It’s fair to say not many classic bikes have had the impact that the Honda CBR900RR FireBlade has…

Back in 1992, when the superbike genre was still in its infancy, one man had a dream that would change the motorcycling world forever. Ignoring the call for bigger, faster and heavier machines, Tadao Baba penned the “light is right” philosophy. He wanted to design a bike that could carve through corners with ease, produced good power and had good brakes.

Fast-forward 30 years, and the latest incarnation of the Fireblade is the most powerful and most technically advanced yet – with 215bhp at a dizzy 14,500rpm – it’s around 100bhp up on the original model, with the power-to-weight ratio 79.5% higher. The experience of riding the latest model brings as much joy today as it did in 1992. Are you moved by Dreams?

Find out more:

For 30 years the Honda CBR Fireblade has been the benchmark big-bore sportsbike for a generation of motorcycle riders. Developed in the late 1980s, when sportsbikes were fast, fat and heavy, Honda’s CBR900RR FireBlade turned race-replica motorcycle design on its head. This was a relatively lightweight machine, featuring mass centralisation and with the focus on agility through the corners, not sheer power in a straight line.

On release in 1992 the CBR900RR became the yardstick for all large-capacity sportsbikes and it was mostly down to one man –the machine’s maverick designer Tadao Baba – who was insistent that a sports bike should be fast and agile. Over the years the Blade moved from 893cc through 918cc, 929cc and 954cc versions: each of which bore the hallmark of Baba-san.

For 2004 the machine became the Honda CBR1000RR Fireblade. The capital ‘B’ was dropped in honour of the retiring Baba, but the ante was upped, with an all-new angular styling and under-seat exhaust pipe following Honda’s MotoGP machines. Further new versions came along over the years – each successively more technically advanced until the latest 2022 version which is the pinnacle of sportsbike design.

Out on the track the Blade had a slow start due to capacity rules in the various racing classes. Even early on though, it would win the USA’s Formula Xtreme title and do well in production racing, including at the Isle of Man TT races until the 1000cc model of the Blade could finally compete in World Superbikes, taking the title in 2007 with James Toseland. A total of four British Superbike Championships would be won with Ryuichi Kiyonari (three) and Alex Lowes.

Today after three decades and many model generations the story of the Honda CBR Fireblade continues on both road and track…

Thanks to Yuko Sugeta who helped with the original interviews with Tadao Baba way back in 1998/99.

Thank you to Stuart Barker for help with both the Isle of Man TT exploits of the FireBlade and its World Superbike results and story too.

Thank you as well to the likes of Dave Hancock, Bob McMillan and Phillip McCallen as well as many from Honda UK, Honda Europe and American Honda, big thanks to ex-Honda UK employee Scott Grimsdall. Thanks also to Neil Fletcher, Nick Bennett, Iain Baker, Havier Beltran, John McGuinness, Tom Neave, Glenn Irwin, Ryo Mizuno, Takumi Takahashi and Becky Simms from Redwing Media.

Thanks also to all the journalists who helped with quotes and images (seen in the original Haynes book and this latest updated for Mortons Publishing) and they are: Roland Brown, Andy Findlay, James Wright and Sue Ward from Double Red, Martin Child, Steve Westlake and Olly Duke, Rob Gray, Trevor Franklin, Chris Moss, Marc Potter, Warren Pole, John Cantlie, Alex Hearn, Dan Harris and latterly Alan Dowds and

John Hogan. Satoshi Kogure, Vassilis Karachilous, the late, great Ken Wootton, Jonathan Bentman, Ben Wilkins, Mitch Boehm and the late, Greg McQuide, Dean Adams.

The biggest of thanks must go to Roland Brown for raiding his archives and then donating most of his fee to Riders for Health/Two Wheels for Life. Thanks to Graeme Brown/2Snap for the excellent Honda WSB shots and Valerio Piccini. Mortons Archive, Erion Racing and Ken Vree, Honda UK, and big thanks to Honda R&D in Japan for reproducing the original model illustrations at no cost whatsoever.

