It can be said without hesitation that Edward Steichen, the world-famous Luxembourgborn American photographer, nally receives the attention he deserves in the country of his birth. While the National Museum of History and Art (MNHA) permanently dedicates a space to his work, the monumental Family of Man exhibition, orchestrated by Steichen as director of MoMA’s Department of Photography, is presented in specially designed rooms at Clervaux Castle that are open to the public throughout the year.

However, this was not always the case since Steichen’s Family of Man and The Bitter Years exhibitions rst reached Luxembourg in the 1960s, and the generous bequest of his own prints by his estate arrived in 1985. Indeed, it was not until the mid-1990s that a sustained interest in the cultural and art historical value of Steichen’s oeuvre awoke in Luxembourg.

With the publication of the present catalog of the 178 photographs bequeathed in 1985, a long-lasting project has come to a successful end. In preparation for the catalog, all the prints were rst meticulously cleaned and, where necessary, carefully restored. It was clear from the outset that this outstanding collection, both in terms of quality and quantity, could only be adequately studied in a collaborative e ort. The photographs held at the MNHA cover almost all aspects of Edward Steichen’s oeuvre, from the pictorialist images of his early years to fashion, advertising, landscape, and family photographs. Moreover, it was obvious that the project could not only focus on the content of the images, but also had to deal with questions regarding the prints’ dating and techniques as well as their conserva tion and preservation. Special attention was also given to the collection’s provenance, its history over the years, and how the Luxembourg bequest compares to those made at the same time to institutions in and outside the United States.

Through this monograph, the MNHA is also ful lling a long outstanding debt to both Edward Steichen himself and his estate. Each photograph of the bequest is accompanied by a text as well as the transcription of all inscriptions, allowing both professionals and photography enthusiasts to discover this outstanding collection in all its detail.

The editors would like to express their sincere gratitude to the authors and all other in dividuals and institutions involved in this long-running project, for their enthusiasm and patience. We would also like to express our special thanks to Silvana Editoriale for their friendly collaboration and attentive editorial support.

May the present catalog further strengthen Edward Steichen’s artistic legacy in his native Luxembourg and abroad.

Michel Polfer Gilles Zeimet

11 The Steichen Prints of the National Museum of History and Art Luxembourg Provenance and Reception of an Extraordinary Collection Michel Polfer

25 The Identi cation, Conservation, and Preservation of the Photographs for the MNHA’s Edward Steichen Collection: A Unique Project Kerstin Bartels

41 The MNHA Bequest in Relation to Other Steichen Bequests Around the World: Number, Origin, and Subjects Malgorzata Nowara

49 The Prints from the MNHA’s Steichen Bequest: Techniques, Dating, and Inscriptions Malgorzata Nowara

55 Edward Steichen: The “Lëtzebuerger Jong” who Brought Modernism to the New World Gerd Hurm

69 At Home in the Museum: Edward Steichen’s Family Photographs at the National Museum of History and Art Françoise Poos

CATALOG

Julia Niewind & Gilles Zeimet

79 Introduction 83 01 -- Early Landscapes 93 02 -- Rodin’s Balzac 99 03 -- Family 155 04 -- Portraits 335 05 -- Nudes 343 06 -- Theater 363 07 -- Advertising & Fashion 387 08 -- Experiments 401 09 -- Nature 423 10 -- Color 453 11 -- Other Photographers

460 Reference Literature

CONTENTS

MICHEL POLFER

THE STEICHEN PRINTS OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HISTORY AND ART LUXEMBOURG PROVENANCE AND RECEPTION OF AN EXTRAORDINARY COLLECTION

Introduction

This is not the place to trace in detail the life and career of Edouard (Edward) Steichen, who was born on March 27, 1879 in the Luxembourg village of Bivange, emigrated with his parents to Hancock (Michigan) in the United States at the tender age of almost two, and became a naturalized US citizen there in 1900.1 Steichen indeed left behind an ex traordinarily multifaceted artistic life’s work, not only as a photographer but also, among other things, as a “camera avant-gardist and plant grower, war reporter and children’s book illustrator, fashion photographer and museum director, ecologist and conceptual artist, textile designer and exhibition curator,” to quote his 2019 biographer, Gerd Hurm.2

