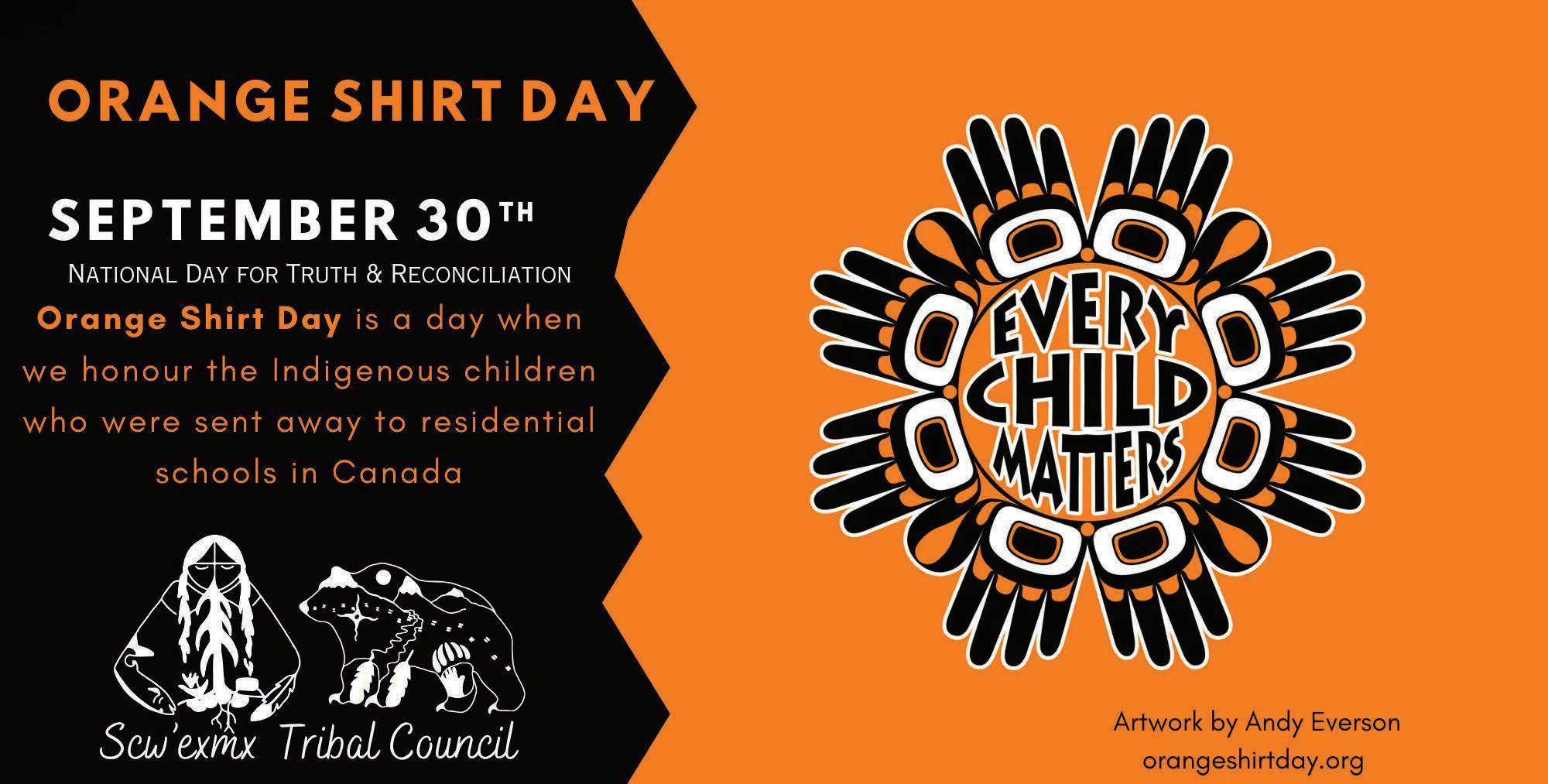

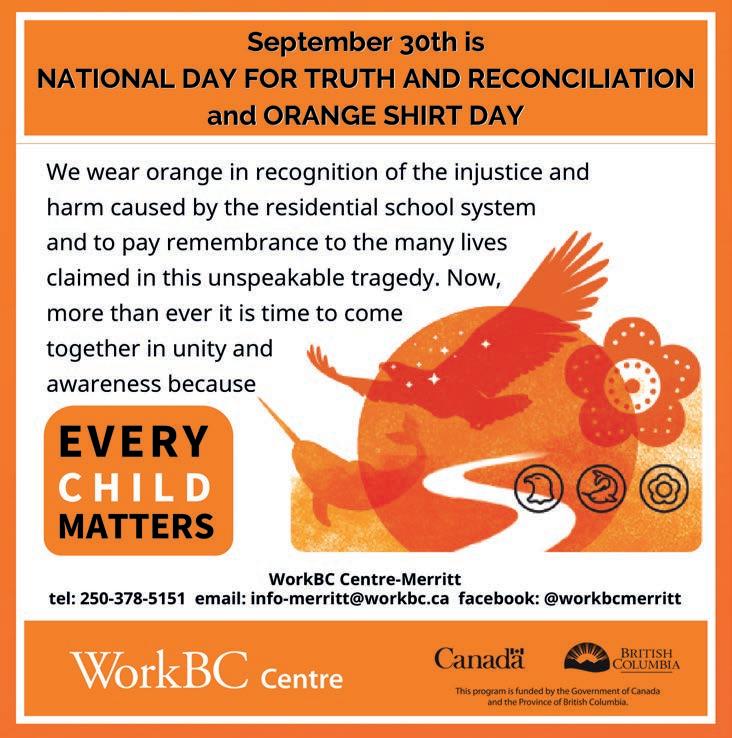

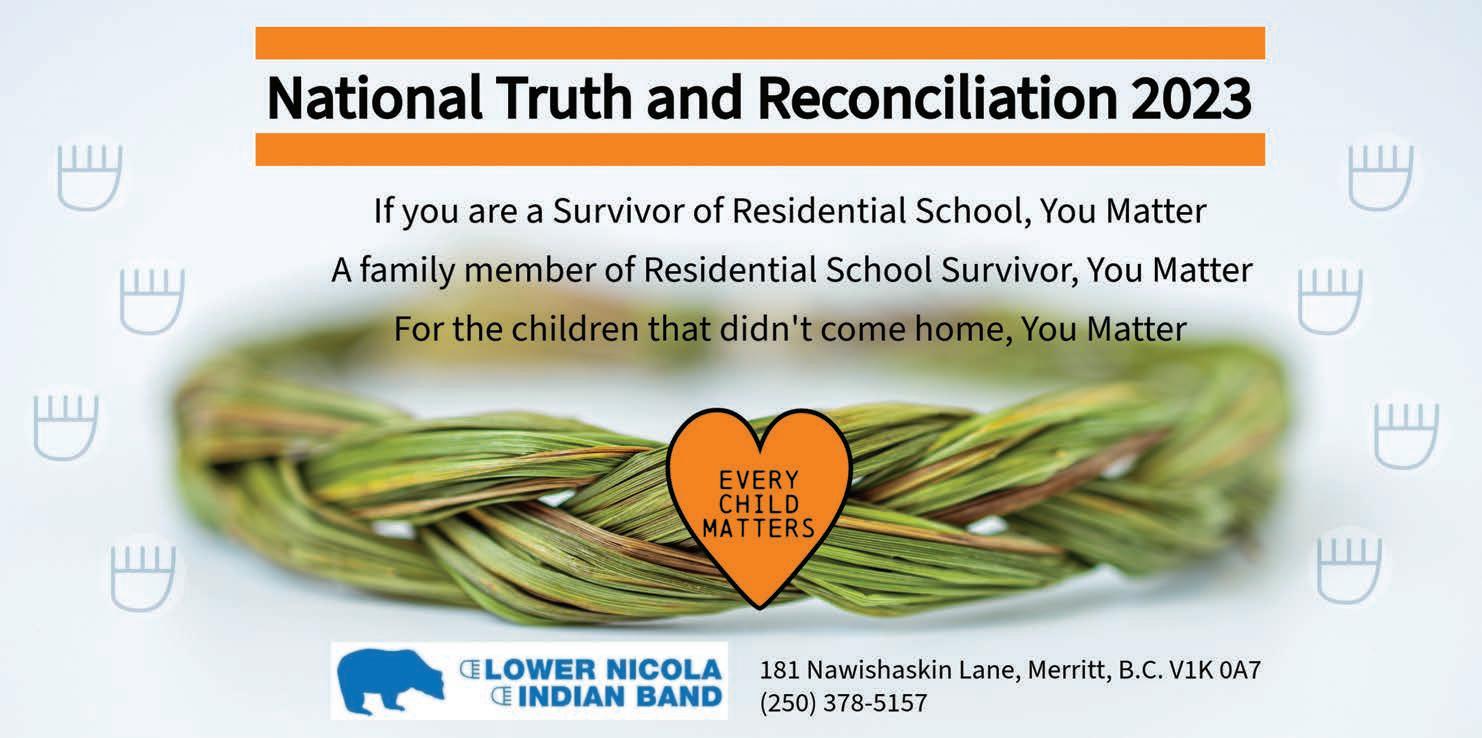

ORANGE SHIRT DAY

begins with Mother Earth. In all its beauty of the medicines of the insects, four legged, two legged, wing one, fin one, the rivers, the trees, the day and the night, the good and the bad, the warriors female and male that has a connection to our spirit.

We need to balance ourselves physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually to be grounded and balance. Less we forget our identity, our culture, our traditional teachings, ceremonies, language and songs. The Elders have this knowledge which was passed down to their generations and for this we say all our relations.

LNIB Elder - Richard Jackson Jr.

(Ottawa, ON) – In 2014 Assembly of First Nations (AFN) National Chief Ghislain Picard encouraged people across the country to mark Orange Shirt Day on September 30, a

day to recognize the experience of former students of Indian Residential Schools and affirm a collective commitment to ensure that every child matters. “On September 30th, he encourages everyone in Canada to wear an orange shirt to commemorate and remember the experience of the thousands of children who were taken from their families and placed in Indian residential schools and to show a commitment to work towards