ARTISTS OF THE NORTH COUNTRY

Mitchell Fine Art

27 June – 22 July 2023

Artists of the North Country brings together a collection of works gathered over the past four decades.

Predominantly bark paintings, they have been sourced from Western, Central and Eastern Arnhem Land and the Tiwi Islands to the north. They depict various creation events and stories of significant spiritual and cultural importance to the creators of the artworks. Along with body painting and rock art, bark paintings are one of the dominant art forms throughout Arnhem Land. The various styles, whilst unique, have evolved from a common, related visual language.

The works in this exhibition from the Tiwi Islands derive largely from the body painting designs, or Jilamara, associated with mortuary ceremonies. Distinctive, innovative mark making is supported and as such encourages a diversity of design and execution from artist to artist.

The art of Western Arnhem land has an obvious connection to the art that adorns the rock walls and caves in over 10,000 galleries located in the rocky escapements of this country. There is a predominance of figurative artworks with crosshatching, or Rarrk, inside the figurative elements and expanses of negative space surrounding them.

The art of eastern Arnhem Land whilst often figurative, employs compositions of geometric patterns outside of the figures. There are more often than not designs specific to the clan of the creator.

The art of Central Arnhem Land is often an amalgam of these compositions.

All of these areas have a rich history of mark making and visual expression that draws on stories of creation and traditional law and customs. In a culture with no written language, these stories are passed down from generation to generation through dance, ceremony and art.

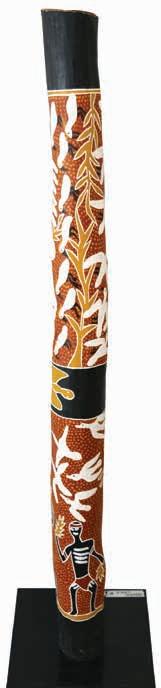

Also featured is a selection of Larrakitj from North East and Central Arnhem Land. They are the trunks of eucalyptus trees that have been hollowed out by white ants. They are collected, stripped of the external bark and painted with clan designs. They were once used as traditional coffins and were integral in the final sequence of a series of mortuary ceremonies.

These works have been collected and held in a private collection since the early 1980s. This is the first time that these works have been offered to the market.

Mike Mitchell DirectorA785 ‘Mimi Spirit’ 2001

acrylic on canvas

84 x 61 cm

Mimis are reclusive, shy spirits that inhabit the rocky escarpment country. They hide in the rocks during the daylight hours and only emerge at night, travelling under the cloak of darkness.

The only people to see them are Marrkidjbu, the medicine men of the Kunwinjku people. Mimis impart knowledge to the Marrkidjbu who in turn pass on this information to the Kunwinjku. This is how humans gained all knowledge, including dancing, safe foods to eat, art, language, ceremony, history – all aspects of life were passed on from the Mimis.

Mimis are generally friendly, only becoming angry when a wrong is done to the innocent and the defenceless.

Here the artist has depicted a single male Mimi.

Samuel Namundja

AB2 ‘Luma Luma’, 1992 natural ochres on stringybark

91 x 23cm

Luma Luma the giant was a mythical ancestor that originally travelled from Macassar in the Indonesian archipelago to Western Arnhem Land during the time of creation.

He initially settled on Mooroongga Island in the Crocodile Group of Islands with his six wives and extended family. From here he visited the mainland by changing into a whale. Here, he was greeted by Ngalyod, the Rainbow Serpent. Together they explored the country as Ngalyod guided him to the various clans and introduced him. At this time there were no fish in the inland billabongs and waterways. Luma Luma and Ngalyod introduced barramundi and mackerel to ensure an ongoing food supply for the people of this country.

Luma Luma taught the Mardayin ceremony to the people of Western Arnhem Land. It is a strict set of rituals and dance that informs many of the laws that dictate daily life and law and order. Separate dance and song sequences are given to those of the Yirritja and Dhuwa moieties. These are performed together on a common dance ground.

All of Luma Luma’s cultural knowledge and his Ranga (sacred objects) were eventually passed on to ceremonial leaders. This information and lore have been passed down through the generations to this day.

