Glossary of key terms in community engagement

Benchmarking visits

Organised trips to completed developments or project phases (ideally of a similar size and scale and with similar constraints) to help people to see what can be achieved and the outcome of their decisions.

Client

Anyone who has construction work carried out for them. They may be property owners, landlords, or businesses.

Community engagement

An approach in architecture and planning that involves inviting local people as partners into the process of decision-making, strategic planning, design, problemsolving, implementation, and evaluation during the development of a project that impacts their everyday lives or local area.

Meaningful and effective community engagement supports social value by building trust with and within community groups, and promoting local social cohesion, capacities, empowerment and education. It can improve planning and design outcomes by supporting efficient implementation

of decisions, reducing financial risk, garnering local support, and generating well-used projects that more efficiently and effectively respond to the needs of their users.

Co-design

An approach to design attempting to actively involve all stakeholders in the process to ensure the result meets their needs. The approach believes that users should be central to the design process as experts in their life experience and local environment.

Co-housing

An intentional community made up of semicommunal housing as a living system. These initiatives aim to develop housing projects that promote community and interaction amongst residents.

Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL)

An obligatory financial contribution by owners or developers of land to local authorities which is used to fund new projects and infrastructure that

benefits the local area. Introduced by the Planning Act 2008, CIL is applied on a much wider range of developments than S106 (see Section 106), and according to a published set of tariffs. It is eventually intended to largely replace S106.

Community Land Trust (CLT)

Independent non-profit organisation made up of community members, that owns, controls, and develops shared land for the benefit of their community, typically affordable housing, civic buildings, shared workspaces, community gardens and energy schemes.

Contractor

The organisations employed to carry out construction works, responsible for providing related material, labour, equipment and services. Specialised sub-contractors may be employed to perform parts of the construction work.

Development

Under the 1990 Town and Country Planning Act, development is defined as “the carrying out of building, engineering, mining or other operation in, on, over or under land, or the making of any material change in the use of any building or other land.” Most forms of development require planning permission.

Evidence Base

A body of information and knowledge collected from previous research and experience.

Housing needs assessment

A comprehensive analysis of housing needs in an area by local authorities, through the analysis of demographic data, economic trends, government policies, existing housing and community characteristics, and feedback from local stakeholders. It is used to identify housing issues and solutions, make strategic decisions related to the housing market, as a basis for policy decisions, and to secure finance for housing projects.

Layout

The way that buildings, routes and open spaces are organised in relation to each other.

Life Cycle Assessment

In architecture, life cycle assessments seek to quantify and analyse the energy use and environmental impacts associated with all phases of a building’s life cycle including procurement, construction, operation and decommissioning.

Master Plan

An overarching set of guidelines and framework for the long-term development vision of a project, neighbourhood, city or region. It is a planning document that outlines what would be the best use of land, and the overall approach to its spatial layout.

Objectives and indicators

Objectives are what is trying to be achieved, whilst indicators are a way of measuring to what extent those objectives are being achieved.

Planning brief

Summarises a planning authority’s requirements and guidance for the development of a site. They are written to guide developers and explain the matters that need to be addressed in planning applications.

Planning submission

The moment when a project is submitted to the appropriate local authority for statutory review through a planning application. At this point, it is decided whether the proposed development will be suitable to be built in an area and given planning permission.

Planning permission

Formal approval from a local authority to carry out building works. Planning permission is required by law when someone wishes to build something new, make a major change to a building, or change the use of a building. This must be applied for through planning applications.

Post-occupancy evaluation

A way of collecting feedback about a project’s performance after being built and used, for example in relation to the costs of running it, health and safety procedures, and the satisfaction of those who live and work there. Following an evaluation, any issues can be addressed and valuable lessons are provided for the future projects.

Precedent

Best-practice example projects that can be used to inspire and act as a comparative tool for a project that is being developed.

Procurement routes

The process or strategy to obtain the necessary technical services for construction.

