Each day

Walking to the market from my room

Giants watch me slowly ramble by No judgments, just head in sky

With me as an afterthought.

It’s amazing how good it feels

Seeing the mountains after a storm Covered in snow

And it’s even more amazing

Considering how miserable it would be To be there freezing.

Venus too is beautiful From a distance.

I turn the corner as I head down to the market And face the I-90 from a slight elevation. Across the freeway, the angel Moroni atop the Mormon temple With his golden horn proclaims

The gospel of the Golden Plates

That a man named Smith discovered In New York,

A place I love to visit But would never want to live in again.

From this distance

The I-90 feels hopeful

A way to escape the confines of my room And start fresh.

East to the Cascades

West to the Olympics

Nowhere in between.

On a clear New York fall morning

My father held my hand

As we rode the subway downtown to where he worked. I spent the day watching him,

Breathing the musk of books and boxes in an old office

With a big window that looked out from the twenty-third floor

At the lines of buildings moving in parallax

Against the blue sky and long shadows clipping the streets

Where all those things I’ve read about

In poems, novels and memoirs happened.

The tiny people down there

Fit neatly in the crosswalks, bus stops and store fronts

A busy diorama destined for the attic

To be revisited when there’s no more room for memories

In the living room.

My breath fogged the window

And I wiped it to keep watching the coursing crowd. I couldn’t see their faces well enough

To know what they might be feeling

And my father painted a smile or a frown here and there Whenever I asked a difficult question.

And I listened and questioned and listened and questioned. Fifty-eight years later he was still explaining As I held his hand

To help him cross the street.

The sun is beautiful when it’s clear

And the moon reflects the sun. We weren’t made to be there

Only to appreciate it from a distance.

Al Roth

53.1

VOLUME 53, NO. 1 SUMMER 2023

LAURENCE ROTH EDITOR

AMANDA LENIG CREATIVE DIRECTOR

PATRICK THOMAS HENRY ASSOCIATE EDITOR Fiction and Poetry

ANGELA FULK ASSOCIATE EDITOR Profession and Pedagogy

RANDY ROBERTSON ASSOCIATE EDITOR Reviews

HEATHER LANG ASSOCIATE EDITOR Online

NICK STEPHENSON WEBMASTER

CRYSTAL VANHORN SUBSCRIPTIONS MANAGER

ALLEE MEAD COPYEDITOR

EMILY HARRIS EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

about NeMLA

The Northeast Modern Language Association (NeMLA) is a scholarly organization for professionals in English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, and other modern languages. The group was founded as the New York-Pennsylvania MLA in 1967 by William Wehmeyer of St. Bonaventure University and other MLA members interested in continuing scholarly discourse at annual conventions smaller than that hosted by the Modern Language Association. In 1969, the organization moved to wider regional membership, election of officers, formal affiliation with MLA, and adoption of its present name.

NeMLA continues its traditions of intellectual contribution and advancement at the 55th Annual Convention, to be held March 7–10, 2024 in Boston. “Surplus” is the keyword for 2024 NeMLA convention for critical and creative work that, in addition to the commonly associated meanings of profit and value, can be more broadly construed as excess or excessive, as surfeit, or what is leftover, or unwanted: an excess of emotions (anger, fear, passion, desire), for example; or surplus time (leisure or its absence); or populations rendered “surplus”—migrants, the marginalized, the unemployed, the incarcerated.

NeMLA is delighted to host, for the Thursday opening address, Rickie Solinger, an historian of reproductive politics and the author of Wake Up Little Susie: Single Pregnancy and Race before Roe v. Wade (1992, 2000) and Pregnancy and Power: A History of Reproductive Politics in the U.S. (2007, 2019). The Friday keynote event will be given by Tiphanie Yanique, a professor at Emory University and the acclaimed writer of the novel Land of Love and Drowning, the focus of this year’s “NeMLA Reads Together,” which won the 2014 Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Award and the Phyllis Wheatley Award for Pan-African Literature, among other honors.

Please see the NeMLA web page at www.nemla.org for information on joining the organization and about the fellowships, awards, and publications available to members.

Modern Language Studies appears twice a year, in the summer and winter, and is a publication of the Northeast Modern Language Association.

© 2023 Northeast Modern Language Association • ISSN 0047-7729

staff

NeMLA board of directors 2023–2024

EXECUTIVE BOARD

MODHUMITA ROY, Tufts University President

VICTORIA L. KETZ, La Salle University Vice President

SIMONA WRIGHT, The College of New Jersey Second Vice President

JOSEPH VALENTE, University at Buffalo Past President OFFICERS

CARINE MARDOROSSIAN, University at Buffalo Executive Director

ASHLEY BYCZKOWSKI, University at Buffalo Associate Director

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

DONAVAN L. RAMON, Kentucky State University American and Diaspora Studies Director

ANGELA FULK, SUNY Buffalo State College British and Global Anglophone Studies Director

MARIA PLOCHOCKI, City University of New York CAITY Caucus President and Representative

JULIA TITUS, Yale University Comparative Literature Director

MARIA MATZ, University of Massachusetts–Lowell Creative Writing, Publishing, and Editing Director

KATHLEEN KASTEN-MUTKUS, Stony Brook University–SUNY Cultural Studies and Media Studies Director

ANN MARIE SHORT, Saint Mary’s College Diversity Caucus President

YVES-ANTOINE CLEMMEN, Stetson University French and Francophone Studies Director

ANDREA BRYANT, Appalachian State University German Studies Director

SAMADRITA KUITI, University of Connecticut–Storrs Graduate Student Caucus Representative

ESTHER ALARCON-ARANA, Salve Regina University Hispanic and Lusophone Studies Director

GIUSY DI FILIPPO, College of the Holy Cross Italian Studies Director

JINA LEE, Westchester Community College–SUNY Professionalization and Pedagogy Director

MARIA ROVITO, Penn State University at Harrisburg Women’s and Gender Studies Caucus Director

submission information

Authors should submit their manuscripts using MLA style for citations and notes. Please use parenthetical citations that reference a works cited list; notes and works cited should appear at the end of the text. Submissions to the reviews section do not need a works cited list.

We take electronic submissions in Microsoft Word format. These should be set in 12 point Times, double spaced, and use superscript for footnote numbers rather than the footnote function. Please clear all identifiers from electronic submissions, including the author and company fields in “Properties” under the “File” menu.

For submission guidelines, our statement of ethical practices, and link to the MLS Submittable site, visit www.mlsjrnl.com/submissions. Address all correspondence to mls@susqu.edu.

NeMLA membership is not required to submit to MLS; however, membership is required for publication. Detailed submission guidelines and descriptions of all the editorial sections are posted at www.mlsjrnl.com.

subscription information

2022–2023 RATES

Institutions: $75.00

International Shipping: $36.50

Single Copies (Vol. 35 and on): $32.00 for institutions

$22.00 for individuals $15.00 for NEMLA members

$19.25 for international shipping

Subscription agencies receive a 10% discount ($67.50, plus $36.50 for international shipping if applicable).

Send all other subscription inquiries, address changes, and payments to:

