THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO

BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION

Unscrambling burnout

Taking an organizational approach to improve the well-being of physicians and scientists

FALL 2022

Kenneth S. Polonsky, MD

Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs The University

Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs The University

Dear Colleagues,

Earlier this year, I wrote to you about my plans to step down as Dean of the Biological Sciences Division and the Pritzker School of Medicine and Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs for the University of Chicago. As my term concludes, I am pleased to welcome Mark Anderson, MD, PhD, who succeeded me in this role effective October 1, 2022.

Dr. Anderson is a respected scholar, physician and medical leader, who joins us from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he was director of the Department of Medicine, the William Osler Professor of Medicine and physician-in-chief of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Before moving to Johns Hopkins in 2014, he led the Cardiovascular Research Center and the Department of Medicine at the University of Iowa and served on the medical faculty at Vanderbilt University, where he directed educational and clinical programs. His scholarly work on the mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure has also earned him international recognition.

This background makes him extremely well-qualified for this new role, as he leads the medical and biological research, education, care delivery and community engagement enterprise for the University of Chicago Medicine, the Biological Sciences Division and the Pritzker School of Medicine.

The breadth and scope of this work is particularly evident in this issue, which features elements of our entire mission.

The cover story, by Emily Ayshford, addresses the challenge of workforce burnout among physicians, scientists and healthcare workers that came to a head during the COVID-19 pandemic, and the grassroots efforts at our institution and others to find solutions that address it. Another piece extends beyond our campus to work that engages the global community, detailing the efforts of Amy Lehman, AB’96, MD’05, MBA’05, to build health systems in East Africa.

This issue also features a profile of Shirlene Obuobi, MD’18, the first Black female cardiology fellow at UChicago Medicine in more than a decade, who is also a talented comics artist and author. Obuobi and Bryan Smith, MD’10, have worked together on programs to mentor students from underrepresented minority backgrounds who are interested in medical careers.

In addition to our efforts to better the human condition, the Biological Sciences Division is also home to a vibrant community of investigators who seek to understand the very essence of life, death and our earliest beginnings. This issue includes two such stories about the work of Clifton Ragsdale, PhD, and two of his trainees at the Marine Biological Laboratory deciphering the genomes of cephalopods and deconstructing the sequence of hormone signaling that leads to the death of mother octopuses after they lay their eggs.

These are exciting times for the Biological Sciences Division and for UChicago Medicine. I look forward to the future as a faculty member and am confident that under Dr. Anderson’s leadership we will continue to enjoy exceptional accomplishments and exciting progress in all of our missions.

Dean’s Letter

As my term concludes, I am pleased to welcome Mark Anderson, MD, PhD, to lead the medical and biological research, education, care delivery and community engagement enterprise for the University of Chicago Medicine, the Biological Sciences Division and the Pritzker School of Medicine.

The Richard T. Crane Distinguished Service Professor Dean of the Biological Sciences Division and the Pritzker School of Medicine

of Chicago

Fall 2022 Volume 75, No. 2

A publication of the University of Chicago Medicine and Biological Sciences Division. Medicine on the Midway is published for friends, alumni and faculty of the University of Chicago Medicine, Biological Sciences Division and the Pritzker School of Medicine.

Email us at momedit@uchospitals.edu

Write us at Editor, Medicine on the Midway

The University of Chicago Medicine 950 E. 61st St., WSSC 322 Chicago, IL 60637

The University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine and Biological Sciences

Executive Leadership

Kenneth S. Polonsky, MD, Richard T. Crane Distinguished Service Professor, Dean of the University of Chicago Biological Sciences Division and the Pritzker School of Medicine, and Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs for the University of Chicago

Mark E. Anderson, MD, PhD, Paul and Allene Russell Professor, incoming Dean of the Biological Sciences Division and the Pritzker School of Medicine, and Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs

T. Conrad Gilliam, PhD, Marjorie I. and Bernard A. Mitchell Distinguished Service Professor, Dean for Basic Science, Biological Sciences Division

Thomas E. Jackiewicz, President of the University of Chicago Medical Center

Vineet Arora, MD, AM’03, Dean for Medical Education, Pritzker School of Medicine

Editorial Committee

Chair Jeanne Farnan, AB’98, MD’02, MHPE

Jennifer “Piper” Below, PhD’11

Dana Lindsay, MD’92

Rob Mitchum, PhD’07

Loren Schechter, MD’94

Coleman Seskind, AB’55, SB’56, MD’59, SM’59 (Lifetime Member)

Carol Westbrook, AB’72, PhD’77, MD’78

Student Representatives

Peishu Li, SM’22 (BSD)

Tony Liu (Pritzker)

University of Chicago Medicine

Marketing and Communications

Anna Madrzyk, Editor

Editorial Contributors

Emily Ayshford

Jamie Bartosch

Kate Dohner

Diane Dungey

Diana Kenney, Marine Biological Laboratory

Tyler Lockman

Photo Contributors

Mark Black

GradImages

Rob Hart

Tom Kleindinst

Robert Kozloff

Jean Lachat

Lake Tanganyika

Floating Health

Clinic

Design

Wilkinson Design

Beyond yoga: Taking an organizational approach to battling burnout 14

The COVID-19 pandemic unleashed a perfect storm of stressors on clinicians and scientists, but many of the factors leading to burnout are long-standing. Across the country, institutions are hearing the call for systemic changes to improve efficiency of practice, create a culture of wellness and foster personal resilience.

Alumni profile

Howard Liang, PhD’92, MBA’01, took an unconventional career path from scientist to Wall Street analyst to CFO.

Triple threat 22

It’s been a whirlwind year for Shirlene Obuobi, MD’18 cardiology fellow, artist and author of the buzzy novel On Rotation

Ellen McGrew

Devon McPhee

Angela Wells

O’Connor

Sarah Richards

Jack Wang

Lorna Wong

Matt Wood

Rose Lincoln/ Harvard University

Marine Biological Laboratory

Anne Ryan

Joe Sterbenc

Nancy Wong

John Zich

A floating health clinic 8

For more than a decade, Amy Lehman, AB’96, MD’05, MBA’05, has been bringing healthcare to Africa’s Lake Tanganyika, an area that has seen “an epic amount of suffering” but gets little attention.

Reunion returns in person

Find

IN THIS ISSUE

COVER STORY

5

FEATURES

32

your classmates or yourself in our six pages

photos and stories. 32 22 30 14

of

Renowned cardiac expert and medical leader joins BSD, UChicago Medicine

Mark Anderson, MD, PhD, a renowned scholar, physician and caregiver, will lead the University of Chicago’s field-defining work in medicine and biological sciences as the new Executive Vice President for Medical Affairs, Dean of the Biological Sciences Division and Dean of the Pritzker School of Medicine. His appointment was effective October 1.

He succeeds Kenneth S. Polonsky, MD, who will serve as Senior Advisor to the President and remain a tenured faculty member at the University.

Anderson comes to the leadership of the University of Chicago Medicine from the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, where he served as director of the Department of Medicine, the William Osler Professor of Medicine and physician-in-chief of The Johns Hopkins Hospital. Before moving to Johns Hopkins in 2014, he led the Cardiovascular Research Center and the Department of Medicine at the University of Iowa and served on the medical faculty at Vanderbilt University, where he directed educational and clinical programs.

“Mark is an extraordinarily talented and globally respected medical leader who is committed to an ambitious agenda of basic, translational and clinical research, while preparing the next generation of scholars, clinicians and leaders in biological sciences and academic medicine,” said University

of Chicago President Paul Alivisatos. “Mark is in a strong position to lead growth of our clinical enterprise and will have a significant focus on the expansion of the University of Chicago Medicine’s regional health system.”

Anderson will lead the medical and biological research, education, care delivery and community engagement enterprise for UChicago Medicine, the BSD and Pritzker.