Public Realm

External spaces within villages, towns or cities that are accessible to everyone, including streets, squares, parks, and other rights of way.

Qualitative / quantitative research

Different approaches to data collection and analysis in research. Quantitative research refers to numeric data or information that can be quantified, counted or measured. Qualitative research is descriptive and is focused on the reasons, meanings, and perceptions behind the numbers.

Regeneration

The renewal of economic, social and environmental factors in rural and urban areas with the aim of promoting them to thrive again, for instance through job creation or environmental improvement.

Resident ballot

A system of voting secretly for residents to support or oppose decisions on a development.

Resident or community brief

A list of requirements or objectives that a group

of community members collaboratively develop and continue to refer to during an engagement process that summarises their aspirations for a project.

RIAI

The Royal Institution of Architects of Ireland (RIAI), founded in 1839, is a professional body in the Republic of Ireland who aim to improve and uphold high standards in architecture, provide impartial advice and information, and promoting the value that architecture can bring to society.

RIAI Work Stages

Within the ‘RIAI Standard Agreement for Architectural services’ Edition 2, Sep 2016 the list of standard architectural services during the design and construction of a project are provided and broken into 8 defined work stages. Usually these would form the breakdown for architectural works for the majority of work outside of the public sector.

RIBA

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) is a professional body for architects in the United Kingdom, who, since forming in 1837, aim to deliver high quality buildings and places which promoting social and environmental sustainability.

RIBA Work Stages

Since 1963, the RIBA have published an evolving document and framework– the RIBA Plan of Work – that shows the stages of the design and construction of an architectural project in a simplified way. The 8 key work stages can be used as a guide and a method of managing a project to help organise tasks and different strategies.

Section 106 (S106) Measures a developer must take to reduce the impact their project makes on a community, on legal negotiation with a local planning authority. Set out in the Town and Country Planning Act 1990, an S106 agreement (also known as planning obligations) involves financial contributions by the developer to infrastructure that supports the development, such as schools, public spaces, roads, or affordable housing. S106 agreements are site specific and negotiated on a caseby-case basis to make a planning approval possible where it may otherwise not be accepted.

Site

The piece of land where a development or project is, was, or is planned to be located.

Site visit

Planning officers, architects, communities, councillors, or inspectors may visit a proposed development site to observe it and gain a better idea of how a development may be planned, designed and constructed there.

Social inclusion

In community engagement, including and welcoming all types of people in decision-making processes, no matter their background, age, gender, or ability. In architecture, the design of buildings and open spaces so that they can be accessed and used by everyone, regardless of who they are.

Social value

A concept with multiple interpretations that, within architecture and planning, addresses and captures existing social conditions and the potentially intangible and long-term social impact of future development on communities. It can include things like supporting jobs and apprenticeships, wellbeing generated by design, learning developed through construction, designing with the community, building with local materials. The introduction of the Social Value Act in 2012 in the United Kingdom has led to an increasing desire to demonstrate the social

value of development in addition to more routine measurements of economic value. (See more on Social Value on page 12)

Spatial Planning

Policies and guidance that influence the distributions of people and activities in spaces at different scales.

It goes beyond traditional land use planning to integrate policies for the development and use of land with other policies which influence the nature of places and how they function.

Spatial Vision

A description of how an area might be changed after the completion of the project.

Stakeholder

An individual or group with an interest in an area or project, such as end users, investors, professionals, amenity groups, residents, contractors, subcontractors, neighbours, and local government.

Survey

A method of collecting information and feedback from residents or local people to find out their opinions on a particular topic. Surveys can be distributed by going door to door in a neighbourhood or through digital platforms like social media.

Urban design

The multidisciplinary art of making places through establishing frameworks and carrying out the design of towns, cities, buildings, their surrounding streets, spaces and landscapes, and how people interact within them.

Use

The way in which land or buildings are used.

