StrokeGenius of

ENTER THE MUSICAL WORLD OF AUSTRALIA’S YOUNG VIOLIN SUPERSTAR CHRISTIAN LI

ORCHESTRA ROCK

The classical callings of Australian rock band Birds of Tokyo

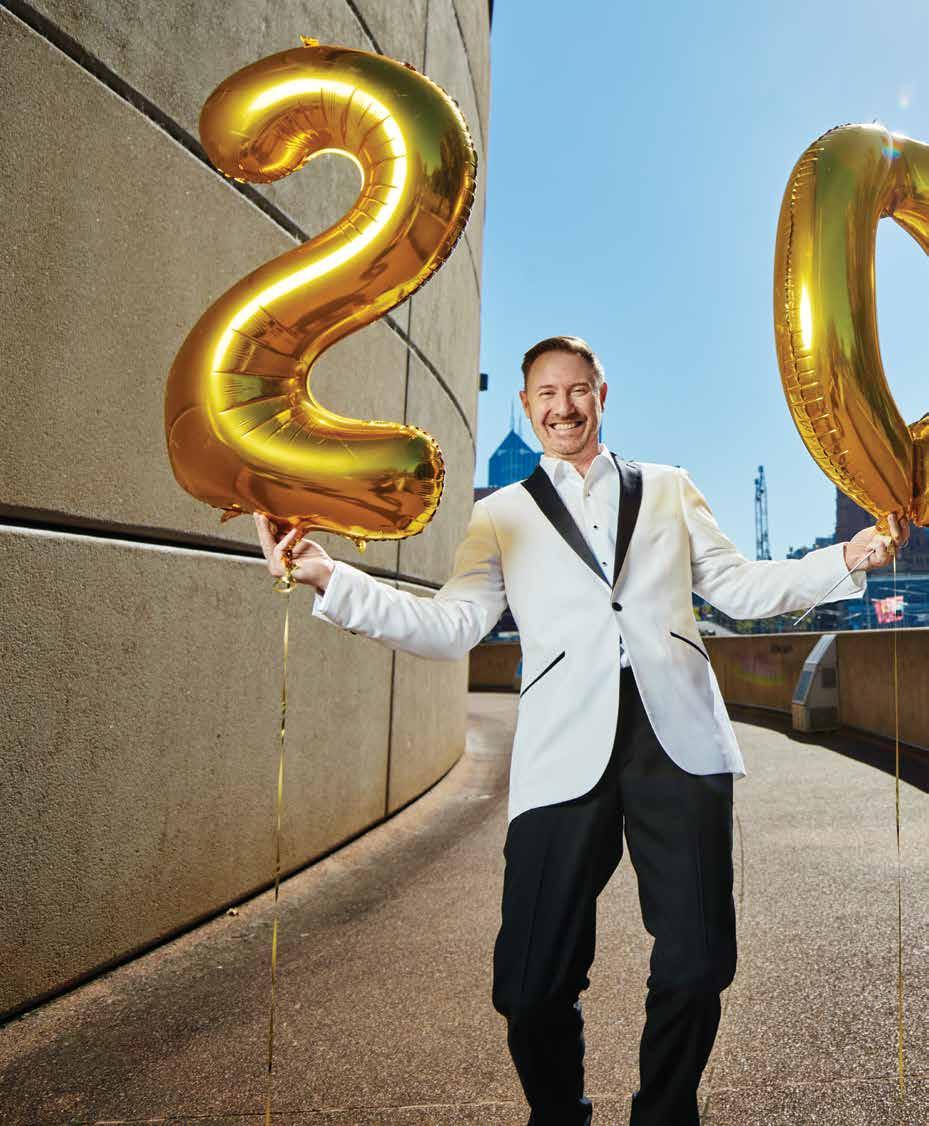

THE BIG 2-0

Celebrating three MSO musical milestones

ENTER THE MUSICAL WORLD OF AUSTRALIA’S YOUNG VIOLIN SUPERSTAR CHRISTIAN LI

The classical callings of Australian rock band Birds of Tokyo

THE BIG 2-0

Celebrating three MSO musical milestones

At Ryman, we believe the measure of a full life is one that gets richer with age. A life where you can appreciate the little things.

Rediscover lost passions and plunge headfirst into new ones.

Surround yourself with new people, old friends and close family.

Live with opportunities and experiences at your doorstep.

That’s why we’re creating communities that challenge the expectations of ageing, while bringing joy and meaning to every moment.

rymanhealthcare.com.au

EBBIE & PREMILA Ryman Residents16 Class of His Own

Off the back of his new album, MSO 2023 Young Artist in Association

Christian Li opens up about life as a 15-year-old violin superstar

22 Change of Tune

Australian band Birds of Tokyo explain why there is nothing like sharing a stage with an orchestra

28 State of Belief

Discover how the integration of faith in classical music has influenced two prominent composers

32 The Big 2-0

Celebrate 20 noteworthy years with the MSO

38 Staging Success

Uncover what it takes to orchestrate an international tour and cross-cultural partnership

What was the story behind the world’s first-known psychedelic symphony?

46 Essay: Look at Moi Australian comedian Wendy Harmer charts the rise and empowerment of the Australian female comedian

Wendy Harmer is one of Australia’s most versatile entertainers – broadcaster, author, journalist and stage performer. As a stand-up comedian she has performed in Melbourne, Edinburgh, Montreal and Glasgow Mayfest Comedy Festivals, in London’s West End and the Sydney Theatre Company. For 11 years she led Sydney radio station 2Day FM’s top-rating Breakfast Show and was the co-host of ABC’s 702 Sydney morning show from 2016-2021. She has hosted, written and appeared in a variety of TV shows including ABC’s The Big Gig. It makes Wendy the perfect author for this issue’s essay (page 46), where you can read her thoughts on the rise of female comedians in Australia.

Kristoffer Paulsen is a Melbourne-based photographer. With a diverse practice, he divides his time between editorial clients such as The New York Times, Swill Mag, Good Weekend and London’s The Times, and a swathe of commercial clients shooting everything from whiskey, hotels, poultry, vintage synthesizers, architecture and food. Kristoffer lends his diverse creative talent to this issue’s The Big 2-0 photo shoot. View Kristoffer’s work on page 32.

Katie Cunningham is a freelance writer covering culture and lifestyle topics. Her weekly column Three Things for The Guardian sees her interviewing prominent Australians about objects that inspire them. Her work has appeared in the Sydney Morning Herald, ABC, Crikey, VICE, Rolling Stone Australia and Qantas Magazine. Read Katie’s interview with Birds of Tokyo’s founding member Adam Spark on page 22, where he discusses the band’s upcoming symphony orchestra tour Birdsongs.

Sue Cadzow is a freelance illustrator, designer and digital artist from Sydney, who loves to create vintage-style artwork with modern twist. Her love of vintage science fiction novels and movies, and cartoons like The Jetsons, led to an interest in retro-futurism and an appreciation of the irony of creating vintage-style artwork using modern digital media. Sue’s unique illustration style can be found alongside this issue’s essay on page 47.

Sarah Vercoe is a Queensland-based freelance writer and National Geographic award-winning photographer. Over the past decade she’s written about everything from the neuroscience of trauma to travel for publications such as MiNDFOOD, Luxury Travel, and WellBeing. In this issue she unveils what it takes to bring together the MSO’s 2023 tour to Yogyakarta, Indonesia (page 38) and the unique partnership behind it.

It is our pleasure to share this latest edition of Encore magazine with you. After an extraordinary first half of the year, we look ahead with excitement to the remainder of 2023.

Our writers shine a spotlight on teenage sensation Christian Li, the MSO’s Young Artist in Association, as well as rock band Birds of Tokyo, who are collaborating again with the Orchestra this year.

In celebration of musical milestones, 2023 marks several 20-year anniversaries – 20 years of Benjamin Northey conducting the MSO, 20 years of Emirates as the MSO’s Principal Partner, and 20 years of the Cybec Foundation - funded programs and positions. We’re thrilled to acknowledge these achievements and look forward to many more years of collaboration.

We also look at the interesting origins of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique – the world’s first known psychedelic symphony – and uncover what it takes to orchestrate the MSO’s Indonesian tour and cross-cultural partnership.

We hope that you enjoy reading this fourth edition of Encore and look forward to seeing you in the concert hall for many more beautiful performances.

Sophie Galaise, Managing Director, MSO

The MSO respectfully acknowledges the people of the Eastern Kulin Nations as the Traditional Custodians of the unceded land on which we work. We acknowledge Elders past, present and emerging and honour the world’s oldest continuing music practice.

