Projections 11

Global Ecologies: Politics, Planning, and Design

Founder

Eryn Deeming

Editors

Kian Goh

Eric Chu

Faculty Advisors

Amy Glasmeier

Lawrence J. Vale

Editorial Board

D. Michelle Addington

Gabriella Carolini

Roger Keil

David Pellow

Erik Swyngedouw

Layout

Alicia Rouault

Many thanks to Eran Ben-Joseph, head of the MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning, Lawrence J. Vale, chair of the PhD Committee, and Ezra Glenn. In memory of JoAnn Carmin.

© 2015 MIT Department of Urban Studies and Planning

Editorial - Global Ecologies: Politics, Planning, and Design Eric Chu and Kian Goh

Enclosure of the Commons in a Global Economy: British Enclosure and African Land Grabbing Suzanne Song

An “Insiteful” Comparison: Contentious Politics in Liquefied Natural Gas Facility Siting Hilary Schaffer Boudet

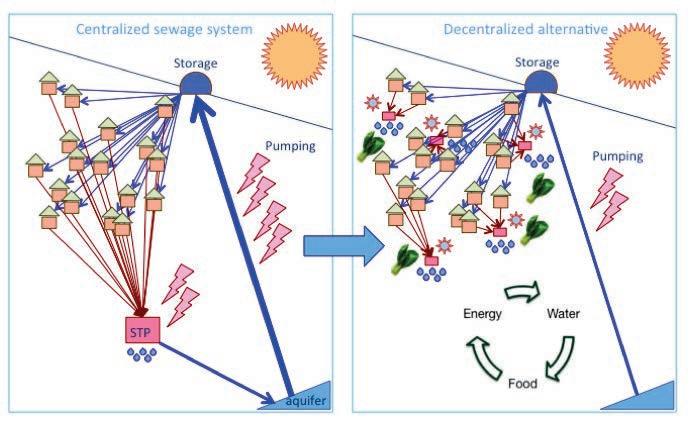

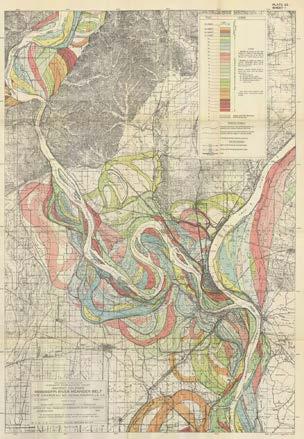

Down the Drain or Back to the Roots? Political Ecology of the Water-Energy-Food Nexus Visualized Using GIS in Leh Town, Ladakh, India Daphne Gondhalekar and Adris Akhtar

An Environmental Anthropology of Waste in Cairo: Contexts, Dimensions, and Trends Eman A. Lasheen

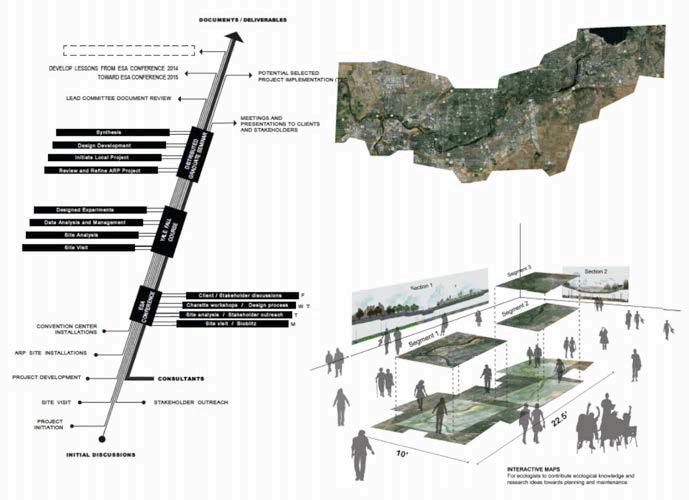

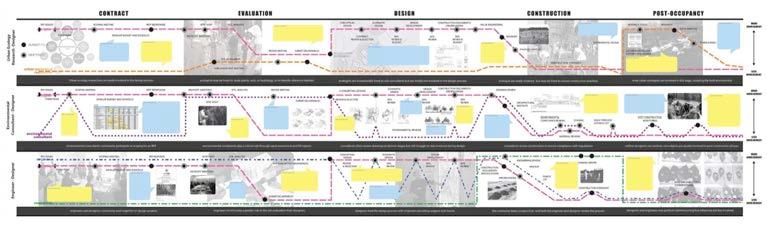

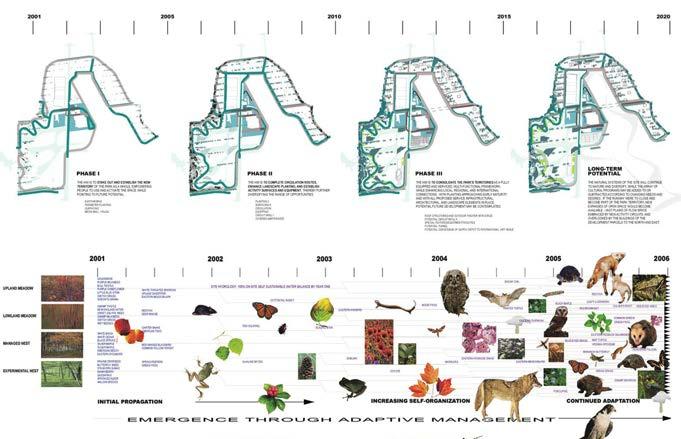

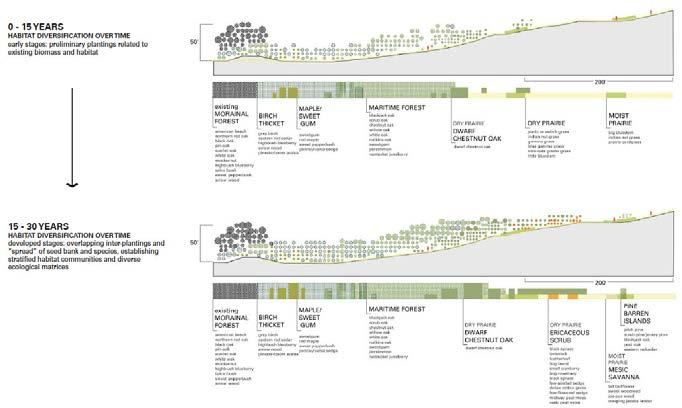

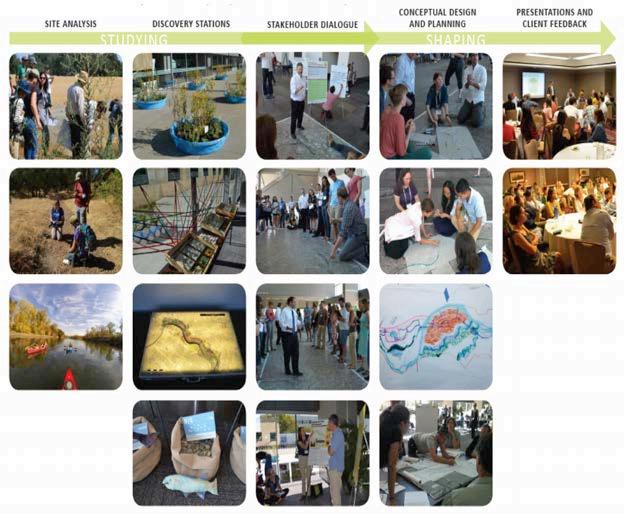

Designed Experiments for Transformational Learning: Forging New Opportunities Through the Integration of Ecological Research Into Design Alexander J. Felson

Freeland: Urban Planning Strategy for Almere Oosterwold Lachlan Anderson-Frank with Winy Maas/MVRDV

In Memoriam

Professor JoAnn Carmin

Cover image, “An Impressionistic Visualization of the Human Impact on the Earth’s Surface,” by Nikos Katsikis

Photographs of Jakarta, Indonesia, on pages 6, 19, 150, and 151 are courtesy of Etienne Turpin / anexact office

All other image credits as listed

Global Ecologies: Politics, Planning, and Design

Engagement in sustainability planning is growing globally, yet we continue to see environmental conditions worsen. Much attention has reasonably been centered on capacities of national actors and policies, but corresponding issues of scale(s), space, and agency have been largely unaddressed. For ex ample, scholars are just beginning to critically assess the interactive dynam ics between state, private, and civic organizations in facilitating collective en vironmental action; the role of global decision-making in shaping local policy action; and the critical interface between urban and ecological spaces and flows. As a result, the complexities and possibilities of state/local agency, global networks, and spatial ecologies as a multidimensional system remain under-theorized. This is particularly important in a time of global ecologies, where worldwide processes now actively transform society and nature every where. This issue of Projections directly addresses this critical intersection of politics, globalization, and built and “natural” environments. Our objec tive is to unearth the political and spatial dimensions of our environmental crisis, and to reassert the physical and environmental aspects of the study of urban politics and processes. The various articles included in this volume highlight key concepts and practices in sustainability planning that address the dynamic interrelationships of global urbanization, ecological change, and the emerging hybridities of society and nature.