Samuel Namundja

AB3 ‘Galawan and Mandjudurrk’ (Goanna and Olive Python), 1993 ochres on stringybark

90.5 x 23cm

The Mardayin ceremony is one of the most sacred to the Kunwinjku people. The nature of this ceremony is secret and the information unavailable to the uninitiated.

The goanna (Galawan) is a key figure in the Marrdayin ceremony and is of great importance for Kunwinjku people of the Dhuwa moiety in Western Arnhem land. Participants of both Dhuwa and Yirritja moieties perform the final sequence when the Goanna Men bring a large carved goanna to the ceremonial ground. Songs are chanted about the goanna ancestors and their deeds during the creation period and dances imitate these deeds.

In this painting the artist has depicted two mature Galawan, indicating initiated men. The Olive Python (Manjudurrk) is painted between the two initiated man and alludes to other aspects of the ceremony.

The Rarrk, or crosshatching on the figures is specific to the artist. During the ceremony participants adorn their bodies with designs of their ancestors who transformed from human into Djang, the creatures in which the spirits dwell.

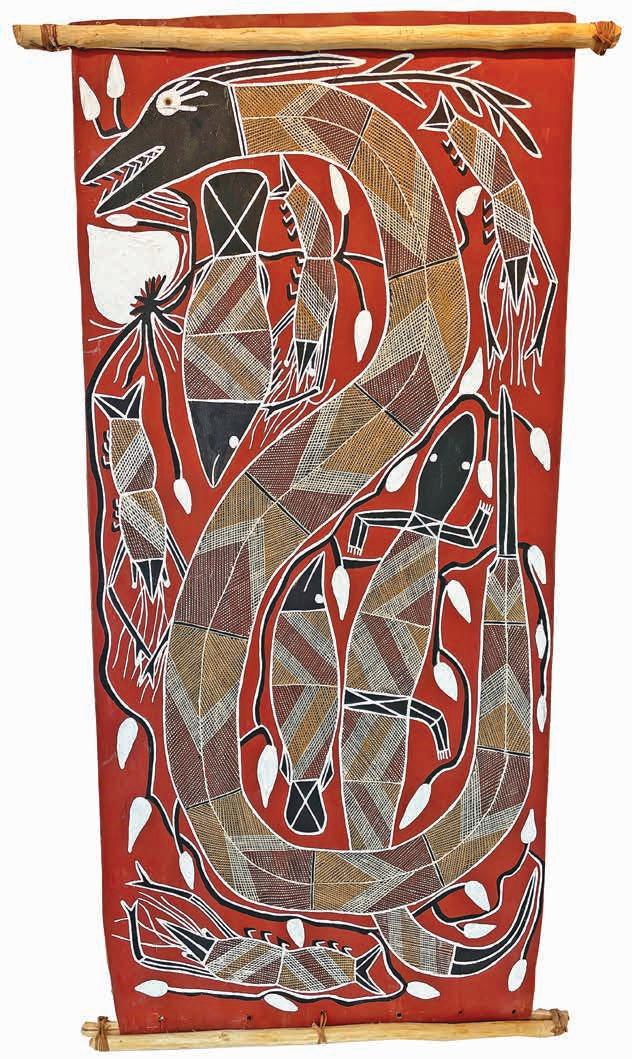

AB4 ‘Yingana - The Mother Rainbow Serpent’, 1992 natural ochres on stringybark

112 x 60cm

During the creation period Yingana, the Mother Rainbow Serpent came from across the Arafura Sea to the country of the Kunwinjku people in Western Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. She carried within herself numerous creatures. Some were half human and half animal, bird, or fish. She spewed them out at various sites, declaring these locations sacred to those left there.

Over time Yingana grew angry and dissatisfied with the various creatures due to their actions. She caused a great flood during which she swallowed everything. She carried them inside her for along time until she regurgitated them in the form that they bear today.

