MEDICAL DIALOGUE REVIEW

FALL 2022

Volume 16 | Issue 1

FALL 2022

Volume 16 | Issue 1

Volume 16 | Issue 1

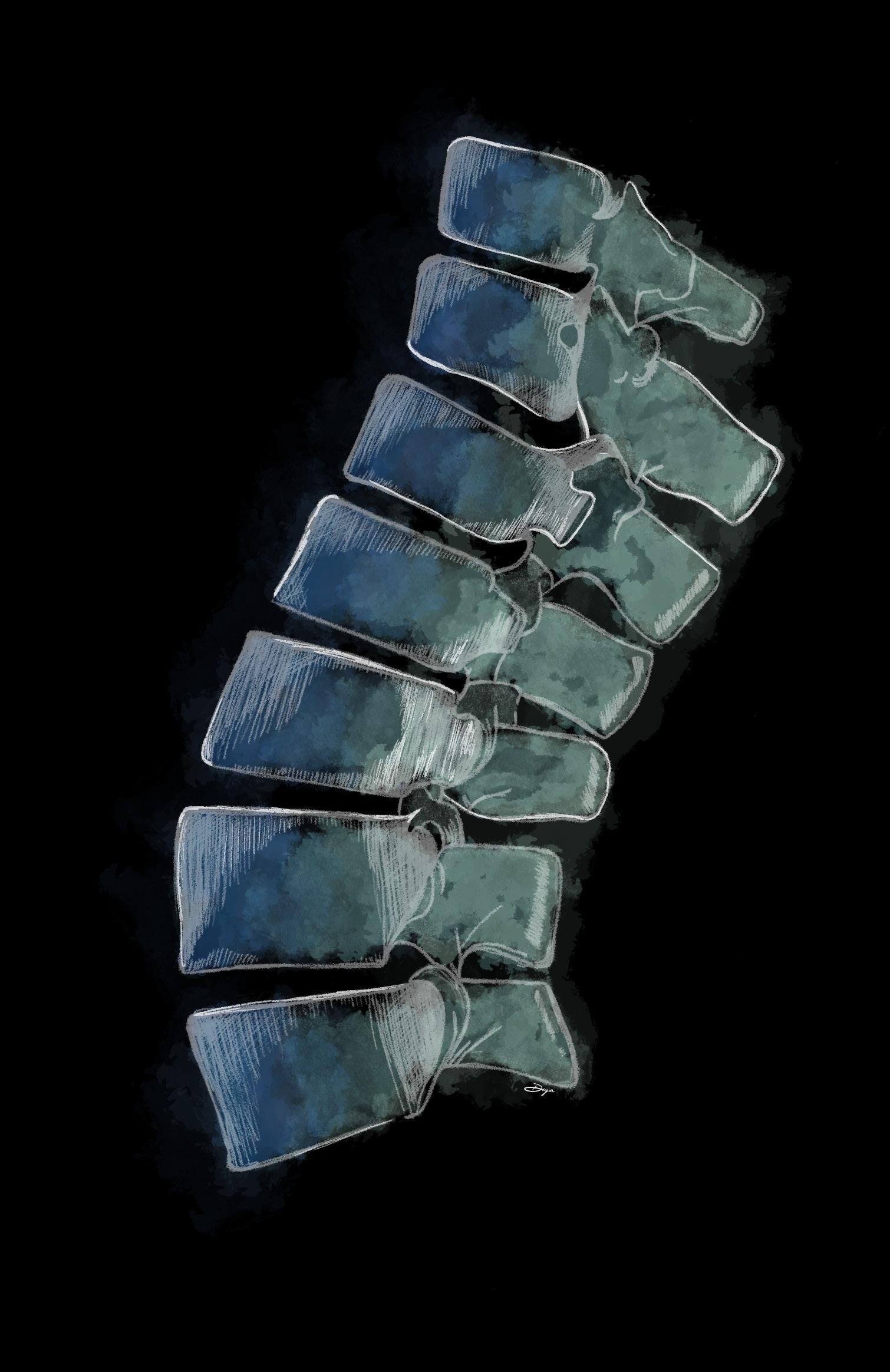

Diya Cherian

Izzah Nazir

Alyssa Khoo

Kyara Ralliford

Joseph Lee

PRESIDENT

Alyssa Khoo

VICE PRESIDENT

Maimunah Virk

SECRETARY

Brooke Bennett

TREASURER

Natalie Hohler

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Chloe Gammon

Marlena Kuhn

Selina Xue

Tony Deluxe

Julian Cortes

Varshini Ganesh

Amitra Hoq

Clara Wang

Rachel Matayev

Sarah Hoyos

Siri Kanakamedala

Jennifer Lim

Natalie Ito

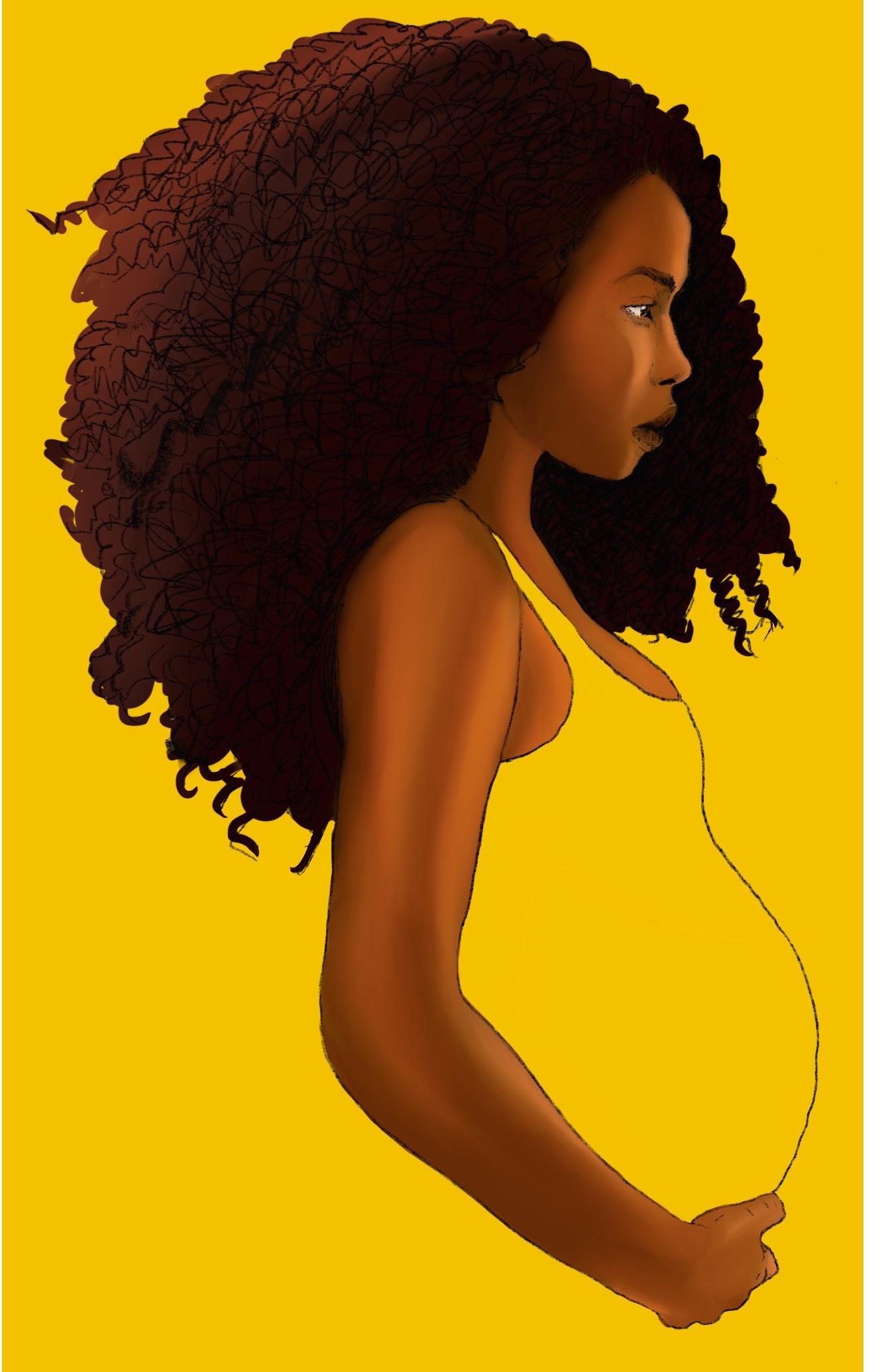

Jesus

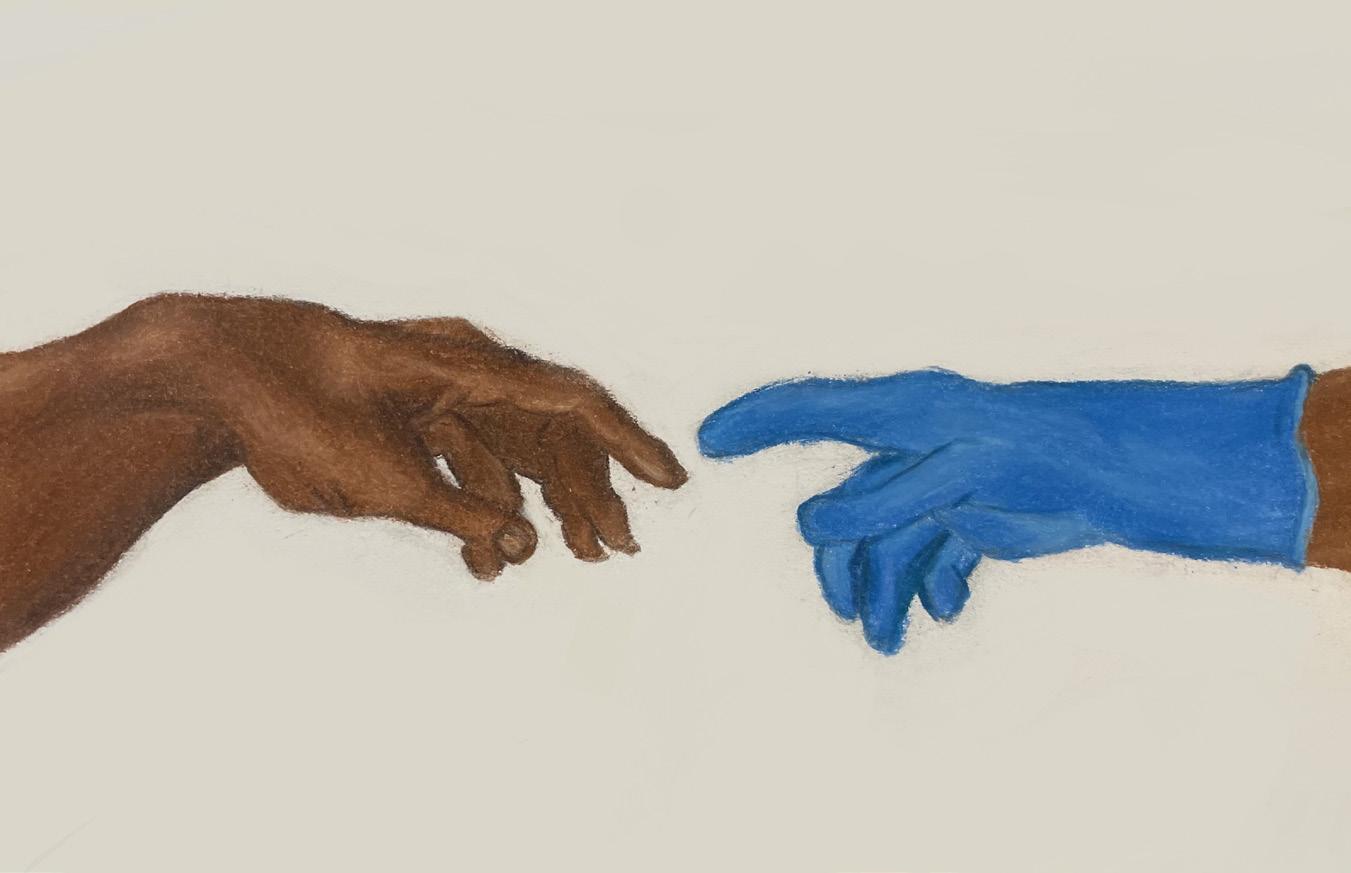

“The painting was based on the mistreatment of women in maternity care, labor, and delivery during the COVID-19 pandemic. I wanted to convey the form of a pregnant woman against the darkness of mistreatment surrounding her while she remained strong and proud through this time.”

ARTISTS

Gabe De Jesus

Diya Cherian

Ashley Quarless

Mishal Shafique

Emily Lu

Ashley Kim

Lucy Gammon

Natalie Hohler

Rachel Wu

Ashley Tay

Anvita Guda

Brianna Strauss

Mae Mensah-Bonsu

Bindu Koyi

Shiranjani Iyengar

Diya Cherian

MEDICAL DIALOGUE REVIEW (MDR) — FALL 2022 | VOLUME 16 | ISSUE 1

MDR is a New York University (NYU) student publication. We publish biannually and accept articles, essays, literary pieces, reviews, art, and photography relevant to healthcare.

DISCLAIMER

The contents of the journal, Medical Dialogue Review (MDR), represent perspectives of students, professionals, and patients on issues in healthcare. These ideas represent neither the opinions of the entire MDR membership nor the institution, New York University (NYU). Information presented is reviewed for accuracy but should not be used for medical diagnosis or as a substitute for medical advice. NYU is not responsible for its contents.

We are so proud to present the twenty-eighth edition of Medical Dialogue Review. As NYU’s only undergraduate medical journal, we serve as an outlet for students to express their views on a diverse set of contemporary issues in healthcare. Our objectives are to bridge the gap between the medical sciences and the humanities and foster discourse around critical aspects of modern medicine. Aside from our publication component, Medical Dialogue Review functions as a collaborative team of students who share the same passion for medical research and provide support for one another’s ideas.

In our Fall 2022 issue, we are showcasing a variety of topics from the pharmological treatment of grief to the history of misogynoir in medicine. With several articles covering COVID-19’s detriment to the healthcare system, this edition demonstrates the sweeping impacts of the pandemic, two years after its initial impact on the world. Despite the challenges posed by COVID-19 to our organization, our writers maintain their motivation to explore new pockets of medical research and convey new valuable ideas to our readers. This edition also presents imaginative artwork and literature made by our talented creatives, visually illustrating the student perspective on healthcare in current times.

We would love to acknowledge the writers, editors, and creative staff for all their incredible contributions and dedication throughout the process of curating our Fall 2022 issue. A special thank you to our impressive editorial staff who worked diligently to produce a beautiful publication.

Best wishes,

PRESIDENT

Diya Cherian EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

PRESIDENT

Diya Cherian EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Chloe Gammon CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Chloe Gammon CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Maimunah Virk VICE-PRESIDENT

Brooke Bennett SECRETARY

Natalie Hohler TREASURER

Maimunah Virk VICE-PRESIDENT

Brooke Bennett SECRETARY

Natalie Hohler TREASURER

Women, Maternity, and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Izzah Nazir

Maternal Mortality: The Delayed Diagnosis of Post-Partum Hemorrhage

Alyssa Khoo

A History of Misogynoir in Medicine

Kyara Ralliford

The

Navigating Euthanasia Marlena

Since the COVID-19 pandemic swept the nation, the United States healthcare system has proved time and time again its inability to provide adequate aid for needs of the moment. Government officials and healthcare institutions have struggled and deliberated back and forth about how to proceed with providing care to patients while mitigating the transmission of the virus. Newfound limitations on essential resources (e.g. personal protection equipment, toilet paper, etc.) and the unknown severity of a contagious virus generated nationwide panic and impulsive behaviors such as hoarding toilet paper and hand sanitizer. This panic and impulsive behavior may also serve as precursors for a phenomenon that has only worsened as time has progressed: the abuse of