GETTING THE GOSPEL RIGHT AND GETTING THE GOSPEL OUT

Because of the support of our subscribers and the generosity of our partners, we’re excited to announce that the entire Modern Reformation archive is now accessible to everyone. For free. Enjoy unrestricted digital access to thirty years of thinking theologically. Share with everyone you know who longs to grow in knowing God and his word. And if you don’t already, please consider partnering with us to continue this crucial work.

Modern Reformation

2024 Vol. 33, No. 5

| Bible on the Bosporus: Reformation Europe and the Orthodox Church | by Zachary Purvis

| The Church’s Original Sin

“If Men Were Angels”: The Augustinian Influence on the US

Rightly Ordered Patriotism

| Sirens in Stereo: Statism from the Left and the Right | by Brian G. Mattson

illustration by Raxenne Maniquiz

No other magazine brings together confessional Lutheran, Anglican, Reformed, and Baptist representatives to discuss the significant biblical and cultural issues of our day. We’re committed to helping you hone your theological thinking and share your insights effectively with others. Your support allows Modern Reformation to keep this conversation going strong.

JESUS SUMMARIZED the law as devotion to God above all and to our neighbors as ourselves (Matt. 22:34–40). Although some neighbors are naturally closer than others, God makes it plain that we should consider every human being as worthy of our neighborly love. Whether we’re talking about the members of our family, the citizens of our country, complete strangers, even personal or cultural enemies— we need to love them as we love ourselves. Yet, as sinners prone to wander, we continually struggle with the temptation to twist or reject what God has made plain.

Sometimes we pit the two greatest commandments against one another—like loving others while neglecting God. This is especially tempting in those relationships nearest to our hearts. What if speaking biblical truth pushes away a loved one? What if Scripture doesn’t toe my favored political party line? “Whoever loves father or mother more than me,” Jesus warns us, “is not worthy of me” (Matt. 10:37). Of course, we can also fall into the opposite temptation: hypocritically seeking to love God while neglecting those bearing his image.

Sometimes we get around God’s word about neighborly love by narrowing the scope of who deserves it. Like Jonah, we resent God’s mercy and forgiveness to those we despise, refusing to rejoice when they repent (Jon. 3:5–4:4). We’re happy to receive God’s blessings but reluctant to extend them to others no less deserving. Or perhaps like the Bible scholar in Luke 10, we look for legal loopholes, asking, “Who is my neighbor?” (v. 29). Jesus responds with the parable of the good Samaritan, teaching us that neighborly love isn’t motivated primarily by natural affinity but by mercy. The good neighbor isn’t the one who looks like me; he’s the one who loves me like God does.

Finally, sometimes we deny God’s law by forcing the two greatest commandments into conflict. We exalt the human alongside the divine original. Here our devotion to others crowds out (even overthrows) our devotion to God. Jesus refuses to allow us this path either: “No one can serve two masters” (Matt. 6:24). Although he’s speaking about money, his words are just as true when applied to family, country, or any other created reality. Nothing must distract from, or compete with, our devotion to King Jesus. Worshiping anything instead of God is idolatry. So is worshiping anything alongside him.

As Christians, our devotion to earthly goods is subservient to our devotion to Christ as Lord. This fundamentally transforms the character of our love—which has always made the church’s allegiances paradoxical. How can we relativize Caesar’s authority while praying for him and submitting to him (Rom. 13:1–9)? How can we be good citizens of our earthly countries while belonging to a heavenly one (1 Pet. 2:13–17)?

We can hold together the two greatest commandments because Jesus didn’t merely summarize them for us: He fulfilled them for us in his life, death, and resurrection. And he fulfills them in us now by giving us his word and enabling us by his Spirit to walk in his righteousness (1 John 2:1–6). Indeed, “We love because he first loved us” (4:19). In Jesus, love of God and neighbor hold together as mysteriously and perfectly as divinity and humanity.

Brannon Ellis Executive Editor

Learning from the wisdom of the past

by Zachary Purvis

IN 1629 AND 1630, MAXIMUS OF GALLIPOLI sat in a room in the Dutch embassy in Constantinople (today, Istanbul). A learned monk ordained as a priest in the Greek Orthodox Church, he spent his days in the ambassador’s residence overlooking the Golden Horn on the Bosporus Strait, laboring on the first ever translation of the New Testament into the Greek vernacular. Maximus’s text, published only in 1638, is little known outside a handful of academic specialists. This is unfortunate because his achievement in rendering ancient, first-century Greek into modern, intentionally simple, seventeenth-century Greek was remarkable. The circumstances surrounding the text are, moreover, the stuff of an Orhan Pamuk novel, filled with international intrigue: Created in the heart of the Ottoman Empire, aided by Reformed Swiss-Italians, corrected by the Patriarch of the Orthodox Church of Constantinople, coordinated by the Dutch ambassador, paid for by the Dutch Republic, and printed in Geneva under the oversight of the Venerable Company of Pastors, Maximus’s edition demonstrates how the European reformations touched but did not take hold of the Greek Orthodox world.

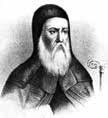

Maximus’s translation belongs, properly, to the turbulent age of Cyril Lucaris, whose tenure as patriarch of Constantinople ran from 1620, with several interruptions, until 1638. 1 Born in Crete (then under Venetian rule), Lucaris spent time in Padua and Venice studying under Greek humanists with ecumenical sympathies. Some historians allege that he visited the Low Countries and even Geneva, where he was introduced directly to Reformed theology, but there is no evidence to place him in either location. Upon ordination, Lucaris went to Brest in Poland-Lithuania as a special envoy of the then patriarch of Alexandria, his uncle, to help the Orthodox curb Roman Catholic intrusions into Poland, an operation that mostly failed. In 1601, Lucaris found himself installed as patriarch of Alexandria in Cairo, Egypt, where he remained until 1620 when he became patriarch of Constantinople, again battling Roman Catholic interference among Orthodox Christians.

Lucaris loved to exchange ideas with European Protestants. Exactly what sparked his interest is unknown, but in 1602 he met the Dutchman Cornelius Haga, then traveling in Istanbul. When in 1612, Sultan Ahmed permitted the Dutch to trade in the Ottoman Empire, Haga became the Dutch Republic’s first diplomatic representative to the Sublime Porte. Through Haga, Lucaris began

to correspond with various Dutch Protestant ministers. He bought and annotated books by both Protestant and Roman Catholic authors: Jacobus Arminius, Robert Bellarmine, and others. He discussed Christianity with the archbishop of Canterbury and with Marco Antonio de Dominis, the erstwhile archbishop of Spalato (today, Split, Croatia), who fled to England after a disagreement with Rome. He gifted the priceless Codex Alexandrinus, one of the earliest and most complete manuscripts of the Bible, to King James I of England for James’s support in Lucaris’s struggle to retain the patriarchate against his enemies, who had been aligning themselves with Jesuits to steer the Orthodox toward Tridentine Catholicism. As the gift to England shows, he reached out to Protestants abroad while engaged in battle with Roman Catholics at home.2

