BEYOND THE CLASSROOM INNOVATIVE MODEL SPACES IN PRESCHOOL EDUCATION POLITECNICO DI MILANO SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, URBAN PLANNING AND CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN 2021/2022 Candidate: Michele Laurante - 946188 Supervisor: Prof. Cassandra Cozza

2

POLITECNICO DI MILANO

SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, URBAN PLANNING AND CONSTRUCTION ENGINEERING

BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

INNOVATIVE MODEL SPACES I N PRESCHOOL EDUCATION

July degree session

Candidate: Michele Laurante - 946188

Supervisor: Prof. Cassandra Cozza

Year 2021/2022

3

Academic

4

To my family and Daria,

5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

0.0 Abstract

0.1 Introduction

CHAPTER I - THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

1.0 Shaping education

1.1 The italian scenario

Principles

Centrality of the student

Organization of the curriculum

1.2 Italian education system

Integrated system 0-6

Pedagogical guidelines 0-6

Curriculum and design 0-6

1.3 Kindergarten

Organization of the day

Legislative background

1.4 Typology applied to legislation

Exterior Interior

1.5 Future Guidelines

CHAPTER II - BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

2.0 The environment as a teacher

2.1 Architecture and Pedagogy Montessori

Reggio Model

2.2 Reggio approach

Diana school Background, methodology and principle

2.3 Learning from reality

12 11 20 24 28 32 38 45 48 52 60

Jacaranda school

Personal overview

6 17

CHAPTER III - THINKING OUTSIDE THE BOX

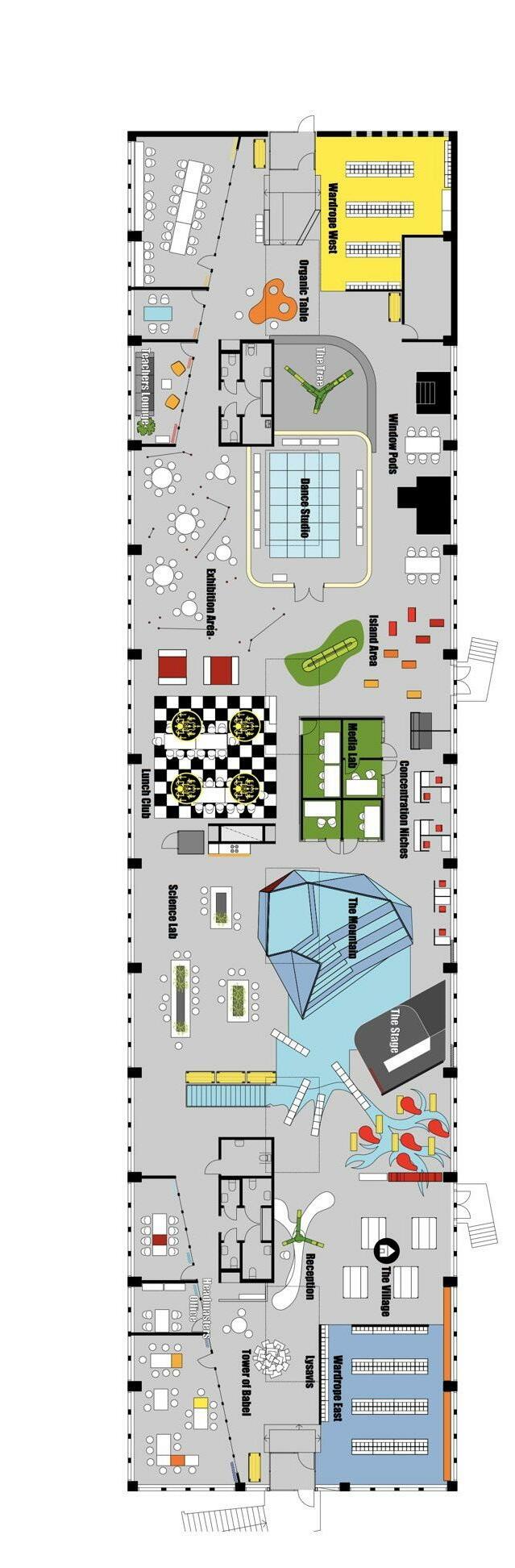

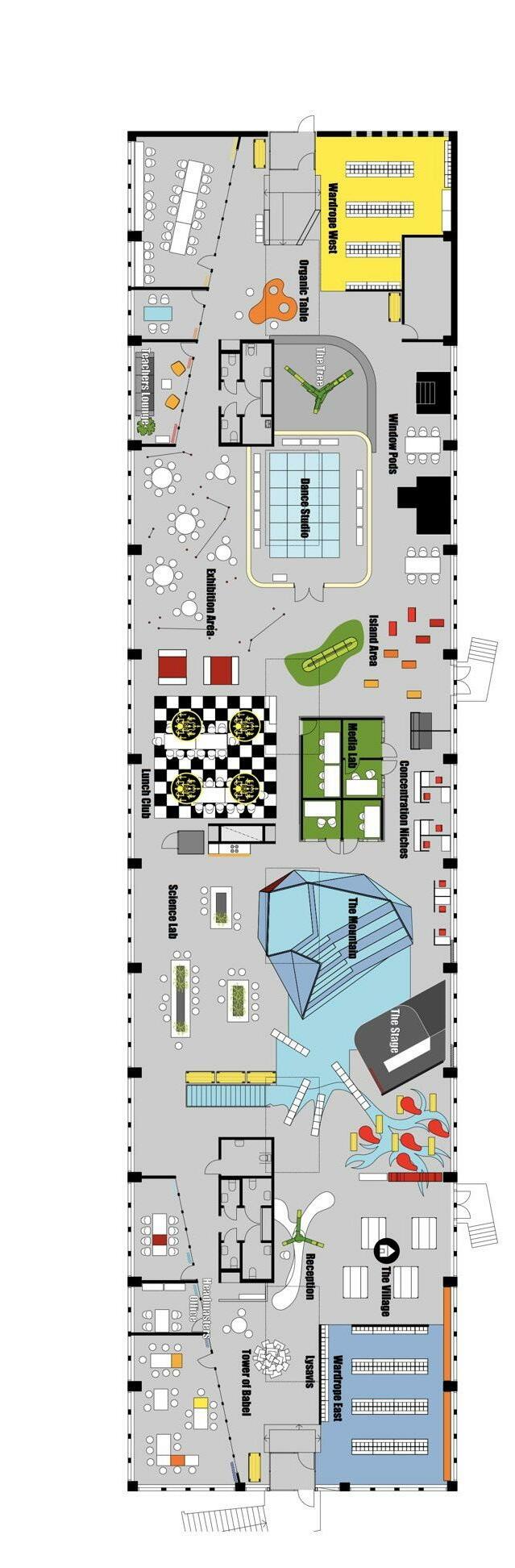

3.0 A need to experiment: Case study collection

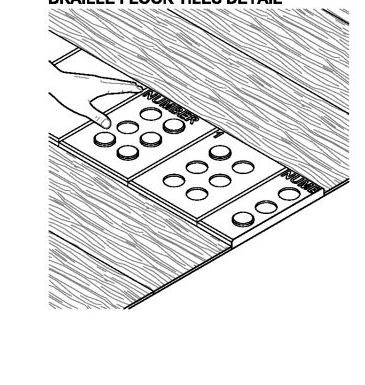

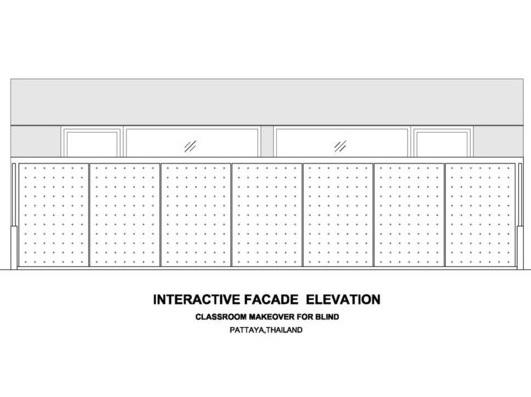

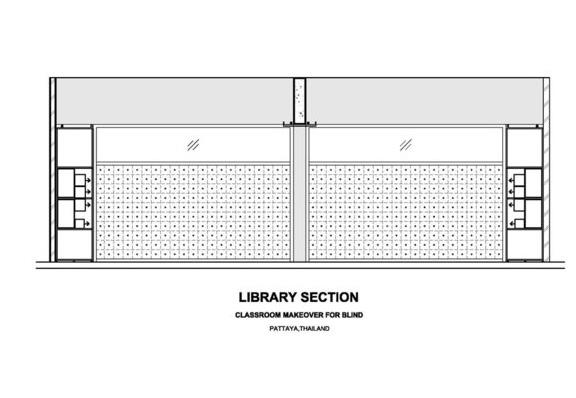

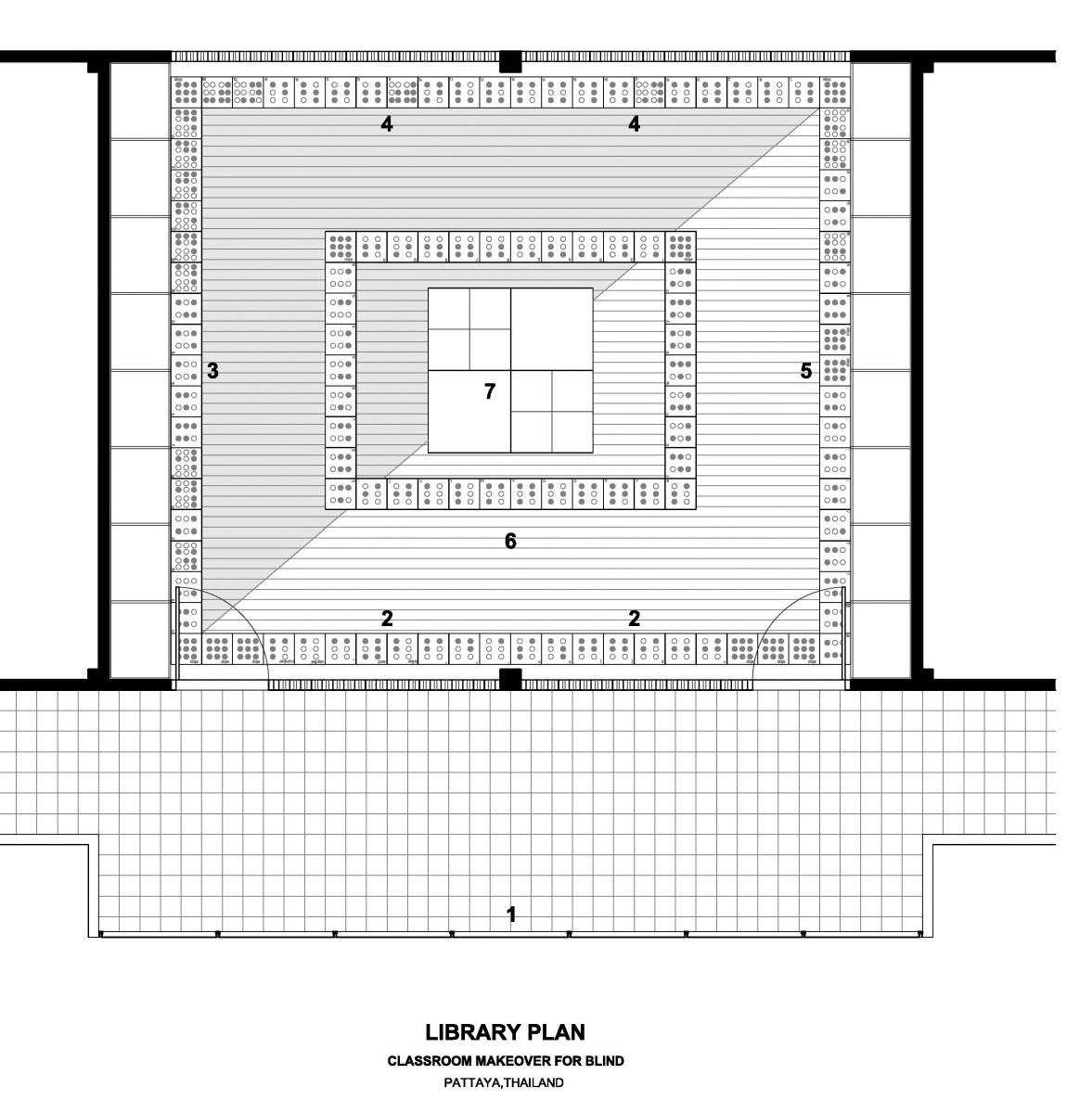

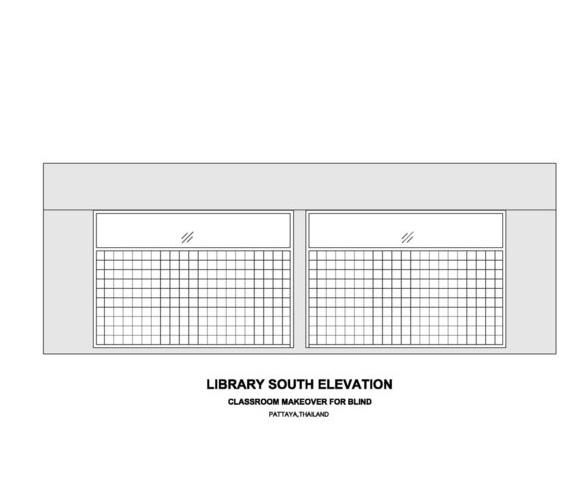

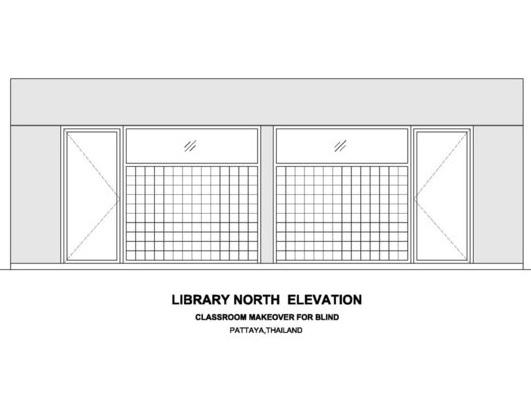

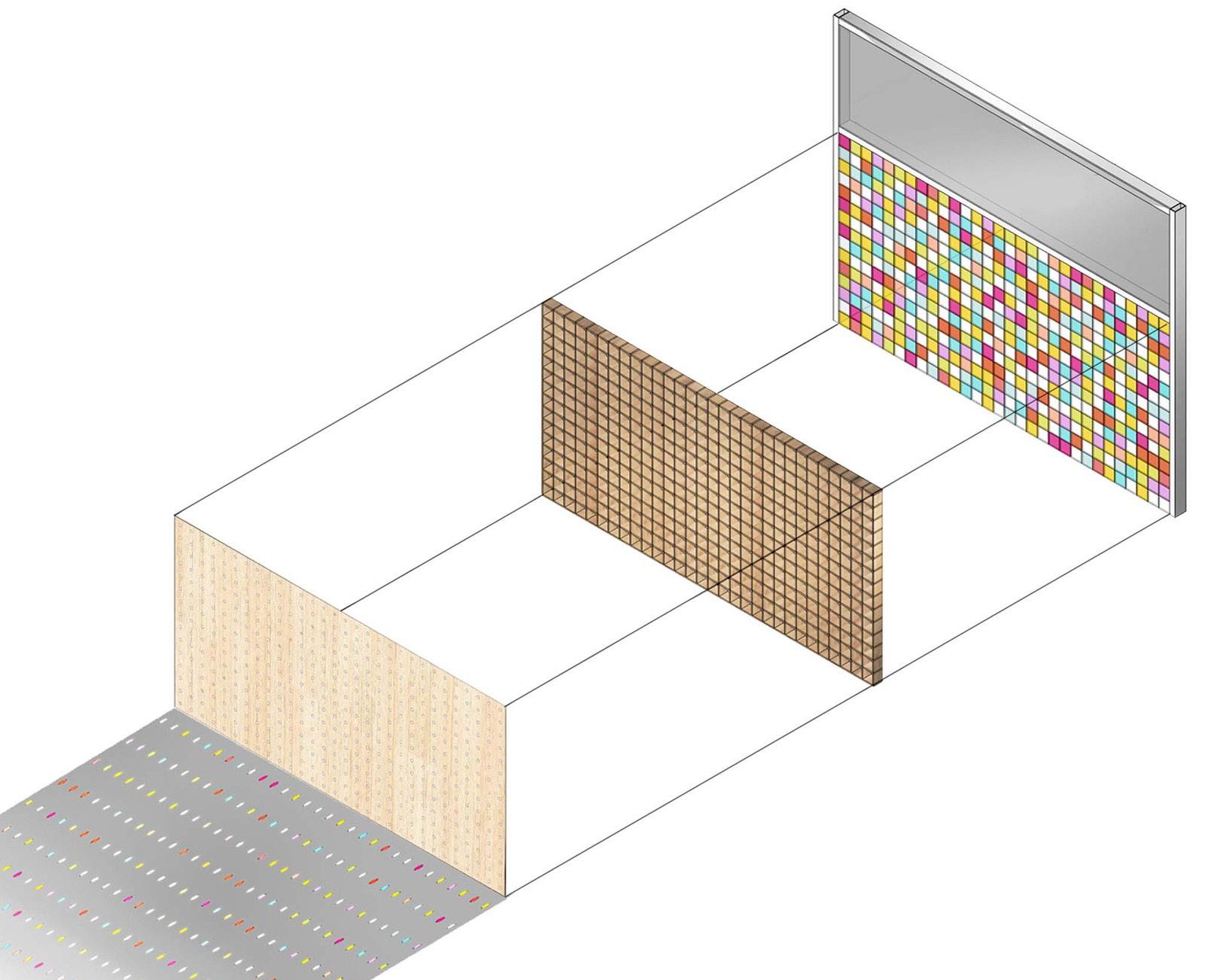

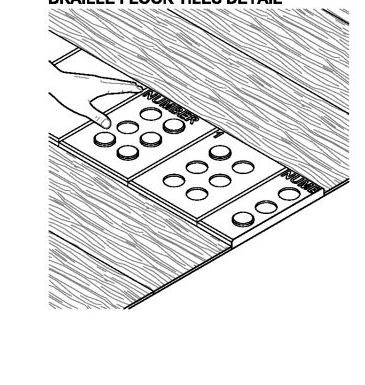

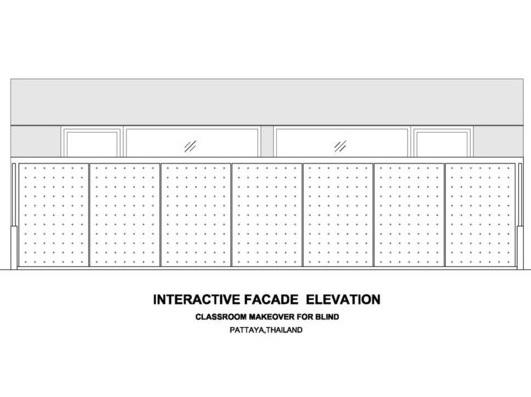

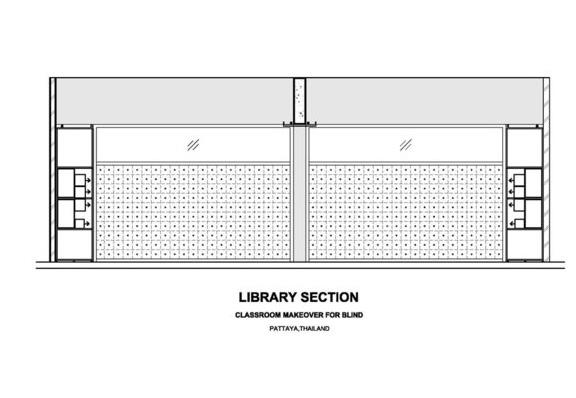

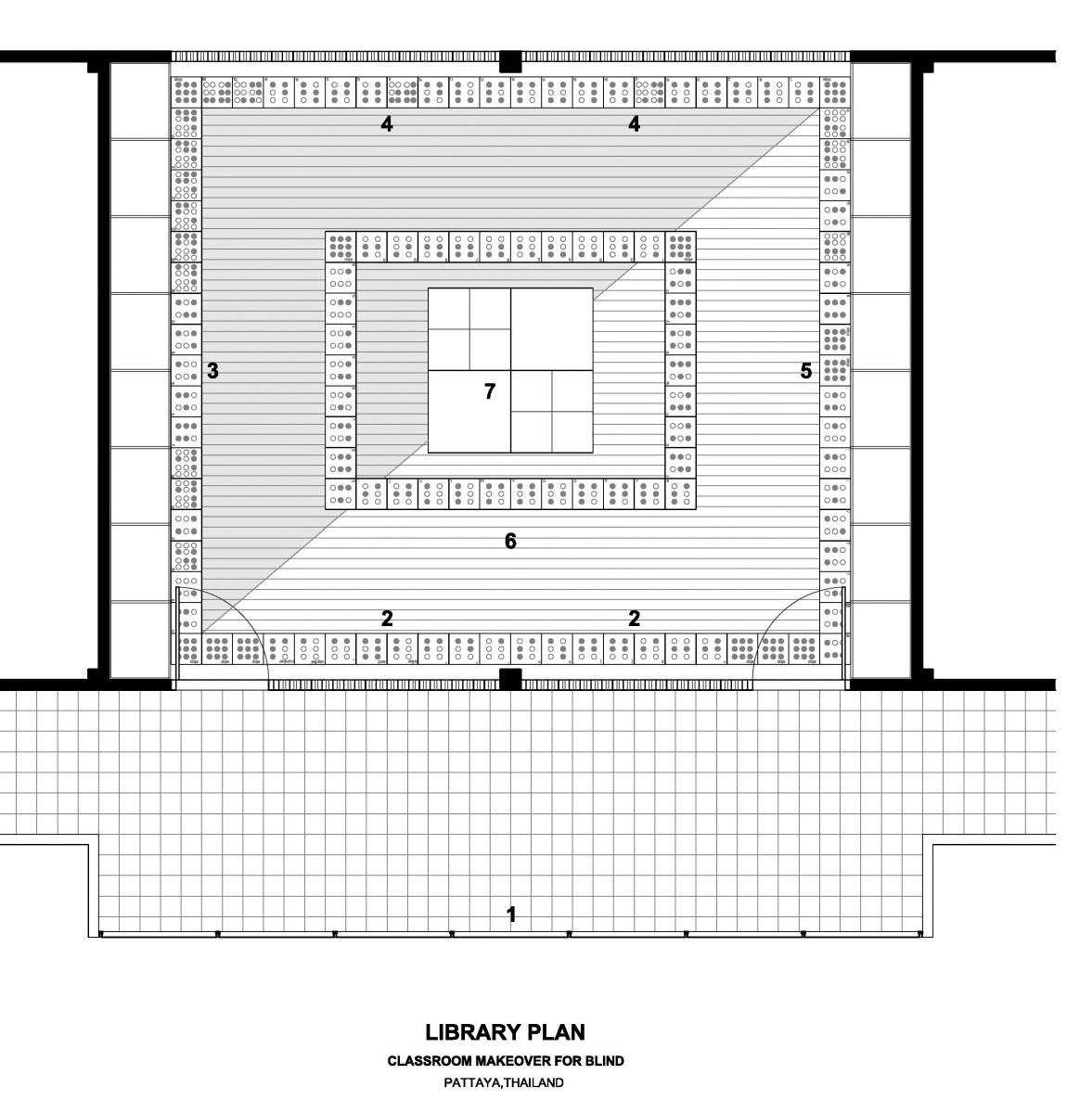

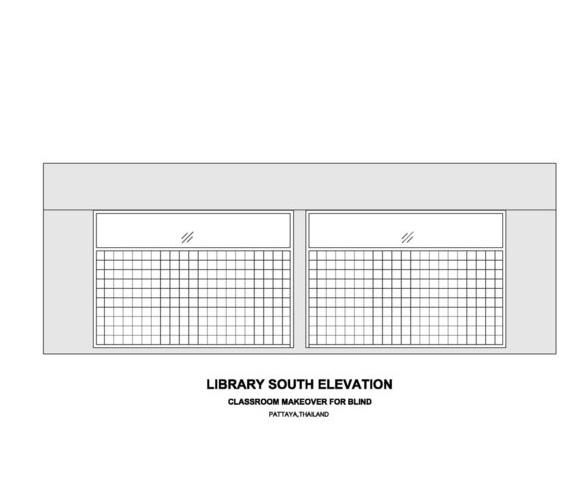

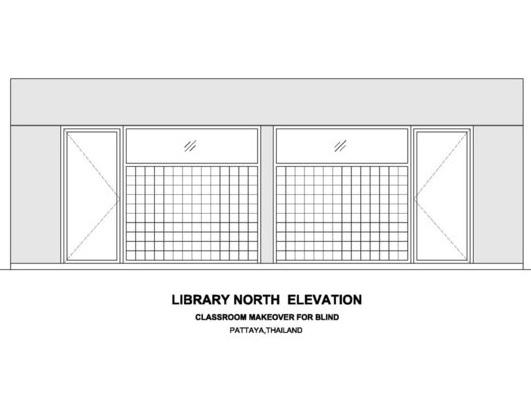

