Antonius-Tín Bui

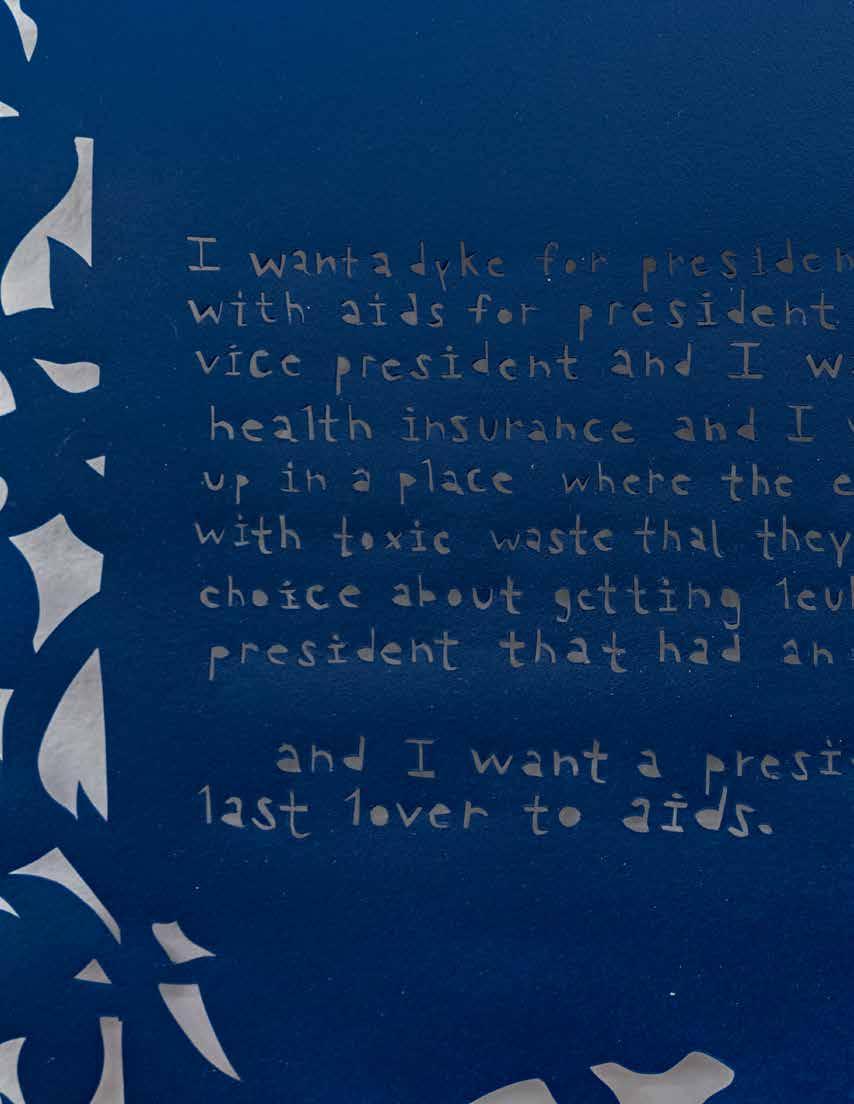

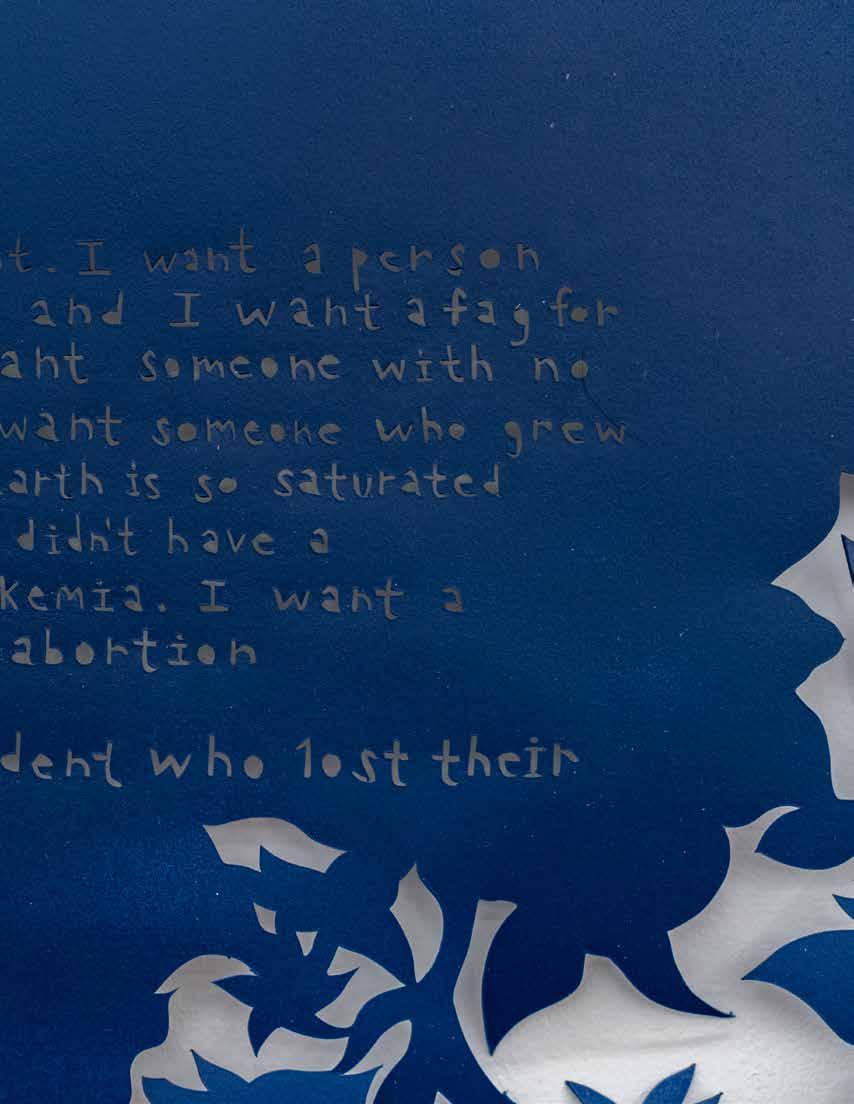

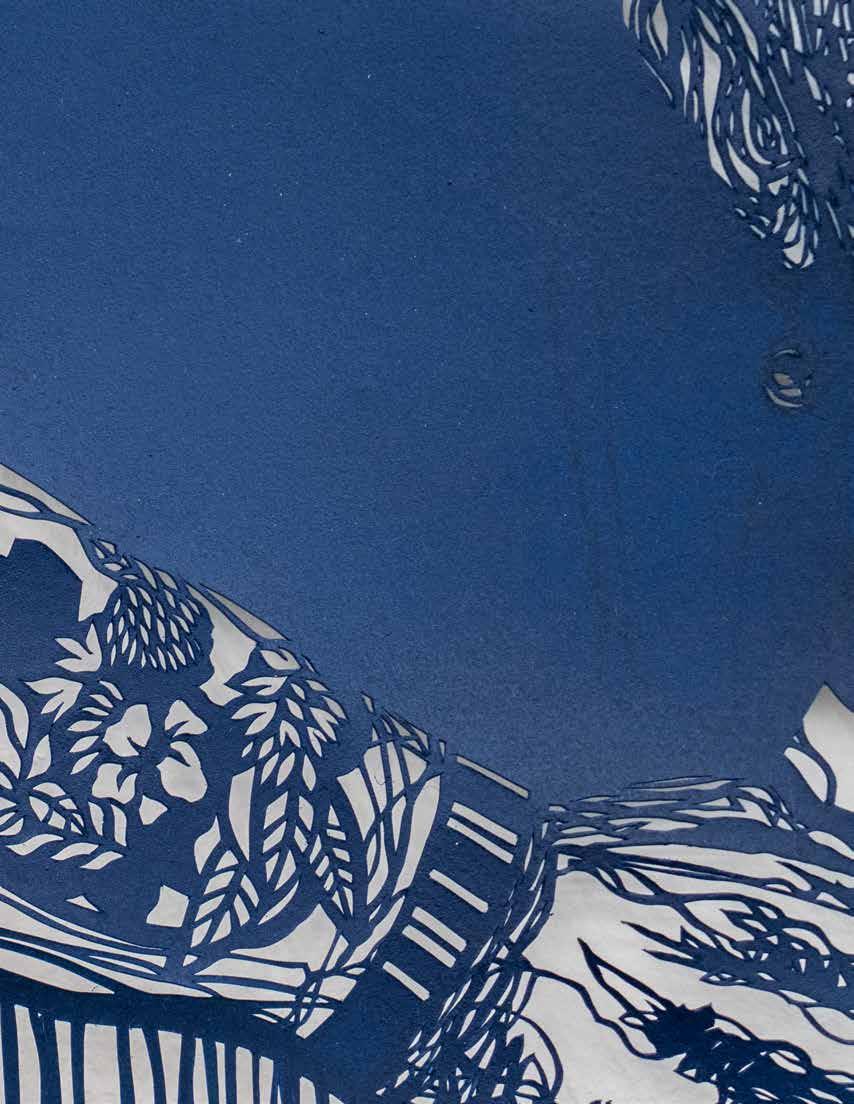

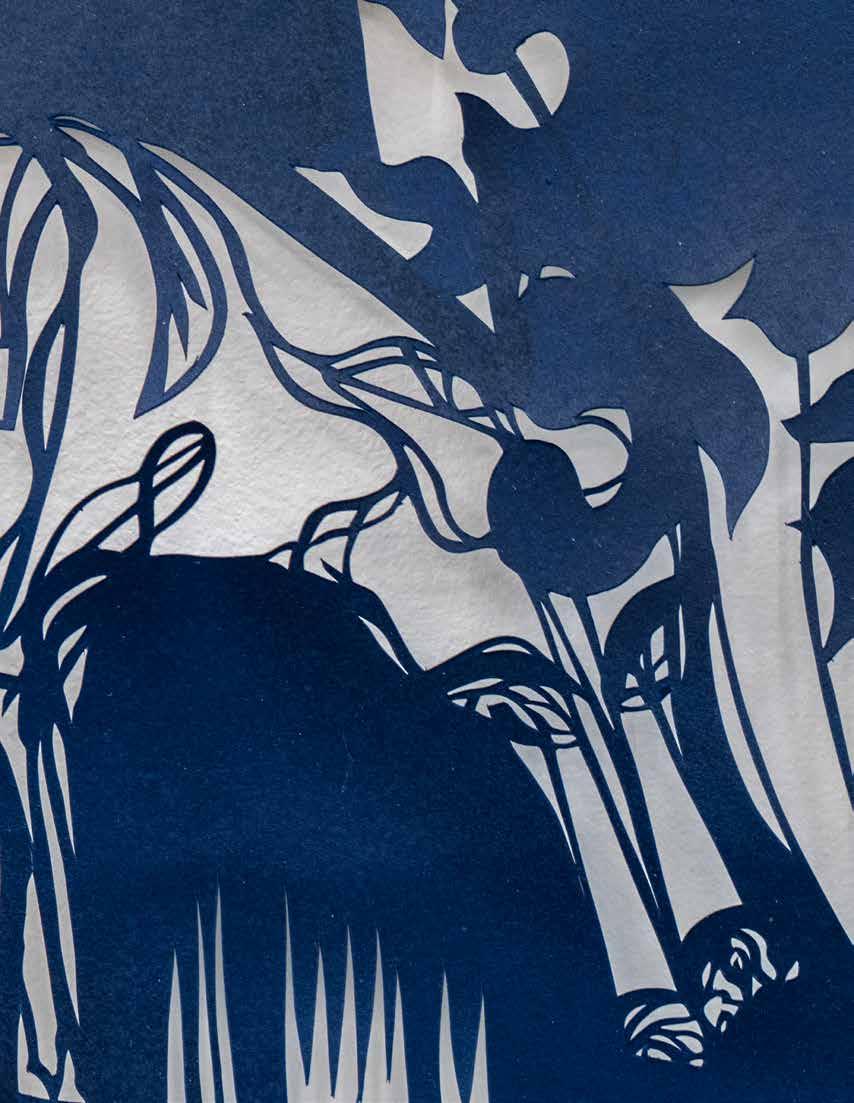

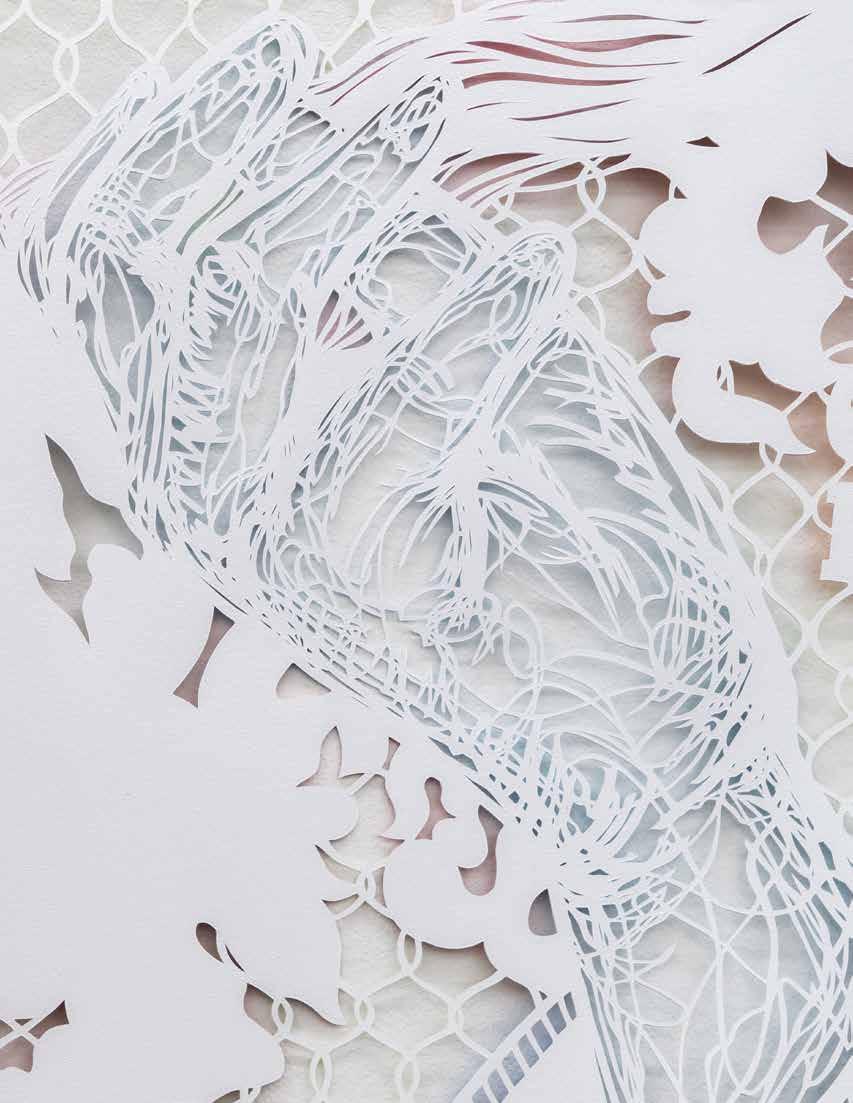

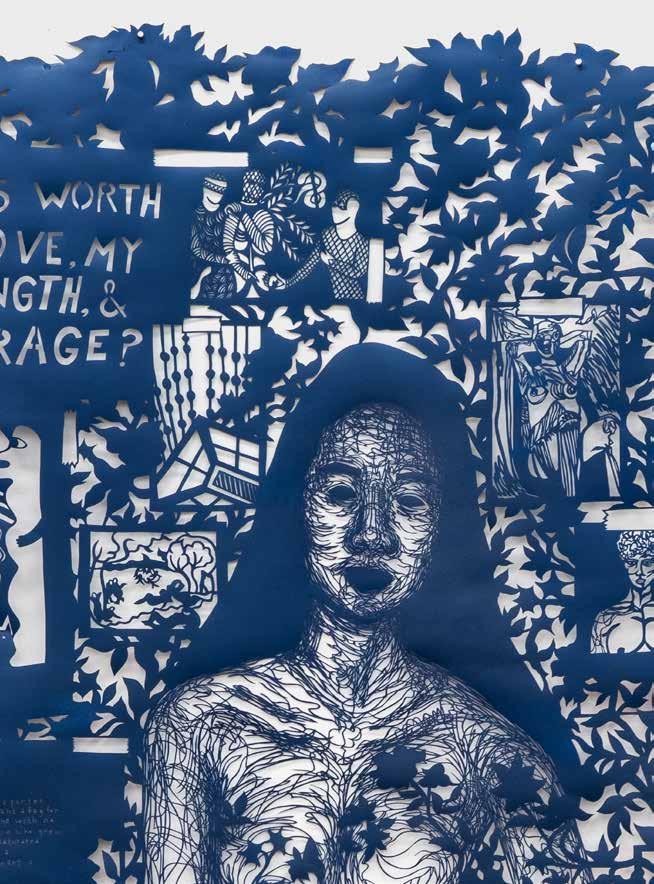