Theories of human development and natural resource use are complex and contested. Scholars prioritize issues of technology, modernization, and in dustrial change, on the one hand, and nation-state political economies, and citizen and social movements, on the other (Rudel, Roberts, and Carmin 2011). The major schools of thought address problems and opportunities at different scales of global political economy. A critical, historical engage ment is necessary to understand and appreciate the implications of these

approaches for the challenges we confront today.

In the 1960s, scholars began to re-comprehend the effects of industrialization and resource-extractive economic production on the state of the global environment through ideas such as human exceptionalism, ecological impact theory, and the new ecological paradigm. Rachel Carson’s seminal work, Silent Spring (1962), successfully recast society’s conception of in dustrialization and development in terms of the ecological externalities and byproducts of modernization that were gradually being experienced by the public. Together with other works such as “Tragedy of the Commons” (Har din 1968) and “Impacts of Population Growth” (Ehrlich and Holdren 1971), Carson’s writing ushered in an era where the study of environmental issues and impacts reentered mainstream social theory. Dunlap and Catton (1979) helped to articulate the “Human Exceptionalism Paradigm,” which directly critiqued the notion that human societies, because of their ability to gener ate culture, technology, language, and organization, were exempt from eco logical principles and from environmental influences and constraints. These ideas formed the foundation of environmental sociology (and the study of the political economy of the environment), premised on the notion that so ciety must shed its anthropocentrism and accept that humans are subject to ecological laws just like other species (Buttel 1987; Dunlap and Catton 1979).

At the same time, authors like Giddens (1991) and Beck (1991) proposed the concept of the world risk society, characterized by a “second moder nity,” to address global ecological and economic dynamics or crises. Rather than articulating industrialization and modernization simply as processes of contestation between capitalist economics (for profit and production) and class (labor, in particular), the authors emphasized the relationship between modernization and the environment through the lens of risk, referring to a systematic way of dealing with hazards and insecurities induced and intro duced by modernization itself. According to this theory, modern societies take complex and deliberate risks, necessitating the reliance on scientists for interpretation of scientific knowledge. The problem faced by modern societ ies, therefore, is the loss of faith in the institutions of modernity and, eventu ally, in the prospect of modernizing reflexively.

In the policy realm, there has been an increasing recognition over the past several decades of the role of global politics and international institutions in addressing the contradictions between environmental protection and eco nomic development. The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (also known as the Rio Earth Summit) in 1992 set the founda tion for important global agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Framework Convention on Climate Change (Gupta 2014). Scholarship emanating from these global policy advances mostly notes that environmental politics must either be rescaled vertically down toward provin cial and municipal governments or up toward supranational regimes in order

to ensure effectiveness and accountability (Andonova and Mitchell 2010). Still, this global interconnectedness is not necessarily a new phenomenon, as scholars writing on world-systems theory and the environment have already been noting that the history of colonialism should be considered as the main cause of underdevelopment (Gould and Lewis 2008; Roberts and Grimes 2002). The message was that the major environmental problems of our time needed to be understood in relation to the dynamics of an evolv ing world system, such as global inequalities involving core and peripheral zones.

At the national scale, concepts of ecological modernization posit that the market and its main economic actors should not only be interpreted as forces that disturb the environment, but that major economic actors and market institutions can also work in favor of environmental reform (Mol and Janicke 2009). The theory contends that “when talking about ‘repairing’ the design fault of modern industrial modern production, ecological modern ization asks that environmental factors not only be taken into account, but also that they be are structurally ‘anchored’ in the reproduction of these institutional clusters of production and consumption” (Spaargaren, Mol, and Buttel 2006). Using Western European “environmental states” as exemplars, the assumption here is that a process of industrial innovation encouraged by a market economy and facilitated by an enabling and disciplinary state will ensure regulatory progress toward environmental protection (Blowers 1997; Hajer 1996). In the context of nations in the Global North, this theory suggests that the relationship between environment and development is no longer framed around the ills of industrialization, but rather on reforming and restructuring modes of development with regard to environmental laws and policies (Huber 2009), enabling dialogue and negotiation between an en vironmental bureaucratic state and private sector actors (Mol, Spaargaren, and Sonnenfeld 2009).

In contrast to ecological modernization, the theory of the treadmill of pro duction posits the existence of powerful tendencies within both the capitalist market system and the state toward capital-intensive expansionism (Gould, Pellow, and Schnaiberg 2008; Schnaiberg and Gould 2000). This results in “additions” (essentially pollution) and “withdrawals” (the depletion of nonrenewable resources) (Gould et al. 2008; Mol and Buttel 2002). The treadmill theory asserts that capitalist economic criteria remain at the foundation of decision-making about the design, performance, and evaluation of produc tion and consumption, thus forming a self-reinforcing “treadmill” of produc tion, consumption, and growth towards ever-expanding profits and returns on investments (Gould and Lewis 2008; Pellow and Brulle 2005). Social in stitutions of modern industrial society “lubricate” the treadmill (Gould et al. 2008). The root of the problem is the power of elite institutions to construct reality and define the environmental situation for the mass public, while ex ercising extraordinary material and structural power over both people and ecosystems.

Global Ecologies: Politics, Planning, and Design

Both ecological modernization and treadmill of production theories address state political economy, the role of private capitalist production, and the effects on the country’s politics and society. Both theories offer ideas that engage with civil society, such as reflexive modernization, environmental jus tice, and new social movements around the environment. However, these two nation-state level theories suggest a dichotomous conception of how (and under what circumstances) an environmental state forms and promulgates itself. For scholars of ecological modernization, the state and its associating political changes will give rise to private eco-efficiencies and overall envi ronmental reforms ( Mol and Buttel 2002; Buttel 2000). In contrast, tread mill theorists stress the profit-oriented practices of private economic actors, their autonomy relative to the state, and capitalists’ domination over other state interests (Schnaiberg, Pellow, and Weinberg 2002).

We see an opportunity – and an imperative – to rethink these two prevail ing concepts, particularly when economic production flows, civil society net works, and ecological risks and impacts are increasingly transnational. Fur thermore, theories of environment and development at the nation-state level derive its context and empirical support from a sample of countries over whelmingly represented by advanced capitalist and social democracies of Western Europe and North America (Blowers 1997). Many of these critiques draw on issues of environmental justice, social movements, and citizenship, as highlighted in the next section.

The literature on social movements and mobilization around issues of the environment is vast, especially at an age in which resistance against modern ization and development paradigms are pervasive (Castells 1984; Escobar 1995). Under globalization, local movements are mobilized to defend local traditions, enlarge local autonomy of civil society, and resist the intrusion of foreign ideas and global problems (Della Porta and Diani 1999). The study of environmental movements in the development context is couched in terms of cultural differences, territorial defense, and some measure of social and political autonomy (Escobar, Rocheleau, and Kothari 2002; Escobar 1998). Mobilization, therefore, is aimed at building new patterns of socialization and behaviors that are more conducive to democratic discursive designs (Eckersley 2004). Theorists of environmental movements, marginality, and citizenship sometimes also emphasize the important roles played by rural population and by marginalized social groups, such as women and tribal communities (Escobar et al. 2002; Omvedt 1993), who struggle to protect local ecologies for their basic needs and their unique cultural values. This literature is also highly critical of overly technocratic state interventions that are informed by Western ideas of development and modernity, and thus ig noring the “indigenous” knowledge systems and cultural practices employed

by these marginalized groups for ensuring livelihoods and protecting local environments (Rangan 1997; Scott 1999). Therefore, the goal of some of these environmental movements is to promote underlying concepts associated with ecologically responsible statehood (Eckersley 2004) and, eventu ally, leading to environmental and social justice in sustainable development (Van Der Heijden 1999).

Theories of environmental justice are premised on the notion that basic func tions of societies involve the production of both intense ecological harm and extensive social hierarchies. Ecological disorganization and environmen tal inequality and racism are fundamental to the project of modern nation building (Pellow 2007). The environmental justice movement is a political response to the deterioration of the conditions of everyday life as society reinforced existing social inequalities while exceeding the limits of growth (Pellow and Brulle 2005). The movement argues for distribution, recogni tion, participation and capabilities (Schlosberg 2004), and has sought to redefine environmentalism as much more integrated with the social needs of human populations while also challenging the capitalist growth economy (Pellow and Brulle 2005). Similarly, on the development side, theories on alternative development (and alternatives to development) stress the role of the rights of the marginalized and disempowered, local knowledge, and popular, grassroots movements (Escobar 1995; Friedmann 1992; Pieterse 1998). Both schools, therefore, harken back to the ideas of reflexive modern ization as presented by Giddens and Beck, and refer to an age where society is increasingly reflecting and mobilizing against the byproducts of modern industrialization and economic development.

We see ideas of environmental and green citizenship as an effective analyti cal tool to bridge the different scalar conceptions of environment and devel opment relationships that we have outlined. The concept of environmental citizenship portrays a certain level of embeddedness between state and civil society while reflecting on paths of development that attempt to balance environmental sustainability and responsible development (Dobson and Bell 2005; Eckersley 2004). On one hand, citizens engaging in the civic life of the state help to disseminate an ecological sensibility (Cornwall and Coelho 2007; Johnston 2011), empower residents, and contribute local knowledge and experience that would be prohibitively costly for outsiders to acquire (Evans 1996). On the other hand, the rationalization of state environmental functions can be fostered through the enrichment of embedded state-society networks with two key actors in civil society: environmental justice move ments and environmental knowledge professionals (Davidson and Frickel 2004). In order for state-based notions and practices of green democratic citizenship to be justified, one needs to cultivate civil society-based notions and practices of democratic citizenship. These civil society practices of envi ronmental citizenship focus on non-state authorized notions of ecology and development where action towards environment and development requires criticism and transformation of state structures and policies (Barry 2006).

