40 minute read

Going to Church with the Reformers

by MICHAEL S. HORTON illustration by STEVE WACKSMAN

GOING TO C HUR C H W I T H THE R EFORMERS

It doesn’t really matter in the final analysis whether Luther and Calvin would find the average evangelical church in America today more or less congenial than Rome. Yet it does suggest an interesting point of departure as we think about whether the Reformation question is a live question today.

Many of us were raised to believe that we had all the answers (whatever they were) and that Roman Catholicism believes in Mary and the pope rather than in Jesus and the Bible, in salvation by works rather than grace. And yet, as the surveys demonstrate, we didn’t really know what we believed or why we believed it—at least beyond a few slogans. If one asked the question in the correct form, we could possibly give the right answer to some of the big ones. However, a rising generation now is indistinguishable in its beliefs from Mormons, Unitarians, or those who check the “spiritual but not religious” box. We’re told that “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism” is the working theology of most Americans, including evangelicals. So when it comes to authority and salvation—the two issues at the heart of the Reformation’s concern—Protestantism today (mainline and evangelical) seems increasingly remote from anything that the Reformers would have recognized as catholic and evangelical faith and practice.

In my “cage phase” (when emerging Reformed zealots should be quarantined for a while), I read from a sixteenth-century confession the section on grace and justification. The audience was a rather large group of fellow students at a Christian college. “Do you think we could sign this statement today,” I asked. Several replied, “No, it’s too Calvinistic.” That was interesting, because I was quoting the Sixth Session of the Council of Trent, which anathematized the Reformation’s teaching that justification was by Christ’s merits alone, imputed to sinners through faith alone. I didn’t quote the whole section, but only the part that a±rmed that we are saved by grace and that our cooperation in the process of salvation—even our will to believe—requires God’s grace. You have to dig beneath the sweeping slogans and generalizations; it’s precisely in the details—where many eyes glaze over—that the massive dierences between Rome and the Reformation appear.

C O MING TO TERMS WITH THE CHURCH’S PA S T

Pelagianism—the view that we are saved by our own choice and eort apart from grace—was condemned by several ancient church councils and bishops of Rome. Even semi-Pelagianism—the view that we make the first move by free will and then grace assists us—was also condemned. For example, the Second Council of Orange in 529 even anathematized those who say that we’re born again by saying a prayer, when it is only God’s grace that gives us the will to pray for Christ’s mercy. Yet the Latin Church always struggled with the Pelagian virus in varying degrees. Medieval leaders such as Archbishop Thomas Bradwardine wrote treatises titled “Against the New Pelagians.” Thomas Aquinas emphasized the priority of God’s grace in predestination and regeneration. Luther’s own mentor and head of the Augustinian Order in Germany, Johann von Staupitz, wrote “A Treatise on God’s Eternal Election” in which he expressed concern that free will and works-righteousness had begun to undermine faith in God’s grace in Christ. By the time of the Reformation, popular piety was corrupted by countless innovations and superstitions. Luther was first aroused to arms by the arrival of a preacher with papal authority to dispense indulgences (time o in purgatory) for money that would help build St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. The Reformation couldn’t be dismissed, precisely because it resonated with so many who knew that Rome had drifted far from its ancient moorings into myriad corruptions. Awakened by the new biblical scholarship, many of Europe’s leading Renaissance humanists became convinced that the Reformers were correct in their interpretation and application of Scripture to the church’s condition.

The Council of Trent, which anathematized the Reformation’s convictions, a±rmed the importance of grace going before all of our willing and running. Nevertheless, it condemned the view that, once regenerated by grace alone in baptism (our first justification), we cannot merit an increase of justification and final justification by our works. Trent said in no uncertain terms that Christ’s merits are not sufficient for salvation. Everything turned on dierent understandings of grace:

ROME God’s medicine infused to help us cooperate

VS

REFORMATION God’s favor toward us in Christ

This in turn resulted in two dierent doctrines of justification:

ROME A process of inner renewal

VS

REFORMATION A declaration based on the imputation of Christ’s righteousness alone

PELAGIAN REVIVALISM IN AMERICA

As Presbyterian theologians Charles Hodge and B. B. Warfield pointed out, the explicit convictions of the famous evangelist of the Second Great Awakening, Charles G. Finney, were much further down the Pelagian road than Rome. Finney not only denied justification through faith alone in Christ’s merits alone. He based this on a rejection of original sin, the substitutionary atonement, and the supernatural character of the new birth. Consequently, his “new measures”— i.e., methods whose only criterion was whether they were “fit to convert sinners with”—replaced the divinely ordained means of grace, and his “protracted meetings” (revivals) radically altered the shape of most Protestant services and ministries in America. As Arminian theologian Roger Olson has pointed out, much of evangelical preaching today isn’t really Arminian but is closer to Pelagianism. The result is a distinctly Protestant kind of hazy moralism (works-righteousness) and an equally hazy notion that somehow Rome believes we’re saved by works rather than grace. It can be a fatal combination, especially when people realize that Rome does in fact believe in original sin and the necessity of grace—more in fact than many who call themselves evangelicals.