We are proud to collaborate with The Torch to present this beautiful artwork to accompany our Acknowledgement of Country. The Torch is a not-for-profit organisation that provides art, cultural and arts industry support to Indigenous offenders and exoffenders in Victoria. This work, called Bunjil Dreaming, was created by Taungurung/ Boon Wurrung woman Stacey, who says of the work: “Bunjil is the Creator. This is a spirit that physically takes the form of a wedge-tailed eagle and is a star in the sky at night.” Stacey has traditional connections to the Melbourne region. In 2013, she started working at the Koorie Heritage Trust where she met an Elder who helped her with her family connections. “The Elder told me that I am Taungurung/Boon Wurrung. Since that day, I don’t paint dots anymore. My inspiration is the beautiful designs and patterns from traditional artefacts of my ancestors. Painting diamonds is healing for me.”

Accessible, affordable, tech-enabled philanthropy at your fingertips. Anytime. Any place.

Anyone.

In our world, philanthropy starts with just $5000. Our future needs you. Let’s talk.

www.eqt.com.au/ecf

THE MOMENT

“Sadie (The Cleaning Lady)” – you can probably hear the catchy tune immediately. You may even recall its black-and-white music video, where dancers dressed as maids bounce around a young, suited-up Johnny Farnham. The 1967 number-one single was just the beginning of a stint of hit songs and albums by Farnham that spanned the following five decades, during which Johnny became John and his clean-cut 1960s hairstyle grew into an 80s mullet. Fast forward to now – Farnham has seen media coverage for his recent health battles. But more positively, his legacy lives on as his music is discovered by a new generation of Farnsy fans. Music aficionados and vocal coaches globally have made “reaction videos”, wherein they record and upload their initial reactions to the compelling performances and unique sound that earned Farnham his nickname, “The Voice”. A common theme to these videos: Farnham’s 1989 concert with the MSO. Backed by a full orchestra, he performed 17 songs to a packed crowd at Melbourne’s National Tennis Centre (now known as Rod Laver Arena). Social media users expressed the emotional impact of listening to the iconic Australian artist belt out his classic ballad You’re the Voice and cover of The Beatles’ Help!; for many, the first time hearing his remarkable vocals.

From “I can’t wipe a grin off my face” and “it gives me goosebumps”, to the appreciation of the Orchestra – “that makes the song so much more powerful” – the power of Farnham’s live performance with the MSO continues to impress new audiences around the world.

Our Associate Principal Flute takes on the Proust Questionnaire… and recalls pre-concert hall days when her stage was a paddock and her audience a herd of cows.

What is your idea of perfect happiness? Being outside, on a sunny day, in my garden, the bush or at the beach. What is your greatest fear? Being late for a concert, especially if it’s being broadcast live-to-air. Or getting to work, opening my flute case and having no flute inside.

This happened to me in high school and I’ll never forget it. Which living person do you most admire? My friend John, who just turned 94. Every morning, he goes to the dog park to walk and meet his two- and four-legged friends. He has such a positive outlook on life – and he taught me how to use a drill!

What is your greatest extravagance? I wish I was more extravagant when it comes to going on holidays.

What is your current state of mind? Calm, because I did a yoga session this morning.

What do you consider the most overrated virtue?

Righteousness.

On what occasion do you lie? Sometimes you need to lie to protect others. My father had dementia and lying about certain situations made his world happier.

What is the quality you most like in a person?

Generosity of spirit and good humour.

Which words or phrases do you most overuse?

Earth - it’s my Wordle and Octordle word!

What or who is the greatest love of your life?

My two daughters.

When and where were you happiest? When I was a young girl, sitting in the middle of a paddock, singing and playing my ukulele to a herd of milking cows as my entranced audience. Which talent would you most like to have? To be able to speak many languages.

If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be? I don’t focus on the negatives, I try to always promote self-love.

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

Having my two daughters.

If you were to be reincarnated as a person or a thing, what would it be? In my next life, I would like to be a talented soprano and sing all the wonderful repertoires and wear all the amazing gowns and costumes.

Where would you most like to live? On a boat on Rottnest Island in Western Australia.

What is your most treasured possession? My flute.

What is your most marked characteristic? Easy-going and sociable.

What do you most value in your friends? Someone who sticks by you in good times and bad.

What other instrument do you wish you could play?

Piano. I would love to play the Chopin Nocturnes.

Who are your heroes in real life? Rosie Batty. She displays such strength and determination in spreading awareness.

What is it that you most dislike? People who spread negativity.

How would you like to die? In my sleep.

What is your motto? My family motto is ‘Be caring, sharing and respectful’.

Wendy Clarke will curate the MSO Chamber Performance French Delights on Sunday 29 October at Iwaki Auditorium.

What is your greatest fear? Being late for a concert, especially if it’s being broadcast live-to-air.

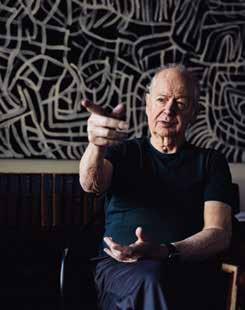

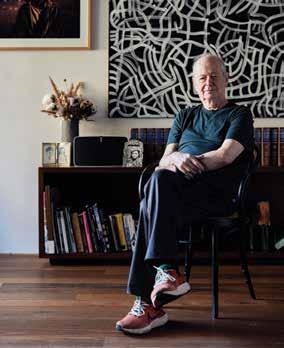

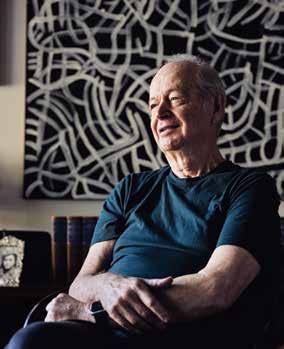

MSO Patron Bob Weis shares how he worked with composer Elena Kats-Chernin to recognise his mother’s life through music.

When asked why commissioning new Australian music is paramount, MSO Patron Bob Weis believes “it makes us sensitive to the bigger issues and the smaller issues – or both. It’s an expression of our inner selves that takes us beyond the ordinary.”

Weis and his family are lifelong supporters of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, inspired by their mother’s devotion to the arts. The late Sara Weis, a Polish war-time survivor, was an avid music-lover. “She was an MSO subscriber who always sat in the same seat in the stalls. Music was like oxygen to her,” says Weis.

To honour Sara Weis’s life, nine members of the Weis family joined together to support a new commission for acclaimed Australian composer Elena Kats-Chernin, a double concerto for violin and cello titled Serenka

“Serenka was my mother’s pet name when she was a child,” says Weis. “She had an extraordinary life and we wanted to remember her through music.”

Sara Weis was born and raised as an only child in South East Poland. A teenager during the Nazi invasion, she survived a Jewish massacre that claimed her parents’ lives thanks to the intervention of a local woman who helped Weis disguise herself, escape the village and hide in a haystack. She was quickly picked up by a group of anti-Nazi partisan women looking for people with medical skills. Sara Weis’s uncle was a chemist; she knew how to prepare

medicines. Within hours she was assisting in emergency medical operations. “That’s incredible for a 16-year-old,” says Weis. “This was only a few hundred metres from where her family had been shot and buried.”

Sara Weis eventually married and left Poland. Bob Weis was born in Munich in 1947 before the family migrated as refugees to Melbourne. There, Sara Weis built a happy home and family life, becoming the principal of a Jewish kindergarten and, in later life, a beloved guide at the National Gallery of Victoria. “She said she measured her life in spoonfuls of kindness,” Weis recalls. “She was an inspiration to all who knew her.” A distinguished film producer, Weis has spent hours with Kats-Chernin telling his mother’s story. The composer would respond by playing piano sketches from different moods representing different aspects of his mother’s life. “Elena would say, ‘these are the war years’, and play something, and we would give our feedback,” says Weis. “My 10-year-old grandson suggested having a choir and she said that would be interesting. It was impressive to see Elena engage with everyone in the family, from the youngest to the oldest.”

Weis says he is an “unabashed fan” of the composer and, as a Patron, he now feels even closer to the MSO family. “They have wrapped their arms around me during this whole commission –it’s been wonderful.” ■

Highlights of what’s coming up in the second half of 2023.

British violinist Jack Liebeck makes his Hamer Hall return to perform the Bruch Violin Concerto, a piece voted ABC Classic listeners’ #4 concerto. Jaime Martín conducts, with the Bruch featuring alongside Dvořák’s Fifth Symphony and a new commission by Paul Grabowsky AO (18 Nov only). A perfect program for the final Friday morning and Saturday afternoon performances of the season.

Jaime Martín conducts Bruch and Dvořák, 17 & 18 November, Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne.