Anderson earned a PhD in physiology and an MD from the University of Minnesota. He completed his internal medicine residency and fellowships in cardiology and clinical cardiac electrophysiology at Stanford University.

“I am thrilled and humbled to join the University of Chicago community, and look forward to the opportunity to work across the University and the South Side to promote biomedical discovery, education and health.”

Mark Anderson, MD, PhD

His scholarly work, commitment to education and medical leadership have earned international recognition, and he is a leading expert on the mechanisms of cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure. His research is focused on the role of the calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in heart failure and cardiac arrhythmias, which are a common cause of sudden cardiac death. He has published more than 160 peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters and book reviews. In 2017, Anderson was elected to the National Academy of Medicine.

In his leadership roles at Johns Hopkins, Anderson oversaw more than 700 full-time faculty members and clinicians across 18 academic divisions, nearly 3,000 staff members and trainees, 300,000 clinic visits, and an annual research portfolio of more than $200 million in the last year. He also led the Department of Medicine’s efforts in securing philanthropy, raising approximately $20 million to $40 million annually.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION 2 Midway News

LEADERSHIP

Mark Anderson, MD, PhD

Alumnus’ gift establishes new annual lecture featuring prominent scientists

Nobel Prize-winning biochemist Jack Szostak, PhD, was the inaugural speaker for the Coleman R. Seskind, MD, Lecture in the Biological Sciences in October.

The new annual lecture features a visiting lecturer working in any field represented in the Biological Sciences Division (BSD) who is a Nobel laureate, Lasker Award winner or other prominent scientist and who will engage with University of Chicago faculty and students.

Szostak joined the faculty this fall as University Professor in the Department of Chemistry and the College. A pioneering scholar of genetics who examines the biochemical origins of life, he shared the Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine in 2009 for the discovery of how chromosomes are protected by telomeres and the enzyme telomerase. He leads a new interdisciplinary program at the University called the Origins of Life Initiative, which seeks to understand the earliest processes governing the origin of life on Earth and elsewhere in the universe.

University Professors are among those recruited at a senior level from outside the University and are selected for internationally recognized eminence in their fields, as well as for their potential for high impact across the University. Szostak is the 24th person to hold a University Professorship and the 11th active faculty member holding that title.

The lectureship was established by a generous gift from Coleman R. Seskind, AB’55, SB’56, MD’59, SM’59, a retired private practice physician who previously worked in the Department of Pathology.

GRADUATE EDUCATION

New master’s degree program for those seeking biomedical careers

The University of Chicago is launching a new one-year Master of Science Degree in Biomedical Sciences (BMS) program in Autumn Quarter 2023. Applications opened in September 2022 and will be accepted through March 15, 2023.

The one-year degree, offered in partnership with the Pritzker School of Medicine, will enhance

Szostak previously served as a professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Harvard University, a professor in the Department of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, the Alexander Rich Distinguished Investigator at Massachusetts General Hospital, and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator.

Seskind has dedicated his time and expertise to the University of Chicago Medical & Biological Sciences Alumni

Association and the University of Chicago Medicine in numerous ways, including as a former president and now life member of the Alumni Council, a life member of the Division of the Biological Sciences and the Pritzker School of Medicine Council, a long-standing leader and chair of the 1959 medical school class, and three decades worth of volunteerism on the Editorial Committee of Medicine on the Midway magazine. A generous philanthropic supporter for over 50 years, Seskind received the University of Chicago Alumni Service Award in 2010.

The stewardship of the Seskind Lecture is guided by a committee of faculty members and graduate students, who will prioritize candidates nominated by the BSD community.

training for those seeking biomedical scientific careers and enable existing professionals from any career track to grow their biomedical expertise. The program’s mission, unlike a traditional postbaccalaureate program, is to create opportunities and catapult students toward a broad array of careers in biomedicine or other fields that rely on biomedical expertise.

Taught by faculty experts across the Biological Sciences Division, including the Department of Medicine and the Institute for Translational

Medicine, the program’s core curriculum focuses on applications and innovations in clinical care and medical treatment, statistics, bioethics and the American healthcare system. Students can specialize and complete a culminating capstone project in one of three areas of concentration: Science Communication, Biomedical Data Science or Health Systems Science.

To learn more, visit biomedicalsciences.bsd.uchicago.edu

3 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

SESKIND LECTURE

Coleman R. Seskind, AB’55, SB’56, MD’59, SM’59

Jack Szostak, PhD

PHOTO BY ROBERT KOZLOFF

PHOTO BY ROSE LINCOLN COURTESY OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY

How do you teach about advancing health equity? Improvise!

Marshall Chin, MD, MPH, learned more than storytelling and comedy techniques when he enrolled in a local improv class. He also discovered an innovative way to teach medical students at the Pritzker School of Medicine about advancing health equity.

“As I got more involved in improv, I realized that the emotional intelligence and listening skills we were learning could be a potentially very powerful way of teaching about equity,” said Chin, Richard Parrillo Family Distinguished Service Professor of Healthcare Ethics in the Department of Medicine.

Chin gathered a 13-person team of physicians and scientists with skills in medical training, health equity, the arts

and science communications, along with members of the entertainment industry and a program administrator, to design and implement workshops. The group represented a diverse set of perspectives, experiences and cultural backgrounds.

The team developed four 90-minute virtual programs that used multiple forms of performance and art to encourage students to explore ways to advance health equity. The team launched a pilot program in 2020 as part of Pritzker’s health equity requirement for first-year students. Learnings from the course were published in an invited commentary in the August issue of Academic Medicine

The pilot program has also garnered national attention. Members of the research team have given presentations

about it at both a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine event and a U.S. Department of Agriculture event. Devon

Midway News www Located within The Study at University of Chicago hotel, Truth Be Told is a tavern-styled restaurant inspired by the traditions of a British gastropub www.truthbetoldtavern.com | 872.315.1319 | truthbetoldtavern MEDICAL EDUCATION

PHOTO BY NANCY WONG

Marshall Chin, MD, MPH, left, and Vineet Arora, MD, AM’03, Dean for Medical Education at Pritzker, perform with the improv troupe The Excited State at The Revival theater in Hyde Park.

Watch a video abstract of the Academic Medicine paper: vimeo.com/748783311

McPhee

Targeting disease with gene writing

Howard Liang’s unconventional — but strategic — career path from scientist to Wall Street analyst to CFO

BY SARAH RICHARDS

Howard Liang, PhD’92, MBA’01, smiles when he talks about picking out the office space and used furnishings for a biotech company’s nascent bureau in the Boston area. It was 2015, and he’d just joined BeiGene, a firm that develops and manufactures cancer therapies. At the time, the company had a staff of under 200, all based in China.

“I was the first U.S. employee,” said Liang, who joined BeiGene as Chief Financial Officer and Chief Strategy Officer. “My cellphone was the phone number that we used to register the company.”

Today, BeiGene has more than 8,000 employees around the world and is best known for a portfolio of cancer therapies, including Brukinsa, a medicine for several blood cancers approved in 50 countries.

During Liang’s tenure, BeiGene set records in the largest primary equity financings for a biotech company. It is the first healthcare company to be listed on three stock exchanges (New York, Hong Kong and Shanghai).

It would be easy to be swayed by Liang’s down-to-earth manner and attribute his accomplishments to serendipity. That, however, would bely the industriousness and confidence that have propelled him through different professions, from scientist to Wall Street analyst to biotech CFO.

Liang’s first trip to America was in 1986, when he arrived to study at the University of Chicago. He had a chemistry degree from a top Chinese university, $50 in his pocket and two bulging suitcases. He

lived in International House and spent roughly five years studying biochemistry and molecular biology. That time was vital to building a methodical thought process, he said.

“I think a critical skill that was part of training at the University of Chicago was learning to be analytical to be able to put pieces of information together, synthesize it and come to a conclusion.”