TOO CATHOLIC? WELCOM E TO THE R E FO RMATION

Now we see many evangelicals being attracted to the Reformation’s emphases, discovering a tradition that is both catholic and evangelical without many of the trappings of evangelicalism. As their encounter with the Reformation widens beyond election and justification, they bump into views that sound at first “too Catholic.” Sola scriptura 44

(by Scripture alone) doesn’t mean that creeds and confessions and the decisions of church councils and assemblies don’t have any authority. Although Scripture alone has magisterial authority, these faithful summaries of Scripture nevertheless have a ministerial authority. Sola gratia (by grace alone) is not set over against the regular ministry of preaching and the sacraments; rather, these are the means of grace through which the Spirit delivers Christ with all of his benefits. It’s not Roman Catholic, to be sure, but to many evangelical brothers and sisters it sounds “too Catholic.” Reformed and Lutheran churches include the children of believers in baptism, and liturgy, orders and o±ces, discipline, and the accountability of local churches to each other in wider assemblies. These characteristics of Reformed ecclesiology also strike many evangelicals, again, as “too Catholic.”

And that makes some sense. After all, despite its critique of the magisterial authority assigned to the pope o±cially at the Council of Trent, the Reformation diers at least as much from the freelance ministry of “anointed” preachers who act like popes, only without any accountability to the magisterium.

Churches of the Reformation not only challenged the hierarchical government of the Roman Church, but also the sects that followed their own self-appointed prophets. Yes, said the Reformers, individual members and ministers are accountable to the church in its local and broader assemblies. God doesn’t speak directly to individuals (including preachers) today, but through his Word as it is interpreted by the wider body of pastors and elders in solemn assemblies. Tragically, evangelical hierarchies today are more prone to authoritarian abuses and personal idiosyncrasies than one finds in Rome.

R E FO RMATION CHURCHES AND R O M E

Dislodged from confidence in Pastor Bob and the givens of the evangelical subculture, Christians need to realize that the Reformation was, well, a reformation and not a revolution or “do over.” Luther was not the founder of a new church, but an evangelicalcatholic reformer. As expressed in the title of one of the great works of Elizabethan Puritanism—William Perkins’s The Reformed Catholic—there is a deep continuity with the undivided church.

On the Roman Catholic TV network (EWTN) recently, Fr. Pacwa interviewed a professor who had graduated from Wheaton and Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. Becoming more interested in the Reformation, the professor pursued a PhD at the University of Iowa focusing on the theology of Calvin. The title of this segment was “How Calvin Made Me a Catholic.” The Reformers were eager to show their connection to the pre-Reformation church. They did not believe that the church had basically gone underground—much less extinct— between Paul and Luther. Rather, they argued that a gradual decay had been accelerated by recent emphases and innovations that needed to be corrected. Calvin is recognized by Roman Catholics and Protestants alike as a scholar of the early fathers, and his Institutes and commentaries are replete with citations from writers of the East and the West. The great theologians of Reformed and Lutheran orthodoxy engaged the ancient and medieval theologians as their own, yet always subject to critique as well as approval on the basis of their interpretation of Scripture according to a shared confession. So I can understand why some evangelicals find the Reformation “too Catholic” or, weary of Protestantism in any form, look back to their “Reformation episode” as a gateway drug to the mysteries of Rome. For a long time now, American Protestants have defined their faith and practice in reaction against Rome. Now a growing number are defining their faith and practice in reaction against evangelicalism. “If the Reformers were alive today, they’d be Roman Catholic before they would join an evangelical sect.” I’ve heard that sentiment on more than one occasion.

WHICH CHURCH WOULD THE R E FO RME RS JOIN?

However, the men and women who risked their lives in the sixteenth century to defend the su±- ciency of Scripture and the sufficiency of Christ would refuse the false choice between a chaotic Protestantism and a Roman Catholicism that still maintains the theology of Trent. It would be perverse to imagine that Luther or Calvin would find Rome more acceptable today than it was in their day. Even in the much-publicized “Joint Declaration on Justification,” it was the mainline Lutherans who surrendered their confessional convictions; Rome did not change any of its o±cial positions. And in any case, the Vatican has made it clear that this consultation in no way has any magisterial weight.

