On Motive

The site analysis is a false premise in architectural education, doomed from the start. Students are taught to complete a largely performative sequence of tasks, frequently irrespective of condition and context:

Sun path

Wind rose

Pedestrian flow

Site utilities mapping

Terrain analysis

Watershed calculations

Completed

Completed

Completed

Completed

In Progress

In Progress

Under these metrics, the local texture of a site is reduced to data and visual analysis. Research may extend to surface-level statistics or involve community outreach, but the essence of the place is rendered flat regardless. When this same treatment is thickly applied to begin our understanding of professional responsibility, a level of care and delicacy is lost and unrecoverable.

Architects may not be prone to archival research, but they are prone to precedent analysis and informed decision making. This is not to say that a sunpath is irrelevant; I simply stand to propose that alternative epistemologies may bear sweeter fruit. Oral history is more efficient and cutting than any simulation. Overlay the two techniques of analysis - one of unearthing, and one of surveying - and we as practitioners can strike a poetic balance of thought and care. Head and heart.

This project was limited, to varying necessity, by the bounds of an architectural curriculum. A semester schedule does not easily facilitate archival visitation, fieldwork, reflection and response. Nor did New Hampshire’s weather patterns (or lack thereof) make field research any easier when time was otherwise on my side. In spite of it all, this project was enabled, above all else, due to a sense of duty to the place and to the land I call home. It’s a bitter irony that an architectural education too often pulls one away from the formative places of their past, where they cut their teeth on the built environment. Perhaps that’s the point - maybe we can’t see what’s right in front of us, what we’ve been conditioned by and among. Maybe disorientation is the only productive path forward when you don’t know right from wrong.

Over the past three and a half years, I’ve gained knowledge and skills I hadn’t dreamt of, and honed them all working with strangers in strange lands. If I believe architectural practice is innate, and inherently good, then introspection is critical. A return to my origins offered the most challenging and most rewarding semester of my academic career - at the end of my journey, it allowed me to reciprocate the gifts I’ve been given. To examine the built legacy of the places I come from, the spaces that shaped me, and the people who came before me. It allowed me to push the scope of an architectural project, and to bring it into the realm of anthropologi-

cal study. I’ve come to see architecture as interdisciplinary by nature. This field is at its strongest when it escapes the echo chamber and involves disparate areas of study. The architectural perspective is too often a narrow view. This project required analysis and interpretation of matters of biology, ecology, zoology, geology, anthropology, engineering, urban planning, and material science - fields where I can tread, but am no expert. There were two options presented: sink or swim. I leaned into the uncertainty and embraced its opportunity. Uncertainty can be fearful, but it can breed optimism, too. I chose the latter tactic, one of optimistic speculation.

The conclusions of this story are not cut and dry. All remains open to interpretation and conversation - engagement with this narrative is the ultimate objective. The end point of this semester’s arc is not finite, but born of multiplicities. One cannot predict today the total resolution of hundreds or thousands of individual actions, but wading into uncertainty remains the only path forward for the future of the Blue Mountain Forest. This thesis project takes the first step.

forensic evidence marker, typical, print + fold template used to mark and categorize material data

Fig. 1

2.5” x 8”

What is speculative design?

Speculative design is practice concerned with future proposals of a critical nature that are not market or profit driven, but are anticipatory of potential consequences within future conditions and contexts.

Why does public land access matter? More simply, why is it a good thing?

Accessible conservation and ecological stewardship within public lands facilitates recreation, preserves cultural history, and promotes public health. Generational public access fosters a sense of collective commitment and shared responsibility towards the continued management of land - our greatest natural and mnemonic resource.

What future socioeconomic and environmental conditions could impact the distribution and legal standing of public lands in the U.S.?

Faced with the spatial and economic consequences of global climate change, late-stage capitalism has given rise to increased privatization of land and consolidation of natural resources. Accessibility and protections for public land will be challenged as the aims of private development increasingly lie at odds with processes of preservation and stewardship.

How can we trace the erasure of sites of collective memory through forensic analysis of spatial conditions?

How can the privatization of public lands and the folly of wilderness be deconstructed as both a technique of dispossession and a spatial typology?

Site specific data collection through both digital means (LiDAR scans, surveying equipment) and archival technique (historic accounts, oral histories). The privatization of public lands and the fortification of private property can be simultaneously studied with the game reserve typology; a privatized hunting construct.

Thesis Statement

Accessible conservation and ecological stewardship within public lands facilitates recreation, preserves cultural history, and promotes public health. Generational public access fosters a sense of collective commitment and shared responsibility towards the continued management of land - our greatest natural and mnemonic resource.

The Blue Mountain Forest offers grounds for rich typological analysis on the limits of private land, the potentials of the public commons, and the infrastructural realities of private game reserves in the United States. Deep site analysis and forensic research can seed architectural and systemic responses, prototyping the methods and materials of a new, radical public accessibility. Three speculative levers operate in tandem: legal action, ecological restoration, and infrastructural reckoning. This workflow, while inherently site-specific, lends thought to future methodologies in re-activating similar spaces of privatized stewardship.

Fig. 2 Choice White Pines and Good Land, 1991

Fig. 3 Wild Life in the Blue Mountain Forest, 1929

Fig. 4 War Whoop and Tomahawk, 1931

Fig. 5 Nature Magazine article, 1924

Fig. 6 Newspaper clipping, 1906

Fig. 7 Park postcards, 1906-1910

Page 22, Counterclockwise from Top Left:

Fig. 8 The Baker House, c. 1940 (Courtesy of Plainfield Historical Society)

Fig. 9 Original fire cabin, Croydon Peak, c. 1910 (Courtesy of Croydon HS)

Fig. 10 Stone wall with gate, c. 19001910 (Courtesy of University of New Hampshire)

Fig. 11 Austin Corbin II, c. 1880

Fig. 12 Settlement, Plainfield, NH, c. 1900 (Courtesy of Plainfield HS)

Fig. 13 Original fire watchtower, c. 1910 (Courtesy of Croydon HS)

Page 23, Clockwise from Top Left:

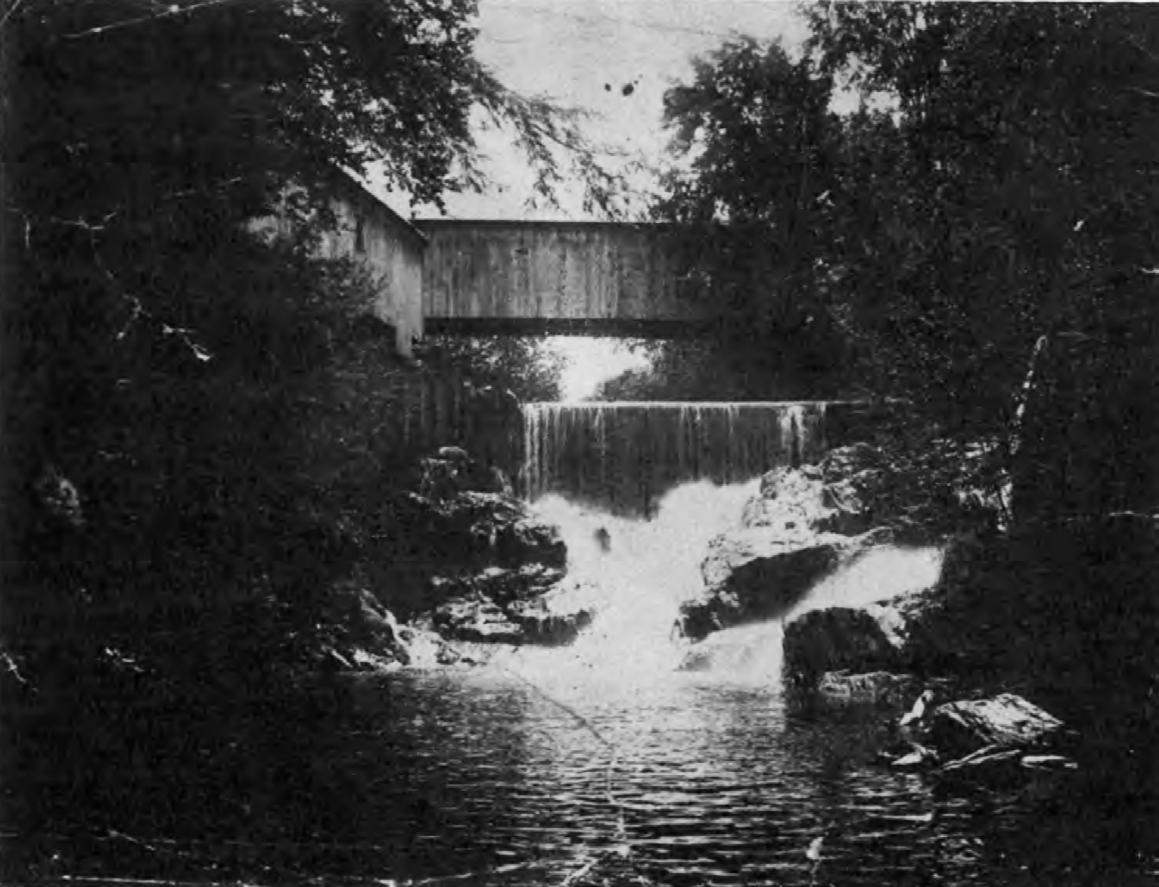

Fig. 14 Silsby Mill, Meriden NH, c. 1900

Fig. 15 Kimball’s Mill, Meriden, NH, c. 1900

Fig. 16 Bison delivery, Corbin Park, c. 1900 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Page 24, Counterclockwise from Top Left:

Fig. 17 Locals visiting the Park, c. 1900 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Fig. 18 Buffalo bull in colonial ruins, c. 1900 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Fig. 19 Park chef with pronghorn antelope, c. 1900 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Fig. 20 Chinese silver pheasant, c. 1900 (Courtesy of Plainfield HS)

Fig. 21 Elk hunter in the Park, c. 1940 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Fig. 22 Buffalo bull in pen, c. 1910 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Page 25, Clockwise from Top Left:

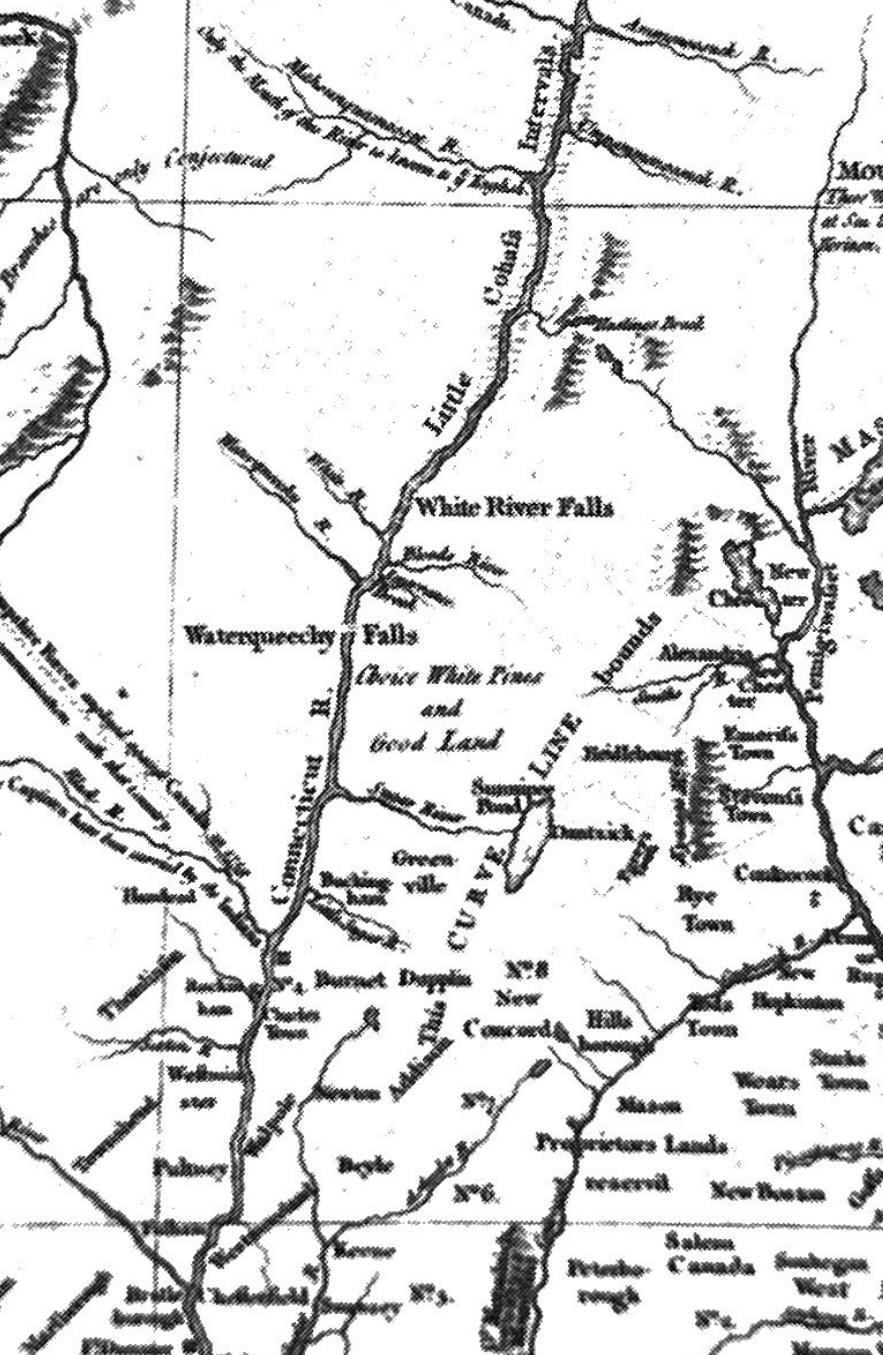

Fig. 23 Detail, “An Accurate Map of His Majesty’s Province of New Hampshire in New England”, 1761 (Courtesy of UNH)