Just as complex as his life’s work was Steichen’s lifelong close relationship with Luxembourg.3 His attitude toward his country of origin remained complex and was, in the course of his life, rather changeable; the often quoted greeting of the 84-year-old Steichen “Ech sin e Lëtzebuerger Jong”4 (I am a Luxembourgish boy) at a reception for Grand Duchess Charlotte given at the White House by President John F. Kennedy in 1963 re ects only one side of this. In fact, Steichen’s attitude toward Luxembourg had by no means always been so clearly positive. In his autobiography A Life in Photography, 5 also published in 1963, he mentions his Luxembourgish roots only once and rather casually, as the birthplace of his mother.6

It was thus by no means preordained that the last surviving original versions of the two most important exhibitions Steichen curated at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), namely The Family of Man and The Bitter Years, would be donated, during his lifetime and at his own instigation, to the country of his birth.

Neither was it to be expected that in 1985 the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg would receive from Steichen’s estate a signi cant body of his own works, which have since become part of the collections of the Musée national d’histoire et d’art Luxembourg (MNHA).7

The Family of Man and The Bitter Years have since long continued to be the object of schol arly interest, both in terms of the history of their creation and impact as well as in terms of the circumstances of their donation to Luxembourg and their development ever since.8

In contrast, the prints in the MNHA’s collections have so far received little attention. This is all the more surprising since they represent arguably the most important holding of photographs by Edward Steichen in Luxembourg and beyond.9

Changing this situation is one of the main concerns of the present inventory catalog. The focus of our contribution will initially be on the history of the donation itself, which has not been addressed by research to date. Indeed, the circumstances surrounding the dona tion appear to be relevant from today’s perspective not only in terms of the direct history of the collection, but also in terms of cultural history, since they shed light on the cultural context in which Edward Steichen’s photographs arrived in Luxembourg in the 1980s.

Finally, we will brie y analyze the history of the collection’s impact in and outside the museum.

11

In 1985, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg received – rather unexpectedly for those implicated on the Luxembourg side – an important bequest by Edward Steichen consisting of 178 prints.

In addition to 175 photographs by Steichen himself, the ensemble also includes three prints by close collaborators: one photo by Dorothea Lange (1895–1965)10 and two pho tos by Wayne F. Miller (1918–2013).11 The presence of these three photographs in the collection is by no means coincidental. All three are directly related to the photographer, depicting his second wife Dana Desboro Glover (1894–1957)12 and Steichen himself with his close friend and brother-in-law Carl Sandburg (1878–1967).13

This collection, which can be classi ed as exceptional in many regards, has supplement ed, since 1985, the two major exhibitions curated by Steichen and staged in Luxembourg since the 1960s. The fact that the artist was so generous to the country of his birth demonstrates that his changeable attitude toward Luxembourg took a positive turn in the last phase of his life.

Fig. 1

Steichen visiting the Luxembourgish painter Michel Sto el during his second trip to Luxembourg in November 1952

Fig. 2

Opening of the 1963 exhibition Edward Steichen Photographe at the MNHA

The relationship had been strained ever since Steichen’s second trip to Luxembourg in November 1952 (Fig. 1), which he saw as a catastrophe and – rightly – as a humiliation.14 The visit of the by then world-famous photographer was largely met with indi erence in the country of his birth. Furthermore, he was unable to nd any Luxembourgish photographer interested in collaborating on his exhibition project The Family of Man, which was in the making at the time. Worse still, his plan to organize the rst European leg of the future exhibition in the country of his birth had met with complete disinterest, even rejection, from those in charge, including those at the MNHA.