women of color’s health rights, specifically in maternal settings. Such abuse includes mistreatment towards those giving birth, violations of informed consent and bodily autonomy, and limited access to healthcare services (“The COVID-19”). Many of these result from drastic disparities among individuals’ social determinants of health as well as phenomena ingrained into American institutions, such as systemic racism. Systemic racism towards women has been ingrained in American society long before the COVID-19 pandemic. One case that occurred before slavery was abolished in the United States particularly highlights this. In 1855, 19-year-old Missouri enslaved African American woman Celia was put on trial for killing her master, Robert Newsom (D. Brown). She had done so after enduring five years of sexual violence including being raped on the day

of her purchase and being forced to bear three of her master’s children (D. Brown). While her court-appointed lawyers argued that a Missouri law permitting a woman to use deadly force to defend herself against sexual advances should be extended to enslaved as well as free women, the court ruled that Celia was property and not a person and could therefore not be raped (D. Brown). Ironically, the court decided that she had enough agency to be punished as a murderer and was sentenced to

death by hanging on December 21, 1855 (D. Brown) Ultimately, health and legal inequalities observed among women of color today are rooted in slavery.

Additionally, in 2012, 31-year-old African American woman Marissa Alexander was sentenced to 20 years in prison for firing a single gunshot into the air to ward off her estranged, abusive husband (Christine Hauser). She had been charged with aggravated assault after a mere 12-minute deliberation and was told

Given the prevalence of systemic racism in American society, the mistreatment of women of color in maternity care and labor and delivery is at an all-time high, especially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

that she was ineligible to invoke the “Stand Your Ground” law (stating that an individual may resort to deadly force so long as they believe that such force is necessary to avert harm) because she did not appear to be afraid (Hauser). This same law has been used by White individuals numerous times in order to exempt themselves from being punished for crimes they committed against Black individuals (Hauser).

While self-defense laws are interpreted generously when applied to White people who feel threatened by people of color, they are applied very narrowly to women of color. Institutional racism has been an issue for decades and has only exacerbated the mistreatment of women of color, coupled with the devastating effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the prevalence of systemic racism in American society, the mistreatment of women of color in maternity care and labor and delivery is at an all-time high, especially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The reason these issues came to be in the first place comes down to social determinants of health. Social determinants of health refer to the conditions in the environment where people live, learn, work, and play that affect different health and quality of life outcomes (“Social”). These include access to healthcare, socioeconomic status, education, neighborhoods, and social or community contexts (“Social”). For years women of color have

tended to have poorer access to prenatal health due to systemic racism in American society and the healthcare system. On average, this lack of access to quality care has led to pregnancy complications failing to be identified early on, and possibly induced irreversible damage to many individuals’ health.

Additionally, the disparities that women of color face in regard to their socioeconomic status may also be reflected in certain privileges they are unable to access as opposed to their Caucasian counterparts. This includes being able to afford care from birthing centers, midwives, or doulas. A birthing center differs from a hospital in the sense that they emphasize creating a home-like atmosphere for maternity care and provide services including prenatal care, childbirth education, breastfeeding classes, postpartum care, and support (Brown). Doulas and midwives are trained individuals that provide individualized support and sometimes medical care for mothers during the birth and postpartum periods. Birthing centers are generally not located within communities of color or those of lower income since many are owned by white women in more affluent areas (Doherty). Furthermore, less than 2% of doulas and midwives are Black and only 13 of the 400 birth centers nationwide are POC–owned (Doherty). This provides less accessibility

and support for women of color and thus makes it harder for them to receive quality care and feel secure with their providers.

