FINAL REPORT:

Sustaining Hāna: Nurturing Cultural Heritage and Environmental Stewardship through Indigenous Environmental Planning

Indigenous Environmental Planning | Spring 2024

Architectural

Sustaining Hāna: Nurturing Cultural Heritage and Environmental Stewardship through Indigenous Environmental Planning

Indigenous Environmental Planning | Spring 2024

Architectural

The final report on the Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike project presents a comprehensive overview of the challenges and proposed solutions for sustainable tourism and community empowerment in Hāna, Maui. Led by a diverse team from MIT and Harvard Graduate School of Design, in collaboration with Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike, the report outlines a holistic approach rooted in indigenous environmental planning principles and local community engagement.

INTRODUCTION:

The report begins by introducing the ahupua’a model, a traditional Hawaiian framework for land division that emphasizes interconnectedness and sustainability. Hāna, situated within an ahupua’a on the eastern coast of Maui, faces challenges such as poverty, economic disparities, and environmental degradation despite its rich cultural heritage and natural beauty.

CHALLENGE:

The influx of tourism, driven by the completion of the Hāna Highway in 1926 and subsequent developments, poses both opportunities and threats to the community. The report highlights the impacts of tourism on Hāna, including environmental degradation, commercialization, and socio-economic disparities. It emphasizes the need for sustainable tourism practices that respect the cultural and environmental values of the local community.

The report outlines three key deliverables to address the challenges faced by Hāna:

Mahele Farm Report:

A comprehensive analysis of the Mahele farm, a community initiative addressing food insecurity and promoting sustainable living through traditional ecological knowledge. The report highlights the integration of indigenous practices with sustainable tourism, fostering a deeper connection between tourists and the local environment.

Mapping Toolbox:

A participatory mapping toolkit designed to empower the community to preserve and share their cultural heritage while promoting sustainable tourism practices. The toolbox enables the annotation of important cultural and historical sites, fostering community engagement and environmental stewardship.

Architectural Layout:

A sustainable tiny-home design tailored to Hāna’s climate and cultural context, aimed at providing affordable housing solutions and supporting youth empowerment programs. The design incorporates elements of sustainability, accessibility, and cultural relevance, reflecting the community’s values and aspirations.

In conclusion, the report emphasizes the importance of community-driven initiatives in promoting sustainable tourism and empowering local residents. By integrating indigenous knowledge with modern planning principles, the project aims to support Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike in their mission of fostering resilience, preserving cultural heritage, and promoting environmental stewardship in Hāna, Maui.

Khadija Ghanizada

Master of City Planning Candidate

MIT | 2025

Leylâ Uysal

Master of Design Studies Candidate

Harvard GSD | 2024

Nina Lytton

Interfaith Chaplain & Spiritual Advisor to the Indigenous Community at MIT

Clarise Han Bachelors of Computer Science

MIT | 2025

Leslie Ponce-Diaz

Master of Architecture II Candidate

Harvard GSD | 2025

Lipoa Kahaleuahi

Executive Director of Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike

Ahupua‘a

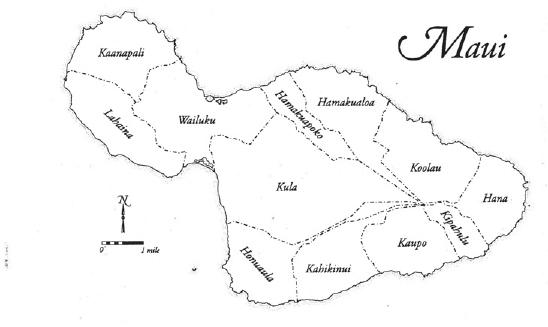

First, we would like to introduce ahupua‘a, a Hawaiian model for indigenous environmental planning. Ahupuaʻa are land divisions that extend from the mountains to the sea (Figures 1 and 2), reflecting the Hawaiian belief that the land, sea, and all living things are interconnected. Traditionally, the goal for each ahupuaʻa was to provide communities everything they needed for survival through agriculture, fishing, and gathering. To ensure equitable distribution of resources, the aliʻi (nobility) would use strategies like allocating larger ahupuaʻa to less fertile agricultural regions. The ahupuaʻa embodies the values of sustainability, connection, and well-being, values that have greatly impacted our approach to environmental planning in our project.1

