Page 10

Paris, Finland

1924–2024

Page 14

Midsummer: A night of magic

Page 20

The

Page 25 a

please leave this magazine for the next guest –

thank you!

Page 10

Paris, Finland

1924–2024

Page 14

Midsummer: A night of magic

Page 20

The

Page 25 a

please leave this magazine for the next guest –

thank you!

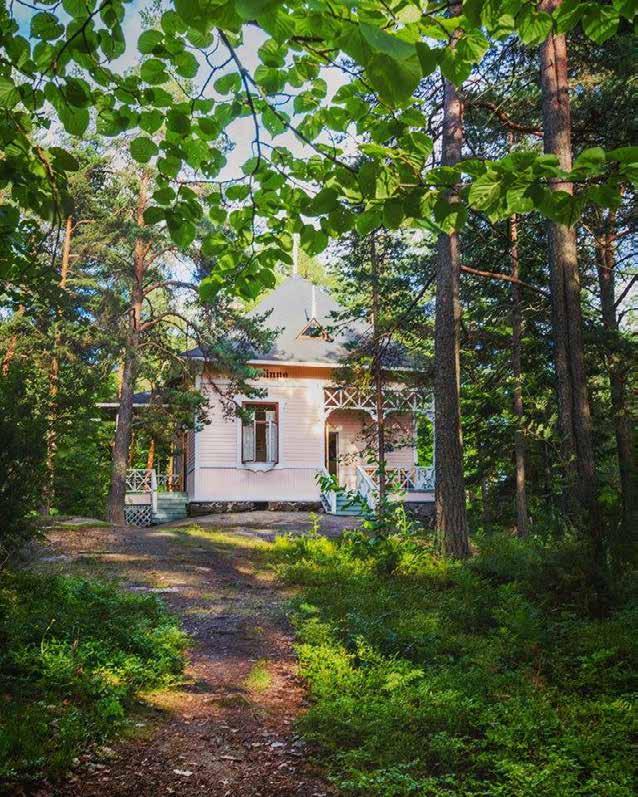

Kotkaniemi

presidentti P. E. Svinhufvudin kotimuseo the home museum of president P. E. Svinhufvud

Museum, café and garden – opening hours 2024: 25 May–1st September: Tue–Sun, 11 am–5 pm

Museo, kahvila ja puutarha – aukioloajat 2024: 25.5.–1.9.: TI–SU klo 11–17

Kotkaniemi, Itsenäisyydentie 799a, 54530 Luumäki tel. +358405227553 • info@kotkaniemi.fi • www.kotkaniemi.fi

TIMES-LEHDET TAVOITTAVAT 2,5 MILJ. HOTELLIYÖPYJÄÄ VUODESSA

Metropolitan Times | Tampere Times | Turku Times | Saimaa Times

Varmista näkyvyytesi | Puh. 045 656 7216

The Lake Saimaa region has been awarded the prestigious, international European Region of Gastronomy title. The unique gastronomy and culture of Eastern Finland are celebrated with rich experiences that combine the purest food in the world and the original culture.

Find the gems and unique events of Eastern Finland:

Photo: Harri Säynevirta

Taste Saimaa

Photo: Harri Säynevirta

Taste Saimaa

Saimaa Times

Magazine for Visitors

Issue 2024

www.saimaatimes.fi

ISSN 2814-4651 (print)

ISSN 2814-4813 (online)

Graphic design & layout

Petteri Mero

Mainostoimisto Knok Oy

Printed by Newprint Oy

Leisure, water and good food 8

Tracking down the Ice Age 10

Saimaa area in a nutshelll 12

Paris, Finland 1924–2024 14

Map of Saimaa region 16

Hotels providing Saimaa Times 18

Midsummer: A night of magic 20

The Forbidden Kalevala 22

The museums of Lappeenranta are focused on culinary culture in 2024 25 Safe havens – Column by Elina Hirvonen 28

Editor in chief

Roope Lipasti

Sales manager Raimo Kurki raimo.kurki@aikalehdet.fi

Tel. +358 45 656 7216

Sales Pirkko Puurunen pirkko.puurunen@aikalehdet.fi

Tel. +358 40 507 1002

Published by Mobile-Kustannus Oy Brahenkatu 14 D 94 FI-20100 Turku, Finland

Member of Finnish Magazine Media Association (Aikakausmedia)

Publisher Teemu Jaakonkoski

Cover photos

Lake Saimaa. Photo: Mikko Nikkinen / gosaimaa.com

Lodge in Hirvimäki, Mikkeli. Photo: Visit Saimaa Captain playing music. Photo: Visit Saimaa Summer fun. Photo: Anu Nuutinen / gosaimaa.com Elina Hirvonen. Photo: Otto Virtanen / WSOY

Saimaa Times map application for mobile phones and tablets: www.saimaatimes.fi.

4041 1018

The magazine is available in hotel rooms in the Saimaa region (see page 18). Next issue will be out in March 2025.

The Saimaa region has been awarded the international European Region of Gastronomy status in recognition of Eastern Finland's unique food culture. In 2024, visitors are invited to experience the purity and uniqueness of Finnish Lakeland. The year will be marked by various events that combine the region's cultural heritage, art and food in a new way. For example, the exhibitions in Lappeenranta's museums focus on culinary culture (see page 25).

Aside from The food, Saimaa region offers a lot to do and see, not least because Saimaa is the largest and most beautiful lake in Finland. With about14,850 kilometers of coastline when you count in its 13,700 islands, visitors to the area will find no shortage of things to do and see.