Fig. 24 Himalayan mountain goat, c. 1900 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Page 26, Counterclockwise from Top Left:

Fig. 25 Stone ruin in the Park, c. 1920 (Courtesy of Croydon HS)

Fig. 26 Abandoned farmhouse, c. 1900 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

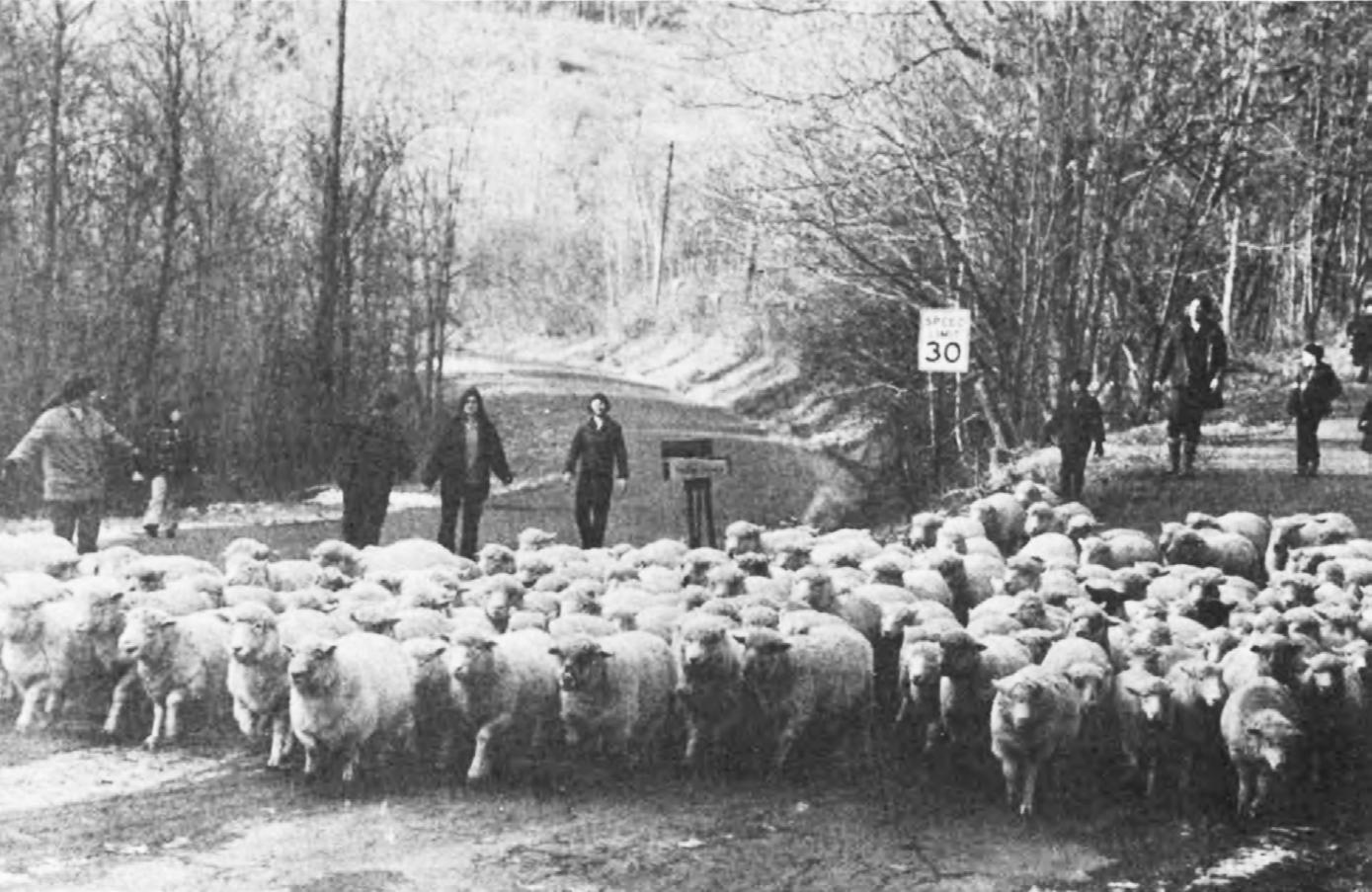

Fig. 27 Sheep drive on Jenney Road, Meriden, NH, c. 1970 (Courtesy of Plainfield HS)

Fig. 28 Hurricane damage, 1939 (Courtesy of UNH)

Fig. 29 Abandoned farmhouse, c. 1910 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Fig. 30 West Pass gatehouse, Corbin Park, c. 1920 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Page 27, Clockwise from Top Left:

Fig. 31 Corbin estate, c. 1920 (Courtesy of Newport HS)

Fig. 32 Wildfire containment, 1953 (Courtesy of The Valley News)

On Methods

Archival research was performed at three primary locations: the Plainfield, New Hampshire Historical Society; the Newport, NH Historical Society; and the Croydon, NH Historical Society during August 2024. Volunteer staff at all three institutions were instrumental in finding relevant material and aiding the research effort. Material was sorted, categorized, digitally scanned or otherwise documented, and returned to storage - no material was borrowed or removed. One day was spent in Plainfield, one day was spent in Croydon, and analysis of Newport’s sizable archive was broken up across four days.

Some material had accompanying notation, whether scrawled in the margins or typed up as companion documentation. Relevant notation was cross-referenced against similar photos and contemporary maps to properly locate and categorize image content (e.g., “Camp Six”). The majority of existing archival material on Corbin’s land holdings and the Blue Mountain Forest Association - the organizational body that manages them - consists of photographs taken between 1900-1925. Some official correspondence and survey documentation was uncovered, which ultimately proved critical in understanding the organization’s legal structure and physical limits.

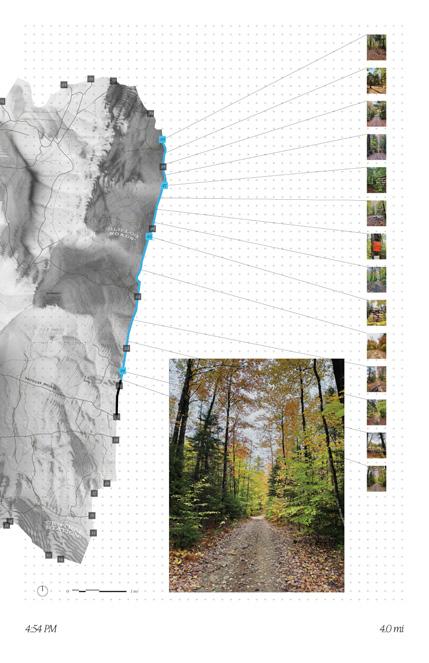

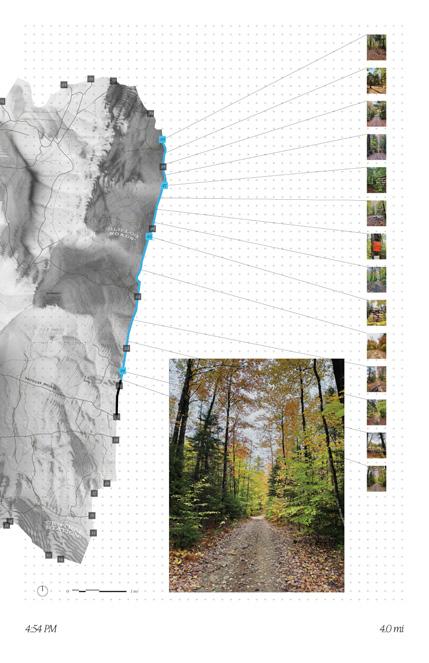

The most recently published, publicly-available map of the Blue Mountain Forest was created in 1946 - beyond that point, increased security and secrecy quelled any external leaks of spatial data. While a 78 year old survey is far from perfect, it provided a base point from which GIS data could be overlaid and adjusted. The land holdings of the Park are bounded on all sides by a mixture of accessible routes and Class VI roads - defined by the State’s Department of Transportation as unmaintained highways; roads subject to gates and bars whose surface has not been maintained or repaired by a municipality for at least five successive years. While forest cover posed an additional challenge, these routes and their intersections are visible in satellite imagery. By plotting historic boundary points and harvesting U.S. Geological Survey topographic data, a to-scale digital reconstruction of the landmass of the park was created. A parallel effort of intimate investigation supplemented this removed technique of mapping: I conducted interviews with local residents, traveled the perimeter of the fence line, and captured drone videography of the Park interior, using public cemeteries beyond the fence as covert launch sites.

Once a digital twin had been reconstructed, technical and anthropological research data was translated into plotted points and spatial analysis, painting a picture of this landscape and its conditions over time. Interdisciplinary content was woven into a master timeline - tying together actors in land stewardship, state forest cover, and climatic eras. The woven narrative of place, voice and time served as both a scale of impact and a site of intervention. Working through this timeline, the project output is sequenced through successive phasing; here, it is impossible to enact change in one fell swoop. Assuming remarkable State action in 2025, the year this work is published, Blue Mountain Holocene envisions a 51 year course of action to right the ship and seed a culture of care.

Scope and Speculation

Sacrifices were made in the realization of this project - primarily, in prioritizing breadth at the expense of depth. This is more akin to the beginning of a life’s work, as opposed to the culmination of four months’ work - it was not conceived to be undertaken all at once. To study many facets of the Blue Mountain Forest simultaneously, to envision timescales beyond the present - the element of total control had to be relinquished. The most critical aspect of Blue Mountain Holocene is the contextual world building it operates within; a flexible framework which includes cues that strengthen the proposal as well as assumptions that undermine it.

The resulting intervention operates squarely within the realm of speculative design - a subfield concerned with critical future proposals that anticipate systemic issues of design and advocacy. Firstly, this project anticipates significant increase in global temperatures, mass species migration, and a sixth extinction over the next 75 years, resulting from ongoing effects of anthropogenic climate change. Secondly, this project anticipates coming debates over the merits of public land access and the ethics of private ecological stewardship.

The first quarter of the 21st century has seen increasing conservative momentum towards the sale, privatization and development of federally held, protected land across the United States. In 2017, President Trump lifted protections in Utah’s Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments, repealing their protected monument status in an effort to open the lands to private contracts for coal and uranium mining exploration. Similar efforts in Alaska have fought fierce litigation, and the same administration’s recent re-election forces these crises to the thematic forefront once more. Furthermore, millions of state and federally protected acres of public land currently lie landlocked; islands of access surrounded on all sides by private development. In these cases, one must illegally trespass to access public land; excercising a civil right first necessitates crime. The state and security of America’s public lands are in limbo now more than ever. Worse than outright confrontation is the collective erosion of public sentiment towards this resource. Poor knowledge sharing and disinformation have bred contempt and apathy for the continued stewardship of our greatest public good.

While no one knows for certain what the future may hold, design practitioners have an obligation to hope for the best and prepare for the worst. As an independent case study and a toolkit for public access, the methodology this project proposes should become increasingly useful for those opposing widespread erasure of the commons. Straddling rogue activism and systemic reinvention, Blue Mountain Holocene seeks a poetic balance: real enough to enable actual execution, while optimistic enough to spur radical change. The limits of these two approaches, I’ve found, are not mutually exclusive - at times, I struggled to ascertain any distinction at all between the tangible and the theoretical. With this mire comes the risk that both aspects ring hollow, as shallow reflections of one another - but also the freedom of a natural indeterminism; the unique ability to perch on a moving branch.

“The park has almost a mystical proportion to it. You know, the Park - we all know what the park is. You know, Corbin’s Park - it’s really the Blue Mountain Forest Association - but it’s Corbin’s Park. Who the hell was Corbin? Not many people know who he was. Corbin was the epitome of an evil robber baron... He’d screw anybody if he could. We all know it’s there. Nobody has much curiosity about it - it’s just a given, it’s like a rock formation; okay, it’s there, nothing you can do about it. Live with it.”

