Nestled in the foothills of the Ozark Mountains in Missouri, High Adventure Ranch offers all of the excitement of western big game hunting without the costs and hassles.

Be prepared for a fair chase hunt! With over 3 square miles of prime natural habitat, our ranch provides challenges to even the most seasoned hunter, but our experienced guides and “No Game, No Pay” policy practically ensure that you won’t go home empty handed. In addition, High Adventure’s hunting season is year-round, allowing ample time to fit the most demanding schedule.

While our whitetail, elk, wild boar and red stag hunts top our hunter’s most popular lists, hunters from around the world have visited our ranch, hunting everything from American bison, black buck, fallow deer to Spanish goats and African game.

So, whether you desire a 10-point whitetail mount for your trophy room or simply the thrill and challenge of taking down one of our many elusive big game animals, High Adventure Ranch guarantees memories of an unparalleled hunting experience that will bring you back again and again.

THE PREMIER SPORTING GOODS STORE ON PRINCE OF WALES ISLAND

FOR ALL YOUR FISHING, HUNTING, AND CAMPING NEEDS! KNOWLEDGEABLE STAFF WILL LET YOU KNOW WHERE, WHEN AND HOW!

Volume 12 // Issue 8 // May 2023

PUBLISHER

James R. Baker

GENERAL MANAGER

John Rusnak

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Andy Walgamott

OFFICE MANAGER / COPY EDITOR

Katie Aumann

LEAD CONTRIBUTOR

Frank Jardim

CONTRIBUTORS

Stephen A. Bourque, Danielle Breteau, Scott Haugen, Phil Massaro, Mike Nesbitt, Paul Pawela, Nick Perna

SALES MANAGER

Paul Yarnold

ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE

Mike Smith, Zachary Wheeler

DESIGNER

Lesley-Anne Slisko-Cooper

PRODUCTION ASSISTANT

Kelly Baker

WEBMASTER / INBOUND MARKETING

Jon Hines

INFORMATION SERVICES MANAGER

Lois Sanborn

ADVERTISING INQUIRIES ads@americanshootingjournal.com

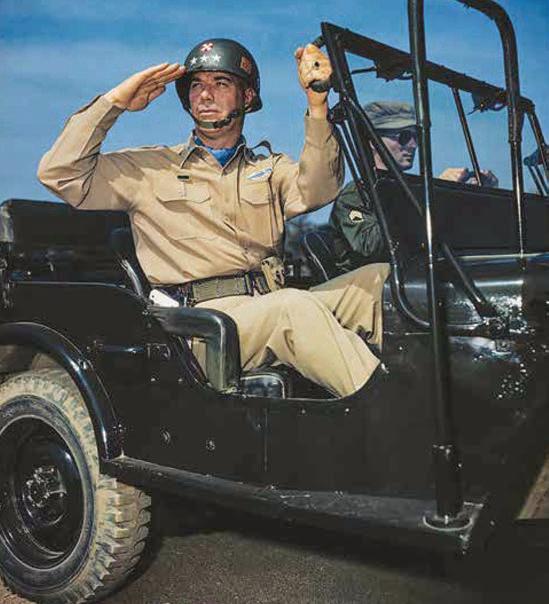

Soldiers from the US 4th Infantry Division move ashore at Utah Beach during the Allied retaking of France in June 1944. The division was led by Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton, who landed with the men and whose movements before, during and after D-Day are this issue’s cover story. (NATIONAL ARCHIVES)

Website: AmericanShootingJournal.com

Facebook: Facebook.com/AmericanShootingJournal

Twitter: @AmShootingJourn

MEDIA INDEX PUBLISHING GROUP 941 Powell Ave SW, Suite 120, Renton, WA 98057 (206) 382-9220 • (800) 332-1736 • Fax (206) 382-9437 media@media-inc.com • www.media-inc.com

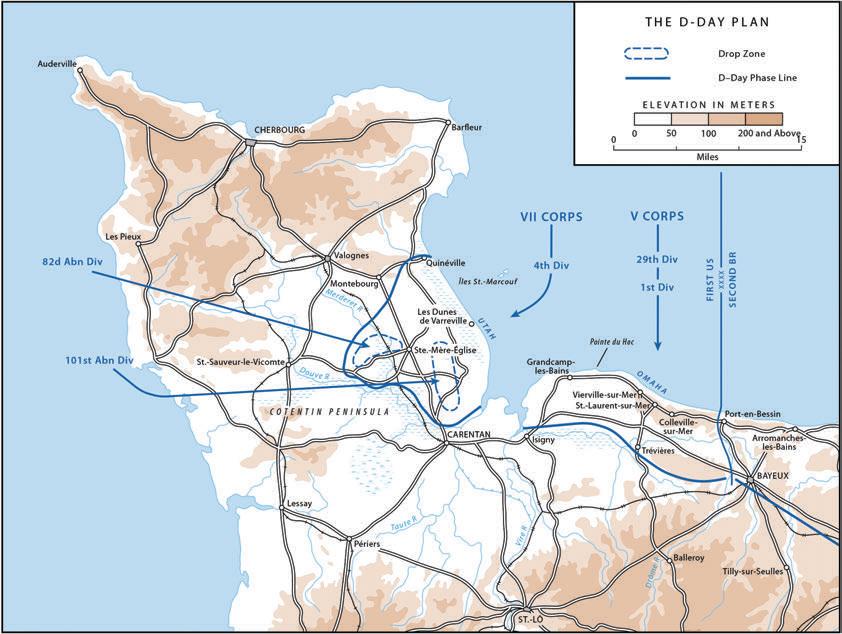

With the 79th anniversary of D-Day coming up, war historian Stephen A. Bourque shares the story of the man who commanded the US 4th Infantry Division, Raymond O. Barton, as he and his men embarked on that “great and noble undertaking,” retaking France and Europe from the Nazis.

45 TAPS: THE STORY OF 24 POWERFUL NOTES

The military bugle call known as “Taps” has a deep history that’s belied by its brevity. Danielle Breteau traces the origins back to European bars and barracks and how it came into its modern form during the American Civil War.

49 MILITARY SPOTLIGHT: VIETNAM VET FINALLY LAID TO REST

Fifty-six years ago, US Navy pilot Paul Claude Charvet went missing in action while on a reconnaissance mission in Vietnam and last month his remains were brought home and laid to rest next to his parents. Learn about this courageous Washington state native who gave his life for his country.

51 SELF-DEFENSE TRAINING: A SPECIAL FORCES LEGEND PASSES ON

The dictionary definition of “legend” is illustrated by a drawing of Billy Waugh, who passed away last month at 93. Paul Pawela remembers the man who fought in Korea and Vietnam, was a CIA operative, hunted Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan and much more during a truly remarkable career spanning decades.

58 WREATHS ACROSS AMERICA: ‘TO REMEMBER AND HONOR’ Learn how a Maine company’s surplus Christmas wreaths spawned an annual tradition honoring America’s fallen soldiers.

60 IN MEMORIAM: 10 FAMOUS VETERANS WHO DIED IN 2022 American Shooting Journal pauses to recognize a few wellknown military veterans who passed away last year and thank them for their service.

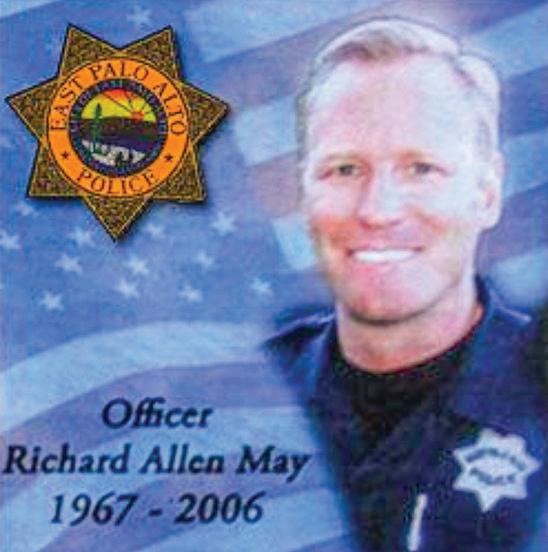

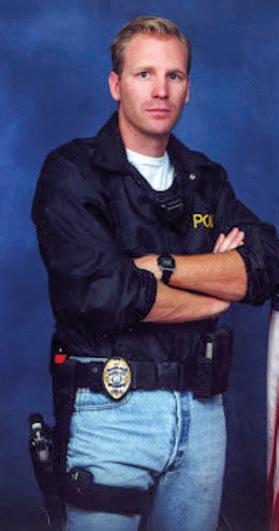

67 L AW ENFORCEMENT SPOTLIGHT: REMEMBERING OFFICER MAY

As Nick Perna remembers California cop Richard May, who was gunned down in the line of duty responding to a fight, he offers an argument for keeping fallen police in our thoughts too this Memorial Day.