Lake Saimaa is also the fourth largest lake in Europe. It flows into Lake Ladoga, which in turn flows into the Neva River, continuing to St. Petersburg and finally to the Baltic Sea. The cities of Lappeenranta, Joensuu, Mikkeli, Imatra, Savonlinna, and Varkaus are all located on the shores of Lake Saimaa, so you can justifiably say that Lake Saimaa defines Eastern Finland.

Actually, the Lake Saimaa region is so extensive that in the northern part, you are in Savo, and in the southern part, in Karelia. Savo and Karelia are two different provinces that, according to traditional clichés, have quite different populations – completely different tribes, to use the old groupings.

If you ask a Finn what a typical Karelian is like, they will probably tell you that Karelians are cheerful people who like to laugh, like a Finnish version of a stereotypical Latin American. In Karelia, it’s okay to laugh, cry, and show emotions. Karelians are also very talkative, and if this doesn’t seem noteworthy to a visitor to Finland, it’s worth remembering that the further west you go in Finland, the more reserved and tight-lipped the people are. In Karelia, they apparently aren’t familiar with the famous quote that describes the Finns “being silent in two languages.”

In any case, in places like Imatra, Lappeenranta, and Joensuu, you can experience the cheerful and hospitable Karelian spirit. Not to mention the best Karelian pasties, by far. Karelian pasties are one

of Finland’s national dishes: small, open-face pies with a thin rye crust that are usually filled with rice porridge (barley porridge or mashed potatoes are other acceptable fillings). Karelian pasties are topped with a mixture of butter and chopped boiled eggs, and they are definitely a delicacy worth trying!

The Savonians who Live on the shores of Lake Saimaa are again a group of their own. According to the clichés, they are easy-going and good-natured, and their sense of humor is in a class of its own. People from Savo are also said to be sly, but not in a negative sense. Rather, it refers to the fact that you can never be quite sure what a Savonian is thinking or whether they are teasing you. There’s a saying that when a Savonian talks, responsibility falls on the listener. A Savonian has definite ideas about everything, but on the other hand, he might have a different opinion after all.

Since everyone in Savo lives no more than a few meters from the shore, it should come as no surprise that the area’s food culture incorporates fish in many forms. Fried vendace, a plateful of small lake fish, is one famous and typical Savo food. In Savo, they also swear by rye: it is used not only to make bread, but also for lingonberry rye porridge.

All and all, the food culture of Eastern Finland is rooted in the pure forests and lakes of the region. The long, white nights of the north create the perfect conditions for wild vegetables, berries and mushrooms. And of course, the fish from the clear lakes are something quite unique. Bon appetit!

Finland’s surface area is 75 percent forest. The forests are an endless treasure trove, where you can even see signs of the Ice Age.

Finns are often considered a somewhat cold people. Maybe one reason for that is that Finland was only finally freed from the clutches of a huge ice mass around 10,000 years ago. It takes a while to thaw out after that, especially since 20,000 years ago, there was a glacier up to 2.5 kilometers thick covering Finland.

Traces of that massive chunk of ice can still be seen in the Finnish landscape. One thing that Finnish forests are especially good for – besides getting lost – is looking for signs of the Ice Age. The forests, including Finland’s urban forests, are full of them. Let’s head to the forest, then!

There are plenty of options for where to go – after all, Finland is Europe’s most-forested country relative to surface area. Even better, Finland has an arrangement called “Everyman’s Rights,” which means that the forests are public, in the sense that everyone is free to visit them to enjoy nature

and the fresh air, as well as to forage for berries or mushrooms.

A 2.5-kilometer-thick piece of ice weighs quite a lot, and it pressed a dimple into the earth’s surface, as if it were a football with too little air. Around Turku, for example, the land sank 800 meters, although most of it quickly rebounded once the ice melted. Nonetheless, the land on the west coast of Finland is still rising half a meter every hundred years.

The most visible signs of the Ice Age in Finland are the country’s thousands of lakes. They number around 168,000 in total, depending on how you count. Many of them were born when the ice pressed a hole in the ground, which then filled with meltwater.

transLatedSuch large bodies of water as Lake Päijänne and Lake Saimaa originated in the Ice Age, for example. The shallow lakes near the coast are much younger.

Another massive relic of the Ice Age in the Finnish landscape are eskers, long ridges of sediment that formed under glaciers, the largest being Salpausselkä in southern Finland (or actually the Salpauselkäs – there are three of them). Smaller sandy eskers are scattered around Finland. When driving almost anywhere in the country, you’ll come across large sand pits where sand has been excavated for the construction industry.

When the ice melted at the end of the Ice Age, large, swift rivers flowed inside it. The rivers carried sediment and gravel as they flowed, forming eskers. The eskers are old riverbeds.

One sign of the Ice Age you’ll find everywhere is the large boulders called glacial erratics. Actually, all the stones dotting the forests are from the Ice Age, but the erratics are the most impressive. When the ice began to melt, its power was tremendous. Glaciers and water broke the bedrock and snatched up large stones the size of houses; they ended up in the strangest places.

Finland’s largest glacial erratic can be found in the sea off the coast near Turku. Its name is Kukkarokivi, and according to the story, it was thrown there by an angry giant. The stone is the size of a large detached house.

Many stone curiosities can be found in Finland, such as huge glacial erratics that are so acrobatically arranged that if you push them, they will sway, but always return to their place.

One beautiful example is the Kummakivi, located in Ruokolahti, which is a car-sized boulder that rests atop another rock, but with such a small point of contact that it almost seems to float.

