Editor: John J. Han

Assistant Editor: Dylan Chastain

Editorial Consultant: C. Clark Triplett

Cover Design: Terrie Jacks, Aurora McCandless

Webmaster: Jenna Gulick

The Right Words is a semiannual online magazine of nonfiction published by the Department of English at Missouri Baptist University, One College Park Dr., St. Louis, MO 63141. Nonfiction encompasses a broad range of literary works based primarily on fact, including essays, biographies, memoirs, documentaries, book reviews, movie reviews, travel stories, photo essays, and aphorisms. Interested students, faculty, and friends of the Department who support the university’s mission may submit previously unpublished works of nonfiction to john.han@mobap.edu for consideration.

For the April issue, we accept up to five nonfiction pieces during the reading period, with each piece ranging from 500 to 2,000 words. The October issue publishes only photo essays; please submit 1-3 photo essays, each between 5 and 25 pages, for consideration. Include “RW – your name” in the subject line (e.g., “RW – Jane Haas”). Along with your submission, provide a 100-word author bio written in the third person using complete sentences. Below is our publishing schedule:

January 1 - March 31 April 15 July 1 – September 30 October 15

Missouri Baptist University reserves the right to publish accepted submissions in The Right Words. Upon publication, copyrights revert to the authors. By submitting, authors certify that the work is their own. All submissions are subject to editing for clarity, grammar, usage, and Christian propriety. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of Missouri Baptist University.

Issue 18, October 2024

© 2024 Missouri Baptist University

“Words satisfy the soul as food satisfies the stomach; the right words on a person’s lips bring satisfaction.”

Proverbs 18:20 (New Living Translation)

“The difference between the right word and the almost right word is the difference between lightning and a lightning bug.”

Mark Twain

“One day I will find the right words, and they will be simple.”

Jack Kerouac

By John Zheng

Seven years ago, I was invited to submit my poems to a moon anthology. As if moonstruck, I fell in love with photographing the moon in the Mississippi Delta. With the camera in my car or my pants pocket, I snapped the moon by a country road, by the fishpond, on the rooftop of a building whenever I felt urged to photograph, which was a discovering process for creative imagination. One November night, I was waiting on the roof of a tall building for the rise of the blood moon. When it rose, I forgot my shivering in the wind, I became excited, and my fingers were no longer numb with cold. In my stare, the blood moon, called the Beaver Moon, appeared over trees like fruit for my hunger:

deep autumn biting a persimmon for its fullness

My wife said I was a lunatic, but I felt a fullness of life through shooting the moon. Since life in the Delta is as flat as the cotton land stretching to the horizon, I thought moonshooting was not a bad seasoning to flavor my flat life. It was also a creative way to kill time, not for nothing but for creation. Each night the moon rises in the sky to accompany us humans, tranquilize our minds, and provide an image for our imagination. As a contemporary poet, I am not as romantic as ancient poets like Li Po. In a poem he wrote, he sighed that his homesickness grew intense upon looking up at the bright moon. I see the moon for its aesthetic thingness, light that creates shadows, shape that intrigues imagination, or vehicle for transference of senses or juxtaposition.

autumn moon osmanthus fragrance in the yard

In short, this “lunacy” led to the publication of a haiku sequence in the moon anthology and 10 moon haiga and some sequences. I also compiled a moon collection titled “One Hundred Visions of the Moon,” a moonshot

that required an investment of time. Now my moon photographs are like deadstock or a moon in a wane-and-wax cycle in my digital files, from which I dig out some for the photo essay issue of The Right Words. And I hope my readers will treat these photos as the right words that convey the thingness of the moon.

By Dan Steinbeck

For years, I was active in community journalism as a writer and photographer. I always tried to seek out something different in the photos when I could. My late father taught me to “shoot (the camera) with square eyes. ” In other words, I was to mentally frame a subject before I took the picture. I’ve tried to have square eyes since then in the thousands of photos I’ve taken.

As journalism offered different subjects to photograph, this collection of subjects is different too. Some of them are from various vacations taken (the bridge, the zoo, the nature shots). Some came from walking around our house (the tulips, the spider web). Some of them are just looking at things that struck me as funny and the caption shows a perhaps snarky take on these (the “salad” sticker, the road sign, the yard ornament, the fortune cookie, the “watermelons,” the yard ornament). Some are just photos I really like (the bus, the child’s statue).

Photos are wonderful because often, a photographer gets a shot someone else wishes to have had but can appreciate that someone got it. Many photographs of others that I have seen have led me to wish I had taken that. Whoever the photographer, any decent photo has a story to tell.

Love birds at the Kansas City Zoo, August 2016.

Eyeing the Tiger, Kansas City Zoo, August 2016.

A butterfly has found a place to nestle in a flower patch. Columbia, MO, 2024.

A dragonfly finds a perch near lily pads. Columbia, MO, 2024.

in Canton, MO, April 2024.

