSON / FLICKR

OPPOSITE PAGE, TOP LEFT: Eagle House provided refuge for suffragettes; TOP RIGHT: Architects Design Engine have retained important historic elements in their work with Buro Happold; BOTTOM: The roof top extension of 20 Manvers Street offers views over the city from the glazed top fl oor

© WWW.STRIDETREGLOWN.COM © JONATHAN MOORE/ WWW.DESIGNENGINE. CO.UK

TOM BURNFORD, director at Burnford Architecture; www.burnfordarchitecture.com

THEN

SOMERSET PLACE “My favourite Georgian structure in Bath is actually an ensemble of buildings: the Lansdown CrescentSomerset Place extended terrace. The thing that makes this so special is its uniqueness. “I can’t think of anywhere else that so successfully transfers Baroque ideas into the realm of urban design – in the UK at large – but maybe even in Europe. While we often see these beautiful curved forms in places like Italy – at individual church façades by Borromini or Bernini, say – to go on to apply that to the city at large is quite a feat. What’s more, it is a response to the specific natural landscape of Bath – inextricably linked to its site, and largely unrepeatable.

“The curves over the hillside, from convex to concave, both laterally and horizontally, are an exceptionally elegant and successful work of Georgian architecture. A final point to note about this is the fact that it was constructed collaboratively. It was not brought into being by the acts of any kind of remote and powerful individual. It is a very cohesive sequence of buildings for what is essentially a group of individually owned houses, and I think that also adds something to them overall.”

NOW

THERMAE SPA “I think the most successful new work of architecture in Bath is the Spa building by Grimshaw. It not only uses a form and palette of materials that contextualises it successfully, it also restores and enhances nearby historic buildings, giving them renewed purpose. It has reinvigorated the area socially – by making positive impacts on public health and wellbeing, and it is good for the city economically. This is the holy grail for me of a good architectural intervention.

“Overall my feeling is that where architects have worked with an existing structure and then gone on to enhance it with discreet but unapologetic contemporary additions – contextually – the results are successful. The Egg Theatre also springs to mind by Haworth Tompkins and also the recent conversion of the Herman Miller Building. I find it really heart-warming that the same architect who built it originally has been able to continue his design journey at this site.”

Somerset Place, numbers 5-20

The Spa building by Grimshaw has reinvigorated the area socially

© JOHN LAW

© JEREMY FENNELL / FLICKR

HANNAH YOELL, senior architect with DKA; www.dka.co.uk

THEN

HOLBURNE MUSEUM “Originally the Grade I listed Holburne was designed as a hotel for Sydney Pleasure Gardens and was opened in 1799. It later became a private mansion before becoming home to the museum in 1916. Situated at the top of Great Pulteney Street, which is one of my favourite approaches to our Georgian city, I can imagine the Georgian ladies in their finery promenading down the wide pavements, indeed on occasion you can still see ladies in Georgian costume.

“The Holburne itself is an example of a Georgian building

Where old meets new at the Holburne Museum MARK LORD, founder of Lord Architecture; Its sense of grandeur remains but also its fairly bijoux proportions as trees and the hillside beyond. The unapologetically modern piece of architecture reflects its immediate surroundings of the Holburne’s garden and its wider context approach of Sydney Gardens, originally designed as Georgian pleasure gardens.

“Its chameleon glazed tiles and glass seem to shimmer and change with the seasons – this is what makes it my favourite modern building.

“It balances sitting quietly behind the original Georgian building and having its own identity as a garden pavilion. The brave choice of an alternative to Bath stone, so frequently used in modern interventions in our city, allow it to be clearly separate from the original Georgian building, which stands on its own merits.