Modern Language Studies, Attn.: Subscriptions

Susquehanna University Box 1861

514 University Avenue

Selinsgrove, PA, 17870

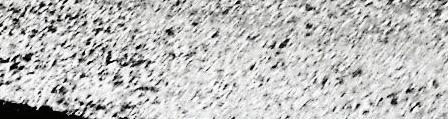

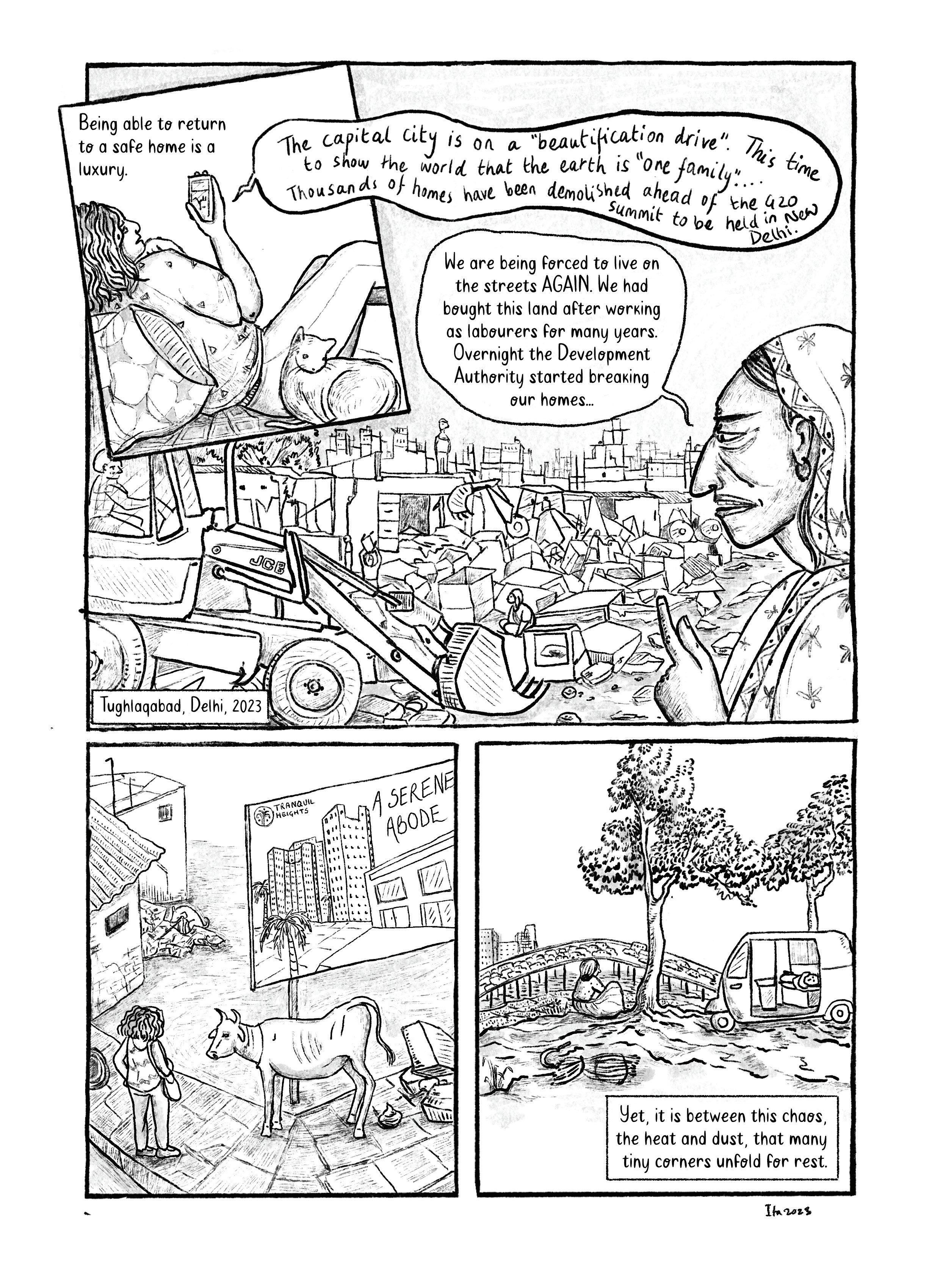

Articles Interview with Ita Mehrotra Raisa Rafaela Serrano Muñoz Demolition Delhi Ita Mehrotra Poetry & Fiction

Waldrep: Glory-Sonnet to the Aviary as Public Liturgy mount moriah hive artifact Meditation on Dürer’s Sudarium Held by One Angel Maria DiFrancesco: Digging Through What’s Mined Annie Diamond: Dubliners Nostos Emily Anna King: 亲爱的爱玲 Incarnadine Jenn Blair: Substitute Review Teresa M. Bejan. Mere Civility: Disagreement and the Limits of Toleration Randy Robertson 10 26 30 34 36 38 44 68

MLS 53.1 contents

G.C.

53.1

articles

10 Modern Language Studies 53.1

11 special cluster

M E

Rafaela Serrano Muñoz,

Córdoba

HROTRA I TA WI TH I NT E RVI E W Raisa

University of

(Spain)

ITA (SUNANDITA) MEHROTRA

is an educator, researcher, and critically acclaimed visual artist based in New Delhi, India. Her nonfiction comics, such as Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection and “The Poet, Sharmila,” have been published by some of the strongest independent publishing companies in India, including Zubaan Books, GoetheInstitut, Yoda Press, and AdAstra Comix, among others. She is currently the Director of Artreach India, a nonprofit organization that provides arts and artists to underserved regions with limited access to traditional education. In that role, she frequently travels to far-flung villages and towns for research and to set up and deliver Artreach’s programs. By exploring the unique stories of these places, she uncovers and engages in the socio-political changes currently wracking India, transforming her experiences into graphic narratives, illustrated texts, and animation.

Mehrotra attended the Mirambika - Free Progress School, a groundbreaking experimental educational setting that strongly supports holistic development, learning through the arts, and independent study. She graduated from St. Stephens’ College, University of Delhis, with a Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy (Hons.) in 2010. She was given the opportunity to participate in a student exchange for one year at Sciences Po, Paris, where she obtained a diploma in French Art History and Culture Studies. She went back to India to complete her master’s degree at the Ambedkar University Delhi, School of Culture (2014). Mehrotra’s 2017 MPhil from Jawaharlal Nehru University’s School of Arts and Aesthetics focuses on feminist graphic narratives in modern India.

I talked with Mehrotra via Skype to discuss contemporary feminism in India in connection with her career, focusing on the memories of her visit with poet Irom Sharmila in the Imphal Central Jail, an experience that she illustrates in the comic “The Poet, Sharmila” in the anthology entitled Drawing the Line: Indian Women Fight Back! (2015). The autobiographical comic “The Poet, Sharmila” depicts Mehrotra’s feelings during her visit to her mentor, Irom Sharmila. As a poet who has fought peacefully for the abolition of the army that fails to protect residents, Sharmila has become a symbol of liberation in India. The strips show Mehrotra visiting the Imphal Central Jail, where the poet was participating in a hunger strike following the Malom Massacre, in which the AFSPA massacred ten innocent bystanders. My interview with Mehrotra examines the difficulties Indian women encounter while expressing their artistic vision through literature, and the integration of feminist education into the Indian curriculum. The interview was held at 1:00 PM (GTM + 2) on June 15, 2022, and then the audio recording was transcribed and lightly edited for clarity.

Raisa Rafaela Serrano Muñoz: You work as a visual artist, art researcher, and educator. Is it possible to educate the population through art starting from when they are young?

12 Modern Language Studies 53.1

Ita Mehrotra: I think it’s specific to the kind of communities I’m working with in India. They are communities with a lack of resources, which have low access to mainstream education. Actually, mainstream schooling is too high-pressure and has so many subjects that the students are not able to deal with them because there isn’t enough help. Whether it’s because the parents do not have enough education or because the school doesn’t give students enough attention, a lot of children in India and in other developing countries who are first-generation learners just don’t fit into the mainstream education system. In these places, when you go in with creative media, visual storytelling, and theatre with games, they work really well. They are useful not just for traditional skills, such as reading and writing, but also for building children’s confidence in saying, “Oh, yeah, we can do this” and “Oh, we love to learn because learning isn’t about pressure and scolding; it’s also fun. And it’s something we can use and make something of ourselves.”

So, we make programs within village schools as well as in urban slums in Delhi. I’m based in Delhi, and my team works mainly in Delhi. From experience, I know artwork as a way to show children that they can do things themselves and also that these creative skills can go a long way to even finding a career.

There are photographers who come out of our programs; there are designers ... Mainstream education won’t offer you that. Even if you get through school, you’re stuck. These young children from low-resource areas have to start earning, so they get stuck in these kinds of low-skilled jobs, which are really frustrating because they don’t like it.

As we’re talking right now, after COVID-19, after the extended lockdown in India where a lot of the children couldn’t access online learning, in this country we are seeing an increase in the education gap between the few who have access to private and online education and the many who have no such access. At the moment, the organization where I work has demanded and claimed that our program and art could play a massive role in bringing back these children who have dropped out of the system, together with offering them well-being in connecting this kind of holistic way of thinking and education, so that the whole body, the child, is growing. Both the brain and the mind are growing and learning skills.

From the experience of the work I’ve done and the work that other educators and artists have done with me, it goes to show that art has a huge role in education. In my own life, if I hadn’t been introduced to art in school, I would have been a wreck.

RSM: You have experience in publication with independent publishers such as Zubaan Books, Yoda Press, and AdAstra Comix. Is it easy to publish feminist concerns, such as gender violence and resilience, in India?

