urban design futures for singapore’s public housing

how it happens

urban design futures for singapore’s public housing

how it happens

Why does Singapore look the way it does? What policies have created the landmark spaces and buildings shown above?

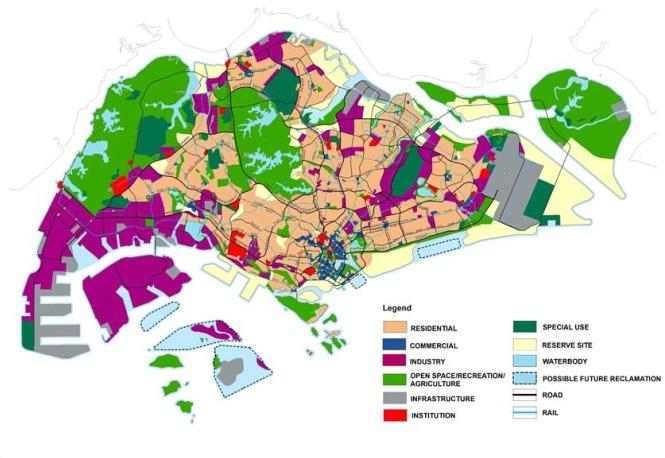

Since its independence in 1959, Singapore has pursued a policy of deliberate urbanization; with scarce land and lots of economic potential, urban planning is treated as essential to the city-state’s survival. After 19th Century growth in the center city became disorganized, the government largely adopted the stance that private land ownership was a barrier to coordination and national success.

With this ethos in mind, the Land Acquisition Act was passed in 1967, what “conferred powers on the state and its agencies to acquire land for any public purpose...,” essentially granting the government sweeping authority to control the built environment, with little regard for compensation to the property owner. From 1959-1984, the government acquired 43,700 acres of land, and, today, the public land ownership range hovers around 75-80%.

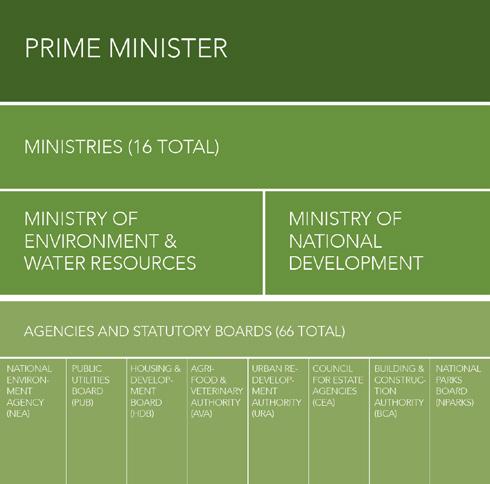

The agencies primarily in charge of national land use policy are in bold below, and described in detail on the next page.

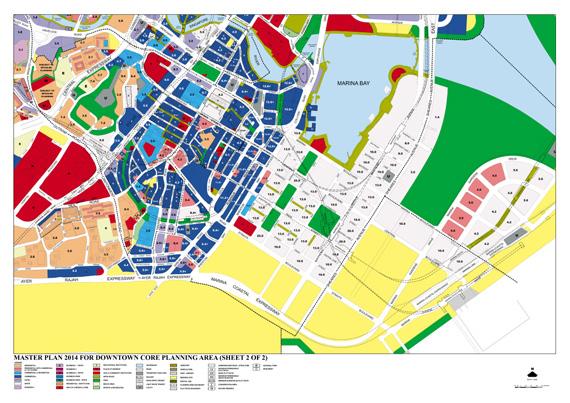

The URA is Singapore’s central planning authority. They coordinate development to optimize land use distribution and set national policy for what Singapore will look like. Overall, their focus is on creating the image of Singapore as a tropical city for the 21st century.

The three most important planning functions of the URA:

Develop the Concept Plan, the strategic land use and transportation plan that guides Singapore’s development for the proceeding 40-50 years. (Updated every 10 years).

Develop the Master Plan, translating the broad, long-term strategies of the Concept Plan into detailed land uses to be implemented over the next 10-15 years. (Updated every 5 years).

URA is also the primary government land sales agent, releasing properties for sale every 6 months to “meet demand and to achieve national development objectives.”

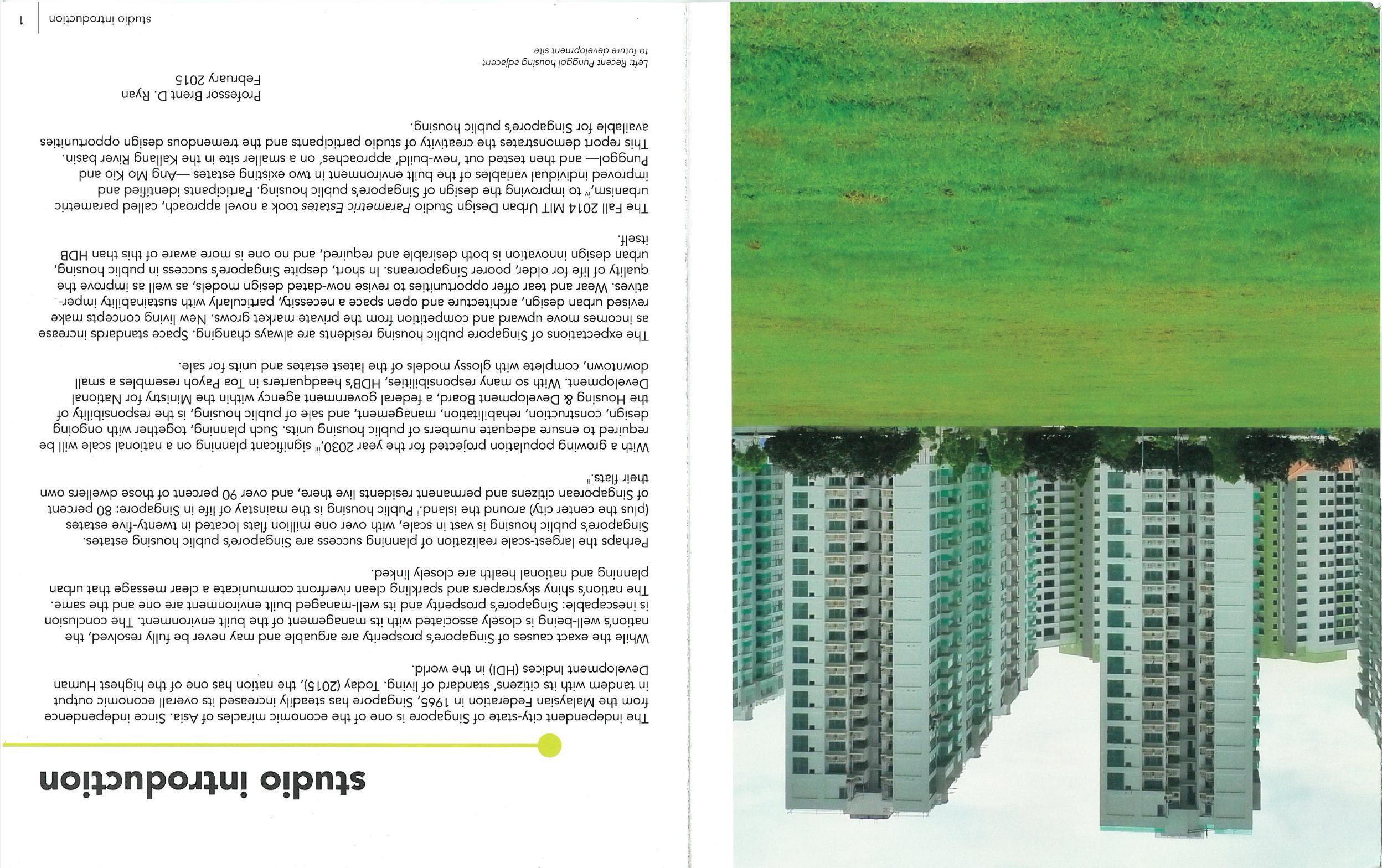

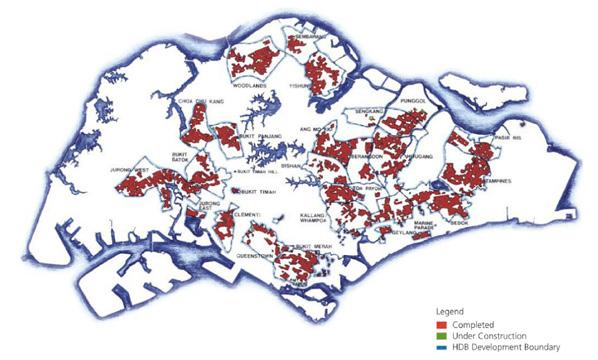

HDB is the sole agency responsible for public housing in Singapore, where about 80% of the population lives in governmentconstructed units. Since its founding in 1960, HDB has built over 1 million fats.

