TIMELESS TONES

Discover how ChineseAmerican composer Tan Dun weaves the magic of nature into every note

ON THE ROAD

Behind the scenes of taking an orchestra to regional audiences

TIMELESS TONES

Discover how ChineseAmerican composer Tan Dun weaves the magic of nature into every note

ON THE ROAD

Behind the scenes of taking an orchestra to regional audiences

ARIA AWARD-WINNER DAN SULTAN ON CREATIVITY, CULTURE AND COLLABORATION WITH THE MSO

16 The Symphony of Blackbird

Ahead of his concert with the MSO, Australian artist Dan Sultan talks all things creative

22 Sounds of the Earth Landscape and history is where didgeridoo player and composer William Barton finds the music

26 Aural Alchemy Chinese-American composer Tan Dun brings soundscapes that transcend realms

30 In the Regions

It takes a deft balance of organisation, passion and collaboration to take an orchestra regional

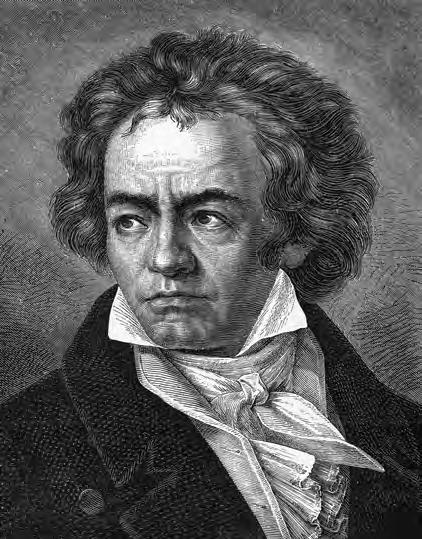

34 Mad About Ludwig The fascinating trajectory in pop culture that’s made Beethoven a household name

36 It’s All Instrumental From the recorder to the classical accordian, unique instruments have a place in the orchestra

40 Rhythm and Flow How movement and motion helps the MSO off and on stage

46 Essay: Beyond Tchaikovsky LGBTIQA+ rights activist Rodney Croome searches for familiar stories in the symphonies

Melbourne-based photographer

Daniel Mahon swapped a corporate career for photography. He left Melbourne for New York, where he worked with leading fashion and portrait photographers. Since returning to Melbourne, Daniel’s work has appeared in publications such as Wallpaper, The Age (Melbourne) magazine, Gourmet Traveller and Frankie. In this issue of Encore, Daniel captured MSO Principal Contrabassoon Brock Imison on page 50.

Blak Douglas is an artist who has won the Kilgour Prize 2019, the STILL Award 2020 and the Archibald Prize 2022. Some of Blak’s collections include Australian Institute of Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Studies, AAMU UtrechtHolland, Artbank, Art Gallery of NSW, Bathurst Regional Gallery, Blacktown, Campbelltown, City of Sydney, Lane Cove & Liverpool Councils, Campbelltown Arts Centre, Grafton Regional Gallery, Maitland Regional Gallery, Manly Art Gallery & Museum, National Gallery of Australia, National Museum of Australia, Newcastle University Art Gallery, NSW Parliament House Collection, Penrith Regional Gallery, and QAGOMA. You can see one of Blak’s illustration on page 47.

Melbourne-born photographer

James Geer began his career as a graphic designer but transitoned over to photography in 1999. Since then, James has worked in New York and been commissioned by ad agencies, entertainment companies and corporates around the world. Noted for his portraiture, he has photographed influential Australians for publications such as Monocle, Gourmet Traveller and Vogue Living. His real passion is documenting Australian lifestyle and producing some of the finest representations of our unique culture. James took the portraits of some of the MSO team in their element on page 40.

Rodney Croome is a long-time advocate for the LGBTIQA+ community in Tasmania and nationally. He fronted the successful campaign to decriminalise homosexuality in Tasmania and was the national director of Australian Marriage Equality. For his work, Rodney was made a Member of the Order of Australia in 2003 and named Tasmanian of the Year in 2015. He lives with his partner, Rafael, in Tasmania. To read about Rodney’s reflections on intergrating LGBTIQA+ loves and lives into classical music, turn to page 46.

Kim Thomson is a writer based in Naarm/Melbourne. She has written on everything from music to the space industry for publications including The Australian and The Saturday Paper. She was also the founding editor of Swampland, an independent music magazine. You will find Kim’s words on page 30, where she looks into the MSO’s regional programs, as well as page 36 where she talks to musicians of wonderfully unique instruments.

Stephanie Bunbury has been a journalist for 40 years, starting at The Age after studying visual arts and politics at Monash University and eventually becoming arts editor. She now lives in London, where she writes for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald, and also covers European film festivals. Last year, the San Sebastian festival honoured her with its annual award of thanks to an international journalist for bringing recognition to culture in the Basque region. Stephanie wrote the cover story on ARIA Awardwinning Dan Sultan on page 16.

Welcome to our sixth edition of Encore magazine; 2024 is hurtling along at a rapid pace so I invite you to take some time out, put your feet up and enjoy a read.

One of the best things about working with the MSO is that we can perform with artists from across the musical spectrum. Our cover artist, Dan Sultan, is a First Nations artist that you might not expect to see on the Hamer Hall stage with a symphony orchestra, and I am excited to introduce our community to one of the most important voices in Australian music.

Another star to join the MSO in 2024 is Academy Award®-winning composer and conductor, Tan Dun. A unique visionary, Tan’s collaborations with the MSO over many years have led to a wonderful artistic friendship, so dive into his story and the incredible artistic moments from throughout his career.

Of course, our 2024 season will culminate with the Orchestra and Jaime Martín performing every single Beethoven symphony as part of the Beethoven Festival in November. Beethoven is a revered figure in both classical and modern music circles; learn how his legacy has earned its place in musical history and pop culture alike.

I hope you enjoy edition six of Encore.

Sophie Galaise, Managing Director, MSOThe MSO respectfully acknowledges the people of the Eastern Kulin Nations as the Traditional Custodians of the unceded land on which we work. We acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging and honour the world’s oldest continuing music practice.

We are proud to collaborate with The Torch to showcase this beautiful artwork in our magazine to accompany our Acknowledgement of Country. The Torch is a not-forprofit organisation that provides art, cultural and arts industry support to Indigenous offenders and ex-offenders in Victoria. This work, called Bunjil Dreaming, was created by Taungurung/Boon Wurrung woman Stacey, who says of the work: “Bunjil is the Creator. This is a spirit that physically takes the form of a wedge-tailed eagle and is a star in the sky at night.” Stacey has traditional connections to the Melbourne region. In 2013, she started working at the Koorie Heritage Trust where she met an Elder who helped her with her family connections. “The Elder told me that I am Taungurung/Boon Wurrung. Since that day, I don’t paint dots anymore. My inspiration is the beautiful designs and patterns from traditional artefacts of my ancestors. Painting diamonds is healing for me.”

Stacey (Taungurung/Boon Wurrung), “Bunjil Dreaming” 2020, acrylic on canvas

Sir Andrew Davis CBE, Chief Conductor of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra from 2013-2019 and celebrated Conductor Laureate, leaves behind a monumental legacy. Over a career spanning more than fifty years, Sir Andrew held prestigious positions worldwide. His roles included Music Director and Principal Conductor of the Lyric Opera of Chicago (2000-2021), Chief Conductor of the BBC Symphony Orchestra (1989-2000), and Music Director of Glyndebourne Festival Opera (1988-2000). He also served the Toronto Symphony Orchestra from 1975-1988 and again as Interim Artistic Director in 2020. “One of the special concerts with Sir Andrew was in 2017 when we played the Tchaikovsky Pathetique Symphony,” recalls former MSO Concertmaster Dale Barltrop. “It was the very first time we played it in Melbourne at Hamer Hall. Sir Andrew just captured it brilliantly.” Sir Andrew’s artistry graced many of the world’s foremost opera houses, including the Metropolitan Opera, Teatro alla Scala, and the Royal Opera House at Covent Garden. His collaborations with leading orchestras such as the Berlin Philharmonic and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra further cemented his larger than life reputation. His extensive discography includes award-winning recordings, such as those of Elgar (winner of the 2018 Diapason d’Or) and Handel’s choral pieces (nominated for a 2018 GRAMMY®). His final releases in 2022 included Berg’s Violin Concerto with the BBC Symphony Orchestra and orchestral works of Carl Vine with the MSO, nominated for an ARIA award. His impact on the MSO will be regarded in ways big and small. “I remember one time we were playing outside,” says horn performer Abbey Edlin. “The orchestra was sitting out in the sun and warming up, and I just saw Sir Andrew sitting on a little park bench, just having a quiet moment to himself. Sometimes it’s hard to find time to catch a moment to yourself when you’re on tour, [but] he stopped and asked how I was doing and if I was enjoying the tour. And I think that’s really nice, it’s special.”