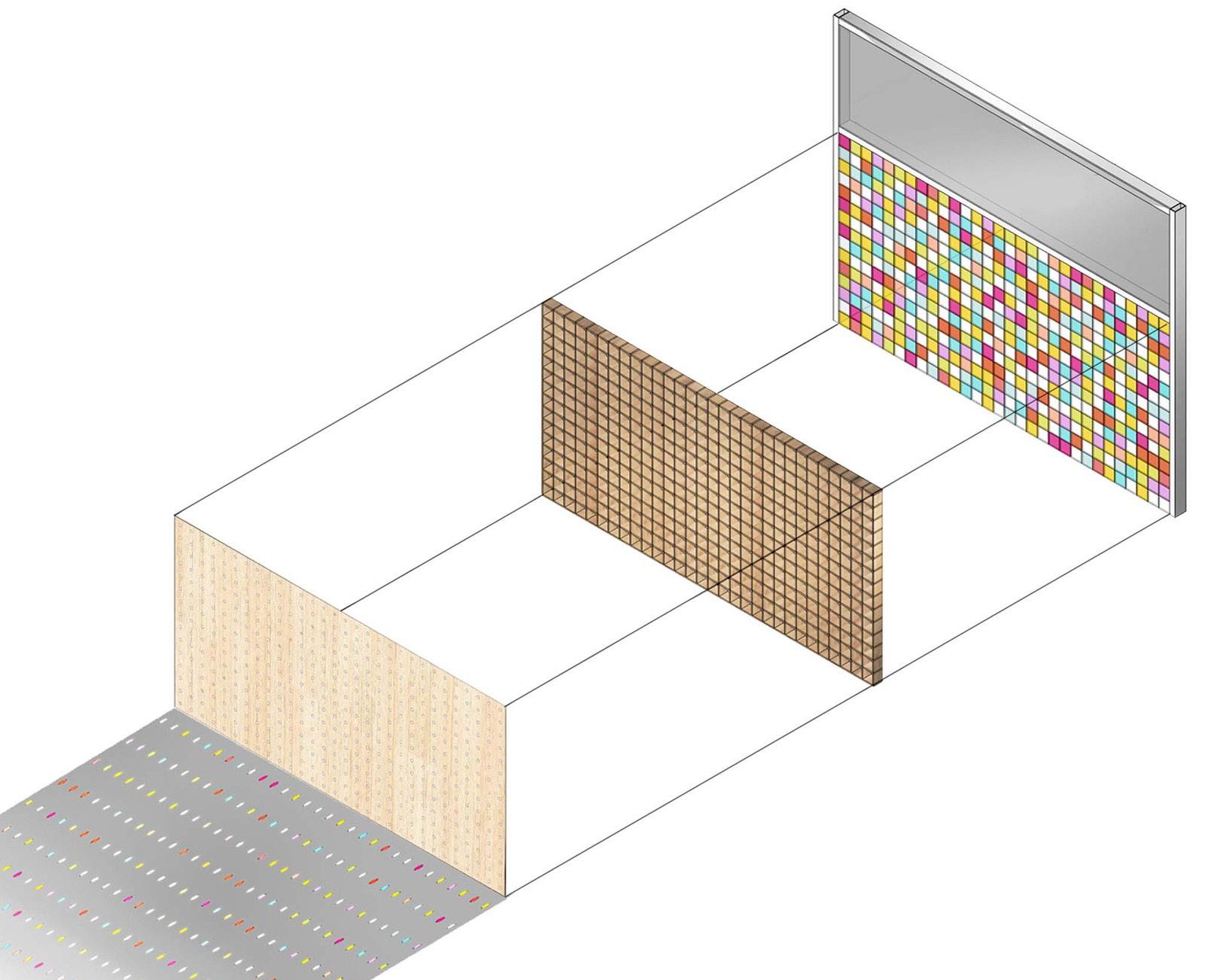

3.1 Sensory School Classroom makeover for the blind

Kita Sinneswandel

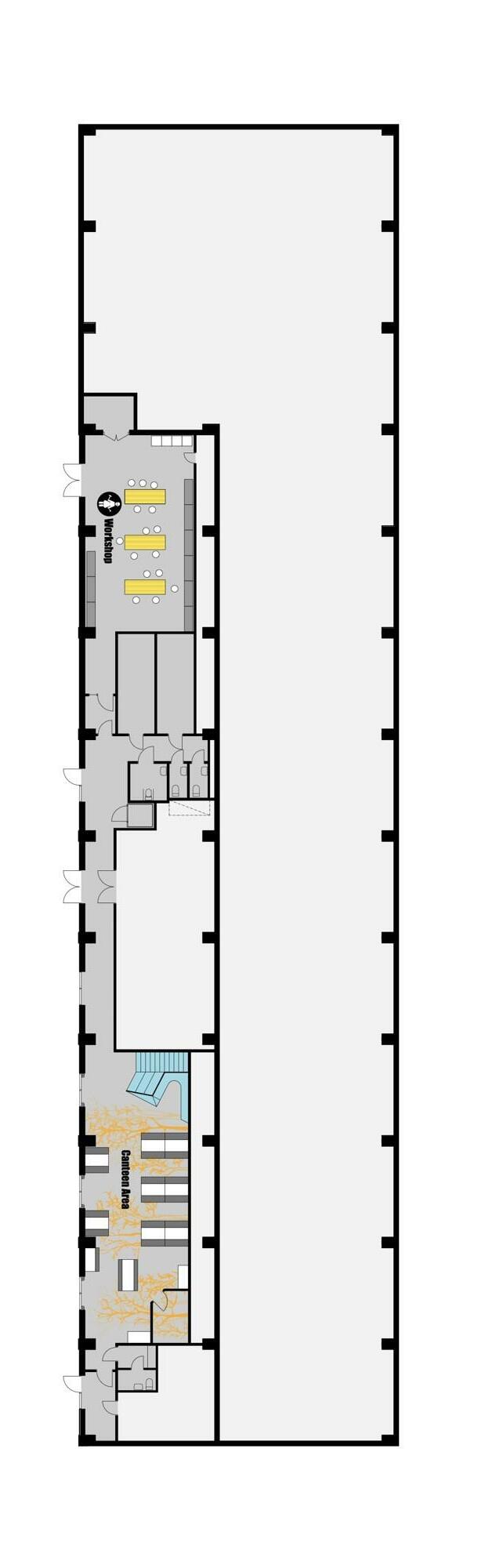

3.2 Flexible school

Kita Sinneswandel Fuji kindergarten

3.3 School without School without bags Vittra Telefonplan

CONCLUSION

4.0 Conclusion

Beyond the classroom: Manifesto

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SITOGRAPHY

92

7 71 73 83 100 104

Understanding the regulations that rule the italian curriculum

THE ITALIAN SCENARIO

ITALIAN SCHOOL CURRICULUM: SPACE AND REGULATIONS

0-6

EDUCATION CURRICULUM

PEDAGOGICAL GUIDELINES

Regulation applied to typology

Pedagogical models

PEDAGOGY AND SPACE

Space as a third educator

ARCHITECTURE

BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

INNOVATIVE PRESCHOOL MODEL

Montessori

LEARNING FROM REALITY

Case study Jacarandà Reggio Approach

PEDAGOGY

8 Malaguzzi - Reggio Approach

PHILOSOPHER

1

2

HOW DOES IT REFLECT IN THE ARCHITECTURAL SPACE?

FLEXIBILITY

WHY SCHOOLS ARE CHANGING ?

SCHOOLS ARE CHANGING

Pedagogical experimentation

Flexible schools

Sensory School

School without

THINKINING OUTSIDE THE BOX

INTERNATIONAL PRESCHOOL MODEL

INCLUSIVITY

9 3

Fig. 0.1

Playwall by Eureka, Hong Kong 2020

10

This thesis observes the attempts to introduce innovative design approaches to the Italian preschool education system. It aims to discuss the importance of open, flexible and child-centred spaces by proposing new learning environments for the early childhood development apparatus.

Specifically, it reviews theoretical approaches concerning the correlation between pedagogy and architecture design, and its influence on understanding how children experience life in educational settings should be an imperative for educational practitioners, teachers, and researchers.

The study starts out by investigating the Italian scenario through its regulations, looking to unveil the fragile connection between the norms and their actual application within the pedagogical-architectural framework.

Furthermore, the research examines several innovative preschool models that exemplify the main arguments proposed through their design. Using pedagogy as the base for investigating the architectural identity of these spaces, some critical parameters are identified as being fundamental to the practical design of early years’ environments.