Yingana then gave birth to two more rainbow serpents, a son, Ngalyod and a daughter Ngalkunburriyaymi. Ngalyod is the more powerful of the two, creating numerous sites of significance not only throughout Western Arnhem land, but as far away as Croker Island, across the Arafura Sea. His sister Ngalkunburriyaymi did not venture far beyond Numbulwah Rock where she created a number of sites of significance for Kunwinjku people of this area.

Yingana is known to primarily live underground but can be in many places at one time. She can be both extremely protective if the local people are in danger, and violently destructive at other times if laws are broken or her sleep is disturbed.

In this painting she has been depicted with the head of a crocodile. Adorning her head is a head dress made from Djelmi (feathers) and bush string that represent the bones that protruded from her head during the Dreamtime. These bones assisted with the digging required in her subterranean movements. Around her are various creatures for which she created. Shown are Galawan - the goanna, Namarnkol – the barramundi and Barrdjungka – the water lily.

The Rarrk, or crosshatching designed depicted on all of the figures represent the clan design of the artist.

Andy Garnararrdj

AB6 ‘Turkey Dreaming’, 1992 natural ochres on stringybark

50 x 106cm

During the creation period there existed the ability to transform from human to plants, animals, birds or objects such as plants or rocks.

Benuk was once a man who changed into a bird after a confrontation with a hunter and was threatened with a spear. Often, they would return to their human form, but just as often they would retain this new form, or djang, in which their spirits would live forever.

The Kunwinjku that claim Benuk as their dreamtime ancestor would perform ceremonies to honour them and to celebrate their deeds during the creation period. This would involve decorating their bodies with Benuks design and dance and sing of his exploits in the dreamtime.

In this painting the artist has depicted a male and female as they protect their nest full of eggs. The painting references fertility as much as the ancestral being.

Artist Unknown

AB9 ‘Brolga Dreaming’ 1994

natural ochres on stringybark

42 x 27cm

Malumin Marawuli

AB10 ‘Baru - The Crocodile’ 1999 natural ochres on stringybark

67 x 52cm

Baru, the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus Porosis) is the totem of the artist. It is depicted here in the billabong know as Guyapi. Its nest is hidden in the vegetation and Baru is shown here protecting the nest and the unhatched eggs (mapu).

The diamond designs are the clans design (Madarrpa) and represents the country.

Bill Namundja

AB11 ‘Namarnde Daddjurdu’ 1992. natural ochres on stringybark 102 x 44cm

This painting depicts the one-legged spirit known as Namarnde Daddjurdu. To this day he watches over the spring known as Namarnkol Djambarrmengh. He is known to live in the Marrunj or palm trees that grow around the water source. The palm tree is depicted in the lower left corner of the painting.

A large rock near the spring is said to be a Namarnkol (Barramundi) that jumped there from the Liverpool river during the creation period.

The area surrounding Namarnkol Djambarrmengh is known as Namangardabu.

Mick Cousins

AB16 ‘Kitehawk Dreaming’, 1990 natural ochres on stringybark 84 x 27cm

Here the artist has depicted his totem the Kitehawk. It is seen here protecting its eggs.

Mick Cousins

AB17 ‘Kitehawk and Goanna Dreaming’, 1990 natural ochres on stringybark

90 x 22cm

Here the artist has depicted his totem, the Kitehawk accompanied by two sand goannas. The contours represent a specific geographical feature of significance to the artist in relation to Kitehawk Dreaming.

Artist Unknown (Tiwi Islands)

AB27 ‘Body Painting’ natural ochres on stringybark

50 x 23cm

Purukuparli and his wife Bina were the first Tiwi man and woman. Purukuparli established the first Pukamani (mortuary) ceremony after the death of his son. In Tiwi culture there is an intimate link between art and ceremony. Where the Tiwi differ from many other Aboriginal groups is in the lack of focus on specific totems, dreaming sites or secret rituals. Rather, their rites of passage concentrate on a sequence of public ceremonies that ensure the adherence to and clearing of a variety of Pukumani taboos associated with death and mourning.

The Tiwi word for ceremony is Yoyi, which directly translates to ‘dance’. Dancing is the primary activity in the pukumani rituals. Both men and women are expected to participate in these dances.