70 SCENES FROM THE 2023 NRA ANNUAL MEETINGS

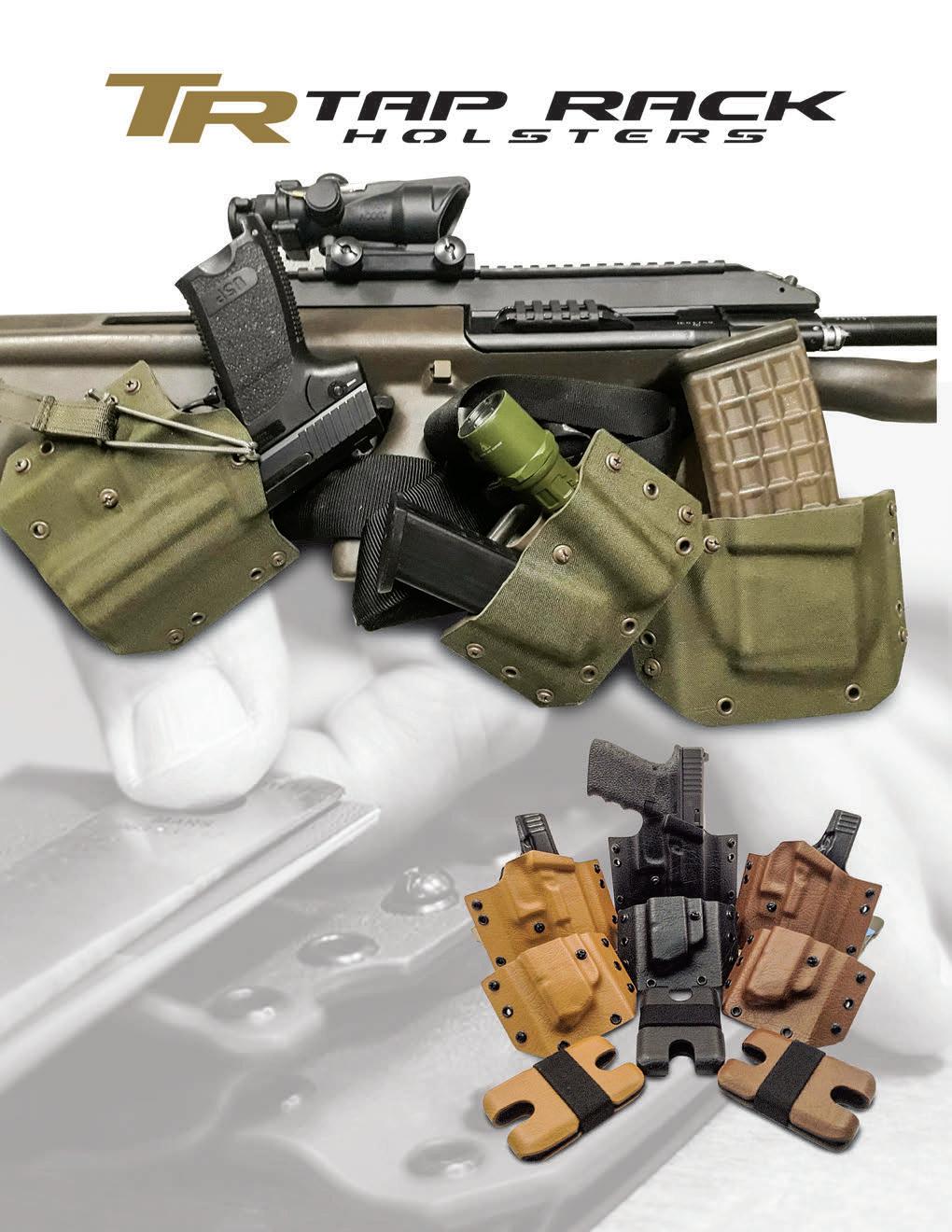

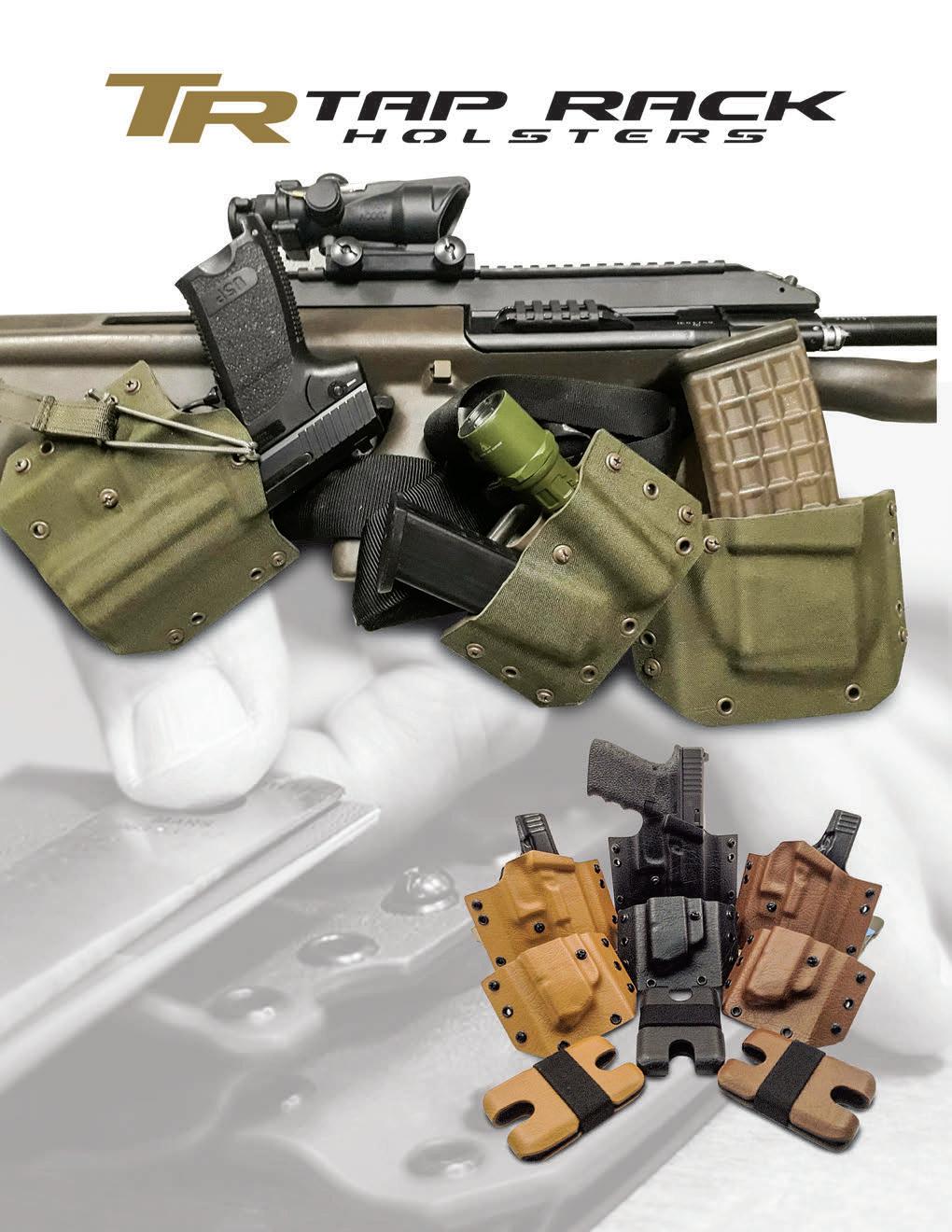

Our general manager John Rusnak was a busy boy in Indianapolis in mid-April, manning our booth, hobnobbing with advertisers and more. He shares pics from the huge event.

72 ROAD HUNTER: HEAD UPHILL FOR LATE TOMS

Lace up your boots, gobbler gunners; Scott Haugen’s taking us on a hike. As spring turkey season wears on, higher elevations are where to hunt for lone toms still receptive to calling.

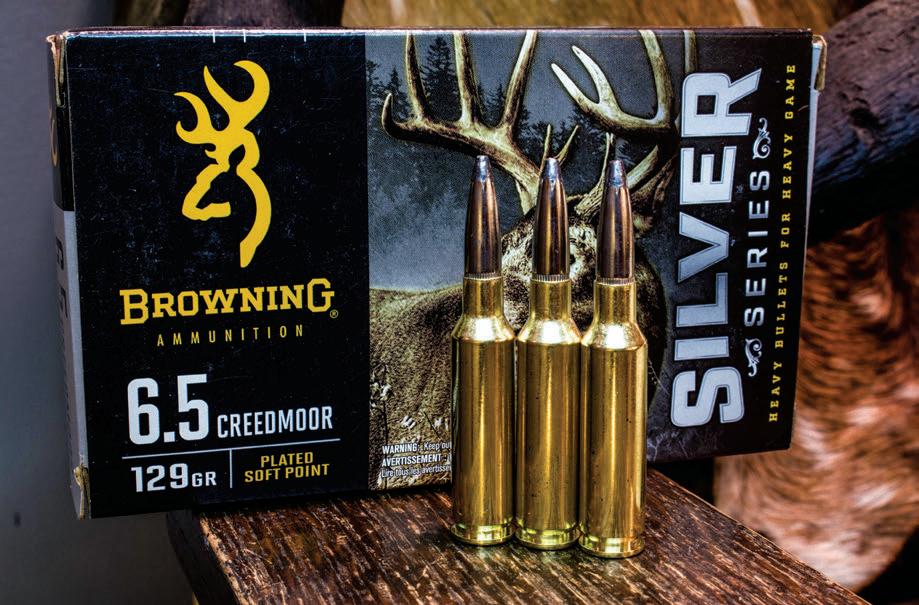

81 BULLE T BULLETIN: A ‘SILVER’ LINING TO THE END OF BROWNING BULLET LINE

BXR bullets disappeared last year and appear to have been replaced by the Silver Series, a “simple and affordable option that gives ample accuracy and striking power,” per our professor of projectiles Phil Massaro, who details the new goods from Browning.

93 BL ACK POWDER: ME, ‘MOONBEAM’ AND THE MATCH

True, Mike Nesbitt and “Moonbeam” – his Hartford Model of 1874 from C. Sharps Arms – did not come in first at his black powder cartridge rifle club’s annual .50-70 match, but they did finish in the top 10 … of an eight-shooter field. Ahem. We’ll let Mike explain why it’s not always about winning.

17 Gun Show Calendar

19 Competition Calendar

21 Precision Rifle Series Schedule, Recent Match Results

usashooting.org

May 17-28

Shotgun National Championships Hillsdale, Mich.

May 20

NTCSC May PTO and USAS

Ranking Match Colorado Springs, Colo.

May 11-14

2023 Area 6 Championship Salisbury, N.C.

May 19-21

Northern Illinois Sectional Muskego, Wis.

May 20-21

Inland Empire Sectional Benton City, Wash.

May 6-7

Foothills GSSF Match

Cherryville, N.C.

May 13-14

Gunsite Glock Classic Paulden, Ariz.

May 5-6

Utah State Shoot Ogden, Utah

May 14

Jefferson State Shoot Cottonwood, Calif.

May 4-7

Western IDPA Regional Championship Sloughhouse, Calif.