Following five-star (Limelight) and four-star (The Age) reviews from its world premiere performance with the MSO in 2019, Eumeralla: a war requiem for peace, returns to the Hamer Hall stage.

Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO composed this piece after visiting the battlefield of the Eumeralla Resistance War (1840 – 1863), in Gunditjmara country in south-western Victoria.

Experience the sublime beauty of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra in full force at the Melbourne Town Hall as we present an enchanting evening showcasing Camille Saint-Saëns’ aweinspiring Organ Symphony. Join us for a mesmerising performance as the MSO brings this masterpiece to life. Immerse yourself in the grandeur and majesty of the Melbourne Town Hall’s magnificent setting, perfectly suited to the grandeur of Saint-Saëns’ orchestral masterpiece.

From the thunderous opening chords to the delicate interplay of the organ and orchestra, be transported to a realm of sheer musical brilliance. Star cellistturned-conductor, Umberto Clerici returns to lead the work, as well as two more favourites – Ravel’s Mother Goose Suite and Debussy’s Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune. Saint-Saëns’ Organ Symphony, Thursday 10 August, 7.30pm, Melbourne Town Hall and Friday 11 August, 7.30pm. Robert Blackwood Hall, Monash.

This requiem for peace is sung entirely in the ancient dialects of the Gunditjmara people and designed for non-Indigenous Australians to sing along-side Indigenous brothers and sisters. Experience this momentous and deeply moving work this October. Eumeralla, a war requiem for peace, Saturday 14 October, 7.30pm, Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne.

After three sold out shows and rave reviews in 2019, the wonderful Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra (JALCO) with Wynton Marsalis returns to the Hamer Hall stage with the MSO this August.

The one and only Wynton Marsalis, a nine-time GRAMMY® Award-winning trumpeter, is one of the world’s most popular jazz musicians, receiving countless accolades throughout an illustrious career traversing both jazz and classical genres.

All Rise was composed by Wynton Marsalis in 1999 and is a genre-bending, exhilarating jazz symphony of massive scale. Don’t miss this momentous work. All Rise: Jazz at Lincoln Center with Wynton Marsalis and the MSO, Friday 25 and Saturday 26 August, 7.30pm, Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall.

2023 marks Sergei Rachmaninov’s 150th anniversary, and the MSO are celebrating his works throughout the season. Famously feared by pianists worldwide due to its difficulty, his Piano Concerto No.3 will be tackled by the extraordinary Joyce Yang this September.

Principal Guest Conductor Xian Zhang returns to the MSO for this lyrical and nostalgic program, which also includes Tchaikovsky’s Eugene Onegin: Polonaise and Smetana’s Má vlast

Kickstart your Monday by skipping peak hour for an inspiring and uplifting start to the week. The Quick Fix at Half Six concert is one hour with no intervals, and features the Rachmaninov and Smetana works only.

▪ Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov and Smetana, Friday 15 and Saturday 16 September, 7.30pm, Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall.

▪ Quick Fix at Half Six, Monday 18 September, 6.30pm, Arts Centre

Melbourne, Hamer Hall. Quick Fix at Half Six is proudly presented by TarraWarra Estate.

MSO through Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s dramatic interpretation of The Arabian Nights, in his glorious Scheherazade This exotic and colourful symphonic suite will soar like the chronicles of old.

The program also features Tchaikovsky’s famous First Piano Concerto, performed by the electrifying Haochen Zhang – gold medal winner at the Thirteenth Van Cliburn International Piano Competition.

For an inspiring and uplifting start to the week, Scheherazade is also being performed as part of the Quick Fix at Half Six series – a popular new concert format of one hour with no interval.

For a spectacular finale to the season, Chief Conductor Jaime Martín leads the

The Ryman Healthcare Spring Gala: Symphonic Tales, proudly presented by MSO Premier Partners Ryman Healthcare, on Thursday 9 and Saturday 11 November, 7.30pm, Hamer Hall, Arts Centre Melbourne.

As the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s 2023 Young Artist in Association, violinist Christian Li showcases talent beyond his 15 years. Stephanie Bunbury speaks to Australia’s rising musical superstar.

Photography ALBERT COMPER

Photography ALBERT COMPER

hristian Li started learning the violin when he was five. Ten years on, he can’t remember the first classical piece he ever heard but recalls the first violin piece he passionately listened to: Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, which now sits at the heart of his second album Discovering Mendelssohn. “My parents started me on piano and violin when I was around five-years-old as a hobby, but I gravitated towards the violin because I found it easier to learn and express my feelings. I was also captivated by the lyrical sound of the violin,” he says. “I remember my first violin teacher telling my mum I’m special, so we took it seriously. Looking back, I’d say it was their recognition and encouragement that gradually made me enjoy practising and performing. Then I fell in love with classical music.”

Two years later, he started working with Head of Violin at the Australian National Academy of Music (ANAM) Dr Robin Wilson. “He wasn’t very advanced at that stage,” Wilson recalls. “He was playing little Suzuki pieces [from the recognised Suzuki method for teaching music to children]. What I noticed, however, was a very strong, genuine and what seemed to be innate desire to communicate through his instrument. That was very unusual for such a young child. He was somehow just feeling the intrinsic emotion in the music.”

Unlike many children, Li also had firm ideas of how each piece should be played. Wilson would suggest different phrasing or a hypothetical meaning behind a passage and this little boy would stand his ground. “He would have already thought about it and come up with his own way, or his own phrasing or idea of what that phrase actually meant and he would have practised it that way and felt very convinced about it. Which is really wonderful. You want someone to be their own musician. To have autonomy.”

Jump another three years from Wilson’s first encounter with Li, and the now 10-year-old is competing in the biennial Yehudi Menuhin International Competition for Young Violinists competition. With his rendition of Summer from Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and the newly commissioned Self in Mind by South Korean composer Jaehyuck Choi, Li became the competition’s youngest ever winner in the Junior Division, sharing top honours with 11-year-old Singaporean Chloe Chua.

Unsurprisingly, more milestones followed. At 12, Li became

the youngest classical artist to be signed with British record label Decca Classics. For his first album, he returned to the Four Seasons, recorded with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra, where he is now the Young Artist in Association. “When you look at the way he directs from the violin on the Four Seasons recording, it is amazing that someone of his age has the understanding of the music and the conviction to bring the music alive,” says the Orchestra’s Chief Conductor Jaime Martín. “He’s strong about it and it’s not something he has just learned. It’s something that comes from him.”

Li still loves Vivaldi’s masterwork, he says, although he thinks his current favourite in the composers’ pantheon is Tchaikovsky. “His music is very romantic, passionate and heartfelt.” But Li’s favourites change all the time. There is, of course, Mendelssohn; along with Sibelius, whose fiendishly tricky violin concerto he performed with the MSO in April. And then there is Mozart.

Mozart, famously, started composing at the age of five. There is always anxiety around young performers under pressure, but classical music has a history of prodigies. Mendelssohn wrote his officially recognised First Symphony when he was only 15, but he had already written 13 symphonies that are not counted. In September, Li will play Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 3, which Mozart wrote at 19, to audiences in Geelong and Melbourne. “I always wanted to perform Mozart’s concertos, because the age when he composed those concertos, he was very young,” says Li. “Similar to my age. I feel sometimes young artists can better capture his innocent spirit of the music.”

Li did not grow up in a musical household. His mother Katherine Liu emigrated from China and is a certified accountant. His father George Li is an electronics engineer. Their preferred listening, according to their son, is popular Chinese music. There is music in the family, however. Before the pandemic, they would go back to China every year to visit his mother’s parents. “My grandfather plays piano and accordion,” says Li. “I think he’s really talented and I might have gotten my talent from him.” It was in China that he won his first big prize: the Golden Beijing violin competition. That was in 2014; he was seven.

Inevitably, life for the Li family has increasingly had to fit around

“When you look at the way he directs from the violin on the Four Seasons recording, it is amazing that someone of his age has the understanding of the music and the conviction to bring the music alive.”

music. As a student at Scotch College, he was able to practise for two hours a day after school. “But on the weekends and term breaks when I had more free time I would practice more, like four to six hours. We just do it. I think everything fits quite well.”

Last year, he studied at The Juilliard School in New York, accompanied by his mother while his father stayed in Melbourne. Li also attended the Professional Children’s School where schoolwork was tailored to allow for more practice every day. “At the professional school, they support every student’s career and give them time off school and not much homework,” says Li. He will be similarly focused next year at the Menuhin school in Surrey, just outside London, where his regular teacher Robin Wilson has taken up a professorship.

