Spring 2022

Issue 12

Science & Society

Executive Board Editor-in-Chief

Dear Human,

Sarah Auletta

Managing Editor Alyssa Cameron Design Manager Elena Stratoberdha Website Coordi., Dan Nguyen Treasurer Student Govt. Representative

Letter from the Editor

Sarina Lau

Faculty Advisor Eric Luth

Contributing Staff Writers Sarah Auletta Alyssa Cameron Emily Douglas Sarina Lau A. Lizeth Campuzano Martínez Aamnah Nazir Eliot Stanton Copy Editors Maame Andoh Sarah Auletta Sarina Lau Cressida Michaloski Charlotte Peace Kiki Regan Designers Kiki Regan Printing Copy/Mail Center, Simmons University 300 Fenway Boston, MA 02115

What a year (or 8-9 months in academia).I honestly am not sure how we got here but somehow we did and for that I am grateful.When we were first brainstorming themes for this year’s magazine I was getting input from every direction and some people wanted hard science, some soft science, and some to repeat the pandemic theme. None of it felt quite right. I’m not sure how exactly we landed on “Science and Society” but I can exactly tell you the intention. We wanted something that encapsulated what the sciences (hard and soft) at Simmons represent: humanity. And not the gushy we care for each other sing kumbaya sort of humanity, but the ability to see everything we do in the context of the human race and the impact it will have on others. We want to appeal to the humanity of it all and see the bigger picture.There is a person behind every idea, action, failure, and success and that is what we hope this issue of MindScope presents. The faces of science are us and you, together, making the labs come to life and the surveys tangible. With all of that said, I hope you feel spoken to and represented in the following pages as I know all of us who have worked on it feel we have left our mark on these pages. All the best,

Sarah Auletta Editor-in-Chief

Table of Contents Taking Up Space in STEM Education,

1

A. Lizeth Campuzano Martínez

Here Is What You Need to Know About the Novavax Vaccine, 3 Aamnah Nazir

Tissue Engineering: A Biological Art Form,

5

Sarina Lau

Presentation: Ethics in Research,

10

Sarah Auletta

Measuring (Trans)gender in Demographic Survey Research, 14 Eliot Stanton

Using Coccolithophorid Algae to Combat the Climate Crisis,

19

Emily Douglas

The Power of Accepting Unpleasant Emotions, Alyssa Cameron

23

Taking Up Space in STEM Education by A. Lizeth Campuzano Martínez, Computer Science Major, 2025

N

ot only are women-identifying individuals less likely to be represented in the STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) workforce, but they also may struggle to overcome gender gap obstacles that continue after graduation, such as earning less than their male counterparts. A lot of ink has been spilled on these topics, but this article will explore how the gap of STEM workers starts with the way education shapes students to pursue their passions. From Ada Lovelace to Dr. Loretta Ford, women “not being designed for STEM” is simply not a relevant argument to explain the lack of support for women pursuing these majors. One of the truths I found while researching women in science was that no nurse has ever won a Nobel Prize. While nursing sciences differ from the recognized Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, nursing is perceived as a “profession deeply embedded in the gender-based power relations of society” (Neriman Akansel, 2022, para. 3).Therefore, not having an equally praised award highlights a difference in the way culture impacts these careers. Further illustrating this difference, as of 2021, “since its inception, 601 men and 23 women have received PCM (Physics, Chemistry, and Medicine) awards. This accounts for merely 3.69% women of all Nobel Laureates in 120 years” (Vijendra Agarwal, 2020, para. 8). While this example refers to a widely known prize, it is a great reference to the general cultural and academic support women must hold to succeed in the field. As a woman now pursuing a Computer Science major, I was consistently told I wouldn’t enjoy the courses or that I really didn’t like the science part of the field, but instead the “visual aesthetic” of designing an app or website. Even computers were typically “marketed almost exclusively to men, and families were more likely to buy computers for boys than girls” (NPR, 2010). I think this is a common experience that minorities in STEM fields share and may be rooted in how education systems cater their sciences content. So, we have the data. Now what can we do about it? First, talk about women and non-binary individuals succeeding in STEM fields! Recognize their work in

1

Taking Up Space in STEM Education

Women made gains – from eight percent of STEM workers in 1970 to 27% in 2019 – but men still dominated the field. Men made up 52% of all U.S. workers but 73% of all STEM workers. (U.S. Census Bureau, 2021, para. 2)

the things we use every day, like Dr. Shirley Ann Jackson, whose research is responsible for the caller ID and call waiting functions in our phones. There are many women who were never fully recognized for their developments, and finding someone you can relate to is motivating. Second, drop the pressure and competition to be the “first.” Women being the first to achieve something in their field is what makes news headlines. However, society adds an element of competition, a metaphorical race to be the first to make it in one’s field, rather than open the way for more women to share an accomplishment. Susan Stamberg, the first woman to anchor a national nightly news program, stated “to be the first, you’re standing in for everyone. And so, you have to do it not just as well as you can, but better than anybody else, better than any of the big guys because Photograph of Susan Stamberg. it’s up to you, and you’ve got to sort of carrying that flag Courtesy of NPR. for the gender, essentially” (NPR, 2010). Lastly, take up space in discussions outside or in the classroom! Construct a culture of inspiring others to pursue a STEM career and making it more accessible. Dr. Katie Pollard for Gladstone Institutes mentioned the importance of “forming groups, committees, and efforts—very successful ones too—to bring our community together and to advocate for the things we need” (Vazquez, 2020, para. 24). Even starting by forming study groups and not struggling by yourself while learning is useful!

References 1. 2.

3. 4. 5. 6. 7.

Agarwal,V. (2020, December 8). Women Nobel Laureates:What has changed in 120 years? The Scientista Foundation. http:// www.scientistafoundation.com/women-in-science-news/women-nobel-laureates-what-has-changed-in-120-years. Akansel, N. (2022). Gender and career: Female and male nursing students’ perceptions of male nursing role in turkey. Health Science Journal, 2(3). https://www.hsj.gr/medicine/gender-and-career-female-and-male-nursing-students-perceptions-ofmale-nursing-role-in-turkey.php?aid=3661. BBC News. (2017, September 4). BBC 100 Women: Nine things you didn’t know were invented by women. https://www.bbc. com/news/world-40923649. Computer Science.org Staff. (2020, October 15).Women in Computer Science. Computer Science Organization. https:// www.computerscience.org/resources/women-in-computer-science/. NPR (2010, March 16). ‘First Women’ Open Doors For Future Generations. https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story. php?storyId=124737770. U.S. Census Bureau. (2021, January 26). Women Are Nearly Half of U.S. Workforce but Only 27% of STEM Workers. https:// www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/01/women-making-gains-in-stem-occupations-but-still-underrepresented.html. Vazquez, A. (2020, October 12). Strong Women in STEM: A Conversation with Katie Pollard. Gladstone.org. https://gladstone. org/news/strong-women-stem-conversation-katie-pollard.