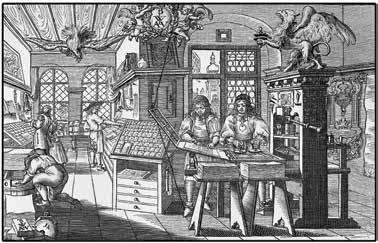

Repeated confrontations with the Jesuits characterize Lucaris’s time in Constantinople. One scholar estimates that different Roman Catholic and Protestant groups paid a combined 54 million akçe—nearly what it cost to build Istanbul’s grand Süleymaniye Mosque in the 1550s—in bribes to Ottoman authorities to have Lucaris either deposed or reinstated.3 Jesuits set up free schools for Greek Orthodox children that focused on the Latin rite. The Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith in Rome set its polyglot press buzzing, churning out Greek books celebrating Roman Catholicism and delivering them to Jesuit missionaries around the eastern Mediterranean.4 In response, Lucaris established the first, albeit short-lived, Greek printing press in the East.5 The texts that issued from it included a vernacular Greek statement of the Orthodox faith and Latin and Greek versions of Lucaris’s own Confession of Faith, a document clearly affirming the supreme authority of Scripture for faith and life, justification by faith alone, and predestination. Financed by the Dutch Republic and printed in Geneva—all arranged by Cornelius Haga—the Confession has since earned Lucaris the sobriquet, in some circles, of the “Protestant Patriarch.” 6 While Lucaris’s full desire to see the Reformed tradition embraced among the Orthodox is debatable, he did encourage the Dutch to send two hundred copies of the Belgic Confession and Heidelberg Catechism, which had been translated into Greek and printed under the title Ecclesiarum Belgicarum confessio, now bound with select canons from the Synod of Dort, making special efforts to distribute them in Constantinople. 7 Lucaris’s groundbreaking project—again with the Dutch—was the modern Greek Bible. One of the main figures responsible for it was Antoine Léger, a minister from Piedmont and close friend of Benedict Turretin, himself a pastor-professor in Geneva and father of the more well-known theologian Francis Turretin. Sent from Geneva’s Company of Pastors, Léger served as chaplain to Cornelius Haga, the Dutch ambassador in Constantinople. Léger assisted Maximus the translator, while Lucaris helped proofread and revise the text. The source text they used was an Italian translation made in 1607 by Giovanni Diodati, the Swiss-Italian theologian and linguist. The Dutch ambassador wanted the text printed in two columns with ancient Greek on the left and vernacular on the right “in order to deprive the Papists of any means” to critique the translation.8 “You have done well,” Lucaris told Léger, “to collate the original texts with the

In 1601, Lucaris found himself installed as patriarch of Alexandria in Cairo, Egypt, where he remained until 1620 when he became patriarch of Constantinople.

Seventeenthcentury book printing workshop

vernacular. I see that Father Maximus has been very diligent in his translation. The text of Mr Diodati has been followed. Doubt about certain words matter little, while all [words] correspond to their meaning.” Lucaris did challenge Maximus’s choice for the right Greek word for “bread,” suggesting the more common psomi , rather than artos and explaining his rationale in great detail.9 The States General, de facto federal government of the Dutch Republic, agreed to cover the costs for printing the translation. They asked Jacob Golius, professor of Arabic at the Calvinist University of Leiden, to determine whether the translation would incite any riots among Greeks—apparently, Golius said no. Cornelius Haga insisted on the production of no fewer than 1,500 copies. More than 150 were to be kept by Haga and the University of Leiden; the rest of the books were to be shipped secretly to Constantinople for distribution. Maximus was also to go to Geneva to oversee the proofreading and typesetting. The project’s final phases, however, turned out to be far more complicated than expected. Both Maximus’s travel expenses and the paper for the books ran far over budget and required new sources of funding. The printer’s copy of the text was initially lost and when found was basically illegible because of the shorthand and abbreviations used. Léger’s successor died before he could complete revisions, and Maximus died before the transcription and typesetting were completed. David Le Clerc, Geneva’s professor of oriental languages, was hired to proofread, but he too died before the work was finished.

By the time the translation reached print, Lucaris had also died. Following an accusation by Jesuits in Constantinople, who alleged that Lucaris planned a rebellion against the Ottomans, Lucaris was arrested and convicted of high treason. He was strangled by Janissaries, the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan’s army, and his body was thrown from a ship into the Bosporus. Without the original team—Maximus, Lucaris, Cornelius Haga, Léger— the translation’s distribution was a total fiasco. Some copies went to Leiden as agreed. Four hundred copies went to Haga’s house back in the Netherlands. The remainder were to be carted from Geneva to Marseille and then shipped to Constantinople, but most of these never left Geneva. Instead, they were confiscated by the printing house because the rent for the room in which the books had been stored had gone unpaid. Nearly thirty years later, Genevan theologian Francis Turretin informed Dutch Levantine Trade directors that 1,130 copies of these New Testaments were still in storage in Geneva. Still later, Turretin’s son, Jean-Alphonse, reminded the States General that he had the books in his Nearly thirty years later, Genevan theologian Francis Turretin informed Dutch Levantine Trade directors that 1,130 copies of these New Testaments were still in storage in Geneva.

possession, ready for shipment. Not until the 1730s—some hundred years after the project began—did the books finally travel east.10

In the end, what makes Lucaris most luminous is his consistent championing of the Bible in terms evocative of Protestants—from Luther and eventually, though after Lucaris’s time, to the Westminster Divines. In the appendix to his Confession, Lucaris said that the Holy Spirit worked through the word to dispel darkness. No one, therefore, should prevent any person from reading the Bible and finding in it the doctrines of the Christian faith. In the preface he wrote to the 1638 New Testament, he stressed that readers should be able to access the text directly and not only as mediated by elite clerics, as in traditional Orthodox practice. All Christians, and all of his people, Lucaris insisted, should be able to read Scripture in their own language.11 The goal was as admirable as it was dangerous, for it pitted him against many of his Orthodox peers and certainly shortened his life—just as many Reformers met persecution when they embraced sola scriptura. Cyril Kontaris, Lucaris’s successor as patriarch of Constantinople, had been educated at the Jesuit College in Istanbul and harbored sympathies for Rome. He swiftly convoked a synod to have Lucaris and his publications anathematized. Finally, in 1672, the Orthodox Synod of Jerusalem condemned the New Testament in vernacular Greek. In this sense, at least, the European reformations did not pass the Greek Orthodox world by.12

Zachary Purvis (DPhil, University of Oxford) teaches church history and theology at Edinburgh Theological Seminary.

1. Ovidiu Olar, “‘Un Trésor enfoui’: Kyrillos Loukaris et le Nouveau Testament en grec publié à Genève en 1638 à travers les lettres d’Antoine Léger,” Cahiers du Monde russe 58, no. 3 (2017): 341–70.

2. Ovidiu Olar, “La boutique de Théophile: les relations du patriarche de Constantinople Kyrillos Loukaris (1570–1638) avec la réforme” (Paris: EHESS; Centre d’études byzantines, néo-helléniques et sud-est européennes, 2019).

3. Dénes Harai, “Une Chaire aux enchères: ambassadeurs catholiques et protestants à la conquête du patriarcat grec de Constantinople, 1620–1638’, Revue d’histoire moderne et contemporaine 58, no. 2 (2011): 49–71.

4. Zacharias N. Tsirpanlis, “Libri greci pubblicati dalla ‘Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide’ (XVII sec.),” Balkan Studies 15 (1974): 204–24.

5. Evro Layton, “Nikodemos Metaxas, the First Greek Printer in the Eastern World,” Harvard Library Bulletin 15, no. 2 (1967): 140–68.

6. See, e.g., Steven Runciman, The Great Church in Captivity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1968), 259–88; and George A. Hadjiantoniou, Protestant Patriarch: The Life

of Cyril Lucaris (1572–1683) (Richmond, VA: John Knox Press, 1961).

7. Vasileios Tsakiris, “The ‘Ecclesiarum Belgicarum Confessio’ and the Attempted ‘Calvinisation’ of the Orthodox Church under Patriarch Cyril Loukaris,” Journal of Ecclesiastical History 63, no. 3 (2012): 475–87.

8. Christiaan Sepp, “Het Nieuw-Grieksche Testament van 1638,” Bibliografische mededeelingen (Leiden: E. J. Bril, 1883), 203.

9. Émile Legrand, Bibliographie hellénique, vol. 4 (Paris: Leroux, 1896), 476, in Richard Calis, “The Impossible Reformation: Protestant Europe and the Greek Orthodox Church,” Past & Present 259 (May 2023): 43–76, at 65.

10. Sepp, “Het Nieuw-Grieksche Testament van 1638,” 187–256.

11.

