27 minute read

Session 3 - Cruise Stream

CRUISE SESSION 3

VALERIA MANGIAROTTI

BIOGRAPHY

Marketing Manager – ADSP “Autorità di Sistema Portuale del Mare di Sardegna” (Port Network Authority of the Sardinian Sea). Valeria started her professional career in Port of Cagliari in 2002 and first was a lawyer in legal office in Milan. She involved in the cruise industry in 2004. She holds a degree in law from the Catholic University of Milan Italy. she became a lawyer in 1992 in the Court of Appeal of Milan. She attended a master in common law at London school of economic London. UK

She was a vice president of MedCruise, the Association of the Mediterranean Cruise ports between 2005 and 2008; she was in a board of MEDCRUISE like a director of environment from 2008- 2011. From 2013 she has a delegate for environment from MedCruise. From October 2017 she is the Director sustainability/ environmental issue of the Board of MedCruise, from October 2020 is Senior Vice president of MedCruise.

From November 2021 she is a director of technical environmental solutions of MedCruise.

MARTYN GRIFFITHS

Director for Public Affairs, CLIA in Europe

BIOGRAPHY

Martyn Griffiths is a Welsh man who has been living and working in Brussels since 1999. He is currently the Director Public Affairs at the Cruise Lines International Association a position he has held since 2016. He is responsible for issues management and developing proactive communications around the industry’s sustainability initiatives.

Previously he spent six years at the animal welfare NGO, Eurogroup for Animals, helping the organisation redefine its purpose from a legislative focus to a proactive campaigning focus. He has also worked for CEPI the European Paper Producers Association where he developed their sustainability approach including the Paper Value Tree and Meet Paper initiatives.

His first appointment in Brussels was as Communications Manager with the European Council of Vinyl Manufacturers where he developed the industry’s 10-year sustainability programme, Vinyl 2010, as well as the industry’s award-winning specifier engagement programme, PVC for Life and Living.

His background saw him study Management Science at Aston University in the UK followed by post-graduate studies in Media and Public Relations at the Welsh School of Journalism, University of Wales, in Cardiff. He is a specialist in issues and crisis management and has worked for many organisations in all sectors of society helping them manage major change programmes and major customer/audience issues management programmes.

INTRODUCTION

CLIA represents 95% of the world’s ocean-going cruise capacity, as well as 54,000 travel agents, 15,000 of the largest travel agencies in the world, and industry stakeholders, including ports, destinations, ship developers, suppliers, and business services. We are the only association that brings together ocean cruise lines and river cruise operators with travel agents and the wider cruise community. The cruise industry is one of Europe’s success stories supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs and contributing to economies.

The cruise industry is committed to pursuing net-zero carbon cruising by 2050 and supports the long-term objectives of the EU Green Deal. By driving innovation through shipbuilding in Europe, the industry can help to enable European green growth, as set out in the Green Deal and EU recovery plans.

BACKGROUND

On 8 November, we published our 2021 Global Cruise Industry Environmental Technologies and Practices Inventory (ETP) and associated Environmental Report produced by Oxford Economics (OE).

The annual report demonstrates the industry’s commitment to responsible tourism practices and our continued progress on the development and implementation of green maritime technologies. Our vision is net-zero carbon cruising by 2050 and CLIA and our ocean-going members are investing in new technologies and cleaner fuels now to realise this ambition. The report notes substantial progress across a range of areas:

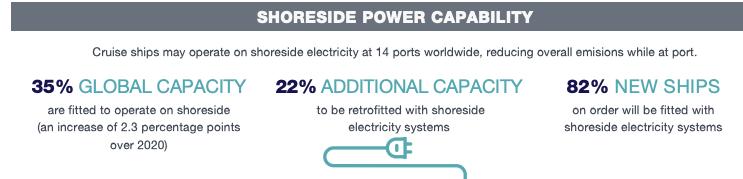

Shoreside electricity (SSE)

Cruise lines continue to make significant investments to enable ships to connect to shoreside electricity, allowing engines to be switched off in port.