Taking Up Space in STEM Education

2

Here is What You Need to Know About the Novavax Vaccine by Aamnah Nazir, Biology Major, 2024

N

ovavax, also known as NVX-CoV2373, is a protein-based vaccine designed from the genetic sequence of the first strain of SARS-CoV-2. After the genetic code of COVID-19 was sequenced in January 2020, Novavax, a biotechnology firm, began creating a vaccine. The basic technology behind the Novavax vaccine is similar to that of the vaccines for hepatitis B and whooping cough (Satherly, 2022). However, the vaccine technology for the Pfizer and Moderna vaccine is mRNA based. University of California Berkeley’s head of infectious diseases, Lee Riley, states that “protein-subunit vaccines are considered the safest form of vaccines, based on a widely used technology” (Satherly, 2022, para. 13). The Novavax vaccine is recommended to people 18 years and older by the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunization and is administered in two doses, three weeks apart (Willis, 2022). The clinical trials of the Novavax vaccine generally had promising results, with an overall efficacy of 90 percent against mild, moderate and severe diseases in the two phase 3 trials (World Health Organization, 2021). In its clinical trials, the Novavax vaccine seemed to cause less mild-to-moderate side effects than Pfizer or Moderna. An important note to make as we have discovered in the administration of the Pfizer, Moderna, and Janssen vaccines is that some more serious side effects are rare and do not appear until millions of people receive the vaccine. Currently, the known side effects of the Novavax vaccine are common in most vaccines and can include tiredness, headaches, and muscle pain (Australian Government Department of Health, 2021). Novavax later conducted trials in adolescents aged 12 to 17 and recently announced the results in February 2022 with an efficacy against infection of 80 percent. However, the vaccine is not currently available for adolescent use (Geddes, 2022). There are many advantages to a protein based vaccine as opposed to mRNA vaccines, which some are hesitant about. Having a vaccine that is made up of more traditional technology like Novavax can be more convincing for those who choose not to get an mRNA based vaccine.Those who react more severely to the Pfizer vaccine might benefit from the Novavax vaccine as an alternative.

3

Here is What You Need to Know About the Novavax Vaccine

Novavax later conducted trials in adolescents aged 12 to 17 and recently announced the results in February 2022 with an efficacy against infection of 80 percent. However the vaccine is not currently available for adolescent use (Geddes, 2022).

Photo courtesy of Getty Images. The Novavax vaccine is also easier to store and transfer as it does not require specialized ultra-cold freezers and can be stored in regular fridge temperatures (Satherly, 2022). For use in the U.S., Novavax has officially filed for approval with the FDA. So why hasn’t the Novavax vaccine been administered and distributed to the U.S.? The main difference between the Novavax vaccine and the three vaccines currently being administered in the U.S. is the timing of their rollout. The authorization of these three vaccines for emergency use means that there is no urgency in the Novavax vaccine becoming available in the U.S. This will be true for some time as other vaccines, such as Pfizer, will continue to be in high demand. However, there are many countries that have authorized the use of the Novavax vaccine for emergency use, the first being Indonesia and the Philippines in November, 2021 and, most recently, Australia and the UK as of February 2022 (World Health Organization, 2021).

References 1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Australian Government Department of Health. (2022, February 28). Nuvaxovid (novavax). Australian Government Department of Health. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://www.health.gov.au/ initiatives-and-programs/covid-19-vaccines/approved-vaccines/novavax. Geddes, Linda. (2022, February 14). What is the novavax vaccine, and why does the world need another type of COVID-19 vaccine? Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Retrieved March 13, 2022, from https://www.gavi. org/vaccineswork/what-novavax-vaccine-and-why-does-world-need-another-type-covid-19-vaccine. Satherley, D. (2022, March 9). Covid-19: Everything you need to know about the novavax vaccine. NewsHub. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://www.newshub.co.nz/home/new-zealand/2022/03/ covid-19-everything-you-need-to-know-about-the-novavax-vaccine.html. Willis, O. (2022, February 15). Novavax is now available in Australia. Who can get it, and how much protection does it provide? ABC News. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://www.abc.net.au/news/ health/2022-02-15/novavax-covid-19-vaccine-what-we-know/100828062. World Health Organization. (2021, December 21). The novavax vaccine against COVID-19: What you need to know. World Health Organization. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://www.who.int/ news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-novavax-vaccine-against-covid-19-what-you-need-to-know.

Here is What You Need to Know About the Novavax Vaccine

4

Tissue Engineering: A Biological Art Form by Sarina Lau, Chemistry Major, 2024 What is it?

