Greater Ashmont Main Street

Vir Chachra is a Master in City Planning student at MIT with significant experience in transportation in the context of planning, policy, sustainability, and access in both the public and private spheres. Vir merges the world of data analytics with his study of the built environment, supporting qualitative research with interactive visualizations and statistical analyses. His work draws influence from today’s systemic issues, such as the relationships between societal inequities and transit access.

Heidi Shalaby is a SPURS Fellow, participating in a one-year program at MIT designed for mid-career professionals shaping policy, planning, and international development. She is a professor of Urban Conservation at Zagazig University and Director of Central Administration for Technical Affairs at the National Organization of Urban Harmony in Cairo, Egypt.

Lucy Corlett is a Master in City Planning student working at the intersection of environmental equity, public health, and design. Before coming to MIT, she worked on a range of policy issues, including the school-to-prison pipeline, immigrant inclusion, and the renewable energy transition. Her current research focuses on public realm design, urban energy justice, and building decarbonization.

Jessie Tagliani is a Master in City Planning student at MIT who is interested in questions related to civic capacity building and economic development. Prior to coming to MIT, she worked in local government and the nonprofit sector. She holds a BA in the Liberal Arts from St John’s College.

Zak Davidson is a Master in City Planning student at MIT, where he researches the intersection of housing affordability and the energy transition. Previously, he worked as a policy aide to the Columbus Council President, concentrating on land use, transit planning, and post-secondary attainment.

Mabelle Zhang is a Master in City Planning student with an Urban Design Certificate at MIT who is interested in public realm design, waterfront planning, and climate resiliency. She has worked on public space challenges at various scales, from small lots to major parks. She has a background in public development, affordable housing, and housing policy. She holds a BA in Public Policy from Duke University.

Sara Jex is a Master in City Planning student at MIT studying housing, community, and economic development with a background in nonprofit fundraising and advocacy. Her current work focuses on community wealth-building, vacant property reactivation, transit-oriented development, and affordable housing.

We would like to extend our gratitude to everyone whose support, feedback, and collaboration were essential to the completion of this project.

First and foremost, we are deeply grateful to Elle Marrone, Executive Director of Greater Ashmont Main Streets, for her invaluable guidance throughout this process. Her willingness to provide interim feedback, offer insight into our objectives, and coordinate meetings made a world of a difference.

Our sincere thanks also go to Crystal-Grace Sketers, Programs Coordinator at Greater Ashmont Main Streets, for her generous feedback and continued support, which greatly enriched our approach and understanding of the project.

Special thanks to the Greater Ashmont Main Streets Board of Directors, including interim director Stephanie Moura, Michaela Flatley, Steve Datish, Beth Anderson, JP Charboneau, Kacie King, Leslie MacKinnon, Jermaine Malcolm, Christina Metcalfe, Myesha Slaughter, Steve Wilkens, and Mike Wilson for their time, thoughtful insights, and assistance with meeting arrangements.

Our gratitude extends to the local business owners and residents who engaged with our work. Their active participation, valuable feedback, and local knowledge were instrumental in shaping our ideas.

We would also like to thank Jeff Levine and David Gamble, our professors for the Main Streets Practicum, for their instruction and guidance. Together, they encouraged and challenged us to grow as planners and designers throughout the semester. We appreciate you both for connecting us with Greater Ashmont Main Streets through this course.

Finally, we wish to acknowledge our fellow students and other individuals who advised us and exchanged ideas with us throughout this process. Special thank you to Maria Daniela Castillo, Matt Ciborowski, and Johnathan Culley for sharing their expertise.

This report is organized into five sections: (1) Executive Summary, (2) Introduction, (3) Existing Conditions, (4) Corridor Recommendations, and (5) Ashmont Station and Peabody Square Recommendations.

Section 1: Executive Summary provides an overview of the project, along with a chart summarizing our key recommendations organized by subject area and timeline.

Section 2: Introduction outlines the context of the project, setting the stage for the analysis and recommendations that follow.

Section 3: Existing Conditions presents an overview of Greater Ashmont’s history and current characteristics, including development patterns, population demographics, regulations, the business landscape, transportation and mobility systems, and environmental conditions.

Section 4: Corridor Recommendations delves into specific recommendations for enhancing the experience and navigation of Dorchester Avenue (Dot Ave.), activating underutilized parcels, and introducing cultural programming to increase activity across the district.