Globally, 82% of new build capacity is either committed to be fitted with shore-side electricity capability or will be configured to add SSE in the future, and 35% of global capacity is fitted to operate on SSE in the 14 ports worldwide where that capability is provided in at least one berth.

In Europe, EU Fit for 55 proposals state that all ships must connect to SSE (or use compliant fuel) by 2030, regardless the type of berth. Currently, however, there are only a handful of berths providing SSE in European ports. Furthermore, based on publicly announced investments, it is currently projected that only 5.81% of cruise berths in the EU will be able to provide SSE

by 2025. While it is therefore clear that significant investment in portside infrastructure will be required, there are many collaborations underway between cruise lines, ports and local authorities to increase SSE.

New, alternative fuels

The report addresses the challenge posed by the need for new, alternative fuels to achieve ambitious carbon reduction goals and the steps the industry is taking to support progress. Specifically, in addition to LNG, over three-quarters of the global cruise fleet by passenger capacity is equipped to use alternative fuels. Alternative fuel sources being developed include biodiesel, methanol, ammonia, hydrogen, and electric batteries. The report notes that there remain engineering, supply, and regulatory hurdles before the large-scale adoption of such fuels can take place, but the cruise industry’s growing investment is facilitating the research and development of these fuels.

Underpinning the European maritime economy

The cruise industry underpins shipbuilding and the maritime economy in Europe. Notably, 80% of the value of ships built in Europe are cruise ships, representing a significant contribution to European economies. Europe is a global leader in building the complex, future-proof cruise ships in operation today. The skillsets, experience, and technical knowledge developed in member states as a result offer worldwide competitive advantage and put cruise squarely at the heart of Europe’s green growth ambitions.

Find out more about our global environmental sustainability

THREE PILLARS TO NET-ZERO CARBON CRUISING

Pillar 1 – Shoreside electricity

Cruise lines are committed to connecting to shoreside electricity when it is available and to working closely with ports to make this possible. Connecting a large cruise ship with a power consumption of up to 12 megawatts to the shore power grid is not as simple as it sounds. In addition to a technical infrastructure including a power plant, supply lines and conversion equipment, various tests and synchronisation measures are required to ensure uninterrupted ship operations. This procedure must be repeated for every ship in every port before the permanent connection can be made.

CLIA members are committed to working with ports and local authorities to support these projects. So far, however, more cruise ships are equipped with shore power connections than there are ports internationally that offer this option and CLIA members have committed to send ships equipped with SSE technology to ports where it is available and to use SSE while berthed. In line with the Fit For 55 Package CLIA is encouraging all ports to equip their cruise berths with this capability, to the benefit of their local population and to support the decarbonisation of the maritime sector.

Pillar 2 – Alternative Fuels

Alternative fuels are a critical element to the maritime industry decarbonization strategy. CLIA Europe is therefore calling for a more consistent approach to the measures proposed throughout the Fit for 55 package to support the production and use of alternative fuels.

Today there are 26 cruise ships currently sailing, on order or under construction powered by LNG for primary propulsion. This means that 52% of new build cruise ships capacity currently on order is committed to rely on LNG for primary propulsion3. CLIA welcomes the introduction

of a specific target for LNG supply in the Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T) ports. To ensure consistency with the rest of the package, supply of Renewable Synthetic LNG should also be clearly supported in the Renewable Energy Directive. Beyond LNG, cruise operators are also exploring other options to decarbonize the energy used onboard, hydrogen and hydrogen derived fuels should also be supported in the EU schemes. In this regard, the mandate for Member States to develop by 2024 a national policy framework including “a deployment plan for alternative fuels infrastructure in maritime ports other than for LNG and shore-side electricity supply for use by sea going vessels” (Art. 13.1.n) is welcomed. CLIA and its members are committed to supporting Member States in the development of these plans, ensuring that they also take the specific needs of cruise ships into consideration.

