Go and Make Disciples

12 Jesus’ Greatest Disciple | by Michael Horton

20 Baptism as Discipleship: A Conversation with Jared L. Jones | by Brannon Ellis

30 Liturgy as Discipleship: How God Makes Disciples through Word and Sacrament | by John Bombaro

44 From Dragons to Disciples: What Lewis and Tolkien Teach Us about Making Disciples | by Andrew Menkis

VoL. 33, No. 4

July/August 2024 $9.00 per issue

MODERN REFORMATION THINKING THEOLOGICALLY

Modern Reformation Unlocked

AD

GETTING THE GOSPEL RIGHT AND GETTING THE GOSPEL OUT

Because of the support of our subscribers and the generosity of our partners, we’re excited to announce that the entire Modern Reformation archive is now accessible to everyone. For free. Enjoy unrestricted digital access to over thirty years of thinking theologically. Share with everyone you know who longs to grow in knowing God and his word. And if you don’t already, please consider partnering with us to continue this crucial work.

A Production of Sola Media

PARTNER WITH US → MODERNREFORMATION.ORG/GIVE

| From Dragons to Disciples: What Lewis and Tolkien Teach Us about Making Disciples | by Andrew Menkis

BOOKS Family Worship & Discipleship Resources: A Brief Bibliography | by Jonathan King 5 FROM THE EDITOR | by Brannon Ellis

25 Two Robes (The Pain of an Answered Prayer) | by Andrew Menkis 26 Soil Sorrows | by M. C. Fox 40 Poiema | by Michael R. Ritt

55 We Shall Be | by Isaac Fox 56 BACK PAGE The Great Commission from Genesis to Revelation | by Brannon Ellis

Modern Reformation July/August 2024 Vol. 33, No. 4 Endsheet illustration by Raxenne Maniquiz

Contents

Officer Eric Landry | Executive Editor Brannon Ellis | Managing Editor Patricia Anders

Poetry Editor

Editor Kate Walker | Proofreader Ann Smith | Creative Direction and Design Metaleap Creative

Modern Reformation (Subscriptions) 13230 Evening Creek Dr S Ste 220-222, San Diego,

| Subscription Information: US 1 YR $48. Canada add $10 per year for postage.

Modern Reformation is a publication of Sola Media I. RETRIEVE 8 REFORMATION RESOURCES

12

II. CONVERSE 20 INTERVIEW

III. PERSUADE 30

IV. ENGAGE 44 ESSAY

54

Editor-in-Chief Michael S. Horton | Chief Content

|

Jonathan Landry Cruse | Production Assistant Anna Heitmann | Copy

Modern Reformation © 2024. All rights reserved. ISSN-1076-7169 |

CA 92128 (877) 876-2026 | info@modernreformation.org | modernreformation.org

Overseas add $9 per year for postage.

| Baptism and the Great Flood Prayer | by Zachary Purvis

ESSAY | Jesus’ Greatest Disciple | by Michael Horton

| Baptism as Discipleship: A Conversation with Jared L. Jones | by Brannon Ellis

ESSAY | Liturgy as Discipleship: How God Makes Disciples through Word and Sacrament | by John Bombaro

POETRY

Partner with MR

THEOLOGY MATTERS

No other magazine brings together confessional Lutheran, Anglican, Reformed, and Baptist representatives to discuss the significant biblical and cultural issues of our day. We’re committed to helping you hone your theological thinking and share your insights effectively with others. Your support allows Modern Reformation to keep this conversation going strong.

A Production of Sola Media

SUPPORT MR → MODERNREFORMATION.ORG/DONATE Vol. 31, No. January/February 2022 Fundamentalism & American Evangelicalism 20 What Has Become of American Fundamentalism? | 40 Rethinking How We Think about the Evangelical Mind and the Local Church | by Charles E. Cotherman 56 Fundamentals for the Evangelical Future | by Daniel J.Treier MODERN REFORMATION MARCH/APRIL 2022 THE EVANGEL VOL. 31, NO. 2 March/April 2022 The Evangel Anglicans and the Gospel | Bad News and Good News: The Gospel According to Luther What Is the Gospel? A Baptist Perspective | by Michael A. G. Haykin Evangelicals and the Evangel Future | by Michael Horton MODERN REFORMATION MODERN REFORMATION MAY/JUNE 2022 EVANGELICALS THE BIBLE VOL. 31, NO. 3 May/June 2022 $9.00 per issue Evangelicals & the Bible 10 Learning to Read Scripture Like the Church Fathers by Craig Carter 36 Everything in Nature Speaks of God: Understanding Sola Scriptura Aright | by Jordan Steffaniak 54 Restoring Eve | by Kendra Dahl

JESUS CAME AND SAID TO

[the eleven], “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age.”

(Matt. 28:18–20)

It’s all here. The universal rule of the resurrected Lord. The mystery of the Holy Trinity. The foundational authority given to the apostles and those called to teach and baptize according to their testimony. A community of faith reconciled to God and one another through word and sacrament. The mission of God’s people to carry the gospel into all nations, empowered by Christ’s faithful presence with us always—one Shepherd leading one flock. Virtually all of Christianity is contained in Matthew’s last recorded words from Jesus to his apostles in Galilee.

In this issue, we’re exploring the church’s calling to be disciples of Jesus and to make disciples of Jesus. It’s a high and holy calling, which tempts us all the more as committed Christians either to oversimplify discipleship or overcomplicate it.

We undercomplicate things when we pretend that making disciples is—as Charles Finney infamously defined conversion and revival—“a purely philosophical result of the right use of constituted means.” God’s ways, like his character, are beyond our comprehension or control. No sinner ever was, or made someone else, a true disciple of Jesus Christ except by the life-giving wisdom and power of God alone.

But we also overcomplicate things. Although I hate to agree in any sense with Finney, a fruitful life of Christian discipleship is indeed “the result

of the right use of constituted means.” But these means couldn’t be any further from “purely philosophical”—in fact, the means by which God transforms us are the very things we most readily abandon as irrational, ineffective, or even irresponsible in our relationships with one another.

Even experienced Christians struggle to see the misery and indignity of the cross as supremely wise and powerful—as supremely effective instruments in the hands of our Father to renew us little by little in the image of his Son. In the dirty work of our spiritual discipleship, grace and love are God’s go-to power tools, yet we always seem to reach for them last. There must be something more effective at changing minds and hearts than words, worship, water, bread, and wine, right? How easily we forget the wisdom of undeserved forgiveness, how little thought we give to the mountains moved by mustard-seed-sized faith!

So, as we follow and learn from our Lord, like silly sheep attempting to guide others on the same journey, let’s refuse to overcomplicate or oversimplify the work of being a disciple or making disciples. Let’s focus instead on following our Good Shepherd together, watching him as he watches over us while he accomplishes everything for his glory and our good. After all, “It is God who works in you, both to will and to work for his good pleasure” (Phil. 2:13). And what is his good pleasure? Nothing less than to give his little flock the kingdom (Luke 12:32).

Brannon Ellis Executive Editor

Brannon Ellis Executive Editor

5 MODERN REFORMATION From the Editor

Retrieve

Learning from the wisdom of the past

7 MODERN REFORMATION Vol. 33, No. 4

I.

REFORMATION RESOURCES

Baptism and the Great Flood Prayer

by Zachary Purvis

IN 1523, MARTIN LUTHER TRANSLATED the baptismal form out of Latin and into German. He presented the product of his labor, the Baptismal Booklet (or Taufbüchlein), for use in the church. Suddenly, Reformation liturgy became intelligible. True, it was not a full revision of the liturgy. Luther’s own attempt at that, which did not come until late 1525, built on some earlier suggestions he had made the year before. Nor was it even a substantial revision of the Latin baptismal rite, which Luther undertook only in 1526.1 The early Reformers often had to “hasten slowly” ( festina lente ). 2 But it did offer a liturgical text that made possible the celebration of the sacrament of baptism in the common language of the people. More than that, it contained the Great Flood Prayer (or Sindtflutgebet), beloved and still used by numerous confessional traditions even today. “Viewed in terms of biblical imagery, liturgical history, and pastoral sensitivity,” confirmed Hughes Oliphant Old, “Luther’s prayer is a masterpiece.”3

Scholars have repeatedly pounced on Luther’s Baptismal Booklet like archaeologists at the dig site. With backhoe and trowel, they have tried to excavate conceivable medieval sources for the liturgical text and patristic sources for the Great Flood Prayer itself: the 1497 Latin rite for the archdiocese of Magdeburg, the 1502 agenda for the diocese of Ermland, the writings of Saint Augustine, the works of Isidore of Seville, the treatises of Rupert of Deutz, and still possibly more.4 This behavior is understandable, because some of the changes Luther initially made to the baptismal form can seem peculiar, both in light of standard liturgical books and Luther’s later accomplishments.