(Geneva, 1638),

12. Anthony J. Khokar, “The ‘Calvinist Patriarch’ Cyril Lucaris and His Bible Translations,” Scriptura 114 (2015): 1–15.

Lucaris said that the Holy Spirit worked through the word to dispel darkness. No one, therefore, should prevent any person from reading the Bible and finding in it the doctrines of the Christian faith.

by SIMONETTA CARR

THE RELATIONSHIP between church and state has generated questions from the start. Although the basic biblical principles seem straightforward, their applications to specific situations have frequently been muddled and perplexing. At the root of this confusion might be what Leonardo de Chirico, historian and chair of the Theological Commission of the Italian Evangelical Alliance, calls the church’s “original sin; that is, its desire to be both church and state.” 1

Roman Emperor Constantine has often been blamed for first muddling these waters. Before him, the apologists left us the picture of a persecuted church striving to respond to mistreatments with forgiveness and patience, setting an example of communal love and respect for authorities in everything that is not sinful.

A primary, much-quoted example of early Christians’ relationship to the state is the Letter to Diognetus, portraying Christians as people who “dwell in the world, yet are not of the world”—people who are “distinguished from other men neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe. . . . But, inhabiting Greek as well as barbarian cities . . . following the customs of the natives in respect to clothing, food, and the rest of their ordinary conduct, they display to us their wonderful and confessedly striking method of life” 2 (which the letter goes on to describe). Although the reality may not always have been as idyllic as Diognetus’s description, he conveyed the general ideal and mindset.

Enter Constantine with the 313 Edict of Milan, making Christianity an accepted religion in the Roman Empire. (Even Galerius, one of the fiercest enemies of Christianity, eventually came to realize that persecuting Christians was a counter productive battle.) But the fact that Constantine endorsed Christianity caused a proliferation of nominal Christians seeking imperial favor—and, consequently, a rise of ascetics looking for a more committed expression of Christian life.

Yet, as pivotal as Constantine’s edict was, much stayed the same. Each emperor still felt bound to his traditional duties of pontifex maximus, supervising the religious life of his people (as is clear in Constantine’s convocation and supervision of the Council of Nicaea in 325). Besides, the Edict of Milan and the Council of Nicaea did not put an end to religious disputes and persecution. Constantine’s sons embraced Arian views and harassed, threatened, and exiled bishops who refused to submit to their religious dictates.

In 380, Emperor Theodosius made Nicene Christianity the state religion, although Arianism persisted throughout the empire. The church then continued to become more prosperous and institutionalized, mimicking the structure of the empire and taking over many civil responsibilities, especially after the Western empire fell and lacked civil leaders.

The long history of conflicts between church and state during the Middle Ages is well documented. The church’s desire to be both church and state escalated to the point that several popes, such as Gelasius II and Boniface VIII, could unashamedly claim spiritual power (with political ramifications) over the whole world. This was not a simple hunger for power. Most popes were sincerely convinced they had been placed on the papal throne by God to fight his righteous battles. And yet despite this conviction, the medieval church had to recognize the authority of secular rulers, which took different forms: from the missionary tactic of winning the approval of kings who could impose Christianity on their subjects to the foundation of a Holy Roman Empire where the pope could influence secular decisions. Even the Protestant Reformers had to accept the fact that a country’s rulers had to be on board if the church was to be reformed within its borders.

For missionaries, this inevitable alliance generated several nominally Christian states. It was, from their point of view, a victory—a foot in the door that allowed them to freely evangelize the nations. In reality, since their evangelization programs were still limited, most of the rural population lived with a mixture of paganism and Christianity—the latter scarcely taught by unprepared preachers. A blatant example of the dangers of a close alliance between church and state is the twelfth-century story of Thomas Becket. He died by order of the same king who had ordained him archbishop of Canterbury, despite the expectation that the king would follow his lead.

For sixteenth-century Reformers, reform efforts were hardly under foot before it became clear that allying with rulers entailed some dangerous compro -

mises. Many of the Reformers became entangled in uncomfortable politics as a result. Even those who acclaimed Elizabeth’s rise to the throne after years of Marian persecution were stumped by her 1558 act of suspension of preaching.

While the church in Britain continued to wrestle with questions of the interaction between church and state, the authors of the 1561 Belgic Confession apparently had no qualms in identifying the state as responsible “not only to have regard unto and watch for the welfare of the [civil] polity, but also to maintain the true sacred ministry; and thus may remove and prevent all idolatry and false worship; that the kingdom of anti-Christ may be thus destroyed and the kingdom of Christ promoted” (Article 36). This article was revised in 1905 by the synod of the Gereformeerde Kerken Nederlands and later denounced as unbiblical by other synods.

The church’s desire to form an alliance with the state has dangerous ramifications. For example, an alliance with rulers who seem to endorse a Christian agenda can blind the church to dangerous compromises required by the state or to a government’s tendency to use the cross as a symbol of political power. Some extreme examples of this loss of sight are the national church of Germany during Hitler’s rule and the national church of South Africa during apartheid. The alliance between the church in Rwanda with the genocidal government of the 1990s was equally horrific. When church buildings became primary killing grounds, Christians, including pastors, joined in the killing. As Timothy Longman, director of the African Studies Center at Boston University, writes, “Christians could kill without obvious qualms of conscience, even in the church, because Christianity, as they had always known it, had been a religion defined by struggles for power, and ethnicity had always been at the base of those struggles.” 3

It is easy to say that our churches will never fall so low. It is therefore more difficult, but extremely important, to stop and reflect on how so many Christians all over the world have been able to still their consciences and twist the Scriptures to ally with political powers that offer a kernel of truth to justify their atrocities. Most of them were sincere Christians.

How could the churches in these countries justify, and even join, such horrific violence? According to Longman, unlike other groups and organizations of that time, the churches in Rwanda had been allowed to retain autonomy from the state. Still, “church leaders in Rwanda sought to maintain a close and cooperative relationship with political leaders, believing that an alliance with the state created the optimum setting for a church to flourish.” 4 It is sobering to realize how easily seemingly innocuous pragmatism can degenerate into all-too-comfortable blinders.

Conversely, a church can compromise with the government out of fear. If there is a perception that an alliance with the state can help a church to flourish,

For sixteenthcentury Reformers, reform efforts were hardly under foot before it became clear that allying with rulers entailed some dangerous compromises.

If there is a perception that an alliance with the state can help a church to flourish, there is an equally pervasive fear that if a church does not ally with a government that promises protection . . . the church will be destroyed.

there is an equally pervasive fear that if a church does not ally with a government that promises protection (or at least the preservation of a comfortable status quo), the church will be destroyed. In this scenario, Christians have often compromised their principles—even their basic theology. Looking back at the crimes of apartheid, Anglican bishop Frank Retief confessed,

Like most other whites, our white-led church believed we were in a struggle for Western values and freedoms and that the liberation groups were all pawns of the communist regimes. Be that as it may, the fact of the matter is that we allowed ourselves to be misled into accepting a social, economic, and political system that was cruel and oppressive.5

Likewise, fear induced many Christians in China to ally with a government that requires unquestioning loyalty not only to itself but to the theology it sponsors—a theology that rewrites Christianity to prioritize political unity. According to Wang Yi, a Chinese pastor imprisoned for his beliefs,

After the government issued three threats, other church leaders felt that a storm was coming. They lost hope in the word in which they believed and in the sovereignty of God in history. They came to believe that if they did not compromise, the church would be thoroughly ruined. Because of their small faith, thinking that they were suffering for Christ, they accepted codependence on politics.6

It is, however, encouraging to remember that even in these dire situations, many Christians have resisted, often at personal loss, these common temptations of compromising with the state, putting their trust in a political power, or setting themselves as a rival power. If the desire to be church and state is the original sin, these Christians have manifested the proper attitude of a redeemed church, keeping to the mission Jesus gave them when he said,

“All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.” (Matt. 28:18–20)

As Wang Yi observed,

An organization cannot be called a church if it does not make the Great Commission its primary objective. . . . If a church sacrifices its root to express love to the motherland, this love is worthless because the existence of the church is worthless, like salt that has lost its taste. . . . Only when churches stand firm in the founda-

tion of the universal church through dependence on Christ will they be able to express their respect for secular power and their love for their neighbors. This is the proper starting point for patriotism.7

In its inevitable interactions with the state, which might include resistance when necessary, Wang believes it is important for the church to check its motives: “How do we show that we are motivated by faith, not by political goals? We must be willing to take the way of the cross and suffer for our faith.” 8

In this, he echoes the writings of the early church and the firm consciousness of Christian identity that prompted martyrs like Perpetua to say, “I cannot call myself by any other name than what I am, a Christian.” It is this consciousness of who we are in Christ that will prevent us from falling back into the church’s “original sin” in all its modern, often subtle expressions. And it is this consciousness that will remind us that, as we keep to our task, Christ will keep his promise of building his church against the gates of hell (Matt. 16:18), since he has already “overcome the world” (John 16:33).

