6 minute read

Classic Movies: Jaws by TE Hodden

Classic Movie: Jaws

Advertisement

by T.E. Hodden

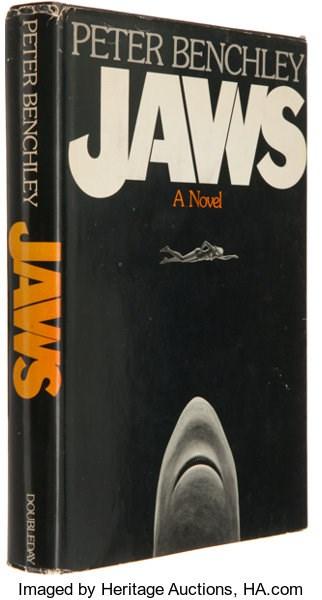

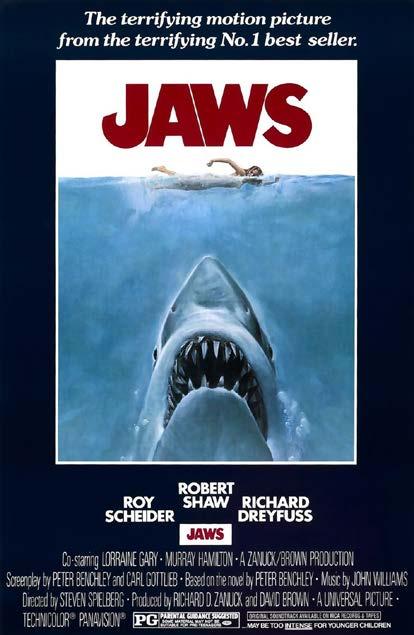

Between 1975, and 1977 everything changed about the way cinema worked. The idea of a rolling program, where one ticket let you step in and out of the rolling program of movies, shorts, B-features and cartoons faded out. The idea of buying a ticket for the one movie, and being expected to leave after, was a shocking new idea, but it was the only way to cope with the incredible demand on two of the films. A new term was coined, in 1977 to describe Star Wars: a blockbuster, so called because the queues to see the movie stretched around city blocks. Which is all to say, that in the summer of 1975, when Jaws hit the big screen for the first time, and started the sea-change in modern cinema, there was literally no word to describe its success. It hit the screens with a seven million dollar opening weekend, recouping its entire production cost in ten days, sailing swiftly past the Godfather’s previous record of eighty six million at the box office, to become the first hundredmillion-dollar movie. When it was re-released in ’76 and ’79, it still drew in tens of millions. Box office success alone, however, does not make a classic, so what is it that has secured Jaws’ enduring appeal, that marks it as a true classic? It all began, of course, with Peter Benchley’s book.

Hollywood legend has it that producers Richard D Zanuck, and David Brown found the book through Cosmopolitan magazine, where Brown’s wife worked. The magazine’s book editor had concluded the book might make a good movie.

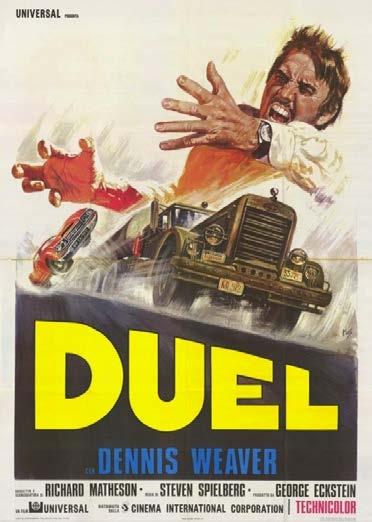

After a first read, the producers snapped up the rights, and started scouting for talent. Now, I don’t have a good source to cite for this bit, so you will have to excuse me for telling the legend, rather than sticking to the facts: When the director assigned to develop the movie kept calling Jaws a whale, the pair severed their ties, and turned instead to a talented young man called Steven Spielberg. Spielberg was best known as a TV director, with some very well regarded TV episodes, and made-for-TV movies to his name. He had the theatrical release, Sugarland Express, under his belt, but was better known for his TV movie Duel. In Duel, a businessman on his way home overtakes a lumbering old oil tanker, that harries and pesters the businessman, gradually raising the stakes to a deadly game of cat and mouse, trying to run him off the road. The film is directed in such a way that it quickly becomes easy to forget there is a human behind the wheel, and to see the truck as a monster, a lumbering, giant, force of nature, playing by the rules of hunter and prey, driven by instinct over intelligence.