First, Luther removed some, but not all, of the exorcisms practiced in baptism. Medieval exorcisms had come to replace patristic prayers of confession and repentance. Those that Luther cut significantly shortened the baptismal service. Second, he omitted the medieval admonition to godparents, seemingly to declutter the service. He also omitted the medieval catechetical instruction, such as use of the Apostles’ Creed, the Ten Commandments, or the Ave Maria as part of the baptismal service, but he retained the Lord’s Prayer because he understood the Lord’s Prayer at the time as a prayer

8 July/August 2024

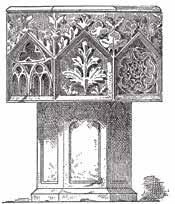

A woodcut from a 1545 edition of Luther’s Small Catechism depicting infant baptism

for the blessing of the child. The third change came by addition when Luther inserted the following words:

Almighty eternal God, who according to thy righteous judgment didst condemn the unbelieving world through the flood and in thy great mercy didst preserve believing Noah and his family, and who didst drown hardhearted Pharaoh with all his host in the Red Sea and didst lead thy people Israel through the same on dry ground, thereby prefiguring this bath of thy baptism, and who through the baptism of thy dear Child, our Lord Jesus Christ, hast consecrated and set apart the Jordan and all water as a salutary flood and a rich and full washing away of sins: We pray through the same thy groundless mercy that thou wilt graciously behold this N. and bless him with true faith in the spirit so that by means of this saving flood all that has been born in him from Adam and which he himself has added thereto may be drowned in him and engulfed, and that he may be sundered from the number of the unbelieving, preserved dry and secure in the holy ark of Christendom, serve thy name at all times fervent in spirit and joyful in hope, so that with all believers he may be made worthy to attain eternal life according to thy promise; through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.5

Long and comprehensive, the prayer both replaced and recast some of the standard Latin baptismal prayers, such as Deus patrum nostrorum and Deus Abraham, with a greater sense of biblical typology as appropriate to baptism and a richer account of Christian interpretation of the Old Testament, including 1 Peter 3:20–21 on Noah and the Flood and 1 Corinthians 10:1–4 on Israel’s baptism through the Red Sea.6 In liturgical-theological terms, the remembrance of God’s mighty deeds in history or “anamnesis” is employed to great effect.

The inclusion of the Great Flood Prayer also added balance to the service. Precisely because Luther understood baptism to principally be the work of God, who makes life-giving promises to the one baptized, the invocation or “epiclesis” in the baptismal form finds real meaning. 7 Luther instructed the participants: “See to it, therefore, that you are present in true faith, listen to God’s Word, and earnestly join in prayer.” He also admonished the minister to say the prayer “very clearly and slowly” so that all parishioners could hear, understand, and pray in their hearts along with him, “carrying the little child’s need before God most earnestly.”8 Baptism was personal but not private.

In 1526, Luther revised the baptismal form again. Now the prayer took greater precedence over the exorcisms, which focused increasingly on the Christian’s struggle against the devil in spiritual matters.9 As Luther put it in the Small Catechism of 1529, “The old person in us (Adam) with all sins and evil desires is to be drowned through daily sorrow for sin and repentance, and that daily a new person is to come forth and rise up to live before God in righteousness and purity forever.”10 Because it was God who made promises in the sacrament, baptism was to be remembered and embraced each day of the believer’s earthly pilgrimage to provide comfort amid temptation and despair as it reminded one of God’s

Baptism was personal but not private.

9 MODERN REFORMATION Retrieve

Because it was God who made promises in the sacrament, baptism was to be remembered and embraced each day of the believer’s earthly pilgrimage to provide comfort amid temptation and despair as it reminded one of God’s effective word by which he brings sinners from death to life.

effective word by which he brings sinners from death to life. Not only did Luther regularly say “Remember your baptism!” but also that there is “no greater jewel” in the Christian life.11

The afterlife of the Great Flood Prayer is also remarkable. Use of the prayer spread as the implementation of Lutheran church orders and liturgical forms carried it across central Europe. But it was not limited to German Lutherans. The prayer quickly entered the liturgies of Scandinavian Lutherans. It was amended by Leo Jud and Huldrych Zwingli for use in Switzerland, with the new version leaving out reference to Christ’s baptism in the Jordan or the consecration of baptismal waters. The Reformed liturgy in the Netherlands also adapted Luther’s prayer by incorporating into it an explicit understanding of the sacrament as covenantal sign and seal. In England, Thomas Cranmer inserted part of the prayer into the order for baptism in the Book of Common Prayer.12 As a result, the prayer has found a home nearly across the globe. These liturgical forms reworked the prayer, but each instance of reception preserved the central features: the prominence of the biblical types of Noah and his family in the ark and Israel’s exodus from Egypt, the strong accent on God as the one who works in the sacrament, and the importance of calling upon the Father, in the Son, by the Spirit for aid, both in that moment of the service and in every moment of the life of the one baptized. Finally, the Great Flood Prayer arguably made an implicit appearance at the end of Luther’s life, twenty-three years after he had composed it. In late January 1546, Luther travelled to Eisleben to resolve an inheritance dispute between two brothers in the Mansfeld Count family. On the way he stopped in Halle, where

1. For the 1523 and 1526 forms, see Martin Luther, Luther’s Works , ed. Helmut Lehmann et al., 55 vols. (St. Louis: Concordia; Philadelphia: Fortress, 1958–86), 53:96–103 and 106–19 (hereafter LW).

2. On the broad application of this to liturgical reform, see Jonathan Gibson and Mark Earngey, eds., Reformation Worship: Liturgies from the Past for the Present (Greensboro, NC: New Growth Press, 2018).

3. Hughes Oliphant Old, The Shaping of the Baptismal Rite in the Sixteenth Century (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1993), 37.

4. The most recent extensive search (with an overview of the

literature) is Kent J. Burreson, “The Saving Flood: The Medieval Origins, Historical Development, and Theological Import of the Sixteenth Century Lutheran Baptismal Rites” (PhD Diss., University of Notre Dame, 2002).

5. LW 53:97.

6. For Luther’s understanding of John’s baptism of Jesus in the Jordan, see Lorenz Grönvik, Die Taufe in der Theologie Martin Luthers (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1968), 68–72.

7. For Luther’s doctrine of baptism, see, e.g., Jonathan D. Trigg, Baptism in the Theology of Martin Luther (Leiden: Brill, 1994);

10 July/August 2024

a sudden thaw had broken the winter ice on the Saale River and caused the river to flood its banks. Writing about the flood to his wife, Katie von Bora, Luther couldn’t resist a joke that personified the rushing waters as an angry Anabaptist who “threatened to baptize us again.”13 The traveling party escaped the deluge, but Luther soon took ill. From Eisleben he wrote home to reassure his wife:

You, dear Katie, go read John and the Small Catechism, about which you once said, “Everything in this book has been said about me.” For you prefer to worry about me instead of letting God worry, as if he were not almighty and could not create ten Doctor Martins, should the old one drown in the Saale. . . . Free me from your worries. I have a caretaker who is better than you and all the angels; he lies in the cradle and rests on a virgin’s bosom and yet, nevertheless, he sits at the right hand of God, the almighty Father.14

The Reformer died a few weeks later. Luther’s comments about the flood in Halle demonstrate an abiding confidence that the same God who had preserved Noah and Israel in the baptismal waters of judgment had also acted for him, personally, in the Lord Jesus Christ, guaranteeing the believer not a watery grave but a passageway to Zion on dry ground. He remembered his baptism.