Viability

Seeks to assess whether a development is possible financially, usually by calculating if the value created by the development is more than what it cost to construct. Many different financial factors must be balanced for a project to be viable (i.e., what is affordable given the available resources).

Note:

These definitions have been provided by Metropolitan Workshop, with the support of the following sources

https://www.architecture.com/ https://www.designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/ https://www.gov.uk/planning-permission-england-wales https://www.labourguide.co.za/health-and-safety/865construction-work-and-the-responsibilities-of-the-client https://www.local.gov.uk/our-support/financial-resilienceand-economic-recovery/procurement/social-valueachieving-community https://www.londoncouncils.gov.uk/

Office of the Deputy Prime Minister (2004). Planning Policy Statement 11: Regional Spatial Strategies, ODPM: London https://www.planningportal.co.uk/services/help/glossary/ https://www.westminster.gov.uk/planning-building-andenvironmental-regulations/planning-policy/other-planningguidance-support-policies/planning-briefs https://www.riai.ie/the-riai https://www.udg.org.uk/

Toolkit of methods and project references

Throughout People Powered Places, it became clear that no single approach to community engagement could be effective for every context, or appropriate for all groups of people. This is why we are developing a community engagement toolkit of methods and project references that we have gathered as a practice and through learning from others. The aim is to harness shared knowledge and experience within one document by collating a wide variety of options that could be helpful when working with local people.

We see it as a constantly growing resource that we will keep adding to as we test out different approaches, and that hopes to facilitate communication between practitioners, clients and communities. On one hand, it may be a helpful reference for practitioners when developing an engagement plan and advocating to clients. On the other, it aims to empower local people by offering concrete examples of potential methods and tools to select and test out on projects.

On the following pages, you will find a short summary of the tool or reference, where you can find out more information, and a suggestion of which professional working stage it might be most appropriate for.

Visualising Viability

Visualising Viability is a MEAD Fellowship funded project by Gemma Holyoak and Michael Kennedy that develops tools to demystify development viability in construction and allow for wider understanding of inherent characters, forces and issues in the process. It is a standalone participatory board game which allows players to play the roles of architect, developer, surveyor and planner to collaboratively build a viable scheme, as well as a publication that acts as a guide to viability modelling.

Find out more: https://www. visualisingviability.com

RIBA Stage 4

Soft Landings Framework

The Soft Landings Framework is a strategy to ensure smooth transition from construction to occupation and that operational performance is optimised. It is intended to be implemented in five main areas:

1. Inception and briefing: Dialogue between designer, constructor, client, end user, and facilities management

2. Design development and review: Review insights from comparable projects and assess proposals with facilities management and building users

3. Pre-handover: Make end users familiar with interfaces and systems before occupation

4. Initial aftercare: Continued involvement of client, design and building team for feedback, fine tuning systems and ensure proper operation for 4-6 weeks

5. Extended aftercare and postoccupancy evaluation: 1-3 years after care and post occupancy evaluation.

Find out more: https://www. designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/ Building_Services_Research_and_ Information_Association_BSRIA

Source: https://bimportal. scottishfuturestrust.org.uk/level2/ stage/1/task/5/determine-the-softsandings-approach

RIBA

Design for Social Sustainability

Design for Social Sustainability is a publication by Social Life, which sets out a framework for planning and designing the service, spaces, housing and governance arrangements to help local communities thrive. It argues that social sustainability has been largely neglected in mainstream sustainability debates, which tend to focus on economic and environmental sustainability in the context of urban planning and housing. Referencing previous studies which show that without the right social infrastructure, new communities can quickly spiral into decline, the publication offers a practical resource to address the question of how to create socially sustainable places.