In conclusion, by analysing some key concepts that deal with the flexibility of an educational space, the dissertation will propose new guidelines that will identify a new shared language between the pedagogical and architectural fields.

11

0.0 ABSTRACT

A child’s first journey outside her or his home environment is likely to occur within a preschool setting. The child is let into an unfamiliar world, away from his home and without the guardianship of those who kept an eye on him. Thus, pushed by an innate sense of curiosity, he begins an exploration. The sights, the sounds, and the smells start drawing up an initial picture in the child’s mind of what this place is all about. These first perceptions will stir up dispositions that motivate the child’s subsequent action: curiosity, retreat or focused observation, types of actions that will inevitably be influenced by the way the child is made to feel within his/ her new space: the school.

With children spending increasing amounts of time within early years’ facilities, and as regular performance impacts the course of a child’s early developmental process, the concern for the form and quality of activity becomes crucial. While the daily program is primarily left up to the designated figures to run and manage the activities, the physical structure, which plays host to such aspects, assumes a significant role in giving shape and substance to how teaching unfolds.

Undeniably, as the carer is trained to respond in a particular manner to a child’s queries, so the physical environment provides opportunities that respond to a child’s innate inquisitiveness, foster decision-making and further their spirit for self-guided exploration.

This latter aspect calls the need for a critical awareness towards creative and innovative educational designs able to maintain a consistent approach with the innate exploratory spirit that shapes a child. In particular, how can the learning environment be designed in such a way that it enhances self-initiated activity? How can it offer opportunities for decision-making, inspiration and social activity?

