7 minute read

Ukraine What Next?

The recent breakthrough on grain exports from Ukraine represents a ray of hope in an otherwise problematic picture that entails a significant impact on maritime trade. Andrew Penfold analyses the forward picture

Russian hopes for a quick and relatively painless invasion of the Ukraine have stalled. As the war position stagnates, the economic impact of the ‘Special Military Operation’ is beginning to emerge. The effects range from widely increased uncertainty at the global economic level to concerns over grain trades becoming a bargaining chip in the conflict and the suppression of emerging opportunities in the Black Sea. These considerations seem certain to control the tactical and strategic nature of port investments in the next few years.

MACRO-ECONOMIC IMPACTS

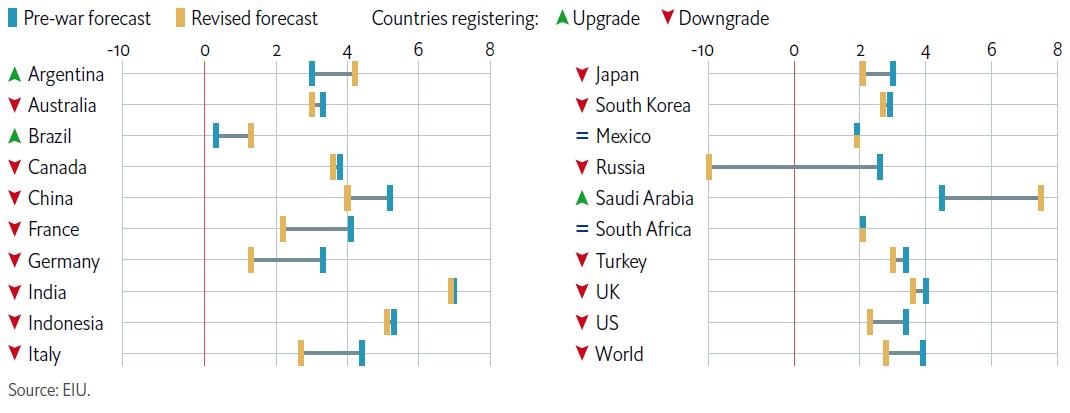

The link between economic expansion and trade – especially in the container sector – is well known. Demand growth has been directly linked to the size of the world and regional economies. The outlook was already uncertain postCOVID-19, but a whole new set of risks are now determining the shape of the world economy. The Economist Intelligence Unit has sought to quantify the resulting downside on a national level and their latest thoughts are summarised in Figure 1.

Only the commodity exporters (oil and grain) seem likely to see a positive benefit from increased prices for their exports. In the OECD, most countries will struggle to maintain a positive outcome for 2022. The world economy is forecast to grow at a rate of around 2.5 per cent in contrast with a prewar projection of 4 per cent. This is a major change.

It should be noted that these projections may well prove to be over-optimistic. Emerging problems in the Chinese economy could well be much more far-reaching than here suggested, with some assessing that following the Shanghai lockdown and worsening property market scandals Chinese expansion could be struggling this year.

So far, these changes have not hit the container trade sector, with underlying demand distorted by Covid recovery demand bounce back and supply chain congestion. There are signs that growth is now slowing and the long established link between GDP and container demand on the major eastwest trades is re-emerging – perhaps with a ratio of around 1 : 1.2. If this is the outcome – and OECD recession seems daily more likely – then a period of very slow container trade can be anticipated.

The blame for at least half of any slowdown can be directly laid at the door of the Ukraine crisis aggravating an already difficult inflationary climate. Monetary tightening in the US (and Europe) in an attempt to control inflation will worsen the outlook.

Perhaps the biggest long-term result will be a loss of faith in the seemingly unstoppable acceleration in container trades? Even if growth is maintained through this period, it seems likely that major restructuring will follow from a revised view of China as the major supplier of global manufactured goods.

GRAIN SPECIFICS

A global contraction will always be most felt in the poorest countries. Such a slowdown is already playing havoc with some economies. The effective bankruptcy of Sri Lanka, where questionable economic and agriculture policies have been exacerbated by a surge in import prices, is a harbinger of

8 Getting Ukraine’s

grain moving again is not a simple matter – Russia has inflicted significant damage on port export capacity as witnessed at the port of Mykolaiv where a major export terminal has been the focus of air strikes

Source: Economist Intelligence Unit

potential problems. Resulting political instability is problematic to programme in to fixed infrastructure investments.