After graduating with a PhD, Liang joined Abbott Laboratories as a scientist and worked on structurebased drug design. He published numerous studies in journals like Nature and Science, including research on the three-dimensional structure of the Bcl-2 family of proteins involved in programmed cell death. That research formed the basis of drug discovery work at Abbott that led to the creation of an approved, targeted blood cancer therapy called Venclexta.

But Liang has always enjoyed new challenges. During his time at Abbott, he earned his MBA from the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. Then, at 36, he decided to switch jobs to work as a pharmaceutical equity research analyst.

“It may sound like a really strange move, but it’s actually a pretty good fit in terms of the required analytical skills,” explained Liang, who lives in Boston. “You need to learn a lot about new companies, new scientific and clinical progress, and have that ability to put together information in a manner very similar as in science.”

His work on Wall Street earned him several recognitions, including The Wall Street Journal’s “Best on the Street” for his 2008 biotechnology stock picks and his 2010 biotechnology and pharmaceutical stock picks.

Liang is now President and Chief Financial Officer of Tessera Therapeutics, a gene editing company pioneering techniques to substitute, add and delete DNA to cure disease. He’s hopeful these technologies will have broad applications for health, from genetic diseases to cancer and other serious, prevalent conditions.

“Being a scientist by training, I’m interested in new developments, new areas of breakthrough,” Liang said. “Genetic medicine is a dramatically different way of treating disease, by correcting the root cause, and I am excited to be part of the endeavor.”

5 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway ALUMNI PROFILE

PHOTOS COURTESY OF HOWARD LIANG

Howard Liang, PhD’92, MBA’01, in Shanghai for BeiGene’s third IPO.

Liang started his career as a scientist at Abbott Laboratories.

Promoting diversity in orthopaedic surgery

BY KATE DOHNER

Although more than half of medical students today are women, they make up only 6.5% of orthopaedic surgeons, according to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Less than 2% of those practicing are Black, just 2.2% are Hispanic, and 0.4% are Native American.

The Simon Diversity Scholar Fund, established and endowed by Barbara and Michael Simon, MD, Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine at the University of Chicago, aims to change that. By supporting generations of highly engaged faculty who become Simon Diversity Scholars, the couple’s gift will establish a legacy of leadership in fostering diversity and inclusion in the field of orthopaedic surgery.

Each scholar will serve a three-year term dedicated to activities that help maintain and build diversity in the field. The scholars will develop as mentors and patient advocates, while also encouraging students to pursue orthopaedic surgery.

“Exposing a diverse group of high school, college and medical students to orthopaedic

Conti Mica is also arranging forums for students to engage with female orthopaedic surgeons across the country to learn about topics like work-life balance and navigating residency programs. As the inaugural scholar, Conti Mica will also lend her perspective to faculty search committees and diversity and inclusion committees within her department and beyond.

The Simons, who lived in Hyde Park for 22 years and raised their three daughters there, sought to not only diversify the field but also help patients in their community.

“The faculty and trainees should mirror the patients we serve,” Michael Simon said. “We hope our gift will help the department to recruit and retain more diverse faculty, so that we can better serve our patients.”

To this end, Conti Mica seeks to conduct research related to health disparities that affect the patients she sees. Though less widely publicized than disparities in other areas like maternal mortality, heart disease, and cancer, orthopaedic surgery also has a history of disparities.

“Some groups may not even be getting to surgery as much as others because of implicit biases,” said Douglas Dirschl, MD, Lowell T. Coggeshall Professor and Chair of the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine. For example, studies show patients of color are less likely to receive knee and hip replacements or care for hip fractures than white patients.

“It’s not enough for us to appreciate diversity and treat each patient fairly,” Dirschl said. “We need to behave in ways that are anti-racist and bring that into our daily patient encounters.”

The Simons are passionate about making an impact.

surgery early is key,” said Megan Conti Mica, MD, Associate Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine and the inaugural Simon Diversity Scholar. “When I meet with students, I share that I am an orthopaedic surgeon, but also a wife and mother with hobbies outside of medicine. I want to show them that they can still be an orthopaedic surgeon, even if they don’t fit the stereotypical mold.”

“Our hope is that, through this gift, we can make a difference on the South Side of Chicago through the important work being led at UChicago Medicine,” Michael Simon said.

Their gift also has the potential to touch lives across the country. “As each scholar gains expertise and knowledge in diversity and inclusion, they will begin to be included in committees and conversations beyond UChicago Medicine, where they can weigh in on these issues and affect change on a national stage,” Dirschl said.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION 6 Midway News PHILANTHROPY

Three generations of the Simon family. From left, the adults are Dyan Simon, LAB’88, MD’97; Renee Aronsohn, LAB’91, MD’03; Andrew Aronsohn, MD; David Kalt; Michael Simon, MD; Eddie Talerman, LAB’88; Susan Kalt, LAB’86, MD’96; and Barbara Simon.

Orthopaedic surgeon Megan Conti Mica, MD, is the inaugural Simon Diversity Scholar.

PHOTO BY JEAN LACHAT

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE SIMON FAMILY

Inspiring tomorrow’s leaders in cancer research

BY KATE DOHNER

An $11.4 million gift from anonymous donors will establish the Elwood V. Jensen Scholars Program in the Section of Hematology/Oncology at the University of Chicago Medicine. Designed to grow the next generation of leaders in oncology research, the program offers exceptional trainees sufficient resources and time to devote to rigorous research that informs innovations in cancer prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

The donors were motivated by the impact UChicago Medicine has had in advancing discovery and treatment of cancer, naming the program after the late Elwood V. Jensen, PhD, a professor emeritus at the University of Chicago. Jensen received the Lasker Award in 2004 for his work establishing the role

Embracing unconventional approaches

“Elwood V. Jensen’s spirit of scientific curiosity and willingness to embrace alternative approaches led to the development of new treatments that have since helped millions,” said Sonali M. Smith, MD, Elwood V. Jensen Professor of Medicine and Chief of the Section of Hematology/Oncology.

Like Jensen, Howard takes an out-of-thebox approach to his study of breast cancer, using multiple streams of data, including artificial intelligence and clinical information, to make clinically relevant predictions. Through this work, Howard seeks to identify which patients will respond well to chemotherapy, while also better predicting which patients’ disease is likely to recur.

“We use artificial intelligence to look at factors that a pathologist may not be able to see and that aren’t necessarily intuitive,” Howard said. “By combining information across different areas, like genetics and pathology, we’ve been able to outperform other models and more accurately predict risk of recurrence.”

Using this model, Howard hopes to decrease delays in treatment and reduce the cost of care, while also providing a tool that can be used anywhere. “I would like to evaluate these approaches in low-resource settings to impact the health of women with breast cancer worldwide,” he said.

whether cancer will recur.

promising young physicians to support their career development and encourage quality research.

Building and sustaining a strong team

The Elwood V. Jensen Scholars Program bolsters the mission of UChicago Medicine’s planned new cancer center, which will be Chicago’s first freestanding clinical cancer center. The endowed fund will support generations of promising young physician-scientists.

of hormones in cancer and pioneering chemotherapy, helping to radically change the way doctors treat the disease.

The inaugural Elwood V. Jensen Scholar, Fred Howard, MD, recently completed his third year as a medical oncology fellow at UChicago Medicine.

With funding as the inaugural Elwood V. Jensen Scholar, Howard seeks to transition to more independent research, eventually building his own lab and acquiring additional resources to speed his work.

In May 2022, Howard received a Young Investigator Award from the American Society of Clinical Oncology, bestowed on

“We cannot create a world-class facility that reimagines cancer care without an outstanding team of expert physicianscientists,” said Kunle Odunsi, MD, PhD, Director of the University of Chicago Medicine Comprehensive Cancer Center. “Thanks to this generous gift, we will be able to empower the next generation of cancer researchers who will be trained by our exceptional faculty to push the boundaries of what is possible.”