May 5-6

OK State IDPA Championship Tulsa, Okla.

May 23-27

300 Meter Nationals/ Selection Match

Elk River, Minn.

June 1-10

2023 USAS Rifle & Pistol National Championships

Fort Benning, Ga.

May 20-21

2023 Great Plains Section Championship

Canton, S.D.

May 26-28

2023 Mid Atlantic Sectional New Tripoli, Pa.

May 31-June 4

2023 Area 5 Championship Brooklyn, Mich.

May 20-21

Belton Blast

Belton, S.C.

May 20-21

Northern Lakes Regional Classic Lake Elmo, Minn.

May 25-28

CMSA National Championship Lincoln, Neb.

June 2-3

Mid-Mountain Regional Rock Springs, Wy.

May 12-13

Maryland State Match

Lexington Park, Md.

May 19-20

Great Lakes Regional Saginaw, Mich.

To have your event highlighted here, send an email to kaumann@media-inc.com.

June 17-18

Team Shooting Stars June PTO Carrollton, Texas

June 2-4

Eastern Lakes Sectional Groton, N.Y.

June 7-11

2023 Nor-Cal Section Championship Sloughhouse, Calif.

June 8-11

2023 Area 4 Championship Whitewright, Texas

June 3-4

Music City Shootout

Mount Pleasant, Tenn.

June 3-4

Big Sioux Ballistic Challenge Valley Springs, S.D.

June 9-11

Washington State Championship Cashmere, Wash.

June 10-11

Virginia State Championship Doswell, Va.

May 25-28

Rocky Mountain Regional IDPA Championship

Palisade, Colo.

June 2-3

WI State IDPA Championship

West Bend, Wis.

May 6

May 6

May 13

May 20

May 27

Okie Showdown AG Cup Qualifier

Vortex Vengeance

Federal King of Coal Canyon

Parma Precision Rifle Rumble

K&M Kahles Precision Rifle Competition

June 3 Pigg River Precision H.A.M.

June 10

June 23

The Lead Farm Barrel Burner 2.0

Hornady Precision Rifle Challenge

July 8 2023 Hodgdon Punisher Positional

July 15 THS Steel Challenge

July 15

July 22

July 28

Twisted Barrel Scorcher

Sheepdog Showdown

Blue Mountain Revival

July 29 2023 Hoosier Hellfire

For more information visit www.precisionrifleseries.com

Ninnekah, Oklahoma

Kennerdell, Pennsylvania

Raton, New Mexico

Parma, Idaho

Finger, Tennessee

Rocky Mount, Virginia

Prosser, Washington

Evanston, Wyoming

Conway Springs, Kansas

Fort Pierre, South Dakota

Little Rock, Arkansas

Catskill, New York

Vernal, Utah

Butlerville, Indiana

SHOWDOWN

Medicine Lodge, Kansas

April 1, 2023

1st Place

MORGUN KING Open Div.

172.000/100.000

2nd Place

AUSTIN ORGAIN Open Div.

171.000/99.419

3rd Place (tie)

ANDY SLADE Open Div.

GREG HARRIS Open Div.

161.000/93.605

Soldiers from the US 4th Infantry Division move ashore at Utah Beach during the Allied retaking of France in 1944. (NATIONAL ARCHIVES)

STORY BY STEPHEN A. BOURQUE

Soldiers from the US 4th Infantry Division move ashore at Utah Beach during the Allied retaking of France in 1944. (NATIONAL ARCHIVES)

STORY BY STEPHEN A. BOURQUE

“I, Bill York (Aide), and Jas. K. Richards (Driver) landed, dry footed, by ‘Snowbuggy’ from the LCT [Landing Craft, Tank]. Some artillery fire (hostile), one half-track burning, and Co. A, 1st Amphibious Engineers digging in against seawall instead of doing their job of helping my troops across the beach. I rooted them out and onto the job with my pistol and cusswords. I learned later from York and Richards, who returned to the beach, that they went right back under the seawall as soon as I left.” –Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton

Despite the massive amount of literature describing every aspect of American performance in Normandy on June 6, 1944, historians have told us little as to what the commanders of the three American divisions (1st, 4th, and 29th Infantry) were doing after General Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered “the great and noble undertaking” of that fateful day. However, thanks to the discovery of Raymond O. Barton’s unpublished war diary, supplemented by other manuscripts and interviews, we better understand how the 4th Infantry Division commander spent the period immediately before boarding ships, crossing the English Channel, and during the battle on June 6.

By the time he arrived on Utah Beach, Barton had already spent 32 years in active service. He was Ada, Oklahoma’s 1908 high school valedictorian and a 1912 graduate of the US Military Academy. While at West Point, he earned the nickname “Tubby,” because of the solid build he developed on the wrestling mat and football field. It was a nickname he loved and he used it among, and when writing to, his friends. His

D-Day through the eyes of the US 4th Infantry Division's commander.Raymond O. Barton, shown here as a West Point cadet, circa 1912. (US MILITARY ACADEMY)

first assignment was with the 30th Infantry Regiment, serving in Alaska, San Francisco, the Plattsburgh, New York, training camps, and the Mexican border. His World War I service was in the United States, primarily in New York and Georgia, training officers on machine gun use and employment. Joining the 8th Infantry Regiment in Coblenz, Germany, in 1919, he served as part of the American occupation force at the end of the war. The Army commander, Maj. Gen. Henry T. Allen, acknowledged his performance and potential when he selected the young major to lead General John J. Pershing’s honor guard during his Congressional Medal of Honor presentation to the French and British Unknown Soldiers in Paris and London in 1921. His last act as commander of the 8th Regiment’s 1st Battalion was to supervise lowering the national flag over the Ehrenbreitstein Fortress in 1923, signifying the end of American participation in the First World War.

Returning to the United States, he traveled to Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and attended the Command and General Staff School, turning down a teaching assignment at West Point. The War Department then assigned the new graduate as G-3 of the Seventh Corps Area in Omaha, Nebraska. In addition to his training responsibilities, he supervised corps relief operations during the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. In 1928, he returned to the Command and General Staff School as an instructor of the two-year course, educating some of this nation’s most

senior future commanders. He and his family then moved to Washington, D.C., first for attendance at the Army War College class of 1932 and then, until 1935, as professor of military science at Georgetown University. His subsequent assignments were in Georgia, first as a military liaison to the Civilian Conservation Corps and then as commander of the 8th Infantry Regiment on Tybee Island. In 1940, he became the first chief of staff of the recently reactivated 4th Infantry Division, the “Ivy Division,” at Fort Benning and chief of staff, IV Army Corps, where he was assigned when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. During these last two assignments, he participated in the great series of prewar maneuvers in Louisiana and the Carolinas, serving with Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold, who would go on to command the XIV Corps in the Pacific. After a short period in early 1942, as assistant division commander for the 85th Infantry Division, Barton assumed command of the 4th Motorized Division at Fort Gordon, Georgia, the post he had helped to design while the division’s chief of staff. After an extensive training period, the War Department directed Barton to convert the Ivy Division back to a standard infantry division organization. In February, he led the division to England and continued training until D-Day. Unfortunately, part of his command suffered casualties during the German torpedo boat attack at Slapton Sands in April, before the invasion.

Most division commanders operated in a whirlwind of activity and danger. It is not surprising that few had the time to publish accounts of their combat experience, as did senior commanders such as Eisenhower, Omar N. Bradley and J. Lawton Collins. Fortunately, historians have been able to piece together the 4th Infantry Division’s operations, using daily operations journals and detailed division afteraction reports to provide a relatively accurate and complete narrative of the division’s actions. Each evening, Col. James S. Rodwell, the 4th Infantry Division chief of staff, and his deputies summarized the regimental reports and forwarded this document to the VII Corps headquarters. There, Col. Richard G. McKee, the VII Corps chief of staff, and his team prepared a corpswide summary with these reports for Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins, the corps commander. He extracted appropriate portions and sent them on to First Army headquarters. At the end of each month, the division staff compiled its reports, including information on personnel, intelligence, logistics, and operations, and sent this monthly history, through the corps headquarters, to the adjutant general in Washington. Historians also have copies of the orders and instructions Barton issued to his subordinates. Although this material has been available for years, seldom mentioned is the extended letter Barton wrote to Cornelius Ryan when the latter was writing The Longest Day (Simon & Schuster, 1959). Composed 10 years after the event, it identified most of Barton’s actions that critical day, along with the occasional personal confession or vignette. Finally, Barton’s recently discovered war diary, maintained by his aide Capt. William B. York, and other personal letters and documents, augment and elaborate on the information that has been available since the 1950s. As a result, we now have a relatively accurate picture of how he spent this historic day and the following weeks.

An aspect that needs to be addressed is the relationship between Barton and Brig. Gen. Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

Darryl F. Zanuck’s movie The Longest Day (1962) distorted what little the post-World War II generation knew about Tubby Barton and events surrounding this famous political and military personality.

In March 1944, Collins visited the division to watch Barton’s regiments training. Such visits were not unusual, as they happened at least once a week. However, this time, Collins had another issue: what to do about Ted Roosevelt? Roosevelt, son of the former president, had a distinguished record in the First World War, after which, he helped to organize the American Legion. When World War II began, this politically connected officer rejoined the active forces as a brigadier general. He became the 1st Infantry Division’s deputy commander and served with Maj. Gen. Terry D. Allen in North Africa and Sicily. An aggressive unit on the battlefield, Eisenhower and Bradley believed it was an ill-disciplined mob behind the front lines. As a result, Bradley replaced the division’s chain of command once the Sicilian fighting ended. After his relief, Roosevelt traveled to England, where doctors forced him to check into a hospital to treat his pneumonia. Roosevelt was not happy on the sidelines, however, and lobbied with everyone he knew to get back into the field. So, Collins came

down to 4th Division headquarters to tell Barton that Bradley had decided that Ted was now his and to use him as he saw fit.