World Superbikes – The First 15 Years (by Julian Ryder) Haynes Great Bikes – The Honda FireBlade (by Rob Simmonds)

Author: Bertie Simmonds

Design: BURDA DRUCK INDIA PVT. LTD.

Publisher: Steve O’Hara

Advertising: Charlie Oakman coakman@mortons.co.uk

Published by: MORTONS MEDIA GROUP LTD, MEDIA CENTRE, MORTON WAY, HORNCASTLE, LINCOLNSHIRE LN9 6JR Tel. 01507 529529

ISBN: 978-1-911703-10-5

PRINTED BY: WILLIAM GIBBONS AND SONS, WOLVERHAMPTON

Testing, testing, testing: it’s almost never-ending. This is Suzuka race circuit and it’s 1989.

This legendary Japanese circuit that has echoed to the sounds and seen the sights of legendary Formula 1 car events and 500cc Grand Prix races now reverberates to a more solitary sound.

The sound is unmistakably a four-stroke; it’s clearly a four-cylinder machine of 700-900cc or so of capacity, but the crude sand-cast metal parts, movable engine mounts, strange tank shape, fairing and chassis parts of indeterminable origin and overall shoddy finish do not tell you that this machine is an early pre-production version of a bike that will become a new byword for street motorcycle performance.

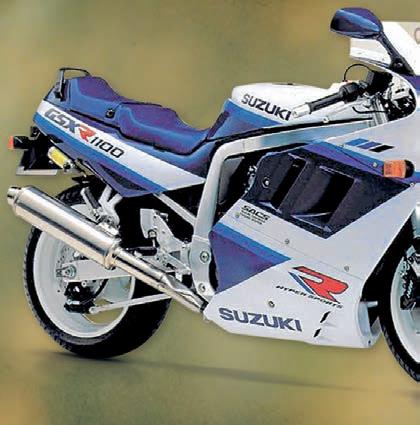

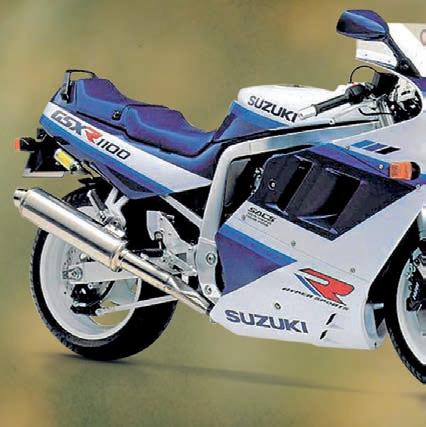

Occasionally the single machine is joined on track by one or two other machines. These are much sleeker, more polished, the finished items no less. These are the current crop of litre-class sports bikes: Suzuki’s GSX-R1100, Yamaha’s FZR1000 EXUP, Honda’s own CBR1000F and Kawasaki’s blisteringly-fast ZZ-R1100. Compared to its peers, this development Honda looks ugly and yet feels purposeful.

Every so often this grotesque machine pulls into the pits and stops in a garage.

Almost immediately the rider is swamped by technicians wearing the ‘flying wing’ motif of the mighty Honda corporation. They interrogate the rider about engine performance, handling and braking: everything is noted down. Engine position, suspension set-up, then the rider is asked how the motor felt, what were the tyres like? Any scary moments? Did the seat feel comfy? Everything and then some: still buzzing on the adrenalin of riding the challenging and scary Suzuka circuit, the test rider answers the questions as best he can.

Changes are made and the bike accelerates out of the pit-lane and goes back out on to the track. Security is tight. There aren’t any cameras and certainly no smart phones to instantly leak spy pictures to the internet.

Big sports bikes had become stale: they were big, heavy and almost clumsy creatures. A new Honda machine was about to change all that.