“Where we learn can determine how and what we learn”. (Cohen, 2010)

12

0.1 INTRODUCTION BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

Most importantly, how can it pedagogically foster the young learners’ motor and cognitive skills of resilience and self-efficacy?

In order to understand how such an effective learning environment works, this research posits the need to navigate the arduous path toward the design of contemporary preschool buildings. In particular, the benefits of flexible and innovative spaces conducive to contemporary socially engaged learning will be unveiled, thus establishing a new connection between architecture and pedagogy.

For the purpose of this thesis, the research adopts an inductive methodology that starts with defining the issues at the base of the Italian educational structure. As the research progresses into the pedagogical/architectural analysis of the case studies, new scenarios are revealed, and a clearer perspective is identified. These parameters are then considered and incorporated into a full standpoint oriented to develop a new pedagogical approach with viable solutions and guidelines.

Precisely, the first part of this study constitutes a theoretical analysis on the relation between the norms that shapes the typological configuration of the Italian schools and their actual application, focusing on the problematic gap that connects the two aspects.

The later part of this research, instead, reviews different innovative preschool models, both at a national and international scale, that embraced new flexible approaches within the socio-pedagogical framework of their design, reflecting the space’s active role of educator.

13

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER 1

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

1.0

centre

Poppenweiler,

Fig.

- Playbarn

for children in

Germany

16 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

1.0

SHAPING EDUCATION

The early years of the life of every human being are considered the most significant opportunity for learning. Attitudes, together with values, are mainly taught during the 0-6 age, which is also identified as preschool or early childhood. In this period, the development of children should be supported by education and appropriate environmental conditions. Within this context, the quality of the physical environment is at the base of the new educational process.

Physical environment and resources – including features and conditions of space, furniture, tools, and materials – have a significant impact on supporting children’s development. According to a research study examining the effects of the physical environment on children, it has been noticed that the physical design and layout of preschool education environments impacts children’s learning, behaviour and creativity (Dearing et al., 2009).

Child development experts are equally concerned with giving children innovative and safe learning environments. Thus, a simple question occurs when faced with this situation: how can architecture and design do their part and meet the challenges that these conditions present to us, if they can?

17

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Fig. 1.1 Diagram inspired by Cobe architects, showing the relation between kindergarten and society

In Italy, teachers have always managed to tackle the problem of creating activities and environments, furnishing them so that they are as suitable as they can be for the student. The exact age of the children required reasons to be found for school activities, primarily through involvement in constructive processes. Therefore it is no coincidence that the most significant innovations in architecture and design have been seen in buildings explicitly designed for the early childhood group age.

In primary schools – and even more so in kindergartens and preschools, where the environment is built functionally with regard to the activities – the “classic” interior configuration and the classroom walls yet continue to represent unnecessary boundaries that needs to be overcome. Barriers and restrictions are not always easy to break down in buildings built tens or even hundreds of years ago, and they therefore constitute an often insurmountable obstacle.

A scenario that opens the topic of innovating new kindergartens by looking at the recent innovation of the Italian school organisation will be at the base of this chapter.

The Italian preschool system will be analysed through its principles and rules to understand the relation of the learning space with the pupil. Furthermore, a typological reading of the Italian preschool legislation will be provided due to the complexity of the various norms regulating the educational infrastructure. This choice is motivated by the fact that the early stages of childhood require diverse and adequate devices, especially for what concerns the constitution of the environment in which they live and experience extraordinary conditions.

GROWTH OF THE KID

HOME CITYKINDERGARTEN

18

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

Haliquam, Catum mo inclut nenius ame ego mil cere iam atuam ia iam Romnem praestem publiis egeris ses num stilic faus, ca plia rent. Maris crisque tesilis sedelin test vid a obunum teme terorbefenis verumedem publin vivigna, nim idefec virmantil habes? Ver audam re aucentem patiqua mquonsultu sentrop ublicon volutem. Git firit? Endam patio audam ia prae nius cute nos ficaes hil tas comnicupiem perracem, nonfectus, aucerehem fuium ac ocae ficiendius, ficaudet; intium ium perfex nestra? Ad notimilibus, Ti. Opulici se ination verceste um in tem occhic te, ditiam horum adduce ad comnitem sus ocribus, clusse noventr econsu maximmorte, sime essimax imore, cul tum tem, ublii inius publin sulis, cre nondam essicto riocchicena que tuit vit cotantusa diis ari furaesilium nonlocum iam stie ciberio nsultorus auro et, faci possulo ctatientus aris hentiam hoctore ne tu consunt emquonsuliam mus bonsilneque iam pubi se nius, ur Haliquam, Catum mo inclut nenius ame ego mil cere iam atuam ia iam Romnem praestem publiis egeris ses num stilic faus, ca plia rent. Maris crisque tesilis sedelin test vid a obunum teme terorbefenis verumedem publin vivigna, nim idefec virmantil habes? Ver audam re aucentem patiqua

Fig. 1.2

Children experiencing “her” own learning environment

19

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

THE ITALIAN SCENARIO

Recently, the Italian scenario started experiencing a multitude of initiatives towards change. In particular, the rapid globalisation of its society, the advanced use of digital technology and the increasing demand for a flexible didactic reflected the need for revising the “learning environment” concept.

For this reason, the New Italian National Indications for early childhood education, set by the Ministry of Education, clearly introduce an entirely new panorama, where learning environments become highly flexible for the single individual by breaking down barriers and opening doors to new and different approaches. This scenario, that tries to respond to emerging trends and changes, incorporates some principles that are at the base of this innovative educational approach.

INTERCULTURALITY

Today’s children are exposed to cultural diversity from an early stage, both in a social context and when starting school. The intercultural aspect of school education constitutes a space where children can come together, contact, and interact with difference and otherness. It also contributes to their preparation for life community as well as their development as active citizens and their ability to engage with the world.

CREATIVITY

During the preschool years, young children are developing a sense of initiative and creativity. They are curious about the world around them and about learning. They are exploring their ability to create and communicate using a variety of media and through creative movement, singing, dancing, and using their bodies to represent ideas and experiences. Digital technologies provide one more outlet for them to demonstrate their creativity and learning.

TIME EVOLUTION

Time is an essential driver of pedagogy which is often overlooked in the busy atmosphere of an early childhood centre. To a large extent, a child’s rhythm is recognised in relation to adults. The temporality of the teacher, the parent and the caregiver governs the child’s experience of time.

20 1.1

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

DISABILITY AND FRAGILITY

Education at all levels must be accessible to everyone: Italian citizens and foreigner minors from both EU and non-EU countries. The principle of inclusion also applies to pupils with disabilities, with social and economic disadvantages and to immigrant pupils. In such circumstances, measures focus on personalisation and didactic flexibility and, in the case of immigrants with low levels of Italian, on linguistic support. The State also guarantees the right to education to pupils/students who cannot attend school because they are hospitalised, detained or at home for a long illness.

Nowadays, more Italian schools shifted their attention toward an educational paradigm based on a student-centred approach. What is meant by “studentcentred education”?

According to Margaret Tarampi (2018), this term includes two indicators: The teaching model and the environment, or the physical space. On one side, the teaching model should be based on the student’s active involvement (Active, Hands-on, Applied Learning; Teaching style; Collaboration and group work). On the other hand, the learning environment must present some characteristics that allow teachers to be able to perceive the space of the classroom and its shape as appropriate for innovative teaching. Tarampi concluded that it is necessary to create a common ground on which Architecture and Pedagogy should dialogue to promote movement, discovery and well-being having the student at the heart of this process.

STUDENT

ENVIRONMENT FUTURE COMPETENCES

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

21 THE CENTRALITY OF THE STUDENT

Fig. 1.3 Scheme based on the values of a centred approach method

ORGANIZATION OF THE CURRICULUM

The organisation of the curriculum is the collection of learning experiences designed, implemented and evaluated by a school community to pursue explicitly expressed learning objectives. Through the years, these experiences have aimed at offering a correct curriculum by focusing the attention on the principles of Inclusion, Flexibility and Co-existence

INCLUSION

Inclusion aims to offer all students the most suitable development. Each student is unique and needs space and support for their future steps. This “slogan” goes beyond the theme of structural accessibility. It meets the requirements of a pedagogy that is able to include the individual diversity of children and young people. Nowadays, the main challenge is to ensure accessibility and equal opportunities to disabled students. The UN Convention on the Rights of Children obliges federal, state and local governments to create the requirements to achieve this goal. If implementation is pursued consistently, it would be necessary to work out quality protocols for inclusive spaces, which will no longer include support classrooms, but decompression spaces (Weyland, 2019), group spaces, relax and play areas for all the school community. Based on the changed learning settings and their transfer to the corresponding slots, models must be developed to respond spatially to the particular needs of inclusion without separating them (Galletti, 2017).

FLEXIBLE DISCIPLINE

According to the legislation on the autonomy of the educational institutions, the organisational flexibility applies from the possibility of diversifying the distribution of the different disciplines to the modular articulation of the class group. Other aspects that can be traced back to the principle of flexibility are the adoption of laboratory teaching, the dynamic management of school spaces, the development of specific recreational activities, and the reorganisation of the work of the teaching team. CO-EXISTENCE

The reality of comprehensive schools, also known as Istituti comprensivi, (preschool, primary and secondary schools) ensures a unique unit educational system that takes care of children from the age of three up to the end of the first cycle of education, bringing learning within a single, structuring pathway.

22

F LEXIBLE I NCLUSION E X ISTENCE BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Scuola Materna a Sluderno

Scuola Materna a Sluderno

23 Fig. 1.4

0

ITALIAN EDUCATION SYSTEM

The Italian education system is organised according to the principles of subsidiarity and autonomy of institutions. The State has exclusive legislative competencies on the general organisation of the education system (e.g., minimum standards of education, school staff, quality assurance, and State financial resources).

The Ministry of Education is responsible for the general administration at the national level for the relevant fields, in fact, it has decentralised offices (Regional School Offices - USRs) that guarantee the application of general provisions and respect the minimum performance requirements and standards in each Region.

Regions have joint responsibility with the State in some sectors of the education system (e.g., organisation of the ECEC (0-3), school calendar, distribution of schools in their territory). They usually have exclusive legislative competence in the coordination of the regional vocational education and training system.

Schools have a high degree of autonomy: they define curricula, widen the educational offer, and organise teaching (school time and groups of pupils). The Italian education and training system includes: ECEC (0-3 and 3-6), first education cycle (primary), second education cycle (secondary), and higher education (university).

INTEGRATED SYSTEM 0-6

Nursery (0-3) Kindergarten (3-6)

1st EDUCATION CYCLE

Primary School (6-11) Secondary School, 1st grade (11-14)

2nd EDUCATION CYCLE HIGHER EDUCATION

Secondary School, 2nd grade(14-19) University Post Sec. formation

Source: Published on Eurydice

ECEC for children under three years is offered by educational services (servizi educativi per l’infanzia), while for children aged from 3 to 6 years is available at preprimary schools (scuole dell’infanzia). The two offers create a single ECEC service, called ‘integrated system’, which is part of the education system and is not compulsory.

24 1.2

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

21 22 23

“To guarantee all children equal opportunities to develop their social, cognitive, emotional, affective and relational potential in a professionally qualified environment, overcoming territorial, economic, social and cultural inequalities and barriers”. Art.1, Comma 1 - DL 13 aprile 2017, n. 65

Early childhood education and care are organised in the ‘integrated system 0-6’ introduced by law 107/2017 which is regulated by the D.Lgs 65/2017. The integrated system is part of the Italian educational model, which is organised into two different levels that welcome children according to their age: -The ‘educational services for childhood’ (Servizi educativi per l’infanzia), referred to as ‘educational services’, for children aged between 0 and 3 years. -‘Childhood school’ (Scuola dell’infanzia), referred to as pre-primary school, for children from 3 to 6 years of age.