His core curriculum in New York consisted of mathematics, English, biology and a drama elective. Another kind of performance, then? “I feel they’re a bit different, but it’s great to practise being

on stage,” he says. “It helps maintain your confidence – also it’s teamwork, interacting and improvising.” He and a couple of friends worked up a script where they created their own superheroes. “We had a competition for who was more powerful.” It ended with a fight: a typical teenage moment, by the sound of it.

Undoubtedly, parental support is essential. That said, a child musician must want to succeed independently. “Christian’s parents never wanted to force him to play the instrument against his will, but they were very willing to do whatever it took if he were going to play this instrument,” says Dr Wilson. “There is a very strong work ethic there and a lot of discipline behind what he does but really, the intensity comes from him. If he’s left alone in the house he is going to practise. He doesn’t need to be told.”

Li has said in various interviews he enjoys bike riding, reading Harry Potter and visiting the Science Museum in London between concerts, but five hours of practice a day doesn’t leave a lot of

“There is a very strong work ethic there, and a lot of discipline behind what he does but really, the intensity comes from him.”

time for other things. “Look, it’s a mistake to say that someone who does anything to a truly exceptional or elite level, can have a completely normal childhood, so of course there are sacrifices,” says Dr Wilson. “I would say spending time with other children is one thing that suffers. One reason why, for example, a specialist music school like Yehudi Menuhin is a wonderful place is that you’re around like-minded kids of your own age.”

“Well, right now I am very interested in composition,” says Li. “I took courses and I also have written some short piano pieces and sonatas on my laptop using music notation software. I’ll share them with my friends to find out what they think of them. I’ll even get my pianist friend (and ANAM alumnus) Laurence Matheson to play them.” He’s not sure where that will lead. “I think with composition you just have to try it as you go.”

And further down the line, says Dr Wilson, his advanced study will depend on what his artistic needs are. Especially given that he is clearly in his element on stage. Martín recalls Li walking on stage with the Swedish Philharmonia to play

Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto which he had played under Sir Andrew Davis with the MSO. He beamed out at the audience and they beamed back. “He has this kind of magnetic force with the audience, they love him from the moment he comes on the stage,” says Martín.

His purpose, says Li, is to draw people into his musical world. “To get someone who plays well at age 15: you can find that around the world,” says Martín. “But to find someone who at age 15 not only plays well but listens to the orchestra: he has a level of maturity that is remarkable, along with this refreshing talent. For people like me – and his teacher, his mum, everybody – to look at him is exciting, because you wonder where it will stop? He could do anything.” ■

Iconic Aussie band Birds of Tokyo are set to take the stage with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra come September.

From the rock stage to concert halls, Australian band Birds of Tokyo soar to higher heights and find new ground through their dynamic collaborations with world-class orchestras.

By Katie Cunningham

By Katie Cunningham

The way musician Adam Spark sees it, there’s nothing quite like the thrill and dynamism of collaborating and playing with an orchestra. “Honestly, I love watching people’s faces when we play with an orchestra. It's really cool when you’re in a room with 50 to 60 people on stage and a few thousand in the audience – it’s a whole lot of people having a big old string love-in. And horns, and percussion.”

At first glance, Spark might not seem like the most likely candidate to share a stage with a conductor and 40-piece classical ensemble. He is a founding member of Birds of Tokyo, a rock band more readily associated with sweat-soaked gigs and festival sets than they are the concert hall. Over their nearly two-decade career, the group has ticked off all the markers of mainstream music success, picking up ARIA Awards and releasing platinumselling albums. But Spark feels that the “cinema, drama and heartache” found in their brand of emotive, anthemic rock lends itself perfectly to an orchestra – which is what keeps bringing him back to it. “The band has always tilted in the direction of big and grand,” he says. “So it felt like a right fit.”

You might find their music in the rock category on Spotify, but Birds of Tokyo actually have a long history in the orchestral world. The band did their first live collaboration with a string ensemble in 2007, recorded with the London Symphony Orchestra for their 2010 self-titled album, and realised their dream of performing with a full orchestra in 2021 when they did a run of symphonic shows around the country – including one with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra at the Sidney Myer Music Bowl. “We wanted to create a big symphony for a long time,” Spark says. “When we did the first in the series of these shows a few years ago, it really worked. And it proved the concept.”

Those 2021 performances were such a hit that Birds of Tokyo have decided to do it all again this year. In September, Spark and bandmates will play three dates with the MSO at Hamer Hall as part of a national symphony orchestra tour called Birdsongs. It’s set to be their most ambitious live performance yet, and one the band has begun work on months in advance of the curtains coming up.

Translating rock music to the symphony orchestra takes a lot of work. First, Birds of Tokyo must determine which songs they want in the set list – usually a mix of their best-known hits and the deeper cuts they can get truly creative with. Then, every song is broken down and rebuilt with an orchestra in mind. That’s because Spark and his bandmates aren’t content to just add strings behind their back catalogue and call the job done – they want to hero the Orchestra and position it at the centre of the

songs, slotting themselves around the violinists, percussionists and double-bassists.

They believe the orchestra-first approach makes for more beautiful, three-dimensional music. And the band likes to make use of everything a 40-piece ensemble has to offer, in terms of what Spark describes as “colour, texture, heaviness” and even welldeployed moments of stillness. The vision is to deliver something truly cinematic. “We like taking the songs and converting them into mini film scores. So, rather than us playing the songs as they are, we prefer to strip them back to their core and rewrite the work as if it were a little Hans Zimmer piece,” Spark says.

To recreate each song, the band often put together mock versions with digital strings for a rough sketch of what they think

a track could become. They send those drafts over to Nicholas Buc – the conductor/arranger who worked with Birds of Tokyo for their 2021 shows, and is on board again this year – who then develops the ballpark ideas for the symphony stage. Buc and the band workshop from there, but Spark says they have a “simpatico” relationship that makes collaboration easy. “Nine times out of 10, everything we sent him came back as a thumbs up,” he says.

And Spark has ultimate faith in the orchestras he is handing his work over to. “We have so much trust in the fantastic conductors and Australia’s best players, so it allows you to relax … I mean, these people are way better musicians than we are – way better!” he laughs. “So we’re just trying to be the ones to not [mess] up their work, you know?”

Every song is broken down and rebuilt with an orchestra in mind.

While the whole of the collaboration process is highly rewarding, revisiting old songs can initially be daunting. It plunges Spark back into the situation in which he first wrote a song –remembering, say, the break-up or breakthrough it was penned about. As well as reliving that emotion, the process can make him critical of previous artistic choices, be it the sound of a bassline or lyrical decision. But once it’s done, hearing what Buc has come up with is “overwhelming” – in a good way. “You get to sit back and listen to this enormous world around the work that you've written… it’s really quite emotional hearing that stuff,” he says.

Reimagined songs can go in all different directions. In 2021, Buc transformed a track called Brace into dark, filmic work with a “full Batman vibe”. Another song, Unbreakable, was made bigger, grander and more festive with energetic strings. And on their 2020 cut Greatest Mistakes, the band stripped everything back to just vocalist Ian Kenny singing, Spark on acoustic guitar and the first violin doing some “really Irish fiddle stuff” at the front and centre of the stage.

But don’t expect the same set list in September – the vision for this year’s show is to deliver something evolved and even bigger than before. “We need to give people new experiences and a more developed version of what we've done before,” says Spark. “This time around, we really want to see how much we can turn our catalogue into an incredibly dynamic film – see how much of a blockbuster we can make. The idea is to present works in a way for the people who know them, there’s some sort of familiarity. But it’s also our job and artistic licence to present the songs in a way that’s hopefully even more beautiful and interesting than the way they know them.”

Spark is excited to spend the coming months dreaming big with Buc and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra. He’s happy to be one of the rare contemporary acts to truly embrace the potential of working with orchestras. “We’d do it forever if we could,” he says. “The sheer joy and power and spirituality of music in that format – when it all comes together, it’s just spine-chilling. And we’re not separate from the audience or the orchestra – we’re right in the middle of it. We literally set up in the middle of the orchestra. Being in the centre of that energy, but then also just being able to sit back and see the effect that the full symphony has on the audience – it melts the bloody heart, I tell you. It’s amazing.” ■

Many composers through the centuries have integrated their faith into their classical work. Stephanie Bunbury speaks to two of them.

For centuries, classical music and religion were inextricably entwined practices. From the earliest Gregorian chants through to the height of Christianity, the church provided patronage, venues and a readymade audience for the best and most ambitious composers of the day. In fact, it was Bach, one of the great composers of the time, who said, “I play the notes as they are written, but it is God who makes the music”, a reflection of how his spiritual beliefs influenced his music.