Hāna exists within an ahupua‘a. Situated in one of Hawaii’s most remote regions, Hāna is a small rural community on the eastern coast of Maui, Hawaii (Figure 3). With over 71% of Hāna’s residents identifying as Native Hawaiian, the community is deeply rooted in Hawaiian culture. Many families have deep ancestral ties to the ‘aina (land), which is reflected in their environmental stewardship and sustainable farming practices. Hāna is renowned for its stunning natural beauty, including lush rainforests, dramatic coastal cliffs, pristine beaches, and cascading waterfalls, and attracts many visitors. However, Hāna’s remote location has created challenges for the community. With a poverty rate of 22%, a lack of economic opportunity and rising costs of living and real estate as a result of wealthy landowners moving to the area have contributed to socioeconomic disparities.2

Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike (Figure 4) has emerged as a community-led organization that provides Native Hawaiian youth with the tools to navigate these modern challenges while still being rooted to their cultural identity. The name is a Hawaiian proverb that means “in doing, one learns,” and encapsulates the organization’s core philosophy of hands-on learning and empowerment. Integrated into the K-12 school system, Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike engages youth in real-world vocational projects in construction, farming, and culinary food services that serve the community, especially the kūpuna (elderly). Through hands-on learning opportunities and community engagement, Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike equips youth with valuable skills, instills confidence, and fosters a strong connection to cultural and community values.3

2 “Ma Ka Hana Ka ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi.”

3 “Ma Ka Hana Ka ʻIke.”

Going back to the ahupua‘a as the framework for environmental indigenous planning, it is important to acknowledge that the community organization Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike exists inside the Hāna community and the Hāna community exists inside the ahupua’a which is inside a tourist ecosystem where people are entering and existing all the time, where the commercial boundaries do not match the natural boundaries.

After we visited Hāna and spent time with the community, it became clear that tourism plays an important role in Hāna with its negative and positive impacts on the environment and the community. Tourism is a big part of Hawaiʻi’s economy and culture. It represents roughly a quarter of Hawaiʻi’s economy. In 2019, the tourism industry supported 216,000 jobs, yielded nearly $17.8 billion in visitor spending, and contributed more than $2 billion in tax revenue4. The goal is not to get rid of tourism but rather how to achieve sustainable tourism and support the needs of the local community through the deliverables. How can the deliverables provide tools through which the community and the tourists can move around in the confines of the boundaries together and learn how to be respectful and responsible of land and natural resources.

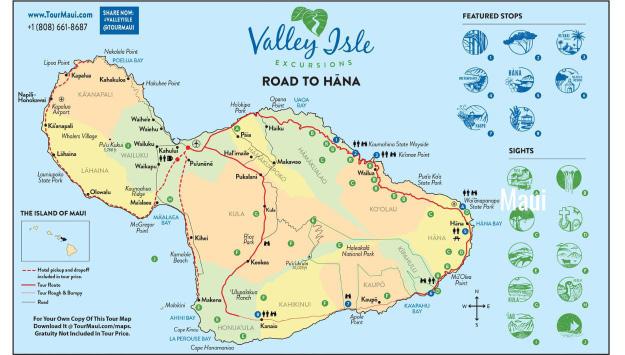

To contextualize the challenge of tourism, let’s take a look at the Hāna highway. The first one being the Hāna Highway, the red loop seen in the figure below, is the hub of tourism. Hāna remained fairly isolated until the completion of the Hāna Highway in 1926, which created a direct connection to the nearest major city— Kahului.5 The road is narrow and causes dangerous traffic build up when people stop, especially for local commuters (Figure 5). With frequent visits to these sites there are changes that happen within the landscape such as erosion and landslides. The community wants tourists that are passing through to be aware of the cultural and environmental importance of these sites (Figures 6 and 7).

4 “Rebooting Hawai‘i’s Visitor Industry – Hawaii Sea Grant.”

5 “About-Hana Ranch.”

Figure 5. This map shows the Hāna highway in the red loop starting from the Kahului.6

6.

“5 Routes for the Road to Hana.”

7.

Another example is the Hana Ranch, a group that plays an important role in tourism in Hāna. The resort group owns 3600 acres in Hāna including the Hana hotel, the Hana Ranch restaurant (the only restaurant in town besides food trucks), and a farm which has around 1100 cattle. They also own 20 acres of breadfruit, banana, and citrus orchards. The breadfruit orchard is in partnership with the National Breadfruit Institute.7

To understand the role of the Hana ranch, let’s take a deeper look at the history of it. The ahupuaʻa system discussed above continued until the 18th century when European and American immigrants arrived in Hawaiʻi and began to introduce their own systems of land ownership. George Wilfong opened the first sugar cane mill in Hāna in 1849, and by 1883 there were six different sugar plantations operating in the region. The sugar industry gave way to the tourist industry in 1946, as the closing of the last sugar plantation coincided with the opening of the Kaʻuiki Inn by Paul Fagan (later called the Hotel Hāna-Maui).10

7 “About-Hana Ranch.”

