2 minute read

How is epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS) spread? What factors cause the fish to become infected with EUS?

from What you need to know about epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS) – An extension brochure for Africa

©FAO/D. Huchzermeyer, Rhodes University

Advertisement

Figure 17. Serranochromis robustus – Nembwe. Note the deep ulcer containing white necrotic tissue in a fish affected by epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS), Luwombwa River, north Zambia, during 2014.

Often the first indication of EUS is the presence of ulcerative skin lesions that are commonly found in freshwater and estuarine fishes in infected waters.

The presence of lesions often indicates a contaminated or stressed aquatic environment and may be associated with a variety of infections including parasites, bacteria, viruses and fungi, as well as non-infectious causes such as for example toxic algae. Intra-species aggression is believed to be a predisposing factor in some species such as snakehead fish.

Presumptive diagnosis of EUS can be based on Level 1 diagnosis consisting of observation of gross appearance (red spots and open dermal ulcers) and Level II diagnosis using a microscope to detect aseptate branching hyphae in squashed preparations of the muscle underlying gross lesions.

Confirmatory diagnosis requires: 1. histological demonstration of the typical granulomatous inflammation around invasive hyphae (Level II diagnosis) or, 2. isolation of Aphanomyces invadans from the underlying muscle (Level III diagnosis) or, 3. demonstration of genetic material belonging to A. invadans by molecular laboratory means (Level III diagnosis).

©FAO/D. Huchzermeyer, Rhodes University

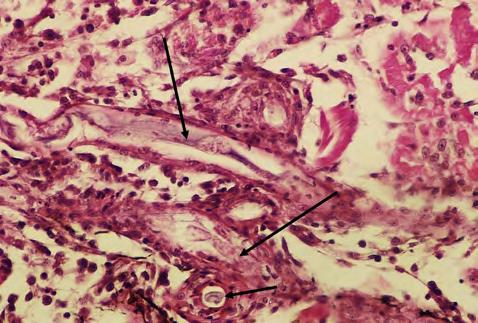

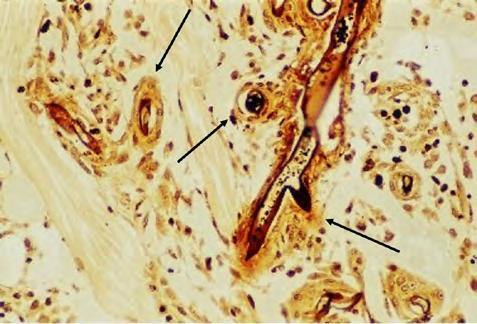

Figure 18. Appearance of hyphae of Aphanomyces invadans within sheaths of macrophages within an area of necrotic muscle in a histological section stained with haematoxylin and eosin (x400 magnification). The sample was collected from a Labeo lunatus suffering from epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS), Botswana, 2007 outbreak period. Long arrows point to hyphae in longitudinal section, short arrows point to hyphae in cross section. Figure 19. Appearance of hyphae of Aphanomyces invadans in a histological section of muscle stained with Grocott’s methenamine stain (x400 magnification). Note that the walls of the hyphae stain almost black and are surrounded by a sheath of macrophages (arrows) within necrotic muscle tissue. The sample was collected from Labeo lunatus during the 2007 outbreak of epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS), Chobe River, Botswana.

Figure 20. Hepsetus odoe – African pike. Note the ulcerative lesion typical of epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS) near the anal fin, Kabompo River, upper Zambezi, 2010.

©FAO/D. Huchzermeyer, Rhodes University

©FAO/R. Bills, South African Institute of Aquatic Biodiversity

©G. Njunga Figure 21. Enteromius paludinosus with epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS) lesions, Kasungu Water Board reservoir dam, Malawi, 2020.

Which species are susceptible or affected?

More than 160 species, worldwide, are susceptible to EUS, including farmed, wild, freshwater and estuarine fish. Many of these have been reported from the Zambezi floodplains.

©FAO/D. Huchzermeyer, Rhodes University

Figure 22. Clarias gariepinus – Sharptooth catfish with multiple deep ulcers caused by infection with Aphanomyces invadans, from the Bangweulu swamps, north Zambia, 2014.

©FAO/R. Peel, Department of Ichthyology and fisheries Science, Rhodes University

Figure 23. Serranochromis robustus – Nembwe with a deep ulceration typical of epizootic ulcerative syndrome (EUS), below Popa Falls, Okavango River, Nambia, July 2010 (Huchzermeyer and Van der Waal, 2012).