Find out more: http://www.social-life. co/publication/Social-Sustainability/h

RIBA

Voice Opportunity Power

Voice Opportunity Power is a toolkit aimed at involving young people in the making and managing of their neighbourhoods, jointly developed by ZCD Architects, TCPA, Grosvenor, and Sport England. It is a free resource with practical guidance on how to involve young people (aged 11-18) in the way that places get built and managed. It is intended for use by professionals such as developers, designers, planners and sports providers, and includes 5 toolkit sessions proposed to work within a typical RIBA design programme, starting at Stage 1 until planning submission in Stage 3.

Find out more: https:// voiceopportunitypower.com/

RIBA Stage: 1, 2, 3

Storytelling

A built environment professional’s views of everyday life might be very different to those of a community experiencing change first hand. Modes of communication that take ordinary conversation as a starting point can bring the ‘expert’ from the position of observer to an engaged participant, allowing a much more nuanced understanding of the social history of a place and how it is experienced by people living there. Storytelling helps us use language grounded in everyday experience, and has an imaginative quality that avoids being too idealistic. This helps us move away from professional jargon and communicate in a way that is easily understandable and comfortable for all types of people.

We used storytelling as a communication tool at our project at Wendling Estate and St. Stephen Close, where we invited residents to share their ‘estate memories’ with us. This helped us build up understanding and trust with residents.

We also used a similar approach at our project at Carpenter’s Estate, where we held a ‘Carpenters History Talk’ which helped us achieve a more intimate insight into the collective memories held by the community in the area.

Find out more: see Metropolitan Workshop’s project at Carpenter’s Estate or at Wendling Estate and St. Stephen Close, or read about storytelling at Till, J. (2005): The Negotiation of Hope. p.37

RIBA Stage: 1, 7

Resident Ballot

Since July 2018, any London Borough wishing to carry out an estate regeneration scheme, involving demolition of homes, with Greater London Authority (GLA) funding, will need a successful ballot for a proposal from residents living on the estate. All secure tenants aged 16 and over named on the tenancy, resident leaseholders or anyone else living on the estate who have been on the housing register for the last 12 months prior to a ballot get a yes or no vote. Non resident leaseholders or buy to let landlords cannot vote. In accordance with GLA guidelines, an independent body must carry out the ballot, responsible for voter registration, organising the ballot and counting results. The planning application will be prepared on the basis of the result of the ballot.

A resident ballot was carried out at our project at Carpenter’s Estate. Previously a very contentious project in the local area, as a result of an extensive programme of engagement, 73% of residents voted yes to the proposal, which involved 2,000 new homes being built, refurbishment of 314 existing units, and demolishing of 400.

Find out more: see Metropolitan Workshop’s project at Carpenter’s Estate

RIBA

Newsletters

Newsletters are one possible way that the design and client team could communicate with a community at regular intervals throughout a project duration. They might be sent out digitally and/or distributed physically door to door to reach as many people as possible. Newsletters can provide people with the contact information of the person in charge of communication with local stakeholders, and give them a channel to voice any questions or concerns. They can offer an update about all the activities taking place on the project and invite people to get involved.

We used newsletters as a communication channel for our project at Wendling Estate and St. Stephen Close, which included a ‘Estate News’ section, a timeline of engagement events, summaries of past workshops and events, and announcements of specific dates for upcoming plans.

Find out more: see an example of a newsletter we used at Wendling Estate and St. Stephen Close here https://www.wecanmove.co.uk/ documents/20142/105848467/ WSS+Newsletter+Jan+2019. pdf/8da56c01-3240-3751-0f860ba402f9f43a

RIBA Stage: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Understanding Woodberry Down

On their work at Woodberry Down Estate in Hackney, one of the largest estate regeneration schemes in London, Social Life carried out research alongside regeneration partners to explore everyday life and how residents feel about regeneration and change. From this, they developed a social impact measurement framework that will help understand and assess the impact of the redevelopment over the following 15 years on the people living in the area. They undertook a mixed method approach including door-to-door surveys, semi-structured interviews, focus groups with young people, site surveys and review of official data.