Simonetta Carr is the author of numerous books, including Broken Pieces and the God Who Mends Them: Schizophrenia through a Mother’s Eyes, and the series Christian Biographies for Young Readers (Reformation Heritage Books).

It is this consciousness of who we are in Christ that will prevent us from falling back into the church’s “original sin” in all its modern, often subtle expressions.

1. Leonardo de Chirico, Letture Patristiche (IV–V secolo), Year XXXI 2019/1N. 61, IFED.

2. “The Epistle of Mathetes to Diognetus,” Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 1, chapters 6, 5, ed. Alexander Roberts, James Donaldson, and A. Cleveland Coxe, trans. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature, 1885). Rev. and ed. Kevin Knight, New Advent, http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/0101.htm.

3. Timothy Longman, Christianity and Genocide in Rwanda (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 164.

4. Longman, Christianity and Genocide in Rwanda, 26.

5. Frank Retief, answering a panel chaired by TRC head Archbishop Desmond Tutu, South African Press Association, November 1997, https://www.justice.gov.za/ trc/media/1997/9711/s971117h.htm.

6. Wang Yi et al., Faithful Disobedience: Writings on Church and State from a Chinese House Church Movement, ed. Hannah Nation and J. D. Tseng (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2022), 70.

7. Yi et al., Faithful Disobedience, 60.

8. Yi et al., Faithful Disobedience, 195.

Exploring perspectives from the present

“IF MEN WERE ANGELS”:

by MICHAEL HORTON

This essay is a lightly edited version of a speech Dr. Horton gave at the Nixon Library in 2018. Part political history and part historical theology, he traces the influence of Catholic and reformational convictions about the fallenness of human nature on the development of early modern political thinkers (especially James Madison) and forms of government (especially the US republic). Horton offers a fascinating and nuanced example of the truth that, in all areas of life, theology really does matter.

Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan (1651) and Benedict Spinoza’s Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (1670) were animated by different contexts and concerns. Shaken by civil war and the destabilizing religious sectarianism of the English interregnum, Hobbes’s great fear was political pluralism. His answer was an exclusive right of the sovereign over the public sphere. Since this included religion, the church must be an institutional expression of the sovereign’s will.

Excommunicated from the Amsterdam synagogue for infidelity, Spinoza belonged to a liberal pietist community that shared his disdain for the dominance of the Reformed church in particular and the authority of “the priesthood” embodied in creeds, confessions, liturgies, sacraments, and discipline. While Spinoza praised the Dutch Republic as the freest nation in Europe, the indefatigable clergy-led opposition to his pantheistic and fatalistic system represented the greatest threat to what he called “freedom to philosophize.”

Motivated in part by their own heterodox theological views, both Hobbes and Spinoza sought to subordinate the church to the state in the form of a civil religion. This could be realized in an absolute monarchy akin to Restoration Britain or in a democracy modeled on the Roman republic, but the outcome in either case was freedom from religion—at least religion as a sphere independent of the state. Apart from such assimilation, Hobbes and Spinoza insisted, the power of the priests would continue to exert inordinate influence over the public life of citizens.

Both thinkers argued that genuine religion (that is, one based entirely on buttressing the dictates of morality known by nature) should be not only tolerated but encouraged by the state. Their distinctive dogmas and rituals, however, do not belong to the realm of public reason and are of no use as an incentive to public virtue. It is when religious institutions range beyond their mandate of reinforcing civil morality (or, in Hobbes’s case, whatever the sovereign decrees) that they must be reined in by the state. If we hear echoes of Hobbes and Spinoza in the contemporary theories of John Rawls and Richard Rorty, then we should discern the stronger echoes of Martin Luther and John Calvin—and behind them, Augustine—in James Madison.

Unchecked, human ambition always leads to despotism, regardless of its particular form: absolute monarchy, oligarchy, or mob rule.

Like other American founders, Madison was indebted to John Locke and especially to the French historian and jurist Montesquieu. A key principle of Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws (1748) is that “government should be set up so that no man need be afraid of another.” 1 However, his close analysis of history, especially Rome’s transition from republic to empire, demonstrated that this state of mutual trust could not be taken for granted. It could never depend on the benevolence of the sovereign or of any administration but had to be secured by laws that clearly separated the powers. Unchecked, human ambition always leads to despotism, regardless of its particular form: absolute monarchy, oligarchy, or mob rule. If Augustinian-Reformation theology played a crucial role in forming Madison’s view of human nature, then Montesquieu offered practical advice on how to formulate the separation of powers constitutionally. It was Scottish clergyman John Knox Witherspoon’s lectures on moral philosophy, however, that seem to have had the most impact on Madison’s thinking.

Founded in 1746 to train Presbyterian ministers, the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) invited Witherspoon in 1768 to become the school’s president. A staunch evangelical in the Church of Scotland, Witherspoon was also indebted to Scottish common sense philosophy. As an ardent defender of the distinction between spiritual and temporal authority, Witherspoon believed that while only the gospel is a saving remedy, natural law and philosophy could encourage civic virtue. Under Witherspoon’s leadership, the college fulfilled its original mission of educating “ornaments of the State as well as the Church.” His students included a US president and vice president, nine cabinet officers, twenty-one senators, thirty-nine congressmen, three Supreme Court justices, and twelve governors. The lion’s share of the members on the drafting committee at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, including James Madison, were Witherspoon’s students.

Though a Virginian, Madison chose Princeton over William and Mary. Even after he finished his degree, he stayed on to study Hebrew and theology with Witherspoon independently and frequently expressed his debt in later years to Witherspoon’s instruction and personal relationship. “Man is everywhere considered as in a fallen and sinful state,” said Witherspoon. “Everything that is prescribed to him, and everything that is done for him, goes upon that supposition.” 2 And yet, because of God’s providence and the fact that human beings are created in God’s image, there remains a civil virtue sufficient to curb the passions of self-love.

Many of America’s founders were attracted to the French Revolution and its egalitarian ideals. However, the great anthropological premise of the US Constitution is not the goodness and perfectibility of human nature but the very opposite. At least outside of Britain, many Enlightenment thinkers were devotees of the French Revolution, with its utopian expectation of the imminent perfection of human nature and history. This included Immanuel Kant, John Paine, Thomas

Jefferson, and John Adams. Many of America’s founders were also attracted to the Unitarian and Deistic trends in Britain and especially France. In fact, led by Ralph Waldo Emerson, Unitarians in New England had already held an unceremonious funeral for Calvinism with its doctrine of original sin. While the Enlightenment had a large place in the thinking of America’s founders, it is difficult to imagine that a form of government built on such an assumption could have evolved from such sympathies. So what accounts for this lack of optimism?