HDB takes a holistic approach to the housing question, overseeing everything from planning to landscape design to construction to property maintenance. The greatest focus of HDB is perhaps upgrading: improving existing housing stock and building new housing with the most up-to-date practices possible.

The city-state of Singapore is comprised of a main island of 697 km2 (270 miles2) and several smaller islands. It is located 137 km (85 miles) north of the equator, fanked to the north and south by the Singapore Strait and the Straits of Johor, respectively. Though its highest point, Bukit Timah mountain, stands 165 m tall (538 ft), the majority of Singapore’s land area is no more than 15 m (50 ft) above sea level.

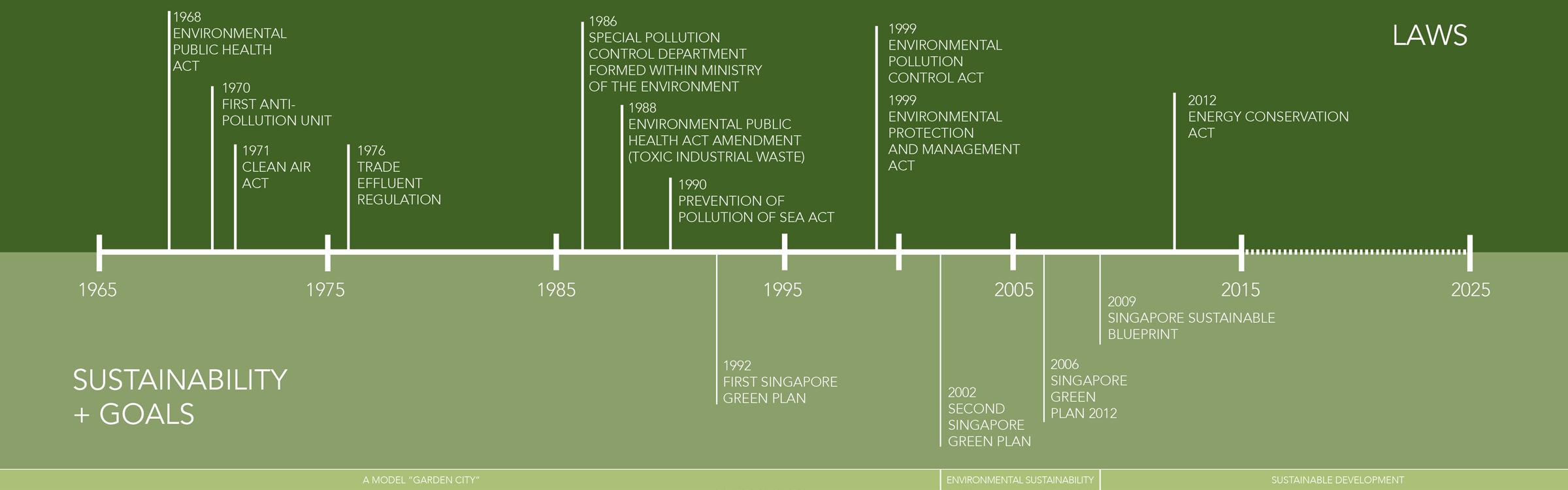

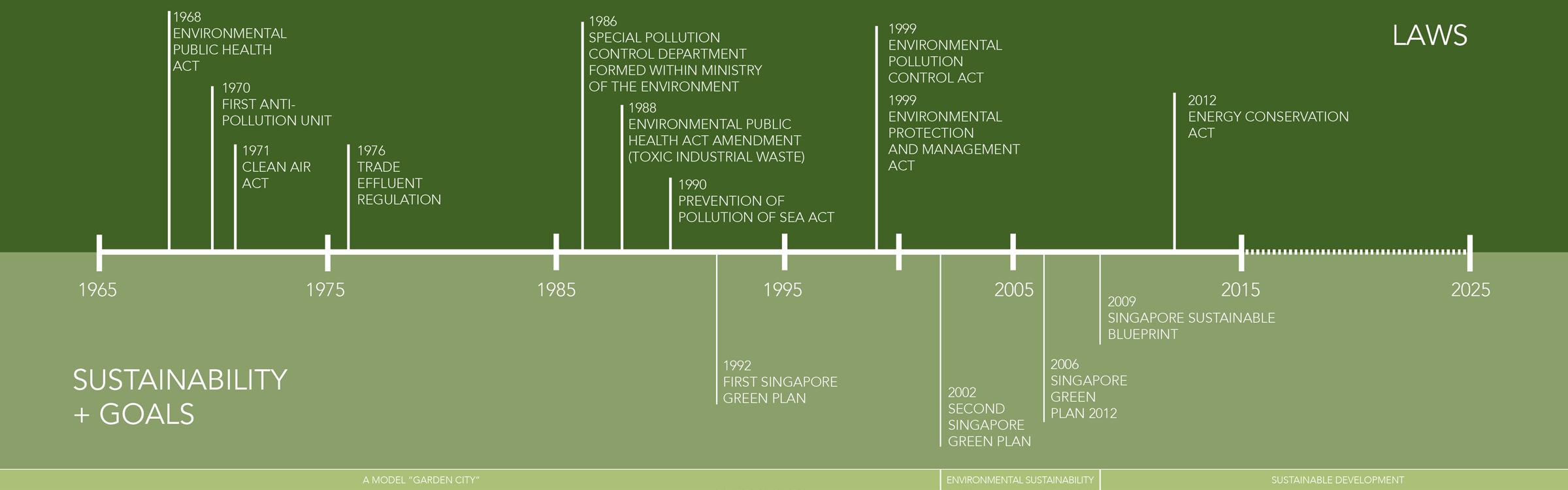

Careful management of fnite natural resources has been a policy concern since the early days of Singaporean independence from Britain in the 1960s. Only a few years after independence, Singapore implemented an environmental health act, quickly followed by anti-pollution and clean air acts. Over the decades, Singapore’s environmental laws have evolved from restrictions to aspirations, and the country has implemented a series of goals for sustainability, alongside its formal laws and regulations.

Singaporean national policy remains committed to preserving natural lands and resources “for as long as

possible,” though actual land use patterns and conservation efforts may vary according to the real estate value of potential development sites and other policy initiatives at the national level.

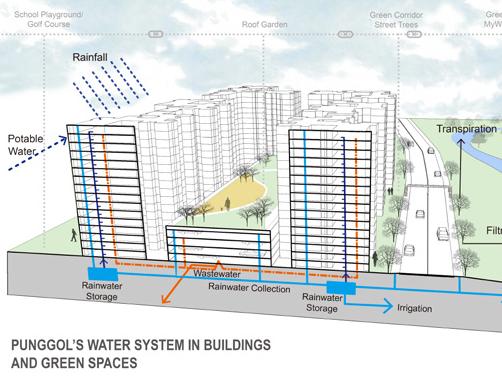

Despite Singapore’s tropical average annual rainfall of 2150 mm per year ( 85 inches per year), water access and water security are highly sensitive issues of domestic and national policy between Singapore and its neighboring nations, Malaysia and Indonesia. Technological solutions to increase Singapore’s domestic water supply such as rainwater capture, water treatment and recycling, and some desalination are viewed by the government as a form of national security.

Singapore’s national policies to address climate change and environmental degradation include public education campaigns about the science of climate change, waste reduction through differentiated recycling programs, energy effciency in buildings, and promoting public transportation. As with other areas of Singaporean policy, these measures are specifc, detailed, measurable, and to a large extent,

Sources: Singapore Ministry of Environment and Water Resources, National Environment Agency, Singapore Sustainable Blueprint (2013)

executed according to plan. Characteristic of Singapore, a wellorganized bureaucracy of policy designers and implementers carries out sustainability policy ideas at a variety of levels, with the aim to produce cutting-edge policy within their scope of infuence.

Internationally, Singapore is a signatory to important climate change and biodiversity agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol, though the Singaporean state generally does not take a strong political stance at these meetings. While internally there may be discussion of climate adaptation and mitigation efforts, these are not emphasized to the Singaporean public, likely because the potential implications of sea level rise, increased storm intensity, and unpredictable weather patterns would likely create uncertainty - a condition to be avoided for a country that bases much of its economy on creating a stable investment environment for shipping, fnancial, and other enterprises.

Singaporean environmental policy aims to apply cutting-edge policy goals and ideals within its sphere of infuence - that is, within its borders. However, due to the inherent regional impacts of climate change and environmental risks, further, and more robust, policy coordination efforts to mitigate and adapt to these challenges requires international and regional cooperation platforms, platforms in which Singapore has not yet been a key player.