Knighted in 1999 and made a Commander of the British Empire in 1992, Sir Andrew’s unparalleled contributions to music, marked by his passion for both classical and contemporary repertoires, will be long remembered.

PROUST QUESTIONNAIRE

The MSO’s Second Violin Mary Allison reflects on childhood happiness and wanting to learn to laugh at herself as she takes on the Proust Questionnaire.

What is your idea of perfect happiness?

Happiness is being surrounded by my extended family. What is your greatest fear?

Someone I love dying.

Which living person do you most admire?

I most admire violinist Wilma Smith because she combines all the qualities I like in a person: her musicianship, she is very respectful and gracious and she doesn’t have an ego. She is happy to talk to anyone. She is kind and full of fun.

What is your greatest extravagance?

I found this difficult to answer because I don’t consider myself an extravagant person. I live life to the fullest but always with consideration for others.

What is your current state of mind?

I am in a contented state of mind.

What do you consider the most overrated virtue?

Why would you argue that a virtue is overrated? Maybe righteousness because if someone is too righteous, they can become judgemental. They become self-righteous and that clouds their judgement.

On what occasion do you lie?

I try not to lie. I love cooking and the only white lie I can remember telling is that I once told someone I made a cake that I had bought from a cake shop. What is the quality you most like in a person?

The quality I most like in a person is kindness. Which words or phrases do you most overuse?

I use the word ‘gorgeous’ a lot, as well as the phrase ‘that is the best thing I have ever done’. I love all of my experiences.

What or who is the greatest love of your life?

The greatest love of my life is easy; it’s my husband Peter. I met him in 1973 and we have journeyed together ever since.

When and where were you happiest?

I remember when I was young thinking I could never be happier. I had a very happy childhood. Maybe that’s because I didn’t know what unhappiness was. Since then, having my two children is a joyful, happy time. Which talent would you most like to have?

I don’t feel the need to have a talent at this time. I am very happy with my life. Perhaps I would like to have the physical skill to climb a mountain but even that is not important.

If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be? I would like to learn to laugh at myself. I tend to take things personally and sometimes get offended by people who tease me. What do you consider your greatest achievement?

My greatest achievement has been holding a position with the MSO since 1987. I love playing amazing music with my talented colleagues. Where would you most like to live?

Where I live now is where I most want to live. I live in a wonderful city and have lovely friends.

What is your most treasured possession?

My most treasured possession is my collection of photographs and maybe my dining room table which I inherited from my mother. Not because of its worth but because it holds a lifetime of family memories.

What is your most marked characteristic?

It depends on who you ask but many people remark on my enthusiasm. What do you most value in your friends?

The quality I most value in my friends is their ability to listen. What other instrument do you wish you could play?

Another instrument of choice would be the voice: I’d like to be able to sing but playing the cello ranks highly too.

Who are your heroes in real life?

My heroes in real life are people who come to the aid of others. What is it that you most dislike?

I try not to dislike things. I try to embrace everything and see the best in humanity.

How would you like to die?

I don’t want to die, but if I have to, it will be in the arms of my beloved. What is your motto?

My motto is ‘Love life: be adventurous, kind and fair’.

To learn more about Mary Allison and her work in the MSO’s regional touring initiatives, turn to page 28.

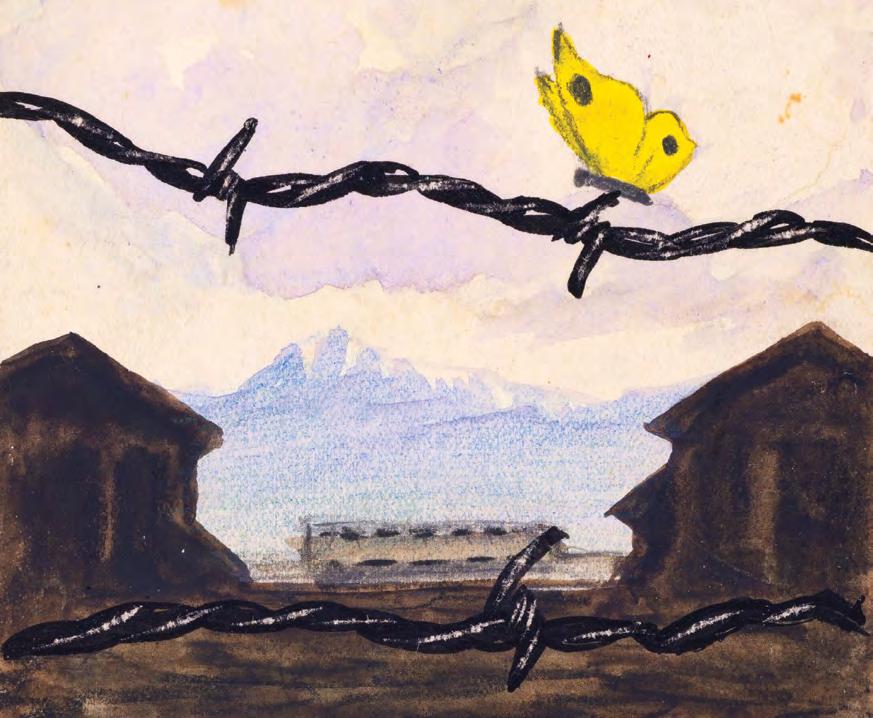

Presented in partnership with the Australian War Memorial

Commemorating 80 years since the liberation of the first execution camps, this special event features 14 works by Holocaust victims and survivors, as well as a new work by Elena Kats-Chernin and William Barton, and Bernstein’s Kaddish Symphony.

Benjamin Northey conductor

Christopher Latham OAM director

31 OCTOBER 7.30PM

Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall

Project partners and supporters:

OF A PATRON

Barry Mowszowski is a driving force behind the MSO’s next-gen patron program, Future MSO. Here he shares the moments that drew him to orchestral music and his vision for nurturing a new generation of philanthropists.

Photography LAURA MANARITIBarry Mowszowski’s first introduction to classical music came by way of his father’s eclectic car trip playlist –Queen, Milli Vanilli and… Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik. “Lucky I was usually in the car with Dad because Mum just played talkback radio!” he laughs.

There was something about the Mozart piece that resonated powerfully with ten-year-old Mowszowski, but it wouldn’t be until two decades later that, on a date to see the Australian Chamber Orchestra play Beethoven in rehearsal, he was revisited by that intense flood of overwhelm. “I just had tears streaming down my face. It evoked the same feeling from when I was in Dad’s car with the visceral impact of the music.” Amazing also to Mowszowski was the fact that more young people weren’t present. “I knew there would be lots of people my age who would love this experience.” And, with a background in marketing and innovation strategy, his mind went into overdrive thinking of what might be possible.

“Orchestral music hasn’t had a history of saying to young people ‘we see you, we want you, we have a home for you’,” says Mowszowski. Rather it’s seen as “overly serious and emotionally removed”. It’s a stereotype Mowszowski has been working to dismantle for some years, and his recent move to Melbourne freshly inspired him to connect people his own age with the MSO and cultivate a new generation of advocates and philanthropists.

“I saw the Tchaikovsky Spectacular at Sidney Myer Music Bowl and got butterflies – how many cities would see 10,000 people

show up in thirty-degree heat for a free classical music concert? Melbourne operates on a unique creative frequency. There was a sense of communal magnetism and I wanted to be part of it.”

Mowszowski collaborated with the MSO Director of Philanthropy and External Affairs, Suzanne Dembo on the idea that would become Future MSO. The initiative was launched in March this year. “We wanted to create something people were excited to be involved with and would bring friends along to build an organic pool of young philanthropists and arts advocates.”

Key to the vision was making it accessible and inclusive, and for the philanthropic aspect of the initiative to come naturally, not from a hard sell. “The donations are a happy by-product of people wanting to be part of this incredible community and to share the unique experiences it offers.”

“Future MSO is foundational to the future of the orchestra,” says Mowszowski. And rather than being seen as a threat to the older membership, it is embraced for its capacity to cultivate an audience that reflects both the diversity of the orchestra and its guests, and of the city of Melbourne. With Future MSO, classical music is saying to a younger demographic “we see you, we want you, we have a home for you.” ■

To find out more about Future MSO, visit mso.com.au/ future-mso.

Highlights of what’s coming up in the second half of 2024.