ABOVE: The bike it would become: the finished FireBlade at the 1992 launch with Sean Emmett on board. Years of development would lead to this…

ABOVE: The bike it would become: the finished FireBlade at the 1992 launch with Sean Emmett on board. Years of development would lead to this…

That bike burning up the track back in the late 1980s is an early ancestor of the Honda CBR900RR FireBlade and the later CBR1000RR Fireblade and over the next 25 years it will become the machine by which all other sports bikes are to be measured, but let’s start at the beginning and check out this little fellow. One of the technicians isn’t wearing any overalls; he’s in leathers. He’s Tadao Baba – chief engineer for Honda Research and Development. This is his first bike as project leader and the scuffs on his leathers tell you that he takes his work very seriously indeed.

It’s fair to say that – for a Japanese man and Honda executive –Baba-san is a maverick. You’ll spot him in the pits sitting on a large fuel drum, puffing away at one of his 20-a-day cigarettes. You’ll see him out on track riding hard – and fast – and then crashing when he pushes just that little too far. But Baba-san has been around the block a few times and in a time of 80s excess where bigger is better and bigger and faster is better still, he has a plan.

“Bikes at the time in the 1980s were very fast. WHOOSSH,” Baba mimes with a smile on his face, making his hand shoot upwards, like a rocket. “But I felt they never turned like a race bike, there was no ‘flickflack,’” he again holds his hand up to show what he means, this time bringing it down in a chopping motion then mimicking a bike flicking through a chicane as he makes his hand move from the vertical to the left then quickly back upright and swiftly down to the right. “You see, I wanted a bike that would be good into the corners, which produced good power and had good brakes.” He adds: “The CBR900RR made its debut in 1992, but it took us more than three years to reach that point.

“At that time, the Japanese market was full of race-replicas, such as NSR250 two-strokes and CBR400RR four-strokes while in Europe the power war had started with the Kawasaki ZX-10, GSX-R1100, and our CBR1000F. Up until then we called these bikes ‘super sport’, but, I

thought ‘wait a minute, are these big and heavy bikes really ‘super sport?’ I thought that going down a straight at high speed doesn’t mean ‘super sport.’ As it is a sport bike, it must be sporty. The performance must be fun, easy and quick to control.

“A sport bike should be controlled freely as to the rider’s wish. In this aspect, all those big monsters were not good enough to be called a sport bike. Yes, they were fast, but, heavy and to my mind they were quite dull. We realised that we should create a completely new, enjoyable world for sport bike lovers. We knew we must go back to the first place and start again. We wanted to give riders something over which they had ‘total control.’”

Total control: these two words would come back again and again as what became the Honda FireBlade was developed over the next quarter of a century, but what of Honda’s existing big-inch sports bike of the time? Initially the CBR1000 was marketed as a ‘super-sport’ bike. But since its release in 1987 it had transformed itself from a cutting-edge sports machine into a more laid back sports tourer. Baba-san explains: “As the CBR1000’s development proceeded, we had to think of practical aspects, such as riding long distance on an autobahn comfortably, taking a passenger on the pillion seat and so on. Then, it became more like a touring bike, but with sporting pretensions. We wanted to keep it a bike that people could use on twisty roads and sweeping corners, but its ever increasing weight made it impossible to make it a real sports bike. So, from those ideals came the start of the concept of the CBR900RR FireBlade.”

At the start of the FireBlade story then, it was all about-face as the impetus for the machine came from research and development rather than the marketing department. Initially the marketing men would find some new area to exploit and brief the R&D team to make a product that was suitable – not so with the new CBR-RR.

ABOVE: The new model CBR900 wasn’t an ‘F’ but a full-on ‘RR’ racereplica, as shown on this marketing diagram.

At the earliest stages of the development, the leader of the project was Yoichi Oguma. Oguma-san was from Honda’s racing division –Honda Racing Company or simply ‘HRC’. This showed you where the driving force for this project came from, but – thankfully for us – this machine wasn’t going to be designed as a sports-production or ‘homologation special’ as the final capacity was not going to be suitable for production racing rules of the time. After just six months of driving the project forward, Baba-san took over and this was to be his first time in overall charge of a project. By this time it was to be a no-holds barred super sports machine, not with the ‘F’ road bike suffix, but the ‘RR’ race designation.