Foreign Migrant Workers

Uneducated People

Low-skilled Singaporean Workers

Highly Educated

Strong Singaporean Identity/ Multi-ethnic

Married with multiple children

Naturalized Citizen

Speaks English Lives in Public Housing

Financially Stable and Invests money

Permanent Residents

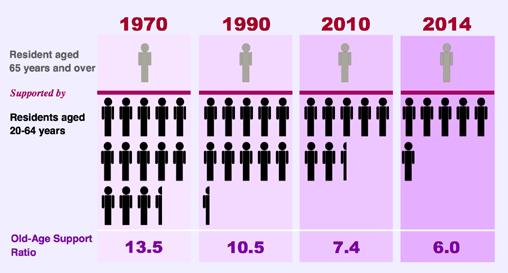

The perspicacious social policies instituted by the Singaporean government transformed the island city-state into a wealthy nation that provides its well-educated citizens with a high quality of life. At the commencement of the 21st century, the Singaporean government must once again confront signifcant challenges, including a low fertility rate and a ballooning elderly population, emigration, the need to recruit an ever-increasing number of permanent residents, and, most worrisome, an increased dependence on an expanding migrant worker population that remains isolated from the Singaporean citizen and permanent resident populations.

Sources:

Wealth Creation:

HDBInfoWEB, “Public Housing in Singapore”

Education:

Center on International Education Benchmarking, “Singapore Overview”

Singapore Ministry of Education

National Institute of Education, “The Development of Education in Singapore since Independence - A 40-year perspective “

Population Management:

Department of Statistics

Singapore, “Population”

Migrant Labor:

Asia Research Institute, “Migrant Labor in Southeast Asia, Case Study: Singapore”

Icons:

Stroller by Edward Boatman from The Noun Project

Piggy Bank by Thibault Geffroy from The Noun Project

Book by Ben Rex Furneaux from The Noun Project

Hard Hat by Jamie Rothwell from The Noun Project

Hard Hat by Jamie Rothwell from The Noun Project

Travel by Mister Pixel from The Noun Project

GLBTQ Communities

Homeless populations Single Adults

People in poverty

Non-English Speakers

The Singaporean government uses the HDB fat to create wealth for its citizens. Residents may let their whole fats or spare rooms. After a 5-year occupancy period, residents may sell their fats

$338,000 Median Sale Price for a 4-room Flat in Ang Mo Kio in 2009

-$30,000 First-time Buyer Grant

$308,000 Median Sale Price

$482,000 Median Resale Price for 4-room Flat in AMK in 2014

-$308,000 Median Sale Price

$174,000 Gross Proft

Integration through Planning

HDB Town

Malay:

Evolving Aims of the Education System

1978 - 1997: The government introduces streaming, aims to provide a high-quality education, and aims to retain students through secondary school

1997 - 2004: The government aims to increase students’ creativity and ability to innovate

2004 - The government replaces streaming with secondary school subject bands, and aims to expand students’ problem-solving capacity

By 2030, Singapore aims to increase its population to 6.5-6.9 million. This would require a resident population of 4.2-4.4 million, a citizen population of 3.6-3.8 million, a permanent resident population of 0.6 million, and a foreign worker population of 2.3 million.

BUT, in order to reach those numbers, there would need to be an increase in the number of non-residents entering the country each year

It is very diffcult to fle for compensation if injured on the job, or fle complaints about working conditions. Rampant violations of the Employment Act. Workers often work well over legal limits, sometimes up to 200 hours of overtime per month, and go many months without pay. Employers take illegal deductions from paychecks

renewing new towns for the 21st century

Singaporean children are subject to high societal expectations. To meet these expectations, children learn skills at home, at school, and out in the city. In Singapore, it is common for students, even young primary school students, to walk to school. The students’ walk to school is an important period of independence when the students are free to explore their environment. How could the built environment encourage students of all ages to explore? In addition, where within the city could spaces be

constructed for different types of exploration (e.g., contemplation or mental exploration versus physical exploration, solitary exploration versus group exploration)? This project proposes a palette of interventions distributed throughout Ang Mo Kio, according to the common paths that children take to and from school, to encourage children’s exploration.

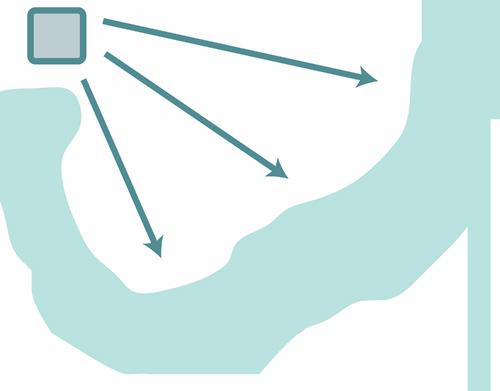

(Top Left) Children may proceed to school from one location (the MRT) or many locations (fats), and then proceed to many locations after school. (Top Right) Some paths are heavily traveled, others are not. (Middle Left) Not all paths offer children an opportunity to explore and exercise independence. (Bottom) This plan proposes interventions to enliven children’s paths and to give children agency.