The nectar collector is at work in Tickseed flowers. Columbia, MO, June 2024.

Water droplets illuminate an otherwise hidden spider web between a planter and rocks in Canton, MO, July 2021.

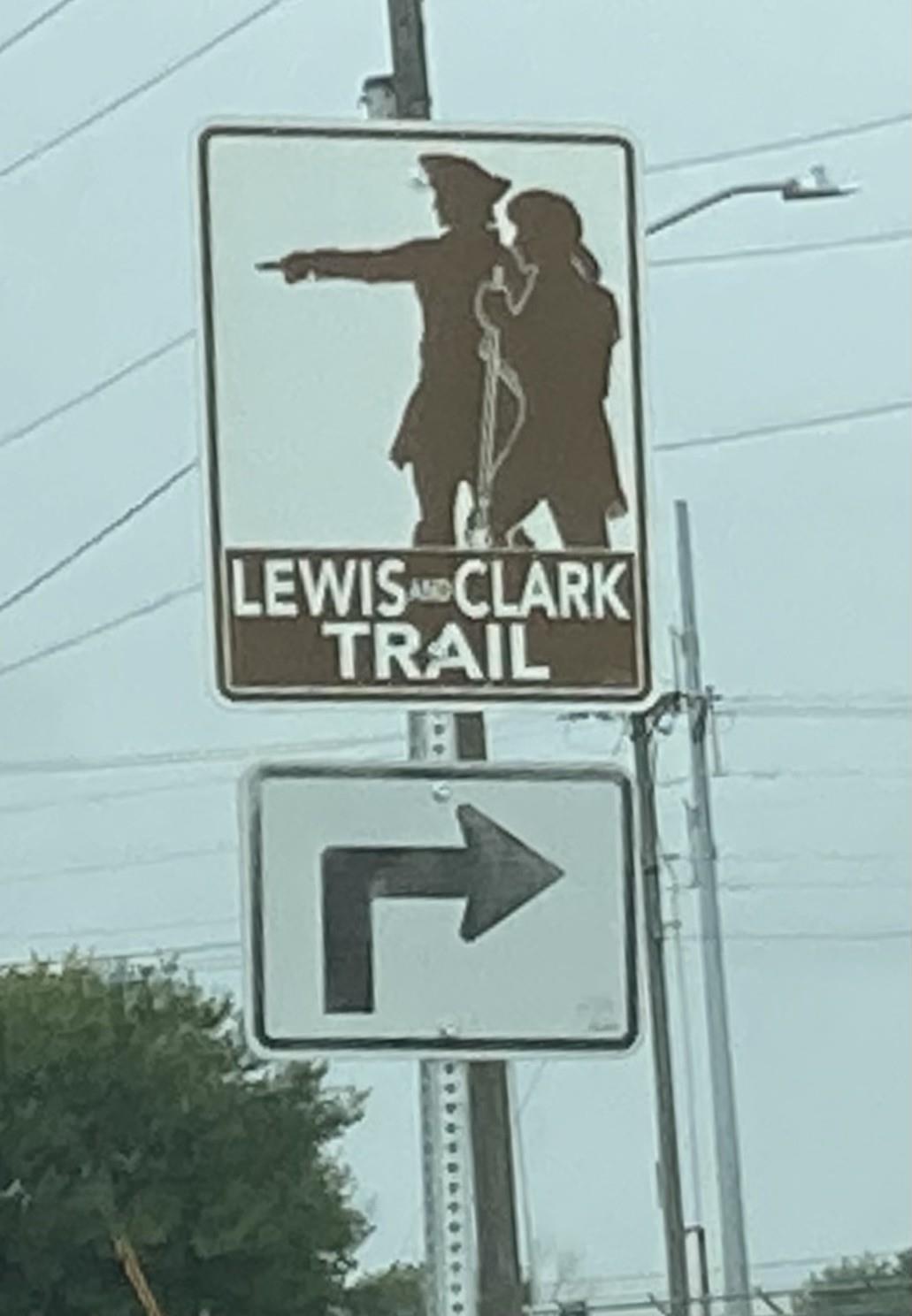

Lewis and Clark seem to be at odds with the state highway sign, Missouri, 2021.

This photo won second place in 2023 for a National Rural Transit Assistance Program, on the theme of rural transportation. The bus is near an Amish sawmill and next to round hay bales, located northwest of Canton, June 2023.