Zachary Purvis (MAHT, Westminster Seminary California; DPhil, University of Oxford) teaches church history and theology at Edinburgh Theological Seminary.

Luther’s comments about the flood in Halle demonstrate an abiding confidence that the same God who had preserved Noah and Israel in the baptismal waters of judgment had also acted for him, personally, in the Lord Jesus Christ, guaranteeing the believer not a watery grave but a passageway to Zion on dry ground.

and Robert Kolb, “‘What Benefit Does the Soul Receive from a Handful of Water?’ Luther’s Preaching on Baptism, 1528–1539,” Concordia Journal 25 (October–November 1999): 346–63.

8. LW 53:102.

9. The theme of contending against the devil is a regular theme in Luther’s writings. See Heiko Oberman, Luther: Man between God and the Devil, trans. Eileen Walliser-Schwarzbart (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006); and Robert Kolb, Martin Luther: Confessor of the Faith (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 163–71.

10. Martin Luther, “Small Catechism,” in The Book of Concord, ed. Robert Kolb and Timothy J. Wengert, trans. Charles Arand et al. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2000), 359–62.

11. Timothy J. Wengert, Martin Luther’s Catechisms: Forming the Faith (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2009), 114.

12. Old, The Shaping of the Reformed Baptismal Rite, 37, 43–49, 227–48.

13. LW 50:286.

14. LW 50:301–2.

11 MODERN REFORMATION Retrieve

JESUS’ GREATEST Disciple

by MICHAEL HORTON

12

IDOUBT THERE WILL BE a sudden run on “What Would Mary Do?” bracelets after this essay is published, but I’m going to make the claim anyway: The Mother of our Lord is a wonderful yet far too often underappreciated model of discipleship among today’s heirs of the Reformation. In this brief essay, I don’t have space to survey the complex historical development of Marian theology or make the case for a reformational approach to honoring—yet not idolizing—Mary as the most biblically faithful path. Some traditions raise Mary dangerously high above the rank of a fellow disciple; others, in reaction, practically ignore her unique example in Scripture, which all faithful Christians should emulate. I want to focus much more narrowly on Luke’s account of the Annunciation, shedding light on three ways Mary is a particularly powerful example for every disciple of Jesus.

First, Mary is an example par excellence of a nobody who is made somebody by God’s electing grace in Christ. She was not born a privileged daughter of Herod or Pilate. Though she was a descendant of David (Luke 3:31), a daughter of Abraham in the Messiah’s promised bloodline, there were many others who fit the bill just as well. In contrast with the regal adornment she wears in medieval art, Mary acknowledges in her inspired song, the Magnificat, that God has looked on her “humble estate,” not on her worldly dignity or righteousness (Luke 1:46–55). Mary was just another Jewish girl from a nondescript family eking out a meager existence under Roman oppression during a corrupt political regime.

And yet one day, out of nowhere, the angel Gabriel announces to her, “Greetings, you highly favored one! The Lord is with you. . . . Do not be afraid, Mary, for you have found favor with God” (Luke 1:28, 32). To call someone favored by God was a common Hebrew expression announcing God’s gracious disposition toward his covenant people. While some have claimed that being highly favored signals that Mary must be more worthy than the rest of us, Luke means the very opposite: Gabriel doesn’t announce Mary’s worthiness, but God’s free grace!

Later, when Mary visits her cousin Elizabeth, who is pregnant with John the Baptizer, the baby leaps in her womb and Elizabeth shouts, “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the fruit of your womb!” While being “blessed” doesn’t mean Mary was sinless or contributed any merit for her own salvation or ours, neither does it mean she was merely “happy.” Being blessed by God isn’t just a subjective feeling; it’s an objective fact. Calvin comments,

She is justly called blessed on whom God bestowed the remarkable honor of bringing into the world his own Son, through whom she had been spiritually renewed. And to this very day, the blessedness brought to us by Christ cannot be the subject of our

The Mother of our Lord is a wonderful yet far too often underappreciated model of discipleship among today’s heirs of the Reformation.

13 MODERN REFORMATION Retrieve

“We cheerfully acknowledge [Mary] as our teacher, and obey her instructions and commands.”

praise without reminding us at the same time of the distinguished honor which God was pleased to bestow on Mary, in making her the mother of his only-begotten Son.1

For this reason, Calvin adds, Mary’s own words direct us to honor her as an example rather than adore her as a co-redeemer. “We cheerfully acknowledge her as our teacher, and obey her instructions and commands.” And what she teaches most powerfully is that God alone saves through faith in her Son: “My soul magnifies the Lord, and my spirit rejoices in God my Savior” (Luke 1:46–47).2

It is because of her Son that Mary is blessed. “God my Savior” is her child, gestating in her womb, made flesh from Mary’s genes and nourishment. In this sense, Mary is different from all other followers of Christ. “From now on all generations will call me blessed.” And Elizabeth confirms this by her greeting, “Who am I that the mother of my Lord should visit me?” Not exactly the usual welcome Mary experienced from a relative. Her special place in the history of salvation is not in question. However, she places herself on the side of the rest of us as recipients of God’s gift in Christ.

Second, Mary shows us that an honest disciple wrestles with hard questions in faith, trusting God for answers, provision, and guidance (vv. 34–37). It was not in judgment but in grace that God sent his heavenly ambassador with good news. Yet Mary responds to Gabriel with alarm and confusion. Luke writes, “But she was greatly troubled at the saying, and tried to discern what sort of greeting this might be.” She hadn’t been waiting for this message, thinking to herself, “Finally, after all my devotion, God has taken notice!” No, Mary is surprised— even troubled—by this announcement. A true disciple never entirely fails to be surprised by grace. Whenever we return to God’s promises, we should be amazed all over again at God’s goodness despite our unworthiness.

None of us, however, has experienced an announcement of God’s grace quite so astonishing as Gabriel’s to Mary:

“Behold, you will conceive in your womb and bear a son, and you shall call his name Jesus. He will be great and will be called the Son of the Most High. And the Lord God will give to him the throne of his father David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever, and of his kingdom there will be no end.” (vv. 31–33)

Gabriel brings the ultimate good news: Not only is the promised Messiah coming someday, but he’s coming now; not only will he be born of a woman, but he’ll be born of this woman. This is beyond comprehension. A few months earlier, Zechariah had asked Gabriel “how” in response to the announcement of his wife’s pregnancy. He was struck mute until John’s birth; Mary asks a similar question but receives no rebuke. “How will this be,” she asks, “since I am a virgin?” (v. 34). While the miracle of the virgin birth is of an entirely different order from the miracle of overcoming barrenness, that doesn’t seem to be the point. The point is that Mary questioned God’s word in honest trust rather than cynical incredulity.

14 July/August 2024

Because Mary asks a good question, she gets a good answer: The same Spirit who hovered over the lifeless oceans in creation to make them fruitful will “come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you.” Gabriel says her child’s birth will be an unparalleled miracle directly wrought by God himself. Yet he gives her more concrete confirmation to hold on to. He tells her to go to her cousin Elizabeth who “in her old age also conceived a son, and this is the sixth month with her who was called barren. For nothing will be impossible with God” (vv. 35–36).

The narrative of Zacharias and Elizabeth, and also of Mary, is a redrawing of the Elkanah and Hannah story of 1 Samuel 1:1–2:11. Like Sarah and Rebekah, Hannah was barren. The God who created the world ex nihilo likes to work wonders with nothing to work with but his word and Spirit. On the steps of the Tabernacle of God’s Presence, Hannah offered a desperate prayer: “O Lord of hosts, if you will indeed look on the affliction of your maidservant and remember me, and not forget your maidservant, but will give your maidservant a male child, then I will give him to the Lord all the days of his life, and no razor shall come upon his head” (v.11). She is praying for mercy that God would look on her affliction, not on her worthiness. Nine months later, she who was barren gave birth to Samuel, whose name means “Heard By God.” Upon presenting her son to Eli the priest, Hannah composed a song to the Lord:

“My heart rejoices in the Lord; my horn is exalted in the Lord. I smile at my enemies, because I rejoice in your salvation. . . . The Lord kills and makes alive; he brings down to the grave and brings up from the grave. The Lord makes poor and makes rich; he brings low and lifts up. He raises the poor from the dust and lifts the beggar from the ash heap, to set them among princes and make them inherit the throne of glory. . . . For by strength shall no man prevail. The enemies of the Lord shall be broken in pieces; from heaven he will thunder against them. The Lord will judge the ends of the earth. He will give strength to his king, and exalt the horn of his anointed.”