Is the growing interest in Reformation theology among younger evangelicals going to mean that, for some, Geneva, Wittenberg, and Canterbury will be a rest stop before moving on to Rome or Antioch? I suspect there will be this kind of trend of some sort in the future. We dare not treat those struggling with these issues among us as “necessary casualties,” a minimal loss compared to net gains. Pastoral love, wisdom, and patience will be more valuable than gold. There are real questions here—existential, exegetical, theological, and practical, with real lives being aected. It’s not a time for us to grandstand or to shoot from the hip with speculations about peoples’ motives or character. Rather, we should strive to make a persuasive case, leaving the results to the Spirit of truth.

Michael S. Horton is editor-in-chief of Modern Reformation.

Feed Your Inner Theology Geek.

VISIT THE STORE.

Be sure to check out White Horse Inn’s online store. In addition to books, you’ll find mp3s, study kits, and videos for sale—everything you need to keep the conversation going oine.

book reviews

50

52

Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books BY MICHAEL J. KRUGER Crossway, 2012 362 pages (hardback), $30.00

This is a massively important and timely book. We face an unexpected foe today that, unless reversed, will harm the evangelical gospel witness, perhaps even destroy that witness within the next generation or two. Admittedly, in pop culture, mass media, and the mainstream academy, the Bible (and therefore the gospel) seems to have lost all credibility. Since no one listens to Scripture or clergy because neither the Word nor the church seems to have any recognizable—let alone respected—authority, great have been the attacks against it. There are, in other words, attacks on the Christian canon of Scripture from without.

But a very present enemy from within evangelicalism from within evangelicalism is biblicism; in other words, is biblicism; in other words, fundamentalist theories and fundamentalist theories and misuses of the Bible’s content, misuses of the Bible’s content, purpose, and authority. Mi purpose, and authority. Mi chael Kruger’s Canon RevisitCanon Revisit- ed is a serious apologetic that is a serious apologetic that is both a bulwark against at is both a bulwark against at tacks from without and an oftacks from without and an offensive measure over against fensive measure over against naive and untenable doc naive and untenable doc trines of Scripture and canon trines of Scripture and canon formation arising from within American Chris formation arising from within American Chris tianity. As such, this book is required reading for tianity. As such, this book is required reading for all pastors and priests, church elders and clerics, as well as seminarians and learned laypersons. It is not so much a weapon of mass instruction against Roman Catholic or Dan Brown accounts of canon formation, as against Bible-belt biblicism that has become the whipping boy of cable TV talk show hosts.

Biblicism typically resorts to practical fideism in its phobic attack on the Bible. In the biblicist

scheme, the canon “just is.” Kruger says that not only will this not do, but it’s also dishonest in addition to being impossible. The issue of canon formation is complex and sophisticated, but nonetheless imperative. Pollyanna positions have no place in the church and neither does prejudicial caricaturing. The discussion about canon necessarily includes contributions from historical-criticism and resources extrabiblical sources of authority, but both are substantially informed by the self-authenticating content and nature of Scripture.

Acknowledging the danger of categorization and reductionism, the author frames the discussion in terms of three frequently competing models of determining the canon: (1) the canon as community determined, (2) the canon as historically determined, and (3) the canon as self-authenticating. Kruger argues that these models, when competing, fail to adjudicate the evidence each oers in an honest spirit of liberal scholarship in spirit of liberal scholarship in the pursuit of truth and knowl the pursuit of truth and knowl edge. The issue is epistemo edge. The issue is epistemo logical. Historical-criticism logical. Historical-criticism has, on the whole, operated has, on the whole, operated with a perfunctory dismiss with a perfunctory dismiss al of the self-authentication al of the self-authentication model due to its worldview model due to its worldview commitments. Meanwhile, commitments. Meanwhile, evangelical biblicism has done evangelical biblicism has done virtually the same thing by de virtually the same thing by de nouncing higher-critical and nouncing higher-critical and even historically determined models as subver even historically determined models as subver sive of divine authorship. Ideological agendists sive of divine authorship. Ideological agendists may view these positions as antithetical, but within Kruger’s tripartite model they most certainly are not. There is a manifest need for the legitimate findings of each for a truly viable and coherent account of canon formation and scriptural authority.