Barton was not excited to get a possibly pretentious and arrogant president’s son as one of his subordinates, but he had little choice. He already had an assistant division commander in Brig. Gen. Henry A. Barber Jr., who had been with him for several months. Also in the command group was Brig. Gen. Harold W. “Hal” Blakeley commanding the artillery. Therefore, he did not need an extra general officer in his command without a defined role. Nevertheless, on March 25, Roosevelt and his aide, Lt. Marcus O. Stevenson, reported for duty. It turned out Barton’s assessment was wrong, and his diary notes that the two became good friends within a very short time. Roosevelt had more combat experience than almost any general officer in the European Theater of Operations. By the time he reported to the Ivy Division, his awards included a Distinguished Service Cross with a Bronze Oak Leaf Cluster, a Silver Star with three Bronze Oak Leaf Clusters, a Distinguished Service Medal for World War I courage, and a Legion of Merit. Because Barber was already his assistant, Roosevelt became an extra general on the division staff.

In this role, he visited units daily and reported his observations back to Barton at the end of the day. The division commander came to depend on the advice and mentorship this veteran could give him, and these nightly meetings became a standard occurrence in the months ahead.

From the time the VII Corps staff briefed its plan, Roosevelt pleaded with Barton to land on Utah Beach with the first wave. Finally, on May 26, not on the USS Bayfield as the movie depicts, but in Portsmouth after Montgomery’s commanders’ conference, he wrote Barton a formal request. In his letter, Roosevelt, a veteran of previous landings, laid out five reasons for going in with the first landing craft. He concluded with, “I believe I can contribute materially to all of the above by going with the assault companies. Furthermore, I know personally both officers and men of these advance units and believe that it will steady them to know I am with them.”

Barton had good reasons, none of them mentioned in the movie, not to allow “Rough Rider,” as Roosevelt often was called, to land at the beginning of the assault. From a practical standpoint, Col. James Van

Fleet was Barton’s most experienced and competent regimental commander and would be in charge during the assault. He did not require a general standing next to him when he made decisions and gave his battalion and company commanders orders. Generals did not land with the first wave for an important reason; they had to stay out of the way while their subordinates did their jobs.

Tubby also knew that Ted’s son Quentin was landing at the same time on Omaha Beach and did not relish the prospect of the father and son perishing during the invasion on the same day. It had nothing to do with The Longest Day’s insinuation that Barton wanted to keep him from harm because he was President Roosevelt’s son. He passed that danger threshold much earlier. If the letter had gone forward, there is little doubt that Collins, Bradley, and even Eisenhower would have supported the division commander. So, the letter, for the time being, went nowhere other than Barton’s desk, and he let Roosevelt go ashore.

Always good-natured about these things, Roosevelt respected his boss

and knew Barton was trying to do the right thing. Writing to his wife on June 3, Roosevelt noted: “Most generals are afraid to battle for what they believe with superiors who hold the power over their advancement. One of the reasons I’m so fond of Tubby Barton is that he is not. He will never, wittingly, let his men down.” The following week, as he watched Roosevelt get into his landing craft, Barton “never thought he would see him again alive.”

The division continued to load during the first three days of June, and Barton spent much time visiting his units, watching them load onto their LSTs (Landing Ship, Tanks) and other vessels. After a June 2 meeting at corps headquarters, he drove that evening to South Brent, England, his rear detachment headquarters. The war correspondents who were traveling with the division to France had gathered. It gave him a chance to meet personally the journalists accredited

to the division, who would connect his soldiers with their families back home. Henry T. Gorrell, the distinguished war correspondent for the United Press, would file the first report on Normandy’s invasion and later convey detailed accounts of the division’s progress across France. From CBS, Larry E. LeSueur would be with Barton and become an honorary member of the division. Kenneth G. Crawford, from Newsweek, would go ashore with Company C, 8th Infantry, and be in the heat of the fight from the beginning. Lastly, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Ira Wolfert, reporting for Reader’s Digest, would cross the channel with Barton. Tubby’s days in Omaha and with the CCC had prepared him well for working with the press. After the gathering, he then returned to the USS Bayfield for the evening.

The following day, Barton continued visiting the various loading areas and talking to the soldiers and their leaders. He started on Portsmouth’s west side, at the Tamar docks, and then

drove two hours east to Dartmouth, where he spoke to naval officers about the loading process. From there, he motored for an hour north to Torquay, where soldiers from the 3d Battalion, 8th Infantry, were boarding one of the transports. Already on board and crowding around the rails were soldiers from Company I. Riding with Barton and York was the former commander of that unit. When Barton arrived at the dock, he got out and moved toward the transport. However, when the soldiers on the ship saw their former commander, they all began booing and hissing. As he later told Cornelius Ryan, he was “almost sick at this unexpected and bitter greeting. He was so hurt that he did not know what to say or do.” It was not until much later that he learned the booing was for the captain, whom the soldiers disliked.

After this painful incident, he boarded a motor launch and spent the rest of the day riding the boat among the ships that carried his soldiers: the USS Dickman, the USS Barnett, and the HMS Gauntlet, the largest. He was now feeling much better, and at each stop, he gave a little speech and wished them all luck. He then sailed over to Col. Hervey A. Tribolet’s LST and spent some time with him and his staff. Finally, he returned to land, linked up with his driver and his sedan, drove to Victoria Wharf at Queen Anne’s Battery, and turned the vehicle over to

his quartermaster. He then boarded the USS Bayfield for the last time. Because of the weather, Eisenhower and his commanders needed to delay the assault by one day, so the 4th Infantry Division spent the day onboard their ships. On June 5, the USS Bayfield hoisted anchor at 0930, moved out of Plymouth, and joined its convoy heading for France. The scale of this undertaking is difficult to imagine. Each of Barton’s regimental combat teams required 13 Landing Craft, Infantry, six LCTs, and five LSTs. Each vessel towed a barrage balloon to deter air attacks. Cruisers and destroyers protected the flanks of the moving convoy. Somewhere in the channel, an Allied fighter shot down a German plane as it approached the convoy. The Bayfield’s crew heard the report and used the public address system to let everyone onboard know that the shooting had begun. The convoy was Task Force 125, and its crossing was not without incident. The vessel carrying a battery from the 29th Field Artillery Battalion hit a mine as it approached the shore, causing its entire complement of guns and prime movers to sink to the bottom of the channel. It is doubtful that Barton noticed a young gunner’s mate, Peter Berra, performing his crew duties. After the war, “Yogi” Berra would become one of the greatest ballplayers of all time and remain a staunch supporter of service members for the rest of his life.

Although Barton would spend almost 165 days in combat, it was the first one that, in many ways, was the most important. By now, Barton had nearly two full years of training and leading the division – more than that when including his time as chief of staff and 8th Infantry commander. He had supervised its preparation for combat in extensive exercises in the Carolinas and in amphibious training in Florida and England. He knew all of the division’s senior officers and most of the company commanders personally. Few American units would be as prepared for its first day of battle as the Ivy Division. Yet, after 32 years in uniform, this was his first taste of actual combat. Barton told Cornelius Ryan that he constantly fretted about becoming so afraid that he would freeze and fail as a combat leader. On June 6, he would discover which was more robust: his natural human fear, or character developed in decades of preparing for this day.

Like almost all commanders, there was little Barton could do that night or morning. Colonel Van Fleet’s 8th Infantry Regiment would lead the assault. A football player and coach and aggressive by nature, he was the right leader to drive his troops forward to link up with the 101st Airborne Division that landed the previous evening. Next in was Colonel Tribolet’s 22d Infantry. A caring and

methodological commander, Barton thought he would do well rolling up the German fortifications on the coast. Finally, the newest commander and another football coach and player, Col. Russell P. “Red” Reeder, would lead the 12th Infantry through the gap between the other two regiments to expand the bridgehead.

After Van Fleet’s troops headed to the beach, Barton watched as the 22d and 12th Infantry formed up and headed to shore. Colonel Reeder later remembered the radio call before climbing into his landing craft: “Cactus to Cargo, come in.” Reeder responded to Barton: “Come in Cactus.” Then: “Good luck, Red.” General Barber was moving slower than planned that morning and pulled up alongside the Bayfield at 0625, asking Barton if the assault waves had moved on time. The commander’s short reply was yes, and his deputy headed off to shore. Barber would join

up with Tribolet’s 22d Infantry on the right flank, moving north and through the German coastal defenses.

Four companies from the 8th Infantry Regiment, hit the beach precisely at 0630. Roosevelt went in with Company B on the right and began coordinating the advance of its two assault battalions: Lt. Col. Conrad C. Simmons’s 1st Battalion and Lt. Col. Carlton O. MacNeely’s 2d Battalion. Within a few minutes on the beach, the two battalion commanders began telling Roosevelt that the actual beach terrain bore little resemblance to the sand tables and maps they had been pouring over for months. While the battalion leaders got their troops productively engaged in battle and moving forward, the brigadier had time to survey the battle area. The veteran of previous assaults realized they were in the wrong place. He got his bearings, located where they should be, and moved from one commander to

another, orienting them on their actual locations. He instructed MacNeely and Simmons to clear German troops from the strong points to their front and then head toward their original objectives. At 0915, Van Fleet arrived with the 3d Battalion, and Roosevelt updated him on the situation and his decisions. The regimental commander concurred and the follow-on units received instructions to follow the 8th onto the modified landing site. Both Van Fleet and MacNeely emphasized in their reports that Roosevelt was under machine gun and artillery fire during the entire period he was moving across the beach. They were impressed with his poise under fire and effectiveness as a leader. As the veteran among the group, he was the one who decided on the preferred course of action. Soldiers remember Roosevelt walking around the beach, poking soldiers with his cane and yelling “Get out of here! If we’re going to get killed, we’re going to get

killed inland.” Unfortunately, Simmons would die in action on June 24, so we have no report from him on what he observed during the landing.