13 articles

IM: It’s really good that there are these strong independent publishing houses in the country, and many of them, like Zubaan Books and Yoda Press, are run by feminists themselves. As an organization, they promote this kind of work. Neither mainstream publishing nor mainstream media anywhere in the world encourage women’s work in telling hard-hitting realities of misogyny and oppression. There is a strong feminist movement in the country that has led to feminist media houses, and they’re very popular; they sell very well. Whether it’s academic institutions, students, or libraries, they will house these books. It plays a role in the way culture is shaped. They influence popular mainstream media as well, to a certain extent, so it’s a tussle.

I don’t think the mainstream media is a feminist media that encourages women to speak out. If so, we wouldn’t need things like #MeToo. There are people who will encourage it, and you have to find them. I wish there were more. There are quite a lot in cities, especially in New Delhi, but not in all of India because it is very diverse. If you go to a small rural town, you probably won’t find a lot of these, but even in smaller areas, there are very strong media houses. There’s one called Khabar Lahariya, a rural press media organization that has women reporters in very rural areas in backward parts of the country, such as Bihar or Jharkhand. These women report on the ground in these villages about rape, harassment, and women’s work, among other topics.

So, what do women in villages do? The understanding is that men are laborers, farmers, and the ones who do all the work. So, there are very interesting traditional roots in our rural economy. In a city like New Delhi, and even in other metropolitan cities like Mumbai or Bangalore, you’ll find really strong feminist-led organizations. There is a voice, and it’s powerful. There are new women comics creators, storytellers, and podcasters who are finding their way and giving different opinions.

RSM: With the publication of your work in English, you can reach women worldwide and inspire them to live the life they want. Are you aware of the importance of language in your comics? What about the importance of images, since everybody, including illiterate people, can get the message?

IM: Focusing on Drawing the Line: Indian Women Fight Back! (2015). At that point, I definitely felt that images had a power that got through to everyone more than words, or at least in conjunction with the text. It’s like words that are created when visuals and text meet. It’s all-encompassing. You feel embedded in the sentiment of what’s being said; you’re not just reading a description.

I’ve always felt this is also my language. It’s what I do. It’s not just about what others might feel. It’s about how confident I feel about a certain way of working. For me, it’s always been about withdrawing into our text, and the words matter to me a lot.

14 Modern Language Studies 53.1

I find language accessible to me as a way of walking through, talking about, or coming together on difficult issues. Bringing visuals and text together in a graphic narrative format is something that has stayed with me and grown into a journey for many years now. It’s grown from my first work, and in Drawing the Line: Indian Women Fight Back!, I felt I could bring this together as a story, and definitely the hope is that different people, younger and older, who are maybe not so comfortable with reading a book, might read something that has pictures with a bit of text.

In this context, there is little text on a page. It’s literally 250 words or something like that. What happens when you use such little text is that only the significant things can be written, so you won’t have extra words. You really have to boil it down to find the essence of what you want to say. That also becomes powerful because you don’t have 10,000 words to use. You have 250 words that mattered the most to you, and that’s why you kept it there. So, when somebody’s reading it, you’re only showing very poignant bits of text.

It’s engaging, because if you don’t say much with words, you read a little bit, and you have little bits of drawing in between, so you’re given clues. And if it’s a difficult story about your work, like my story, both drawings and text help. My story is about activist Irom Sharmila, and it could be a really big book. There are books about her, but if it’s just this little bit of text and bits of drawings, fragments of the story, it means I’m inviting you to enter this world and fill in the gaps with your imagination. There’s no right or wrong in that. I’m not saying that you’re making fiction out of it, but as a viewer-reader, the power to place yourself within the narrative is where the work of thinking together can begin. I don’t just want to give information. I’m not making propaganda. It’s a way of putting things out there and thinking of what might happen when somebody else is thinking. That, for me, is a much more interesting dialogue than just lots of text or just a big painting.

RSM: You are used to traveling to different cities in India to help children in education. Do you think feminist education in the Indian curriculum is possible nowadays?

15 articles

"I DON’T THINK THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA IS A FEMINIST MEDIA THAT ENCOURAGES WOMEN TO SPEAK OUT."

IM: It’s so far from reality. Mainstream education itself has only taken more right-wing turns. We have a right-wing government, and it is bringing in an extremely aggressive, male, and misogynistic environment. Partly due to its Hindutva ideology and the promotion of Hinduism at the cost of other religions, they see women’s rights, LGBTQ+ rights, and any of that as radical and not positive. They’ve made changes in textbooks as well, only giving examples that are anti-secular and misogynistic, which show men working more than women. Women are meant to run the family. That’s very much what this government believes, and in every little cultural production or educational aspect, what they keep saying is that women are supposed to raise their children and run the family. That’s what is driving the country backwards at the moment.

Education is controlled by the government, and the massive drive is backward, not forward. There is the education here, but there is also segregation. There are some elite private schools that follow international standards, like anywhere else, so they follow international baccalaureate programs. But those are only for a few of the rich, so the masses of the country go to government schools. Schools that are government-affiliated follow the government textbooks, and those are the ones that have gone backwards in the current system. There are really good alternative schools run by activists, NGOs, and artists, and these are sometimes for rural children. However, there are very few. The masses in the educational system are using backward textbooks. Education is not going forward.

Is India any closer to a feminist education system? Right now, not at all. In the mainstream system, I would have to say that, sadly, there are artists and activists who are struggling to carry out their work. There is always an undercurrent, which is very strong. Activists, artists, writers, and theatre people are always pushing at the system. We’re an argumentative country, we love to debate, and we love to protest, so there’ll always be the other side. But we have to acknowledge that, at the moment, there’s a very backward push by the forces that are very strong on the right.

RSM: Comics and graphic novels are pretty new formats in literature. Can we offer alternative education through comics and graphic novels? Do you think this format is easier for sending the message to youth?

IM: Using visual stories works especially well in developing countries where there are first-generation learners who have dropped out of education. I strongly believe that seeing the work I’ve done, whether in cities or villages across the land, not just for very young children but for those who are grown up and haven’t had access to education, is really gratifying for me, as it’s something they can do immediately and something they can also look at, as it’s very visual. It can work for adults and children.

16 Modern Language Studies 53.1

RSM: In India, many supporters still support the Hindutva ideology, a doctrine that elevates Hindu religion and mythology to the center of society by reinterpreting Indian history in accordance with its own preferences. With this background, what are the challenges that Indian women face when they want to express their art and focus their work on achieving equality and empowering other women?

IM: The government controls the educational system at present, and this backwardness is turning into an aggressively patriarchal state, which is something you can see in the streets right now. I go out into the streets of New Delhi, and there are more and more of these aggressive gangs of boys only, who have been given free rein to move around like sharks, blaring Hindu music, and they look like they’re ready to beat people up: they’re very aggressive. And this is the top leadership of the state at the moment. They literally claim that the size of their chest is a sign of how great they are. It’s a backward turn. It’s not just about being anti-secular, but about being extremely patriarchal, and that is definitely not an environment that supports the work of women as feminist voices in cultural production. The work never ends.

My recent work, Shaheen Bagh: A Graphic Recollection (2019), is about the past. It came out three years ago. The book documents the movement against anti-secularism, in which Muslim women have organized across the country. These protests started at a place called Shaheen Bagh in Delhi, with Muslim women saying they are completely against the law brought in by the government that makes it impossible for a Muslim immigrant coming to India to seek citizenship but invites immigrants from other countries or other religions to seek citizenship. It singles out Muslims, and even Muslims within India, who are saying that India questions their citizenship, even if they’ve been here for generations. At this time, it’s not possible to do any work, bring out a book, and find the right publishing house. There are voices when I go into these places, like the Shaheen Bagh women. They are the ones who are leading the country. At this moment, I feel justified when I see these women who have organized enormous protests against what the government is saying. So many thousands of people are gathering across the country. The government is not helping at all to promote the voice of women. Nevertheless, despite the authority and patriarchy of the state, feminist voices are surging.

It would be great if the government allowed a free voice, but as the opposite is true, women are rising up against the government. When the government was pro-feminist, feminists were doing other things. They were working for education, peoples’ rights, housing, and various things that are still to be done. But at this moment, those voices are having to fight against the curbing of basic human rights in the country. The work of feminists continues, but what it’s doing, how it’s asking for support, how radical it is, and the nature of it at the moment is focused on challenging state oppression.

