4 minute read

ONE-TRACK MIND

A determined Mooresville resident dodges nature, regulations to construct his lakeside line

Photo essay by DANIEL COSTON

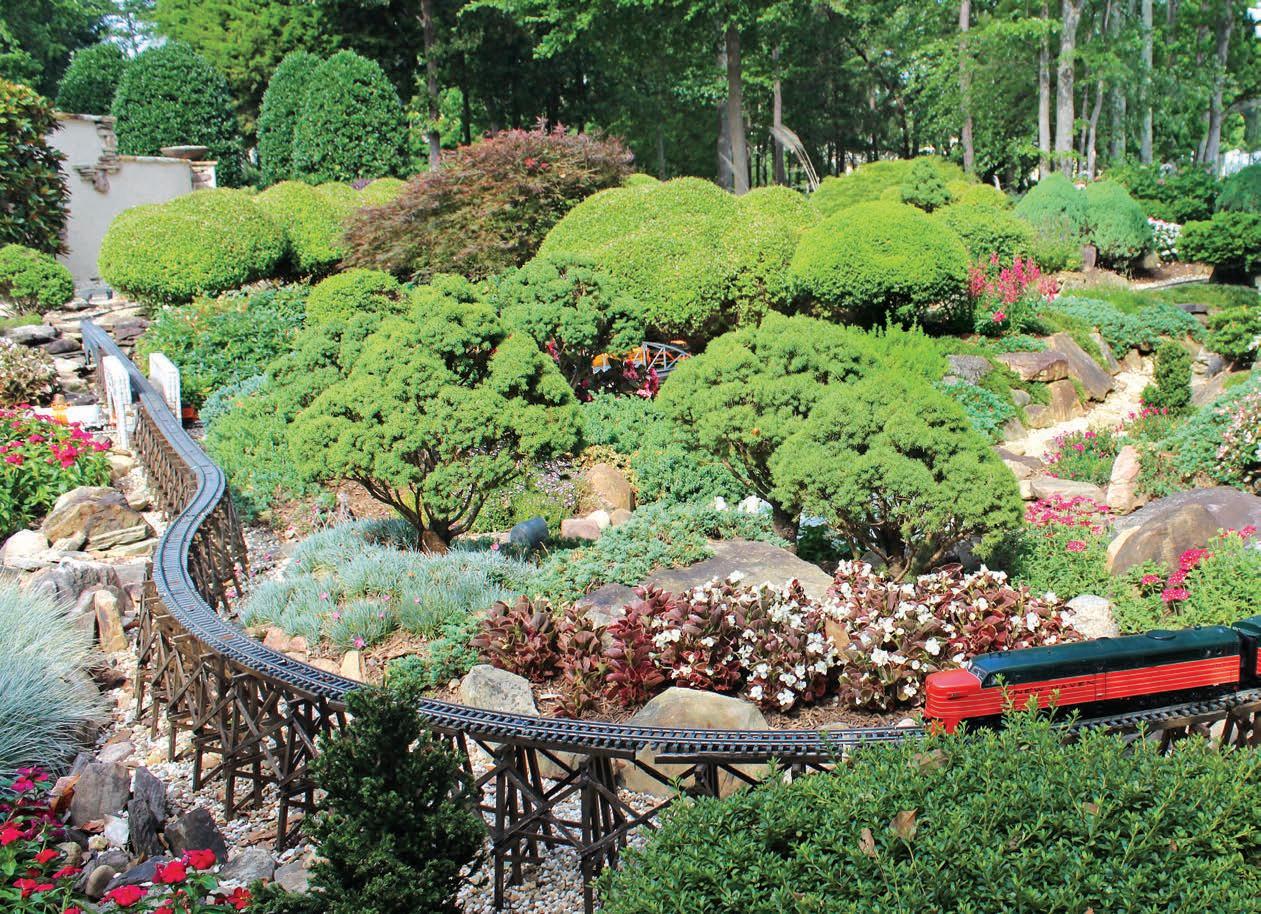

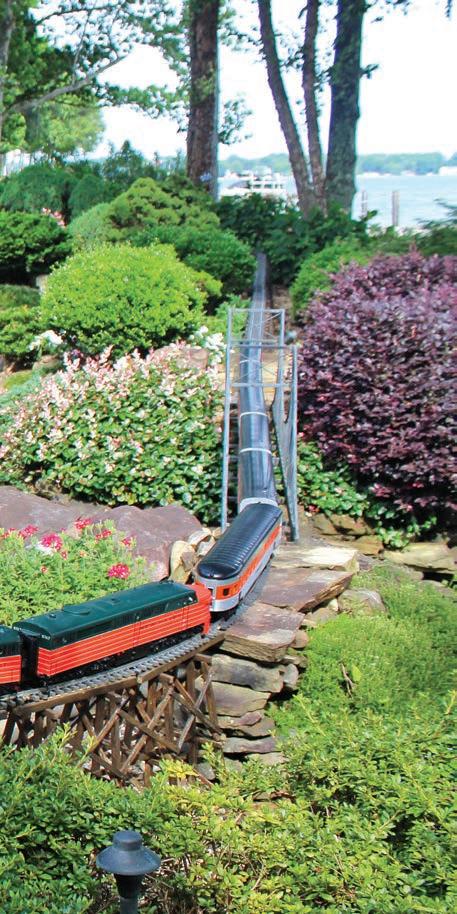

Lou Paone’s backyard garden at The Point community in Mooresville features 485 feet of model train tracks.

Paone designed the garden’s terrain to evoke the “lush and rugged character” of the Pacific Northwest.

Paone admired a model train display 25 years ago and thought he’d take on a similar project if he ever had the time. A yellow jacket attack and waterborne infection that nearly cost him the use of his legs gave him the opportunity.

On any given evening at The Point in Mooresville, you might hear the distant reverberation of a train. It could be a real-life freight rolling on the Norfolk Southern line that runs north-south through Lake Norman. Or it could be one of Lou Paone’s four model trains, 1/32nd-scale locomotives and cars that broadcast a train whistle recording as they whip around the 485 feet of track in his back garden.

Paone, a 72-year-old managing director at Deloitte Corporate Finance, designed and built all of it in the 5,000-square-foot garden behind his waterfront home, complete with shrubs, owers, bushes, and rock formations. He created it a er twin disasters. He and his wife, Rosemary, moved to The Point in 2007. A year later, Paone, a lifelong gardener, stepped on a yellow jacket nest while working in a plant bed on the property. The wasps stung him nearly 30 times. About a week later, with his wounds still open, he contracted a waterborne bacterial infection. “I almost lost the use of my legs,” he says.

Paone had to recuperate for several months while he worked from home, unable to travel for business, and he had time on his hands. He remembered a friend’s neighbor he’d met 25 years before who had built a model train display in his compact garden and spa. If I ever have the time and the space, Paone thought then, I’ll do the same. Now he had both, and he started to research garden railroads. “The internet is amazing,” he says. “I found tutorials, articles, and chat rooms that provided me with answers to many of the questions I had for designing and building a garden railroad.”

Paone had always admired “the lush and rugged character of the Paci c Northwest.” As he recovered, Paone removed trees and dumped soil to level the 100 feet between his house and the shoreline, then painstakingly built more than 125 feet of interconnected wooden trestles to guide the engines’ journey through the garden. The terrain beneath it contains waterfalls, a pond and cove, a river gorge, and a dry riverbed. He even took an online bonsai class so he could shape shrubs and ornamental trees.