Pillar 3 – Circular Economy

CLIA and its cruise line members have enjoyed a close and positive cooperation with the destinations they visit for many years but now more than ever our sustainability profile is being challenged. Cruise lines are developing policies and systems to respond to the demands of a fully circular economy. Waste management, resource reduction and sustainable procurement are central to this. In the EU the Port Reception Facilities Directive manages the interface between shipping companies and the ports. It is therefore vital that we can be sure that our waste is being recycled and managed sustainably and that the destinations we visit recognise this.

CONCLUSION

Cruising is at the forefront of delivering a sustainable maritime sector, We are at the forefront of maritime innovation and offer many best practices that can be employed across the shipping industry.

We continue to invest and develop our ships to ensure they have the minimum impact n the destinations they visit and provide economic well being to the destinations we visit.

RYANN CHILD

Environmental Program Manager, Port of Seattle

BIOGRAPHY

Ryann Child (she/her) is responsible for designing and implementing clean air and climate action programs to reduce air and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from Port of Seattle’s maritime operations. Ryann is the project manager for the Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor, a new partnership of ports, cruise lines, and nongovernmental organizations exploring the feasibility of zero-GHG emission cruise ships to Alaska. Ryann also developed the Port’s first ever Maritime Climate and Air Action Plan. She has a background in environmental consulting and holds a B.A. in Environmental Science and Policy from Duke University. Outside of work, Ryann enjoys running, biking, and playing competitive Ultimate Frisbee.

Current duties and responsibilities: • Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor project manager • Develop and implement projects and programs to reduce air and greenhouse gas emissions from Port of Seattle’s maritime properties and operations • Conduct the Port’s annual Maritime GHG Emissions Inventory • Lead climate and clean air community engagement

Exploring a Green Corridor to Alaska: Early lessons on regional collaboration toward zero GHG emission cruise ships

In May 2022, the Port of Seattle, City and Borough of Juneau, Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, Carnival Corporation, Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings, Royal Caribbean Group, Cruise Lines International Association, the Global Maritime Forum, Blue Sky Maritime Coalition, and Washington Maritime Blue announced a commitment to explore the feasibility of the world’s first cruise-led green corridor in the Pacific Northwest of North America. The communities of Sitka, Skagway, and Haines in Alaska and the Greater Victoria Harbour Authority have also joined the partnership. This presentation will share Port of Seattle’s reflections on early lessons from the establishment of this international public-private partnership and preview the opportunities and challenges ahead as this collaborative explores the feasibility of zerogreenhouse gas emission cruise ships serving the Alaska cruise market.

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 About Green Corridors

In 2021, twenty-four countries, including the United States and Canada, signed the Clydebank Declaration. The declaration committed the countries to support the establishment of at least six green corridors by 2025 while aiming to scale up activity in future years.1

Green corridors are a new concept globally and leaders are needed to step forward and make this vision a reality. Globally, there is not yet a shared understanding of what it means for a maritime corridor to be “green” nor are there well-documented, or one-size-fits-all, solutions to achieve a green corridor.

According to the Global Maritime Forum, a green corridor is a shipping route where zero greenhouse gas (GHG) solutions are considered, demonstrated and supported. Green corridors—through collaboration across sectors—establish the technological, economic, and regulatory feasibility needed to accelerate implementation of low and ultimately zero GHG emission vessels.2 Additional definitions have developed as more green corridors emerge across the world, with some focusing on incremental emission reduction and others focused on technology development and fostering the deployment of scalable zero-emission fuels.3

It is up to ‘first movers’—those who wish to take early action to demonstrate feasibility—to collaborate, define, and implement the optimum pathway to get to zero.

This paper provides early insights into what it will take to explore and establish a green corridor focused on cruise ships in the Pacific Northwest of North America.

