Extend your musical journey through the MSO’s Patron Program.

An annual donation of $500 or above brings you closer to the music and musicians you love. Enjoy behindthe-scenes experiences and exclusive gatherings with MSO musicians and guest artists, while building social connections with other music fans and directly supporting your Orchestra.

Scan the QR code to become an MSO Patron today.

In the first project of its kind in Australia, the MSO has developed a musical Acknowledgment of Country with music composed by Yorta Yorta composer Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO, featuring Indigenous languages from across Victoria. Generously supported by Helen Macpherson Smith Trust and the Commonwealth Government through the Australian National Commission for UNESCO, the MSO is working in partnership with Short Black Opera and Indigenous language custodians who are generously sharing their cultural knowledge.

The Acknowledgement of Country allows us to pay our respects to the traditional owners of the land on which we perform in the language of that country and in the orchestral language of music.

As a Yorta Yorta/Yuin composer the responsibility I carry to assist the MSO in delivering a respectful acknowledgement of country is a privilege which I take very seriously. I have a duty of care to my ancestors and to the ancestors on whose land the MSO works and performs.

As MSO continues to grow its knowledge and understanding of what it means to truly honour the First people of this land, the musical acknowledgment of country will serve to bring those on stage and those in the audience together in a moment of recognition as as we celebrate the longest continuing cultures in the world.

– Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO

Our musical Acknowledgment of Country, Long Time Living Here by Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO, is performed at MSO concerts.

Committed to shaping and serving the state it inhabits, the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra is Australia’s preeminent orchestra and a cornerstone of Victoria’s rich, cultural heritage.

Each year, the MSO and MSO Chorus present more than 180 public events across live performances, TV, radio and online broadcasts, and via its online concert hall, MSO.LIVE, engaging an audience of more than five million people in 56 countries. In 2024 the organisation will release its first two albums on the newly established MSO recording label.

With an international reputation for excellence, versatility and innovation, the MSO works with culturally diverse and First Nations artists to build community and deliver music to people across Melbourne, the state of Victoria and around the world.

In 2024, Jaime Martín leads the Orchestra for his third year as MSO Chief Conductor. Maestro Martín leads an Artistic Family that includes Principal Conductor Benjamin Northey, Cybec Assistant Conductor Leonard Weiss CF, MSO Chorus Director Warren Trevelyan-Jones, Composer in Residence Katy Abbott, Artist in Residence

Erin Helyard, MSO First Nations Creative Chair Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO, Young Cybec Young Composer in Residence Naomi Dodd, and Artist in Association Christian Li.

The Melbourne Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the people of the Eastern Kulin Nations, on whose un‑ceded lands we honour the continuation of the oldest music practice in the world.

Tair Khisambeev

Acting Associate Concertmaster

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio#

Anne-Marie Johnson

Acting Assistant Concertmaster

David Horowicz#

Peter Edwards

Assistant Principal

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson#

Sarah Curro

Dr Harry Imber#

Peter Fellin

Deborah Goodall

Karla Hanna

Lorraine Hook

Kirstin Kenny

Eleanor Mancini

Anne Neil#

Mark Mogilevski

Michelle Ruffolo

Anna Skálová

Kathryn Taylor

Matthew Tomkins

Principal

The Gross Foundation#

Monica Curro

Assistant Principal

Dr Mary Jane Gething AO#

Mary Allison

Isin Cakmakçioglu

Tiffany Cheng

Glenn Sedgwick#

Freya Franzen

Cong Gu

Newton Family in memory of Rae Rothfield#

Andrew Hall

Robert Macindoe

Isy Wasserman

Philippa West

Andrew Dudgeon AM#

Patrick Wong

Cecilie Hall#

Roger Young

Shane Buggle and Rosie Callanan#

Christopher Moore

Principal

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio#

Lauren Brigden

Katharine Brockman

Anthony Chataway

William Clark

Morris and Helen Margolis*

Aidan Filshie

Gabrielle Halloran

Jenny Khafagi

Fiona Sargeant

David Berlin

Principal

Rachael Tobin

Associate Principal

Anonymous#

Elina Faskhi

Assistant Principal

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio#

Rohan de Korte

Andrew Dudgeon AM#

Sarah Morse

Rebecca Proietto

Peter T Kempen AM#

Angela Sargeant

Caleb Wong

Michelle Wood

Andrew and Judy Rogers#

Jonathon Coco

Principal

Stephen Newton

Acting Associate Principal

Benjamin Hanlon

Acting Associate Principal

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio#

Rohan Dasika

Acting Assistant Principal

Suzanne Lee

Learn more about our musicians on the MSO website. # Position supported by

Prudence Davis Principal Jean Hadges#

Wendy Clarke

Associate Principal

Sarah Beggs

PICCOLO

Andrew Macleod Principal

OBOES

Michael Pisani Acting Principal

Ann Blackburn

COR ANGLAIS

Rachel Curkpatrick Acting Principal

CLARINETS

David Thomas Principal

Philip Arkinstall Associate Principal

Craig Hill

Rosemary and the late Douglas Meagher#

BASS CLARINET

Jonathan Craven Principal

Jack Schiller

Principal

Dr Harry Imber#

Elise Millman

Associate Principal

Natasha Thomas

Patricia Nilsson and Dr Martin Tymms#

Brock Imison Principal

HORNS

Nicolas Fleury Principal

Margaret Jackson AC#

Peter Luff

Acting Associate Principal

Saul Lewis

Principal Third

The late Hon Michael Watt KC and Cecilie Hall#

Abbey Edlin

The Hanlon Foundation#

Josiah Kop

Rachel Shaw

Gary McPherson#

Owen Morris Principal

Shane Hooton

Associate Principal

Glenn Sedgwick#

Rosie Turner

John and Diana Frew#

Richard Shirley

BASS TROMBONE

Michael Szabo Principal

TUBA

Timothy Buzbee Principal

TIMPANI

Matthew Thomas Principal

PERCUSSION

Shaun Trubiano Principal

John Arcaro

Tim and Lyn Edward#

Robert Cossom

Drs Rhyl Wade and Clem Gruen#

HARP

Yinuo Mu Principal

ARTISTS

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Benjamin Northey conductor^

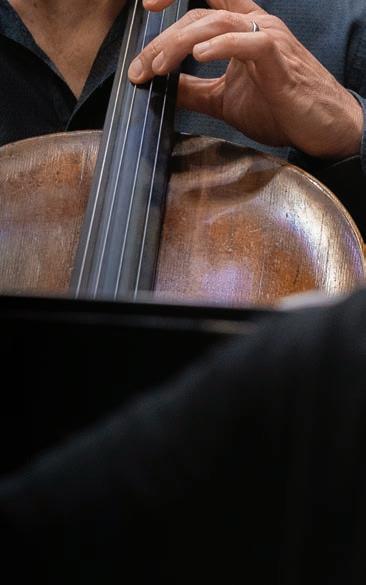

Steven Isserlis cello

^Nodoka Okisawa is unable to conduct this program as originally scheduled.

PROGRAM

AKUTAGAWA Triptyque for String Orchestra [13']

SHOSTAKOVICH Cello Concerto No.1 [28']

– Interval –

NAOMI DODD* RUN** [10']

PROKOFIEV Symphony No.7 [31']

*Cybec Young Composer in Residence

**World premiere of an MSO Commission

CONCERT EVENTS

PRE-CONCERT TALK

Want to learn more about the music being performed? Arrive early for an informative and entertaining pre-concert talk with ABC Classic presenter

Stéphanie Kabanyana-Kanyandekwe and Cybec Young Composer in Residence

Naomi Dodd.

3 & 5 October at 6.45pm in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall.

For a list of musicians performing in this concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

Duration: 2 hours including interval. Timings listed are approximate.

PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR AND ARTISTIC ADVISOR – LEARNING AND ENGAGEMENT

Australian conductor Benjamin Northey is the Chief Conductor of the Christchurch Symphony Orchestra and the Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor – Learning and Engagement of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra.

Northey studied conducting at Finland's Sibelius Academy with Professors Leif Segerstam and Atso Almila and completed his studies at the Stockholm Royal College of Music with Jorma Panula in 2006.

Northey appears regularly as a guest conductor with all major Australian symphony orchestras, Opera Australia (La bohème, Turandot, L’elisir d’amore, Don Giovanni, Così fan tutte, Carmen), New Zealand Opera (Sweeney Todd ) and the State Opera South Australia (La sonnambula, L’elisir d’amore, Les contes d’Hoffmann).

Acclaimed worldwide for his technique and musicianship, cellist Steven Isserlis enjoys a uniquely varied career as a soloist, chamber musician, recording artist, educator, author and broadcaster. He appears with the world’s leading orchestras and conductors, and gives recitals in major musical centres. As a chamber musician has curated concert series for many prestigious venues. Since 1997, he has been artistic director of the International Musicians Seminar at Prussia Cove, Cornwall.