Find out more: http://www.sociallife.co/publication/understanding_ woodberry_down/

RIBA Stage: 0, 1, 7

Trading Places

Trading Places is an independent research project conducted by Social Life in 2014, to understand how a diverse group of traders in the Elephant & Castle Shopping Centre were being affected by regeneration. The aim was to understand the shopping centre’s social value, and how proposed changes were affecting people now and how they will impact on traders and customers’ businesses, livelihoods, friendships and local relationships in the future. Through interviews with 34 traders to capture their stories and photographic portraits, Social Life produced a report, organised a local exhibition, and shared the findings with local groups.

Find out more: http://www.social-life. co/publication/trading_places/

RIBA Stage: 0, 1, 7

‘Community Consultation For Quality Of Life’ (CQOL)

CQOL is a map-based model of community engagement based on University of Reading’s Mapping Eco Social Assets project, envisioned as a way of working alongside local people to capture the knowledge they have of their community. CCQOL asks community members to create maps of their local area in both community spaces and online, identifying different things about their neighbourhoods that are important for their health and wellbeing. Ultimately, these maps are seen as a way of identifying what elements of buildings and infrastructure are socially valuable, to improve quality of life for all.

Find out more: http://ccqol.org/about/

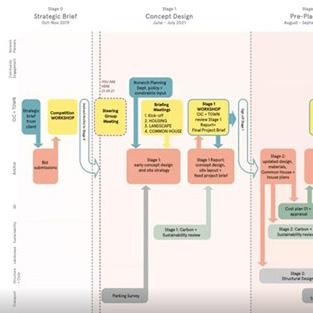

Project flowchart

Flowchart developed alongside the community to graphically capture the project process

Find out more: Archio

RIBA stage: 1

Meanwhile projects

Meanwhile projects are an approach to using empty buildings or sites productively in the period after a space has been vacated and a new occupant is found, or if parts of a site are not yet under construction. Empty buildings or sites can strongly affect the appearance and use of an area, particularly in city centres; meanwhile projects can occupy empty spaces in the short term until a longer-term solution can be found. This helps keep an area vibrant and useful, creating opportunities for the neighbourhood. For example, these can include pop-up shops, exhibition spaces, meeting areas for the community, a space for training and learning, or a community rehearsal space.

Image: https://www.vts.com/blog/ meanwhile-space-cre-what-is-it-howto-make-it-worthwhile

Find out more: https://www. designingbuildings.co.uk/wiki/ Meanwhile_use_of_buildings

RIBA Stage 0

Local resident work experience

There is often a missed opportunity on new developments to generate high quality job opportunities, career paths, and educational opportunities for residents and young people who live in areas undergoing change, and who are directly impacted by development. A solution to this is to include local hire requirements in any development plan, ensuring that projects present various employment opportunities, apprenticeships, and work experience for the community. This also means that local people have access to career paths and better wages that might not have been available to them otherwise. The benefits can include career paths into the construction industry, for example with opportunities for apprenticeships in architecture practices or on construction sites. Through these job windows they can gain new skills that can be applied elsewhere. Ultimately, the whole project can be seen as an opportunity for education and employment, generating value for the local area.

Image: https://www. georgetownclimate.org/adaptation/ toolkits/equitable-adaptation-toolkit/ local-hiring-requirements-orincentives.html

Find out more: https://www. forworkingfamilies.org/resources/ publications/making-developmentwork-local-residents-local-hireprograms-and

RIBA Social Value Toolkit

Guidance from the RIBA and the University of Reading on evaluating the social value impact on people and communities delivered by a project.

The Social Value Toolkit for Architecture has been developed to make it simple to evaluate and demonstrate the social impact of design on people and communities.

Social value outcomes are increasingly being considered necessary benefits in public and private procurement through quality scores of bids and tenders. To provide evidence that meets these key performance targets and metrics, practices need to demonstrate value quantitatively and this toolkit provides a post occupancy evaluation survey and methodology for reporting social value as a financial return on investment.