1 UN Climate Change Conference UK 2021. (2021). Clydbank Declaration for Green Shipping Corridors. Retrieved from https://ukcop26.org/cop-26-clydebank-declaration-for-green-shipping-corridors/ 2 Global Maritime Forum. The Next Wave: Green Corridors. November 2021. https://www.globalmaritimeforum.org/ content/2021/11/The-Next-Wave-Green-Corridors.pdf 3 Global Maritime Forum. (2022). Discussion Paper: Green Corridors: Definitions and Approaches. Retrieved from https://www.globalmaritimeforum.org/content/2022/08/Discussion-paper_Green-Corridors-Definitions-and-

Approaches.pdf

1.2 About Port of Seattle

The Port of Seattle (the Port) was founded in 1911 as a special-purpose municipal corporation serving the citizens of King County in Washington State, USA. The Port is governed by a publicly elected board of commissioners. Its mission is to create good jobs regionally and across Washington by advancing trade and commerce, promoting manufacturing and maritime growth, and stimulating economic development.

Since inception, the Port mission evolved to include not only economic interests but also a deep commitment to environmental and social goals. This commitment shows in the Port’s progressive Century Agenda goals4, its vision to be the greenest, most energy efficient port in North America, and its significant investment in environmental programs.

The Port is a leader in moving people and cargo across the country and around the world. Port’s operations include:

6 One of the largest cruise port on the West Coast with over 1.2 million revenue cruise passengers in 2019 and 1.2 million expected in 2022 6 The Northwest Seaport Alliance (NWSA), a marine cargo operating partnership between Port of Seattle and Port of Tacoma in Washington, the 4th largest container gateway in the U.S. 6 Bulk cargo terminal that exports over 4 million tonnes of grain and soy, connecting farms in the American Midwest to consumers in Asia 6 Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, the 10th busiest airport in North America 6 Home to the North Pacific Fishing fleet, vessels based at Port of Seattle supply about 13 percent of the total U.S. commercial fishing harvest by tonnage 6 Real estate portfolio of over 80 buildings across 10 waterfront campuses 6 Recreational boating marinas, some with nearly 600 year-round, live-aboard tenants

Figure 1. Port of Seattle Maritime and NWSA Managed Properties

4 Port of Seattle. Century Agenda: Strategic Objectives. https://www.portseattle.org/page/centuryagenda-strategic-objectives

1.3 The Seattle to Alaska Cruise Market

Port of Seattle is one of the largest and fastest growing cruise market on the West Coast with two cruise terminals and three cruise berths:

6 A single berth facility at the Bell Street Pier Cruise Terminal at Pier 66 on the downtown waterfront; and, 6 A double berth facility at the Smith Cove Cruise Terminal located at Pier 91 north of the city’s waterfront.

Cruise is a major economic driver in Seattle. The cruise industry delivers $900 million in annual business revenue to the greater Seattle region during typical operations. In 2019, cruise hit a record year with 1.2 million revenue passengers passing through terminals in Seattle. After the cancellation of the cruise season in 2020, cruise ships returned for a partial season in 2021 with 82 cruise calls and 229,000 revenue passengers at Seattle terminals. Cruise has rebounded in 2022 with an anticipated 1.2 million revenue passengers in Seattle and a record number of cruise calls.

In Alaska, cruise brings over one million cruise passengers to visit each year. In 2019, cruise ship passengers hit record levels at 1.33 million people sailing. In 2022, Juneau—the primary port of call in Alaska—is scheduled to see over 680 vessel calls.5 Cruise travel to Alaska contributes $3 billion to Alaska’s economy each year.6

Table 1. Scheduled Cruise Ship Calls for 2022 in Participating Ports Along the Green Corridor

Port Community

Juneau, Alaska, USA Skagway, Alaska, USA Victoria, British Columbia, Canada Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada Seattle, Washington, USA Sitka, Alaska, USA Haines, Alaska, USA