8 “Hana Maui Restaurants | Hana Ranch Restaurant | Hana-Maui Resort, a Destination by Hyatt Hotel.”

9 Purchased for $9 Million, East Maui’s Hāna Ranch Now on the Market for $75 Million | Maui Now.”

10 “About-Hana Ranch.”

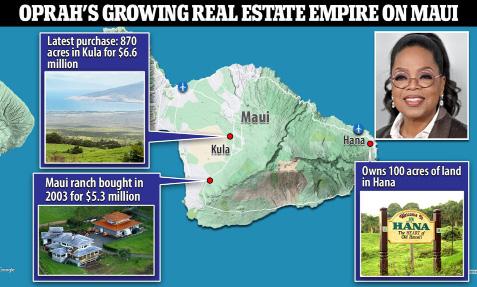

The hotel is a luxurious coastal hotel with spa, business and other hospitality services (Figure 8). The hotel also built bathrooms and showers in Hamoa beach, an ancient burial ground, and they were trying to build more when they found bones and skeletons of the ancestors (Figures 9 and 10). The hotel wanted to continue the building, but the community rallied against it, and they were able to stop the project and honor the bones of their ancestors. This is a clear instance where the cultural and environmental values of the indigenous community do not align with the commercial values that are at the heart of the tourist industry. Additionally, Hana Ranch also sold 200 acres of coastal land to Oprah Winfrey in 2005 (Figures 11 and 12).11 With celebrities such as Oprah buying land in Hāna, one can only imagine the value of real estate increasing especially the coastal lands which are important sacred sites for indigenous communities.

Figures 11 and 12.

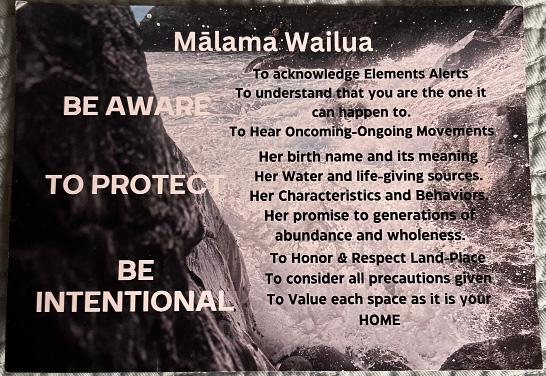

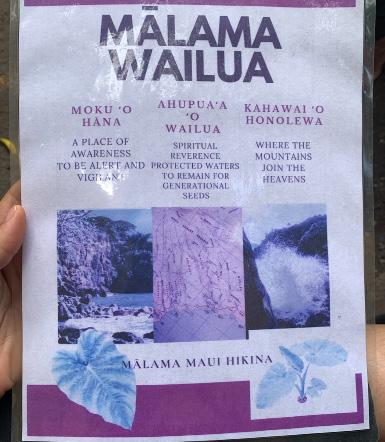

On the other hand, there are community organizations that are working on promoting sustainable tourism and mitigating some of the challenges tourism entails. Community members have formed a grassroots group called Malama Wailua (Figure 13)15 to educate tourists about their core values which are awareness, protection, and intentionality. Wailua meaning “two waters” is the waterfall you see in the picture, and is one of those hot spots right before the national park Haleakalā that is habitat to rare birds (Figures 14 and 15). Mālama Wailua raises awareness about why tourists shouldn’t be swimming in the waterfalls to help protect the fish from the chemicals of their sunscreens, or to not fly their drones to make sure the birds are able to fly freely. They also advise tourists to not go to dangerous places such as the path to red sand beach (Figures 18 and 19). A lot of people have been severely injured in this path. They want tourists to be respectful of the community’s wishes such as not going to these places. One of these community members said, “we want people to come and visit Hāna but we want them to bring their values with them, we want them to treat our land and home the way they would treat theirs”.

Throughout the semester, we listened to our partner, Lipoa Kahaleuahi, to identify deliverables that can support the organization and the community mitigate these challenges. At the beginning, the understanding based on the discussion with Lipoa was that she was asking for four deliverables.

The first deliverable is a multi-layered map following the ahupua’a method, incorporating a community plan focusing on historic sites, natural resources, land use, agricultural sites, ecological aspects, tourists sites, and real estate developments.