Download the guidance below to hear from some of these researchers on how their practice is building social value into their projects and design processes.

https://www.architecture.com/ knowledge-and-resources/resourceslanding-page/social-value-toolkit-forarchitecture

Social value: a brief introduction

Words by Shaun Matthews, Metropolitan WorkshopThe importance of developing an intrinsic understanding of the subjective and social aspects of the built environment has been increasingly understood by many architects and planners. Yet within a society defined through objective and quantifiable measures of sustainability, equity, and development, these values are often overlooked in design projects. Moreover, it remains a challenge to effectively communicate such values to clients, as well as the users of the spaces.

This is where the idea of measuring social value comes into play. Although the concept is not new, interest in the UK has grown since the Social Value Act in 2012, and an increasing desire to demonstrate the social value of development in addition to more routine measurements of economic value (Raiden, et al, 2018; UKGBC, 2019). Social value is used to capture a range of different values associated with factors like health and wellbeing, community activities, public transport, tackling deprivation and crime, and is often linked to social enterprise (Serin et al., 2018). The 2012 Act requires public authorities to have regard for economic, social and environmental wellbeing in connection to public services, including the NHS, housing associations and local authorities. Within the disciplines of architecture and planning, the concept of social value is powerful because it addresses the social conditions of existing contexts and the potentially intangible, long-term, and impactful social benefits of future development.

Samuel and Hatleskog (2020, p.8).

“As societies face impending challenges relating to climate change, densification and social upheaval, now is an opportune moment to discuss what we value most and how architects and architecture can play a role in improving people’s lives.”

Figure

Five Overlapping

of the Social Value of Architecture (RIBA, 2020, p.6).

Fig. 2: Design Value Constituents (Samuel and Hatkeskog, 2018, p.9)

Figure 2: Design Value Constituents (Samuel and Hatkeskog, 2018, p.9).

References

Hatleskog, E. and Samuel, F. (2021a) ‘Mapping as a strategic tool for evidencing social values and supporting joined up decision making in Reading, England’, Journal of Urban Design, DOI: 10.1080/13574809.2021.1890555

Hatleskog, E. and Samuel, F. (2021b) ‘Mapping social values’, The Journal of Architecture, 26(1), pp.56 58, DOI: 10.1080/13602365.2021.1883892

Raiden, A., Loosemore, M., King, A. and Gorse, C. (2018) Social Value in Construction, Abingdon, Oxon.: Routledge.

the ability of the built environment to foster positive emotions, connect inhabitants with nature and one another, encourage active and diverse lifestyles, and facilitate a sense of agency (Samuel, 2018). Furthermore, it recognises the value in sourcing local materials and labour, encouraging resident participation, and supporting communities in designing and building their homes and neighbourhoods (RIBA, 2020). It has been characterised through five categories, including: jobs and apprenticeships, wellbeing generated by design, learning developed through construction, designing within the community, and building with local materials (Fig 1).

RIBA. (2020). Social Value Toolkit London: RIBA.

Social value may be considered as contributing to design value, a design-orientated adaption of the established concept of sustainable development (RIBA, 2020) (Fig 2).

Samuel, F. (2018). Why architects matter: Evidencing and communicating the value of architects, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Samuel, F. and Hatleskog, E. (eds.) (2020). Social Value in Architecture. Architectural Design, 90(4). Available at: https://onlinelibrary wiley com.bris.idm.oclc.org/journal/15542769

Ben Derbyshire (RIBA, 2020, p.3)

Serin, S., Kenny, T., White, J. and Samuel, F. (2018) Design Value at the Neighbourhood Scale: What doe s it mean and how do we measure it?, Glasgow University: CACHE.

UKGBC (2019). Driving social value in new development: options for local authorities . London: UK Green Building Council.