17 articles

RSM: Do you use online platforms such as your website and social media to discuss feminist issues and raise awareness among your readers? What are some of the most common misconceptions about feminism in India that you have encountered?

IM : I don’t use online media so much because I like to do things a little more slowly. I sit with paper and my drawing equipment. It takes me a little more time. Publishing in books or in independent scenes for small exhibitions, books, and publishing houses is what has worked for me. I’ve also done small jobs on essays for new websites, and that’s given me more work.

There’s one called The Wire, which is a perfect media house in India, where I published something at the same time, Drawing the Line . The same activist, Irom Sharmila, was the protagonist of a second story that happened a few years ago.

There are artists who are challenging work every day, and many of them choose to go online, and it can work. Using Instagram only really does work. Using Twitter to gather support and post things also works. I don’t usually use all kinds of media, but I used it when the protests broke out against the government two years ago in India in the winter of 2019. That’s when I started relying on it. There were very few artists and people writing about the protests, so I just made a few posters at that time and posted them on Instagram and WhatsApp, but just to friends. It was fascinating to see how it went to many more people than I thought. Just telling people this was happening was a call to action. I saw people going to the protest afterwards, so sometimes these sites can be a mobilization tool, just by saying, “Oh, tomorrow there is a protest or something is going on, and we need to get there just to channel people into doing something.” Currently, it’s also very effective as a way to organize and spread the word that it has worked. I have used it at times for these specific moments. I don’t really like my own website. I hardly have anything going on there, so I really shouldn’t keep it going.

18 Modern Language Studies 53.1

RSM: One of the ways of approaching and understanding gender identity is through the deconstruction of traditionally feminine and masculine roles that have been established as conventional. With this argument in mind, how would you define the concept of identity? What is Indian identity for you?

IM : I don’t think there is a single answer at all. I definitely think a person’s identity goes through life with endless stereotypes and conventional thinking of what genders are supposed to be and whether the labels given at birth are based on gender in every life experience.

I constantly criticize it, and the feminist movement across the world criticizes it too. Our lives are governed by these boxes and classifications. Moving out of them is an extremely difficult task because you first have to realize that they’re not natural.

On the other hand, I lived in France for a year, and I don’t think it’s true that India is more gendered and has more stereotypes than any other part of the world. They [are] just different kinds of stereotypes. For instance, in the kind of clothes that women and men wear, the differences within that are still extremely prevalent around the world. Even something as simple as how you dress, how you look, and how you’re supposed to behave are things that cut across the developed and underdeveloped parts of the whole world.

In the Indian context, there is, of course, a rigid patriarchal structure, beginning with family and marriage, which is moving into women’s work in education and the public space. Throughout one’s life, you either accept those limitations and therefore propagate them because the moment you accept them, you are also part of keeping that system intact, or you don’t accept them. If you don’t accept them, then you’re always fighting against them. You’re always having to question it and come up against various rules, whether it’s in the family or in a public space. Things happen when traveling through the city, when you’re in your educational space, in your workspace. Even in French circles, the way guys behave is different from the way girls behave, so you’re constantly tackling the problem. I see myself in that space of constantly questioning and confronting.

This idea of Indian identity is almost a conventional stereotype that the mass media and mass culture would like to promote. In Bollywood, there are stereotypes of how an Indian woman might behave and what she does throughout her day, with a lot of family values. It just doesn’t show the reality of women’s work and how they actually are in the country. They live, survive, and work. There are many of us who go against these stereotypes and challenge them every day in our work. The question is not what Indian identity is for me; the question really is whether or not there is an Indian identity. It’s such a binding constraint to think of. Even the person who grows up here saying, “India is the biggest secular democracy in the world,” is contradicted by the notion of

19 articles

the modern state, which is extremely controlling. Especially right now, nationhood is a term that’s used by the right wing to claim that there are no different Indian identities. Feminists claim that they don’t want to say they are good Hindu Indian women.

I appreciate my culture very much and my association with this country, the diversity of voices, and the diversity of women’s work. It’s amazing how women are able to organize, not just in their own lives with the children and family they support through their work, but also their voice, which is very clear about the economy and politics. It’s great to see the way women actually are in this country because not only are they strong in shaping the economy and history, but they also have the strength with which they speak about what politics should be. That’s what I associate with India: diversity and resilience, not any sort of mass stereotype at all, and these challenges as well.

RSM: In your comic “The Poet, Sharmila,” you describe the memories of your visit with Sharmila in the Imphal Central Jail. And you explain how she altered your ideas about nationhood, struggle, unity, and the body. Can you explain in what ways you changed your ideas about these concepts?

IM: It’s been about ten years since I traveled there. She was in a part of the country that’s quite far from New Delhi, in the northeast of India in a state called Manipur. She was in the jail of the capital city of Imphal. She was in prison because she was on a hunger strike against the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA), but they were saying that she was trying to commit suicide, which is illegal, so they dumped her in jail. Then, they force-fed her through a tube.

The point is that growing up in New Delhi, you’re given this idea of the country as being one unanimous whole, as a big democracy of unity and diversity where everyone loves the country, with a sort of picture of almost everybody speaking the same language, reading the same newspapers and literature, and so on. You grow up with that kind of sensibility, and as Delhi is a metropolis with people coming to find work from all over, you see people from the North, South, East, and West, all living together. One of the most important parts of the experience with Irom Sharmila was the change and traveling to a region that is worlds apart from what I’ve grown up with. It was very important for me to be able to shatter this idea of a unanimous country that is fed to us, which is instilling a forced patriotism without our consent. Knowing that there are very different parts of this country and that they don’t connect in many ways but are actually against each other if we go into the northeast, as in the state of Kashmir, there are politically challenging spaces because the ethnic communities in the northeast don’t want to be associated within the democratic nation of India. They want to be separate, so there are military groups that are armed and underground, and they create threats, but the threat is something a lot of the people will support because they don’t have their basic rights met from the country.

20 Modern Language Studies 53.1

So, it’s very complicated, and in answering the problem, instead of using dialogue and democracy, as is supposed to happen, the Indian state goes in and forces the region to be part of the country, and they use that force not just once but every day. Therefore, you need armed forces to be surrounding the entire area, but this heavily militarized state, which is not protecting against another army or infiltrator from another country, is actually going against its own people to control the country—to be able to secure it, to tell the world that we have a nation. You’re actually continuously creating a nation by force, and the army not only does this, but it also rapes, loots, and has free rein to do what it wants.

So, the meeting with Sharmila shattered the idea that I was fed for a very long time, and it showed me that common people need to take measures which are so radical and extreme, like going on hunger strike for years on end just to be heard, because otherwise you wouldn’t get any news from these parts of the country. If you’re in the controlling center of the country, like New Delhi, you tell people that we’re a good, happy democracy, but you don’t show what’s happening, the struggles of the people in that country. When activists like Irom get international support, then people in India know what’s happening.

That’s what happens when you get an award for peace. She got The Magsaysay Award [ ed. note: honors those who have demonstrated service leadership to Asian peoples] as a peace activist, and then even people in India noticed a lot more. Of course, the surroundings, the geography, the military context, and being in that space with an informer helped me break away from this idea of nationhood. Then, going into the jail to meet her and seeing what an activist needs to do to their body to be heard and so on.

It was a whole second portion of it. Moreover, there was another important factor involved. It was a difficult time for me because I was 17 or 18 years old and had just finished high school, and it’s that transition period in life where you’re asking who you are and what you are going to do, and then you come across the fact that everything you believed in, in terms of democracy and nationhood, doesn’t exist. So, these experiences shaped me as a person and my radical ways of thinking. For that reason, it was crucial, and I am thankful that I could do it because otherwise if you grow up in New Delhi and you have a privileged education with good learning, you think you’ve learned everything, but you can basically not know anything. So, at least I had some understanding from the kinds of books I read and by listening to activists and authors. It’s a whole different thing to travel, to visit a prison and so on.

RSM: In “The Poet, Sharmila,” Sharmila explains the story of her grandmother fighting against the British in 1939 during the Second World War. How important is a heritage to you? Do you think that when history is taught at schools, it is altered?