At the global level, the most serious issue is grain supply. At the time of writing (end-July 2022) a deal had just been struck with Russia to open the door on Ukrainian grain exports. It remains to be seen, however, if the agreement holds – it is clear that keeping this ‘door’ open represents something of a bargaining chip for Russia as well as a visible way for it to flex its muscle.

The blockade of Ukraine’s grain exports can only result in escalating global hunger, with the Ukraine accounting for at least 20 per cent of globally traded grain. Nations across Asia and Africa are particularly reliant on these supplies, and the war has also limited its crop shipments by road, rail and river to neighbouring European Union nations.

There are moves brokered by Turkey and the UN to openup an alternative export route for grain exports. Exactly how Odesa (and other grain outlets) can be secured from attack and the feasibility of third-party vessels guarding such shipments is far from clear. While bulk carrier owners may well step forward, the charter rates will be extremely high and insurance issues have not been addressed. It seems likely that progress will not be seamless and that relying on the goodwill of the Russians will prove an uncertain business.

A review of the scope for alternative supplies further underlines the problem. Argentina and Australia have always recorded sharp year-on-year changes in production (and hence export availability). Argentina has had a good crop year but can only play a limited role, but Australia is forecasting a decline in output this year. Both the US and Canada have the scope to increase production but not in the short term. There is simply no available grain to substitute for lost Ukrainian exports.

It is estimated that 22 million tonnes of last year’s Ukrainian grain crop is still sitting in storage. The implications of this are apparent to any observer – delay spells lost lives whether or not a workable maritime export solution is implemented.

BLACK SEA OPTIONS

The search for export gateway alternatives has accelerated. The first week of July 2022 saw around seven vessels loaded for export with grain at Ukrainian ports, but the actual security of these shipments remains uncertain, with the Ukrainian navy unable to offer solid protection.

Other alternatives have included the use of Romanian and Bulgarian ports. Grain has reached the Danube for export via the Bystroe and Sulina Canals which provide a link between the Danube and the Black Sea. But draught is very limited, and storage is not optimised for this option. This is an alternative and, linked with Constanta, provides a limited – and very expensive – option. Constanta has been an important hub for Ukrainian cargoes in the opening months of the war but is now reported to be working at full capacity both for containers and grains.

Also in Romania, there are moves to reopen the old Sovietera rail link between the river port of Galati and the Ukraine via Moldova. Although a positive move, provision of associated rail and storage investment cannot be delivered in the short term – and certainly not on a commercial basis.

Bulgaria’s Black Sea port of Varna is also in the process of seeking to take some of these cargoes – especially as Constanta fills-up. There have been many enquiries for this route since June and the Bulgarian government has sought to simplify cross-border rules for trucks carrying Ukrainian import and export cargoes. Bulgaria’s Prime Minister has said that the country could provide assistance both by shipping Ukrainian grain and by increasing its exportable surplus. But all of this will require heavy investment in Varna and – potentially – Bourgas.

We are also seeing increased examination of the Baltic option for Ukraine’s grain with a shipment for Spain routed over Polish ports in June.

The price of wheat has eased from recent peaks, but this is not an indication that the crisis has passed. Getting Ukraine’s grain to tidewater will be the biggest problem in the next few months. The port sector has reacted rapidly, but these are all short-term options at the margins of the problem.

It simply makes no sense to invest in these alternatives with the situation in the Ukraine so fluid. The best and cheapest option remains the reopening of the Ukraine’s ports to global trade. Will this be soon enough for the hungry mouths in the South and will the agreement recently reached with Russia to achieve this hold?

8 Figure 1: The Ukraine war will reduce global output by US$1trn in 2022 (real GDP growth)Only the commodity exporters (oil and grain) seem likely to see a positive benefit from increased The blockade of Ukraine’s grain exports can only result in escalating global hunger ‘‘ prices for their exports. In the OECD, most countries will struggle to maintain a positive outcome for 2022. The world economy is forecast to grow at a rate of around 2.5 per cent in contrast with a prewar projection of 4 per cent. This is a major change.