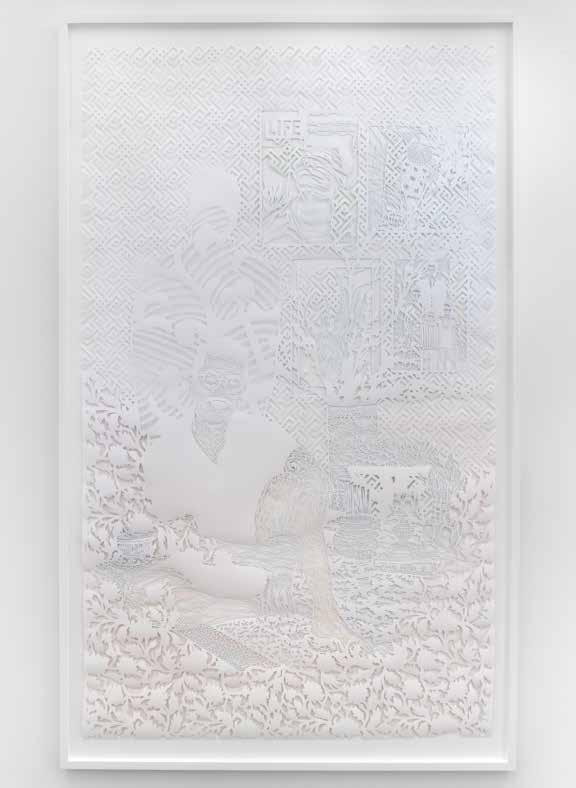

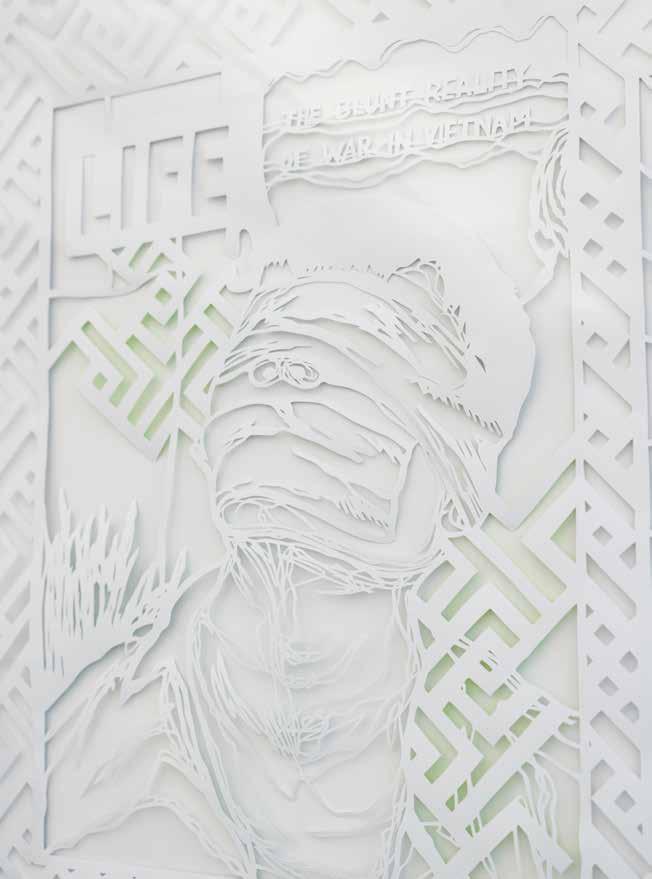

Front and back cover: I remember opening you into words, gently, with a single question, 2021(detail)

June 26 - August 14, 2021

Introduction by Ashley Wynn

Interview between Antonius Bui and David Antonio Cruz

Designed by Megan Foy

Edited by Staci Boris

Photographed by Robert Chase Heishman

This catalogue was published on the occasion of Antonius-Tín Bui’s first solo exhibition at Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