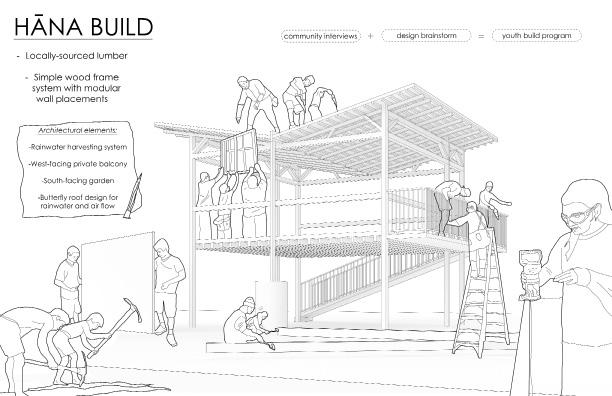

The second deliverable is creating an architectural blueprint for tiny-homes that feature sustainable design solutions for elderly-living. Inspired by Honsador Lumber package homes, the architecture design will suggest a malleable design that is affordable and designed specifically for Hāna’s climates.16 The blueprint will feature a fully functioning tiny-home that works with the natural environment, weather, the flow of water, wind and air.

The third deliverable is a report documenting the perspectives, histories, values, challenges, and goals regarding land stewardship, community development, language, and cultural revitalization.

The fourth deliverable is in response to the recurring issue of flooding: the goal is to conduct research on floods in Hāna and propose flood adaptation systems such as water cycle management, buffering techniques, drainage improvements, and sand-based flood prevention methods.

After reviewing her requests, we planned to work on the first deliverable, which was the multi-layer map, and if finished in time, we will work on other deliverables.

In having the honor to visit Hāna and spend more time with Lipoa, the space, the land, and listening to community members and elders from the community, we identified three ways to mitigate some of the challenges that tourism imposes on the community. Informed by these challenges, the deliverables aim to support the Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike in their mission of supporting the community members and upholding their core values. The first one is the report on the Mahele farm that is a part of the Ma Ka Hana ka ‘Ike. Mahele farm is located at the Kahanu gardens and it is providing food for the elders in the community. The second one is the mapping toolbox as a way to collect data, share their own narratives and stories about their land and their environment to tourists, and promote sustainable tourism. The third one is an architectural layout of a house that is conducive to Hāna’s climate and supports Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike’s youth construction program, Hāna Build.

16 “Package Homes | Building Homes for over 30 Years.”

In Hāna, Maui, sustainable tourism and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) converge through local initiatives like Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike and Kahanu Gardens. Kahanu garden, as seen in (Figure 20), is also a home of sacred temple known as Pi’ilanihale Heiau, which is under protection by the Kahanu Garden Management.

Figure 20. Kahanu Gardens.

These programs not only educate visitors about sustainable living and environmental stewardship but also bolster community resilience while preserving cultural values by addressing local challenges like food insecurity, floodings, erosion and many other climate related vulnerabilities. This approach promotes a deeper, reciprocal relationship between the tourists and the locals and local environment, ensuring tourism supports both cultural preservation and ecological sustainability. With these challenges and opportunities in mind, we have gathered a report which reflects on the land and people of Hāna within the context of environment and climate, at a deeper level. The report can be shared upon request.

Briefly summarizing, the report is analyzing overall geographical, cultural, social and ecological qualities of Hāna and is providing a picture on Hāna’s environmental vulnerabilities.

The group visit to Hāna made a significant impact on the team and how we started to think about Hāna. We had the privilege to be hosted by locals and were provided an opportunity to look at Hāna from a local Hānain’s eye. We started to realize that Hāna is not just a beautiful place that has incredible beaches, mountains, rainforests and tasteful veggies and fruits. Hāna is more than just a place for many beings and non-beings. Benefiting from being in such a remote corner of the Maui island, Hāna and the people of Hāna have had the opportunity to preserve their cultural values and give Hāna and its residents enough space to embrace each other. This was not something neither was observed from nor was reflected on the documents, maps, and images we have found online before the visit to Hāna.

Hāna’s rich and vast cultural and ecologic fabric has been taken care of very well. The people of Hāna are well connected to the spirit of Hāna. Emerging generations for instance, are connected to Hāna, to the land, beings, nonbeings and the people of Hāna. They get involved in production and care- the farm is a place to produce

food for elderly and children of Hāna, and the youth work there. They are heavily involved in the construction side of things, too. Older generations are also very well connected to Hāna and everything in it. Farm for instance was built with the wisdom, experience and advice of the elders. Farm workers do not hesitate going to elders when there is a challenge or a need for a wiser approach. Mahele Farm, Kahanu gardens and the people of Hāna work for each other, and work together for Hāna. Mahele Farm as seen below is on the skirts of Ko‘olau Forest Reserve is blended in native flora and fauna fabric by the coast of Hāna, is a home to many empowering and collaborative actions all centering ancestral wisdom and traditional ecological knowledge.