‘I think that the success of the original building and the extension are the relationship that the two have; quietly respecting each other and each carrying out their own purposes. The original building housing activities that suits its original proportions and the modern meeting the stringent technical requirements of housing a collection www.lordarchitecture. co.uk

THEN

WIDCOMBE MANOR “Widcombe Manor is situated to the south of our UNESCO World Heritage City, and is a Grade I listed building, originally constructed in the mid 17th century and later rebuilt in the early 18th century. “The original dwelling is thought to have been designed by Indigo Jones. The manor is a private residence with an attached cottage, and is famous for its ornate detailing and benefits from substantial formal gardens and wider grounds including a lake, a grotto, a contemporary pool house and a Venetian 15th century fountain, which is listed as Grade I. “Architecturally the south elevation is of particular note; ornately detailed with fluted ionic pilasters; a central elliptical oculus window and modillion cornice with parapet beyond; open balustrades with terminal urns and armorial shields to the upper east and west. This elevation is also the primary public view from Church Street, opening out beyond the aforementioned repurposed for modern day culture. From the principal elevation the photographed by tourists and local residents admiring its splendour. building retains a sense of its original setting with a sweeping drive and “Widcombe Manor also holds a personal affection by association; railings. As you enter the building its proportions remain intact and the my wife and I were married and each of our children baptised at the original staircase, worn by generations of people exploring the building. adjacent St Thomas’ à Becket Church.” a mini mansion on the edge of the city.” NOW NOW “One of the most successful contemporary schemes of recent years is HOLBURNE’S MODERN EXTENSION the Thermae Bath Spa. The project encompassed the restoration and “The Holburne’s modern intervention is a secret jewel behind the formal adaptation of a collection of Grade I, Grade II* and Grade II listed Georgian façade . My primary approach to the city is often from the buildings, including The Cross Bath, 8 Bath Street, The Hot Bath canal path through Sydney Gardens and Eric Parry’s modern extension and The Hetling Pump Room. The ‘New Royal Bath’ successfully signifies the start of my arrival in the city. demonstrates that uncompromising modern architecture can not only

“I think that it perfectly captures Bath as a modern city in a rural exist alongside historic buildings, but it can enhance their setting and the setting. Wherever you are in our city, you can look out and see the user experience.

extension accommodating more complex requirements such as lifts and highly controlled gallery environments, which would otherwise have compromised the original building’s features. “Recently I’ve witnessed its success as a safe gathering haven for outdoor coffee, spilling into its gardens with gallery spaces above, © PHILLIP SMITH

Venetian fountain and cast-iron gates and is often THERMAE BATH SPA for future generations.” Widcombe Manor was originally constructed in the mid 17th century

Thermae Spa is a masterclass in the delivery of contemporary architecture alongside our ancient heritage

“The Thermae Bath Spa is located within Bath’s spa quarter in the heart of the city, funded as a joint venture between B&NES, the Millennium Commission and Thermae Development, and is rumoured to have cost circa £40m. Following an initial design competition, which attracted over 140 entries, it was designed in a collaboration between Sir Nicholas Grimshaw & Partners, and Donald Insall Associates, and was completed in 2006.

“The completed scheme is a state-of-the-art spa complex allowing local residents and tourists alike to enjoy the natural thermal waters as the Celts and Romans did circa 2000 years before.

“The complex simplicity of the modern building and its use of materials and geometry to both relate to its historic context and yet remain clearly of its own time is incredibly successful. From within, the high-performance glazing allows natural light to penetrate deep within the floor-plan, whilst providing both far reaching and context views or privacy depending on where you are in the building. From without, the use of Bath stone (Ashlar) sourced from a local quarry allows the building to nestle seamlessly into its surroundings.

“The use of geometry, texture, light and colour work to create a language between the old and the new whilst allowing each building to be clearly detectable and celebrated in its own right. This careful consideration by the team of architects, designers, planners and developers is a masterclass in the delivery of contemporary architecture alongside our ancient heritage.”

DANIEL LUGSDEN, partner at Nash Partnership; www.nashpartnership.com

THEN

THE OLD POLICE STATION, NOW BROWN’S RESTAURANT “I’ve always been drawn to the Old Police Station on Orange Grove, now the Browns Restaurant, built in 1865 by Charles Edward Davis. Before I even knew it was the Police Station, I thought it effortlessly displayed real strength as a building, but at the same time such elegance.

“Even though it has plenty of layers to its detailing, in the window reveals and heavily rusticated ground floor (giving real depth and an air of impenetrability), it also has such simplicity to its overall composition in

The Old Police Station still retains a sense of demanding respect

its Romanesque revival style.