The starting point for the gradual rapprochement and reconciliation, or at least the rst expression of a turn for the better, was undoubtedly Steichen’s direct meeting with Grand Duchess Charlotte in 1963 we mentioned earlier.15 Beyond this rst encounter, however, further positive factors and concrete experiences were to consolidate this development by the time of Steichen’s death in 1973.

After the disastrous trip of 1952, word had spread, even in the still culturally very provin cial Grand Duchy, of Steichen’s international reputation as well as the ground-breaking worldwide success of his traveling exhibition The Family of Man. An important role in this was played by the journalist Rosch Krieps and a small circle of like-minded people, who tirelessly campaigned for the recognition of Steichen’s work.16

Thus, from August 10 to 25, 1963, as part of the 1000th anniversary of the City of Luxembourg, the rst Steichen exhibition ever to be held in the Grand Duchy took place at the MNHA. Under the title Edward Steichen Photographe, it displayed 163 photos from the ret rospective presented at MoMA in March 1961 on the occasion of the artist’s 82nd birthday. They were seen by a total of 3,252 visitors (Fig. 2).17 The traveling exhibition had actually

been reserved for other venues until 1965, but it was made possible – in part due to the in uence of the US ambassador William R. Rivkin – to interpose Luxembourg as a stage.18

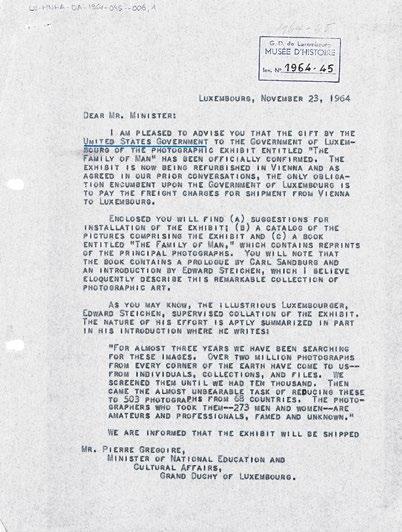

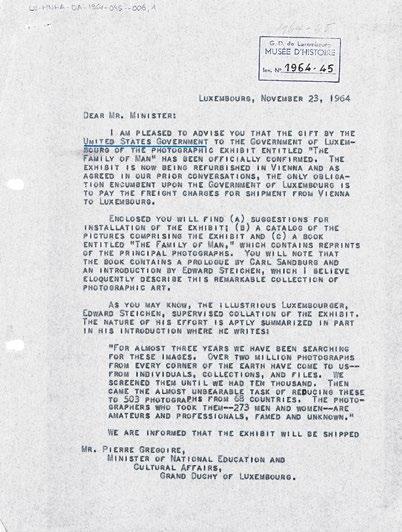

One year later, on November 23, 1964, US ambassador William R. Rivkin informed Luxem bourg’s Minister of Culture, Pierre Grégoire, that the US government had just agreed to donate the last complete “traveling version” of The Family of Man (Fig. 3)19 to Luxembourg, no doubt at Steichen’s own suggestion.

However, The Family of Man was not to arrive in Luxembourg until June 1965, after it had made a last, unplanned stopover in the former Abbey of St. Peter in Bruges.20 Its rst exhibition took place from July 9 to August 15, 1965 in the rooms of the MNHA.21

The terrain was thus prepared for Steichen’s nal, far more pleasant and successful trip to Luxembourg in July 1966. This time, he was accompanied by his third wife, Joanna Taub Steichen, at the invitation of the Luxembourg government.22 The occasion was Steichen’s award of the prestigious Grand O cer’s Cross of the Luxembourg Order of Merit by the Minister of Culture, Pierre Grégoire, in the rooms of the MNHA (Fig. 4).23 To mark the occasion, a selection of pictures from The Family of Man was once again presented in the museum’s foyer from July 23 to September 10. Although part of the permanent exhibition had been cleared out especially for this purpose, visitors had to satisfy themselves with a greatly shortened version, as it had been the year before, due to lack of space.24