The recipient of many awards, his honours include a CBE in recognition of his services to music, the Schumann Prize of the City of Zwickau, the Piatigorsky Prize and Maestro Foundation Genius Grant (USA), the Gold Medal awarded by the Armenian Ministry of Culture, the Glashütte Original Music Festival Award (Germany), and the Wigmore Medal (UK).

Steven plays the ‘Marquis de Corberon’ Stradivarius of 1726, on loan from the Royal Academy of Music.

Triptyque for String Orchestra

I. Allegro

II. Berceuse (Andante)

III. Presto

Triptyque was written on the commission of Austrian conductor Kurt Wöss, who was then Principal Conductor of the NHK Symphony Orchestra in Japan. Wöss gave its premiere with the New York Philharmonic at Carnegie Hall in December 1953, and the score was subsequently published in the Soviet Union after Akutagawa’s visit there between 1954 and 1955.

Akutagawa had taken the title of his work from Polish-born composer Alexandre Tansman’s Triptyque (1930). The idea of a triptych indeed informs Akutagawa’s conception of the work: although the three movements in Triptyque are separate, they are intrinsically linked through the repeated use of the opening rhythmic figure. The vibrant first movement starts off by presenting this propulsive rhythmic figure that permeates through the texture. While the second-movement Berceuse (lullaby) exhibits a sharp contrast with the first movement, the rhythmic figure has nevertheless remained an integral part of the lyrical theme. Its presence is also highlighted by means of a special playing technique, where the cello- and violaplayers are asked to knock on the body of their instruments. The third movement then brings back the rhythmic figure in its reversed form, and this infuses the music with the momentum that drives towards a festive end.

© Kelvin H. F. Lee 2021 (originally commissioned for the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra)

Cello Concerto No.1 in E flat, Op.107

I. Allegretto

II. Moderato –

III. Cadenza –

IV. Allegro con moto Soloist

Steven Isserlis cello

Mstislav Rostropovich was faced with a dilemma. He was keen for Shostakovich to compose a cello concerto but, perhaps all too aware of his friend’s sensitive nature, he had first asked the composer’s wife what it would take to make Dmitri write one. She advised him that one should never ask (and certainly not beg) her husband to write anything. Rostropovich followed her advice and made no requests to the composer, but sometime later, in 1959, reading the Soviet Art newspaper he discovered that Shostakovich had indeed written a concerto. Soon the cellist was playing through the new work with pianist Alexander Dedyukhin in the presence of the composer, who asked insistently if they liked the music. Once Rostropovich was able to convince him how moved he had been from the first note, Shostakovich humbly asked permission to dedicate his first cello concerto to him. (Shostakovich’s second cello concerto, overtly less virtuosic than the first, was also written specifically for the Russian master cellist, in 1966, and exploited Rostropovich’s genius as an interpretive musician.)

In the E flat concerto, Shostakovich uses almost every sound the cello can make to overcome the difficulties posed by a form composers often avoid. Being a mid-range instrument, the cello is easily swamped when pitted against a full orchestra, and listening to how Shostakovich responds to this challenge

affords almost as much pleasure as his passionate writing for the instrument.

For example, Shostakovich starts by toning down the orchestra, using only double woodwind with piccolo and contrabassoon, one horn, celeste, timpani and strings, and the way he writes for this ensemble is reminiscent of his chamber music. The opening has touches of Stravinsky’s early Neoclassical works. The cello announces the four-note theme that will bind the entire concerto together, and is answered by the winds in a Baroque figure in the home key. The main cello motif (G – E –B – B flat) contains two notes (E and B) which are not in the key of E flat, thus reinforcing the feeling of Stravinskian ‘wrong-note’ harmony.

Shostakovich’s own unmistakable musical personality, however, is soon in evidence. Allowing room for the soloist, the orchestral textures are widely spaced, with high woodwind and deep double basses and contrabassoon creating a dark and distinctly Russian feel. The absence of heavy brass highlights the lone horn whose solo roles throughout the concerto provide a beautiful timbral counterpoint to the cello, often reiterating the soloist’s themes.

The second movement—an A minor moderato—begins with strings in a more Romantic, almost Mahlerian vein. This chromatic, smoothly contoured theme is heard only three times, virtually unchanged and acting as a hinge upon which the movement turns. Its initial exposition is halted by the horn, whose repeated melodic fragment turns out to be a gentle fanfare announcing the solo cello. The subsequent lyrical, drawnout melody inevitably leads back to the string theme, transposed higher and this time reaching a kind of climax. It will return once more before we hear the movement’s highlight: the soloist’s stratospheric harmonics accompanied

by quiet, shimmering strings and the celeste in its only appearance in the score. A solo clarinet takes over from the celeste in an ethereal duet with the cello over plucked bass notes leading straight into the cadenza.

Essentially a link between the slow movement and the finale, the cadenza appropriately has the feel of an improvisation. The soloist shows off a dazzling array of cello techniques in the midst of rapid runs and double stops punctuated by still pizzicato chords. From here, Shostakovich builds cleverly towards the finale, the orchestra entering suddenly with huge chords. They set the dramatic pace for the music ahead which gallops with a folk-like energy towards a final combination of the opening motif from the first movement with the finale’s own two themes. The whole work comes to a crashing end with the timpani, repeating what was once the Baroque answering figure in the woodwinds, and transforming it into an emphatic full-stop.

Rostropovich’s premiere of the work in October 1959 was an unqualified success, and he toured it in the following months to the UK, the US and Australia where it met with popular and critical success, despite its Soviet origins (this was still the Fifties, after all). Undaunted by the Russian cellist’s reputation, other soloists have since taken it up eagerly, cementing its place in both the repertoire, and in audiences’ hearts.

Drew Crawford © 1998

(b. 1997)

The composer writes:

Why does music that is frightening not make me feel afraid, but rather, empowered? From a place of safety, l am drawn towards the imaginary, the fantastic, the fearsome. A quickened heart rate, a spike in adrenaline, my senses on edge—is it terror, or excitement?

For this work, I wanted to write a dramatic composition using the full force of the orchestra, to create a musical experience where people can process big emotions, making them feel empowered and strong!

As well as being influenced by composers such as Prokofiev and Stravinsky, I was also inspired by modern works such as Nautilus by Anna Meredith and different styles of music such as electronic dance music or “EDM”. By incorporating influences from this modern popular style of music, I seek to engage people who might not typically listen to classical music and challenge their preconceptions of what classical music sounds like. In my work you will hear a constant driving pulse, energetic cross-rhythms and even a bass drop!

For me, composing music is a release of my deepest, sometimes intangible thoughts and feelings. I hope that my music will, in turn, enable listeners to connect to their own deep emotions while being captivated and moved by the melodies, textures and colours brought to life by the orchestra.

Run with me, push faster, feel this power and behold the energy of the converging orchestral forces, and then—RUN.

(1891–1953)

Symphony No.7 in C sharp minor, Op.131

I. Moderato

II. Allegretto

III. Andante espressivo

IV. Vivace

Sergei Prokofiev’s Seventh Symphony, completed in 1952, a year before his death, was one of his last works. Controversially, a number of compositions from his final years have had an uneasy history. Some have asserted that these late works are weak, that they portray a composer—by then frail from illness and increasingly impoverished—who possessed little of his former skills. As a recent example, Dorothea Redepenning writes in New Grove: ‘The late instrumental works are curiously colourless, and conspicuous for an almost excessive tendency to simplicity; there is nothing here of the lively nonconformity of the young Prokofiev.’ Others have been even less complimentary. About his final symphony, the composer similarly indicated reservations when, during a rehearsal, he turned to his companions and asked ‘but isn’t the music rather too simple?’

Yet those with a negative opinion of the Seventh Symphony often miss many of its finer nuances, and almost certainly assess the work separately from the circumstances of its composition. With an awareness of the context in which it was written, however, certain aspects of its style and character can be more easily understood. Chief among the factors that contributed to the composer’s difficult final years was a famous resolution on Soviet music in 1948 which attacked Russia’s most gifted composers, of whom Prokofiev was a leading member. Accused of ‘formalism’—an ill-defined notion that,

in its most simplistic reading, related to the use of dissonance, but which could be also levelled as an attack on socialist ideology—his powerful Sixth Symphony was denounced, and his entire output effectively banned from performance. Furthermore, the arrest and incarceration of his foreign-born wife, the deaths of fellow composer and friend, Nikolay Myaskovsky, and film director, Sergei Eisenstein, the subsequent loss of income from performances and prizes, and the rapid erosion of his health, combined to bring about his own death within five years.