Global Ecologies: Politics, Planning, and Design

At the same time, this process promotes synergy and interaction between the community, experts, and decision-makers (Khanna, Babu, and George 1999). The concept of green citizenship, we would argue, is a good tool to navigate theories of development and environment across these different scales because it pits the normative ideals of environmental sustainability and development against traditional conceptions of resource-intensive mod ernization.

Concepts of “sustainability” and “sustainable development” have been in stitutionalized in global development since the World Commission on Envi ronment and Development’s (WCED) “Our Common Future” report (1987), which defined sustainable development as “development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Most definitions of sustainability acknowledge the importance of promoting environmental integrity, social harmony, and eco nomic viability amongst and across places and spaces (Brown et al. 1987; Campbell 1996). Planning practice plays an important role in interrogating and conceptualizing the relationships between different scales of action as well as the actors and networks necessary to promote sustainability.

In an era of increasing global engagement in sustainability, the concept is increasingly being critiqued as being overly vague. Many scholars note that sustainability practice is often susceptible to “green washing,” or does not lead to transformative behavioral change to combat fundamental challenges such as global climate change. Traditional theories of ecological moderniza tion, production, and environmental justice are in a state of flux due to the emergence of new non-state actors, new ecological risks and vulnerabili ties, and new alternative sustainability practices outside traditional global or multilateral policy realms. Furthermore, many scholars argue that human society is on the cusp of entering the Anthropocene, a new geological era in which humans have become the primary driving force behind planetary change (Crutzen and Stoermer 2000; Parnell 2016; Steffen and Stafford Smith 2013; Steffen et al. 2011). As a result, planning theory and practice must be reconfigured in order to account for these emerging environmental actors, networks, and flows across rapidly changing and interacting scales of governance.

Planning, as a discipline, is particularly suited to this endeavor. Its normative lens, and its specific set of knowledge claims and methods – what ought to be, and how to get there from here – provide the means to understand, inter pret, and change (to broadly invoke Marx). Alongside, in this volume we also emphasize the role of spatial interventions – of design, broadly constituted. Planning scholarship, in particular around issues of environment and justice, have often reinforced divisions between social and spatial. In environmental

planning, for example, it has tended to draw a line between hard, engineered infrastructure, and measures that are more social and political in focus. Is sues of justice, at the same time, have regularly been considered outside the realm of physical planning, and of urban design – even as scholars rue the spatially unequal impacts of social and environmental injustice. And urban design as a field of planning is in need of exploration, and precision. It’s core theoretical lineages – from the modernist, functional CIAM movement to Kevin Lynch and Jane Jacobs’ views of urban social complexity – now show their limitations faced with a set of new, intertwined challenges of climate change, global urbanization, increasingly interconnected social movements, and the surge of megaprojects changing the urban world.

In this issue of Projections, the articles explore the reconfiguration of envi ronment and society relationships in an era of global ecologies. They include empirical studies of sites around the world, explorations in transdisciplinary research and engagement, and speculations on urban and environmental design interventions.

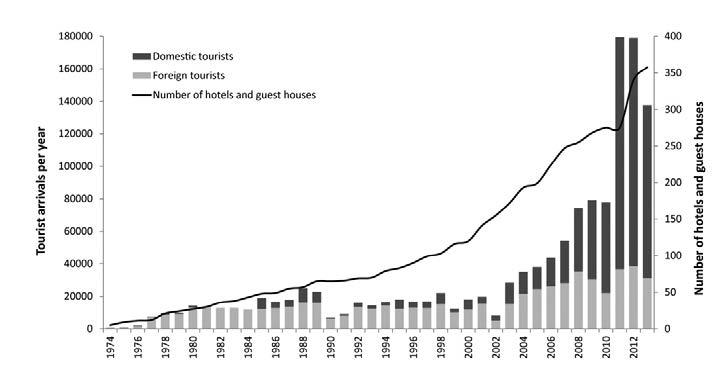

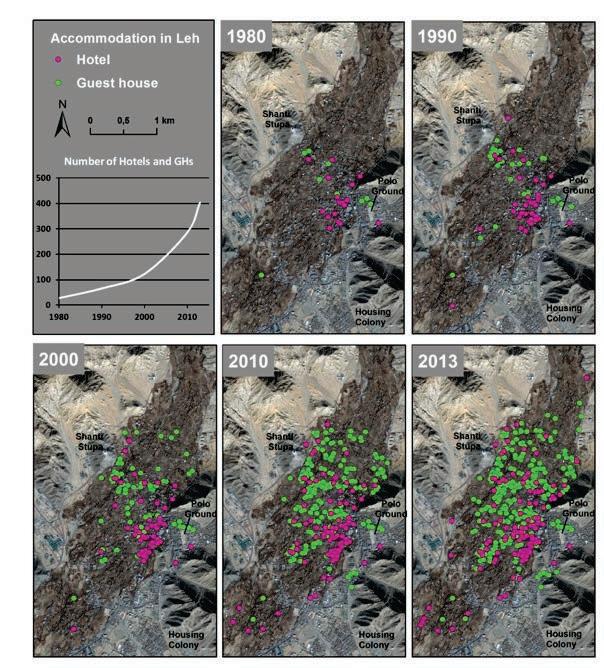

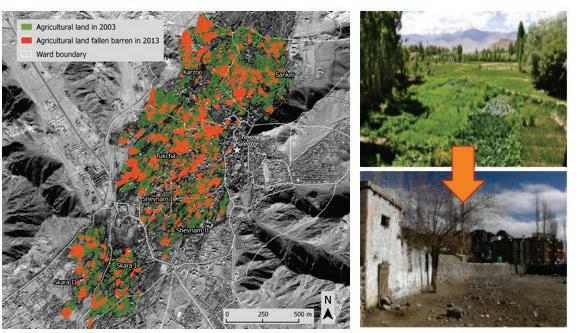

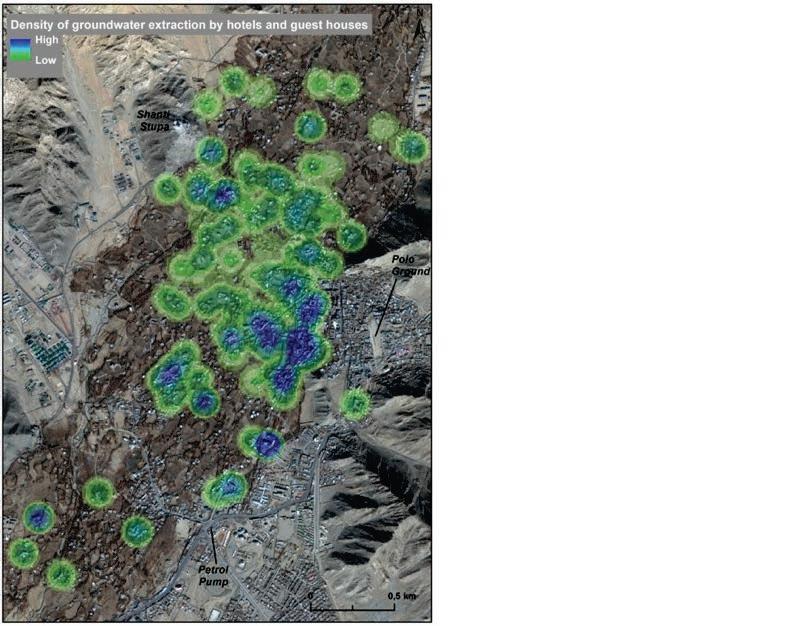

Beginning with a global, historical perspective, Suzanne Song explores the relationship between the British Enclosure movement and contemporary cases of land grabbing in Ethiopia. The author points out the role of for eign investment in African land grabs, in the context of global markets, and the importance of secure tenure and common pool resources in envision ing sustainable development. Then, Hilary Schaffer Boudet looks through the lens of social movements to analyze opposition to liquefied natural gas facilities in thirteen sites across the United States. Focusing on threat lev els, political opportunity, and internal resources, she probes the conditions for and pathways towards successful opposition strategies. Daphne Gond halekar and Adris Akhtar study the political ecology of water infrastructure in Ladakh, India, using field surveys and GIS analysis to study patterns of urbanization and resource degradation, and to propose alternative, more sustainable methods of development. Eman A. Lasheen probes the sociopo litical landscape of waste management in Cairo, Egypt, exploring the com plex social and cultural orders around the work of the Zabbaleen, informal waste pickers, amidst broader political and economic transitions. Alexander J. Felson proposes a method of combining the tools and strategies of urban and landscape design with modes of knowledge of scientific experiments, towards more effective urban ecological research and practice. And to end, Lachlan Anderson-Frank details the urban design and planning proposal for Almere Oosterwold, the Netherlands, by MVRDV. The Dutch architecture and urbanism firm’s proposal offers a new model for Dutch development, bal anced between collectivism and individualism. It is a 21st Century retelling of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City ideals, situated in an emerging context of global economic pressures and Dutch market liberalization.