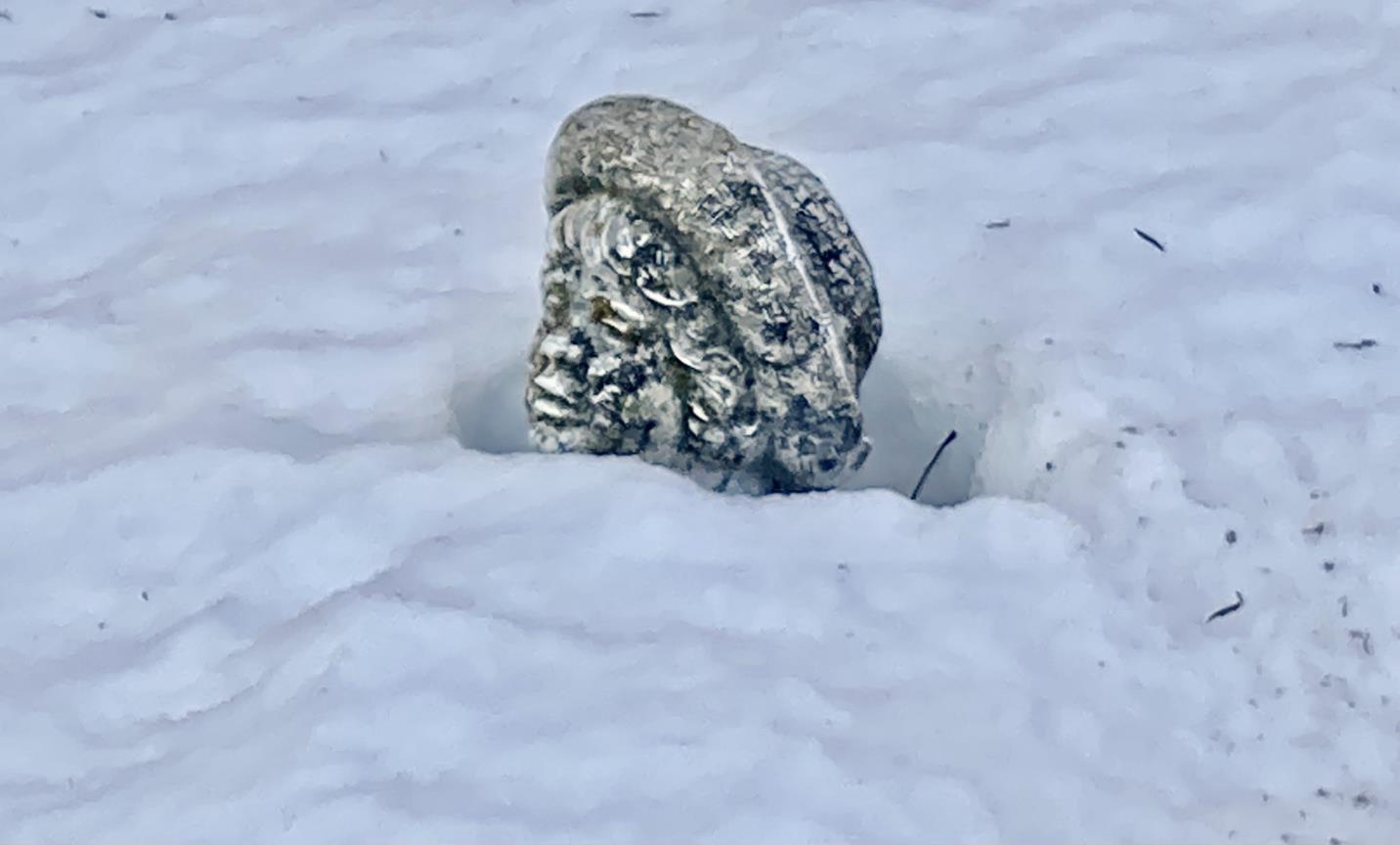

The yard ornament is striving to get his head above the snow, Ewing, MO, 2020.