Steichen’s last trip to Luxembourg was a veritable triumph. The couple was received by the Minister of Culture, Pierre Grégoire, and in a private audience by the young Grand Duke Jean. They visited, among other places, his birthplace in Bivange, the American military

12 13 The donation of

1985

Fig. 3 Letter from US ambassador William R. Rivkin to Minister of Culture Pierre Grégoire, November 23, 1964 (MNHA Archives, LU-MNHA-DA-1964-045--006)

CATALOG INTRODUCTION

The photographs of the MNHA’s Edward Steichen bequest are grouped into 11 categories which, however, partially overlap. Although a number of family photographs, for example, are color photographs, they are not presented alongside the other color photographs, but with the family photographs as in this case a grouping according to subject matter was deemed more comprehensible than one based on chromaticity. Overall, the photographs were arranged in such a way that they best illustrate almost the entire span of Steichen’s life and career. Inside the di erent categories, the photographs are ordered chronologi cally unless speci ed otherwise.

The 11 categories present themselves as follows:

1. EARLY LANDSCAPES

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Edward Steichen undertook experiments in landscape photography in natural light, in the United States as well as in Europe. A good number of them were taken under the moonlight.

2. RODIN’S BALZAC

Over the course of several nights, Steichen elaborately photographed the sculpture of Honoré de Balzac created by his friend Auguste Rodin. Steichen mentions the creation process of the photographs at length in his autobiography. As they do not only occupy a unique position within Steichen’s oeuvre, but also largely contributed to the wider recog nition of the much contested sculpture, the two photographs form their own category.

3. FAMILY PHOTOGRAPHS

The majority of the pictures in this category were created in a private setting. Most of them are reminiscent of snapshots rather than staged photographs. The photographs are not arranged in strict chronological order but loosely grouped according to the di erent family members (Steichen’s mother and father, his sister, his children, etc.).

4. PORTRAITS

The portraits Steichen created form by far the largest category. They provide a compre hensive overview of Steichen’s portrait photography – from his pictorialist beginnings in the early twentieth century to his work for Condé Nast in the 1920s and 1930s.

5. NUDES

The MNHA’s Steichen collection includes a total of three nudes. Two of them were creat ed in the early twentieth century, the third dates from the 1930s.

79

6. THEATER

For Condé Nast, among others, Steichen created not only portraits of famous actors, mu sicians, writers, and politicians, but also photographed entire or partial casts of theater plays, who improvised scenes in front of his camera.

7. NATURE

Throughout his entire career, Steichen’s oeuvre was in uenced by nature in one way or another. Flowers stood at the heart of his interest. He bred delphinia from about 1910 until the end of his life and presented the success of this endeavor in 1936 in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Time and again, Steichen photographed, over the course of several decades, sun owers in di erent growth stages. The category also includes a number of pictures from Steichen’s shadblow tree series. Toward the end of his life, Steichen repeatedly photographed the tree that was growing on his estate in Connecticut.

8. ADVERTISING

From the early 1920s until the late 1930s, Steichen created photographs for numerous advertising campaigns for a variety of products. In fact, he was one of the very rst pho tographers working for advertising agencies. The photographs are grouped according to the products they advertise and ordered chronologically inside those subcategories.

9. EXPERIMENTS AND OBJECTS

The works in this category date from the 1920s and 1930s and are the result of a vari ety of more experimental interests Steichen explored in terms of montage, lighting, and subjects.

10. COLOR

This category contains not only color photographs Steichen created on a trip to Mexico using for the rst time a compact camera together with color lm, but also the di erent color stages of a photograph of Chinese dancers that, when combined, form a color photograph.

11. OTHER PHOTOGRAPHERS

The MNHA’s Steichen bequest also holds three photographs that were taken not by Steichen himself but by fellow photographers and long-time friends Dorothea Lange and Wayne F. Miller.

For each of the 178 photographs that form the MNHA’s Steichen bequest, the following information was compiled:

1. Title

The titles are either taken from the standard literature on Steichen or are based on in scriptions found on the photographs.