Steve Taylor, Plainfield, NH native 2024

Royal chases, a type of Crown Estate holding originating in the United Kingdom, reserved land and hunting rights for members of a royal family. Once a common typology as a spatial remnant of feudal politics and class-based social relations, royal chases faced mass enclosure by Private Acts of Parliament between 1600-1850. While hunting rights had long been privatized, legislated and prosecuted, chase lands themselves had oft been commonly held - still accessible by the public for recreation and enjoyment. The public closure and privatization of access to chase lands during this 250 year period facilitated ensuing private construction: residential, commercial, and industrial development for the wealthy at the expense of public land access. As a result, most medieval chases have been splintered and broken into smaller parcels of land over time. Some historic sites, such as the Malvern Chase and Wyre Forest in Worcestershire and Shropshire, England, have been protected and enshrined for future public use due to their cultural resonance.

Deer parks evolved out of royal chases throughout medieval and early modern Europe. These constructs were traditionally defined by a ring embankment topped with a wooden stake wall; a rudimentary perimeter enclosure. Just inside the fence, a ditch would be dug - permitting wild deer to climb the embankment and jump into the park, while discouraging animals from escape once inside. This special construction effectively increased the height of an enclosure. Inside, the landscape would be pruned and curated to appeal as deer habitat and hunting grounds. Undergrowth was eliminated in favor of sprawling pasture - providing clear sightlines of dogs while hunters rode on horseback - while mature trees were preserved as forage.

Game reserves, also known as game parks and game preserves, are modern descendants of chases and deer parks. Popularized in the late 19th century in Europe as an aristocratic reaction to impending extinctions, and representing a form of environmental imperialism, game reserves today are prevalent on each continent aside from Antarctica. The United States, in particular, has a concentration of private game reserves - usually called ranches or game parks. These holdings constitute a typology of enclosed tracts of lands where animals - often introduced, non-native species - are methodically hunted in controlled sport. Access to the land and its resources is typically gated, both physically and systemically: reserves such as Corbin Park operate through a membership system and an annual fee schedule. Modern game reserves represent a sizable niche in the outdoor and tourism economiesat scale, as seen in countries such as South Africa, their services can even render a large proportion of national gross domestic product. It the United States, many game reserves introduce species deemed ‘invasive’ or ‘exotic’ within their respective contexts. These sites offer scientific study of hybrid ecologies.

Complex networks of infrastructure govern these constructs. One ubiquitous form is the perimeter fence - the first layer of protection, and the last line of defense. In addition to fencing, Corbin Park employs locked gates, shift work of armed perimeter patrol, and security cameras to control access in militant fashion.

LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging) analysis of stone

Data harvested through the New Hampshire Stone Wall Mapping Tool, developed by NH Geological Survey and NH Granit

Fig. 33

wall ruins inside Corbin Park

100’

Patterns of Settlement

According to archaeological evidence, the first fence dates back to between 5,00010,000 BCE in the United Kingdom. Early fence structures were assemblages of stone and timber - not much has changed. Ever since this point, fencing structures have demarcated the private from the public; the individual from the commons - models of collective responsibility turned to “you take care of yours, and I’ll take care of mine”. The dominant gesture of the fence and the resulting, fragmented spatial conditions it produced changed the way we saw the land and valued access to the resources within it. Privatized land access privileged individual decision making over collective processes - it curated recreation and ecological responsibility for the privileged few and excluded commoners from rights of access and use.

The summits of Sullivan County - Croydon Peak, Grantham Mountain, Buffalo Mountain, Moose Mountain, and Black Mountain - produced a unique state of geographic isolation. The original land grants from the 18th century that divided the region into five towns (Plainfield, Cornish, Newport, Grantham, and Croydon) were drawn before the land had even been seen by its settlers. Over the first 75 years of occupancy, the agricultural lots were subsequently redistributed - impassible terrain was reallocated as interstitial space, running along the property lines. To this day, Plainfield, has two town centers: Plainfield Village is situated in a flat plain to the west, and Meriden Village is located in the foothills to the east. Meriden was created out of natural congregation: residents from west Granthamthe next town east - could not reach their own parish without trekking through the mountain passes. Through communion with the eastern residents of Plainfield, the community of Meriden was born; a model of collective inhabitance and worship irrespective of geopolitical boundaries. Those realities would catch up, naturally - by 1819, the western portions of Grantham and Croydon were officially annexed to Plainfield and Cornish. The farming communities at high elevation operated nearly independently from the lowland town centers - these high settlements relied on mutual aid and managed a joint pastoral resource. The ridgeline offered seasonal grazing for flocks of sheep and cattle, and the land were shared and rotated. Extensive stone wall construction - evidence of clearing - is visible in LiDAR imagery. Forest and scrub brush obscures these lines of stone, these patterns of settlement, but a picture emerges nonetheless: Nazca Lines of livestock and abandonment.

The Blue Mountain Forest Association and the infrastructure of Corbin Park currently supplants these traces. Central Station, the headhouse of operations, is an expansion of an early 19th-century farmhouse. The Croydon Peak fire watchtower, part of a state network of survey points, was built in 1910 to protect the interests of the Park and the Draper Lumber Company, a historic logging outfit. Feeding stations and hunting cabins have been erected over scattered stone ruins - understandably, as existing agricultural clearings and adjacent road access offer two paths of least resistance in steep terrain. This region is saturated with plan overlay; an opaque juxtaposition of time and historic occupancy. The land rewrites itself - inscribing, rupturing, and returning to the fold.

Drone imagery of the land holdings of Corbin Park

Drone flown over perimeter of the park to observe forest cover and distribution of buildings. Public cemeteries served as covert launch sites.

Fig. 34

Semi-Circular Construction

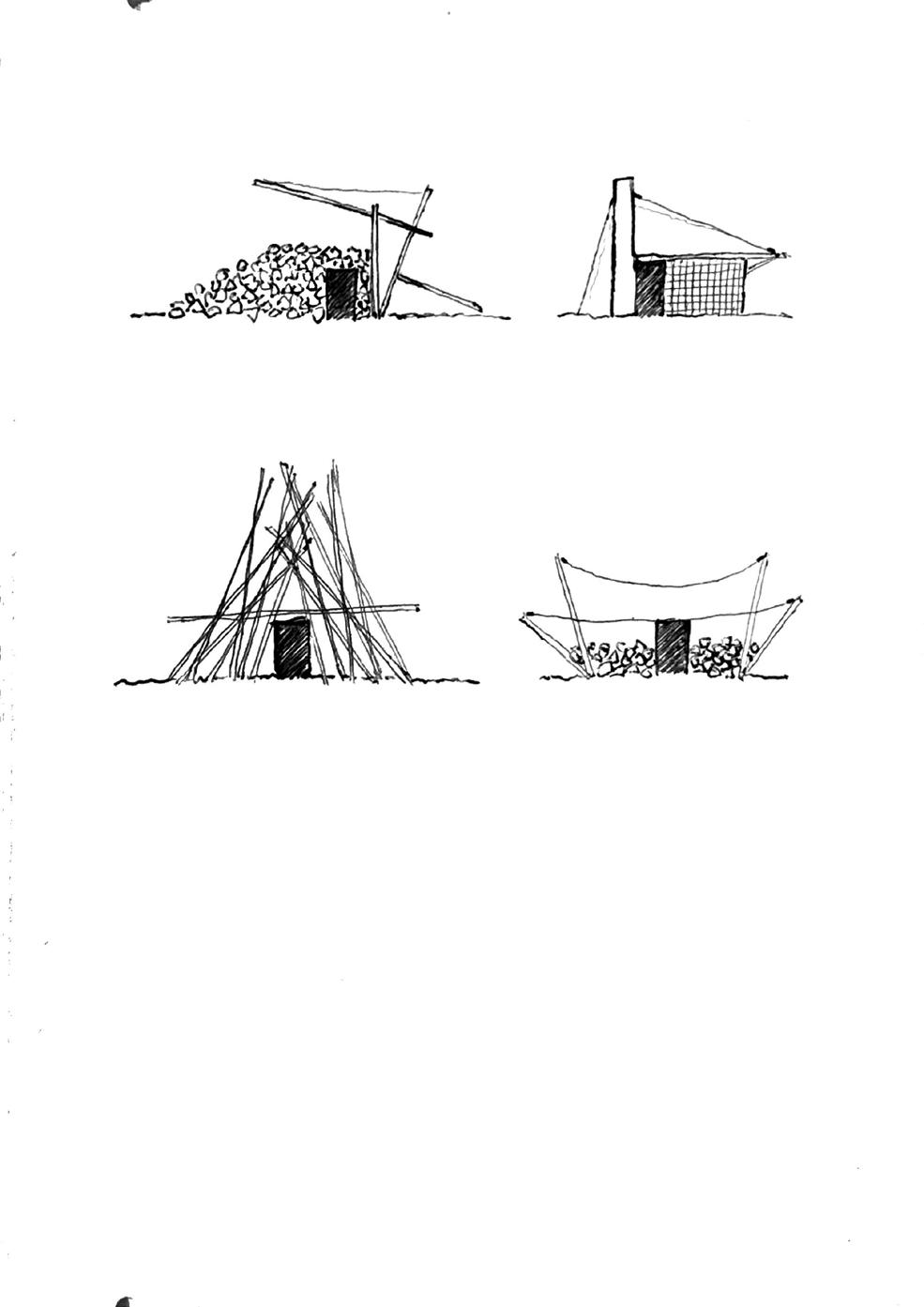

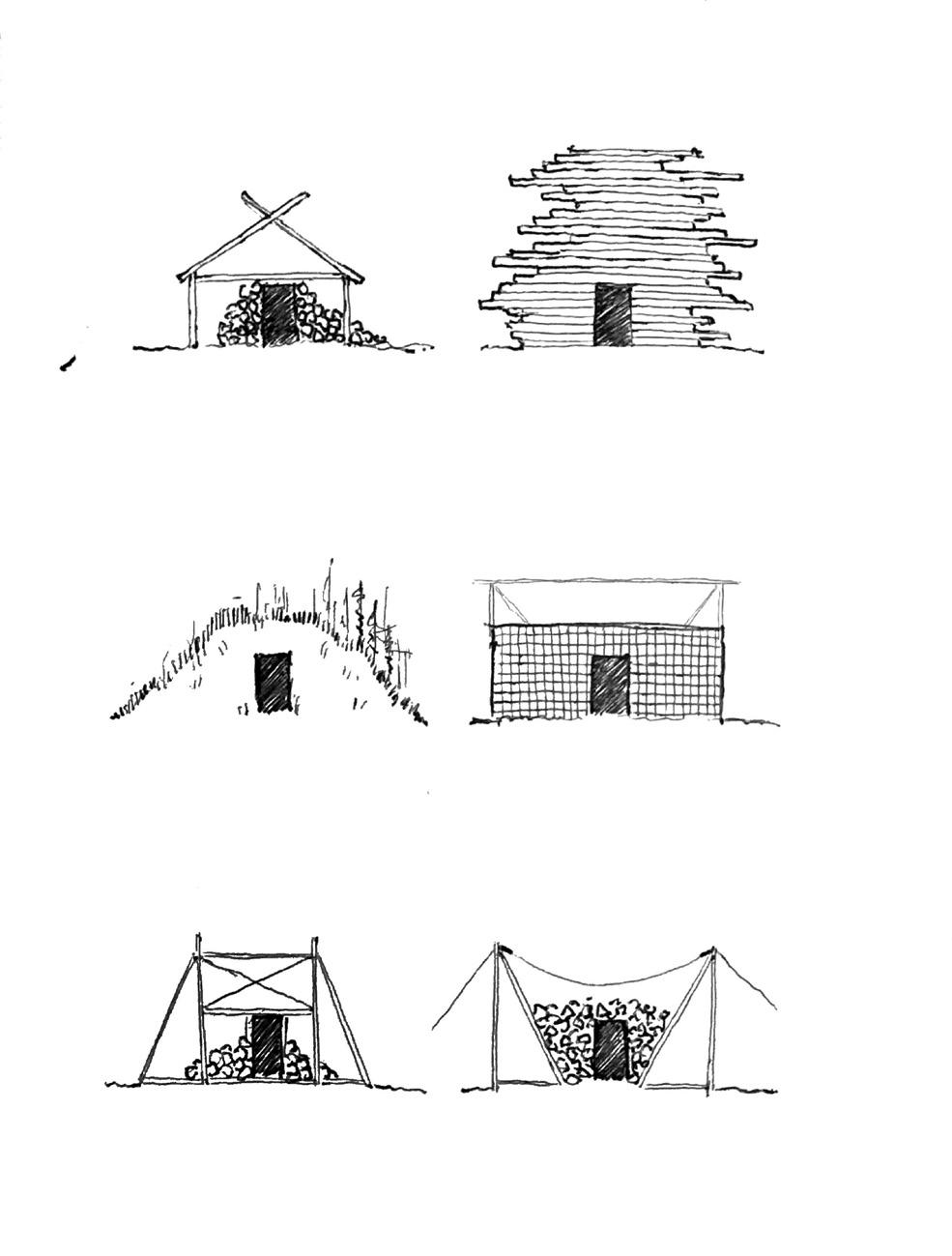

In seeking deconstruction and new forms of architectural and ecological preservation, sites such as Corbin Park can undergo material mining and harvest. Timber and stone are born of this land - they’ve remained for millenia, and endure in this context as timelessly viable construction materials. This project does not seek a return to a pastoral state, nor blind deferment to future-facing proposals. The answers do not lie in faithful reconstruction or dystopic assimilation. Assessing existing materiality and reactivating privatized infrastructure through processes of deconstruction and phased reuse engages this site in the present moment - the only timescale which provides real traction for advocacy and engagement.