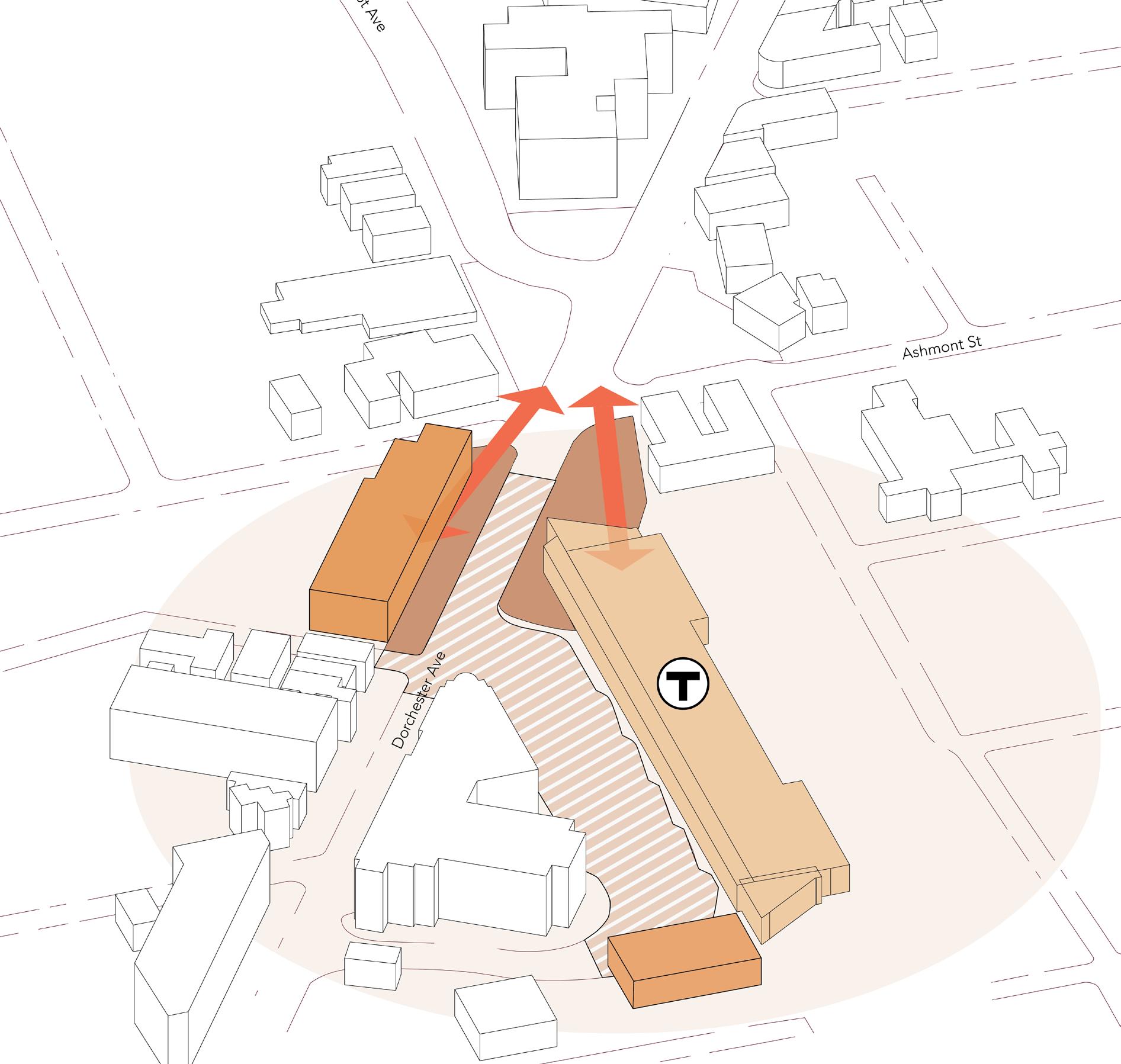

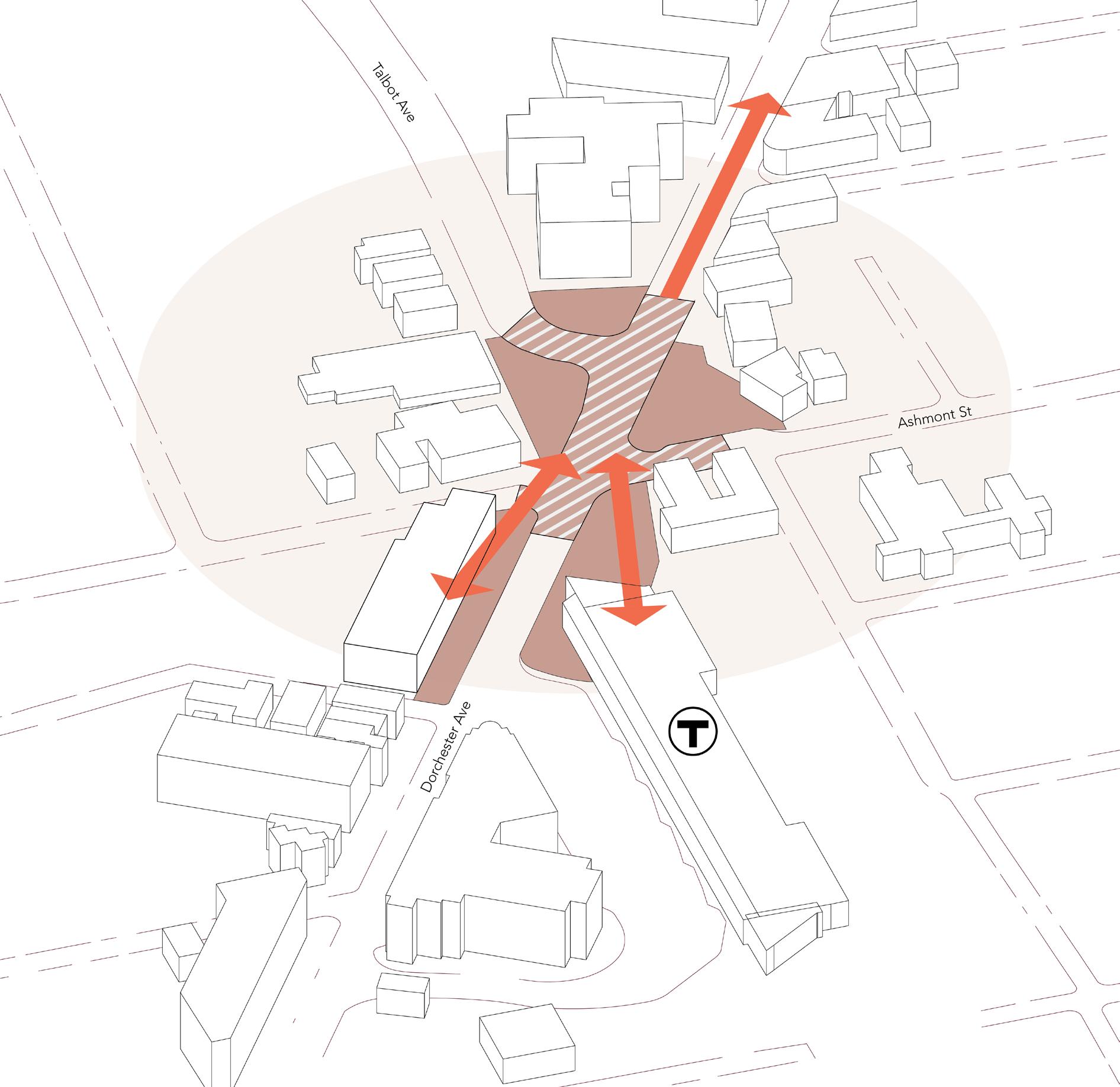

Section 5: Ashmont Station and Peabody Square Recommendations focuses on proposed design interventions aimed at improving the safety, accessibility, and comfort of the central hubs of activity within the Greater Ashmont Main Streets district.

This report is the result of a collaborative partnership between graduate students from the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning and Greater Ashmont Main Streets in Dorchester, Boston. From September to December 2024, a team of six graduate students worked closely with experienced faculty and leaders from Greater Ashmont Main Streets to conduct research, develop analyses, and generate actionable recommendations for the district.

Over the course of 13 weeks, we conducted in-depth research to understand the opportunities and challenges facing the Ashmont area. Based on this research, we developed a series of programmatic, planning, and design recommendations aimed at addressing these challenges and enhancing the district’s vitality. In addition to the recommendations, we identified potential funding sources, proposed timelines for implementation, and outlined key stakeholders whose involvement could be critical to the success of these initiatives.

This report is intended to serve as a foundation for future conversations, planning, and decision-making within the Greater Ashmont community. We hope that it will inspire new ideas, provoke thoughtful discussion, and ultimately guide the next steps in realizing the area’s potential.

Drawing on the Greater Ashmont Main Streets (GAMS) vision, insights from conversations with GAMS staff, board members, residents, and business owners, as well as recurring themes from previous research, our team developed three guiding principles to inform our work:

Connect: Cultivate connection throughout Greater Ashmont by prioritizing safe movement along the Dot Ave. corridor on streets, sidewalks, and plazas

Gather: Create welcoming spaces where people can comfortably stop, rest, and spending time — rather than quickly passing through — to increase patronage of local businesses and enhance Greater Ashmont as a destination

Celebrate: Honor the unique historical and modern urban fabric of Greater Ashmont, and elevate the diversity of cultures and businesses that enrich the district

We offer recommendations related to two main categories: (1) Corridor and (2) Ashmont Station and Peabody Square. For each category, we present three sets of ideas designed to enhance Greater Ashmont’s vibrant commercial district. These ideas are organized by timeline—shortterm, medium-term, and long-term or visionary—to propose a roadmap for Greater Ashmont Main Streets’ future programming and advocacy.

Station + Peabody Square Corridor

Experience and Navigation Activating Parcels History and Culinary Tours Roadways Plazas Intersections

Greening: $

Street Furniture: $

Increased Shade: $$

Visual Screening: $ Pop-Up Events: $ Self-guided tour: $ Quick build bike lane: $$ Bus/bike signals: $$$

Transit lane: $$ One-way Ashmont: $$$ Pop-Up Events: $ Tree Planters: $$ Painted intersections: $$ All-way cross signaling: $$

Tree Planting: $

Mapboards: $

Street Lighting: $$

Storefront Design: $$$

Public Art: $ History and Culinary Festival: $$

Intersection Design: $$$ Small-Business Driven Redevelopment: (cost N/A)

Partner-based guided tour: $$

Protected bike lanes integrated with Dorchester Greenway: $$$

Full plaza conversion: $$$ Raised crosswalks: $$$

Signal timing: $$ Bollards: $$

On-road shared plaza $$$ Shared streets approach: $$$ Intersections as a gathering place: $$$

This report is the result of a partnership between graduate students from the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning and Greater Ashmont Main Streets in Dorchester, Boston. From September to December 2024, a team of six graduate students worked under the guidance of experienced faculty and leaders from Greater Ashmont Main Streets to develop the following analyses and recommendations.

The MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning offers a biannual practicum course designed to connect graduate students with Main Streets organizations. As an interactive workshop, this course enables students to collaborate with a communitybased partner and explore the integration of economic development, physical planning, and design interventions to reactivate urban commercial corridors. Students apply the theories and tools discussed in class to developing recommendations that address the opportunities and challenges within these commercial corridors.

Members of our student team come from a variety of personal and professional backgrounds. We have lived across the United States and world, with team members from Chicago, Los Angeles, Columbus, Philadelphia, Annapolis, and small-town Michigan. Our academic and professional experiences include public policy, public sector development, streetscape redesign, municipal government, and nonprofit legal advocacy. This project marks our collective entry to planning, design, economic development, and community-based work in Dorchester.

Dorchester is one of the most racially and economically diverse neighborhoods in Boston.1 We acknowledge that while one team member has lived in Boston prior to our academic program, and several of us have

1 According to the City of Boston (ACS 2015-2019 estimates), 44% of Dorchester residents are Black, 22.3% are White, 19.9% are Hispanic, 9.9% are Asian, and 4% identify with Other Races. 18% of Dorchester households make under $15,000/year, 13.8% make $50-75,000/year, and 14.2% earn over $150,000/year, demonstrating a wide range of incomes within the neighborhood.

worked in the city, none of our team members currently live or have lived in Dorchester. We recognize the importance of local experience and insight, and we approach this project with respect for the lived experiences and knowledge of Dorchester residents, business owners, and community advocates. We offer the following analysis and recommendations as a starting point to spark further ideas, conversation, and decision-making within Greater Ashmont.

Founded in 1999, Greater Ashmont Main Streets (formerly known as St. Mark’s Area Main Street) is a nonprofit dedicated to strengthening the Dorchester Avenue (“Dot Ave.”) corridor as a vibrant, resilient pillar of the Ashmont community. The commercial district includes more than 130 businesses and serves more than 30,000 residents, workers, and commuters.1 The Greater Ashmont Main Streets (GAMS) service area spans from the MBTA Ashmont Redline Station at the southern end to the DohertyGibson Playground at the northern end.

GAMS is one of twenty Boston Main Streets districts, including five others in Dorchester: Bowdoin Geneva, Fields Corner, Four Corners, Grove Hall, and Uphams Corner.2

The Boston Main Streets Office coordinates with Main Streets America to provide financial and technical assistance to local Main Streets organizations, which hire an Executive Director to fundraise, develop, and implement an annual work plan.

As of December 2024, GAMS has one full-time Executive Director, one part-time Programs Coordinator, and a board of local residents, business owners, and community leaders.

GAMS “strives to further develop the district as a vibrant and resilient community in which all may find joy and a sense of belonging” by offering:

Ave. Report, the 2014 St. Mark’s Area Main Street Community Visioning Report, the ongoing 2024 Greater Ashmont Residents and Visitors Survey, and other research efforts.

1Greater Ashmont Main Streets. (2024). “History.”

2 Greater Ashmont Main Streets. (2024). “Boston Main Streets.”

• A transit-oriented, Complete Streets locale that benefits a culturally diverse population,

• A complementary business mix that supports the needs of area residents and civic organizations,

• The appeal of rich historical qualities melded with modern day development, and

• A vibrant social scene offering spaces favorable for community gatherings, which will attract patronage from beyond our region.3

These mission elements are rooted in previous research conducted by GAMS, as demonstrated in the 2004 Connecting Dot

3 Greater Ashmont Main Streets. (2024). “Our Vision.”

Drawing from the vision elements outlined above, insights from conversations with GAMS staff, board, residents, and business owners, and recurring themes identified in past research efforts, our team developed three guiding principles for our work:

Connect: Cultivate connection throughout Greater Ashmont by prioritizing safe movement along the Dot Ave. corridor on streets, sidewalks, and plazas

Gather: Create welcoming spaces where people can comfortably stop, rest, and spending time—rather than quickly passing through—to increase patronage of local businesses and enhance Greater Ashmont as a destination

Celebrate: Honor the unique historical and modern urban fabric of Greater Ashmont, and elevate the diversity of cultures and businesses that enrich the district

Over the course of 13 weeks, our student team collaborated with Greater Ashmont Main Street (GAMS) to develop the analyses and recommendations detailed in this report.

In mid-September, we visited Ashmont for a tour of the commercial corridor with Elle, during which we conducted initial analyses to identify perceived challenges and opportunities in the district. We then formed student groups and began delegating tasks.

In October, we shared our initial findings with the GAMS board during a meeting on October 22, hosted at a local office and commercial space. This meeting provided

an opportunity to gather feedback, align our goals, and refine our ideas.

Throughout November, we deepened our work on each project stream, developing initial strategies. We held an internal design charrette and several meetings to discuss planning, design, and programmatic ideas.

To conclude the project, on December 5, we presented our key recommended strategies to business leaders at a GAMS business mixer, hosted at Revamp Training on Dorchester Avenue. The event featured catering from Tavolo, an Italian restaurant and Ashmont staple.

We delivered a 30-minute presentation summarizing our high-level recommendations, followed by a 10-minute group discussion. Afterward, attendees were invited to visit our team members, who were stationed around the room with posters categorizing our main recommendations. We provided each attendee with 10 paper “coins” featuring the GAMS logo, which they could distribute among the categories based on which ideas resonated most with them and which they believed GAMS should prioritize in the coming year.