2. Dating

When dating photographic prints, one must distinguish between the date the photograph was taken and the date the print was created. The dates on which the di erent photo graphs were taken could nearly all be determined either through research in the relevant literature and Condé Nast publications or via the inscriptions on the prints. The dating of the prints is based on the analyses carried out by the photo restorers Kerstin Bartels and Anna Jüster (see their article in this publication).

3. Catalog text

The catalog texts provide detailed information about the represented subjects and people as well as information regarding the context of the photographs’ creation.

4. Techniques

The indicated techniques are based on the analyses carried out by the photo restorers Kerstin Bartels and Anna Jüster (see their article in this publication).

5. Location

When known, the locations on which the di erent photographs were taken is indicated.

6. Dimensions

The dimensions of the prints are indicated in centimeters (height by width).

7. Publications

Only the publications Steichen was directly involved with (such as Camera Work and his autobiography) and those for which the photographs were created are listed.

8. Numbering

Before reaching the MNHA, the photographs of the Steichen bequest were kept at the George Eastman House – International Museum of Photography and Film, where each was given an IMPST (International Museum Photography Steichen?) number. Therefore, the inventory number of both the George Eastman House and the MNHA are indicated for each photograph.

9. Inscriptions

The inscriptions on the front of the photographs – such as titles, dates, and publication names – were actually written on the negatives and consequently appear on each print made from them. Unless speci ed otherwise, the inscriptions on the back were written in pencil. All the inscriptions were transcribed whenever possible. When inscriptions could not be meaningfully transcribed, as in the case of indications linked to the development process of the print, a detailed image of the inscription is provided.

The authors would like to thank Dana Strohscheer for meticulously identifying the publications where the photographs of the MNHA Steichen bequest were published or for which they were created, Aliénor Vidali and Marie van Boxel for their editorial support, Edurne Kugeler for her management of the archival documents kept at the MNHA, Tom Lucas for creating high quality digital reproductions of the MNHA Steichen prints, as well as Muriel Prieur, Patrick Quinteira, and Deborah Velazquez for their logistical support and object handling.

80 81

BALZAC – THE OPEN SKY

19081

Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) was a French novelist, playwright, critic, and journalist. He is regarded as one of the founders of Realism in European liter ature. La Comédie humaine (The Human Comedy), a multi-volume collection of more than 80 novels and novellas depicting a panoramic portrait of French society, is considered his masterpiece.2

In 1898, the French sculptor Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) completed his Monument to Balzac in bronze. The sculpture was not so much a portrait, but a powerful evocation of a visionary genius, of the inspired creator draped in the monk’s habit Balzac used to wear when writing. The innovative, ex pressive monument was attacked by critics, some even called it a “mon strosity.” Yet, Edward Steichen was an admirer of the sculpture from the rst time he saw a picture of it in a Milwaukee newspaper, and the prospect of seeing it drew him to Paris in 1900. Following the controversy around his Balzac, Rodin had been barred from the World’s Fair. Thus, he organized a very successful counter-exhibition in the Pavillon d’Alma, which Steichen saw in the summer of 1900. Steichen stayed in Paris until 1902, became friends with Rodin and often visited him in his studio in Meudon. In October 1908, Rodin invited Steichen back to Meudon to photograph his Balzac The sculp ture was mounted on a revolving platform Rodin had designed speci cally for the occasion. After studying the sculpture by day, Steichen decided – to Rodin’s delight – to photograph the Balzac at night. For two nights, he pho tographed the Balzac in the moonlight.3 Rodin told Steichen, “You will make the world understand my Balzac through these pictures.”4 The Balzac series was shown in Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery 291 in New York in April–May 1909, before being published in Camera Work 5

For more information on Auguste Rodin and his Monument to Balzac see Cat. 6.