It is easy to see why the producers were so sure that Spielberg was going to have a great eye for the key scenes of the novel. You can also see why Spielberg quickly grew nervous about the production, worrying he might be typecast as the monster-movie guy. Nevertheless, Universal convinced him to stick with the project, so Spielberg approached Benchley to write the first few drafts of the script, before, passing the script through several other hands, to Carl Gottlieb (who also appears in the movie as Meadows), for a rewrite. The screenplay prunes away much of the novel’s background and subplots, streamlining the narrative towards the second half, the shark hunt aboard the Orca, but also giving the three leads, Brody (Roy Schneider), Hooper (Richard Dreyfus) and Quint (Robert Shaw), a far more likeable chemistry. Elements that worked well enough on the page (Hooper’s affair with Brody’s wife, or the Mayor’s mob connections) weren’t going to translate well on the screen. In their place some neat little touches were added to hint at the depths behind the character (for example Brody’s discomfort with the ocean and boats, neatly suggesting his previously citybound career). The resulting screenplay is a masterclass of efficient, character driven storytelling. Film critic Mark Kermode said it best, when he pointed out that it doesn’t really matter if Spielberg thought he was making a movie about a shark, because

it ended up being about the town, and the people. The artful character studies highlight flaws and truths we have seen in ourselves, and our society, in dark times, over and over again, and will again. Subsequent generations will watch the film, and even if it isn’t really about climate change, corporate greed, or pandemics, people will see something familiar in the actions of the blinkered mayor insisting on opening the beaches, or the opinions voiced in the townhall meeting, or Brody’s regret for not pushing back harder, because these are truths they will see reflected time and again in the headlines. If you know one fact about the production of the movie, it is probably that Bruce, the animatronic shark, appears so little, replaced by eery and terrifying point of view shots, because Bruce was built and tested in fresh water, and malfunctioned terribly in salt water. The sense of the shark being there, as an unseen presence, much of the time certainly works in the film’s favour, and no doubt forced Verna Fields’ hand when it came to the creative editing, and cutting, that gives the movie so much of its flavour, but we should also acknowledge that so much of the film’s horror comes from the focus on the people. We see the human cost, to those around the victims, and we see the absolute terror of Brody and his family after a close call, when a tragic victim could so very easily have been their own. This is the X factor, that diminishes quickly in the sequels, and that so many imitators failed to capture. Going bigger, better, and more special effects can never make us care for the characters the same way we do as we watch the three leads getting drunk, or the world shattering around the Mayor, as the consequences of his choices hit home.

And of course, lurking under it all is John William’s iconic score. But, if I was going to boil the essential argument for why Jaws was a classic, it is this: I have been waffling on for a thousand words. I have not summarised the plot, or unplucked the beats of the story, but you have kept up, because even if you haven’t seen the movie, you still know what I was talking about, and if you have seen the movie, there is a better chance than not, that right now you are remembering how good it is. Jaws rewrote the style book for movies, in a lot of ways. Yes, Spielberg drew on Hitchcock, but he set the template that every blockbuster since has tried to emulate. Verna Fields’ editing, and Bill Butler’s cinematography essentially set the bar for what the Summer’s big movie looked like. It kick started the evolution of every action movie, of the horror genre, and the idea of an event movie. But… and I’m sorry to repeat myself here, the very human core means that Jaws will be remembered long after many of the imitators have been and gone.

T.E. Hodden trained in engineering and works in a specialized role in the transport industry. He is a life long fan of comic books, science fiction, myths, legends, and his-

tory. In the past he has contributed to podcasts, blogs, and anthologies. Discover more on Mom’s Favorite Reads website: https://moms-favorite-reads.com/moms-authors/t-e-hodden/