In closing, Mahele farm is just an amazing example of sustainable tourism which also has rich TEK qualities in it. We cannot stop talking about how we were impressed yet incredibly amazed to see TEK’s incorporation in every aspect of Hāna including the Mahele Farm and Kahanu gardens. Incorporating TEK is beyond collecting data from the tribal members, it’s a collaborative action that brings youth and elders together to manage cultural and ecological resources intergenerationally.17 Traditional Ecological Knowledge is not just a data set that needs to be collected and secured, it’s a process that puts the planet at the center of care and gathers all beings and nonbeing with the same amount of respect around it. Tourism can be very empowering and enriching in the case of Mahele farm if it’s practiced within the cultural values of the place.

The reflections in this chapter are based on the interviews done with Mahele farm managers and Hāna locals. Summary of conversations in this section and the extended report integrate comprehensive insights from the discussion done with Mahele farm managers and the locals of Hāna, aiming to provide a thorough understanding of the project’s scope and its strategic thinking.

17 Henn, Ostergren, and Nielsen, “Integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK) into Natural Resource Management.”

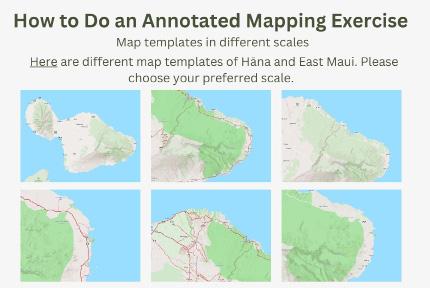

The mapping toolbox was created in collaboration with our partner after several conversations. Initially the deliverable was to create a multi-layered map following the ahupua‘a method, incorporating a community plan focusing on historic sites, natural resources, land use, agricultural sites, ecological aspects, tourists sites and real estate developments. However, we decided to think of a sustainable practice where Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘lke and the people of the community can continue to collect data, tell their stories and create archival materials through these multilayered maps. Therefore, we agreed on a mapping toolbox specifically to collect data and share the stories attached to important sites. The toolbox provides a step by step guide for Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘lke to annotate and create multilayered maps using softwares such as Felt 18 and Mapbox19. The toolbox provides a participatory step by step guide where elders and youth can sit together and annotate important cultural and historical sites as well as an online step by step guide where an individual can spend time on their own and annotate the map with important information they are aware of. This mapbox went through several iterations after receiving feedback form our client. There was also a workshop to pilot test the toolbox with our partner.

Figures 22 and 23.

In the workshop we held with community leaders Lipoa and Aunty Lehua, we started with an activity focused on annotating a physical map with cultural and ancestral knowledge related to water sources (puna) in the area, including the Puna of Wailua Falls, Maka‘alae, and Haneo‘o/Hamoa.

During our workshop, we discussed the importance of the puna in Hawaiian culture, as these natural springs or freshwater springs are vital for sustaining life and agriculture. The puna also carry historical and cultural significance, including legends, traditional uses, and ecological importance. This knowledge is important to preserve because the puna exist beneath the land, not visible from above ground.

18 “Felt - The Best Way to Work with Maps on the Internet.”

19 “Mapbox | Maps, Navigation, Search, and Data.”

To preserve and share this valuable knowledge, we then digitized the annotated map using Felt. Each marked location was transferred onto a collaborative digital map, ensuring that the cultural narratives associated with each puna were accurately captured and documented for future reference. Felt maps can be shared via a URL link or email, giving the creators the agency to control the privacy and visibility of the maps.

In conclusion, through the mapping toolbox, we aim to empower communities to preserve and share their cultural heritage while promoting sustainable tourism practices that respect and celebrate Hāna’s natural and cultural treasures. For community members, engaging with mapping fosters a deeper connection to their cultural heritage and natural surroundings. It enhances technical skills related to digital mapping that may open the doors to future opportunities. Collaborative mapping also strengthens community cohesion and collective action towards cultural and environmental conservation. For visitors, accessing certain maps provides a richer understanding of Hāna’s cultural heritage and the significance of Hāna’s landscapes. Tourists can learn about sacred sites, historical narratives, and traditional practices, fostering greater cultural sensitivity. The mapping toolbox bridges community engagement with sustainable tourism, enriching experiences for both locals and visitors alike while promoting environmental stewardship and the preservation of Hana’s cultural stories.