In fact, it must be acknowledged, explains the author, that the historical-critical model is correct to remind us of the role of the Christian

community in the formation of the New Testament canon. When Jesus ascended, the New Testament didn’t immediately descend. There was a process, a progression to canon formation; yet not one without precedence, even a divinely ordained and orchestrated precedence. In other words, Kruger describes the genuine warrant for Christian belief in the divine origin and authority of Scripture, notwithstanding the circular nature of using Scripture to evidence Scripture’s origins and authority (after all, any clear-minded thinker will acknowledge that there is ultimately no escape for epistemic circularity when it comes to assessing fundamental sources of belief ).

Whether the revelatory nature of Scripture is embraced or not, a consideration of its content in light of warranted belief should be concomitant with all scholarly pursuits of the canon’s origins and authority. The content of New Testament Scripture is nothing other than the intrinsically authoritative gospel of Christ—the all-authoritative King’s new covenant Word—hence biblical authority and the Reformation’s sola scriptura a±rmations.

While the historical-critical model of canonization largely ignores the internal record and selfpresentation of Scripture’s own canonical nature, Kruger argues that this is a biased and unscholarly exclusion. Central to his research, then, is Scripture’s covenantal content and structure. Scripture itself sets the terms for how its own origins are to be investigated and explored with relation to canonicity. With extrabiblical parallels, the Old Testament shows us that God, by his redemptive activities, creates a covenant community. He then, writes Kruger, gives them documents that testify to that redemption and serve as a permanent, reliable, and holy transmittable record. As the author puts it: “It is not just the claim that these books are about Christ’s redemptive work in history but it is the claim that these books are the product of Christ’s redemptive work in history—that they are the outworking of the authority Christ gave to his apostles” (110). There are, therefore, three aspects to canon formation and recognition, rightly understood: (1) canon as reception (exclusive); (2) canon as use (functional); and (3) canon as divinely given (ontological).

The book is well ordered with two main parts (“Determining the Canonical Model” and “Exploring and Defending the Canonical Model”), subdivided into three and five chapters respectively, followed by a conclusion. Of special importance in Part 2 are the chapters on the apostolic origins of the canon (rooted, of course, in the oral tradition of the gospel), as well as so-called “problem” books and canonical boundaries.

Canon Revisited would have benefited from a more robust discussion and consideration of the place of liturgy as a vehicle of gospel preservation, transmission, and authority. The same could be said for other oral components woven into the New Testament (e.g., hymns, creeds, and so forth), as opposed to concentrating on gospel preaching. Other detracting features include the failure of Crossway editors to limit the endless, sometimes pedantic footnotes. Discerning readers will disapprove of some of his exegetical work. Additionally, the author’s representation of the authority of the oral tradition comes off muted as he steers away from certain (arguably plausible) aspects of Roman Catholic pronouncements on canonicity. All told, Michael Kruger has performed a major service for contemporary Christianity with a book that needs wide distribution.

John J. Bombaro (PhD, King’s College, University of London) is senior priest at Grace Lutheran Church, San Diego, and teaches at the University of San Diego. He is the author of Jonathan Edwards’s Vision of Reality (Pickwick, 2012).

Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of Heretics BY RUSS DOUTHAT Free Press, 2012 352 pages (hardcover), $26.00

The sight of heretics running rampant has always distressed the orthodox. Historically they’ve taken some extreme measures to restore their equanimity: wars of religion, the Spanish Inquisition, burnings at stakes, things like that.

In America, so the story goes, with the advent of modernity, democracy, and the First Amendment, it was determined that religion was too hot for the state to handle and that there should be free exercise of religion. This arrangement unleashed new scope for heretical binges unchecked by the power of sword, and heresy flourished like a green tree in its native soil. But this was considered preferable to violent religious carnage, and Americans are proud of their forefathers for having had the sense to make the religious zealots settle religious zealots settle their dierences without their dierences without weapons.

This is the story as it’s This is the story as it’s usually told, with the fo usually told, with the fo cus on the glorious benecus on the glorious benefits of religious freedom. fits of religious freedom. But New York Times New York Times col col umnist Ross Douthat umnist Ross Douthat would like to nuance would like to nuance this story in his book, this story in his book, Bad Religion: How We Bad Religion: How We Became a Nation of HerBecame a Nation of Her- etics. He believes that . He believes that while America has always fostered heretics, while America has always fostered heretics, these heretics used to react against a substantial these heretics used to react against a substantial orthodox Christian core. orthodox Christian core.