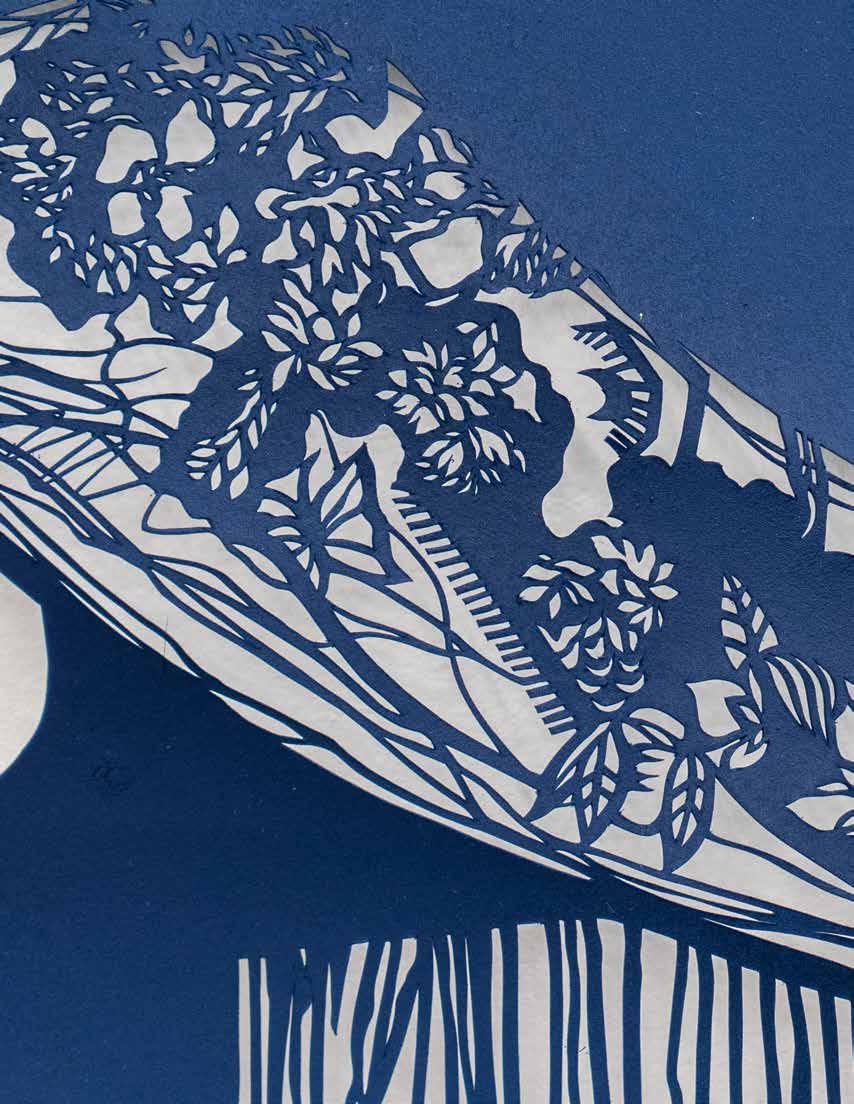

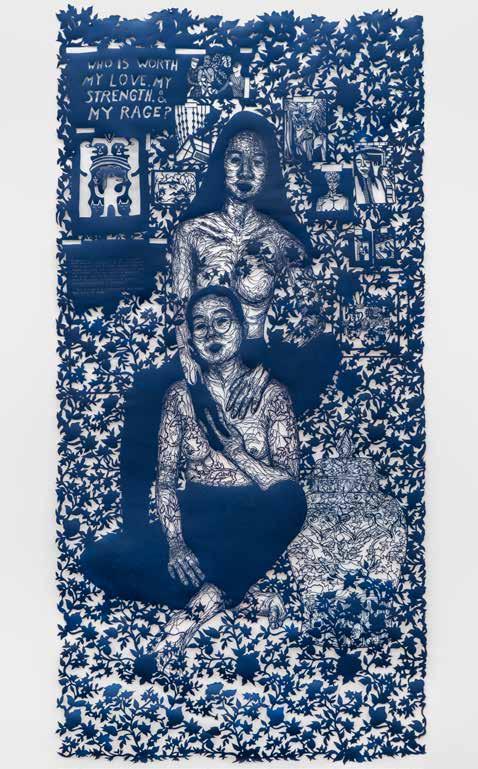

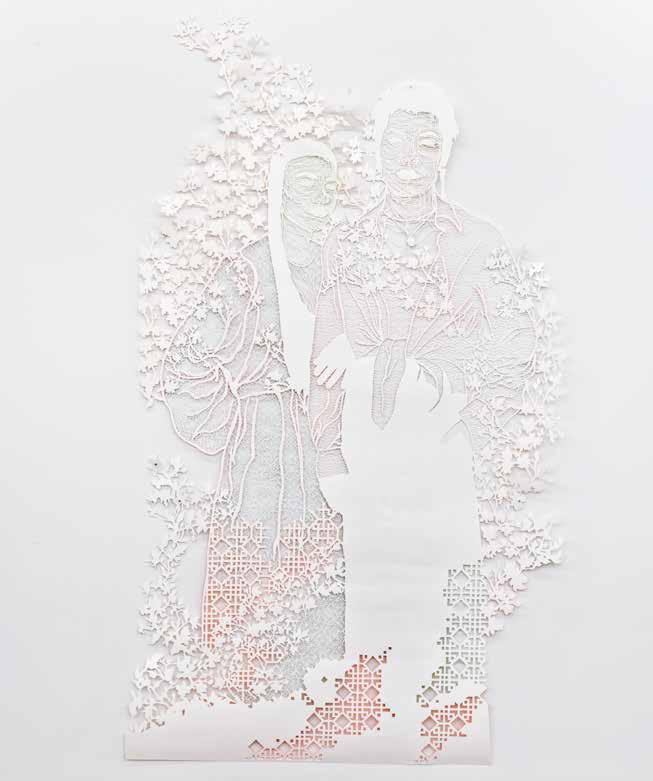

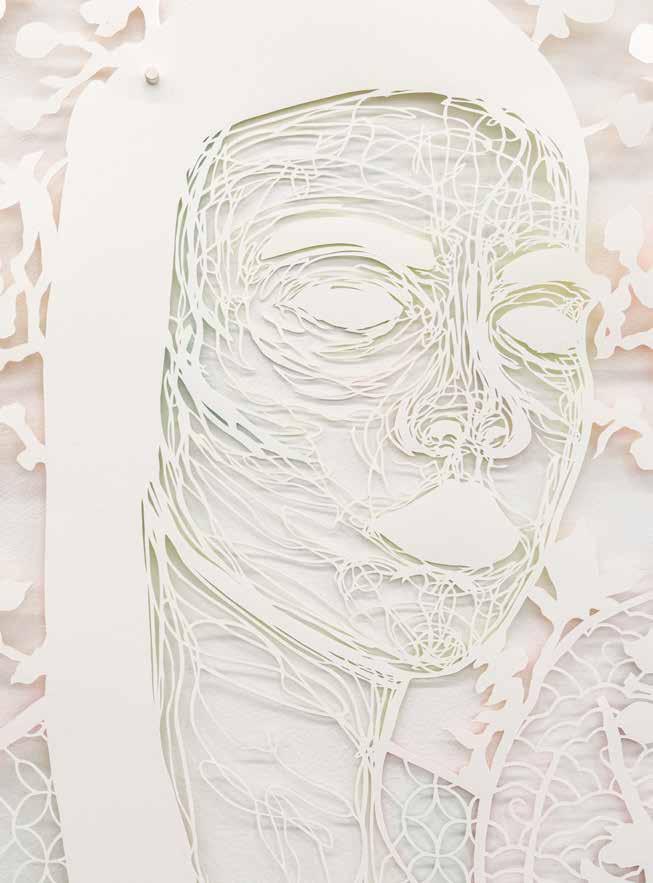

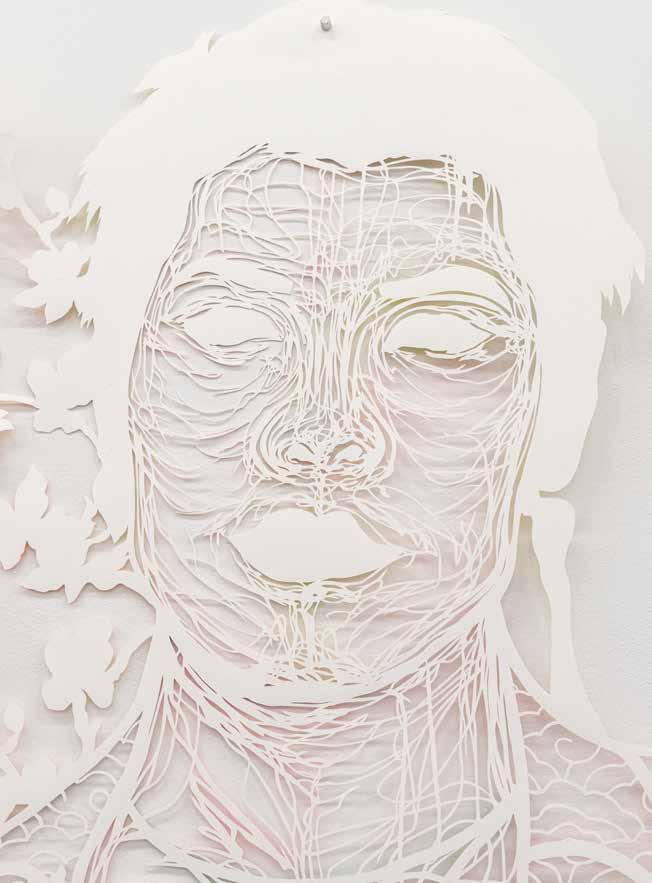

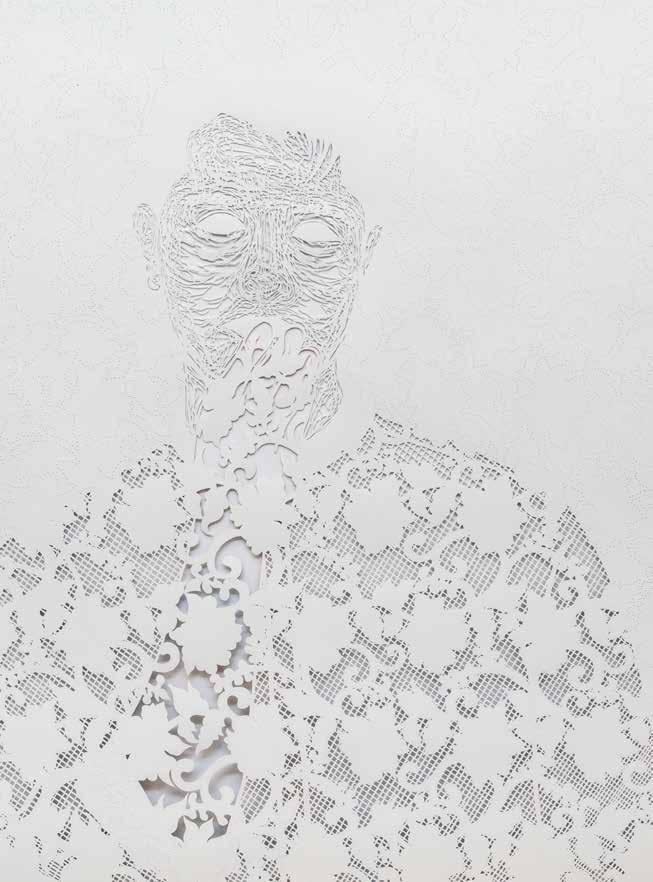

moniquemeloche is pleased to announce the gallery’s debut solo exhibition with Antonius-Tín Bui – The Detour is To Be Where We Are. Bui will present a new series of intensively hand-cut paper portraits, a visualization of hybrid identities and histories, told through an intersectional queer AAPI lens.

Each portrait presents an intimate reflection on the kinship shared within the queer AAPI community, found through moments of radical mundaneness. Rather than concentrate on notions of assimilation within a oppressive Western rubric, The Detour is To Be Where We Are explores a renewed sense of identification no longer concerned with adapting to constrictive binaries. Their subjects include friends, colleagues, family (both chosen and biological), all captured in moments of love and embrace, unapologetic displays of community that have been previously absent from mainstream stereotypical depictions of Asian dynamics.

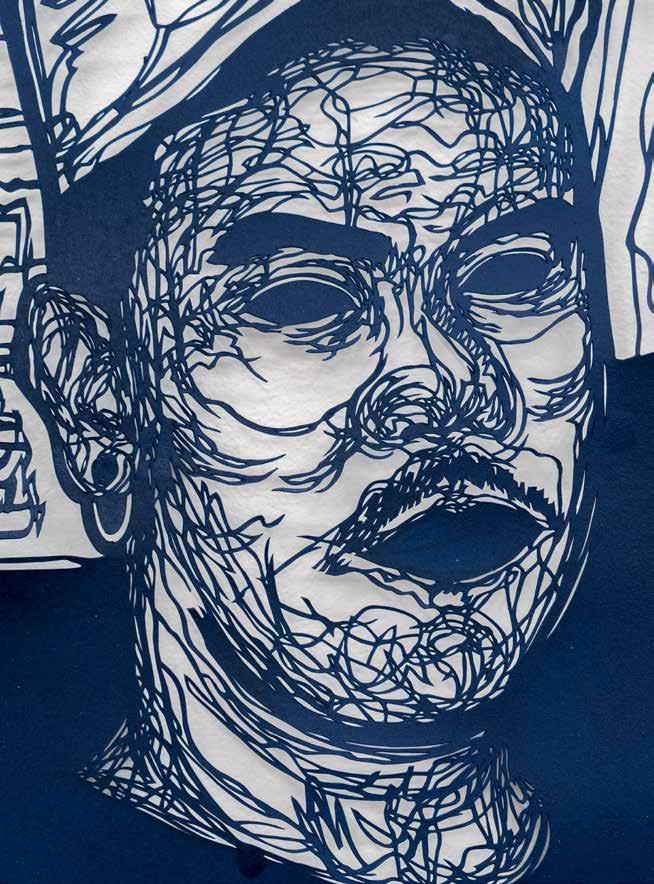

Their rigorous paper-cutting process is exceptionally meditative; each sheet of paper is carefully and intuitively crafted to embody an archive of memories and oral histories. The reductive process deconstructs the traditional white canvas in order to both metaphorically and physically carve out space for narratives which are so often omitted from whitewashed histories. While the stratified linework evokes a porous and flexible form, weaving through lines throughout the figures themselves as well as the organic environments in which they’re grounded. The use of paper considers both the archival documentation used to reconcile formerly lost AAPI narratives, while also drawing from the importance across Vietnamese culture. Allusions to the spiritual significance of Joss paper, an incense paper used both to imitate value and as a form of blessings, position each work almost as an offering to honor queer communities, Bui’s subjects in particular.

In contrast, the importance of archival photographs as essential tools for reconstruction of misrepresented and forgotten refugee histories, likens Bui to one of many intergenerational architects, reclaiming authority over how their story is told.

Bui utilizes the transformational properties of their medium to excavate a narrative that no longer places trauma and displacement at the forefront. Rather, each delicately woven work inhabits the body in a way that honors a reinvigorated sense of identification while echoing a fluid notion of interdependence and community.

Antonius Bui was the first artist whose studio I visited when things slowly started opening up. Although we had done talks together, chatted on the phone, and showed our work in the same exhibition (The National Portrait Gallery’s triennial Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition, 2019), this was the first time we had seen each other in person. Antonius was one of the first people I hugged after a year of social distancing and remote contact.