For Mary Finsterer, Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s 2023 Composer in Residence, she senses something similar in her own creative drive. Her three faith-based pieces to be performed by the MSO this year culminate in a new setting of the Stabat Mater, a 13th-century text that evokes Jesus’ mother’s suffering as she watches her son die on the Cross. “Even to write music is in itself an expression of what my faith is,” says Finsterer. “Whether it has a religious theme or not.”

Studying at the Melbourne Conservatorium of Music, her compositional training was predominantly in 20th-century technique, particularly serialism. At the same time, she was fascinated by the early history of western polyphonic music, with its echoes of the chants she had heard in church as a child. “I first became aware of the origins of western art music through Gregorian chant, which emerged in the ninth century and was intrinsic to Catholic liturgy,” says Finsterer. However, as a young composer, she says her creative expression, having been directly influenced by her formative training in composition, was not directly linked to her Catholicism. They were almost separate strands of her life.

It was when Finsterer had her first child that the place of faith in her life deepened. “I became more aware of the life and death cycle – my father had died in that time as well – and the focus of what life is really about became stronger.”

It was at that point that her approach to composition and faith converged. Her influences now range from Hildegard von Bingen through to Arvo Pärt; she even wrote a film score for Shirley Barrett’s South Solitary that drew on the Irish jigs and reels she learned through Irish dancing as a child. Her renewed relationship with her faith was thus

also a musical liberation. “Work is really important for us as human beings: what are we doing it for? What are we dedicating it to? I feel I gave myself permission to step outside what had developed from the training that I’d had.” Finsterer grew up in the latter half of the “century of disbelief”, but she can point to a string of modern composers – Messiaen, Stravinsky, Poulenc, John Tavener, Sir James MacMillan – who have also embraced and acknowledged faith and belief as their creative inspiration.

Sir James MacMillan, whose Catholic faith has inspired many of his sacred work, including his own Christmas Oratorio which he composed in 2019, has spoken widely on the topic of faith and its role in musical modernity.

“People are not hearing Bible stories as much as they did. Some younger people are coming across them for the first time in my musical setting,” says MacMillan.

So what does this music mean in our secular age, when many in the audience will never have sung a hymn? MacMillan is convinced it still communicates a sense of the sacred. “Certainly, people who do not have that conventional faith that I have nevertheless find something in music that meets that deep spiritual and psychological need,” he says. “And perhaps that curiosity is important to people. That there’s a deep need to have music take them to a special place that can sometimes speak to the divine or the beyond.”

Does the classical music of other cultures and religions carry a similar spiritual and sacred charge? For MacMillan, he has been interested in other musical traditions since boyhood; he studied ethnomusicology (the study of music’s cultural and social importance) in

“There is something about music which seems to be settled

“Work is really important for us as human beings: what

Indonesia, even learned to play gamelan – a type of musical ensemble native to Indonesia. “Of course these are spiritual art forms – and there is no embarrassment in these cultures talking about that,” he says. “In talking to people as I did, it’s quite clear they see their music as connected in some way with the work of God.”

Within the western tradition, composers who were agnostic – MacMillan mentions Vaughan Williams and Benjamin Britten – have chosen to write settings of scriptural texts or religious poetry. Even John Cage’s work 4’33” was originally called Silent Prayer. “There is something about music which seems to be settled in its search for the sacred, even in our modern times,” he says. “People even say it’s the most spiritual of the arts –and it’s not necessarily religious people who say that, but people who recognise that one is transformed through music.”

Writing music is a spiritual quest in itself, says Finsterer. “It’s a journey. When embarking on a work of art – a piece of music – one has an idea, a vision of what that is, but the journey will sometimes take you through very arduous terrain.”

While the music Finsterer makes is often praised as beautiful, that is not the point. “The beauty has a purpose: to honour God. And it is more than that. In a sense, music becomes a prayer. I’m grateful people find my music beautiful, that they find something for themselves there. That really means a lot.” ■

in its search for the sacred, even in our modern times.”The MSO will perform Mary Finsterer’s Stabat Mater at St Patrick’s Cathedral on Wednesday 27 September. * Mary Finsterer’s position as the MSO 2023 Composer in Residence is supported by Kim Williams AM.

are we doing it for? What are we dedicating it to ?”

What do a conductor, an airline and a philanthropic organisation have in common? Twenty noteworthy years with the MSO.

By Patricia Maunder.

Photography KRISTOFFER PAULSEN

By Patricia Maunder.

Photography KRISTOFFER PAULSEN

When he stepped onto the Sidney Myer Music Bowl podium in 2003, it wasn’t just Benjamin Northey’s MSO debut. “It was my first big concert with a professional orchestra,” he recalls. As if that wasn’t pressure enough, he chose to conduct the entire concert without the scores. “I still have no idea what I was thinking.”

Whatever it was, it worked, because “they were all tremendously impressed and immediately invited me back”. Again and again, especially from 2007, when Northey returned from studying in Europe. He was appointed as the MSO’s Associate Conductor in 2010, then Principal Conductor in Residence nine years later.

Northey has many fond memories of leading the Orchestra, including 2021’s WATA: A Gathering for Songmen, Improvising Soloists and Orchestra by the Wilfred brothers and Paul Grabowsky AO, and the collaboration with Nick Cave and Warren Ellis in 2019. All his Sidney Myer Music Bowl concerts are favourites too, “encapsulating Melbourne’s love of music and the generosity of the Orchestra”. Off-stage highlights include Russian violinist Maxim Vengerov saying “just relax” to a notably nervous Northey ahead of the MSO’s 2017 Season Opening Gala. “It was really funny; it was such an understated thing to say.” He also relished the opportunity to host the MSO’s Up Late series of online interviews (which were presented by partners TarraWarra Estate) during pandemic lockdowns. “We wanted to stay connected with our audience, subscribers and musicians, so we thought it was a good chance to celebrate the individual lives of the musicians.” Chatting with everyone from MSO First Violin Eleanor Mancini to then newly appointed Chief Conductor Jaime Martín, Northey tried to “stay positive and help everybody through that difficult time”. One viewer wrote: “You are the light that is getting me through COVID.”

Northey’s engagements for the rest of his MSO 20th anniversary year include August’s jazz concert with trumpet legend Wynton Marsalis with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra and MSO combined, spring’s Metropolis series, and October’s reprise of another career highlight, Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO’s Eumeralla, a war requiem for peace. “The MSO has made me the conductor I am today. I’ve grown with them over the 20 years, and I’d like to think I’ll continue to grow. I’ll be forever grateful.”

“The MSO has made me the conductor I am today. I’ve grown with them over the 20 years, and I’d like to think I’ll continue to grow. I’ll be forever grateful.”The

2004

World premiere of Peter Sculthorpe’s Requiem, featuring Yidaki player William Barton. 2006

Inaugural season of Victorian Opera, led by Artistic Director Richard Gill.

2008

Release of the Australian Chamber Orchestra’s first documentary film collaboration, Musica Surfica

2011

The Australian World Orchestra is established by conductor Alexander Briger. It gathers some of the nation’s finest musicians from international orchestras and ensembles.

2014

Australian violinist Ray Chen and Australian duo TwoSet Violin start uploading short, musical video skits to Instagram and YouTube, bringing classical music to social media.

2009

The Melbourne Recital Centre opened this year.

2012 Hamer Hall reopens to rave reviews after a major refurbishment transformed the venue into a 21st-century performance space.

2016

At 29, Nicholas Carter becomes Adelaide Symphony Orchestra’s Principal Conductor, and one of the youngest ever leaders of a major Australian orchestra.

2018

2018

Brett Dean’s opera Hamlet makes its Australian debut.

2022 Jaime Martín commences as the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra Chief Conductor.

World premiere of the Gunditjmara-language Eumeralla, a war requiem for peace, by Yorta Yorta singer, composer and current MSO First Nations Creative Chair, Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO.

Over the past 20 years, Cybec Foundation has enabled more than 80 young composers to contribute to the Australian orchestral canon through the Cybec 21st Century Australian Composers’ Program. Founded in 2003, this emerging artist program was made possible thanks to computer-science pioneer and Cybec Foundation founder, the late Roger Riordan AM and his wife, the late Patricia Riordan. Riordan would often recall that the first ever cheque from the newly-formed foundation was to the MSO. Since then, Cybec Foundation’s unwavering support has enabled the MSO to establish two additional emerging artist initiatives: the Cybec Young Composer in Residence and Cybec Assistant Conductor Fellowship. An MSO Board member, Honorary Life Member and long-time subscriber, Riordan loved classical music, says Arts Advisor to the Foundation’s board, Kay Attali. Even when the composers he supported created music different to his usual taste, “he was really delighted that it was happening,” she adds.