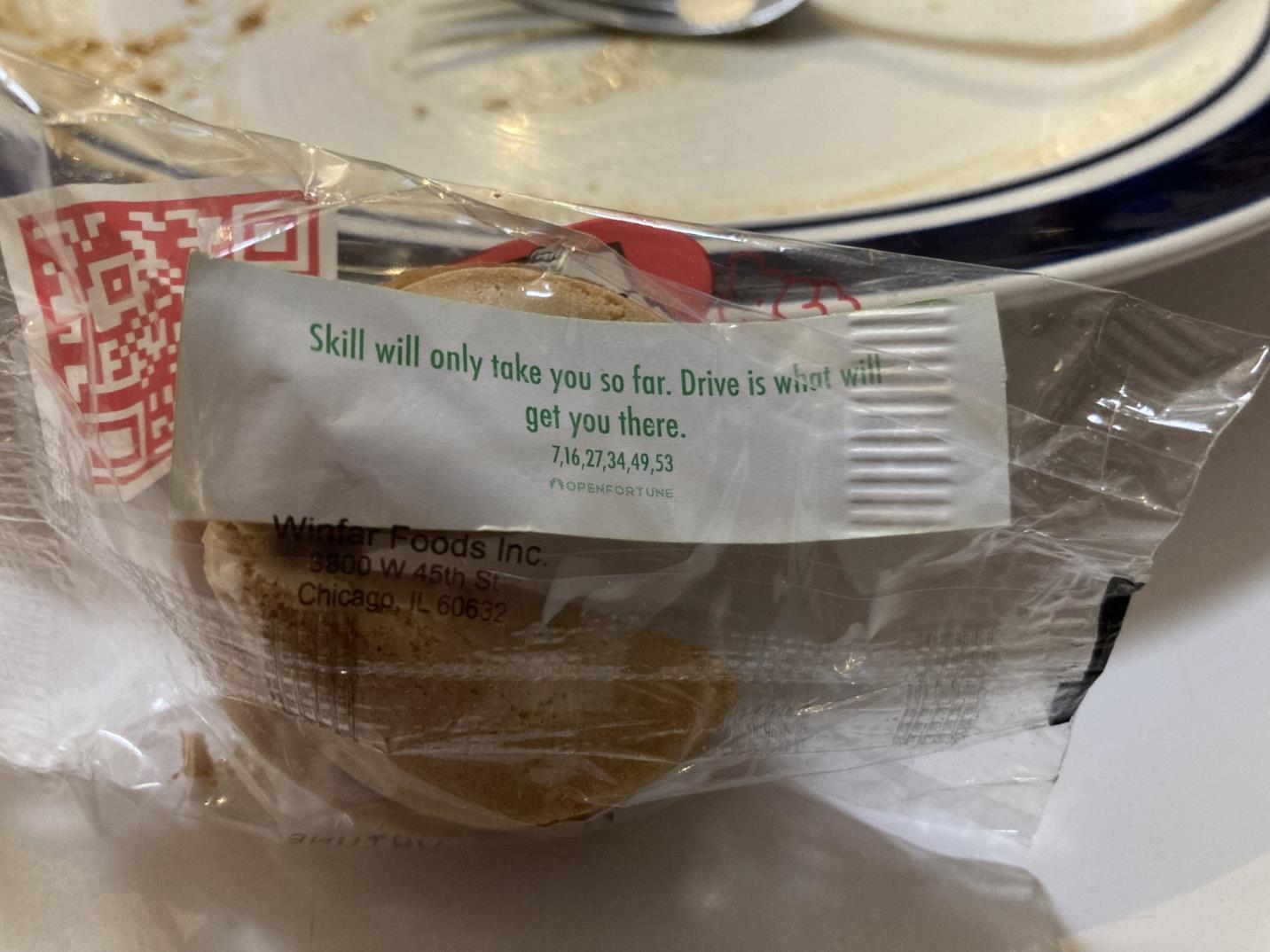

Skill obviously didn’t play a role in quality control for this yet-to-be-opened fortune cookie, February 2023.

Apparently, salad now comes in a jug, March 2022.

The box says watermelon, but they sure seem to be more like pumpkins. Cantril, Iowa, November 2023.