In mid-December, we delivered this final report to the GAMS staff for future use in their ongoing work.

Discussion at October 22 GAMS Board Meeting with MIT Student Team Guests

Indigenous peoples of the Massachusett tribe stewarded land in the Dorchester region for thousands of years.1 The Massachusett Neponsets lived alongside the Neponset River estuary, just southeast of Greater Ashmont, which provided plentiful opportunities for fishing, shellfish gathering, hunting, and farming.

European settlers arrived in the 1620s, inflicting colonialist violence and introducing devastating infectious diseases, rapidly killing significant portions of the Neponset population.2 The Charter of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, issued by King Charles of England in 1629, directed settler colonialists to “reduce or convert to submission the indigenous people of New England,” directly targeting the Massachusett people.3 In 1633,

1 Vaughan, A.T. 1999. New England Encounters. The New England Quarterly.

2 The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag. 2019. “The History of the Neponset Band of the Indigenous Massachusett Tribe.”

3 “The Charter of Massachusetts Bay” 1629. American Colonist’s Library Primary Source Documents, The Avalon Project, Yale Law School.

English colonists displaced Massachusett Neponsets to Ponkapoag, a “praying town” in the western Blue Hills area created by settlers to forcibly convert and assimilate indigenous people into Puritanic culture and practices.4 Despite promising indigenous peoples in Ponkapoag arms-backed protection, the European colonists inflicted land loss, forced internments, and cultural erasure on the Ponkapoag under their expanding control5 .

Greater Ashmont remained rural farmland until the 1870s, when the establishment of the Old Colony railroad station spurred new development.6 During this period into the early 19th century, single-family homes were built alongside the development of the Peabody Square commercial district, which grew to include a railroad station, market, hall,

4 The Massachusett Tribe at Ponkapoag. 2019. “The Removal of the Neponsetts to Ponkapoag.”

5 Ibid.

6 Historic Boston Incorporated. 2009. “Commercial Casebook: St Marks Area.”

stables, a grand church, and a fire station.7 Rapid residential expansion through the late 19th and early 20th centuries introduced densely clustered triple-deckers, a hallmark of Dorchester, while the electrification of railroad tracks in 1928 helped Dorchester Avenue fully develop as a commercial hub.8 The introduction of an electrified train line solidified Greater Ashmont’s identity as a “streetcar suburb” of Boston.

Between 1900 and 1950, there was a significant increase in construction along the Dot Ave. corridor, with developers primarily focusing on residential, commercial, and mixed-use buildings. It wasn’t until after the 1960s that properties designated exclusively for commercial or industrial purposes began to appear. Mixed-use spaces and

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

condominiums have continued to grow over time, reflecting evolving development patterns. Since the 1960s, tax-exempt properties (e.g., non-profits) have also seen consistent growth, while lower-density residential development has plateaued, likely due to space constraints and zoning requirements detailed in the following section.

Notable buildings constructed since the 1950s include an office for the Massachusetts Affordable Housing Alliance, a Boston Housing Authority apartment building, a school, and two churches. These developments illustrate the shift towards institutional and community-oriented uses within the area. In 2008, The Carruth, a large, mixeduse, transit-oriented development added new commercial spaces that are now home to a bank, coffee shop, restaurant, other shops, and offices, including GAMS’s current office space.

A number of significant historic buildings and monuments in the Greater Ashmont Neighborhood are located near Peabody Square, with several properties scattered across the rest of the neighborhood.

Buildings on the National Register of Historic Buildings

All Saints Parish Church

211 Ashmont Street

The episcopal church was designed and built in 1892 by Ralph Adams Cram, a renowned American church architect. All Saints eventually became known as the archetype of the American Gothic church architectural style during the 20th century, and was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980.1

The Peabody Apartments

197 Ashmont Street

This apartment consists of four connected brick triple-deckers with servants’ quarters

1 Dorchester Atheneum. 2017. “All Saints Church, 211 Ashmont Street.”

under the roof. Built in 1892, it was intended to serve as an architectural complement to the All Saints Parish church next to it.2

The Industrial School for Girls (built 1858) is an example of the industrial school movement that took place in Boston and the wider region of New England. The property is associated with the progressive reform movements of the early 20th centuries, which sought to address the inequities of industrialization and overturn conceptions of middle-class domesticity and traditional women’s roles in American societies.3

O’Brian’s Market

1911-1913 Dorchester Avenue/175 Ashmont Street

Built in 1884, this red brick and clapboard Queen Anne building was designed by the noted Boston architect W. Whitney Lewis.

2 Dorchester Atheneum. 2017. “Carruth Street Peabody Square.”

3 City of Boston. 2023. “Industrial School for Girls Study Report.”

Originally a grocery and produce store, it is notable for also having been designed to provide a variety of uses, including underground storage for dry goods as well as residential rooms above the store.4

Originally built in 1824, this building was later converted to a three-family house in the early 20th century. The building is best known for the fact that James B. Conant, later President of Harvard University, was born there.5

The building dates back to 1880, when it was built by a successful leather merchant. It was designed by the architect George Meacham, who also designed the Boston Public Garden. Over 100 years later, the house later belonged to the members of the famous band New Kids on the Block.6

4 Dorchester Atheneum. 2017. “Obrien’s Market.”

5 Dorchester Atheneum. 2017. “Bailey Street: The Former Bailey Estate House.”

6 Daniel, S. 2021. “‘New Kids’ house a landmark? Neighbors petition city panel for historic status.” Dorchester Reporter.

All Saints Church

Source: Dorchester Atheneum

Field-Knight House

Source: Seth Daniel for the Dorchester Reporter

The Peabody Apartments

Source: Apartments.com

O’Brian’s Market

Source: Dorchester Atheneum

The Industrial School for Girls

Source: Dorchester Atheneum

Bailey-Conant House

Source: Realtor.com

Greater Ashmont is a racially and economically diverse neighborhood that supports a large population of families and young people, as well as those at all different stages of life.

Approximately 30% of Greater Ashmont residents are white, 28% are Black, 19% are Hispanic, and 18% are Asian. Compared to Dorchester, Greater Ashmont has proportionally less Black and Hispanic residents, but more White and Asian residents. The area is notably more racially diverse than Boston overall, with no single racial group comprising more than 30% of the population. Over the past decade, the neighborhood has experienced demographic shifts, with increases in both White and Hispanic populations and a slight decrease in Black and Asian populations.

Additionally, the area is home to a strong Spanish- and Vietnamese-speaking community, as reflected in language data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau. 12% of residents speak Spanish at home, while 11% speak Vietnamese. 64% of households in the Greater Ashmont area only speak English at home.

Greater Ashmont is home to residents across the income spectrum. Compared to Boston, both Dorchester and Ashmont have a higher percentage of very low-income households (earning less than $25,000) and a lower percentage of very high-income households (earning $200,000 and above).

The income per capita in Ashmont is $38,000, closely aligned with Dorchester at $36,000, but significantly lower than Boston’s average of $55,000. However, when examining median income by census block, Ashmont’s median of $91,500 is much closer to Boston’s $98,000, indicating pockets of higher-earning households. This median is also notably higher than Dorchester’s $70,000, highlighting income disparities within the area.

Over the past decade, Greater Ashmont has experienced significant economic changes, particularly in the middle-income brackets. The number of households earning between $25,000 and $49,999 has declined by nearly 50%, and households earning between $50,000 and $99,999 decreased by 12%. In contrast, the number of households earning between $150,000 and $199,999 more than

doubled, while those earning $200,000 and above more than tripled during this period. These shifts suggest a growing income disparity in the area, with a notable increase in high-income households and a reduction in middle-income ones.

Source: ACS 5-year estimate (2018-2022)

Greater Ashmont is a neighborhood with residents of varying ages and household sizes. The largest age group in the area is those aged 18 and younger, comprising just over 20% of the population, followed by individuals aged 35 to 44, who make up just under 17%.

In terms of household size, the most common configuration is two people, accounting for just over 30% of households, followed closely by single-person households at 28%. Three-person households represent about 17%, while four-person households make up roughly 14%. The proportion of households continues to decrease for larger household sizes, including those with five, six, or seven or more members.

55% of households in the GAMS service area are renters, while 45% are homeowners. This suggests that the residential areas surrounding the commercial corridor have a slightly higher homeownership rate compared to the City of Boston as a whole, where 65% of households are renters. However, this overall figure (55%) masks significant distributional differences across the Greater Ashmont neighborhood. The most northeastern part of the neighborhood has a rental rate of 80%, while a few blocks to the southwest have only a 24% rental rate. The average rent around GAMS is approximately $1,700, about 14% lower than Boston’s average of $1,981. Additionally, nearly two-thirds of the block groups around the GAMS service area have a median rent burden above 30%, indicating that a substantial portion of residents are spending a large percentage of their income on housing.

ACS 5-year estimates (2018-2022)

Greater Ashmont’s zoning and land use policies have shaped the vibrant Dorchester Avenue (“Dot Ave.”) commercial corridor.

The dense mix of retail options and amenities supports walkability and local shopping, but strict construction and use requirements pose challenges in Boston’s current development climate. Additionally, limitations on permitted businesses may exclude viable, non-disruptive tenants.

Zoning codes define where specific building types and uses can exist within the city. Along Dot Ave. in the Greater Ashmont Main Street (GAMS) area, most parcels are zoned MultiFamily Residential & Local Services (MFR/ LS). This zoning encourages medium-density housing (like single-family homes and tripledeckers) alongside ground-floor retail.

Multi-Family/Local Services

The MFR/LS subdistrict allows ground-floor businesses such as restaurants, bakeries, libraries, churches, laundromats, and daycares, while it restricts entertainment, recreation, cultural, healthcare, industrial, and vehicular uses. Many commercial options, including bars, gyms, theaters, and museums, are also restricted.

Some uses (schools, art galleries, libraries, post offices, and banks without drive-thrus) require conditional permits from the Boston Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA). The reasoning for these allowances and restrictions is not always clear. While the subdistrict allows dry cleaners, laundromats, tailors, and shoe repair shops, it requires conditional permits for barber shops and upholsterers and prohibits tattoo shops. These commercial restrictions also apply in surrounding residential zones.

Developers and business owners face bureaucratic challenges to introduce new commercial uses along Dot Ave. Applying for zoning variances takes time and money, leading to increased expenses for local business owners. Nonetheless, successful zoning allowances and past variances have contributed to the corridor's diverse mix of

uses today.