Every year, the four participants in MSO’s Cybec 21st Century Australian Composers’ Program each write a 10-minute work, with mentorship provided by established Australian composers. These new works are premiered at the annual Cybec Showcase concert, with one participant selected as the MSO’s Cybec Young Composer in Residence for the following year – in 2023, that’s Melissa Douglas.

The Cybec Foundation invests in MSO’s emerging composers and conductors because it’s a chance to “support young people who wouldn’t have an opportunity otherwise,” says Attali. Many alumni, such as Melody Eötvös and Lachlan Skipworth, have have become established and soughtafter artists. Attali considers this the program’s “greatest achievement”, given it provides vital opportunities early in a young composer’s career.

For both the MSO and Emirates, the pursuit of excellence is a common denominator. “The MSO is indeed a world-class orchestra,” says Emirates’ Divisional Vice President in Australasia, Barry Brown. “And we like to bring world-class experiences to our customers.”

As Principal Partner, Emirates invites customers and clients to the MSO concerts, as well as to the new Emirates Patrons Lounge, open after select Hamer Hall performances for members of the MSO’s Patron program. “We like to connect people through culturally rich experiences,” says Brown, adding that the MSO features on the in-flight entertainment channel showcasing Emirates-sponsored orchestras. As the official airline of the MSO, Emirates literally brings the Orchestra to the world during international tours.

That connection through cultural experiences can also happen in unexpected ways, such as when “COVID caught us all in the hop,” recalls Brown. Sponsoring the MSO’s digital Jams for Juniors concerts “kept both of our brands alive”. More recently, when Emirates launched its new Premium Economy into Melbourne earlier this year, MSO musicians played for special guests before they took a private tour of the new cabin.

Emirates, which has extended the Principal Partnership for an additional four years, will celebrate three decades of flying to Australia in 2026 – the same year the MSO turns 120. “It’s quite an auspicious year for both of us,” says Brown, who is particularly keen to develop opportunities that “bring music to a younger audience. That’s something we’ll be working on very closely with the Orchestra over the next four years.”

What about his most memorable MSO experience so far? At the top of the list is the multi-faceted 2019 event with astrophysicist Professor Brian Cox, A Symphonic Universe. “It brought home to me that music is the binding chemistry across many different fields and interests.” ■

“The MSO is indeed a world-class orchestra,And we like to bring world-class experiences to our customers.”

Off the back of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s 2023 Indonesia tour, Sarah Vercoe discovers what it takes to orchestrate an international tour and a successful cross-cultural partnership.

If music is a universal language that can cross cultural boundaries, the Indonesian island of Java is the perfect stage for this exchange to take place. Thrumming with a vibrant creative arts scene, the region is an epicentre for musicians to master their craft.

Since 2015, the MSO has partnered with the Government of the Special Region of Yogyakarta in Java, presenting arts management workshops, orchestral masterclasses and youth music camps as part of a Memorandum of Understanding designed to celebrate music and culture. In May this year, the MSO also signed a partnership proposal plan with the West Java Province.

Huda Albanna from Global Victoria, who was part of the Indonesian team during the original 2015 tour and was in attendance for the signing with West Java, says these partnerships are about more than sharing musical expertise – they are about collaboration and friendship where a mutual love of music is the uniting element. Referring to the Yogyakarta MOU, “this partnership has developed from an idea of a cultural exchange to Yogyakarta developing a music hall and forming a new orchestra,” says Albanna.

It’s a noteworthy evolution that has resulted in the partnership being renewed for another three-year period in 2022, the new memorandum signed during the MSO’s first visit since the pandemic pressed pause on in-person interactions. This year’s tour reaffirms the cross-cultural partnership and shared respect for music and culture with a series of multi-day workshops.

Orchestrating a tour designed to unify two nations through music is like piecing together a puzzle. Solitarily each piece is significant, but it’s only collectively that the picture can truly be appreciated. The blueprint is laid out months in advance, a multi-faceted feat that spans both nations and requires judicious preparation.

During the planning stage, the MSO’s leadership team is in perpetual motion. “We develop the program for the workshops as a team and put together a full presentation – translated into Bahasa – for the regional governments prior to touring,” says MSO’s Chief Operating Officer Guy Ross. Each year the content is fine-tuned to ensure it remains relevant to participants’ interests, and revised onthe-spot depending on participants’ experience and knowledge.

10.00AM

We’ll start the day with our full string orchestra rehearsal.

11.30AM

On day one and two we split off into different rooms. A leader

from the MSO will take each group through a tutorial of anything missed in rehearsal. On day three, I need to bring it all together so I tend to cancel these meet-ups so we can have more time in rehearsal.

12.30PM

We all have lunch together. It’s a chance for the kids to talk to us if they want to.

1.30PM

In the afternoon we do ‘tutti’, which is a musical term for ‘all together’. What we do

during this session depends on what everyone needs that day.

3.00PM

We head back to the hotel for a bit of downtime.

7.00PM

We’ll attend an event planned by the local government. Usually a formal gathering or the markets. They always make sure we experience a few little things while we’re there, which makes the whole experience more enriching.

In Yogyakarta, the MSO relies on the other half of the puzzle. “The Government of the Special Region of Yogyakarta plays an important role in coordinating a tour,” says Ross. From selecting and accommodating workshop participants to facilitating the logistical side on the ground, Ross says their participation bolsters success. “After several years it’s become easier but it’s still a large logistical preparation,” says Albanna who credits the success of these tours to the working relationship forged from the partnership. “There’s no one puzzle piece.” The combination that makes for a successful and long-lasting relationship comes down to three things, he explains: “The music community, the people working on the ground who push the limits, and the commitment of local government leaders and the MSO to crosscultural understanding.”

From Melbourne, the MSO’s Head of Touring and Chorus Callum Moncrieff is charged with – at times intriguing – logistical considerations, like securing a seat on a plane for a cello. “The cello normally flies with its own seat,” says Moncrieff. A necessary luxury when the instrument is worth close to the cost of a new Porsche.

How these valued instruments travel is just one of the complex cogs Moncrieff must consider when overseeing the logistics of an international tour. Others involve organising a hotel where the tour group can rest their heads between workshop sessions, budgeting, and making sure each of the 10 MSO employees touch down in the heady bustle of Indonesian airports after a succession of flights from Australia.

“One of the key elements of any kind of tour is to be flexible, to be able to respond to challenges and changes as they happen,” says Moncrieff. “Something I’ve learned in my time as tour manager is that everyone really just wants to know what’s going

on. It’s my responsibility to organise it but it’s also my responsibility to communicate it.”

Well versed on the ins and outs of touring to Indonesia, first violinist Sarah Curro has attended every tour since the partnership began. Over this time, Sarah says she has seen extraordinary growth from the students. “There have been some really talented kids who have come through who then go on to do incredible things. One of the most beautiful cellists we’ve had went on to study in Malaysia and then America,” says Curro.

For these talents to be nurtured in a workshop, hours of rehearsal must precede a tour. To prepare, Curro guides the Orchestra through the ‘bowings’ of the pieces they will workshop in Indonesia. An element she likens to choreography. “It’s like the steps in a dance, whether your bow is going up or down,” she explains. The aim is a polished visual performance that’s easy to follow.

What she values most is the personal experience she gets when there. “These are more than just tours. I’m really invested in it personally,” says Curro, who mentions she’s collected friendships with each visit to Indonesia and witnessed the enthusiasm of the students to hone their talents. Each year, two students are chosen to come to Melbourne to further their learnings, representing an incredible opportunity to develop their skills and knowledge base.

Since the MSO’s first visit, word has spread in the music community throughout Indonesia.

“Now, people from different regions are asking ‘when is the MSO visiting Indonesia again’,” says Albanna. But the benefits go both ways. “It’s a mutually rewarding learning exercise,” says Ross. “We bring our knowledge around how a western orchestra works and in return we get to learn about Indonesian culture, particularly from an arts perspective.” ■

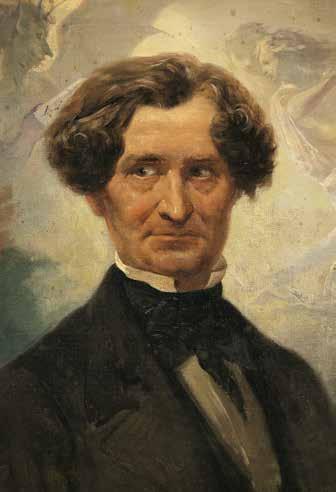

Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique is dubbed the world’s first-known psychedelic symphony. But as Elissa Blake discovers, there is much more to this monolithic work of art.