Upon request, a link to the mapping toolbox as well as the different map scales created as templates for the participatory mapping exercise using Mapbox can be provided.

24.

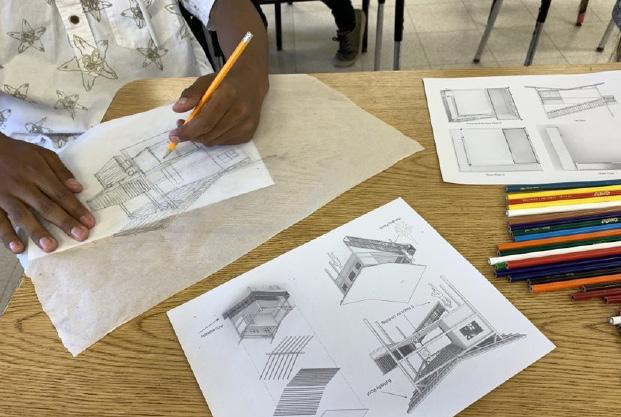

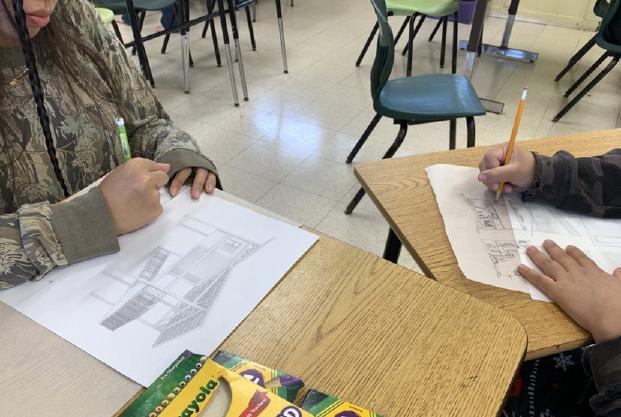

During our time in Hāna, we had the opportunity to lead workshops in our fields of study such as: computer science, planning, landscape design and architecture. To lead the architecture workshop, I proposed a sustainable tiny-home design for the high school students and invited them to design a tiny-home. The workshop entailed having floor plans and perspectival prints for students to trace for their own reimagination and creative designs. In addition to the architectural tools they were given, students were also asked to think geographically where they might construct and site their tiny-home. By keeping in mind the building’s orientation towards the sun, as the island’s sun rises in the east and sets in the west. Meaning that the best sunset views appear on the west-side of a home and for gardening and plant-growing purposes, a south facing home garden receives the best light. One of our students in the workshop, Maui, designed his west-facing tiny-home with an open bottom floor level garage and was very excited to design a protective rock wall surrounding his home. He placed his tiny-home alongside the mountainous terrain and in the east-side facing of his home, included a fenced zone for his horses and other farm animals. It was amazing to have the opportunity to see how students were excited to imagine their own future living and the cultural and architectural elements that were important for them to include.

Figures 25 and 26.

Ultimately, the purpose of designing a tiny-home for this proposal was to establish a design that could be implemented within the Hāna Build programs that youth could help design and build. Through my research of the Honsador Lumber ‘package homes’, it helped me see that these common colonial housing designs gave residents limited design autonomy based on their living needs.

It became evident to design a tiny-home that not only featured elements of sustainability design but also could be adapted to the needs and preferences of its home-user. The structure is designed on stilts for flooding occurrences and its butterfly roof collects rainwater. The pipes connected to the roof allow for water storage in a barrel that can be used for watering the south-facing home’s garden through its water harvesting system. The tiny-home features an accessibility ramp for elder support and a west-facing balcony for the best Hāna sunset views! In addition, the bottom floor level can be modulated to host the various programs, celebrations and events of Ma Ka Hana Ka‘Ike.

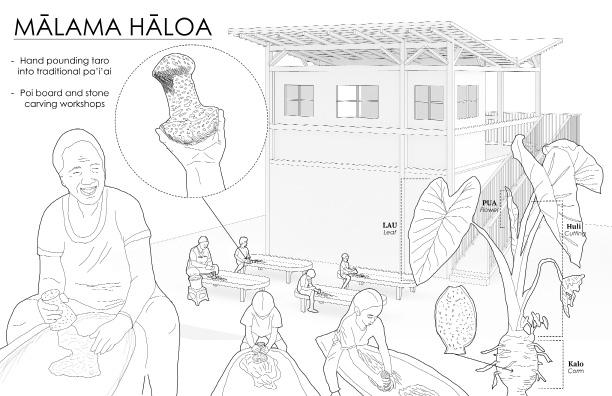

Reimagining the possibilities of this tiny-home through the potential community events featuring, Mālama Hāloa’s programs in hand pounding taro into traditional pa‘i‘ai (poi), poi board and stone carving workshops.