The minority heretics were good for religion, The minority heretics were good for religion, because heresy keeps orthodoxy on its toes. And

the situation as a whole was good for America, as the thus-enlivened orthodox, gathered in the institutional church, encouraged many social goods in its communal role, driving assimilation, and guaranteeing social peace. It also played a prophetic role, as “a curb against our national excesses and [as] a constant reminder of our national ideals” (16).

But now this ideal heresy/orthodoxy balance is being threatened by the decline of institutional orthodox Christianity and the insurgence of numerous heresies. Rather than becoming too irreligious or too religious, Americans are becoming too heretical, which leads to the loss of the orthodox core and its supporting social role, and instead results in cultural and financial woes. Douthat narrates the decline of orthodoxy over the past fifty years along with the concurrent decline in cultural health, and he provides a handy compendium of the most prevalent modern heresies and the havoc they wreak upon society. From this data he argues that more orthodox belief would be good for America, and that even unbelievers and skeptics should be ers and skeptics should be able to appreciate the ben able to appreciate the ben efits America once reaped efits America once reaped from its orthodox core. from its orthodox core. Douthat writes with Douthat writes with keen intelligence when keen intelligence when he outlines the current he outlines the current heresies and their perni heresies and their perni cious societal effects. If cious societal effects. If you want to be briefed on you want to be briefed on the heresies held by many the heresies held by many of your friends and neigh of your friends and neigh bors, I can recommend no bors, I can recommend no better resource. Douthat better resource. Douthat is less sharp, however, when he discusses or is less sharp, however, when he discusses or thodoxy. He attempts to make an instrumental thodoxy. He attempts to make an instrumental argument for orthodox Christianity, which is argument for orthodox Christianity, which is di±cult to do without reducing orthodox Chris di±cult to do without reducing orthodox Chris tianity to a simple tool. An instrumental version

of Christianity, sadly, is by definition no longer orthodox. It’s difficult terrain to navigate. Douthat readily acknowledges that Christianity must be sought for its own sake: “To make any dierence in our common life, Christianity must be lived—not as a means to social cohesion or national renewal, but as an end unto itself ” (293). But he struggles throughout the book to resist treating orthodoxy as a tool for political flourishing rather than the supernatural, stumbling-block-to-the-Jews and foolishness-to-the-Greeks kind of religion that it is.

The struggle to describe Christianity’s social benefit without reducing it to those benefits is apparent in his definition of orthodoxy. He argues that orthodoxy recognizes that reality is complex, while heretics often try to rationalize and streamline doctrines they can’t explain, like the incarnation, leading to a flattened view of the world. He goes on to define orthodoxy in this way: “What defines this consensus [of orthodox Christian belief ], above all—what distinguishes orthodoxy from heresy, the central river from the delta—is a commitment to mystery and paradox” (10). This is an odd way to put it, because while believing in mysteries and paradoxes might help you believe in a more complex world, they have no inherent value in themselves. They are valuable only if they are true and help to explain reality as it actually is. Douthat’s indirectness about Christianity’s truth-claims might make for an instrumental argument that is more appealing to unbelievers, but it portrays orthodoxy in a manner less than accurate. The struggle continues when Douthat addresses the way the church needs to think of itself in relation to the world. For example, he writes,

For a fleeting historical moment [the Civil Rights movement], it seemed as though the Christian churches might not have to choose between becoming religious hermit kingdoms or the spiritual equivalents of Vichy France. Instead, they might become something more like what the Gospels suggested they should be: the salt of the earth, a light to the nations, and a place where even modern man could find a home. (54)

In this quote he confuses being salt and light with the ability to eect certain social change. In

order to be salt and light, churches need to preach the Word boldly and administer the sacraments rightly, and Christians need to love their neighbors. Then they will be su±ciently salty and bright regardless of the sociopolitical outcome.

Douthat makes similar missteps elsewhere in the book, but at the very end he oers an encouraging proposal: get thee back to church. He writes, “Anyone who seeks a more perfect union should begin by seeking the perfection of their own soul. Anyone who would save their country should first look to save themselves” (293). That’s still phrased a bit too instrumentally, because of course saving your own soul is no guarantee that your country will be saved, but he does at least get the order right. Far better to save your soul and forfeit the whole world than the reverse. And should the world benefit because your soul is saved, praise the Lord for his bountiful mercies.

Anna Speckhard (BA in Political Science, Geneva College) is currently working on a Master of Arts in biblical studies at Westminster Seminary California. She has written for The Institute on Religion and Democracy and contributed to Social Justice: Transforming Lives in Need (The Heritage Foundation, 2009).