Carmina Burana’s lyrics were drawn from a collection of medieval poems discovered in the early 19th century in a Bavarian monastery. You’ll need neither a plane ticket nor a time machine to see them come to life, courtesy of the MSO, Jaime Martín and the MSO Chorus in the Ryman Healthcare Season Opening Gala: Carmina Burana. Also in the program is Strauss’ Don Juan – one of the Orchestra’s favourite pieces to perform – and the inimitable William Barton will perform Peter Sculthorpe’s Earth Cry. Ryman Healthcare Winter Gala: Carmina Burana, Thursday 4 and Friday 5 July, 7.30pm, and Saturday 6 July, 2pm, Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne. Proudly presented by Ryman Healthcare.

This November, prepare for a special fortnight celebrating the biggest name in classical music when the MSO performs every Beethoven symphony across 11 days! Conducted by Jaime Martín, the Beethoven Festival – proudly presented by International Law Firm Partner Law Squared – sees a different pairing of symphonies performed every second night, culminating with three performances of the Ryman Healthcare Spring Gala: Beethoven’s Ninth (also featuring the Australian premiere of Sir James MacMillan’s Concerto for Orchestra, co-commissioned by the MSO with the London Symphony Orchestra). Select your favourite symphony or dive headfirst into the entire Festival. And share your love of the MSO with someone who might not have experienced the Orchestra before. Symphonies 1 & 3, Tuesday 19 November, 7.30pm; Symphonies 2 & 5, Thursday 21 November, 7.30pm; Symphonies 4 & 6, Saturday 23 November, 7.30pm; Symphonies 7 & 8 as part of Quick Fix at Half Six, Monday 25 November, 6.30pm; Ryman Healthcare Spring Gala: Beethoven’s Ninth, Thursday 28 and Friday 29 November, 7.30pm and Saturday 30 November, 2pm, proudly presented by Ryman Healthcare. All concerts at Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne.

Few Australian bands have left a musical impression over the past 25 years like Melbourne band The Cat Empire. The band will add to their enduring legacy when they perform their first-ever show with a full orchestra, combining forces with the MSO over three nights in August. Featuring flamenco artists and showcasing Roscoe James Irwin’s vibrant orchestrations of the band’s classic songs and newer material, there is nothing else like this on the MSO calendar in 2024. Expect to be up dancing in the aisles, and all the way home. The Cat Empire with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Thursday 22, Friday 23 and Saturday 24 August, 7.30pm, Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne.

There are webpages dedicated to celebrating the difficulty found in Dmitri Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No.1. That suggests that when superstar cellist Steven Isserlis joins the MSO to perform it, there’s good reason to take your seat. Japanese conductor Nodoka Okisawa makes her Hamer Hall return to lead the Orchestra in a program that also features Prokofiev’s final symphony, his Seventh, and a third work from the 1950s, Yasushi Akutagawa’s Triptyque for String Orchestra.

Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto, Thursday 3 and Saturday 5 October, 7.30pm, Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne.

The MSO’s Melbourne Recital Centre concerts are a way for the Orchestra to showcase works that are more nuanced, and offer some of the MSO’s on-stage leaders to play/direct rather than rely on a conductor. The final Recital Centre program for 2024 will see Principal Viola, Chris Moore lead a program of Richard Strauss’ Metamorphosen (1945) and Schoenberg’s Transfigured Night (1899). Both pieces are emblematic of the late-Romantic and early modern periods of classical music. Moore’s program explores the theme of transformation albeit in different contexts. In Schoenberg’s case the transformative power of love and forgiveness; for Strauss, the devastation of war and the rebuilding that follows. Transformations, Thursday 7 August, 7.30pm, Melbourne Recital Centre.

Max Richter’s The Four Seasons Recomposed is one of the most recognisable compositions of the 21st century. In August, the MSO performs this piece for the first time, alongside the world premiere of Hidden Thoughts III: Stories of Awe, an MSO commission by MSO Composer in Residence Katy Abbott.

Abbott’s piece captures the human experience of awe and features Logie Award-winner, Pamela Rabe. Composed by Benjamin Northey, this is the third and final program in the 2024 MSO Metropolis series, which shines a spotlight on contemporary music and composers.

Vivaldi Recomposed / Hidden Thoughts III, Friday 9 and Saturday 10 August, 7.30pm, Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne.

For ARIA Award-winning Dan Sultan, the right kind of challenge is just the creative spur he needs to sing within that sweet spot, and his recent collaboration with the MSO is exactly that.

Words: Stephanie Bunbury

For Dan Sultan, the key to work satisfaction is feeling out of his depth. “If I’m out of my depth and then able to figure it out and triumph within that space, that’s an amazing feeling,” he says. “As an artist, that’s what I chase, I guess. I think when I’m comfortable, things can get a bit slow for me. That can be pretty unsatisfying.” Right now, the recipient of five physical ARIAs (and participant in two other award-winning projects) is working

O n a surface level , this or that could just be a bit of a pop song, but the thing about good work, for me anyway, is that you can d ive into it and get forensic.

with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra on a concert version of his songs, including the majority of his landmark 2014 album Blackbird. And yes, it’s the kind of challenge he relishes. From the outset, he wanted to work with experienced arranger Alex Turley, a former MSO Cybec Young Composer in Residence who has previously worked with music by artists as diverse as Ali McGregor, Ben Folds and Paul Grabowsky AO. “I didn’t want to hand it over and then have it come back to me and me to sing on top of it,” he says. On this project, he was looking for total immersion.

For as long as he can remember, music has been the fixed point in Dan Sultan’s life. “But not just the music,” he adds. “Knowing I was a musician, that I was an artist and a creative person: that’s something I’ve always known about myself and something that has been a bit of a rock. For a young person, even as a tiny child, to have that knowledge – to know that you’re good at something, that you’re able to do something – is a pretty powerful thing.”

“I wouldn’t go so far as to say my family was not musical,” he says. “But there weren’t instruments in the house or anything like that.” That didn’t stand in his way. He was only four when a family friend gave him a clapped-out electric guitar – with no amplifier – which he then learned to play.

A few years later, he began composing songs, storing them up in his memory until he could get to his grandmother’s house to pick them out on her piano. “And when I was discouraged – by a teacher or by some kids who were maybe a bit jealous – it didn’t really touch the sides for me,” he says. “I enjoyed recognition and still do, but I didn’t necessarily need it.”

Critical recognition came when he released his first album Homemade Biscuits in 2006. With his second album, Get Out While You Can, he won two ARIAs. It wasn’t necessarily an easy life, even so. “It’s a very adrenaline-based lifestyle, whether it’s getting on a stage in front of a big crowd or sitting in a room writing music with a friend,” he says. “Things come along.” Indigenous performers, he says, are expected to be role models in a way their white counterparts never are. “White people aren’t subjected to that – and nor should they be.” Ultimately, he says, to be put on a pedestal is dehumanising. “To take away our individuality is dehumanising – and there have been a lot of appalling things done

to us over the centuries that have been justified by dehumanising us first, so I have zero tolerance for it. People can talk about me however they want, of course, but the only thing I’ll listen to or acknowledge is talking about my work.”

What has really changed his life is happiness. With his wife Bronnie Jane Lee and their two children, family life, he says fervently, is “awesome”. But the songs on Blackbird, by contrast, range from the wild Under Your Skin to the anguished The Same Man

“Every time I sing a song, it changes. That’s the nature of any piece of art, that it is going to mean something different to everybody and to the individual depending on what day of the week it is. But my relationship to that narrative has definitely changed.” He laughs. “I was pretty wild back then. I mean, I was still me. I was still myself. But things were pretty quick.”

Blackbird was recorded over two months in Nashville with Sultan’s then-band members Peter Marin and Joshua Jones. “It was a really beautiful record for me and an amazing time,” he remembers. It embraces multiple musical influences, instruments and musicians – he particularly enjoys the fact that the bluegrass muso who came to play banjo was a Russian, playing in Nashville on an Australian record – all propelled by rock beats. To some, it doesn’t sound like an immediate contender for an orchestral interpretation. Sultan hears it differently.

“I didn’t write Blackbird as a rock album, although that was the ARIA it won,” he says. “Personally, you know, I hear a lot of melody and a lot of chord progressions and relative majors and minors swapping around from verses to bridges. On a surface level, this or that could just be a bit of a pop song, but the thing about good work, for me anyway, is that you can dive into it and get forensic – and then it’s sort of limitless. And I think that’s the case with Blackbird.” He hums a line. “That’s a big upbeat moment in the record. I’m hearing that very cinematic sound with big sweeping strings.”

Dan Sultan is 40, but he says he grew up loving the early rock ’n’ roll of the ‘50s and ‘60s. “Except when I say rock ’n’ roll,” he adds, “I think it was really the times.” He loved it all, from Buddy Holly to Jimi Hendrix. Genre never mattered. “I listened to rockabilly, but soul music as well,” he says. “But I see country music, soul and rock’n’roll as pretty much the same thing. Ray Charles… one of the greatest country artists of all time! And you listen to Willy Nelson and there are some of the greatest soul songs ever written.”

