8 minute read

From Bishop to Pope: A Timeline

From B ISHO P to Pope

A T IMELINE

by TOM WENGER

CIRCA 251

In response to Pope Stephen’s appeal to Matthew 16 to justify his authority as “the rock” on which the church is built, Cyprian of Carthage argues:

“Certainly the other Apostles also were what Peter was, endued with an equal fellowship both of honour and power; but a commencement is made from unity, that the Church may be set before us as one; which one Church, in the Song of Songs, doth the Holy Spirit design and name in the Person of our Lord.” 2

CIRCA 180

Irenaeus pens Against Heresies and describes Rome as a faithful preserver of apostolic doctrine, but there is no mention of papal primacy:

“For it is a matter of necessity that every Church should agree with this Church on account of its preeminent authority... inasmuch as the apostolical tradition has been preserved continuously by those [faithful men] who exist everywhere.” 1

CIRCA 381

Refuting Arianism, Ambrose argues that Matthew 16 established faith in the divinity of Christ, and not Peter’s authority, as the foundation on which the church is built:

“That is the primacy of his confession, not of honour; the primacy of belief, not of rank. This, then, is Peter who has replied for the rest of the Apostles; rather before the rest of men. And so he is called the foundation, because he knows how to preserve not only his own but the common foundation.…Faith, then, is the foundation of the Church, for it was not said of Peter’s flesh, but of his faith, that ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail against it.’” 3

CIRCA 417

The African General Synod at Carthage forbids appeals to Rome. In 417, Pope Zosimus reverses Pope Innocent I’s condemnation of Pelagius, declaring him to be orthodox and chastising the African bishops for condemning his teachings. In response to this, the African bishops hold the African General Synod at Carthage and reject the pope’s declaration, adding in canon 17:

“If priests, deacons and inferior clerasmuch as even among the blessed apostles…there was a certain distinction was equal yet it was given to one [i.e., St. verge toward Peter’s one chair, and nothing anywhere should be separate from

ics complain of a sentence of their own bishop, they shall, with the consent of their bishop, have recourse to the neighboring bishops who shall settle the dispute. If they desire to make a further appeal, it must only be to their primates or to the African Councils. But whoever appeals to a court on the other side of the sea [Rome] may not again be received into communion by

446

Leo the Great asserts one of his many bold claims to papal primacy:

“Bishops indeed have a common dignity, but they have not uniform rank, inof power. While the election of all of them Peter] to take the lead of the rest.…[T]he care of the universal Church should conanyone in Africa.” 4

its head.” 5

451

The Council of Chalcedon rejects Leo’s claims of primacy and instead bases Rome’s rank on the fact that it is the capital city of the empire:

“Following in all things the decisions of the holy Fathers…we also do enact and decree the same things concerning the privileges of the most holy Church of Constantinople, which is New Rome. For the Fathers rightly granted privileges to the throne of old Rome, because it was the royal city. And the One Hundred and Fifty most religious Bishops, actuated by the same consideration, gave equal privileges to the most holy throne of New Rome, justly judging that the city which is honoured with the Sovereignty and the Senate, and enjoys equal privileges with the old imperial Rome, should in ecclesiastical matters also be magnified as she is, and rank next after her.” 6

588

Gregory the Great rejects the notion that anyone, the Roman bishop included, should ever be called “Universal Bishop”:

“But not one of my predecessors has ever consented to use this so profane a title; since…if one Patriarch is called Universal, the name of Patriarch in the case of the rest is derogated. But far be this, far be it from the mind of a Christian, that any one should wish to seize for himself that whereby he might seem in the least degree to lessen the honour of his brethren. While, then, we are unwilling to receive this honour when offered to us, think how disgraceful it is for anyone to have wished to usurp it to himself perforce.…Certainly Peter, the first of the apostles, himself a member of the holy and universal Church, Paul, Andrew, John,— what were they but heads of particular communities?… Now I confidently say that whosoever calls himself, or desires to be called, Universal Pope, is in his elation the precursor of Antichrist, because he proudly puts himself above all others.” 7

800

On Christmas Day, Pope Leo III crowns Charlemagne King of the Holy Roman Empire, cementing the link between the papacy and the political sphere.