2022 Cruise Ship Calls Scheduled

682 461 320 290 289 285 76

Source: Cruise Lines International Association. (2022). 2022 Port Schedule. Retrieved from CLIA Alaska: https://akcruise.org/port-schedule/

1.4 Toward the Greenest Port in North America

The Port hosts one of the largest cruise markets on the West Coast and has ambitions to be the greenest. For more than 20 years, the Port of Seattle has prioritized protecting the environment while growing cruise. Key environmental accomplishments and ongoing initiatives include: 6 Prioritizing water quality protection in Puget Sound: Since 2004 the Port has partnered with Washington State Dept. of Ecology and the cruise industry in a

5 Cruise Line Agencies of Alaska. JNU-Juneau-2022. https://secureservercdn.net/198.71.233.116/2xl.54d.myftpupload. com/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/JNU-Juneau-2022.pdf 6 State of Alaska Departments of Revenue, C. C. (2021). Impacts to Alaska from 2020/2021 Cruise Ship Season

Cancellation. Retrieved from https://gov.alaska.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/04082021-Cruise-Impacts-to-

Alaska.pdf

voluntary agreement, called the Memorandum of Understanding Cruise Operations in Washington State, which helps prevent wastewater discharges from large cruise ships into state waters. Starting in 2020, the Port prohibited cruise ships at berth from discharging exhaust gas cleaning system wash water. 6 Partnering on clean air: Since 2008, the Port has collaborated on the Northwest Ports Clean Air Strategy. The 2020 Strategy sets a bold vision to eliminate air pollution and be carbon free by 2050 and calls for ongoing partnerships and engagement with the cruise industry, governments, community groups, and other ports. 6 Reducing at-berth emissions with shore power: The Port provides clean shore power at two cruise berths at Terminal 91 and is on track to add shore power to its third berth at Pier 66 by 2024, making all cruise berths shore power capable. 6 Accelerating GHG reduction targets: In 2021, Port of Seattle accelerated its GHG reduction targets: - By 2030, achieve a 50 percent reduction in GHG emissions (Scopes 1, 2, 3) - By 2040, achieve net zero or better for Port-owned GHG emissions (Scope 1 & 2) from a 2005 baseline - By 2050, achieve carbon neutral or better for GHG emissions from industries operating at ort facilities (Scope 3) from a 2007 baseline 6 Charting the course to zero emissions: Port Commission adopted the Port’s first ever Maritime Climate and Air Action Plan in 2021. 6 Planning for clean energy: The Port is partnering with its electric utility and waterfront industry to complete a Seattle Waterfront Clean Energy Strategy, which will holistically identify the policies, technologies and investments needed to deploy zero-emission infrastructure and to enable the transition to zero-emission maritime equipment and operations.

2.1 Why create a Green Corridor to Alaska?

There were several reasons behind the development of the Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor.

From Port of Seattle’s perspective, it started with the need to address the complex challenge of reducing air and GHG emissions from cruise ships. Cruise ships are the largest source of maritime-related emissions for the Port (not including marine cargo terminals in Seattle, which are operated by the Northwest Seaport Alliance). The Port has set ambitious GHG targets and put in place plans to chart a course to zero-emissions, but maritime industries continue to face significant barriers to the large-scale development and deployment of zero-emission maritime fuels and technologies. While there is not yet a clear pathway or silver bullet solution to address these emissions, a public-private partnership on a green corridor increases the Port’s span of influence and fosters the collaboration needed to accelerate the decarbonization of cruise and the maritime sector as a whole.

Additionally, the Port recognized the significant opportunity for the region to establish a green corridor: 1. The Port has a history of working with other ports and cruise lines in the Pacific Northwest region to partner on environmental action. These established relationships create a strong foundation for a green corridor partnership to build upon; 2. Washington State has laws and programs already in place that support reducing carbon emissions from transportation;

3. The Pacific Northwest is a highly diversified hub for maritime research and development, innovation, engineering, and for private sector companies pioneering clean technologies and maritime fuel; and, 4. A distinct maritime corridor exists between Puget Sound and Alaska with regularly scheduled vessel calls by cruise, commercial fishing, cargo, ferries, and tug industries.