In addition to the written articles, visual projects engage with the two ex tremes of scales, from the planetary to the local. The cover image, by Nikos

Global Ecologies: Politics, Planning, and Design

Katsikis, is “An Impressionistic Visualization of the Human Impact on the Earth’s Surface,” at the beginning of the 21st Century. Katsikis combines population density, land use patterns, transportation routes, and communications infrastructures to create a composite map depicting human impact on terrestrial and marine ecosystems. Interspersed throughout the volume, Etienne Turpin’s photographs of Jakarta, Indonesia, document the spatial, physical conditions connected to the ongoing debate around chronic, severe flooding and large-scale urban development.

Together, these articles and visualizations illuminate critical pathways to wards theories and methods to grapple with new global conditions.

Andonova, Liliana B. and Ronald B. Mitchell. 2010. “The Rescaling of Global Environ mental Politics.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 35(1):255–82.

Barry, John. 2006. “Resistance Is Fertile: From Environmental to Sustainability Citizenship.” Pp. 21–48 in Environmental Citizenship, edited by A. Dobson and D. Bell. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Beck, Ulrich. 1991. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Blowers, Andrew. 1997. “Environmental Policy: Ecological Modernization or the Risk Society?” Urban Studies 34(5-6):845–71.

Brown, Becky J., Mark E. Hanson, Diana M. Liverman, and Robert W. Merideth, Jr. 1987. “Global Sustainability: Toward Definition.” Environmental Management 11(6):713–19.

Buttel, Frederick H. 1987. “New Directions in Environmental Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 13(1):465–88.

Buttel, Frederick H. 2000. “Ecological Modernization as Social Theory.” Geoforum 31(1):57–65.

Campbell, Scott. 1996. “Green Cities, Growing Cities, Just Cities?: Urban Planning and the Contradictions of Sustainable Development.” Journal of the American Planning Association 62(3):296–312.

Carson, Rachel. 1962. Silent Spring. New York: Houghton Mifflin. Castells, Manuel. 1984. The City and the Grassroots: A Cross-Cultural Theory of Urban Social Movements. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cornwall, Andrea and Vera Schatten Coelho, eds. 2007. Spaces for Change?: The Politics of Citizen Participation in New Democratic Arenas. Zed Books.

Crutzen, Paul J., and Eugene F. Stoermer. 2000. “The Anthropocene.” Global Change Newsletter 41 (1): 17–18.

Davidson, Debra J. and Scott Frickel. 2004. “Understanding Environmental Gover nance: A Critical Review.” Organization & Environment 17(4):471–92.

Della Porta, Donatella and Mario Diani. 1999. Social Movements: An Introduction. Malden, MA and Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing.

Dobson, Andrew and Derek Bell. 2005. Environmental Citizenship. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Dunlap, Riley E. and William R. Catton. 1979. “Environmental Sociology.” Annual Review of Sociology 5(1):243–73.

Global Ecologies: Politics, Planning, and Design

Eckersley, Robin. 2004. The Green State: Rethinking Democracy and Sovereignty. Cam bridge, MA: MIT Press.

Ehrlich, Paul R. and John P. Holdren. 1971. “Impact of Population Growth.” Science 171(3977):1212–17.

Escobar, Arturo. 1995. Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Escobar, Arturo. 1998. “Whose Knowledge, Whose Nature? Biodiversity, Conservation, and the Political Ecology of Social Movements.” Journal of Political Ecology 5:53–82.

Escobar, Arturo, Diane Rocheleau, and Smitu Kothari. 2002. “Environmental Social Movements and the Politics of Place.” Development 45(1):28–53.

Evans, Peter. 1996. “Government Action, Social Capital and Development: Reviewing the Evidence on Synergy.” World Development 24(6):1119–32.

Friedmann, John. 1992. Empowerment: The Politics of Alternative Development. Cambridge, UK: Blackwell.

Giddens, Anthony. 1991. The Consequences of Modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Gould, Kenneth Alan and Tammy L. Lewis. 2008. Twenty Lessons in Environmental Sociology. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, USA.

Gould, Kenneth Alan, David N. Pellow, and Allan Schnaiberg. 2008. The Treadmill of Production: Injustice and Unsustainability in the Global Economy. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Gupta, Joyeeta. 2014. The History of Global Climate Governance. London and New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hajer, Maarten A. 1996. “Ecological Modernization as Cultural Politics.” Pp. 246–68 in Risk Environment and Modernity: Towards a New Ecology, vol. 5, edited by S. Lash, B. Szerszynski, and B. Wynne. Sage.

Hardin, Garrett. 1968. “The Trajedy of the Commons.” Science 162:1243–48.

Huber, Joseph. 2009. “Ecological Modernization: Beyond Scarcity and Bureaucracy.” Pp. 42–55 in The Ecological Modernisation Reader: Environmental Reform in Theory and Practice, edited by A. P. J. Mol, D. A. Sonnenfeld, and G. Spaargaren. London and New York: Routledge.

Johnston, Hank. 2011. States and Social Movements. Polity Press.

Khanna, P., P. Ram Babu, and M. Suju George. 1999. “Carrying-Capacity as a Basis for Sustainable Development: A Case Study of National Capital Region in India.” Progress in Planning 52:101–66.

Mol, Arthur P. J. and Frederick H. Buttel. 2002. The Environmental State Under Pres-

sure. edited by A. P. J. Mol and F. H. Buttel. Oxford: Emerald Group Publishing.

Mol, Arthur P. J. and Martin Janicke. 2009. “The Origins and Theoretical Founda tions of Ecological Modernisation Theory.” Pp. 17–27 in The Ecological Modernisation Reader. Environmental Reform in Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge.

Mol, Arthur P. J., Gert Spaargaren, and D. A. Sonnenfeld. 2009. “Ecological Moderni sation: Three Decades of Policy, Practice and Theoretical Reflection.” Pp. 3–16 in The Ecological Modernisation Reader. Environmental reform in theory and practice. New York: Routledge.

Omvedt, Gail. 1993. Reinventing Revolution: New Social Movements and Socialist Traditions in India. New York: East Gate.

Parnell, Susan. 2016. “Defining a Global Urban Development Agenda.” World Development 78:529–40.

Pellow, David N. 2007. Resisting Global Toxics: Transnational Movements for Environmental Justice. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Pellow, David N. and Robert J. Brulle. 2005. “Power, Justice, and the Environment: Toward Critical Environmental Justice Studies.” Pp. 1–53 in Power, Justice, and the Environment: A Critical Appraisal of the Environmental Justice Movement, edited by D. N. Pellow and R. J. Brulle. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Pieterse, Jan Nederveen. 1998. “My Paradigm or Yours? Alternative Development, Post-Development, Reflexive Development.” Development and Change 29(2):343–73.

Rangan, H. 1997. “Indian Environmentalism and the Question of the State: Problems and Prospects for Sustainable Development.” Environment and Planning A 29:2129–43.

Roberts, J. Timmons and Peter E. Grimes. 2002. “World-System Theory and the Environment: Toward a New Synthesis.” Pp. 167–94 in Sociological Theory and the Environment: Classical Foundations, Contemporary Insights, edited by R. E. Dunlap, F. H. Buttel, P. Dickens, and A. Gijswijt. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Rudel, Thomas K., J. Timmons Roberts, and JoAnn Carmin. 2011. “Political Economy of the Environment.” Annual Review of Sociology 37(1):221–38.

Schlosberg, David. 2004. “Reconceiving Environmental Justice: Global Movements And Political Theories.” Environmental Politics 13(3):517–40.

Schnaiberg, Allan and Kenneth Alan Gould. 2000. Environment and Society : The Enduring Conflict. Caldwell, NJ: The Blackburn Press.

Schnaiberg, Allan, David N. Pellow, and Adam Weinberg. 2002. “The Treadmill of Production and the Environmental State.” Pp. 15–32 in The Environmental State Under Pressure, edited by A. P. J. Mol and F. H. Buttel. Oxford: Elsevier.

Scott, James C. 1999. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven CT: Yale University Press.

Global Ecologies: Politics, Planning, and Design

Spaargaren, Gert, Arthur P. J. Mol, and Frederick H. Buttel. 2006. Governing Environmental Flows: Global Challenges to Social Theory. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Steffen, Will et al. 2011. “The Anthropocene: From Global Change to Planetary Stew ardship.” AMBIO 40(7):739–61.

Steffen, Will and Mark Stafford Smith. 2013. “Planetary Boundaries, Equity and Global Sustainability: Why Wealthy Countries Could Benefit from More Equity.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 5(3-4):403–8.

Van Der Heijden, Hein-Anton. 1999. “Environmental Movements, Ecological Moderni sation and Political Opportunity Structures.” Environmental Politics 8(1):199–221.