Glacial erratics have also made good boundary markers through the ages because they are impossible to move. Another curiosity perhaps worth mentioning is the Kusikivi, or “Peeing Stone,” in Ostrobothnia, which according to the locals, is an important attraction at a certain road crossing. The stone is not very big, but reportedly, the king of Sweden once ducked behind it to do his business.

One of the most extraordinary signs of the Ice Age are so-called devil’s fields. They are areas where the ground is completely covered with large stones. In the old days, people didn’t know what they were, so

Finland’s Everyman’s Rights allow you to…

• walk, ski, cycle and swim in nature, as long as you’re not in someone’s yard or in cultivated fields, for example

• stay temporarily (for example, in a tent) in any area you are allowed to move through

• pick berries and mushrooms, and plants that are not protected by conservation law

• fish with line and rod and ice fish

• travel over ice and on waterways.

Everyman’s Rights do not allow you to…

• cause harm to others, disturb anyone’s home, or litter or damage the environment

• disturb animals or their nests

• collect moss, lichen, soil or wood

• drive a motor vehicle off-road without the landowner’s permission

• fish by any method other than line and rod

it was thought that some malicious being had made them. The fields were so rocky that only a devil could have plowed them.

In reality, the devil’s fields are old sea beds, and the rocks were carried by the waves. The stones remained where they were when the earth’s surface rose and the sea receded.

Also in the category of features formed by water are “giant’s kettles,” circular holes in the bedrock that can be meters deep and are sometimes filled with water. They can be small enough that not even a child could bathe in them, or so large that you could easily go for a swim.

They were created when the movement of the ice caused stones to rub against the bedrock and slowly grind a hole in it, almost as if the stones were drill bits. Giant’s kettles aren’t terribly rare, either; even in Helsinki, you can find a dozen.

The Finnish name for giant’s kettles, hiidenkirnu, contains the word hiisi, which once referred to a sacred site but later came to mean a malevolent being.

On The coasT, the most visible evidence of the Ice Age can be seen in the formations called roches moutonnées: the smooth, rounded mounds of exposed bedrock. They rock surfaces are so smooth that it almost seems as if someone has polished them. And in a way, that’s exactly what happened: ice and water polished the rocks.

As it melted, the ice slid across Finland from northwest to southeast, as can often be seen by the direction of the grooves on the polished surfaces of the rock. s

Lake Saimaa is the largest lake in Finland – and the fourth largest in the whole Europe. It is not one big lake though, but rather consists of many smaller ones that are interconnected. Roughly measured, Lake Saimaa is 200 kilometres long and 100 kilometres wide. It is one of the most popular summer cottage areas in Finland and has about 25,000 holiday homes.

The best-known and at the same time rarest animal living in the lake is saimaannorppa – the Saimaa ringed seal – which became isolated from other ringed seal populations of the Baltic Sea about 8000 years ago, just after the ice age ended. Sadly, it is a highly endangered species today.

The largest cities in the Saimaa area are Lappeenranta, Mikkeli, Savonlinna, Imatra and Varkaus.

Lappeenranta is the 13th biggest city in Finland and has a population of about 72,000. It was founded as early as 1649 and its history can be seen, for example, in the Lappeenranta fortress area, which has many museums, galleries and much more to see. The nearby city harbour is also beautiful and offers access to Saimaa cruises.

The history of Mikkeli, with a population of 52,000, is quite belligerent. The city is mentioned in various peace treaties since the 14th century and has often been involved in war battles. During the last war, the headquarters of Finnish army was there. That is why the city has, among other things, the Headquarters Museum. Mikkeli is also Finland’s second most popular summer cottage location: there are about 10,000 cottages there.

Savonlinna is especially known for its beautiful medieval castle called Olavinlinna, as well as the famous Opera Festival that the castle hosts every summer. The city is home to 32,000 people and its surroundings are full of beautiful sights and landscapes – for example, one of Finland’s national landscapes, Punkaharju, the narrow seven-kilometer-long ridge formed during the ice age. Tsar Nicholas I of Russia fell in love with it so much that in 1843 he ordered the area to be protected.

Imatra is home to 25,000 people. The main industries are the paper industry and tourism: the city is located right next to the Russian border. Imatra is known for its exceptionally magnificent rapids, which is the oldest tourist attraction in Finland, and for the State Hotel on its shores. Dating back to 1903, the building reminiscent of a fairytale castle is well worth a visit.

The first mention of Varkaus dates back to 1323, when it was just a village as a border marker for a peace treaty. Since then, it developed into a significant center of the wood and paper industry thanks to its excellent location along the waterways. Today, the paper industry has waned even in Varkaus, but nature and wonderful landscapes remain, such as the beautiful Taipale canal or the unique Kämäri nature reserve. The city of around 20,000 inhabitants is also a city of naïve art and many museums. s

Paris will host the Olympics this summer after a 100-year hiatus. A lot has changed in that time, both in Paris and in Finland.

Written by Matti MäkeLä transLated by Christina saarinenIn 1924, Paris is the pulsating center of a world recovering from the First World War; it’s everything that New York and London would be later. Ernest Hemingway arrived in the city back in 1921, and Gertrude Stein is running her cultural salon, supporting writers and artists such as Pablo Picasso, who has been living in the city for 20 years. Josephine Baker, perhaps the most iconic symbol of the 1920s “Années folles” in Paris, arrives the following year and immediately becomes a superstar. Later, this African-American dancer and singer will be named a Chevalier of the French Legion of Honor and awarded a medal for her work in the French Resistance during World War II.

The allure of Paris does not go unnoticed by Finns either.