Furthermore, communities adjacent to port terminals and other industrial properties in Seattle bear a disproportionate burden of health impacts and environmental injustices compared to other areas of the city. A green corridor and the transition away from fossil fuels can accelerate environmental justice for near-port communities that experience more exposure to air pollution and the impacts of a changing climate.

All of these factors signaled both the need for action and the existence of key “building blocks”7 that could support an emerging, cruise-focused green corridor to Alaska.

2.2 First Mover Commitment

The initial set of partners who signed on to the Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor are called “First Movers”, as these organizations are committed to taking early action and demonstrate the feasibility of a green corridor. Partners signed a First Mover Agreement committing to taking the following steps:

6 Work together to explore the feasibility of a green corridor in the Pacific Northwest of North America, including, but not limited to, further defining the scope and application of the green corridor concept; 6 Enhance and support the emission-reduction efforts already underway and using the green corridor as a testbed for low and zero GHG technologies and ships, as feasible; and 6 Work collaboratively to define the governance structures, terms, and frameworks needed to guide this regional effort. At the time of writing, project partners include the following cruise ports and port communities in Seattle, British Columbia, and Alaska, cruise lines, and nongovernmental organizations:

6 Port of Seattle, Washington 6 Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, British Columbia 6 Greater Victoria Harbour Authority 6 Haines Borough, Alaska 6 City and Borough of Juneau, Alaska 6 City and Borough of Sitka, Alaska 6 Municipality of Skagway, Alaska 6 Carnival Corporation and its cruise brands including Princess, Holland America Line, Carnival, Seabourn, and Cunard 6 Norwegian Cruise Line Holdings and its cruise brands including Norwegian Cruise Line, Oceania Cruises, and Regent Seven Seas Cruises 6 Royal Caribbean Group and its cruise brands including Royal Caribbean International, Celebrity Cruises, and Silversea Cruises

7 Global Maritime Forum. The Next Wave: Green Corridors. November 2021. https://www.globalmaritimeforum.org/ content/2021/11/The-Next-Wave-Green-Corridors.pdf

6 Cruise Lines International Association 6 Global Maritime Forum 6 Blue Sky Maritime Coalition 6 Washington Maritime Blue

The initiative could potentially expand to other maritime sectors or other regional ports in the future. The initial focus, however, is on the cruise corridor as there are unique aspects of cruise travel to account for when assessing the feasibility of a zero-emission ship and corridor.

2.3 Progress to Date

Since launch of the project in May 2022, First Mover Partners have met monthly. Initial conversations covered project organization and governance, and focused on the following foundational questions: 1) How do we work together? 2) How do we make decisions? 3) How do we appropriately engage stakeholders who want to be involved and/or have some expertise to share in this endeavor?

At the meeting in August, First Movers focused on how to define a green corridor specific to the Alaska cruise market. Partners shared their initial thoughts on a definition. Since this is the first cruise-focused green corridor in the world, First Movers have an opportunity to establish a definition that can contribute to shaping green corridors globally as well as one that captures the uniqueness of cruise and the Pacific Northwest. Input shared regarding the definition will also inform the scope of the project and feasibility study. The initial discussion on a green corridor definition raised several themes: 6 There is interest in aligning with internationally recognized definitions of green corridors that focus on zero-GHG emission vessels, while also acknowledging local goals and the need to reduce emissions along the way to the zero-emission transition. 6 The definition should consider the smaller ports involved and how these ports may contribute differently to the corridor. 6 More discussion is needed to define the scope of the corridor and whether it will include cruise operations beyond ships, such as buses and shore excursions. 6 Partnership and stakeholder involvement is a critical element of a green corridor. First Movers recognize that an effort of this scale must happen though collaboration and involve the full value chain. Similarly, how to engage community stakeholders and environmental justice advocates must also be defined