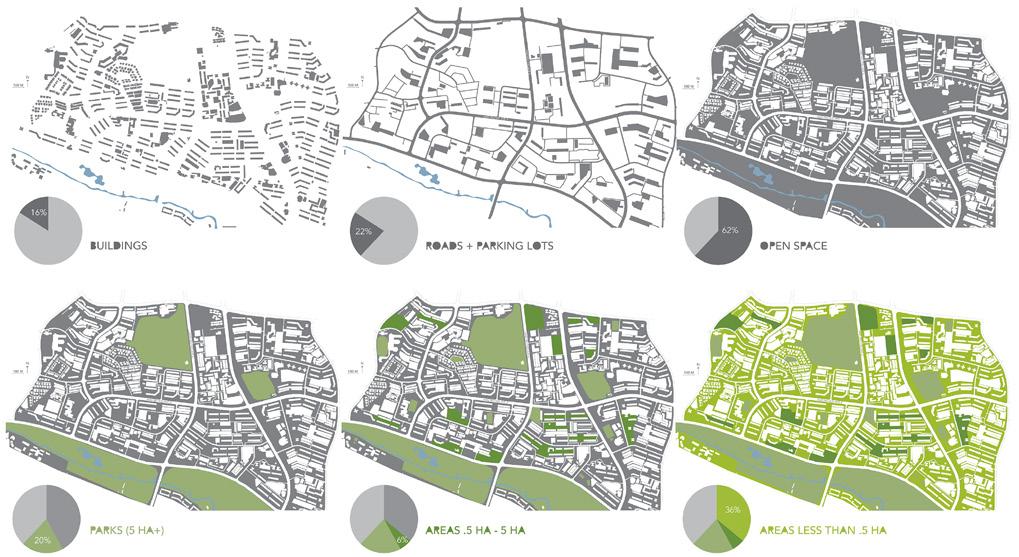

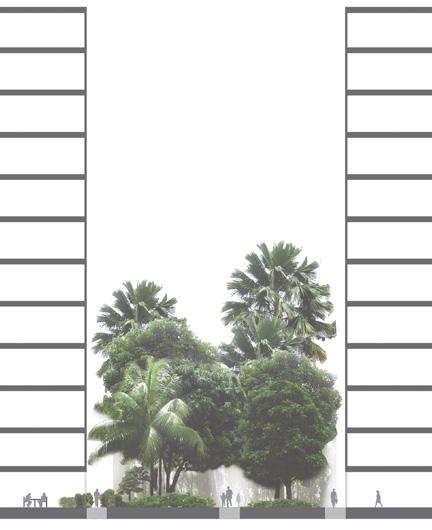

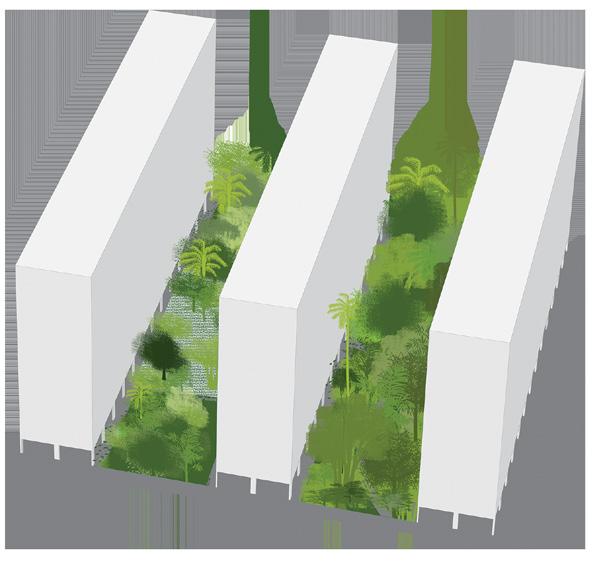

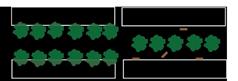

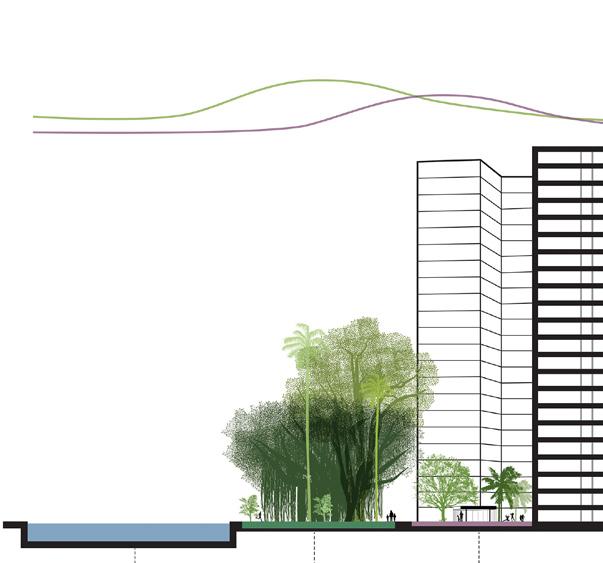

Singapore has a wet, tropical climate and prior to development was mostly lowland rainforest. This environment can support tremendous biodiversity with thousands of different species of plants. Today, however, much of the green spaces within the HDB estates contain a small number of different types of plants, most of which are not native, and a lot of grass. During analysis for this project, the open spaces in Ang Mo Kio were split into three different sizes. This project then focused on the smaller open spaces that were less than 5 hectares. Because the real species-area relationship increases signifcantly with just a small increase in area, this project looked at increasing the number of species in the open spaces within the housing developments in Ang Mo Kio, creating areas with greater biodiversity, and more evocative of Singapore’s original landscape.

Bukit Timah, one of the last areas of primary rainforest in Singapore, served as inspiration for this project. There is a signifcant difference in the number of species seen in Bukit Timah compared with Ang Mo Kio (opposite page, top, provides just a few examples of the fora and fauna found in each place). A section, axon, and perspective depicting potential lushness in open space between buildings with increased biodiversity are above and to the left. Below are the three different types of open spaces in Ang Mo Kio with their current and potential biodiversity. The real species-area relationship shows that there could be more biodiversity than what currently exists.

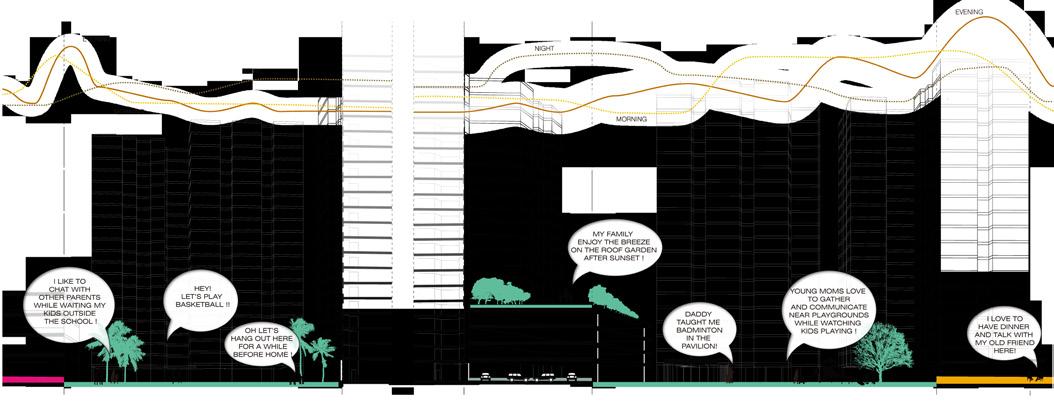

Happiness is a feeling, to be sure – something individual, something feeting, something that you can really only know about by asking someone how they are. But increasingly, happiness is being studied in economics and development policy – and increasingly in urban and architecture theory – as a means of overall life evaluation and, in this case, relating to the success of the built environment. My project aimed to increase happiness through the built environment in a public housing estate, what seemed especially relevant in as bland and as rigid a place as Ang Mo Kio.

We usually think of happiness as an emotion: DO

But if we start considering happiness as a LIFE EVALUATION we can better recognize deep-seated social problems.

Material but not emotional wealth.

“Singaporeans are the least likely in the world to report experiencing emotions of any kind on a daily basis.”

I developed six happiness metrics (left): meeting capacity as making purposeful and spontaneous interactions possible; green as diversifying and making logical open space; pedestrian emphasis as putting human mobility frst; scale as whether spaces are oriented to human understanding; wayfnding as the ability to navigate an environment; and color as increasing it.

This is a 1.5 x 1.5 km portion of AMK that I visited extensively. I coded this area for how many happiness criteria are present.

I looked at where people were going on a daily basis, to and from work, and came up with six specifc spaces in which to improve happiness.

Through my interventions, I wanted to break up the form in some way; all I kept seeing in Ang Mo Kio were rectangles and no texture to speak of. Moreover, I tried to give each space a defned purpose according to the goals of fostering personal agency and social connection, essentially to create spaces that the community could program and adapt, and to create identity.

Before, trees are linear and benches have no logical orientation towards other features. After, benches and greenery are arranged to create smaller outdoor ‘rooms’ where moveable furniture fosters private or public moments.

In addition to greening the walkways, the interior roofs would be interactive screens where, for example, local Instagram postings could appear.

TRACE : evidence of previous water.

FLOW : water moving at various speeds

SOUND: water interacts with surfaces producing sound.

SENSE: the experience of sensing water’s location without actually seeing it. (hardest to quantify)

25 m

Balcony Water Spirals (50 m3 water / day)

Water Walls (50 m3 water/day)

River Garden (24 m3 water/day)

Storm Drain Connection (74 m3 water/day)

Roof

Balcony Open Space Void Deck Parking Ocean

A. Waterfalls (SOUND)

block roof fow lateral bead helix

B. Balcony Spiral (FLOW)

C. Rain Garden (TRACE)

D. Piping System (SENSE)

50 m

In Singapore, water is everywhere. Due to the threat of mosquitos, foods, and general nuisance, water in public housing blocs tends to be hidden, minimized, and moved through the built environment as quickly and effciently as possible.

The poetics of water are often lost in efforts to manage water effciently in public space. This project highlights four poetics of water: TRACE - FLOWSOUND - and SENSE. Perhaps the most elusive of the four - SENSE - attempts to capture the experience of viscerally sensing proximity to water without actually seeing it.

(Left) 3 sites of water design intervention:

1. Balcony (leaking)

2. Open Space (underutilized)

3. Void Decks (fooded)

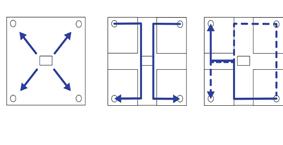

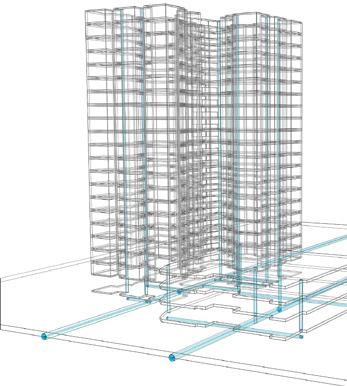

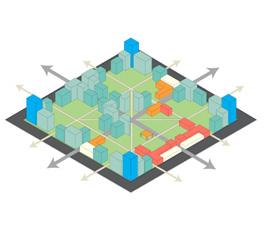

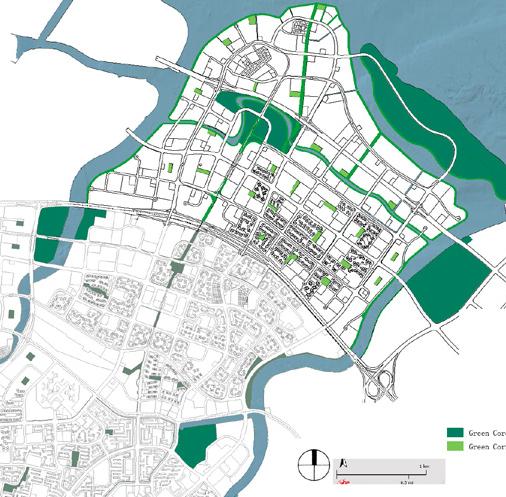

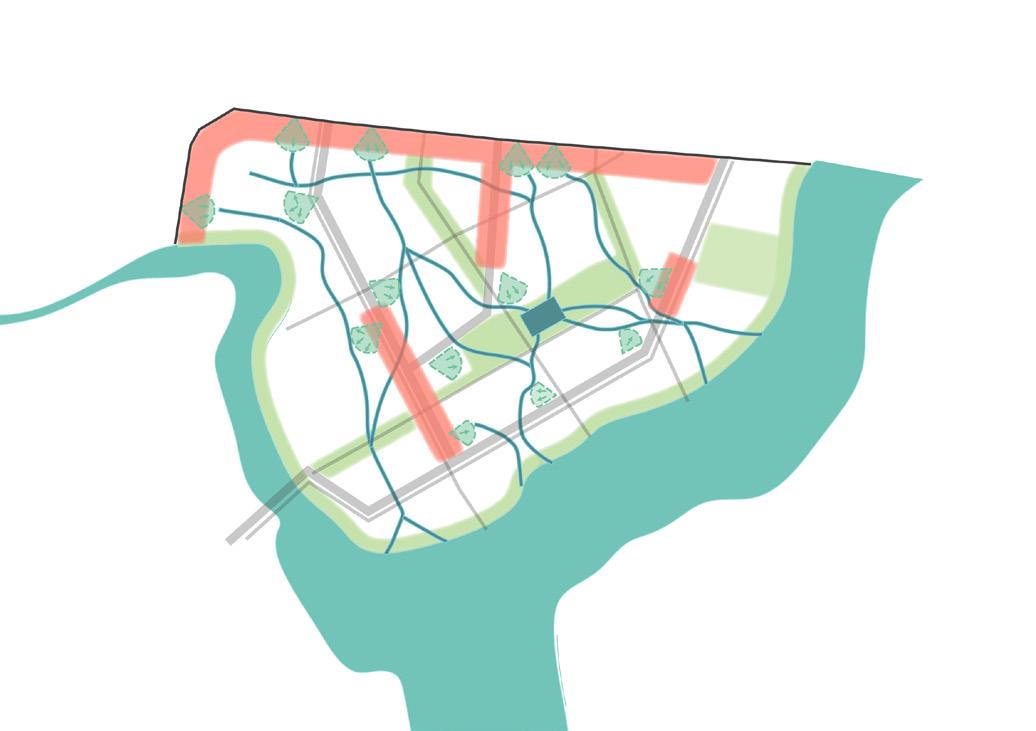

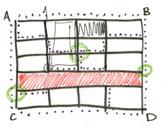

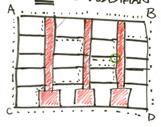

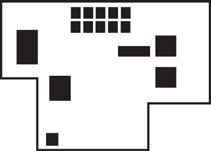

My initial analysis at Punggol examined the relationship between parking and open space, and its impact on the ease of movement through each housing block. This analysis connected to issues of wayfnding, which is major problem throughout Punggol due to the monotony of building heights and similarity of designs. I proposed a series of ideal development forms that addressed both access and wayfnding by using parameters at the block scale (such as higher densities located at major arterial intersections; schools and commercial uses located at minor access road intersections, etc.).

I then applied these idealized forms to the Punggol site itself, where new housing blocks were to be developed. At this larger scale, I created additional wayfnding parameters, such as locating higher densities and commercial uses towards the public transit line, and lower densities and increased open space towards the water. Through these design solutions, Punggol residents and visitors will be able to traverse the site at grade through landscaped open space, orienting themselves towards major landmarks.

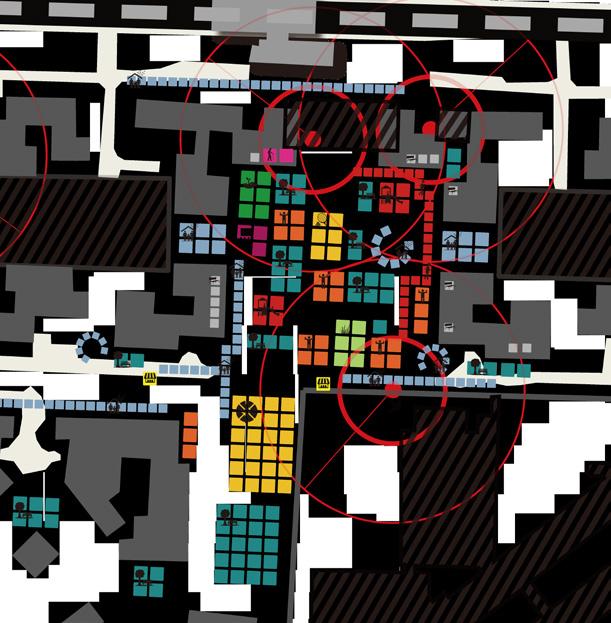

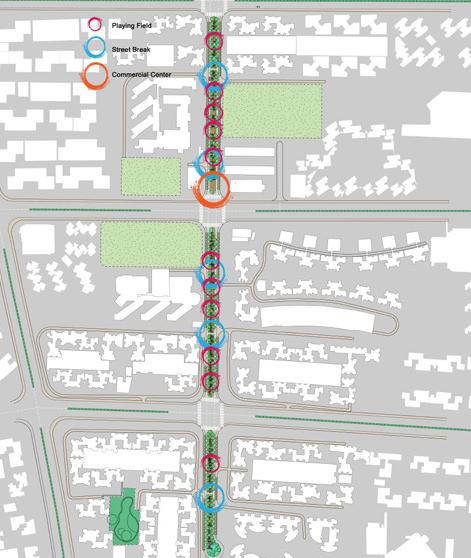

The entry point of my thought was the phenomenon that some open spaces were flled with social activities while others were dead. I found that most of the former ones were activated by community amenities like schools and commercial center. Then I examined the relationship between amenities and activity from a multi-scalar perspective.

At the whole-site scale, I proposed a new organization of land uses in as-yet-unbuilt areas of Punggol, in order to correct what I saw as inappropriate or ineffcient organizations in the already built areas. At a smaller scale, I also proposed to reorganize and augment community facilities in the open spaces of existing Punggol community spaces in order to provide more amenities to residents and to provide a better relationship and functioning of activities like shops and schools.

As we know, Singapore is an island country and a ‘garden city.’ Despite this title, there are only two prevalent types of green space: the large city park and the small residential green land. This limited range of green typologies prevents people from fully exploring Singapore’s biodiversity, and limits the activities of animals and potential water storage capacity. For example, some residents in Punggol have to walk more than 2,500 meters to My Waterway, a large regional park. High density building areas and wide roads – both unfriendly to the pedestrian – are two barriers blocking direct access to this park.

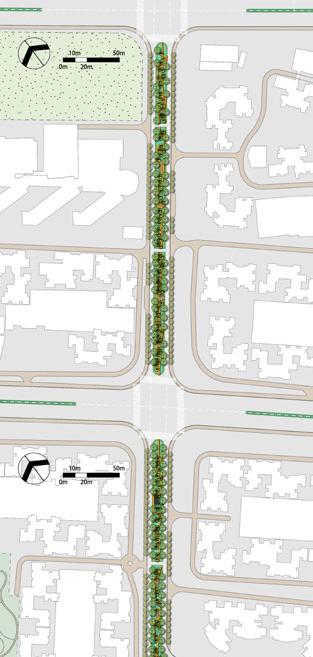

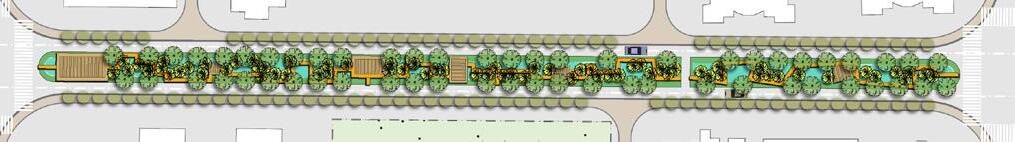

For my project, I added green space along a road median in order to improve on an existing series of green connections. By updating the current road system, I tried to link the small green lands between the residential buildings to My Waterway. I designed boulevard streets as more effcient green corridors.

I also created three different spaces of activity for pedestrians in order to improve their experience and increase their accessibility to My Waterway. Beneath that pedestrian path, a water collection system was designed to guide water fow towards areas of natural catchments.