World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED). 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

This paper explores the enclosure of common land in predominantly agrar ian economies where poor rural inhabitants are disproportionally affected. The relentless, capitalist drive to privatize land through what Harvey terms ‘accumulation by dispossession’ is compared and contrasted through two examples; historical British Enclosure and contemporary African Land Grab bing. The analysis examines the national globalization policies implemented that argue economic development, applies the framework of sustainable de velopment to (a) policy impacts on the poor (b) modes of collective action as reactions (c) possible strategic approaches to explore planning alterna tives in Ethiopia to resist processes of accumulation by dispossession. The unsustainable impacts of impoverishment, food insecurity, marginalization, and migration similarly characterize both the historical and contemporary cases of enclosure. Land degradation and resource overuse are additional factors in the delicate Sub-Saharan environment that are a profound deter minant on the fragile conditions necessary for livelihood and environmental sustainability. Land grabbing exacerbates the decreasing supply of produc tive resources available to farmers. Secure tenure and access to common pool resources (CPRs) are critical for sustainable development. Collective ac tion through the cooperative movement in England mobilized internal class struggles that resisted capitalist accumulation through enabled competition in a globalized free market. The growing cooperative movement in Africa is developing competitive potential but land grabbing is embedded at the global level of neo-liberal politics and needs sustained multi-scalar support by international coalitions. An alternative planning model is discussed that combines cooperatives and CPRs to strategically secure land and incorpo rate socioeconomic, sociopolitical and environmental development that di rectly engages rural communities.

Keywords Sustainable development, rural-urban migration, globalization, accumulation by dispossession, cooperatives, commons

This paper explores the enclosure of common land in predominantly agrar ian economies where poor rural inhabitants are disproportionally affected. The relentless, capitalist drive to privatize land through what Harvey terms ‘accumulation by dispossession’ is compared and contrasted through two examples; historical British Enclosure and contemporary African Land Grab bing.

The analysis aims to indicate a possible strategic approach integrating the balanced dimensions of sustainable planning in Ethiopia where land, owned by the federal state, as a productive input to the developing economy and a source of livelihood to poor farmers is critical. The dialectic framework addresses the interdependence of complex drivers and impacts of devel opment and suggests a practical planning model based on combining co operatives and common pool resources (CPRs) that would directly engage rural communities, secure land tenure, mobilize collective action to foster socioeconomic and political development, and aid in resisting environmental resource overuse and degradation. Deterring land grabbing by foreign capital and its domestic facilitation would need to be addressed in conjunction with sustained multi-scalar support of international coalitions.

The well-known historical example of British enclosure occurred during the vast demographic change from the 17th to early 19th centuries when popu lation doubled from 1750- 1850 from 11 million to 21 million people (Voth, 2003, p.224; Redford, 1964, p.14) and GDP in the UK rose from £72.6 mil lion to £323.18 million2 Government supported enclosure policy enabled the shift from a rural agricultural to urban industrial economy that facilitated landowner profits from globalized trade and simultaneously contributed to the rise of poverty, ‘paupers and vagrants’ and exacerbated rural-urban mi gration. At that time,3 arguments that claimed enclosure would benefit na tional economic development by increased food production and agricultural efficiency were used to implement governmental policy through the Parlia mentary Inclosure Acts, peaking from 1750-1820 when over 3,800 acts en closed about 7 million acres (2.83 million hectares) of common open field arable, pasture and waste land or approximately 20% of the surface area of the country and transferred use rights solely to private owners (Turner, 1980, p.324; Makki & Geisler, 2011, p.4). In 1500 45% of the land was enclosed, in 1700 61%, by 1914 it was 95% enclosed (Allen, 1994, p.98).

Today, in the case of Sub-Saharan Africa and Ethiopia, drought and crop failure contribute to susceptibility to poverty and famine, predominantly af

“…Urbanism is the mode of appropriation of the natural and human environment by capitalism…”

- Guy Debord1

fecting the rural poor. Ethiopia’s population more than doubled from 1975 to 2011 from 33 million to 84.7 million people.5 From 1994 to 2007 the national population growth rate averaged 2.6% though was slightly lower for the urban population of 12 million than the rural population of 62 million.6 Per capita GDP in 1974 is estimated at $110,7 it rose from $636 in 2005 to $979 in 2011 while annual per capita GDP growth fell from 9.2% to 5% in the same period. Government supported policies target economic develop ment through strategic neo-liberal directives that seek private capital investment to transform a smallholder agricultural to an industrialized agricultural economy. The argument of developing the agro-industry by attracting foreign investment capital spurs policy facilitating the transfer of large-scale tracts of agricultural land to foreigners but precludes meeting such domestic de velopment goals. The impacts of land grabbing that disproportionately dis possess poor farmers of common resources exacerbate decreased domestic productive land supply and water resources that impact domestic food secu rity, rural-urban migration, and threats to the environment.

Similar conditions of demographic growth, the targeted shift from an agri cultural to an industrial economy, and policies supporting capitalist accumu lation by dispossession can be traced in both the historical case of Britain and contemporary Ethiopia. Similar effects of globalization that exacerbate poverty, food insecurity, rural-urban migration, and marginalization also characterize both cases. But in the case of England, capitalist accumulation by dispossession was driven by profit-seeking in the emerging industrialized market of globally traded goods and reinforced by governmental policy that privileged domestic land owners returns. It materialized as internal struggles in class politics between landowners, merchants, landless commoners and laborers. While in the case of Ethiopia, capitalist accumulation by disposses sion is embedded in neo-liberal global politics that privileges foreign capital seeking new resources and returns (Harvey, 2004, 2006). Any shifts in do mestic internal class politics are stymied by lack of simultaneous social and economic development, lack of a peasant material base of land and capital, lack of alternatives for livelihood in industrialized sectors and the fragile ecological conditions of environmental degradation impacting food security in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The loss of common land in the manorial open field system during the time of British enclosure meant the loss of sources of food, fuel and income lead ing many to poverty. Neeson (1993) described how milk from a single cow turned out onto common pasture or waste totaled about half of a laborer’s yearly wages. Income from a calf sold at market would substantially cover rent and land tax for the year (Neeson, p.311). Corn from four acres of arable land would feed a family for an entire year.8 Governing of the commons tied

the amount of arable land rented to the number of animals allowable to pas ture. Sheep, cheaper to buy and maintain than cows, additionally provided wool, milk and lambs. Supplemental food and surplus income were lost from game hunting, fishing, berry and nut picking on common woodlands, fallow, marsh and waste. Common land use provided subsistence and livelihood in an economy where the overwhelming expense was food (Neeson, p.313). Sources of fuel, fodder and household materials were lost- dry fallen wood, dead leaves, furze, peat, reeds, rushes, and gleanings were no longer available. Comparatively, the loss of fuel sources became more valuable as coal became an available substitute that was unaffordable for most commoners.

Food shortages were common during the period of accelerated enclosures after 1750 from rising market prices, especially from blocked trade during the American War of Independence from 1775-1783 and Napoleonic Wars from 1803-1814 (Allen, 1994, p.97; Allen 1999, p. 217).

After 1800, trade fed the expanding British population with rising consump tion and demand for cheaper imported goods. But the rising domestic mo nopoly grain prices that protected British landowners and merchants from foreign competition through the Corn Laws of 1815-1846 and the financial Panic of 1837 led to grievous depression in ‘the hungry forties’.

Unemployment grew parallel to rising food prices. As sectorial shifts and global market conditions shifted around 1760 (Clark, 1998), relative profit ability turned in the favor of privatized land9 and enclosures surged as raising agricultural crops (open fields) shifted to sheep (fenced-in fields) for wool as a raw good for industrial production. Wool exports were high at this time although prices varied depending on quality high (Bowden, 1952). As raising crops was more labor intensive than raising sheep, where only one shepherd tended an entire flock, unemployment rose. The labor oversup ply was compounded by increased population and decreased real wages that limited the ability to buy food. Total pastoral output increased while arable10 decreased in the latter half of the 18th century and then switched the first half of the 19th century (Broadberry et al., 2010, p.43) as raising crops or livestock shifted depending on prices for corn, wool11 and meat (Redford, 1964, p.70-71).

Rural-urban migration in pursuit of a better livelihood resulted as a third order effect from the conversion of arable land to pasture based on labor oversupply, unemployment and poverty. Even with overall population growth through the 19th century,12 most accounts described emptying villages. Oth ers stated that agricultural labor was abundant and that migration was de terred by the Poor Laws 160113-183414 and that the “rural population was increasing in an unhealthy fashion” (Redford, 1964, p.68). Internment of

the poor enacted with the Workhouse Test Act of 1723 aimed to stem ruralurban migration and relieve urban tax pressure of poor relief but served to spatially marginalize the growing poor population at the urban periphery as Green (2010) illustrated in London. Depopulation of rural areas occurred due to attraction of higher real wages15 in urban manufacturing centers (Red ford, 1964, p.67) even though the conversion of land from waste and marsh to enclosed arable and pasture was labor-intensive (Turner, 1980)

Intense town growth in the postwar years between 1821 and 1831 occurred coupled with migration to manufacturing centers located in different regions driven by expansive export growth by sequential concentrations of wool, lin en, cotton, and silk goods (Redford, 1964 p.66). An increased flow of raw materials produced or imported, including cotton imports from the cheap slave labor from new world plantations (Blackburn cited by Makki & Geisler, 2011, p.4), manufactured and sold domestically and internationally was due to market growth in international trade and by 1839 textiles totaled 72% of UK exports (Freeman & Louca, 2002, p.22).