Mika Waltari, who rose to world fame with his novel The Egyptian, described the bohemian decadence of Paris in his early novel Suuri illusioni (The Grand Illusion): “God, how they live here! Only now have I discovered how depraved a person can be. Go stand at the bar of Le Select one night and you’ll see. I don’t care to say more. … It’s good to be here, anyway, to lose a little of those youthful dreams about the essential goodness of people and other garbage."

In T he summer of 1924, Finland is a young, poor and agriculture-dominated country that gained independence just seven years earlier, and only six years have passed since the end of the bloody civil war that divided the country. Finland’s three largest cities have a combined population of around 300,000 people (in Paris, there are nearly three million), and despite young Finnish artists’ enthusiasm for Paris, Finland is an inward-looking country where a visit by Josephine Baker led to protests as late as 1933.

Sports are of great interest to Finns, however, and are considered a way to increase national morale and make the country internationally known. Hopes are high leading up to the Paris Olympic Games because four years earlier, in Antwerp, Finland had won no less than 35 medals.

Those expectations are not disappointed, as Finnish athletes achieve a record of 37 medals in Paris, of which 14 are gold. On the medal table, Finland ranks second, after the United States. Finland’s achievement and the disproportionateness of the competition between the countries is emphasized by the fact that at the time, the United States already had more than 105 million inhabitants, while Finland had a little over 3 million.

Finland has changed enormously in a hundred years. The population has moved from the countryside to the cities, and the focus of business life has shifted from agriculture to technology, services and innovations. The combined population of Finland’s three largest urban areas is now roughly the same as that of Paris, a little over two million. (Of course, Greater Paris has more than twice as many inhabitants as the whole of Finland.) The new heroes are the founders and developers of companies like Supercell and Wolt, not long-distance runners. Even our sports heroes are generally extroverted stars of team sports, not silent loners like Paavo Nurmi.

However, not everything has changed. Somewhat surprisingly, Finland’s modest hopes for medals in Paris are in the same sports as a hundred years ago: athletics, martial arts, shooting and sailing. And despite the country’s internationalization and modernization (Josephine Baker would hardly cause protests in Finland these days), even in this year’s presidential election, opinion polls showed that a third of voters considered the homosexuality of one of the leading candidates as a reason not to vote for him.

Somewhat surprisingly, Finland’s modest hopes for medals in Paris are in the same sports as a hundred years ago: athletics, martial arts, shooting and sailing.

The biggest star of the games is Paavo Nurmi, who wins five gold medals, including both the 1,500-meter and 5,000-meter gold medals in the span of an hour. The cross-country race would also go down in history, with an overwhelming victory in almost 40-degree heat. Of the 40 participants, only 15 made it to the finish line, all of them more or less barely conscious, except for the superhumanly strong Nurmi. Finnish journalist and sports writer Martti Jukola described the dramatic final stages of the race: “Only when we see men collapsing on the field and others running back and forth, or from one side of the track to the other as if mad, do we suspect that our boys have fallen victim to the scorching sun. Some can no longer stand the excitement and cover their eyes when a Spaniard rounds a course marker like a rooster with its head cut off.”

AT The 2024 OLympic Games, Finland will no longer be in the running to win the medal table, and no Finnish athlete has a chance of becoming one of the brightest stars of the games. In the summer games of the new millennium, Finland has so far achieved a total of 12 medals, and only one gold. At the current rate, the medal haul of Paris 1924 will only be matched in 2064, and in terms of gold medals, in 2284.

And whaT abou T Paris? Paris remains a favorite filming location for TV series and movies and is considered by many to be the most beautiful and romantic city in the world. According to another point of view, the city has become the world’s largest open-air museum, where the cafes are no longer populated by Hemingway, Picasso, Sartre, Camus or countless other lesser-known artists and writers, but by tourists looking for their ancient haunts. Paris seems to lack the dynamism that continues to characterize New York and London – its two main rivals over the last century. Paris enjoys admiration inspired by its past glory, while London and New York still look to the future. London and New York are world cities; Paris is just a really big French city.

On the other hand, this assessment may be overly harsh. Paris is still one of the world’s most important cities for culture, food and fashion, and hosting its third Olympic Games (only London has been able to do so previously) says a lot about the city’s international weight. Perhaps this is the prelude to a new era for a city that was founded in Roman times. Punk and rap may not have been born on the streets of Paris, but the next big thing may already be on the horizon, which will – to quote Asterix – make Paris the “greatest city in the world.” A metropolis that moves young poets like it did Mika Waltari a hundred years ago: "How could I imagine all that. The eyes of the semaphores and the hundreds of glowing lights of switch lanterns on the great railway yard, a sea of fire in a strange city, a big city, the splendor of advertisements on the walls of grand hotels." s

The Paris Olympics will take place July 26 to August 11, 2024.

YOU ARE HERE! Hotels providing Saimaa Times are marked on the map with numbered red dots. The number of your hotel can be found from the list on page 18.