Equally, Blackbird is just as much a work for a symphony orchestra as it is a rock record. ”They’re interchangeable,” he says. “And that’s what I think a good song should be. That same song should be able to work if you’re sitting at a piano or even singing a cappella. And a good artist should be able to do the same work standing in front of an orchestra.” Which is where he will be, of course, well within his depth when the day comes ■

Dan Sultan x MSO, NAIDOC Week Celebration, Friday 12 July and Saturday 13 July, 7:30pm, Hamer Hall .

Didgeridoo/yidaki player and composer William Barton reflects on how travel, a relationship to landscape, and absorbing other cultures have informed the trajectory of his music-making journey.

Words: Stephanie Bunbury

William Barton remembers the first time he walked into a rehearsal room with Queensland’s symphony orchestra as the designated didgeridoo/yidaki player. He was 17, fresh from Mount Isa. “I knew I was going into a very non-Indigenous world, a conservative world,” he says. “Of course I was nervous. But I had the legacy of my people on my shoulders and that’s the pride that I took in with me.”

He had been asked to play a solo on Earth Cry, the late Peter Sculthorpe’s 1986 four-part song inspired by the composer’s return to Australia. Barton is now 42 and has played Earth Cry all over the world; he will play it again with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in July. He has since become a prolific composer himself, but he is still identified with Sculthorpe’s bush reverie. On that first hearing, he says, he recognised a musical ally. “When I heard Sculthorpe’s music, which is very distinct, I thought ‘this is the feeling I want to express myself, as William Barton, who has a First Nations background’,” says Barton. “Even as a young teenager, that was my thing – to create more repertoire for the classical world. And once I had that opportunity, I knew I had a great responsibility.”

Some of his first audiences, he knew, would never have seen an Indigenous performer before. He wanted to show them that the sacred voice of the didgeridoo was comparable to – for example – Gregorian chant. That it had that complexity. “I wanted to make it good. I didn’t want it to be a tokenistic ‘oh, we’re going to add didgeridoo to the orchestra’.”

Barton had grown up in Mount Isa at a nexus of “musical pathways”, from the ceremonial yidaki he learned from Kalkadungu elder Uncle Arthur Peterson to Celtic music at the Mount Isa Folk Club. His mother was fond of Mario Lanza and Enrico Caruso, the popular tenors of a previous generation; young Barton was a hardcore AC/DC fan but would find himself swept away by ABC-FM when the car radio came on as he turned over a cassette. “I just remember, you know, these grand orchestral pieces and thinking ‘Wow, I’d love to play that’,” he says. The didgeridoo line in Sculthorpe’s original Earth Cry score was

shown simply as a squiggly line; it was up to him to improvise, with the composer initially saying things like “more kookaburra!”. It scarcely varies now, but he says the immediacy of improvisation hasn’t waned. “There is always this question: is it improvised or is it not? Well, of course, it is improvised, but my memory is very elastic. The more I play it, the more it’s like a tape playing in my mind.” When he writes now for other instruments, he leaves space for the musician to take his or her journey.

His next original project, to be performed by the Royal Australian Air Force Band at the Shrine of Remembrance, will be a piece he has written with Sydney composer Elena Kats-Chernin to commemorate the Moira man William Cooper, who led an Indigenous protest through the streets of Melbourne after Kristallnacht; it will be performed as part of Music of Memory in October, a program of events reflecting on the Holocaust. Kats-Chernin wrote a piano score that will now be arranged for the orchestra; working with her, Barton gradually improvised a vocal line that will be notated for a choir. His source, he says, is always his culture and his relationship to Country, but he sees a similar relationship between music and spirit everywhere. When he tells a story about composer Leoš Janáček, it is about visiting his house in the Czech Republic and being immediately moved by “the bleak, wintry landscape with a certain eeriness, silence and beauty” the composer must have seen every day; when Barton was in Italy, he travelled nine hours down the road with a driver to visit Mahler’s mountain cabin. In Hawaii, he went out with locals pulling up invasive weeds, connecting with a different country.

“I have a language which is my internal lullaby passed to me by my ancestors,” he says. “I tell people I think you can go anywhere in the world and if you are that kind of person, an improviser, you are improvising the qualities of that landscape. And the Mahlers of this world, Beethoven, Sibelius – they wrote about their landscapes, so their music arose from the land. That comes through in the honesty of the music.” ■

Kaddish: A Holocaust Memorial Concert, 31 October, 7:30pm, Hamer Hall.

Renowned Chinese-American composer Tan Dun returns to the Australian stage, introducing audiences to a melodic parable that transcends time and imagination while exploring the unique tapestry of human connection.

Words: Sarah Vercoe

he past and future have been integral to Tan Dun’s life since he was a young boy growing up in the remote countryside of Hunan, China. “When I was a child I wanted to be a shaman because I thought the shaman could visualise the last life and the next life,” he says. Fascinated by the remarkable cinematic movements of the shaman, Tan Dun was engrossed. “He could express anything he wanted to, and elicit from you any emotion; he wanted to enslave you spiritually, to bring you with him into the future, in the past.”

“That organic soundworld became seductive to me, and I wanted to have that power,” he recalls.

But becoming a shaman wasn’t on the cards for Tan Dun. Soon, he came to realise a musical composer held an advantage over a shaman. “I can transform my reality, my vision of the last life or the next life into a sound, into a colour, to hear it with an audience,” he says.

A notion he’s carried with him throughout his career, and employed in his most recent artistic endeavour alongside the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, Tan Dun’s Nine.

Like an aural wormhole, Nine explores the dialogue between the ancient and now, past and future, and between that which exists and imagination.

When the pandemic took hold, forcing the world to stand still and humans to exist independently of one another, a sense of separateness settled in. Yet while the world took a pause, Tan Dun says his artist's blood and soul ran faster.

Nine evolved out of this separateness. A brick in a bridge designed to reinforce humankind. “The function of music is to bridge everybody together,” he explains. “So, now it’s time to show how and why the Gods needed to invent music for the human being. It must be the bridge to make all these quarantined people, to make all the separate spirits, be together again.”

“The choral concerto Nine is a piece trying to tell people in the world now, we [will] never be separated.”

ith a poignant career in contemporary classical music spanning decades, Tan Dun’s work is a composite of East and West; a dichotomy he expertly explores to bring to life a distinctive sound that’s culminated in international acclaim and a slew of awards and accolades.

For each new piece, Tan Dun says he seeks out a new direction and a new way to look at tradition. “I find going back to tradition will always be an avenue for invention,” he explains of his creative process. “When writing for the conventional string quartet, or writing for the conventional orchestra, if you compose from another angle, another tradition, it becomes an entirely new orchestra,” he says. At every avenue, Tan Dun’s goal is to overcome the knowledge he already has and to find a new mode for the music he’s making. “I always embrace different cultures and traditions, because to assimilate them you constantly have to keep inventing different forms and different techniques to blend them in the styles you are already familiar with,” he explains. For Tan Dun, music has a spiritual function. “It makes you open yourself to accept the whole world and all the people.”

Beyond the fusion of East and West, ancient and contemporary, Tan Dun is known for his innovative use of multimedia. Often incorporating organic elements such as water, paper, and stone as well as audiovisual elements, his inimitable compositions have left an indelible mark on music.

When it came to producing Tan Dun’s Nine, he says the vanished stories, heroes, and voices of the past became his visual platform to write the piece. While his approach can be seen as somewhat abstract, the fundamentals of music allow the listener to feel and experience the story embedded within, says Tan Dun. “The rhythms, the action, the tempos, the repetition, [they all] make the listener feel stories are happening.”

At a deeper level, Tan Dun says composers – from Mozart to Beethoven – are sneaky, using various arrangements and techniques to ‘manipulate the soul’. A psychological approach to art that allows connection, a transfer of feelings, hopes and dreams, of knowledge in a way humanity can comprehend on a multitude of levels. In this way, art can be an impetus that inspires action.

Throughout his illustrious career, Tan Dun has harnessed the power of art as a catalyst for change in the world. Water has been a prominent theme in his life, enlisted as an organic instrument of nature in his hypnotic Water Concerto and now, as a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador, a precious resource he’s dedicated to helping preserve. “Sometimes you feel water is the voice of birth, or rebirth. But now I feel water is like tears, tears of nature,” he says. With the pace of development, Tan Dun warns immediate action is needed to correct the impact humans have had on nature. “I am very concerned about the world and our environment,” he says. “If we continue to disturb nature and pollute our world, we will destroy ourselves.”