21 articles

IM: I only got to know this story when I went there, and the researcher I was with was writing a book. For me, I was learning firsthand from meeting people there, from the museum. It was all about history, which I knew nothing about, and I think it’s so important. Also, there were so many strong people at that time. Women fought these wars and defeated the British. Also, just the fact that women were able to do this is incredible. I wish they were part of every history textbook, at least in school. People would know that this happened. It’s wrong not to include it. These are huge parts of history, so it’s not there in the textbooks, for sure. It’s not in our school curriculum, and I wouldn’t have known about it if it hadn’t been for researchers, going on this trip, and reading the book later. I hope these events will be there, but it’s going to take some time for that to happen to have this true history in textbooks.

RSM: One of the messages of your comic “The Poet, Sharmila” is the importance of sisterhood. We see it in the story of Sharmila’s grandmother and your feeling of friendship while speaking to Sharmila. How important is sisterhood among women?

IM: With activists like Sharmila, it’s something infectious. It’s really powerful to imagine that somebody can take on the state and bring so much attention to the issue and to carry out these struggles. I remember it so clearly, how she was in jail, being force-fed through a tube, and yet she’s laughing and talking about food and things she loves. All these images she’s hung in her jail room, which are cut-outs from magazines and newspapers. There’s a deep human connection. There’s definitely a sisterhood and a friendship that has led to all the later protests organized by women, with women interviewing female leaders of different movements, protests, and struggles. In some way, it’s not just about them at all. They’re so open about sharing what they’re doing, saying who they are, and also about really giving space to others. That’s something that women also have to understand early on. Because when they’re organizing things

22 Modern Language Studies 53.1

"I REMEMBER IT SO CLEARLY, HOW SHE WAS IN JAIL, BEING FORCE-FED THROUGH A TUBE, AND YET SHE’S LAUGHING AND TALKING ABOUT FOOD AND THINGS SHE LOVES."

for the family and society, it’s always through this interdependence. It’s through coalitions because the only support that many women have had is from each other, especially in rural, developing countries. It’s a type of situation where if a woman takes a stand, the only way she can do it is if she knows there will be another woman to help because it means sometimes going against your family, your parents, friends, and bigger networks of organizations. That definitely creates a very strong feeling of comradery, of friendship.

RSM: The way Sharmila struggled against the AFSPA was through resilience. In fact, she became an icon for the feminist movement worldwide. However, it might be frustrating for her that after 16 long years of a hunger strike, there is still sexual abuse against women by the army. Paradoxically, AFSPA is a group that is supposed to defend the nation. What’s your opinion about this point? What’s the next step in approaching this fight?

IM: There’s so much politics involved. It includes the northeast states, I think six of the states in the northeast, and then Kashmir, and in a way it’s a similar situation, where the national armed forces are in control, and they have the upper hand in Kashmir and in the northeast. But then there are very different pictures about what the politics and the issues are in the northeast. There are a lot of ethnic groups and minorities, many different kinds. Each ethnic group has its own militia and underground organization. Then in the north, in Kashmir, there’s a fight against what they claim are terrorists trained in Pakistan, who are supposedly controlling the Muslim military and organizing these armed attacks on people who are from Pakistan.

On the other hand, the Indian government has a claim on Kashmir and Pakistan. Then, there are separatist movements in Kashmir, so the thing is, obviously, there’s no one response to what should happen with our AFSPA. But, yes, as you said in your question, the national army forces are raping and looting, and they harass the common people, both women and men, and they sexually abuse underage women, married women, and even older women in their homes and in the streets. This is also because they’re from the army that goes into the north from other states. They go in from very different cultures and are sent to the northeast, where they have no association with the people. If you go from the south of India or from the north of India to the northeast, you don’t know the language, and you don’t understand the food, the culture, or anything. They’re posted there for a long period of time, and of course they’re very aggressive, and they know they have the upper hand, so they can avoid lawsuits if they have enough reason to shoot someone on sight.

23 articles

Obviously, even if there is a threat from separatist groups and ethnic struggles, the fact that the army has these powers and that they are not accountable for rape and looting has to be challenged, and the courts have to take action. Now, just like in the past, these actions cannot be justified by blaming separatist groups and militias and saying that they are the ones who are tearing the country apart. No, it’s the army who is doing this, and there is absolutely nothing that can justify the way the army has behaved and is continuing to behave to the present day. Every day there’s something on in the news, some cases of shooting people, some cases of rape, and in most of these cases we will never know how many people were raped or killed or what happened.

The law has to take responsibility for this situation, and these soldiers need some major sensitivity training. Also, there’s absolutely nothing [to be gained] for aggressive men with guns who are sent off to a culture that is not theirs, and this kind of life is obviously deeply frustrating for these men as well. None of this justifies what they do, but this is the situation, so how do we train people to be human beings? How can this kind of vile and extremely aggressive military system control army training of their own people that will change their attitude through education, sensitivity, and gender training for the people sent there? Also, the judiciary and legal systems have to charge people if a case is reported. It’s very difficult for a woman to accuse a soldier of a crime. The bigger challenges of our AFSPA are much more complicated political questions such as political questions, such as how can you eliminate a defensive army completely in a nationalist climate? Other countries might claim Indian territory. China is always waiting to claim Indian territory on the northeast side, so can the army completely go away? Will Kashmir be taken by Pakistan? By China? Those political questions are much bigger, and I honestly don’t think I can even get into all of that or even answer it. But in terms of what to do about rape and harassment by the army, I think anyone could say that enough wrong has happened and that basic measures could be put in

24 Modern Language Studies 53.1

place, but they aren’t in place. Rape is a crime, but it’s there, and it’s legal. What the army is doing is not okay, so it’s a question of putting into action what needs to happen, but that doesn’t happen. We’re a very corrupt country.

RSM: How do you think the feminist movement in India has evolved over the years? What do you think are the most effective ways to tackle gender-based violence in India? Have you noticed a change of mind in new generations toward the feminist movement?

IM: From the little experience I have about the feminist movement in India in the 1980s, there was a huge rise, especially in New Delhi, in feminist groups and organizations. They used things like street theatre and did a lot of work to build awareness and bring up these questions. There were also laws that were passed against rape and dowry, so they were very instrumental in the 1980s as organized collectives in shaping rules and rights for working women.

Over time, I feel there’s now—at present, it’s very dissipated. There’s no organized collective feminist movement like those, and it’s much more diluted. But the use of social media has helped individuals to raise their voices. The same types of movements can happen again with something like the #MeToo online movement. It was an enormous call that went out to academics, artists, media personalities, and people in the government.

The feminist movement is very active, and there are a lot of artists and young creative professionals who cannot even say whether it’s a movement or not. Women today feel freer to speak up at some level, and this is more likely to happen now than even 20 years ago. The tools are here, and the ability to use social media and connect with platforms is something that wasn’t possible in the recent past, so some progress has been made.

RSM: What are the most pressing issues facing women’s rights in India today? How do you see the future of the women’s rights movement in India?

IM: Because of this really strong, fascist, right-wing government, one of the biggest challenges is what Muslim women are facing in the country. It’s something that we can’t shy away from, which is the threat to Muslim women’s education in the country. Nowadays, education is not even available to these women in many parts of the country. If Muslim girls wear a hijab, they are not allowed to sit in the classroom, they can’t come inside, they can’t study, and they can’t take their exams.

Every day there’s a new protest in a new part of the country against an attack on a Muslim woman. If she’s a protester or if she has been part of student activism, she and her

25 articles

family are severely harassed. The case we’re following right now is that of an activist in Uttar Pradesh, whose house has been broken into and her family arrested (this is an especially large threat to Muslim women in the country): it’s a double threat, because they are Muslim, and because the Hindutva government is hunting down Muslims. Also, as a woman in a patriarchal state, the government just can’t accept the fact that Muslim women are speaking up. At the moment, we are giving support and solidarity any way we can, and we are trying to tell this government that not everyone believes what they say.