It is what some would call a romantic epic. A darkly perfumed symphony of obsession, charting the dizzy highs and selfdestructive lows of a pained artist and his drug-induced hallucinations. Hector Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique arrives with a great story attached to it and a reputation to match, says the MSO’s Head of Learning & Engagement Nick Bochner. “I think its reputation may be partly due to Leonard Bernstein, who was a great educator, storyteller and communicator of music,” explains Bochner

It was Bernstein, he says, who forged the link between the French composer and the psychedelic movement of the 1960s. “Bernstein emphasised those aspects of the work to help drive home how shocking and surprising Symphonie fantastique was when it premiered,” says Bochner. “I think it’s important to see the other aspects of the piece though.”

Composed in 1829-1830, Symphonie fantastique tells a lurid tale of an artist in the grip of romantic despair who poisons himself with opium. As the music unfolds, it conjures his drugfuelled hallucinations, beginning with his reveries, taking in a tumultuous party (realised in giddy waltz time), and ending with a march to the scaffold and a Satanic dream (“a hideous throng of demons and sorcerers,” Berlioz wrote).

And during all this, an elusive theme rears up, the idée fixe, the musical representation of the object of desire he will never hold.

Symphonie fantastique was explicitly inspired by Berlioz’s own romantic obsession with an Irish actress. The story goes that after attending a performance of Hamlet at the Odeon theatre in Paris in 1827, the composer fell in love with the production’s Ophelia – played by Harriet Smithson.

In classic ‘stage-door Johnny’ style, the 24-year-old composer bombarded her with love letters, all of which went unanswered. But rather than get the message and move on, Berlioz wrote Symphonie fantastique as a way to express his obsession, to get it out of his head, so to speak.

Smithson heard the work two years after its premiere in 1830 and realised that she was its subject. Sensing his moment, Berlioz began to court her once more, and in a dramatic move, he manipulated Smithson into marriage by swallowing what he claimed was a lethal dose of opium in front of her. Hysterical, she accepted, upon which Berlioz produced a vial of antidote from his other pocket. They were married in 1833. They separated seven years later. No surprises there.

“The drugs were just one small part of the inspiration for Symphonie fantastique,” says Bochner. “I think the astonishing originality and power of the work comes from a potent mix of a young Berlioz encountering Shakespeare, Beethoven and extreme infatuation pretty much all in one go.” Fermenting in what was an extraordinary musical mind, these influences sparked the five-

“The drugs were just one small part of the inspiration for Symphonie fantastique. I think the astonishing originality and power of the work comes from a potent mix of a young Berlioz encountering Shakespeare, Beethoven and extreme infatuation pretty much all in one go.”

movement work we know today, Bochner says.

“For some time I have had a descriptive symphony … in my brain. When I have released it, I mean to stagger the musical world.” So wrote Berlioz to a friend in 1829 and he wasn’t making idle promises. When Symphonie fantastique premiered in Paris at the end of the following year, he shocked and amazed listeners and critics. Many were thrilled by this revolutionary composition. Just as many were appalled by the recklessness of the passions it conjured.

“The piece was scandalous on several levels,” says Bochner. “Firstly, Berlioz brought new elements into symphonic composition. Like other composers immediately after Beethoven, he was overawed and intimidated to compose symphonies in the shadow of the great German. But unlike other composers he realised that the way to continue Beethoven’s legacy was to use those achievements as prompts to head in a new direction.”

Berlioz brought in elements from French Opera and vocal music and incorporated an overtly literary approach to what had, in Beethoven’s hands, become the pinnacle of pure music.

“The explicit references to drugs and infatuation were confronting at the time but so was his use of the Dies irae, an element of the Requiem Mass, in a secular work referencing witches. That was quite unheard of.”

Even so, Berlioz does broadly fit into the “romantic” genre, says Bochner, a hugely diverse category of music ranging from Beethoven and Mendelssohn to late Romantics such as Rachmaninov and Dvořák.

“As a listener you can expect an emphasis on the aspect of personal expression and emotion more than the form and manipulation of purely musical elements,” Bochner explains. “As a performer though, it can mean that you need to attend almost more to the aspects of form and coherence, in order to make an interpretation work and not allow it to be overwhelmed by those strong emotions.”

“THE SERPENT WITH KEYS” Berlioz also used some unconventional instruments in the mix, which contributed to the strangeness of the work. For example, he wrote a part in Fantastique for the bass ophicleide, a brass instrument suggestive of a bassoon or baritone saxophone but played with a mouthpiece similar to a trombone. The word “ophicleide” in Greek literally means ‘serpent with keys’.

“To the modern ear these instruments aren’t particularly psychedelic because we are used to hearing a much greater range of sonorities these days, but I can imagine the strangeness of the sonic combinations at the time would certainly have heightened the sense of unreality – even grotesqueness – that Berlioz was aiming to create,” says Bochner.

Even now, nearly 200 years after it was written, Symphonie fantastique challenges players and conductors alike.

“One of the great challenges in interpreting the work is the episodic nature of it,” explains Bochner. “Navigating the many transitions and retaining coherence is one challenge. Accurately performing some of the rhythmic elements is another.”

Because it was so ‘out there’ when it was composed, Symphonie fantastique will probably never go out of fashion, says Bochner. “Berlioz was incredibly talented and his compositional style was, for its time, unusually unique – a synthesis of dramatic, literary and the illustrative.”

“It was cinematic in a time before cinema,” Bochner says. “It demonstrates the power of pure music to create images, describe a narrative and tell a story. It’s an absolute whirlwind of sound, emotion, originality and narrative that’s as startlingly original now as it was in 1830.” ■

Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique will be conducted by Jaime Martín alongside excerpts from Mendelssohn’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream at Hamer Hall on 14-15 July at 7.30pm, and by itself as a Quick Fix at Half Six on 17 July at 6.30pm.

COMEDY AND MUSIC have long been rosy-cheeked bedfellows. Both art forms rely on rhythm and can placate, educate, and covertly subvert. Musical comedy has long felt at home in Melbourne, with the John Pinder-led clubs like the Flying Trapeze and the Last Laugh largely to thank. These clubs are also where female comedians fought their way out of obscurity, and Wendy Harmer was at the forefront. Wendy is a national treasure. Acknowledged as the first female stand-up comic in Australia, she rose to fame slogging it away at news desks, comedy clubs and tv shows in what we now think of as the golden age of Australian stand-up comedy. Here, Wendy charts the rise and empowerment of the Australian female comedian.

Foreword by Ali McGregor, award-winning, multi-genre artist and MSO collaborator

No longer “noice, different, unusual” in the parlance of Kath and Kim, our female comic performers and writers draw huge, adoring audiences for their work in stand-up, TV sitcom and panel shows, theatre, radio and podcasts. The equal of men in the business of “funny”.

As that rarity in the early eighties – a female stand-up comic – I was always asked: “Why aren’t there more funny women?” No one would ask that now. It’s hard to believe that there was a time when women’s comedic voices were almost absent, or, if they were heard, scripted by men. I was there when the revolution happened, when women barnstormed the writers’ rooms and busted out of the stereotypes that had defined them since the days of vaudeville.

In the twenties, the Cockney sing and dance man, Charles Norman, was a star of the Australian vaudeville circuit and worked alongside the leading performers of the era – Roy Rene, George Wallace and George Sorlie. In 1984 he wrote his memoir

When Vaudeville Was King: “For a woman to do comedy was a set act of songs and a few funny lines which they had worked on for years and years. To come out with patter as women do today... that was unknown. Our audiences would have sat back and said, ‘What’s this lass just coming out to talk to us in a funny way? It was a credit to those women that they were strong enough and courageous enough to get up in front of those tough audiences ... in front of all those men.”

In vaudeville comedy skits, the women were always the sidekicks – either a “character actress” of generous proportions or a “soubrette” with a trim figure. The star was the male comedian who chased the scantily clad young girl to be his “bit on the side”, and in turn was pursued by his wife, a harridan in hair rollers brandishing a rolling pin. The highly-skilled women in the role of a comic “feed” kept the mayhem on track as the men ad-libbed their way through the evening, risking the sack if they got more laughs than the blokes. It was in radio in the forties and fifties where women found an opportunity. The legendary duo of Ada and Elsie coined the phrase “Whacko-the-diddle-oh!” Dawn Lake, who graduated from radio to TV with her husband in the Bobby Limb Show, wrote her own signature phrase, “You tell ‘em luv”.

One who made the successful transition from the stage to television, Rosie Sturgess recalls of her days in the Tivoli: “I was under the jurisdiction of the comics, you had to do what they wanted. They wouldn’t give you any scripts, the comics. They’d have a rehearsal and say: ‘Righto love, when you hear me say, and here she is now’, you come on. And that’s how you’d learn it, you’d never see a script.” Rosie became a TV star in TV variety in Sunny Side Up and In Melbourne Tonight, where again, the men wrote her every line: “I didn’t do any writing...oh, no, no, no!”