Whether you encounter Tan Dun the zealot or Tan Dun the masterful composer, the past and future are an underlying stimulus that resonates throughout his life’s work. The biggest privilege for a composer, says Tan Dun, is that music is a universal language that can tell a story. “I can speak to all kinds of people who come from different traditions, languages, and backgrounds,” he says. ■

Tan Dun: Nine, Saturday 14 September 2024, 7:30pm, Hamer Hall .

A masterful musician, Tan Dun’s music has been performed around the world by leading orchestras. But his repertoire also extends beyond the stage to the big screen, crafting film scores of international acclaim. His most notable film score was for Ang Lee’s celebrated martial arts film, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, for which he won an Academy Award®, a GRAMMY® Award, and a BAFTA Award.

Trained in both Eastern and Western musical styles, Tan Dun says he draws inspiration from each, his immersion in two different worlds of music leading to a distinctive soundworld with a delicate balance of each region. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon’s score is a composite of his musical training, seamlessly blending Chinese harmonies with Western-style orchestra to create a soundtrack with a synergy like no other.

“When writing for the conventional string quartet, or writing for the conventional orchestra, if you compose from another angle, another tradition, it becomes an entirely new orchestra.”

It’s no easy feat to move an orchestra around the country –but regional touring remains a vital and joyful part of the MSO’s schedule. Words: Kim Thomson

usic begets music. When it comes to the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra hitting the road for audiences beyond the major cities, traveling performances remain fond memories for those now involved in making them happen. “When I was a kid, the Sydney Symphony Orchestra, the Australian Chamber Orchestra and the Brandenburg Orchestra would come up and play and I would hear them in regional New South Wales,” says Erin Helyard from the MSO’s tour bus, making its way up to Ballarat for a show. The conductor and current MSO Artist in Residence recalls these shows vividly. “I remember seeing [violin soloist] Richard Tognetti when I was about 16 and it was just phenomenal. Really, I just felt, ‘Oh gosh, that’s what I want to do with my life: I want to be a musician.’”

MSO violinist Mary Allison has similar recollections of performers visiting her tiny hometown in New Zealand. “I can remember, very clearly, groups of musicians or sometimes ballet dance troupes or ensembles that would come to the town I grew up in … and I was just mesmerised,” she says. These days, Allison has collected her own share of experiences on the road as a touring musician. “I’ve played in a huge variety of venues – from farm sheds, where the stage was built over 44-gallon drums – to community sports halls with varying acoustics, and some very sophisticated concert halls.”

While the drums were somewhat earlier in her career, Allison’s had more recent experiences with the MSO, such as visiting Wangaratta while it was in flood and playing in a quartet on an old Art Deco shop floor in Mildura.

She says it’s a delight to play regional shows which can often involve more intimacy with audiences than those in larger cities. “[I love] observing the joy and wonder on their faces during a concert because you can actually see the people in a small hall and you make a connection with them.” Helyard agrees it’s always special to play to audiences in those regions, sometimes situated just a few feet away from people.

“The audience is very close – you can see visible gasps of joy.” Helyard reminds that it’s no easy feat to move an

orchestra around, and the generous backing of the MSO’s donors and supporting foundations is crucial to make regional touring happen. Indeed, Creative Victoria, through its Touring Victoria program, is a key supporter of the MSO’s activity in the regions.

“Regional is really expensive for organisations and it often needs significant subsidising from other sources because you can't rely on just box office – but I think it's worth it,” says Helyard.

A particularly joyful part of MSO’s regional touring schedule for many performers is the schools program, which plays to thousands of primary and high school students each year in towns including Shepparton and Albury–Wodonga.

Matthew Schroeders, manager of Riverlinks venues in Shepparton, says it’s a big highlight of the calendar. “It's quite educational – it's not just music playing ... I think that's the key element to why it’s been so successful,” he says. Sometimes, he explains, performers will dress in different colours so students can clearly see each section of the orchestra and the conductor will describe what they are playing in a deliberately accessible way. Schroeders says his venue’s decades-long partnership with the MSO also fosters important connections with local musicians such as Goulburn Valley Concert Orchestra.

Brendan Maher, venue manager of the Albury Entertainment Centre, which has also been hosting the MSO for decades, agrees the schools program is a very special part of the year.

“For some kids, they might be seeing a concert like this for the very first time – so there’s always a great deal of excitement in the foyer as they come in and then they all sit there very quietly waiting for that very first note.”

He adds that local audiences always relish the chance to see an orchestra of the MSO’s calibre, something that can be easily taken for granted in the city.

This year, the orchestra will return to Ballarat in September, and Shepparton, Wangaratta and Albury in October, for a program showcasing Mendelssohn, Beethoven and more. Also on the regional schedule later this year is Handel’s Messiah, which Helyard will direct in Warragul, Bendigo, and Geelong. Allison says its yearly program is a highlight for her. “I just love Messiah … it’s just one of those rituals you do at Christmas. December isn’t the same without Messiah,” she says.

“Over the last number of years, we've been taking Messiah to the regions where we get together with the local choir as well as our own choir and it's very heartwarming … people come out of the hall beaming.” ■

Jaime conducts Rachmaninov and Dvořák, 28 June, 7:30pm, Costa Hall, Geelong; Dvořák and Bruckner, 6 September, 7:30pm, Costa Hall, Geelong; Beethoven and Mendelssohn, 20 September, 7:30pm, Ballarat Civic Town Hall; An Evening with the MSO: Shepparton, 22 October, 7:30pm, Riverlinks Eastbank, Shepparton; An Evening with the MSO: Wangaratta, 23 October, 7:30pm, Wangaratta Performing Arts & Convention Centre, Wangaratta; An Evening with the MSO: Albury, 24 October, 7:30pm, Albury Entertainment Centre, Albury; Handel’s Messiah, 6 December, 7:30pm, West Gippsland Arts Centre, 7 December, 7:30pm, Costa Hall, Geelong, 13 December, 7:30pm, Ulumbarra Theatre, Bendigo.

The MSO is grateful to the supporters that make regional touring for the MSO possible. Alongside funding from Creative Victoria through Touring Victoria, MSO’s 2024 activity across our State is supported by generous philanthropic partners. In 2024 we celebrate 10 years with the Robert Salzer Foundation, a partnership founded on a shared belief in the value of music to society and continuing Robert Salzer’s legacy of bringing meaningful cultural experiences to Victorians.

“The Sir Andrew and Lady Fairley Foundation proudly supports the MSO’s commitment to highquality music-making in the Greater Shepparton region. The Foundation acknowledges the power of long-term investment and for nearly 60 years has supported programs that inspire achievement within a thriving arts community in Shepparton. Focusing on participation, access to all, opportunity and professional engagement, young musicians in the region, and their valuable teachers, have a unique opportunity to work side-by-side with many of the best musicians in the country.”

“The Angior Family Foundation’s support underscores our mutual dedication to enhancing cultural accessibility and enrichment in every corner of Victoria. Together, we hope to provide important opportunities for local communities to experience the transformative magic of orchestral music firsthand, celebrate the diverse cultural tapestry of Victoria and nurture a profound appreciation for the arts among regional audiences by removing geographic barriers to participation.”

“The mission of Freemasons Foundation Victoria is to improve the lives and opportunities of all Victorians. Music plays such an important role in enhancing community health and wellbeing, and we see our partnership with the MSO as a wonderful way to help those living in regional areas to experience the power of music firsthand. Our support allows thousands of people to enjoy, to learn from the experts and enjoy the talents of these wonderful musicians.”

SYMPHONIES 1 & 3

19 NOVEMBER

SYMPHONIES 2 & 5 21 NOVEMBER

SYMPHONIES 4 & 6

23 NOVEMBER

CONDUCTED BY

SYMPHONIES 7 & 8 25 NOVEMBER

QUICK FIX AT HALF SIX!

SYMPHONY NO.9 28–30 NOVEMBER

RYMAN HEALTHCARE SPRING GALA!

What has given Ludwig van Beethoven’s works such resonance in popular culture? Words: Katie Cunningham

s music professor Scott Davie sees it, there are two different Beethovens. There’s the genius known to devotees of classical music for works such as the Ninth Symphony, the opera Fidelio, and late string quartets like Grosse Fuge. And there’s the pop culture figure, the one immortalised in TikTok skits, on “Bae- thoven” t-shirts and in scenes from films like A Clockwork Orange.

“Beethoven lives in two different ways, I suppose you could say,” says Davie, a classical pianist who also lectures in music at the Australian National University. “There’s even something that in scholarly circles is called ‘the Beethoven myth’, where the imagery that we have of him as this very strong noble face with wild hair doesn’t actually exist. So we sort of invented this character of him.”