7 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

TODAY | Fred Howard, MD, inaugural Elwood V. Jensen Scholar, uses artificial intelligence and other data to help identify which breast cancer patients will respond well to chemotherapy and

PHOTO BY JEAN LACHAT

YESTERDAY | Elwood V. Jensen, PhD, conducted groundbreaking research that led to estrogen receptor-based therapies for breast cancer.

Taking it to Lake Tanganyika

devotes her career to building health systems in East Africa

8

PHOTO BY MARK BLACK

“The idea was to always have a map of the place with me.”

Amy Lehman, AB’96,

MD’05, MBA’05

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION

Amy Lehman, AB’96, MD’05, MBA’05,

BY DIANE DUNGEY

Amy Lehman grew up along Evanston’s Lake Michigan shore, but her life is defined by another great lake and the people around it.

Lake Tanganyika, vast and deep, is the setting for her work to deliver basic healthcare to a population beset by war, political upheaval, climate emergencies and poverty.

Lehman, AB’96, MD’05, MBA’05, founded the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic in 2008, not long after a storm shut down an airstrip and marooned her in the area, giving her time to travel along the lakeshore and deepen her longheld interest in East Africa.

She is partnering with the Rustandy Center for Social Sector Innovation at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business on her latest project, to test a new mosquito repellent. Her aim is to interrupt rising malaria transmission in an area with high rates of infections and deaths from the disease and where insecticide-treated bed nets, she said, are ineffective and even harmful.

Lehman focuses on fishing villages in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on

The problem with bed nets

During more than a decade working along Lake Tanganyika, Lehman, 49, has learned some disconcerting truths.

For instance: Suffering and deaths can be rising even as nations and aid organizations report progress against disease. The true picture is hidden by the extreme difficulty of collecting data in remote areas, and a crisis can go unrecognized and unaddressed.

“How is it that we’re making the decisions in Geneva and London, in New York and Washington, D.C., or even in the capitals of these countries, when we haven’t even characterized the problems accurately?” Lehman asks.

the west coast of Lake Tanganyika, which is 410 miles long and approaches a mile in depth. Burundi, Tanzania and Zambia also border the lake.

“It’s a part of the world that has had an epic amount of suffering and that gets very little attention,” Lehman said.

Another reality: Silver-bullet solutions, like well-funded and popular campaigns to deliver insecticide-treated bed nets, are credited with cutting malaria transmission in sub-Saharan Africa, but they don’t work everywhere. Around Lake Tanganyika, the nets invariably are used for fishing, where they cause environmental harm while failing to protect people, Lehman said.

Aside from dispersing insecticide into the water, the fine-gauge bed nets trap small, recently hatched fish, preventing them from growing and reproducing in a way that sustains local fish populations.

9 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

PHOTO BY MARK BLACK

★

PHOTO COURTESY OF THE LTFHC

Children gather around fishing boats in Sebele, north of the Ubwari Peninsula in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

LAKE TANGANYIKA

Longer and deeper than Lake Michigan

LONGER AND FAR DEEPER

THAN LAKE MICHIGAN, Lake Tanganyika lies within the East African Rift Valley.

Most of Lake Tanganyika lies in the Democratic Republic of the Congo on the west and Tanzania on the east, with portions in Burundi and Zambia.

At 410 miles, it is the longest freshwater lake in the world, compared to Lake Michigan’s 307 miles. Lake Tanganyika is 4,710 feet deep, second only to Russia’s Lake Baikal and far exceeding Lake Michigan’s 925 feet.

The lake contains one fifth of the world’s freshwater, which supports the livelihoods of millions of people.

People living around the 1,100mile shoreline use the lake for water, for transportation and for fishing. Rising lake levels threaten some of the 10 million or so people living in the Lake Tanganyika basin, some of whom were previously displaced by disasters and violence.

DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO

Lake Tanganyika’s beaches and coastal plains rise to steep mountains, such as the Mahale Mountains National Park in Tanzania, where chimpanzees flourish. The Kalambo Falls are near the southeast end of the lake.

There are hippos, crocodiles and hundreds of types of cichlids, tiny colorful fish that are losing ground in the wild because so many are collected for use in aquariums.

Sources: National Science Foundation, African Center for Aquatic Research and Education, The Guardian, U.S. State Department.

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION 10

Diane Dungey

TANZANIA

BURUNDI

ZAMBIA

“You know the marketing material, ‘Spend $10 on a bed net and save a family’s life,’ and everyone looks so happy under their bed net in their bed. But in a lot of really rural environments you have very small structures that house a lot of people and don’t have bedrooms and don’t have beds,” she said.

Meanwhile, after a sharp decline, malaria deaths are rising in the World Health Organization’s Africa Region. The disease remains the number one cause of death around Lake Tanganyika, Lehman said.

A house-to-house survey by the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic found

‘Easier to go into space’ Lehman’s 10-person team on Lake Tanganyika recently completed a weekslong trip to update data from villages along the Ubwari Peninsula in South Kivu Province, an area torn by violence in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Because of the difficulty of traveling and camping, “we go there with many goals,” said Aris Macos, manager of field operations at Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic. Those include going house to house gathering reports of cases of malaria and other illnesses, setting light traps for mosquito surveillance, and

an average of 3.8 cases of malaria per household occurring over a three-month period in 2016, with children particularly hard hit. Across the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the disease accounts for 19% of deaths of children under age 5, reports the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative.

“Are the prevention strategies working in the areas that have the highest caseloads and the highest mortality?” Lehman asked.

Such questioning has made her the “bad girl” in the aid and development space, said Lehman, who has no problem wearing that mantle.

“We need to do better. We need to be accountable to our own intervention strategies. We need to be data-driven. We need to listen to what communities are saying their problems are and where they think interventions would be most impactful.”

studying fishing practices with the help of a fisheries biologist.

“You need to go talk physically with everyone,” Macos said. “It’s easier to go into space than to go to small villages inside of Congo.”

The meticulous work is aimed at securing funding to test a spatial mosquito repellent in villages on the Lake Tanganyika shore. The controlled-release repellent is on plastic or fiberglass sheets, each about the size of a sheet of paper, that are hung in homes.

But the sheets must be replaced every month or so, compared to bed nets, which last years.

That’s why Lehman teamed up with Bariş Ata, PhD, Sigmund E. Edelstone Distinguished Service Professor of Operations Management in Chicago Booth, and Booth graduate student John

Floating Health Clinic staff, local nurses and others, above left. The team, including Amy Lehman, MD, arrives after traveling from Kigoma to Kazimia.

11 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE LTFHC

Aris Macos is field operations manager of the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic.

FACING PAGE

Lake Tanganyika

PHOTO BY PLANETOBSERVER / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Montgomery. They are developing a model to manage inventory and delivery of the product that will work across 41 villages totaling about 200,000 people.

They hope to show that reduction in disease per dollar spent is competitive with bed nets, Ata said.

“When one solution doesn’t work perfectly, you may need to look for alternatives that may be more expensive, but will potentially work better,” Ata said.

Secured sheds can store supplies of the repellent sheets in villages around Lake

focused her attention on Tanzania, where he was born. Mziray died in 2011, and a tribute to him is on the website of the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic, at floatingclinic.org.

During that initial trip, interrupted by a typhoon, Lehman’s travel in the area with her school-age son Max, now 28, introduced her to people who often were refugees, lacking food and shelter, and suffering from illnesses easily treated in the U.S.

Lehman returned to Chicago to “a particularly insane week” in the cardiac surgery

Tanganyika, and large boats and trucks are the default for deliveries, but flexibility is key in an area where the few roads might be closed by flooding, armed conflict or even a stalled piece of mining equipment.

“When those options aren’t available, we have to rely on motorbikes, people walking the products and things like dugout canoes,” Montgomery said.

A professional pivot

Lehman arrived on the Tanzanian shore of Lake Tanganyika in 2007 at the onset of a period of personal change.

She’d completed her academic studies after earning simultaneous degrees from the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine and Chicago Booth, and was training to be a general thoracic surgeon.