“A strong building, but a sense of being delicate at the same time… the keeper of the law…firm but fair! Its tall, fine-panelled double doors remind you that you are entering an important building, oversized and strong, demanding some respect. You just wouldn’t see doors like that on modern municipal buildings any more.

“Now a restaurant, you use the old cells when you pop to the toilet. That sort of re-use in a building is such fun, and it is so important not to underestimate its power in successfully transforming and reusing buildings. The Empire hotel alongside dwarfs it now, which was built almost 40 years later, with of course the Abbey opposite, but I feel it still holds its own amongst a context of some of Bath’s most prestigious and large scale buildings.”

NOW

BURO HAPPOLD’S BIN STORE “I’d like to put a little focus on the importance of the buildings between buildings. In a city like Bath, with its World Heritage status, there will only be so much you can do (in the centre of the city certainly) without risking dominating what is a very protected character area. A successful way of introducing contemporary buildings is to do so in the gaps between, but without over stating. Contemporary with a bit of modesty.

“I love the Buro Happold bin store – it’s a delightful little building, sat alongside its older industrial brother. It’s well-crafted, introduces a little colour, has some rhythm, and some depth of shadow. It also looks well engineered, so no surprise it’s attached to Buro Happold’s studios.

“This is also nice as what is presented outside, represents what is going on inside. It’s light in its presence, so it counteracts the heavy nature of building next to it.Little pockets of relief amongst an overriding character style help enhance a place. Finding the balance is a fine line, but that’s our role as architects – to find that line without crossing it.”

Sometimes it’s about finding design ‘in the gaps’ like this Buro Happold bin store

The Widcombe site also sits adjacent to the canal allowing waterside views

DOUGAL ANDERSON, divisional director at Stride Treglown; www.stridetreglown.com

THEN

GREEN PARK STATION “Green Park Station sits as a transitional piece of architecture that had to deal with the arrival of a technology which changed the whole country – the railway. Thus in its way, it is quite uncompromising, with much of the building being constructed in iron, glass and timber.

“However, it also displays the classic duality of Victorian railway stations where engineering and architecture were separate entities, the This is a challenge which is similar to that which face many modern formal street façade being classically inspired and detailed in Bath stone, architects working in Bath! whilst the structure over the railway platforms is a pure essay in elegant “Another aspect of the building’s delight is that it was designed to and economic engineering. be used by the public. The fact the railway is no longer present has not

“The building is interesting as it was a new addition into the prevented the building to still be part of the city. It is happily utilised now, established Georgian city, opening in 1870. The scale of the building was still with public access, forming part of many Bath locals’ everyday lives, ultimately derived by its use as a terminus station for steam trains, but whereas it could have easily become a relic of a bygone age.” the significant decision, which informed the size of the building, was to provide a completely covered platform. This meant the architects from NOW the Midland Railway Company had to design a large clear spanning WIDCOMBE SOCIAL CLUB building of a height which competed with nearby Georgian terraces. “The new buildings that replaced the former Widcombe Social Club, which was housed in a sprawling and inflexible building. To make the project work, the new designs had to be of a larger scale than the previous building so that the Much of Green Park is constructed commercial aspects, which helped fund the construction in iron, glass and timber of the new social club, could be integrated. “This was accompanied by the challenge of terminating the vista along Widcombe Parade, whilst having to complement the backdrop of St Matthew’s church as the site rises up Widcombe Hill. “One of the delights of the location was the fact that the site also sits adjacent to the canal, allowing waterside views. The design approach is modern, but informed by the local context of the surrounding buildings. The result is relatively understated so that the buildings appear as part of the townscape rather than making a statement. “As part of the understanding of the locality, the designs present a relatively formal connection with © RICHARD SCHOFIELD Widcombe Parade whilst becoming less formal moving away from the main street. In particular the canal side elevations are reflective of the waterside environment taking its aesthetic cues from vernacular and industrial architecture. “The pleasure of the completed design comes from witnessing a modern building which maintains its modern qualities, yet seems to knit well into the traditional street scene.”