Invented or not, the character of Beethoven is a powerful one. His name has become shorthand for seriousness and sophistication; his music an easy way to add drama to any soundtrack.

So why, out of every composer, is it Beethoven that has transcended the classical realm? Part of it, Davie says, is down to “a few lucky works” that caught the popular imagination – pieces like Für Elise and the Moonlight Sonata that resonated broadly. Beethoven stripped away the decoration that someone like Mozart might have used in favour of plain but undeniable musical structures – those famous ‘da-da-da-dummm’ notes of the Fifth Symphony a prime example.

But beyond that, he was also the first composer to redefine what a musician could be. Before Beethoven began publishing his own compositions, a composer always worked for somebody else, writing music to be used in a church or a court or at the service of aristocracy.

“I’m sure there were other composers at the time who thought, ‘I’m worth more than just writing a waltz for a court or an accompaniment for a mass’. But Beethoven was the one who managed to really put it into action,” says Davie. “He was able to show that music could be a level of philosophy – that a piece of music can have a function that is of a higher purpose.”

As Nick Bochner, Head of Learning and Engagement with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra sees it, Beethoven was the first to pioneer that idea of ‘the hero artist’ who obeyed only his muse. Not unlike the Kanye Wests or Björks of today, Beethoven stubbornly set out to make the music he wanted to make, whether or not audiences of the day appreciated it. He was also one of the first to use music to create an “enormous, dramatic arc” that tells a story,

an approach that directly inspired greats like Tchaikovsky and Mahler. But it’s also had modern-day consequences: “I don’t think film scores would be where they are now if it wasn’t for Beethoven, demonstrating how you could create incredible storytelling [with music],” says Bochner.

While Beethoven enjoyed significant success in his lifetime – he was the “hot young thing” in Vienna around the turn of the 18th century, Davie says – he had some foresight over the fact that his works’ greatest appreciation would happen posthumously.

By 1814, he had fallen into a depression, dismayed by the rise of young composers like Rossini who found great success writing music that Beethoven considered little more than a ditty. That changed his approach to composing, ushering in the period of work known as ‘late Beethoven’.

“He thought, ‘Well, maybe if Viennese society doesn’t want me, who am I writing music for?’ And in that period, he started writing for posterity,” says Davie. Many composers of the era had their work die with them – but not Beethoven.

He passed in 1827, aged 56, after a long illness. By the 1830s, artists were creating paintings and sculptures of his image that conferred the composer an almost superhuman status, spurring the beginning of the ‘Beethoven myth’ that Davie mentions. In the centuries that followed, Beethoven’s work has popped up everywhere from soundtracks of popular films to samples in rap tracks.

A great part of what has kept Beethoven at the fore of popular consciousness is simply the resonance his compositions pack. They tackle themes that transcend time: human emotion, pain, and the struggle for achievement against the odds.

“A lot of his music kind of stems from his struggle with his deafness,” Bochner explains. “These days, I don’t know which diagnosis he would have, but he wasn’t great with people.

There’s no evidence that he ever had a significant relationship with a lover of any sort. But all of his music is about overcoming all these difficulties.

Whereas before him, people were all very sort of like, oh, well, [suffering] is the will of God, this is how it should be. But for him, it’s much more like, I am going to transcend and I’m going to succeed. And that just is so well embodied in the music. It just appeals broadly.” ■

Beethoven Festival, 19-30 November 2024, Hamer Hall.

Beethoven is born in Bonn, Germany, initially taught music by his father

Aged 21, Beethoven moves to Vienna

Beethoven publishes his first work, a set of keyboard variations

Beethoven publishes his three Opus 1 piano trios, after building a following as a virtuoso pianist

The ‘early period’ of Beethoven’s work (First Symphony, String Quartet No.1, Op.18) 1989 2002 1984 1977 1975 1971 1969 1940 1902 1845 1827 1825-26 1814 1813 (onwards) 1802-1812 1795 1783 1792 1770 1797-1812

Rapper Nas samples Für Elise in his track I Can

The ‘middle period’ of Beethoven’s work (the Emperor Concerto, the Fifth Symphony, the Moonlight Sonata, the opera Fidelio)

The ‘late period’ of Beethoven’s work (The Ninth Symphony, Mass in D)

Beethoven becomes almost completely deaf, after gradually losing his hearing in the preceding years

Beethoven’s late string quartets – his final works – are written

Beethoven appears as a character in the comedy film Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure

Beethoven dies, following a long period of illness

Beethoven’s home city of Bonn first unveils a Beethoven monument and museum

The third-largest crater on Mercury is named in Beethoven’s honour

Beethoven’s music is sent into outer space, care of the two Voyager probes

Picnic at Hanging Rock features the adagio second movement of Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto in a scene. It wouldn’t be the last time director Peter Weir would use Beethoven’s music

A Clockwork Orange darkly immortalises Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony The Beatles release the track Because, built on the chord progression from Moonlight Sonata played backwards

Disney’s first animated film, Fantasia, brings classical music to a new audience and includes Beethoven’s Symphony No.6

Artist Max Klinger first unveils his own famous Beethoven Monument, depicting the composer as a bare-chested Olympic deity perched on a throne

From classical accordion and recorder to castanets and didgeridoo/yidaki – there’s no limit to what instruments an orchestra can incorporate. Words: Kim Thomson

aime Martín has conducted a few nontraditional instruments in his time at the podium. The MSO’s Chief Conductor says he was recently in Spain, working with flamenco guitar players; elsewhere, he’s conducted concertos for Irish flutes, bagpipes, and electric guitars, and worked with sitar masters Ravi and Anoushka Shankar.

Martín, himself a flautist, says working with players of more unique orchestral instruments is a delight. “We learn a lot, as orchestral musicians, from the artists that play these instruments; maybe they don't play concerts looking at music or perhaps they often improvise – this freedom that they bring into their playing is something that, for us, is useful and encouraging.” It goes to show an orchestra is a malleable thing, which can incorporate all kinds of surprising instrumental additions.

Classical accordionist James Crabb says his instrument may evoke certain preconceptions – but is right at home within an orchestra like the MSO. He says the “one-man band” nature of the accordion means it can essentially act as an “orchestra within an orchestra” and being both a keyboard and wind instrument lends it a striking versatility. “We can really shift the dynamic like a wind player or a singer, which is incredible,” he says. Crabb picked up the instrument at the age of four in Scotland, inspired by his father, a self-taught folk accordion player. He later turned to classical playing, learning under the pioneer of the instrument Mogens Ellegaard at the Royal Danish Academy of Music.

The classical accordion Crabb plays is distinct from the traditional version of the instrument, with the main difference lying in the left-hand side. “On a traditional accordion, the piano keyboard plays the melody and the left hand, with the small buttons, plays the accompaniment,” Crabb explains. “That’s based on chords, so you press one button, you can get a major chord or a minor chord; the main difference with the classical accordion is that with the left hand, you can change the keyboard.

“This means you can do anything a two-manual organist could do, which opens up a completely different repertoire because you’re not bound by the pre-fixed major, minor and dominant seventh chords – you have this full range of single tones on both sides of the instrument.” Crabb cites composers such as Thomas Adès and Brett Dean as being particularly inventive with the instrument. When placed within an orchestra, the instrument brings a unique sonic quality, Crabb adds. “The accordion playing

While the origins of the classical accordion date back to at least 1829, Crabb says the instrument started to become standardised in the 1950s. An early work to make use of the accordion was Tchaikovsky’s orchestral suite; Crabb also cites Paul Hindemith’s Kammermusik No.5 as a favourite.

“He used the accordion fantastically well in his fifth. Every time I play that, you just have to think, ‘That was written almost 100 years ago’ – it’s just incredible music and use of the instrument.” Crabb pinpoints 1958 as a landmark moment, when a piece was penned for Mogens Ellegaard, who went on to pioneer instruction of the instrument at the Royal Danish Academy of Music and would become known as the “father of classical accordion”.

Crabb says, since that time, playing technique has developed significantly and the relatively young instrument continues to surprise. “The technique of playing the accordion has evolved over the past 50 years … [but] we don’t have anything near the quality of repertoire that the other standard classical instruments have – so pushing the boundaries of musical expression and the use of the instrument is really exciting.”

with the violins or the accordion doubling with trombone creates this almost eerie, kind of unknown sound,” he says.

“It’s one of those instruments that creates a brandnew colour; there’s such fertile land, and a few leading composers have that kind of palette anyway, so when you hand them an instrument which in itself is an orchestra, all of these colours are infinite.”