In the case of the Seventh Symphony, some of the simplicity for which he has been criticised may stem from its origins as a work intended for the Children’s Radio Division. While some have suggested that writing for a youthful audience may have been an attempt at skirting official censorship, the exact circumstances of its composition are not known. The initial mood of the symphony reveals a stark, and mature, reality, with the plaintive writing at times pared back to just two lines. The wintry tone is soon broken by a theme of extraordinary warmth, the soaring melody being lent a sense of elevation by its rippling accompaniment. A curiously tinkling motif follows in flute and glockenspiel, recalling the magical soundscapes so common to Russian music since the time of Glinka. The instrumentation also draws to mind a ticking clock, an effect that Shostakovich was to use in his final symphony. Perhaps advisedly, Prokofiev proceeds with a typically ‘classical’ development of the material, marking one of the few instances where he adheres to the archaic ‘sonata form’. The themes are again presented, before the movement ends quietly with an unexpected return to the colder tonality of the opening.

The bright and capricious Allegretto movement immediately brings to mind

the composer’s earlier forays into ironical waltzes. As the movement progresses, however, focus is drawn increasingly to the recurrence of fateful pounding rhythms and seemingly portentous moments of subdued orchestration, such as in the theme of the repeated trio section, scored for muted strings. The slow movement revisits a melody that Prokofiev had composed for a theatrical adaptation of Pushkin’s Yevgeny Onegin in 1936. The production never took place, however, as its director, Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky, fell out of favour— perhaps ominously—with Soviet authorities. The short theme is the basis of numerous variations, each utilising an ever wider palette of orchestral colours, and in increasingly disparate keys. Adding contrast is a simple, childlike tune, introduced by the oboe.

The final movement seems most easily identifiable with the audience originally designated for the work, as it noisily bursts forth in a sprightly gallop. A yearning subsidiary theme leads to a playful march, recalling the humour of an earlier youth-oriented work, Peter and the Wolf. The momentum is ultimately broken by a series of heaving chords, leading to the unexpected re-emergence of the broad-winged theme from the first movement. The tinkling bell motif duly follows, but the alternation between major and minor tonalities creates an impression of bittersweet resignation. On this irresolute point, the symphony was originally intended to close. However, Prokofiev was persuaded to change the ending by writing a few further bars, returning with great optimism to the gallop. For some, a sadly forlorn conclusion might potentially trouble an audience, as the symphony’s first conductor, Samuil Samosud, may have pointed out. At the same time, it is difficult to ignore the composer’s dire financial situation, and the knowledge

that such a change would gain his eligibility for a Stalin Prize First Class, worth some 100,000 rubles. Ultimately, the composer decided not to step entirely away from his earlier plan, and the published score states that performance of either ending is valid. Given the many unanswered, and perhaps unanswerable, questions that still surround Prokofiev—such as how much he truly understood of the events of 1917 when he decided to leave Russia, and why he chose to return in the 1930s, when so many liberties were being curtailed—it is perhaps fitting that the close of his final symphony is similarly enigmatic.

Abridged from Scott Davie © 2009

ARTISTS

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Fabien Gabel conductor

Alexandra Dariescu piano

PROGRAM

DEBUSSY (arr. Altinoglu) Pelléas and Mélisande: Suite [22']

C. SCHUMANN Piano Concerto [21']

– Interval –

WAGNER Tristan and Isolde: Prelude and Liebestod [17']

R. STRAUSS Die Frau ohne Schatten: Symphonic Fantasy [15']

CONCERT EVENTS

PRE-CONCERT TALK

Want to learn more about the music being performed? Arrive early for an informative and entertaining pre-concert talk with Karen van Spall.

10 October at 6.45pm in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall.

12 October at 1.15pm in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall.

For a list of musicians performing in this concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

Duration: 1 hour and 45 minutes including interval. Timings listed are approximate.

Fabien Gabel is the newly appointed Music Director Designate of the TonkünstlerOrchester, beginning in the 2025/2026 season. Elsewhere, he has established an international career of the highest calibre, appearing with orchestras such as London Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre National de France, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchester, Oslo Philharmonic, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra, Chicago Symphony, Seoul Philharmonic and Melbourne Symphony Orchestra.

Fabien Gabel performs with soloists such as Daniil Trifonov, Yefim Bronfman, Emmanuel Ax, Jean-Yves Thibaudet, Gidon Kremer, Augustin Hadelich, Vilde Frang, Christian Tetzlaff, Gautier Capuçon, Daniel Mueller-Schott, Emmanuel Pahud, and with singers such as Natalie Dessay and Petra Lang.

Having attracted international attention in 2004 as the winner of the Donatella Flick conducting competition, Fabien Gabel was Assistant Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra 2004–2006. He was music director of Orchestre symphonique de Québec 2012–2021 and Orchestre Français des Jeunes 2017–2021.

Fabien Gabel was named ‘Chevaliers des Arts et des Lettres’ by the French government in January 2020.

Alexandra Dariescu is a trailblazing pianist who demonstrates fearless curiosity in performing diverse and thought-provoking programmes. Dariescu has performed with eminent orchestras such as Orchestre National de France, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Sydney Symphony Orchestra, the Oslo and Copenhagen Philharmonics, alongside conductors such as Ádám Fischer, Sakari Oramo, John Storgårds, Fabien Gabel and Alain Altinoglu.

In 2017, Dariescu took the world by storm with her piano recital production “The Nutcracker and I”, a ground-breaking multimedia performance for piano solo with dance and digital animation. Recent milestones include opening the 2023/24 season for the BBC Symphony Orchestra in the UK premiere of Dora Pejačević’s Phantasie Concertante and the world premiere of a new piano concerto written for her by James Lee III— Shades of Unbroken Dreams—with the Detroit Symphony and BBC Philharmonic orchestras.

Dariescu has released nine albums to critical acclaim, the latest being the Clara Schumann and Grieg Piano Concertos with the Philharmonia Orchestra and Tianyi Lu.

Dariescu is a Laureate at the Verbier Festival Academy and from September 2024, she assumes the role of Professor of Piano at London’s Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

Pelléas and Mélisande: Suite

Like Wagner, Debussy preferred the “lucid exposition of inner motives” to historical incident and physical action in a music drama. In June 1885 he wrote to his patron Eugène Vasnier: “I would always prefer something in which, in some way, action would be sacrificed to the long-pursued expression of the feelings of the soul.”

Debussy found what he was looking for when he attended a performance of Maurice Maeterlinck’s play Pelléas et Mélisande in May 1893. He began sketching ideas for an opera on the subject almost immediately, and when he received Maeterlinck’s permission to use the play he made very few cuts.

Debussy worked at his opera fairly steadily for two years (during which he also completed the Prélude à l’après midi d’un faune), though not without numerous starts and stops. In October 1893, for example, he wrote to the composer Ernest Chausson: “I was hasty in singing a victory song for Pelléas et Mélisande as, after one of those sleepless nights that always is a good counselor, I had to recognize that this wasn’t it at all. The thing resembled a duo of Mr. So-and-So, or it doesn’t matter whom, and most of all the ghost of Old Klingsor, alias R. Wagner, appeared at the turn of a measure. So I tore everything up and struck out searching for a new chemistry of more personal phrases, and strove to become as much Pelleas as Melisande... Quite spontaneously I’ve made use of a means of expression that seems to me quite special, which is silence—Don’t laugh! It acts as an agent of expression and perhaps is the only means of giving

full value to the emotion of a phrase.”

One of the things Debussy did to support himself while composing Pélleas was to play Wagner’s scores—including Tristan—on the piano for private salons. There are many points of connection between Tristan and Pélleas besides the love-and-betrayal storyline, including Debussy’s own highly idiosyncratic use of identifying leitmotifs.

But there are at least as many points of departure, beginning with the use of the French language—Wagner was horrified by the thought of Tristan translated into French—and Debussy’s one-syllable-per-note respect for its inflections. Then there is Debussy’s revolutionary use of silence in many contexts, a psychologically expressive and structurally articulate silence.

Debussy had the vocal score largely completed by the summer of 1895. In the years before Pelléas was finally staged at the Opéra-Comique in 1902, there was much interest in the score among French musicians. Debussy was very reluctant, however, to let the music be heard out of context. He vetoed the idea of concert selections, writing in October 1896 that in such circumstances “you could not hold it against anyone for not understanding the special eloquence of silences, with which the work is star-studded.”

Once the work was well-established— having been performed 100 times in Paris within its first ten years—Debussy was less paranoid about sampling it in concert. After his death several adaptations for orchestra were made, including including this recent version by French conductor Alain Altinoglu. One of the problems confronting Debussy during rehearsal was that he had not allowed enough time for scene changes, so he had to create or extend orchestral interludes in several places.

© John Henken. Reprinted by permission of the author and the Los Angeles Philharmonic.

CLARA SCHUMANN (1819–96)

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op.7

I. Allegro maestoso

II. Romanze (Andante non troppo con grazia)

III. Finale (Allegro non troppo)

Soloist

Alexandra Dariescu piano

On 9 November 1835, Felix Mendelssohn conducted the Gewandhaus Orchestra in the world premiere of Clara Wieck’s Piano Concerto in A minor, with the sixteen-year-old composer as soloist. Clara was a lifelong admirer of Mendelssohn—as Robert Schumann later grumbled, she would ‘glow for hours after a nice word from Mendelssohn’. And indeed, this early concerto reveals even more of Mendelssohn’s influence than it does of Schumann’s.