T

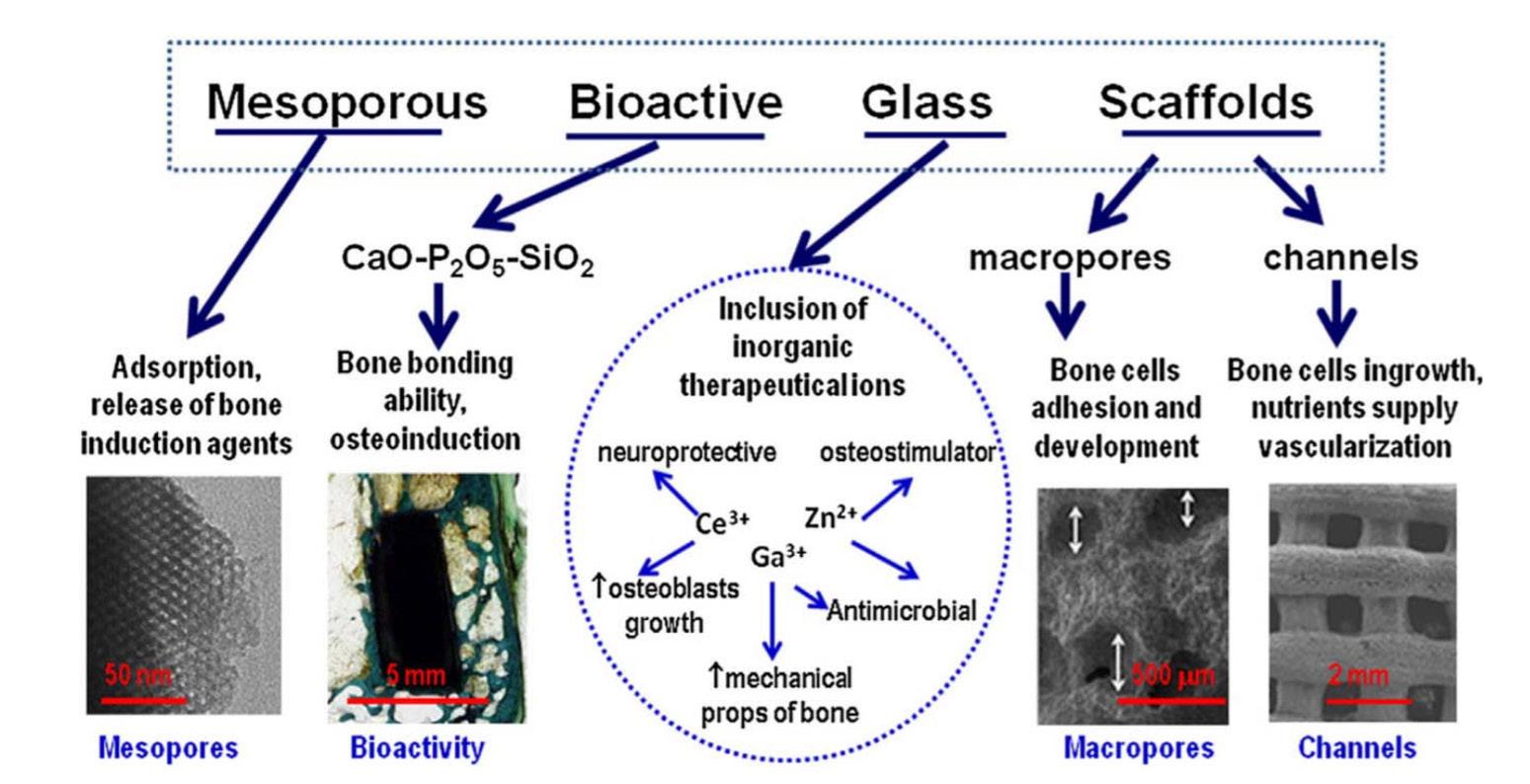

he emerging field of tissue engineering has many possible applications within the human biological system, but it is hardly ever discussed as a form of art. Regeneration of tissue for the purposes of repairing damaged systems within the body “as a result of trauma, injury, disease, or aging” is in itself a beautiful and powerful form of art (Rahaman, 2011). In the past two decades, there have been tremendous strides in research despite the field of tissue engineering originating in the late 1980s (Jones, 2008). During the beginning stages of development in this field, the first bioactive glass device was developed for the purpose of treating conductive hearing loss by replacing the ossicle bones of the middle ear (Jones, 2008). Research involving bioactive glass has discovered the benefits of using this material since it contains sodium and calcium as well as the ability to release the calcium into the circulatory system to produce hydroxyapatite (HA). HA, an important component of human bone, has the potential to be extremely useful in the development of new bone within the human body making bioactive glass a growing field in materials science (Grayson, 2017). Figure 1. Diagram depicting the numerous characteristics of bioactive glass material for tissue regeneration and their ability to bond with human bone. Photo courtesy of Mo-Sci Corporation.

5

Tissue Engineering: A Biological Art Form

The future of tissue engineering: where is current research taking us? Current research within this field has advanced significantly, including the implementation of borosilicate, boron, and other types of bioactive glass for tissue regeneration due to adjustable degradation rates in comparison to silicates (Rahaman, 2011). In the upcoming summer, I plan to study and synthesize these bioactive glasses at Rutgers University and establish their composition-structureproperty relationships useful for the development of a new method in soft tissue engineering.

Bioethics and society A substantial step towards making medical and scientific advancements is educating the population for which these advancements are made. More specifically, why do we care about tissue engineering? Many examples — including organ transplantation — already exist. Research within tissue engineering aims to promote a longer lifespan, lower healthcare bills overall, decrease morbidity, and minimize ethical issues related to medical treatment including ethical issues surrounding organ transplantation (Ko, 2006, p. 2). Progression within this field will be helpful during this current time period as human life expectancy increases and people are more at risk of developing health complications and diseases. The increasing risk of health issues gives researchers and engineers a higher expectation of the “efficacy and quality of medical treatment” that are “inherent in the high-tech society” (Ko, 2006, p. 2). Tissue engineering tackles these higher expectations while addressing the challenges of organ transplants. Some of these issues include having to be placed on a waitlist for organ transplants and the extreme medical expenses that come with these procedures.

Progression within this field will be helpful during this current time period as human life expectancy increases and people are more at risk of developing health complications and diseases.

Many ethical issues come with the use of organ transplants including the use of animal organs, or xenotransplantation, and the use of deceased human donors, or allotransplantation. There are also ethical questions regarding the use of extracorporeal devices including dialysis machines and implantable devices (Ko, 2006, p. 4). Using tissue engineering, researchers can “draw upon our own body’s regenerative abilities and cells to create treatments that are completely ‘natural’, completely avoid immune system rejection, and avoid ethical issues…” (Ko, 2006, p. 4).

Tissue engineering as a biological art Aside from the purposes of human treatment, tissue culture and engineering has been implemented into art forms to further engage human populations in ethical issues in tissue engineering and biotechnology. One famous exhibit established in Tissue Engineering: A Biological Art Form

6

1996, The Tissue Culture and Art Project, “explores how tissue engineering can be used as a medium for artistic expression” (Catts & Zurr, 2022). Created by Oron Catts and Ionat Zurr, the exhibit incorporates tissue cultured clothing and structures, lab grown food, and semi-living sculptures to redefine the relationship between humans and nonliving objects. Catts and Zurr coined the term semi-living in the design of their artwork and the entire project to describe a different category of life that originates from a laboratory. To be semi-living involves the isolation of cells and tissues from organisms and the requirement of human and technological intervention for survival (Catts & Zurr, 2022). Using these semi-living objects to create art, Catts and Zurr hope to examine “the position of the human in regard to other living beings and the environment” and explore philosophical, cultural, and ethical purposes of the semi-living and the future uses they offer to humans. One of the pieces of art I find most meaningful by Catts and Zurr is the Semi-Living Worry Doll. Sculpted from biodegradable polymers — including PGA and P4HB — and surgical sutures, these worry dolls have a deep meaning in the scientific realm (Catts, 2017). They based this artwork off the old tale that Indigenous Guatemalans told their children, who would have six worry dolls to express their worries and concerns to at bedtime. Catts and Zurr created seven of these genderless dolls, for there are many people who are no longer children and have far more than six worries (Catts, 2017). Each worry doll has a different letter representing a different worry relating to societal, philosophical, and scientific ethical issues. My personal favorite is Doll G, which is actually not a doll as the genes are present in all semi-living dolls (Catts, 2017). To be more specific, each of these dolls are sterilized with endothelial, muscle, and osteoblasts cells that are grown over the polymers, which degrade as tissue grows (Catts, 2017).

7

Tissue Engineering: A Biological Art Form

Figure 2: A Semi-Living Worry Doll H: The TC&A Project from the Tissue Culture & Art(ificial) Wombs Installation, Ars Electronica 2000. Photo courtesy of Internalia Magazine.

To be semi-living involves the isolation of cells and tissues from organisms and the requirement of human and technological intervention for survival (Catts & Zurr, 2022).

Another one of my favorite artworks by Catts and Zurr is Victimless Leather. Catts and Zurr grew living tissue into a leather-like material to confront the moral implications of wearing dead animal parts for “protective and aesthetic reasons” and addresses the relationships of manipulated living systems for human benefit (Catts, 2017). This artwork uses the medium of biodegradable polymers of connective and bone cells which allows for the audience and viewers to question our usage of other living beings for materialistic purposes. By using semi-living parts of living systems we are familiar with and displaying it as an art project, Catts and Zurr take a somewhat ironic approach to showcase the “technological price” society will pay for achieving a “victimless utopia” (Catts, 2017). As a person who is strongly against the use of animal skins and fur for everyday materialistic items, I enjoyed reading about this artwork and believe that it would be impactful for those who are interested in understanding the impacts of this common method of designing clothes.

Figure 3: Victimless Leather - A Prototype of a Stitch-less Jacket grown in a Technoscientific “Body” TC&A Project. Photo courtesy of Interalia Magazine.