Like Hannah, Elizabeth is barren but receives a heavenly promise of a son and believes it. Also like Hannah, Mary is in no position to contribute to the fulfillment of this promise. This is sure evidence graciously given to confirm Gabriel’s words and to bolster Mary’s faith that God is powerful enough to keep his promises, no matter how surprising they may be or unlikely they may seem. Mary shows us that it’s not impertinent for us to seek understanding in faith, welcoming as much explanation and evidence as God will give us.

Third, Mary shows us that a disciple entrusts herself to God’s promises despite everything. Throughout biblical history, faithful disciples reply to God’s address, “Here I am.” It was a common idiom in court etiquette, the equivalent of “As you wish” or “I am at your disposal.” “Behold” in verse 38 is a Greek translation of this Hebrew idiom, “Here I am”: “And Mary said, ‘Behold, I am the servant of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word.’” This may strike

God is powerful enough to keep his promises, no matter how surprising they may be or unlikely they may seem.

15 MODERN REFORMATION Retrieve

in

us as a strange way of speaking: “Let it be to me according to your word.” But it underscores her acknowledgment that she was on the receiving end of God’s word and work. This promise from God gave her courage to walk the path he laid out for her.

For Mary, she had to think that this path would mean likely rejection by her fiancé and would leave a lifelong stain on her reputation. Yet Mary clung to the promise even when her own heart was pierced at her son’s crucifixion. All of us feel the tension as our lives don’t play out the way we might have liked them to, or we face suffering of one kind or another. Being able to say with Mary and the rest of the faithful, “Thy will be done”—to trust that God is good and loves us, and that his plan is ultimately for our salvation—that’s how he gives us courage to move forward with whatever he ordains for each of us. Faith in God’s promises in Christ, despite everything, underlies every step we take in this life’s pilgrim journey. We must not be afraid, for we too have found favor with God.

Michael Horton is editor-in-chief of Modern Reformation and the J. Gresham Machen Professor of Systematic Theology and Apologetics at Westminster Seminary California in Escondido.

1. John Calvin, “Commentary on Luke 1,” Commentary on the Gospel of Luke, Calvin’s Commentary on the Bible, 1:28–32, https:// www.studylight.org/commentaries/eng/cal/luke-1.html.

2. Calvin, “Commentary on Luke 1,” 1:28–32.

16 July/August 2024

Faith

God’s promises in Christ, despite everything, underlies every step we take in this life’s pilgrim journey.

17 MODERN REFORMATION Retrieve

II.

Converse

Exploring perspectives from the present

19 MODERN REFORMATION Vol. 33, No. 4

INTERVIEW

Baptism as Discipleship: A Conversation with Jared L. Jones

by Brannon Ellis

Rev. Jared L. Jones is rector at Holy Cross Episcopal Church in Sanford, Florida, in the diocese of White Horse Inn co-host Justin Holcomb. I’ve gotten to know Jared over the past year and a half, during which he’s written multiple pieces for MR (one co-written with Holcomb). We’ve begun working with Jared on exciting plans to host a conference together in early 2025.

In the Great Commission (Matt. 28:18–19), Jesus draws an intimate connection between making disciples and baptizing. Many of us think of baptism as the entrance into discipleship. As an Anglican, how do you relate the Bible’s teaching about discipleship, and the Christian experience of being a disciple of Jesus, to baptism?

The covenant sign was a sign God gave to Israel not just for entering his covenant but for learning how to live according to the promises he gave Abraham beginning all the way back in Genesis 12: “I will be your God, you will be my people, and through you all the nations of the world will be blessed. And here’s the covenant sign [circumcision] I’m giving to you so that you will always be able to remember this promise.” So, from the old covenant to the new, there’s a through line correlating circumcision with baptism as the sign of the covenant, along with a call to disciple those who receive the promises—from infants to adults—in how they must take that covenant on for themselves. If baptism is the beginning of the Christian life, then it should characterize our whole life. Baptism isn’t about you and me improving ourselves or working ourselves to a place where we can accomplish something. It’s you and me learning how to live according to a promise—to live resting on a promise that’s been freely given to us, just as God’s people have always done.

As you describe baptism as an entrance into discipleship that characterizes the whole of the life of a disciple, I can’t help but think of Deuteronomy 6. Verse 4 is the famous creed of the Old Testament: “Hear, O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one.” Then comes the call to follow him and train up the coming generation in the faith: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your might. And these words that I command you today shall be on your heart. You shall teach them dil-

20 July/August 2024

If baptism is the beginning of the Christian life, then it should characterize our whole life.

Rev. Jared L. Jones

igently to your children, and shall talk of them when you sit in your house, and when you walk by the way, and when you lie down, and when you rise,” and so on (vv. 6–9, 20–25).

Yes, and the Christian life is no different. Everything we do is built on a promise that God has given us. And where does he give me that promise? Is it just out there somewhere, abstractly available to everyone? If so, then how do I know he really promised me? Maybe the promise was good for my parents or for my friend or pastor, but how do I know it’s really for me? How do I assure my children that God’s promise is for them—directly by name? Baptism, as it’s been said, is putting the word into water and then putting that water onto someone. It’s wording a Christian into existence, right?

One of my favorite parts of my tradition’s liturgy for baptizing an infant comes right after we baptize the child in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It's when we take oil and place the sign of the cross on the child’s forehead and pronounce the child’s name. For example, we’ll say, “Jared, you are sealed by the Holy Spirit in baptism and marked as Christ’s own forever.” To me, this is a promise that God has claimed this child. And if my children belong to God, then I’m going to raise them to know that they belong to God. I’m going to teach my children what it means to belong to God, and if they stray, then I’m going to remind them as a church—and as a pastor and a father—that they need to repent and return, because they’ve been chosen by God in baptism. It’s all rooted in the word of promise God has given.

What is baptism’s day-to-day significance for people in your congregation?

Just like any promise, sometimes it doesn’t come to mind until you need it! When I’m doing a wedding, I always say that the vows the couple are taking aren’t so much for the “richer” and the “in health” and the other “better” times. You don’t generally need vows when things are going well. You need vows for “in sickness” and “poorer” and sin and all the other “worse” times. That’s when I must lean on the fact that I made a promise and that my spouse made a promise to me. I think baptism is the same thing. We don’t lean on it much until we really need it. Part of maturing as a Christian is realizing how often we do need it. Once you really start running into sin (your own and others’) or you feel like God has let you down or abandoned you, baptism becomes this bedrock, like a wedding ring. I’m allowed to pray boldly like the psalmists, “God, if you abandon me, you will be unfaithful to the promises you’ve made. God, if you abandon my child, you will be unfaithful to the promises you’ve made. So don’t do it, because you’re not unfaithful. You don’t lie. In my baptism, you swore that I belong to you.”

As a kid baptized at twelve in a Southern Baptist church, I remember it sounding odd the first few times I came across some famous Reformation writer encouraging those struggling with assurance to “remember your baptism.” All the people they were talking to were baptized as infants. How could they possibly remember it? I eventually realized that the strength of or even

Baptism . . . is putting the word into water and then putting that water onto someone. It's wording a Christian into existence.

21 MODERN REFORMATION Converse

Christian perseverance isn’t about achieving something big or conquering the world in the way we think that should look. . . . Conquering the world really means to remain faithful through a life that tries to pull you away from Jesus every chance it gets.

awareness of my faith should never be the ground of my assurance. Whether baptized as an infant or not, the ground of my assurance is that God claimed me in baptism; God is the one who baptized me. “Remember your baptism” really means “Remember that God remembers you.”

One of the people often used as an example of why baptism in and of itself doesn’t save you is the thief on the cross. Although he was never baptized, the thief’s prayer—“Jesus, remember me!”—is the cry of the baptized. I think that the whole Christian life begins with a promise and that most of the activity of the Christian life is really preparing ourselves to die with that promise. Christians live prepared to die within the covenant.