3 EARLY LESSONS

3.1 Cruising is not shipping.

The Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor is the first green corridor in the world to focus on cruise ships. As more green shipping corridors emerge across the world, there is the desire to find opportunities to align and share lessons, but also a need to acknowledge key differences. The following elements are some of what make a cruise-focused green corridor unique: 6 A round-trip journey with multiple stops: Rather than a corridor that moves goods from point to point, cruise ships traveling to and from Alaska make multiple stops along the way, and most ships return where they started in either Seattle, Washington or Vancouver, British Columbia. These characteristics could open up opportunities not feasible for transoceanic shipping, such as the use of less energy dense fuels. It could also mean that fuel could come from a single source at the homeports in Seattle and Vancouver, with some exceptions, where cargo routes must think about

zero-emission infrastructure at both ends. How the corridor could include the Alaskan ports will be different than how a freight corridor will include turnaround port partners at each end. 6 Large and small ports: While ships leave from large ports in Seattle and Vancouver, they stop in small, rural Alaskan communities. There is a big difference in both the resources available between the homeports and smaller ports along the itinerary and the ways that each of these partners can contribute to the corridor. For example, some Alaskan port communities receive electricity powered by diesel. 6 Hotels at Sea: A fully zero-emission cruise vessel will need to think beyond zeroemission ship propulsion and also consider the higher hoteling loads of cruise ships required to power hotel, dining, and entertainment on board. This may mean cruise ships require different power demand and storage solutions, such as fuel cells to support hoteling loads. Cruise ships also have different space and safety challenges, compared to other vessel types. 6 Seasonal industry: The Alaska cruise industry is seasonal, running roughly 6 months out of the year from April through October. A zero-emission solution or fuel will likely need to leverage other use categories in addition to cruise to reach a feasible scale. Decarbonization solutions along the corridor will still need to be applicable to other maritime sectors as well as other areas that cruise ships operate outside of the Alaska season. While cruise vessel movements and needs may be unique, these ships also only account for 323 ships sailing at sea. Cargo shipping will ultimately drive the demand for zero-emission maritime fuels and technologies globally.

3.2 Establish common ground.

The Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor may have the most diverse range of partners involved of any green corridor in the world to date. More partners can help bring in the many key players needed to be engaged in the zero-emission transition but can also add complexity and conflict around level of ambition. To form the partnership, global cruise lines and ports had to come together to establish the First Mover Commitment. First Movers specifically committed to “explore the feasibility of a maritime green corridor aimed at accelerating the deployment of zero GHG emission ships and operations between Alaska, British Columbia, and Washington.” While decarbonization goals among partners may differ, the First Mover Commitment and focus on the feasibility study creates common ground for discussions among partners to build from. More discussion will be needed to help define what zero-GHG means (e.g., net zero, carbon neutral, etc.) and whether the scope will focus only on cruise vessels or a larger definition of “operations” which could include shore excursions, buses, and passenger ground transportation, and/or vessel provisioning.