On the topic of how technology has introduced the idea of a victimless utopia, Catts and Zurr have created another artwork that also uses biodegradable polymers from connective and bone cells of prenatal sheep to make a Semi Living Steak. The idea for this project emerged from Zurr’s research residency at Massachusetts General Hospital of Harvard Medical School from 2000 to 2001 in the Tissue Engineering and Organ Fabrication Laboratory (Catts, 2017). The skeletal muscles of the prenatal sheep were used as part of research for in utero tissue engineering techniques. Aside from its uses in research, Catts and Zurr decided to design a semi-living steak to provide a physical representation of the unborn sheep’s semi-living components as they are removed from the host. By showcasing this, they reintroduce the explicit violence that has been diminished by society into implicit violence when it comes to consumption of “victimless meat” (Catts, 2017). This project addresses the most common means of interaction between humans and the living world — food.

By showcasing this, they reintroduce the explicit violence that has diminished by society into implicit violence when it comes to consumption of “victimless meat” (Catts, 2017).

Tissue Engineering: A Biological Art Form

8

Figure 3: Semi Living Steak 2000, TC&A Project. Photo Courtesy of Interalia Magazine. In its many applications, tissue engineering has provided our society and patient populations with many benefits in both biomedical treatment and through artistic mediums. Both the medical and artistic forms of tissue regeneration highlight the ethical issues between science and society in meaningful ways that have the potential to change the progression of medicine and society’s perspective of our interactions with the living communities around us.

References 1.

2.

3. 4.

5.

6.

Catts, O., & Zurr, I. (2017, November). The Tissue Culture & Art Project. Internalia Magazine. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://www.interaliamag.org/articles/tissue-culture-art-project-oron-catts-ionatzurr/. Grayson, K. (2017, September 26). 3D Printing Bioactive Glass Scaffolds for Tissue Regeneration. Mo Sci Corporation. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://mo-sci.com/3d-printing-bioactive-glass-scaffoldsfor-tissue-regeneration/. Jones, J. R. (2008). Bioactive Glass. Bioglass - an overview. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://www. sciencedirect.com/topics/materials-science/bioglass. Ko, H., Catts, O., & McFarland, C. (n.d.). 9th International Conference on Public Communication of Science and Technology (PCST). In PCST Network (pp. 1–6). Seoul. Retrieved from https://pcst.co/ archive/paper/1307. Rahaman, M. N., Day, D. E., Bal, B. S., Fu, Q., Jung, S. B., Bonewald, L. F., & Tomsia, A. P. (2011, June). Bioactive glass in tissue engineering. Acta biomaterialia. Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3085647/. Tissue, Culture & Art Project. The Tissue Culture & Art Project. (n.d.). Retrieved March 12, 2022, from https://tcaproject.net/about/.

9

Tissue Engineering: A Biological Art Form

Ethics in Research a presentation by Sarah Auletta, Public Health Major, 2024

K

nown in the science community as HeLa, and unknown to everyone else, Henrietta’s Lacks’ cells are widely used as sample cells for scientific research around the world. Her story is even lesser-known than the use of her cells and deserves a place in every classroom. Henrietta Lacks was an African American woman who was diagnosed with cancer, but was brushed off by medical professionals due to racial discrimination. Her health rapidly declined and she died soon after. It was at this point that her cells were harvested and the discovery was made that her cells replicated on their own.This served a need in the science community for countless experiments, so her cells were distributed with the name HeLa and shipped worldwide. Her family was unaware, and when they finally found out, it sparked a conversation about consent and the rights to family members postmortem.The following slides are from a presentation given on the book The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks that also includes similar stories. We have shed light on this issue but the lessons still need to be spread. I urge you to consider this story as you conduct your own research, and next time you see or use HeLa cells, remember who they came from.

Presentation: Ethics in Research

10

1. 2.

Ethics in Research Author Rebecca Skloot illustrates how patients were severely mistreated in the mid-20th century to demonstrate that practices at the time were not ethical but were necessary to produce the standards that are in place today.

Moore’s Spleen • Moore’s spleen and cells were taken advantage of: “a patient on Moore’s cells, and several extremely valuable proteins those cells produced” (Skloot 201). • This had to happen to have the lawsuit and Moore win an appeal case which caused many new laws to be put in place to uphold ethics • Cause and effect > cause is Moore being taken advantage of > effect is law

3.

11

Presentation: Ethics in Research

TeLinde’s Samples • TeLinde was taking samples from Henrietta without consent • “No one had told Henrietta that TeLinde was collecting samples or if she wanted to be a donor” (Skloot 33). • The actions were wrong and should not have been taken. . . but it was necessary for progress to be made with vaccines • Skloot acknowledges the actions were wrong and unethical but produced progress

Treatment of Patients at Crownsville

4.

• Depicts how the “patients were locked in poorly ventilated cell blocks with drains on the floors instead of toilets” and other various harsh conditions (Skloot 275). • Details the unethical studies such as the “Pneumoencephalography and skull X-ray studies in 100 epileptics” (Skloot 275). • Elsie was subject to these subjects and conditions

So What Do You Think?

5.

• Did we get Skloot’s argument correct? • If you disagree with us what would you change about our interpretation? • Do you agree with Skloot’s argument? • Were these unethical practices necessary to get society to the mere ethical practices we use today? • Did these practices change how ethics in research is today? • Are patients treated better in today’s society? • Is there still mistreatment in the medical field? Is it being covered up or are people aware of it?

Presentation: Ethics in Research

12

6. 1. 2.

3. 4. 5.

13

Works Cited Chausse, Leslie. “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” AP Language and Composition A Period, Apr. 2019, Clinton, The Morgan School. “From the Archives: Crownsville State Hospital.” The Darkroom: Exploring Visual Journalism from the Baltimore Sun, darkroom.baltimoresun.com/2015/01/ crownsville-state-hospital/. “Hippocratic-Oath | Medical School | Doctor Tattoo, Nursing Profession, Med Student.” Pinterest, www.pinterest.com/pin/184225440982670733/. Qnan, D. W. (1984). Patent No. 4,438,032 . California Berkeley Calif. Skloot, Rebecca. The Immortal Life Of Henrietta Lacks. New York : Crown Publishers, 2010. Print.

Presentation: Ethics in Research

Measuring (Trans)gender in Demographic Survey Research by Eliot Stanton, Data Science Major, 2022

D

ue to the powerful consequences of choosing gender categorization schemes, from the normalization of certain genders to the exclusion of others in such a way that has significant effects on people’s life chances, there has been much debate over how to best measure gender, and transness specifically. I will focus on gender categorization in demographic survey research as an example to illustrate the various motivations, methods, and obstacles involved. The current standard in transgender data in the United States is the U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS), conducted by a nonprofit called the National Center for Transgender Equality between 2011 and 2016, with another survey planned for 2022. As Labuski and Keo-Meier (2015) explain, the 2011 NTDS “stabilized the term transgender in order to produce their data,” though the survey included many forms of transness (p. 18). The survey’s designers admittedly had to compromise expansive representation and found it challenging to develop “liberating versus limiting” boxes (Hoffmann, 2017, p. 10). Despite its imperfections, the data from the USTS/NTDS continues to be necessary, as “any and all evidence of the statistical prevalence of a population that some would prefer remain invisible is a political and human rights necessity” (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 15). Several problems with data quality and accuracy arise when researchers attempt to count the number of trans people in their target population. First, quantitative analysis becomes more complicated as the number of gender categories increases. Though the pool of gender identities is qualitatively rich, it lacks any order or system (Singer, 2015, p. 65).This is in part due to the unstable nature of gender itself, especially as it is defined in gender studies, which makes the production of measurements and data difficult (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 18). While there may be an “inevitable uncontainability of categorical excess” in transspecific data collection, researchers still attempt to “capture the experience of being trans for the widest variety of readers in ways that benefit transgender people” through gender categorization schemes (Singer, 2015, p. 65 & Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 14). Since there is no universal standard for which trans identities to include, studies and surveys utilizing different definitions of transness

First, quantitative analysis becomes more complicated as the number of gender categories increases. Though the pool of gender identities is qualitatively rich, it lacks any order or system (Singer, 2015, p. 65).