reconciliation,” said National Chief Picard. “September 30th is a day to engage in discussions with one another – First Nations and non-Indigenous Canadians and commit to a future where every child matters. Please join us in calling on the Government of Canada to officially designate September 30

as Orange Shirt Day, a day for all of us come together in the spirit of reconciliation, respect and partnership.” Orange Shirt Day is an outcome of the St. Joseph Mission Residential School Commemoration Project and Reunion events that took place in Williams Lake, BC in May 2013. It stems from a story told by former residential school student, Phyllis Webstad, who had her new orange shirt, bought by her grandmother, taken from her as a six-year old girl. She spoke powerfully of how it seemed to her that nobody cared and, in this personal way, it speaks to the many harms experienced by children in the residential schools.

“WE HONOR OUR ANCESTORS by practicing our cultural, traditional and spiritual teachings.”

Conayt Friendship Society

Arnie Narcisse spent over a decade in the residential school system - and wants to make sure that its history is not forgotten.

Laisa Conde REPORTER@ MERRITTHERALD.COM

Laisa Conde REPORTER@ MERRITTHERALD.COM

“We’re still here, we’re still survivors.”

That’s how Arnie Narcisse describes himself and all the other Indigenous people who were forced to go to residential schools in Canada during their childhood.

“When they call us a survivor, we really are. It’s not just a fancy term. It’s how many coins because if you live till tomorrow, you’re lucky, you are a survivor,” he said.

Narcisse is from St’át’imc First

Nation and currently resides on Lower Nicola Indian Band land, just outside of Merritt.

Some of Narcisse’s earliest memories are not of residential school, but of his time with his grandparents at the Pemberton potato fields.

“I can’t think of ever wanting anything, in all the time I was with him. I never knew hunger, I never knew loneliness, or anything like that,” Narcisse said.

Up until that moment in his life, he was known as Tonemsha.

“That was my name when I was this boy, until I was six years old. I didn’t know I

See I CAME TO Page 30

every child mat

Arnie Narcisse at his home in Lower Nicola. Photo/ Laisa Conde

Arnie Narcisse at his home in Lower Nicola. Photo/ Laisa Conde

From Page 29

had another name, Arnold,” he said. That ended when he was taken away and sent to St. Joseph’s Mission Indian School in Williams Lake in September 1959.

“I came to learn about hell. It was called St. Joseph’s Mission,” he said. “That’s what that place was, it was hell on earth. It was a dog-eat-dog world, nobody cared for anybody.”