As a lieutenant with the 22d Infantry,

Bob Walk served as a liaison officer between his regiment and division headquarters. He was on the LCT that served as the vessel for the liaison and radio jeeps and other vehicles from the headquarters command group. This cramped boat also served as Barton’s

command post as the fight began. Bouncing alongside the Bayfield, Barton used the hood of Walk’s jeep as the table for his situation map. There, he listened to the reports from shore and monitored the action. According to the G-3 Journal, communications

between Barton and his key leaders appeared to be excellent. Walk remembered Van Fleet’s reporting that everything was under control, and in fact the two leaders spoke at 0635 and again at 0650. Interestingly, there are no entries in the operations journal indicating that the landing location had changed early that morning. The June after-action report also says nothing about changing the location. Most likely, this veteran organization just took this friction in stride and continued to operate.

By 0904, the 22d Infantry was ashore. Barton now had three regimental commanders, two deputy commanders, and his artillery commander on the way or on the beach. He could wait no longer. Bob Walk remembers Tribolet,

his regimental commander, calling in and reporting that everything was going according to plan. After that report, he heard Barton say: “That’s enough for me, let’s go.” At 0900, he left the Bayfield for the beach.

At 0934, he reported his arrival on the beach. As quoted at the beginning of this article, he, Jason K. Richards, his driver, and Capt. William B. York, his aide-de-camp, arrived on the shore in their M29 Cargo Carrier – he referred to it as the “Snowbuggy,” but soldiers called it the Weasel. It did not go far, as his driver mired it in the sand with a broken track. Barton jumped off the vehicle and moved to shore on foot. Bill York directed Pvt. John Sears, driving another M29, to go back to the beach and gather Barton’s gear and maps and

bring them to the general, which he did. Sears was supposed to be General Barber’s driver, but because he was late and did not land with the early waves, he had a utility role that morning.

Barton later admitted he was terrified, as the sounds of weapons fire were all around him. A German artillery shell exploding nearby only increased his concern. He encountered the engineers behind the seawall, noted at the beginning of this article, and continued moving inland. He did not go far, but found a house with a high, brickwalled courtyard on the dunes. Most likely, this was just south of the postwar Utah Beach Museum. Meanwhile, the German artillery was increasing its fire rate, and anyone on the beach was a potential casualty, so the house

gave some protection. By radio, he contacted his deputies and regimental commanders; all reported things were on track. At 1025, one of the deputies, probably Roosevelt, reported that they had landed “5,100 yards from the main objective.” This was the first note in the division reports acknowledging the change. Barton is quite open that there was little he could do at this point. His regimental commanders had a plan, and Roosevelt and Barber were

on the ground making the needed adjustments. He had a reasonably good understanding of the landing’s progress and saw no need to make any changes.

Barton sent out liaison officers and others to find out the situation around him. Lt. Joseph Owen remembered that at about 1100, Barton sent him toward Sainte-Mère-Église to find the exact location of the 8th Infantry Regiment. On his way, he remembered running into Roosevelt,

who slowed down his jeep to yell out, “Hey Boy, they’re shooting up there,” followed by a big “Haw Haw.” One constant among 4th Infantry Division soldiers that morning was Roosevelt’s ubiquitousness. He ranged across the entire beach area without any fixed responsibilities, advising, coordinating, and keeping things moving. Owen found Van Fleet, and the colonel instructed one of his officers to mark the battle map for delivery back to Barton.

By noon, his battle staff and those who landed to assist during the early hours of the invasion began to join him. One of the first was Lt. Col. Dee W. Stone, the G-5 (Civil Affairs and Military Government), who had found Maj. Philip A. Hart, one of his temporary staff officers, severely wounded at the water’s edge. The amphibious engineers present (under the seawall’s shelter) refused to help Stone rescue Hart from the advancing tide, but he was able to move the wounded officer to safety. Then Lt. Col. Richard S. “Dick” Marr, the G-4, and Capt. Parks Huntt, his headquarters commandant, arrived, reported, and began moving toward

the planned headquarters site. Subsequently reporting in was Col. James E. Wharton, the 1st Engineer Special Brigade commander and the senior commander for the soldiers Barton encountered at the seawall. As Barton notes in his letter to Cornelius Ryan: “The colonel took the trouble to inform me that his men were not the only ones quitting their missions at the seawall but that some of mine had done the same – in the beginning that was true but Ted Roosevelt cured that.” One suspects the division commander let him know how he felt.

While at the beach house, Barton says he had little idea as to what was going on: “I was in a semi fog. No contact nor communications with anyone but those present ... About a mile off our planned landing point. No idea of where nor how my assault battalions were, except that I did know they had taken their beach and gone

on inland.” This is not exactly true, as the G-3 Journal clearly indicates he had reasonable communications and was in contact with his leaders. It might not have been to his standard, but he was not out of the fight. His most important contribution that morning was when commanders of the attached units found him and asked if he had any instructions. In every case, he said: “No; just go ahead on your job per plan.”

Around 1300, Barber’s aide found Barton and guided him to the temporary command post. This impromptu collection of vehicles and staff officers was just south of Causeway 2, directly opposite the modern Utah Beach Museum and across from Marker 1 on the Voie de la Liberté. There, Lt. Col. Orlando C. Troxel (G-3) and Lt. Col. Harry F. Hansen (G-2) and their small staffs were at work monitoring the combat team’s progress. Now, by early afternoon,

Barton was beginning to gain control or at least good situational awareness of how the regiments were doing. Dick Marr reported that the infantry had crossed the low ground the Germans had flooded and were making good progress inland. All reports indicated that everything was generally going according to plan. There was little Barton could do; he had to let the commanders do their jobs. However, he noticed that many of the following units were backing up on the causeways and having trouble moving inland. Tubby could see that Causeway 2 (U5) was bumper-to-bumper with vehicles and not moving. Without intending to, GIs performing their assigned local duties made it difficult to get the division’s combat power forward into the fight. Engineers improving the route, antiaircraft guns, and wire teams were all making movement difficult. Therefore, Barton and Marr went to

the traffic jam, looked at the situation, and ordered everything nonessential off the road. Some vehicles also had broken down, blocking the road. Barton had soldiers move anything in the way off the trail and into the swamp. Once traffic across the causeway was flowing, troops would spend the rest of the night pulling the unfortunate broken-down vehicles out of the mire.

Troxel received reports that the division had captured Causeway 3 (T7) just to the north, and it was open for use. Nearby, Lt. Col. C. G. Hupfer’s 746th Tank Battalion was still near the landing area. Barton wanted it off the beach and to its next position near Audouville-la-Hubert. Because of the congestion in front of him, he began developing an alternate route for the armor, using the reportedly open road. In the middle of all that confusion, around 1500, Roosevelt arrived at the temporary command post. They joyfully embraced each other. Then, of course, Teddy wanted to talk. Barton later noted: “He was bursting with information (which I sorely needed) –but wouldn’t let him talk.” He was under pressure to get the tank battalion into the fight. He later noted: “Try some day to keep a Ted Roosevelt from sounding off if he wants to – but I did.”

In the middle of all of this, his aide Bill York interrupted the proceedings and notified his boss that some Associated Press photographers wanted pictures of the division commander. “Reluctantly and irritably,” he consented. It broke his chain of thought and the photographers took their time in taking the photos. Barton was “mad as hell” because the only thing he

wanted to do was get the tanks on the road and talk to Ted. Finally, the photographers departed, and Barton later cherished the photographs. Hupfer got his orders and returned to his command, and now Barton and Roosevelt could catch up.

It was around 1900 when Barton arrived at Blakeley’s headquarters. For the first time since leaving the Bayfield, he had good communications and could contact his regimental commanders by radio. Nearby, Capt. Parks Huntt began to establish the division’s operations center. Barton went over to see how things were going. Huntt, who was always proper in his military bearing, came over to the general, raised his arm to render a salute, and immediately tumbled to the ground. He got to his feet, again tried to salute, and fell again. Barton, who had been extremely tense and fearful of his first combat experience for the last two weeks, broke into laughter as artillery shells exploded around them. Apparently, one nearby explosion temporarily affected his headquarters commandant’s equilibrium and raising his arm had the effect of knocking him off his feet. Barton helped him up and said: “Forgive me, Parks, but you looked so damn silly wheeling around that I couldn’t help laughing, why don’t you lie down for a bit.” Barton reported to Ryan that his fear of battle never affected him again. He walked over to the intersection and found Van Fleet (Combat Team 8), watching some of his troops load a soldier into an ambulance. Barton was anxious to get on with his tasks but came over to talk with his commander.

Just then, a tall, distinguished-looking Frenchman, in coat and knickers, came up to them waving a marked map and excitedly trying to tell them something. Van Fleet had to leave, and Barton remained with the civilian, whom he could not understand but turned out to be a retired army colonel. He was trying to convince Barton that a German artillery battery was close by, but Tubby had recently walked by that location and saw nothing. After politely saying goodbye, he walked over to Rodwell, who had recently joined the command post group. Just then, a report arrived confirming the French colonel’s warning. He told his chief “to run out to the road, grab the first combat outfit he found and have it go take the hostile battery.” Rodwell found an element of an antitank battalion going into bivouac and grabbed some of its infantrymen. He was back soon with the report, “mission accomplished with ease.” Around 2100, it was still light in this northern part of the world in June. There was still little Barton and Blakeley could do to influence the battle until the command posts were operational and the staff began processing the unit reports. The infantry was settling into its evening positions, and the artillery batteries were repositioning to best support them. Therefore, Barton and Blakely decided to inspect the piece of France that now belonged to the 4th Infantry Division. With Sergeant Richards still driving the M29 Weasel, he and York headed out to visit a captured German artillery battery nearby at Saint-Martin-de-Varreville. The Ninth Air Force had done a good job taking it out, as it was in a position to have hurt Barton’s assault battalions.

Unlike the Eighth Air Force’s heavy bombers that failed to destroy the German fortifications on Omaha and the other beaches, the medium bombers of the Ninth were precise. Their accurate air attacks had prevented enemy gunners from interfering with the landings and inflicting casualties on the American troops. They drove around looking at some of the other positions, and near Causeway 4 (S9), the farthest north, Barton’s vehicle threw a track around 2330 as it was getting dark. Not able to repair it on the spot and located right along the front lines, Barton and York climbed into Blakely’s vehicle. The general assured Richards that they would send help. According to Barton, Richards did not say a word, but after the war told him, “he never felt so lonely, nor scared.”