Antonius’s work has beautiful fragility and resilience; each cut carves out a history, a place, and a story exposing a network of support ligaments, stretching across the paper, mapping out intimate living spaces, patterns, words, Asian motifs, and vases that frame the subjects.

Our conversation left me with a range of personal memories, reflections on rituals, and shared resonances.

I was reminded of how I learned at an early age the need to hide or disguise my pitch and gestures, needs, and truth. Like Antonius, who is the child of Vietnamese immigrants, I am a child of parents that migrated from the island of Puerto Rico. They built mental walls to keep the American identity, customs, rituals, and culture outside of our doors. Love was expressed through weekly visits to my grandparents and large dinner spreads, but desire was never allowed to enter the front door.Occasionally, I pranced around with a towel on my head, swinging my head around—we had a good laugh, but we weren’t allowed to name the thing that we knew lived within me.

But I dreamed up a world where everyone was cute, warm, loving, safe. I spent my early years drawing that world—mapping it out, coding it on paper. There was always paper lying around. It could be folded and set to the wind, you could make cranes, share notes, tell stories, document history. You could crumble, erase, and start again. So fragile yet resilient. Every interlocking fiber maintained the shape, form, and burden of the stories written on it.

How do we remember, honor, celebrate life, our relationships, connections, our loved ones? We burn candles, sage, scribble their names on paper, cook their favorite foods. We play their songs, carry charms with their pic-tures, tattoo their faces and names on our arms, name our children after our ancestors, and present flowers, fruits, and incense for them. We dress them in the finest clothes.

We burn Joss papers, a ritual offering of money and wealth to the dead, which is most popular during death anniversaries, Tet, and the ghost month festival. We tell stories, write stories, draw on paper, and shape images on folded paper. We burn the names, papers, stories, drawings, sending them to the air, transcending this space, and collapsing memories, the possibilities of the future and possibilities of an unlived life.

How do we carve a space, make room for us, and still have space for the nuances? We bring the fire, darling—bring the fire.

DAC: How does your approach to the work begin? Do you sketch everything out before you begin cutting? Are you following specific motifs or is the process somewhat intuitive?

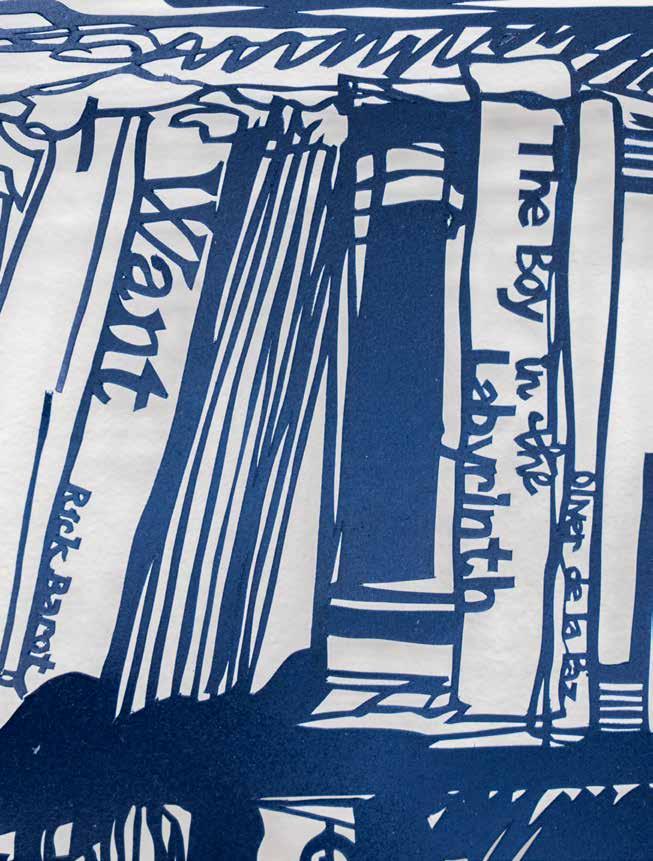

AB: I start by sketching out the body, contour drawing, responding with the backgrounds, and adding ele-ments, vessels, picture frames, or other external elements. Often, I already know certain elements I want to include; one is always reacting to one another. Sometimes I project an image of a vessel, sometimes I use preexisting cut pieces, and I trace them on. Then the patterns will overlay certain bodies, and as I cut them, I decide where to highlight certain elements more and when to overlap them. I am really interested in slippage and allowing boundaries to melt into each other. It’s a very intensive drawing process, yet in the final image all that remains of that process is the faint glow of the color pencil on the verso, reflected onto the wall.

DC: It is, like etching, scratching away, removing. You treat the vessels just as you treat the bodies.

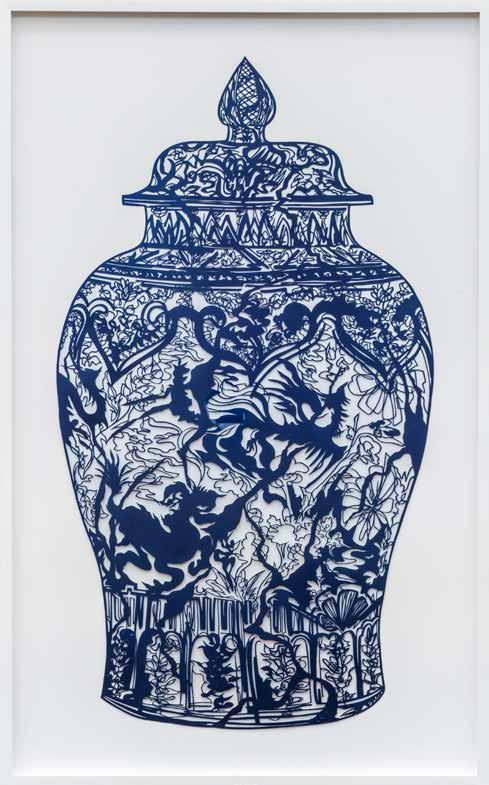

AB: I was thinking—during COVID, when we didn’t have access to museums and galleries—many were making their archives available. I started rummaging through their collections in search of Asian art and was immediately confronted by their focus on our connection to porcelain vessels or ceramics – we are constantly denied representation in the form of the human body, but objectified through vessels.

DAC: There is a way that certain institutions erase our cultural narratives, the links between the present and the past. But one cannot exist without the other, they collapse onto each other to exist.

AB: I view our cultural narratives as an equalizer. We wouldn’t be who we are without each experience. The works are all based on ancient vessels; I started sourcing images from museum archives and projecting them, drawing, and inserting a lot of cracks…leaving increasingly more positive space.

DAC: Do you think of your process as taking away, exposing, or are you adding?

AB: Each cut adds dimension. The act of cutting can be so violent, but it also contributes to the definition of who you are and what you stand for. So

many people wouldn’t be who they are if they hadn’t endured those scars or those battles. And we are able to transform those into signifiers of such beauty and such resilience. Of-ten times the people that suffered the most are the most beautiful, the most radiant and giving people

DAC: It’s the scars. The scars...Are they all couples in this body of work?

AB: All the large-scale works are two people this time. Many are couples, some their chosen family, and one is a father and son who are an art collaboration duo. There’s a side of intimacy, love, and quiet power… those are the gestures that I see…not the performative side. The ones we don’t always get to see. And it’s beautiful that they are able to release that and let go. Not only am I able to witness that touch and that quiet power, there is a sense of okay-ness between them. I also know that the way each person is holding each other reflects how I would also hold them, and how they would hold me.