A close friendship with Alwyn AndrewMziray, AB’94, MD’00, IMBA’00, had

intensive care unit. She was struck by the sometimes-incremental benefits of intensive medical interventions in the U.S. versus the basic healthcare gains the same amount of money would fund in rural Africa.

Then, Lehman’s own health led her to “a professional 180.” She underwent a surgical procedure in 2007 that caused nerve damage, leaving her with chronic pain and, for a while, without use of her right arm.

“I had to totally retrain my arm. I thought to myself, ‘What if physically I can’t do this job that I’ve spent so many years of my young adulthood working towards? What else would I want to do if I couldn’t do that job?’”

Since childhood, Lehman had been primed for helping others. Her father, Ken Lehman, was a Peace Corps volunteer and civically involved, including as a trustee of the University of Chicago Medical Center.

12 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE LTFHC

Amy Lehman, MD, on a 2019 trip to Lake Tanganyika, above left. Children show off their catch after fishing with bed nets, above right. Such repurposing of bed nets has environmental consequences and represents missed opportunities to protect against mosquito bites and prevent malaria.

Devoting her career to the people of the Lake Tanganyika area seemed an obvious choice to Lehman.

“I left my residency before completing it and went off in this other direction,” she said.

Lehman lives in Chicago, but leaves little doubt where her heart lies.

A detailed tattoo of a map of Lake Tanganyika, incorporating an okapi and a cichlid fish, covers her back. It’s a representation of her commitment, Lehman said.

“The idea was to always have a map of the place with me.”

homes in the face of violence and lived in refugee camps for as long as a decade.

In 2011, the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic partnered with another organization to surgically repair obstetric fistulas for dozens of Congolese and Tanzanian women.

In a region without birth assistance, women with obstructed labor can’t get cesarean deliveries. The baby invariably dies and the mother, if she survives, may have internal injuries that result in uncontrollable leaking of feces or urine

collection, crucial to commanding resources, is a major effort of the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic.

Lehman discovered that health information at the community level resided on “all these paper registers. There’s a bunch of arithmetic that gets done, often with mistakes, where you’re abstracting data from all of these registers and then putting that information on another paper booklet. That booklet has to be taken to a regional health office, and then somebody has to manually enter those data,” Lehman said.

The result is that only a small proportion of data is captured, making the plight of these small communities invisible.

Clinic staff began installing solarpowered high-frequency radios in health centers to help with data reporting in 2012. Now, an app developed by the Lake Tanganyika Floating Health Clinic, Iroko Health, is being rolled out to replace the paper registers with digital health records.

It turns out that the work around Lake Tanganyika makes perfect use of Lehman’s dual studies in medicine and business.

Why data is key

The eponymous floating health clinic on Lake Tanganyika remains elusive because of cost and the difficulty of navigating four countries’ borders.

But there is plenty of work to do around the shore aimed at problems ranging from child and maternal mortality to emergency communication and data collection.

Lehman assembled a staff, based in Kalemie in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, whose stories mirror many in the region. One was a child soldier in Laurent Kabila’s “kadogo” army. Others fled their

and often leave her an outcast.

Surgical repair is “really meaningful. It’s her whole existence, her ability to be a functional member of society,” Lehman said.

Such work brings Lehman joy. It also has brought a measure of recognition. In 2014, she was named a Chicagoan of the Year by Chicago magazine. The same year, she received a Distinguished Young Alumni Award from Booth.

Big and daunting tasks are the basis for long-term systemic change, and Lehman doesn’t shy from them. Data

“The Lake Tanganyika basin is breathtakingly beautiful tall mountains and a lake that’s like an inland sea. But I think that for me, Congo is a microcosm of all the things that are most important in the world, about climate, about inequality, about clean energy, about suffering,” Lehman said.

“And yet our global understanding, our investment in just the understanding, let alone constructive engagement, is totally lacking, and that bugs me. And so as long as I have energy to keep broadcasting this message, and to provide data to that effect, I’m going to do it.”

13 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE LTFHC

research burnout well-being wellness medical pandemic medicine time physicians residents stress leadership crisis health responsibilities personal resilience efficiency of practice experience child care solutions early-career support changes fatigue careers healthcare university grants work scientists 14 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians, scientists and healthcare workers call for organizational changes to battle burnout AT A BREAKING POINT

BY EMILY AYSHFORD

Physicians and scientists are often on the front lines of any health crisis, but for years they have battled their own crisis: burnout.

Increasing bureaucratic demands, high patient loads and the early-career pressures to publish research and apply for grants are all factors leading to the classic definition of burnout: stress that causes exhaustion and cynicism, ultimately resulting in a detachment from job responsibilities and a decreased sense of personal accomplishment.

The effects go beyond physicians and scientists. Burnout is estimated to cost the U.S. healthcare system $4.6 billion a year, and high levels of burnout are associated with a decline in patient safety and increased patient dissatisfaction.

In recent years, many hospital and university systems began to recognize the problem and respond, often with a smattering of resources and programming to promote resilience, including meditation and yoga. And perhaps those resources helped a little, or at least put a bandage on the wound. A Medscape survey published in January 2020 showed that burnout rates among physicians had even dropped slightly.

Then came the COVID-19 pandemic.

For physician-scientists like Jade Pagkas-Bather, MD, MPH, the pandemic brought a perfect storm of stressors. As an infectious disease researcher at the University of Chicago Medicine, Pagkas-Bather had been spending her time both in clinics and conducting HIV prevention research.

But in early 2020, she was pregnant, with an ICU physician spouse who was exclusively treating COVID-19 patients. She pivoted to becoming a telehealth infectious disease physician while becoming the default caregiver for her older child. And then her father died in Greece.

“It was a very difficult year, both globally and personally,” she said. “Being a woman in medicine and having a flexible schedule meant that there was a lot of pressure on me to balance child care with my clinical and research pursuits. I was actively working on manuscripts and applying for grants, and it was all incredibly difficult.”

After a tough two years, studies show that burnout is again on the rise. In the 2022 National Burnout Benchmarking report from the American Medical Association, just over half of the survey’s 11,000 respondents reported feelings of burnout. For the first time, the percentage of doctors and clinicians who reported that they were satisfied with the job

dropped. Reports of stress on the job were almost 11 percent higher among female respondents, and young women reported higher rates of burnout due to disruptions in child care.

With it came a clear demand: No more yoga.

“Too much focus has been placed on individual wellness and not enough on systematic solutions to improve ease of practice,” said Vineet Arora, MD, AM’03, Herbert T. Abelson Profesor of Medicine and Dean for Medical Education. “The focus has to be on system solutions as opposed to individual solutions.”

Across the country, administrators are hearing the call and are prioritizing the well-being of physicians, clinicians and scientists through changes in processes and policies, with an increased recognition that change must happen at all levels.

Considering three domains

Factors that lead to burnout vary across professions, but for many physicians, they include increased work hours and an increased focus on productivity (with a broken fee-for-service model that doesn’t account for where they spend their time), higher administrative workload, electronic health record woes, and lack of leadership support and work/life flexibility.

Add to that a global pandemic and you get the right mix for medicine’s “great resignation.” One survey from the height of the pandemic found that one in five physicians said it was likely they would leave their current practice within two years.

But when thinking about burnout, experts say we should not consider just the state of physicians

Jade Pagkas-Bather, MD, MPH, at home with her newborn daughter, Shiloh, and 2-year-old son, Galit. An infectious disease researcher, Pagkas-Bather received funding to support early-career physician-scientists who are disproportionately affected by caregiving

15 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

PHOTO BY ANNE RYAN

Percentage of doctors and clinicians who reported being unhappy with their current job

within the past two years. “It’s like the lawyers say: hard cases make bad law,” said Bryan Bohman, MD’81. “The pandemic just elevated the problem. We still need to focus on day-to-day processes, culture and leadership.”