Over the last 15 years, the state of New Hampshire has funded research to better understand the legacy of its stone walls and ruins. The open source NH Stone Wall Mapping Tool, developed by the NH Geological Survey and NH Granit, allowed for image capture and data retrieval. As revealed through LiDAR analysis, there are nearly 74 miles of stone walls remaining inside the Park boundary. Assuming typical dimensions of 2’-0” width and 2’-6” height, one can conservatively estimate the total volume of loose, stacked stone in the park to be nearly 2,000,000 ft3 in aggregate volume. For all intensive purposes, the sheer quantity of available, accessible stone is limitless. This can best be repurposed in the form of gabion structuressteel frameworks which give loose stone physical bounds and material performance.

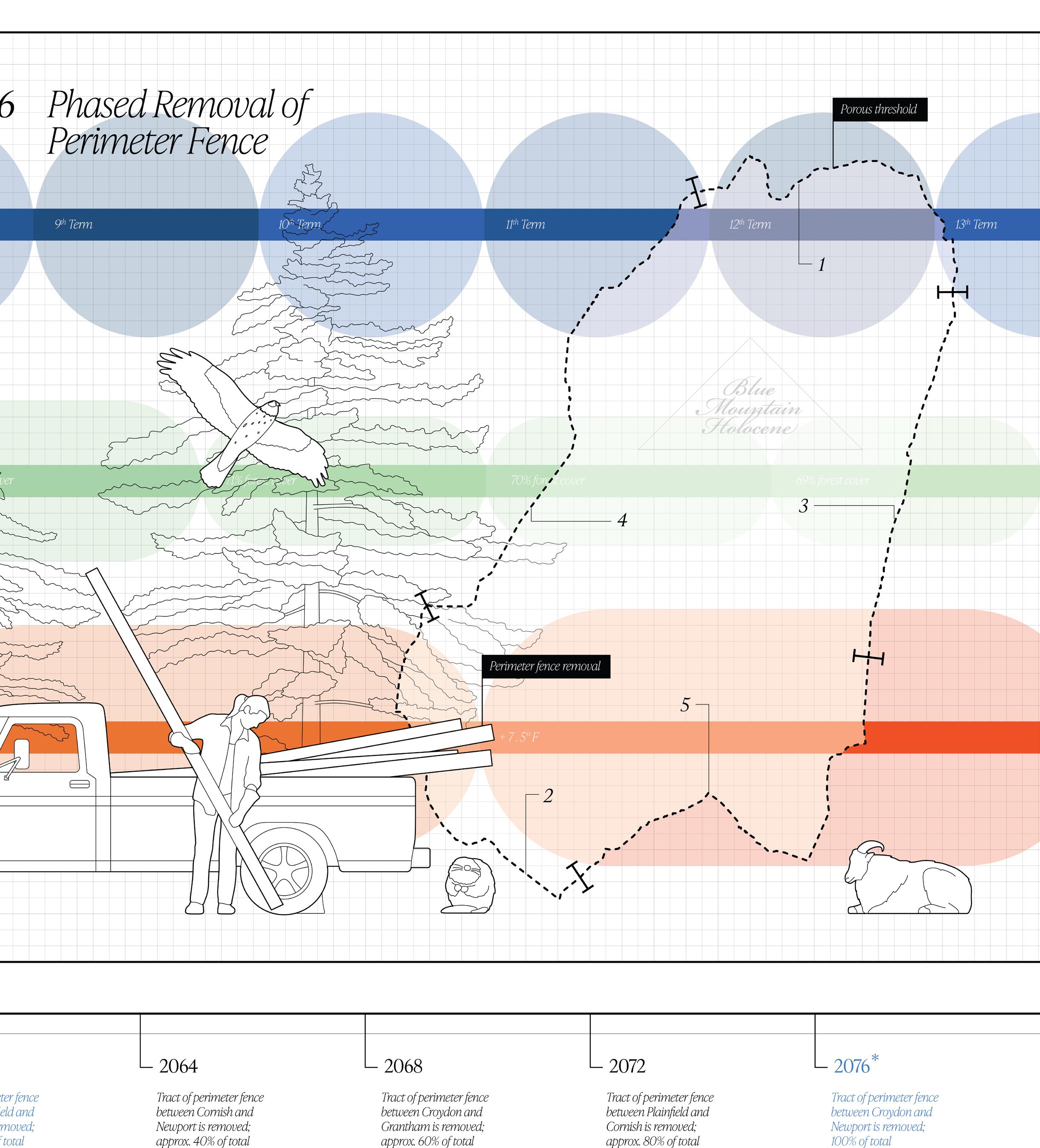

Steel mesh for gabion structures can be acquired in the potential reuse of nearly 30 miles of perimeter fence that enclose the Association’s land holdings. Standing at 12’-0” high, with an additional 4’-0” extending underground (assumed to be corroded, and omitted from these calculations), this membrane amounts to nearly 1,900,000 ft2 in aggregate area. Fencing is supported by timber posts; rough hewn logs sourced directly from the park grounds. While many stand in states of rot and disrepair, some of this lumber - close to 190,000 log feet in all - can support milling and refinement. Of course, the material opportunity of this site of intervention relies heavily on assumptions of access and containment. Blue Mountain Holocene ultimately seeks a removal of this fence predicated upon the collaborative expertise of interdisciplinary actors and data produced by future fieldwork.

In order to work closely with the land, local sourcing was considered as fundamental to circularity. Predating any aesthetic specificity, this adaptive material logic and binary palette was applied to the project’s design approach. It is the intention of this work that all goods be sourced from within the immediate vicinity of the site in question. With this in mind, techniques of forensic material analysis doubled as physical inventory for construction. Structural typologies emerged naturally from the parameters provided; from the mediums offered by existing conditions. Timber and stone have long been reused in New Hampshire - the beam of a barn is torn down and made the rafter of a house. A fieldstone is rolled from the wall to the foundation. This resource sharing is fundamental to the commons, indicative of mutual commitment, and sustainable over time.

Fence Forensics

I’ve never entered the grounds of the Park - the closest I’ve come is the perimeter fence line. Almost no one I know has ever seen the interior, much less entered it physically. Fence forensics was a day in autumn; an October trek through the familiar and the unknown. It was both pilgrimage and communion. This was a moment where the field condition confronted historic data head on, leaving more questions than answers in its wake.

There are 40 historic access points to this landscape. Each was the location of an original gate, the mechanisms of entry that replaced the breaks in common fieldstone walls. Around 15 critical gates were paired with ‘gatehouses’; residential buildings preserved near the edge of the park where staff would be stationed to manage public access. When the Blue Mountain Forest Association and its private membership system was formalized, the ousted public still maintained some avenues for entry. One day a week, these main gates could be unlatched, allowing for free travel and recreation. Horse-drawn carriages carried passengers through agricultural fields and mountain passes, allowing for collective engagement with the landscape. This tradition ended sometime between 1915-1940, and with it went the last gasps of community engagement. When natural disasters (a 1939 hurricane, and a 1953 wildfire) damaged the park and its perimeter, the Park superintendent tightened his grip. The infrastructure that was rebuilt would no longer serve as an intermediary body; it would perform as a militant edge.

This edge condition is patrolled along the inside by private security. In the warm months, daily patrols are completed by ATV, or pickup truck, and winter patrols are performed on snowmobiles. As an act of rogue analysis, I mirrored this pattern of movement - determined to investigate the realities of the maps I had studied and redrawn. Starting at the Sawyer Brook Gate in the northeast of the Park, I mountain biked south, tracing the fence line for roughly 4.5 miles. Tracking my position via GPS signal, and avoiding treacherous terrain, I stopped periodically to verify the presence of access gates where visible. Over the 4.5 mile stretch - roughly 20% of the full perimeter - half of the gates I expected to find had vanished. 5 of 10 had been removed and infilled with fencing, and the others were uncovered in varying states of disarray. Even when a gate was present, deferred maintenance and fallen logs barred entry and rendered its utility obsolete.

Over time, as I confirmed in the field, many of the gates were erased and committed to collective memory. Rather than maintain the storied access points, Park management allowed the undergrowth to envelop the perimeter. There are segments of fence that are nearly indiscernible from the surrounding vegetation - that, I’ve decided, is part of the point. The Blue Mountain Forest Association, while rougher and seemingly less capable than I had imagined, still has access to the labor and the capital required for the continual upkeep of its infrastructure. By embracing ruination, the removal of public access points and the fortification of the fence represents an insidious, systemic stance on the authority of private stewardship.

“Where [Fire Lookout Towers] offer opportunities for unusual scenic panoramas and, at the same time, are conveniently accessible to the public, either by motor or by hiking, they constitute an important point of public contact and, as such, are worthy of the same attention to architectural treatment as any other administrative or recreation structure. Special sites of this character... call for a design comprising all the purely utilitarian fire detection facilities in a structure of attractive architectural appearance, (with an observation platform for the public), rather than the usual standard wood or steel Lookout Tower.”

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Standard Lookout Structure Plans 1938

The Five Town Model

The five towns that Corbin Park resides in - Plainfield, Cornish, Newport, Grantham, and Croydon, New Hampshire - all bear responsibility for the interstitial spaces between them. The Blue Mountain Forest is a fabled resource that spans borders and timescales. There is a marked appetite among locals I’ve spoken with to reconnect with this landscape, to venture inside and see it once more. While only a fraction of Newport lies behind the fence, around 40% of the landmass of Croydon is inherently inaccessible; it lies inside the Park for the exclusive use of private members. Every town has an individual relationship with the erasure represented by the Park. Each local population reckons with its own oral histories and ancestors.

Successful stewardship takes time and patience. While membership within the Blue Mountain Forest Association usually anticipates a lifetime commitment, any transfer of its 30 shares of ownership is closely guarded. Shares are frequently passed down through generations, or otherwise traded between close friends. No locals are known to be members. Its current stakeholders include: a serial entrepreneur looking to sell designs for stealth watercraft to the U.S. military; the CEO of a plastics manufacturer with a monopoly on nozzles for whipped cream bottles; the descendants of William B. Ruger, the co-founder of the second largest firearm manufacturer in the nation; and a descendant of the von Trapp family singers, who gained fame and escaped Austria in the interwar period. The cost of a share is rumored to be north of $1,000,000, and annual membership fees amount to six figures.

A serious amount of capital facilitates the curation and maintenance of this false wilderness. Ironically, the Park is run as a nonprofit, and receives tax breaks on land use and zoning. Under the 1895 Special Act of the New Hampshire Legislature that enshrined the total authority of the Corbin estate, all game within the Park was deemed descendants of private stock - inherently distinct from species committed to the public commons. Under this legality, some taking of game within Corbin Park may occur irrespective of licensure. While the average citizen hunter in the state funds conservation through firearm safety certification and hunting registrations, the members of the Park do not answer to the New Hampshire Department of Fish and Game, and do not support its work through any direct financial means.

This is a twisted reality; a product of the inequalities of late capitalism and rampant privatization. This land should be managed by a local constituency of engaged actors, not a removed cabal of elite stakeholders. The State has grounds to revoke the authority granted in its 1895 Act through two thematic paths: ecological fragility and economic stability.

The first path acknowledges imminent dangers of anthropogenic climate change, including destruction of critical habitat and widespread species migration. Contiguous sites such as the Blue Mountain Forest offer refuge for myriad species - havens free of fragmentation and sprawl. Western New Hampshire is home to a number of threatened and endangered native species, including the bobcat, timber rattlesnake,

eastern cottontail, and common nighthawk. Stewardship of the Forest bears greater responsibility to support threatened native species than it does in caring for ill-suited exotics. Discourse on ecological preservation has changed dramatically since Austin Corbin II was alive. Gone are the days of picturesque gardens and species imperialism, of buffalo hunts and martyred taxidermy. While these introduced populations cannot, and should not, be eradicated from the site, more space must be created for native ecology to take root and flourish.