While Dot Ave. is primarily zoned MFR/LS, varying residential districts sit adjacent to the district. These districts do not permit

commercial activity and are typically limited to three residential units per parcel. These use restrictions concentrate commerce and neighborhood retail activity on Dot Ave.

Minimum Lot Size 4,000 sq. ft. for the first 4-units Approved for smaller lot sizes

Minimum Lot Area per Dwelling Unit 1,000 sq. ft. per unit

Minimum Lot Width 30 to 40 ft

Minimum Frontage 40 to 50 ft

Maximum Floor to Area Ratio (F.A.R.) 1.0 FAR

Maximum Building Height 3-stories, 35 ft

Minimum Usable Open Space 400 sq. ft. per Dwelling Unit (DU)

Minimum Front Yard 5 ft

Minimum Side Yard 10ft

Minimum Rear Yard 20 ft (30 ft for more than 3 units)

Minimum Number of Parking Spaces 1.5 spaces per DU

Minimum Number of Loadings Spaces 1.0

Source: City of Boston Planning Department Zoning Code

None found

None found

Approved for 23 ft at 8 Banton Street

Approved 2.7 FAR at 500 Talbot

Approved for 5-stories at 60 ft at 500 Talbot

Approved for 78 sq. ft per DU at 1970

Dorchester Ave

Approved for 2 ft at 1700-1710 Dorchester Ave

Approved at 8 Banton Street

Approved for 5 ft 5 in at 500 Talbot

Approved for 0.3 spaces/DU at 1700-1710

Dorchester Ave

Approved for 0 at 1970

Dorchester Ave

Overlay Districts are special zoning districts placed on top of an existing zoning district. The vast majority of parcels within the GAMS service area are not subject to overlay districts. However, a handful of historic properties around Peabody Square, including 195 Ashmont Street and 175 Ashmont, are covered by a Neighborhood Design Overlay district. Proposed projects within a Neighborhood Design Overlay are subject to review by the Boston Landmarks Commission. Both of these properties are historic and sit on the intersection of Ashmont and Dorchester, immediately north of Ashmont Station.

Boston’s neighborhood design overlay districts are important tools in supporting local historical preservation efforts. Article 65, section 32 of the city’s zoning code originally created these districts as a means to “protect the historic character, existing scale, and quality of the pedestrian environment” in the Dorchester neighborhood. In practice, this means that while the development of new housing is permitted in these areas, any new construction or rehabilitation must seek to preserve and complement the quality of the existing urban fabric.

A design review is triggered under the following circumstances (as per Article 80E-2.1(b)(iii):

• A change in the roof shape, cornice line, street wall height, or building height of an existing building.

• Building a structure taller than 300 feet.

• A change in the building massing or size/ location of door or window openings, where such alteration affects three hundred or more square feet of an exterior wall area, or a smaller exterior wall area if expressly provided in the underlying zoning

The special districts will help ensure that modifications to Greater Ashmont’s historic built environment will not happen too quickly or too drastically, and thus maintain the integrity of the neighborhood’s character. However, this type of zoning creates several challenges for building owners, adding time and costs to complete and satisfy the design review. Given that many of the businesses along the commercial corridor are locally owned, this imposes an additional cost burden on the resident shopkeepers and restaurant owners who need to regularly keep their establishments up to code.

Greater Ashmont’s commercial corridor, primarily located along Dot Ave., features a diverse array of businesses. According to the GAMS Business Inventory for Fiscal Year 2025, salons and barber shops account for over 20% of businesses within the GAMS service area, representing the highest concentration of any single business type. Professional services, including legal and accounting firms, rank second, followed by medical and dental services as the third most common category. The area’s commercial diversity is further highlighted by the presence of restaurants, boutiques, retail shops, real estate and insurance firms, automotive services, grocery stores, laundromats, coffee shops, banks, bike stores, liquor stores, and nonprofit organizations.

People of color and women-owned businesses are strongly represented within the GAMS service area. 24% of all businesses are Blackowned, 4.1% are Latinx-owned, and 32.2% are women-owned. Notably, Black and Latina women comprise nearly 65% of all Black and Latinx-owned business owners.1 Approximately 50% of all women-owned businesses in Greater Ashmont are owned by Black women.2

1 GAMS Business Inventory (FY2025)

2 Ibid.

Black and Latina women comprise nearly 65% of all Black and Latinx business owners in Greater Ashmont

The GAMS service area is rich in transportation assets and demand. As a key rail and bus hub, the MBTA Ashmont Station attracts tens of thousands of transit riders per day, powering the local economy. However, the reliability of this infrastructure plays a key role in access to work, shops, and the broader community. The network and community travel preferences demonstrate the station and transit infrastructure as important customer generators. Building business around existing transportation infrastructure and advocating for its betterment will boost local economic activity.

Dot Ave. runs through the GAMS service area and defines north/south traffic in the region while serving as the premier artery for the area. The area is characterized by a series of MBTA Red Line stations, with Ashmont being the largest at the end of the line. Ashmont also serves as the northern terminus for the Mattapan trolley and a series of high volume bus routes (the 18, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 215, and 240). Ashmont station’s busway is a major trip generator in the region and a large source of transfer traffic between bus/walking/bike and the Red Line. East/west traffic is largely facilitated by Talbot Ave., Ashmont St., and

Gallivan Blvd to the South, connecting the neighborhood to greater Dorchester and Boston. These roads also carry a significant amount of bus traffic, especially Talbot Ave., which connects directly to the square north of Ashmont Station.

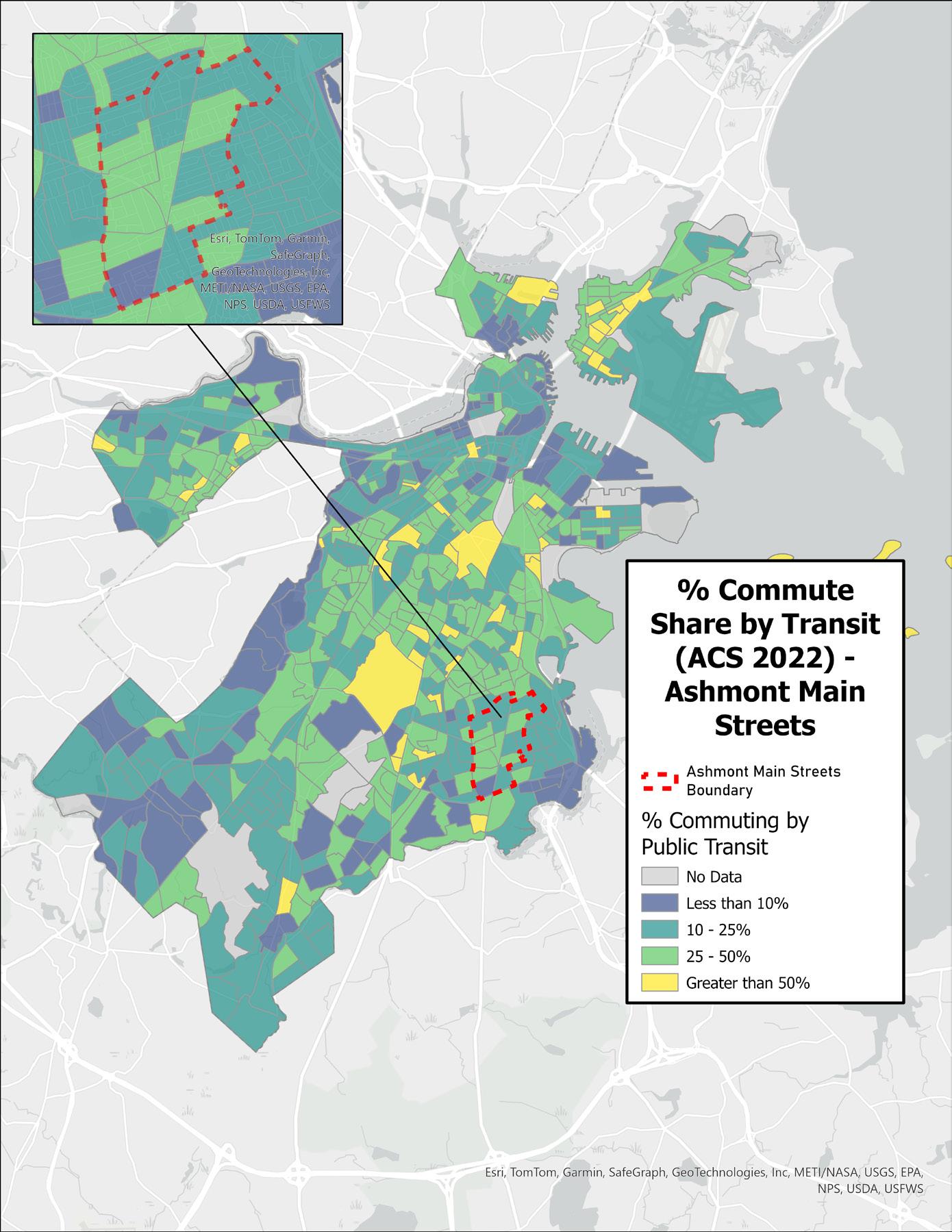

Despite high transit dependency in Greater Ashmont, commute times are higher than the rest of Boston, on average. This demonstrates higher transit dependence (~40% of all commute travel) but also a sensitivity to unreliable service or options.

Although Greater Ashmont is well-served by public transit, current zoning mandates substantial parking minimums that may not reflect the needs of this transit-oriented community. Requirements include 1.5 parking spaces per dwelling unit and 2 spaces per 1,000 square feet of retail, though some recent developments, like 17001710 Dorchester Ave, have been approved with much lower ratios to align with transitaccessible development goals. According to 2022 Census estimates, nearly 40% of Greater Ashmont residents do not own a car, underscoring residents’ reliance on public transit.

The bus is a primary transit mode in Dorchester, especially for local destinations not accessible by rail. The Ashmont MBTA station, serving as a key layover and transfer point, sees significant traffic from riders. Additionally, the buses serving the GAMS service area are among the highest used in the entire MBTA network, carrying tens of thousands of passengers daily (per bus).