However, Robert Schumann, who had been living with the Wieck family, was never far away. It was he who had orchestrated the third movement two years earlier, when Clara composed it to stand alone as a Concertsatz. She subsequently added the first two movements, and orchestrated them herself.

The work is an extraordinary achievement for a teenager, particularly as she had never previously composed anything other than miniatures. Like the young Fanny Mendelssohn, Clara Wieck was the beneficiary of an unusual musical education, in this case from her father, the renowned piano pedagogue Friedrich Wieck. Unlike Fanny Mendelssohn, however, Clara was encouraged into the public sphere from an early age—indeed, her father’s finances depended on it. By the time of this concerto, she had been hailed around Europe as a virtuoso of the first order.

The concerto reveals Clara Wieck’s tremendous pianistic culture, and her power as an improviser. It is an exuberant work, and speaks of a young woman’s intoxication with her own abilities. As in Mendelssohn’s earlier concerto in G minor, the movements run through to each other. And while the piano part is composed in bravura, virtuoso style, there are no explicit piano cadenzas.

The first movement consists of only an exposition and development, before setting up the second movement with a modulation to A flat major. Such a modulation was still shocking for the time, and attributable by at least one reviewer to the ‘moods of women’. The slow movement affords a break for the orchestra, and unfolds as a song without words for solo piano, finally joined in its ‘Romance’ by the cello. (There is a clear reference to this pairing in Schumann’s piano concerto of 1845, and perhaps also in the second piano concerto of Clara’s other great admirer, Brahms, which appeared nearly fifty years later.) The third movement, a Polonaise, is the most substantial of the three, and the movement in which the piano most fully engages with the orchestra.

Robert Schumann anonymously and rather purple-ishly celebrated the concerto’s premiere in his journal, the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik:

What we first heard took flight before our eyes like a young phoenix soaring up from its own ashes. Here white yearning roses and pearly lily calyxes inclined their heads; there orange blossoms and myrtle nodded, while alders and weeping willows spread out their shadows…I often spied little boats, hovering daringly over the water…

Shortly after this review, Robert and Clara declared their love, much to the dismay of Friedrich Wieck. Robert then allowed himself to be more succinct about the concerto, in a letter:

‘There are brilliant ideas in the first movement yet it did not make a complete impression on me.’

Clara protested: ‘Do you think I am so unaware that I don’t know the faults of the concerto? I know them well, but the people in the audience don’t know them, and they don’t need to know them.’

Indeed, this concerto remained a successful part of Clara’s touring repertory, until she stopped performing it after her marriage—perhaps because of Robert’s increasingly puritanical views on composer-virtuosos. But the concerto was published in 1837, and continued to sell throughout the nineteenth century. And despite his reservations, Robert Schumann’s own concerto in A minor, of 1845, bears more than a passing resemblance to the work.

Certainly, the concerto indicates much early promise, and can stand proud alongside the early works of more celebrated composers. However, after her marriage, Clara Schumann’s compositional ambitions dwindled. She occasionally presented a piece to her husband, with apologia for her ‘renewed feeble attempts’. But four years after the concerto’s premiere, she wrote that:

‘I once believed that I had creative talent, but I have given up this idea; a woman must not wish to create— there never was one able to do it… May Robert always create; that must always make me happy.’

© David Garrett 2005

RICHARD WAGNER (1813–83)

Tristan and Isolde: Prelude and Liebestod

Die Walküre is often considered the perfect embodiment of the operatic theories Wagner espoused in his book Oper und Drama (1851). In 1851 he had

argued for a balanced relationship between words and music. 1865’s Tristan und Isolde, however, can be listened to almost purely as music. What had caused the elevation of music’s role?

Wagner conceived an opera on the Tristan myth in 1854, around the time of the first complete musical draft of Die Walküre. He interrupted composition on Siegfried, the third opera of his Ring cycle, to compose the music for this work.

Why the interruption? Partly he wanted to give expression to a passion he had conceived for Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of a Zurich silk merchant. And Tristan could indeed be considered opera’s ‘greatest love story ever told’. But there were philosophical considerations as well.

Tristan und Isolde begins with Tristan taking the sorceress Isolde back to Cornwall to wed his uncle, King Marke. But he and Isolde fall into a world-defying love when Isolde’s servant substitutes a love potion for the poison Isolde intended for Tristan. When they are caught, Tristan flees, mortally wounded. He dies as Isolde comes to him, and she expires in expectation of joining him beyond earthly life. This all takes place with a minimum of action, dramatic incident stripped down basically to entrances and exits. Act II is essentially one long love duet.

But Tristan und Isolde is not simple in philosophical or psychological terms. Another reason for Wagner’s interruption from The Ring was the influence on him of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), whose quasi-Buddhist philosophy he needed to digest. Schopenhauer held that music allowed the individual to inhabit ‘will’ itself, rather than sit in the world buffeted by the will’s manifestations. Music was thus the principal art form, a problematic position for a composer who had argued for an equal synthesis of all the arts. In a sense,

composing Tristan was a method of solving this problem. Not that Wagner completely retreated from dramatic intention. Rather, he had found that music, as ‘will’, gave rise to action; action, not text, was music’s new partner.

Following Schopenhauerian thought on transcendence, Wagner gained new insight into his continuing concerns with Romantic ‘love and death’. Isolde, in her ‘love-death’, finally transcends the suffering of her lover’s death and finds fulfilment in a mythical realm.

In trying to convey all this, Wagner almost exhausted Western harmony’s unique ability to express longing. The Prelude begins with four notes of cello in a yearning arc which culminates in the famous ‘Tristan’ chord, a tensely knotted harmony, which unfurls to a merely less dissonant chord. This is the pattern of tension and not-quite release for the next five hours of the opera (and certainly the Prelude).

In concert, the Prelude is often paired with the opera’s very end, the Liebestod, Isolde’s final monologue. This is less dissonant yet still constantly modulating, and thus unsettled. Its melody derives from Act II where Tristan sang: ‘Thus might we die, undivided …’ In Act II, the build-up culminated in an ugly interrupted cadence. Here, finally, there is complete release as Isolde sings of tasting Tristan’s respiration in ‘sweet perfume, in the surging swell, in the ringing sound of the world’s breath’—a flood of sensation suggesting transcendence beyond surfeit.

‘Even if only one person pays for a seat at Tristan, it must be performed for him …’, said Richard Strauss.

© Gordon Kalton Williams 2012

Die Frau ohne Schatten: Symphonic Fantasy

Richard Strauss, then 35, met the upand-coming young writer Hugo von Hofmannsthal, ten years his junior, in 1899, but it was after seeing a stunning performance of Hofmannsthal’s play Elektra, based on the ancient Greek myth, in 1905 that he approached the playwright with collaboration in mind. So began the complicated and by turns fruitful and frustrating working relationship that would result not only in the masterpieces Elektra and Der Rosenkavalier but also such works as the ballet Josephslegende and Der Bürger als Edelmann. The collaboration remained intense from Elektra through about 1917, when Strauss put the finishing touches on the opera Die Frau ohne Schatten. After a hiatus, they worked together again on Die ägyptische Helena (“The Egyptian Helen,” first produced in 1928) and, finally, Arabella, which Strauss completed after Hofmannsthal’s death in 1929.

The sources of these librettos include ancient Greek tragedy, the Hebrew Bible, French comedies of manners, and, for Die Frau ohne Schatten, fairy tale, reflecting Hofmannsthal’s mystic, classicist, and modernist tendencies. Decidedly fixed in early 20th-century aesthetics are the psychological and realist subtleties of characters that reflect the broad outlines of archetypes, whether of the old commedia dell’arte sort or of the Freud/Jung categories that were very much current in the first decades of the century. In Die Frau ohne Schatten, the role-names define the characters’ life status, not their individuality: Emperor and Empress, Nurse, Dyer, and Female Dyer, usually referred to in English as the Dyer’s Wife. (The Dyer does have a name, Barak,

but his identity as a tradesman and merchant are central to the role.) The narrative’s geography is also archetypal, stratified into the realms of the spirit world (i.e., heaven), the in-between realm of the Emperor and Empress, and finally the lower depths: earth, inhabited by rough, flawed mortals who toil for a living. Also, the theme of redemption through self-abnegation and sacrifice is itself a universal narrative.

The initial basis for the libretto was a fairy tale by Wilhelm Hauff (1802–1827), “The Stone Heart,” the fantastic and down-to-earth elements of which appealed to Strauss. According to Strauss biographer Norman Del Mar, Hofmannsthal had hopes of delivering the libretto quickly, but its complex network of allegory and symbolism required several years to work out. Strauss finally completed Frau in summer 1917, but the recent war’s spectre delayed the premiere of this opulent opera for another two years.