Date (print) after 1953

Technique gelatin silver print, probably toned

Location Meudon, France

Dimensions 35.5 × 27.7 cm

MNHA inv. no. 1985-030/001

IMPST no. 2004

Published Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly no. 34–35, 1911, p. 11.

Edward Steichen, A Life in Photography, 1963, pl. 53.

Inscriptions (front) STEICHEN MDCCCCIX

Inscriptions (back) 1985-30/1

GRAND-DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG – MUSÉES DE L’ÉTAT [stamp, blue ink]

2004 Rodins Balzac by moonlight 1908

Best print [underlined]

try × 14 × 17 like this adding a letter more [underlined] exp – of lter [?] / 0 [underlined]

2004 1 Niven 1997, pp. 290–93.

2 https://www.britannica.com/biography/Honore-de-Balzac [retrieved November 23, 2021].

3 Niven 1997, pp. 290–91.

4 Niven 1997, p. 291.

5 Niven 1997, p. 292.

94 95 02 R ODIN ’ S B ALZAC Cat. 5

MY LITTLE SISTER WITH THE ROSE-COVERED HAT

18991

Edward Steichen’s younger sister Lilian was the rst Steichen born in the United States. The family had settled in Hancock, Michigan, when Lilian was born in 1883. Shortly afterwards, they moved to Milwaukee and their moth er Marie Kemp Steichen opened her milliner’s studio and shop. In this early portrait, Lilian is wearing a hat her mother made. Marie Kemp Steichen had bought a hundred boxes of arti cial roses for a bargain. The hats she deco rated with those owers were advertised with posters her son Edward de signed and by her daughter Lilian, who wore the hats to church on Sundays. Soon, the rose-covered hats could be seen all over town. Edward Steichen documented his mother’s successful design and marketing campaign with this photograph of his sister.2

Lilian Steichen was a non-conformist her entire life. She was very intelligent, loved poetry, and wanted to be a poet herself. Against the will of her par ents, she applied for a convent school in Canada to nish high school. The Steichens would have preferred her working in her mother’s store after n ishing eight years of school, but nally, they agreed to let her enroll at the convent school. Lilian studied fteen subjects, including mathematics, sci ence, German, Latin, and French.3

Yet, while at school, Lilian began struggling with religion. After a year, she left the convent school and also gave up her Catholic faith, much to the dislike of her parents. In the summer of 1900, Lilian, despite not having nished high school, prepared herself for university. She read the required textbooks and taught herself advanced algebra as well as geometry.4 She was accepted to university in September 1900 and received her bachelor’s degree in philoso phy from the University of Chicago in December 1903.5 In 1904, she accepted a position as a Latin teacher and librarian at a school in North Dakota – far away from her parents, who lived in Milwaukee, and from her brother who was staying in New York.6 In 1906, she moved back to live near her par ents and found work at a high school in Princeton, Illinois, where she taught English and Latin.7 In a letter to her later husband Carl Sandburg, she de scribed her non-conformist life in Princeton: “Princeton doesn’t mind – they accept me as am. Put me down as ‘peculiar’ of course . . . I walk the streets hatless most of the time . don’t go to church Sundays . . . I talk Socialism and radicalism generally, whenever I get the chance – that doesn’t disturb Princeton either.”8

For more information on Lilian Steichen, see Cat. 8.

Date (print) after 1953

Technique gelatin silver print (mounted on cardboard) Location Milwaukee (Wisconsin), United States Dimensions 21.5 × 26.5 cm MNHA inv. no. 1985-030/022 IMPST no. 2050

Published Edward Steichen, A Life in Photography 1963, pl. 6.