The second path seeks economic introspection and a shift in our fiscal priorities. Recreation and tourism represent key markets and critical opportunities for growth in the state of New Hampshire. Blue Mountain Holocene does not predict a world without capitalism, but it yearns for sustainable economic practices within this globally capitalist context. After all, how well will caribou fare as hunting stock in Sullivan County after another 50 years, as the average regional temperature climbs +/- 7.5˚F? There is more money to be made by opening this site to the public - but even more importantly, the impact of that funding could be more equitably applied. Thousands of constituents supporting collective care by committee is far more impactful than the potential reach of 30 millionaires. New Hampshire’s recreation industry must directly fund preservation and sustainable stewardship. This model is cyclical: land use funds protections, and protections safeguard land use.

Direct collaboration and discourse with the Blue Mountain Forest Association may prove productive, and is worth every effort. With intervention from the State Supreme Court, however, radical activism could circumvent an entrenched power structure and force the hand of the current Park stakeholders. In this scenario, a transitional government would replace the authority of the Superintendent: four public management departments could distribute expertise and represent collective sentiment.

LEXSEE 70 NH 488

New Hampshire v. Blue Mountain Forest Association

[NO NUMBER IN ORIGINAL]

SUPREME COURT OF NEW HAMPSHIRE

70 N.H. 488; 42 A. 857; 1898 N.H. LEXIS 26 January, 2026

DISPOSITION: [***1] Case Resolved.

HEADNOTES: Reversion of Proprietary Rights: A state may revoke and reclaim land rights previously granted to a private entity if it is determined that the private management fails to serve the public interest or adapt to critical ecological needs.

SYLLABUS: In New Hampshire v. The Blue Mountain Forest Association, the State Supreme Court of New Hampshire reviewed the state’s decision to reverse a longstanding grant of property rights established by an 1898 statute (1898 N.H. LEXIS 26), which conferred the Blue Mountain Forest as a private game reserve managed exclusively by the Blue Mountain Forest Association. This century-old grant aimed to preserve the forest and its wildlife under private stewardship. However, contemporary environmental and financial conditions precipitated the state’s decision to reclaim the land. The state argued that due to the accelerating impacts of anthropogenic climate change, including record temperatures, biodiversity loss, and ineffective adaptation by the Association, the public interest demanded state intervention.

Additionally, it was demonstrated that the Association's financial strain impeded the maintenance of the forest, exacerbating ecological risks and reducing public benefit.

The Court, weighing public trust obligations and the necessity of robust environmental management, upheld the state's authority to reclaim the property. It was found that the state has a constitutional duty to ensure the sustainable stewardship of its natural resources, especially in the face of climate-induced changes. The decision rested on the principle that the original grant, while lawful and wellintentioned at the time, no longer aligned with current ecological and economic realities.

The ruling mandates the Blue Mountain Forest Association to transfer its assets and land rights to the State of New Hampshire. The decision emphasizes the state’s role as a steward, reaffirming its responsibility to adapt land use policies in response to pressing environmental concerns. The Court’s conclusion highlights a pivotal shift in prioritizing adaptive public land management over historical private property rights in order to safeguard natural resources for future generations.

1

January 2, 2031

Re: The Future Management of Corbin Park; the Blue Mountain Forest

Effective immediately, the holdings of the Blue Mountain Forest Association will no longer be subject to the directive of the park superintendent or any private ownership group. With the property now jointly held by the five towns [Plainfield, NH; Grantham, NH; Croydon, NH; Newport, NH; and Cornish, NH), as purchased and overseen by the State of New Hampshire, all management of and by the Blue Mountain Forest Association will be jointly coordinated by four publicly-run agencies:

I. The Department of Public Safety

II. The Department of the Interior

III. The Department of Planning

IV. The Department of Preservation

Each member town will elect four representatives to serve roles in the respective Management Departments. Each elected term will last four years, followed by reelection and new governance.

1.1

Just as the raw materiality of the park - loose stone and rough timber - lends itself to spatial exploration and historic precedent, the infrastructural legacy of the game preserve offers immediate locations for reinterpretation and renewal. The existing built environment of the Blue Mountain Forest is curated for a private client; it cannot presently support the aims of public experience. Hunting cabins, feeding stations, degraded gates, maintenance sheds and surveying equipment speak an unapologetic, utilitarian design language. Public interface necessitates physical engagement that is non-extractive - more than this, these touch points can facilitate regenerative processes. Poetic justice does not manifest in the form of retribution, but in coy reference and reuse of these hard elements.

Certain functions of Corbin Park are systemically entrenched. The Croydon Peak fire watchtower - the oldest of its kind in the nation - is Sullivan County’s sole fire monitoring station; it operates as a key node within regional systems of fire management. With rising global temperatures, poor silvicultural practices and drier vegetative conditions, this monitoring program cannot realistically cease to exist. There is a need now more than ever for both the suppression of wildfire and the conflagration of rampant growth. In either case, tactics of fire control remain necessary. The deep-rooted invasive ecology of the Park cannot be eradicated either, and requires the careful eye of wildlife biologists. Its animal species already breach the limits of their confinement, and will seek greater freedom amidst a climatically changing habitat. For now, the fence that contains this wild agency must not be taken for granted - it is a critical programmatic cog, a tool of both withholding and letting go.

Blue Mountain Holocene intersperses aesthetic experience amongst infrastructural need, juxtaposing mnemonic touch points and functional mechanisms. Here lies within a series of programmatic twins; built interventions which serve dual aims: access for an ousted public and stewardship for a hybrid landscape. These aims are introduced and mediated by the four proposed local agencies: the Department of Public Safety, the Department of the Interior, the Department of Planning, and the Department of Preservation - each a public committee consisting of elected officials from the five townships. These aims are not mutually exclusive, and collaboration between management departments is crucial. Questions of the interior and ecological stewardship directly impact notions of public safety and access. Preservation and planning necessitate one another; each explore avenues of infrastructural and mnemonic stewardship.

As a local effort and a bottom-up process, activism can parasitically subdue and reprogram this site. Through the exploitation of existing legal frameworks and the adaptive reuse of existing conditions, this rogue intervention seeks to infiltrate the unknown and find a careful footing. The formal language and representation of this project explore one technique of this reclamation: the reinterpretation of existing graphic tropes, of encyclopedic imperialism and dry municipal planning.

Parasitic Subversion

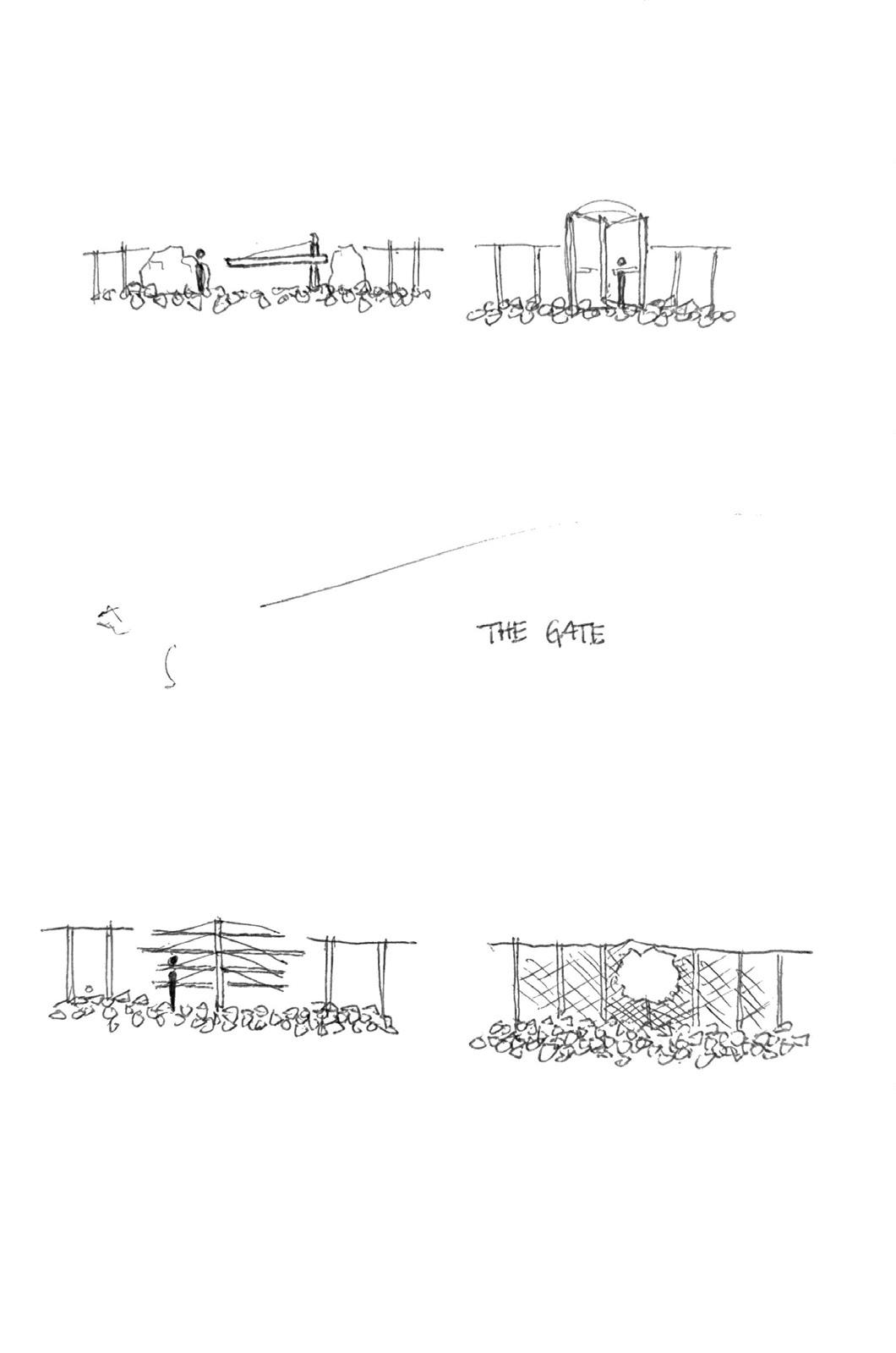

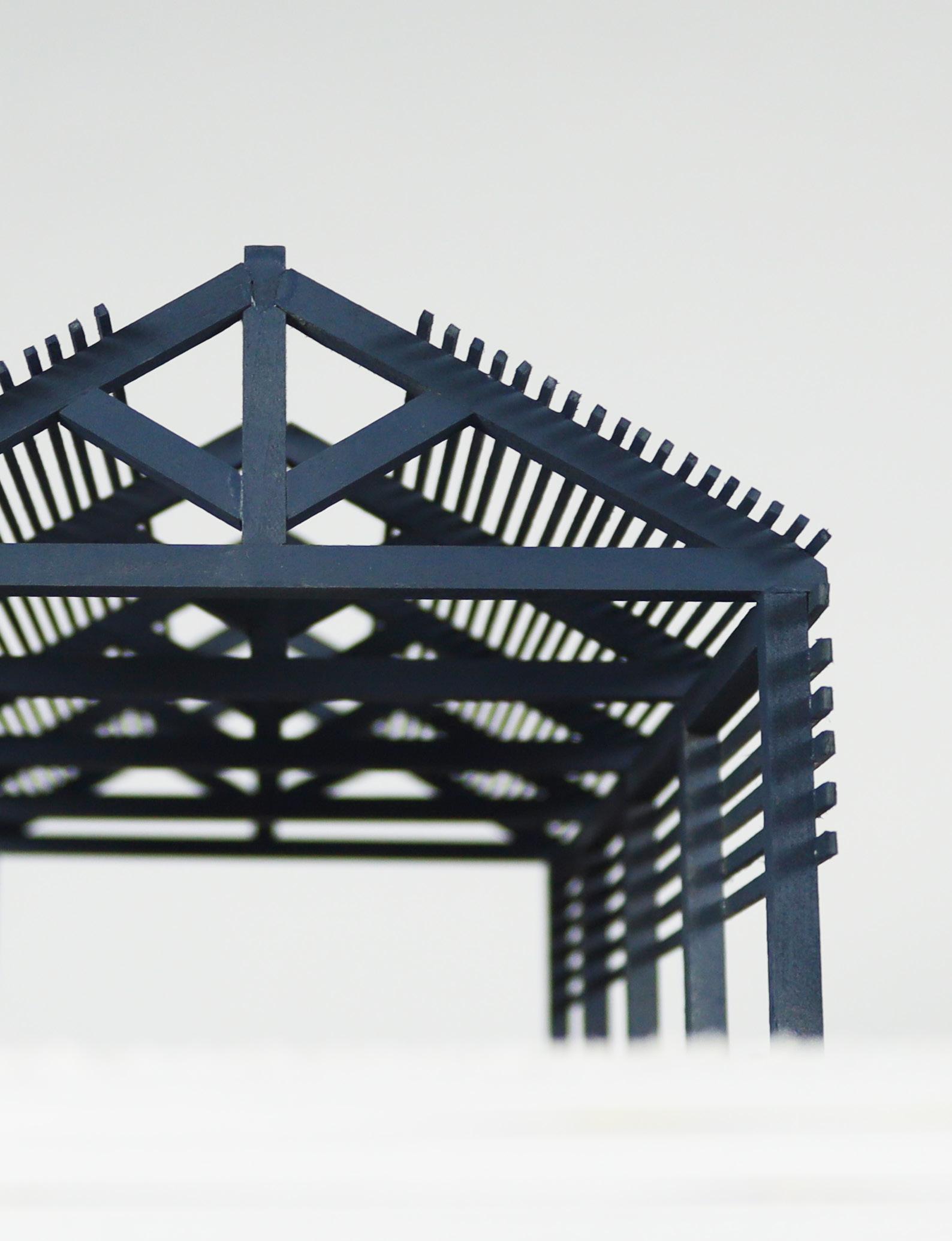

The Gate is a replicable prototype, sited at the locations of Corbin Park’s historic perimeter gates. In each case, two glacial erratics - massive boulders scattered across the site, the presence of which was witnessed firsthand near the perimeter - squash the fence line. A jagged cut is produced, and the typical latched gate is replaced with a freely swinging timber turnstile. The moment is celebrated; a monumental timber pergola frames each entrance point and renders them visible at distance. The Gate facilitates passage and protection.