“[Thus in] one brilliant gesture Pope Leo established the precedent, adhered to throughout the Middle Ages, that papal coronation was essential to the making of an emperor, and thereby implanted the germ of the later idea that the empire itself was a gift to be bestowed by the papacy.” 8

1075

Pope Gregory VII issues his Dictatus Papae, which includes the following edicts:

2. That the Roman Ponti alone is rightly to be called universal. 8. That he alone can use the Imperial insignia. 9. That the Pope is the only one whose feet are to be kissed by all the princes. 10. That his name alone is to be recited in all the churches. 12. That he may depose emperors. 17. That no chapter or book may be regarded as canonical without his authority. 19. That he himself may be judged by no one. 9

1870

During the deliberations of Vatican I, Pope Pius IX rebukes Cardinal Guidi for his opposition to the doctrine of papal infallibility by shouting:

“I am tradition! I am the Church!” 11

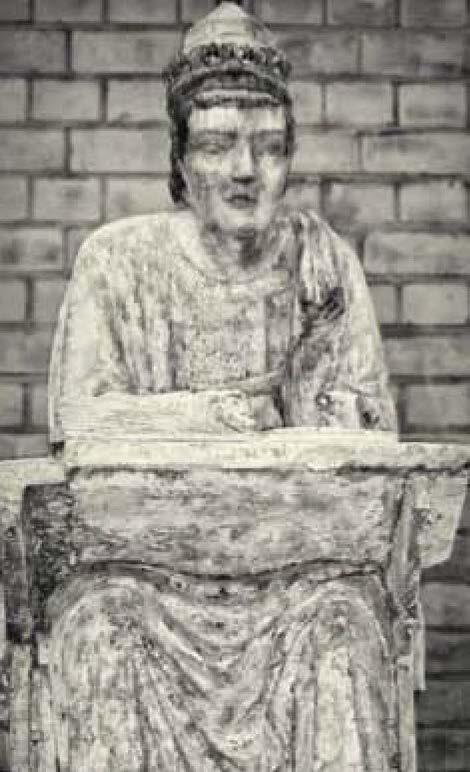

CIRCA 1200

Innocent III consolidates and defines both the ecclesiastical and political primacy of the Roman See and under his reign papal primacy truly reaches its zenith. He says of himself:

“To me is said in the person of the prophet, ‘I have set thee over the nations and over kingdoms, to root up and to pull down, and to waste and to destroy, and to build and to plant’ (Jer 1:10). To me is also said in the person of the Apostle, I will give to thee the keys of the Kingdom of Heaven.…You see then who is the servant set over the household, truly the vicar of Jesus Christ, successor of Peter, anointed of the Lord, a God of Pharaoh, set between God and man, lower than God, but higher than man, who judges all and is judged by no one.” 10 NOTE OF INTERES T

Catholic historian Johann Joseph Ignatz von Döllinger—who, according to his contemporary Philip Scha, was “regarded as the foremost Roman Catholic Church historian”—assessed the significant evolution that the doctrine of papal primacy underwent after the first six centuries of the church. He concluded:

The Tridentine profession of faith, imposed on the clergy since Pius IV, contains a vow never to interpret Holy Scripture otherwise than in accord with the unanimous consent of the Fathers—that is, the great Church doctors of the first six centuries, for Gregory the Great, who died in 604, was the last of the Fathers; every bishop and theologian therefore breaks his oath when he interprets the passage in question (Mt 16) as a gift of infallibility promised by Christ to the Popes. 12

Tom Wenger is associate pastor at Evangelical Presbyterian Church of Annapolis (PCA) in Annapolis, Maryland.

1 Irenaeus, “Against Heresies,” in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, ed. Alexander

Robertson et al (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 1994), 3:1–2. 2 Cyprian, “On the Unity of the Church,” in A Library of the Fathers of the

Holy Catholic Church, Treatise V (Oxford: Parker, 1842), ch. 31. 3 Ambrose, The Fathers of the Church, The Sacrament of the Incarnation of

Our Lord, IV.32—V.34 (Washington DC: Catholic University, 1963), 230–31. 4 Quoted in Charles Joseph Hefele, A History of the Councils of the Church from the Original Documents (Edinburgh: T & T Clark, 1896), 2:461. 5 Leo the Great, “Letter XIV, To Anastasius, Bishop of Thessalonica,” trans.

J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (London: Continuum, 2000), 420. 6 “Council of Chalcedon, 451: The Seven Ecumenical Councils” in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, ed. Alexander Roberts et al, 2nd ser. (Peabody,

MA: Hendrickson, 1994), 14:287. 7 Gregory the Great, “Epistles,” in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, 5:18, 43; 7:33. 8 Brian Tierney, The Crisis of Church and State: 1050–1300 (Englewood

Clis, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1964), 18. 9 Quoted in Tierney, 49–50. 10 Quoted in Tierney, 131–32. 11 Quoted in Roberto de Mattei, Pius IX, trans. John Laughland (Herefordshire, UK: Gracewing, 2004), 144, n. 39. 12 Johann Joseph Ignatz Von Döllinger, The Pope and the Council (Boston:

Roberts Brothers, 1870), 76. Note: this work is usually published under the pseudonym “Janus”; see also Philip Scha, History of the Creeds of Christendom (repr. Grand Rapids: Baker, 1998), 193, n. 1.