Finland

Norway Sweden

Denmark

Estonia

Latvia Lithuania

01 hoLiday cLub punkaharju

Hiekkalahdentie 128, 58430 Kulennoinen

Tel. +358 43 825 4531 www.holidayclubresorts.com

02 hoLiday cLub saimaa

Rauhanrinne 1, 55320 Lappeenranta

Tel. +358 300 870 900 www.holidayclubresorts.com

03 hoTeL hospiTz

Linnankatu 20, 57130 Savonlinna

Tel. +358 15 515 661 www.hospitz.com

04 hoTeL karTano

Kyyhkyläntie 6, 50700 Mikkeli

Tel. 440 203 320 www.kyyhkyla.fi

05 hoTeL Lähde

Ainonkatu 17, 53100 Lappeenranta

Tel. +358 44 766 5005 www.hotellilahde.fi

06 hoTeL oscar

Kauppatori 4, 78250 Varkaus

Tel. +358 29 320 0520 www.hoteloscar.fi

07 hoTeL rakuuna

Mannerheiminkatu 8, 53900 Lappeenranta

Tel. +358 10 340 2040 www.rakuunahotelli.fi

08 hoTeL raTsumies

Kyyhkyläntie 6, 50700 Mikkeli

Tel. 440 203 320 www.kyyhkyla.fi

09 hoTeL rusThoLLi

Kyyhkyläntie 6, 50700 Mikkeli

Tel. 440 203 320 www.kyyhkyla.fi

10 hoTeL saima

Linnankatu 11, 57130 Savonlinna

Tel. +358 15 515 340 www.kahvilasaima.fi/hotelli

11 originaL sokos hoTeL seurahuone savonLinna

Kauppatori 4-6, 57130 Savonlinna

Tel. +358 10 764 2200 www.sokoshotels.fi

12 originaL sokos hoTeL vaakuna mikkeLi

Porrassalmenkatu 9, 50100 Mikkeli

Tel. +358 10 764 2100 www.sokoshotels.fi

13 saimaahoLiday oravi

Kiramontie 27, 58130 Oravi

Tel. +358 44 274 7078 www.oravivillage.com

14 scandic imaTran vaLTionhoTeLLi

Torkkelinkatu 2, 55100 Imatra

Tel. +358 30 030 8452 www.scandichotels.fi

15 scandic mikkeLi

Mikonkatu 9, 50100 Mikkeli

Tel. +358 30 030 8456

www.scandichotels.fi

16 scandic paTria

Kauppakatu 21, 53100 Lappeenranta

Tel. +358 30 030 8451

www.scandichotels.fi

17 spahoTeL casino savonLinna

Kylpylaitoksentie 7, 57130 Savonlinna

Tel. +358 29 320 0540 www.spahotelcasino.fi

18 summer hoTeL ToTT

Satamakatu 1, 57130 Savonlinna

+358 10 764 2250

www.sokoshotels.fi

Maisema- ja tilausristeilyt

Tunnin maisemaristeilyllä voit nähdä ja kokea Savonlinnan kaunista saaristomaisemaa. Risteilyllä reittiselostus suomeksi, englanniksi, venäjäksi ja saksaksi.

Tickets online or straight from aboard/ship. Route guidance in English, Russian, German.

Lähtöajat 1.6.-31.8.:

M/S Lake Star (1.6.–31.8.)

10:30

12:00

13:30

15:00

16:30 (18:00)

M/S Lake Seal (n. 29.6.–10.8.)

11:15

12:45

14:15

15:45 (17:15) (19:30)

Mainitsemalla lippua (laivalta) ostaessasi

Saimaa Times saat 3€ alennuksen!

Osta liput verkkokaupasta tai suoraan laivoilta!

WE

Savonlinna sightseeing cruise m/s IEVA

Risteily kaupungin ympäri m/s IEVA

11.00, 12.30, 14.00, 15.30, 17.00 1.7.-31.7. extra 9.30, 18.30, 20.00

Cruise to the Savonlinna archipelago on m/s ELVIIRA

Maisemaristeily saaristoon m/s Elviiralla

There is one striking commonality in the old Finnish Midsummer magic rituals: everything must be done naked.

Midsummer, which falls on June 21–23 this year, is one of the most, if not the most, beloved celebrations of the year for Finns. On Midsummer, we celebrate the longest day of the year, when the sun doesn’t set at all. It’s called the nightless night, and it has its own very special magic.

On Midsummer, every Finn is willing to do whatever it takes to escape to their summer cottage. The cities empty out, and it was even more extreme in the old days – nowadays the shops at least stay open. But even today, the cities are remarkably quiet on Midsummer Day,

and even in Helsinki, you can walk down the middle of the street without worrying about being hit by a car.

If you hate people and you want to be alone, Finland is exactly the place to be during Midsummer!

Since the sun never sets, Midsummer Night is associated with strange magic and magical rites. For example, Finns light bonfires on Midsummer. We’re talking proper, impressive bonfires along the shore in front of practically every summer cottage – though the authorities usually forbid it, citing the risk of forest fires. Often they are lit regardless.

Originally, the purpose of the Midsummer bonfire was to ward off evil spirits. Nowadays, people mostly gather around them to indulge in a different kind of spirits.

Midsummer dances are also traditional, gathering people together in some remote village to celebrate. A Midsummer sauna is self-evident. The Finnish flag plays a role, being hoisted on the flagpoles at 6 p.m. on Midsummer Eve. In Swedish-speaking areas in particular, a Midsummer pole is erected: crossbeams are attached to a tall, flagpole-like post and decorated with flowers and greenery. Unlike in the movie “Midsommar”, however, no one ends up sacrificed.

Midsummer, like many other festivals of the year, was originally a celebration related to ancient beliefs and light that has since been replaced by Christianity: Midsummer now celebrates the birthday of John the Baptist, hence its Finnish name, Juhannus.

So it’s no wonder that many kinds of spirits are said to be active on Midsummer Night, and that it’s also particularly auspicious for magic. The biggest objective of Midsummer magic by far is to improve one’s marital fortunes and hopefully see one’s future spouse in advance. (That’s wise, so you know to run away when the big moment draws near.)