Bus traffic is a consistent weekday and weekend phenomenon in Greater Ashmont. In fact, some buses have experienced higher total daily weekend ridership compared to weekdays due to their ability to connect riders to local destinations and businesses. For example, the 23 bus carried more riders on weekends than on weekdays in Fall 2023. Post-COVID shifts in work-from-home arrangements and localized economies have altered mobility patterns, moving demand away from peak commute hours and weekdays. While the long-term impact of COVID remains uncertain, current trends suggest that mobility demand is now more evenly distributed throughout the week. Businesses within the GAMS service area have an opportunity to cater to this bus traffic by offering more weekend programming and

advocating for improved infrastructure, as buses remain a key mode of transportation in this neighborhood.

Since Greater Ashmont is built around rail infrastructure, rail ridership also plays a crucial role in the neighborhood’s accessibility and economic vitality. The Ashmont MBTA station has traditionally served as a commuter hub for those traveling downtown, but this dynamic has shifted post-COVID. Observing the data, midday ridership on the Red Line is peaking across stations in the GAMS service area. Factors such as the rise of work-fromhome opportunities and the localization of the economy are contributing to this shift. The data shows that people are using transit throughout the day, despite the system’s original design to primarily accommodate commute trips. This shift presents an opportunity for businesses to attract customers beyond the typical work commute and capitalize on midday riders. Additionally, it is notable that nighttime demand at these stations is relatively low. This presents an opportunity to cultivate a nighttime economy, moving away from the traditional commuteoriented demand and transforming Ashmont into a vibrant, all-day economy.

Safe transport networks play a vital role in comfortably accessing street businesses and traveling in/out of the neighborhood. The Ashmont Main Streets area is no exception, and has witnessed a number of pedestrian and motor crashes since 2015. Dorchester Ave. has witnessed many such crashes because it is a narrow roadway that serves the needs of motorists, pedestrians, and cyclists alike with relatively little priority infrastructure. Making diverse roadway use safer should be a key priority not only for business accessibility but also because safer environments feel more welcoming for residents and businesses alike.

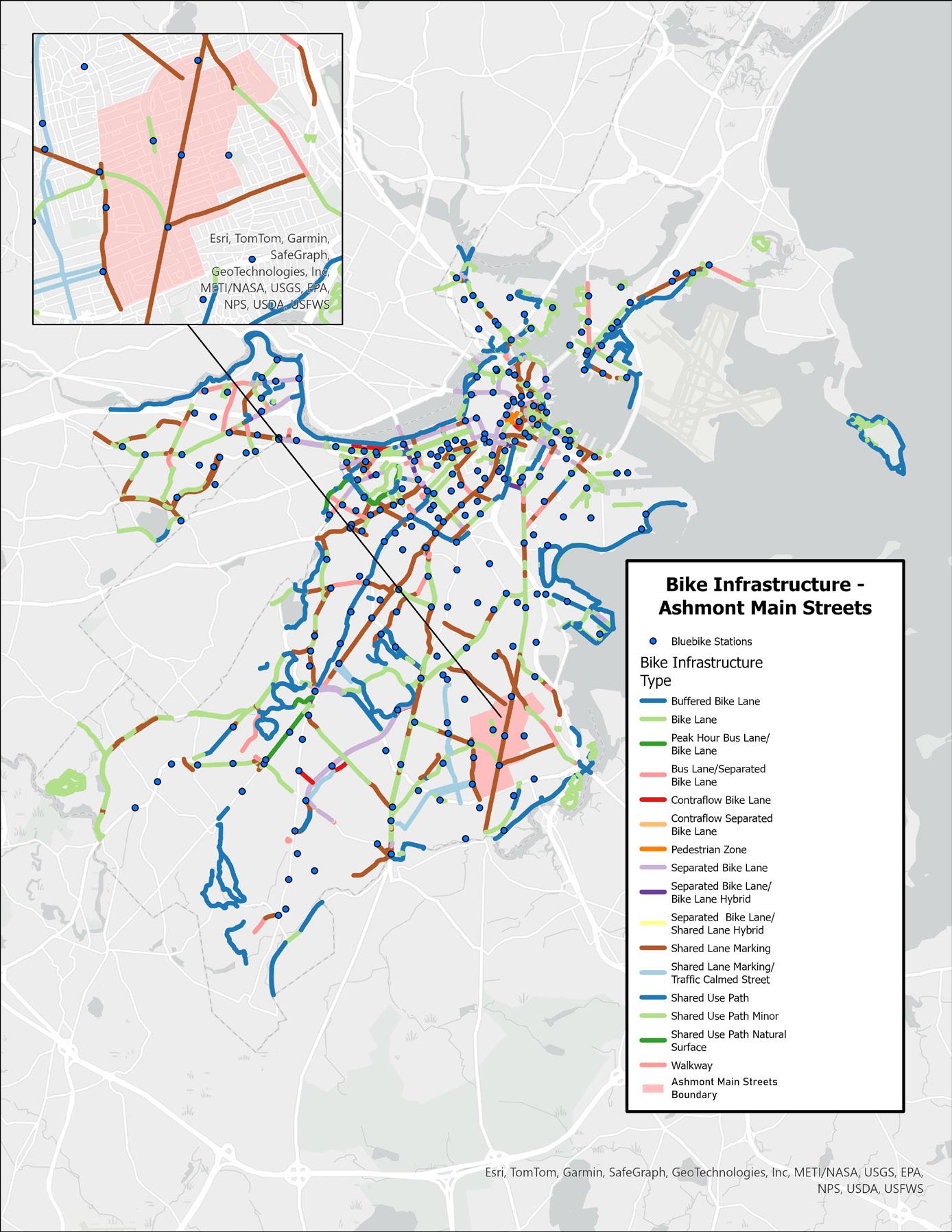

As part of the City of Boston’s Bike Network Plan, multiple neighborhoods are seeing improvements to bike infrastructure and facilities from Blue Bike Stations to protected lanes. This infrastructure would increase both safety and accessibility in Ashmont, allowing riders to choose a sustainable mobility option. Currently, the main streets area only has shared lane markings or painted bike lanes serving the neighborhood. This infrastructure, while a good start, does not provide the safety benefits needed to all age groups and ability types to bike to/from Ashmont.

From the perspective of connectivity, there is demand for biking in the neighborhood. An analysis of trips from the community’s five BlueBike stations reveals that community members make local bike trips often. Most of these trips are to Red Line stations or up Dorchester Avenue to local destinations and businesses. Advocacy for bike infrastructure (and more stations) should focus on increasing this sort of connectivity. Bikes also serve as a critical alternative during transit outages or unreliability.

Public health concerns such as urban heat-island-effect and a lack of green and open spaces exacerbate existing social vulnerability and racialized resource disparities in Greater Ashmont.1,2 As the city bolsters efforts to address such disparities, there is more opportunity than ever to implement simple and effective solutions.3

MAPC’s Climate Vulnerability Index assesses both climate sensitivity and adaptive capacity at the neighborhood-level, utilizing metrics such as age, health, occupation, and housing features to determine sensitivity.4 The index then uses social connection and access to information, networks and mobility, financial resources, as well as race, ethnicity and language to determine local adaptive capacity (the community’s ability to get out of harm’s way, adjust to changes, or regroup after climate events). Greater Ashmont is home to significant climate sensitive populations.

1 City of Boston. 2016. Climate Vulnerability Assessment.

2 Basu, G. & Jay, J. 2023. “Boston’s summer heat is an issue of racial equity. ‘Greening’ our city is one solution.” WBUR.

3 City of Boston. 2019-2024. Tree Canopy Assessment, Healthy Homes Assessment, & Heat Resilience Solutions.

4 Metropolitan Area Planning Council. n.d. Climate Vulnerability in Greater Boston.

Dorchester’s high indoor and outdoor temperatures during summer months are well documented.1 Compared to other parts of Boston, there are fewer green spaces and more clusters of commercial buildings. A network of impermeable and unshaded surfaces runs through the neighborhood, making up 58% of Dorchester’s land area. Transportation infrastructure such as I-93, arterial roads, and rail lines also absorb and concentrate heat in specific areas.2

In 2019, the hottest temperature in Boston (102.6 degrees) was recorded near the Ashmont MBTA station.3

The Land Surface Heat Map on the following page shows consistently high temperatures in the area around Peabody Square. The intersection contains many unshaded impervious surfaces, such as the sizable driveway outside of Flames and the parking lot that surrounds All Saints Church.

Despite healthier levels of tree canopy coverage in the block groups that comprise Greater Ashmont, the Dot Ave. commercial corridor lacks the shade tree coverage needed to provide relief from heat at the street level.

Walking north up Dorchester Avenue, there isn’t a single tree or shade structure on the eastern side of the street until about a half mile from Peabody Square.

While there is limited sidewalk space within this corridor, the sidewalks tend to be the same size (ranging from 6-13ft wide) on both sides of the street. The western sidewalk is able to accommodate consistent placement of shade trees. These unshaded stretches may add to the heat peak zone.

In addition, the Heat Resilience plan explains that a major source of heat absorption are the wide, paved surfaces exposed in multiway intersections like Peabody Square. These larger intersections are also often lined with dark-roofed buildings, further exacerbating localized heat absorption. While many of the buildings along Dorchester Avenue have black or gray roofs, the Peabody/Englewood Apartments (a Boston Housing Authority property) and The Carruth have white roofs, which are much more effective at reflecting sunlight and lowering internal building temperatures.

1 Espinoza-Madrigal, I. et al. 2021. “Breaking up Boston’s heat islands.” Commonwealth Beacon.

2 City of Boston. 2024. Heat Resilience Solutions.

3 Wassar, M. 2019. “Mapping Boston Hot Spots, Block By Block.” WBUR.

The Boston Heat Resilience plan describes how land use impacts day and nighttime temperatures in Boston neighborhoods. Concentrated mixed-use commercial districts with dark-roofed buildings like Greater Ashmont absorb more heat during the day than residential areas.The plan also points out that “zero-setback commercial areas” often lack shade trees, further contributing to higher daily temperatures.

Peabody Square is situated between two areas of slightly higher elevation—Ashmont Hill to the west and Adams Village to the east—and is generally surrounded by higher elevations that slope down toward the Neponset River and Dorchester Bay. Based on observable grade changes along Dorchester Avenue, it can be inferred that stormwater runoff is likely accumulating within the GAMS jurisdiction and flowing south along Dot Ave.