So, that’s a major one, and in general, as we were talking about earlier, there is a rise in misogyny because the regime is so strongly patriarchal, so it will take a long time to bring back what happened in the course of history with the feminist movement in the past so that women today will have more voice and public recognition. You can see that there’s been a backward movement and an attack on these freedoms, and that’s been a global problem since the lockdown. There’s been a worldwide attack on those who spoke up in the #MeToo campaign. At the moment, there is a bit of a backlash from the patriarchy. It’s amazing how big these waves can be. At present, there is a rise in patriarchal misogyny, so you feel like Muslim women are definitely under this enormous threat, as also the Hindu system. There’s the upper caste, the lower caste (which is the lowest level), outcasts, and Dalit women because it’s a Hindu government, but it’s [not] for all Hindus. It’s a government that is only for a certain sector of upper-caste Hindus, so again here we see a growing attack on Dalit women’s rights and more rape cases are coming out. The police are also turning a blind eye. You can’t report cases, so when it comes to minority women, they’re extremely under attack at the moment by the country. It’s been that way forever, but it has sharply increased under this regime. Because of that, the failure of the economy and the lockdown as well have made things much harder. When there are hard economic conditions, this kind of fascism really breeds because people don’t have what they need and are struggling for their basic rights. Where are they going to turn? To the courts? To the police? It’s the perfect time to oppress people. We have to see these sharp realities on the ground. It’s about minority communities at present and what women are facing with the convergence of anti-secular and fascist policies [and] with the oppression of women within the country.

26 Modern Language Studies 53.1

"YOU CAN SEE THAT THERE’S BEEN A BACKWARD MOVEMENT AND AN ATTACK ON THESE FREEDOMS, AND THAT’S BEEN A GLOBAL PROBLEM SINCE THE LOCKDOWN."

27 articles

28 Modern Language Studies 53.1

NAVIGATING PUBLIC SPACE IN NEW DELHI IS OVERWHELMING—WITH ITS LACK OF WALKING SPACE, NOISE, CONSTRUCTION, POTHOLES AND CATTLE, THAT GENDERED GAZE AND THE CLASSISM.

Over 2023, in addition, India is host to the prestigious G20 summit of various national heads coming together to ‘think’ about international finance and climate change. But to ready the city for it, Delhi literally clears out slums, slum dwellers, shanties, beggars, and without a thought as to where they will go, once forced out.

—I.M.

29 articles

53.1

poetry+fiction

31 special cluster

g.c. waldrep

GLORY-SONNET TO THE AVIARY AS PUBLIC LITURGY

1

I follow the phantoms of April through the slick avenues. Make the child bear the host upon its narrow shoulders, skim the milk-depth of pine’s translucent skin which remains unpierced. The offense of glass, its lucid resistance. Collapse the wound into its constituent folds, its origami testament. I fed the blinded sparrow in its cage for awhile. It was not a child. It is not a voice. The repetition, the brevity, & the goal. We will feast, they say, in the hall of the comedians, vacant now. We will train our hawks. Theirs is a literal haruspexy, starkly legible, glistening. Someone else’s livid indiscretion. 2

Measure the aviary by its oiled hinges. To what degree does form in music obscure truth? The golden ratio, demesne, we don’t have to believe—we can polish the blackened silver, we can suborn the witnesses. Worship as an acoustic space, absolutely. Opening and closing, a larynx, the recessional logic, curve of the beak of a Cooper’s hawk pressing into the vole’s taut viscera. I was wrong, you should have bought the mirror, exchange genuflecting to the vertical axis. You too can contemplate flight, you too can provide forms to structure attention. You can bend at the neck, the waist, or the knee. 3

Collect of the cottonwoods’ transverse floss set for calcite, emblem, antigen. Christ as the living dust, quickened in season. Sand writing into sand, convocation of shamed departures. Empathy demands an oblique plane in which words may slumber or at least rest. Economies of bone suture object to gesture, as motion. Rim of the glass on which I place my canted finger’s blade, is it wrong to imagine it attracts light: rim, blade, each lung’s inverted funnel. Strewn on the cinder path to the new clinic not a garment, but blinding garment’s eye / I walk both towards & away from, Master.

33 poetry + fiction

mount moriah

Throne : filament : throne. I transubstantiate this knowledge, castrato to my body’s slow decline. God holds a mirror in His hand to massage our unbelief.

I shear the rough wool from my body which is like His body, dull foam of pasture-wrack. This filament casts no shadow, I’ve been told & verily believe as some better man breaks me from the brush.

We cannot all be spared, is the hymn they teach us. Seep-clot, breath-clot, I tat my body into fire’s

epic lace. It feels good, a lotioning forest offering up its debit-praise. I char as I unbriar.

O vicar of astonishments, false positives—

let me steal this much: your face as an evening bell. A heart, a lens, a tone.

hive artifact

wheat pours through the mirror without mercy (what we think of as mercy) time is something distant, inklike what is written in wax dies in wax, says an old proverb

soon I (my image) am completely overrun by wheat

I could stop looking I could turn away from the mirror this is the problem with representational language the mirror exists why don’t you ask it, you say so I ask the mirror

when I look down at myself I find the grain become a quickening, live, a cape of wasps

34 Modern Language Studies 53.1

MEDITATION ON DÜRER’S SUDARIUM HELD BY ONE ANGEL

Mica silvering the mortar at dusk, faint wail of an ambulance shaking up the distance, yellow panes against which I brushed & burned myself beyond which hunger thrived, & hunger’s banquet, the sea.

There is nothing new here— accumulations of roses & stones, wrack & the affinity for wrack.

I left you inside a motet by Lassus, in lieu of some better prayer, socialism perhaps at the depth of the pine’s broken root where the entitlements flicker.

I recall every copper instrument I have ever touched, or owned—

the sprains that ran through them—

church of the laughing kings.

Go ahead, extract the blood I’d been saving, my widower’s mite.

The world remains faithfully out of reach. I blink towards it like an Aldis lamp, I wound the sleeping animal.

It kicks inside its dream. It has not borne the fiery constellation. It leans into our comfort, our amethyst observances, every architecture where matter paused, or seemed to, as if it were resting.

35 g.c. waldrep

MARIA D i FRANCESCO

DIGGING THROUGH WHAT’S MINED

Anyone can see it’s a game, because it is. At the molten core, it’s commerce cut loose from chance, from risky margins, where there are cogs mining in invisible tunnels, searching for Eldorado: everything you don’t have. Focus on strategy, on technique, because the goal is to find an uninterrupted path to the cache and then more cash. Hinder operations. Obfuscate. Obtain by any means. Intervene. Muscle in. Win.

Justify what you must.

Kill procedures. Whatever you do, don’t let on that you know that they know–Machiavelli was restored in the matrix, too.

Nonconformist is what they called them because most only live once, or twice if you’re willing to count on baby Jesus.

Penance on the way to Canaan comes with a price. Quests necessitate action, and even rest is a strongly restless verb when you’re preaching to the bleary. Stay focused on the target, set your eyes on the pearl of great price.

Unbelieving are the ones at mass on Sunday. You smell rotting flesh. Validate, appreciate only when they’re watching in their holy robes, otherwise just let xyloid handled chalices and candles speak dove peace.

Young colliers will not talk back at the tunnel temple, and zinc deposits that echo brimstone won’t fuss in dark fantasies.

37 poetry + fiction

Dubliners

Alison reads our tarot on her apartment floor.

Next morning we take a train to Howth; Sam sleeps at the apartment, hungover, while Alison and I climb beside the sea, eat fish and chips vinegarlogged,

raise our pints to Nora Barnacle, Blow Job Queen. We will lose touch, mute our friendship; still possible in the digital world. But this morning no futures exist, no potentials for loss. Just the hills of Howth and last night, seventies American pop songs we sang with locals on guitars in Dublin pubs. Witness greater than genius.

American pop music in Europe so charming: ever a decade outdated, sometimes much more.

ANNIE DIAMOND

39 poetry + fiction

if i do not die, does this violence earn empathy?

or must i bleed he walked into me he said, he said Get out of my fuckin’ way, China!

drunken, stumbling, sharpening his teeth on the last two syllables, grey strands uncombed carcinogens subtle in his sentence, wanting me less than invisible existence undone

such a gentle beast when there is no blood, and yet i hurt

Eileen— can you can you tell me what it takes to stop my silence from assaulting me, to remember those words have nothing to do with me, they were not born because of me

all selfish love and liquor

he was selfish love and liquor and that hurt me more

41 poetry + fiction

亲爱的爱玲

Eileen—

it isn’t the first time. it isn’t the first time i tell myself i am too sensitive.

silence wields no mongoose fangs, no dragon breath, no jade claws pressed together at the edge of an alter swirling with gilded incense amen amen i don’t pray to god they say i don’t look like the people He made the say, God bless you

[sometimes i pray to that god] in the silence

my shoulder blades are pressed against porcelain rose water shimmering with bubbles soft against stomach, thighs, chest

i bleed petal juice beautiful, magenta

Eileen—

i will not crack like this petals pressed into cheekbones of China dolls shatter into pearls beneath your pen steaming

i found my blood written into textbooks stating: it is innate it is innate tastes like lotus seed, sweet cream reddish scales and phoenix feather embarrassed this is all i know

1979,1999

only daughter only daughter

42 Modern Language Studies 53.1

you wrote yourself into two languages

tell me how tell me how

you are unbreakable unfound

color pales in comparison to you

Eileen—

I do not know my birthday but I do know why the rabbit came in fourth. Oh, how clever the rat was jumping off of the ox’s head! And I know how the rabbit sacrificed itself for the Jade Emperor earning a place on the moon with mortar and pestle making medicine from moon rock.