Inspired by Mahele Farm, gardening activities can occur on the south-side of the home garden.

While inviting the community to participate in a co-living home, introducing a shared balcony space that transforms into an outdoor community kitchen. The co-living design is inspired directly by the intergenerational community culinary events of Kahu ‘Ai Pono.

Through the building program Hāna Build, students will collaboratively work together to design and build the tiny-homes for its community members. The simple tiny-home design can be modulated to fit the needs of the community and include improvements they see best fits! Design-build construction is a great way for students to learn about architecture and design while actively impacting their communities. The hopes of the tiny-homes would be to create more affordable and sustainably designed homes to combat issues of high-increase costs in home purchases and the climate-change effects of our built environment.

Moreover, the four architectural renderings (Figures 29, 30, 31, and 32) demonstrate how the tiny-home can be activated through its sustainability design while also supporting the cultural and educational programs of the community.

Figure 28.

29.

Figure 30.

Our collaborative efforts with Ma Ka Hana Ka ‘Ike have led to significant strides in addressing the multifaceted challenges confronting the Hāna community within the framework of indigenous environmental planning. Guided by the principles of the ahupua‘a system, our journey commenced with an immersive exploration of Hāna’s cultural heritage and environmental dynamics, illuminating the intricate interplay between land, sea, and community.

Through the development of three key deliverables—a Mahele Farm report, a mapping toolbox, and an architectural layout for sustainable tiny-homes—we have endeavored to foster community resilience, promote cultural preservation, and nurture environmental stewardship. As we transition to the next phase, we entrust these initiatives to our partners for further immersion and development, confident that the ethos of Māʻawe Pono, comprised of eight phases including ‘Imi Na‘auao (Search for Wisdom), Ho‘oliuliu (Preparation of Project), Hailona (Pilot Testing through Action Research Project), Ho‘olu‘u (Immersion), Ho‘omōhala (Incubation), Ha‘iloa‘a (Articulation of Solution(s)), Hō‘ike (Demonstration of Knowledge), and Kūkulu Kumuhana (Pooling of Strengths), will continue to guide Hāna towards a future defined by empowerment, resilience, and cultural revitalization.

In embracing the ethos of Māʻawe Pono—‘Imi Na‘auao, Ho‘oliuliu, Hailona, and beyond—we recognize our role as stewards of wisdom, architects of change, and advocates for community well-being. By pooling our strengths and aligning our efforts with the aspirations of the Hāna community, we lay the foundation for a future where sustainable tourism, cultural vibrancy, and environmental sustainability converge harmoniously. Through collective action and a steadfast commitment to shared values, we affirm our dedication to supporting Hāna as it emerges as a model of indigenous-led development, guided by the principles of wisdom, preparation, and holistic empowerment.

Purchased for $9 million, East Maui’s Hāna Ranch now on the market for $75 million.

“Purchased for $9 Million, East Maui’s Hāna Ranch Now on the Market for $75 Million | Maui Now.” Accessed May 10, 2024. https://mauinow.com/2022/07/09/purchased-eight-years-agofor-9-million-hana-ranch-hits-the-market-for-75-million/.

“5 Routes for the Road to Hana: Choose Your Road to Hana Adventure - The Hawaii

Vacation Guide,” October 14, 2022. https://thehawaiivacationguide.com/routes-for-road-to-hana/.

“Ahupuaʻa System » Independent & Sovereign Nation State of Hawaii,” June 13, 2019.

https://www.nationofhawaii.org/ahupuaa/.

“Felt - The Best Way to Work with Maps on the Internet.”

https://felt.com.

Go Hawaii. “Hana Maui,” February 14, 2017.

https://www.gohawaii.com/islands/maui/regions/east-maui/Hana.

Goodale, Matt. “Pi’ilanihale Heiau.” National Tropical Botanical Garden (blog), October 15, 2020.

https://ntbg.org/news/piilanihale-heiau/.

“Hana Community Endowment Fund.”

https://www.hanaaloha.org/.

Hāna Maui! “Mālama Maui Hikina.”

https://hanamaui.com/malama-maui-hikina/.