It is considered that it is at this time in the ceremony that people are in the most danger from the spirits of the dead, known as the Marapurti. The body painting that adorns the dancers’ bodies are thus intended to conceal their identities. It is in fact a disguise.

Since the body adornments and body painting are intended more as a concealment or disguise than in providing context or connection to specific stories of cultural significance to the deceased or the participants, there is great latitude given to creativity and the artists imagination in the designs. This has also overlapped into the creation of painting in a two-dimensional form on bark, paper, linen etc.

Artist Unknown

AB32 ‘Ginga- The Crocodile’ natural ochres on stringybark

65 x 23cm

Bear remnants of a distressed label. Using predictive text, the label on verso reads:

‘Western Arnhem land – Rock Country NT’.

This is a totemic reptile – The Crocodile.

See it rising up from the depths of a waterhole called Lok Lok.

The crocodile was one a man who dived into a waterhole out of loneliness; rejected by the tribes as he sought to take a woman who belonged to another and in any case was the wrong skin for him.’

Gunybi Ghanambarr

L01 ‘Untitled Larrakitj’, 2001

acrylic on Woolybutt Eucalypt (Eucalyptus Miniata) 102 x 12cm

Yananymul Yunupingu

L02 ‘Untitled Larrakitj’ 2001

acrylic on Woolybutt Eucalypt (Eucalyptus Miniata) 137 x 10cm

Valerie Dhamaranji

L03 ‘Untitled Larrakitj’ 2004

acrylic on Woolybutt Eucalypt (Eucalyptus Miniata) 146 x 14cm

Ronald Nawurapu

L04 ‘Untitled Larrakitj’ 2001

acrylic on Woolybutt Eucalypt (Eucalyptus Miniata) 147 x 12cm

Thompson Nganmirra

AB34 ‘Nyalyod- The Rainbow Serpent’, 1997 natural ochres on stringybark

155 x 50cm

In the tradition of the Kunwinjku, Ngalyod the rainbow serpent has many manifestations. In this painting the artist has depicted him as being that of a huge python. Ngalyod has many powers and is also responsible for the creation of many ceremonies, rites, tradition and for many of the taboos for these people.

The Rainbow Serpent also has control over the weather and the season. When travelling, he prefers to travel underground as it leaves him undisturbed by people. He relishes the ability to appear suddenly near those that do not adhere to law and the taboos that he has imposed. He will generally spend his time in a pool within a deep gorge or in the vicinity of one of his scared sties.

During the wet season he will create the monumental cloud formations for which this area is known, by blowing large amounts of vapour from his breath and then sits atop the clouds that form. He uses his tongue to send out lightning strikes and generate loud thunder by growling from deep in his throat. He uses his tongue to pierces the clouds and send down the rains.

If laws or taboos are broken Ngalyod will punish the people.

This painting tells the story of a group of people who were camped beside a waterhole called Gabari. They were to hold a ceremony and sent messages out to clansmen and the Ngaladj dancers to attend. A small boy who lost his mother en route to Gabari became overwhelmed with grief as he had already lost this father. His Aunty tried to console him by catering to his every whim.

When they reached the site of the ceremony the Nawaladj’s (orphan) aunty went into the water to gather water lily roots for the child. She then went off in search of more food, sitting the Nawalodj on a rock. From here he spotted some cooked madaneg roots cooling before being eaten. He began to cry incessantly when refused the roots, the old people explaining that it was forbidden for the roots to be eaten by the children. When his Aunty returned and heard his petulant wailing, she pleaded with him to stop, warning him of Ngalyod’s presence in the nearby waterhole. He only cried louder, awakening the rainbow serpent.

Ngalyod was furious, emerging from his watery sleep and slid closer to the ceremonial site. He watched and listened as they explained the law to the nawalodj. Ngalyod’s anger increased as he watched the boys behaviour and he caused water to well from the ground, trapping the people. He then killed all the people, starting with the orphan. The Njaladj dancers who were still in the rocky escarpment above were turned to stone.

The Ngalyod ceremony has been performed at this site near Gabari waterhole over the millennia. It is known as the Namaladj site. It is not sacred or secret and involves gift giving as a central activity.