The most important and abiding influence of Witherspoon on Madison— and therefore our constitution—is a very un-Enlightenment view of human nature. In Federalist Paper #51 (published from 1787 to 1788), Madison argues,

The great security against a gradual concentration of the several powers in the same department, consists in giving to those who administer each department, the necessary constitutional means, and personal motives, to resist encroachments of the others. . . . Ambition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man, must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place.

It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.3

Progressives love to quote the first half of Madison’s argument: “If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” while conservatives highlight the second half: “If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary.” Madison, however, affirms both equally, grounding them in a sober view of human nature: Neither individuals nor governments are angelic. Calvin made the same point in a sermon based on Galatians 3:19–20, “The Many Functions of God’s Law” (1558). “If we were like angels, blameless and freely able to exercise perfect self-control, we would not need rules or regulations.” 4

Unlike Aristotle and many today, Madison did not believe any more than Luther or Calvin that good laws make good people. On the contrary, because of humanity’s inveterate self-love, the state is authorized to restrain its civil effects

and the state itself needs to be restrained. In Federalist #10, Madison states, “Since the causes of factions cannot be removed, . . . relief is only to be sought in the means of controlling its effects.” In #51, he writes:

This policy of supplying, by opposite and rival interests, the defect of better motives, might be traced through the whole system of human affairs, private as well as public. We see it particularly displayed in all the subordinate distributions of power, where the constant aim is to divide and arrange the several offices in such a manner as that each may be a check on the other—that the private interest of every individual may be a sentinel over the public rights. These inventions of prudence cannot be less requisite in the distribution of the supreme powers of the State.

Not to be left to the realm of general theory, the rest of Federalist #51 offers detailed prescriptions for the practical checks and balances on government. We do not have a great constitution because Madison thought the American people were great, but because he was convinced they share in the common corruption of the human race.

In a number of important respects, the Reformation constituted another source of early American thought in ways that more closely parallel England’s experiment with republicanism. None of the Protestant Reformers could have foreseen the dawn of political and economic liberalism; in fact, their opposition to the radical Anabaptists reinforced their generally conservative approach to revolutionary systems. Driven by a concern to recover the gospel from its “Babylonian captivity,” Luther found himself and his cause opposed on every hand by an absolute papal monarchy. Calvin, the second-generation Reformer, sought greater independence for the church from its domination by Geneva’s magistrates. Like Luther, Calvin was shaped by Augustine’s distinction between the “two cities”: the City of God, which is spiritual and eternal, and the City of Man, which upholds (with varying degrees of modest success) important but penultimate justice, freedom, and security in temporal affairs. These two kingdoms “must not be mingled,” Calvin insists. In fact, he says, the laws that governed the theocracy of Israel under Moses are no longer in force. So long as the general principles of natural law engraved in human nature are upheld, a modern constitution is valid. Like Luther, Calvin emphasized the dignity of all human beings as God’s image-bearers and the dignity of worldly callings, including civic participation and service. Both Reformers were convinced that humanity is fallen. Though still capable of civic righteousness (i.e., virtuous acts in the public sphere), the children of Adam are not capable of attaining justification before God or renewal of their fallen nature by their own efforts. Furthermore, since justification comes

through faith alone, and faith is a gift of God through the gospel, both Reformers insisted it could not be coerced. They assumed there would still be cooperation between church and state. There is no anticipation here of the First Amendment to the US Constitution. And yet many of the elements are present that would make such a move plausible theologically to conservative Protestants as well as Unitarians and Deists.

Calvin was also trained in classical jurisprudence. His first work was a commentary on Seneca’s On Clemency (c. AD 55), widely used in law faculties in France. This background made the Genevan Reformer a keen student of political systems; nevertheless, given his theological commitments, he exercised restraint in pronouncing on their relative merits. His brief remarks in the Institutes of the Christian Religion (1559) insist that the gospel is not dependent on any political system and that the church has found itself in a variety of societies with diverse constitutions. If allowed, he adds tentatively, he would prefer a combination of aristocracy and democracy. “It is an invaluable gift if God allows a people to elect its own government and magistrates.” 5 In addition, there should be several political institutions or branches, with checks on any one gaining inordinate power over the other. As Lee Ward explains,

Calvin’s republican sympathies derived from his view of human nature as deeply flawed. Compound or mixed governments reflect the reality that human frailty justifies and necessitates institutional checks and balances to the magistrate’s presumed propensity to abuse power. It was this commitment to checks and balances that became the basis of Calvin’s resistance theory, according to which inferior magistrates have a duty to resist or restrain a tyrannical sovereign.6

Madison’s influences can hardly be reduced to Christian, much less Reformation-oriented, sources. Nevertheless, the US Constitution is similar to the Constitution of the United Provinces (Netherlands), a fact Madison himself observed in Federalist #20. In contrast, there are few if any influences from Hobbes, Spinoza, or Rousseau. In a 2009 Harper’s article, historian Scott Horton observes, “A number of historians, pointing to the overlap between pockets of Calvinism and

We do not have a great constitution because Madison thought the American people were great, but because he was convinced they share in the common corruption of the human race.

It was this commitment to checks and balances that became the basis of [John] Calvin’s resistance theory, according to which inferior magistrates have a duty to resist or restrain a tyrannical sovereign.

democracy, convincingly argue that Calvinist thought propelled Enlightenment values including respect for the dignity of humankind and democracy.” 7 While Thomas Jefferson might justify the separation of church and state with more Spinoza-sounding arguments (freedom from the “Athanasian and Calvinistick [sic] divines”), Madison’s reasoning favors freedom of religion more than freedom from it. For example, he challenged Patrick Henry’s call for a tax to support Christian teachers—not on secularist grounds but because the state is incompetent and unauthorized to intrude upon the more important matters of eternal salvation. Who will grant to the state the privilege of determining which is a true church and which is the true doctrine and worship? A citizen pays taxes to support common welfare and defense but participates in the church “with a saving allegiance to his Universal Sovereign.” Therefore, “Religion is wholly exempt” from the authority of “Civil Society.” 8 Such a tax for instruction in Christian doctrine would make teachers of doctrine employees of a lesser kingdom, Madison adds, referring directly to the Reformation doctrine of the “two kingdoms.” Madison’s personal faith is ambiguous. Although a member of the Presbyterian Church, he seems gradually to have moved in a more nominal direction. Yet he remained a product of his education, much of which he apparently still found intellectually persuasive.

Michael Horton is editor-in-chief of Modern Reformation and the J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics at Westminster Seminary California in Escondido.

1. Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, bk. 11, ch. 6, “Of the Constitution of England,” https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/ founders/documents/v1ch17s9.html.

2. Ian Speir, “The Calvinist Roots of American Social Order: Calvin, Witherspoon, and Madison,” Public Discourse, April 13, 2017, http://www.thepublicdiscourse.com/2017/04/19116/.

3. All quotes can be found in the “Federalist Papers: Primary Documents in American History,” Library of Congress Research Guides, https://guides.loc.gov/federalist-papers/full-text.

4. John Calvin, Sermon on Galatians 3:19–20, “The Many Functions of God’s Law” (1558), Sermons on Galatians (Edinburgh 1997).

5. Quoted in Jan Weerda, “Calvin,” Evangelisches Soziallexikon, 3rd ed. (Stuttgart, 1960), col. 210.

6. Lee Ward, Modern Democracy and the Theological-Political Problem in Spinoza, Rousseau, and Jefferson. Recovering Political Philosophy (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), 25–26.

7. Scott Horton, “Calvin and Madison on Men, Angels and Government,” Harper’s Magazine, November 14, 2009.

8. Memorials and Remonstrance against Religious Assessments, XX.

by Sarah Reardon

“The voice of my beloved! Behold, he comes, leaping over the mountains, bounding over the hills.” –Song of Solomon 2:8

Besides the conversation of the cricket And distant whirs of passing cars, no voice Invades this night. The grazers in the thicket, If not asleep, stay watching, stand with poise. Unlike the doe, with soft eyes wide, content, I watch with care as constant as a stoplight: I flicker. Eyes soon droop, and spirit spent, My ears benumbed to creatures out of sight. But spoken words will shake me soon awake, I know. I have been told. I will behold The far-off voice, beloved, bound to break This day with song and scatter all the cold Of every quiet dusk. And when he comes I will arise, my night of waiting gone.