Other factors that affected wage and sticky migration was the influx of Irish handloom weavers from 1826-1833 that accepted starvation wages and crowded out the higher skilled British weavers,16 giving local workers false hope of employment at the factories that stayed open (Redford, p.41-42, p.125) and in hinterlands surrounding growing towns, where workers were attracted to higher wages in industry, agricultural workers were scarce and therefore earned the highest real wages (Redford, p.68).17

It was rumored that enclosure would double or triple rent (Clark, p.74) but according to Allen (1994, p, 119) the rent gain of 23% on enclosed land was attributable to converting waste to productive land and not to higher produc tivity. Young in the late 1760s and later Lord Ernle (1936) used the argument that enclosure of arable land increased farm efficiency and productivity to influence policy (Allen, 1994). Young professed that agricultural improve ment depended on the shift to large-scale farming that would consolidate the small strips of land (Figure b.optional) farmed by commoners into large crop areas (cited by Allen, 1999,p. 209). Although there is some debate among scholars, empirical data showed enclosed land was not more efficient. Al len’s research showed that small-scale peasant farming was as efficient as large-scale capitalist farming and in the 1770s common open field farms were more efficient than enclosed farms (1982, p.950). Although, there may have been marginal increases in productivity and output, claims for gains were grossly exaggerated. He illustrated that during the main period of Par liamentary Inclosure, agriculture was stagnant in terms of productivity and output (1999, p.209).

According to Allen (1982, p.37, p.951) enclosure was rather a mechanism of state sponsored land reform to bring rent from common open field to market

price. The main effect of enclosure was to redistribute income from farm ers to rich land owners (Yelling cited by Allen, 1982, p.950-951). Wealthy landowners who benefitted from rent increases from enclosure had political power and enacted parliamentary policies in their own favor.

Other arguments given by improvers supporting enclosure in the 18th cen tury were: adoption of better crops- deterred by collective management of fields that were dependent on consensus; suppression of animal diseases; and better control of breeding and overgrazing (Allen, 1994). Common field practices were not as ‘backward’ as enclosure advocates claimed, open field villages adopted new crops when profitable although enclosed villages ad opted new methods more fully (Allen, 1994, p.115). Neeson described in de tail how commoners’ livelihood was at stake and for their own best interest, vigilantly monitored for disease, separated animals from the common herd when exposed to markets, and bred and pastured rams and bulls separately (1993, p.122-133). Although Hardin in “The Tragedy of the Commons” in 1968 used common pasture as an example of overuse, according to Neeson (2003), English commons were actually a successful example of equitable distribution of benefits and stemming degradation through stringent stinting regulations and participation of those who were intimately knowledgeable in local practices. The accounts of overstocking were typically of rich farm ers seeking profit and tactically aimed to reduce the compensation owed to commoners at enclosure (Neeson, 2003, p. 88).18 The small scale farming practices and local know-how reflect Ostrom’s (1990) similarities among en during, self-governing CPR institutions.

Although Marx first coined the term, land grabbing is defined by White as the large-scale acquisition of land or land related rights and resources by cor porate entities (business, non-profit or public) that creates dispossession of land, water, forests and other common property resources, their concentra tion, privatization and transactions as corporate property- owned or leased, and in turn the transformation of agrarian labor regimes.19

A report on global land grabbing states that 43% of all large-scale land ac quisitions target land already in use for farming by local communities, has a relatively high population density, is easily accessible by transportation and is in fact land for which local farmers compete. Land grabbing of forested land (24% of the deals) and open and closed shrub land/grassland (28% of the deals) also impact the environment and food security (CDE, 2011, p.17). The increasing commercial pressure on land, its increasing price, and the cheap capital offered to foreign-owned capitalist farms favor land grabbing by foreigners, handicaps domestic producers and crowds out lo cal entrepreneurship (De Schutter, 2011; Rahmato, 2011). According to De

Schutter (2011, p.1) “land grabbing increases susceptibility to food price shocks; reduces the land and water access that would reduce poverty; and is destructive to the livelihood of groups depending on common grazing, fishing grounds, and forests.” More than a dozen African countries have given millions of hectares of farmland to foreign investors in the hopes of spurring agrarian development (Rahmato, 2011, p.2).

According to Rahmato, the Ethiopian government has already transferred about 3.5 million hectares of land to foreign investors with a similar amount slated for the next five years (2011, p.25). The nearly 7 million total hectares of land slated for transfer comprises about 38% of land currently used by smallholders (2011, p.12) and often has use rights belonging to individu als and communities, resulting in smallholder dispossession and threatened livelihoods (2011, p.4-5). Ascertaining exact amounts of common land given over to foreign capital is difficult as land registration is an ongoing process. From 2006 building up to 2008 there was a boom of large-scale land trans fers for cut flower exports (2011, p.12). Cotton, food crops (rice, maize, pulses, oil seeds-sesame) and biofuel crops (palm oil trees, jatropha curcas, and castor oil trees) are the main investment interests (2011, p.13). Sugar cane can be used for either food or biofuel.

Poverty, Agricultural Economics and Food Insecurity

Ethiopia, one of the 34 Least Developed Countries (LDCs) in Africa of the 49 listed by the United Nations (UN), has the characteristics of: low level of socio-economic development, low and unequally distributed income, low productivity and low capital investment based on a largely agrarian economy, earnings mainly from export of a few primary commodities, little diversifica tion into the manufacturing sector, and political instability and conflicts.20 Income per capita is about one third of the current Sub-Saharan average and about 29% of the rural population (26.8 million people) lives below the national poverty line21 even though economic growth has been fairly high and health services have improved in the last decade (Rahmato, 2011, p.3).

Agriculture accounts for half of the GDP and 90% of export earnings of which coffee is a major source (Assefa, 2007). Crop production of cereals accounts for a majority of agricultural GDP with livestock production con tributing over a quarter as well (Walton, 2006). Smallholders produce 95% of the agricultural GDP that is predominantly subsistence rain fed farming.22 Ethiopia is highly vulnerable to external global terms-of-trade shocks and has periodically encountered food shortages, famine and received food aid from NGOs.23 More than 50% of the gross capital formation of the Gross National Income (GNI) in Ethiopia is financed by aid. The food crisis of 20062008 showed that African countries that are most reliant on food imports are the least resilient to food price shocks (FAO, 2009; Zoomers, 2010, p.434). The complex factors contributing to Ethiopia’s low development and vulner ability are attributed to a combination of: ineffective and inefficient agri cultural marketing systems, underdeveloped transport and communications

networks, underdeveloped production technologies, limited access of rural households to support services, environmental degradation, lack of partici pation by poor rural people in decisions that affect their livelihoods, climatic conditions, a lack of basic infrastructure such as health and education facili ties, and safe drinking water.24

Lack of available sufficiently productive land is the most common cause of the complex phenomenon of rural-urban migration as poor populations seek a means to obtain income and food (UN, 2011). The growing poor urban population drives expansion of built areas into cheaper agricultural hinter land exacerbating the lack of productive land for food production.25 Ruralurban migration and expanding urbanization exacerbates living conditions and competition for livelihood for both poor rural and urban populations.26 As residence is a requirement for securing land tenure it may prevent rural migration (Rahmato, 2011). The periodic food shortages, natural disasters such as drought, and price spikes in the global food commodities market increase migration and forced local displacement. Farmland is characterized by poor soil nutrients27 and is sensitive to degradation and erosion through agricultural practices that further decrease the supply of productive farmland. Land grabbing exacerbates the decreasing supply of productive farm land available for domestic livelihood (Rahmato, 2011, p.25).

Hardin’s 1968 “The Tragedy of the Commons” that linked open-access to free rider behavior and ecological impacts of overuse, falls short of describ ing the complex environmental degradation of the fragile ecosystem of natu ral resources in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Ethiopia neither private nor public ownership of natural resources have stemmed the environmental degrada tion now in crisis due to deforestation, overgrazing, soil nutrient depletion, soil erosion, and desertification that is based on the interdependence of natural, socioeconomic, and political systems (Taddese, 2001). The great est contributor to land erosion is dryland cropping28 while other large-scale farming practices29 impact the precarious conditions of degradation. Largescale farming practices by foreign capitalists, such as monocropping that induces low nutrient recycling and low soil fertility, further exacerbate envi ronmental degradation.

Large-scale farming irrigation systems can reduce the existing water supply for smallholders and the flooding watershed can be lost when control is given over to capitalist foreign investors.30 Large-scale farming could also contrib ute to increasing water pollution in Africa, as environmental practices are not well regulated.31 Fighting land degradation, desertification and mitigating the effects of drought are essential for the economic growth and social prog ress of smallholders who are dependent on common resources.32 Capital investment by farmers, such as tree planting, which is expensive but would combat erosion, decreases with unsecure tenure (Taddese, 2001, p.822).

The structure of land ownership in Ethiopia has historically been tied to the changing political regime. Under the communist rule of the Marxist Derg Regime, that via popular uprising in 1974 overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie I’s monarchic rule, the lack of public investment into state nationalized land resulted in declines in productivity, soil degradation, erosion and an incapac ity to support the growing population (Deininger, et al., 2007). After the Derg Regime was overthrown in 199133 following the end of aid contributions from the fallen Soviet Regime, the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) enacted reforms in 1997 and 2005 claiming federal owner ship of all land that then transferred rights to lease it to regional authorities. The Ethiopian government claims that ‘unused’ or public lands that do not belong to anyone can be used for the greater national good to bring in hard currency by efficient large-scale foreign investors.