St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School, located just kilometres from the Williams Lake First Nation community core of T’exelc, opened in 1867 and operated as an indian residential school between 1886 and 1981.

It was funded and run by the Canadian government and the Roman Catholic Church, with a main goal of assimilating children into white society and diminish Indigenous culture.

Like many residential schools, there are stories of abuse, negligence, disease

and accidents. One memory that sticks with Narcisse is the food that they served at the school.

“When I got there, the first meal I got was a bowl of mush, slimy mush. And I could not eat that and I took a lot of punishment because of that,” he said.

He also recalls one time that him and the other children were fed what he said was supposed to be pork meat.

“It was that much fat, a little bit of meat and the hair was still on the outside of it,” Narcisse said.

Narcisse said that another memory that sticks with him about St. Joseph’s is when his cousin died at the school under mysterious circumstances.

“All we heard was that he got sick, and he puffed up. I think he died due to negligence. They didn’t take him to the hospital

See THE UNKNOWN Page 31

contribute

creating a better future.’

From Page 30

in time and take good care of us enough to take him to the hospital,” he said. “Our lives were basically worthless to them.”

At the age of nine, Narcisse left St. Joseph’s Mission Residential School and was sent to the Kamloops Indian Residential School. He spent his days there until he was 17 years old.

The Kamloops Indian Residential School once was

the largest residential school in Canada, with 500 children enrolled.

In May 2021, Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc speculated that 215

graves could exist at the Kamloops Indian Residential

See BOOK Page 32

Dede designed this shir t in recognition of Orange Shir t Day.

Nicola Valley & Distr ict Metis Societ y

As a forgotten people we honour every child, we pray each child is found and returned to their families.

If you would like more information on our society please call 250-378-5015 or 250-378-0076 email: truck126@hotmail.com • Facebook: Nicola Valley Metis

NICOLA VALLEY INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY remembers and honours the residential school survivors, their families, and their communities.

From Page 31

School site. Once the bodies were found, Narcisse said that the news caused him mixed feelings.

“To some degree I was (surprised), but not really. The immediate thought that came to me was that I played down there,” he said. “We played on it. How many times did I run over a dead body when we were playing down there? None of us knew that.”

Years later, when his grandson asked him about residential schools, Narcisse felt the need to put his memories of that time on paper. No details are glossed over in his book ‘Hard to be a Good Indian’, in which he shares his surviving experience at both residential schools.

“I hadn’t intended to become a story, just a few factual notes that I was going to write down,” he said. “When I started, literally one line turned into one paragraph, one paragraph turned into a page. Some days, I’d write three or four pages.”

As the words in his book remind people of the dark days Indigenous people suffered, Narcisse keeps talking about it so people won’t forget about the horrific experiences that occurred in residential schools.

“That’s very much why I do this. To make sure that this doesn’t fade to black that this experience lives on. It’ll live on in my children, my grandchildren, my great grandchildren, and they will continue to tell this story.”

As a vital par t of Reconciliation, the Cit y of Merritt recognizes Truth & Reconciliation Day and Orange Shirt Day to honour the tragic histor y of loss that the indigenous peoples of C anada suffered from the residential school system, resulting in enduring impac t s.

EVERY CHILD MATTERS.

With National Day of Truth and Reconciliation coming on Sept. 30, the City of Merritt is showing their support all week by flying orange flags outside of civic buildings.

“We pledge our continued support to our surrounding Indigenous communities, and we will loudly advocate for diversity, inclusiveness, respect, and equality for all,” said Mayor Mike Goetz in a statement.

All Merritt civic buildings will be closed on Sept. 30 except for scheduled programming happening at the Merritt Civic Centre and Nicola Valley Memorial Arena.

City hall offices will be closed on Monday, Oct. 2 in recognition of the statutory holiday.

Jake

CourtepatteNEWSROOM@MERRITTHERALD.COM

As Canadians gather to commemorate those who suffered through the indian residential schools of the 18001900s, residents of the Nicola Valley will be taking part in their own ceremonies of remembrance.

Nicola Valley Institute of Technology

On Thursday, Sept. 28, NVIT will be hosting a fire ceremony and lunch from 10:30a.m.-1p.m.

Students, faculty and elders are encouraged to wear their orange shirts, and join in on drum sessions, prayers and storytelling.