As a female comedy writer for The Mavis Bramston Show in the mid-sixties, Barbara Angell was unique. A graduate from live stage revue, she invented her own character, the prissy “Mrs Duckett”, wrote songs for Gordon Chater, monologues for Carol Raye and describes her style as : “Not so ‘gaggy’. More a ‘female’ approach... I did a lot of writing for men. They had their reservations.”

In the seventies, we loved our women comedy stars - Mary Hardy, Denise Drysdale, Jeannie Little, Noeline Brown, Delvene Delaney – but they had little hand in scriptwriting. That was left to the men, the rest the women ad-libbed – live to air.

It was in 1983, in Australia You’re Standing In It when Mary Kenneally, as one half of Tim and Debbie made the catchphrase, “Amaaazing” (complete with airquotes) inescapable. Mary wrote half the show and remembers: “We spent a lot of time talking to the women about what sort of ideas they wanted to engage in. It was remarkable at that time.” Until then, she says, citing Monty Python and Aunty Jack, “all the good women’s parts were played by men, and women were in bikinis and low-cut dresses.”

I witnessed what happened after that when we women got our hot little hands on the comedy scripts for TV and stage, at last. It was the end of saucy French maids and nagging old bags. We re-imagined, re-wrote and found our unique Australian voice as schoolgirls, beauty therapists, TV hosts, bitchy executives, doctors, nuns, street kids, policewomen, cross-dressing male cabaret singers, ditzy aerobics instructors, and depressed or repressed housewives and mothers. On stage we were mad, bad and dangerous. Vulnerable, ironic, insightful, witty and wise. The female condition in all its gloriously funny variety. ■

Answers on page 50

1. Chamber singers joining Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra to perform All Rise by Wynton Marsalis, The _______ of Melbourne (7)

4. Birdsongs is the symphony orchestra tour of rock band _____ of Tokyo (5)

7. Umberto Clerici conducts works by Ravel and Camille SaintSaëns, and Debussy’s _______ à l’après-midi d’un faune? (7)

8. Lamp-lighting cords (5)

9. Became worthy of (6)

12. Jaime Martín conducts the Ligeti Concerto ________ (8)

15. A musician who performs the Saint-Saëns Symphony No.3 (8)

17. Violinist performing Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto under conductor Xian Zhang, ______ Yoo? (6)

18. Instrument of guest artist Javier Perianes who plays Brahms’ Piano Concerto No.1? (5)

21. Composer of the Symphonie fantastique, Hector _______? (7)

22. Fine cotton thread or La Marseillaise songwriter, Claude Joseph Rouget de _____? (5)

23. Symphonic poem from Czech composer Bedřich Smetana (2,5)

1. Mozart was older than Prodigies performer, Christian Li, when the composer created his Violin ________ No.3 (8)

2. Robert Schumann’s Symphony No.1 is known as the ______ Symphony (6)

3. A cello needed its own reserved seat on flights when the MSO completed its 2023 Indonesia ____? (4)

4. Played (horn) (4)

5. In the MSO’s Winter Gala, which celebrated violinist performs Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto? (3,4)

6. Gabriel Fauré’s Romances paroles (4)

10. Ancient Celtic priest (5)

M C E H S T S A L

11. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion: Part 2 No.37, O Lord, Who Dares to _____ Thee (5)

13. David Thomas performs the Mozart concerto for this rare instrument, the basset _______ (7)

14. Unique lizards of the Galapagos Islands (7)

16. Leisurely walk (6)

18. One Song: The Music of Archie Roach, musical director ____ Grabowsky AO? (4)

19. Instrument representing the duck in Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf (4)

20. Lowest sound in the percussion family, bass ____ (4)

Answers on page 50

Create words of four letters or more using the given letters once only, but always including the middle letter. Do not use proper names or plurals ending with S. See if you can find the nine-letter word using all the letters.

Answers

1 One of Rachmaninov’s most celebrated works is a set of variations for piano and orchestra called Rhapsody on a theme of

2 Dimitri Shostakovich frequently included a musical signature in his compositions comprising four notes that, in the German tradition of note names, spell D S C H. What are the notes S and H in the standard modern system?

3

In Disney’s Fantasia, Mickey Mouse brought broomsticks to life whilst the orchestra played The Sorcerer’s Apprentice by ____ _____

4 Early in his career, Prokofiev sought to improve his melodic writing by setting himself the challenge of writing this work without the aid of a piano. It is commonly known as the _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Symphony.

5 Australian composer Nigel Westlake incorporated this work by Saint-Saëns in his soundtrack to the movie Babe

6 Whose violin concerto was the earliest written of the following: Brahms, Sibelius, Mendelssohn, Bruch, Tchaikovsky?

7 The story of Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique involves an artist – the protagonist of the story – attending whose funeral?

8 Opening with one of the most iconic flute solos in the orchestral repertoire, Debussy wrote a work inspired by what poem by Stéphane Mallarmé?

9 The most well-known work from Smetana’s set of orchestral works titled Má vlast depicts what Czech river?

10 Handel’s coronation anthem Zadok the Priest was composed for the coronation of which British Monarch in 1727?

11 John Williams’ Imperial March, depicting Darth Vader, first appears in which Star Wars film (by release order)?

12 What three works make up Respighi’s ‘Roman Trilogy’?

13 Supposedly because the opening is reminiscent of thunderbolts, what nickname was given to Mozart’s Symphony No.41?

14 After being denounced by the Communist Party for his opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, Shostakovich came back into favour with what orchestral work whose premiere supposedly prompted a 45-minute-long applause?

15 The celebrated Hallelujah Chorus comes from what oratorio by Handel?

16 Who composed The Man from Snowy River’s award-winning score?

17 One of the world’s most popular jazz musicians, Wynton Marsalis, has won how many GRAMMY® awards?

18 Scottish composer Sir James MacMillan’s Christmas Oratorio was completed in what year?

Pizza making, party hosting and enjoying epic family movie nights is how our Principal Viola spends his days away from the Orchestra.

Photography DANIEL MAHON

Photography DANIEL MAHON

RISE AND SHINE. A day off (and every other day) begins with two double espressos. We [partner, Jill Griffiths, freelance bass player and teacher] eat breakfast at home after getting the kids out of bed – usually pancakes with streaky bacon and maple syrup. That’s the favourite. Our miniature pinscher Dudley loves to go to the dog beach at Brighton. It’s an excellent beach. We used to have chickens when he was a puppy, but his prey drive was too strong. He just couldn’t help himself. He pinned one of them down – he didn’t hurt it – but we had to start time-sharing the backyard. The chickens would have the mornings and then Dudley would have the afternoons. When we moved house, we decided it was time for the chickens to move to a lovely country life in Warragul; which I’m kind of jealous of. MAKING DOUGH. If I’ve got a day off, I like to have people over. That’s the ideal. I used to brew beer, but COVID put an end to that, so I started baking bread instead. I make a massive loaf of sourdough every week. It’s really good bread. If ‘papa’s bread’ isn’t around, my girls get a bit annoyed. I also started making pizza and I’m kind of obsessed with that now. I’ve invested in a proper pizza oven. People say to me; ‘When’s the viola party?’, ‘When’s the pizza party?’ They’re pretty famous. I start making the dough the night before to give the yeast longer to create more complex flavours in the final dough. But it’s great fun and I love doing it. It’s something I can share and I love the process. I’m aiming for repeatable results. The pizza nights usually go pretty late. We have a decent-sized

yard, a lovely courtyard, people can sit out there and relax. Let’s just say we never have any leftovers. WHEN WE CAN. We really like to go bushwalking, short walks in the forest, up in the Dandenongs. We just love that, when the weekend isn’t taken up with the girls’ extracurricular activities – orchestras and choirs, things like that. And pizza parties of course. MOVIE NIGHTS. We have a family movie night if I’m not working, which we love. We try to find movies that are a series – Marvel, Star Wars, [The] Matrix – those kinds of epic things. Sometimes we get takeout. Sometimes we even order Domino’s.

WHEEL

Calm, Clam, Hale,

Heal, Helm,

Male,

Meal,

“I’ve invested in a proper pizza oven. People say to me; ‘When’s the viola party?’, ‘When’s the pizza party?’ They’re pretty famous.”

Eumeralla, a war requiem for peace brings into focus a period of Australia’s history that is yet to be fully understood. Written and composed by Deborah Cheetham Fraillon AO, this requiem for peace will be sung entirely in the ancient dialects of the Gunditjmara people.

Saturday 14 October / 7.30pm

Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall