STUDI DI MEMOFONTE

Rivista on-line semestrale Numero 29/2022

FONDAZIONE MEMOFONTE

Studio per l’elaborazione informatica delle fonti storico-artistiche

www.memofonte.it

COMITATO REDAZIONALE

Proprietario Fondazione Memofonte onlus Fondatrice Paola Barocchi Direzione scientifica Donata Levi Comitato scientifico Francesco Caglioti, Barbara Cinelli, Flavio Fergonzi, Margaret Haines, Donata Levi, Nicoletta Maraschio, Carmelo Occhipinti

Cura redazionale Martina Nastasi, Mara Portoghese

Segreteria di redazione

Fondazione Memofonte onlus, via de’ Coverelli 2/4, 50125 Firenze info@memofonte.it

ISSN 2038-0488

ANGELAMARIA ACETO

On some late Renaissance ornament drawings at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford: Giovanni Battista Lombardelli, Avanzino Nucci, Giovanni Battista della Rovere and a proposal for Federico Brandani

GIOVANNI MAZZAFERRO

Lo sguardo condiviso: il viaggio di Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle e Charles Eastlake nel Centro Italia (settembre 1858)

p. 1

p. 25

KATIE LISSAMORE-SPOONER

The Eastlake Library: An 1894 Catalogue p. 70

MARGHERITA D’AYALA VALVA, CAMILLE NOVERRAZ

Gino Severini’s encounter with the Groupe de Saint-Luc in Switzerland and his path towards «despoliation», 1923-1947

p. 79

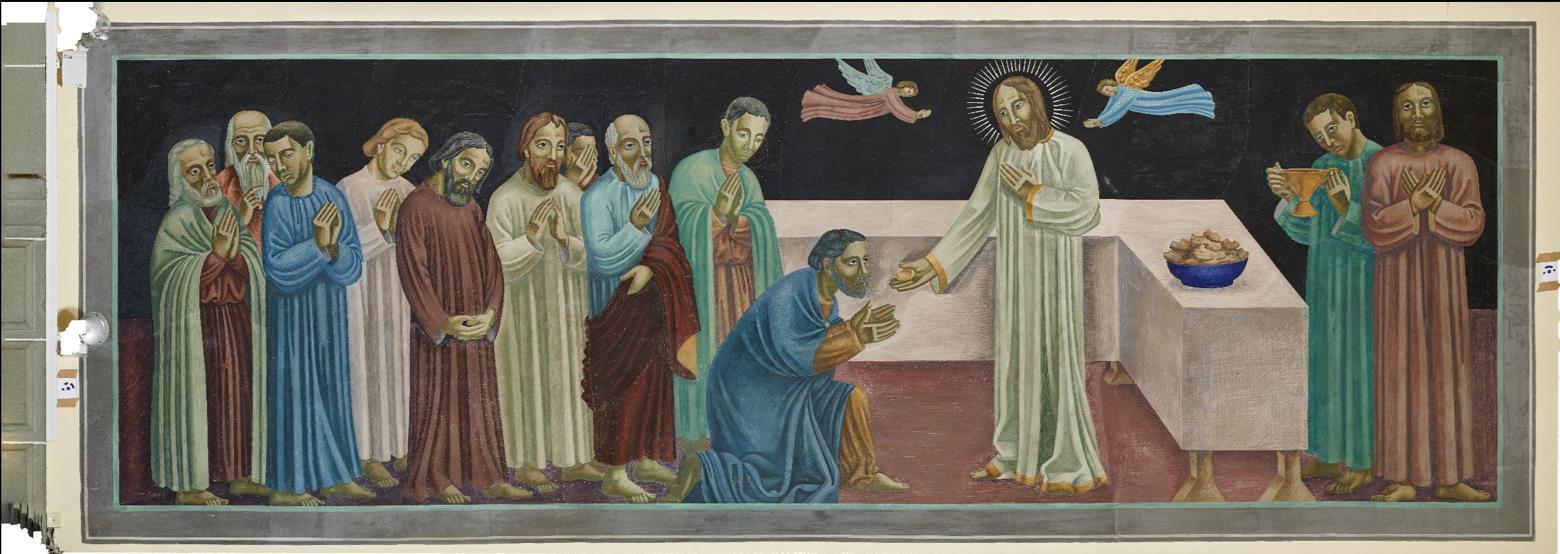

ON SOME LATE RENAISSANCE ORNAMENT DRAWINGS AT THE ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM, OXFORD

: GIOVANNI BATTISTA LOMBARDELLI, AVANZINO NUCCI, GIOVANNI BATTISTA DELLA ROVERE AND A PROPOSAL FOR FEDERICO BRANDANIThe aim of this article is to present a selection of drawings for ornament from the collection of the Ashmolean Museum of Oxford hitherto anonymous or still carrying problematic attributions. Encompassing a wide range of decorations, including frames, cartouche and grotesque designs for translation in painting or other media, whether seen as single motifs or combined to form frieze or ceiling projects, ornament drawings form one of the most elusive categories which specialists still confront today. As well as the loss of the original contexts for which they might have been conceived, it is their use and function that greatly contribute to their anonymity. While it is often possible to place them chronologically, or even to link them to the house-style of a workshop, the vocabulary often reflected the broader fashion of the time, with schemes and single motifs repeated with little variation design after design and over decades. In many instances, such drawings were conceived as pattern-drawings, often gathered to form model-books, now dispersed. These would have comprised drawings by the master, but also variations by workshop members, who remain unnamed largely due to the lack of documentary evidence. Furthermore, their open-ended nature, both as a quick source of ideas for the workshop to draw from and for patrons to browse1, meant designs were presented with very generic and neutral content that could be adapted and re-adapted to a variety of contexts. The lack of armorial devices or specific iconographies associated with this use is often a defining characteristic that complicates matters, leaving us to rely on a purely connoisseurial exercise. When such visual information, in turn, is included, it provides invaluable clues, as seen in a splendid, hitherto unattributed sheet at the Ashmolean Museum, which is the first I shall present2 .

A problem-solving drawing (Fig. 1) the artist began to work in graphite freely, jotting down solutions for an armorial frieze, which would have embellished a rectangular stateroom, then turning to pen and rich diluted ink to fix some of his thoughts. The presence of measurements in Roman palmi clearly indicates the draughtsman had a precise commission in mind. The height of the frieze would have measured 1.34 meters (6 palmi), excluding the upper and lower cornices, the length of both the long sides roughly 11 meters (49 palmi), and that of the short sides just over 7 meters (32 palmi). In the two segments above, the artist experimented with different solutions, with wider compartments containing empty coats of arms surmounted by coronets that do not correspond correctly to any normal Italian rank of nobility. The drawing is effectively still a general concept. The aspects of the coat of arms, and the more detailed iconography, would have been defined at a later stage of the design in collaboration with the patron, whose involvement was evidently regarded as fundamental for their accomplishment, as testified by Giovanni Battista Armenini in a chapter of the De’ veri

For the fruitful and stimulating exchanges about the drawings here presented I shall like to warmly thank Francesco Grisolia, Florian Härb, Elena Rame, Laura Teza, Patrizia Tosini, Rhoda Eitel-Porter, Simonetta Prosperi Valenti Rodinò and James Mundy.

1 For this aspect, in relation for example to the many drawings by Luzio Luzi that have come down to us, see PROSPERI VALENTI RODINÒ 2007, p. 284, no. 201b

2 Inv. WA1948.85. Here attributed to Giovanni Battista Lombardelli, Armorial frieze. Pen and brown ink with brown wash over black chalk. 416x537 mm. Inscribed throughout the image in pen and brown ink by the artist: Palmi 6 mano / p 49 / p 6 /p 32.

precetti della pittura (Ravenna 1586)3. The cartouches are flanked by female figures holding branches whom the artist imagined as either standing or seated. Smaller compartments, framing landscapes, separate each heraldic element. Such a geometrical articulation would have matched perfectly with the beams and lacunars of a wooden coffered ceiling, with which many of these types of friezes were often combined, and in dialogue with which must, at least in part, have developed.

Clearly appearing in the third segment is the coat of arms of the Cesi family, showing a dogwood tree sitting on a sextuple mount. On each side are two further coats of arms, this time surmounted by a cardinal’s hat. They are separated from the central compartment by two smaller panels each decorated again with the Cesi arms, but this time combined with two rampant lions, a family emblem. On the far left, in graphite alone, is a further cartouche, now supported by two lively putti. In the two graphite jottings in the lower left, the artist tried to work out the number of compartments needed to fill the given space. Finally, in segment below, the Cesi’s charge appears again combined with rampant lions and set against military trophies, the latter an iconographical element revealing the celebratory nature of the frieze.

In his 1956 catalogue of the Italian drawings of the Ashmolean Museum, K.T. Parker (1895-1992) believed the cardinal’s coat of arms to belong to Pier Donato Cesi (1585-1656), the younger, who was raised to cardinal in 1623 by Pope Urban VIII (1623-1644), in so doing placing the drawing well into the 17th century4. Hugh Macandrew on the other hand rejected this identification in his 1980 supplement to Parker’s catalogue without, however, suggesting an alternative solution5. Yet, there can be little doubt that the coats of arms are those of Cardinal Pier Donato Cesi (c. 1522-1586), senior, from the line of Acquasparta in Umbria. This shows the Cesi arms impaled with that of Antonio Ghisleri, who reigned as Pope Pius V between 1566 and 1572, and who had raised him to cardinalate in 15706 .

Pier Donato’s fame is, above all, attached to the construction of the Palace of the Archiginnasio in Bologna, which he directed as apostolic vice-legate under Pope Pius IV (1559-1565) between 1560 and 1565, as well as to the construction of the Oratorian Church of Santa Maria in Vallicella in Rome. An ally of the Granduke Cosimo I de’ Medici, who supported his candidacy to the papacy in 1572, a keen collector of antiquities and a patron of Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), and of the sculptor/architect Guglielmo della Porta (c. 15151577), Pier Donato became the most prominent member of the family after his election as a cardinal. He invested substantial energy and sums of money in artistic commissions in the Eternal City and in the numerous family feuds outside, which would have promoted and perpetuated the magnificence of the family name7

Many were the artists at work for Pier Donato who still today remain unnamed. Yet, despite some blurry passages caused by the oxidation of the iron gall ink and the synthetic nature of the study, I believe it is possible to discern in our drawing the hand and mind of one of the artists active for the Cardinal in the 1580s, namely the Marchigian Giovanni Battista Lombardelli (1535/1540-1592)8. The layered technique with rich brown wash still echoes that of Marco Marchetti da Faenza (before 1528-1588) with whom, according to Lombardelli’s

3 On the role of patronage and on the related sources, and for the problems surrounding the attribution of frieze designs from the second half of 16th century, see AMADIO 2016. For another relevant reading see also AMADIO 2016(2017)

4 PARKER 1956, pp. 411-412, no. 779.

5 MACANDREW 1980, Appendix 2, pp. 292-293, no. 779

6 For a biographical profile of Pier Donato Cesi see BORROMEO 1980.

7 For Pier Donato Cesi as a patron of the arts, with further references to Lombardelli’s activity, see NOCCHI 2015; 2017a; 2017b; TOSINI 2018, especially p. 116.

8 For a biographical profile of Lombardelli see NICASTRO 2005 On Lombardelli as a draughtsman see the fundamental catalogue by GRISOLIA 2010 with ample bibliography on the artist. See also TOSINI 2011 and 2017

principal biographer Giovanni Baglione, the artist had first trained9. The oval facial types with tiny, rounded features, while reminiscent of those of Raffaellino da Reggio (1550-1578), whose manner Giovanni Battista imitated and emulated, are charged with expressionistic, at times grotesque, traits, revealing the artist’s very personal interpretation of the master’s style. The motif of the female standing figures leaning against the cartouche as if an integral part of the ornament, rather than a distinct unit, is also a feature recurrent in Lombardelli’s repertoire as seen in the friezes for the Cesi Palace of Acquasparta. Compelling comparisons can be made with hastily executed scenes depicting the Life of St Antony (Figs 2-4), in a private collection, preparatory for frescoes in the homonymous church on the Esquiline, Rome10 , of 1585-1586, as well as with the quickest passages in studies for the aforementioned friezes in Acquasparta, such as The Triumphs of Lucullus in Madrid, Prado11, and in Florence, Uffizi12 (Figs 5-6). The Ashmolean study would appear to date from this period of Lombardelli’s career.

The overall scheme is highly dependent on Raffaellino’s decorative friezes conceived by 1578 for the Villa Gambara in Bagnaia (Villa Lante), where Lombardelli might have collaborated. Yet while working within conventions, the drawing is striking for the licentia, as exemplified by the central coat arms, which Macandrew believed to belong to an identified member of the Cesi family. This is nothing more than a free and imaginative divertissement. Here, in a moment of fervid creativity and personal experimentation, the artist inscribed the arms in an escutcheon, which is in turn contained within a cartouche. Breaking conventions, he then decorated the latter, inserting an eagle on the left, with the rampant lion another emblem of the Cesi family, and three bends on the right-hand side. In so doing, he compressed the heraldic information within a small space, including the Ghislieri’s emblem, now reversed. Above all, the Ashmolean sheet displays Lombardelli’s skills as a creative composer of a specific type of decorative cycle, that of painted friezes, in which he must have been fluent. One more frieze study has been persuasively reattributed by Patrizia Tosini to Lombardelli rather than Raffaellino13. This is a study for Palazzo Buzi in Orvieto, now in Darmstadt, Hessisches Landesmuseum, though it is rather different in function from our drawing. Even more interestingly, the Ashmolean sheet provides evidence for Lombardelli’s interest in armorial designs, of which Baglione again informs us

Né tralascierò, che sono suoi molti disegni di diuersi scudi d’arme con figurine e puttini tanto belli e gratiosi che in quel genere sperar più non si poteva; e furono in legno intagliati (I will not omit the fact that many are the drawings of various coats of arms with figures and putti, which are so beautiful and refined that you could not hope to find better. And they were carved in wood)14 .

Baglione’s text implies the existence of a corpus of drawings for heraldry, seemingly for translation in print.

In another inventive cartouche design (Fig. 7), both the inclusion of the Aldobrandini emblems and some stylistic traits must have prompted K.T. Parker to perceive the personality of Cherubino Alberti (1553-1615), whose activity under Pope Clement VIII Aldobrandini is

9 BAGLIONE 1642, pp. 45-46, especially p. 45

10 For the sheets see GRISOLIA 2010, pp 5, 25, note 10.

11 Inv. D002968. 176x230 mm. Pen and brown ink and grey brown wash. As Giovanni De’ Vecchi in TURNER 2004, no. 35, and then correctly attributed, together with a related group of drawings in Florence, Uffizi, to Lombardelli by GRISOLIA 2010, pp. 6-9.

12 Inv. 14171. Florence, Uffizi. Giovanni Battista Lombardelli, The Triumphs of Lucullus Pen and brown with brown wash. 180x239 mm.

13 See TOSINI 2011.

14 BAGLIONE 1642, p. 46.

largely documented15. Philip Pouncey was surely correct however in suggesting the name of Pseudo Bernardo-Castello, later identified with Avanzino Nuci (c. 1552-1629) by the same scholar, with an unpublished note in the departmental archive of the museum16. In support of this attribution I’d like to draw on a comparison with a sheet in Biblioteca Reale in Turin, yet another example of Avanzino Nucci’s draughtsmanship, if rather provincial, identified by Pouncey with a manuscript note on the mount, but to my knowledge, like the Ashmolean drawing, hitherto unpublished (Fig. 8)17 No work can be connected to this design. However, Nucci’s activity for the Aldobrandini is documented by a payment for «sei historie» (six paintings, now lost) in c. 1604, executed for the private chapel of Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini, nephew of Pope Clemente VIII, in his Palazzo Aldobrandini al Corso, Rome (now Palazzo Doria Pamphilj)18 and our cartouche design may presumably date to this time of his career. The phoenix above centre might be a reference to Clement VIII, detail that seems to point towards the years of his papacy for the execution of this drawing19

In a further inventive drawing, personifications of Justice and Fortitude flank a cartouche on the left and right, respectively, for which the artist tries alternative solutions (Fig. 9)20. At the top is a cardinal’s hat with winged putti imagined in flight as they draw back curtains open to unveil the scene below. The generic iconography, with the two virtues above being commonly found as decorations of escutcheons, and the absence of inscriptions or emblems, makes it difficult to narrow down its purpose, and in fact, our drawing retains all the traits of a repertoire drawing to be shown to one or more prospective patron for discussion. The hand is however that of a well-defined and worthy artistic personality working in the late Renaissance, whom Parker attempted to identify with Giovanni Battista Ricci da Novara (1552-1627). More recently, Giovanni Santucci put forward the name of the Modena born painter and designer Giovanni Guerra (1544-1618)21. As to the latter suggestion, neither the facial types nor the handling chimes with those by Guerra. Guerra’s mannered and slender figural types can in contrast be observed in his extensive corpus of drawings that has come down to us. This now includes a hitherto unnoticed sheet, again in the Biblioteca Reale of Turin, catalogued by Aldo Albertini as in style of Taddeo Zuccaro22, but unmistakably a work by Guerra, that I should like to note in this context (Fig. 11)23. Parker’s attribution, on the other hand, although incorrect, is indicative. The scholar’s acute eye evidently perceived the same traits seen in drawings once attributed to Ricci da Novara, by virtue of the monogram

15 PARKER 1956, App. B, p. 557, no. 19.

16 Unpublished notes on the Talman collection, Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, Western Art Department. This was evidently an oral communication to Hugh Macandrew who in the 1970s was preparing a complete catalogue of the Talman drawings, a project which remained unaccomplished.

17 Inv. 15725 DC, Turin, Biblioteca Reale. See BERTINI 1958, p. 52, no. 388 (as Ventura Salimbeni). Pen and brown ink with brown wash, the composition squared for transfer, on laid paper. Inscribed on the mount «Pseudo Bernardo-Castello (Pouncey)». See also BERTINI 1958, p. 52, no. 387 (as Ventura Salimbeni) for another example of Nucci’s draughtsmanship, also carrying Philip Pouncey’s manuscript note.

18 HIBBARD 1964.

19 «E a tempi nostri è stata la fenice impresa di papa Clemente Ottavo senza motto, che più volte l’abbiamo veduto nella sua sedia pontificale» (RIPA 1624-1625, II, p. 345)

20 Inv. WA1942.54.109. Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, Small Talman album. Here attributed to Giovanni Battista della Rovere, Cartouche design Pen and black ink over lead or graphite with grey wash on laid paper. The sheet belongs to an album assembled by the collectors and architects William and John Talman gathering a remarkable collection of ornament prints and drawings, at the Ashmolean Museum since 1942. It carries one of the Talman’s elaborate gilt borders.

21 PARKER 1956, cat 667 G. Santucci under folio 109 in the on-line catalogue at John Talman: an early eighteenth-century collector of drawings (unipi.it) <January 1, 2022>

22 Inv. D.C. 15872, Turin, Biblioteca Reale. Here attributed to Giovanni Guerra, Coronation of a pope. Pen and brown ink with brown wash on laid paper. As «Cerchia degli Zuccaro» in BERTINI 1958, p. 59, no. 455.

23 The delicate use of pen and wash suggests the sheet dates from c 1585-1590, at the time of Guerra’s intensive activity under Pope Sixtus V in collaboration with Cesare Nebbia.

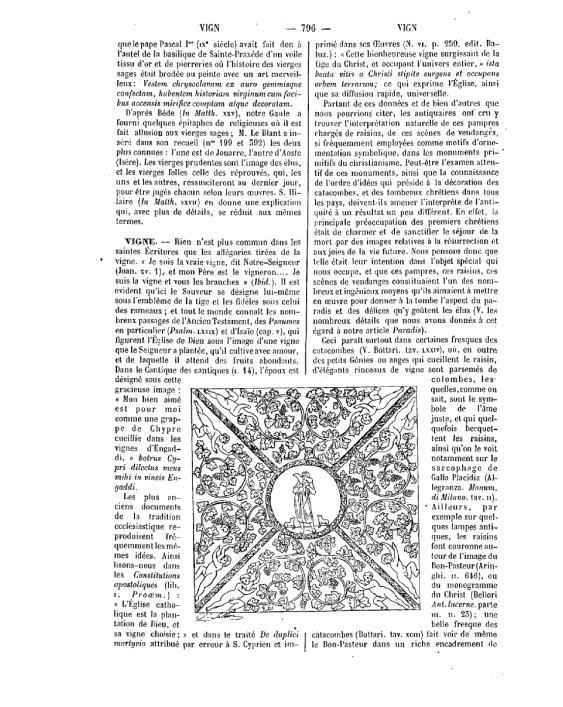

‘JBR’ appearing on some sheets, interpreted by early connoisseurs as the initials of the artist. It was Philip Pouncey who later recognised it as the signature of Giovanni Battista della Rovere (1561-1633), to whom our sheet can be confidently attributed24. The same expressive and free treatment of anatomy, use of free chalk underdrawing and vibrant pen line, enriched by delicate wash, can be detected in many other sheets under Giovanni Battista della Rovere’s name, such as a signed and dated one at the Morgan Library, New York (Fig. 10)25. Otherwise known, along with his brother Giovanni Mauro, for drawings of religious narrative subject produced in line with the culture of the Counter-Reformation, this represents a rare example of a sheet of purely ornamental nature by Giovanni Battista. Among the most beautiful and yet problematic ornament drawings in the Talman collection of the Ashmolean Museum is an elaborate design for a stucco panel over a fireplace (Fig. 12)26 A repertoire of inventive ideas, it depicts an empty escutcheon, flanked by Minerva and by a personification of Fortitude, each holding an olive and an oak branch – an allusion to the concord of Peace and Strength. Two putti below sit on a plinth holding flames, their heads turned towards the centre of the composition, while above two mischievous boys balance on festoons and pull strings to which the heraldic element is attached. The name of Taddeo Zuccaro (1529-1566) as the author of this drawing was first suggested by Philip Pouncey, who rightly felt that the design showed a taste postdating Baldassarre Peruzzi (c. 1481-1536), to whom Parker had initially attributed our sheet. The suggestion was taken up by John Gere in his seminal publication of 1969 on Taddeo’s drawings. Following Parker, Gere persuasively argued that the oak might refer to the ducal family of della Rovere. He saw it as a drawing produced by Taddeo for one of the Della Rovere’s residences during his stay in the Duchy between 1551 and 1553. At this time, the taste for stucco decoration was particularly in vogue in the Marche and found an original interpreter in the sculptor Federico Brandani, also from Urbino, (c. 1525-1575). Gere felt that the function and Marchigian context for which this drawing might have been produced could account for the formulae employed, as well as for the «deliberate» handling of the pen which he admitted is unlike Taddeo’s own. However, when considering the drawing in the context of Taddeo’s draughtsmanship, even when compared to drawings for decorative enterprises, the sheet remains so exceptional that the context and function may not be sufficient to justify the drawing’s form. It seems to me that the rich linearity noted by Gere might instead be in debt to Prospero Fontana’s drawings, as seen in studies connected to the Feast of Gods in Villa Giulia27, whose mannerist and expressive traits our draughtsman tempers with a classicising taste. And I wonder if we should look instead for an artist where such traits converge. One possibility that should be contemplated is that this, rather than being a drawing by Taddeo producing an exceptional sheet in the manner of Brandani’s stucco work, on the contrary could be an example by Federico Brandani, designer and draughtsman between the Zuccari and Prospero Fontana.

24 For the question of the monogram, see VITZTHUM 1961; A. Blunt, Supplements to the Catalogues of the Italian and French Drawings, with a History of the Royal Collection of Drawings, in SCHILLING 1971, p. 115, no. 415 25 Inv. 1993.401. New York, The Morgan Library & Museum. Giovanni Battista della Rovere, Doubting Thomas, pen and brown ink with brown wash on laid paper. Signed and dated on verso: «1593 JBR 167 ?temb» For other compelling comparisons, see London, British Museum, inv. Sl,5237.69, also signed and dated; London, Windsor Castle, inv RCIN 990228 and RCIN 990230, or Florence, Uffizi, inv. 7278 F. 26 Inv. WA1942.54.122. Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, Small Talman album. Here attributed to Federico Brandani, Design for an overmantel panel, pen and brown ink on laid paper, lower left edge partially made up, the sheet surrounded by an elaborate gilt border. Inscribed on the verso «S(cudi) 119 da lac(.)q», very plausibly by the artist himself. On the drawing see PARKER 1956, pp. 231-232, no. 464 (as possibly by Baldassarre Peruzzi); GERE 1969, pp 45-47 and pp. 182-183, no. 155 (as Taddeo Zuccaro); G. Santucci under folio 122, as Baldassarre Peruzzi, with no reference to Gere’s publication mentioned above, in the on-line catalogue at John Talman: an early eighteenth-century collector of drawings (unipi.it) <January 1, 2022>

27 Inv. 1875,0710.2631. London, British Museum See GERE–POUNCEY 1983, part 1, no. 103.

Otherwise previously unknown as a draughtsman, the hand of Brandani has in recent years been identified by Giovanni Santucci in a drawing of c. 157128. Now presented in two sheets, these were probably once joined together to show a project for the remodelling of the fifteenth-century Chapel of the Dukes of Urbino (or of the Annunciation) in the Basilica of Loreto, commissioned by Guidobaldo II della Rovere (reigned 1538-1574). Works on the chapel were underway when they were paused in May 1572, only to resume a decade later under the patronage of Guidbaldo’s son, Francesco Maria II (reigned 1574-1631), this time with Federico Zuccaro as the artist in charge29

The drawing is beautifully layered to suggest the different depths and textures of the wall. Two important implications in my opinion arise from the identification of the Loreto design, which have not been remarked upon as yet. First and foremost, Brandani effectively emerges not only as a skilled draughtsman but also as an artist who has deeply absorbed Taddeo’s mature draughtsmanship. The comparisons here presented eloquently illustrate this point (Figs. 13-16) The consonances are such that one wonders if the hand of Brandani might be further recognised among some of the very many drawings still associated to the names of Taddeo or indeed Federico «from the critical 1560s» onwards30 . This would in fact be hardly surprising, given the intense exchange that must have existed between Brandani and Taddeo since the 1540s in Urbino but also in Rome, where their presence is documented in 1553 in Villa Giulia along that of Bartolomeo Ammannati, and of the Bolognese Prospero Fontana, who had taken over direction from Giorgio Vasari. Brandani often turned to Taddeo for inspiration of specific narrative scenes decorating his ceilings, as those in the Palace Baviera in Senigallia (late 1550s), or in the Palace Corboli Aquilini in Urbino (now in Palazzo Ducale, after 1562-1568). However, he was evidently a multifaceted artistic personality. For the Loreto project now demonstrates that he was capable of devising the entire ensembles, rather than being a mere executor of other artists’ designs, as his personality has been characterized by some scholars31. And these were ensembles where the narrative scenes never tended to be literally reproduced but rather appropriated. The second and broader consideration concerns the role of drawing in Brandani’s creative process – a practice no doubt less often associated to the activity of plasticatori, but evidently a fundamental and economical tool not only in the creative process, but also as a reference for workshop members often charged with the translation of the master’s ideas.

The overmantel’s drawing style clearly suggests an earlier dating than the Loreto design. But with this, it shares its dependence on Taddeo Zuccaro, as well as revealing the mind and hand of a sculptor in the clear taste for the interplay of three-dimensional and inrelief elements. And that this sculptor might be identified with Brandani seems to be indicated

28 Invs. WA1944.102.48 and WA1944.102.49. Oxford, Ashmolean Museum, also and perhaps not accidentally forming part of the Talman collection. See SANTUCCI 2014. I shall note that while it is possible that two sheets were once joined together, there is no material evidence that the project was actually ever folded to form a paper model, as suggested by Santucci, as the folding marks marked ‘b’ by Santucci himself in fig. 14 are not present.

29 For a recent contribution on Federico’s activity on the Loreto chapel, see RUSSO 2015

30

For the thorny question concerning the distinction of hands between the two brothers see, at least, MUNDY 2005. The sheet in Berlin, Staatliche Museen Kupferstichkabinett, inv. 2214, was previously believed to be a study for the Assumption of the Virgin in the Pucci Chapel (ivi, pp. 171, 184, note 19). However, this is no doubt a later study by Federico for one of the compartments on the ceiling of the Chapel of the Annuciation in Loreto, as most evidently shown by the framing lines This was noted by John Gere with a manuscript annotation on the mount, and is now accepted by James Mundy. I am enormously grateful to James Mundy for sharing an entry of his forthcoming catalogue of Federico’s drawings with me. For the study for the Pucci Assumption in a private collection, an attribution to Taddeo, rather than to Federico, was favoured by GERE 1966, p. 290.

31 For example by GERE 1963, especially p. 310, note 17, and by CLIFFORD–MALLET 1976, especially p. 406, note 10. In fact, Franco’s and Taddeo’s drawings were only some of the many graphic sources Brandani used for inspiration. For two recent useful overviews on Brandani, see DELPRIORI 2017 and PROCACCINI 2019, both with ample bibliography.

by comparisons with the panel’s vocabulary and its specific declension with his finished work, including the splendid Nativity in the Oratorio di San Giuseppe, a work that is culturally not distant from our drawing32. The similarities between the physiognomy of the candle-bearing children and the chubby, expressive putti modelled, almost drawn, on the ceiling must surely not be coincidental (Figs. 17-19). Equally, striking is the idea of the drapery resolving in voluminous bows, or the play of tightly folded curls and masks and festoons – all original motifs that recur throughout Brandani’s production from the second half of the 1550s (Figs. 20-23). This encompassed fashionable overmantels, where Brandani re-proposed over and over established all’antica formulae which must have been highly sought after by the local elites (Figs 24-25)33

32 In the light of the current evidence, the late dating to the 1570s of much of Brandani’s sculpted output, including the Nativity, in recent years suggested by GENOVA 2015, is not persuasive, as eloquently argued by DELPRIORI 2017, pp. 114-115.

33 One more drawing traditionally associated with Prospero Fontana since GERE 1965 should be mentioned in this context. This is Virtue subduing Fortune, Julius III’s personal device, at the Royal collection (inv. RCIN 905990), an exact match with the stucco in Villa Giulia first attributed to Brandani by HOFFMANN 1967 Formerly attributed to Taddeo and to Giorgio Vasari, this remains an unusually polished drawing for Prospero. I wonder, if cautiously, if I should tentatively suggest that it be considered a worked-up modelletto of Prospero’s swift idea in Florence, Uffizi (inv. 109066 r.), by Brandani himself. I shall note that Serena Quagliaroli and Matteo Procaccini independently raised the same question (orally, January 2022).

Fig. 2: Here attributed to Giovanni Battista Lombardelli, details of Fig. 1

Figs. 3-4: Giovanni Battista Lombardelli, Scenes from the Life of St. Antony. Private collection

Fig. 5: Here attributed to Giovanni Battista Lombardelli, detail of Fig. 1

Fig. 6: Giovanni Battista Lombardelli, The Triumphs of Lucullus (detail) Madrid, Prado

Fig. 9: Here attributed to Giovanni Battista della Rovere, Cartouche design Oxford, Ashmolean Museum

Fig. 10: Giovanni Battista della Rovere, St Thomas doubting (detail) New York, The Morgan Library & Museum

Fig. 13: Federico Brandani, Project for the Chapel of the Duchy of Urbino in the Basilica of the Holy House of Loreto (detail). Oxford, Ashmolean Museum

Fig. 14: Taddeo or Federico Zuccaro, Study for the Assumption of the Virgin for the Pucci Chapel in the Santissima Trinità dei Monti, Rome. Private collection

Fig. 16: Federico Zuccaro, Study for the Assumption of the Virgin in the Basilica of the Holy House of Loreto Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Kupferstichkabinett

Fig. 19: Federico Brandani, Nativity. Urbino, Oratorio San Giuseppe, detail of the ceiling decoration

Fig 20: Here attributed to Federico Brandani, detail of Fig. 12 Fig. 21: Federico Brandani, Ceiling decoration. Urbino, Palazzo Ducale (from Palazzo Corboli Aquilini)

Fig. 22: Here attributed to Federico Brandani, detail of Fig. 12

Fig 23: Federico Brandani, Ceiling decoration Urbino, Palazzo Ducale (from Palazzo Corboli Aquilini)

AMADIO 2016

S. AMADIO, Il fregio nei palazzi romani del Cinquecento. Studi, progetti, modelli nella bottega, in Frises peintes. Les décors des villas et palais au Cinquecento. En hommage à Luigi De Cesaris et Julian Kliemann, international colloquium proceedings (Rome December 16-17, 2011), ed. by A. Fenech Kroke, A. Lemoine, Rome-Paris 2016, pp. 63-73.

AMADIO 2016(2017)

S. AMADIO, Allestire una parete: disegni per la decorazione ad affresco nei palazzi romani, in Palazzi del Cinquecento a Roma, special volume of «Bollettino d’Arte», ed. by C. Conforti, G. Sapori, 2016(2017), pp. 53-66.

BAGLIONE 1642

G. BAGLIONE, Le vite de’ pittori, scultori et architetti. Dal Pontificato di Gregorio XIII del 1572. In fino a’tempi di Papa Urbano Ottavo, Rome 1642.

BERTINI 1958

A. BERTINI, I disegni italiani della Biblioteca Reale di Torino, Turin 1958.

BORROMEO 1980

A. BORROMEO, Cesi Pier Donato, entry in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, XXIV, Rome 1980 (available on-line https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/pier-donato-cesi_(DizionarioBiografico)/).

CAPRICCIO E NATURA 2017

Capriccio e natura. Arte nelle Marche del secondo Cinquencento. Percorsi di rinascita, exhibition catalogue, ed. by A.M. Ambrosini Massari, A. Delpriori, Cinisello Balsamo 2017.

CLIFFORD–MALLET 1976

T. CLIFFORD, J.V.G. MALLET, Battista Franco as a Designer for Maiolica, «The Burlington Magazine», 879, 1976, pp. 387-410.

DELPRIORI 2017

A. DELPRIORI, “Fecerunt pictura et scultura”. Il percorso dell’arte nelle Marche picene nella seconda metà del Cinquecento, in CAPRICCIO E NATURA 2017, pp. 112-133.

GENOVA 2015

M. GENOVA, Ripensare Federico Brandani nell’Oratorio di San Giuseppe a Urbino, «Arte Marchigiana», 3, 2015, pp. 81-95

GERE 1963

J.A. GERE, Taddeo Zuccaro as a Designer for Maiolica, «The Burlington Magazine», 724, 1963, pp. 304, 306-315.

GERE 1965

J.A. GERE, The Decoration of the Villa Giulia, «The Burlington Magazine», 745, 1965, pp. 198207

On some late Renaissance ornament drawings at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford: Giovanni Battista Lombardelli, Avanzino Nucci, Giovanni Battista della Rovere and a proposal for Federico Brandani

GERE 1966

J.A. GERE, Two of Taddeo Zuccaro’s last commissions, completed by Federico Zuccaro I: The Pucci Chapel in S. Trinità dei Monti, «The Burlington Magazine», 759, 1966, pp. 286-293.

GERE 1969

J.A. GERE, Taddeo Zuccaro His Development Studied in His Drawings, London 1969.

G

ERE POUNCEY 1983

J.A. GERE, P. POUNCEY, Italian Drawings in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum, V. Artists Working in Rome: c. 1550 to c. 1640, 2 parts, London 1983.

GRISOLIA 2010

F. GRISOLIA, Per Giovan Battista Lombardelli, Pasquale Cati e Vespasiano Strada disegnatori, «Paragone Arte», s. 3, LXI, issue 92-93, 2010, pp. 3-39

HIBBARD 1964

H. HIBBARD, The Date of the Aldobrandini Lunettes, «The Burlington Magazine», 733, 1964, pp. 183-184.

HOFFMANN 1967

P. HOFFMANN, Pittori e stuccatori a Villa Giulia. Inediti di Federico Brandani, «Commentari», 1, 1967, pp. 48-66.

MACANDREW 1980

H. MACANDREW, Ashmolean Museum · Oxford. Catalogue of the Collection of Drawings, III. Italian Schools: Supplement, Oxford 1980.

MUNDY 2005

J. MUNDY, Additions to and Observations on Federico Zuccaro’s Drawings from the Critical 1560s, «Master Drawings», 2, 2005, pp. 160-185.

NICASTRO 2005

B. NICASTRO, Lombardelli Giovanni Battista, entry in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, LXV, Rome 2005 (available on-line https://www.treccani.it/enciclopedia/giovanni-battistalombardelli %28Dizionario-Biografico%29/).

NOCCHI 2015

L. NOCCHI, Gli scultori del cardinale Pier Donato Cesi (1570-1586): documenti ed ipotesi, «Bollettino d’Arte», s. 7, C, issue 25, 2015, pp. 77-96.

NOCCHI 2017a

L. NOCCHI, Il cardinale Pier Donato Cesi (1522-1586), in I Cesi di Acquasparta, la Dimora di Federico il Linceo e le Accademie in Umbria nell’età moderna, proceedings and new essays of the study meetings (Acquasparta September 26 - October 24, 2015), ed. by G. de Petra, P. Monacchia, Perugia 2017, pp. 243-259.

NOCCHI 2017b

L. NOCCHI, I soffitti a cassettoni nei palazzi della famiglia Cesi, «Opus Incertum», n.s., III, 2017, pp. 132-139.

PARKER 1956

K.T. PARKER, Catalogue of the Collection of Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum, II Italian Schools, Oxford 1956.

PROCACCINI 2019

M. PROCACCINI, Federico Brandani «eccellentissimo plasticatore»: tra l’Urbe, la Marca e il Ducato di Savoia, in «Quegli ornamenti più ricchi e più begli che si potesse fare nella difficultà di quell’arte». La decorazione a stucco a Roma tra Cinquecento e Seicento: modelli, influenze, fortuna, ed. by S. Quagliaroli, G. Spoltore, monographic issue of «Horti Hesperidum», 1, 2019, pp. 193-214, 326-335.

PROSPERI VALENTI RODINÒ 2007

S. PROSPERI VALENTI RODINÒ, I disegni del Codice Resta di Palermo, exhibition catalogue, Cinisello Balsamo 2007.

RIPA 1624-1625

C. RIPA, Della novissima iconologia […], I-III, Padua 1624-1625.

RUSSO 2015

A. RUSSO, Federico Zuccari and the chapel of the Dukes of Urbino at Loreto: the design for the altar of the Annunciation, «The Burlington Magazine», 1353, 2015, pp. 832-835.

SANTUCCI 2014

G. SANTUCCI, Federico Brandani’s paper model for the Chapel of the Dukes of Urbino at Loreto, «The Burlington Magazine», 1330, 2014, pp. 4-11.

SCHILLING 1971

E. SCHILLING, The German Drawings in the Collection of Her Majesty the Queen at Windsor Castle, London-New York 1971.

TOSINI 2011

P. TOSINI, Lombardelli, non Raffaellino: un disegno per palazzo Buzi a Orvieto, «Paragone. Arte», s. 3, LXII, issue 96, 2011, pp. 46-50.

TOSINI 2017

P. TOSINI, Dalle Marche a Roma e ritorno: percorsi incrociati di artisti nel secondo Cinquecento, in CAPRICCIO E NATURA 2017, pp. 17-26.

TOSINI 2018

P. TOSINI, In cerca di Diana. Il mito della dea nelle residenze del Lazio nel Cinquecento, in Il mito di Diana nella cultura delle corti Arte letteratura musica, conferences proceedings (Venaria Reale November 29 - December 1, 2010 and 2012), ed. by G. Barberi Squarotti, A. Colturato, C. Goria, Florence 2018, pp. 103-122.

TURNER 2004

N. TURNER, Dibujos italianos del siglo XVI, with the collaboration of J.M. Matilla, Madrid 2004.

VITZTHUM 1961

W. VITZTHUM, Aldo Bertini, I Disegni italiani della Biblioteca Reale di Torino, Rome, Istituto Poligrafico dello Stato, 1958. Pp. 86; 700 figs., «The Art Bulletin», 1, 1961, pp. 72-74.

L’articolo presenta un piccolo gruppo di disegni di tipo ornamentale del tardo Rinascimento dalla collezione dell’Ashmolean Museum di Oxford ancora anonimi o con attribuzioni problematiche. La selezione permette di toccare brevemente questioni metodologiche imposte da questa tipologia di disegno, che forse rimane ancora oggi la più elusiva per gli studiosi di grafica, per la genericità delle iconografie e per la ripetività degli schemi compositivi proposti. L’articolo si apre con un foglio di grande inventiva qui attribuito al marchigiano Giovan Battista Lombardelli, per passare poi ad Avanzino Nucci, un altro della folta schiera degli ‘artists working in Rome’, secondo la felice espressione coniata da Gere e Pouncey nel 1983, e a Giovan Battista della Rovere, a lungo confuso col Ricci da Novara, per chiudere con una proposta per un altro marchigiano, lo stuccatore Federico Brandani, qui rivelato per la prima volta come talentuoso disegnatore zuccaresco.