Thinking theologically about all things

by JOHN D. WILSEY

And there’s another country, I’ve heard of long ago Most dear to them that love her, most great to them that know. We may not count her armies, we may not see her King Her fortress is a faithful heart, her pride is suffering And soul by soul, and silently, her shining bounds increase And her ways are ways of gentleness, and all her paths are peace.

Sir Cecil Spring-Rice

Iwas blessed with a grandfather who modeled a life that represented an impeccably well-ordered hierarchy of loves. Jasper N. Dorsey (1913–1990), whom we all called “Papa,” was a devoted husband, father, grandfather, friend, churchman, patriot, and public servant. He was the most honorable man I have ever known. What made him so was the way he prioritized the things he loved in word, deed, and precept. The effects of his well-ordered life were seen in his irrepressible optimism, his joie de vivre, and his sense of humor all mixed with an uncompromising demand for excellence that he made of himself and those in his charge. He serves as an example of a real person with a nature like ours who demonstrated how to rightly balance the love of two countries: one in the already and the other in the not-yet. Papa knew that the secret to balancing love of God with love of country was no secret, but that it was bound up in the two most simple and significant divine commandments the Lord Jesus taught us in Mark 12:29–31. He faithfully aspired to love the Lord with all his heart, soul, and might and doing that, to love his neighbor as he loved himself. In his fruitful life, Papa enjoyed a profoundly happy fifty-one-year marriage to my grandmother, raised two children, served his country in the army during World War II, and rose in the ranks of Southern Bell Telephone and Telegraph Company, from climbing telephone poles as a lineman to serving as CEO of all operations in Georgia between 1936 and 1978. Almost from the moment of his graduation from the University of Georgia in 1936, he was dedicated to the advancement of education for young Georgians as citizens and their development as leaders in business, politics, churches, schools, and media. He was an elder in the Presbyterian church, and he wrote a weekly syndicated column that appeared in over forty newspapers in Georgia.

Along with his successes, Papa suffered more than his share of tribulations. He and my grandmother lost two children—one son who was stillborn, and another who was killed in a tragic car accident while he was driving home from college at the young age of twenty-one. My uncle Tucker died before I was born, but my mother always said that her parents were never the same after suffering the loss of their youngest child. Toward the end of his life, Papa faithfully cared for my grandmother during a ten-year debilitating illness that ended in her death. After she died, my grandfather courageously faced the excruciating pain of bone cancer, which finally took his life in August 1990. Still, my experience with both grandparents was of two people who understood, more than most, the great truth that God is the giver of every good and perfect gift, and that the greatest gifts God gives always come in the context of love and redemption. Their lives remain a testimony to the effects that the fruit of the Spirit, borne in ordinary lives, can have on others both near and far in proximity for the glory of God.

As an American conservative in the pre-political and dispositional sense of the word, I am persuaded that the best way to argue a point is to rely on concrete examples rather than on abstractions. Too often, we moderns tend to make abstractions of our love of God and love of country. God and country are not merely expressions with no viable substance, and love for God and country are not just sentiments fit either for kitschy patriotic church services or riots at the US Capitol. Both love of God and love of country involve actual and active love of real persons. God, as the ground of all being, is the source of both our existence and our salvation. We love him because he made us and he saved us. We owe him our whole devotion because of who he is as the sovereign Lord of Creation and as the divine-human savior of his elect. We were created to worship him and to enjoy him in our love for him, expressed in contexts of gratitude, obedience, and suffering. We learn how to love the Lord in everyday experience. We have instruction on how to love the Lord in the preaching and teaching of the Bible in the local church and through spiritual disciplines like meditation on the Bible, prayer, giving, and serving. An orthodox and thoroughgoing ecclesiology will bear fruit in individual Christians of a congregation who love the Lord by walking with him and trusting him each day.

Speaking as an American citizen, it is good to love the United States of America, a real country made up of real people with whom we interact each day in the most ordinary of ways. Our love for our country begins with love and loyalty to those closest to us: the members of our households. As children, we learn to honor our fathers and mothers, and we learn our place in the family hierarchy. Edmund Burke famously saw the family as the basis of all levels of society, the “little platoon” to which we first belong. Burke also saw the family as going far

beyond just the nuclear family, in that families and societies extend broadly in space and time. Society, Burke wrote, is “a partnership” between “those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” We learn how to love others by practicing self-denial in real time from our earliest childhood. We also come to know the stories about our ancestors when we are children, and those traits they had that are worthy of emulation and those that are not. We come to understand that those who went before us made us who we are. As we grow, we learn how to live with people who are not like us, who do not always agree with us, who do not see the world as we do, but with whom we can nonetheless enjoy friendship and cooperation.

Our love for our own people starts with those in our families and extends out to those in our local associations, our towns, counties, and cities, to our states, and finally to our country. When we see the flag of the United States, we know it is not just a piece of fabric, nor does it stand for some abstract nationalistic trope. The flag represents the people that make up the nation—those who are dead, those who are living, and those who are yet to be born. When we think of “the American people,” we include our ancestors: actual people who stewarded our country and handed it down to us as an inheritance. We consider that it is our responsibility as the living to take care of that inheritance and prepare to hand it down to our children and grandchildren.

The category of “the American people” starts with those I see in the kitchen as I make coffee in the morning, and it extends outward in proximity as I go about my day. Thus the abstract expression of “the American people” becomes concrete from the perspective of proximity. The people I live with in my home, church, school, ball league, and town are my people. I know my people well because I see them, work and play with them, suffer together with them, rejoice with them, teach them, am taught by them, forgive them, and seek forgiveness from them in small and great ways every day of my life.

So, too, are our loves ordered starting with God, who is one in three persons and as real as the air I breathe. My country consists of real persons who are as real as I am. We can think of a right ordering of love in terms of the old Sunday school acrostic song,

J-O-Y, J-O-Y, this is what it means: Jesus first, yourself last, and others in between!

Such an ordering of loves is the basis for patriotism. Patriotism is a rightly ordered love of country that comes from gratitude and joy in the good gifts God has freely given by his grace. As Papa used to say, rightly ordering our loves is one of those things in life that “ain’t hard; it just ain’t easy.”

There is a popular idea that America is God’s chosen nation, superior in rank to inferior peoples, and commissioned by God to act on inferior peoples as it will—this is one kind of American nationalism. I have referred to this idea as an expression of closed American exceptionalism. It is not the only expression

We can be grateful to God for our country, cherish it, and strive to faithfully steward this gift to prepare it for the coming generations.

of American nationalism, nor is it unique to Americans. Germans, Russians, French, English, Italians, Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Japanese, and Chinese have all had similar expressions across generations, as have the many tribes and nations of indigenous peoples in the Americas and Africa. Why? Because human nature is sinful and seeks to set the self as the final arbiter of that which is right and true. It is human nature to exalt the self and debase others. Americans have done it—as has every society since Cain. Closed exceptionalism amounts to national idolatry, and Americans no more invented idol worship than they invented closed exceptionalism.

Closed exceptionalism must be sharply contrasted with what I call open exceptionalism. In open exceptionalism, we Americans gratefully recognize that ours is a great country because of its unique contributions to human freedom, one of the most profound aspirations of creatures made in God’s image. The history of the United States is a story of the advancement of freedom, not only within our own borders but around the world. No other country has done more for the advancement of freedom than the United States since 1776. Such an acknowledgment does not mean we should equate America with ancient Israel, nor does it mean that God has specially chosen America over other nations to do his will. It does mean, despite its failures in its national lifespan, that America has been a spectacular blessing to the world. We can be grateful to God for our country, cherish it, and strive to faithfully steward this gift to prepare it for the coming generations.