It is crucial for GAMS to leverage city and regional resources to improve climate resilience along Dorchester Avenue. By focusing on the multi-way intersection and parklets around Peabody Square and the Ashmont MBTA station, green infrastructure and design strategies can play a key role in addressing environmental challenges such as urban heat and stormwater runoff. These approaches can also enhance the public realm, creating cleaner and more inviting spaces for commuters, business owners, residents, and shoppers. The following sections of this report outline recommendations for integrating these strategies within the GAMS service area.

MBTA Bus Network Redesign and Bus Priority Plan

The MBTA Bus Network Redesign and the City of Boston’s Bus Priority Plan aim to increase frequency on these routes and establish a priority network to expedite bus service. This is expected to boost ridership, providing businesses with additional opportunities to plan around new infrastructure and transitoriented streets while preparing for improved access in and out of their community.

The City of Boston’s Squares + Streets initiative aims to implement zoning reforms that enhance housing, public spaces, small businesses, and arts and culture along transitaccessible main streets.1 The proposed reforms include reformatting zoning code text and tables for improved clarity and accessibility, increasing flexibility in allowable land uses, and requiring special permission for residential units on the ground floor of buildings along main streets.2 These changes seek to foster a vibrant mix of building uses, heights, and housing types to further activate commercial corridors. While the City has identified Codman Square + Four Corners Main Streets and Fields Corner Main Street as neighborhoods potentially eligible for Squares + Streets zoning, Greater Ashmont is not included on the list as of December 2024.3

1 City of Boston Planning Department. 2024. “Squares and Streets.”

2 City of Boston Planning Department. 2024. “Squares and Streets Zoning Districts.”

3 Ibid.

The Dorchester Greenway is a proposed off-road pedestrian and bicycle path that would run atop the MBTA Red Line tunnel between Ashmont Station and Park Street.4 Greater Ashmont Main Streets (GAMS), in collaboration with the transportation advocacy group LivableStreets Alliance, has been a driving force behind this initiative.5 In 2017, GAMS partnered with local designers and community members to develop concepts for the greenway, advancing the vision for this transformative project.6 Currently, the City of Boston and the MBTA are conducting a feasibility study for the greenway, funded by a MassTrails grant, with completion expected in June 2025.7 The potential for this greenway informs many of the recommendations discussed throughout this report.

4 City of Boston. 2024. “Dorchester Greenway.”

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

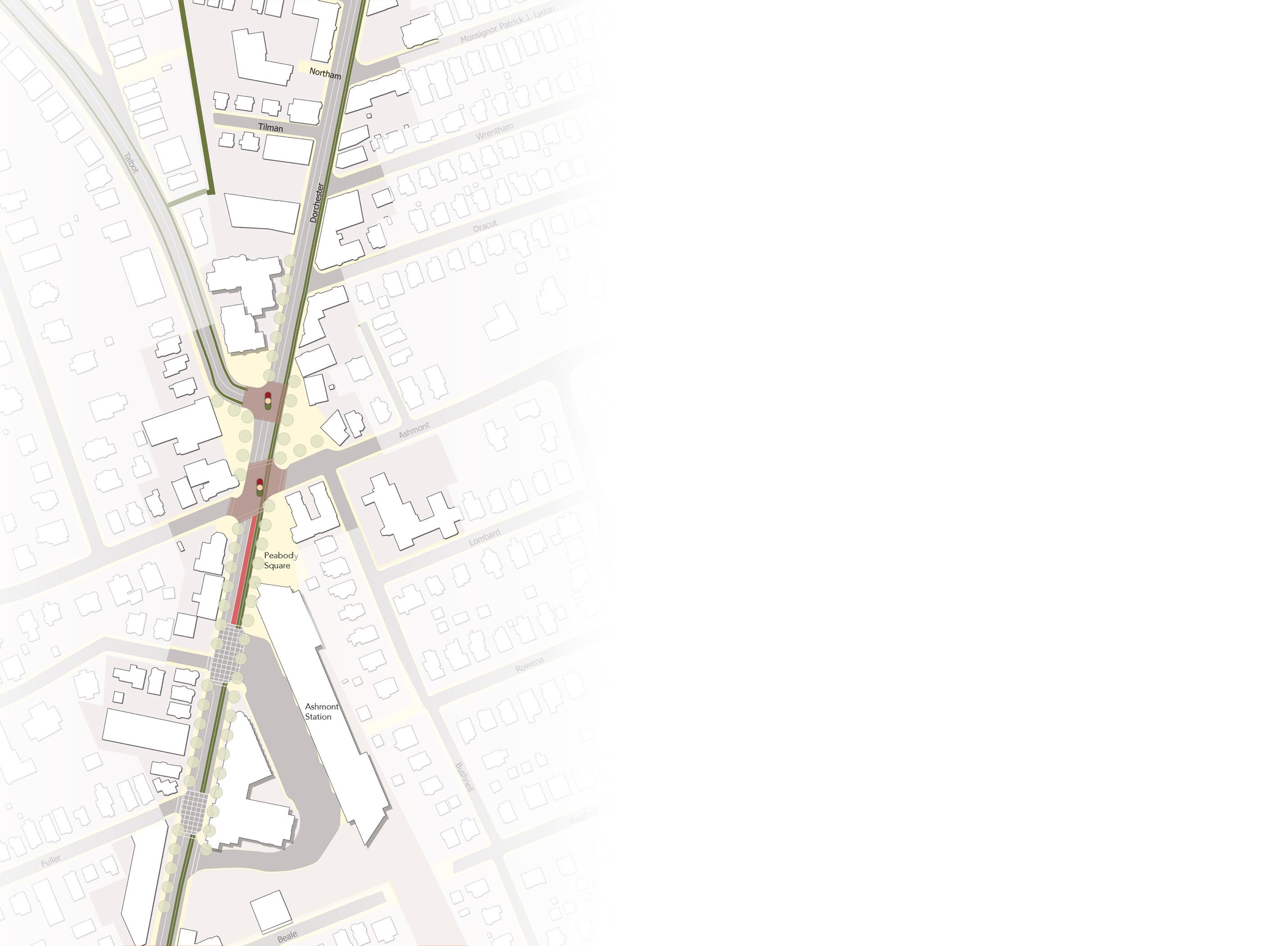

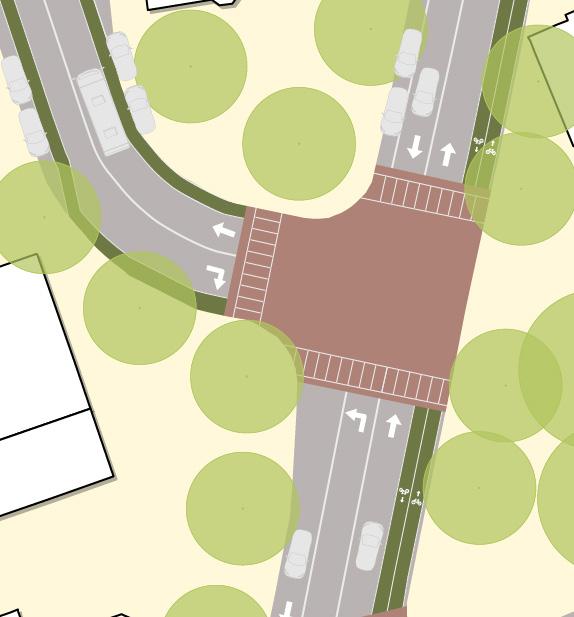

To most effectively make recommendations within the scope of the Greater Ashmont Main Street organization’s goals, we focused on strategies to improve the pedestrian experience and navigation along Dorchester Avenue between Peabody Square and St. Mark’s Church. We also propose strategies for how to repurpose and activate underutilized parcels such as surface parking lots to create a more cohesive commercial corridor. Half of a mile of Dorchester Avenue cpmprises this district, so we also suggest outdoor activities that can promote pedestrian movement and increase the connectivity throughout the corridor.

As described in the “Environmental Conditions” section, much of the GAMS Dot Ave. corridor, especially the southern sidewalk, is not adequately shaded by street trees. The resulting summer temperature spikes can harm to the physical health and wellbeing of pedestrians, particularly those accessing businesses and transportation within the corridor. The implementation of green infrastructure such as shade and heat-mitigating plants and structures, is an attainable short-term goal for GAMS and the larger Ashmont community.

A possible first step for greening the Ashmont commercial corridor is placing planters at key intersections and high traffic areas along the sidewalk. Planters are lowmaintenance in comparison to other types of green sidewalk infrastructure such as landscaping and trees, and can play a small role in improving perception and safety on sidewalks. In Philadelphia, planters are used not only to beautify and bring a sense a sense of place, but also to protect pedestrians at a five-way intersection. By strategically placing large planters in the road and painting in the extended sidewalk, the part of the street used by cars is made much narrower, slowing traffic and shortening the distance pedestrians have to cross. Planters can also sit on the sidewalk to create a buffer between pedestrians and the street, or to signal business entrances and create welcoming public spaces.

While trees are a low-cost and proven urban heat-mitigation strategy, it can be difficult for dense thoroughfares like Dot Ave. to meet City requirements for new street-level plantings.

Given that there are not any existing tree pits or planting areas for street trees on the south side of Dot Ave., property owners would need to request new tree pits on the sidewalk. To make this request, the sidewalk conditions need to meet the following criteria:

• The tree must be 10 feet from any light poles, driveways, or hydrants.

• The tree needs to also be 10 - 20 feet from any intersections, depending on the direction of traffic.

• You can only plant trees on sidewalks that are six-feet wide (72 inches), not including the curb.

• There must be a five-foot clear pedestrian path of travel on all sidewalks. City will consider a narrower dimension under certain circumstances.

• Tree pits should be 24 square feet at minimum, and are preferably four-feet wide and six-feet long. Narrower tree pits will be considered on a case-by-case basis, as long as the overall pit is 24 square feet.

• The tree species needs to fit the neighborhood, and there must be enough space for the tree to grow.

• The tree cannot interfere with power lines.

• The planting cannot be located in front of a building entrance.

We recommend that GAMS collaborate with property owners, especially those who own buildings consistently accessed by pedestrians on Dot Ave. (such as residential, retail, or restaurants), to determine possible spots for new trees. In scenarios where tree planting is possible, organizations like GAMS can apply for grants (up to $25,000) and technical assistance from the Boston Tree Alliance, a city program that supports community-based organizations and residents with tree planting and care projects. In addition, business and/or property owners and residents can “adopt” the tree to ensure that it grows and is adequately maintained. The Adopt-A-Tree program was created by the local nonprofit Speak for the Trees Boston in an effort to “build a sense of stewardship and connection between residents and trees.”