Sometime after 2330, Barton and Blakely arrived at the headquarters at Audouville-la-Hubert, where Rodwell had the staff operating. He gave Barton an overview of his division’s status. From the beginning, the landing had gone well. Frankly, it is incorrect to

say that no plan survives first contact with the enemy. An operation plan is nothing more than a scripted series of events that provide leaders with the direction for the opening phase of an operation. In this case, the nature of the region’s currents and the loss of one of the naval control vessels caused the first wave to land south of the intended landing area. It turned out to be a brilliant stroke of luck as the German defenses were weaker than the original sector. Once ashore, the leaders went about their business as if on another practice exercise. Everything that happened in those first few hours reflected on the division cadre’s high level of preparation. Generally forgotten in most narratives is the division staff’s role in ensuring that the regiments were as prepared as possible to handle the friction of battle. Rodwell and his crew monitored the enemy situation and the infantry battalions’ progress while working behind the scenes away from photographers and journalists. They established the command post

late in the afternoon and early evening and established radio contact with subordinate units. Now they could verify their situation and, if required, supply them with what they needed. First on the ground, and then by radio, they connected with the 82d and 101st Divisions and began planning to organize the beachhead. Finally, they maintained contact with Colonel McKee and the VII Corps staff, still afloat, keeping him apprised of the division’s situation and requirements. When the division commander returned to the headquarters that night, Rodwell could give him the update he needed to make decisions, get his guidance, and start preparing orders to guide the fight over the next few days. Writers generally ignore the chief of staff’s role in most historical accounts, but he is as vital as any regimental commander, just not as noticeable. Barton was satisfied with how things went that day. He told Rodwell that night, “things are good; I think we made it.” By nightfall on D-Day they “were ashore, well inland,

an intact operational division – and now proven veterans.”

Barton’s last act of June 6 was to gather his regimental commanders outside his command post. Someone had liberated a few bottles of champagne, and the commander shared them with Rodwell, Blakeley, Barber, Roosevelt, Tribolet, Van Fleet and Reeder, so they could “drink to the health of the best division in the army.” He began the day after his commanders had arrived and by the end of the day had regained control of his division. Barton’s fears of falling in battle had not materialized. However, using a football analogy, it was only the first series of downs and it would be a long game. Over the next three weeks, the division would claw its way north, fighting intense but generally forgotten battles at Crisbecq, Montebourg, Bois du Coudray, La Glacerie and the eastern side of Cherbourg.

By the end of June, Barton’s division had been in continuous combat for over three weeks and would have little

rest before it headed south back into the bocage near Carentan. During this intense three weeks of combat, the division lost 5,400 soldiers killed, wounded or captured – almost 40 percent of its authorized strength. Most of these losses took place in the three line regiments. Only five of the rifle company commanders who had made the D-Day landing were with the division three weeks later. Fortunately, many officers and newly promoted noncommissioned officers remained to steady the 4,400 replacements who partially refilled the division’s ranks.

Among those missing at the end of June were some of the division’s key leaders. Barton’s deputy, Henry Barber, had worn himself out and would soon be on his way back to England. Barton lost all three of his regimental commanders. Although a great trainer, Hervey Tribolet, failed the test of battlefield leadership, and was simply too close to his soldiers. Collins and Barton had to relieve him and send him to army headquarters. James Van Fleet received a well-

deserved promotion to brigadier and a new assignment, with Jim Rodwell taking his place. Probably the most heartbreaking for Barton was Red Reeder’s wounding and evacuation after only a few days of combat. The intense fighting killed four battalion commanders: Dominick P. Montalbano (2d Battalion, 22d Infantry), Thaddeus R. Dulin (3d Battalion, 12th Infantry), John W. Merrill (1st Battalion, 12th Infantry), and Conrad C. Simmons (1st Battalion, 8th Infantry). Seven out of his 12 frontline infantry combat commanders were gone. At the same time as Rodwell’s departure to the 8th Infantry, Collins took his G-3 Orlando Troxell and moved him to the same role at corps headquarters. After only three weeks of combat, Barton lamented: “We no longer have the division we brought ashore.” Ted Roosevelt would continue to mentor him for the next five weeks before suffering a heart attack. By then, Barton was a veteran commander and would continue to lead the division until his health gave out at the end of December. For Barton, D-Day was probably one of his best days in combat. ★

Editor’s notes: This story appeared in the Fall 2022 issue of Army History and is reprinted with permission from US Army Center of Military History. Dr. Stephen A. Bourque retired from the US Army after 20 years of enlisted and commissioned service in 1992. He earned a PhD at Georgia State University in 1996 and has taught at several civilian and military colleges. He retired as professor emeritus from the Army’s School of Advanced Military Studies in 2017. His most recent publications include D-Day 1944: The Deadly Failure of Allied Heavy Bombing on June 6 (Osprey, 2022) and Beyond the Beach: The Allied War Against France (Naval Institute Press, 2018). The French edition, Au-delà des plages: La guerre des Alliés contre la France (Humensis, 2019), received the Grand Prize in Literature from the l’Aeroclub de France in 2020. Bourque is completing a biography of Maj. Gen. Raymond O. “Tubby” Barton.

It’s just 24 notes, but the military bugle call has a deep, rich history.

STORY BY DANIELLE BRETEAU

STORY BY DANIELLE BRETEAU

The story and origin of the bugle call known as “Taps” can be found in many versions, including the legend of a son fighting on the opposing side of the Civil War from his father. This legend depicts a Northern boy who was killed fighting for the Confederates. His father, Robert Ellicombe, a captain in the Union Army, came upon his son’s body and found the notes to “Taps” in the pocket of the dead boy’s uniform. When Union General Daniel Sickles heard the story, he had the notes played at the boy’s funeral. While this very short version of the legend is deeply meaningful to anyone who reads it, historical documents show us another story.

According to tactics manuals of the time, as well as letters on record, “Taps” was a modified version of a previously known Scottish “tattoo.” The term tattoo was originally a form

of military music. The tattoo titled “Extinguish Lights,” meaning lights out at the end of the day, was played each night for the troops even before the Civil War and was borrowed from the French. This is documented in Silas Casey’s (1801-82) tactics manual, among others of the time. The song was even referred to as the “go to sleep” song by the soldiers.

To look back even further into history you will find that the word tattoo was most likely derived from an early 17th century Dutch phrase “doe den tap toe,” meaning, “turn off the tap.” This signal, sounded by drummers or trumpeters, instructed innkeepers near military garrisons to stop serving beer and for soldiers to return to their barracks.

Union General Daniel Butterfield (Third Brigade, First Division, Fifth Army Corps, Army of the Potomac) is credited with writing “Taps” as

Day is done, gone the sun, From the hills, from the lake, From the sky.

All is well, safely rest, God is nigh.

Go to sleep, peaceful sleep, May the soldier or sailor, God keep.

On the land or the deep, Safe in sleep.

Love, good night, Must thou go, When the day, and the night Need thee so?

All is well. Speedeth all To their rest.

Fades the light; And afar

Goeth day, and the stars

Shineth bright, Fare thee well; day has gone, Night is on.

Thanks and praise, For our days, ’Neath the sun, neath the stars, ’Neath the sky, As we go, this we know, God is nigh.

we know it today, and according to a series of letters, “Taps” was a modified version of this previously known and used tattoo. One of the letters on record depicts how General Butterfield used his version in battle: “I had composed a call for my brigade, to precede any calls, indicating that such were calls, or orders, for my brigade alone. This was of very great use and effect on the march and in battle. It enabled me to cause my whole command, at times, in march, covering over a mile on the road, all to halt instantly, and lie down, and all arise and start at the same moment; to forward in line of battle, simultaneously, in action and charge etc. It saves fatigue. The men

rather liked their call, and began to sing my name to it. It was three notes and a catch. I cannot write a note of music, but have gotten my wife to write it from my whistling it to her, and enclose it. The men would sing, ‘Dan, Dan, Dan, Butterfield, Butterfield’ to the notes when a call came. Later, in battle, or in some trying circumstances or an advance of difficulties, they sometimes sang, ‘Damn, Damn, Damn, Butterfield, Butterfield.’”

If you read further, General Butterfield mentions he solicited the help of someone who could actually write music, although he could also play the bugle, as that was an important duty of his position. Butterfield lengthened some notes and

shortened others until he achieved the sound that he felt was appropriate. It is said that buglers from surrounding camps, after hearing Butterfield’s bugle calls, would come and ask for the tune, which he freely shared.

Author’s note: There are many thoughts on the origin of “Taps.” I would like to thank Jari A. Villanueva, who is a bugler and bugle historian. A graduate of the Peabody Conservatory and Kent State University, Villanueva was the curator for the Taps Bugle Exhibit at Arlington National Cemetery from 1999-2002. He has been a member of the United States Air Force Band since 1985 and is considered the country’s foremost authority on the bugle call of “Taps.”

a laboratory at Joint Base Pearl HarborHickam in Hawaii, where it was analyzed. On March 1, 2021, the remains were identified as Commander Charvet.

According to Captain McMahon, the families of identified soldiers can choose to have their loved one re-interred at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth or an alternate location, such as a veterans’, private family site or Arlington National Cemetery.

ANavy pilot who was reported missing in action during the Vietnam War has finally been laid to rest, 56 years after his disappearance. A native of Grandview, Washington, Commander Paul Claude Charvet was brought home and buried alongside his parents in April at a Yakima cemetery.

According to the Navy Office of Community Outreach, Charvet’s final flight took place March 21, 1967.