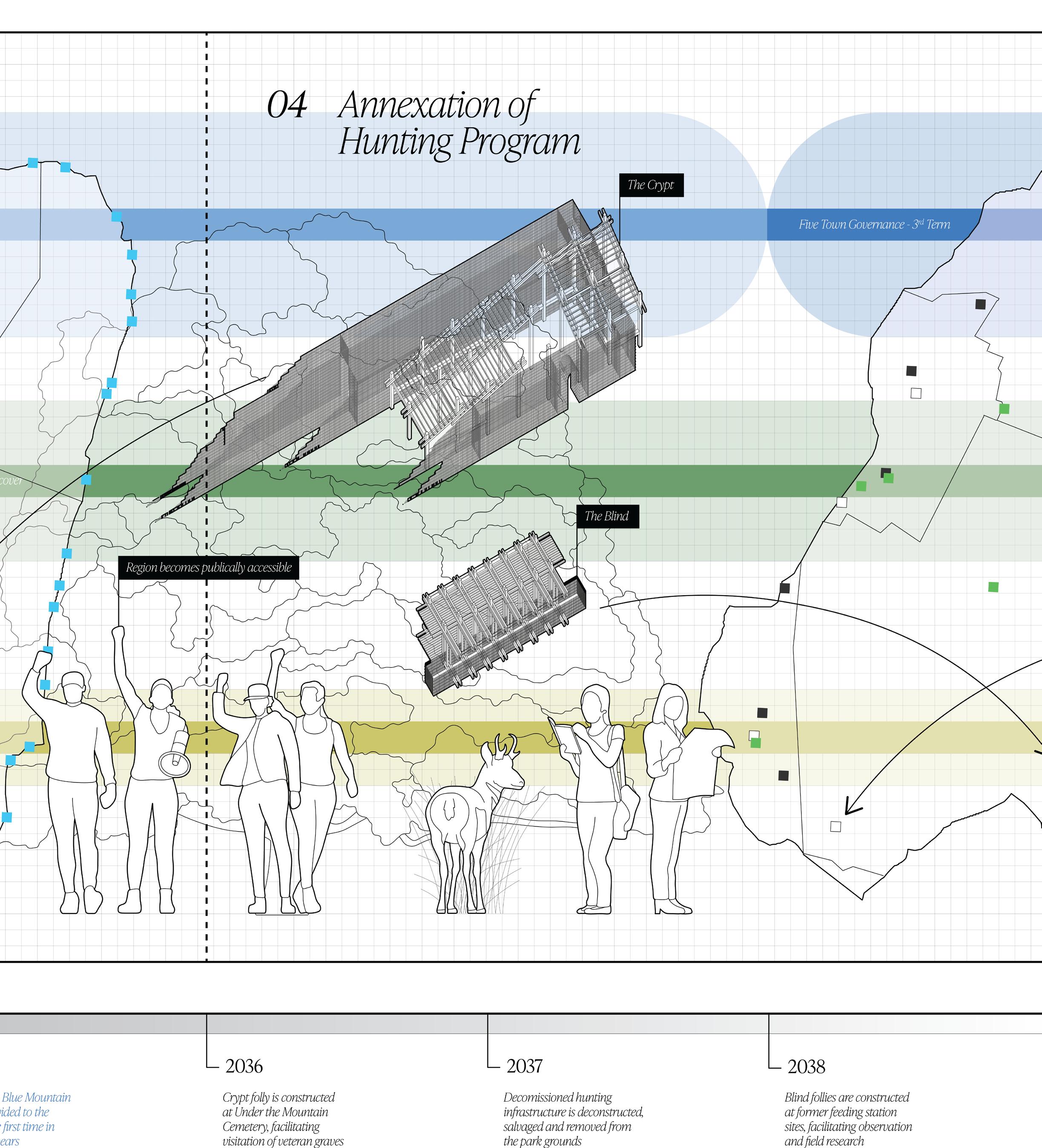

The Crypt is a singular intervention, sited near the entrance of the Under the Mountain Cemetery. This structure lies near to the graves of Revolutionary War veterans, themselves a site of pilgrimage - an annual tradition allows for the maintenance of these tombstones by local volunteers. An embedded gabion retaining wall holds back the earth, referencing typical winter receiving vaults. A lightweight timber frame and slate roof protect an altar and memorial, and houses stone cleaning equipment. The crypt facilitates visitation and remembrance.

The Shade is a replicable prototype, sited at the locations of existing hunting cabins. Many cabins obscure original stone ruins of settlement, and these residential structures lie near paths of travel. By peeling back these layers and inserting a shaded timber pavilion - a specter of the familiar ‘big house, little house, back house, barn’ residential typology - this network of retreats can serve as sites of rest for hiking and other recreation. The Shade facilitates respite and recovery.

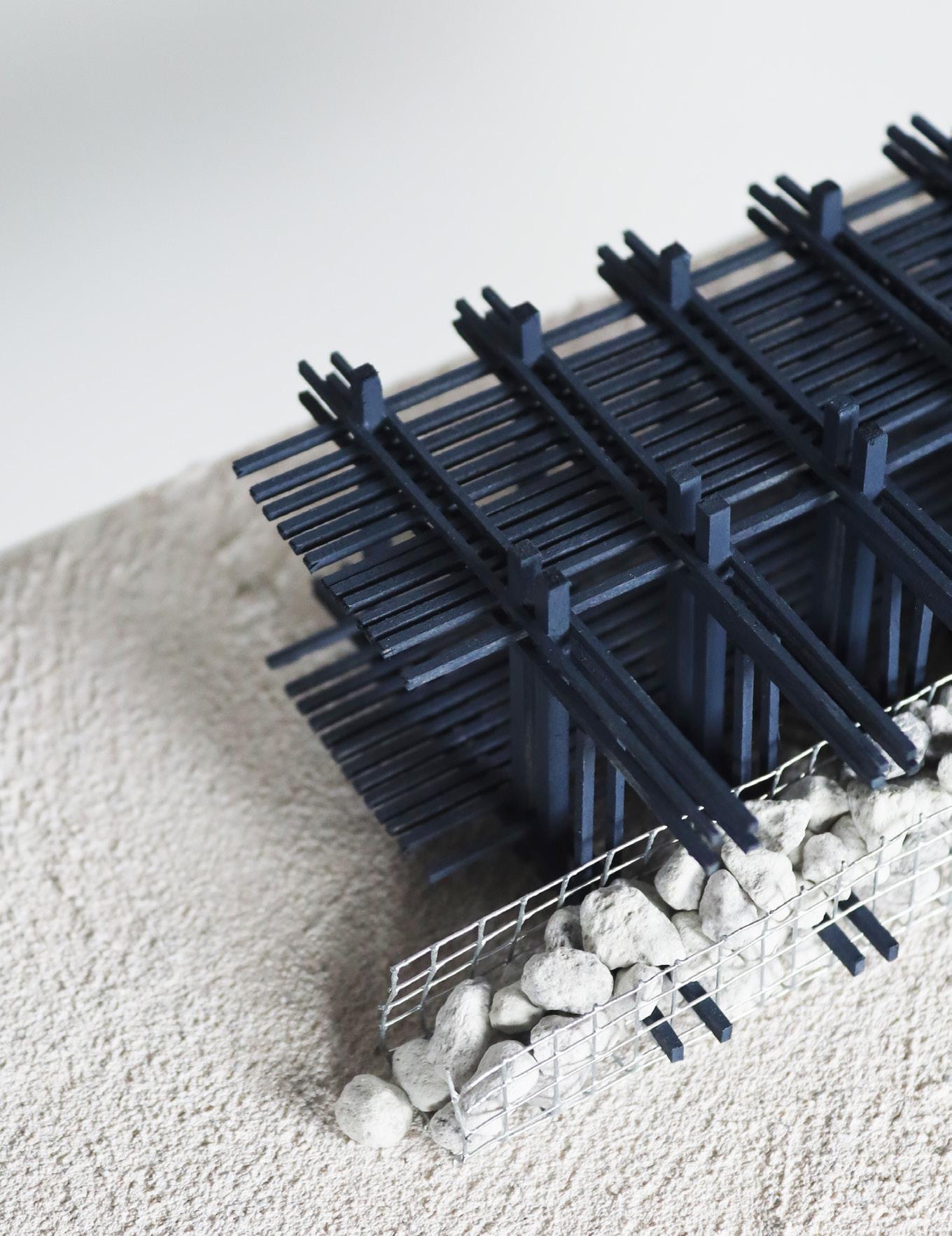

The Blind is a replicable prototype, sited at the locations of existing animal feeding stations. This timber plinth reinterprets the use of hunting blinds - objects of camouflage adjacent to food sources - and creates opportunity for the observation of wildlife. Users are obscured behind stone - the same technique used by local naturalist Ernest Baynes. This functionality lends itself to both casual enthusiasm and technical field research. The Blind facilitates viewing and camouflage.

The Lookout is a singular intervention, sited at the Croydon Peak fire watchtower. The cab of the existing structure is removed, and the cable-stayed steel tower is reinforced with a secondary timber frame to help frame a covered observation platform. For use by both the fire warden and the public, reclamation of this vantage point is paramount - both for understanding the regional geography and interfacing with collective memory. The Lookout facilitates detection and observation.

The Pyre is a replicable prototype, sited on a path along the Park’s highest ridgeline. The ground condition is exposed rock; laid bare by the 1953 Grantham Mountain fire. As a distant beacon and material marker, the burn scars of the Park viscerally represent the lost element of fire - eradicated through militant prevention. A loose gravel bed supports a timber plinth of stacked members. At the transept, a gabion anchor and steel cauldron provide safe containment for the ignition of brush and kindling. The Pyre facilitates burning and renewal.

Programmatic Twins

Pitchforks

I don’t know if I will ever physically enter the Blue Mountain Forest. After this journey, a part of me does not want to enter it, and another part of me believes I already have. This story, this place, constitutes a landscape both real and imagined. The Forest is made of graves and stories as much as wood and stone. I am a part of it now, too. I see the land from a distance, a backdrop while driving on the highway - dense vegetation and exposed bedrock. I see the ruins in my mind’s eye, just beyond reach yet effortlessly tangible. I believe the Park sees me too. It knew of my presence long before my own awareness of this land and its history.

The promise of the Blue Mountain Forest endures - no, resides - in the collective memory of the people it has touched. Like a beating heart, a reverberation of some wild force, this legacy ripples beyond the limits of its own confinement. Just as its own privatized stewardship has been passed down, the memory of this site as a public good has been discretely safeguarded and kept close. The commons has not yet been completely lost to subjugation by privatization - meaning the time for action is nigh. Cracks are showing in the perimeter infrastructure, and besides - it’s local tradition to cut holes in the fence.

The privatization of public lands is not a systemic answer, but a shortsighted mistake. Effective conservation - whether ecological or architectural - is not a reactionary, indulgent process, but a generational quandary. It requires collective engagement and adaptive leadership; two tenets antithetical to the curation and maintenance of static recreational landscapes like hunting reserves. So, raise your pitchforks: resist the closure of the commons, just as the Ellis did. Dismantle infrastructures of environmental imperialism, and replace them with interventions of access and sound science. Overlay digital process with mnemonic epistemologies, so that no stone is left unturned. Ask yourself: who really owns that mountain?