“At this time,” recalls Baba-san, “it was still before even an egg of the FireBlade had been made! We had only a very rough idea of what we wanted and very little design had been done, so the first step was to refine the idea and decide the machine lay-out. It was a very exciting appointment for me at the time. I knew the project would become very

ABOVE: Early development sketches hinted at the race-oriented nature of the bike…

important for Honda. So I was highly motivated to make this machine a complete success. Of course I was nervous! But I was pretty confident, too, as I knew my strong points and weak points from my experiences at Honda up until then. I love riding an out-and-out sportsbike, and I love to feel satisfied when I can control it as I want to. I knew my strong lust for conquest would lead the project in the right direction.”

For Baba-san himself, this was the beginning of arguments, stress and sleepless nights as he strove to make a bike with plenty of power and light weight – this final fact being what he felt was the real key to the project. “I was happy to get this project – very happy, but the development life of the CBR900RR was not always so cheerful. I suffered a lot: we all on the development team suffered a lot! Many times we got very, very stressed out and often worked long hours through the night to achieve our goals.”

Obviously, Baba’s inexperience in leading a whole project team made the task more of a challenge, but he felt he knew what he wanted from

BELOW: Later, more detailed sketches showed the DNA of the original bike we know and love today.

“Oguma-san from HRC initially led the project, this showed the direction. Not a road-going ‘F’ but a full-blooded ‘RR’ race-replica.”

ABOVE: Honda’s CBR1000F was a good sports-tourer – but no out-and-out sports machine.

each individual in the team and the contributions they could make to the final product. “Most of the engineers were younger than I was,” he remembers, “but, they all had different backgrounds to be the particular specialists on chassis, engine, suspension or whatever. I respected their thoughts and ideas and always listened to them. I understood that my work was to gather their best ideas and to bring them together as a whole product. A good engine doesn’t sell a bike. Nor does a good chassis, you have to bring these great ideas into a whole that must gel together: that’s the secret.”

Professional conflict with other members of the team cropped up from time to time, as (understandably) long nights and a high stress environment took its toll. “Rumours began to circulate,” smiles Baba. “These rumours were that the young engineers would complain that when it came to cutting the weight of a component, ‘Baba-san never says yes.’ Apparently the young engineers used to call me ‘Hotoke no Baba’ or Buddha Baba in English, maybe because I always thought I was right,” he laughs. “Despite that, I could be like a thunderstorm when I got angry. Maybe, some of them were afraid of me – maybe they still are? It’s because I can never let myself compromise – and we couldn’t compromise on the weight of the CBR. I guess I am pretty stubborn! I think aging has made me milder, but others may not agree.”

Also, after years in a test position where he could tell engineers what was good or bad about their product, for Baba the boot was now on the other foot and he had to listen to what the test team said about his machine and sometimes this made things difficult. “Before, as a tester, I used to shout at the engineers when they made me ride a dangerous test bike. ‘How could you let me ride such trash?’ I would say, but, suddenly, there was no more shouting.” At the time the full specification for the machine that would become the FireBlade was still not pinned down.

At first, the FireBlade project was most definitely a 750cc across-theframe four-cylinder – despite initial denials that it was always going to be a new cubic capacity class of motorcycle. Pictures later discovered would show a motorcycle closely aping the look of the CBR400RR TriArm. “Ah yes first the FireBlade was a 750,” recalls Baba. “This was what we made at first, but then we thought ‘we already have a VFR750, why not make it a 1000?’ But then to make the FireBlade 1000cc would put it

against the CBR1000F. Instead we thought we would make a new class of motorcycle: something unique. This is what we decided to do.”

At the second Honda FireBlade Day in 2008 (or should that be Fireblade – as the bike lost the capital B as it went to a full litre-spec in 2004) Baba-san sat with me and explained how he and his team came up with the specific capacity of the original model FireBlade. “Okay, so why 893cc? Look at this,” Baba-san was sketching out a profile picture of a sports bike – the CBR750RR. “We literally took the original measurements of the CBR750RR: wheelbase, castor, trail, everything and then looked at the motor, what could we do with it to make it better? We realised that if we kept the bore but stroked the motor we would get 893cc – and that’s why it became that cubic capacity. We found that the 750 had good top-end power, but with 893cc we also had good torque. This was a big advantage for us.” And this is what helped give the FireBlade its real advantage both on track and street: many of the test riders would get off the FireBlade mule and complain that it didn’t feel that quick compared to the other machines, only to find that the stopwatch told a different story.

