4 minute read

LETTERS

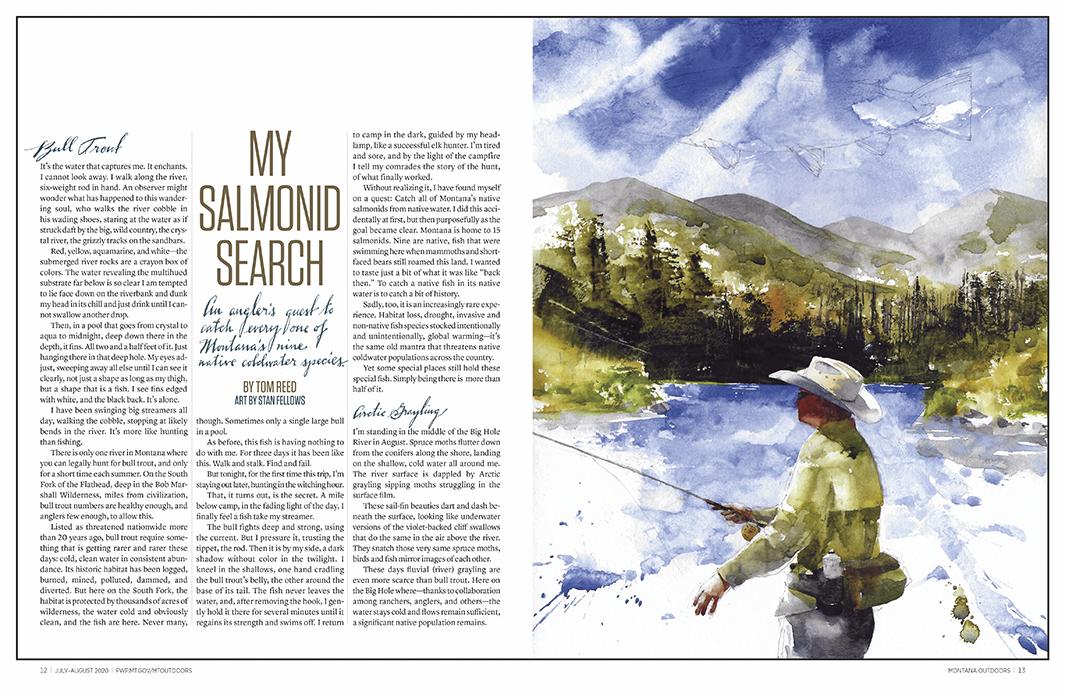

Inspirational essay I received my July-August issue today and read every article. My favorite was “My Salmonid Search.” The writer did a great job telling of his adventures while weaving in important conservation messages about coldwater fish. It made me want to do my own salmonid search and help those species any way I can.

Jess Carlson Missoula

Too many caught? In the essay “My Salmonid Search,” the author wrote that, while fishing the Big Hole, he released back into the river “probably [his] 20th eight-inch grayling of the day.” Then, possibly recollecting the “fragility” of Arctic grayling that he’d mentioned earlier, the author stopped fishing, stating that he “didn’t need to catch any more.” I question why catching and releasing just one grayling wasn’t enough. Many fish that anglers catch and then return to the water end up dying, especially in August, when the author was fishing. So several of the fragile Arctic grayling that he caught and released likely died. This article illustrates a thoughtless negative behavior that affects a fragile fish species at high risk of elimination from our Montana waters.

Don Lodmell Hamilton

Jim Olsen, FWP fisheries biologist for the Big Hole River, replies: I’m pleased to see concern for Arctic grayling both by the essay’s author and Mr. Lodmell. The “fragility” in the essay refers to the population, not individual grayling. Yes, the mortality rates of released salmonids can be extremely high when water temperatures exceed 70 degrees and fish are played to exhaustion—which is why FWP closes the Big Hole to hot afternoon and birds’ declining populations in Montana. How much disturbance is caused by a 10-person team of wildlife biologists setting mist nets across streams, herding ducks downstream, capturing migrating birds, and then physically handling them? Your story suggests such disruptive “duck recaptures” happened not once but many times in 2019. Are these practices contributing to the harlequins’ welfare?

Joe Kerlavliet Cascade

evening fishing in late summer— but otherwise it is more like 5 to 10 percent. Providing fishing opportunity is an important aspect of fisheries conservation. For some people, just knowing that fish are there is enough. But others need to catch fish to maintain both their connection to the fish and desire to help conserve the population. It’s a treat to catch grayling on the Big Hole. Even die-hard trout anglers think it’s cool to catch them. That’s one of the reasons so many anglers support grayling conservation.

We don’t got this I was pleased to see your Sketchbook essay about how men think they don’t need to be as careful as they should be (“I’ve got this,” July-August). We lost two wouldbe-hero fathers trying to rescue their families from the Spokane River on the weekend before the Fourth of July. Their family members were wearing life jackets, but they weren’t. Sad. Your admonitions were right on.

Dick Thiel Spokane, WA Thanks for the well-thought-out perspective on the “I’ve got this” attitude that’s in many men’s DNA, including my own. Recently I went trout fishing with a buddy on a stream near St. Regis. As he and I departed camp for different stream sections that morning, he said, “Be careful.” “I’ll be fine,” I replied. Not long afterward I ended up stepping into a very deep hole in the creek and was almost sucked into a log jam downstream. I easily could have drowned. I’ll be more cautious on the next outing, and maybe invite my buddy to fish with me instead of going our separate ways as we usually do.

Mike Burke FWP Budget Analyst Helena

Is handling harmful? Your report on the “grim future” of harlequin ducks (“Grim Future for a Festive Bird?” November-December, 2019) names “disturbances by backpackers and other mountain visitors” as one of the causes of the beautiful Chris Hammond, FWP nongame wildlife biologist in Kalispell, responds: When biologists study any bird species, including harlequin ducks, the animals usually need to be handled. That’s the only way we can band birds to learn where they winter and breed, and thus help protect those critical habitats. All FWP research methods are required by the Animal Welfare Act to undergo substantial review from an International Animal Care and Use Committee before we do any field work. The committee includes a veterinarian; a practicing research scientist; a member not affiliated with the organization doing the research; and an ethicist, lawyer, member of the clergy, or other nonscientist who provides a layperson perspective. Occasionally a bird dies from handling stress—though we’ve never lost a harlequin due to overhandling— but almost all survive and contribute to the scientific knowledge we use to conserve bird populations.

EDITOR’S NOTE: COVID-19 restrictions involving social distancing may affect outdoor activities in Montana this fall. Please check fwp.mt.gov or mt.gov for information about hours, capacity, and other details before making plans. Also note that the Centers for Disease Control recommends greater social distancing (and the use of face masks) than shown in several photos in this issue that were taken before the pandemic began. CORRECTION In the article “Blaming the Birds” (May-June 2020), the Missouri River fly-fishing guide quoted on page 43 is named Brian Scott, not Mike Scott.