It is evident that the mistreatment of mothers has grown exponentially since the onset of the pandemic and has exacerbated the racial and gender disparities present in the American healthcare system. One in six women who had hospital births in the United States reported experiencing one or more types of mistreatment including loss of autonomy, being shouted at, scolded or threatened, and being ignored, refused, or receiving no response to requests for help (Vedam). For an incredibly painful process in which a woman is arguably in her most vulnerable state, it is appalling how dismissive providers can behave toward them.

Mothers have especially indicated complications with their pregnancies or births after the onset of the pandemic. These complications ranged from gestational diabetes, HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count), intrauterine growth restriction, high blood pressure, polyhydramnios, and hemorrhaging (Davis-Floyd). Stress levels also spiked in pregnant women, mainly due to feelings of fear and isolation brought on by the pandemic. Pregnancy alone is already a stressful experience, with rapid physical changes, surges of hormones, and preparing for a major shift in societal dynamics. Combined with the pandemic, it results in pregnant women terrified about the lack of data on outcomes that the coronavirus has on them and their unborn child (Davis-Floyd). The stress doesn’t end after birth, however. Due to quarantine and social distancing restrictions enforced in 2020, many women who gave birth that year were unable to have their loved ones accompany them in their hospital rooms which only fur-

ther intensified feelings of isolation (Davis-Floyd). Some also reported feeling a lack of support and an inability to breastfeed their babies due to them being unable to receive in-person lactation consulting (Davis-Floyd). Adding on to this, women who already had children experienced a major hit to their mood and ability to balance maintaining their relationships with their families while being forced to work from home under COVID-19 guidelines (Davis-Floyd).

As the pandemic has progressed, the same structural and institutional racism that influences disparities in maternal health outcomes influences COVID-19 outcomes as well (“The COVID-19”). According to the CDC, in communities with the highest burden of maternal mortality and morbidity, high rates of adverse COVID-19 outcomes are already evident, particularly high rates of infection and death among people of color (“The COVID-19”). Black and Latino people are also three times more likely to become infected with coronavirus and twice as likely to die from it compared to Caucasian people (“The COVID-19”). As mentioned earlier, communities of color have been denied equal access to essential resources (including high-quality medical care, education, employment, and resources that prevent illness and promote health) due to deep-rooted discrimination (“The COVID-19”). This goes quite far back in history in cases where Black women have been abused and objectified in the healthcare field. Specifically, they have been subjected to medical experimentation without consent, denied medication, and ignored after communicating life-threatening symptoms (“The COVID-19”). Unfortunately, these problems have been exacerbated since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. As New York City

became an early “hotspot” for coronavirus, residents of poor, Black, and Brown neighborhoods were treated in understaffed public hospitals with old equipment and less access to advanced treatments (repro). This led many of them to experience instances of neglect or die at much higher rates than their wealthy counterparts in private hospitals (“The COVID-19”).

Though there are ways for these individuals to try to make their pregnancies as comfortable and healthy as possible for themselves, the fact of the matter is that there are a plethora of factors that are out of their control that have been embedded in American institutions for far too long which prevent them from doing so.

1. Brown, Deneen. “Missouri v. Celia, a Slave: She Killed the White Master Raping Her, Then Claimed Self-Defense.” Washington Post. www.washingtonpost. com, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/retropolis/wp/2017/10/19/missouriv-celia-a-slave-she-killed-the-white-master-raping-her-then-claimed-self-defense/. Accessed 1 Nov. 2022.

2. Brown, Maressa. “Birth Centers vs. Hospitals for Labor and Delivery: What’s the Difference?” What to Expect, https://www.whattoexpect.com/pregnancy/ birth-center/. Accessed 2 Apr. 2022.

3. Davis-Floyd, Robbie. The Global Impact of COVID-19 on Maternity Care Practices and Childbearing Experiences | Frontiers Research Topic. https://www. frontiersin.org/research-topics/13930/the-global-impact-of-covid-19-on-maternity-care-practices-and-childbearing-experiences. Accessed 2 Apr. 2022.

4. Doherty, Joyce. “New Commission Focuses on Racial Disparities in Maternal Health.” Standard-Times, https://www.southcoasttoday.com/ story/news/2021/10/02/new-commission-focuses-racial-disparities-maternal-health/5947331001/. Accessed 2 Apr. 2022.

5. Hauser, Christine. “Florida Woman Whose ‘Stand Your Ground’ Defense Was Rejected Is Released.” The New York Times, 7 Feb. 2017. NYTimes.com, https:// www.nytimes.com/2017/02/07/us/marissa-alexander-released-stand-your-ground. html.

6. Social Determinants of Health | CDC. 30 Sept. 2021, https://www.cdc.gov/ socialdeterminants/index.htm.

7. “The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Exacerbating a Human Rights Crisis in Maternal Health.” Center for Reproductive Rights, 9 Sept. 2020, https://reproductiverights. org/the-covid-19-pandemic-is-exacerbating-a-human-rights-crisis-in-maternalhealth/.

8. Vedam, Saraswathi, et al. “The Giving Voice to Mothers Study: Inequity and Mistreatment during Pregnancy and Childbirth in the United States.” Reproductive Health, vol. 16, no. 1, June 2019, p. 77. BioMed Central, https://doi.org/10.1186/ s12978-019-0729-2.

BY ALYSSA KHOO

BY ALYSSA KHOO

A19-year-old pregnant woman is admitted to the labor and delivery unit at 35 weeks of gestation due to experiencing new hypertension. Due to concerns about preeclampsia and fetus viability, her obstetrician sends her to the operating room for an emergency cesarean section. The delivery goes without complications, however, after a few hours, the postpartum mother begins to experience increased hypertension and tachycardia which leads to great concern for pulmonary embolism. Her physician quickly orders tests which identify that the cause of her symptoms is not pulmonary embolism but extreme blood loss, presenting a dangerously low hemoglobin level of 3.6g/dL. At this point, she receives a delayed diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage and is rushed back into the operating room to receive blood transfusions. The obstetrician moves the patient to the ICU in critical condition where she requires mechanical ventila-

tion, vasopressors, and more than 10 units of blood. After an extremely difficult period of recovering from respiratory failure, shock, and disseminated intravascular coagulation, she is finally discharged from the hospital to an outpatient rehabilitation center.1

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is the most common severe complication of pregnancy, contributing to 50-75% of all instances of maternal morbidity, and its rate has been increasing in high-income countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.2 Following a proper diagnosis of PPH, around 20 million women continue to experience acute or chronic physical disability after an obstetric hemorrhage.3 The major cause of obstetric hemorrhage is uterine atony, which occurs when the uterus fails to contract after childbirth via vaginal delivery or cesarean section. If the uterus is unable to contract, the blood vessels where the

placenta was previously attached remain open and exposed. This leads to extensive bleeding and hemorrhage.1 Despite PPH being the most prevalent adverse outcome of childbirth across all countries, the definition of postpartum hemorrhage is not standardized in the field of obstetrics. Although there exists consensus regarding the recognition of postpartum hemorrhage, including visible signs of major blood loss and increased hyperten-

sion, the exact diagnosis of postpartum hemorrhage is inconsistent across different hospitals and medical providers. The lack of a universal definition of PPH, the most fundamental aspect of the medical condition, leads providers to overlook and misinterpret symptoms of hemorrhage, leading to further severe complications and increased physical trauma to affected women.

The primary source of ambiguity in the exact diagnosis revolves around the calculation of blood volume loss after childbirth. The most common indication of PPH, widely used in most Amer-

ican hospitals, is blood loss that exceeds 500mL for vaginal delivery, or blood loss that exceeds 1000mL for cesarean delivery. However, this definition is problematic, as it is difficult to quantify abnormal postpartum blood loss due to an expected amount of considerable blood loss during childbirth. Furthermore, there is no substantial medical evidence to support the idea that PPH criteria for blood loss volume should change between vaginal and cesarean deliveries. Still, due to being the most relevant and obvious indication of obstetric hemorrhage, blood loss persists as the predominant indicator of obstetric hemorrhage. The importance of accurate blood-measurement collection makes it necessary for improvements in blood quantification in obstetrics. For instance, physicians should measure blood loss in exact quantities to increase precision in calculation, such as gravimetric analysis of blood collecting bags or referring to hemoglobin concentration by blood sampling.4 Although these collection techniques are available for implementation, it is dangerously common for obstetricians and nurses to glance at and approximate blood loss based solely on what they can see, not what they quantify. Research presented by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists has shown that visual estimation is more likely to underestimate higher volumes of blood loss and overestimate lower blood loss, leading to inaccurate interpretations of a patient’s condition.5 Moreover, careful observation and tracking of maternal vital signs can lead to an accurate and proactive diagnosis of PPH. PPH is usually associated with obvious signs of hypovolemic shock, including weakness, fainting, and lightheadedness; early recognition of these symptoms can lead to faster responses.

Besides monitoring vital signs, medical

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is the most common severe complication of pregnancy, contributing to 50-75% of all instances of maternal morbidity, and its rate has been increasing in high-income countries, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia.

providers must establish open and comfortable lines of communication with the postpartum patient. An alarming source of concern in the delayed diagnosis of PPH is the neglect of warning signs coming directly from the patient, such as a woman describing her concerns about oncoming symptoms. In his study of PPH, Dr. Elliot Main, a clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Stanford University, lists the biased claims that physicians may make to avoid the diagnosis of PPH: “Hypotension is explained away as ‘the result of spinal or epidural anesthesia’… a persistent tachycardia is ‘because of pain.’ Women complaining of increased postoperative abdominal pain are just ‘overly sensitive.’”1 Dr. Main establishes the concept of gender bias as an influential factor in the denial and delay of treating obstetric hemorrhage. Some physicians refuse to acknowledge complications of pregnancy, attributing their valid concerns and worries to the “emotional” and physically weak state of postpartum women. A lack of attention and general reluctance to listen to patients are serious problems that may contribute to the exacerbation of preventable PPH complications. The exclusion of bias in obstetric treatment is necessary because it consumes time that should be utilized for the recognition and treatment of PPH, avoiding a harmful delayed diagnosis.