This sounds like the old saying, “Christianity is the art of dying well.” Or to put it in terms of what you’re getting at, being a disciple of Jesus is the art of preparing to die well.

We’re so disconnected from death and don’t think about it often. But death is a terrifying thing. If we really stop and think about the idea that everything that we are, everything that we think, everything that we’ve built, all of our identity—we have to let it all go. That can be a horrifying experience. Because in order to let all that go, you have to trust that something is going to be on the other side, that something about you matters more than all your activity and work and everything else you try to hold on to. It’s no small thing to try to live in preparation for actually dying as a Christian in comfort and peace, even joy. That kind of preparation takes effort, and I don’t mean to say that going to heaven is contingent on dying well. There are a lot of people who will wake up in bliss in the presence of the Lord after screaming the whole way there. And yet God is faithful to the promises that he made and that they trusted. But the work we do is really, I think, a work of how to begin to die every day, to where the final door you walk through is not as scary as it might be.

Often when we think about the Christian life, we imagine it consists in our explicitly spiritual or ministry-oriented activities. But maybe most of the Christian life is just what Paul describes in 1 Thessalonians: We should seek to live a quiet life, minding our business, and working with our hands (4:11). That’s a realistic vision of Christian discipleship, because sometimes the best thing you can do in life is just to get through it. Life is hard. Christian perseverance isn’t about achieving something big or conquering the world in the way we think that should look. According to the book of Revelation, conquering the world really means to remain faithful through a life that tries to pull you away from Jesus every chance it gets (2:25–26).

To me, these truths give an order for what church discipleship should look like. It’s not getting everybody onto a discipleship track with small groups and this or that program. Not that any of those things are bad, but the church should be focused on being there for the major life stages from birth to death. We’re there to prepare Christians to live and die, to help one another know the significance of our lives.

22 July/August 2024

Nowadays, we’re so obsessed with identity. We’re constantly encouraged or tempted (or flogged) into creating our own identity, and then recreating it once we get tired of it or we think we might not have gotten it right. But God forms our identity through ordinary word and water and bread and wine. What’s more salient to my identity than birth and death? This reminds me of Paul’s connection between death, life, and baptism: “Do you not know that all of us who have been baptized into Christ Jesus were baptized into his death? We were buried therefore with him by baptism into death in order that just as Christ was raised from the dead by the glory of the Father, we too might walk in newness of life” (Rom. 6:3–4). Just as life consists in being born and dying, so baptism consists in dying with Jesus and being born again to undying life with him.

Baptism is basically a summary of a child’s whole life. It’s a recognition that this child is going to die someday, yes, but we’re claiming that on the front end. Christ has already died the death we’re going to die, and we’ll be given the life he has won for himself. In between, our whole life is the story of how God’s grace and promise given in baptism gets worked out in our actual lived experience.

Discipleship is about us learning to take on an identity that’s given to us in our baptism. In Deuteronomy 26, Moses teaches the Israelites how to think about their identity after they take possession of the Promised Land as their inheritance. Whenever they offer the firstfruits of their harvest to the Lord, they must recite a little summary of the story of redemption to the priest: “And you shall make response before the Lord your God, ‘A wandering Aramean was my father. And he went down into Egypt and sojourned there, few in number, and there he became a nation, great, mighty, and populous. And the Egyptians treated us harshly and humiliated us and laid on us hard labor. Then we cried to the Lord’” (vv. 5–7). Now, did the Egyptians mistreat the particular individuals God is teaching to recite this story? No, the patriarchs had died many hundreds of years earlier. God is teaching his covenant people to take the identity of the patriarchs as their own. We were treated harshly and humiliated in slavery. We cried to the Lord, the God of our fathers, and he delivered us in great mercy and power. He did it for me. Because the God who kept his word back then is the same God who makes promises today, to me and to my children. A wandering Aramean is my father and theirs too.

Our whole life is the story of how God's grace and promise given in baptism gets worked out in our actual lived experience.

My kids were each baptized in different states (one in a different country), in different churches, different denominations. That’s part of the truth. But the deeper truth is that all of them were baptized into Jesus and all of us were baptized into each other.

23 MODERN REFORMATION Converse

God gives this promise to his covenant people, but we also adopt it and trust it as our own. One thing I love about our prayer book is that, at a child’s baptism, the parents take the baptismal vows on behalf of the child. We’re the guarantors of these vows. Later, in the confirmation process as a child matures, he or she is catechized and learns the faith. Then the child goes before the bishop as a representative of the church and personally takes on those vows. But they’re the same vows, which the parents are in a very real sense handing over to the child as their covenant identity.

I think all our confessional traditions would wholeheartedly embrace the good news that God’s promises are for our children, and so we call them to embrace the heritage that God is giving them.

That’s right. And because of his grace and faithfulness, we trust that God will woo the hearts of our children to fall in love with his gospel. Even through their sin, messiness, and trials, he’ll speak tenderly and whisper to them that he loves them and will call them to faith. Just as he does with us.

And that’s how we remember our baptism.

Brannon Ellis is executive editor of Modern Reformation.

24 July/August 2024

Because of his grace and faithfulness, we trust that God will woo the hearts of our children to fall in love with his gospel.

Two Robes (The Pain of an Answered Prayer)

by Andrew Menkis

“And his mother used to make for him a little robe and take it to him each year when she went up with her husband to offer the yearly sacrifice.” (1 Sam. 2:19)

Every year Hannah wove a little robe. A gift for the gift she gave back to God, a blanket of love, for the prayed for babe, warmth for the baby boy who she once nursed. What did she feel when she saw him again, embraced him, kissed him, tousled his dark hair? Did sadness for lost days fill her with pain? Anger at the cost of an answered prayer? Did he flash that shy smile children retain for a stranger, as they clutch mommy’s leg? Was Hannah ever tempted to complain? Why give, then take, the gifts for which we beg? Dare we doubt the God who gave up his child, for by his Son’s robe we are reconciled.

25 MODERN REFORMATION POEM

Soil Sorrows

by M. C. Fox

Dear Christian, does your heart with sorrow ache? Do woes and worries plague your plodding hours? And do your smiles fade like fragile flowers? Does every breath seem more than you can take? You beg of God your bones might once not break Yet still they shatter, crack before earth’s powers. You wonder why the sweetest milk still sours, Why, why the oven burns what bread you bake! Dear Christian, all these times that you have known, Some times with pleasure, more perhaps with pain Of bitter water not rich bowls of wine, Both wells and ills are where your roots have grown, Have flourished shoots that reach for heaven’s gain And bear upon their branches fruits divine.

You cast your eyes upon the soil black Beneath your feet where sinful soles have trod And only see what in your life you lack But not the fertile earth to grow in God. These times, both glad and hard, are gifts of grace: The days of drought to deeper dig and drink His Living Word, to seek His Holy place And in His promises your roots let sink. For though the sod is dark and clouds your eyes So that the Hope of Christ is hard to see This grave is not the end and you will rise With Him who is the Light who sets us free!

Dear Christian, though dark sorrows haunt your days, Look up to Christ, your light and joy, in praise!

26 July/August 2024 POEM

III.

Persuade

Thinking theologically about all things

29 MODERN REFORMATION Vol. 33, No. 4

HOW GOD MAKES

DISCIPLES THROUGH Word and Sacrament

by JOHN BOMBARO

30

LITURGY AS DISCIPLESHIP:

IN THIS ESSAY, I WANT to make the case that disciple-making belongs exclusively to the church, because disciples are made by God alone through the liturgy—the ministry of word and sacrament in gathered worship. Liturgy is discipleship; discipleship is liturgical.

By liturgy or liturgical, I’m not referring to a traditional style of worship. That’s looking at liturgy as a religious preference or human contrivance. In reality, liturgy works in the opposite direction—top down, from God to us. The liturgy is first God’s approach to us and only then our approach to God. Liturgy isn’t about a style of worship but a theology of worship, a theology of the Word in action and the Word made manifest. To think about worship theologically is to look at Christianity through the liturgy as the very context in which all the church’s knowledge of God is lived and experienced. It’s the way we objectively hear and experience Christ for us, Christ with us, Christ in us—all mediated by his leitourgia, his “public service” to us. The church’s approach to discipleship, therefore, is the expression and application of its theology of the liturgy.