Measuring (Trans)gender in Demographic Survey Research

14

cannot be compared with each other. For example, Singer (2015) compares two needs-assessment studies and demonstrates that one only counted people as trans if they reported “a discordance between their birth-sex assignment and current gender identity” (p.67). The other study allowed selection of multiple gender identities and ultimately included over a third of its participants, assigned male at birth, whose primary gender role was male but who also identified as drag queens, cross-dressers, or transgender (p. 67). In another study comparison, one study’s inclusion criteria “ranged from surgery to pronoun use,” whereas for the other, it required someone to be considering surgery to be counted as transitioning (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 19). The “lack of concordance” between definitions of trans identity and resulting gender categorization schemes limits the ability for studies of trans people to “generate widely useful data” that can be compared (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 19). In her manifesto “The Ethical Case for Undercounting Trans Individuals,” Megan Rohrer (2015) presents other issues with the collection of trans data. The fact that some people choose not to come out as trans when participating in a survey challenges the accuracy of data reportedly measuring trans populations. These “low/non-disclosing individuals’’ have transitioned and can now pass as their gender identity, and they either choose to keep their trans status to themselves or no longer identify as trans at all (Rohrer, 2015, p. 177). If these individuals are part of a researcher’s target population, their results will always undercount the trans community (Rohrer, 2015, p. 176). Including or excluding non disclosing people could skew statistics too. Data including them could decrease discrimination rates and obscure the violence faced by those who live openly as trans, while data excluding them could increase violence statistics and lead other trans people to delay or forgo transition (Rohrer, 2015, p. 177). All this leads to a dilemma: the trans community is not represented in full without accounting for non disclosing individuals, but including them privileges the researcher’s definition of who is trans over the individual’s right to self-identify (Rohrer, 2015, p. 177). Perhaps most concerningly, Rohrer’s work with homeless individuals shows that already-vulnerable populations are often made more vulnerable by disclosing their trans identity. She explains that the surveys most successful at capturing gender identity were very time consuming, risked violating their privacy, and were used to gatekeep access to other resources (Rohrer, 2015, p. 176). Ultimately, “providing unnecessary medical information to strangers can leave trans individuals feeling pathologized, overexposed, and abnormal,” so Rohrer recommends supporting and advocating for the trans community without attempting to count it (p. 176). Despite this compelling argument, some would counter that it is the trans community’s vulnerability that better estimates of the true number of trans people, which is why they should be calculated in order to bolster advocacy for

15

Measuring (Trans)gender in Demographic Survey Research

Rohrer’s work with homeless individuals shows that alreadyvulnerable populations are often made more vulnerable by disclosing their trans identity. She explains that the surveys most successful at capturing gender identity were very time consuming, risked violating their privacy, and were used to gatekeep access to other resources (Rohrer, 2015, p. 176).

trans people’s needs. In general, arguments for better trans data suggest that a more accurate count will be larger, and therefore demands by trans activists for services and policies benefiting trans people will carry more weight. It is true that here, more accurate implies larger, since the current obstacles to accuracy are the narrow definitions of trans identity, when it is included, in data collection. Doan (2016) acknowledges “the perils of forcing queer subjects into tick boxes” but describes the “need for transgender-accessible bathrooms” as “urgent” and “requir[ing] a more inclusive count” (p. 89). She claims that not improving methods of counting trans people “simply reifies outdated medical models that severely underestimate the size of this community” (Doan, 2016, p. 105). Thus, as much as updating gender categorization schemes can stabilize a normative notion of trans identity, not updating gender categories at all to include other gender variance further entrenches the erasure of trans identity outside medical transition entirely. With a more accurate count, institutions will supposedly be better able to “provide appropriate services to a highly vulnerable community,” combatting discrimination and violence (Doan, 2016, p. 92). One such example is found in an opinion piece by several Ph.D. students, who exist outside the gender binary, calling upon the National Science Foundation to include nonbinary gender categories in its data collection on funding recipients (DeHority et al., 2021). They write that an improved list of gender categories allows for the quantification of disparities in career opportunities, funding, and workplace harassment, even going so far as to add that “the lack of information on transgender and gender diverse scientists is both a symptom and cause of exclusion from science at large” (DeHority et al., 2021).

Thus, as much as updating gender categorization schemes can stabilize a normative notion of trans identity, not updating gender categories at all to include other gender variance further entrenches the erasure of trans identity outside medical transition entirely.

Gender categorization schemes in demographic survey research have thus far proven to be a useful illustration of the positive and negative consequences of incorporating trans identities for trans people and trans activism. Here I briefly explore multiple proposed ways of measuring transness. The “two-step” method of calculating transness via birth sex and current gender identity is popular, but its reliance on the artificial separation of sex and gender tends to erase “gender-nonconforming racial minorities who occupy the bottom rungs of the socioeconomic ladder” (Singer, 2015, p. 66-68). Outside of health research that requires a specific understanding of a person’s anatomy, it may be better to just ask participants whether or not they self-identify as trans (DeHority et al., 2021). However, this does potentially obscure the many types of gender variance, lumping together “a wide variety of multidimensional individuals… many of whom have little in common aside from their gender-diverse bodies and practices” (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 14). By excluding anyone who says they are not trans from research, a cis-trans binary is reinforced, when in reality some people identify with neither and should be included in a study intending to investigate any experience outside being cisgender. Other suggested gender

Measuring (Trans)gender in Demographic Survey Research

16

categorization schemes range from the simple five-category list of man, woman, nonbinary, prefer not to say, and prefer to self-describe via write-in (Keyes et al., 2021, p. 3) to an open-ended write-in replaced by many categories if unfeasible (DeHority et al., 2021). For quick calculations based on existing data, Doan (2016) recommends inflating current numbers via her estimates applying potentially more accurate numbers found through smaller samples to the entire United States population. Multiple recommendations involve a more radical shift away from the dominant gender system. One approach hinges upon participatory design, or soliciting and applying input from members of the target community. In the case of survey design, especially on a community level, this could mean including more niche gender categories that resonate with the participants. In a study by the YES Center, input from gay youth of color resulted in vernacular gender categories like “femme queen” which allowed participants to be “explicitly included on their own terms” (Singer, 2015, p. 69-70). Likewise, the Trans-health Information Project distributed safer sex supplies in Philadelphia based on “categories that it temporarily and provisionally breaks, reframing bodies in nonbinary code akin to a street poetry that riffs on and with standardized public health practices” (Singer, 2015, p. 71). The “tactical, local, and shifting outreach approach” taken by organizers instead of “umbrella-like inclusion” produced gender categories like Flygirls, Divas, and BoiScouts that were relevant to the community (Singer, 2015, p. 70-71). These examples of contextually-specific gender categorization schemes illustrate the multiplicity of context outlined by Keyes et al. (2021), who “argue that researchers should treat gender as fundamentally multiplicitous: as a concept with many meanings and relations to individuals and communities” (p. 2). In order to determine the proper meaning of gender for a given survey, they recommend considering many elements including how researchers and participants define gender, the role of gender in analysis, and who is excluded from the categories ultimately chosen (Keyes et al., 2021, p. 14). Labuski and Keo-Meier (2015) concur, suggesting that “research design should begin with questions that specify what is to be learned from a specific transgender population” (p. 19). In recognizing the multiple concepts associated with gender, it becomes apparent that gender is often measured as a proxy for other more specific traits, such as gender identity, social gender role, hormone levels, and bodily anatomy (Keyes et al., 2021, p. 5). Narrowing in on “more methodologically explicit delineations of whether and how sex/gender functions as an independent variable” leads to the realization that many of the experiences with gender-targeted by data collection do not neatly separate trans and cis populations (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 27). For example, many cis men undergo hormone replacement therapy