The Woman Without a Shadow is the Empress, a semi-divine being who was wooed by the mortal Emperor. For her, a shadow represents a soul as well as fertility and mortality. Her father is an unseen divinity who deems that if she doesn’t acquire a soul within a year (of which three days remain), her Emperor will be turned to stone. Her guardian, the Nurse, reveals that the Empress can acquire a soul from a mortal; if this happens, though, she—as well as the Nurse—will be denied re-entry to the spirit world. They travel to earth, where dwells a mortal pair complementing the Empress and Emperor, the gentle Färber and his restless, frustrated wife, the Färberin (from the German “Farbe,” for colour; both words mean “textile dyer”). The plot revolves around the machinations of the Empress and Nurse to acquire the Dyer’s Wife’s shadow/ soul, but the Empress ultimately must find a more transcendent path.

The Symphonic Fantasy on Die Frau ohne Schatten was an act of practical salvage. Just after World War II the composer was nearly persona non grata, ostensibly for not having fully condemned Hitler’s Nazi program. While Strauss—who turned 70 in 1934—was not directly complicit with the regime, his voice as an artist of significance was deemed insufficiently loud in opposition to the Third Reich’s oppressive practices. Just after the war he spent an extended period in Switzerland, aware that his comfortable Munich home had been commandeered, performances of his music had all but dried up, and his resources were dwindling. It being easier to interest orchestras and promoters in unperformed works than in older scores, Strauss kept in touch with his conductor allies, offering them new works as he produced them. Several of these “new” scores were reconfigurations of decades-old music.

The Symphonic Fantasy on Die Frau ohne Schatten was relatively brief, employed a smaller, more manageable orchestra than did the opera, and contained music that was unfamiliar enough to be novel. It also gave new life to music from the opera that the composer found compelling, notably concentrating on the mortals and their relationships. Writing to a grandson in summer 1946, Strauss stated, “In the meantime, at the request of my new, very capable London publisher Boosey & Hawkes, I have put together an orchestral fantasia from the best parts of Die Frau ohne Schatten, which should make the work somewhat more popular in concert, since opera performances will probably remain impossible for some time to come. You see, one can still accomplish something worthwhile before one’s 82nd birthday if one has been diligent beforehand.”

The Symphonic Fantasy begins with the three-note descending motif in bass

winds intoning “Kaikobad,” naming the Empress’s divine father. This is entwined with a quick motif associated with the Nurse. The main section is based on a melody from an Act I orchestral interlude meant to show the Dyer’s goodness. The shimmering music of the following extended section comes from a scene in which the Nurse shows the Dyer’s Wife the glittering, luxurious world that could be hers if she sold her shadow. This is followed by a lilting theme representing the Dyer’s Wife’s ideal lover conjured up by the Nurse and a passage reconstructing an Act III duet between the Dyer and his wife, solo trombone taking the Dyer’s vocal part. The transformation that the Dyer and his Wife and the Emperor and Empress attain as a reward for self-reflection and self-denial surges through the final orchestral climax.

© Robert Kirzinger 2021. Reprinted by permission of the author and the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Fabien Gabel conductor

DEBUSSY (arr. Altinoglu) Pelléas and Mélisande: Suite [22']

WAGNER Tristan and Isolde: Prelude and Liebestod [17']

R. STRAUSS Die Frau ohne Schatten: Symphonic Fantasy [15']

Artist biographies and program notes for this performance can be found beginning on page 17.

PRE-CONCERT WINE TASTING

Arrive early to enjoy a wine tasting courtesy of TarraWarra Estate, free for ticket holders.

14 October at 5.30pm in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall.

POST-CONCERT TALK

Want to learn more about the music being performed? Arrive early for an informative and entertaining pre-concert talk with Katharine BartholomeuszPlows & Fabien Gabel

14 October at 7.45pm in the Stalls Foyer on Level 2 at Hamer Hall.

For a list of musicians performing in this concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

Duration: 1 hour and 15 minutes, no interval. Timings listed are approximate.

TarraWarra Estate provides you with the perfect backdrop for a day of wine tasting, lunch or simply taking in the views from the deck. Only an hour from Melbourne and you’ll find yourself enjoying our cool climate Chardonnay and Pinot Noir in our subterranean cellar door.

311 Healesville - Yarra Glen Road, Yarra Glen, VIC 3775 Australia +61 3 5962 3311

www.tarrawarra.com.au

_tarrawarra_ /tarrawarra

enq@tarrawarra.com.au

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Christopher Moore director / viola

PROGRAM

R. STRAUSS Metamorphosen [26']

– Interval –

SCHOENBERG Transfigured Night [32']

CONCERT EVENTS

PRE-CONCERT TALK

Want to learn more about the music being performed? Arrive early for an informative and entertaining pre-concert talk with pre-concert talk with Andrew Groch and Christopher Moore.

7 November at 6.45pm in the foyer

For a list of musicians performing in this concert, please visit mso.com.au/musicians

Duration: 1 hour and 30 minutes including interval. Timings listed are approximate.

Principal Viola of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Christopher Moore spent nine years travelling the globe as Principal Viola of Australian Chamber Orchestra. As romantic as that sounds, he missed his old chums Mahler, Schoenberg and Adès, and so returned to these and other old friends at the MSO.

Not surprisingly, Christopher’s wife and two daughters are pleased that Papa has hung up his rock star garb and come home to roost like their pet chickens. If you’re lucky, he may hand you a bona fide free-range egg; if you’re unlucky, you’ll be stuck hearing about how much he loves brewing beer and riding his bike into town from the suburbs, in an attempt to prevent his waistline expanding to the size of his chickens’ coop.

Christopher Moore plays a viola attributed to Giovanni Paolo Maggini dating from circa 1600–10 AD, loaned anonymously to the MSO.

Position supported by Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio.

On 12 April 1945, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra performed Beethoven, Bruckner and Wagner under the baton of Robert Heger before fleeing their ruined city and the advancing Soviet army. Legend has it that members of the Hitler Youth distributed cyanide capsules to the audience following the concert. Three hundred and fifty miles away, in his villa in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Richard Strauss put the finishing touches to his last great orchestral score, Metamorphosen—Study for 23 solo strings.

Strauss had declared his composition career over in 1942 with the premiere of his opera Capriccio and described his later works as mere ‘wrist exercises’. History has judged otherwise and his three great last works are characterised by vastly different emotions: the halcyon lyricism and innocence of the Oboe Concerto (1945), the acceptance of death and resolution of the Four Last Songs (1948) and, in Metamorphosen, a profound lament on the wreckage of Germany around him. Strauss had been particularly devastated by the destruction of The Goethehaus in Frankfurt and of his beloved Dresden. On hearing the news of the destruction of the Bavarian National Theater in 1943, Strauss had sketched out 24 bars of music, which he inscribed ‘Trauer um München’ (Mourning for Munich). Although this material was to feature in the work, the composition of Metamorphosen began in earnest when Strauss was the recipient of a commission from the Swiss conductor and benefactor, Paul Sacher, in July 1944. Sacher conducted the Zurich Collegium Musicum in the premiere of the work on

25 January 1946; although Strauss had conducted a number of the rehearsals, he was said to be too emotional to attend the premiere.

The 25-minute score opens with an intensely chromatic figure in the cellos and double basses that appears to rise from the rubble; despite Strauss’ later tonal idiom, 11 of the 12 notes of the scale are heard in first two bars alone. Strauss then lays out his main thematic material in the 4th and 5th violas, a descending melody that resembles the Marcia funebre from Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony. Strauss denied that he consciously quoted the march, claiming that the music ‘escaped my pen’. The second section is heralded by a shift in tonality, from C minor to G major, and a new tempo Etwas fliessender (‘somewhat more lively’). Despite the major key, there is the overriding feeling that there is no release from the darkness and that the music is based in nostalgia rather than hope. The tension rises before Strauss brutally returns to C minor and the opening material, now fortissimo and played by the full ensemble. As the music subsides, it is clear that Strauss’ grief is inconsolable.

On the final page of the score in the cellos and basses, Strauss directly quotes Beethoven’s Funeral March; for added emphasis, he marks the quote ‘In Memoriam!’. Who exactly Strauss included the quote in memory of is not explained. It could be that Strauss, like Beethoven on Napoleon, was marking the passing of his belief in Hitler. It is also credible that the composer of such autobiographical works as Sinfonia Domestica and Ein Heldenleben saw Metamorphosen as a threnody to his own life and work. Most likely is that this masterly composition marks Strauss’ epitaph on the German cultural life in which he had once shone and which had now catastrophically disintegrated.

Huw Humphreys

(1874–51)

Transfigured Night, Op.4

Transfigured Night (Verklärte Nacht), originally composed for string sextet (two each of violins, violas and cellos), was first performed in Vienna in 1902 by the augmented Rosé Quartet. The first audience was baffled, but the work soon became Schoenberg’s most frequently performed music, and remains his most popular.