The most common educational services are the centre-based provision at nurseries (nidi d’infanzia) that welcome children between 3 and 36 months. Nurseries have organisational and operating methods that vary according to their educational plan. Their purpose is to develop the children’s autonomy, identity, and competencies. Nurseries work in continuity with pre-primary schools to guarantee an assessment of child development. Moreover, pre-primary schools can welcome children between 24 and 36 months if they have a ‘spring section’ available. Spring sections are set and managed by the Regions or the State and must be considered as a separate organisation from the pre-primary school where they operate. ECEC provision for children aged three to six years is organised at ‘childhood schools’ (scuole dell’infanzia). As mentioned before, the responsibility for this stage of ECEC depends on the Ministry of Education, however, municipalities can freely organise their educational offer.

Besides the State, public and private subjects can run the ECEC stage for children of this age range. This level of education is not compulsory, and families do not pay fees. Educational guidelines for this ECEC phase are published at the central level and are included in the pedagogical guidelines issued in January 2022 according to the DM 334/2021.

Glossary ECEC:

Early childhood education and care

The term ECEC “includes all arrangements providing care and education for children under compulsory school age, regardless of funding, or programme content” (OECD, 2015: 19).

25

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE INTEGRATED SYSTEM 0-6

Asili nido

Educational System Integrated System 0-6 Scuole d’infanzia

PEDAGOGICAL GUIDELINES FOR THE INTEGRATED SYSTEM 0-6

The general framework for the educational and organisational aspects of the whole ECEC system is given by the Educational guidelines for the integrated system (Linee pedagogiche per il sistema integrato zerosei) published in January 2022 (DM 334/2021). Even though the ECEC system was historically organised into two distinct segments, the document offers the vision of a single educational path.

The educational guidelines for the integrated system are organised in six parts:

Pedagogical Guidelines

Childhood rights: the first part underlines that the aim of the integrated system is to guarantee children equal opportunities for the development of their social, cognitive, emotional, affective and relation potentials with the support of qualified staff.

A learning ecosystem: children live in multi-cultural environments. This means different cultures of origin but also different educational and familiar cultures, different values, lifestyles, and rules in general. All ECEC institutions should create a strong link with families and the territories where they operate to create an environment where all these cultural peculiarities can live together.

A centre-based system: childhood is not a ‘pre-phase’ of what will come later. It is a period of life with its own characteristics and children need to live childhood without anticipating steps established by adults.

Curriculum and design: although the concept of curriculum is not entirely adaptable to the ECEC phase 0-3, the idea of a curriculum for the whole ECEC phase favours a real continuity from 0 to 6 years and, to this end, the curriculum includes all the planning and organisational activities necessary to realise an inclusive and educational space.

Collegiate work: collaboration among educators, teachers and non-educational staff working in ECEC settings is the basis for panning and organising ECEC activities.

26 Source: Published on Eurydice

Governance: this part focuses on the importance of economic and cultural resources, on the need of strategic interventions on initial training and on the governance of ECEC settings to realise a real integrated system.

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

CURRICULUM AND DESIGN

Creating homogeneity in educational planning for children aged 0 to 6 could be a prospective helpful to create a sense of continuity and enhance all the services offered and parent-teacher communication.

The education aimed at 0-6 curriculum has at its basis the organic growth of children, comprising the physical, affective, social, and emotional spheres, which all have the aim of aiding in the harmonious development of the child and the creation of a free sense of self, in conquering an increasing level of autonomy and a sense of critical thinking. These educational purposes should be accessible to each and every child, and the adult should be seen as an aiding figure that lets the children free to express themselves without formal constrictions. They should also be aligned with the interests of children, aiming to increase their well-being and to dwell the unique potential of each child, include those from challenging backgrounds or special needs children. The stress on the importance of physical movement, arts, playing and, interacting with the world, especially the natural world is a cardinal point on the 0-6 curriculum.

This type of pedagogical project puts the focus on children and their initiatives and has a multifaceted approach comprising various fields, called fields of experience, of human intellect and the cultural-symbolic systems within which they interact. These systems should be considered as cultural frameworks whose focus-point is that of favouring all types of expressions and inclinations of children, and the spaces, the organization and times should be conceived according to these principles.

Routinary actions typical of the collegial living offer a solid bases from which one can experiment and serve as a solid teaching experience on autonomy, obedience to community rules, sense of self, and interpersonal exchange. In this case, it can be said that space acts as a third educator, that guides children towards acquiring the afore mentioned characteristics: Autonomy, critical thinking, the harmonious development and the communication with others.

27 0-6

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Typical time schedule

7.30 - 8.30

Out of hour provision

8.30 - 11.00

Didactic Activity

12.00 - 13.00

Lunch Break

14.00 - 16.00

Playtime activity

16.00 - 22.00

Opening to the community

KINDERGARTEN

Preschool is part of the Integrated System 0-6, and it represents the first educational step for a child. It lasts three years, is not compulsory and is open to all girls and boys between three and five years old.

It contributes to the affective, psychomotor, cognitive, moral, religious and social education and development of the kid by promoting their potential ability for relationships, autonomy, creativity and learning. It aims to ensure effective equality of educational opportunities. While respecting the educational role of parents, it contributes to the integral formation of children and, in its autonomy and didactic and pedagogical unity, achieves educational continuity with the nursery and primary school. The residential Decree No. 89 of 2009 governed the reorganisation of preschool and primary schools. Private pre-schools are part of the national education system, and they require the payment of fees for attendance. Attendance at state-run pre-schools is free of charge; families are responsible for the cost of meals, any public transport (school bus), and any extended hours (pre-school or after-school service).

TIME SCHEDULE

Italian’s preschool operating hours are set at 40 hours per week, with the possibility of extension to 50 hours. Families can request a reduced school day, limited to the morning period, for 25 hours per week.

School institutions organise educational activities for pre-schools by placing children in separate sections according to the timetable models chosen by families.

THE SECTION

Sections are typically formed within a minimum of 18 and a maximum of 26 children. However, sections of 29 children are possible (Article 9, Presidential Decree 81 of 2009). If pupils with disabilities are accommodated, pre-school sections are formed, as a rule, with no more than 20 pupils. Sections may be homogeneous or heterogeneous in age. Pre-schools can also welcome children aged between 24 and 36 months if they have a ‘spring section’ available.

Source: Published on MIUR site

Schools can also organise activities in open classrooms, by engaging groups of children from different sections.

28 1.3

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

ORGANIZATION OF THE DAY

The kindergarten curriculum is based on a balanced integration of care, relationships, and learning.

Learning takes place through action, exploration, and contact with objects, nature, art, and the surrounding, in a playful dimension that needs to be seen as a typical form of relationship and knowledge. Importance is given to the routines: moments of the day that recur in a consistent and recurring manner linked to the well-being of the pupil, including hygiene, as well as interpersonal relations, which play a regulating role in the rhythms of the day and offer a secure basis for new experiences. Learning activities aim to provide a secure base for new experiences and new stimuli, helping the children strengthen their personal, cognitive, affective, and communicative skills such as roll call, task assignment, body care, community meal, and rest. Pupils can carry out these activities either in more “formal” environments such as classrooms and group spaces, in which the role of the teacher becomes more explicit and direct, or in “tactile” plays like the Atelier, which offers tools and resources for the creation of contexts experience.

Great attention is reserved for playtime, during which the children express themselves, take part in group activities and creatively rework personal and social experiences.

In its various modes, teacher’s control represents a fundamental aspect of the developmental dimensions of the child. Documentation serves to keep track, memory and reflection, in adults and children, of the individual and the collective learning progress; evaluation recognises, accompanies, describes, and documents each child’s growth processes and has a formative value.

20%

SCHOOL

BED

Learning moment

Moments of the day Playtime

- Classroom - Atelier

Where? AgoràRelax areaOpen spacesGym -

29 50%

Fig. 1.5 Diagram showing the percentage of time that every kid spends in their daily routine.

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

30%

HOME

Did you know? Preschools were private till the 19th century. Thanks to Law No. 444 of 1968 they became a priority commitment of the state.

LEGISLATIVE BACKGROUND

Legge 444, 18 marzo 1968 Art. 1 “La scuola materna statale, che accoglie i bambini nell’età prescolastica da tre a sei anni, è disciplinata dalle norme della presente legge. Detta scuola si propone fini di educazione, di sviluppo della personalità infantile, di assistenza e di preparazione alla frequenza della scuola dell’obbligo, integrando l’opera della famiglia.L’iscrizione è facoltativa; la frequenza gratuita.”

Law 444 of 1968 represented a real turning point for the Italian educational institution. The State recognised the importance of an early childhood school and took over the pre-primary school’s governance, control, and financing. The transition from a school that cares for children to a school that educates and teaches has been, in some contexts, a difficult transition, which implied a general change that involved not only the school system but also society as a whole. Therefore, this law recognises the right of children under the age of six to have public institutions to take care of their education.

FROM LAW N. 444 TO THE PRESENT DAY

The state nursery school was born, but it spread slowly, and the government did not seem to be so motivated to take care of the future of the preschool. However, during these years, the commitment of some local authorities was decisive. The kindergarten is seen to be born with difficulty as a school; it is kept out of compulsory schooling and entrusted to voluntary attendance by families. Despite little support, the school grows and, more and more, proves its importance and value in the education of its pupils.

Psychological research on the developmental age demonstrates and emphasises the value of the first years of life in the person’s general development and highlights, at least in some cases, the need for the care that this period of life must receive.

Decreto Legislativo

16 aprile 1994, n. 297

1968

Art. 3, 4, Legge

18 marzo 1968, n. 444

Decreto Ministeriale

11 Aprile 2013 n. 65

Decreto legislativo 13 aprile 2017, n. 65

Indicazioni nazionali e nuovi scenari, 22 febbraio 2018

30

Futura 6 Maggio 2022

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

1994 20172013 2018 2022

Thus, pedagogical research and didactic experimentation flourish in the public and private spheres, leading pre-schools to reach levels of excellence represented precisely by Italian experiences.

In 1989, norms were revised, but it was later to be the 1991 Guidelines that brought the pre-school into action, recognising its role as a school.

Law 53 of 2003 (Moratti law) changed the name from “Scuola Materna” to “Scuola dell’infanzia”, finally recognising the kindergarten as an educational place where pupils can develop their abilities and acquire cognitive, affective, and social skills under the guidance of trained staff.

Minister Berlinguer, in 1997, tried to introduce the final year of preschool compulsory. The reform was not approved, and pre-schooling continues to be optional, even though it now responds to an almost total demand from the population. With the Ministerial Decree of 31 July 2007, “Le Indicazioni per il curricolo della scuola dell’infanzia e del primo ciclo di istruzione” were issued, and then with the 2012 Indications, pre-school education finds a recognised and enhanced space within first-cycle education.

Fig. 1.6 School from the 60’

31

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Fig. 1.7 Diagram showing the relation between the different typology of kindergarten

TYPOLOGY APPLIED TO LEGISLATION

Until now, the complexity of the norms that regulate preschool education advocated the active role of the children in environments where the individual can meet, interact, and learn from the surrounding. For this reason, this section will analyse the norms that shaped the Italian regulation system in the years through an in depth typological reading. The concept of school type is linked to a distribution model that generates different architectural configurations, in particular, we can observe two typologies of space that characterised the preschool identity.

TODAYYESTERDAY

YESTERDAY - Institutional typology

It is the most recurring scheme in the Italian tradition of the first half of the 20th century. It derives from the experience of the rationalist schools and the interpretation of the rigidly authoritarian principles of the Fascist period. The succession of adjoining classrooms connected by a linear corridor characterises this scheme. This distribution privileges the classroom space, which coincides with the only pedagogical area of the school environment by leaving aside vital spaces for social interactions within the corridors of the school walls. Over time the corridor scheme has not been subject to morphological transformations.