As one of the founders of Stanford University’s WellMD Center, which develops programs and interventions for physician well-being, Bohman has been studying burnout for more than 10 years. He and his colleagues ultimately developed a model that considers three domains of physician well-being: efficiency of practice, a culture of wellness and personal resilience. Any sort of work toward decreasing burnout must consider all three areas, and as associate CMO of workforce health and wellness at Stanford, Bohman is considering the best approaches to ensure these domains are attended to not only for the physician workforce, but for all health system employees.

One way that Stanford’s WellMD Center promotes its approach to wellness is through their chief wellness officer course, which helps leaders cultivate expertise in contributing to well-being. “More and more organizations are making a commitment to look at what’s going on within their organization around wellness, especially at the leadership level,”

Bringing wellness to the table

The University of Chicago Medicine recently announced its first chief wellness and vitality officer: Bree Andrews, MD, MPH, Associate Professor

Andrews is charged with assessing the state of wellness and implementing programs that will improve ease of practice, collegiality and resilience while addressing burnout and inefficiencies.

“We want to help physicians be resilient, but we know you can’t yoga yourself into efficiency at the workplace,” said Andrews, who connected with Bohman when she took the Stanford chief wellness officer course earlier this year. “We want to make the workplace work well for our physicians, and then hopefully that helps them feel resilient, as well as more fulfilled in the work they are doing.”

Andrews has begun assessing current wellness activities within each department to find out which are most successful and which need more support. She is not looking to implement a one-size-fits-all approach, but rather to understand and tailor to different needs. “A surgeon will need something different than a primary-care internist,” she said.

But certain issues are at the top of the list and likely are needs shared by many. Electronic health records, for example, have increasingly put more time pressure on physicians, who must contend with a demand for documentation, simultaneous patient care and asynchronous data processing, such as information that becomes available after a patient encounter, like new laboratory values, scan results or questions that arise from patients or their families. System-wide supports for career development, innovative practice and research are also key to wellness in an academic environment.

“Doctors want to spend the time that they have with their patients,” Andrews said. “I know there are many things we can do to make physician efficiency better and to enhance the doctor-patient relationship and trust in the process.”

Perhaps most importantly, having a chief wellness and vitality officer shows that “wellness has a stake at the table,” Andrews said. “We have developed leadership around quality improvement and diversity, equity and inclusion, now is the time we place professional wellness and vitality in the same group.” Leadership at this level promotes excellence in each department, allowing our teams to contribute at the highest levels.

16 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION

PHOTO BY JEAN LACHAT

28%

Bree Andrews, MD, MPH, is the first Chief Wellness and Vitality Officer for the University of Chicago

Getting to the bottom of burnout

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Larry Ozeran, MD’86, decided that enough was enough. As a surgeon, healthcare leader and president of California-based Clinical Informatics, Inc., he was well aware of burnout in the industry and frustrated by the lack of efforts to eliminate the root causes.

He connected with Richard Schreiber, MD, who at the time was associate chief medical informatics officer for the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania; he’s now with Penn State Health. They wrote a paper together and presented at the Association of Medical Directors of Information Systems annual meeting. They also presented a panel discussion at the American Medical Informatics Association international meeting with panel members from three countries. The most prevalent issues, they said, involved the burden of documentation, but also

included other burdens ranging from conflicting regulations to workplace harassment.

Others in the field began to take notice, and so began the End Burnout Group, a working group of 19 clinicians and informatics professionals working to identify root causes of burnout and ultimately eliminate them.

At the top of their list are burdens associated with electronic health records. While much of technology is meant to make human lives easier, many clinicians find these systems originally designed for billing cumbersome. These electronic health record systems must have better usability, and clinicians need to receive better training on how to use them, they say.

But electronic health records aren’t the only issue contributing to burnout. The group also hopes to eliminate conflicting rules and regulations across accrediting

agencies and eliminate prior authorization for procedures. “Prior authorization doesn’t serve a beneficial purpose,” Schreiber said. “Mostly what it leads to is a delay in patients receiving the care they need.”

In addition, they also want to find better ways to encourage healthcare systems to give feedback to clinicians when something goes wrong instead of scolding the physician, which also leads to burnout and to better protect clinicians from workplace harassment by patients and caregivers. “Angry patients now hit nurses and doctors,” Schreiber said. “It’s astounding how often it happens.”

The group proposes engaging a diverse set of stakeholders in four working groups payer, regulation, standards and technical to address the complex situations that enable these causes. For example, rather than clinicians manually

abstracting records for payers, develop systems to automatically code information that has been entered and allow payers to pull the data they need to review the metrics they would like to see, including assessing quality of care.

The group is currently recruiting members and hopes to partner with a national organization to lobby for the policy changes needed to eliminate burnout in the near future, while healthcare systems work to mitigate it now.

“Both mitigation and elimination have to work in parallel,” Ozeran said. “We need the mitigation efforts now to keep clinicians in practice, but ultimately we need to persuade policymakers to make the changes we need. Clinicians understand this is a crisis, but we need to educate those who don’t understand it as a crisis.”

Anyone interested in joining the group can email info@clinicalinformatics.org

41% Percentage of physicians who reported feeling burnout in 2021

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ●

17 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

Male

SOURCES

FOR ALL STATISTICS: MEDSCAPE PHYSICIAN BURNOUT & DEPRESSION REPORT 2022: STRESS, ANXIETY AND ANGER; MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS; ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE; 2022 NATIONAL BURNOUT BENCHMARKING REPORT FROM THE AMA; CHRONICLE OF HIGHER EDUCATION.

Female 56%

In almost every survey relating to burnout, physicians and advanced practice providers list electronic health record (EHR) systems as a contributing factor. Many find the systems time-consuming and unwieldy, but solutions often feel out of reach.

To change that, the University of Chicago Medicine implemented a “#WhatToFix” program to better understand issues plaguing healthcare workers and to find ways to solve them. The program, patterned after Hawaii Pacific Health’s “Getting Rid of Stupid Stuff” program,

involves a periodic survey of six questions disseminated to physicians and advanced practice providers that include two free-text fields where users can describe problems and propose solutions. A team then evaluates potential fixes for feasibility and impact and responds to every single submission.

“That’s the important part,” said Tessa Balach, MD, AB’01, who oversees the project. “And that is what has made it so successful. Often times when people submit suggestions, they think they go into a black box and they might never hear back. But with #WhatToFix, a live person connects with the submitter, whether their problem is fixable or not.”

Stephen Weber, MD, Executive Vice President and Health System Chief Medical Officer, along with Vineet Arora, MD, AM’03, Dean for Medical Education, created #WhatToFix and shepherded it through its pilot phase.

Since its inception in July 2019, the team which is staffed and supported by informatics analyst Kayla Scales and includes several informatics fellows and faculty leaders has received and responded to hundreds of submissions. Many involved electronic health records and resulted in direct changes,

such as adding e-cigarette and vaping usage to social history and improving the format of EKG results.

But the program has gone beyond EHR issues. Other fixes have resulted in policy changes, including changing the carpool parking privileges to include members of the same household who were working the same shift. The team has also obtained discounted memberships for Chicago’s bike sharing program and solicited the Unversity to install more electric vehicle charging stations.

“We are not moving mountains,” said Balach, Associate Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation Medicine. “We’re just getting roadblocks out of the way that might make your day harder. We really love having the opportunity to fix people’s problems. That has made it really fun.”

A newsletter promotes the fixes, thanking both the submitter and the staff member who helped make the fix. This also helps promote a sense of community in an effort to reduce burnout.

“Burnout is often death by a thousand paper cuts,” Balach said. “If this program can help with some of those paper cuts, that is amazing. That’s what we’re aiming to do.”

18 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION

Tessa Balach, MD, AB’01, oversees the #WhatToFix project at UChicago Medicine.