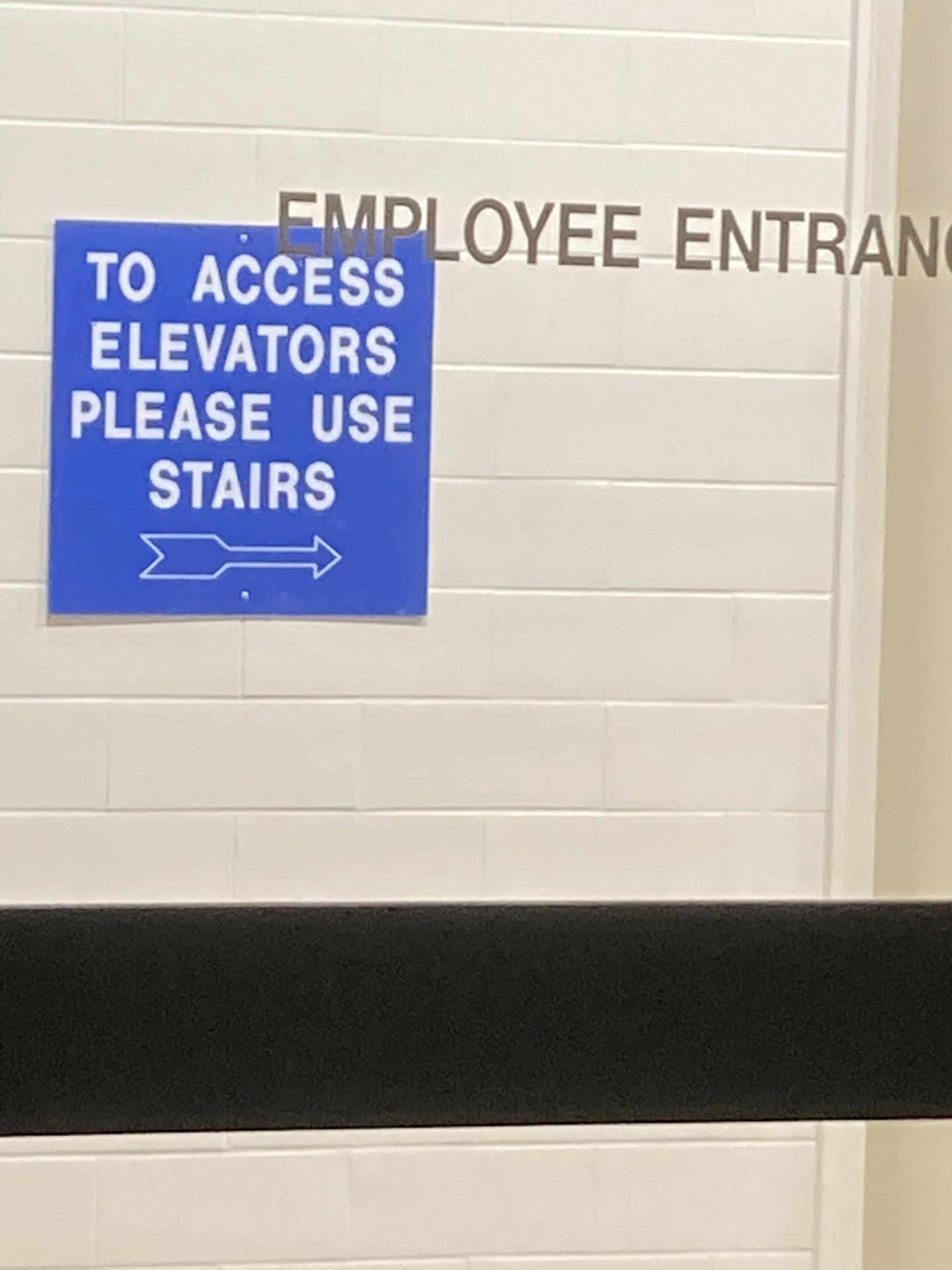

This photo was taken at a healthcare facility in Quincy, Illinois. Do they employ any motion-limited employees, such as those in wheelchairs? November 2022.

The joy of a child playing is seen in this statue of children, with space for one live child, a granddaughter of the photographer, March 2024.

By John J. Han

All over the world, people love nature, which also serves as a main staple of literature. William Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” (1807), John Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale” (1819), W.B. Yeats’s “The Wild Swans at Coole” (1917), and Robert Frost’s “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening” (1923) are four of the most well-known nature poems from the Western world.

However, the East Asian love for nature seems particularly profound. Nature does not merely please the eye or inspire the human soul. Instead, its presence is pervasive, influencing the art, shaping how people think, and determining the designs of buildings and communities. Traditional Japanese and Korean poetry shows that nature is more than an accessory to human activities. Rather, it elicits people’s reverence and gives instructions on living. Nature lies at the heart of tanka and haiku, two popular short poetic forms from Japan, as well as kanshi (漢詩, “Chinese poetry”) and sijo, two traditional poetic forms from Korea. Below are four exemplary poems written in their respective forms:

(tanka)

Alas! The beauty of the flowers has faded and come to nothing, while I have watched the rain, lost in melancholy thought.

Ono no Komachi (825-900), translatedby Helen Craig McCullough

(haiku) old pond

a frog jumps into the sound of the water

Matsuo Basho (1644-94), translated by Jane Reichhold

(hanshi)

奉和樂善齋 (Chinese)

一天霜雁送寒聲

봉화낙선재 (Korean)

일천상안송한성

河漢迢迢夜氣晶 하한초초야기정

臥病胡床仍不寐

透簾明月照深情

[At

와병호상잉불매

투렴명월조심정

In the frost-filled sky, the geese cry cold, Beneath the distant Milky Way, the night air is crystal clear. Fallen ill in Qing China, I lie awake, Only the bright moon outside shines deep in my heart.

Grand Prince Inpyeong (1622-1658), translated by John J. Han

(sijo)

Shaking off the dust of the world, I wear straw shoes and carry a bamboo cane. Cuddling a geomungo* at my side, I set out for West Lake. Seagulls soar among the reeds they are my true friends.

Kim Seong-gi (fl. in the time of King Sukjong, 16611720), translated by John J. Han * The six-stringed Korean zither.

These poems illustrate the prominent role of nature in the lives of traditional East Asians. Since the arrival of Western culture more than a century ago, East Asians have gradually adopted a utilitarian view of nature, seeing nature as something removable for “development.” However, the love for nature is engrained deeply in the subconscious of East Asians.

As a regular visitor to Japan and South Korea, I have witnessed many examples that underscore the centrality of nature in East Asian thought. The following pages feature photos taken during my journey to the two neighboring countries in May and June 2024. They demonstrate the profound impact of nature on the psyche of the people in Japan and South Korea.

Thousands of years of happy reign be thine; Rule on, my lord, until what are pebbles now By ages united to mighty rocks shall grow Whose venerable sides the moss doth line.

