odern Success Issue #2 Spring 2013

Considerations for UW-Madison Students

!

yone else

and ever

FREE! T ake C opy D istribute

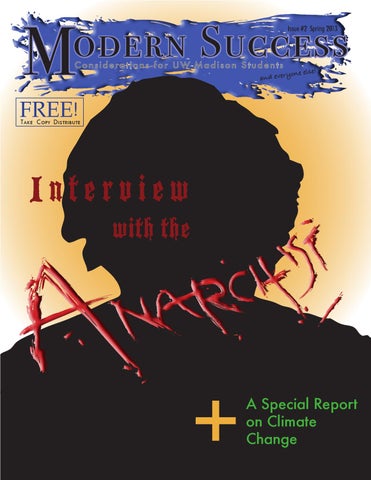

Interview

with the

+

A Special Report on Climate Change

odern Success Issue #2 Spring 2013

Considerations for UW-Madison Students

!

yone else

and ever

FREE! T ake C opy D istribute

Interview

with the

+

A Special Report on Climate Change