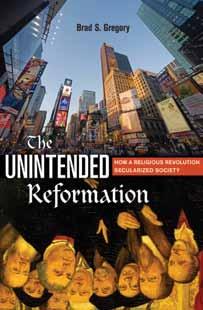

The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society BY BRAD S. GREGORY Belknap Harvard, 2012 592 pages (hardcover), $39.95

Secularism, pluralism, individualism, freedom, rights, toleration—whatever. In his book, The Unintended Reformation, Notre Dame professor of history Brad Gregory provides a provocative examination of the moral decline of modern society. Troubled by the pluralism and secularism surrounding him, he argues that the Reformation that the Reformation produced a profound produced a profound shift in attitudes to shift in attitudes to ward truth and ethics. ward truth and ethics. Starting with the Middle Starting with the Middle Ages and proceeding Ages and proceeding to the twenty-first cen to the twenty-first cen tury, Gregory attempts tury, Gregory attempts to offer a comprehen to offer a comprehen s i v e a n a l y s i s o f t h e s i v e a n a l y s i s o f t h e last millennium. Each last millennium. Each chapter examines one chapter examines one of six realms in which of six realms in which Gregory believes that the Gregory believes that the Protestant Reformation negatively impacted the Protestant Reformation negatively impacted the modern world: science, doctrine, society, morali modern world: science, doctrine, society, morali ty, economics, and knowledge. ty, economics, and knowledge.

First, he claims that the Reformation exclud First, he claims that the Reformation exclud ed the recognition of God’s work in the natural world by an insistence on a new way of understanding “being” (i.e., “being” is understood in a “univocal” way so that God and creation are the same qualitatively, differing only quantitatively), and by a rejection of sacramental realities (particularly transubstantiation). He holds that after the Reformation there was no longer any common framework to discuss God’s creative and providential role in the natural world as a result of this new philosophical understanding,

thus leading to the modern exaltation of science as fact and relegation of religion to mere opinion.

In the second chapter, Gregory argues that the Reformers’ insistence on sola scriptura produced only contradictory truth-claims among “Christians,” unlike the apparently unified and authoritative truth-claims of the Roman Catholic Church.

Next, he points out that the post-Reformation doctrinal differences understandably led to religious wars, which eventually produced civic toleration of religious differences in an attempt to escape further bloodshed. Gregory, however, is disturbed by this freedom of religion, believing dom of religion, believing that it limits the church’s that it limits the church’s control of souls and rele control of souls and rele gates the control of bodies to gates the control of bodies to the state, unduly separating the state, unduly separating the human unity of body and the human unity of body and soul. Moreover, he posits soul. Moreover, he posits that outward obedience to that outward obedience to the state became more im the state became more im portant than an inner love portant than an inner love for God and others. for God and others. Fourth, Gregory contends Fourth, Gregory contends that the Reformation ex that the Reformation ex changed “a substantive mo changed “a substantive mo rality of the good” for a “formal morality of rights” rality of the good” for a “formal morality of rights” (184). In other words, medieval Christians were (184). In other words, medieval Christians were rightly motivated to practice the virtues because rightly motivated to practice the virtues because the end was earning their salvation. But accord the end was earning their salvation. But accord ing to Gregory, the Reformed insistence on salvation by faith alone removed the teleological motivation for ethics, leaving society with arbitrary, nonreligious “rights.”

In his fifth chapter, Gregory deplores modern consumerist society and laments the lost medieval emphasis on self-denial. Because religion was not dictated by the state after the Reformation, Gregory concludes that religion was no longer a matter of public concern and that pursuit of material goods was the only remaining common

denominator. The previously condemned vices of greed and avarice became the new virtues of enterprise and economy.

Finally, Gregory argues that knowledge has become secularized, disintegrated from other branches of learning, and separated from any consequences it may have in action. He believes that theology was the unifying factor for medieval knowledge and that the Reformation removed theology from the rest of knowledge by setting up specialized schools and by constant doctrinal infighting. In his conclusion, he points out that all these threads are dierent aspects of the same complex story, and although knowledge of the past cannot change the present, it can illuminate the present.

Although The Unintended Reformation is learned and impressive in its breadth, this ambitious project left me with lingering historical and theological concerns. To be sure, the intellectual shifts Gregory describes did exist. But can the blame for such drastic changes be laid primarily at the feet of the Reformers? If the breakdown in philosophical metaphysics really began with Scotus and Ockham during the Middle Ages, as Gregory describes in chapter 1, why are the Reformers to blame? Later, he argues against the traditional distinction of the confessional Reformed and the radical Anabaptists, saying that these two groups should be considered together ideologically because they were united by their opposition to the Roman Catholic Church. But if both the Roman Catholics and the confessional Reformed had similar concerns about the radical Anabaptists, the direct ancestors of modern religious individualism, why does Gregory lump the confessional Reformed and the radical Anabaptists together? I agree with Gregory that history is a complex story, but I would further add that history is so complex that his decision to blame the Reformation frequently seems arbitrary.