Unlike the other well-known constituents of design value (i.e. economic and environmental value), social value has received far less recognition, in part due to difficulties in defining and measuring its benefits. However, recent frameworks such as the Royal Institute for British Architects’ (RIBA) Social Value Toolkit offer a means of measuring social value which supports planners and architects in articulating the benefits of social value both qualitatively and quantitatively (RIBA, 2020). While monetising social value may be problematic, it might also offer a real opportunity to demonstrate and communicate social value within a construction industry so heavily defined by economic quantifiability.

On one hand, demonstrating the short, medium and long-term social value of a proposal or approach may be advantageous during client-side procurement processes. On the other hand, developing new approaches to mapping, predicting and measuring social value may offer architects and planners a new means of both understanding as well as transparently communicating the less tangible benefits and compromises to communities during participatory planning and design processes (Hatleskog and Samuel, 2021a; 2021b)

Notes:

References listed under the References and Further Reading section of this document.

Read about our expert-led workshop on Social Value in the Process and Reflections document.

“… Economic viability has dominated planning negotiations and development outcomes; not always resulting in lasting quality or sustainable wider societal benefit.”

References and further reading

Arnstein, S. (1969) ‘A Ladder of Citizen Participation.’ Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35 (4), pp.216–224, DOI: 10.1080/01944366908977225

Blundell-Jones, P., Petrescu, D., Till, J. (eds.) (2005) Architecture and Participation. Routledge, London

Bornat, D. (2017) ‘Designing for Play’. In: Harrow Council Design Unit (eds): Between Edges and Hedges, pp.7072. Available at: https://www.east.uk.com/wp-content/ uploads/2018/12/%E2%80%93between-edges-andhedges.pdf

Bornat, D. and Shaw, B. (2019) Neighbourhood Design: Working with children towards a child friendly city. London: ZCD Architects.

Brownhill, S., Geraint, E., Inch, A. and Sartorio, F. (2019) ‘Older but not wiser – Skeffington 50 years on.’ Town and Country Planning, 88(3/4), pp.122-125, available at: https://orca.cf.ac.uk/135860/1/F%20Sartorio%202020%20 older%20but%20no%20wiser%20pub%20ver.pdf

Design Council and CABE (n.d.). Briefing paper: a neighbourhood guide to viability Department for Communities and Local Government. Available at: https:// www.designcouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/asset/ document/cld_briefing%20papers__VIABILITY_FINAL.pdf

Forester, J. (1989) Planning in the Face of Power University of California Press, London, Berkeley and Los Angeles

Frank, K.I. (2006). The Potential of Youth Participation in Planning. Journal of Planning Literature, 20, pp.351–371.

Gill, T. (2021) Urban Playground: How Child-Friendly Planning and Design Can Save Cities. London: RIBA Publishing.

Harvey, D. (2008). ‘The Right to the City’. New Left Review, 53, pp.23-40

Hatleskog, E. and Samuel, F. (2021a) ‘Mapping as a strategic tool for evidencing social values and supporting joined-up decision making in Reading, England’, Journal of Urban Design, DOI: 10.1080/13574809.2021.1890555

Hatleskog, E. and Samuel, F. (2021b) ‘Mapping social values’, The Journal of Architecture, 26(1), pp.56-58, DOI: 10.1080/13602365.2021.1883892 HMSO (1969)

‘People and Planning: Report of the Committee on Public Participation in Planning’. Skeffington Report, London

The Housing Agency (2020). Social, affordable and cooperative housing in Europe: Case studies from Switzerland, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark. Available at: https://www.housingagency. ie/sites/default/files/2020-12/Social%2C%20 affordable%2C%20and%20co-operative%20housing%20 in%20Europe%20(2).pdf

Kearns, K. (1997) Dublin Street Life and Lore – An Oral History of Dublin’s Streets and their Inhabitants. Dublin: Gill Books.