Part of a stone wall in the outer garden of the Imperial Palace, Tokyo, displays moss, a symbol of ageless tranquility. The scene is reminiscent of the ancient tanka “Kimigayo,” which serves as the national anthem of Japan:

Japanese: 君が代は 千代に八千代に 細石の 巌となりて 苔の生すまで

Translated by Basil Hall Chamberlain (1850-1935)

The ground of the outer garden of the Imperial Palace, Tokyo, displays the name of a prefecture (岩手県, Iwate-ken) and its flower symbol, the kiri (paulownia). Professor Yuko Kanaya, a Japanese friend of mine who teaches English literature at several universities, tells me that there may be additional flower decorations that represent other prefectures within the Palace grounds.

Scene #14 from The Tale of Genji displayed at Sumiyoshi Shrine, Osaka, Japan. In this folding screen painting, people are portrayed under the commanding presence of nature.

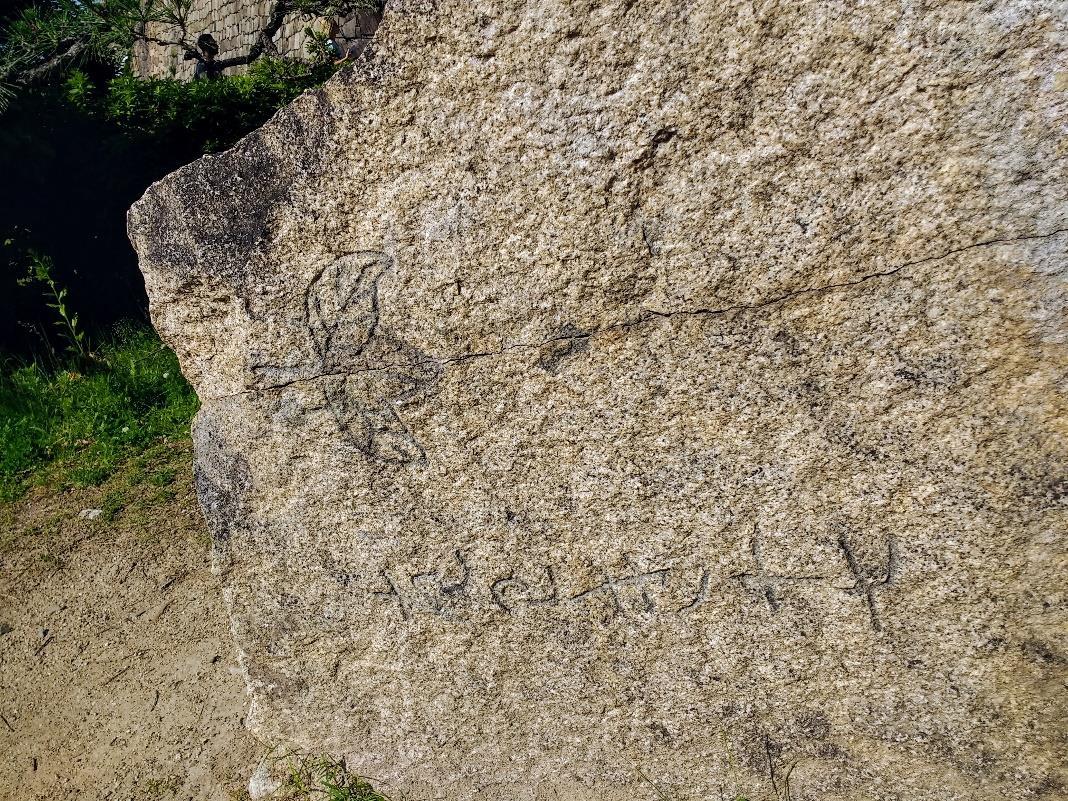

At Osaka Castle, a huge rock displaced outdoors contains a carved leaf. The stonemason, typically engaged in masculine tasks, likely had a delicate heart that inspired him to portray nature on the rock.

Shin-Osaka Station includes the “Shin-Osaka Japanese Garden,” featuring the four seasons typical of a Japanese garden, next to its main building. The sign reads, in part,

Cherry blossoms in spring. Warm hues in autumn. Evergreen in winter. Here, in this traditional Japanese garden, you sense the ebb and flow of the four seasons.

Every city needs more natural greenery. That’s why we create spaces like this.

So pause for a moment and savor the gifts of nature.

Part of Osaka Castle illustrates the typical scenery of a Japanese castle with rocks, trees (especially pine trees, which symbolize longevity and uprightness), gardens (hidden in this photo), and water.

Connected by tranquil water, the man-made bridge in the distance harmonizes with the azaleas in the foreground. Harmony (和, wa) is a foundational virtue in Japanese culture governing the relationship between people and between humans and nature. This photo was taken inside Sumiyoshi Shrine, Osaka.