17

Measuring (Trans)gender in Demographic Survey Research

In order to determine the proper meaning of gender for a given survey, they recommend considering many elements including how researchers and participants define gender, the role of gender in analysis, and who is excluded from the categories ultimately chosen (Keyes et al., 2021, p. 14).

to boost low testosterone levels, and many cis women cannot menstruate, just for different reasons than trans women. Including non-trans people when relevant and “de-essentializing transgender need not compromise our efforts to document and measure its lived experience” (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 26). Instead, shifting focus to a category that better represents the population of interest resists “fixed understandings of trans”, and still allows for narrowing in on a certain trans population if desired (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 14). Ultimately, this avoids constructing trans and non-trans “as mutually exclusive categories” (p. 17) where “nontransgender status…[is] naturalized” by gender norms (p. 25) (Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015). Otherwise, in Valentine’s words, trans people “bear the full weight of binary gender,” and in Stryker’s, transgender will “contain all [the] gender trouble” and radicality (Stryker, 2004, as cited in Labuski & Keo-Meier, 2015, p. 25; Valentine, 2012, as cited in Labuski & KeoMeier, 2015, p. 24). Of all the survey methods discussed, those which include contextual nuance are least likely to result in gender categorization schemes that regulate trans identity, expose trans people to increased vulnerability, and produce inaccurate results.

References 1.

2. 3.

4. 5.

6.

DeHority, R., Ramos Báez, R., Burnette,T., & Howell, L. (2021,August 30). Nonbinary scientists want funding agencies to change how they collect gender data. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/ article/nonbinary-scientists-want-funding-agencies-to-change-how-they-collect-gender-data/. Doan, P. L. (2016). To count or not to count: Queering measurement and the transgender community. Women’s Studies Quarterly, 44(3/4): 89-110. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44474064. Keyes, O., May, C., & Carrell, A. (2021, April 22).You keep using that word: Ways of thinking about gender in computing research. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5(CSCW1): Article 39. https://doi.org/10.1145/3449113. Labuski, C., & Keo-Meier, C. (2015). The mis(measure) of trans. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 2(1): 13-33. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2848868. Rohrer, M. (2015). The ethical case for undercounting trans individuals. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 2(1): 175-178. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2848958.

Singer, T. B. (2015). The profusion of things: The “transgender matrix” and demographic imaginaries in US public health. Transgender Studies Quarterly, 2(1): 58-76. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2848886.

Measuring (Trans)gender in Demographic Survey Research

18

Using Coccolithophorid Algae to Combat the Climate Crisis by Emily Douglas, Chemistry Major, 2025

T

here is no question that the world today is facing higher percentages of greenhouse gasses, such as carbon dioxide, in our atmosphere. With 412.5 parts per million of CO2 as of 2020 , this number has surpassed the precedent amount of carbon dioxide to ever be in our atmosphere (Lindsay, 2021). The detrimental effect of these greenhouse gasses is that they create what is known as the greenhouse effect, in which the sunlight reflected by Earth’s surface does not escape the atmosphere, thus resulting in rising temperatures. The increase of the Earth’s temperature will have detrimental effects, including an increase in sea levels, change in precipitation patterns, intense droughts and heatwaves, and many other disastrous effects. This has become a worldwide concern; countries have been coming together to tackle this issue through acts such as the Paris Climate Agreement. These agreements to reduce the emissions of CO2 are a step in the right direction, but what the world needs is a sustainable solution along with these efforts. Coccolithophorid Algae. Photo courtesy of JAMSTEC.

19

Using Coccolithophorid Algae to Combat the Climate Crisis

The Coccolithophorid Algae is a marine unicellular, eukaryotic phytoplankton. The species is unique in that they contain chlorophyll, conduct photosynthesis, and possess special plates or scales known as coccoliths, created through the process of calcification. The phenomenon of calcification in algae is the deposition of calcium carbonate after the organism absorbs carbon dioxide from its surroundings. This mechanism is known for the depletion of aqueous carbon dioxide. For this reason, Coccolithophorid Algae has attracted global interest because of its many remedial advantages. Coccolithophorid Algae could be very beneficial in reducing CO2 in the atmosphere through the high CO2 levels necessary for the organism’s photosynthesis. The sustainability of this method relies strongly on the calcification process in which the algae produces calcium carbonate that encases the organism and sinks it to the bottom of the ocean. This creates a marine carbon sink, trapping the CO2 and eliminating it from the atmosphere. Therefore, the process of carbon fixation could be a viable solution for the greenhouse gas crisis. Design of CO2 fixation by artificial weathering of waste concrete and culture. Photo courtesy of ResearchGate.

A study conducted in the United Kingdom proved this theory. Scientists at the University of Essex grew a non-calcifying strain of the marine coccolithophorid, Emiliania huxleyi, with an air of 360 or 2000 ppm CO2, under high and lowlight conditions, and in seawater either filled with or deficient in nitrogen and phosphorus. The researchers found, “increased atmospheric CO2 concentration enhances CO2 fixation into organic matter,” but “only under certain conditions, namely high light, and nutrient limitation.” and this proved that “enhanced CO2 uptake by phytoplankton such as E. huxleyi, in response to elevated atmospheric CO2, could increase carbon storage in the nitrogen-limited regions of the oceans and thus act as a negative feedback on rising atmospheric CO2 levels” (Leonardos, Nikos & Geider, Richard, 2005). This study makes it increasingly evident that algae have valuable abilities through photosynthesis. If this could be expanded on the CO2 in our atmosphere and oceans, the greenhouse effect can be reduced.

Using Coccolithophorid Algae to Combat the Climate Crisis

20

Furthermore, the Coccolithophorid Algae has already been reproducing rapidly due to rising CO2 levels. A study done in 2008 by researcher Iglesias-Rodriguez, et al. determined there had been a 40% increase in oceanic coccolith mass over the past 220 years. Based on data obtained from a sediment core extracted from the subpolar North Atlantic Ocean, the scientists deduced that the atmosphere’s CO2 concentration had risen by approximately 90 ppm (Halloran, Hall, Colmenero-Hidalgo & Rickaby, 2008). In the researchers’ words, this revealed “a changing particle volume since the late 20th century consistent with an increase in the mass of coccoliths produced by the larger coccolithophore species” (p. 1615).

Coccolithoprod Algae has already been reproducing rapidly due to rising CO2 levels.