The severity and increasing frequency of PPHs require an extensive plan across all obstetric providers to efficiently respond to concerning postpartum symptoms. In 2015, The National Partnership for Maternal Safety, operating in the United States, formed a comprehensive outline for the proactive recognition and treatment of PPH. Using high-impact research, the organization established that readiness and preparation, including a strong line of communication with the patient and

immediate access to the blood bank and hemorrhage medication, could altogether avoid the elevation of PPH symptoms and severe outcomes. The obstetric hemorrhage emergency plan also includes a greater emphasis on measuring cumulative blood volume loss and constant assessment of patient risk during delivery.6 These concrete acts of recognition and prevention, including the elimination of biases that causes physicians to dismiss female patients’ concerns, can decrease the frequency of severe hemorrhage episodes, reduce the need for massive blood transfusions, and limit other serious complications.

In conjunction with the preventative measures that should be performed by a well-practiced team, certain medical devices have been utilized as a third line of treatment for PPH, after blood transfusion and medication. The most common technology with the highest success rate has been the balloon tamponade device, which is inserted directly into the uterus and further expanded to compress the uter-

us and stop excessive bleeding. However, new research from a recent clinical trial in the United States supports the use of the newly manufactured vacuum-induced uterine tamponade device in replacement of the balloon tamponade device. Instead of pushing against the blood vessel walls of the uterus, the vacuum-induced uterine control device utilizes vacuum suction to cause the uterine cavity to collapse. A collapsed and contracted uterus enables the closing of blood vessels, thus, controlling bleeding post-delivery.7 Medical studies have shown that the vacuum-induced tamponade device has a higher success rate and demonstrates greater efficiency than the balloon tamponade device to control excessive bleeding. Additionally, evidence supports that the use of the vacuum-induced intrauterine hemorrhage-control device reduces the need for other surgical or nonsurgical procedures after its usage.8 Currently, advanced hemorrhage-control technology and prospective PPH therapeutics are prominent areas of obstetric research, due to their efficacy in reducing

the rates of PPH complications and maternal morbidity.

The physically exhausting process of childbirth that women undergo is an extensive procedure that should not be further complicated by weaknesses and deprivations in medical treatment. Postpartum hemorrhage, a significant cause of maternal mortality, must be better understood and treated, in response to increasing rates of both pregnancy and post-delivery complications. While many of the ambiguities with the exact diagnosis of PPH are due

to physiological factors, an involved element of gender bias is a significant issue that delays the treatment of rapid and abnormal blood loss. Current advancements in research and technological innovations to treat PPH, such as the vacuum-induced tamponade device, offer crucial improvements to the clinical system and help favor more beneficial maternal outcomes. Critical attention to hemorrhage must remain a top priority in obstetrics to protect the health of all postpartum women.

1. Main, E. K. (2016, November 1). Don’t Dismiss the Dangerous: Obstetric Hemorrhage. Patient Safety Network. https://psnet.ahrq.gov/web-mm/dont-dismiss-dangerous-obstetric-hemorrhage

2. Nyfløt, L. T., et al. (2017, January 10). Risk factors for severe postpartum hemorrhage: a case-control study. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 17. doi. org/10.1186/s12884-016-1217-0. https://bmcpregnancychildbirth.biomedcentral. com/articles/10.1186/s12884-016-1217-0

3. Rath, W. (2011, February 18). Postpartum hemorrhage – update on problems of definitions and diagnosis. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavic, 90(5), 421-428. doi/10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01107.

4. Diaz, V., et al. (2018, September 13). Methods for blood loss estimation after vaginal birth. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9(9), doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010980.pub2.

5. Smith, C. (2019, December). Quantitative Blood Loss in Obstetric Hemorrhage. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 794. https://www. acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2019/12/quantitative-blood-loss-in-obstetric-hemorrhage

6. Banayan, J. M., Scavone, B. M. (2016). National Partnership for Maternal Safety - Maternal Safety Bundles. Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation. www.apsf.org/ article/national-partnership-for-maternal-safety-maternal-safety-bundles/

7. (2021). Vacuum-Induced Uterine Tamponade Device for Postpartum Hemorrhage. Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved March 27, 2022.

8. D’Alton. M. E. (2020, November) Intrauterine Vacuum-Induced Hemorrhage-Control Device for Rapid Treatment of Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 136(5), 882-891. 10.1097/aog.4138.

Among black women in the United States, there are whispers of a boogeyman. He’s cloaked in white, his smile menacing. The boogeyman does not hurt with sharp knives, but with ignorance. He shrugs off drops of tears and shuts the door to avoid painful cries. It’s an old tale, passed down from black mothers to their black daughters. Each generation learns to fear the boogeyman.

2011, one resulted in emergency treatment (Moisse, 2011, para. 1). Because of her past experiences, she quickly alerted a nearby medical professional, detailed her symptoms, and requested a CT scan and blood thinners. The nurse subverted her requests, labeling her as "confused". The doctor, too, ignored her requests, ordering an ultrasound when Williams fiercely requested a CT scan. The ultrasound showed nothing, but the CT scan displayed small clots obstructing Williams’ airway.

Serena Williams’ treatment is no isolated incident. The boogeyman of medicine frequently torments black women, forcing them to bear pain and discomfort in silence and limiting their medical agency. This boogeyman personifies misogynoir in medicine. It couples the already limited medical care for women with equally limited medical care for black people. These poor medical experiences have disrupted the comfort and survival of black female patients throughout history.

The boogeyman has crept over Serena Williams, an American tennis player. In Williams’ 2018 Vogue cover story, she describes her postnatal hospital stay. During this time, she felt the onset of a pulmonary embolism, a blood clot that lodges itself in a blood vessel, travels to the lung, and obstructs airflow. Williams has an extensive history of pulmonary embolisms—in

"Misogynoir" is not a typo; it’s a portmanteau—a combination of two words: "misogyny," the "dislike of, contempt for, or prejudice against women" (Oxford Languages), and the French word "noir," which refers to the color black. In short, misogynoir describes the "dislike of, contempt for, or prejudice against black women" (Oxford Languages). In 2010, black feminist scholar Moya Bailey coined the term in reaction to prejudice against black women in popular culture (Anyangwe, 2015, para. 3). The definition was then expanded to include prejudice against black

women in a broader context, one that includes the medical, legal, educational, and even romantic facets of society.

Misogynoir zooms into the intersection between race and gender identity. It describes a separate type of prejudice, one amplified by existing racial and gender bias. The distinction between women and black women is purposeful; it is equal to the distinction between a man and a woman, or a white person and a black person. The chaos and unrest from certain events cannot be felt by anyone who does not simultaneously identify as black and a woman. For example, can a man speak to the feelings of pregnancy? Can a white person in the 19th century speak to the turmoil of enslaved black people? With this logic, a white woman does not experience life exactly as a black woman experiences life.

According to Kimberlé Crenshaw’s Theory of Intersectionality (1989), intersecting identities—including but not limited to race and gender identity—may enable varying types of social privilege or social isolation. Chattel slavery (around the 16th to 19th centuries) and the culture preceding the Women’s Rights Movement (in the 1960s to 1980s) left residual effects on how black people and women are viewed. Preconceived notions about how black people and women should act are two separate burdens that black women must equally shoulder, and these burdens have real consequences. In the medical field, black women’s dual identities have put them at risk of facing both racism and misogyny. And this is a fact as old as time.

As this paper examines aspects of historical misogynoir, it is important to consider how the social identity of black women has influenced their treatment in both the past and present. How has misogynoir changed with the times? Has it changed at all?

When discussing the history of gynecology, a medical specialty concerned with the "medical and surgical care of the female reproductive system and associated disorders" (Vogt, n.d., para. 1), no other name shines quite as bright as J. Marion Sims, who was an American gynecological surgeon during the 19th century.

When discussing the history of misogynoir in medicine, no other name attracts equal loads of vitriol and grief quite like J. Marion Sims. A medical pioneer of the 19th century. A man committed to the health and wellness of women. The father of modern gynecology, they called him. But how did these epithets come to be?

Sims pioneered numerous tools and techniques, including the Sims’ position, where patients lie on their side and bend their opposing knee and leg so that physicians can better "[assess] … the vaginal walls for prolapse or fistula" (Naftalin & Glynn, 2012, p. 47). However, Sims’ most notable surgical technique repaired a consequence of labor: the vesicovaginal fistula, a condition in which the vagina is improperly connected to the bladder, resulting in urinary incontinence, an inability to contain urine in the bladder (Stamatakos et al., 2014, para. 1-3).

Sims would not have developed this surgical technique if not for the bodies of enslaved black women. Around the mid-1800s, Sims performed his fledgling technique on the bodies of 14 enslaved women, and these women would undergo "up to 30 painful operations" (Spettel & White, 2011, p. 2424). Of these 14 women, only three were named: Anarcha, Besty, and Lucy (Vedantam et al., 2017, para. 4). Lucy, "the poor girl, on her knees, bore the operation with great heroism and bravery," observes Sims himself (Gamble, 1997,

p. 1774). His comments appear to negate the controversy surrounding his work. In reports and autobiographies, Sims would portray himself as merely a product of a grotesque medical system that preached medical ethics but had to act antithetical to it (Spettel & White, 201, p. 2425).