3.3 Process is progress.

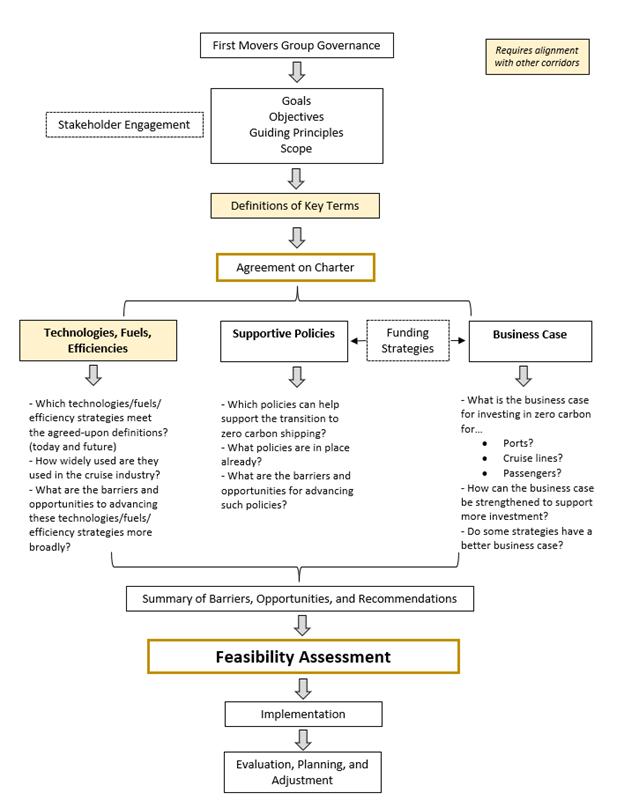

Developing a green corridor is a process that happens over time; a progressive “greening” of a corridor toward goals. Getting to a feasibility assessment and then implementation requires a series of intermediary steps and questions for First Movers to answer. The process can seem overwhelming and there’s a constant impulse to try to tackle every question and decision needed at once: how do we make decisions? How do we define a green corridor? What are the goals and objectives? What is the scope? Who pays for the feasibility study? What zeroemission fuels are on the table? And on and on. Success in getting work underway has meant taking each question one at a time and mapping out a process of decisions needed to get to the feasibility assessment.

Figure 2. Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor Development Process

Additionally, establishing a multi-lateral, multi-national partnership takes time. While there’s a need to make progress and continue a sense of urgency toward action, establishing protocols for decision-making and project governance and building relationships, rapport, and trust among partners will pay dividends as work progresses.

3.4 Balance early action with long-term decarbonization.

Another lesson and early area of agreement is that while international definitions of green shipping corridors focus on long-term decarbonization of the maritime sector, there is an opportunity to identify early action projects and low-hanging fruit as First Movers study the feasibility of zero-GHG emission cruise ships. For example, cruise lines are already making progress on energy efficiency and waste reduction and exploring future fuels and technologies, and there are new federal funding opportunities in the U.S. to develop hydrogen. There may be opportunities for First Movers to collaborate on emission reduction projects and zero-emission maritime fuel pilots in the near-term.

3.5 Decarbonization is a team sport.

While the Port of Seattle has a goal to be become the greenest port in North America and be a leader in decarbonizing the maritime industry in Seattle, we will not be successful if we act alone. Partnerships, like the Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor, can expand our influence and impact to drive change at the local, regional, and global scale. As one of the First Movers well-articulated at the kickoff meeting, “decarbonization is a team sport.” It will take strong partnerships between ports, government, industry, utilities, community, and others in these efforts to support policy change, create funding opportunities, develop new technology solutions, and ensure a just transition for the workforce and port communities.

4 NEXT STEPS

The Alaska, British Columbia, Washington Green Corridor launched in May 2022 and the partnership remains in the early steps of determining definitions, scope, and project governance. First Movers are working toward a formal charter to be released in fall 2022 that will capture agreement on definitions and organization. Establishing a charter will enable work to begin on the joint feasibility study. First Movers are working now to scope what that effort will look like, the key questions the study will answer, and how to fund it. The feasibility study is expected to launch in early 2023. First Movers have also already begun discussions about early action projects and collaboration opportunities, such as new funding opportunities for hydrogen and port electrification in the United States.

For more information: greencorridor@portseattle.org

Practical Insights into Shore Power projects

PETER CASTBERG KNUDSEN

Partner, PowerCon

BIOGRAPHY

As a founding partner of PowerCon, Peter has had a leading role in PowerCon’s transition to being Europe’s leading supplier of Shore Power systems for cruise ports. Peter has 15+ years experience in working with power electronics and the integration of MW converters in large power applications. Peter has been directly involved in the construction of the largest Shore Power projects in Norway, Denmark, Germany and the UK, and has thus gained valuable insights into these complex projects.