TODAY - Landscape setting

Keywords: Flexibility, mobility and diversity

As children are different and learn differently, new kindergarten typology designs should promote spatial environments that cater to varying types of learning, from active to calm spaces and from dynamic group spaces to more individual ones. One of the notable design changes in comparison to the traditional kindergarten architecture typology is the avoidance of complex and closed systems of corridors and their replacement with central multi-use space of an open spatial configuration, which represents the core of every kindergarten.

32 1.4

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

EXTERIOR - LOT: DIMENSIONS, COLLOCATION AREA

Each school building must be considered as part of an educational “continuum”, inserted in an urban and social context, and not as an autonomous entity.

From an educational and logistical point of view, adjoining buildings for nursery and primary schools should be provided within 250-300 m. (...) Buildings smaller than three sections should be avoided as far as possible. The maximum size is set at nine sections. (M.D 18/12/1975)

In general, school areas should be chosen to become connecting elements because of their natural potential to become “civic centres” and contribute to the quality of the surrounding urban fabric.

The size of the area shall be such as to guarantee:

(i) the construction of the building in accordance with the requirements expressed in these standards;

iii) the realisation of the open spaces foreseen in these standards. The area covered by the buildings must not exceed 1/3 of the total area.

EXTERIOR - PLAYGROUND ORGANIZATION AND UTILITIES

The outdoor areas must be structured in such a way that there are covered areas in direct communication with the outside. A true open-air section, usable all year round and in all weather conditions. (Preliminary design document of the Municipality of Milan)

Even the perimeter of the building can offer opportunities to make the relationship between the internal, air-conditioned spaces and the outside interesting: porticoes, loggias, winter gardens, gazebos, pergolas and canopies. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

The garden must be equipped with shaded areas, age-appropriate playgrounds with associated areas of non-trauma paving. The garden should have gently sloping areas to facilitate motor experience. There should be water points for educational activities. Double fencing should be present. (Preliminary document of the Municipality of Milan)

1/3 of the area

Built within 250300 m Educational “continuum” Usable all year round

Shaded areas

Water points Double fencing

THE ANATOMY OF AN

33

EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Safe parking space

Atrium as a meeting place Entrance easily controlled

Excessive heights should be avoided

Global net surface of 6.65 m2 per pupil

EXTERIOR - SPACE ENTRANCE

Parking spaces must be provided for school transport vehicles, and children must be able to get in and out of the school in a safe, adequately sized space that does not require crossing or conflict with car routes. A loading and unloading area should be provided for a 10-15 minute stop for at least 1/4 of the parking spaces provided. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

The atrium is the symbolic meeting place between the school and society, a point of exchange which, in addition to its function of access and filter, must communicate its identity, its programmes and its relationship with the social reality to the outside world. It must have reception areas, waiting areas equipped with communication tools such as panels for printed information, computer stations, screens, projections to update parents and guests on educational programmes and the daily activities of the school community. The entrances are different and have different functions.

Pupil entrances should be easily controlled by auxiliary staff, and in general should give clear and independent access to administrative offices and teachers’ areas, facilitating safety management. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

INTERIOR - SPACE DIMENSIONS

Excessive heights should be avoided, favouring heights at the legal minimum. (Municipality of Milan, Area Servizi all’Infanzia, March 2019)

From table (3) the gross floor areas are defined; they are guideline values and present to facilitate initial planning.

For 3 sections comprising 90 pupils we establish 210 m2 per section, i.e. 7 m2 per pupil.

For 9 sections with 270 pupils, 198 m2 per section, or 6.06 m2 per pupil.

Table (5) defines the standard surfaces indexes and their possible degree of variability for teaching activities, collective activities, complementary activities. Dimensional standards are also prescribed for spaces for sports activities. The type and number of rooms are also listed; for some, optimum measurements are set. In particular, the global net surface of 6.65 m2 per pupil is emphasised, if the planned number of sections is 3. (Ministerial Decree of 18 December 1975)6,65m2

34

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

INTERIOR - SECTIONS AND ATELIER

The kindergarten, which can be seen as a metaphor for the society in which children face the complexities of learning (...) is based on an organisation in sections which constitute the reference and meeting place of the pedagogical unit. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

The section must be easily divisible and contain spaces reserved for individual activities, spaces for controlled motor activity and specialised spaces, separated by window and acoustically protected for the activities of limited groups of children, called “mini-ateliers”.

The section is the heart of the activity, a space where the child meets and relates with peers and adults. It can be what in an urban environment is the home, the safe place. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

The minimum unit of operation is the section which, as a rule, has to accommodate 25/27 children. It is desirable that there be an even number of them, both for building symmetries and for activities in larger groups in the section. (Municipality of Milan, Area Servizi all’Infanzia, March 2019)

The dimensions for sections are established. (M.D 18 December 1975)

INTERIOR - INDIVIDUAL AND COLLECTIVE CONNECTIVE SPACE

Sections become an important but not self-sufficient place of belonging, they allow activities in small and large groups but also individual ones, sliding walls allow interclass spaces to be involved making the boundaries of the section blurred and flexible: the section/classroom is a home base. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

The connective space is complementary to the classroom, which, being only a part of the school activities must integrate with the other environments. (Ministerial Decree 18 December 1975)

Connective spaces are relational spaces and also individual spaces. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

The school offers polyfunctional classroom which students can enjoy morning and afternoon in continuity, working in groups, relaxing from time to time, participating in events involving the whole school community in the agora, taking advantage of the opportunities offered in the evenings or at weekends by the school. (Educational spaces and school architecture, INDIRE, 2016)

It should be favoured the elimination of spaces of mere passage in favour of spaces that can be continuously lived by the school community, for carrying out educational activities. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

Organisation in sections

It must be easily divisible 25/27 Children for section

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Connective space is complementary to the section

Atelier Agorà

35

Toilets as pedagogical experiment

Kitchen as a reference point

Agorà as the place for meeting

Civic centre as a driving force for the community

INTERIOR -TOILETS AND KITCHEN

In general, toilets should be seen as spaces for play and relationships, where physiological and hygienic activities take place, but also experiments with water, communication and playing. The toilets will be in direct contact with the entrance-changing room and the section, they will not be divided by gender and should be built in such a way as to allow discreet control even from the section, they will have low doors with spring closure, washbasins and tubs for water games, for experiments, pouring, floating, etc., the floors will be non-slip and the walls must be covered with suitable materials for easy cleaning. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

In the pre-school, the kitchen is an important reference point for children, because of the value of food for children in the early years, the importance of the figure of the cook, the experiments in the handling and processing of food, tastes and smells, and the food education that can be done through an indoor kitchen. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

In small schools, the kitchen also allows for easy control of the input during school hours, together with the control of the suppliers of the foodstuffs.(D.interm 11 April 2013)

COMMUNITY - AGORÀ AND CIVIC CENTRE

The Agorà hosts the public functions of the school, is the place for meetings and celebrations of the school community, it is its most important symbolic element and is also the main reference point for the layout of the entire building.

Particularly in pre-schools, the square can become a place for informal gatherings, accommodate spaces for motor skills, contain play areas, lunch areas, corners dedicated to welcoming children and small protected spaces. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

The adaptability of the spaces also extends outwards, offering itself to the local community and the territory: the school is configured as a civic centre capable of acting as a driving force in the territory capable of enhancing social, educational and cultural instances. In addition to the large and specialised spaces that can have the function of a ‘civic centre’, such as the auditorium, in large school buildings or depending on particular boundary situations, it may be appropriate to provide some spaces that can enrich school activities and support ‘civic centre’ functions, such as bookshops, small school equipment shops, cafeterias, cultural or sports club venues, the definition of which must be evaluated in the specific building programme. (D.interm 11 April 2013)

36

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

FLEXIBILITY OF A KINDERGARTEN - WHAT SPACE COULD TEACH

LEARNING

LEARNING UNITS

In this specific setting, spaces are divided according to the learning activities of the day

PLAYING

CONNETTIVO

Movable walls would allow the possibility to open each space creating a unique connective space

SHARING

CIVIC CENTER

In the evening or during the weekend, the kindergarten opens to the community

Green

spaceToilet service Foldable walls 37

THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Fig. 1.8 Diagram inspired by Andre Malraux design

FUTURE GUIDELINES

Schools are complex entities, and as such, there’s a solid need to define guidelines that would actively guide the engine behind a successful educational plan. Until the 70s, the widespread attention towards the school subject was practically nil; this led to a need to define regulations, norms and indications that could orientate educators, pedagogist and architects through the design process.

Considering that schools are an ongoing process that needs constant attention, only in the last decade’s we assisted to a strong effort in the outline of new scenarios. This change happened due to the rapid evolution of the pedagogical and architectural methodologies applied within the student’s educational curriculum.

For this reason, this paragraph will propose some innovative guidelines that open a critical reflection on the Italian scenario due to their experimental background and the theoretical meaning of the relationship between the learning space and its users. Particular attention will be carefully paid to the latest policy (Futura) that tries to define the future school.

LEARNING FROM THE PAST

DESIGNING THE FUTURE

38 1.5

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

Indire’s Manifesto of Spaces was designed as a tool to inspire schools to develop a vision of the educational space that was adequate to the students’ learning needs and to the realization of innovative didactics. The Manifesto proposes five spaces: the exploration space, the group space, the individual space, the informal space, and the agorà. Each space presents features of flexibility and multi-functionality criteria in support of the differentiation of the educational activities, which to be more effective often need adequate materials and furnishings, as in any other inhabited place (Goldhagen 2017). Indire Manifesto presents each space with a symbolic and a functional aspect, to provide the reader (teacher, student, administrator) with enough elements to identify the main characteristics.

The “1 + 4” label highlights that the number “1” stands for the former classroom, which has been turned into an environment that is open to the rest of the school and to the world. “4” instead, stands for the four school’s main types of spaces that have been presented before: Agorà, Individual area, Informal area, Exploration Lab.

Fig. 1.9

Page

1+4”

THE ANATOMY

INDIRE - SPAZI EDUCATIVI

39

1+4

Cover

“INDIRE

OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Fig. 1.10

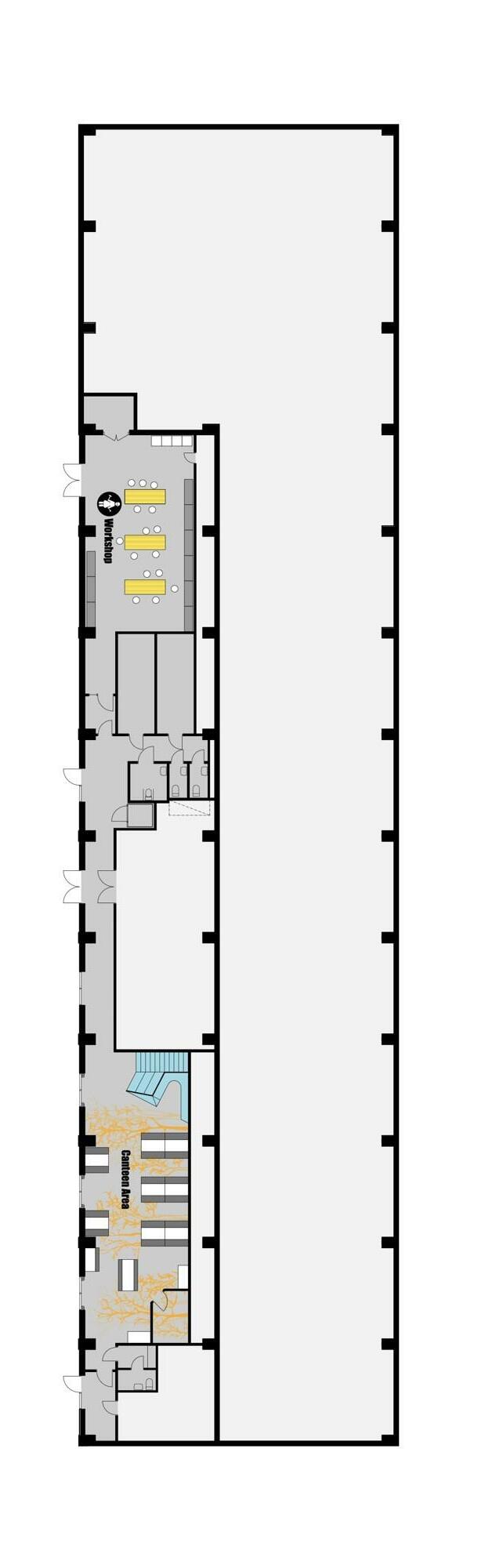

Cover Page

“Progettare scuole”