Closed exceptionalism is problematic for its chauvinism and appropriation of theological categories reserved for the church, like chosen-ness, mission, and regeneration. Like most problematic ideas, however, closed exceptionalism is rarely as simple and recognizable as, say, bowing down in worship to the American flag. Sin usually mixes some truth with error, as we plainly see in the first sin of Adam and Eve in Genesis 3. For this reason, guarding against making one’s nation into an idol entails deep knowledge of and sincere submission to the Bible. If we allow ourselves to be ignorant of what the Bible says about God and his will for his creatures, then the Bible can become nothing more than a symbol, a talisman we carry into the public square. Ignorance of the Bible can easily lead to idolatry because it renders us unable to extract the precious from the vile, as God exhorted the prophet Jeremiah (15:19). When we are ignorant of God’s word, we reject knowledge and the moral correction that attends it, making us stupid (Prov. 12:1). Ignorance and stupidity lead directly to idolatry, and as we wallow in our stupidity, we are like the idolater of Isaiah 44:20 who “cannot deliver himself, nor say, ‘Is there not a lie in my right hand?’”

Christians come to know God through consistent meditation on Scripture. True knowledge of God necessarily results in love and submission to him. Such love and submission result in the application of Christian virtues in dealing with the thorny problems that attend American nationality. Closed exceptionalism is one of those problems: the making of America into an idol. We’ve had hosts of other historical problems: slavery and Jim Crow, unjust territorial expansion,

injurious treatment of immigrants, profligate waste of material resources, illusions of national innocence and grandeur, and many other sins of collective commission and omission. What are we to do with these? Does not the “Redeemer Nation” itself need to be redeemed?

We are often told that America is unworthy of the faith our ancestors placed in it, and since we are more enlightened than they, we are in a better position— even morally obligated—to be fundamentally skeptical of the American project and refrain from patriotic expression in the interest of faithful Christian testimony. This is a form of throwing the baby out with the bathwater. Such an attitude is born out of yearning for too-simple explanations of human nature. It is a form of self-exaltation. The proper response for American Christians, I believe, is to patriotically embrace open exceptionalism in rejecting closed exceptionalism.

We see in fallen human nature a tension between two opposing realities. On the one hand, we are made in the image of God. God made persons “a little lower than the angels” and crowned humankind “with glory and majesty,” as David wrote in Psalm 8. At the same time, “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom. 3:23), and our “sins have hidden his face . . . so that he does not hear” (Isa. 59:2). We bear unspeakably profound dignity because God made us in his image, but we also bear an unanswerable weight of guilt and shame because of our sin for which only God can make atonement. He has made atonement for sin through Jesus Christ, but even the reality that Christ’s work of atonement is finished does not erase the tension between human dignity and human fallibility in time and space. The immature mind cannot bear to find a way to hold two opposing realities in tension together, but the mature mind understands that the greatest exemplar of justice and wisdom this side of the incarnation can be a great sinner who is nevertheless worthy of emulation. Immaturity fosters an imagination that can only see unending conflict between purity and stain, with no possibility of redemption. Wisdom discerns how best to hold dignity and fallibility in tension: when to celebrate a noteworthy person and why. Much of the rejection of rightly ordered patriotism in our day is childish. Since immaturity naturally exalts the self at the expense of others in a zero-sum equation, the immature mind is always in search of ways to silence perceived threats to its own illusions of grandeur. The wisdom and charity of a fully formed conscience understands the self as the chief of sinners as the apostle Paul did (1 Tim. 1:15). The virtuous search for truth in history by the wise yields deeper wisdom still.

The earliest record of the phrase “throw the baby out with the bathwater,” from Narrenbeschwörung (Appeal to Fools) by Thomas Murner, 1512.

Every American who has ever lived has had the same fallen human nature. The closed exceptionalist exalts the glory and honor in America over and against the sin. The cynic focuses on American transgressions over the examples of virtue and dignity in the national story. Both the closed exceptionalist and the cynic are making a false choice. Neither can hold human nature in tension, nor can

Christians do not hide their faces from their heroes’ sins but consider them honestly and patiently. We seek, in the spirit of Christian charity, to rejoice with the truth and not in unrighteousness (1 Cor. 13:6).

they reconcile the tensions between dignity and fallibility in history. They only see purity or stain. The open exceptionalist patriot—that is, the citizen with a rightly ordered hierarchy of loves—can reconcile that tension by exalting God the Creator and Redeemer first, others second, and the self last.

The patriot can honor and even revere figures like George Washington, who was a slaveholder, and Martin Luther King, Jr., who was an adulterer, by celebrating the virtues they represented while nevertheless recognizing that greatness in a person often manifests itself in great sins. Christians do not hide their faces from their heroes’ sins but consider them honestly and patiently. We seek, in the spirit of Christian charity, to rejoice with the truth and not in unrighteousness (1 Cor. 13:6). At the same time, we recognize moral and spiritual greatness when we see it, celebrate and extol such greatness, and bend our energies to preserve the memory of those that had it, imitating them in our lives. In doing so, faithful Christians in this country must sift American traditions through virtue and prepare to hand down tradition as a trust to the next generation so that they may enjoy the blessings of a nation that is truly great, though certainly not perfect.

In this way, the open exceptionalist patriot is the most grateful person in society. Gratitude is at the heart of rightly ordered patriotism because the Christian patriot understands that every good and perfect gift proceeds from God who works to bring life from death, joy from despair, victory from defeat, salvation from reprobation, and truth from falsehood. Any national blessings we inherited did not come from our own efforts but are a trust handed down to us by someone else who had our best interest in mind.

Antique map of United States of America, 1846, with the Republic of Texas

Even on this side of the eschaton, we can call the United States a great country—even despite its manifold flaws. We celebrate the things in its story that are worthy of celebration without a blushing face. We do not fear those who would mock or condemn us for rejoicing in those things that are true, honorable, right, pure, lovely, and of good report (Phil. 4:8). We are not cowed by the shrill voices emanating from those who cannot hold two opposing realities in tension. Still, we are realistic about fallen human nature, and how it is constantly disposed to worship created things as if they were gods. Because we know ourselves better than anyone else, and because we know that sin is common to all, we know from experience that even the most celebrated heroes had hearts that were “deceitful above all things and desperately sick” (Jer. 17:9). Patriots know that the dead still speak, their deeds outlive them, and we are who we are in great measure because of the consequences of their lives and actions. We get wisdom from

taking the meaning of their lives seriously, rather than committing self-inflicted amnesia and intellectual suicide by cancelling those who make us uncomfortable.

My grandfather was a man with a nature like mine. He was a sinner, but he knew his need for a Savior. He understood that he could have no salvation apart from the atonement Christ made for him on the cross. As a young man, he found that to know Christ was to love him and that loving Christ meant receiving with joy and thanksgiving the good gifts the Lord graciously gave him. Solomon wrote in Ecclesiastes 2:24–25, “There is nothing better for a man than to eat and drink and tell himself that his labor is good. This also I have seen that it is from the hand of God. For who can eat and who can have enjoyment without Him?” My grandfather—a great yet flawed husband, father, grandfather, friend, churchman, patriot, and public servant—understood this as well as anyone I have ever known. He was a true patriot and, though dead, he still speaks.