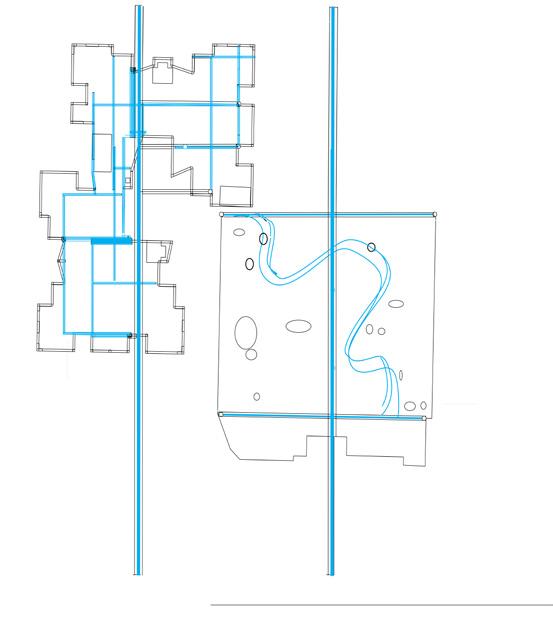

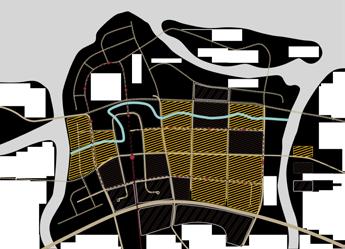

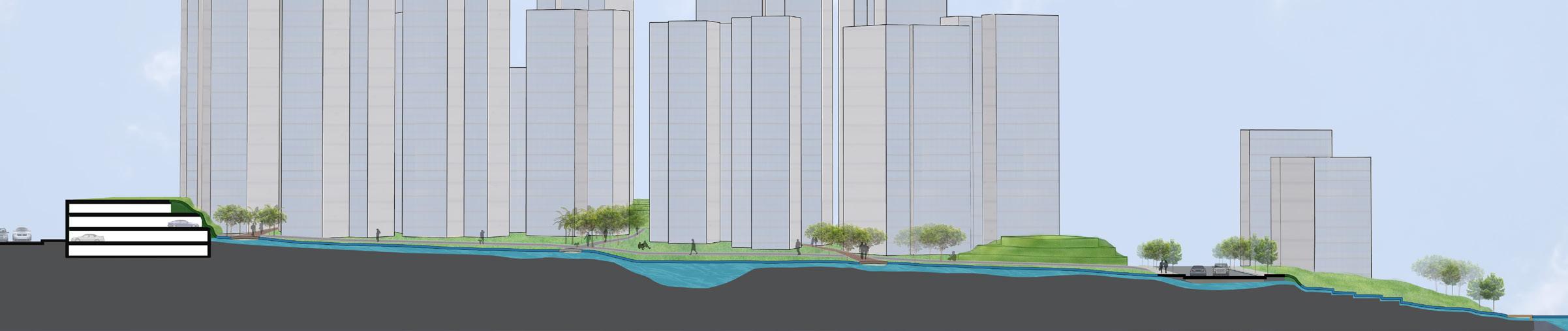

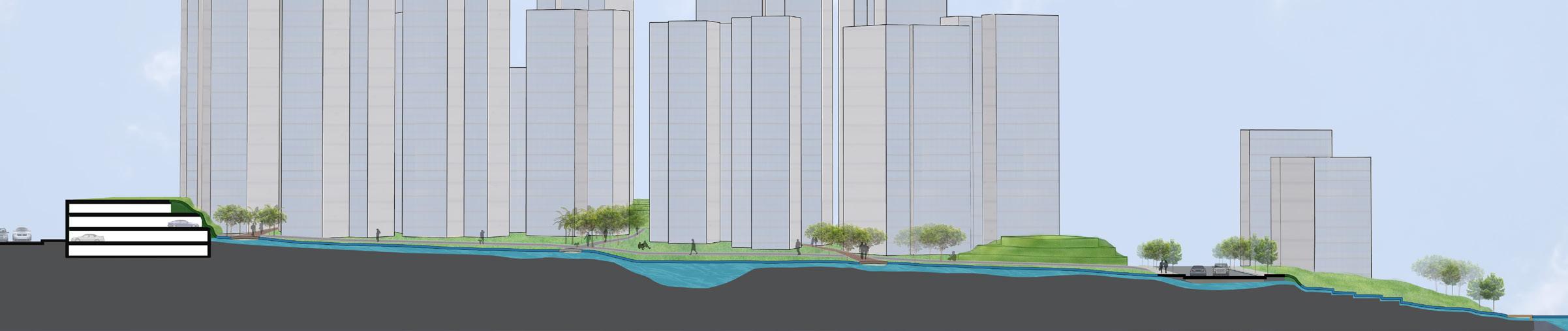

a parametric estate in central singapore

Water is the guiding principle for the design of paths, public open space, parking, and roads. Water fow patterns found in nature (‘converge,’ ‘pond,’ ‘meander,’ etc.) make up a simplifed watershed on site, designed to move water away from the former Kallang Gasworks (on the northwest corner of the site) to the Kallang River to the southwest. The clear directional fow of each water path provides for more effective wayfnding, a more walkable series of paths, and direct pedestrian access to the river through the site.

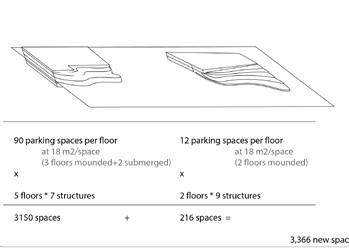

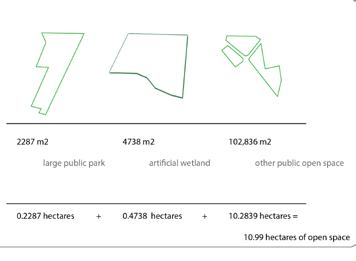

Parking is submerged in mounded topographical features that aid in site drainage, channel water through public open space, and buffer cars and car-related activity from the pedestrian experience while keeping parking accessible to nearby homes. Parking topography complements - but does not replace - ample public park space on site.

Each building and open space is a source of water: Singapore’s frequent rain showers create site conditions that alternate frequently between wet and dry. A mix of permanent streams and rain gardens provide a visually appealing and naturalized form of storm water management on the site.

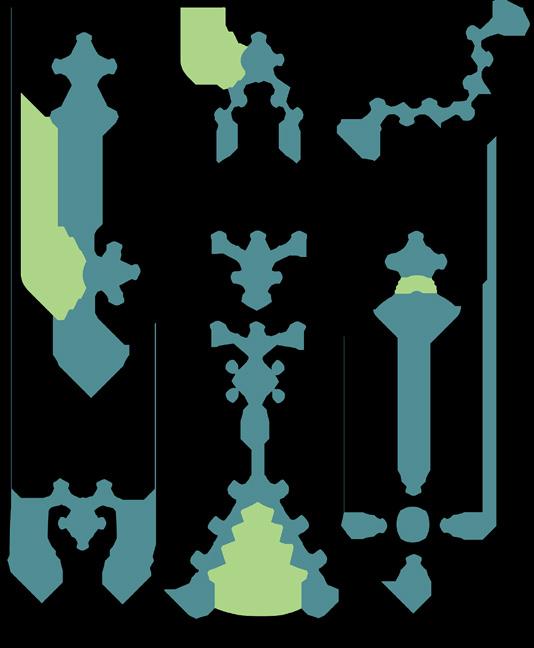

We identifed 9 main ways water moves in nature, employing each as an experiential and environmental component on the Kallang site.

The main goal for the site is to move water away from the former gasworks, through various levels of bioremediation before reaching the main waterway

Using the abstracted water movement rules we identifed earlier, we connected them to create multiple streams throughout the site

water (blue), vehicular (black), and people (green) fows

PARKING along major road adjacent to water mounded to aid in water fow

land use: commercial (red), residential (yellow), parking (gray), open space (green), institutional (purple), beige (existing temple)

OPEN SPACE along pedestrian paths fat for recreational use

WETLANDS opposite corner from former gasworks additional layer of bioremediation

COMMERCIAL along major road near parking

WATERFRONT natural waterfront landscaping path along the waterfront

CENTRAL WATER FEATURE at intersection of water paths surrounded by green space and topography

Sample path that connects the Kallang River to Kallang Road. Pedestrians have different experiences where the path intersects with water features, commercial uses, and open space.

The images at right show examples of experiential moments in which a pedestrian path intersects with different types of water and open space

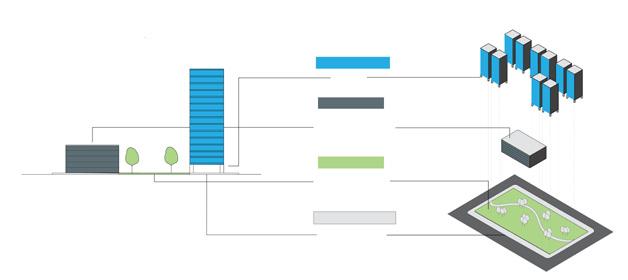

The driving force behind this project is the relationship among larger amenities, smaller amenities, and different types of open spaces. The aim is to create a place rich in both amenities and different fora and fauna. There are three main types of open spaces, ranging from mostly green, vegetated spaces, to activity-flled centers. Together, the amenities and open spaces create hubs of recreation and nature for residents and visitors.

The green strip cutting through the site is a lush, almost jungle-like experience, with civic institutions running along its northern edge. The corridor also serves to bring people from the main road through the site to the water. The greenery along the river is reserved to create an esplanade that provides ecological connectivity throughout the site.

The northern edge of the site is comprised of commercial and mixed use buildings. Residential towers throughout the site provide thousands of housing units. Each residential cluster enjoys a green courtyard with vegetation in the center and recreational, educational, or commercial amenities activating the edges.