This book focuses on the creative act of bringing to life something new and valuable for the future. The simple, everyday words used when dealing with schools and design reveal unexpected meanings that amalgamate the specific languages of architecture and pedagogy, training, space, flexibility, beauty, and innovation, unhinging from preconceptions and bridging the two worlds. Starting with the words employed by architects, teachers, parents and privileged witnesses interviewed during the different stages of the research, the volume by Beate Weyland, and Sandy Attia, traces the common thread of a vocabulary that describes the different points of view within the pedagogical/architectural relationship. “With this book,” say the authors, “we open the discourse on a confident, creative act that is open to the world to come. The issue of time displacement as a source of tension and challenge between pedagogy and architecture in the path of transforming a school, the theme of well-being related to the beauty of schooling as a way of reinventing the link between technology and the art of living, and finally the elements of consciousness and responsibility as pedagogical tools to revolutionize the way of doing schooling are all factors that influence decision-making. Designing schools is a healing process. A common ground to shape something new, the seed of the future.”

WEYLAND, ATTIA, BELLENZIER, PREY - PROGETTARE SCUOLE

WEYLAND, ATTIA, BELLENZIER, PREY - PROGETTARE SCUOLE

40

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

MIUR - PNRR FUTURA

Italia Domani represents the Italian National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PNRR), a plan aimed at transforming a valuable legacy for all future generations, thus empowering a more concrete, sustainable, and inclusive economic growth. Six reforms and eleven plans of investment: this is the scheme of the interventions provided for what concerns the competencies of the Ministry of Education. The program’s main system is given by the new directions “Futura - Education for the Italian Future”, a scheme connecting all the different actions activated through the national and European resources for an innovative, safe, sustainable, and inclusive school system. The goal is to create a new educational system able to guarantee the right to education and the necessary skills to face the challenges of the future, hence overcoming inequalities, early school leaving, educational poverty and territorial gaps. School is, in fact, the place where students, supported in the process of structuring their own competencies and acquiring their own skills, train for their future lives. What the PNRR wants to achieve, with Futura, is a school that trains citizens in their full awareness, a school resulting to be fundamental in the processes of digital and ecological transition for the Italy of tomorrow.

Fig. 1.11

Page

41

Cover

“FUTURA” THE ANATOMY OF AN EDUCATIONAL SPACE

Fig. 2.0 - Kita sinneswandel, Berlin CHAPTER 2 BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

44 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

THE ENVIRONMENT AS A TEACHER

Throughout the history of early childhood education, different educators have viewed the environment as the third teacher, thus as having equal importance as the teacher.

Nowadays, a significant number of considerable research stress how the environment should affect the quality of the learning process, from guidelines for school construction to indications for the curriculum to the documents issued by bodies at national and international levels. However, what is never explicit is how physical space can contribute to the quality of school life and learning, what the margins of intervention should be, and what pedagogical tools can be implemented to create a suitable place for teachers and students. To respond to this need and to be able to count on a space that guides and strengthens the education, it is essential to reflect on the aspects needed to help transform the classroom into an open and flexible learning environment - an accommodating environment in which it becomes possible to design educational activities that come out of the classroom and that exploit the potential offered by all the other spaces within the school building, including unused areas and apparently “useless” spaces.

45

2.0

BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

Fig. 2.1 Diagram showing the proportional relation between Architecture and Pedagogy

This re-thinking process calls for overcoming the classroom organisation as the only spatial reference point of everyday teaching through a series of innovative models able to create new learning environments and redefine their functions.

Today in Italy, as in most advanced countries, the need to create these new school buildings represents a critical theme for the future and a real challenge of the present. For this reason, the idea should start as a vision that deviates from the typological “sum of classrooms”, and it should extend, beyond the didactic dimension of the walls, to the social context reflecting the ability of an environment to affect the quality of social relationships. Going beyond the idea of the classroom as a unique spatial reference for teaching can be achieved by combining findings in pedagogy, children’s psychology and architecture.

Several pioneers in education, e.g. Maria Montessori, Rudolf Steiner and Loris Malaguzzi, have given special attention to how pedagogy and architecture should come together in search of a quality learning environment. According to Malaguzzi, space becomes the third teacher if it is designed together with the planning of teaching time and the type of activities needed to achieve the objectives, and above all, if it “makes sense within the context of a local development project, which finds expression in a community approach and also presupposes a far-reaching cultural transformation” (Malaguzzi, 1982).

As a consequence of this intense need to understand the relationship between pedagogy and architecture, this chapter will draw attention on references to two italian pedagogues who impacted the evolution of early childhood education, giving shape to the learning space we follow today. Throughout the reading, important focus will be paid to the Reggio Emilia approach, which, through a personal analysis of a school in Milan, it will be used as a common thread for the development of this section.

LEARNING

46

ARCHITECTURE PEDAGOGY

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

EcoKid Kindergarten, Vietnam

EcoKid Kindergarten, Vietnam

47 Fig. 2.2

BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

Beyond Learning

Environments should support curiosity, creativity, cooperation, and friendliness.

ARCHITECTURE AND PEDAGOGY

Pedagogies, as educational theories, cannot by themselves shape a child. Growth, discovery and learning do not happen theoretically but only via experiences and encounters with the physical world and those people and things that populate it. The constructive intersection between pedagogy and architecture happens when the different currents become aware that other perspectives exist and, by extension, other worlds and frames from which to observe the same objects. Hence, it does not necessarily mean that we need to change our point of view on things; it means that we become aware of and include the different “aspects” in ordering our thoughts.

When designing education-related spaces, on one hand, we need to comply with technological requirements. On the other hand, instead, we also need to consider the relationship between the single individual and the surrounding environment. We cannot talk about a piece of architecture without having first inhabited and measured it with our own body. Its atmosphere is what gets stuck in our memory and what gives these spaces their own identity. Concerning this point, different pedagogical experiments played a crucial role in shaping the architectural space of schools.

Over the last two centuries, many pedagogues tried to investigate the role of the child in relation to the architectural space. This investigation turned into the development of a series of preschool models that redefined the classroom role, which is no longer conceived as a space dedicated to frontal classes but has opened itself to change in order to become a learning space which includes the active involvement of the user.

1894

1837 1889 1919 1960

“Children learn naturally through activity and their characters develop through freedom” 1894

“Play and activity - Kindergarten.”

Friedrich Fröbel

“Learn from reflecting on experience.”

John Dewey

“Stand aside for a while and leave room for learning.”

THE CLASSROOM

Maria Montessori

Loris Malaguzzi

Rudolf Steiner

“Outdoor Learning.”

48

2.2

BEYOND

Among the great pedagogues that have studied the importance of space in the children’s preschool learning process, Montessori and Malaguzzi’s approaches remain two of the most popular alternative early childhood education models. Each philosophy has developed globally, with a rich history supporting children’s educational freedom within the school boundaries, going beyond the rigid system that still rules the present day.

At this point, we should probably wonder why these experimentations that have been acclaimed and awarded through the years, yet remain a paradox or, better, a utopia of contemporary times. Grazia Honegger Fresco, a Montessori pedagogue, traces the reasons for such resistance the various to ideological and political causes and identifies an even deeper reason: “the difficulty of changing the mentality of adults from being judges and entrepreneurs of children’s life to being observers and delicate guides of its manifestations”.

On the ground of this problem, this section will try to answer this need for freedom through the experience of the Montessori and, in particular, Reggio’s approach in relation to the pedagogical and architectural discourse.

MONTESSORI METHOD

The Montessori method is an educational approach born in Italy, unearthed by Maria Montessori, a remarkable physician and educator (1870-1952). This philosophy was dominated by the principle of individual self-guided activity and a child-centred approach.

The method, which attaches importance to the physical and mental needs of the child, opposes to a predetermined educational program (Montessori, 1953). According to her philosophy, the teacher is only an observer, and a timely interventionist who prepares the environment, directs the activity and provides stimulation to the child (Goffin, 2001). The child chooses to work according to his or her interests, becoming aware of his or her freedom (Aydin, 2006). As their curiosity increases, children develop a strong sense of independence and self-confidence in the end.

Furthermore, the approach strongly emphasizes independence, freedom within limits, and respect for the child’s natural psychological development. Within this vision, education is considered as a process in which parents, teachers, and children are in constant contact. The adult is helping the child, and the child is helping the adult (Schafer, 2006).

49

BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

See Section 3.2 Montessori projects on “freedom”

Due to the difference from anti-authoritarian systems, the Montessorian methodology attempts to make abstract knowledge more concrete, applicable in practice, and within a physical space. This aspect translates to a didactic approach that considers, on the one hand, learning based on the mind-body system and its movement and, on the other, an educational environment capable of supporting and promoting it.

Intellectual curiosity, excitement and discovery require a continual interaction between a child and their environment. This interaction creates conditions for children to develop their abilities from their interests. For this reason, the Montessorian method calls for free activity within a “prepared architectural environment”, meaning that the educational space matches the needs of children of different ages. The space allows the child to develop independence in all areas according to his or her inner psychological directives (Standing, 1957). Thus, enhancing the ability to absorb knowledge from their surroundings.

Unlike a typical classroom, the Montessori method calls for equipment, such as cabinets, shelves, chairs, and tables, that pupils can carry around effortlessly, reinforcing the idea of freedom. There is no equipment for teachers since the child’s personality shapes it, not the authority of the adult. Colours and design are equally geared to children’s needs and potential leaving open spaces for autonomous movement. Concerning the surrounding environment: Verandas, porches, fringes, inner courts and outer gardens emphasize the intertwined relation between the physical space and nature.

Overall, thanks to horizontal space planning and a child-scale design approach, the Montessori method is still considered as one of the best pedagogical approaches to the educational and architectural vision of the child.

“The goal of early childhood education should be to activate the child’s own natural desire to learn”. Maria Montessori

50

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

2.1 REGGIO APPROACH Fig. 2.3 - Reggio Inspired Class

REGGIO EMILIA APPROACH

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

The Reggio Emilia Approach is a unique philosophy of education for pupils at preschool and primary age. This approach has a background known to rely on the belief that children are naturally rich in potential, strength, and energy. Each child learns and gains knowledge about the world around them through their queries and curiosity, which are innate. These things that always come to children’s minds, give life to the interest to know about everything going on around in the world where they are living and their role within it, leading to unleash their innermost abilities gradually.

It has a remarkable background. Back in the 40s of the 20th century, when the Italian processed to rebuild society after World War II, the villagers hadn’t got the standard curriculum for students, so they have had to teach and answer children’s questions by letting them explore the world, the natural ecosystem and encourage them to participate in games. This process of education in the natural environment inspired an Italian psychologist named Loris Malaguzzi (1920-1994) to create and develop a new educational method where the child is considered co-author of his own knowledge. Under the guidance of Malaguzzi and the staff of the Infant – Early Childhood Centre and Kindergartens in Reggio, worked together on a philosophy of education able to maintain the natural development of the pupil. Families and the community remained very involved in these process, and teachers in many active ways encouraged this involvement. Families, citizen’s councils, and school committees worked intensively with the municipality to support the schools and contribute to their development.