Inscriptions (front) 62

Inscriptions (back) 2 [encircled] My Little Sister 1899 1985-30/22 GRAND-DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG –MUSÉES DE L’ÉTAT [stamp, blue ink] 2050 6 Book Print OK. but a wee [underlined] bit lighter. # 49 a [encircled] 4 × 5 neg, straight print

Stain on left cheek removed by cyanizing locally with fur brush + retouching with Spotone with the Rose-covered Hat Platinum Print

My Little Sister (Lillian Steichen, now Mrs. Carl Sandburg) 1899 2050

1 Steichen 1963, pl. 6.

2 Niven 1997, pp. 45–46.

3 Niven 1997, pp. 51–55.

4 Niven 1997, p. 67.

5 Niven 1997, p. 178.

6 Niven 1997, p. 186.

7 Niven 1997, p. 216.

8 Niven 1997, p. 272.

100 101 03 FAMILY Cat. 7

GEORGE FREDERIC WATTS

1900

When the young Edward Steichen got the commission to photograph sym bolist painter and sculptor George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) in 1900, the sitter was 83 years old and had been a noted artist for almost 60 years. Born in London as the son of a piano maker, he joined the Royal Academy at the age of 18 and had his rst exhibition two years later. In 1843, Watts won First Prize in a competition to design murals for the newly built Houses of Parliament. Although his designs were never realized, the prize money ena bled him to visit Italy. He traveled to Florence, Rome, and Naples from 1843 to 1847, drawing inspiration from Italian Renaissance masters such as Giotto, Michelangelo, and – most obvious in his work – Titian. When he returned to England, he became famous for his symbolist, allegorical paintings and his portraits of famous contemporaries, although publicly declaring that he despised portraiture. Watts received many honors in his lifetime: in 1867, he was elected as an Academician to the Royal Academy and was one of the original members of the Order of Merit, established in 1902 by King Edward VII. Several years earlier, he twice refused to be ennobled by Queen Victoria. Watts donated most of his works to the Tate Gallery and the National Portrait Gallery in London.2

Edward Steichen was commissioned to photograph Watts after he had pre sented some of his photographs in the exhibition The New American School of Photography in London, which caused a stir because the medium had not yet been accepted as a legitimate art form at the time. Steichen had come to Europe to photograph great artists, thus proving that photographic portraits were just as much a form of art as paintings.3 The composition of the two portraits of George Frederic Watts (Cat. 34 and Cat. 35), taken in one sitting, is clearly in uenced by Titian’s late self-portraits, today at the Prado in Madrid and the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin. Like Titian, Watts has a long, white beard, wears a black cap, and is depicted in pro le. Watts’s name on the portrait, written across the top, is also reminiscent of Renaissance portraiture. Nothing in Titian’s self-portraits nor in Steichen’s photographic portraits of Watts refers to the artists’ occupation. None of the works hides the physical e ects of old age – in fact, these are even emphasized by Steichen’s pictorialist style.

Date (print) after 1953

Technique gelatin silver print

Location London, United Kingdom Dimensions 35.5 × 27.8 cm MNHA inv. no. 1985-030/103 IMPST no. 2377

Published Edward Steichen, A Life in Photography, 1963, pl. 13.

Inscriptions (front) GEORGE FREDRICK WATTS STEICHEN MDCCCCCIII

Inscriptions (back) 1985-30/103 GRAND-DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG – MUSÉES DE L’ÉTAT [stamp, blue ink] 2377 2377

1 Niven 1997, p. 87.

2 https://www.britannica.com/biography/George-Frederick-Watts [retrieved August 7, 2021].

3 Niven 1997, p. 87; Steichen 1963, chap. 2.

156 04 PORTRAITS Cat. 34

THE LITTLE MODEL1

c. 19022

Edward Steichen remembers producing his rst nude studies in his autobi ography: “I did a number of nude gures in Paris ... In none of these gures is the face visible. For many years everyone had prejudices against posing in the nude, and even professional models usually insisted, when they posed for nude pictures, that their faces not be shown.”3

The model in the picture awkwardly leans towards a wall, hiding her face. Next to her on the oor stands a vase with a few branches.