The article discusses a small group of ornament drawings from the late Renaissance from the collection of the Ashmloean Museum, Oxford, still anonymous or carrying problematic attributions. The selection briefly touches upon questions of methods related to what arguably remains the most elusive category drawing specialists still face today for the generic nature of their iconographies and for the repetitiveness of the compositional schemes. The article opens with an inventive sheet attributed to the Marchigian Giovan Battista Lombardelli to move onto another of the ‘artists working in Rome’, Avanzino Nucci, and to Giovanni Battista della Rovere, traditionally confused with Ricci da Novara. It concludes with a proposal for another Marchigian, the stuccoist Federico Brandani, here revealed for the first time as a skilled draughtsman under the spell of the Zuccari.

Introduzione

Nel settembre del 1858 Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle (1819-1897) e Charles Eastlake (1793-1865), primo direttore della National Gallery a Londra, viaggiarono insieme nel Centro Italia1. Sul tema ha scritto Donata Levi nella sua fondamentale monografia sul conoscitore italiano e negli atti del convegno dedicato a Giovanni Morelli e la cultura dei conoscitori2 . Sempre Levi, recensendo nel 2002 su «The Burlington Magazine» il volume di Jaynie Anderson su I Taccuini manoscritti di Giovanni Morelli3 , scriveva alcune righe molto lucide sulle prospettive che poteva aprire un confronto comparato dei taccuini di Eastlake e Cavalcaselle relativamente al viaggio del 1858:

A comparison between the contents of their notebooks shows such a quantity of common references that one can imagine the two connoisseurs talking together in front of the works of art, then writing down the results of their discussion, each following his own bent4

Da allora nulla è successo e un confronto di questo tipo è proprio ciò che si prefigge il presente lavoro Si tratta di definire meglio tempi e modi di un viaggio in comune che è stato sistematicamente sottovalutato rispetto all’impresa di Morelli e Cavalcaselle della primavera del 1861 per conto del governo italiano, ma che invece segna inequivocabilmente uno snodo fondamentale nell’attenzione della connoisseurship verso il patrimonio artistico di Marche, Umbria e Romagna5 Allo stesso tempo si mira anche a ricostruire, su base puramente indiziaria, quali possano essere stati i dialoghi condotti di fronte ai quadri a cui allude Levi Base fondamentale per una ricerca di questo tipo sono stati i taccuini dei due conoscitori, messi sistematicamente a confronto in un dialogo costante, al fine di evidenziare espressioni e immagini che denotano chiaramente uno scambio di opinioni sulle opere viste e analizzate. Nel dettaglio, ad esempio, se Eastlake e Cavalcaselle descrivono, ognuno con le proprie peculiarità, un polittico (valga come caso esemplificativo la Madonna della Rondine di Carlo Crivelli a Matelica)6 possiamo pensare che le rispettive, dettagliatissime analisi, siano avvenute in maniera indipendente; ma quando nelle rispettive descrizioni del medesimo polittico, nella Natività della predella entrambi ricordano un S Giuseppe con posa michelangiolesca piuttosto che le pieghe eseguite alla Dürer, è evidente che un dibattito c’è stato. Ho chiamato ‘markers’ quelle espressioni che denotano sui taccuini di entrambi una precedente interazione fra i due. Le schede delle opere contenenti ‘markers’ sono consultabili nell’Appendice documentaria. Si tratta, come comprensibile, di tracce che, sicuramente, non esauriscono lo spettro dei ragionamenti di Eastlake e Cavalcaselle. In un taccuino che nulla ha a che fare con il viaggio del 1858, di fronte al Cristo morto sorretto da due angeli di Giovanni Bellini della Gemäldegalerie, a Berlino (n. inv. 28), l’italiano scrisse: «Eastlake dice parte del quadro a Pesaro?»: il che denota che l’inglese ipotizzava che l’opera berlinese fosse la cimasa

1 Su Cavalcaselle si rimanda a LEVI 1988; su Eastlake, invece, a AVERY-QUASH–SHELDON 2011 e ROBERTSON 1978

2 LEVI 1988, pp. 134-139, e 1993

3 ANDERSON 2000

4 LEVI 2002

5 Sul viaggio di Morelli e Cavalcaselle nel 1861, oltre al già citato testo di Donata Levi, si vedano: il resoconto ufficiale, pubblicato a cura di Adolfo Venturi, (CAVALCASELLE–MORELLI 1896) e i taccuini di Morelli editi da Jaynie Anderson (ANDERSON 2000).

6 Cfr. Appendice documentaria al n. 6.

dell’Incoronazione della Vergine di Bellini che con grande pervicacia, ma inutilmente, cercò di comprare per la National Gallery7 Nei rispettivi taccuini marchigiani, di tutto ciò, non vi è alcuna traccia; eppure è molto probabile che la discussione sia avvenuta a Pesaro, davanti all’opera belliniana Lo scopo ultimo di questo lavoro, dunque, è di provare a ragionare sull’utilità di un viaggio eseguito in comune nel mondo dei conoscitori. A ben vedere, non si tratta certo dell’unico esempio, ma non mi pare che si sia mai riflettuto su questo aspetto Si è sempre dato per scontato, forse, che uno dei due partecipanti fosse, in qualche modo ‘il padrone di casa’ e che quindi facesse da guida all’altro, quando, nel caso specifico, è evidente che, almeno con riferimento a una parte delle Marche, si trattava per entrambi della prima visita in località particolarmente fuori mano Né si può dire che Eastlake non conoscesse l’italiano (lo scriveva e lo parlava correntemente) e Cavalcaselle sì (l’italiano scritto di Eastlake è molto più corretto di quello del conoscitore di Legnago). Insomma, vale la pena prendere in considerazione l’ipotesi che vedere insieme un’opera d’arte fosse un’occasione per mettere a fuoco meglio le caratteristiche tecniche, formali e conservative di un’opera d’arte tramite il confronto delle proprie idee con quelle del compagno di viaggio. Un momento di arricchimento, in definitiva; certamente non l’unico, considerato che scambi di opinione potevano essere svolti per lettera o in occasione di incontri, ma il più immediato perché eseguito direttamente di fronte ai quadri. Nel caso specifico di Eastlake e Cavalcaselle è noto che i due si conoscevano almeno dal 1853. Il viaggio qui in esame documenta il periodo più lungo, a nostra conoscenza, in cui i due si trovarono a condividere le loro personali esperienze faccia a faccia8 .

I taccuini

Il 9 settembre 1858 Charles Eastlake scriveva da Firenze a Ralph Wornum (1812-1877), all’epoca segretario e Keeper della National Gallery:

Tomorrow I start for a tour through some out of the way parts of the Papal States, preparing to return here in about a fortnight […] Lady Eastlake does not accompany me in my intended tour, but perhaps Cavalcaselle will, if he can get his passport in order9

E circa quindici giorni dopo, Lady Eastlake (1809-1893) spediva una lettera all’amica Sara Austen, aggiungendo10 :

7 Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana Venezia, Fondo Cavalcaselle, Ms. It , IV, 2037(=12278), tacc. XV, f. 88r La cimasa originale si trova invece ai Musei Vaticani (MV.40290.0.0)

8 Incontri fra Cavalcaselle e Eastlake sono testimoniati da documenti scritti nel settembre 1857 a Padova (cfr. LEVI 1988, pp. 109-110) e nel maggio 1863 a Londra (cfr. AVERY-QUASH–MAZZAFERRO 2021, poi tradotto in italiano in MAZZAFERRO–AVERY-QUASH 2020(2022), lettera di Eastlake a Michelangelo Gualandi del 25 maggio 1863), ma è ovvio che dovettero essere molti di più

9 National Gallery Archive 02/3/3/44.

10 Lettera da Firenze, 26 settembre 1858, in THE LETTERS OF ELIZABETH RIGBY 2009, pp. 183-184. Sara Austen (1793-1867) fu scrittrice, linguista e traduttrice di testi dal tedesco all’inglese. Era zia di Austen Henry Layard (1817-1894), archeologo la cui fama fu legata inizialmente ai rilievi condotti sulla città di Ninive negli anni Quaranta. Layard, che ebbe anche una carriera politica, col passare degli anni coltivò sempre più i suoi interessi artistici, divenendo anche famoso collezionista. Fece parte della società che, nel 1857, strinse un contratto con Cavalcaselle per inviarlo in Italia in cerca di materiali per una nuova edizione inglese delle Vite di Giorgio Vasari. Alla morte di Eastlake (24 dicembre 1865) fu uno dei candidati alla direzione della National Gallery, salvo dover rinunciare per incompatibilità della carica col suo ruolo di parlamentare. Proprio la morte di Eastlake sembra una sorta di spartiacque nei rapporti fra Layard e Cavalcaselle, che andarono man mano deteriorandosi successivamente. Su Layard collezionista si veda RIVA 2019

Sir Chas having left me just a fortnight ago for a round of remote places which he kindly judged would be too rough for me. In some places he is following Layard’s steps of the summer before last […] He has our invaluable manservant with him and also a Signor Cavalcaselle of whom Layard knows, so that he is not without care & kind companions.

Il resoconto del viaggio è testimoniato rispettivamente dai taccuini 18 (da carta 14r alla fine), 19 e 20 (fino al f. 10v) dell’inglese, conservati presso la National Gallery11 , e dal taccuino XII, Ms. It., IV, 2037(=12278) dell’italiano, custodito nella Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana di Venezia12 . Per quanto concerne il quaderno cavalcaselliano, occorre sottolineare che va consultato alla rovescia: la numerazione moderna non segue, infatti, quella originaria apposta dal conoscitore italiano; se si ribalta il taccuino ci si accorgerà immediatamente che le carte da 58v a 14v (numerazione moderna) corrispondono in maniera pressoché identica all’itinerario di Eastlake (la numerazione di Cavalcaselle va, in realtà, da 19r a 56r)13