PHOTO BY ANNE RYAN

Addressing burnout from the start

Many students, residents and fellows are looking at the effect the profession has had on their older colleagues and are demanding that wellness have a stake at the table. Often, learning to deal with burnout and addressing the systemic factors that cause it begins in medical school. Students who enter medical school tend to demonstrate higher levels of resilience than their peers, studies show, but they often graduate with higher rates of burnout and depression.

Dru Brenner, MS4, had her own experiences with burnout as an undergraduate. As a premed student, she was focused on making the grades to get into medical school. But when her father died, she realized she needed to take a step back, seek out therapy and take a gap year between college and medical school. When she arrived at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine, she joined the student Wellness Committee, which creates events and programming to help students deal with mental health issues.

“When I came to medical school, it was something I cared about a lot making sure students have space to take time for themselves,” she said. “We are humans. Everyone in the medical profession has some perfectionist tendencies, and it’s easy to get caught up in performing at your maximum all the time. But we don’t have to be those perfect people that we think we are supposed to be.”

The committee also puts on a mental health panel, where students, residents and faculty who have struggled with mental health issues share their stories and experiences. During the early days of the pandemic, students also gathered on Zoom to share their experiences dealing with isolation and loneliness. Brenner also helped start a popular event called “Pritzker I Screwed Up,” where students, residents and faculty talk about a time where they made a mistake what that mistake was, how they managed it and what the impact was on them. “We want to

help normalize that failing is part of normal medical professional development,” she said.

In addition to events, the Pritzker School of Medicine has worked to make mental health services more available for students, said Wei Wei Lee, MD, MPH, Associate Dean of Students and Director of Wellness Programs.

“Addressing mental health and burnout at the student level is an important foundation for a career in medicine,” she said. “The reality is that even the most esteemed faculty member has had struggles in their life and career, and for the past seven years we have been really focused on reducing mental health stigma and improving access to mental health care for our students.”

In addition to student counseling services, the Wellness Committee has also created a crowdsourced, password-protected document where students can share their experiences with mental health providers in the community.

“It’s important to know that students also do face burnout, for specific reasons such as exams, subjective assessments, mistreatment or a stressful residency application process,” Arora said. “It’s important to not only reduce the stress at these points through solutions focused on the trigger, but also coach students to manage overall stress they will experience in medical careers.”

Surveys show that their efforts are working: the majority of students said they could speak about mental health with their peers without judgment, and almost all agreed that faculty and peers sharing their experiences destigmatized both mental illness and making mistakes.

“I am optimistic,” Lee said. “There has been tremendous momentum across the past 10 years and tremendous recognition that physician burnout is a major workforce issue and major threat to the profession. More and more medical centers around the country are recognizing that intervention and change is necessary.”

$4.6

Estimated cost of physician burnout to the U.S. healthcare system

55%

Percentage of faculty surveyed in 2020 who seriously considered either changing careers or retiring early

19 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

BILLION

physicians surveyed between July and December 2020 said it was likely they would leave their current practice within two years

Ensuring resident wellness Brenner, who is applying for residencies, said she is applying to programs that prioritize wellness something that is more and more common, says Candice Norcott, PhD, Director of Graduate Medical Education Well-Being.

“Residents now know that burnout is not inevitable,” she said. “They don’t just want to accept that their careers and jobs will inevitably kill them one day.”

leave for all residents and fellows “was a starting point in building a foundation for all in ensuring that those with caregiving responsibility are supported,” said Christine Babcock, MD, Associate Dean for Graduate Medical Education.

At minimum, residents often just want small, practical changes to improve their lives, Norcott said. Food that is discounted or free and easy to get. A lounge that’s just for them. Recognition for their work. To address issues like these, Norcott has created a committee of “well-being champions” who will be tasked with using the culture that residents already have a culture that doesn’t shy away from understanding that systemic oppression, violence and racism all need to be considered within the course of patient care to create a more responsive environment that residents can feel good about, which in turn can help them face the threat of burnout.

“Residents today are really going to revolutionize the industry and invest in making medicine better,” she said.

Optimistic for the future

For years, the University of Chicago put on an annual Resilience Week for residents in February with programming aimed at mental health but Norcott said the stress of the pandemic, tied up with a rising awareness of racist violence, made them rethink their approach. Now, they’ve switched the focus from resilience to well-being and shifted the programming to take place over an entire month.

“We continue to see that resident well-being is intricately tied to inclusion and belonging,” she said. “Residents are looking for another way to be talked to about well-being other than resilience.”

In her role, she is working to ensure residents have access to mental health services through pragmatic programming, including a prescheduled 30-minute check-in with an Employee Assistance Program provider. She also ensures that residents understand their insurance coverage and what mental health coverage they have and even provides triage calls when residents need help connecting to therapy.

At a national level, policymakers are recognizing the need to offer residents more support. A recent Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education decision to grant six weeks of paid FMLA

Many are optimistic that the pandemic has become a breaking point for change and for additional resources to combat burnout. In the midst of juggling her career and child care, Pagkas-Bather received a grant (see story on Page 21) to help hire extra staff to assist with her research.

“It took the pressure off,” she said. “I think back to when I first fell in love with HIV research, when I was visiting an AIDS orphanage in Nairobi. Something clicked for me, and that led me on that path. And when I had my first child, I knew that realistically I couldn’t give 100% of my time to my work. Now it’s about reframing my priorities, and grants like this help make things a little bit easier.”

Bohman noted how the influenza pandemic of 1918 led to the so-called Roaring ’20s, and how many universities and hospital systems are taking this opportunity to focus on physician and healthcare worker wellness.

“I remain optimistic,” Bohman said. “We’re going to do so much better in elevating the people in our organizations and not allowing our work lives to detract from the rest of our lives. We have been such workaholics, and now there’s much more of a focus on being able to do your job, go home, be present for your family and still feel like you are accomplishing something and contributing to a better world.”

20 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION

Bryan Bohman, MD’81, one of the founders of Stanford University’s WellMD Center, has been studying burnout for a decade.

1

PHOTO BY JEAN LACHAT

in 5

For early-career physician-scientist caregivers, a bit of funding relief

Sarah Sobotka, MD’09, SM’09, knew that having children could have a short-term impact on a critical time in her career when, as an early-career investigator, she needed to apply for grants and publish her research while treating patients.

Then the pandemic hit, her research was paused, and Sobotka’s child care reality changed from dependable to the never-ending possibility of shutdowns and quarantines. Even now, two years later, the results of the pandemic are still being felt among parents of young children who have, until recently, been ineligible for vaccines. “The reality is that for most of the last two years, at any moment I could get a call that a classroom is closed or my child has to test or quarantine,” she said.

Last November, a small bit of relief came from the SECURED program, which stands for Supporting Early Career University Researchers to Excel through Disruptions. The program provides additional funding to early-career clinician-scientists who are disproportionately affected by caregiving responsibilities.

To create the grants, the University of Chicago Medicine received $550,000 from the COVID-19 Fund to Retain Clinical Scientists, supported by the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation in concert with the American Heart Association, Burroughs Wellcome Fund, John Templeton Foundation, Rita Allen Foundation and Walder

Foundation. The funding was matched with $110,000 from the Department of Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, Center for Healthcare Delivery Science and Innovation and Institute for Translational Medicine. Vineet Arora, MD, AM’03, and Olufunmilayo I. Olopade, MD, are the Principal Investigators.

Nine UChicago Medicine clinician-researchers received the funds, which will cover “extra hands” in the form of hiring staff support or supporting time away from clinical responsibilities to help clinical researchers maintain productivity. The grants are targeted at supporting women, those who are disabled and those in groups that are underrepresented in medicine or science or from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“We know that early career faculty are among the group that were disproportionately affected by caregiving responsibilities during the pandemic while at a critical time in their careers,” said Anna Volerman, MD, who co-directs the program. “Even now, as much of the world is moving on, these groups must still deal with child care disruptions. The SECURED program is an opportunity to support individuals who have demonstrated incredible promise but who are in a very vulnerable period that could impact their careers.”