Its body was all it could give and so it earned eternity.

may i earn eternity

You’d say: You are your own diaspora

You are your own so become

43 emily anna king

INCARNADINE

i remember the fool’s gold against my lips little shavings like white onion skin, papery as tears flowed into the divots of my dimples your hand pressed each curled golden sliver further, further past my lips

and you said: swallow

i swallowed down the taste of dry citrus and stone as the pieces scored black lines down my throat

i fell to my knees in the fountain water up to my waist soaking the skirt of the white dress embroidered in sea foam lace

i stood and droplets traced diamond and fell each one a refraction of sour disbelief dampened by my own disdain towards the green in your eyes looking through me

you cupped my cheek and said: embody the beautiful things and you will be worthy

i remember crushed pearl spread across my eyelids irises dyed aquamarine, cheeks brushed with blush fingers and wrist made slender, collarbone muted, neck slimmed all to your liking

graceful, delicate, brilliant

your hand tilting my chin up, painting my lips incarnadine before you sealed them closed—

44 Modern Language Studies 53.1

your scalpel pared my legs until my skin shone like the cracked underside of a clam shell still smooth beyond water you thinned my waist, thickened my hair, carved my nails into soft edges like snow shell and it felt like the nights the darkness condensed the moon

every night you neglected to carve me tongue or teeth

you said:

i was everything you needed but not what you wanted Galatea, Galatea you are beauty but i want love

i wondered if love was something of one’s own making until three months passed and you never once asked my name

the night i took your scalpel, i owed you mercy for the simple desire to make something of your own—

my soul desire became incarnadine and your breathing body your spoken word

my touch was soft enough to keep you sleeping my knife sharper than your gem-cut consciousness

i carved out pieces of you to fill with fool’s gold so you could shine, too

i liked the way you bled out for me and all the words that flowed red from your tongue, your tongue that i made into mine

45 emily anna king

AT FIRST HE SPOKE AS ANY OTHER CHILD HIS AGE, clutching the few words he had in his gummy fist—“mama,” “ball,” “star,”—til the evening he pointed to a motley four-legged creature dashing down the road in front of our farm, a wild look on his upturned face: “d-d-d-og.” Originally, Anna thought excitement must have caused the halting appellation, but when he tried to reference the event the very next morning, the catch, the lurch, remained: “d-d-d-og” just as before. Over time, I admit that a small part of me almost came to believe that scrawny flea-bitten scalawag which passed by our house that cold April night was an apparition, some specter sent to drag a curse across our doorstep, for after it had crossed paths with the boy, the pauses between words as well as repetitions of singular letters (and then whole phrases) began to increase—a fate which seemed much too severe a punishment to dole out to a young soul who did nothing more than stand out on the porch at dusk and try to name one thing upon the earth.

BY JENN BLAIR

Anna and I weren’t the only ones to notice William’s plight. While we were still up in Salmon River, a man in a brown bowler, who introduced himself as Rev. Swable, came to our door one afternoon to inform my wife he’d heard a seven-year-old boy in our household was suffering from “talking trouble”—news gleaned from our overly loquacious neighbor Mrs. Buxton, who’d sent him hither. Declaring himself a faith healer from Portland, Maine, the Reverend apparently boasted he aimed to visit our great Province as many times as the Apostle Paul ministered to the Ephesians, adding that he’d already met with several spectacular results on this, his second tour there, a tally which included healing two cases of gout, un-pickling an alcoholic’s liver til it lay in his body smooth as a teetotaler’s, and curing one depressive who used to stay in his bed sobbing for weeks at a time but now was up, dressed, and loudly praising God at all times, the newest tenor in his congregation’s choir.

47 poetry + fiction

Skeptical but intrigued, Anna believed it could do no harm for us all to attend one of the man’s services, so the very next evening found us attending the revival—held under a canvas tent a few kilometers inland from the Bay of Fundy. On the way there, Anna informed the boy that we were going to meet an esteemed man of the cloth who might be able to help him with his words. After singing and shouting of various (and, at times, unwieldy) stripes went on for the better part of two hours, the healing part of the service finally commenced. There at the front, Reverend Swable asked the grocer’s wife, Mrs. Orund, a woman with a noticeable limp, to come up and lean forward, then suddenly slapped her across the back, bidding her crooked spine to straighten, causing her to lose her balance and almost tumble into the dirt—her beet-colored shawl flying up almost completely over her head as her two lazy excuses for sons yanked her to her feet and the Reverend emphatically declared her healed.

As her sons shuffled the poor woman back to her seat, the good Rev. Swable beseeched the crowd to produce him more suitable candidates, and Anna bit her lip as she always did when she was uncertain, tentatively raising her hand. Upon spotting us there near the back, the Reverend’s face lit up: “Welcome! Come right down to the front! Make way, everyone, for a little child shall lead them. The Lord showed me in a vision that you’d be here tonight! Everyone, start praying that this young man’s lips be loosened to more clearly profess that beautiful name which is already in his heart, the name of our Lord Jesus Christ.” After we’d joined him on the small plywood platform, the Reverend took out a linen kerchief, bare but for a trio of letters embroidered upon it, then asked the boy if he loved God. After William nodded his assent, Reverend Swable instructed him to stick out his tongue, shouting out supplications while simultaneously grabbing the unwieldy animal in question and briskly squeezing it through the handkerchief as Anna and I tried not to wince: “Let this tongue sing your praises O Lord! Un-fork it and weave the divergent faltering, polluted streams back into one fresh river which flows mightily to the sea of your generous promises!”

“Indeed,” Reverend Swable gave the offending member one last hearty yank before finally letting go, “flows so mightily, deeply, and clearly, that others may also sail upon its bright certainty to the one true King!”

When the Reverend urged William to speak a word to the gathered crowd, he politely demurred, glancing over at his mother for help.

“Sir, maybe he’s not ready,” my wife feebly offered, “maybe there’s not yet been time for it to take.”

“Son, son. Listen here.” Completely ignoring us, Reverend Swable placed his hands on his thighs and bent down to our son’s level. “The old is gone. The new has come. Will you not let those who might need to see a miracle tonight apprehend the New

48 Modern Language Studies 53.1

Creation?” Seemingly resigned, William, who wouldn’t look at either Anna or I, stepped forward to face the crowd, both hands grimly clasped behind his back.

“P-P-Praise G-G-G-od!”

But the worst wasn’t over. For some reason he decided to start clapping, softly at first, then harder and harder, almost as if willing everyone else to clap. When he saw no one was joining, the poor boy decided he should try at least one more time.

“I s-s-said p-p-praise…p-p-praise…G-G-G-o-o-o-d!” As he clapped, a lone tear rolled down his right cheek. Anna was the first to oblige him, clapping so hard her pagoda sleeves began quivering and then I joined in too while glancing over at the “reverend” in question—my pointed look assuring him I would strangle his throat if he didn’t also start pumping his useless lily white too thin to hold a rake or hoe or any other honest implement hands; upon seeing my fierce look, the despicable charlatan also began applauding til all the people gathered out front began miserably clapping along, everyone faintly thanking the Lord for His mysterious ways, ways so inscrutable as to possibly include humiliating an innocent child.

Anna and William had already scurried away, the crowd mostly dispersed, when I took my chance to address the fraud directly: “Tonight you made my flesh a sideshow. If I ever see you around here again, I’ll shout your sins all day long then come find you with my rifle and swiftly endow you, right between those two good-for-nothing legs, with the most dazzling opportunity to be healed. Understand?”