L’itinerario del viaggio fu il seguente (si usano le denominazioni moderne): Sargiano, Castiglione Fiorentino, Cortona, Passignano, Perugia, Gubbio, Gualdo Tadino. Nocera Umbra, Fabriano, Matelica, Sanseverino Marche, Tolentino, Macerata, San Ginesio, Sarnano, Falerone, Massa Fermana, Montegiorgio, Fermo, Sant’Elpidio a Mare, Monte San Giusto, Recanati, Loreto, Ancona, Jesi, Senigallia, Fano, Pesaro, Urbino, nuovamente Pesaro, Rimini, Santarcangelo di Romagna, Cesena, Forlì e Faenza. Da Faenza (visitata credibilmente attorno al 30 settembre) Eastlake tornò a Firenze. Nel suo diario personale, Lady Eastlake scrisse l’11 ottobre, di essere a Roma col marito, di essere partita l’8 da Firenze e di aver visitato, prima della partenza, Settignano: «Cavalcaselle was with us»14 È quindi probabile che anche l’italiano sia rientrato da Faenza a Firenze col direttore della National Gallery. Effettuare un confronto puntuale fra i quaderni di Eastlake e quelli di Cavalcaselle è divenuto enormemente più facile negli ultimi anni: i primi sono stati editi nel 2011 dalla Walpole Society, a cura di Susanna Avery-Quash15; i secondi sono disponibili integralmente on-line dal 201916 . Ciò non toglie, ovviamente, che ci siano avvertenze e criticità di cui tener conto. In primo luogo, bisogna sempre aver ben presente che i taccuini non sono inventari o repertori, in cui si scrive tutto; è necessario, insomma, ricordarsi che i due conoscitori videro molto di più, e molto decisero di non prendere in considerazione. Non tennero in nessun conto, ad esempio, le opere eseguite, grosso modo, dopo il 1550. La circostanza si spiega perfettamente coi loro incarichi: il direttore cercava quadri di Old Masters per la National 11 AVERY-QUASH 2011. 12 Sulla storia del fondo si veda MARCON 2021 13 Non si tratta di un errore. Il taccuino (così come molti altri) ha due ‘inizi’, sia da una parte che dall’altra. L’archivista l’ha numerato dal lato che contiene, sul frontespizio, un’etichetta incollata con grafia di Cavalcaselle e la lista delle località visitate. Il bibliotecario, inoltre, non poteva tener conto della numerazione originale per la presenza di fogli inseriti successivamente, fuori numerazione, e l’assenza di altri, spostati evidentemente dallo stesso conoscitore in altri quaderni. Né, nella numerazione cavalcaselliana, mancano stranezze. Provo a indicarle: manca la p 26r-v, in coincidenza di Matelica; non sono riuscito a trovarla altrove e l’assoluta coerenza dei materiali fa pensare a un errore di numerazione piuttosto che a uno spostamento successivo. C’è una pagina priva di numerazione fra la 34 e la 35; anche qui, la totale continuità con quanto disegnato prima e dopo induce a credere a una dimenticanza più che a un inserimento posteriore (l’ho numerata 34bis); idem fra 35 e 36 (inserita nella numerazione una 35bis). Manca la pagina 44 che però, grazie a Susy Marcon (che ringrazio), ho rintracciato in Ms. It , IV, 2041(=12282), fasc III, f. 45r-v (quindi, spostata da Cavalcaselle nei materiali per la redazione della Storia dell’arte italiana). Manca anche la pagina 50, che dovrebbe contenere indicazioni su Urbino e Pesaro; purtroppo non sono riuscito a rintracciarla. Un paio di dipinti, infine, sono disegnati, fuori ordine, a p. 61 (numerazione Cavalcaselle).

14 JOURNALS AND CORRESPONDENCE 1895, II, pp. 104-105.

15 AVERY-QUASH 2011.

16 Consultabili su http://fondocavalcaselle.venezia.sbn.it

Gallery17, mentre Cavalcaselle, come vedremo, era impegnato in ricerche per la redazione di una nuova edizione delle Vite del Vasari. La circostanza è comunque espressione di un gusto personale e di un’epoca in cui tutto ciò che viene dopo gli allievi di Raffaello è da considerare espressione di decadenza. Ma nei taccuini non si trovano nemmeno le indicazioni di un numero imprecisato di opere antiche non considerate evidentemente degne di menzione Un esempio: a Gubbio, Eastlake non citò la collezione del conte Beni. Eppure, il 15 aprile 1861, all’agente Michelangelo Gualandi che gli aveva scritto segnalandogliela, rispose: «Conosco la “Galleria” del Conte Bene [sic] in Gubbio e La prego di non darsi la pena di mandarmene una descrizione. Il Conte è un’ottima persona e mio buon’amico [sic], ma i suoi quadri, quantunque pregevoli, non sono per me»18

Da un punto di vista metodologico, poi, è imprescindibile ricordare (semplificando estremamente le cose) che Eastlake scriveva annotazioni e usava piccoli (ma numerosi) schizzi all’interno del testo, mentre Cavalcaselle procedeva in maniera differente: partiva dai disegni dell’opera, con diversi livelli di analiticità, e operava annotazioni direttamente su questi. Non mancava quasi mai, a dire il vero, un riepilogo a latere, spesso redatto a uso e consumo di Joseph Archer Crowe, (1824-1896), storico sodale di studi e pubblicazioni19 , ma è evidente che mentre Eastlake ‘traduceva’ in parole ciò che vedeva, l’italiano prendeva appunti con i suoi schizzi, limitando l’uso della parola e rinunciando quasi completamente a qualsiasi forma narrativa. La descrizione dell’Incoronazione della Vergine belliniana, ad esempio, porta via al direttore della National Gallery sei fogli di testo, mentre a Cavalcaselle tre fogli di figure20 così suddivisi: nel primo sono disegnati la parte centrale della pala e i santi delle colonne laterali; nel secondo gli scomparti della predella; il terzo contiene particolari di volti, mani e piedi del Cristo e della Madonna. Naturalmente ogni disegno è ricchissimo di annotazioni. Preso atto di tali differenze, per operare un paragone fra i due conoscitori è necessario rendere i documenti confrontabili: l’operazione non è sempre semplicissima e comporta comunque la perdita dell’immediatezza visiva dei disegni. Le note di Eastlake hanno una loro riconoscibile ‘struttura narrativa’, in cui si distinguono sempre un inizio, uno svolgimento e una fine; nel caso di Cavalcaselle, invece, l’esame del disegno (e quindi delle relative note) può partire da un qualsiasi punto della pagina, a seconda dei propri interessi21 . Per questo motivo, comparando le due versioni, sono partito sempre da quella di Eastlake, sfruttandone lo svolgimento lineare e consecutivo, e ho ‘destrutturato’ le note di Cavalcaselle in maniera tale da seguire, finché possibile, lo stesso ordine.

Inoltre, è necessario evidenziare un’ulteriore differenza strutturale e metodologica. Eastlake seguiva un andamento cronologico nelle sue descrizioni e se, in anni successivi, tornava a visitare una località, faceva rimandi ai vecchi taccuini, ma non vi scriveva sopra, usandone sempre di nuovi L’italiano, invece, usava i suoi disegni come se fossero un palinsesto su cui scrivere note in occasione di visite posteriori, in anni successivi, generando una sedimentazione di materiali di cui difficilmente siamo in grado di risalire all’ordine e alla data di stesura22 I manoscritti di Cavalcaselle, insomma, vanno letti tutti con estremo scrupolo filologico per coglierne la complessità delle associazioni di idee. Un caso molto semplice a

17 La riforma della National Gallery (1855), con cui venivano istituite le cariche di direttore (Eastlake) e Travelling Agent (Mündler), stabiliva anche che la galleria dovesse essere trasformata in una collezione che mostrasse al pubblico l’evolversi della storia della pittura occidentale dalle sue origini. Particolarmente evidenti erano le lacune per i cosiddetti ‘primitivi’ e fu lì che Eastlake concentrò la sua attenzione

18 MAZZAFERRO 2021, in particolare p. 217.

19 Sui rapporti fra Cavalcaselle e Crowe molto si è scritto. Oltre a LEVI 1988 ricordo, in precedenza, LEVI 1981 e, recentemente, FRATICELLI 2018 e 2020 e LEVI 2021

20 Cfr. Appendice documentaria al n. 33.

21 Sulla differenza metodologica fra i taccuini di Cavalcaselle e quelli di Eastlake si veda PELLEGRINI 2021, in particolare pp. 231-234.

22 Come evidenziato in LEVI 1988, passim

titolo di esempio. Nella pagina dedicata alla Madonna della Rondine di Matelica troviamo l’indicazione «60.000 Lire»23 : possiamo ritenerla certamente una nota posteriore, trattandosi del valore che Morelli e Cavalcaselle attribuirono alla pala il 17 maggio 1861, apponendovi il regio sigillo perché l’opera fosse sottoposta a tutela pubblica24 Ma anche una nota in alto a sinistra pone una serie di problemi: «vedi Labouchere, Beaucousin, Mantegna?»25

A essere citate sono le collezioni di Henry Labouchere, barone Taunton (1798-1869), e quella del francese Edmond Beacousin (1806-1866) È possibile ritenere che la redazione della nota sia coeva a quella del disegno (1858)? Sì, se si tiene conto, attingendo ad altri quaderni disponibili nel fondo, che Cavalcaselle aveva già visto entrambe le collezioni. In particolare, il motivo della Vergine con Bambino, isolati su un trono, potrebbe ricordare a Cavalcaselle il podio litico su cui stazionano entrambi nella Madonna di Manchester all’epoca in collezione Labouchere, vista dal legnaghese almeno nella Manchester Art Treasures Exhibition del 185726 Allo stesso modo il ‘Mantegna’ (accompagnato da un punto interrogativo, a indicare l’incertezza di Cavalcaselle sulla correttezza dell’attribuzione) potrebbe indicare il Noli me Tangere in quegli anni a Parigi presso Edmond Beaucousin. Cavalcaselle visitò la collezione quasi certamente già nel 1852. Il quadro fu venduto a Eastlake per la National Gallery nel gennaio 1860 e si trova ancor oggi presso il museo londinese con segnatura NG639 e attribuzione a un imitatore di Mantegna. Le mani delle dita del Cristo, affusolate e lunghe, potrebbero esser state poste in relazione con quelle dei personaggi della Madonna della Rondine. Possibile, dunque, che la nota del legnaghese sia coeva alla stesura del disegno; nulla esclude, tuttavia, che la nota sia frutto di una riflessione successiva. Nella ridefinizione delle stesure a volte può essere d’aiuto la diversità degli inchiostri, oppure una (relativa) differenza delle grafie (quella degli anni a partire dal 1865 è, in genere, meno controllata, più ampia e sciolta), ma non sempre è possibile ottenere risposte certe e inconfutabili. A Perugia, sotto il disegno della Madonna Conestabile, si legge ad esempio, su un’unica riga e con grafia identica: «si direbbe del tempo dello stendardo di Città di Castello [n.d.r. quindi della giovinezza di Raffaello] – ora penso fatto in seguito»27 . È evidente che quell’«ora» ci permette di capire che si tratta non di una, ma di due notazioni affiancate, ma non siamo in grado di datarle, e sarebbe importante, perché presumono un cambiamento nell’inquadramento dell’opera nell’ambito della biografia raffaellesca. Costruire cronologie di opere fra loro confrontabili per motivi stilistici, stabilire relazioni con opere di altri pittori, creare delle proprie mappe concettuali, libere di essere riviste nel corso degli anni, sono operazioni che Cavalcaselle conduce direttamente sui taccuini, costringendoci ad acrobazie fra un quaderno e l’altro. La diretta conseguenza di tutto ciò è che, rispetto a Eastlake, le notazioni dell’italiano sono molto più ricche di rimandi ad altri artisti o ad altre opere; non vi è dubbio che si tratti di una cifra propria dell’italiano, ma il fenomeno è enormemente accentuato dagli apporti posteriori alla stesura originale. Non è corretto, a mio avviso, dire che Eastlake non avesse analoghe esigenze e attitudini; semplicemente non le rendeva esplicite (o lo faceva in maniera molto inferiore) nei suoi taccuini.