DAC: I love how you chose the couples, to frame love this way. What is about each pairing that you wanted to focus on?

AB: I associate certain people with certain patterns or certain flora and fauna, specific to their unique narra-tives—their own history or my relationship with them. For example, one work features a motif within the figure that is a traditional pattern in male Vietnamese garments. They are engraved onto the skin and start to seep into one another.

Touch naturally came up, especially during COVID, being denied touch and proximity to one another. There was a desire to see that on a daily basis and work with it; to still have it in my life.

The limits of my language are the limits of my world, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

Framed dimensions:

84 x 56 in

213.4 x 142.2 cm

I remember opening you into words, gently, with a single question, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

Unframed dimensions:

100 3/4 x 49 3/4 in

255.9 x 126.4 cm

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

Framed dimensions:

56 x 106 in

142.2 x 269.2 cm

If I had the words to tell you we wouldn’t be here now, 2020

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

Framed dimensions:

110 1/2 x 65 in

280.7 x 165.1 cm

for hunger is to give the body what it knows it cannot keep, 2020

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

122 x 65 in

309.9 x 165.1 cm

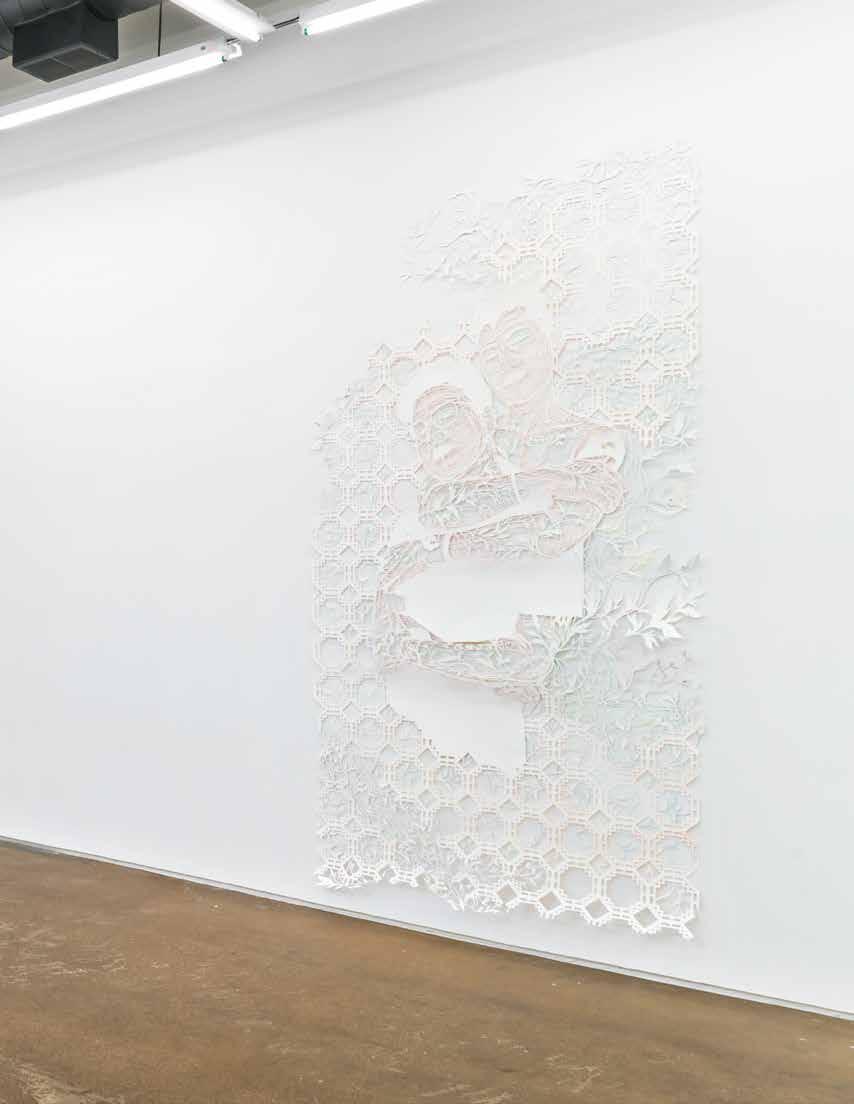

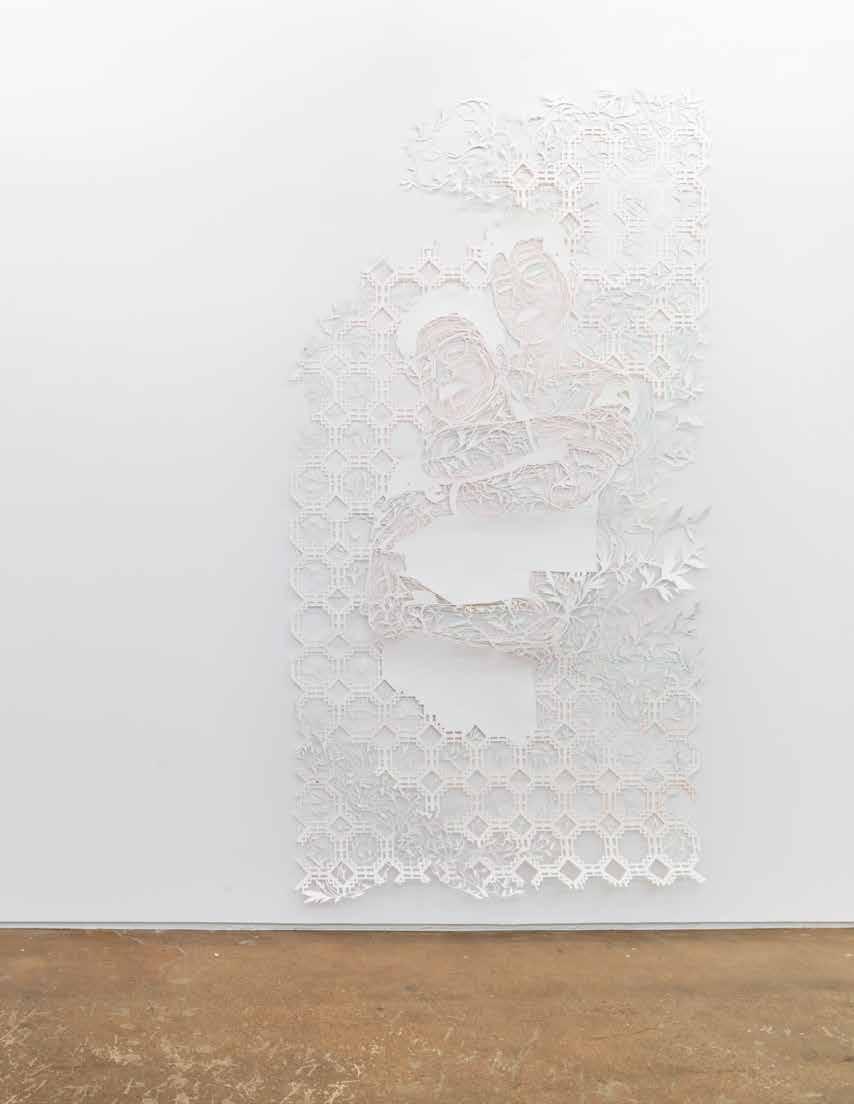

Flinging himself in an impossible direction, a future outside the photograph, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

91 1/2 x 57 1/2 in 233 x 146.1 cm

When they move on, it’s just us, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

34 3/4 x 26 3/4 in

88.3 x 67.9 cm

Bui (b.1992, Bronx, NY) received their BFA from Maryland Institute College of Art, Baltimore, MD (2016). Bui has had recent solo exhibitions, Hudson D. Walker Gallery, Provincetown, MA (2020), Laband Art Gallery, LMU, Los Angeles, CA (2019); Lawndale Art Center, Houston, TX (2018). Bui’s work has recently been included in exhibitions at Artspace, New Haven, CT; Orange County Center for Contemporary Art, Santa Ana, CA; the McNay Art Museum, San Antonio, TX (2022); USC Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, CA (2021); Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Houston, TX (2020); Blaffer Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, TX (2019); and National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C. (2019).