Maximum biodiversity

Some biodiversity, some activity

Maximum activity

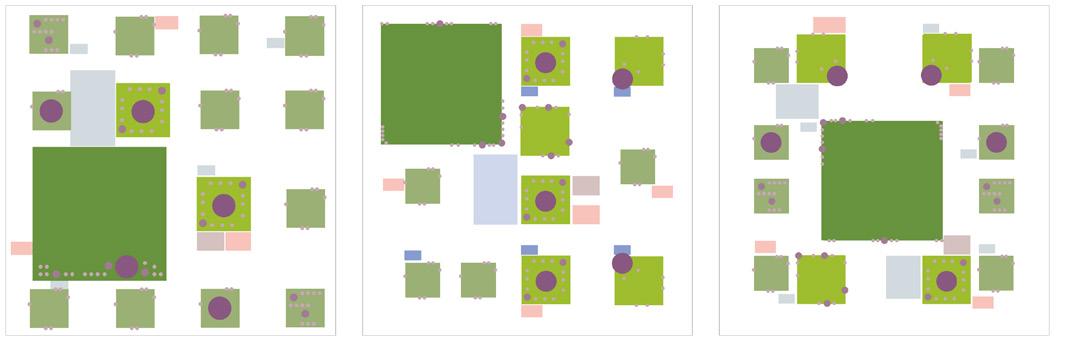

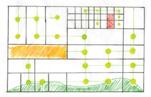

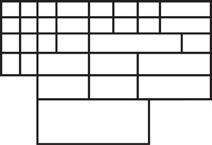

Three variations of amenity (left) and green space (right) compositions on 18 ha. Amenities: schools (blue), community center (purple), open space (green), commercial (red). Green spaces: Small squares are .25 ha, medium squares are .5 ha, largest square is 3 ha. Three variations of compositions of green space and larger and smaller amenities on 18 ha with 7 ha of green space (below).

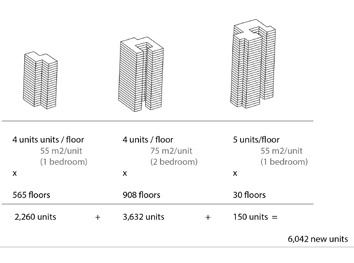

6,285 residential units

3,225 parking spaces

magnitude of biodiversity

magnitude of activities

Our plan for Kallang prizes peoples’ experience in this place. With that guiding principle, we attempted to correct the spatial and programmatic shortcomings of existing HDB estates, while employing the elements of high density residential development and abundant green spaces that work well in Singapore’s existing built environment. In service of improving practices in existing estates, we:

1. Programmed for mixed uses, and varied block and building sizes;

2. Referred back to an older and smaller scale kampong commercial typology that activates the major street edge;

3. Placed the school in a large park to allow for children’s play and exploration;

4. Built along a central axis the culminates in landmark spaces in order to emphasize the site’s natural amenities - the river and its mature trees; and

5. Created the highest density in the center of the site in order to protect ecologically sensitive areas along the river and to ensure that many apartments have visual access to downtown Singapore.

paths exploration independence

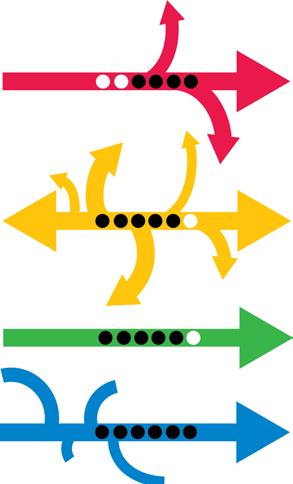

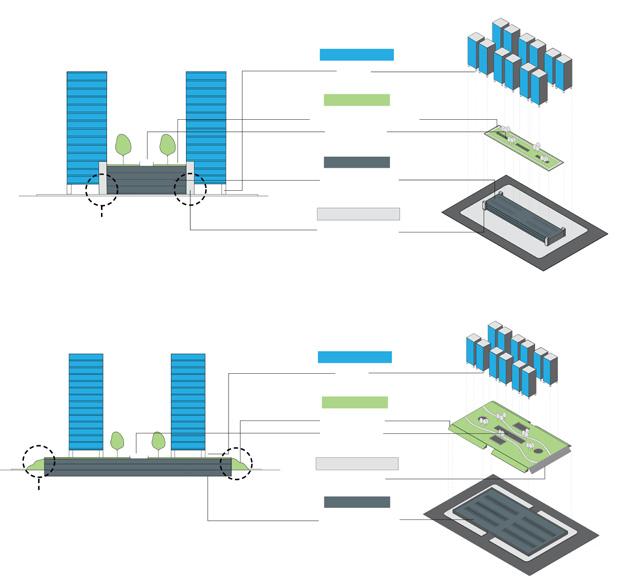

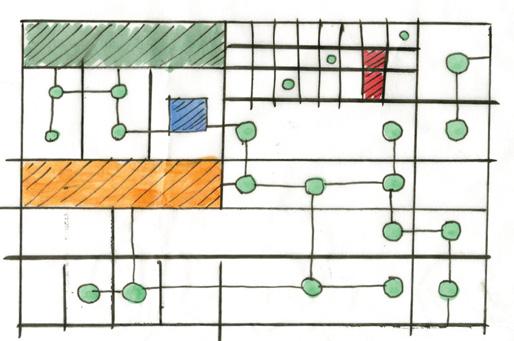

Through abstraction, we visualized the themes underpinning our individual midterm projects.

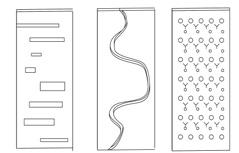

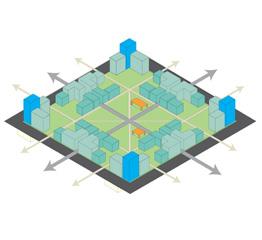

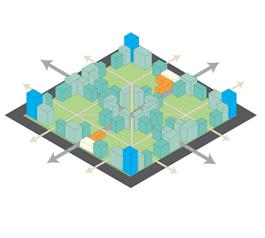

In the frst set of diagrams, we abstracted our individual ideas: the contribution of the built environment to personal happiness, with an emphasis on creating variety of experience through block type, building heights, and building footprints; children’s exploration of the built environment through different confgurations between neighborhood school, residential buildings, and open space; and the connection of ecological resources through different interactions between water and green space.

In the second set of diagrams, we tried to determine the optimal spatial intersections between two themes at a time (e.g., happiness and ecology, children and happiness, or ecology and children).

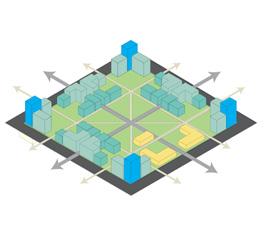

The fnal diagram represents the optimal spatial confguration of our three original ideas, and is the basis for our proceeding design. This scheme stresses: a distributed green network; a diversity of meeting places; a variety of built form and environmental scale; and clustering of a school, green space, and other amenities.

human scale

variety of experience

mastery of environment

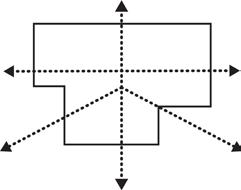

After developing our initial abstract diagrams, we examined the site and its context for their character and inherent advantages. We determined that their distinguishing features were: connection to the water; a very dense, adjacent built fabric; clear views to downtown Singapore; and mature greenery.

Combining our abstractions and contextual knowledge, we developed fve principles on which to build (at left). Then, with our ideal spatial composition and principles in mind, we moved to the site and envisioned three community structures with varying emphases (at right).

5 massing

VARIETY

CONNECTION

HIERARCHY of ECOLOGY + AMENITIES

• Green corridors lead to landmark open spaces;

• The park (at upper left) is a gateway and a shared resource;

• The school is located within this park and near the water to give children access to nature, and to create an illusion of seclusion while maintaining access to nearby amenities;

• Block size varies signifcantly (with smaller blocks closer to the main road) and, in addition to multi-use roads, pedestrian paths (in yellow) weave throughout the development. Both of these elements are intended to provide people with variability in their experience of the built environment;

• Increase biodiversity and flter runoff from the site before it enters the river.