Although the Reggio background shares the values of other well-known educational methods such as Montessori, it is not a philosophy with a belief system like the previous methods. Instead, the Reggio Emilia principles are based on the steady foundational values of a child’s learning. These values are not only for preschools or primary schools, but also can be beneficial in diverse circumstances, and in several ways, suitable to specific conditions.

52 2.2

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

REGGIO’S METHODOLOGY: A PEDAGOGY OF RELATIONS

Through the years, the Reggio approach has developed a philosophy based on a solid relationship between children, teachers, parents, educational coordinators, and the community. The municipal-run schools have always been committed to progressive thinking and advancement on an educational project centred on the child. This aspect, therefore, translated into a community-based project. Schools are linked directly to the Institution through the board of directors and the general director. The Institution works closely with a group of curriculum team leaders or advisers, also known as pedagogues, whose role is to coordinate the teaching within a group of schools and centres. In terms of staffing, the school comprises two teachers per classroom, one atelierista (a specialist in the art field), a cook and other auxiliary staff such as kitchen assistants and cleaners, who are all equally considered to play fundamental roles in the life of the school. There is no headteacher nor promoted staff structure. Teachers work in pairs and remain with the same group of children for three years; hence developing a sense of community.

Fig. 2.4 Child playing in the Atelier

Fig. 2.4 Child playing in the Atelier

53

BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

Fig. 2.5 Diagram showing the elements at the base of the Reggio approach

Most of the educational activities occur in the morning. Children have lunch together and then dedicate part of their afternoon to bedtime. As no hierarchy exists within the school staff, teachers are involved in all aspects of the daily routine, including meal times and bedtimes; thus emphasising the ethos of collectivity and participation through all the areas of school life.

Differently, from other pedagogies that cannot be guilty of treating early infancy as a preparation for later childhood and adulthood, the Reggio Approach considers early childhood a distinct developmental phase in which pupils can demonstrate an extraordinary curiosity about the world. This image of the child has a cardinal and overarching effect on the learning and teaching methods in the schools. Indeed, the pedagogical foundation of the whole Reggio approach is considered as the pedagogy of listening as it represents a metaphor for the educators’ attempt to gain a deep understanding of the image of the children and their learning processes.

“Our image of children no longer considers them as isolated and egocentric, does not only see them as engaged in action with objects, does not emphasise only the cognitive aspects, does not belittle feelings or what is not logical and does not consider with ambiguity the role of the reflective domain. Instead our image of the child is rich in potential, strong, powerful, competent and, most of all, connected to adults and children.”

Loris Malaguzzi

SCHOOL STAFF

CHILDREN FAMILIES

54

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

SPACE: THE METAPHOR OF KNOWLEDGE

The pedagogical value of the physical space in Reggio preschools was evident from its early conception. The attentive organization of the school environment, its role in provoking the child’s natural curiosity, allowing for a multitude of ways of self-expression and interaction, is what gives it its status as “The Third Teacher.”

Participation and collectivity, key ideas that permeate all areas of the Reggio Approach, are vital when considering the creation and use of the school’s physical space. Instead of separate spaces, Reggio’s schools are characterized by a series of connecting spaces that flow into one another. Rooms open onto a central piazza, reflecting the central meeting places of the town, and children can move freely through it. This type of freedom is conducive to participation, interaction and the many differences that children, teachers and the community bring to the schools. Children are full of curiosity and creativity, and these qualities are consistently emphasized in a Reggio-inspired classroom. In a typical Reggio classroom, there are no assigned seats. Children have easy access to supplies and learning material, so they are consistently inspired and encouraged to direct their learning. Since pupils learn directly from their learning environment, a Reggio-inspired section is set up in a way that is meant to reflect the culture in which the child lives. For example, mirrors play a crucial role within the learning environment. They hang from the ceiling, can be found at floor level, and are in various shapes that the kid can enter to explore. Children, therefore, gain an understanding of themselves about their surroundings, a belief central to the Reggio philosophy.

The importance of the aesthetic dimension for learning has already been mentioned. This is very much evident in the schools’ physical makeup. These schools are multi-sensory environments, where art materials can be displayed in many ways and for different reasons, encouraging the child to look at shades, colours, textures and smells. The outside environment reflects this conception; plants are widely used in classrooms and interior courtyards. This fosters a link with the outside environment, essential because children learn how to become whole and active participants within the surrounding environment.

55

BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

Fig. 2.6

Diagram showing relation of spaces in Reggio Approach

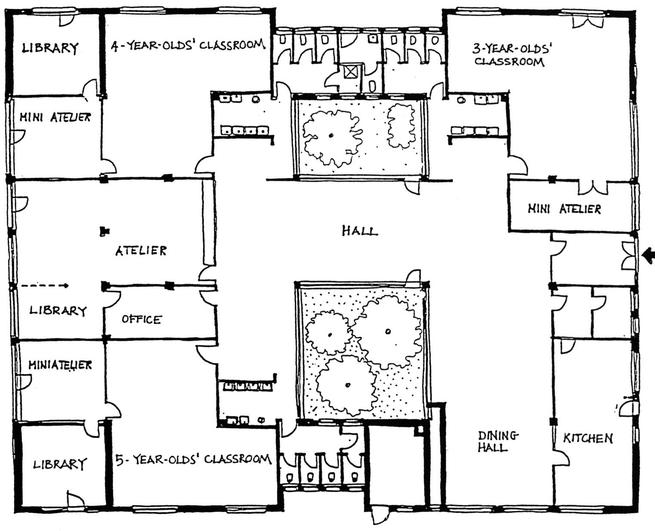

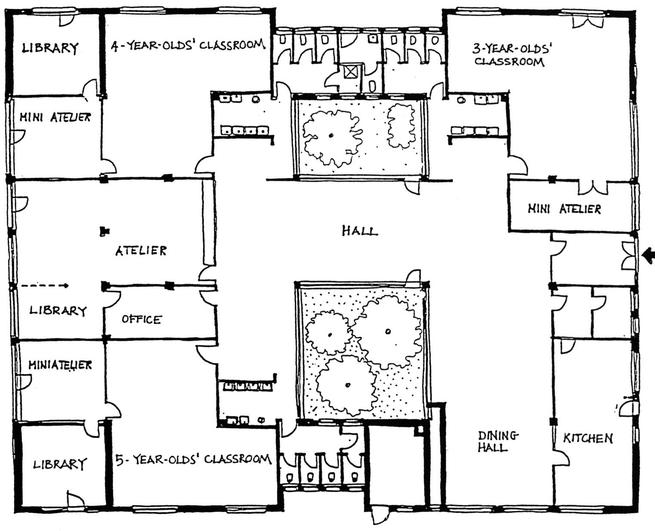

On the ground of this, Reggio schools require an environment that allows for tremendous flexibility within a spatial-structural system. For this reason, each school comprises three indistinguishable spaces: a piazza, an atelier and a cucina.

The Piazza - The heart of a Reggio-inspired school is the piazza. In Italian, “piazza” translates to “square,” and you can see it as analogous to a town square in a Reggio Emilia school. It’s a central, open space where the entire school can gather but can also be readjusted to accommodate a wide variety of learning activities and groupings, from individual projects and small group experiments to more extensive group presentations and activities.

The Cucina - Practical living skills are woven into the dance of a typical day, and the Cucina (kitchen) is pivotal. It’s not just a place to consume a midday meal; care is taken to make the kitchen accessible for the young learners it serves. Counters and tables are low so that children can participate in the creation, serving and clean-up of food so that the entire process of a meal can serve as nourishment for the body and mind.

The Atelier - The atelier is the hub of artistic endeavour. In many Reggioinspired schools, there is a full-time atelierista whose aim is to coordinate with the teachers by guiding the creation of the children’s works. The results are typically significant for the child’s development. Still, they are only the first step, as the Reggio method prioritises representing the work to the parents, the community, and most importantly, back to the students.

SECTIONS

ATELIER

LIBRARY AGORA’

KITCHEN

56

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

BEST PRACTICE: THE MOST BEAUTIFUL SCHOOL

The Reggio approach lays its fundamentals in communication, that social exchange is, in fact, according to its philosophy, the key trough that leads children to experience the world that surrounds them and the main way through which they build their idea of what the world is. In the Diana school, considered as one of the best practice through the Reggio Emilia approach, the space is not a mere box containing people, but it has the higher aim of facilitating and encouraging human interaction both within peers, such as students and also between the staff and the parents, always focusing on the well-being of each and every person inside the school. The space is designed to favour exchange and it clearly shows in fig 2.7, that the Piazza is the central and predominant feature, serving as the aggregation point and the link between classrooms, small on purpose, to incentive communication and better focus on each student, common spaces and the Atelier, a feature of the Reggio method. The Atelier is a creative endeavour, a heaven in which children can express themselves freely though both physical and digital art, under the surveillance of an art-oriented, trained teacher; the Atelierista.

Fig. 2.7

Ground floor scheme, Scuola Infanzia “Diana”Reggio Emilia

57

BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

Moreover, each classroom also has its own mini-atelier, a small room that provides the tools and activities planned in the main Atelier. Another important part of the Diana school is the kitchen, an intergenerational space in which the cook and his/her staff work alongside a small group of children everyday, following the recent wave of interest that links children and the kitchen and the possibility to explore the world and the senses trough taste and food. Children not only explore trough food, but by setting the tables, they also acquire aesthetic and logical skills. The dining room, as well as the washing room and the bathroom all have a strong relational connotation and are all aesthetically pleasing and allow children to be playful.

Glass walls and aerial sculptures made by children allow the space to be light and to interact with outside green areas, creating a sense of union and cohesion, but nooks for those who wish to stay on their own are also present. The planning of each day shows the great attention that Diana school and staff put on each and every child, in fact, every day, after the morning meeting. Children can choose whether to start one of the scheduled activities or to continue to work on a previous project. The materials are all previously prepared by teachers in an orderly and readily available way, resembling, as Malaguzzi says, a market stall where every item is enticing to the curiosity and one can freely select and play with one or more objects, an approach that is fundamental to let children constructively explore the world and their mind trough activities.

“Stand aside for a while and leave room for learning, observe carefully what children do, and then, if you have understood well, perhaps teaching will be different from before.” Loris Malaguzzi

58

BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

Fig. 2.8

Scuola Infanzia

“Diana”Reggio Emilia

59BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

LEARNING FROM REALITY

60 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM 2.3

Fig. 2.9 - Jacaranda school, Milan

Fig. 2.9 - Jacaranda school, Milan

61

BUILDING PEDAGOGIES

Architect: Labics

Area: 2000 m²

Year: 2019

Location: Milan,Italy

Intervention: Interior Renovation

Funds: Private Funds

Fig. 2.10

View of the Agorà

JACARANDÀ SCHOOL

The project of the Jacarandà kindergarten and nursery school stems from the desire to offer children aged between 6 months and six years a new gathering space for research and discovery that focuses on the children’s joy for learning and creativity in a innovative educational context in Milan. The general objective was to create a space with a high pedagogical profile. For this reason, the design consists of renovating and re-purposing a former car showroom to insert a nursery on the ground floor, a preschool on the upper level and a swimming pool in the basement.

Inspired by the philosophy of the Reggio Children approach, the project is based on the belief that the quality of play, material and immaterial, is a central component in making the educational experience rich and varied. Following these principles, the interior space has not been conceived as a mere container for activities but rather as an articulated structure characterised by the presence of public, semi-public, and private rooms in which the users -children and educators- can meet. In this sense, the school is thought of as an active tool for growth and experience, an interactive space capable of stimulating curiosity and interpersonal relationships, but above all, enhancing an idea of community.

62 BEYOND THE CLASSROOM

Fig. 2.11 Map showing the location of Jacaranda school