Public collections include the Eaton Workshop, Washington D.C.; Arkansas Museum of Fine Arts, Little Rock, AR; Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington D.C.; and the Pennsylvania College of Art & Design, Lancaster, PA. They are a recipient of The Outwin Boochever Prize (2021) and MICA Alumni Grant (2018). Bui has received fellowships from Fine Arts Work Center, Provincetown, MA (2019); Yaddo, Saratoga Springs, NY (2019); The Growlery, San Francisco, CA (2019); and Houston Center for Contemporary Craft, Houston, TX (2018). Bui lives and works in New Haven, CT.

Cruz (b.1974, Philadelphia, PA) received his BFA in Painting from Pratt Institute, NY and his MFA from Yale University, CT. He attended Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and completed the AIM Program at the Bronx Museum, New York. Recent and forthcoming solo exhibitions include Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA (2023), Galleria Poggiali, Florence, IT (2023); moniquemeloche Gallery, Chicago, IL (2021, 2019); Halsey Institute of Fine Art, Charleston, SC (2024); and Wave Hill Museum, Bronx, NY (2024). Forthcoming group exhibitions include the Zuckerman Museum, Kennesaw, GA (2023); Minneapolis Museum of Art, Minneapolis, MN (2025); DeCordova Sculpture Park and Museum for the New England Triennial, Lincoln, MA (2022); The Block Museum at Northwestern, Evanston, IL (2022); Institute of Contem-

porary Art Boston, Boston, MA (2022); Museum of African Diaspora, San Francisco, CA (2022); Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY (2019); Ford Foundation, New York, NY (2019); McNay Museum, San Antonio, TX (2019); and the Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C (2019).

His work is in the collections of El Museo Del Barrio, New York, NY; Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, MA; 21c Museum Hotels, Louisville, KY; and Pierce & Hill Harper Arts Foundation, Detroit, MI. Cruz lives and works in New York City where he is the Assistant Professor of Visual Arts at Columbia University. Recent residencies and fellowships include the LMCC Workspace Residency, New York (2015); Gateway Project Spaces, Newark, NJ (2016); BRIC Workspace Residency, Brooklyn (2018); Neubauer Faculty Fellowship, Tufts University, Boston (2018); and the Joan Mitchell Foundation Painters & Sculptors Award (2018). Cruz lives and works in New York City, NY.

The limits of my language are the limits of my world, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

Framed dimensions: 84 x 56 in 213.4 x 142.2 cm

I remember opening you into words, gently, with a single question, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

Unframed dimensions:

100 3/4 x 49 3/4 in 255.9 x 126.4 cm

When they move on, it’s just us, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

34 3/4 x 26 3/4 in 88.3 x 67.9 cm

Flinging himself in an impossible direction, a future outside the photograph, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

91 1/2 x 57 1/2 in 233 x 146.1 cm

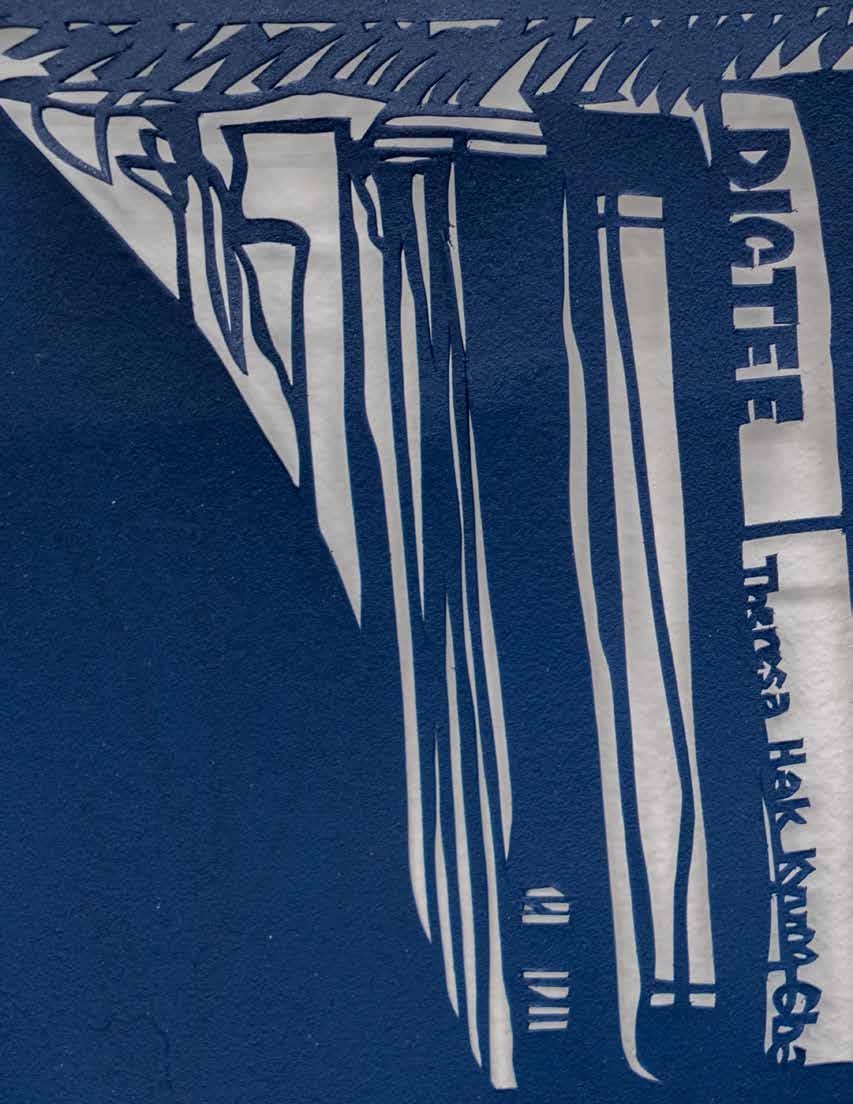

theoriginalcalloutqueen, 2021

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

Framed dimensions: 56 x 106 in 142.2 x 269.2 cm

If I had the words to tell you we wouldn’t be here now, 2020

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

Framed dimensions:

110 1/2 x 65 in

280.7 x 165.1 cm

for hunger is to give the body what it knows it cannot keep, 2020

Hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

122 x 65 in

309.9 x 165.1 cm

Vessel 4, 2021

hand-cut paper, ink, pencil, paint

33 3/4 x 21 in

85.7 x 53.3 cm

Monique Meloche Gallery is located at 451 N Paulina Street, Chicago, IL 60622

For additional info, visit moniquemeloche.com or email info@moniquemeloche.com