To an early critic, this music sounded ‘as if someone had smeared the score of Tristan und Isolde while it was still wet.’ Transfigured Night is neo-Wagnerian and late Romantic, but in retrospect we can see that there is continuity between the 12note Schoenberg and the style of Transfigured Night—both in expressive content and musical technique. The sextet’s tension between chromatic and diatonic harmonies in a complex polyphonic web illustrates the problems which Schoenberg was to face as he pushed further along the same line of stylistic development.

By 1917 ‘amplified’ performances of Transfigured Night for medium-sized string orchestra were being given with Schoenberg’s approval, and in that year he issued a string orchestra version of the work. In 1943 he again reworked the score for orchestral strings, with second thoughts on tempo, dynamics and tone colouring. Whether in this form or as a string sextet, Transfigured Night loads great expression into each line in the texture. Each strand is essential, and needs tensile strength to bear the weight of musical development and emotional expression. Transfigured Night when played by larger forces seems even closer to being, as has been suggested, a tone-poem or a music drama without words.

Transfigured Night was composed in three weeks in 1899 during a holiday spent with the composer Alexander Zemlinsky, whose sister Schoenberg was soon to marry. It was inspired by a poem of Richard Dehmel’s, and possibly by Schoenberg’s own love. The poem comes from a collection titled Weib und Welt (Woman and World, 1896). It is a conversation in a moonlit forest between two lovers, in which the woman tells the man she has conceived a child by another. The man, inspired by the radiance of the natural world, tells her that the warmth now uniting them will transfigure the child and make it theirs. They embrace, and walk on through the ‘bright, lofty night’.

The structure of the ‘symphonic’ drama follows that of the poem itself: five sections, of which the first, third and fifth, describing the lovers’ walking and the setting, frame two more extended statements, one by the woman, one by the man. The music can equally well be experienced as a large-scale single movement, in which the basic thematic motives heard at the beginning are transformed. Schoenberg learnt this method from Wagner, to whose music he had recently been introduced and ‘converted’ by Zemlinsky, having previously regarded himself as a Brahmsian. The most telling example of thematic transformation in Transfigured Night is in the closing pages, where the opening motif is delicately yet radiantly reworked: a Liebesleben (Love-Life) rather than a Liebestod (Love-Death). There are traces of Brahms’ influence too, in the sextet form and the asymmetrical phrasing so characteristic of Schoenberg.

© David Garrett 2001

A star-studded lineup of soloists joins the MSO and MSO Chorus for a rousing performance of Beethoven’s revolutionary Ninth Symphony, culminating in the epic finale, Ode to Joy.

28–30 NOVEMBER

Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall

SCREEN

THEATRE PROJECTIONOUTDOO R EVENTS

EVENT MANAGEMENT

PERFORMANCE RECORDING

LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN

EVENT MANAGEMENT

LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN

CORPORATE COMMUNICATION PERFORMANCE RECORDING

PERFORMANCE RECORDING VIRTUAL R E A LITY

POST PRODUCTION

VIDEO PRODUCTION

THEATRE PROJECTION

CORPORATE COMMUNICATION

VIDEO PRODUCTION

THEATRE PROJECTION

POST PRODUCTION

POST PRODUCTION EVENT MANAGEMENT

CORPORATE COMMUNICATION

PERFORMANCE RECORDING LIVE ST R EAMING

VIDEO PRODUCTION

LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN

POST PRODUCTION

EVENT MANAGEMENT

We present your business at its best…

VIDEO PRODUCTION

LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN

POST PRODUCTION

CORPORATE COMMUNICATION

VIDEO PRODUCTION

THEATRE PROJECTION

EVENT MANAGEMENT

LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN

MANAGEMENT CORPORATE PRODUCTION

LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN PERFORMANCE RECORDING PROJECTION POST PRODUCTION EVENT MANAGEMENT

LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN

CORPORATE COMMUNICATION PERFORMANCE RECORDING POST PRODUCTION

RECORDING VIDEO PRODUCTION LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN POST PRODUCTION

CORPORATE COMMUNICATION PERFORMANCE THEATRE PROJECTION POST PRODUCTION EVENT MANAGEMENT CORPORATE COMMUNICATION VIDEO PRODUCTION LIVE EVENT MANAGEMENT CORPORATE COMMUNICATION PERFORMANCE RECORDING VIDEO PRODUCTION THEATRE PROJECTION POST PERFORMANCE RECORDING VIDEO PRODUCTION LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN THEATRE PROJECTION POST PRODUCTION EVENT MANAGEMENT CORPORATE LIVE CAMERA TO SCREEN THEATRE PROJECTION POST PRODUCTION EVENT MANAGEMENT CORPORATE COMMUNICATION PERFORMANCE RECORDING

CVP Events, Film & Television is Australia’s leading complete vision solutions company

Whether we’re making a television commercial or a piece of corporate communication, recording your performance, using multiple projectors to create a 60metre wide image, providing live to screen services at your concert or managing the entire event for you — at CVP — each component of the event is handled by staff who are specialists in their field.

We believe in excellence — it’s reflected in everything we do.

Her Excellency Professor, the Honourable

Margaret Gardner AC, Governor of Victoria

The Gandel Foundation

The Gross Foundation

Besen Family Foundation

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio

Harold Mitchell Foundation

Lady Primrose Potter AC CMRI

Cybec Foundation

The Pratt Foundation

The Ullmer Family Foundation

Anonymous (1)

Chief Conductor Chair Jaime Martín

Supported in memory of Eva and

Marc Besen

Concertmaster Chair

David Li AM and Angela Li

Cybec Assistant Conductor Chair

Leonard Weiss CF

Cybec Foundation

Acting Associate Concertmaster

Tair Khisambeev

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio

Cybec Young Composer in Residence

Naomi Dodd

Cybec Foundation

Now & Forever Fund: International

Engagement Gandel Foundation

Cybec 21st Century Australian

Composers Program Cybec Foundation

First Nations Emerging Artist Program

The Ullmer Family Foundation

East meets West The Li Family Trust

Community and Public Programs

AWM Electrical, City of Melbourne, Crown Resorts Foundation, Packer Family Foundation

MSO Live Online and MSO Schools

Crown Resorts Foundation, Packer Family Foundation

Student Subsidy Program Anonymous

MSO Academy Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio, Mary Armour, Christopher Robinson in memory of Joan P Robinson

Jams in Schools Melbourne Airport, Department of Education Victoria, through the Strategic Partnerships Program, AWM Electrical, Jean Hadges, Hume City Council, Rural City of Wangaratta, Marian and EH Flack Trust, and Flora and Frank Leith Trust.

Regional Touring AWM Electrical, Creative Victoria, Freemasons Foundation

Victoria, Robert Salzer Foundation, Sir Andrew and Lady Fairley Foundation

Sidney Myer Free Concerts Sidney Myer

MSO Trust Fund and the University of Melbourne, City of Melbourne Event Partnerships Program

Instrument Fund Catherine and Fred Gerardson, Tim and Lyn Edward, Joe White Bequest

PLATINUM PATRONS $100,000+

AWM Electrical

Besen Family Foundation

The Gross Foundation

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio

David Li AM and Angela Li

Lady Primrose Potter AC

Anonymous (1)

VIRTUOSO PATRONS $50,000+

Jolene S Coultas

Dr Harry Imber

Margaret Jackson AC Packer Family Foundation

The Ullmer Family Foundation Anonymous (1)

H Bentley

Shane Buggle and Rosie Callanan

Tim and Lyn Edward

Catherine and Fred Gerardson

The Hogan Family Foundation

Maestro Jaime Martín

Elizabeth Proust AO and Brian Lawrence

Sage Foundation

Lady Marigold Southey AC

The Sun Foundation

Gai and David Taylor

Weis Family

Anonymous (1)