Fig. 35

12” x 30” x 21” The Gate timber frame, swivel function

Fig. 36

12” x 30” x 21” The Gate glacial erratic, bent timber

Fig. 37

18” x 24” x 30” The Shade heavy timber truss, light canopy

Fig. 38

18” x 24” x 30” The Shade stone ruin overlay

Fig. 39

8” x 24” x 27” The Blind gabion anchor, timber platform

Fig. 40

8” x 24” x 27” The Blind slatted floor and canopy

Fig. 41

12” x 12” x 36” The Lookout parasitic frame, adaptive reuse

Fig. 42

12” x 12” x 36” The Lookout timber viewing platform, shed roof

Fig. 43

12” x 12” x 33” The Pyre timber plinth, gravel bed

Fig. 44

12” x 12” x 33” The Pyre steel cauldron, kindling

9000 BCE

1700 BCE

1000 BCE

Timeline

First peoples came to New Hampshire over Siberian Ice Bridge (hunter; caribou)

Archaic period begins (hunter/gatherer; elk, deer, bison)

Abenaki begin four sacred plants agricultural practice

950-1250 CE Medieval warm period, warmer global temperatures

1450-1850

Neo-glacial climatic period, cooler global temperatures

1600 Woodland Abenaki culture begins (warmer weather; less nomadic)

1603

1614

First recorded European visitor, English mariner Martin Pring, sails up the Piscataqua River

English ship captain John Smith of Hampshire, England sails and maps the New England coast, writes to England about prospective land

1615-1620 ‘The Great Dying’ - Smallpox and influenza outbreaks decimate native populations; 90-95%

1623

1623

French offer bounties for Indian scalps

Under authority of an English land grant, Captain John Mason sends representatives to establish a fishing colony in present-day Rye, NH

1629 Colony is recharted as the Province of New Hampshire

1629 Initial land grant is expanded inland

1633

1675-1678

Second smallpox epidemic

King Phillip’s War fought between Abenaki and the English 1688-1697

1676

1676

King William’s War (1st intercolonial war) creates first largescale conflict between European settlers and the Abenaki

Maritime Indian Nations re-organize into the Wabanaki Confederacy (Major members: Abenaki, Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, Passimquoddy, Penobscot)

Major-General Richard Waldron invites 400 Wabanaki delegates to a peace conference in Dover NH; delegates are captured, hanged, and sold into slavery

1679 Community of towns is erected in southeastern NH, becomes “royal province”

1693

1702-1713

1713

1713

British and Abenaki sign the Treaty of Pemaquid, outlining conditions for peace and trade

Queen Anne’s War (2nd intercolonial war) fought between French and British over New England Territory

European nations sign the Peace of Utrecht and end the War of the Spanish Succession, creating peace between France and England that calms the North American theater

English representatives of Massachusetts and Abenaki leadership sign the Treaty of Portsmouth

1717 English settlement in Massachusetts expands northwards into Abenaki land, French resist + encourage Abenaki resistance

1721 Abenaki send letter to the Governor-General of New England demanding withdrawal, English respond by kidnapping the French Jesuit missionary Father Sebastian Rasles 1722-1725

Dummers War fought between English and Wabanaki Confederacy 1725-1726 Peace treaties signed in Maine and Nova Scotia 1725 Governors of NH, MA, and Nova Scotia agree to participate in the Boston Peace Conference

1741

1744-1748

New Hampshire separates from Massachusetts; Benning Wentworth appointed governor of the new colony

King George’s War (3rd intercolonial war) fought between English and French + Wabanaki Confederacy 1749

1753

The Crown commissions Wentworth to grant charters for thousands of acres of unimproved land

Town of Newport granted by Benning Wentworth 1756-1763

The French and Indian War (4th intercolonial war) is fought between English and French + Wabanaki Confederacy 1756-1759

Soldiers march north through the Connecticut River Valley, noting its abundance 1759

Marquis de Montcalm’s French troops are defeated on the Plains of Abraham outside Quebec City, leading the surrender of Quebec to the British 1759 Wentworth commissions Joseph Blanchard and Josiah Woodward to survey the Connecticut River Valley north of Charlestown 1761 First map of the region is engraved by Thomas Jefferys in London, ‘An Accurate Map of His Majesty’s Province of New Hampshire in New England’

1761

August 14: Town of Plainfield is chartered by Benning Wentworth 1761 Town of Grantham is incorporated by Benning Wentworth 1763

Town of Cornish is granted, incorporating “Mast Camp”; shipping point for river trade of lumber 1763

Town of Croydon is incorporated by Benning Wentworth 1765

Town of Plainfield is first settled 1766

March 17: First Plainfield Town meeting 1763

Town of Newport is first settled, French and Indian War delays settlement

1770

Benning Wentworth dies 1772 Baptist Pool sawmill is constructed 1775 New Hampshire ceases to exist as a Royal Province 1776-1778

Men from the NH grants are drafted into the Revolutionary War (Second Company of Rangers), march north to Fort Ticonderoga and Lake Champlain 1779 Voters of west Grantham join the members of east Plainfield to form a religious society due to church proximity 1780

A parish named “Meriden” is approved to serve this dual community

1790 Many remaining Abenaki migrate to Canada 1796 Locks and dam at Sumner Falls (Plainfield, NH) are chartered by Vermont

1809

William Jarvis of Weathersfield, VT, American Counsel to Portugal, obtains Spanish Merino breeding stock from nobles who need funds to defend against Napoleon Bonaparte’s armies 1810 Merino sheep are introduced to New England, making sheep farming the dominant agricultural industry, supplemented by oats, wheat, corn, and grain

1812 The Baker House is built, likely by Dimick Baker (1793-1876), who owned a 900-acre, 480-sheep farm along Blood’s Brook 1819 West Croydon is annexed to Cornish due to impasse of Croydon Mountain

1827

Austin Corbin II is born in Newport, NH 1829 1,150 sheep in Plainfield; first included in the tax inventory list (livestock, excluding chickens, was taxable property; descendants of original stock)

1830 1,169 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1835 10,432 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1840 11,205 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1844

A few farms in West Grantham are annexed to Cornish 1844 West Grantham residents petition NH General Court to allow annexation of their land to Plainfield, NH

1845 12,631 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1847

1849

Price of wool begins to decline

Austin Corbin II graduates Harvard Law School, returns to NH and begins practice

1850 Agriculture industry peaks, region is largely deforested

1850 10,337 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1850 End of the Neo-glacial period; global temperatures begin to increase

1850 Silsby Mill in Meriden established, eventually steam-powered; used to process lumber from the Park 1851

Austin Corbin II moves to Davenport, Iowa

1854 Corbin co-establishes Macklot & Corbin Bank, has success during ‘wildcat banking’ era pre-Civil War

1855 12,060 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1856 Western region of Grantham is annexed to Plainfield after initial resistance by both towns; Grantham is eager to shed the poor-value farmland

1856 Locks and dam at Sumner Falls are washed away 1856-1871 Brief revival of the woolen industry

1857 Panic of 1857, financial crisis caused by over-expansion and international economies; Corbin’s Bank is one of few to survive

1860 17,234 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1860-1900

Many NH residents begin to migrate to larger cities or western farmland, town populations decrease significantly 1861-1864

1861

Residents are mustered to serve in the New Hampshire Infantries during the Civil War

Onset of the Civil War creates surge in price of wool

1863 President Abraham Lincoln signs The National Bank Act into law, establishing national banks and government-backed currency

1863

Corbin organizes the First National Bank of Davenport, one of the earliest bank charters nationally and said to be the first to open

1865 13,817 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1865

1865

1867

Corbin moves to New York City, opens Austin Corbin & Company (later becomes Corbin Banking Company)

New Hampshire Fish and Game Department established; 1st in New England

Price of wool begins to decline 1867-1880

1868

Agricultural industry turns to dairy; sheep pastures are deserted and return to forestation

Ernest Harold Baynes is born in Calcutta, India

1870 9,110 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1870

Live sheep from the midwest are shipped east by rail in three days time, driving New England sheep prices lower 1872

1873-1876

1874

Austin Corbin III is born in New York City

Corbin secures 500 acres of Coney Island property titles, including 2.5 miles of contiguous ocean front property

Corbin founds the Manhattan Beach Improvement Co., a real estate venture improving and promoting Coney Island as a destination 1875 7,906 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1876

1877-1880

Corbin and his brother organize the Manhattan Beach Railroad Co. to deliver people to Coney Island

Corbin buys and consolidates the Long Island Railroad Co., other smaller operations

1880 7,952 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1880

Refrigerated cargo ships are introduced, enabling sheep imports from Australia, New Zealand, and Argentina

1885 6,920 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1886

1886-1896

1886

Austin Corbin moves back to New Hampshire, begins buying properties north of his family home

Corbin has carpenters selectively demo and replace his family home, building a mansion, barn, icehouse and buggy storehouse

Corbin acquires the Sunnyside Plantation in Arkansas; a former slave plantation; a repayment of a debt by John Calhoun II, grandson of the former Vice President

1888 South Plainfield is annexed to Cornish

1888 Corbin constructs a new covered bridge at the boundary of the Park; Corbin Bridge

1890 5,725 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1890 19 moose and elk are imported to the Park

1890 Refrigerated railcar shifts further center of meatpacking industry to the midwest

1891

Blue Mountain Forest Association is created by Austin Corbin II 1891 13 deer are imported to the Park

1891 200+ quail are imported to the Park

1892

1892

Austin Corbin purchases 10 bison from Buffalo Jones for $1000 each

6 boar hunting hounds are imported from Paris

1893 Additional moose and buffalo are imported to the Park

1893 Additional elk are imported to the Park; Corbin decides to kill off the boar to maintain order

1894

2 beavers are imported from Montana

1894 The Blue Mountain Forest opens to the public on Sundays, accessible by the Brighton, East Pass, and West Pass gates

1894 Corbin enters an agreement with the State of Arkansas to share profits from an inmate workforce to pick cotton, essentially slavery

1894-1895

Enters an agreement with the Mayor of Rome to recruit and redirect Italian peasants, sending them to Corbin Park and Sunnyside Plantation instead of New York City

1895 1,689 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1895 English red deer “and other animals” are imported to the Park from Europe

1895 Fox squirrels are imported from Kansas

1895

Blue Mountain Forest Association (BMFA) is incorporated in a ‘Special Act of the Legislature’ assigning full purview of game in Underchapter 152 of the General Laws

1895 BMFA holds largest private herd of buffalo in the U.S.

1896 Park opens to the public from June - October; Central Station open on Wednesdays

1896 Austin Corbin dies in a carriage accident inside the park

1896 Corbin’s will is filed; estate estimated at $40,000,000

1896 25 buffalo are exported from the Park to Van Cortland Park, NYC

1897 23 buffalo are returned to the Park by NYC

1897 1,200 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1898 75 buffalo in the Park

1898

Park opens to the public from June - October

1899 Large clubhouse is constructed at Central Station

1900 1,133 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1900 Less than 1,000 buffalo remain in the wild

1901

3 elk are exported from the Park to Chicago for an exhibition at the Sportsman’s Show

1902 President Teddy Roosevelt visits the Park and hunts

1903 Austin Corbin III enters an agreement with the State of NH to provide elk for repopulation outside the Park

1904 3 buffalo are exported from the Park to the National Zoological Park in Washington, D.C.