When city tree planting is not possible, GAMS and property owners can employ temporary shade strategies. Short-term shade strategies such as umbrellas and tents can have a major impact on pedestrian well-being. These seasonal shade structures can be installed as a one-off placemaking strategy, or on a consistent seasonal basis.

Temporary shade can be installed at parklets, plazas, intersections, murals, or curb extensions to make these public spaces more inviting and comfortable. Temporary shade can also be installed at existing bus stops or in conjunction with newer transportation infrastructure improvements to demonstrate the need for long-term or expanded shade strategies at high-ridership stops.

The City of Cambridge recently funded their campaign “Shade is Social Justice” through an Accelerating Climate Resiliency grant from the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC). With the support of this grant, the city was able to place temporary, artist-designed shade structures in two parks and one intersection. Each structure received $27,000 in funding.

Larger and more permanent investments in sidewalk infrastructure such as shade sails can be a reliable option for summer shading. These shades can be disassembled for the winter months, and would only need limited maintenance when in use. Smaller shade sails are useful for cooling sidewalks and buildings that get direct sunlight, creating comfortable outdoor spaces where pedestrians can linger and rest as they travel between businesses. Beyond sidewalks, cities such as Los Angeles have installed shade sails at large outdoor transportation centers, particularly those with street-level bus service like Ashmont.

The Shared Streets and Spaces Grant Program, administered by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation, is intended for use by municipalities to quickly implement improvements to plazas, sidewalks, curbs, streets, bus stops, parking areas, and other public spaces in support of public health, safe mobility, and strengthened commerce. The City of Boston is using funds it recieved from this program to implement green infrastructure and sidewalk improvements in other neighborhoods. This is a recurring funding source, so Ashmont may benefit from future allocations, at which point more

permanent shade infrastructure could be installed.

Signage and other methods of urban wayfinding can be far more useful than mere navigational tools for an individual user. A well-thought-out signage scheme is also a powerful way to create a unique brand or identity for a neighborhood. Spatially, it represents a community’s collective understanding of which specific destinations and elements of the urban environment are considered important. In short, wayfinding enables a neighborhood to become increasingly ‘legible’ to residents and visitors passing through.1

Ultimately, the goal of any wayfinding or signage system should be to enhance the connectivity of a neighborhood – an encouragement for people to explore it further and more frequently, and therefore enhance the area’s overall sense of vitality.

In the case of Dorchester Avenue, a wayfinding system could contribute to helping further ‘knit’ the Ashmont commercial corridor together. Moreover, strategically placed signs can promote a wide variety of uses for neighborhood residents that are in line with

1 The 5 Principles of Wayfinding Design JD.

the four objectives of the Greater Ashmont Main Streets Organization. These include:

• Promoting a culture of health and safety

• Diversifying the means of transit

• Increasing the accessibility of certain businesses along the corridor

• Elevating the identity of historical landmarks

It is also important to consider the importance of wayfinding and strategic signage in light of Ashmont’s identity as a transit hub. Each day, people from within and outside the neighborhood travel through the commercial corridor – including commuters, shoppers, tourists, and soon cyclists making use of the proposed Dorchester Greenway bicycle trail. A well-placed sign next to an exit off of the Greenway could help entice cyclists and pedestrians to visit some of the businesses along the commercial corridor. A similar consideration can be made for passengers and tourists arriving at Ashmont station looking for a promising avenue to explore or landmark to investigate.

Install wayfinding signs throughout the corridor to promote connectivity, accessibility, and safety. Possible locations to include in a wayfinding program are:

• Codman Square Library

• Codman Academy Charter School

• Ashmont Nursery School

• Roberts Playground

• Rev. Loesch Family Park

• Wellesley Park

• Hemenway Playground

• All Saints Parish

• Industrial School for Girls

• Dorchester Greenway entry/exit points

• Welles avenue

• Central avenue

• Ashmont Station

• Peabody Square

• Hairdressing salons

• Via Cannuccia

• El Barrio

• Phu Thin Market

Starting in 2021, the City of Boston’s Transportation Department worked extensively with the neighborhood of Egelston to redesign its central square. One aim of the redesign was to promote wayfinding measures in the neighborhood, and thereby encourage the use of multimodal transit options, increase pedestrian safety, and help broaden access to resources within the community.

The Department of Transportation hosted two community engagement meetings in November and December of 2021 to obtain community feedback on the type of destinations as well as the design of the signs. Community members listed transit hubs, shopping destinations, community centers, schools, health centers and parks as their top priority destinations.

complete wayfinding system for Egleston neighborhood was implemented in the spring of 2022.

Install mapboards and promotional signs at strategic intersections along the proposed Dorchester Greenway (e.g. Welles Avenue and Central Avenue) to help draw cyclists and tourists to the shops, restaurants and services on Dorchester Avenue (see page 36).

The Dorchester Greenway is a proposed cyclist and pedestrian pathway that would extend from Ashmont Station to Park Street on top of the MBTA’s Red Line. The project is part of the growing network of greenways around the City of Boston, which now has over 200 miles of connected green “links.”

GAMS has taken an active role in advancing this project, including convening a group of designers and residents in 2017 to begin conceptualizing the Greenway. An MBTA feasibility study of the Greenway began in 2023, which includes a structural analysis of the tunnel and examining the land ownership situation above it. The study is expected to conclude in the spring of 2025. If feasible, work will begin on both an immediate lowcost design plan as well as a longer-term plan for the upkeep and maintenance of the Greenway.

$3 million has been set aside to build the Dorchester Greenway after the planning process is complete.1 As a result, Ashmont may host many more cyclists and pedestrians on a daily basis. However, some wayfinding guidance should be given to cyclists and pedestrians to help them access the commercial corridor. This can be most efficiently done by placing map boards or signs at selected intersections between the Greenway and the roads that lead on Dorchester Avenue.

This year, the City of Somerville partnered with CultureHouse, a local nonprofit organization, to help provide a wayfinding connection between the new East Somerville MBTA station and Somerville’s key commercial areas such as Washington Street, which is a 15-minute walk from the station.

Among other measures, CultureHouse produced a map board locating the user in relation to the neighborhood, as well as showing pedestrian-friendly routes to the

1 T tunnel cap idea is gaining serious traction. Dorchester Reporter, 2024.

Somerville commercial area. Several colorful signs advertising local destinations and restaurants were posted along the fence next to the MBTA station. All of the signs were made to be multilingual, in which the information is provided in both English and Spanish.

Notably, CultureHouse has worked with the GAMS in the past – specifically, on community outreach with regards to the Dorchester Greenway. In the fall of 2024, CultureHouse held three community engagement meetings to collect feedback on the design of the greenway. It would be worth considering partnering with the group again to design a wayfinding strategy around the Ashmont/ Greenway connection.

In addition to greening and wayfinding, the Ashmont commercial corridor stands to benefit from additional sidewalk infrastructure such as human-scale lighting, street furniture, and business signage. With the understanding that things like public benches can encourage loitering and other unintended uses of public space, we recommend that street infrastructure improvements be implemented in areas where there is a known demand, and that any sidewalk improvements be strategically tailored to proven neighborhood needs.

Through our visits to Ashmont over the course of this project, we became interested in how our different recommendations for the commercial corridor might work together at the intersection of Lonsdale, Welles, and Dorchester Avenues.

While this intersection is less spacious and busy than Peabody Square, it is home to popular businesses and a well-used school bus stop, meaning pedestrians of all ages use the sidewalk throughout the day. The intersection is already well-designed, with a wide sidewalk on the eastern side of Dorchester Avenue and priority signalling for traffic and pedestrians. That said, we observed that many businesses do not have signs that

are visible from the sidewalk. Vehicles speed through the intersection, sometimes running lights, and there is no accommodation for bikers crossing the intersection. Children disembarking their school buses have to step into the street and cross between parked (sometimes idling) cars to get to the sidewalk, as their parents/guardians wait for them on an unshaded part of the sidewalk.1

These challenges can be addressed by:

1) Raising the intersection to to slow vehicle traffic and protect bikers and pedestrians

2) Installing sidewalk infrastructure such as shade, lighting, and benches to accommodate pedestrians and business patrons at all times of day

And with shorter-term improvements such as:

1) Partnering with business and property owners to place and maintain outdoor planters, street trees, and/or shade structures

2) Implementing pedestrian wayfinding and improving business visibility

1 Business owners can work with the City of Boston’s Office of Small Business Development to improve storefront design and signage. The ReStore Boston program is ongoing and provides both architectural and graphic design services to small businesses that qualify.

While Ashmont has a rich urban fabric, key parcels along the corridor are either vacant or host street-facing surface parking lots. This empty space creates what urban planner Jeff Speck refers to as “missing teeth” in a main street’s urban form. These gaps break up the liveliness of the street, often introducing a new curb cut and a potential collusion point between pedestrians and cars.1

Three underutilized sites along the corridor create a less hospitable pedestrian experience:

• Dunkin Donuts - 1931 Dorchester Ave

• Ann’s Laundry Parking Lot - 1836 Dorchester Ave

• The Braces Place Parking Lot - Dorchester Ave between Shepton Street & Edwin Street

However, other sites along the corridor are reactivating for housing and first-floor retail.

The Connelly Office parking lot at 1857 Dorchester Ave is slated to be redeveloped into 20 housing units and two ground-floor retail spaces. This five-story building has already received approval from the BPDA.

Additionally, the owner of the former US Petroleum car repair shop at 1742 Dorchester Ave is redeveloping the site according to local reporting. The four-story structure will - based on news from summer 2023feature 14 housing units and a ground-floor restaurant space. This development will also eliminate the street curb cut, redirecting traffic to six parking spots at the rear of the building. The BPDA approved the affordable housing agreement in late 2023 for this site.

Surface parking lots in neighborhood corridors can negatively impact both urban vibrancy and economic activity. These lots consume valuable space that could otherwise be used for more engaging, communityoriented developments that foster a sense of place and encourage pedestrian activity. The disruption in storefront continuity deters foot traffic, creating a less attractive corridor for both residents and retailers. These lots often contribute to urban heat islands and can increase stormwater runoff, placing additional strain on infrastructure and degrading water quality. Furthermore, the prioritization of vehicular storage over human-centric spaces undermines efforts to enhance walkability, which is integral to vibrant, resilient, and economically successful neighborhood corridors.