My grandfather followed the example of the Lord Jesus who perfectly demonstrated rightly ordered love in the way he taught his disciples to pray in the Lord’s Prayer (Matt. 6:9–13). We start by hallowing God in our hearts and minds, because all our acts of love are predicated on God first loving us (1 John 4:19). We seek first his kingdom, because in doing so, we demonstrate that our first love is for Christ and his ways (Matt. 6:33). We further demonstrate our desire for our earthly kingdom, America, to reflect the righteousness of the kingdom of God, even though we are realistic about our fallen world and we know we won’t usher in God’s kingdom by our own works. Nevertheless, Christians should bend all their energies toward directing the nation in ways that are pleasing to God. In all this, we Christians are ever aware of our own faults and our need for forgiveness. We know that we are fallible, and we embrace our convictions with humility. As we seek forgiveness for ourselves, we forgive others. The nation can and should be built on such a righteous foundation. True patriotism is possible only when worship, loyalties, and loves are directed rightly.

John D. Wilsey is professor of church history and philosophy and chair of the Church History and Historical Theology Department at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky.

Christians should bend all their energies toward directing the nation in ways that are pleasing to God. In all this, we Christians are ever aware of our own faults and our need for forgiveness. We know that we are fallible, and we embrace our convictions with humility.

by Hannah Abrahamson

I watched a boat split water clear and calm Across the lake one night at summer’s end; The ripples, strong and fading fast, bent light In semi-circles, bright and diamond-edged. The lake looked black except for copied trees, Reflected on the surface of the mere: Evergreens, with boughs of woven threads, And maples, decked with rows of whis’pring leaves. I watched in silent reverie until That which was faint revealed itself to me, So still, yet beck’ning me to come along, To live just like the waves that bend the trees: Each life begins with ridges strong and sure, But they fade fast as evil takes its toll; And yet, their endings glitter in the light With wisdom, given in this earthly veil.

Connecting with our time and place

by QUINN SLOAN

EARLY ONE MORNING , a man finds himself stuck in Southern California traffic on his way in to work. He lives north of the city but drives to his downtown office every day. Every morning, he finds himself in the heart of rush hour traffic, surrounded by others who commute to their job from outside the city. On this morning, the highway looks more like a parking garage than a road. “Unbelievable!” the man exclaims. “I could walk faster than this!” This is what media ecologist Marshall McLuhan would call the reversal of new technology: When pushed to its limits, technology may revert to an older medium, or its user may wish for the older ways.

McLuhan argued that all technology is useful as an extension of the human body and that “all media are extensions of some human faculty—psychic or physical.” 1 The telephone, for example, is an extension of the mouth, allowing the human voice to reach farther and wider than ever before. The automobile serves as an extension of the human foot—think Fred Flintstone’s anachronistic town of Bedrock where the cars have no bottom. Instead of pressing the gas, the driver uses his feet to propel the car forward, his legs doing all the work. The technological advancement of the automobile replaces the need for Fred to run while seated. The car has become an enhancement of the human foot, and the man stuck in traffic has greatly helped his commute to work by connecting his foot to the gas pedal of the car. While it may be true that he could walk faster than his car in the heavy early-morning traffic, the same man would likely not wish away his car altogether. The car has become far too valuable to his lifestyle. In the same manner that we can evaluate technology as an extension of the human body, so McLuhan argues that we can analyze technology by comparing it to prior technology.

In Understanding Media (1964), McLuhan suggests that we’re often so distracted by the medium’s message or content, we don’t question the influence of its medium. The solution is to evaluate the effects of the medium. McLuhan says he has found that “everything man makes and does, every process, every style, every artefact, every poem, song, painting, gimmick, gadget, theory, technology— every product of human effort—manifested the same four dimensions” or effects of the new medium.2 These four dimensions are important effects in relation to old media and technology. In Laws of Media: The New Science, McLuhan analyzes the four effects at length: New media and technology enhances, retrieves, reverses into, and obsolesces the old technology. This tetrad can expose new media’s unobserved qualities. Each of these effects must be evaluated in order to consider how new media is utilized and how it brings change to the modern world. Moreover, McLuhan writes, “The tetrad is exegesis on four levels, showing not the mythic, but the logos-structure of each artefact, and giving its four ‘parts’ as metaphor, or word.” 3 Each technological advancement can be expressed as a medium through

the Father sent

both as the medium of his love for us and the message communicating his love; “in Jesus Christ, there is no distance or separation between the medium and the message: it is the one case where we can say that the medium and the message are fully one and the same.”

which the messages of enhancement, retrieval, reversal, and obsolescence are expressed. As his famous quip goes, “The medium is the message.”

Though the medium often functions as the message (and vice versa), there is but one example where the medium and the message are one and the same. God the Father sent his Son Jesus Christ both as the medium of his love for us and the message communicating his love; “in Jesus Christ, there is no distance or separation between the medium and the message: it is the one case where we can say that the medium and the message are fully one and the same.” 4 The Son of God is the perfect medium expressing the perfect message, that “in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation” (2 Cor. 5:19 ESV). Since, as McLuhan recognizes, “Christ is the ultimate extension of man” and all technology is an extension of man, we can consider the tetradic effects of Jesus Christ’s life, death, and resurrection.5 This, however, leads to the question: What is the old media or technology that Jesus Christ enhances, retrieves, reverses into, and obsolesces?

This essay will attempt to consider Christ’s tetradic effects as the perfect medium, with the old medium in question being the Old Testament sacrificial system. Whereas the way to make oneself right before God was once the old covenant sacrificial system, the new way is by grace alone, through faith alone, in Jesus Christ alone. Although McLuhan may have first put to words to the tetrad, tetradic analysis of new media has been under way in some shape or form for years. Using Hebrews 10 as the source code, we will explore Jesus Christ as the new media and the tetradic effects of enhancement, retrieval, reversal, and obsolescence of the old media, the sacrificial system.

McLuhan’s tetrad of media effects seeks to answer the following questions: What does the new medium enhance in past media? What does the medium retrieve that was once made obsolete? In its extreme state, into what does the medium reverse, or what does it become? And finally, what does this new medium obsolesce going forward? Each of these complete tetrads “gives the etymology of its subject . . . and provides its anatomy in fourfold exegetical manner.” 6 These effects have no chronological order deriving from each medium; all parts are simultaneous. Each effect, while equally present in every advancement, “may appear more readily in some tetrads than in others, [while some] suggest the need for a little more tuning.” 7

The tetrad can be dissected for any new form of media. It can reveal its effects in comparison with new media or as an extension of humanity. McLuhan offers the cigarette as an example of the latter: It enhances calm and poise while providing a burst of nicotine and giving smokers something to do with their hands. It retrieves a sense of community and ritual as a ritualistic and often communal

activity. Look no further than the smoking section of any public place to see both group security and the ritual of smoking taking shape. It makes obsolete the feeling of awkwardness and loneliness, because smoking gives you something to do and is often done in groups.8

While cigarettes may be a simple medium to analyze for its tetrad, we can see how all four effects are upheld in even the most complex medium. Hebrews 10 reveals how Jesus: (1) enhances the role of priest in his sacrificial work by his payment for sins once for all; (2) retrieves the foretold new covenant and christological prophecies from the old covenant; (3) when rejected, reverses into the old covenant sacrificial system that demanded an unattainable perfection; and finally, (4) obsolesces the need for daily sacrifices in order to be right before God.

The first of Jesus’ effects of the old covenant sacrificial system shown is enhancement (Heb. 10:1–4; 11–14). Christ enhances the old covenant priest in two ways: Christ’s qualifications are better, and his functions are better. Although this study is mostly limited to Hebrews 10, Christ’s better qualifications are clear throughout the book. Jesus’ personal holiness is greater than that of the previous priests for he is the Son of God, “holy, innocent, unstained . . . made perfect forever” (Heb. 7:26–28). Jesus enhances the priestly sacrifice because of his better functions, which are twofold: Christ’s sacrifice for cleansing, and Christ’s intercession at the right hand of God.

Illustrations based on the detailed descriptions of the tabernacle and temple.

Christ is a better intercessor than the high priests. High priests could enter the Most Holy Place in the temple, but no high priest was able to sit at the Father’s right hand. Only the perfect, greater high priest could do that: Jesus remains at the right hand of the Father, interceding for us forever.