“Hana Maui Restaurants | Hana Ranch Restaurant | Hana-Maui Resort, a Destination by Hyatt Hotel.”

https://www.hyatt.com/en-US/hotel/hawaii/hana-maui-resort/oggal/dining.

Hana Ranch. “About.”

http://www.hanaranch.com/about1.

Henn, Moran, David Ostergren, and Erik Nielsen. “Integrating Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK)

into Natural Resource Management.” PARK SCIENCE 27 (2011 2010).

Honsador Lumber. “Package Homes | Building Homes for over 30 Years.”

https://honsador.com/package-homes/.

Kahakalau, Kū. “MĀʻAWE PONO: Treading on the Trail of Honor and Responsibility.” In The Past before Us,

Edited by Nālani Wilson-Hokowhitu, 9–27. Moʻokūʻauhau as Methodology. University of Hawai’i Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7r428d.7.

“Luxury Boutique Hotel & Resort in Maui | Hana-Maui Resort, a Destination by Hyatt Hotel.”

https://www.hyatt.com/en-US/hotel/hawaii/hana-maui-resort/oggal.

Ma Ka Hana Ka ʻIke. “Ma Ka Hana Ka ʻIke.”

https://www.hanabuild.org.

“MA‘AWE PONO: Treading on the Trail of Honor and Responsibility by Kū Kahakalau - Google Search.” https://www.google.com/search?q=MA%E2%80%98AWE+PONO%3A+Treading+on+the+Trail+of+Honor+and+Responsibility+by+K%C5%AB+Kahakalau&oq=MA%E2%80%98AWE+PONO%3A+Treading+on+the+Trail+of+Honor+and+Responsibility+by+K%C5%AB+Kahakalau&gs_lcrp=EgZjaHJvbWUyBggAEEUYOdIBBzIzOGowajeoAgCwAgA&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

“Mapbox | Maps, Navigation, Search, and Data.”

https://www.mapbox.com/.

Maui Guidebook. “Kahanu Garden & Pi’ilanihale Heiau,” November 16, 2011.

https://mauiguidebook.com/road-to-hana-maui/road-to-hana-sites-to-see-maui/kahanu-garden-piilanihale-heiau/.

“Maui’s Hana Highway: A Vistors Guide by Kepler, Angela: Good Paperback (1993) | WorldofBooks.”

https://www.abebooks.com/9780935180626/Mauis-Hana-Highway-Angela-Kay-0935180621/plp.

MIT SOLVE. “Ma Ka Hana Ka ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi.”

https://solve.mit.edu/challenges/2023-indigenous-communities/solutions/75551.

National Tropical Botanical Garden. “Kahanu Garden.”

https://ntbg.org/gardens/kahanu/.

Pennock, Lewis. “Oprah Buys 870 Acres on Maui for $6.6M as Megarich Takeover Continues.” Mail Online,

March 8, 2023. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11835975/Oprah-snaps-870-acres-Maui-66M-amid-anger-megarich-takeover.html.

“Rebooting Hawai‘i’s Visitor Industry – Hawaii Sea Grant.”

https://seagrant.soest.hawaii.edu/rebooting-hawaiis-visitor-industry/.

Shaw, Gabbi. “Oprah Winfrey, Who Owns 1,000 Acres of Land on Maui, Angered Fans with Her Fundraiser

after the Wildfires. Here’s a Rundown of Her History with Hawaii.” Business Insider. https://www. businessinsider.com/oprah-winfrey-land-maui-hawaii-details-photos-history-2023-9.

Solomont, E. B. “A Massive Maui Ranch Next Door to Oprah’s Property Asks $75 Million.”

Wall Street Journal, June 21, 2022, sec. Real Estate. https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-massive-mauiranch-next-door-to-oprahs-property-asks-75-million-11655845544.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “Traditional Ecological Knowledge for Application by Service Scientists,” 2011. Vaughan, Mehana Blaich. “HE HAKU ALOHA: Research as Lei Making.” In The Past before Us,

https://www.fws.gov/sites/default/files/documents/TEK-Fact-Sheet.pdf.

edited by Nālani Wilson-Hokowhitu, 28–38. Moʻokūʻauhau as Methodology. University of Hawai’i Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv7r428d.8.

“What We Do - Yourcier,” October 12, 2021.

https://yourcier.org/what-we-do/.

Wilson-Hokowhitu, Nālani, ed. The Past before Us: Moʻokūʻauhau as Methodology, 2019.

https://uhpress.hawaii.edu/title/the-past-before-us-mo%ca%bboku%ca%bbauhau-as-methodology/.