Classes will also not be in session on

Friday, Sept. 29 to honour the statutory holiday.

School District 58

Merritt Central Elementary, Diamond Vale Elementary and Merritt Secondary School students will be meeting at Central Park beside the police station at 11a.m. on Sept. 29 for drumming and an opening ceremony, before walking together to Central Elementary.

Lower Nicola Indian Band

Those looking to participate can meet at 10a.m. at the band hall on Sept. 29, before walking to the Shulus Arbor. A light lunch

See Page 35

From Page 34

will be provided at 11:30a.m. For more information, contact LNIB Culture Coordinator Carole Basil at 250-315-9158.

For those looking to honour the day nationwide, Parliament Hill in Ottawa

will be broadcasting its national ceremony at 1p.m. Pacific time on Sept. 30. A moment of silence is also being asked to be observed at 2:15p.m., reflecting on the discovery of the remains of 215 children in a mass graveyard on the site of the former Kamloops residential school in May 2021.

The giggles, the smilies the little squeals of joy that children have are lives little gifts we receive. May we learn from the past and may every child experience such joy.

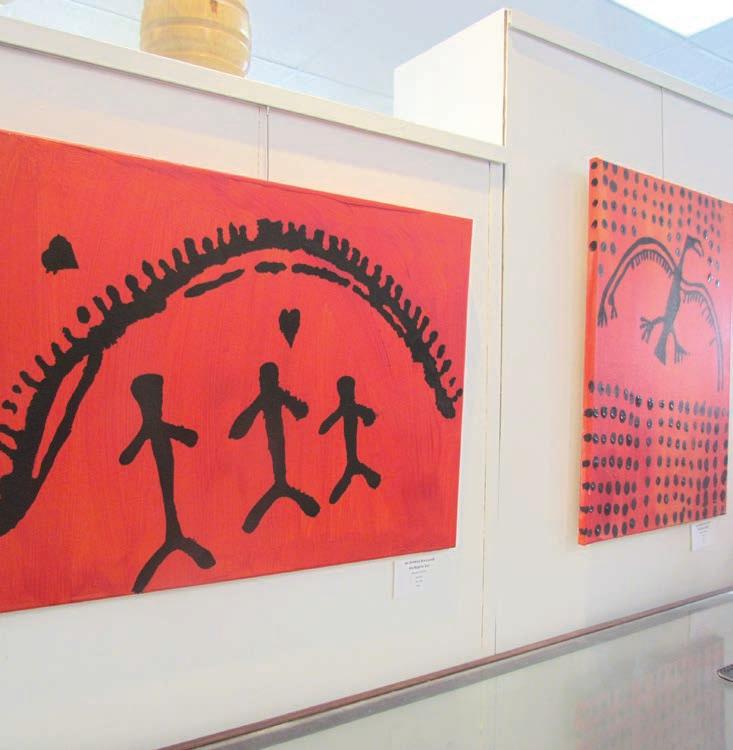

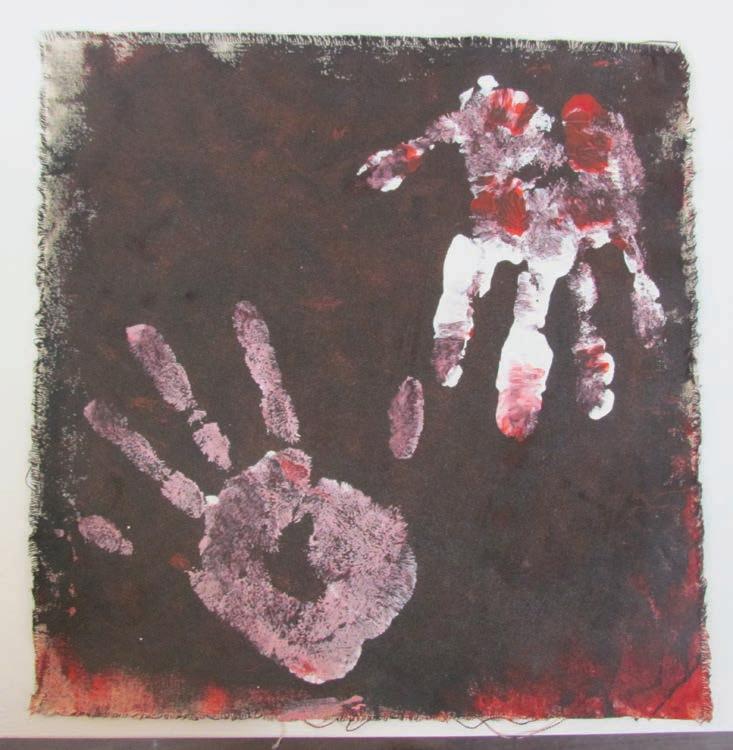

Paintings that honour the land, residential school survivors and those who have passed, as well as Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls are on display at the Nicola Valley Arts Centre gallery.