$10,000+

Christine and Mark Armour

John and Lorraine Bates

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson

Jannie Brown

Krystyna Campbell-Pretty AM

Ken Ong Chong OAM

Miss Ann Darby in memory of Leslie J. Darby

Mary Davidson and the late Frederick Davidson AM

Andrew Dudgeon AM

Val Dyke

Jaan Enden

Kim and Robert Gearon

Dr Mary-Jane H Gething AO

Cecilie Hall and the late Hon Michael Watt KC

Hanlon Foundation

Peter Lovell

Dr Ian Manning

Rosemary and the late Douglas Meagher

Farrel and Wendy Meltzer

Opalgate Foundation

Ian and Jeannie Paterson

Hieu Pham and Graeme Campbell

Janet Matton AM & Robin Rowe

Liliane Rusek and Alexander Ushakoff

Glenn Sedgwick

Athalie Williams and Tim Danielson

Lyn Williams AM

The Aranday Foundation

Mary Armour

Alexandra Baker

Barbara Bell in memory of Elsa Bell

Bodhi Education Fund

Julia and Jim Breen

Nigel and Sheena Broughton

Janet Chauvel and the late Dr Richard Chauvel

John Coppock OAM and Lyn Coppock

Cuming Bequest

David and Kathy Danziger

Carol des Cognets

The Dimmick Charitable Trust

Equity Trustees

Bill Fleming

John and Diana Frew

Carrillo Gantner AC and Ziyin Gantner

Geelong Friends of the MSO

Dr Rhyl Wade and Dr Clem Gruen

Louis J Hamon OAM

Dr Keith Higgins and Dr Jane Joshi

David Horowicz

Geoff and Denise Illing

Dr Alastair Jackson AM

John Jones

Merv Keehn and Sue Harlow

Peter T Kempen AM

Suzanne Kirkham

Liza Lim AM

Lucas Family Foundation

Dr Jane Mackenzie

Morris and Helen Margolis

Dr Isabel McLean

Ros and Gary McPherson

The Mercer Family Foundation

Myer Family Foundation

Suzie and Edgar Myer

Anne Neil in memory of Murray A. Neil

Newton Family in memory of Rae Rothfield

Jan and Keith Richards

Dr Rosemary Ayton and Professor Sam Ricketson AM Andrew and Judy Rogers

Guy Ross

Kate and Stephen Shelmerdine Foundation

Helen Silver AO and Harrison Young

Brian Snape AM

Dr Michael Soon

P & E Turner

Mary Waldron

Janet Whiting AM and Phil Lukies

The Yulgilbar Foundation

Igor Zambelli

Anonymous (3)

ASSOCIATE PATRONS $2,500+

Barry and Margaret Amond

Carolyn Baker

Marlyn Bancroft and Peter Bancroft OAM

Janet H Bell

Alan and Dr Jennifer Breschkin

Drs John D L Brookes and Lucy V Hanlon

Lynne Burgess

Dr Lynda Campbell

Oliver Carton

Charles & Cornelia Goode Foundation

Simone Clancy

Kaye Cleary

Leo de Lange

Sandra Dent

Rodney Dux

Diane and Stephen Fisher

Alex Forrest

Steele and Belinda Foster

Barry Fradkin OAM and Dr Pam Fradkin

Anthony Garvey and Estelle O’Callaghan

Susan and Gary Hearst

Janette Gill

R Goldberg and Family

Goldschlager Family Charitable Foundation

Colin Golvan AM KC and Dr Deborah Golvan

Jennifer Gorog

Miss Catherine Gray

Marshall Grosby and Margie Bromilow

Mr Ian Kennedy AM & Dr Sandra Hacker AO

Amy and Paul Jasper

Sandy Jenkins

Jenny Tatchell

Melissa Tonkin & George Kokkinos

Dr Jenny Lewis

David R Lloyd

Margaret and John Mason OAM

Ian McDonald

Dr Paul Nisselle AM

Simon O’Brien

Roger Parker and Ruth Parker

Alan and Dorothy Pattison

Ruth and Ralph Renard

James Ring

Tom and Elizabeth Romanowski

Dr Ronald and Elizabeth Rosanove

Christopher Menz and Peter Rose

Marshall Segan in memory of Berek Segan

OBE AM and Marysia Segan

Steinicke Family

Christina Turner

Dawna Wright and Peter Riedel

Shirley and Jeffrey Zajac

Anonymous (3)

($1,000+)

Dr Sally Adams

Jessica Agoston Cleary

Helena Anderson

Margaret Astbury

Geoffrey and Vivienne Baker

Mr Robin Batterham

Justine Battistella

Michael Bowles & Alma Gill

Allen and Kathryn Bloom

Richard Bolitho

Joyce Bown

Elizabeth Brown

Stuart Brown

Suzie Brown OAM and the late Harvey Brown

Roger and Coll Buckle

Jill and Christopher Buckley

Dr Robin Burns and Dr Roger Douglas

Shayna Burns

Ronald and Kate Burnstein

Daniel Bushaway and Tess Hamilton

Peter A Caldwell

Alexandra Champion De Crespigny

John Chapman and Elisabeth Murphy

Joshua Chye

Breen Creighton and Elsbeth Hadenfeldt

Mrs Nola Daley

Panch Das and Laurel Young-Das

Caroline Davies

Michael Davies and Drina Staples

Sue and Rick Deering

John and Anne Duncan

Jane Edmanson OAM

Grant Fisher and Helen Bird

Frank Tisher OAM and Dr Miriam Tisher

Christopher R Fraser

Chris Freelance

Applebay Pty Ltd

David H Frenkiel and Esther Frenkiel OAM

Mary Gaidzkar

David I Gibbs AM and Susie O'Neill

Sonia Gilderdale

Dr Celia Godfrey

Dr Marged Goode

Hilary Hall, in memory of Wilma Collie

David Hardy

Tilda and the late Brian Haughney

Cathy Henry

Gwenda Henry

Anthony and Karen Ho

Rod Home

Lorraine Hook

Doug Hooley

Katherine Horwood

Penelope Hughes

Jordan Janssen

Shyama Jayaswal

Basil and Rita Jenkins

Jane Jenkins

Emma Johnson

Sue Johnston

Angela Kayser

Drs Bruce and Natalie Kellett

Akira Kikkawa

Dr Judith Kinnear

Dr Richard Knafelc and Mr Grevis Beard

Tim Knaggs

Professor David Knowles and

Dr Anne McLachlan

Dr Jerry Koliha and Marlene Krelle

Jane Kunstler

Ann Lahore

Kerry Landman

Janet and Ross Lapworth

Bryan Lawrence

Phil Lewis

Dr Kin Liu

Andrew Lockwood

Elizabeth H Loftus

Chris and Anna Long

Wayne McDonald and Kay Schroer

Lois McKay

Lesley McMullin Foundation

Dr Eric Meadows

Ian Merrylees

Sylvia Miller

Ian Morrey and Geoffrey Minter

Anthony and Anna Morton

Laurence O'Keefe and Christopher James

George Pappas AO, in memory of Jillian Pappas

Susan Pelka

Ian Penboss

Kerryn Pratchett

Peter Priest

Professor Charles Qin OAM and Kate

Ritchie

Eli and Lorraine Raskin

Michael Riordan and Geoffrey Bush

Cathy Rogers OAM and Dr Peter Rogers AM

Marie Rowland

Jan Ryan

Viorica Samson

Martin and Susan Shirley

P Shore

Janet and Alex Starr

Dr Peter Strickland

Joel and Liora Symons

Russell Taylor and Tara Obeyesekere

Margaret Toomey

Andrew and Penny Torok

Ann and Larry Turner

Dr Elsa Underhill and Professor Malcolm Rimmer

Jayde Walker

Edward and Paddy White

Nic and Ann Willcock

Lorraine Woolley

Dr Kelly and Dr Heathcote Wright

George Yeung

C.F. Yeung & Family Philanthropic Fund

Demetrio Zema

Anonymous (17)

Margaret Abbey PSM

Jane Allan and Mark Redmond

Jenny Anderson

Doris Au

Lyn Bailey

Robbie Barker

Peter Berry and Amanda Quirk

Dr William Birch AM

Robert Bridgart

Miranda Brockman

Dr Robert Brook

Robert and Katherine Coco

Dr John Collins

Warren Collins

Gregory Crew

Sue Cummings

Suzanne Dembo

Carol des Cognets

Bruce Dudon

Dr Catherine Duncan

Margaret Flatman

Brian Florence

Martin Foley

Elizabeth Foster

M C Friday

Simon Gaites

George Miles

David and Geraldine Glenny

Hugo and Diane Goetze

Louise Gourlay OAM

Dawn Hales

George Hampel AM KC and

Felicity Hampel AM SC

Alison Heard

Dr Jennifer Henry

C M Herd Endowment

Carole and Kenneth Hinchliff

William Holder

Peter and Jenny Hordern

Gillian Horwood

Oliver Hutton

Rob Jackson

Ian Jamieson

Wendy Johnson

Leonora Kearney

Jennifer Kearney

John Keys

Lesley King

Heather Law

Pauline and David Lawton

Paschalina Leach

David Willersdorf AM and Linda Willersdorf

Kay Liu

David Loggia

Helen McLean

Joy Manners

Sandra Masel in memory of Leigh Masel

Janice Mayfield

Gail McKay

Shirley A McKenzie

Richard McNeill

Marie Misiurak

Adrian and Louise Nelson

Marian Neumann

Ed Newbigin

Valerie Newman

Dr Judith S Nimmo

Amanda O’Brien

Jeremy O’Connor and Yoko Murakoshi

Brendan O’Donnell

Sarah Patterson

The Hon Chris Pearce and Andrea Pearce

William Ramirez

Geoffrey Ravenscroft

Dr Christopher Rees

Professor John Rickard

Fred and Patricia Russell

Carolyn Sanders

Dr Marc Saunders

Julia Schlapp

Madeline Soloveychik

Stephen and Caroline Brain

Allison Taylor

Hugh Taylor and Elizabeth Dax

Geoffrey Thomlinson

Mely Tjandra

Chris and Helen Trueman

Noel and Jenny Turnbull

Phil Parker

Rosemary Warnock

Amanda Watson

Michael Whishaw

Deborah and Dr Kevin Whithear OAM

Adrian Wigney

Charles and Jill Wright

Richard Ye

Anonymous (15)