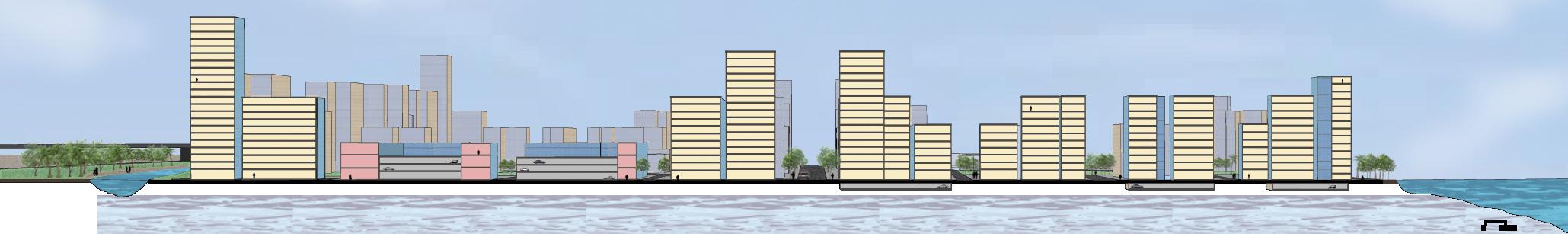

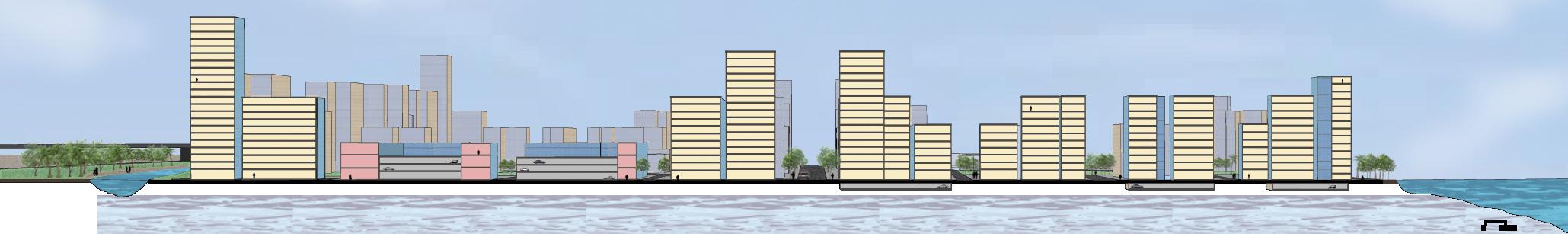

The axon (above) and elevations (below) best demonstrate our massing profle: the densest buildings are sited along the boulevard (right) to create a strong center and sense of place. In a gradient moving outward from this center, building height and footprints are reduced to preserve views of the water and to limit the density of people at the water’s edge.

Massing and block size create a commercial street along the main exterior road that references small-scale, edge commercial development found in the historic part of downtown Singapore.

The perspective (right) is an illustration of the kind of exploratory and unfettered play we hope to encourage in our new Kallang. A central component of our original scheme was siting the school in a park, to ensure that children were immersed in nature on their walks home everyday.

The axons (below) represent the variety of experiences an average, working age Singaporean can have on our site. For example, on a Saturday, a resident might start off at home, run some errands along the small scale commercial street, stop in to a larger scale commercial building for some lunch, sit out on the adjacent plaza and enjoy the river views, stop by the health clinic in a mixed use building along the green boulevard, and then return home.

MONDAY neighborhood paths to work

THURSDAY calm walk at day’s end

SATURDAY errands + views

OPPOSITE PAGE 1

“Punggol” by S. Menozzi.

PAGE 4-5

“The Pinnacle,” HDB, Architecture Lab. “Southern Ridges,” No Author, Inhabitat. “One North,” Aedas, Just Interior Ideas. “Marina Bay Sands,” No Author, Thai Good View. “Master Plan,” URA. “Concept Plan,” URA. “HDB Estates,” HDB.

ICONS

“Real Estate,” Luis Prado, Noun Project. “Blue Print,” Dimitry Sunseifer, Noun Project. “Light Bulb,” Roy Verhaag, Noun Project.

PAGE 8

“Children,” The Cadbury Chocolatier. “Old Singapore,” Janaki Kibe, AHI Global. “Fertility Rate,” Department of Statistics Singapore. “Migrants,” Shibani Mahtani, Wall Street Journal.

ICONS

“Stroller,” Edward Boatman, Noun Project. “Piggy Bank,” Thibault Geffroy, Noun Project. “Book,” Ben Rex Furneaux, Noun Project. “Hard Hat,” Jamie Rothwell, Noun Project. “Hard Hat,” Jamie Rothwell, Noun Project. “Travel,” Mister Pixel, Noun Project.

PAGE 12

Ang Mo Kio photo by S. Menozzi. Punggol photo by Z. Lamb.

PAGE 15

All photos by S. Menozzi.

ICONS

“Train,” Jens Tärning, Noun Project. “Bus,” Pierre-Luc Auclair, Noun Project. “City,” Cris Dobbins, Noun Project.

PAGE 16

“Cyrtostachys Renda,” Danielrengelm, Wikimedia Commons. “Samanea Saman,” Mokkie, Wikimedia Commons. “Columba Livia,” J.M.Garg, Wikimedia Commons.

“Ficus Microcarpa,” Forest & Kim Starr, Wikimedia Commons .

“Koompassia excelsa,” Dick Culbert, Wikimedia Commons.

“Mangosteen,” asano, Wikimedia Commons.

“Oncosperma Horridum,” Ahmad Fuad Morad, Flickr.

“Blue-Crowned Hanging Parrot,” Lip Kee Yap, Wikimedia Commons.

“Sunda Slow Loris,” David Haring / Duke Lemur Center, Wikimedia Commons.

PAGE 17

All photos by C. Schaefer.

PAGE 18 - 19

“Hallway,” John Wah, Flickr.

“Void Deck,” Horst Kiechle, Flickr.

“Covered Walkway,” Horst Kiechle, Flickr.

ICONS

“Metro,” Jens Tärning, Noun Project.

“Home,” Desbenoit, Noun Project.

“Meeting Capacity,” Cris Dobbins, Noun Project.

“Green,” Ilias Ismanalijev, Noun Project.

“Pedestrian,” S. Shohei, Noun Project.

“Scale,” Edward Boatman, Noun Project.

“Way fnding,” Garrett Knoll, Noun Project.

“Color,” Björn Andersson, Noun Project.

PAGE 20

4x3 Water Matrix : (From Top Left)

San Diego CA - Tide Pools Getty Images.

North Antelope Canyon Navajo/AZ, Bing.com/images.

Vernag Bagh India, MIT Library Images - Architectural Design.

Nishat Bagh India, MIT Library Images - Architectural Design.

Aachen Germany, Bing.com/images.

Portland OR - Halprin, api.ning.com.

A’Samaliah Island UAE, MIT Library Images - Architectural Design.

El Alhambra Spain, MIT Library Images - Architectural Design.

Pulai Springs Resort Johor Baharu Malaysia, MIT Library Images - Architectural Design.

Fort Worth TX - Johnson and Burgee, Flickr.

Ville le Lac Corseaux Switzerland - Le Corbusier, hicarquitectura.com.

Namakdan Pavilion Afghanistan MIT Library Images - Architectural Design.

Existing Singapore Triads: A. Fonda-Bonardi (all).

PAGE 20-21

Existing Water Structure:

Tank photo, imageshack.us.

Roof photo, interlinkpower.com.sg.

All other photos: A. Fonda-Bonardi.

PAGE 25

Photos by M. Ren.

PAGE 30

Photos by C. Schaefer.

PAGE 32

Top Left: “Rainwater Harvest,” Power House Growers.

Top Middle: “Water Channel,” Dan Sellars, Dare.

Top Right: “Rock in Pond,” Bok Fu Do.

Bottom Left: “Traditional Japanese Garden,” 123RF.

Bottom Middle: “Seahouse Sands,” Seahouses Website.

Bottom Right: “The Water Garden,” Water Garden.

PAGE 42-43

Farthest right: “Shopping Street Singapore” by Linus Kallman, There Will be Asia Blog.

All other photos by M. Ren and C. Schaefer.

PAGE 45

ICONS

“Happiness,” Mark Shorter, Noun Project. “Ecology,” birdie brain, Noun Project. “Children,” OCHA Visual Information Unit, Noun Project.

PAGE 49

Base for Perspective: “Forest,” Jimmy Tan, Jimmy Photo Gallery.

ICONS

“Metro,” Jens Tärning, Noun Project. “Home,” Ava Rowell, Noun Project.

PAGE 52

“Group,” Lorena Gomez, obtained from author.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

for brent to fll out if he desires

BRENT D. RYAN

ZACHARY B. LAMB

ALLEGRA FONDA-BONARDI

Hometown: Santa Monica, California

DUSP Group: EPP

Previous Degree: Environmental Studies (BA), Oberlin College

LILLIAN JACOBSON

Hometown: Berkeley, California

DUSP Group: CDD

Previous Degree: American Studies (BA), UC Berkeley

SUNNY MENOZZI

Hometown: Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

DUSP Group: CDD

Previous Degree: Political Science (BS), United States Military Academy at West Point

MENG REN

Hometown: Beijing, China

DUSP Group: CDD

Previous Degree: Architecture (MS), Tshinghua University

CHLOE SCHAEFER

Hometown: Salt Lake City, Utah

DUSP Group: EPP

Previous Degree: International Relations (BA), Pomona College

ALEXANDRA SUTHERLAND-BROWN

Hometown: Ottawa, Canada

DUSP Group: CDD

Previous Degree: American Studies (BA), Princeton University

FEI XU

Hometown: Beijing, China

DUSP Group: CDD

Previous Degree: Landscape Architecture (MS), Peking University