In 1902, Steichen was interviewed by art critic Sadakichi Hartman in his stu dio in New York. During their conversation, Steichen mentioned that nobody seemed to understand his nudes. Hartman, whose “whole life has been a ght for the nude, for liberty of thought in literature and art,” described Steichen’s nudes in his article “A Visit to Steichen’s Studio,” published in Camera Work: “a strange procession of female forms, naïve, non-moral, almost sexless, with shy, furtive movements ... assuming attitudes commonplace enough, but imbued with some mystic meaning ... absolutely incomprehensible to the crowd.”4 Hartman, while being impressed with Steichen’s body of work, thought his nudes to be inferior to his other photographs.5

This and other nude studies were taken around 1902, when Steichen lived in Paris.

Date (print) after 1953

Technique gelatin silver print

Location Paris, France

Dimensions 35.3 × 27.7 cm

MNHA inv. no. 1985-030/114 IMPST no. 2409

Published Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly no. 14, 1906, pl. VI [mirrored].

Inscriptions (back) 1985-30/114

GRAND-DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG –MUSÉES DE L’ÉTAT [stamp, blue ink] 2409 2409

1 Camera Work: A Photographic Quarterly, no. 14, 1906, pl. VI.

2 Likely taken around the same time as other nudes dated 1902 and pub lished in Steichen’s autobiography.

3 Steichen 1963, chap. 2.

4 Niven 1997, pp. 153–54.

5 Niven 1997, p. 154.

336 337 05 NUDES Cat. 123

ADVERTISEMENT FOR JERGENS LOTION

mid- to late 1920s

The Andrew Jergens Company was founded in 1882 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Originally called the Jergens Soap Company, they expanded to the produc tion of beauty and cosmetic products in the early twentieth century. In 1922, they hired the J. Walter Thompson Company (JWT), a New York advertising agency, to market the local company nationwide. The Jergens Company’s sales were not great and a market analysis by JWT concluded that to con sumers, Jergens was indistinguishable from its competitors. Consequently, it was decided to change not only the old-fashioned packaging and label, but also the formula of their lotion. An innovative marketing strategy was developed: the product was to be promoted as a lotion speci cally for hands and Steichen was hired as the photographer for the advertising campaign.2 Together with art director Gordon Aymar, Steichen worked on Jergens ad vertising campaigns from 1923 to 1930, producing ve to ten advertisements each year.3 The Jergens advertisements were placed in magazines such as Ladies’ Home Journal, Women’s Home Companion, and Good House Keeping almost every month, but also appeared frequently in Art Directors’ Annual (also called Annual of Advertising Art).4

In the early years the Jergens advertisements featured photographs of wom en’s working hands, performing housekeeping tasks such as sewing, garden ing, kneading dough, or peeling potatoes. They were accompanied by a text explaining that Jergens Lotion keeps hard-working hands soft and beautiful and by a coupon for a free sample.5 The hand model for some of the pictures was Helen Lansdowne Resor, the wife of JWT’s chairman, and a very suc cessful copywriter herself. In his autobiography, Steichen recalls photograph ing her hands peeling potatoes: she “posed for the hands, and I could tell by the way she cut the potatoes that this wasn’t the rst time she had done it.”6 It is currently not known for which exact advertising campaign the MNHA photograph was used.

For more information on Jergens Lotion, see Cat. 136 and 137.

Date (print) probably 1930s

Technique gelatin silver print

Location unknown

Dimensions 20.3 × 25.4 cm

MNHA inv. no. 1985-030/112

IMPST no. 2407

Inscriptions (front) 3

Inscriptions (back) 1985-30/112

GRAND-DUCHÉ DE LUXEMBOURG – MUSÉES DE L’ÉTAT [stamp, blue ink] 2407 2407

1 https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/ nmah_1415208 [retrieved June 13, 2021].

2 Johnston 1997, p.47.

3 In 1930, Gordon Aymar was replaced by art directors Elwood Whitney and James Yates (Johnston 1997, p. 140).

4 Johnston 1997, pp. 259–80.

5 Johnston 1997, pp. 47–57.

6 Steichen 1963, chap. 9.

364 365 07 A DVERTISING & F ASHION Cat. 135