This small garden, located near Hakata Station in Fukuoka, Japan, features various flowers. The slogan in the middle photo reads “一人一花” (“One Person, One Flower”).

The package for “carp bread,” which conceals a sweet red bean filling inside, is adorned with a fish design. Whenever I visit my home village in Korea, I buy a couple of bags of carp bread from the vendor at the county bus terminal. (See the second photo.) I have fond memories of the bread from my childhood, and each piece costs only 36 US cents.

Nature-inspired images decorate many items in my mother’s kitchen in Korea. In the photos above, a sitting table is furnished with a bas-relief of three cranes, while the bowls, cups, and metal trays are graced with floral designs.

The blankets and pillows at my mother’s home in Korea feature floral designs.

(Top) Flower leaves accentuate a paper door at my mother’s home.

(Bottom) The wallpaper at my mother’s home is festooned with a floral pattern.

Artificial cranes grace the streets of Hak-dong (학동 in Korean, 鶴洞 in Chinese), Gwangju Metropolitan City, Korea. The sign reads,

Hak-dong Duru Village Where People Nurture Happiness Together

Hak-dong is called Hak (crane) Village because its hilly landscape resembles a crane nestled at the foot of Mt. Mudeung. “Duru,” meaning “all-inclusive,” indicates that the area is furnished with everything, including public transportation, medical facilities, businesses, and educational institutions.

Above is Mt. Mudeung as seen from the observation tower of Sajik Park, near Hak-dong. The contour lines of the mountain resemble those of graceful cranes. The white building with more than a dozen pointy roofs at the mountain’s base is the main building of Chosun University (조선대학교 in Korean, 朝鮮大學校 in Chinese). I attended the nearby Chosun University High School in 1972-74. During my childhood and adolescence, Gwangju Metropolitan City served as the capital of South Jeolla Province.

Instead of US-style graffiti, which often delivers political commentary, some Korean fences and walls feature murals with floral patterns. In this image, even the guardrail is enhanced with a flower pattern. This photo was taken from inside a bus passing through Pocheon, Yeonggwang County. I attended middle school in Pocheon, which now operates on a much smaller scale, in 1969-1971. (See the photos below.)

The Han clan used to be the largest group among residents in Wolsan (월산 in Korean, 月山 in Chinese, “moon mountain” in English) Village, Yeonggwang County. Centuries ago, the village was named after the moonshaped slope. My paternal grandfather and father were born here before moving to a rice field over the hill on the left. As a child, when the community was much larger, I often visited my granduncle’s house to attend ancestral rites.

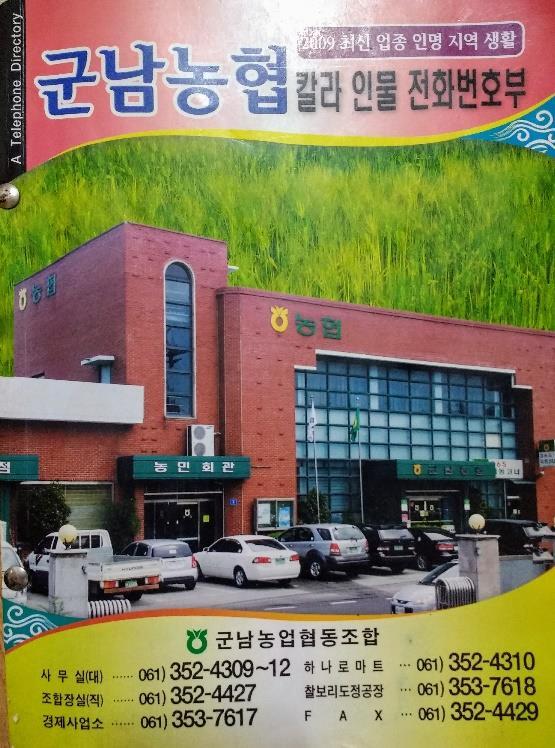

Above are the front cover and two internal pages from the resident directory published by a local agricultural corporative in my native county. The images adorning them reflect the affinity with nature that country people feel in their daily lives.

(Top) Patterns of flowers and butterflies made of steel complement the natural flowers in the garden next to the water-side park in Mokpo, South Jeolla Province.

(Bottom) Bamboo grows inside the men’s room at Daecheon Rest Area, South Chungcheong Province.

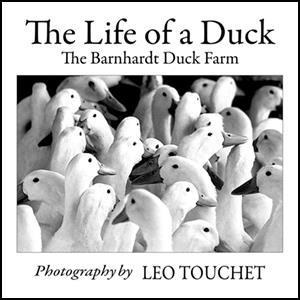

Touchet, Leo. The Life of a Duck: The Barnhardt Duck Farm. Photo Circle Press, 2024. ISBN: 978-1732443389 (paperback). 52 pages, $17.00.