In the liturgy of God’s self-giving through word and sacrament, we find an expression of God’s divine character as the one who is love and who freely gives himself and his love through tangible means of grace that restore loving union between God and humanity. This is our original design and ultimate destiny; God’s liturgical love affair reshapes and reawakens our desires toward what is truly lovely—the union and love shared between Father, Son, and Spirit, which overflow to humanity and bring us into that same divine love and life. This is the destiny of discipleship, and its domain is the church, gathered as the church. Disciples are made in and by the church as the liturgy both delivers God’s love to us and awakens the love of God within us.

Liturgy Is God’s Self-Giving through Word and Sacrament Exclusively within the Communion of Saints

The word leitourgia appears in the New Testament fourteen times, under various cognates, meaning a public office or service undertaken for the wider community. In the ancient world, liturgy was an act of public service done by a patron or private benefactor for the good of the community. It was a work of the greater for the good of the lesser. In the context of the story of redemption, liturgy refers to the service that God in Christ undertakes on our behalf and from which we benefit as the redeemed and worshiping communion of saints. When describing Christian worship in particular, leitourgia provides a beautiful picture of God as

Disciples are made in and by the church as the liturgy both delivers God’s love to us and awakens the love of God within us.

31 MODERN REFORMATION Persuade

***

“You

the benefactor who does his gracious work of pouring out his good gifts upon the assembled congregation.

These saving gifts from God are poured out freely and bountifully but exclusively within the worshiping community. Consider Christ’s commissioning of his apostles. In John 20:19–23, he ordains them by breathing his Spirit upon them and charging them with the authoritative administration of absolution: “If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven them; if you withhold forgiveness from any, it is withheld” (v. 23). Through the church’s ordained ministers, the gospel of God’s grace is announced, proclaimed, and enacted both corporately and individually as the forgiveness of sins is bestowed. In other words, the ministry is called for the purpose of administering a divine liturgy that saves and sanctifies God’s gathered people. Likewise, in Matthew 28:19–20, we find the Lord’s famous charge to “go therefore, and teach all nations, baptizing them into the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. And teach them to observe all that I have commanded you. And, lo, I am with you always, even unto the end of the world.”1 Notice the elements of discipleship: Jesus commissions teaching by the church’s ministers (evangelism) that results in sacramental action (baptism) and formation (catechesis), all within the context of the assembled church. What is this but another way of saying “liturgy”? Disciples are made through the liturgical activity of the church and its ministers in which Christ specially promises to be present and to graciously give himself to us.

Put negatively, we could say there is no normative, promise-laden domain for making and maturing disciples outside of the church or beyond its liturgical ministry. The church father Saint Cyprian of Carthage stated it definitively: extra ecclesiam nulla salus, meaning “outside of the church, no salvation.” In other words, Christ justifies, regenerates, and sanctifies the baptized, equipping us for our myriad vocations—all within the church. Nowhere else can we reliably find the disciple-making, disciple-forming liturgical activity of Christ.

Thirteen centuries later, Martin Luther reiterated the same conviction, identifying the location of the church as wherever Christ himself is performatively present to save and sanctify his people:

Therefore he who would find Christ must first find the Church. How should we know where Christ and his faith were, if we did not know where his believers are? And he who would know anything of Christ must not trust himself nor build a bridge to heaven by his own reason; but he must go to the Church, attend and ask her. Now the Church is not wood and stone, but the company of believing people; one must hold to them, and see how they believe, live and teach; they surely have Christ in their midst. For outside of the Christian church there is no truth, no Christ, no salvation.2

In his reflections on discipleship, Luther invokes the Augsburg Confession’s definition of the church as “the assembly of all believers among whom the Gospel is preached in its purity and the holy sacraments are administered accord -

32 July/August 2024

cannot have God for your Father if you have not the Church for your mother.”

—St. Cyprian

ing to the Gospel.” 3 Of course, the only one who can preach the gospel in all its purity is Christ himself; he alone renders the sacraments by his Spirit, who is at work in the church’s ministers to steward the mysteries of God by faithfully preaching, absolving, and administering the sacraments.4 To find Christ and his saving work, one must (as Luther put it) “first find the Church” in which Christ “liturgizes”—that is, gives himself to us and for us. This elucidates why Lutherans have historically employed the term Gottesdienst for Christian worship, meaning “God’s work” or the “Divine Service.” Again, worship’s primary movement is from God to humanity, with God as the main worker and humanity as those being worked on, made, and formed into disciples.

The church is a liturgical sheepfold. The sheep are led into the church’s liturgy by the Good Shepherd himself. We know his voice, and we follow him as he performs the wonders of Psalm 23, making us lie down in green pastures, leading us beside still waters, preparing a table in the presence of our enemies. Nowhere else but within the church does our Good Shepherd promise to provide for his sheep in these ways, which is why William Perkins and others classically identified the church as the sole theatrum salutis (“forum of salvation”).5 It is only here in Christ’s sheepfold that we truly know our Shepherd and are truly known by him: “I know my sheep and my sheep know me” (John 10:14). This mutual knowing is intimately and exclusively experienced through the church’s liturgical work of word and sacrament ministry.

We Were Made to Love in the Image of the God Who Is Love, and the Liturgy Is the Work by Which God Reshapes Our Love for Him and One Another after the Image of Christ

When we view discipleship in this way—as a deep and intimate knowing experienced through God’s loving liturgical actions for us and in us—then we’ll begin to recognize that discipleship is properly grounded in the nature of God as the one who is love. Discipleship isn’t an optional add-on to Christianity for committed Christians, for those who like theology, or for those who want to live virtuously. It’s not a class you take, an intellectual exercise, or emotional expression. Discipleship is Christ in action—in you and for you.

If discipleship is intimately being known by the God who is love, and knowing him and one another in turn, then love must be the highest and fullest sort of knowing that there is. This knowledge begins with the liturgy gifted to the church because through it we have a collective personal encounter with him who is love as he gives himself to us so that we can also love. “Just as I have loved you, you also are to love one another. By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:34–35).

It’s no wonder that God forms disciples in the church through a liturgical love

If discipleship is intimately being known by the God who is love, and knowing him and one another in turn, then love must be the highest and fullest sort of knowing that there is.

33 MODERN REFORMATION Persuade

***

affair in word and sacrament—human beings are creatures designed to love and adore. In James K. A. Smith’s idiom, man is homo liturgicus. 6 In the beginning, we were created to give ourselves to God from within creation in response to him giving himself to us. Like nonsentient creatures that declare the glory of the Lord (Ps. 19:1; 148), along with the angels (Rev. 4:8–9; 7:11–12), human beings were made for the express purpose of displaying (imaging) his glorious likeness. 7 God dwells in glory, an emanating glory we were designed to reflect (Isaiah 43:7). At heart, then, the image of God must be understood in relational terms. It starts with communion with God and extends to communal relations with others, ourselves, and even the cosmos. Human beings were created for this liturgical end: giving ourselves to God in worship and to one another in selfless service. This was our original dignity and freedom. The fall, however, marred that image, negated our freedom, broke our relationship with God and one another, and set us on a trajectory toward an altogether different end: judgment and condemnation. In this sense, sin is nothing less than liturgical failure.

The story of redemption is one of God building a liturgical bridge to us to restore our imago Dei calling as liturgists. Through that liturgy, God comes to us while drawing us to him in fear and love. “Because God is a Trinitarian community of love,” theologian David Fagerberg says, any “progress toward fuller humanity, fuller imagery of our prototype, means that we must grow in love’s

34 July/August 2024

The church is a liturgical sheepfold. The sheep are led into the church’s liturgy by the Good Shepherd himself. We know his voice, and we follow him as he performs the wonders of Psalm 23.

“Shepherd and Sheep” (c. 1880) by Anton Mauve

communion.”8 In other words, discipleship has a liturgical goal: to realign us with God, creation, our neighbor, and ourselves.