Security of tenure, as Rahmato stated, is not robust as centralized state ownership can remove landholders at any time, does so without their par ticipation, and even when compensation is paid it is unfair and inadequate (2011, p.6-7). Peasants fear the loss of land that they consider common property, its resources, and means of livelihood (2011, p. 21). They value prime forestland34 more than possible new employment opportunities that are generated when it is cleared.35 Regional differences play a large role in land tenure and the success of the land registration process. Traditional common land requires first-time registration and a large amount of disputes have been reported (2011, p. 5).

Rahmato concluded, “The state uses its hegemonic authority over the land to dispossess smallholders and their communities without consulting them and without their consent” (2011, p.5). The problem lies in the political structure where the control of all resources belong to the state or the ruling party- who are ultimately responsible for land grabbing, but build a coalition through lo cal administrators and public agents who hold the authority to lease it- which serves to enhance the political advantage of the state (Rahmato, 2011, p.5). Peasants are threatened to only get access to land if they support local administers in the kebele and woreda where most rural people vote based on ethnic loyalties. Infringements on the right to a secret vote rarely lead to prosecutions. Smallholders lose trust in their local authorities that are complicit in investment decisions that lead to dispossession and their loss of livelihood.

The political hegemony of an ‘unfulfilled democracy’ (Pausewang et al., 2002, p.230) and ‘civic marginalization‘ (Rahmato, 2011, p.26) leaves little political voice for smallholders, chance to build a democracy though po litical competition, or shift power from bottom-up organizations without an independent material base (Pausewang et al., 2002, 239-242).36 As White

stated, “Like all agrarian struggles…in all regions of the world it is at the local level that organized social movements are relatively thin and weak” (2012, p.637). Furthermore, civil society institutions have little political voice since the dominant source of public information is government-controlled media (Rahmato, 2011, p. 7).

The progressive widening of the gulf between the social classes due to a high dependence on land resources will increase social and economic inequality (Rahmato, 2003). The haves and have-nots in the rural population will be in creasingly marginalized within the state’s redefinition of the agrarian struc ture (Rahmato, 2011, p.5, 25). While income inequality is low overall, the Gini coefficient rose from 29.8 to 33.6 indicating increased inequality from 2005- 201237 parallel with increased land grabbing. The increasing income divide confirms Harvey’s premise that the redistribution of capital from the masses to the rich is characteristic of neo-liberal policy and domestic actors benefit from neo-colonial processes of accumulation (2006, p.43).

Africa would stand to benefit from its abundant potential farmland and large potential for returns on productivity improvements from increasing global: population growth and demand for food, expanding urbanization, and rising incomes (Rahmato, 2011, p.5). The national Ethiopian strategy to capital ize on global market demand hopes to stimulate economic development by accelerating private sector commercial investment to switch from peasant cultivation to large-scale capitalist farming, increasing agricultural modern ization and increasing land for cultivation. But its neo-liberal structure favor ing foreign investors of large-scale land transactions that produce high value agricultural products such as flowers or vegetables (Rahmato, 2011, p.4-8)38 generates little benefit in the domestic economy. Rahmato concluded “Expe rience in other countries has shown that under proper regulation, domestic capital is more likely to act in ways that are socially responsible than its foreign counterpart (2011, p.27).

The goals laid out in the Plan for Accelerated and Sustainable Development to End Poverty (PASDEP)39 are advocated by the World Bank and adminis tered by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (MOARD).40 Regional governments facilitate dispossession through transfers of land into a federal consolidated land bank. According to Rahmato, there is no evidence that MOARD objectives are being met, the costs outweigh any benefits gained and governmental regulations are not structured to meet these goals (2011, p.13). The highest rent charged in 25-50 year leases is less than 135 Ethio pian Birr ($10.47 in 2009 dollars) per hectare per year (2011, p.15). Priority for exports and foreign earnings that preclude benefits to domestic markets are structured through tax exemptions that include: duty free input imports, repatriation of profits and dividends, principal and interest payments on external loans, proceeds from technology transfers, and asset sales in the

event of liquidation. There are no apparent formal provisions made to con tribute to domestic food security, domestic labor quotas, environmental pro tection, infrastructure, tech transfer, energy provision, or social investments (2011, p.25). The technology gap between high-tech capitalist farmers and peasants is so large; no achievable benefits to smallholders are affordable or transferrable (2011, p.25). The Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) claim that- leasing out land for bioethanol and biodiesel crops would not interfere with food production or jeopardize food security- is dubious (2011, p.10).

In both the historical case of England and recently in Africa, cooperative movements arose when the multitude lacking access to basic needs was likely to benefit by pooling resources to gain market power. The lack of trust in a government that could provide basic needs and politically pandered to the capital leverage of global markets left little alternative except collective action. Recently called out by the UN International Year of Cooperatives in 2012,42 cooperatives foster access to private competition, improve the rural economy, promote fair globalization and have the potential of merging eco nomic and social development goals with their “invaluable contribution to poverty reduction, employment generation and social integration” and their “strengths of the cooperative business model as an alternative means of do ing business and furthering socioeconomic development.”43

Historically, the cooperative movement in England, started in 1844 by the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers, enabled the multitude to gain ac cess to food and essential goods at affordable prices. Through collective action, a material base for political change was accumulated that effectually resisted44 the internal effects of industrialized globalization and the politi cal hegemony of the wealthy class. As a successful example of a consumer cooperative gaining competitive market power, while incorporating socioeconomically sustainable principles45 that equitably distributed returns and promoted participation, the number of cooperatives grew until the end of the 19th century when they consolidated.46

Recently, Ethiopian farming cooperatives have grown to a membership of over 4.5 million people47 with well-known success stories such as the Sidama and Yirgafcheffe cooperative coffee unions (Assefa, 2007). The ‘renaissance’48 of producer, marketing, savings and credit unions, and multi-purpose farmer cooperatives aid competitive market access, social integration and establish structures that can foster democracy and extend to provide educational ser vices. Marginalization of the landless, especially of vulnerable populations,49 has been mitigated through cooperatives, especially when including assign ment of group rights to common property to confront resource degradation (Tamrat, 2010).

While economic development in Ethiopia may be increasing per capita, pov erty reduction of the worse off in rural areas, national food security, land

degradation, migration and marginalization remain highly dependent on the secure tenure of productive land. Registering more common land rights to local villages and collectively governing productive inputs through CPRs would help to secure land tenure for shared use and returns instead of for corporations, public, or foreign capital; foster participation to strengthen democracy; and promote agricultural practices that are ecologically sustain able. Ostrom’s case studies showed that CPRs have been an enduring, ro bust form of organization with an inherent incentive structure favoring the implementation of practices that promote long-term over short-term gain (1990, p.3).

Combining cooperatives with CPRs would integrate socioeconomic develop ment with securing land tenure (Figure 1). An example of a combined model where rural common land was successfully registered for a cooperative vil lage with international support is the woreda Libokemkem for Buranest Ru ral Town, designated the Amhara Model Town in 2010.50 Agency support (capital) was matched by cooperative input (labor) in a participatory plan ning process that organized projects including: bridge and road infrastruc ture, flood control and rainwater harvesting, with housing, renewable energy, farmer education and other services in later phases.

Figure 1. Accumulation by dispossession processes within a sustainable development framework where the dimensions of economic, social and environmental development are addressed by a combined model of cooperatives and CPRs.

The similarity in both cases of the ‘relentless quest of capitalism to privatize everything through processes of accumulation by dispossession’51 is clearly differentiated by the historical-geographical conditions surrounding histori cal England and contemporary Ethiopia. While historically, the external forc es of globalization were manifest as internal class struggle, the contempo rary form of neo-liberal globalization through land grabbing is embedded in complex configurations of capitalist overaccumulation52 as a spatial fix from foreign territories and likely as in the case of China, the formation of foreign class power (Harvey, 2006).

Alternative politics to failed neo-liberalism form an impetus for a “resur gence of mass movements voicing egalitarian political demands and seeking economic justice, fair trade and greater economic security (Harvey, 2006, p.66).” Alternative planning depends on addressing alternative politics tak ing into account the complexity of urban systems that concentrate goods, services, distributional infrastructure and human capacities yielding syner gies. Planning is a natural platform that synthesizes and organizes the mul tiple forces forming our environment, cross cutting through the physical and social domain. Land as a factor of production needs to be considered as an input that couples the production of food and the production of space simultaneously although disciplines and professional expertise often split along lines of urban and agricultural development and can decompose them as isolated systems.

If the relentless neo-liberal drive for new resources (and capitalist class pow er formation according to Harvey, 2006) by foreign lands that externalizes the negative impacts of dispossession to home territories in Africa, were resisted then organizational efficacy depends on concerted international mo bilization and sustained multi-scalar struggle.53

If the long-term nature of implementing globally embedded transformation (e.g. global climate change initiatives), then practical action targeting midterm improvement is needed to mitigate the exacerbated direct and indirect impacts of land grabbing. The overarching goal remains to integrate eco nomic, social and environmental aspects into development to bring living conditions for the most vulnerable populations in African LDCs to a subsis tence level while improving their security and potential for livelihood.