“... Lt. Charvet piloted a single-seat A-1H Skyraider assigned to Attack Squadron (VA) 215 aboard the USS Bon Homme Richard (CV-31) as a member of a three-plane flight performing a coastal reconnaissance mission for naval gunfire ... During the mission, the USS Canberra requested that the flight perform reconnaissance near Hon Me Island, Thanh Hoa Province, North Vietnam. As the flight made a turn over the island to mane visual confirmation of a waterborne craft, visual contact with Charvet’s aircraft was lost. Attempts to contact Charvet by radio were unsuccessful, and search and rescue teams could not locate him or his Skyraider. On Dec. 2, 1977, his status was changed from Missing in Action to Presumed Killed in Action, and he was posthumously promoted to Commander.”

The Navy works to identify remains

through a process using DNA samples from family members and other evidence.

“The DNA profiling process begins with a sample of an individual’s DNA, typically called a ‘reference sample,’” explained Captain Robert McMahon, Director of Navy Casualty, who oversees the processes for family visitations, transport of the deceased, and coordination of the burial. “During Project Oklahoma, the Navy reached out to families via letters and phone calls requesting their participation in the Family Reference Sample Program in efforts to possibly make a positive match, and identify their loved one.”

In the fall of 2020, the US government received human remains and additional material evidence from the Vietnamese government. The evidence was sent to

“The Navy pays for funeral expenses, family travel and lodging for up to three blood family members to the service member,” said McMahon. “All funding/ entitlements are handled and processed by the Navy Casualty office. Entitlements include casket, remains transportation, funeral home expenses and cemetery expenses. The Navy provides full funeral honors (rifle salute, burial team and ‘Taps’) details.”

Commander Charvet was laid to rest Friday, April 14, near his hometown. Among the attendees were Charvet’s family, as well as veterans, community members and others wishing to pay their respects to a pilot who lost his life fighting for his country. In addition to a Purple Heart, Commander Charvet received several posthumous awards for his bravery. This quote is from his Distinguished Flying Cross citation:

“As a combat flight leader, his 147 combat missions, totaling 533 combat hours, contributed significantly to the United States’ military efforts. He skillfully and courageously led Attack Squadron 215 aviators in the execution of such varied combat missions as close-air support, strike operations, coastal and inland reconnaissance, land and sea air rescue, helicopter escort, interdiction and naval gunfire support missions [that] resulted in substantial damage or total destruction to his assigned targets. His devotion to duty in the face of enemy fire under hazardous flying conditions was in keeping with the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.” ★

Remains of Navy pilot missing in action in 1967 and identified in 2021 were buried this spring.Commander Paul Claude Charvet. Distinguished Flying Cross. PHOTOS COURTESY NAVY OFFICE OF COMMUNITY OUTREACH

Billy Waugh fought in Korea and Vietnam, was a CIA operative, hunted Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan and much more during a truly remarkable career spanning decades.

STORY BY PAUL PAWELA

STORY BY PAUL PAWELA

was recently attending Sean Kelley’s kenpo camp – Kelly is one of the greatest kenpo karate instructors in the world and his seminars bring in the very best – and in the back of my mind was my father’s wisdom: “Always train with the best and keep your pie hole shut.” Airborne, Pops! And check! However, this camp was even more special than the previous ones, as there were many mentors in attendance.

One such mentor was Special Forces/Ranger legend and Chief Warrant Officer 4 Patrick Kelly, a man who deserves an article written about him. With a calm but thunderous voice from the mountain of a man that he is, Kelly braced me for some bad news: “Paul, on my way down from Bragg, I stopped by Tampa to visit Billy. He is not going to be with us much longer.”

I was subsequently informed through the grapevine that Billy Waugh, the Special Forces/CIA luminary, a man whose entire life could fill volumes and whose story is worthy of a major motion picture, was felled by two major strokes. As sure as he was a Christian of faith, Waugh was given his orders to report to the Lord on April 4 of this year. Born William Dawson Waugh, he was 93.

THIS IS MY requiem to the immortal superhero Billy Waugh. I debated whether to compare him to Odysseus/Ulysses, the hero of Homer’s The Iliad and The Odyssey, but the more I thought about it, I realized that the character Batman was more fitting. Not only could Batman have been certainly modeled after Waugh, but they have more in common than one would think. If you think it is a bit childish, then tell that to the CIA, who gave him the code name Batman!

Let’s start the comparison. Batman has genius-level intelligence, masterful detective and escapology skills, peak human physical condition, martial arts expertise, access to hightech equipment, and he is a superhero who fights evil and strikes terror in the hearts of criminals. Having no superhuman abilities, he is considered

one of the world’s most intelligent men and greatest fighters using his physical prowess, technical ingenuity and tactical thinking. Part of his crime-fighting gear is his utility belt in which he carries an assortment of weapons and investigative and technological tools. Despite having the potential to harm his enemies, he has a strong commitment to justice and a reluctance to take a life. Batman deliberately cultivates a frightening persona to put fear into his enemies. He would best be described as a polymath.

In an eerily similar comparison, Waugh lived every word as described above, except with one incredibly huge difference: he had no such reluctance to take lives. In 50 years of combat experience, both with elite Special Forces units and the CIA, as he saw it, “My craving is, and

always has been, to be involved in actions conducted to ensure America remains strong, safe, and free of those who have its destruction as their goal.”

After the events of September 11, 2001, his thoughts on Osama bin Laden were these: “By God, this man and his Al-Qaeda punks needed to be killed and tossed into the garbage dumps of wherever they may be found.”

At the age of 71, Waugh set out with a few CIA, Delta Force and Special Forces Operational Detachment Alpha 594 members to capture or kill bin Laden. Each operator carried 110 pounds of equipment, complete with a filled rucksack, communications equipment, weapons and grenades, and they embarked on the roughest mountain terrain Afghanistan had to

In addition to his eight Purple Hearts, Waugh received the Silver Star (the third-highest medal in the military), four Commendation Ribbons for Valor, four Bronze Stars for Valor, 14 Air Medals for Valor, and two Combat Infantry badges.

Speaking of valor, Waugh and a team of two other men that he picked were the first to do a high-altitude low opening, or HALO, parachute combat jump. Think about the incredible courage it takes to step out in the darkness of night, 2 miles above Earth and 2 miles above the most uncharted, vicious jungle man had ever seen, and Waugh and his team were jumping right into the middle of it! Waugh would be cemented as a pioneer in the HALO field, serving all future special operations HALO teams fighting in the Global War on Terror.

offer, often in miserably cold weather with temperatures plummeting to -5 degrees. Using advanced technology, those heroic men brought in enough laser-guided bombs from the US Air Force to exterminate a large population of terrorists.

THROUGHOUT HIS INCREDIBLE career, Waugh lived with pain and suffering. He was awarded eight Purple Hearts, which meant he was wounded by either bullets or bomb shrapnel multiple times.

During one secret mission, Waugh was shot in the foot, ankle, knee, wrist and head. The North Vietnamese Army enemy thought he was dead – big mistake – but he literally willed himself back to health after extensive reconstruction on his injured leg that doctors thought might have to be amputated. Be it willpower, divine intervention, or both, in a relatively short time, Waugh was back in the fight.

By the way, on that mission, deep behind enemy lines, Waugh and his team killed more than 160 enemies. That attack alerted over 4,000 NVA

troops to hunt down Waugh and his team of 90 men. Only 18 of his men made it out; however, when the survivors called in for air support, over 600 NVA had been killed.

In the secret unit called SOG (Special Operations Group), Waugh was not only known for taking lives, but part of his mission was to save lives and recover bodies of men killed deep behind enemy lines. He led many successful missions, which are talked about in-depth in his book Hunting the Jackal, as well as in SOG: The Secret Wars of America’s Commandos in Vietnam by John Plaster.

While most of his jumps were successful, Waugh did survive crashing in three helicopters and two planes.

IT IS HARD to believe that Waugh’s first combat experience was in 1951 in Korea, and that just two years later in 1953, he would become a pioneer in the Special Forces. Waugh’s last mission was in Afghanistan in 2002. In all, he served the US in 64 different countries. Many of his CIA missions are classified to this day.

During the Vietnam War, Waugh’s SOG unit, which he was in for over seven years, captured thousands of tons of munitions and supplies and killed thousands of enemy soldiers.

SOG recon men consistently killed more than 100 NVA for each one lost, a ratio that climbed as high as 150 to 1. This was the highest documented kill ratio of any American unit in the war and probably the highest such ratio in US history.

A short time later, Waugh was part of the undercover CIA team that was responsible for capturing the number one terrorist at that time, Carlos the Jackal, also known as Ilich Ramírez Sánchez. It was Waugh’s great detective prowess that allowed him to be the first person in the world to get updated pictures of the Jackal that were used in capturing him.

Another target that Waugh had his eye on was bin Laden. Waugh had done secret surveillance on the terrorist, and had asked permission several times to kill him. Waugh told me personally that he had gun sights on bin Laden many times and could have killed him relatively easily. The

plan I liked the most was the one he wrote about in Hunting the Jackal. When bin Laden was being driven out of town, a two-car team would be used; the first car would smash into bin Laden’s vehicle and the CIA operators in the other car would shoot bin Laden’s driver and bin Laden with suppressed MP-5s. But like many politicians who are squeamish about eliminating threats to Americans, the administration at the time would not authorize kill missions until many Americans died – and die they would by the thousands at the hands of bin Laden. That included the bombings of two US embassies in East Africa, a bombing at Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia, attack on the USS Cole in Yemen, the Battle of Mogadishu (also known as the Black Hawk Down incident) and the September 11 attacks. Those buildings would all still be standing and many thousands of lives would have been saved had Waugh

been authorized to shoot that SOB.

Waugh lived by the mantra: “If a man prepares for battle, trains for battle, studies the enemy, and practices for every possibility, the outcome of the battle will take care of itself.”

How good was Waugh? Hanging in his house are many plaques that are definitely museum-worthy. However, the one that stands out the most is the one the CIA presented to him that reads: “To Billy Waugh from the CIA, ‘The Greatest Assassin Ever!’” I think that sums it up best.

Thank you always, Billy, for being a true leader and mentor to us all. Billy Waugh is the greatest man ever to be known as Batman – God bless and goodbye. ★

Editor’s note: Author Paul Pawela is a nationally recognized firearms and self-defense expert. For his realistic self-defense training, see assaultcountertactics.com.