Yet there’s more. Justification and regeneration, even sanctification and glorification, are not ends in and of themselves. These are preparatory. These have an ultimate goal in the glorification of God and our restored communion within a resurrected cosmic order enjoying eternal worship. Since this is the goal, that means the primary task of the liturgy is to prepare disciples now to be glorified worshipers then. What we currently experience in part—as God brings heaven to earth in the liturgy—will become the fullness of eternal life, not merely an endless quantity of time but a divine quality of existence. Liturgy is the church’s discipleship program, preparing and practicing for eternity.

“Disciple” (mathetes) means “learner.” The content of our learning isn’t mere data but an engagement with the Word, who is ultimately a Person who makes God known in love. This Word comes to us incarnated and inscripturated and sacramented—that is, altogether in the church’s liturgy. This kind of love eludes definition, other than to say that “God is love” (1 John 4:8). But it doesn’t remain beyond our grasp because this Love is personally encountered in his work of word and sacrament ministry.

Only the liturgy—the means of divine self-giving and other-receiving— makes God’s love manifest and manifold. To know this kind of love is to share in the Christian life (1 John 4:7–12). While small group and youth group settings offer both an opportunity for and instantiation of this love for one another,9 and should be valued for this contribution as well as promoting study of the word, they are not the church or Christ’s domain to advance discipleship.

Secondary Realms of Christian Activity Can Supplement the Liturgy but Cannot Be the Primary Domain of Disciple Formation

Discipleship is something that happens within the church through its God-ordained means of grace. It is in the church as church that disciples are made—not through parachurch organizations, small groups, book clubs, podcasts, or magazines, as salutary as these supplemental means may be.10

To be sure, doctrine is a vital gift of truth, and good small group Bible studies will mine Scripture for these truths. But dogmas cannot be fully comprehended. Instead, they are apprehended, and even then, they are not an end to themselves. The same holds true concerning baptism, holy absolution, and preaching. As we behold the one we love, our dogmas are lifted up into their destiny in the very one who is the way, the truth, and the life, the one who is love.11 And this is where information-based youth groups, discipleship series, and the like come to the end of their usefulness. They are domains of secondary speech—speech about God derived from but not authoritative as God’s own speaking and acting. Doctrines as data points, be they never so truthful, are guides to God and the knowing of

35 MODERN REFORMATION Persuade

***

The primary task of the liturgy is to prepare disciples now to be glorified worshipers then.

Discipleship inextricably belongs to the institutional, brick-and-mortar complexion of the church where pulpits, fonts, and altars monumentalize the God who is present and active on our behalf.

God as experienced in the love affair manifest in the liturgy. During the liturgy, doctrinal information gives way to simple words and primary speech: “Take, eat,” “Take, drink,” “Given for you,” and “Peace be with you.” Within the liturgy of love, the proposition of forgiveness “You are forgiven” overflows into living worship: “I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom. 8:38–39). Being brought into the divine life and love through the means of grace awakens within us true love for that which is most lovely: God himself. This love is the only way all our other loves and desires begin to be properly ordered and set right.

The upshot is that if communities of believers desire the salvation of souls and sanctification of their members—which is to say, true discipleship—then let the assembly of believers gather to Christ’s duly called and ordained ambassadors for the liturgy! This is where God delivers the goods. And this is why, traditionally, neither the world of unbelievers nor the people of God have called youth group, VBS, church camp, or small groups “church,” as edifying as these groups may be. The same can be said about Christian publications, podcasts, or programing, albeit without denying their serviceability to the church. While these activities may pragmatically or socially augment the commissioned first-order responsibilities of the church, they are not the designated domain of Jesus’ ongoing kingdom proclamation and kingdom miracles; the church is.

Take as an example the kingdom miracle of baptism. Baptism is not mere secondary speech or object lesson; it is not left up to me or my small group leader to evaluate or perform. Any hint of elitism, works-righteousness, or Gnosticism is done away with in the baptismal waters. Unlike Hill Cumorah (where Joseph Smith claimed to meet with the angel Moroni), in the cave called Hira (where Muhammad claimed to receive his first revelation from the angel Gabriel), or under the Bodhi Tree (where the Buddha claimed to reach enlightenment), the waters of baptism are a public mystery, a historic act given to the apostles and entrusted to ministers throughout the church in which God openly seals all who receive it as belonging to the risen Christ.

The same could be said with respect to preaching—not only the act but the content: “These things were not done in a corner” (Acts 26:26). From the moment anything was recorded by the early church, we see evidence of the ordained ministry administering a public liturgy to save and sanctify. The liturgy thus dampens our natural propensities toward a cult of personality (such that regularly occurs in nonliturgical settings) and instead posits the performed word and sacraments as the church’s cult —from the Latin for “worship”— engendering its culture.

This is so important for the way God fashions and refashions sinners into saints that certain dynamics of the disciple-making responsibility of the church cannot and will not be found outside of the church’s God-given ministry. Theologically speaking, there is no “virtual church”; online attendance

36 July/August 2024

is another kind of absence. Contemporary efforts to diffuse discipleship from sanctuary-based, minister-dependent word and sacrament ministry to socially dynamic peripheral or parachurch endeavors overestimate the tangential benefits of small group ministries and the like, be they never so professionalized or credentialed. Removed from the auspices of the ordained clergy of the church, the professionalization and personalization of discipleship is often more indicative of the American spirit than the Holy Spirit. Discipleship inextricably belongs to the institutional, brick-and-mortar complexion of the church where pulpits, fonts, and altars monumentalize the God who is present and active on our behalf.

The Liturgy Is Where Disciples of God Are Formed and Empowered by God’s Own Speaking and Acting within the Community through Its Ministers

The assembled church, gathered around Christ’s word and gifts, is the place where we aren’t just speaking about God. It’s the place where God is speaking and doing through authorized ministers. Indeed, as soon as there was Christ-commissioned preaching from Christ-commissioned apostles on the Day of Pentecost, we see that the baptized “devoted themselves to the apostles’ teaching and to the communion in the breaking of the bread and to the prayers” (2:42).12 Believers were baptized, catechized, and attended to the eucharistic liturgy. 13 These means of grace fueled the missional enterprise of a church strengthened by the risen Christ present and active in its midst. There was no such thing as a “self-feeder” or a “church of one”; if a disciple departed from the liturgy like in 1 Corinthians, Christ’s ambassador (Paul in that case) called it back to liturgical devotion amid the assembly of believers (cf. 1 Cor. 11:23–26; Heb. 10:25).

At least three key factors differentiate the church from every extraecclesial group: (1) the unique ministerial presence of God-ordained clergy; (2) the God-given liturgy they administer; and (3) the divine purpose for the disciple, which is not coaching or mentoring but gracious salvation and sanctification that leads to transformation through the means of grace (2 Cor. 5:16–21). In this light, few organizations or activities fall within the scope of holy ministry, despite a cornucopia of well-marketed, self-designated ministries.

Any institution or activity that seeks to come alongside the work of the church must, by divine arrangement, urge and support participation in the liturgy that Christ committed to the church’s ministry. Whatever saving or sanctifying prospects small groups and such may proffer, they must necessarily be oriented toward ordained word and sacrament ministry among the gathered saints in order to be truly effective. Evangelistic endeavors, for example, that result in a decision for Jesus or commitment to Christ from a nonbeliever can never stand on their own; they’re tenuous and subjective if they remain outside the church. Holy baptism, on the other hand, makes objective before the assem-

Any institution or activity that seeks to come alongside the work of the church must, by divine arrangement, urge and support participation in the liturgy that Christ committed to the church’s ministry.

37 MODERN REFORMATION Persuade

***

Though disciples are indeed learners, our ultimate goal isn’t gaining information about God. Our path leads toward intimate union with God.

bled church the gracious posture of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit toward the newly redeemed individual.

It’s not that personal experiences of conversion and faith before coming into the Christian community are inherently invalid; it’s that the liturgical rite administered by Christ’s ambassador (save for emergency circumstances) publicly and officially confers new covenant rights, privileges, discipline, and protection to the baptized. They are justified. They are Christian. They belong. So says Christ to his church, through his church. This is why Luther considered all baptisms to be infant baptisms: only the word of Christ changes the status and standing of sinners, not the sinner’s decision or action. As for “emergency circumstances,” they are the exception. Scriptural authority must be our rule.