Pop-up events offer a flexible and creative way to transform underutilized spaces into vibrant community hubs by drawing foot traffic, stimulating economic activity, and enhancing community ties. These temporary events range from market stalls to art installations and cultural performances, providing opportunities for local entrepreneurs and artists to showcase their talents. Characterized by their transient nature, pop-ups can encompass various themes, including retail, food, art, music, and education, typically lasting from a single day to several weeks. They are designed to create a sense of urgency and excitement, encouraging immediate engagement from the community. Pop-ups serve as platforms for experimentation, allowing organizers to pilot initiatives before committing to longerterm property modifications.

Local design and community engagement firm CultureHouse hosted a community pop-up on a city-owned lot in Somerville’s Gilman Square from mid June to early September in 2024. The initiative aimed to transform a to-be developed site into a community hub. CultureHouse organized events including market days and cultural performances, attracting over 4,400 visitors over three months. Visitors were notably present during market days and events, with Thursday evenings and Saturday beer gardens being particularly popular times. The space offered amenities like hammocks and corn hole games, creating a welcoming environment for diverse activities. Feedback from programming partners and observations suggested that the pop-up filled an important civic space gap in the area. The City of Somerville utilized funds from the American Rescue Plan to support this effort. While the length, site size, and complexity of this pop-up is far greater than what one might imagine for a site within the Ashmont Area, this example and local expertise could be a valuable resource for GAMS.

The Boston Little Saigon Cultural District's 2024 Night Market, offers an interesting local reference point for main streets groups looking to energize their neighborhoods with cultural events. This vibrant outdoor festival takes place in Fields Corner and features a diverse array of entertainment, food vendors, artisan goods, and activities suitable for all ages. Inspired by traditional Vietnamese night markets, this event aims to create a sense of nostalgia for those familiar with Vietnam while introducing new cultural experiences to locals. By highlighting the rich culture and history of the Boston Little Saigon area, the night market serves as both a celebration and an invitation for community engagement, providing a valuable opportunity to spotlight and connect diverse audiences. With free admission and easy access via public transportation, this initiative illustrates how a community-centric event can bring vibrancy, economic stimulation, and cross-cultural appreciation to urban areas.

While the Little Saigon Night Market shuts down Dorchester Ave on one Saturday each summer, GAMs could draw inspiration from Little Saigon based on its proximity and

success. A smaller festival could use one of the identified parking lots for food vendors and seating on a weekend. For example, given that Phu Thinh is directly adjacent to the Ann’s Coin Laundry Parking lot, a Bahn Mi Pop-Up with other Vietnamese vendors from Dorchester Ave could prove a successful experiment to liven an underutilized spot.

• Define Objectives and Budget

• Secure Permission to use the private/ public land

• Design Layout

• Vendor Selection

• Apply for Temporary Food Vending License

• Develop and Implement Marketing for Event

Cost:

Range based on duration and ambition

$500-$10,000

Potential Partners:

• CultureHouse

• Phu Thinh

• Local food/craft vendors

Installing visual screeners on chain link fences provides several key benefits that can significantly enhance the aesthetics of a business corridor. By adding vibrant, welldesigned wraps or screens, you can transform an otherwise utilitarian and uninviting barrier into an appealing and cohesive visual element that complements the surrounding architecture and business signage. These screens can serve not only to block unsightly views and provide privacy but also to convey branding, promote events, or display art, thus creating a more engaging and welcoming environment for customers and passersby. Visual screeners can foster a sense of community pride and potentially attracting more foot traffic and business opportunities to the corridor.

• Determine optimal location for fence screening

• Gain permission of private property owner

• Collectively establish visuals, sizing, and maintenance plan

• Contract with fence screening company

• Install and secure with zip ties, etc.

Cost: $2-4 per square foot

50 foot fenceline = $400-800

Potential Partners:

• Ann’s Coin Laundry

• Connelly Realty

• 1813 Dorchester

• Vendors: Britten, SpeedPro Imaging

Potential Funding Sources:

• Property Owner

• Negotiated Agreement with Developer for During Construction Period

Precedent: 90 Washington Street

While the site will host a future public safety complex, this city-owned lot in Somerville is currently used for storing construction equipment and materials. The City of Somerville and Consigli Construction lined the fences that border the site with mesh visual screening. This mitigates the construction staging visuals from pedestrians and motorists on Washington Ave.

Murals can act as vibrant beacons attracting foot traffic to commercial corridors, potentially increasing consumer spending at local businesses. They enhance the visual appeal of an area, making it a destination for folks from outside of the neighborhood and encouraging local pride, which can lead to further investment in the neighborhood. Additionally, murals can provide opportunities for local artists, fostering a creative economy and supporting cultural industries that contribute to long-term economic development. The Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture (MOAC) outlines guidance for public art projects on privately-owned sites, emphasizing public access and experience. They encourage stakeholders such as site owners, curators, and artists to share details of their projects with MOAC for public records and potential promotion. If a site is available but lacks an artist, MOAC can help find one if the project aligns with their priorities and offers adequate compensation. They stress transparency and diversity in the artist selection process, suggesting the formation of a selection panel that includes various stakeholders.

Northeast corner of Dorchester and Shepton (2016 & 2022)

Source: Google Street View

Artist: Mattaya Fitts

Source: Google Street View

"Home is Here" was a summer youth art program led by artist-in-residence Yixuan Zeng, which took place in Dorchester, Massachusetts. The program, hosted by Urbano Project and supported by Brain Arts Org, involved 11 young artists who created a mural of life-sized monsters underneath the Red Line tracks. The project was divided into two parts: first, students practiced urban sketching and observational drawing, and then they translated those skills and their newfound spatial and social awareness into the physical mural. The program culminated in a public event where attendees could view the mural, an artist talk by the students, and a biographical exhibition of the project.

Implementation

1. Identify a high-visibility location

2. Determine ownership

3. Engage property ownership to discuss mural potential

4. Connect with potential organizational partners & community

5. Develop a proposal based on dimensions, budget, and maintenance plans

6. Seek Funding

7. Installation

8. Documentation and Promotion

Potential Partners:

• Urbano Project

• Dorchester Art Project

Cost: Approximately $5,000 (dependent on size, complexity)

Potential Funding Sources:

• City of Boston - Mayor’s Office of Arts and Culture

• Henderson Foundation (Mini-Grants Program)

• Community Benefits Payment from Development

Murals can inject community spirit and neighborhood identity into the public realm. Murals typically sit at the edge of a property, often abutted by separate property owners. However, what happens when the “viewshed” for a mural comes in conflict with redevelopment? Adjacent property owners are not legally bound by the artistic decisions of their neighbor. But clear property rights doesn’t prevent the neighborhood conflict that can arise in response to a mural’s disappearance beyond a new building.

This dynamic is a risk on walls facing developable land. Saving a mural that is painted directly on a building tends to be prohibitively expensive. However, this challenge can be avoided by installing portable panels. Panelized murals can hang from the side of a building, allowing them to be relocated if new uses on an adjacent parcel would cover the mural. A lightweight yet durable substrate, such as weather-resistant panels or fabric like canvas, that can withstand outdoor conditions. These materials should be prepared and sized appropriately to fit the mural space. Once the design is completed on these portable surfaces, they can be mounted using hooks or brackets that are designed for outdoor use

and can be easily removed. Ensuring the mural is securely fastened yet easily detachable is crucial; using modular components can also aid in efficient assembly and disassembly.

The Ashmont corridor has seen a considerable amount of new development over the past decade including, but not limited to, 1942 Dot Ave., 500 Talbot Ave, and 1980 Dorchester Ave. Additionally, development plans are underway for 1857 Dorchester Ave (the Connelly Real Estate site), the shuttered US Petroleum Station, and 1813 Dorchester Ave. This track record provides banks and other financial partners with comparables to illustrate how additional density could be successfully introduced to the corridor. However, restrictive zoning standards require that each potential project progress through an article 80 zoning variance process. While this increases costs for the developer - as well as the eventual tenants - developing to the current standards is economically infeasible.

New developments struggle to secure local, independently-owned retail due to pressure from financiers for “bankable” tenants. Existing small businesses that do not own their building or land have little recourse in the face of site redevelopment. Sites that are owned by an individual or firm operating a

retail business have a unique opportunity to benefit financially while maintaining their retail space.

Joe’s Smoke Shop was a one-story convenience store on Congress Street, Portland Maine’s key commercial corridor. Joe Discatio passed the eponymous business down through the family, and, 70 years later, Joe’s grandsons still operate the business. Joe’s is now in the first floor of a six-story mixed use building with almost 140 new housing units. The proprietors of Joe’s began talking to potential business partners about development opportunities to capitalize on the value in their more than 25,000 square foot lot. A unique partnership between Joe’s and Redfern Properties emerged. Redfern created a development plan that would keep Joe’s as a long-term tenant on the ground floor. Importantly, Joe’s owners would also receive a one-time cash payment, a payment for each month their store is closed, and equity in the new building. This means that the proprietors of Joe’s are now partial owners of the building and receive a portion of the net operating

income from the apartments. Joe’s represents a model by which local retails who own their building and adjacent land can continue to operate their business in the neighborhood while building more homes and increasing local vitality.

After years of struggling financials, University Baptist Church in Columbus, Ohio partnered with American Campus Communities to build a new student housing campus just north of Ohio State’s campus. The church will operate out of a new, renovated first floor space in the building. University Baptist Church was able to control the terms of the deal based on their property-based leverage. After the development is complete, the church will have a new space and more secure finances.

• Consider Upsides/Downsides of Redevelopment

• Engage Community-Based CDCs

• Evaluate Redevelopment Potential

• Develop Business Plan

• Secure Financing

• Execute Redevelopment

Potential Partners:

• Dorchester Bay Economic Development Corporation

• Asian Community Development Corporation

• Ann’s Coin Laundry

A final measure for helping promote pedestrian activity and increasing the connectivity of the commercial corridor is the creation of a neighborhood tour.

Creating a tour of the neighborhood would help highlight one of the most noticeable features of Greater Ashmont: the area’s incredibly diverse urban fabric. In addition to mixed uses, the architectural styles and ages of the buildings in the neighborhood vary tremendously, ranging from the late 19th century to modern-era developments. Indeed, this range contributes to a unique sense of history and character of place, and therefore can be considered one of the neighborhood’s greatest assets as it seeks to strengthen its identity as a cultural destination as well as a commercial corridor.