GUN SAFETY SEMINAR NRA seminar introduces new gun owners to gun safety fundamentals

RUN YOUR GUN One on one firearms coaching with Christopher

RANGE SAFETY OFFICER NRA Range Safety Officer (RSO) Certification

NRA EDDIE EAGLE GUNSAFE® PROGRAM

NEW GUN OWNER The NRA Basics of Pistol Shooting course

PREPARE TO CONCEAL NRA Concealed Carry Weapon (CCW) Certification

FIREARMS IN THE HOME NRA Personal Protection In the Home Certification

FIREARMS OUTSIDE THE HOME NRA Personal Protection Outside the Home Certification

LONG GUN NRA Basic Rifle for basic and skill based learning with a long gun

BASIC SHOTGUN Basic shotgun for basic and skill-based learning with a shotgun

That is the mission of Wreaths Across America, a nonprofit best known for its annual wreath-laying ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery and around the country.

Founded in 2007, WAA actually had its beginnings about 15 years earlier in Harrington, Maine. That is when Morrill Worcester, owner of Worcester Wreath Company, discovered that he had a surplus of wreaths at the end of the holiday season. Inspired by a boyhood trip to Arlington National Cemetery, he realized he had an opportunity to honor our country’s veterans. So a wreath-laying ceremony was organized at the military cemetery, with the aid of Maine US Senator Olympia Snowe, along with help from local volunteers and a nearby trucking company that transported the wreaths to Virginia.

The ceremony quietly became an annual tradition, taking place every December. Then, in 2005, a photo of the wreath- and snow-covered stones went viral, and the project quickly received national attention from people wanting to help – as well as those wanting to emulate the project at their local cemeteries. In 2006, simultaneous wreath-laying ceremonies were held at over 150 locations across the nation.

As the Arlington ceremony continued to grow and spread across the country, the Worcester family and their partners formed the nonprofit 501(c)(3) organization known as Wreaths Across America. According to the WAA website, “It became clear the desire to remember and honor our country’s fallen heroes was bigger than Arlington, and bigger than this one company.”

In 2014, WAA and its national network of volunteers laid over 700,000 memorial wreaths, including covering Arlington with 226,525 wreaths. Ceremonies were held at 1,000 locations that year, including at the Pearl Harbor Memorial, Bunker Hill, Valley Forge and the sites of the September 11 tragedies.

How a Maine company's surplus Christmas wreaths spawned an annual tradition honoring America's fallen soldiers, a program thanking veterans for their service, and much more.

After growing up in the Bahamas, Sidney Poitier moved to New York City. He was so overwhelmed by life in the big city that he lied about his age to join the Army and served as an orderly in a military hospital on Long Island.

After embarking on a career as an actor, Poitier started a long climb to the top after a breakout role in Blackboard Jungle in 1955 that culminated in a Best Actor Oscar for Lilies of the Field in 1964, making him the first Black actor to win a competitive Oscar for a lead performance. He went on to make such classics as In the Heat of the Night (which won a Best Picture Oscar in 1968), Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner, Uptown Saturday Night and Sneakers.

After a struggle with Alzheimer’s disease in his later years, Poitier died in Los Angeles on January 6, 2022, at age 94.

Future pop star Mike Nesmith dropped out of high school to join the Air Force in 1960 and served as an aircraft mechanic.

Less than four years after his discharge, Nesmith was cast as the “smart one” in a made-fortelevision rock group called The Monkees. It turned out that the “Prefab Four” had the chops to be a real band, and they became one of the most beloved groups of the ’60s.

Nesmith went on to a solo recording career and great success as a movie producer and pioneer of music video before returning to the stage as part of a series of Monkees reunion tours.

Nesmith died from heart failure at age 78 at his home in Carmel Valley, California, in December 2021. Since that’s after Military.com’s Veterans Day list from last year, he is being included here.

The first time that Hershel “Woody” Williams tried to enlist in the Marine Corps, the recruiter told him he was too short at 5 feet, 6 inches tall. The rules changed during World War II, and Williams enlisted in the corps in 1943.

He was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Battle of Iwo Jima in February 1945. After his active-duty service, Williams spent 33 years working for the Veterans Administration and then started the Woody Williams Foundation to support Gold Star families.

Williams died at age 98 on June 29, 2022, at the Hershel “Woody” Williams Veteran Affairs Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia. He was the last living Medal of Honor recipient from World War II.

Bernard Shaw

Chicago native Bernard Shaw served in the Marine Corps in Hawaii and North Carolina before leaving the service as a corporal.

He returned home to Chicago and began his career in news broadcasting. He made a steady rise, becoming ABC’s senior Capitol Hill correspondent before taking a flier and joining Ted Turner’s upstart Cable News Network as lead anchor in 1980. Both CNN and Shaw became institutions in the news business. Shaw retired from the network in 2001.

Shaw, 82, died on September 7, 2022, in a Washington, D.C., hospital after contracting pneumonia.

Vin Scully

Vin Scully served in the Navy after graduating high school and later attended Fordham University.

He joined the Brooklyn Dodgers radio broadcast team in 1950 when he was 22 years old and followed the team to the West Coast when it moved to Los Angeles in 1958.

By the time he retired after the 2016 season, he’d been doing games for 67 seasons. He’ll forever be a beloved figure with Dodgers fans.

Scully died in Hidden Hills, California, on August 2, 2022, at age 94.

Bradford Freeman

Bradford Freeman was a student at Mississippi State University when he enlisted in the Army to fight in World War II. He first volunteered to become a paratrooper and later became a mortarman in Company E, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.

As a member of Easy Company, Freeman parachuted into Normandy on D-Day and later fought in Operation Market Garden before getting injured at the Battle of the Bulge. Freeman’s unit inspired Stephen Ambrose’s bestselling book Band of Brothers, which in turn was adapted into the HBO television series.

Freeman, who was the last surviving member of his famous unit, died July 3, 2022, at age 97 in Columbus, Mississippi.

Fred Ward

Fred Ward enlisted in the Air Force upon graduation from high school and served as an airman first class at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio and as a radar technician in Labrador, Canada.

After he completed his service career, Ward worked a series of blue-collar jobs. His acting career didn’t really take off until after he turned 40, but he made a huge impression in movies like The Right Stuff, Southern Comfort, Tremors, Uncommon Valor and Sweet Home Alabama

Ward died on May 8, 2022, in Los Angeles at age 79.

Roger Angell

After completing his studies at Harvard University, Roger Angell joined the Army Air Forces during World War II. He published his first story in The New Yorker in 1944 while editor of an Air Forces magazine.

After the war, Angell’s writing career took off quickly and he

was the fiction editor of The New Yorker by the early 1950s. After editor William Shawn sent Angell to Florida in 1962 to write about the New York Yankees’ spring training, the writer found his true calling. Angell became famous as one of our greatest writers on sports over the next six decades.

Angell died of congestive heart failure at age 101 in New York City on May 20, 2022.

Charley Trippi was playing football for the University of Georgia Bulldogs when duty called and he began service in the Army Air Forces during World War II. He played for the 1944 Third Air Force Gremlins team while on duty.

After he completed his service, Trippi returned to UGA and led the school to an undefeated season in 1946. He was the runner-up for the Heisman Trophy, which went to Glenn Davis of the Army Black Knights.

After college, Trippi joined the Chicago Cardinals of the NFL after signing the most lucrative pro sports contract at that point in history. After he finished an illustrious playing career, Trippi stayed with the Cardinals as an assistant coach until 1965. He was inducted into both the College Football Hall of Fame and the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Trippi died on October 19, 2022, in Athens, Georgia, at the age of 100.

Bob Rafelson grew up in New York City but left home to work at a rodeo in Arizona and play in a jazz band in Acapulco, Mexico, before attending Dartmouth College. After graduation in the early ’50s, he was drafted into the Army and served in Japan, working as a disc jockey for the Far East Network of military radio and television stations.

He got his big career break when he created The Monkees television series, which led to his BBS production company that made and released the landmark hit movie Easy Rider in 1969. Rafelson followed that by writing and directing Five Easy Pieces, the Jack Nicholson-starring picture that was nominated for four Oscars.

Rafelson died from lung cancer at age 89 in Aspen, Colorado, on July 23, 2022.

The program continues to grow. Last year, WAA coordinated wreathlaying ceremonies at more than 3,700 locations across the United States, at sea and abroad. According to their statistics, 2.7 million veterans’ wreaths were placed across the country, and more than 2 million volunteers helped to place wreaths.

In addition to the annual wreathlaying, which occurs every December (this year’s ceremony will take place December 16), WAA makes yearround efforts to remember the fallen, honor those who serve and their families, and teach the next generation

the value of freedom. One of their programs is the Thanks a Million campaign, which distributes cards to veterans all over the country to thank them for their service. The Remembrance Tree program takes families of fallen soldiers out to the balsam tip land (where the wreaths are harvested) to find a tree that will become a living memorial to their loved one. Finally, the WAA Museum is an 1,800squarefoot facility showcasing hundreds of items that have been donated to Wreaths Across America over the decades, including personal photos, awards,

uniforms, helmets and other military memorabilia.

WAA is also dedicated to teaching the younger generation about the value of their freedoms and the importance of honoring those who sacrificed so much to protect those freedoms. They offer learning tools, interactive media projects and opportunities for schools, 4H, scouts and other youth groups to participate in WAA efforts.

Editor’s note: For more information about Wreaths Across America, visit wreathsacrossamerica.org.

Service to one’s country is a noble endeavor indeed. Serving the community is honorable as well. Many cops do both. A decent percentage of cops have previously served in the military or concurrently serve in the National Guard or Reserves while also employed with law enforcement. Many parallels can be drawn between the two professions. There’s a formal rank structure, uniforms, working in a team environment, and so on.

The other, not so pleasant, common denominator between the two professions is that you can get killed doing your job. Whether it be overseas or in your own backyard, the possibility of starting a mission or shift and not making it to the end safely is ever-present.