“Our main aim was that – first of all – we wanted to build a big sports bike which was actually lighter than a 600cc model. Then, to gain the right stability for the machine, the chassis dimensions and riding position were fixed during our extensive testing. So, at the end of all this we find that there is a limited space for the engine. As I mentioned, with the space we had left we thought we could go for something bigger than 750cc hence we managed to get an 893cc powerplant.

“We really wanted a motor that could push this bike to around 161mph (260km/h) – that would be enough! From this data we could find exactly what maximum power we would need for the bike to get to this speed and from there what the displacement of the motor would have to be. That turned out to be 893cc, stroking that original motor. Obviously in later years we would up the displacement to more than 900cc. Like the drop in weight, we found we could squeeze more from the powerplant also.

“But at the beginning we chose the layout of the best machine from a number of different options, they were not so different as the direction was the same and the ideal point was the same: optimum power with as

“I always thought I was right. I could be like a thunderstorm when I got angry. But I couldn’t compromise with the CBR900RR.”

little weight as possible. We had to decide where to draw the line, where we stopped scrutinizing each individual part. It was a big hurdle to go over at first, but with subsequent models of the original 900cc FireBlade we managed to mature the product little-by-little.”

It was early in the test schedule in 1989 when Dave Hancock from Honda UK became involved in the project. He was one of three

European test riders, the others being Bernard Rigoni from Honda France and Klaus Bescher from Honda Germany, who would test Honda’s latest creations in their varying forms throughout the test programme for their suitability in the European market. Honda USA and Japan had their own testers, mainly for reasons that many models for those parts of the world were pretty much for those markets only, such as the 400 four-stroke class in Japan and the big cruiser market in the USA.

“I was one of those test riders who was on the early version of the bike at Suzuka in 1989,” recalls Dave. “We had two days with this new bike. At the time they had just decided on the 900cc displacement. I’d ridden the 750 version earlier, even though the Japanese later denied categorically that they actually had such a machine! Also at this time it was fitted with a 17in front wheel as opposed to the 16in wheel which the production machine would later use.

“It wasn’t the prettiest thing on two wheels, but then again not many test bikes were. The chassis was a bit of a mish-mash of moveable engine mounts, sand cast bits and pieces and a swingarm that, I think, came from a CBR1000F. The tank also was nothing that you could really recognize, either. The engineers would experiment with different shapes and sizes in a bid to get something with the right shape for your legs and the right amount of fuel and the correct weight distribution.

“You’d come into the pits and the engineers would want to know everything. How the motor felt, suspension, the lot. Even if the bike didn’t look like much – and sometimes these pre-production development machines really looked pretty disturbing – it was surprising just how good even these early machines felt.”

Certain motorcycling fashions of the time over in Europe led to the testers wanting small changes made to the design of the bike, even at this early stage.

Hancock explains: “We all told Baba-san that the bike really needed upside-down (inverted) front forks. At the time the fashion was for upside downers, as most race machines were using them, but Baba was insistent. ‘They weigh too much,’ he would tell us. He was always emphasizing the problems of having too much weight or having mass and weight in the completely wrong place. That’s part of the reason why the bike had no rear hugger covering the back wheel and they made sure it didn’t need a steering damper on the road because that would simply add too much weight.”

ABOVE

At every stage Baba and the development team wanted to weigh up whether a part really needed to be on the bike. For the FireBlade development team, the best parts of a bike were the ones they could do without – hence keeping the weight down.

AND BELOW: Suzuki’s GSX-R1100L and Kawasaki ZZ-R1100 went more for the power and sports-tourer route.

12 Fireblade

AND BELOW: Suzuki’s GSX-R1100L and Kawasaki ZZ-R1100 went more for the power and sports-tourer route.

12 Fireblade