For some strange reason, the magic also often requires that young maidens parade around in various places without clothes. Old-time wishful thinking, no doubt.

Nonetheless, the most well-known Midsummer magic is chaste: if you collect seven different kinds of flowers on Midsummer Night and place them under your pillow, you will see your future spouse in your dreams. An alternative outcome is hay fever.

If you’re especially eager to get out of your clothes, Midsummer Eve is a splendid opportunity. For example, if you look into a well,

pond or spring on Midsummer Night – while naked – you will see your future spouse.

It’s especially lucky for finding a spouse if on Midsummer Night you roll around naked in a dewy meadow. You might want to warn the neighbors in advance so they don’t call the police on you.

Every Finn knows the Midsummer magic that says that if you run naked from the sauna along the ditches of a rye field, you’ll find your groom at the ninth ditch. Don’t worry about the first eight. Of course, finding a rye field can be challenging these days.

Fortunately, other fields are also of use: if you circle a triangular field naked three times on Midsummer Night, you’ll come across your future life partner on the third lap. What a wonderful first meeting!

Another way to see your future spouse, and without so much physical effort, is by entering a rapid on Midsummer Eve and sitting on a rock in the water completely naked except for a straw belt. In Finland, the rapids are always full of shivering maidens during Midsummer, you see.

But why bother going the extra mile: if on Midsummer Night a girl sweeps the floor of her bedroom stark naked, with just a red string around her waist, the ghost of her fiancé will come to greet her. A bit creepy, admittedly.

Modern Times have contributed to Midsummer magic as well. For the sake of equality, this magic is for the men: If on Midsummer, you spend three days at the cottage fall-down drunk, run pantless to the neighbor’s cottage looking to score, and on the way back stop to piss on the bonfire and fall in, then in the evening when you go to sleep, you can see, on the other side of the bed, your very-soon-to-be ex-wife. s

If you collect seven different kinds of flowers on Midsummer Night and place them under your pillow, you will see your future spouse in your dreams.

Finland’s national epic is a cleaned-up version of the material that was collected. The raunchiest folk poems would make OnlyFans blush.

Written by roope Lipasti transLated by Christina saarinenEveryone knows the Kalevala, Finland’s national epic. You know, the one that is generally mentioned in the same context as lofty works like the Odyssey and the Iliad or even Gilgamesh

But though the name is familiar, few have read the whole thing, and that’s true for Finns as well. So here’s a refresher: The Kalevala is a loosely-plotted story about the various disputes, revenge missions, wooing trips and other misadventures of the people of Kalevala and Pohjola. The wizard Väinämöinen is one main character, but there are plenty of others involved. The smith Ilmarinen,

The poems depict the joy of sexuality, longing for sex when you aren’t having it, passion, love magic and all the other things that we associate with sex even today.

for example, is a key character who forges the Sampo, a kind of wealth-producing miracle machine, which is later stolen by the wicked Pohjola. In addition, there is a seemingly endless number of young men who all fare more or less poorly.

There are women too: The Mistress of Pohjola is Väinämöinen’s evil opponent. The beautiful maiden Aino, on the other hand, is Väinämöinen’s desired bride, but the young girl herself isn’t so hot about the idea. The famous painting by Akseli Gallen-Kallela captures the #metoo spirit of the situation.

All in all, the Kalevala is an exciting and heroic story that could easily be made into a Marvel-type movie. But despite all the folklore ingredients, it is largely the product of Elias Lönnrot’s (1802–1884) pen. The poems themselves are largely authentic, though Lönnrot shaped them in places to make them sound better. But Lönnrot is the father of the Kalevala in the sense that he created the plotline for the story. He edited out what he felt was unnecessary, took pieces from here and there, and forged everything together to fit in one book.

Elias Lönnrot was a Fennophile through and through. When he was traveling around Finland and the surrounding areas from the 1820s to the 1840s, writing down old folklore, the goal was nothing more and nothing less than creating Finland – a nation that could one day become independent. And how could it not, when it had such a noble past, as the Kalevala’s beautiful and skillful poems indubitably proved.

But that visionary national awakening didn’t require quite all of the material Lönnrot collected. And certainly not the most obscene of the poems – of which there was no shortage!

Fortunately, Lönnrot was a scientist to the core. He was a doctor, researcher, journalist, linguist and botanist. So when he crisscrossed the deep forests of eastern Finland, Estonia and Karelia, for the most part on foot, he fastidiously made note of everything he found.

A scientist doesn’t blush, so presumably Lönnrot didn’t either – or at most, just a little – when he recorded this love spell from Ilomantsi in 1828:

Ahoy cock, arise cock, Here on this lass’s cunt, Here on this child’s hips, Here on this bird’s tail!

Set the cocks plowing, The balls clanging,

The sacks squealing, Free the cocks from their bonds, The furry shafts from their shackles.

Lönnrot wasn’t the only one collecting folk poetry. At one point, there was a whole slew of them in the forests of Karelia, and the competition was fierce. It was hard to beat Lönnrot, however, who collected tens of thousands of verses.

The juiciest of them weren’t used, but they were stored through the decades in the back room of the Finnish Literature Society, where researchers were able to access them.

About ten years ago, these sex poems were compiled into a little book called Tupa ryskyi, parret paukkui (The House is Rocking, the Joists are Popping).

The book contains birth poems for genitalia, odes, spells and satirical poems as well as various sexually suggestive songs.

The poems depict the joy of sexuality, longing for sex when you aren’t having it, passion, love magic and all the other things that we associate with sex even today. You would think that if more of these poems were taught in school, even the youth would be more interested in the old poetic traditions.