Reviewed by John Zheng

Leo Touchet is an American photographer who has photographed in over fifty countries for numerous corporations and publications (Life, Time, National Geographic, New York Times, Popular Photography, etc.) and exhibited his photographs in over thirty museums, art centers, and universities. In 2024, he published his ninth photography book The Life of a Duck.

The thirty-six black-and-white photographs, selected from hundreds, document the life of a duck from incubator to market at the Barnhardt Duck Farm, a three-generation business for sixty years, near the shore of the Chesapeake Bay in Urbanna, Virginia. Taken in 1970, some of Touchet’s duck photographs were distributed to farming organizations and published by United International Press (UPI) and the Washington Post. Touchet says in his introduction that the farm was closed in 1986. Therefore, these photographs, taken over half a century ago, have historical significance for

the documentation of the duck farm business and the study of photojournalism because they are the records of a family story related to duck farming. A valuable part of this book that complements Touchet’s photographic work is the inclusion of five short articles by the owners’ four children and a granddaughter who wrote about “their experiences growing up on the duck far” (5).

Touchet chose an ideal photograph for the cover, a close-up of duck heads whose curious eyes catch our attention immediately and urge us to turn to the new page. The first two photographs show aerial views of the surrounding landscape of the duck farm that “produced almost 1.5 million ducks per year.” They create a visual effect for the viewer to understand the largeness of the farm. The next two photographs present eggs in the incubator and little ducks breaking open shells. Two photographs following them show human hands tending to ducklings, the second of which is more than about the hand. It showcases a boy, the owner’s oldest son, who holds a fluffy duckling in his right hand. This photograph captured a moment that shows the boy lowering his head to look attentively at the little creature, and his gentle holding shows curiosity and tenderness. The next photographs document the growing period of ducks from fluffy ducklings to adult ducks walking in or outside barns, swimming, bathing, preening, splashing, head-bobbing, or dabbling with bottoms up in the pond, or wingflapping behind the fence.

One charming photograph is the double-page spread on pages 14 and 15, which presents ducklings crowding together in the morning shine. Silhouetted against the light, each duckling becomes a dark shape edged with light. Touchet shows his skills in using light and shadow to create an amazing effect for visual appreciation, as shown in his dune photographs which use light and shade to present the feminine beauty of nature. Likewise, this photograph of ducklings uses light and shade to present a view of a dreamy moment that’s both temporal and spiritual and issues a mystic sense through the silhouette. However, the happy, quacking times of farmed ducks are short. As soon as they grow into adult ducks, they are processed as meat for human beings. Photographs on pages 28 and 29 show ducks cramming through a narrow, fenced path to the slaughterhouse. Then a stunning photograph shows two workers grabbing ducks and shackling them upside down on the rail while one duck looks at the happenings. Then the rail transports shackled ducks to the next stops where they are stunned, killed, dislocated, scalded, eviscerated, chilled, cut, and packaged. Irony occurs in the last photograph which presents duck feathers still useful for human beings. As

William Christopher Barnhardt remembers, duck feathers were sold “in 800-1100-pound bales” (46).

Significantly, The Life of a Duck is a photographic record of a duck farm and the hardworking, “eight-day week” business (43). It is also a collection of memories and stories of the Barnhardt family. Leo Touchet must be acclaimed highly for his meaningful photojournalism on farmed ducks as a symbol of fertility and food. The large quantities of farmed ducks convey a biblical message, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth” (Gen 1:28). And we can say that Touchet’s photographs are infinite and fruitful to us.

John J. Han, Ph.D., is Professor of English and Creative Writing and Associate Dean of the School of Humanities and Theology at Missouri Baptist University. He is the author, editor, co-editor, or translator of 35 books, the most recent being Certainty and Ambiguity in Global Mystery Fiction: Essays on the Moral Imagination (Bloomsbury Academic, 2024). Han has also published more than 2,500 poems in periodicals and anthologies, including Cave Region Review (featured poet of the year 2012), Failed Haiku, Frogpond, The Laurel Review, Modern Haiku, Simply Haiku (chosen as the world’s sixth-finest English-language haiku poet for 2011), Valley Voices (Pushcart-nominated), Wales Haiku Journal (nominated for the Touchstone Award), and World Haiku Review.

Dan Steinbeck is a Southern Baptist pastor in northeast Missouri and a regular contributing writer for the Pathway of the Missouri Baptist Convention. He also drives a bus for OATS transit. He has a long career in community journalism, for which he won several writing and photography awards. He has authored three books of various genres and had articles published in Missouri Life magazine. He enjoys laughter and finds joy in pictures that capture moments of humor.

John Zheng’s 20 photo essays have appeared in journals including Arkansas Review, Intégrité, Maine Digital Collaborative, Mississippi Folklife, and The Southern Quarterly. His photographs have also been used for covers of magazines, books, and anthologies. He lives in the Mississippi Delta where one will see the moon playing a sonata.