Theologically, Gregory’s book is also troubling for the confessional Reformed, since it frequently serves today as an apology for the Roman Catholic Church. He finds that the Reformed insistence on Scripture alone with the guidance of the Holy Spirit produces disunity and confusion, that Reformed views on general revelation and common grace secularize knowledge and the natural world, and that belief in total depravity leads to complacency about public morality. Although there is much disagreement in the church, and sin clouds our understanding of the natural world and our actions in society, our answer to Gregory should be that this world is not our ultimate home. For all his insistence on man’s supernatural end of salvation in the world to come, Gregory wants to find authority, community, and unity in this world (presumably through the Roman Catholic Church and the reconstruction of Christendom). Gregory’s concerns about the modern world, particularly in chapters 5 and 6, are well worth further thought, and his breadth of learning is highly instructional. Although The Unintended Reformation asks worthwhile questions, Gregory’s contention that the Protestant Reformation was at the root of society’s moral decline is less than satisfying historically—moreover, it is theologically troubling.

Amy Alexander (MA in historical theology) is a graduate of Westminster Seminary California in Escondido.

THE “GOOD NEWS” ACCORDING TO ROME HOW MUST WE BE SAVED?

DECREES OF TRENT

(Chapter V) The Synod furthermore declares, that in adults, the beginning of the said Justification is to be derived from the prevenient grace of God, through Jesus Christ, that is to say, from His vocation, whereby, without any merits existing on their parts, they are called; that so they, who by sins were alienated from God, may be disposed through His quickening and assisting grace, to convert themselves to their own justification, by freely assenting to and co-operating with that said grace: in such sort that, while God touches the heart of man by the illumination of the Holy Ghost, neither is man himself utterly without doing anything while he receives that inspiration, forasmuch as he is also able to reject it; yet is he not able, by his own free will, without the grace of God, to move himself unto justice in His sight.

HEIDELBERG CATECHISM

(Q 60) How are you righteous before God? Only by true faith in Jesus Christ: that is, although my conscience accuses me, that I have grievously sinned against all the commandments of God, and have never kept any of them, and am still prone to all evil; yet God, without any merit of mine, of mere grace, grants and imputes to me the perfect satisfaction, righteousness, and holiness of Christ, as if I had never committed nor had any sins, and had myself accomplished all the obedience which Christ has fulfilled for me; if only I accept such benefit with a believing heart.

WESTMINSTER SHORTER CATECHISM

(Q 85): What doth God require of us that we may escape his wrath and curse due to us for sin? To escape the wrath and curse of God due to us for sin, God requireth of us faith in Jesus Christ, repentance unto life, with the diligent use of all the outward means whereby Christ communicateth to us the benefits of redemption.

WHAT IS FAITH?

DECREES OF TRENT

(Canon IX) If any one saith, that by faith alone the impious is justified; in such wise as to mean, that nothing else is required to co-operate in order to the obtaining the grace of Justification, and that it is not in any way necessary, that he be prepared and disposed by the movement of his own will; let him be anathema.

HEIDELBERG CATECHISM

(Q 21): What is true faith? True faith is not only a sure knowledge whereby I hold for truth all that God has revealed to us in His Word, but also a hearty trust, which the Holy Spirit works in me by the Gospel, that not only others, but to me also, forgiveness of sins, everlasting righteousness, and salvation are freely given by God, merely of grace, only for the sake of Christ’s merits.

WESTMINSTER SHORTER CATECHISM

(Q 86): What is faith in Jesus Christ? Faith in Jesus Christ is a saving grace, whereby we receive and rest upon him alone for salvation, as he is o ered to us in the gospel.

WHAT ARE JUSTIFICATION & SANCTIFICATION?

DECREES OF TRENT

(Chapter X) Having, therefore, been thus justified, and made the friends and domestics of God, advancing from virtue to virtue, they are renewed, as the Apostle says, day by day; that is, by mortifying the members of their own flesh, and by presenting them as instruments of justice unto sanctification, they, through the observance of the commandments of God and of the Church, faith co-operating with good works, increase in that justice which they have received through the grace of Christ, and are still further justified, as it is written; He that is just, let him be justified still; and again, Be not afraid to be justified even to death; and also, Do you see that by works a man is justified, and not by faith only. And this increase of justification holy Church begs, when she prays, “Give unto us, O Lord, increase of faith, hope, and charirty.”