Mouffe, C. (1999) ‘Deliberative Democracy or Agonistic Pluralism?’ Prospects for Democracy, 66(3), pp.745-758

Mulgan, G. (2010) ‘Measuring Social Value.’ Stanford Social Innovation Review. Leland Stanford Jr. University, pp.37-43. Available at: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/ measuring_social_value#

Nordström, M. and Wales, M. (2019) ‘Enhancing urban transformative capacity through children’s participation in planning’. Ambio, 48, pp.507–514.

O’Donnell T. and Flynn, P. (2021). Roadmapping a Viable community-Led Housing Sector for Ireland. SOA Research CLG. Available at: https://soa.ie/

Parvin, A., Saxby, D., Cerulli, C., and Schneider, T. (2011). A Right to Build: The next mass-housebuilding

industry. University of Sheffield School of Architecture and Architecture 00/:. Available at: https://static1.squarespace. com/static/5a9837aa8f513076715a4606/t/5eac3dafcdbf fc0abd29ce95/1588346311289/RIGHT+TO+BUILD_LR.pdf

Raiden, A., Loosemore, M., King, A. and Gorse, C. (2018) Social Value in Construction, Abingdon, Oxon.: Routledge.

RIBA. (2020). Social Value Toolkit. London: RIBA.

Samuel, F. (2018). Why architects matter: Evidencing and communicating the value of architects, Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Samuel, F. and Hatleskog, E. (eds.) (2020). Social Value in Architecture. Architectural Design, 90(4). Available at: https://onlinelibrary-wiley-com.bris.idm.oclc.org/ journal/15542769

Serin, S., Kenny, T., White, J. and Samuel, F. (2018) Design Value at the Neighbourhood Scale: What does it mean and how do we measure it?, Glasgow University: CACHE.

Shtebunaev, S. (2020) 10 Reasons: Giving young adults voice & power over what gets built: advocating for youth participation in planning, regeneration, and neighbourhood management. Grosvenor. Available at: https://www.grosvenor.com/Grosvenor/files/c5/c5487204eae2-4a54-9cf8-13445d2bc6a5.pdf

Stevenson, F. and Rijal, H. (2010). Developing occupancy feedback from a prototype to improve housing production. Building Research and Information. 38(5), pp. 549-563.

Stickells, L. (2011) ‘The Right to The City: Rethinking Architecture’s Social Significance’. Architectural Theory Review, 16(3), pp.213-227

UKGBC (2019). Driving social value in new development: options for local authorities. London: UK Green Building Council.

ZCD Architects and Grosvenor (2021) Voice Opportunity Power: a toolkit to involve young people in their neighbourhoods. Avaliable at: https:// voiceopportunitypower.com/

Project publications and dissemination

Ava Lynam, Dhruv Sookhoo, Lee Mallett, and Neil Deely. (2021) People Powered Places (Prospects 2, working paper), London: Metropolitan Workshop.

Kruti Patel and Dhruv Sookhoo. (2021) Oakfield Village: A Healthier Kind of Suburb, Newcastle upon Tyne: Newcastle University. Guest lecture delivered to Masters of Urban Design and Masters of Architecture students as part of Principles and Practice of Urban Design.

Dhruv Sookhoo. (2021) Fundamentals for Creating Local Identity/ Use, Activity and Supporting Community Life (Code School), London: Urban Design London.

Dhruv Sookhoo and Jonny McKenna. (2021) People, Powered, Places: A context for community participation in planning and development, Land Development Agency, Dublin.

Metropolitan Workshop (2021) People Powered Places, in Irish Architecture Foundation. (2021) Re-Imagine [Online-Internet]. Available at: https://reimagineplace.ie/ (accessed: July 2021). Paper featured in IAF Placemaking Resources.

Denise Murray and Jonny McKenna. (2021) People Powered Places, RIAI Conference 2021, RIAI: Dublin, 03 November 2021. Available at: https://www.riai.ie/whats-on/ riai-conference/riai-conference-2021/programme/3-nov