1904

1904

William T. Hornaday writes letter of recommendation to Austin Corbin in support of Ernest Baynes

Ernest and Louise Baynes move into “Sunset Ridge” homestead

1905 1,293 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1906

Last major flock of Plainfield, NH sheep is sold off

1906 Reuben Ellis of Croydon, NH, last holdout, sells his property to the Park with a provision to cut lumber on the land for five years

1907 Croydon Mountain fire watchtower and cabin are built in a joint venture between Corbin Park and the Draper Lumber Co., who had logging interests in the park

1907

First annual meeting of the newly-formed American Bison Society at the AMNH, Austin Corbin III is present

1908 Phone line is installed at the fire watch tower

1908 165 buffalo in the park

1908 3 buffalo are exported from the Park to start the Montana National Bison Reserve

1910 758 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1910 30 buffalo are exported from the Park to ‘Pawnee Bill’ in Oklahoma

1910-1925 University of New Hampshire Extension Services begins to advise farmers with recommendations based on infant soil fertility science

1911 Electricity is available in Plainfield, NH

1911 Buffalo are exported from the Park to South America

1911 Buffalo, elk and deer are exported from the Park to Pennsylvania

1914 600 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1915 621 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1915 State of NH passes a law requiring repayment for agricultural dam age caused by game

1915 “Greatest drive” of logs down the Connecticut River run by the Connecticut Valley Lumber Company, started at Second Connecticut Lake

1916

25 deer are exported from the Park to the Pennsylvania State Game Reserve in Jameson City via American Express

1917 6 buffalo are exported from the Park to Honiny, North Carolina as a gift to the Pisgah National Forest and Game Preserve

1917 45 deer are exported from the Park to Buffalo, New York

1917 The Park opens to the public June - October

1917 United States enters World War I

1917-1920

The Newport Winter Carnival is held in the Park, with a snowshoed deer drive, skiing and hockey

1918 End of World War I

1919 Buffalo are exported from the Park to Boston; destination un known

1920 328 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1921 2 buffalo are exported from the Park to Granlock, New Jersey

1925 306 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1925 Ernest Baynes dies in Meriden, NH

1925 Baptist Pool sawmill ceases operation

1926 Electricity is available in Cornish, NH

1929 The first airfield in the region is created on the Corbin family estate, originally called Austin Corbin Airport, Inc.; later changed to Albert N. Parlin Field

1930 328 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1935 333 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1935 National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) is founded as the Soil Conservation Service (SCS), emerging as a conservation re source for private lands

1938 Austin Corbin III dies

1938 Hurricane travels up the Atlantic coast with 80-125mph winds, causes extensive damage to park fence

1938 Majority of remaining farmers turn to dairy

1938-1958 Forested hunting “virtually impossible” due to deadfall

1939 Parlin Field purchases the airport land it had been leasing from the Corbin estate

1940 207 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1941 United States enters World War II

1941 Large herds of elk are seen in towns across the state

1941 Two-day statewide elk hunting season is created to control wild population of reintroduced and escaped elk; 46 elk are killed

1944 Controlling Interest of the Park is sold to an investment group led by Mortimer Proctor, Republican gubernatorial candidate of Vermont

1945 End of World War II

1945 Plainfield, NH approves a $40 bounty for each boar shot outside the Park

1945 Last buffalo is hunted after 18 months of eluding capture

1945 204 sheep in Plainfield, NH

A Membership system is formalized; had large facilitated invited guests

1949 NH legislature passes a special law holding BMFA liable for damage caused by escaped boar

1950 183 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1950-1951 “Operation Wild Hog” airlifts 30 tons of whole kernel corn to boar feeding grounds

1953 State legislature passes ‘An Act Relative to Elk’ (Chapter 43) to thin herds

1953 Lightning strikes in the park, sparking a large forest fire that burns much of Grantham and Croydon Mountains; burns June to November when the first snow flies

1955 State directs the Director of Fish and Game to reduce the herds to a level that will not threaten agricultural interests

1955 Conservation officers and an irate farmer kill 18 elk, leaving an estimated 20-30 roaming free (believed to have since been poached)

1955 Massachusetts sanitation laws change milk can system to a bulk tank system, enabling further shipping and ultimately damaging the New England dairy industry with competition from New York and Pennsylvania

1955 208 sheep in Plainfield, NHA

1960 206 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1964-1965

Drought in Claremont, NH; Corbin Park allows the city to “virtually empty two of its ponds” at no cost

1965 194 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1970 147 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1971

Taxation of sheep ends

1975 305 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1975 Plainfield, Cornish and Croydon refuse to grant the Park a property-tax abatement under ‘current use’ program (alleviating taxes for agricultural and forest land); Park sues and wins abatement

1980 170 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1985 106 sheep in Plainfield, NH

1988 William Ruger Jr., owner, partially renovates the Corbin estate house at an estimated cost of $450,000

1993 Corbin Bridge burns by arson

1994

The bridge is rebuilt and pulled by oxen across the Sugar River, but removed from the National Register of Historic Places

1995 Joseph Laurent completes first English translation of ‘Father Aubery’s French Abenaki Dictionary’

1998 Rex Miller is born in Lebanon, NH; grows up in Plainfield

2004

Steve Laro shoots and kills Robert Proulx, a member of his hunting party, thinking it’s a boar

2004 Steve Laro is charged with and acquitted of negligent homicide and felonious use of a firearm

2005 Steve Laro’s hunting license is revoked by NH Fish and Game, but his attorney appeals, arguing that he was hunting boar essentially outside of their jurisdiction

2011

Plainfield Volunteer Fire Department responds to a fire call of a burning vehicle inside the Park; while inside see a newly-built clubhouse

2011 Plainfield town assessor inspects and updates the tax data for the Park property within the town

2012 Vermont Governor Peter Shumlin signs into law state recognition for the Abenaki, including partial recognition

2024 Rex Miller creates Blue Mountain Holocene

2025 The Supreme Court of the State of New Hampshire rules that the basis of climate change and impending financial losses in the tourism sector provide grounds to reverse the 1898 Special Act of Legislature

2026 Terms of sale are agreed upon between the park ownership, the state, and an independent arbitrator

2027 Acquisition is foralized; all current club members are individually compensated for their respective shares of ownership

2028 Transition group is formed as a collaboration between the Park Superintendent, representatives of the five towns, and a state mediator

2029 Park operations are jointly discontinued, retaining maintenance of critical operations and employment

2030 The property holdings of the Blue Mountain Forest Association are legally transferred to the five town governments

2031 Collective governance is implemented through the establishment of elected roles and four management departments

2032 Management board begins schedule of annual public hearings, with referendums on questions of stewardship

2033 Construction of follies at coordinates of historic access gates commences; barbed wire is removed

2034 Fire watchtower is renovated to include public viewing folly; fire risk of the park is assessed and coordinated

2035 Access to the Blue Mountain Forest is provided to the public for the first time in almost 100 years

2036 Crypt folly is constructed at Under the Mountain cemetery, facilitating visitation of veteran graves and education

2037 Decommissioned hunting infrastructure is deconstructed, salvaged and removed from the park grounds

2038 Blind follies are constructed at former feeding station sites, facilitating observation and field research

2039 Shade follies are constructed at hunting camps and stone ruins, providing respite for hikers in the form of pavilions

2040 Pyre follies are constructed at the site of the wildfire; serving as beacons and facilitating interface with fire

2044 Tree survey of park completed to evaluate health, species distribution, and fire risk

2048 Undergrowth is managed through controlled burns and cutting, protecting old growth and biodiversity

2052 Animal species are studied through network of wildlife blinds; field research performed to evaluate individual risk

2056 Recommendations of wildlife biologists are incorporated to strengthen conditions for native and at-risk species

2060* Tract of perimeter fence between Plainfield and Grantham is removed; approximately 20% of total length

2064* Tract of perimeter fence between Cornish and Newport is removed; approximately 40% of total length

2068* Tract of perimeter fence between Croydon and Grantham is removed; approximately 60% of total length

2072* Tract of perimeter fence between Plainfield and Cornish is removed; approximately 80% of total length

2076* Tract of perimeter fence between Croydon and Newport is removed; 100% of total length

* Sliding target; phasing based on future ecological data

Bibliography

History of Corbin Park:

1 All About Bison. “Austin Corbin Park.” Accessed September 15, 2024. https:// allaboutbison.com/bison-in-history/austin-corbin-park/

2 August Longpré. “A Comprehensive History of Corbin Park.” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://augustlongpre.substack.com/p/corbin-park-his tory

3 Baynes, Ernest Harold. War Whoop and Tomahawk. The MacMillan Company, 1929.

4 Baynes, Ernest Harold. Wild Life in the Blue Mountain Forest. The MacMillan Company, 1931.

5 Billin, Dan. “Private Game Preserve Has Storied History.” Valley News, January 28, 2004. http://www.meyette.us/DanBillinCorbinParkArticle.htm

6 Comeau-Kronenwetter, Mary. “Elk in Corbin Park.” SooNipi Magazine (Fall 2007). http://www.meyette.us/CorbinElk.htm

7 Corbin Park. “Corbin Park Timeline.” Accessed September 15, 2024. http://www. meyette.us/CorbinParkTimeline.htm

8 Corbin Park. “Corbin Park.” Accessed September 15, 2024. http://www.meyette.us/ CorbinPark.htm

9 Evans-Brown, Sam, host. Outside/In. Episode 27, “Millionaires’ Hunt Club.” Outside/In Radio, December 29, 2016. Podcast, 23 minutes, 47 seconds. http://outsideinradio.org/shows/ep27

10 Jenney, William Henry. Blue Mountain Bill: Stories of Corbin’s Park from a Wildlife Guide and Caretaker. AuthorHouse, 2015.

History of New England:

11 Blanchard, Joseph, Samuel Langdon, and Thomas Jefferys. An Accurate Map of His Majesty’s Province of New-Hampshire in New England, 1761, 73cm x 69 cm, Washington D.C. Portsmouth, N.H., 1761.

12 Holl, Steven. “Rural & Urban House Types In North America.” Pamphlet Architecture no. 9 (December 1982): 5-58 https://moodle2.units.it/ pluginfile.php/305293/mod_resource/content/0/hollhousetypes.pdf

13 Mi’kmaw Spirit. “Mi’kmaw History - Post-Contact Timeline.” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.muiniskw.org/pgHistory2.htm

15 New England Historical Society. “The Birds’ Best Friend: How Ernest Baynes Saved The Animals.” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://newenglandhis toricalsociety.com/new-england-birds-best-friend-ernest-baynes-savedbirds-bison/

16 New Hampshire Stone Wall Mapping Project. “NH Stone Wall Mapper.” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://new-hampshire-stone-wall-mapping-projectnhdes.hub.arcgis.com/

17 NH.gov. “A Brief History of New Hampshire, New Hampshire Almanac.” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.nh.gov/almanac/history.htm

18 NH.gov. “Native American Heritage.” New Hampshire Folk Life. Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.nh.gov/folklife/learning-center/ traditions/native-american.htm

19 Picard, Ken. “What Are Those Stone Caves in Many Vermont Cemeteries?” Seven Days, October 28 2020. https://www.sevendaysvt.com/arts-culture/ what-are-those-stone-caves-in-many-vermont-cemeteries-31528778

20 Plainfield Historical Society. “Maps.” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www. phsnh.org/maps

21 Portsmouth Peace Treaty of 1713. “The Treaty of Portsmouth.” Accessed September 15, 2024. http://www.1713treatyofportsmouth.com/

22 Zea, Philip, and Nancy Norwalk, eds., Choice White Pines and Good Land: A History of Plainfield and Meriden, NH. Peter E. Randall Publisher, 1991.

Climate + Ecology:

23 Baron, William R.. “Eighteenth-Century New England Climate Variation and its Suggested Impact on Society.” Maine History 21, no. 4 (1982): 201-218 https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistoryjournal/vol21/ iss4/3

24 Donlan, C. Josh, Joel Berger, Carl E. Bock, et al. “Pleistocene Rewilding: An Optimistic Agenda for Twenty-First Century Conservation.” The American Naturalist 168, no. 5 (November 2006): 660-681. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/17080364/

25 Gable, Thomas D., Sean M. Johnson-Bice, Austin T. Homkes, John Fieberg, and Joseph K. Bump. “Wolves Alter the Trajectory of Forests by Shaping the Central Place Foraging Behaviour of an Ecosystem Engineer.” Proceed ings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences 290, no. 2010 (November 8, 2023). https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2023.1377.

26 Gable, Thomas D., Sean M. Johnson-Bice, Austin T. Homkes, Steve K. Windels, and Joseph K. Bump. “Outsizfed Effect of Predation: Wolves Alter Wetland Creation and Recolonization by Killing Ecosystem Engineers.” Science Advances 6, no. 46 (November 13, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1126/ sciadv.abc5439.

27 Nash, Roderick Frazier. Wilderness and the American Mind, Fifth Edition. Yale University Press, 2014.

28 Rubenstein, Dustin R., and John Alcock. Animal Behavior, Eleventh Edition. Oxford University Press, 2019.

29 Thorne, Sarah, and Dan Sundquist. “New Hampshire’s Vanishing Forests: Conversion, Fragmentation and Parcelization of Forests in the Granite State.” Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests (April 2001). https://www.forestsociety.org/document/new-hampshires-vanishing-for ests-society-protection-pdf.pdf

Legal Standing of Hunting Reserves:

30 Cause IQ. “Blue Mountain Forest Association | Newport, NH | Cause IQ.” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.causeiq.com/organizations/blue-mountainforest-association,020110580/.

31 Citizens Count. “Should private hunting preserves pay more taxes if they keep invasive species?” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://www.citizenscount. org/news/should-private-hunting-preserves-paymore-taxes-if-they-keep-invasive-species

32 Justia Law. “King V. Blue Mountain Forest Association,” Accessed September 15, 2024. https://law.justia.com/cases/new-hampshire/su preme-court/1956/4457-0.html.

33 Suozzo, Andrea, Alec Glassford, Ash Ngu, and Brandon Roberts. “Blue Mountain Forest Association - Nonprofit Explorer.” ProPublica, May 9, 2013. https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/20110580.

34 WildEarth Guardians. “Public Lands Grabs.” Accessed December 18, 2024. https:// wildearthguardians.org/public-lands/public-lands-in-public-hands/privatiza tion-public-lands/

35 United States Department of Agriculture, Forest Service. Standard Lookout Structure Plans, 1938, 24in x 36in, digital download.

Field Notes