23 Cfr. Appendice documentaria al n. 6.

24 CAVALCASELLE–MORELLI 1896, pp. 325-326, e ANDERSON 2000, p. 134.

25 Cfr. Appendice documentaria al n. 6.

26 Cavalcaselle aveva comunque già visitato la collezione di Henry Labouchere, nobile e politico inglese, almeno nel luglio 1854, data segnata in un disegno custodito nel taccuino XIV del Ms It , IV, 2037, f 142r

27 Cavalcaselle: tacc. XII, f. 55v numerazione moderna; f. 21r num. Cavalcaselle. Il 15 dicembre 1858 il conte Giovan Carlo Conestabile (1824-1877) scrisse a Austen Layard confermando di aver incontrato Cavalcaselle due volte dalla partenza dell’inglese da Perugia. Tale partenza va collocata nel 1856. Le affermazioni di Conestabile confermano l’evidenza della stesura in due diversi momenti del commento sotto al disegno realizzato nel taccuino

Il viaggio: tempistica, organizzazione, scopi

Il corposo elenco delle località che Eastlake e Cavalcaselle visitarono stupisce soprattutto se messo in relazione alle tempistiche di svolgimento, circoscrivibili tra l’11 e il 30 settembre, ossia appena venti giorni, in epoche in cui i mezzi di trasporto e le strade non permettevano certamente viaggi veloci Possiamo immaginare spostamenti frenetici, in giornate in cui le ore di luce dovevano essere una dozzina, rendendo necessarie levatacce mattutine e lunghe e sfiancanti tappe di trasferimento a bordo di carrozze di posta certamente poco confortevoli. Certamente lo strano terzetto (un distinto Sir inglese di sessantacinque anni, Nicholas Tucker, suo fedele servitore, e un bizzarro signore italiano sulla quarantina che parlava con forte inflessione veneta) non passò inosservato arrivando in paesini come San Ginesio, che contavano poche centinaia di abitanti. I contrattempi non dovettero mancare; possiamo presumere che Eastlake e Cavalcaselle, ad esempio, abbiano dovuto adattarsi e aspettare che, specie nei giorni festivi, finissero le funzioni religiose per poter vedere le opere nelle chiese; a Loreto, sicuramente, non ebbero modo di vedere gli affreschi di Melozzo nella Cappella del Tesoro perché erano assenti il Delegato, il Custode e il Sindaco, unici a poter autorizzare la visita28 . E non dev’esser stato facile convincere parroci o monaci a spostare arredi sacri, candele, decorazioni floreali per prendere le misure delle opere o vederle da vicino (sono citate spesso le occasioni in cui si fa uso di una scala; per le osservazioni da lontano è invece d’obbligo l’uso del cannocchiale). C’è da chiedersi come tutto ciò sia stato possibile. Sicuramente i due avevano nelle loro mani il primo volume della quarta edizione dell’Handbook for Travellers in Central Italy, dedicato alla Toscana meridionale e allo Stato Pontificio, esclusa Roma, e pubblicato nel 185729 . Troppo spesso si trascura l’importanza delle guide edite dall’inglese John Murray; a parte le indicazioni artistiche (comunque non trascurabili) erano indispensabili soprattutto da un punto di vista logistico, indicando locande in cui soggiornare, tempi di percorrenza da una località all’altra, possibili itinerari, mezzi di trasporto. Nel caso specifico, tuttavia, l’importanza della guida dev’essere stata piuttosto limitata, considerando che anche la quarta edizione, di fatto, non presentava alcuna indicazione relativamente al fermano, al maceratese e alle aree limitrofe. È ragionevole pensare che quando Eastlake scriveva a Wornum (come abbiamo visto) di essere in procinto di recarsi in «some out of the way parts of the Papal States»30 si riferisse proprio al fatto che erano così fuori mano da non comparire nemmeno nella guida di Murray. È molto probabile, invece, che nell’organizzazione del viaggio abbiano avuto un peso importante le indicazioni di Austen Henry Layard, come si evince dall’accenno di Lady Eastlake nella sua missiva a Mrs Austen31 e, soprattutto, di Otto Mündler (1811-1870). Famosissimo conoscitore, figura di spicco nel mercato europeo dell’arte, Mündler era stato nelle Marche e in Umbria proprio fra aprile e giugno del 1858, in qualità di Travelling Agent della National Gallery, carica che ricopriva dal 1855 A essere precisi, Eastlake, insediatosi come primo Direttore proprio in quell’anno, aveva accettato l’incarico pretendendo che, contemporaneamente, fosse istituita la figura del Travelling Agent, destinato a girare in tutta Europa (e in particolare in Italia) in cerca di occasioni di acquisto su cui relazionargli È legittimo ipotizzare, dunque, che la presenza di Mündler in quelle zone, qualche mese prima, fosse in preparazione del viaggio che l’agente avrebbe dovuto compiere con Eastlake durante

28 Eastlake: tacc. 19, f. 12r-v; Cavalcaselle: tacc. XII, ff. 32v-33r numerazione moderna; ff. 39v-40r num. Cavalcaselle

29 A HANDBOOK FOR TRAVELLERS IN CENTRAL ITALY 1857 Cavalcaselle ne cita esplicitamente una pagina a Fabriano: Cavalcaselle: tacc. XII, f. 52r numerazione moderna; f. 24v num. Cavalcaselle Esempi di utilizzo dei manuali di Murray da parte del legnaghese sono reperibili in molti quaderni, dalla Spagna alla Germania e, naturalmente, all’Italia.

30 Cfr. supra, nota 9

31 Cfr. supra, nota 10

l’estate. Il 13 luglio 1858, però, il Parlamento inglese decise la cancellazione della carica di Travelling Agent e Mündler si trovò esautorato. Si trattava di una decisione motivata in maniera pretestuosa, ma fondamentalmente da spiegarsi col fatto che Mündler era tedesco, medesima nazionalità del Principe Albert, consorte della Regina Vittoria: da anni ogni presenza tedesca in Gran Bretagna era vista come il tentativo di stabilire un’egemonia culturale di lingua germanica oltre Manica32 Per il partito antitedesco era stata del resto uno smacco la stessa organizzazione della Art Treasures Exhibition di Manchester del 1857, non tanto perché patrocinata dai reali, ma perché sin dal titolo si richiamava ai tre volumi pubblicati nel 1854 dal celebre storico tedesco Gustav Waagen (1794-1868), i Treasures of Art in Great Britain33 Lo stesso Waagen si era speso personalmente in sede di organizzazione, non solo in consulenze, ma anche cercando di convincere i proprietari delle opere più significative a prestarle ai promotori34 Da non dimenticare poi che il segretario della mostra era stato George Scharf jr (1820-1895), inglese sì, ma figlio di un immigrato tedesco e da maggio 1857 anche direttore della National Portrait Gallery35 Insomma, ragionando secondo una logica ‘nazionalistica’, era chiaro che bisognava porre un freno all’avanzare dell’influenza tedesca sui centri di potere della politica artistica inglese e Mündler fu il classico esempio di capro espiatorio.

È a questo punto che deve essere entrata in gioco la presenza di Cavalcaselle. Eastlake non potendo partire con Mündler, fece certamente tesoro di tutte le indicazioni fornitegli e chiese all’italiano, delle cui capacità di conoscitore e di ricercatore aveva un’altissima opinione, di accompagnarlo36 . In una lettera all’erudito bolognese Michelangelo Gualandi di qualche anno dopo lo definì uomo «che tutto vede», quasi a riconoscergli una sorta di supremazia nella connoisseurship tutt’altro che scontata37 . Stando a quanto scrive Crowe, il neodirettore della National Gallery, nel 1855, aveva valutato inizialmente l’ipotesi di far nominare proprio l’italiano come Travelling Agent, dovendo rinunciare per i problemi con la giustizia che quest’ultimo aveva nella nostra penisola dai tempi dei moti del 1848-184938. Se così fu, Eastlake fu uomo fortunato: la storia precedente e quella successiva di Cavalcaselle dimostrano che quest’ultimo non aveva la benché minima idea di come si conducesse una trattativa di mercato39. Forse nel 1852 il suo viaggio in Francia e in Spagna fu finanziato dall’allora famoso tenore Mario (al secolo Giovanni Matteo De Candia) perché acquistasse quadri per la sua collezione40 Ammesso che le cose stessero in questo modo, si dovette trattare di un disastro, perché non risulta che Cavalcaselle abbia mai comprato un qualsiasi quadro per il cantante lirico

Eastlake, negli anni in cui l’italiano era stato a Londra, aveva senza dubbio avuto modo di apprezzare e aiutare economicamente Cavalcaselle Anche se le carte d’archivio oggi disponibili non permettono di parlare di confisca dei beni subita da parte degli austriaci, è

32 THE TRAVEL DIARIES 1985, pp. 34-38.

33 WAAGEN 1854

34 PERGAM 2016.

35 PERGAM 2016

36 In anni successivi, una volta calmatesi le acque, Eastlake non esitò a farsi accompagnare nei suoi viaggi da Mündler, impiegato naturalmente a titolo privato.