For example:

Oh, what a bother

Not having a wife,

Stuck with a cock

Always standing upright.

(Collected by Lönnrot in Karelia in 1837)

In general, both the Kalevala and Lönnrot have left a somewhat dusty image for posterity. It’s a shame, because the former is interesting (though the language is difficult for the modern reader), and the latter was an extremely multifaceted and talented man.

For example, Lönnrot’s industriousness was not limited to nation-building and science (he wrote no fewer than four doctoral theses), but he was a man of enlightenment from top to toe.

As a doctor, Lönnrot was concerned about the scourge of alcohol, and he founded Finland’s first temperance society in 1834. Even then, he showed the same open-mindedness as when collecting erotic poems.

In the first volume of Lönnrot’s selected works, he describes the rules of his temperance club:

Each day, club members are allowed three drinks with meals, except if fish is being eaten – in that case, an additional drink is permitted. You can start the morning with a drink, and if desired, drinks are also appropriate at 11 a.m. and 6 p.m. Two toddies in the evening is the absolute maximum, but a third is okay if it’s taken with a piece of sugar. The consumption of wine and beer is not restricted in any way.

The rules of the club were so well thought-out that the majority of Finns still follow the key principles of Lönnrot’s temperance ideology today. s

Lusto’s exhibitions, events, work demonstrations and theme days provide a diverse and illustrative insight into the significance of forests in the life of Finns

New core exhibition The Land of Forestfulness opens 17.5.2024.

kertoo 1940-41 ja 1944 tapahtuneesta itäisen maarajan linnoittamisesta ja Salpalinjasta, joka lähtee Virolahdelta. Museoon kuuluvat sisänäyttely ja ulkoalueen linnoituskohteet, tykkipuisto sekä Hyvän Mielen Polku!

Luontopolut ja retkeilyreitit

• Tuntemattoman Polku (4,5 km)

• Erämaan Polku (4,3 km)

• Salpapolku (43 km)

• Avoinna 1.6.-31.8. joka päivä klo 10-18 •

• Touko- ja syyskuussa pe klo 10-18, la klo 10-16 •

• Vaalimaantie 1318, 49960 Ala-Pihlaja •

www.bunkkerimuseo.fi

Lustontie 1, 58450 Punkaharju lusto.fi

Lustontie 1, 58450 Punkaharju lusto.fi

The exhibition of Lappeenranta Art Museum called Normal drinks and our everyday bread shows how visual art and gastronomy are linked to each other and especially how the culinary culture of Finland is displayed in art over the years. The overall theme of the exhibition is food, drink and culinary culture in the history of Finnish visual arts from the early 19th century to the present day.

Food and drink are an inevitable part of life and therefore part of everyday culture but, on the other hand, gastronomy and culinary habits are also very closely related to parties and celebration. However, food, drinks and culinary culture are not only about eating and drinking. Food products are, for instance, farmed, hunted, fished, gathered, prepared, cooked, served or delivered before one eats and consumes them. The exhibition aims to illustrate various phenomena related to food and drink as viewed through Finnish visual arts.

The food and drink as such have traditionally been portrayed in various still lives like in the early 20th century painting by Alfred Finch (1854–1930) which depicts cherries, cauliflower, carrots, potato and pots used in kitchen. A contemporary painting titled Last Croissant (2019) by Tiitus Petäjäniemi (b. 1983) depicts in a somehow humorous way coffee drinking in a meeting room when there is only one croissant is left. Mikko Haiko (b. 1984) has in his photographs like Hunters drinking coffee and Lemi documented both hunters and the process of elk hunting in Lemi.

These examples already show that the subjects and themes of the artworks in this exhibition are diverse. The themes include the acquisition and production of ingredients – such as agriculture, hunting, gathering and fishing – and restaurants, cafés, culinary culture(s), food trends, and ethical issues related to food and drink, insofar as these themes have been dealt with in Finnish visual arts. The exhibition also features various techniques and styles ranging from traditional paintings to photography, video and installations.

The exhibition has been compiled of the Lappeenranta Art Museum’s own works, works borrowed from other museums, private organisations as well as contemporary artists.

You can get to know the secrets of South Karelian culinary culture at the feast table (pitopöytä in Finnish) of the new permanent exhibition

The Story of South Karelia at the South Karelia Museum. South Karelia is located on the border of the eastern and western cultures, and influences from both Sweden and Russia are visible in the culinary tradition of our region. The South Karelian food culture has many features in common with the Karelian Isthmus, the North Karelia and the Savo region. The preparation of various pies and casseroles is strong part of our culinary tradition.

South Karelian culinary culture in this exhibition is displayed with the help of the museum's artefact and photo collections. The objects tell about both change and permanence related to the food economy. Over the decades and centuries, the traditional wooden tools of the dairy industry have changed to industrially produced glass and plastic dishes and tools, but the tossing bowls (a special bowl used in kneading the Joutseno-style rieska bread) and traditional pie rolling pin associated with baking have remained similar throughout the ages. The pictures in the exhibition show, among other things,

Einari Levo, Market Seller, 1973, Collection of the Lappeenranta Art Museum. Photo: The Museums of Lappeenranta. Tiitus Petäjäniemi, Last Croissant, 2019, Collection of the City of Mikkeli. Photo: Paula Hyvönen / Mikkeli Art Museum.

South Karelia is located on the border of the eastern and western cultures.

working in the fields, picking mushrooms, going fishing, and drinking coffee. In addition to food culture, the exhibition offers an opportunity to learn about South Karelian hospitality and the market square traditions of the province.