He found a tutorial from a pair of modelers in Australia to learn how to build the stone bridges and another from a U.S.-based modeler about how to stabilize the stainless-steel track as it expanded in extreme heat and contracted in cold. One way to answer those questions: Spend a lot of money. Stainless steel conducts electricity better than any other metal and doesn’t corrode. It costs $15 per linear foot, and Paone spent $7,000 on the track alone. He used 500 plants at $30 each and 40 pallets of stone. Each of the four train engines cost between $750 and $1,500.

Then came the regulatory hurdles. “I had a ceaseand-desist order from the (N.C. Department of Environmental Quality) that stated, ‘If you continue to upset the naturalized area along the shoreline without getting our approval, you’re going to be ned $2,000 a day.’ I immediately called them and said, ‘What do I need to do?’”

Paone had to add trees back to the property to re ect the original number and amend his original design for the pond because it encroached on a shoreline setback requirement.

“Duke Energy was also alerted by the NCDEQ because I was building a waterfall and pond that were using a secondary irrigation pump,” he continues. “Duke Lake Services only allows one irrigation pump per property for lakefront homes to conserve lake water.” Paone redesigned the system to send water from the over owing pond back to the lake.

His last hurdle: The Point community’s architectural committee, which told him his plan had numerous violations of their code and that the model trains were “toys.” (The committee prohibits permanent toys visible from the lake on lakefront property.)

Paone did what he would at work: He made a PowerPoint presentation to address each concern. “I then brought in two of the railroad engines … and made the argument that they were essentially a unique garden accessory to a naturalized garden landscape,” he says. “The committee was immediately taken by the visual attractiveness of the model train engines.”

It took about three months for him to win approval. But Paone says the trials were worth it. “People o en say, ‘Your grandsons must love it,’” he says. “They do love it, but kids get easily bored if they are not constantly active. It’s the adults that will stand there and be mesmerized by the layout and detail.”

DANIEL COSTON is a photographer in Charlotte.