37 Lettera da Charles Eastlake a Gualandi del 25 maggio 1863 in AVERY-QUASH–MAZZAFERRO 2021

38 CROWE 1895, pp. 236-237.

39 Olga Piccolo ha di recente esaminato i rapporti tra Cavalcaselle ed Eastlake con riferimento specifico ai dipinti veneti e ‘veneto-bergamaschi’ (cfr. PICCOLO 2020). Anche se nel titolo del suo saggio l’autrice parla dell’italiano come ‘agente’ dell’inglese, è immediatamente chiaro che pensa più a un ruolo di consulenza attribuzionistica che alla conduzione di trattative economiche vere e proprie. Credo peraltro che le «diverse stime valutative per conto del direttore inglese» (ivi, p. 125) a cui fa riferimento a proposito del viaggio oggetto di questo saggio siano in realtà successive, ossia – come detto – siano le stime date ai quadri nel 1861 da Cavalcaselle e Morelli, e riportate nel taccuino in tale occasione. Nel caso specifico, insomma, a Piccolo sfugge che il taccuino è un palinsesto

40 LEVI 1988, p. 35.

chiaro che la situazione finanziaria del legnaghese era drammatica41 . Nell’agosto del 1857 l’erudito di Legnago tornò in Italia, probabilmente grazie alle amnistie concesse dall’Impero austro-ungarico in gennaio-marzo42 ; si era legato contrattualmente a una società composta da John Murray, Tom Taylor, Austen Henry Layard e dallo stesso Eastlake, impegnandosi a redigere una nuova edizione commentata delle Vite di Vasari43. Lo attendeva una lunga e costosa serie di viaggi in giro per l’Italia che lo avrebbe assorbito negli anni successivi; tanto costosa che, quando Eastlake gli propose di accompagnarlo nelle Marche nel 1858, evidentemente accettò senza problemi: poteva continuare i suoi studi usufruendo del parere di un conoscitore come l’inglese e fruire di una somma extra da parte del direttore della National Gallery che, in situazioni simili, non esitava a pagare di tasca propria44 È totalmente da escludere l’ipotesi che Cavalcaselle – quel Cavalcaselle che Roberto Longhi caratterizzò come uomo probo e onesto in contrapposizione a Morelli, compromesso col mercato45 – non conoscesse gli intenti commerciali del viaggio di Eastlake, in cerca di opere meritevoli di entrare nella collezione della National Gallery Le trattative poste in essere dall’inglese nel corso del suo viaggio umbro-marchigiano sono riassunte dallo stesso direttore nel suo annuale report ai trustees del museo, presentato il 27 novembre 185846 . Si apprende così che Eastlake fece un’offerta a Cortona per una Madonna che allatta il Bambino attribuita a Fra Bartolomeo, cercò di comprare inutilmente due tavole con santi di Fiorenzo di Lorenzo a Perugia; a Gubbio, Fabriano, Tolentino e Macerata vide opere dei due Crivelli, di Lorenzo Lotto e di altri artisti, tutte non acquistabili perché proprietà ecclesiastiche; a Fano giudicò non degna di attenzione la Sacra Conservazione di Giovanni Santi (oggi nella locale pinacoteca), potenzialmente sul mercato; a Pesaro analizzò con estrema attenzione l’Incoronazione della Vergine di Bellini, valutandola 5000 sterline; a Cesena scartò una Presentazione al Tempio di Francesco Francia perché non di primo livello; a Forlì passò in rassegna tutti i Palmezzano che riuscì a vedere per porli in relazione con la lunetta dell’artista che si apprestava a comprare a Roma, a Faenza acquistò da Achille Farina, professore dell’Accademia di Belle Arti di Bologna e mercante, la Madonna del Prato, di attribuzione dubbia fra Giovanni Bellini e Basaiti47 . I risultati del viaggio, peraltro, non possono essere valutati tenendo conto solamente dei suoi esiti immediati. Eastlake era perfettamente consapevole che vedere un’opera poneva i presupposti per acquistarla nel caso in cui, per le circostanze più disparate, fosse stata immessa

41 Molto interessanti su questo punto gli studi di Giacomo Girardi, che ha recuperato i documenti relativi ai sequestri austriaci degli esiliati veneti e alla restituzione degli stessi beni in seguito all’amnistia del 1857. Secondo queste carte Cavalcaselle non risulta essere fra gli esiliati, né, tanto meno, fra i confiscati e gli amnistiati. Ciò non inficia la realtà, ovvero che Giovan Battista fosse scappato per motivi politici La situazione, insomma, attende ancora di essere chiarita e, personalmente, le uniche spiegazioni che riesco a darmi al momento sono l’asportazione successiva del dossier Cavalcaselle dalle carte austriache o l’incompletezza delle medesime. Cfr. GIRARDI 2018

42 L’ipotesi è mia e non è corroborata da documenti Sul rientro di Cavalcaselle in Italia sono state fatte varie ipotesi: sin dal 1973 Moretti (G.B. CAVALCASELLE 1973, p. 18) parla di un intervento diretto di Eastlake A me la circostanza pare assai probabile, soprattutto tenendo conto che nel 1859, quando la polizia borbonica gli impedì di entrare nel Regno delle Due Sicilie, Cavalcaselle scrisse proprio a Eastlake chiedendo di intervenire per via diplomatica: cfr. Ms. Cod. It, IV, 2035, fasc III, Epistole 1-50, 1 (minuta di lettera del 13 agosto 1859). Nel caso specifico del Lombardo-Veneto, tuttavia, mi sembra logico pensare che un eventuale interessamento di Eastlake – ossia, in via mediata, del governo inglese – presso le autorità locali possa essere stato senza dubbio agevolato dalle amnistie concesse dopo la visita di Francesco Giuseppe a Venezia e a Milano fra gennaio e marzo del 1857.

43 Sulle motivazioni che portarono al progetto di una nuova edizione inglese delle Vite vasariane a solo sette anni di distanza dalla precedente si veda LEVI 1988, in particolare pp. 77-83.

44 AVERY-QUASH–MAZZAFERRO 2021 Si vedano i casi di pagamenti allo stesso Gualandi e al ferrarese Cittadella.

45 AGOSTI 1998

46 AVERY-QUASH 2011, II, pp. 115-116.

47 Il Palmezzano comprato a Roma è alla National Gallery con segnatura NG 596; presso il museo inglese anche la Madonna del Prato, segnata NG 599.

sul mercato in un momento successivo. È così che le trattative per l’Incoronazione della Vergine pesarese partirono nel 1862, quando Luigetto Giorgi, rigattiere e mercante di quadri (lo stesso che fece da guida al direttore e a Cavalcaselle nella visita a Pesaro il 25 settembre 1858, come risulta da una nota nel taccuino di quest’ultimo)48, gli fece sapere che il Comune aveva deciso di vendere l’opera per risanare la drammatica situazione debitoria dell’amministrazione; andarono avanti anche dopo la morte di Eastlake (24 dicembre 1865), coinvolgendo il suo successore, William Boxall (1800-1879) e il bolognese Michelangelo Gualandi (1793-1887), ma senza frutto49. Nel 1862, invece, Eastlake mise a segno un colpo a suo favore, riuscendo ad acquistare per il museo che dirigeva la Madonna della Rondine di Carlo Crivelli che aveva visto per la prima volta a Matelica proprio in compagnia di Cavalcaselle. Ben note sono le vicissitudini legali legate a questo episodio50

I taccuini di Eastlake, peraltro, contengono riflessioni relative a problemi legati al possibile acquisto delle opere, che sono già state approfondite in altre occasioni. A Perugia, ad esempio, davanti alla Pala di S. Onofrio di Luca Signorelli l’inglese scrisse che «the Volterra Signorelli» (ossia l’Annunciazione, oggi presso la Pinacoteca volterrana) era «preferable on the whole (for the English public)» rispetto a quella umbra, e sicuramente pensava ai nudi di S. Onofrio e dell’angelo musicante, che avrebbero potuto turbare il senso del decoro del pubblico britannico di età vittoriana51 . Molte delle segnalazioni di ‘difetti’ nelle opere sono accompagnate da considerazioni sulla possibilità di porvi più o meno facilmente rimedio, il che tradisce un’idea di restauro che era ben diversa rispetto a quella di Cavalcaselle, contrario a interventi di pennello in generale, ma si spiega con il desiderio di presentare al pubblico quadri ‘esemplari’ delle scuole italiane52 .

Le Marche

La comparazione dei taccuini di Eastlake e Cavalcaselle mostra discontinuità all’inizio e alla fine dell’itinerario: Eastlake riporta diverse, rapide note su opere perugine a cui Cavalcaselle non fa cenno alcuno; di Gubbio, poi, l’italiano non parla proprio; in maniera analoga, a Forlì l’inglese passa in rassegna in maniera molto rapida, ma sostanzialmente completa, le opere di Palmezzano, che Cavalcaselle sembra trascurare Eppure un anno prima, a Manchester, l’italiano le aveva studiate con grande attenzione. Al netto di perdite o spostamenti di fogli nel quaderno, si tratta di elementi che si spiegano, a mio avviso, con il fatto che l’erudito di Legnago aveva già visitato quelle località, aveva già tracciato i suoi disegni e, quindi, procedeva con il suo classico metodo, aggiungendo note a schizzi fatti in anni precedenti, senza ridisegnare nuovamente le opere. Purtroppo, dimostrarlo non è semplice, ma le pagine dedicate a Perugia e Gubbio in altri taccuini, di fatto, coprono tutto quanto visto nel corso del 1858 e sono quindi da giudicarsi probabilmente precedenti al settembre di quell’anno. Eastlake, invece, come detto, seguiva un ordine cronologico; era già stato a Perugia e le sue annotazioni sono separate rispetto alle precedenti, pur richiamandole A ogni modo, nei loro quaderni i due conoscitori citano complessivamente 165 opere, 99 delle quali sono ricordate da entrambi. Le mancate citazioni comuni sono quasi tutte collocabili a Perugia, Gubbio e Forlì. Se si considerano solo le opere d’arte marchigiane la cifra complessiva scende a 88, di cui 73 prese in esame sia da Eastlake sia da Cavalcaselle; da tenere presente, peraltro,

48 Cavalcaselle: tacc. XII, f. 23v numerazione moderna; f. 48r num. Cavalcaselle.

49 Si veda l’Appendice II, Summary of Correspondence of Michelangelo Gualandi with Transcribed Excerpts from the Original Texts in AVERY-QUASH–MAZZAFERRO 2021: lettera di Eastlake a Gualandi del 30 gennaio 1862 e sgg

50 GENNARI SANTORI 1998, in particolare pp. 298-304.

51 Eastlake: tacc. 18, f. 17r.

52 Su questi temi si rimanda a AVERY-QUASH–SHELDON 2011 e HAYES 2021, in particolare pp. 79-113

sguardo condiviso: il viaggio di Giovan Battista Cavalcaselle e Charles Eastlake nel Centro Italia (settembre 1858)

che in corrispondenza di Matelica e di Urbino nel taccuino dell’italiano mancano due pagine (ossia quattro fogli) che non sono riuscito a rintracciare altrove, per cui la percentuale di dipinti censita in comune nei quaderni è probabilmente ancora più alta53 .