The exhibitions mentioned above are linked to the Saimaa European Region of Gastronomy year, which will be celebrated

LAPPEENRANTA ART MUSEUM

Kristiinankatu 8-10, The Fortress of Lappeeranta

Exhibitions:

3 February – 12 May Power of Art – the story of one family

1 June – 1 September Normal drinks and our everyday bread (The museum is closed during a renovation 2 Sep – 13 Dec)

14 December 2024 – 16 February 2025 Katri Kuparinen, Tiina Marjeta and Juan Kasari

SOUTH KARELIA MUSEUM

Permanent exhibition The Story of South Karelia

9 March – 2 June At Your Service!

19 June – 22 September 2024 Forests of the North Wind

12 October 2024 – 9 March 2025 The Railway Navvies

throughout 2024. Three regions in eastern Finland form the Saimaa European Region of Gastronomy region. In the jubilee year, the region will be the centre of European food and cultural tourism, and the aim is to link food with art and culture in surprising and interesting ways. The official website of the jubilee year is available at www.tastesaimaa.fi. s

Opening hours

Winter season

2 Jan – 2 June and 20 Aug – 29 Dec, Tues – Sun 11 am – 5 pm

Summer season

3 June – 18 Aug, Mon – Fri 10 am – 6 pm and Sat – Sun 11 am – 5 pm

See exceptions in opening hours and other additional information on our website: www.lappeenranta.fi/en/culture-and-sports/ the-museums-of-lappeenranta

The Museums of Lappeenranta also include the Cavalry Museum and the Wolkoff House Museum.

Roasting Särä (lamb meat and potatoes), in traditional wooden Särä-bowl in Lemi, 1979. Photo: Väinö Putkonen / The Museums of Lappeenranta photo archive. Rotinat, traditional baby welcoming celebration at Hapola estate in Taipalsaari, 1920s. Word rotinat refers to the baked and cooked gifts that were bought to the celebration. Photo: Unknown photographer / The Museums of Lappeenranta photo archive.

“Would you like to see the rooftop terrace?”

“I would love to.”

The year was 2012, and I had been invited as a guest to a literary festival in Algiers, the capital of Algeria. I arrived at my hotel in the evening alone, and the receptionist offered to show me around. I followed him up the narrow stairs to the rooftop terrace, which offered a broad view of the sunset-gilded city. There on the terrace, the receptionist suddenly put his arms around me and tried to kiss me.

I froze. I was pregnant, my belly already clearly visible under my dress. The first thing I thought of was the baby: what would happen if we got into a physical fight? I forced myself to stay calm. I broke away from his grip and told him I was tired from the trip and wanted to go to my room to rest.

In the room, I started shaking. The lock on the door was so flimsy that I suspected it could be opened with a hairpin. With a chest of drawers and chairs, I built a barricade in front of the door and placed two water glasses from the bathroom on top, which would fall with a clatter if someone tried to push the door open.

The unpleasant situation on the rooftop terrace has remained a strong memory for two reasons: because I was pregnant, and

Written by eLina hirvonen transLated by Christina saarinenbecause it took place in a hotel, and I’ve loved hotels for as long as I can remember.

More accurately, I love the idea of a hotel. For me, a hotel is first and foremost a place where it is possible, in a neatly made bed, in a space encompassed by clean-smelling pillows, to escape one’s own life for a while.

I’ve spent the night in many different places during my travels, from a tent on the roof of a car to the lobby of a police station. These overnight spots have always been interesting, but when it comes to hotels, it’s not just about the lodging, but something bigger: a temporary escape from your own world.

I’ve checked into hotels exhausted, in love, or heartbroken, when I’ve been looking for a place to recover, and when I’ve longed for a space for my own thoughts, away from everyday life. At best, even a single night in a hotel can open up a space in one’s day-to-day life from which it is possible to see beyond the usual, where there is room for what is most important: imagination, silence, play and dreaming.

I have never understood people who complain that hotels are impersonal. For me, that’s the whole idea. When you check into a hotel, especially when alone, you have the chance to momentarily escape your own personality as well.

In the end, the most important thing in a hotel is not what it offers me, but what it offers its environment and employees.

One of my most intense memories related to hotels is the night I spent in a hotel in Oulu at the end of August 2021. The Taliban had taken over Kabul a couple of weeks earlier, and I had spent the previous days trying to get my Afghan friend and his family to safety.

When my friend’s family was finally safe, I went on a work trip and spent the night alone in a hotel. I went swimming, took a sauna, did yoga and read the work of a female Afghan writer. I hardly spoke to anyone for a day. That nigh ät alone in a hotel helped me make the return from the days filled with fear to a life that could once again consist of more mundane things than a friend in mortal danger.

I am very aware that the opportunity to spend nights in hotels is a rare privilege. That’s why, in the end, the most important thing in a hotel is not what it offers me, but what it offers its environment and employees. A little while ago, I visited an expensive hotel where an important detail caught my eye: the employees wore ill-fitting uniforms. They looked uncomfortable in their clothing, and I had to wonder what kinds of conditions they were otherwise working under. Were they valued? Were the working climate, pay and terms of employment as they should be? The doubts gnawed at me even more strongly than the harassment I had experienced on the rooftop terrace of the Algerian hotel.

I love hotels, but more important than that is fairness and valuing people. Even the loveliest hotel loses its charm immediately if the people who work there are not treated well. s

Elina Hirvonen is an award-winning author and documentary filmmaker who would like to spend the rest of her life in the world’s best hammams under clouds of soap bubbles.