After I’d spoken my piece, I forced myself to behave as Anna would want and made myself walk away before he could even reply. Drawing nearer our wagon, I heard the boy asking his mother through sobs why God hadn’t healed him—what was wrong with him—even as she dabbed at his tear-stained cheeks: “oh my love,” telling him that there might yet be a cure: remember, Jesus spent forty days and nights in the wilderness being tempted, undergoing hardship only to be refined for a nobler purpose. I stood back til she had finished. Anna was eternally patient whereas I continually struggled with outbursts born of anger, and though I never could have admitted it out loud, the same flashes of temper which used to cause my mother to put her finger up to her lips: shhhh—though we were both already silent, bracing ourselves as the doorframe began to rattle—my father coming home late again, most likely with an over-sweet stench on his breath. The three of us were so miserable that particular evening that no one ventured to say another word the whole ride home.

Though I felt sympathy for William’s predicament, I admit there were times I also felt ashamed. Ever since I’d arrived in New Brunswick from Belfast, I’d worked hard to shave off the roughest edges of my own syllables, but whenever the boy spoke, his unwieldy, faltering words clung to sides of the air and remained; burred, stubborn thistle which stuck out past any hope of fitting in. But Anna never gave up. After we’d moved south to Eau Claire (lured there by an old neighbor who’d promised there was

49 poetry + fiction

decent work to be had in the many sawmills along the banks of the Chippewa), she kept doing everything she could to find a cure: tinctures and tonics laced with soothing peppermint and some foul-smelling rum-colored liquorice lozenges she had William suck on shortly before reading his primer out loud. The year William turned nine, she took him to an expensive physician, known in the area for attending to several of the families of the biggest lumber barons, only to find the esteemed doctor had nothing more innovative to suggest than squirting lemon then placing a few granules of cayenne pepper right on the tongue, stinging then shocking it into obedience. A preacher at a Lutheran church we attended a short while had other ideas about what was ailing our son, confidently blaming the demon of self-pleasure and telling us to look in on the boy at night as he slept: were both hands still resting above the coverlet? Riding home after the service, Anna looked over at me, indignant, and I just shook my head, relieved that, despite her great piety, she’d found the theory almost as ridiculous as I. While Anna consented to try almost any snake oil any peddler was proffering, I continued to hold out hopes for a cure a bit more scientifically informed, and thought I’d actually come into possession of one shortly after I’d been promoted to foreman at the mill, the November morning one of the company’s main investors sent a New Englander for a firsthand tour. My own supervisor (Andreas), clearly irritated by the ongoing parade of visitors the company had been sending lately, asked me to show the guest (one Daniel Uber) around in his stead. Clearly of means, this Mr. Uber was also quite affable—and we found ourselves freely chatting as I took him on a tour around the grounds and holding ponds. When my twelve year old’s predicament happened to come up, my charge, almost dandyish in a raisin-colored frock coat, briefly threw up his hands before excitedly telling me about a surgery his oldest niece Abigail had recently undergone back in Boston, still a somewhat controversial procedure, but one already returning “some very promising results, indeed. And Abigail, I….well, she’s a new girl almost! So much more confident, and, I believe, for the first time, happy. ”

After Mr. Uber had gone, I mused over his account all the rest of the afternoon, still pondering it while inspecting several piles of wood recently set aside to air-dry and helping a pair of especially jovial Norwegian twins, Lucas and Karl, strip some extra stubborn bark off a pile of pine logs our company had floated down the Black River Valley a few days before—and by the time I arrived home that evening, I admit that the prospect had all but seized hold of me. An exacting cut, cruel but quick, might very well make the words roll off our boy’s tongue smooth as cream. It would not be cheap but perhaps I could work some extra shifts at the mill. Mr. Uber had told me the name of the surgeon and even insisted on taking down my details that he might telegraph some more information in time. I think it had struck us both that our crossing paths, he with his answer and I with my question, had something almost providential about it. As I schemed, I fondly began imagining the procedure to be the rough equivalent

50 Modern Language Studies 53.1

of the famous contractor William Dargan cutting through the bends in the River Lagan in Belfast, letting out the seams of water far enough that the grandest ships could finally come into port then sail all the way back out to the North Channel and the Atlantic.

But when Mr. Uber actually remembered to send on the details as he had promised, his dutiful following through emboldening me enough to finally make my case out loud, Anna barely listened. Unimpressed by news of the pioneering German surgeon who’d recently diverted his attention from muscles in the human eyeball to those in the tongue—(attacking them, yes, but only to prevent future spasms!)—she told me, “No John, absolutely not” outright, before proceeding to inform me that the very same night we’d encountered the false prophet in a bowler hat she’d taken a solemn vow that no one would ever physically lay hands on our boy again. God was a God of unlimited might and power and He, through his emissary and ambassador the great Holy Spirit, had, more than once, proven he could work through other means. Was it not unholy anger, despair, and even outright disdain of heaven which led Moses to strike the rock? She was sorry, truly, but she could not hear of it. Though I sulked for a while, I eventually bowed to her wishes. Consequently, the boy’s tongue remained whole and un-sliced, a sorry lump of meat in his mouth that did not work.

As the years passed, we always tried to help William as best we could, busy as life was with our three boys. Though our second son, Thomas, arrived less than two years after William did, the two boys never seemed that close. When our third son, John, came along five years later, however, Thomas almost flew to his side, relieved, the pair eventually becoming so conjoined later in life that they often were mistaken for twins. They not only mirrored each other physically (having inherited my compact frame, shorter stature, and barrel chest), but also turned out to be much alike in temperament. Possessed of a loud and boisterous nature and scared of nothing, they laughed loudly and often while pulling endless, good-natured pranks. William, by contrast, was not only quieter than them but much bigger—and taller—blessed or cursed to possess an almost gargantuan stature that made any blushing, stammering, or hesitancy on his part stand out even more. His size left him nowhere to hide. Boys and girls his age weren’t cruel to him insofar as they ignored him, which, Anna once remarked, was its own kind of cruelty. In lieu of true companions, he spent a great deal of time outside in the fields and stables and grew especially skilled at carving animals, boats, and other shapes out of whatever pine scraps I could manage to bring home from the mill with an old silver-gilt whittling knife that used to belong to Anna’s father. In school his teachers usually allowed him to write out any speeches he must give then have a kind or irritated classmate read them on the appointed day, grading him on composition rather than elocution, and he wrote many thoughtful pieces Anna was proud to save. The same went for memorizing scripture in Sunday school. He earned his leather Bible and framed certificate with all the rest, not through recitation but sitting at a table out

51 poetry + fiction

in the vestibule and scribbling the verses from memory to prove they were etched on his heart. But what would become of him after there were no more kind petticoats or sympathetic schoolmarms to issue special allowances, we did not know.

The year our youngest, John, turned four, Anna began feeling distinctly unwell, complaining she was even more weary than a ramshackle farm and three active boys allowed for, but we did not think about the most likely culprit quite as quickly as we should have, believing that time long past. When we began sharing our surprising news, our neighbor Mrs. Sutter remarked, “Ah, you’ll have your girl now” with a knowing nod, but if that was Anna’s secret hope, she was too circumspect to admit it, only allowing that “a healthy child is all we pray for.” Though the nine months passed fairly uneventfully, the actual laboring part was a beastly affair that stretched out over two and a half days, almost as if my wife’s poor body had forgotten how to do what it had managed so easily thrice before. Some of those sounds she made. They will never leave my mind. When the red squalling creature was finally out, the creature spared no pains letting us know of her rage and displeasure, as my exhausted wife stared at the wall, eyes dulled, mouth turned downward.

After the midwife cut the tiny devil’s cord and swabbed out its throat, she quickly turned her attention back to Anna, tasking me with taking anger incarnate out into the front sitting room where its fury continued. I stared at the possible changeling in despair until William, who must have been silently watching all that time, came over and reached out his arms. As soon he nestled the small, indignant bundle against his bosom, there was quiet. Only quiet. Initially, one might dismiss the sudden change as mere coincidence, but over time, their enduring bond became apparent, despite the fact William was a boy, Anna a girl, and a chasm of twelve years lay between them. As the years passed, my wife increasingly relied on our firstborn to assist her with our last, a predilection which led me to warn her one evening, “Let us not geld him completely,” advice which didn’t fall upon an especially receptive ear: “I’m not as young as I once was, John. I don’t think you understand how much I need his help.”