HEIDELBERG CATECHISM

(Q 33): What is justification? Justification is an act of God’s free grace, wherein he pardoneth all our sins, and accepteth us as righteous in his sight, only for the righteousness of Christ imputed to us, and received by faith alone.

WESTMINSTER SHORTER CATECHISM

(Q 35): What is sanctification? Sanctification is the work of God’s free grace, whereby we are renewed in the whole man after the image of God, and are enabled more and more to die unto sin, and live unto righteousness.

IS THE R E FO RMATION OVER?

PLENARY INDULGENCE FOR THE YEAR OF FAITH

O CTOB ER 2012–N O VEM B ER 2013

According to a deto attain the most subSacramental Confession and pious meditation, cree made public lime level of pureness and the Eucharist and concluding with the October 5, 2012, of soul, immense benepray in accordance with recitation of the Our a n d s i g n e d b y fit may be derived from the intentions of the SuFather, the Profession Cardinal Manuel the great gift of Indulpreme Ponti¥." of Faith in any legitiMonteiro de Castro and gences which, by virtue mate form, and invoBishop Krzysztof Nykiel, of the power conferred A. “Each time they atcations to the Blessed respectively penitentiaupon her by Christ, the tend at least three serVirgin Mary and, dery major and regent of Church offers to everymons during the Holy pending on the cirthe Apostolic Penitenone who, following the Missions, or at least cumstances, to the tiary, Benedict XVI will due norms, undertakes three lessons on the Holy Apostles and pagrant faithful Plenary the special prescripts to Acts of the Council or tron saints.” Indulgence for the occaobtain them." the articles of the Catsion of the Year of Faith. "During the Year of echism of the CathoC. “Each time that, on Faith, which will last lic Church, in church the days designated "The day of the fiftifrom 11 October 2012 to or any other suitable by the local ordinary eth anniversary of the 24 November 2013, Plelocation.” for the Year of Faith, solemn opening of Vatinary Indulgence for the ... in any sacred place, can Council II," the text temporal punishment B. “Each time they visthey participate in a reads, "the Supreme of sins, imparted by the it, in the course of a solemn celebration of Pontiff Benedict XVI mercy of God and applipilgrimage, a pathe Eucharist or the has decreed the begincable also to the souls of pal basilica, a ChrisLiturgy of the Hours, ning of a Year especially deceased faithful, may t i a n c a t a c o m b , a adding thereto the dedicated to the profesbe obtained by all faithful cathedral church or Profession of Faith in sion of the true faith and who, truly penitent, take a holy site designatany legitimate form.” its correct interpretaSacramental Confession ed by the local ordition, through the readand the Eucharist and nary for the Year of D. “ On a n y d a y t h e y ing of–or better still the pray in accordance with Faith (for example, c h o s e , d u r i n g t h e pious meditation upon–the intentions of the Suminor basilicas and Year of Faith, if they the Acts of the Counpreme Ponti¥. shrines dedicated to make a pious visit to cil and the articles of the "...Plenary Indulgence the Blessed Virgin the baptistery, or othCatechism of the Cathofor the temporal punishMary, the Holy Aposer place in which they lic Church." ment of sins, imparted by tles or patron saints), received the Sacra"Since the primathe mercy of God and apand there participate ment of Baptism, and ry objective is to develplicable also to the souls in a sacred celebrat h e r e r e n e w t h e i r op sanctity of life to the of deceased faithful, may tion, or at least remain baptismal promishighest degree possible be obtained by all faithful for a congruous peries in any legitimate on this earth, and thus who, truly penitent, take od of time in prayer form."

Partner With Us.

HELP OTHERS KNOW WHAT THEY BELIEVE AND WHY THEY BELIEVE IT.

Through your monthly support as a partner of White Horse Inn you will help others rediscover the riches of the Reformation. Our partnership benefits include: a subscription to Modern Reformation, private partner podcast or CDs, books and invitations to special events.

One Subscription, 21 Years of Archives.

AS A SUBSCRIBER YOU’LL RECEIVE ACCESS TO THE ENTIRE MODERN REFORMATION DIGITAL ARCHIVE — FOR FREE.

V ISIT MODERNREFORMATION.ORG TO SUBS CR I B E TO DAY, A N D R E A D MODERN REFORMATION ON YOUR TABLET OR COMPUTER TOMORROW.