Martín agrees the classical accordion presents incredibly exciting possibilities for composers. “The accordion is almost an orchestra by itself; similar to the piano, you can play a complete symphony on an accordion, and it will sound amazing.”

or many, mention of the recorder may conjure flashbacks to primary school music class – an association that recorder virtuoso Genevieve Lacey’s playing swiftly dismantles. Working across everything from Baroque repertoire to 21st-century works, Lacey says her instrument –which has a history dating back to the Middle Ages – can evoke some astonishing sounds.

“For a lot of listeners, the sound of the recorder immediately transports listeners to bird song, to ideas of Arcadia, to times that are perhaps nostalgic, certainly idyllic and beautiful,” she says. “Contemporary composers have also discovered that it sounds pretty stunning when it’s paired with electronics, and it can turn into a magical palette of sounds.

“It’s beautiful playing in that sound world with an apparently humble, simple instrument, suddenly gaining a key to a whole universe of sounds that are quite unexpected.”

Martín adds that, while a recorder is these days not an uncommon inclusion within an orchestra, people are often astounded to hear what the instrument can do. “I think what the recorder brings to an audience is surprise,” he says. “I enjoy seeing the fascination in the audience, seeing the impossibility of some of the things performers like Genevieve can do on stage.”

Lacey says she always relishes the chance to play with an orchestra. “It’s different from any other kind of musical experience. Playing chamber music is joyful and glorious because it's so malleable and everything can happen in an amazingly spontaneous, almost improvised way,” she says.

“Playing with an orchestra is not like that – it’s a massive group of people, and yet, within this flocking, swarming mass of people and sounds, there’s such room for tiny, exquisite nuance.”

A memorable MSO performance for Lacey was shortly after lockdown lifted in Melbourne, performing Hollis Taylor’s Absolute Bird “It’s inspired by the complete virtuosity of butcher birds; I’m paired with beautiful field recordings and I’m often in duet with the birds themselves,” explains Lacey. “Those calls and answers and the way that those creatures make music is traced through the orchestra.

“Playing that so soon after that long period where we could really only travel in our imagination was very special.”

For a lot of listeners, the sound of the recorder immediately transports listeners to bird son g, to ideas of Arcadia...

For Martín, an unforgettable moment with a remarkable instrument was working with yidaki/didgeridoo player William Barton in Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO’s Baparripna; an MSO commission and Martín’s first outing conducting the orchestra. “When we met, [Barton] started blowing into the didgeridoo and made these incredible sounds. I had to stop the rehearsal and say, ‘Wow. This is amazing.’ I was really captivated from the first second.”

Another work featuring Barton, Earth Sky, is slated to be performed by the MSO in the Ryman Healthcare Winter Gala: Carmina Burana later this year. While Martín has already had the pleasure of working with many unique instruments, he says there are still many more on his list – so perhaps MSO audiences should stay tuned.

“I’ve never worked with a harmonica, which I find a fascinating instrument; I’ve never worked with the Spanish castanets – and there are composers that have written concertos for castanets, believe it or not. I’ve also never worked with an alpine horn, from the Swiss mountains; it has an extraordinary sound.”

Martín says the sense of “openness” of the MSO means anything is possible, and Crabb and Lacey agree they always feel at home when playing with the orchestra. “In a place like this, people are up for it,” says Crabb. “Melbourne’s really eclectic … which is great for an instrument like mine – I’ve always felt welcome.” ■

Ryman Healthcare Winter Gala: Carmina Burana, Thursday 4 July 2024, 7:30pm; Friday 5 July, 7:30pm; Saturday 6 July, 2:00pm, Hamer Hall .

An instrument with a rich history, the recorder is often associated with Baroque times.

“In terms of notated Western music, that’s definitely a golden age for the recorder; in the hands of great composers like Bach and Vivaldi, it was an instrument that was loved and used,” says Lacey. In orchestral settings, she says, the recorder has been re-embraced more recently.

“When modern orchestras started to grow, the contexts in which they played changed – the rooms got bigger and the instruments themselves changed; they became much more mechanised so that they could project the sound more evenly and powerfully. That’s when the modern flute really came to the fore and the recorder sort of stepped sideways; in fact, it was almost silent for some time and then rediscovered in the 20th century.” Contemporary composers and players like Lacey continue to explore what the instrument can do. “I love working with composers,” she says. “I love the chance to exchange sound stories and when a composer turns me into a living laboratory, basically.

Visualise the MSO, and seated musicians making small, precise movements probably come to mind. Behind the scenes, however, there is action aplenty, from running marathons to Brazilian samba dancing. Words: Patricia Maunder

Photography JAMES GEER

it takes all sorts of people to achieve the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s (MSO) vision of enriching lives through music. It also requires a whole lot of energy. Meet four of the MSO family’s most dynamic members: office staff for whom music is integral to the way they move and musicians who prefer getting active quietly. Either way, their insights about lives in motion reveal the surprising amount and diversity of physical activity happening off-stage.

S HANNON TOYNE Head of Marketing and Sales

S HANNON TOYNE Head of Marketing and Sales

I’ve always been involved in the arts, which is why I love working with the MSO. As well as playing flute throughout school, I danced, starting jazz and tap from age five. Tap was my love for 20 years; I really liked the rhythms and beats I could make with my feet. When I was working at The Australian Ballet, before joining the MSO in 2021, I really wanted to get back into performing so I decided to try Brazilian samba.

It’s different to ballroom samba. Think of Rio de Janeiro’s Carnival with lots of feathers, colour and fun. When I hear the beats and rhythms I can’t not respond through movement; my hips and feet want to do their thing! I went from casual classes to courses to performing with a dance school, and I’m now with a company that performs all over Melbourne at weddings and events. I have such a sense of joy while performing. We’re often a surprise and I love seeing the look on people’s faces and their reactions to our shows. It’s my creative outlet.

I’m an avid pickleball player, a certified fitness and boxing instructor and in 2021 entered bodybuilding competitions. I couldn’t imagine my life without moving my body to music!

W ILLIAM CLARK Viola

I was such a serious, non-moving kind of kid I would wag school sports days and practise viola instead. I had to do some sport though, and played hockey until a music career came calling; [because I worried about] a hockey ball hitting my hand and ending it all.

I did a little running instead, but during COVID lockdowns it became an escape. Rachael Tobin, the MSO’s Associate Principal Cellist, suggested an occasional run together, which progressed to five times a week, then the Melbourne Marathon. My best time is three hours and three minutes, which I’m happy with, but I need three hours to qualify for my big goal, the Boston Marathon.

I usually run four or five times a week, even if it’s just five kilometres with my dogs. On tour I like getting up early for a run; it’s such an easy way to experience a place. I used to listen to music while running – mainly upbeat pop songs to avoid anything work-related – but not anymore. I relish the time of silence, because when your job is music it’s in your life constantly.

I need to be fit because playing in an orchestra is a physical job that can be taxing on the body. Violas are heavy and cumbersome, and I play up to seven hours a day, so posture and core strength are vital. In recent years, preparing people for this career has included a greater emphasis on avoiding injuries and catching them early. So I do five minutes of stretches to warm up before hours of playing, and I am conscious of anything that doesn’t feel one hundred per cent. I will stretch or rest, because a niggle can turn into something scary.

“I need to be fit because playing in an orchestra is a physical job that can be taxing on the body.”

Ever since I was young, everything I’ve done has involved music. I did ballet from age five before taking up the violin a few years later, and was the concertmaster for my high-school and university orchestras in the Philippines. I also like singing – so I avoid listening to karaoke kind of songs in the office so I don’t burst out singing!

I grew up listening to my father’s jazz favourites. George Gershwin was on high rotation, so the MSO’s 2019 Gershwin Reimagined concert brought back great childhood memories. As did the orchestra’s recent Olivia Newton-John concert, Hopelessly Devoted, because I watched her films Grease and Xanadu with my mum.

I’ve been a big fan of K-pop – Korean pop music – for years, especially bands like SHINee, BTS, Seventeen, and TXT (Tomorrow X Together). I haven’t seen any of them live, but if they ever announce a tour here, I’m definitely lining up for tickets. I’m also learning Korean because I got bored during the pandemic. I listen to K-pop and watch Korean dramas so much and thought I may as well learn the language so I don’t need subtitles!

In 2022, I started doing dance classes so I could learn K-pop choreography. I missed dancing, and decided I would do that and other modern styles rather than go back to ballet. I also got into hip-hop and R&B music and choreography through the dance studio I go to, and met my partner and friends there. We do the performance courses that end with a showcase, and sometimes film dance videos that we post on Instagram. Eventually I would like to get good enough to join a crew and compete and perform more often. Music and dance is my life now!