Justine Battistella

Shayna Burns

Jessica Agoston Cleary

Alexandra Champion de Crespigny

Josh Chye

Akira Kikkawa

Jayde Walker

Demetrio Zema

MSO GUARDIANS

Jenny Anderson

David Angelovich

Lesley Bawden

Peter Berry and Amanda Quirk

Tarna Bibron

Joyce Bown

Patricia A Breslin

Jenny Brukner and the late John Brukner

Sarah Bullen

Peter A Caldwell

Luci and Ron Chambers

Sandra Dent

Sophie E Dougall in memory of Libby Harold

Alan Egan JP

Gunta Eglite

Marguerite Garnon-Williams

Dr Clem Gruen and Dr Rhyl Wade

Louis J Hamon OAM

Charles Hardman and Julianne Bambacas

Carol Hay

Dr Jennifer Henry

Graham Hogarth

Rod Home

Lyndon Horsburgh

Katherine Horwood

Tony Howe

Lindsay and Michael Jacombs

John Jones

Merv Keehn and Sue Harlow

Pauline and David Lawton

Robyn and Maurice Lichter

Christopher Menz and Peter Rose

Cameron Mowat

Laurence O’Keefe and Christopher James

David Orr

Matthew O’Sullivan

Rosia Pasteur

Penny Rawlins

Margaret Riches

Anne Roussac-Hoyne and Neil Roussac

Michael Ryan and Wendy Mead

Anne Kieni Serpell and Andrew Serpell

Jennifer Shepherd

Suzette Sherazee

Professors Gabriela and George

Stephenson

Pamela Swansson

Tam Vu and Dr Cherilyn Tillman

Frank Tisher OAM and Dr Miriam Tisher

Christina Helen Turner

Mr and Mrs R P Trebilcock

Michael Ullmer AO

The Hon Rosemary Varty

Francis Vergona

Tam Vu and Dr Cherilyn Tillman

Robert Weiss and Jacqueline Orian

Terry Wills Cooke OAM and the late

Marian Wills Cooke

Mark Young

Anonymous (23)

The MSO gratefully acknowledges the support of the following Estates:

Norma Ruth Atwell

Angela Beagley

Barbara Bobbe

Michael Francois Boyt

Christine Mary Bridgart

Margaret Anne Brien

Ken Bullen

Deidre and Malcolm Carkeek

The Cuming Bequest

Margaret Davies

Blair Doig Dixon

Neilma Gantner

Angela Felicity Glover

The Hon Dr Alan Goldberg AO QC

Derek John Grantham

Delina Victoria Schembri-Hardy

Enid Florence Hookey

Gwen Hunt

Family and Friends of James Jacoby

Audrey Jenkins

Joan Jones

Pauline Marie Johnston

George and Grace Kass

Christine Mary Kellam

C P Kemp

Jennifer Selina Laurent

Sylvia Rose Lavelle

Peter Forbes MacLaren

Joan Winsome Maslen

Lorraine Maxine Meldrum

Prof Andrew McCredie

Jean Moore

Joan P Robinson

Maxwell and Jill Schultz

Miss Sheila Scotter AM MBE

Marion A I H M Spence

Molly Stephens

Gwennyth St John

Halinka Tarczynska-Fiddian

Jennifer May Teague

Elisabeth Turner

Albert Henry Ullin

Jean Tweedie

Herta and Fred B Vogel

Dorothy Wood

Joyce Winsome Woodroffe

COMMISSIONING CIRCLE

Cecilie Hall and the Late Hon Michael Watt KC

Tim and Lyn Edward

FIRST NATIONS CIRCLE

John and Lorraine Bates

Equity Trustees

Colin Golvan AM KC and Dr Deborah Golvan

Elizabeth Proust AO and Brian Lawrence

Guy Ross

The Sage Foundation

Michael Ullmer AO and Jenny Ullmer

Margaret Billson and the late Ted Billson

Peter Edwards

Shane Buggle and Rosie Callanan

Roger Young

Andrew Dudgeon AM

Rohan de Korte, Philippa West

Tim and Lyn Edward

John Arcaro

Dr John and Diana Frew

Rosie Turner

Dr Mary-Jane Gething AO

Monica Curro

The Gross Foundation

Matthew Tomkins

Dr Clem Gruen and Dr Rhyl Wade

Robert Cossom

Jean Hadges

Prudence Davis

Cecilie Hall

Patrick Wong

Cecilie Hall and the late Hon Michael Watt KC

Saul Lewis

The Hanlon Foundation

Abbey Edlin

David Horowicz

Anne Marie Johnson

Dr Harry Imber

Sarah Curro, Jack Schiller

Margaret Jackson AC

Nicolas Fleury

Di Jameson OAM and Frank Mercurio

Elina Fashki, Benjamin Hanlon, Tair Khisambeev, Christopher Moore

Peter T Kempen AM

Rebecca Proietto

Morris and Helen Margolis

William Clark

Rosemary and the late Douglas Meagher

Craig Hill

Professor Gary McPherson

Rachel Shaw

Anne Neil

Eleanor Mancini

Newton Family in memory of Rae Rothfield

Cong Gu

Patricia Nilsson

Natasha Thomas

Andrew and Judy Rogers

Michelle Wood

Glenn Sedgwick

Tiffany Cheng, Shane Hooton

Anonymous

Rachael Tobin

Life Members

John Gandel AC and Pauline Gandel AC

Jean Hadges

Sir Elton John CBE

Lady Primrose Potter AC CMRI

Jeanne Pratt AC

Lady Marigold Southey AC

Michael Ullmer AO and Jenny Ullmer

MSO Ambassador

Geoffrey Rush AC

The MSO honours the memory of Life Members

The late Marc Besen AC and the late Eva Besen AO

John Brockman OAM

The Honourable Alan Goldberg AO QC

Harold Mitchell AC

Roger Riordan AM

Ila Vanrenen

Jaime Martín

Chief Conductor

Benjamin Northey

Principal Conductor and Artistic Advisor –Learning and Engagement

Leonard Weiss CF

Cybec Assistant Conductor

Sir Andrew Davis CBE †

Conductor Laureate (2013–2024)

Hiroyuki Iwaki †

Conductor Laureate (1974–2006)

Warren Trevelyan-Jones

MSO Chorus Director

Erin Helyard

Artist in Residence

Karen Kyriakou

Artist in Residence, Learning and Engagement

Christian Li

Young Artist in Association

Katy Abbott

Composer in Residence

Naomi Dodd

Cybec Young Composer in Residence

Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO

First Nations Creative Chair

Artistic Ambassadors

Xian Zhang

Lu Siqing

Tan Dun

Chairman

David Li AM

Co-Deputy Chairs

Martin Foley

Di Jameson OAM

Board Directors

Shane Buggle

Andrew Dudgeon AM

Lorraine Hook

Margaret Jackson AC

Gary McPherson

Farrel Meltzer

Edgar Myer

Mary Waldron

Company Secretary

Demetrio Zema

The MSO relies on your ongoing philanthropic support to sustain our artists, and support access, education, community engagement and more. We invite our supporters to get close to the MSO through a range of special events.

The MSO welcomes your support at any level. Donations of $2 and over are tax deductible, and supporters are recognised as follows:

$500+ (Overture)

$1,000+ (Player)

$2,500+ (Associate)

$5,000+ (Principal)

$10,000+ (Maestro)

$20,000+ (Impresario)

$50,000+ (Virtuoso)

$100,000+ (Platinum)

Join a new generation of giving.

Welcome to Future MSO – an initiative for young philanthropists and music lovers to connect over exclusive opportunities, while supporting the careers of exceptional emerging musicians, conductors and composers at the MSO.

Your tax time donation of $1,000 reveals:

• A community of like-minded, culturally engaged young professionals.

• An annual calendar of events for you and a guest to connect with patrons, MSO musicians and guest artists.

• The inner world of the Orchestra with experiences that bring you closer to the music.

AMPLIFY YOUR IMPACT BY JOINING FUTURE MSO TODAY.

Scan the QR code to join Future MSO today. Or email philanthropy@mso.com.au to discuss your involvement.

PREMIER PARTNER

VENUE PARTNER

INTERNATIONAL LAW FIRM PARTNER

MAJOR PARTNERS

GOVERNMENT PARTNERS

EDUCATION PARTNERS

ORCHESTRAL TRAINING PARTNER

SUPPORTING PARTNERS