Not Mere Knowledge about God, but Intimate Communion with God Is Every Disciple’s Ultimate Goal

Though disciples are indeed learners, our ultimate goal isn’t gaining information about God. Our path leads toward intimate union with God as we are made partakers of the divine nature and conformed to the image of his Son (2 Pet. 1:4; Rom. 8:29). In his threefold office as prophet, priest, and king, Jesus’ liturgical service translates us into the church through word and sacrament (Acts 2:22–42), which in turn transforms us through sanctification and vocation into liturgists—those who serve for the sake of others. To be a Christian, then, is to be a liturgist. There is an ultimate end for which we were made: to glorify and enjoy God. That’s the point of the liturgy—why indeed it is an end in and of itself. To be a liturgist is to be restored through word and sacrament to participation in humanity’s original and final purpose: worship.

Finally, since only Christ’s self-giving engenders conformity to his likeness, embracing liturgy as discipleship also provides a decisive argument for weekly Holy Communion as the regular discipline of the disciple. We must beware lest services that omit the sacrament of the altar become glorified Bible studies. During Holy Communion, the bridegroom becomes one with his bride and weary disciples on this pilgrim journey—if only for a moment—touch and taste the realities of heaven.14 ***

Conclusion

Christ’s liturgical work of word and sacrament in the church is discipleship rightly understood. It is here in the church and through its ministers that Christ’s love is made manifest for us and in us. And it is here that disciples are properly formed in intimate love and knowing—participating in the very life and love of the Trinity.

38 July/August 2024

***

The liturgy cannot be outsourced. It is the exclusive responsibility of the church, of its ministers, to wield it for the purpose of making and forming disciples. There is no God-given liturgy that can be presided over by anyone but a duly called and ordained celebrant.

Whether established from Jesus’ charge to his disciples in John 20:19–23 or the Great Commission of Matthew 28:18–20, disciple-making and formation belong to the church. Jesus made these treasures its possession, with no option to parcel them off to extraneous organizations, be they ever so cost-effective or fun. What would “outsourcing” the liturgy mean other than unchurching the church? This is because the Lord Jesus bequeathed to the one, holy, catholic, and apostolic church the stewardship of the word of God and the sacraments. In this way, Jesus committed to the church his speaking, his Spirit, his presence, his self-giving, and his rule—in sum, his leitourgia—for the express purpose of saving and sanctifying humanity. Christ serves us so that human beings may once again “glorify God and enjoy him forever,” as well as serve their neighbor made in the likeness of God. Christ’s liturgical legacy constitutes the essential life of the individual disciple and, collectively, the raison d’être of the church itself.

It is possession of the divine leitourgia that makes the church the kingdom of God. The boundaries and duties of the church, then, are the Divine Service in and through which the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit forge and fashion saints. This is God’s arrangement. We could not make it so. Only the Lord brings the liturgy into being.

Rev. John J. Bombaro (PhD, King’s College London) is senior pastor of St. James Lutheran Church, Lafayette, Indiana, and special projects supervisor at the US Naval Chaplaincy School, Newport, Rhode Island.

Christ’s liturgical work of word and sacrament in the church is discipleship rightly understood.

1. For the rationale for this translation, see Wolfgang Reinbold, “‘Go Into All the World and Make Disciples?’: On the Translation and Interpretation of Matthew 20:19–20,” Logia XXX:1 (Epiphany 2021): 31–43.

2. Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Sermons II (St. Louis: Concordia, 1974), 52:39–40. Likewise, John Calvin, Institutes of the Christian Religion, Book IV, I, i and iv.

3. Augsburg Confession, VII.1.

4. Martin Luther, Luther’s Works, Word and Sacrament IV (St. Louis: Concordia, 1974), 38:28.

5. William Perkins, “Sermon in the Mount,” The Workes of that Famovs and Worthy Minister of Christ in the Universitie of Cambridge, M. William Perkins . . . , 3 vols. (London, 1612, 1613, 1631), 3:189.

6. James K. A. Smith, Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2009), 40.

7. This, of course, leads to the biblical understanding of vocation.

8. David Fagerberg, Liturgical Dogmatics: How Catholic Beliefs Flow from Liturgical Prayer (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2021), 83.

9. Cf. John 13:34–35; 15:12–17; Rom. 12:10; 13:8; 1 Thess. 3:12; 4:9; Heb. 10:24; and 1 Pet. 1:22; 4:8.

10. Though, of course, the question of churchly authority, doctrinal oversight, and church discipline are real questions to be reckoned with when it comes to these other venues of Christian edification.

11. John Romanides, Patristic Theology (N.p.: Uncut Mountain Press: 2008), 252.

12. My translation.

13. Note that for Luke, who was Paul’s companion, κοινωνίᾳ is the breaking of the bread. Cf. Luke 24:31–32 and 1 Cor. 10:16.

14. See Arthur A. Just, Heaven on Earth: The Gifts of Christ in the Divine Service (St. Louis: Concordia, 2013).

39 MODERN REFORMATION Persuade

Poiema

by Michael R. Ritt

I am a very special poem, My maker said it’s true. Each word was chosen carefully, Each rhyme and meter too.

With loving hands and careful thought, With heaven’s ink and quill, Each stanza written of my life, Was ordered by his will.

I’m not a poem that all can read, Or even understand. But every line of every verse, Was crafted by his hand.

And when the enemy tries hard To tell me it’s not true, I just remember I’m God’s poem, And my friend so are you.

(Soli Deo Gloria)

40 July/August 2024 POEM

41 MODERN REFORMATION Persuade

IV.

Engage

Connecting with our time and place

43 MODERN REFORMATION Vol. 33, No. 4

FROM DRAGONS TO DISCIPLES: WHAT

LEWIS AND TOLKIEN

TEACH US ABOUT

Making Disciples

by ANDREW MENKIS

44

CCHRIST’S COMMAND to his apostles to go and make disciples (Matt. 28:16–20) is intended for all his followers. Every Christian must think carefully about what it means to be a disciple of Jesus and to make a disciple of Jesus. Though the commission remains unchanged since Christ first uttered it, each new generation encounters contexts and challenges for discipleship that are both old and new. This reality becomes clear if we look at the youth in our society and begin to ask how we might best form them into disciples of Christ. There has been an alarming, well-documented rise in loneliness, depression, anxiety, mental health disorders, and suicides among children and adolescents over the last two decades—not to mention “the great dechurching.”1 For me, as a high school teacher and a parent of young children, these trends are particularly terrifying. How do we make disciples of children who might be struggling with debilitating depression or doubts? How do we make disciples in a context where these increasingly common struggles press on us as parents and teachers alongside all the typical struggles of being sinful human beings making disciples in a fallen world?

Consumer or Contributor?

Recently, I was struck by an interesting observation from counselor and therapist Keith McCurdy. In over three decades of working as a therapist, he has found that a person’s mental health generally correlates to where they fall on a sliding scale from “consumer” to “contributor.”2 The farther down the consumer side, the less healthy they tend to be. I wondered, could McCurdy’s observation shed light on how we as Christians think about making disciples—especially of our children? Since we believe we’re creatures made in the image of a creating God, McCurdy’s observation should come as no surprise. But we often forget a fundamental fact about being human: We were created to create. We exist to “glorify God and enjoy him forever,” as the Westminster Shorter Catechism famously puts it; a key part of our calling to bring glory to God is to bless our neighbors, to contribute in productive, valuable, meaningful ways to our communities. Adam was commanded to fill and subdue the earth. He was to be fruitful and multiply, creating a community that would exercise dominion over creation. However, Adam chose a shortcut to knowledge. Instead of learning through experience over a period of time, he sought to gain the knowledge of good and evil through a single bite. He would not earn or create knowledge. He would, literally, consume it. In fact, the Latin root for our word consume, consumere, means “to eat.” God had blessed Adam with all he needed for life, but he chose to reject God’s

We often forget a fundamental fact about being human: We were created to create.

45 MODERN REFORMATION Engage

***

For us who live east of Eden, we’re tempted to believe that we exist primarily to consume rather than contribute something good to the world. In believing this lie, we too have become less human than we ought to be.

provision and consume the fruit. By this choice, Adam condemned and corrupted himself and his posterity. Evil entered the world. The image of God was broken and polluted by sin.