“ I also got into hip-hop and R&B music and choreography through the dance studio I go to. ”

A NDREW MACLEOD

Principal Piccolo

I was introduced to yoga soon after joining the MSO as Principal Piccolo in 2003. My partner was undertaking yoga teacher training and practiced teaching yoga to myself and two MSO violin colleagues. I was amazed by the profound physical and mental benefits gained from practicing yoga.

Most people associate yoga with the physical poses or asanas (a word from Sanskrit, a language associated with yoga). Asanas are a systematic combination of integrated poses that strengthen and stretch the entire body. Playing in an orchestra involves sitting for long periods of time. In rehearsal breaks, I often do seated versions of asanas, including Ardha Matsyendrasana, which is a spinal twist, and I can frequently be found in a quiet corner of the green room backstage doing Uttanasana (a standing forward fold). One of the fundamental aspects of yoga is that each pose has a counterpose to bring balance to the body and breath. As the flute and piccolo are held to the right above the shoulders, after 40 years of playing, I am frequently grateful to the science of yoga for its ability to address this imbalance. Pranayama, the breathing practices, are an important part of any yoga practice to focus and quieten the mind. This breath awareness has been helpful in my flute playing and in focussing my mind prior to performances.

In 2021, I completed my level 1 yoga teacher training and practised leading classes with my dear MSO flute colleagues. I also talked about yoga and led a yoga breathing practice on MSO’s Up Late with Ben Northey on YouTube. After that experience, Ben has become a devoted yogi and now travels everywhere with his yoga mat! ■

“Pranayama, the breathing practices, are an important part of any yoga practice to focus and quieten the mind. This breath awareness has been helpful in my flute playing and in focussing my mind prior to performances.”

For Australian LGBTIQA+ rights activist and academic Rodney Croome, a childhood appreciation of Tchaikovsky’s music has transformed into deeper reflection. With upcoming MSO performances exploring love as part of the Great Stories program, he implores for the realms of classical music and beyond to integrate LGBTIQA+ stories into past, present and future.

In my adolescence, I was besotted with Tchaikovsky’s music, especially his sixth symphony. As I listened to the victorious third movement, I imagined the composer happily bowing to the raucous applause of a Russian audience.

Tchaikovsky’s works reminded his compatriots of the first time they saw swans on a misty lake, of their first true love, and, through his nationalistic pieces, of the time they still trusted their fathers, the Tsar and God. In the oddly accelerated triumphalism of this movement, his public shows its appreciation.

But in my youthful daydream, there were gallows at the edge of the stage. They stood for the melancholy destination of the symphony in its final, fourth movement, as well as Tchaikovsky’s death not long after the symphony debuted, possibly by suicide because of the revelation of his homosexuality to the Russian authorities. For me, the third movement was a victory lap for the already defeated. Did I imagine that scene because I was gay, closeted, and needed to read Tchaikovsky’s sexual despair in the music I was listening to? Or was his despair something Tchaikovsky wrote into the symphony for anyone with ears to hear?

I subsequently asked myself the same questions regarding pieces by other composers like Britten, Copland and Handel. Then, at some point, I realised the problem wasn’t the elusiveness of such hints. It is the need to rely on hints at all.

The problem is the absence in classical opera, art song, ballet, or instrumental pieces of the stories of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex, queer and asexual (LGBTIQA+) people proudly living, surviving and thriving. Does it really matter what stories composers or librettists tell, so long as they tell them well? Clearly, for teenage me, it mattered a great deal, and it still does. To say our presence in classical music is irrelevant is to effectively erase us from an entire field of artistic endeavour. That reinforces the myth that we are, at best, ephemeral to the human experience and, at worst, threatening intruders. It diminishes our humanity.

That is why there is a part of me, and many LGBTIQA+ people, that still needs to hear our lives and loves reflected in classical music. Some people respond to the problem of our invisibility by focussing on the higher profile of today’s LGBTIQA+ classical musicians, or the vocal support for our equality from some high-profile nonLGBTIQA+ performers. Others point to the growing visibility of LGBTIQA+ lives and rights in contemporary popular music. This

began in the 1980s with the New Romantics and is now blooming across genres from hip-hop to country. The most obvious example for many Australians was the way Macklemore’s Same Love became the anthem of the Marriage Equality Yes campaign. As welcome as all this is, the impression it creates is that the representation of LGBTIQA+ love in music is only forty years old. It still doesn’t address the many ways classical music can express who we are.

Another response might be to do a queer Bridgerton on the classical repertoire, re-interpreting it to include the LGBTIQA+ characters and stories that homophobia and transphobia deliberately wrote out in centuries past. That would be a strong statement, just as it is to cast black actors as Georgian aristocrats. But it would not fill the gap. It would not fully represent our lives and loves as they were and are.

The only real solution is the commissioning of more new work that speaks to the breadth of the experience of LGBTIQA+ people: the dilemmas of coming out, the joys of love, the horrors of persecution, the achievement of equality and everything in between.

There is some exceptional contemporary work that represents us, but it is still seen as just that, exceptional, and not an integral and permanent part of classical music in the way heterosexual and cisgender narratives are. I urge our allies in classical music, those who have so vigorously championed our equality in the wider world, to redirect more of their advocacy back into the art form. I urge them to persuade funders, programmers, directors, and creators of classical music to consider the value of classical music as a whole to give LGBTIQA+ lives and loves a higher-profile place.

LGBTIQA+ visibility in future classical repertoire will be especially important in attracting and retaining younger audiences. When I listen to Tchaikovsky today I am still tempted to hear a celebration of same-sex love, as well as despair over the prejudice that love draws. But I also hear hope that there will be a time when these joys and fears can be heard more honestly and consistently. I’m optimistic that time is upon us.

Jaime conducts Romeo & Juliet, 18 July, 7:30pm, 20 July 2024, 7:30pm, Hamer Hall.

The views and opinions expressed in this Essay are those of the author.

1. Andrew Macleod uses yoga and powerlifting to assist his movement as principal artist in this instrument (7)

4. This superstar sings with Roderick Williams in an intimate evening of music in support of the MSO’s Artistic Program, Siobhan ... (5)

7. See 18dn.

8. Elena Kats-Chernin’s Mythic and Sibelius’ Symphony No.7 are on the program with this composer’s epic Requiem (5)

9. Great mind, such as that of Mozart, Bach and Beethoven (6)

12.Violist who curated a program of chamber works for the orchestra, Gabrielle ... (8)

15. Katy Abbott’s award-winning series, Hidden ... (8)

17. Jayson Gillham performs the Beethoven Piano ... No.21 “Waldstein” (6)

18. Direction taken from conductor Benjamin? (5)

21. Joyfulness and exhilaration (7)

22. Cultural capital of Japan (5)

23. Miranda, Is It You? and Nocturne are works created by this composer who also shared an Oscar for his score to the 1939 Western, Stagecoach (7)

1. Grieg’s evergreen piece is a treat for small children in the Jams for Juniors program (4,4)

2. Gillham closes his performance with Op.10 Études by Frédéric ... (6)

3. Is the proprietor of (4)

4. Crashing waves at the beach (4)

5. She’s behind the scenes at the box office, Marta ... (7)

6. Donate, as you might to the vision of Suzanne Dembo and Barry Mowszowski (4)

10. Ancient rulers of Persia (5)

11. Composer, Philip ... (5)

13. System of symbols through which music is written down (8)

14. The high singing voice of a bel canto performer (7)

16. The enthusiastic shout from the audience at the end of a performance (6)

18. & 7ac. Head of Learning and Engagement with the MSO (4,7)

19. 18dn views Beethoven as ‘the ... artist’ (4)

20. St Matthew Passion composer, JS ... (4)

Create words of four letters or more using the given letters once only, but always including the middle letter. Do not use proper names or plurals ending with S. See if you can find the nine-letter word using all the letters.

Answers on page 50 Compiled by the MSO’s Keith Clancy

1 This popular work for soloists, chorus and large orchestra was premiered in Frankfurt, Germany to immediate acclaim in 1937. It sets secular poems in medieval Latin. What is its name?

2 Australian composer Katy Abbott has written a piece for children based on the memoir Mao’s Last Dancer by Li Cunxin. What’s the name of the piece?

3 Brahms delayed writing his first symphony for decades and a statement attributed to him tells us why: “I’ll never write a symphony, you have no idea what it feels like … to hear the footsteps of a giant behind one”. What is the name of the “giant” being referred to here?

4 This “dramatic poem” by Lord Byron inspired music by two 19th-Century composers featured in the MSO 2024 season, Tchaikovsky and Robert Schumann. What is its name?

5 The opening motto of this famous symphony was associated during

6

World War II with the phrase “V for Victory”. Why?

Much-loved soprano Siobhan Stagg returns to the MSO stage this year to sing the soprano part in which French setting of the Latin mass for the dead?