Many would agree with him. After all, human experimentation is crucial to the development of medicine, and naturally, enslaved black women had less freedom to decline participation in Sims’ experiments. While this fact is true, the heat behind Sims’ controversial work stems not only from his experimentation on enslaved women but also from his unequal treatment of black and white female bodies. Gamble (1997) noted that Sims did not use anesthesia on black female patients, but he did on white female patients (p. 1774). This fact cannot be reduced to a matter of timing. While Sims expressed that he did not use anesthesia on Lucy because "[it] was before the days of anesthetics" (Gamble, 1997, p. 1774), there existed countless methods of pain control—opioids and alcohol, for example—before the mid-1800s. More modern methods of anesthesia broke ground within the first few years of Sims’ experiments on the vesicovaginal fistula (Robinson & Toledo, 2012). There is no report of Sims using any form of anesthesia on Anarcha, Besty, or any other black woman until he began operating on the white women who elected to undergo the procedure.

To Sims, black female bodies were practice dummies. He did not think to try his excruciating art form on a fresh canvas until he had perfected his techniques on a rougher, less cared-for muslin. Sims' treatment of black female bodies would come to mark a withstanding trend—the trend of medical misogynoir. Marion Sims was once well-respected for his contribu-

tions to gynecology. He laid the groundwork for the discovery and treatment of reproductive conditions that continue to plague women. But in light of his controversial past, his respectability has since diminished. The looming consequences of being a black woman in a medical space, however, remain.

Black women are given less, cared for less, and listened to less by medical professionals. By and large, the suffering of a black woman is not taken seriously enough to warrant a response similar to that of her white counterpart. For example, a study in the American Journal of Public Health found that the "maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black women was 3.55 times that for non-Hispanic White women" (MacDorman et al., 2021). Maternal mortality refers to deaths caused by complications during pregnancy, such as cardiovascular conditions, which are typically preventable (MacDorman et al., 2021).

This discontinuity of care between black women and white women stems from longstanding implicit bias. The beliefs that may contribute to these biases include the following: (1) Whites have larger brains than blacks. (2) Black people have thicker skin than white people. (3) Black people's nerve endings are less sensitive than white people's nerve endings. These biases were bred during slavery, with scientists, physicians, and philosophers conjuring extensive mythology about the biological and social functioning of black people (Byrd & Clayton, 2001). Even today, physicians believe these false constructions of blackness. A study published in 2016 reports that, of 418 medical students and residents, "50% reported that at least one of the false belief items [three of the items are mentioned above, numbered 1-3] was possibly, probably, or definitely

true" (Hoffman et al., 2016). These stereotypes, coupled with the requirements of the patriarchy, endanger black women by limiting their humanity.

Medical misogynoir carries a dual weight: the weight of remaining subservient to—typically—a male doctor in a "masculine" field, and the weight of remaining biologically inferior in the eyes of—typically—a white doctor. This combined weight makes existing as a black woman in a medical setting dangerous, as these perceptions of who black women are, and must be, are deadly. They loom over black women like an ever-present ghoul in the practice of modern medicine. Black women’s bodies have been mutilated, torn apart, and disregarded to maintain the subconscious perceptions of two antagonistic systems.

Certain practices in modern medicine contain some of the last remaining vestiges of a crude time period, one built on ignorance. Misogynoir threatens the lives and comfort of black women. It is an idle discomfort that eats away at black female physicians, nurses, and technicians who must bear the load of a system built to discard them. It has obliterated the fundamental trust that must exist between caretakers and the black women

who need care. Fortunately, there is hope.

As medical sociologists and historians further uncover the tales of mutilation of black female bodies, medical professionals are forced to reevaluate their biases—to wager their experiences for the safety of their black female patients.

This practice of reevaluation is key to unlocking and discarding the implicit biases that haunt black women in the medical field. For healthcare professionals to treat their biases, they must be willing to exercise restraint and "[treat] patients as experts" (Hostetter & Klein, 2021). Giving patients greater autonomy in their medical care is one of the few ways healthcare professionals can regain their patients' trust. For black women, this reallocation of expertise encourages doctors to consider previous medical experiences and desires for future medical experiences. This process allows patients to stand at the center of their care. Their hopes and fears are laid bare, and the physician is given a chance to treat a person, not just a condition. More so, the medical system must also restructure itself, providing space for the input of black female physicians, technicians, researchers, and policymakers. Only then can the cultural landscape of medicine be better suited to combating medical misogynoir. With these changes, the history of misogynoir in medicine will end with us.

1. Anyangwe, E. (2015, October 5). Misogynoir: Where racism and sexism meet. The Guardian. Retrieved March 25, 2022, from https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2015/oct/05/what-is-misogynoir

2. Byrd, W. M., & Clayton, L. A. (2001, March). Race, medicine, and health care in the United States: A historical survey. Journal of the National Medical Association. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2593958/?page=1

3. Gamble, V. N. (1997, November). Under the shadow of Tuskegee: African Americans and Health Care. American journal of public health. Retrieved March 25, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1381160/?page=2

4. Hoffman, K. M., Trawalter, S., Axt, J. R., & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(16), 4296–4301. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1516047113

5. Hostetter, Martha and Sarah Klein. 2021. “Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust among Black Americans.” Commonwealth Fund. Retrieved April 17, 2022 (https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2021/jan/medical-mistrust-among-black-americans).

6. MacDorman, M. F., Thoma, M., Declcerq, E., & Howell, E. A. (2021). Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal mortality in the United States using Enhanced Vital Records, 2016‒2017. American Journal of Public Health, 111(9), 1673–1681. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2021.306375

7. Moisse, K. (2011). Serena Williams Hospitalized After Pulmonary Embolism. ABC News. Retrieved March 28, 2022, from https://abcnews.go.com/Health/Wellness/serena-williams-hospitalized-pulmonary-embolism/story?id=13036965#:~:text=Tennis%2Dstar%20Serena%20Williams%20rushed,everything%20was%20 caught%20in%20time.

8. Naftalin, A. (2012). Assessment for Prolapse. In M. Glynn (Ed.), Hutchison’s Clinical Methods : An Integrated Approach to Clinical Practice (23rd ed., p. 47). essay, Elsevier.

9. Robinson, D. H., & Toledo, A. H. (2012). Historical development of modern anesthesia. Journal of Investigative Surgery, 25(3), 141–149. https://doi.org/10.3109 /08941939.2012.690328

10. Spettel, S., & White, M. D. (2011). The portrayal of J. Marion Sims’ controversial surgical legacy. Journal of Urology, 185(6), 2424–2427. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.juro.2011.01.077

11. Stamatakos, M., Sargedi, C., Stasinou, T., & Kontzoglou, K. (2014, April). Vesicovaginal fistula: Diagnosis and management. The Indian journal of surgery. Retrieved March 27, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC4039689/

12. Vedantam, S., Penman, M., Schmidt, J., Boyle, T., Cohen, R., & Connelly, C. (2017, February 7). Remembering Anarcha, Lucy, and Betsey: The mothers of modern gynecology. NPR. Retrieved March 27, 2022, from https://www.npr. org/2017/02/07/513764158/remembering-anarcha-lucy-and-betsey-the-mothers-of-modern-gynecology

13. Vogt, V. Y. (n.d.). Obstetrics and gynecology. American College of Surgeons. Retrieved March 25, 2022, from https://www.facs.org/education/resources/residency-search/specialties/obgyn

Today, medical topics and issues are frequently discussed as public and individual health are heavily emphasized by society. New technology and discoveries have launched medicine to new heights but as the field advances, so do the standards of care set by patients. More people have begun to pay attention to their physicians’ mannerisms, resulting in more people searching for top-level doctors.

With a demand for quality care, patients only want the best for themselves. Patients are beginning to desire stronger physician-patient relationships so they feel confident in their physicians and comfortable with the care they receive. Physicians must be able to display care, trust, and professionalism in order to meet patient expectations. But, this has not remained consistent throughout medicine’s history.

Medicine has not completely listened to patients’ wishes as the industry has become similar to a business. It is now being robbed of its roots with 15-minute visits6, quota requirements, and business-like models. As healthcare becomes less personal, the emphasis on physician-patient

relationships decreases. Physicians need to take the time to reflect on their responsibilities and understand the values, desires, and personality of a patient before advising a course of action. It is essential to have this insight to develop strong physician-patient relationships and ensure patient satisfaction.

A simple way to break down the behavior of a physician is to look at the four models of the physician-patient relationship: the paternalistic model, the informative model, the interpretive model, and the deliberative model.1

The paternalistic model is centered around the physician acting similarly to the patient’s guardian. Thus, the patients will more likely receive the interventions that are best for their health.1 The physician informs the patient of everything he or she needs to know and does everything within reason and ability to improve their quality of life. The paternalistic model’s objective is to ensure that patients receive the interventions that best promote their health and well-being.1 It allows for physicians to be directly involved to help pa-

tients and make critical decisions for their health. However, the paternalistic model assumes a patient’s values and desires which compromises patient autonomy and could lead to an abuse of power. The paternalistic model should only be used in emergencies where immediate action is necessary, such as emergency medicine and life-and-death situations.

The informative model’s objective is “for the physician to provide the patient with all relevant information, for the patient to select the medical interventions he or she wants, and for the physician to execute the selected interventions”.1 Though physicians will remain neutral, they lack the humanistic qualities needed to show care to the patient with solely relaying information. There is no requirement to guide patients or consider their values, and patients are left to decide on their own.

The improved informative model, the interpretive model aims to elucidate the patients’ values and what he or she actually wants and to help the patient select the available medical interventions that realize these values.1 Again, the physician discloses all relevant information to the patient but also attempts to understand the patient at an interpersonal level and give them a level of self-understanding. However, the physician could impose their values on the patient because of the counselor-like role taken. In addition, the physician risks multiple delays in treatment and recovery time because a patient’s emotions and values can change, resulting in treatment changes.