In the future, it may be useful to explore other ways algae could create a more sustainable world. Algae is used to produce biofuels, fuels derived directly from living matter. Therefore, it can provide a more sustainable alternative to carbonproducing fossil fuels, like petroleum. Algae is known to produce as much as 5,000 biofuel gallons from a single acre in one year, and the US Government first explored algae as a petroleum alternative during the energy crisis in the 1970s (Rothstein, 2008). They ultimately abandoned the project in the 1990s because they could not make it competitive with the pricing of petroleum Rothstein, 2008). However, with the rising costs of oil and an imperative to find cleanenergy solutions, oil companies such as Exxon and venture capitalists are pouring money into solving the algae-as-fuel equation. Furthermore, Dutch designers Eric Klarenbeek and Maartje Dros use algae to create polymers that can be used in 3D printing as a replacement for plastic. “In principle, we can make anything from this local algae polymer: from shampoo bottles to tableware or rubbish bins,” says the firm’s project coordinator Johanna Weggelaar (Diaz, 2017, para. 6). According to Lamm (2019) their goal is to “ultimately turn an industrial manufacturing process—a source of pollution that contributes to global warming—into a way to subtract CO2 from the atmosphere. Using algae as a raw material would turn any mode of production into a way to help the environment” (para. 14). Coccolithophorid Algae should be utilized in the future as a means of negative feedback on rising atmospheric CO2 levels. Research shows that coccolithophorid algae are efficient in their carbon fixating abilities, and that species of the algae increased coccolith production as a result of anthropogenic CO2 release. Overall, this could be a sustainable and efficient solution to the rising CO2 levels in our atmosphere and benefit us as a society.

21

Using Coccolithophorid Algae to Combat the Climate Crisis

“In principle, we can make anything from this local algae polymer: from shampoo bottles to tableware or rubbish bins” (Diaz, 2017, para. 6).

References 1.

Diaz, J. (2017, December 18). The Creators Of This Algae Plastic Want To Start A Maker Revolution. Fast Company. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://www.fastcompany.com/90154210/the-creatorsof-this-algae-plastic-want-to-start-a-maker-revolution.

2.

Halloran, Hall, Colmenero-Hidalgo, & Rickaby. (2008). Evidence for a multi-species coccolith volume change over the past two centuries: understanding a potential ocean acidification response. Biogeosciences, 5(6), 1651–1655. https://hero.epa.gov/hero/index.cfm/reference/details/reference_id/2604735.

3.

Lamm, B. (2019, October 1). Algae might be a secret weapon to combating climate change. QUARTZ. Retrieved February 13, 2022, from https://qz.com/1718988/algae-might-be-a-secret-weapon-tocombatting-climate-change/.

4.

Leonardos, Nikos & Geider, Richard. (2005). Elevated atmospheric carbon dioxide increases organic carbon fixation by Emiliania huxleyi (Haptophyta), under nutrient-limited high-light conditions. Journal of Phycology, 41, 1196 - 1203.10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00152.x.

5.

Lindsay, R. (2021, October 17). Climate Change: Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. Climate.gov. Retrieved February 19, 2022, from https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-changeatmospheric-carbon-dioxide.

6.

Rothstein, M. (2008, December 3). Why Algae Will Save Us From the Energy Crisis. Esquire. Retrieved February 19, 2022, from https://www.esquire.com/news-politics/a5310/algae-save-energy-crisis-1208/.

Using Coccolithophorid Algae to Combat the Climate Crisis

22

The Power of Accepting Unpleasant Emotions by Alyssa Cameron, Psychology Major, 2023

B

etween parents, social media, and peers, most people have been exposed to messaging that preaches “positivity.” Quotes such as “just be positive” or “just look at the bright side” might come to mind. Such messaging suggests that it is possible and ideal to only experience positive emotions. It encourages people to push through, ignore, or change their unpleasant sensations in exchange for more comfortable ones. On the surface, this messaging seems helpful, or at the very least, harmless. However, research shows that adopting this mindset about emotions is damaging to one’s well-being. Multiple studies have shown that individuals who place more value on positivity or have higher expectations for happiness are, on average, actually less happy (Mauss et al., 2011). Similarly, because people with this mindset are overloaded with judgments that unpleasant feelings are “bad,” they are more likely to engage in unhelpful responses such as avoidance and rumination (David, 2016). In contrast to a resistant and judgemental approach to unpleasant emotional experiences, approaching such experiences with acceptance has been associated with greater psychological health (Ford et al., 2018). Fully experiencing and accepting unpleasant emotions is key to improving psychological well-being and can lessen the frequency and intensity of unpleasant emotions an individual experiences. Emotions are neurochemical systems that evolved to help us navigate the complex stimuli in our external world (David, 2016). Some emotions are far more pleasant to experience than others. Dr. Joan Rosenberg, a psychologist whose work focuses on unpleasant emotions and emotional mastery, identifies eight key unpleasant emotions: sadness, shame, helplessness, anger, vulnerability, embarrassment, disappointment, and frustration (Rosenberg, 2016). When one of these feelings gets triggered, chemicals are released in the brain, rush through the bloodstream, and activate various bodily sensations. Emotional experiences are first felt as these physical sensations, which are very real, very uncomfortable, and tempting to avoid. Rosenberg (2016) argues that it is not necessarily the emotion itself but the associated physical sensations that people want to run away from.

23

The Power of Accepting Unpleasant Emotions

Fully experiencing and accepting unpleasant emotions is key to improving psychological wellbeing and can lessen the frequency and intensity of unpleasant emotions an individual experiences.