Local Nlaka’pamux artist Wyatt Collins, who navigates the world of autism, found his way to express himself through his art. Rona SterlingCollins, Wyatt’s mom, said that painting came to him very naturally.

“We just provided the means for him to paint and it just started to come out,” she said.

As reported by the Herald earlier this month, the exhibition was planned at this time of year to bring attention to Truth and Reconciliation Day, observed on Sept. 30, which honours residential school survivors and the thousands of children who never made it home.

Sterling-Collins said that he did a couple of orange paintings that have pictographs inspired from their nation,

Wyatt Collins, middle, currently has his exhibition on display at the Nicola Valley Arts Centre.

Wyatt Collins, middle, currently has his exhibition on display at the Nicola Valley Arts Centre.

The art of Wyatt Collins has become a tribute to the National Day For Truth and Reconciliation.

From Page 36

Nlaka’pamux.

“One is the Nlaka’pamux sun with children underneath and the other one is an Nlaka’pamux eagle, which is a very powerful symbol,” she said.

Named as “All Children Are Loved”, both of the designs created by Wyatt have become tributes to Orange Shirt Day. Sterling-Collins said that Wyatt painted both paintings before the unmarked graves were found.

“We really hadn’t decided what we were gonna do with them or what the intent of them was, but as soon as the unmarked graves were found, I felt like he had painted them as a tribute to that,” she said.

The exhibition called “Our Tmixw – Celebrating the Land We Are On” also displays colourful paintings that portray the landscape and wildlife of the region.

Sterling-Collins said she and her family are really excited and proud of Wyatt, and hope everyone goes check it out.

“We’re excited that the community and the art gallery are so supportive of Wyatt and his work. We’re just happy to be here and proud to share what he’s done with everybody.”

The exhibition is planned to stay until Oct. 15 at the Nicola Valley Arts Centre gallery.

Nicola Valley Institute of Technology held a gathering to mark the beginning of fall in a traditional First Nations manner.

Laisa Conde REPORTER@ MERRITTHERALD.COM

With the skies getting darker earlier in the day, temperatures starting to change and trees turning different shades of orange, yellow and red, it means that fall is finally here.

On Wednesday, Sept. 20, faculty members, students and elders from nearby Indigenous communities

gathered at Nicola Valley Institute of Technology (NVIT) to host a change of the seasons ceremony, marking the transition from summer to fall.

The arrival of fall is meaningful to First Nations communities, as it signifies a time of reflection, preparation and gratitude. It marks the beginning of a season when the communities traditionally store food and

See TWO DECADES Page 39

From Page 38

gather medicinal herbs for the winter months.

Faye Ahdemar, a faculty member at NVIT, said they have been hosting the change of seasons ceremony at the institute for 20 years now.

“It’s really become part of NVIT now,” she said.

During the ceremony, songs about gratitude for all their hard work during the summer and the rhythmic beat of drums echoed through the institute and around the fireplace. Participants also had the chance to say their prayers and wishes for the new season.

Ahdemar said that the ceremony is a recognition of all the changes that are happening and its effects, such as the earth and the moon changing positions and resulting in a different constellation in the sky at night and the direction of the wind.

“So for us, it’s not just, you know, the harvesting, it’s everything that is happening in creation at the same time,” she said. “There’s so much going on, at this point in time. The waters change, the winds change direction, things are starting to calm down.”

She said that she hopes those who attended the ceremony walk away understanding themselves a bit better and acknowledge the strength that they have.

“Even if you’re a part (of the ceremony) and you’re non-Indigenous, but you’re part of this, you’re still taking that away, because you’re still human,” Ahdemar said. “It enlarges your knowledge, it enlarges that awareness about connecting yourself to what you’re doing in the world.”