The last model is the deliberative model, which focuses on “help[ing] the patient determine and choose the best health-related values that can be realized in the clinical situation”.1 The deliberation between the physician and patient gives the

patient the opportunity to come to one’s own conclusion with physician guidance. It tries to help the patient understand their choices. Furthermore, this model enables the patients to choose which doctors they like the most so that they feel that they have control over their health. However, the fact that a physician tries to persuade the patient to a certain standpoint is similar to imposing their own views. The physician should remain unbiased throughout this process, despite the circumstances. The physician should give all the relative information like the informative model but also give the care and attention of the paternalistic model.

There are five expected requirements from patients: eye contact from their physicians, partnership, thorough communication, low wait times, and promptness with appointment times.4 Eye contact makes the patient feel that they are important during an appointment. 4 If a physician stares only at the computer screen for the entire duration, the patient does not feel important and loses respect for

Physicians need to take the time to reflect on their responsibilities and understand the values, desires, and personality of a patient before advising a course of action. It is essential to have this insight to develop strong physician-patient relationships and ensure patient satisfaction.

the physician. Patients want physician attention to know they are getting recognition instead of being ignored or neglected. Patients want partnership as well because they do not want to be told what to do, but guided towards making an informed, independent decision.4

Effective communication is also desired often because patients are often uncertain about the appropriate course of action to take, and the physician needs to explain symptoms, diagnoses, and treatments in a way that patients are able to understand easily. In addition, patients want as much time with a physician as possible.4 They want to be able to explain all of their worries and have the physician answer all of their concerns. Finally, patients want to have follow-up appointments or first-time appointments within a few days’ time.4 Waiting lists become very inconvenient as patients get restless and anxious because they want to address their problems as soon as possible. Therefore, physicians should understand that they are responsible for doing their best to fulfill these wishes. In order to convey that information to a patient, physicians must be good at communicating. Communication is key because it cultivates a good physician-patient relationship and establishes trust. Patients that report good communication with their doctor have a higher chance of being satisfied with their care and have an improved relationship with their physician.2

Losing good communication skills causes the loss of the benefits that patients need for their own knowledge. The intensity of medical school, avoiding discussions that have heavy topics, and not being attentive to patient information, social tendencies, and body language2 all stack on top of physicians and desensitize physicians to truly cultivate good

communication. Medicine becomes more analytical in medical school, and it takes away from the humanistic aspect of medicine. But physicians need to overcome this challenge and properly communicate information about diagnoses, treatments, symptoms, and risks to patients. One study in China showed that positive physician-patient communication increased treatment adherence of tuberculosis (TB).10 By “expounding knowledge about the prevention and treatment of TB to patients,” patients could comprehend the significance of treating their TB,10 and as a result, treatment adherence increased, saving many patient lives in China.

Physicians should also be aware that patients want to have autonomy with decisions and feel understood.7 Studies have shown that clinical processes are smoother when patients feel that they are actively communicating with their physician be-

cause it, again, fosters trust in the physician.3 Even the initial greeting of a patient with a warm smile or simple handshake is important as it puts the patient at ease.3 More than 85% of patients expect small communicative actions12 to feel that they are acknowledged as human beings and not an object of disease or illness. Though empathy and friendliness are not at the top of the list of qualities in a doctor, the patient wants the doctor to be at least attentive, truthful, and experienced when both parties communicate. Further-

more, over 90% of patients expect physicians to inform them of physical examination purposes, and they are to be done in a respectful manner,11 so physicians must explicitly explain their actions to foster a good physician-patient relationship. All of these actions collectively fall under effective communication, and with it, the results show a positive effect on the physician-patient relationship. Though communication is not a branch of medicine, it is an essential skill that every physician should know to give the best quality care.

1. Emanuel E. Four models of the physician-patient relationship. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association 1992;267(16):2221-2226.

2. Ha JF, Longnecker N. Doctor-patient communication: a review. Ochsner J 2010;10:38-43.

3. Huntington B, Kuhn N. Communication Gaffes: A Root Cause of Malpractice Claims. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 2003;16(2):157–61.

4. Stone M. What patients want from their doctors. BMJ 2003;326(7402):1294–

5. Linzer M, Bitton A, Tu S, Plews-Ogan M, Horowitz K, Schwartz M. The End of the 15–20 Minute Primary Care Visit. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2015;30(11):1584-1586.

6. Rabin R. 15-Minute Visits Take A Toll On The Doctor-Patient Relationship [Internet]. Kaiser Health News. 2014.

7. Coulter A. What do patients and the public want from primary care?. BMJ 2005;331(7526):1199-1201.

8. Schattner A, Rudin D, Jellin N. Good physicians from the perspective of their patients. BMC Health Services Research 2004;4(1).

9. Bensing J, Rimondini M, Visser A. What patients want. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 Mar;90(3):287-90.

10. Du L, Wu R, Chen X, Xu J, Ji H, Zhou L. Role of Treatment Adherence, Doctor-Patient Trust, and Communication in Predicting Treatment Effects Among Tuberculosis Patients: Difference Between Urban and Rural Areas. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2020 Nov 24;14:2327-2336.

11. Tran TQ, Dalen Jvan, Scherpbier A, Do Dvan, Wright EP. Nationwide survey of patients’ and doctors’ perceptions of what is needed in doctor - patient communication in a Southeast Asian context. 2020;

12. RM M, GSM W, MK P, JMH J. Patient’s Expectations during Doctor Patient Communication and Doctors Perception about Patient’s Expectations in a Tertiary Care Unit in Sri Lanka. 2015;7(6).

Death is absolute

How someone should die is subjective Physicians are the gatekeepers to death Ever human, their moral compasses create these boundaries

Some souls venture to the gates And the physician must leave them restless Or allow them to pass

In the absence of a universal manifest Each physician must choose that line Religion, superstition, morality, mere opinion Each must be willing to bear that decision.

I trust in my Catholic faith to uphold my line When my time for such a decision comes

BY MARLENA KUHNWhen I express a personal unwillingness towards administering a lethal injection I stay true to my faith

When I express my lack of discomfort with pulling the plug I stay true to the belief of a dignified death

For if I do not deny food and drink, nor actively push someone through the gates I cannot rob them of a natural death by withholding extraordinary measures

As a Catholic, I do not need to force a patient to live an unnatural life Yet I cannot directly deliver an unnatural death

Though a hazy line to some I find a comfort in centering my future stance around a spiritual authority

The necessity of this heavy choice Must become comfortable to aspiring physicians

Some will doubt, and some will judge But as long as one can find something to wholeheartedly believe in

The duty of a gatekeeper will be properly upheld as each see fit

Much of the material for the biotechnology industry comes from resource-rich developing countries. The fact that leading biotech businesses from developed countries could easily usurp these resources through financial coercion gives them comparative and absolute advantages in the industrial competition over underdeveloped countries. Academic capitalism and biocapitalism are thoroughly defined in the previously published Medical Dialogue Review (MDR) paper, “Global Neoliberal Agenda Fosters Biocapitalism/Academic Capitalism,” academic capitalism and biocapitalism were thoroughly defined.[1]

Academic capitalism, specifically biocapitalism, creates an unsustainable economic model of innovation. With the in-

troduction of patents on genetic materials achieved through bioengineering and the increasing consolidation of the biotechnology industry, firms must procure a source of new genetic materials to derive profitable products.

Government-granted monopoly is the most common approach firms take. The leading pharmaceuticals, for instance, monopolize legal patents to realize market monopoly to protect themselves from the unpredictability of open competition. Such a monopoly creates barriers to entry for anyone who wishes to enter the industry.

In many cases, the high entry bar is unfair for the developing institutions; (monopolies of) patents also challenge the health conditions in less developed

countries because many simply cannot afford medicines from the pharmaceutical giants. This paper will examine the work done by leading scholars regarding the economic consequences of biocapitalism and its societal influence on public health.

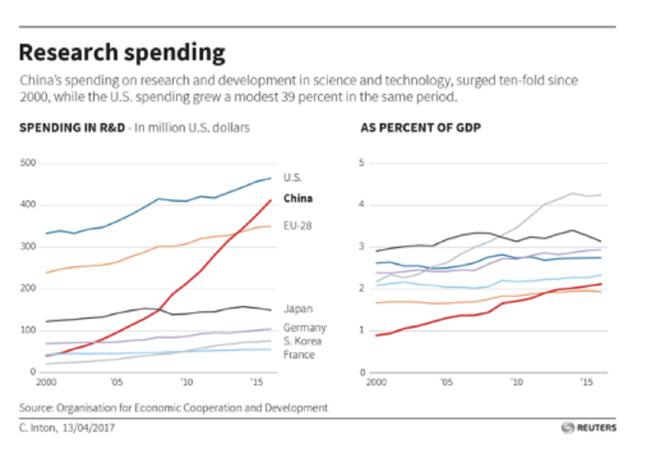

Biocapitalism investments are much more popular in developed countries than in developing countries. It is largely due to two reasons. First, there are different levels of interest and goals for Research & development (R&D) expenditure among developed and developing countries.

For instance, South Korea and Israel spend more than 4% of their gross domestic product (GDP) on research, while many Arab countries spend less than 1% (e.g. Saudi Arabia 0.25%), according to the 2019 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) report.

edge in developing countries and lead to a stagnation of innovation.

Biocapitalism also causes hardships for underdeveloped countries to meet their basic living necessities by restricting the exchange of certain inventions and products that cannot be commercially made, used, distributed, imported, or sold by others without developed countries’ consent. Developed countries, on the other hand, usually predominate the creation of patents and demand IPR laws to maintain the fairness of competition.