The purpose of this ceremony is to instil the need to observe traditional laws and taboos into young people. There are serious consequences for all if they do not listen to the leaders and obey when instructed in such matters.

Bill Namundja

AB5 ‘Mimi Spirits’, 1992 natural ochres on stringybark

123 x 67cm

Mimi are reclusive, shy spirits that inhabit the rocky escarpment country around Gunbulunya in Western Arnhem land. They hide in the rocks during the daylight hours and only emerge at night, travelling under the cloak of darkness.

The only people to see them are Marrkidjbu, the medicine men of the Kunwinjku people. Mimis imparted knowledge to the Marrkidjbu who in turn pass on this information to the Kunwinjku. This is how humans gained all knowledge, including dancing, safe foods to eat, art, language, ceremony, history – all aspects of life were passed on from the Mimis.

Mimis are generally friendly, only becoming angry when a wrong is done to the innocent and the defenceless.

In this painting the artist has painted a male and a female Mimi and various plants and animals.

Sammy Blanassi

MK18259 ‘Freshwater Dreaming’ 2001 acrylic on linen 104 x 112 cm

Here the artist has depicted various fauna and flora of significance. A Jawoyn man from Beswick, this is freshwater country. Animals depicted include the freshwater crayfish. The plant is the water lily which grows profusely in the billabongs in this country and are a food source.

Rerrkiwangga Munungurr

MKMK18260 ‘Mana (shark) Dreaming’ 1999 acrylic on linen

119 x 187.5cm

This is a very early work by this highly regarded artist. Here she has painted ‘Mana ’, the shark. The design is from the Djapu clan and the two sharks represent the two clans, the Djapu and the Galpu Painted also is Dhalatjpu, the green sea turtle, the stingray Marantjalk and other saltwater fish.

Dorothy Djukulul

MKMK18272 ‘Gumang’ (Magpie Goose) 1998

acrylic on linen

139 x 142 cm

Dorothy Djukulul holds a unique place in the history of painting from this region. Knowledge, love, and custom is handed down through the generations from the father to son primarily through song, dance and art. It was of great concern to her father that the sole person that could carry on his design and received specific cultural stories was his son George Milpurrurru. After exhaustive consultation with senior clan elders Dorothy was given permission to paint a number of stories that were taboo to women.

As such she was taught to paint by her father Ngulmarmarr.

Dorothy Djukulul’s language group, the Ganalbinga people, are one of the largest groups in Central Arnhem land. They are freshwater people and their traditional country stretched across the Arafura swamps of Central Arnhem Land.

The Ganalbinga are known as the Magpie Goose people and their homeland, the Arafura swamp lands, is unique. The swamps are home to large numbers of Gumang (magpie goose) and Djukululs clans, the Gurrumba Gurrumba, translates directly to ‘a flock of geese’.

At the end of the monsoon, in the season known as Midawarr is when the Gumang nest and lay their eggs. The Gumang, their eggs and their nests are sacred to the Ganalbinga. The nests are considered a resting place for the souls of the ancestors.

Midawarr is considered the start of the egg hunting season. At the commencement of the gathering of the eggs a ceremony called Gurrubumbungu (which reference the droning of the didgeridoo or yidaki ) is performed to ensure that the geese will continue to lay eggs into the future. Another smaller ceremony is held with the eggs and the newest born babies. This signals that the season is open. The mothers paint themselves with white clay around the chest and under the armpit in imitation of the geese and is said to represent the breast milk. Men will perform the dance of the Gumang with cooked eggs, during which they will break the eggs open and give them to the mother. The eggs are rubbed over the children, ensure that they and their mothers will have good health over the infant period. This is the ceremony of the Gurrumba Mapu (goose eggs).

Depicted also is Karritjarr the black headed python. The python is the dreaming of the Djukululs mother’s mother. Its tongue strikes lightning, and its saliva will seed the clouds. Karritjarri causes the first rains of the wet season and is vital in the cycle of the Gumag. He signifies fertility and the abundance to come.