Sobotka, a developmental and behavioral pediatrician, applied for and received the grant, which she is using to protect her

research time. “It enables real support and acknowledgement of people who are trying to succeed in scholarly careers despite other enormous demands on their time,” she said.

When Jade Pagkas-Bather, MD, MPH, an infectious disease specialist, found herself the primary caregiver for her child (and then a second one who was born in October 2020)

she said. “My work is something that I am really passionate about, and this grant really recognizes that clinician-scientists have a difficult road, with the funding climate and pandemic. I really appreciate the support.” For Sobotka, the pandemic had its upside, as well: Virtual visits offered a new way for her to connect with her young patients who have complex health needs

while doing telehealth visits with COVID-19 patients, she had to put her grant applications and manuscripts on hold. The SECURED grant will allow her to further her training in data analytics and hire a data analyst to help complete her research.

“That will allow the wheel to keep on turning on my research,”

and disabilities. And taking care of her own children has given her an intimate vantage point on growth and development that has improved her own research, she said.

“Physician mothers and fathers gain insight and empathy in having that life experience,” she said. “It’s worth investing in.”

21 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

Pediatrician Sarah Sobotka, MD’09, SM’09, with her husband, Elliott Riebman, and children Ava, 7, Eliza, 4, and Zachary.

PHOTO BY ANNE RYAN

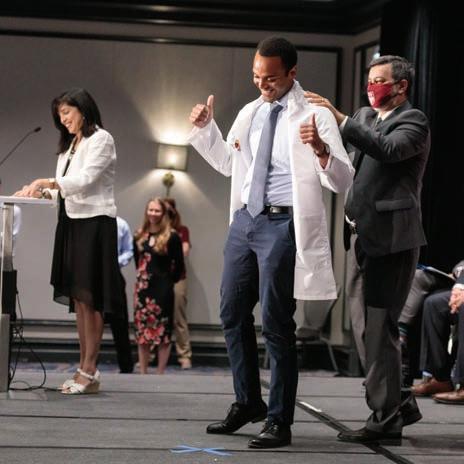

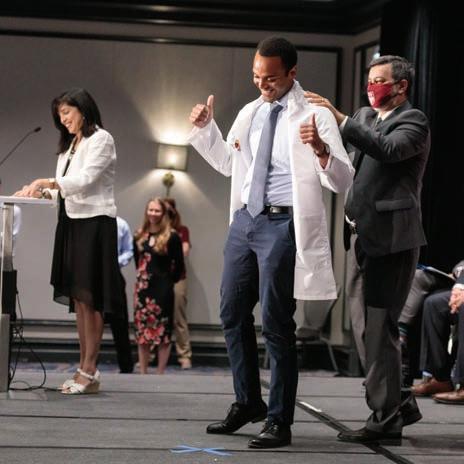

Cardiology fellow Shirlene Obuobi, MD’18, wrote her first novel, On Rotation, during her internal medicine residency. A second novel will be published in 2024.

The whirlwind year of Dr. Obuobi, Shirlene and ShirlyWhirl

BY JAMIE BARTOSCH

Shirlene Obuobi, MD’18, slips on her freshly ironed University of Chicago Medicine white coat and gently pushes her long braids behind her shoulder.

She’s posing for a magazine photo, to appear with the latest in a series of media interviews she’s done since her debut novel, On Rotation, received critical acclaim and interest from Hollywood movie producers.

Obuobi wrote parts of the novel on her phone during her internal medicine residency at UChicago Medicine, often typing a few sentences into a Google Doc as she walked down the hospital halls or during lulls on nights. Writing helped her escape the stress of work and COVID-19.

As the photographer starts snapping pictures, Obuobi tries, unsuccessfully, to stifle a big yawn.

“Sorry,” she says, laughing and quickly resuming her pose. “I’m fine. I’m good.”

She is good. Really good. And justifiably tired. Even for someone as chronically busy as Obuobi, this year has been a rocket ship ride.

Now in the second year of her cardiology fellowship at UChicago Medicine, Obuobi finds herself in the strange predicament of having two burgeoning careers at age 29: medicine and writing. She has already sold the international rights to On Rotation. Avon/Harper Collins is set to publish her second novel, Exposure, about a doctor’s struggles with life and love, in the summer of 2024.

A third career also looms: art. Obuobi is a prolific and popular graphic medicine artist who’s amassed more than 35,000 Instagram followers with her comics on @shirlywhirlmd. She’s popular on

22 THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO MEDICINE AND BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES DIVISION

PHOTO BY MARK BLACK

#MedTwitter and other related hashtags, making her a “medfluencer” (a social media influencer in the medical field). It’s led to partnerships with groups like the American Lung Association and GoodRx.

“Medicine informs my art. The two feed off each other,” she said. “I don’t want to quit medicine. I tell people, ‘I don’t have to be in fellowship. I could have finished my residency and gotten a job!’ I truly love clinical medicine. I love cardiology. I love physiology and I love the potential for impact. I think I have talents that can lend themselves to this field, but I really don’t know what the future’s going to look like for me.”

As if all this wasn’t enough, she got married in two different wedding ceremonies this summer (one traditional Ghanaian, one traditional American) and gave the keynote speech at the Alpha Omega Alpha Honor Medical Society induction ceremony at Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School in New Jersey.

“I am squeezing every inch out of my hours now,” she said. “I’m a very good multi-tasker, but even for me, this is a tight juggle. I sacrifice myself. I don’t get much in the way of rest or respite. But it’s been incredible. It’s been surreal.”

Somehow, she seems to be mastering it all. And she’s enjoying the ride as her national profile rises at a sharp ascent.

“A star is born,” tweeted one of her friends, after seeing Obuobi’s appearance on “Good Morning America” on July 5.

Telling her own story

Born in Ghana, Obuobi came to the United States at age 6. She lived in Chicago, Arkansas and Texas before enrolling at Washington University in St. Louis and then at the University of Chicago’s Pritzker School of Medicine.

For her 10th birthday gift, she asked her mother to make bound copies of a novel she wrote. Her birthday party doubled as a book launch, and she gave each guest an autographed copy.

“The title of the book was Tears of Happiness, Tears of Grief, Both I Can Not Handle,” she said, laughing. “I think that tells you what kind of a 10-year-old I was.”

Obuobi stopped writing soon after that, as teachers warned that writing about the Ghanaian-American experience was very niche and not relatable to a wider audience. Discouraged, she spent the next decade focused on other passions: school, science, medicine and drawing.

During her first year at Pritzker, Obuobi attended a talk by Pulitzer Prize-winning Dominican-American author Junot Díaz. He spoke about being a writer of color, encouraging the audience to push against naysayers and tell their stories. His words had a profound impact on her.

“I went home and wrote the first chapter of On Rotation that night. It was like this award-winning author was giving me permission to write again,” said Obuobi, who years later would finish her coming-of-age story about a Ghanaian-American medical school student who is figuring out her career and relationships.

During that time, she kept the book a secret from her friends and co-workers. Even her then-fiancé didn’t know until last year, when she told him she’d landed a literary agent.

“I didn’t want to give people the opportunity to tell me ‘no,’” she said.

Her Pritzker mentors

Pritzker and UChicago Medicine have played instrumental roles in Obuobi reaching this point in her dual careers. It was at Pritzker where Obuobi met the woman she calls her “first true champion” and “medicine mom,” Monica Vela, MD’93.

Vela, a Latina doctor who, at the time, was the school’s Dean for Multicultural Affairs, became Obuobi’s mentor and instilled enough confidence in her that she launched shirlywhirlmd on Instagram during her third year of medical school.

Most shirlywhirlmd comics are funny, giving a glimpse into life as a sleep-deprived medical school student, resident and fellow. Others cast a critical eye on the healthcare industry or touch on issues that

23 MEDICINE ON THE MIDWAY FALL 2022 uchicagomedicine.org/midway

PHOTO BY MARK BLACK