Secondly, developing and developed countries own different types of capital in the biotechnology industry. While most of the technological developments in the biotechnology industry are concentrated within the developed world, most of the biological resources that are used in this research are located in the developing world. Once the biomaterials (DNA, RNA, enzyme, etc.) are discovered in their raw form, they are collected and carried to the laboratories of the developed world where they are subjected to research for useful properties. If found, these properties form the basis of new patentable products and procedures.

Figure: OECD 2019, Gross domestic spending on R&D, and as a percentage of GDP R&D expenditure is necessary yet not indispensable for individual countries.

For underdeveloped countries that are still struggling to fulfill basic living necessities, the incentive for their R&D funding is low. The industry largely remains in the state of chasing the footsteps of global innovation dominators. Therefore, biocapitalism could present a barrier to knowl-

When pharmaceuticals or agricultural products do make it to market, companies often see a phenomenal return on their investment. Often, however, the community or country sourcing the knowledge or the natural resources is often left out of any benefit. This process constitutes what is called “biopiracy.”[3] Though some might argue that developing countries should ask for shares of profits, a more logical way to deal with biopiracy is to first decrease the unreasonably high price of the finished products in developing countries.

As the products become affordable in developing countries, they could then gradually enter the competitive market to

make a profit. Biopiracy is only one of the many examples of monopolistic behaviors of the developed world in exploiting the developing world. Although a perfect monopoly does not exist in the biotechnology industry, it is helpful to examine the basic elements of monopoly to understand the motives of biocapital investors.

The foundation of a monopoly is barriers to entry: a monopoly remains the only seller in its market because other firms cannot enter the market and compete with it. Barriers to entry, in turn, have three main sources:

• A key source is owned by a single firm

• The government gives a single firm the exclusive right to produce some good or service

• The costs of production make a single producer more efficient than a larger number of producers. In the case of the biotechnology industry, barriers to entry mainly come from government-granted privileges, which is a legal form of monopoly in which the government grants one individual or corporation the right to be the sole provider of a good or service.

Doing so often regulates the price that a monopoly-granted firm may charge its customers for its product or service. In some cases of government-granted monopolies, the government identifies itself as the sole provider of the good or service.

Existing opinions on government-granted monopolies through patents vary. Some scholars argue that without the guarantee of monopoly rents, new pharmaceuticals would not be brought

to market because the R&D cost of biopharmaceuticals are high and need to be compensated through government-granted monopoly licenses. Salaries, materials, supplies used, part of overhead costs, and the cost of developing quality control are all considered to be part of R&D expenditure.

According to a new study by a team including researchers from Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, “clinical trials that support FDA approvals of new drugs have a median cost of $19

million. The $19 million median figure represents less than one percent of the average total cost of developing a new drug, which in recent years has been estimated at between $2 to $3 billion”.[4]

Hopkins scholars’ justification for monopoly privilege is unfounded, however. Firstly, there are inflations in the R&D cost. How much of the cost is used effectively is questionable. According to a report from the Roosevelt Institute, the evidence fails to support the industry’s claim that high prices are necessary for increased investments in R&D.[5] Johnson & Johnson, the world’s largest drug corporation, spent more than twice as much

Though some might argue that developing countries should ask for shares of profits, a more logical way to deal with biopiracy is to first decrease the unreasonably high price of the finished products in developing countries.

on sales and marketing ($17.5 billion) as they did on R&D (8.2 billion), according to research firm GlobalData.[6]

Moreover, to the extent that the industry is investing in research, such spending tends to support the advancement of profitable drugs rather than investments in medicines considered to be less profitable.

According to a report by Felicia Wong, the CEO of the Roosevelt Institute, Pfizer had made $53 billion in revenue and over $11 billion in profits by the end of 2018, which made Pfizer one of the most profitable companies on Earth.[7]

On the other hand, scholars who argue against government-granted monopoly suggest that it is unfounded. Gilbert Berdine argues that “copying existing items and offering them at lower prices is a common means of competition. Copying is not stealing as long as the raw materials, labor, and the capital necessary for production belong to the producer.”[8] New technologies and international competitions have put much pressure on traditional patent and intellectual property rules, exemplified by the software, biotechnology, and semiconductor industries.

In response, Paul N. Doremus suggested a tendency to externalize or modify domestic intellectual property rights (IPR) regulation in the U.S. due to repercussions that have interrupted the equilibrium of international relationships: “the broad political stakes and serious economic consequences of IPR have exacerbated major cleavages in the world economy, cleavages which not only set rich countries against poor but also set rich countries against each other.”[9]

As mentioned earlier in Section 1, Pfizer raised prices on 41 of its prescription drugs in January despite its enormous profits and spent 180% of its net income in 2018 to pay shareholders in the form of dividends and buybacks.[7] In a way, government-granted monopolies protect their manipulative actions because there are no serious legal consequences for their price inflation. Besides, the same incentive for innovation can be achieved through subsidies.

Removing patent rights is certainly not optimal because it gives even less incentive for domestic innovation worldwide. Patent rights can only be a tool for the monopolizing force of the market when domestic industries cannot catch up. Thus, the solution to the government-granted monopolies dilemma should come from bridging the resource gap between developing and developed countries’ industries by creating cooperation platforms and regulating only unjustifiable monopolies in the biotechnology industry.

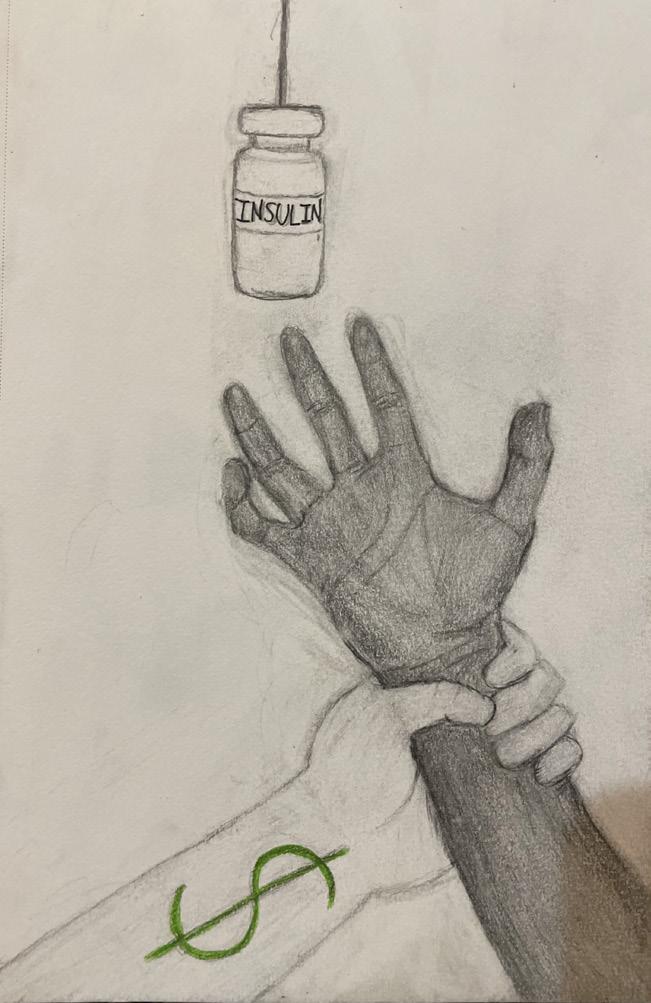

Besides economic reasons, biocapitalism undermines the demands for im-

Thus, a favorable solution to the conflict between medical IPR and public health quality is through the rule-making processes of International Health Organizations. The communities of users of medicine, especially from developing countries, ought to stay proactive.

proved access to affordable medicine, a basic human right, and enables beneficiaries to make a profit off the suffering of illness in regions with medical needs. Over 80 percent of Americans across the political spectrum believe that lowering drug costs should be a “top priority” for lawmakers, and believe prescription drug costs are “unreasonable.”[10]

In the words of Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), the pharmaceutical industry exists “to discover and develop medicines that enable patients to live longer, healthier[,] and more productive lives”. [11] However, a business model of profit and market share maximization is essentially incompatible with this stated goal. Thus, the practice of biocapitalism, which hinders the efficiency of public health, is unethical.

Nitsan Chorev, a professor at Brown University, disclosed a case study of medicine and related substances patent dispute between South Africa and the US, in which the US imposed economic sanctions on South Africa for abolishing patent rights for pharmaceuticals.[12]

With the patents, American pharmaceuticals were able to monopolize the market during the early research process and raise prices discretionarily. However, patients of HIV/AIDS in South Africa could not afford the skyrocketing bills.

Thus, civilian groups in South Africa such as Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) and the South African trade union COSATU reacted courageously.[12] They staged an all-night vigil and protest outside the court building and the U.S. embassy. A transnational network of activists organized demonstrations in thirty other cities worldwide; the transnational activist network swayed public opinion in developed countries and gained the support

of unlikely allies, including the European Union, the Dutch government, the World Bank, and WTO officials.[12] The prevailing opinion was that the urgency of the HIV/AIDS epidemic related directly to human lives could offset the established IPR rules.

South Africa has set a great example for the world. Thus, a favorable solution to the conflict between medical IPR and public

health quality is through the rule-making processes of International Health Organizations. The communities of users of medicine, especially from developing countries, ought to stay proactive. To borrow the words from Peter Drahos, “democratic bargaining is the key to socially productive intellectual property rights.”[13]

In critical conjunction with the COVID-19 pandemic, changes in IPR rules regarding biocapitalism are particularly important because it essentially af-

fects everybody in this world as we have seen in vaccine access and essential medical resources’ distribution. In short, the

unaddressed economic and social consequences of biocapitalism will be burdens to all humanity, if not already are.