Sustainable development in Ethiopia depends on engaging interdisciplinary planning that simultaneously addresses socio-economic and environmental development to generate basic needs such as food and livelihood, to secure land, to deter rural-urban migration, and to foster democracy. It depends on promoting transfer of land and resource rights to rural communities; building on the strengths of their existing social relations; developing organi zational capacity, knowledge and technology transfer, education and health services, complementary industrial capabilities, and environmentally sus tainable farming practices.

As regional market towns have an important part to play in the democratiza tion of Ethiopia, are one of the fastest-growing demographic sectors since the mid 1960s (Pausewang et al., 2002, p.64), and are local attractors of economic activity- they are logical sites to condense regional centralized services.54 Economies of scale and scope play a critical role in agricultural development to target rural development for surrounding farmers with im proved infrastructure to distribute supplies, health services and farmer edu cation (Mellor, 1966, p.345; Juma, 2011, p.114). Innovative projects and research have tested the potentials of urban resources but large-scale imple mentation remains a challenge (e.g. transforming solid urban waste (SUD) into fertilizer, Kiba, et.al., 2011). Synergies could form by focusing capacity building and endogenous development efforts on market towns while simul taneously securing tenure of surrounding farmland.

Further study is needed on combining CPRs with cooperatives or endogenous developments. More empirical data is needed measuring the correlation of foreign land grabbing in Africa and the magnitude of its impacts on: securing and registering land, common resources, food insecurity, land degradation, migration, income inequality, and the ability of agricultural cooperatives to secure common resources and implement sustainable agricultural practice.

If aid has the potential to transform the political economy then its efficacy depends on increasing the capital base of the poor. Supporting capacity building, political empowerment, and domestic markets (food aid reforms that foster local developing economies instead of subsidizing production surpluses from developed countries) depends on accountability to avoid fa voring the existing capital of elites and temptation for corruption.

Incentive structures based on matching capital investment by developmental aid agencies with securing collective land rights for indigenous communities (as in the Buranest example) could build robust resistance to neo-liberal national land policies if local organizations are supported by international efforts to retain and defend land rights. Intervening with organizational and capital support directly to local communities could initiate resistance to the dominant forms of neo-liberal accumulation empowering equitable distribu

tion and collective action. Overwriting the negative connotations of agricul tural cooperatives forced on the population in Derg regime’s process of ‘vil lagization’ could occur with more successful examples of a combined model.

Scalable capacity building based on the existing multi-level local, regional and federation organizational structure of cooperatives55 would use devel opment resources efficiently. With inherent checks and balances, returns directly flow to the poor. Economic security and food security could be lever aged through cooperatives to “recuperate human rights politics” (Harvey, 2006, p.57). Capacity building through endogenous development supported by joint efforts of international, public and private organizations would ben efit farmers and increase local knowledge capital56 but may miss opportu nities that build collective participation and self-help skills for farmers to sustainably organize land, water and food systems and secure land tenure.

If the production of space is to benefit the dispossessed and eventually check neo-liberal accumulation, the dialectic of space at the levels of absolute (fixed land use rights), relative (flows of capital investment), and relational space (socio-economic and political) needs to be considered simultaneously (Harvey, 2006, p.135). Combining multi-purpose cooperatives (agriculture, housing, credit and savings) with CPRs (water, land, forestry, fisheries) in a value chain would be more efficient and effective for communities, improve chances of extending social services57 (education, industrial transformation/ diversification), foster entrepreneurial business activity and resist political marginalization. Partnering with local organizations in Ethiopia would pro vide knowledge of operations at a local level and encourage participatory governance.

Class power formation, as the inevitable outcome of accumulation by dis possession and land grabbing, needs to be curbed at the global level by international mobilization while transferring land rights to communities to avert domestic capitalist accumulation at the local level. If Harvey’s asser tion holds true then the “mission of the neoliberal state to create a ‘good business climate’ that heralds capital accumulation as the only way to foster growth and eradicate poverty by seeking privatization of assets would de clare competition but open the market to centralized capital and monopoly power” (2006, p.25).

If the alternative politics of ‘reclaiming the commons movement’ is a re sponse to historical neo-colonial struggles (Harvey, 2006, p.64) then contem porary neo-liberal processes of land grabbing could follow a similar path. A combined model could avert capitalist privatization of land and environmen tal degradation if community use rights are secured. The model combines what Harvey calls alternatives and social movements: “local experiments with new production and consumption systems with different social relations

and ecological practices” (2006, p.64) and “pragmatic solutions to immediate problems of social or political exclusions or particular environmental degradations and injustices”(2006, p.111).

Acknowledgement of accumulation by dispossession in planning Acknowledging the ‘failed utopian project’ of neo-liberal accumulation by dis possession in Sub-Saharan Africa by planning means: understanding modes and channels of capitalist accumulation and focusing attention directly on tactics for local participation and secure tenure; engaging international de velopment organizations across sectors, who conversely engage planners, to focus investments from aid, capital and research into scalable, practical and synergistic planning alternatives that are structured to build the capacity of the rural poor; simultaneously addressing the interdependent economic, social and environmental aspects of sustainable development through terri torial relationships of land, food, capital, built and sociopolitical space; and recognizing the organizational complexity involved, sustained multi-scalar struggle necessary on all fronts, and influence of planning with its boundary of delimitation.

Author’s note: The time to prepare a portion of this research was generously granted by Prof. Dr. Marc Angélil, Chair for Architecture and Design, Institute of Urban Design, Network City Landscape, at the Department of Architecture, ETH Zürich. The cooperatives research was supported in part by an ETH North-South Centre Programme and Partnership Development Grant.

1 Debord, G. (1994). The Society of the Spectacle, trans. Donald Nicholson-Smith. New York: Zone p.121.

2 Figures from: http://www.ukpublicspending.co.uk

3 “With the dawn of the Tudor period began the general movement which gradually transformed England into a mercantile country. The amount of money in actual use was increasing; men possessed more capital, could borrow it more easily, and lay it out to greater advantage. Commerce permeated national life. Feudalism was dead or dying, and trade was climbing to its throne. The Middle Ages were passing into modern times.” (Ernle, 1936)

4 A longer period of accounting for the first and last Parliamentary Acts between 1604-1914 comprises 5265 Parliamentary Acts (Turner, 1980, p.32).

5 Figures from: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/ pdf/policy/WPP2011/Country_Profiles/Ethiopia_Demographic.pdf

6 Addis Ababa with 2.7 mil. of the population had a growth rate of 2.1% while agricultural regions such as Oromia with 27 mil. and SNNP with 15 mil. that are predominantly agricultural producers, had a higher growth rate than Addis Ababa of 2.9%. Amhara with 17 mil. had a growth rate of 1.7%. Population figures from Summary and Statistical Report of the 2007 (1994-2007) Population and Housing Census, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Population Census Commission Addis Ababa, 2008.

7 Figures from: http://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/notes/2009/N2868. pdf

8 In Medieval times, 12 acres were needed to produce enough corn to feed a family for a year. By 1800 the yield of corn had increased so that only 4 acres were needed to produce the same amount. Crop rotation was part of the sustainable agricultural practice that increased productivity with Spring planting, Fall planting and a field left fallow for regeneration of soil nutrients. A fourth replenishing fodder crop such as alfalfa or clover was added later that in turn provided rich manure for fertilization. Ja cobs attributed the population increase described by Malthus as being possible from increased soil fertility and livestock (Neeson, 1993, p.13; Jacobs, 1969, p.16-17).

9 About 80% of the costs were real investments on land improvement- fences, roads, and drainage. They were made cost effective through increases in rent, cost of capi tal, and real rent relative to wages (Clark, 1998, p.100).

10 In absolute terms, more land was arable by 1850 because much of the contribu tion was from converted waste (Allen, 1994, p.117).

11 See Ernle (1936) for Tudor enclosure that was mainly due to the growing wool trade that substituted pasture for tillage and sheep for corn.

12 Increasing population followed plague outbreaks, poor harvests in the 1590s and rising food prices that led to social unrest, and food and enclosure riots in 1598

(Slack, 1984, p.4). According to Slack in the 16th century, population increased faster than productivity and prices rose faster than wages so the purchasing power of labor dropped about 25% until around 1620. The previous impoverishment of farmers due to lack of secure tenure contributed to the growing poor population. The heavy migration of the large class of underemployed and working poor, made vagrancy visibly threatening. Under the reign of Elizabeth the underemployed poor and vagrant were accused of laziness and stigmatized. The Old Poor Law of 1601 aimed to promote social welfare by turning over administration of the poor from overburdened governments to church parishes.

13 Laws leading up the 1601 Poor Law include the 1547, 1551, 1563, 1572, 1576 and 1598 Tudor statutes that developed poor relief, taxation and outlawed begging and vagrancy for the able bodied (Slack, 1984, p.1; Snell, 1992, p.161).

14 The 1834 Act was seen to amend regulation of poor relief seen as the pauper supporting structure that subsidized low wages through the Speenhamland system.