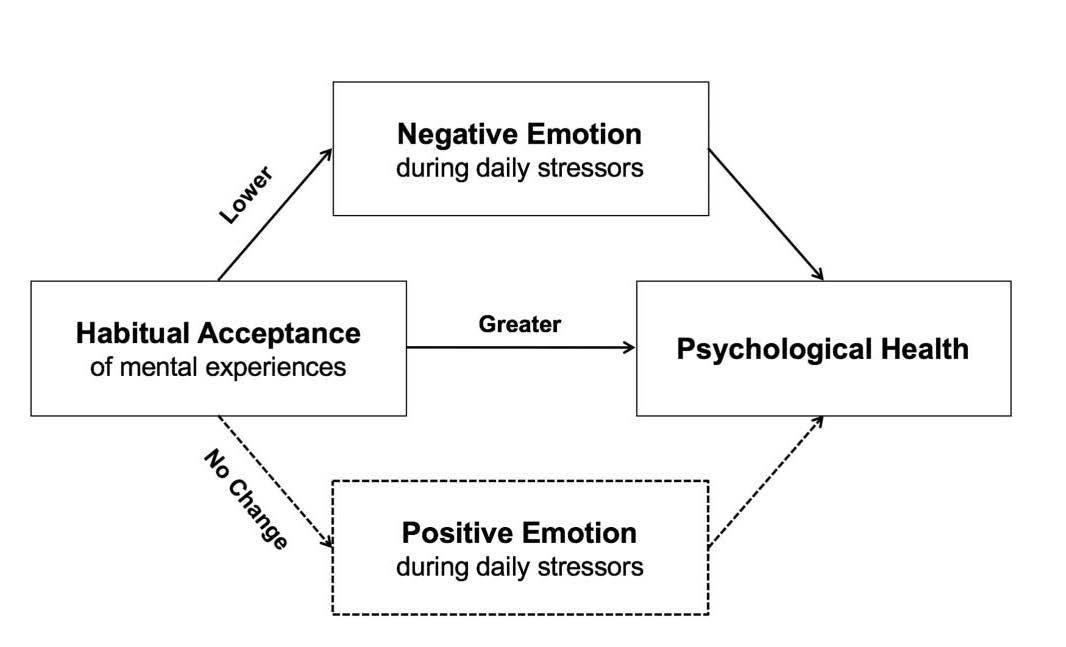

These unpleasant emotions are natural, unavoidable, and fortunately, can be incredibly helpful. Despite being so uncomfortable to experience, these emotions made the evolutionary cut, and for good reason. According to Forgas (2013), unpleasant emotional states encourage slower, more systematic processing.When we are experiencing an unpleasant mood state, we rely less on heuristics and cognitive biases and pay more attention to subtle details. Unpleasant emotions are also associated with improved memory, motivation, and more effective interpersonal interactions (Forgas, 2013).This highlights that unpleasant feelings can have positive outcomes. However, how one approaches these emotional experiences, such as with avoidance or rumination, can have negative outcomes. The ways in which an individual may avoid an unpleasant emotion varies from person to person and emotion to emotion. It may involve turning to external stimuli; eating food, doing drugs, shopping, or scrolling through social media. It may manifest in physical responses such as tightened muscles or shallow breathing (Rosenberg, 2016) Regardless of how someone avoids their unpleasant sensations, they are attempting to suppress or alter their experience and depriving themselves of the opportunity for growth and change (David, 2016). Other individuals may approach their unpleasant emotions with rumination. These individuals find themselves stuck dwelling on their unpleasant emotions, how distressing and “bad” they are, and how much they want them to go away. Dr. Susan David, a psychologist whose work focuses on a concept she refers to as “emotional agility,” claims that ruminating on uncomfortable emotions is entirely unhelpful in getting an individual closer to resolving the issue at the core of their distress (David, 2016). There is an abundance of evidence that habitual acceptance of unpleasant emotions is associated with greater psychologixal health across various dimentions including higher life satisfaction and fewer mood disorder, depressive, and anxiety symptoms Ford et al. (2018) hypothesized that habitual acceptance of unpleasant emotions (Ford et al., 2018). improves psychological health by causing the individual to experience unpleasant emotions less frequently and with lesser intensity.They theorized that, over time, experiencing lower negative emotions should improve overall psychological health (see Figure 1). While it may seem paradoxical that accepting unpleasant emotions would lead to less unpleasant emotions, the reasoning behind this A more beneficial — albeit more difficult — way to approach unpleasant feelings is with acceptance. An acceptance approach involves acknowledging unpleasant emotions for what they are — temporary, natural, and helpful — without judgment. There is an abundance of evidence that habitual acceptance of unpleasant emotions is associated with greater psychological health across various dimensions including higher life satisfaction and fewer mood disorder, depressive, and anxiety symptoms (Ford et al., 2018). While the exact reason we see these associations is not known, Ford and colleagues (2018) suggest that it may have to do with how emotion acceptance impacts the frequency and intensity with which someone experiences unpleasant emotions.

The Power of Accepting Unpleasant Emotions

24

theory becomes clearer when comparing the acceptance approach to alternative approaches: avoidance and rumination. Consider the avoidance approach to dealing with unpleasant emotions, in which an individual tries to avoid or suppress their unpleasant emotions and corresponding thoughts. According to ironic processing theory, deliberate attempts to suppress certain thoughts make those thoughts more likely to surface. In contrast, accepting these emotions/ thoughts and allowing oneself to feel them in their entirety would make the emotions less likely to continue to occur. Similarly, when an individual buys into the idea that unpleasant emotions are “bad,” they may find themselves dwelling on their unpleasant emotions and experiencing them more intensely. Conversely, accepting these emotions — without judging them as negative and worrying about the emotion — allows the emotion to take its natural course without being exacerbated (David, 2016). Figure 1: The psychological health benefits of accepting negative emotions and thoughts: Laboratory, diary, and longitudinal evidence. Courtesy of Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

Ford and colleagues (2018) conducted multiple studies that found compelling evidence to support this theory. The first study measured participants’ habitual acceptance of their emotions and thoughts, as well as their ill-being and wellbeing across various dimensions, using self-report questionnaires. Results showed a significant positive association between habitual acceptance and psychological well-being. The second study measured participants’ habitual acceptance, as well as their emotional status during a mundane task, via self-report questionnaires. They then exposed participants to an experience designed to induce unpleasant emotion and again measured their emotional status. Participants who had reported habitual acceptance of their emotions experienced less unpleasant emotion after exposure to the stressful event than participants who did not report engaging in habitual acceptance (Ford et al., 2018). This suggests that perhaps habitual acceptance is associated with greater psychological well-being because it leads individuals to experience unpleasant emotions less intensely.

25

The Power of Accepting Unpleasant Emotions

In the final study, the researchers again measured participants’ habitual acceptance of their emotions and thoughts. Participants completed guided diary entries nightly for two consecutive weeks that measured their exposure to stressful events and their emotional status during those events. Results showed that habitual acceptance was associated with less unpleasant emotion during stressful events. In addition, the daily experience of unpleasant emotion mediated the association between acceptance and psychological well-being 6 months after the study was conducted (Ford et al., 2018). This suggests that experiencing less unpleasant emotion in response to daily stressors may be one of the key ways in which emotional acceptance shapes our psychological health. Unpleasant emotions are common and natural to experience in daily life.While it is evident that accepting unpleasant emotions is beneficial for psychological wellbeing, it is certainly easier said than done. Moving from the mindset that unpleasant sensations are “bad” and need to be changed or avoided to the mindset that they are natural and helpful is no easy task. However, with practice, emotional acceptance can become a natural habitual response. As Rosenberg (2016) states, “It is the day to day choices that determine our day to day happiness, not the big choices.” Making the daily choice to respond to unpleasant feelings with acceptance rather than judgment has the potential to make significant changes in your well-being.

References 1.

David, Susan. (2016). Emotional agility. Penguin Random House.

2.

Ford, B. Q., Lam, P., John, O. P., & Mauss, I. B. (2018). The psychological health benefits of accepting negative emotions and thoughts: Laboratory, diary, and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(6), 1075–1092. https://doi-org.ezproxy.simmons.edu/10.1037/pspp0000157.supp

3.

Forgas, J. (2013). Don’t worry, be sad! On the cognitive, motivational, and interpersonal benefits of a negative mood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 22(3), 225-232.

4.

Mauss, I. B., Tamir, M., Anderson C. L., and Savino N. S. (2011). Can seeking happiness make people unhappy? Paradoxical effects of valuing happiness. Emotion, 11(4), 807-815.

5.

Rosenberg, J. (2016, Sept. 23). Emotional Mastery: The Gifted Wisdom of Unpleasant Feelings. [Video]. TED. https://tedxsantabarbara.com/2016/joan-rosenberg/.

The Power of Accepting Unpleasant Emotions

26

Thank you for reading MindScope Issue 12. We tremendously appreciate readers like you. Please stay tuned for our future publications. Read our previous issues at issuu.com/ mindscope or contact us at mindscope.org