1. Xue, Selina. “Global Neoliberal Agenda Fosters Biocapitalism/Academic Capitalism”. MDR Volume 15, Issue 2. Slaughter et al. defined “academic capitalism” as “institutional or professional market or market-like efforts to secure external money” by transforming traditional concepts of knowledge and intellectual property into capital.

2. OECD 2019, Gross domestic spending on R&D (indicator). doi: 10.1787/ d8b068b4-en.

3. Biopiracy is an unethical or unlawful appropriation or commercial exploitation of biological materials (such as medicinal plant extracts) that are native to a particular country or territory without providing fair financial compensation to the people or government of that country or territory.

4. Aspril, Joshua, and JH Health, “Cost Of Clinical Trials For New Drug FDA Approval Are Fraction Of Total Tab”. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School Of Public Health, 2019.

5. Katy Milani and Devin Duffy, Profit over Patent: How the Rules of our Economy encourage the Pharmaceutical industry’s Extractive Behavior, pp 2, February 2019.

6. Richard, Anderson. 2014. “Pharmaceutical industry gets high on fat profits.” BBC News. November 6, 2014.

7. Felicia,Wong. George,Goehl. 2019. “Pfizer Shareholder Meeting Offers Inside Look At The Pharma Industry - STAT”. STATNEWS.

8. Gilbert, Berdine. The Case Against Pharma Patent Monopolies | Gilbert Berdine. Mises Institute, 2019.

9. Doremus, Paul N. “The Externalization of Domestic Regulation: Intellectual Property Rights Reform in a Global Era.” Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 3, no. 2 (1996): 341-74.

10. Roubein, Rachel. 2019. “POLITICO-Harvard poll: New Congress Should Fight Hate Crimes, Tackle Drug Prices.” Politico, January 3, 2019; Kirzinger, Ashley, Bryan Wu, and Mollyann Brodie. 2018. “Kaiser Health Tracking Poll – March 2018: Views on Prescription Drug Pricing and Medicare-for-all Proposals.” Kaiser Family Foundation. March 23, 2018.

11. PhRMA 2018. “Who We Are.”

12. Chorev, Nitsan. “Changing Global Norms through Reactive Diffusion: The Case of Intellectual Property Protection of AIDS Drugs.” American Sociological Review 77, no. 5 (October 2012): 831–53.

13. Drahos, P. 2005. Intellectual property rights in the knowledge economy. In Handbook on the Knowledge Economy, ed. G. Hearn Rooney and A. Ninan. Cheltenham:Edward Elgar.

The New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation (HHC) is the largest public health system in the country, serving more than a million New Yorkers each year across more than seventy locations throughout the city (“About us”). These locations include large hospitals, longterm rehabilitative facilities, and Gotham Health centers, which provide community-based primary and preventative care.

HHC locations include 11 major hospitals: Elmhurst, Queens, Kings County, Coney Island, Woodhull, Metropolitan, Bellevue, Harlem, Jacobi, Lincoln, and North Central Bronx. Some of these hospitals are associated with academic medical centers; for example, Elmhurst is associated with the Mount Sinai medical system.

HHC serves as a safety net healthcare system; many of its most-frequent patrons do not have the means to access more expensive healthcare options. Many patients at HHC require the assistance of services such as Medicaid, Medicare, or HHC’s own health plan MetroPlus. The MetroPlus Health HHC also serves a large uninsured population. In fiscal year 2019, HHC served 374,998 uninsured patients, a large portion of the 1,081,156 total unique patients they served that year (Cheng and Francisco).

Being a public healthcare system comprised of safety net hospitals, HHC serves many patients who have difficulty afford-

ing healthcare and have limited access to primary or preventive care.

Often, these patients would seek care by heading to emergency rooms first, which makes them more susceptible to contracting diseases in healthcare facili-

In March and April of 2020, New York City was the epicenter of the coronavirus epidemic in the United States, and many of these patients were treated in HHC hospitals. Working-class New Yorkers were naturally more likely to get exposed to coronavirus; they are more likely to live in crowded areas, have underlying conditions, and have jobs that cannot be done from home.

ties and more likely to have harsher complications for their existing diseases, as they start treatment later in the course of a disease, when treatment is more difficult and expensive.

This approach to care hurts not only the finances of patients, but also the finances

of the healthcare systems in which they receive care, as these systems will often have difficulty receiving compensation and will have to use more resources when providing treatment. Often, programs like Medicaid contribute less for treatments and procedures than private health insurance companies do. This leads to HHC seeing losses in revenue, which also impacts its ability to obtain high-tech treatments and devices for its patients. HHC hospitals are heavily reliant on contributions from Medicaid because many its patients require such services.

Thus, the $400 million in cuts that were proposed in early 2020 by then-Governor Andrew Cuomo would have had severe consequences on the system. (Mahler). HHC had budgetary issues even preceding the pandemic, with expenses far outweighing revenue. In a report released on March 9, 2020, by the finance division by the Council of the City of New York, it was projected that HHC would have operating revenue of $7.7 billion but operating expenses of $9 billion in fiscal year 2020 without corrective action (Cheng and Francisco).

As these numbers were calculated and release prior to the outbreak of coronavirus in New York City and its heavy toll on HHC hospitals, it is reasonable to assume that actual operating losses in fiscal years 2020 and 2021 were greater than was predicted in these reports.

In March and April of 2020, New York City was the epicenter of the coronavirus epidemic in the United States, and many of these patients were treated in HHC hospitals. Working-class New Yorkers were naturally more likely to get exposed to coronavirus; they are more likely to live in crowded areas, have underlying conditions, and have jobs that cannot be done from home.

HHC’s Elmhurst Hospital in Queens was hit the hardest. Queens was hit the hardest of the five boroughs: it accounted for 32% of the city’s confirmed cases by April 2020, which was particularly unfortunate as it only has three major medical centers (Rothfeld et al). Elmhurst had to resort to building new intensive care unit rooms, sending patients to other HHC hospitals, and renting refrigerated trucks, as its normal intensive care unit and morgue quickly became overwhelmed (Rothfeld et al).

HHC hospitals were hit harder than the larger private hospitals in the city. Hospitals that are part of large private medical systems were more likely to have access to advanced treatments like E.C.M.O, a heart-lung bypass, and newer anti-viral drugs, like remdesivir (Rosenthal et al). Ironically, these hospitals, which are primarily based in Manhattan, were less likely to be overwhelmed.

Manhattan had a lower prevalence of cases (16 for every 1000 residents in Manhattan compared to 28 for every 1000 residents in Queens) and has a greater proportion of hospital beds (5 for every 1000 residents in Manhattan compared to 1.8 for every 1000 in Queens) compared to other boroughs (Rosenthal et al).

Since the spring of 2020, the coronavirus epidemic has somewhat subsided In New York City. Although there have been

some surges, such as the one due to the Omicron variant in late 2021, HHC hospitals have not been as overwhelmed as they once were.

Healthcare providers had learned strategies to ensure greater survival rates, such as avoiding intubating patients and instead relying on less-invasive ways of oxygenating patients (Otterman and Goldstein). This has helped hospitals handle the strain experienced during the omicron-variant peak without being as overwhelmed as they once were.

1. About NYC Health + Hospitals. NYC Health & Hospitals. https://www.nychealthandhospitals.org/about-nyc-health-hospitals/. Accessed April 2022.

2. Cheng J, Francisco CR. Report of the Finance Division on the Fiscal 2021 Preliminary Plan, Fiscal 2021 Preliminary Capital Budget, Fiscal 2021 Preliminary Capital Commitment Plan, and the Fiscal 2020 Preliminary Mayor’s Management Report for New York City Health + Hospitals. The Council of the City of New York. https://council.nyc.gov/budget/wp-content/uploads/sites/54/2022/04/Fiscal-2023-Preliminary-Budget-Response-.pdf. Published March 9, 2020.

3. Mahler J. The Epicenter A week inside New York’s public hospitals. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/04/15/magazine/ new-york-hospitals.html.

4. Rothfeld M, Sengupta S, Goldstein J, Rosenthal BM. 13 Deaths in a Day: An ‘Apocalyptic’ Coronavirus Surge at an N.Y.C. Hospital. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/25/nyregion/nyc-coronavirus-hospitals.html. Published April 14, 2020.

5. Rosenthal BM, Goldstein J, Otterman S, Fink S. Why Surviving the Virus Might Come Down to Which Hospital Admits You. The New York Times. https:// www.nytimes.com/2020/07/01/nyregion/Coronavirus-hospitals.html. Published September 22, 2021.

6. Otterman S, Goldstein J. How New York City’s Hospitals Withstood the Omicron Surge. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/02/05/nyregion/ omicron-nyc-hospitals.html. Published February 10, 2022.

7. Dwyer J. One Hospital Was Besieged by the Virus. Nearby Was ‘Plenty of Space.’ The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/14/nyregion/coronavirus-ny-hospitals.html. Published July 1, 2020.

Grief, just as death, is a universal human experience. For those that live long enough, it seems inevitable that someone they love will shatter their hearts with untimely or even expected passing. As such, grief, in our own present experience and through study of our predecessors, appears to be a most natural consequence

this paper, I will examine an argument for the use of antidepressants as treatment for ordinary grief on the basis of the similarity between depression and grief as well as mercy for the grieving. After such an explanation, I will offer an objection that relies on a contextual view of depression and defines grief by the procedural benefit it may offer a person, ultimately concluding that antidepressants should not be used in the treatment of ordinary grief.

of such an unmendable separation of two people, even to such a degree that it may seem intuitive to question a person’s true affection for the dead if they do not grieve them. However, what if there were a “cure for grief?” What if the treatment used to help people who suffer from depression get better could be used to help people pass through their grief more quickly? In