DALRYMPLE & VERDUN Dalrymple & Verdun Aviation titles land at Mortonsbooks.co.uk Visit: www.mortonsbooks.co.uk or call 01507 529529 FLYING SAILORS AT WAR Brian Cull, Bruce Lander and Mark Horan £15.95 LIGHTNING FORCE Fred Martin £19.95 NO PLACE FOR BEGINNERS Tony O’Toole £24.95 ATTACKER Richard A. Frank £14.95 SEA FURY Tony Buttler £24.95 SCIMITAR Richard A. Franks £19.95 D&V, Tempest A5 Duplex Flyer Feb 22.indd 1 19/07/2022 10:17:01

Author: Ralph Pegram

Design: Druck India Pvt. Ltd.

Publisher: Steve O’Hara

Published by: Mortons Media Group Ltd, Media Centre, Morton Way, Horncastle, Lincolnshire LN9 6JR

Tel. 01507 529529

Printed by: William Gibbons and Sons, Wolverhampton

ISBN: 978-1-911703-04-4

© 2022 Mortons Media Group Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Acknowledgements

Once again I have to acknowledge the assistance and input of ‘the usual suspects’, the staff at the Department of Research and Information Services at the RAF Museum in Hendon, and fellow researchers Tony Buttler and Chris Gibson.

Pemberton-Billing Ltd, renamed as Supermarine Aviation Works in 1916, was launched with the explicit intent to construct and champion flying boats, yet the company is remembered best for the Spitfire fighter, an aircraft that entered service just before the Second World War and remained in the front line throughout and on into the early years of peace. The Spitfire was built in far greater numbers than any other British aircraft and took on iconic status.

As it turned out, and despite the company’s original intent, the first of their aircraft to fly was also a fighter, designed and built in just seven days when war broke out, the last was a jet fighter/ bomber that took nine years from conception to first production. Neither could be called a success. In between there were numerous attempts to access the lucrative home and overseas markets for fighters and bombers, many paper projects and a few one-off prototypes. The story starts with the company based at Woolston, near Southampton, producing designs springing from the imagination of its founder, Noel Pemberton Billing, and ends with the last aircraft designed by the Supermarine Design Department while based at Hursley Park, where they had moved after the Woolston works were bombed in 1940. In between aircraft designs were produced under the successive leadership of Hubert Scott-Paine, William Hargreaves, Reginald Mitchell and Joe Smith with some of the members of their team serving right through from the era of the biplane flying boats up to the introduction of the supersonic jets.

In 1954 the two aircraft businesses, Vickers and Supermarine, managed jointly within VickersArmstrong since 1938, were formally merged as Vickers-Armstrong (Aircraft) and further integration of the two lines was put in hand. After a short period of illness Joe Smith, chief designer since 1937, passed away in February 1956 and the final decision to close the Hursley Park office, which Smith had opposed since the merger, was made in March. Design work continued, amalgamated increasingly with that of the Vickers team until 1958, when the Supermarine ‘brand’ had effectively reached the end of the road.

Ralph Pegram

Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers 3 Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1 – The Early Years 4 Chapter 2 – Aerial Attack – the Zeppelin 8 Chapter 3 – Flying Boat Fighters 17 Chapter 4 – Flying Boat Bombers 26 Chapter 5 – The Austerity Years 38 Chapter 6 – Fighters for the 1930s Part 1 Specification F.7/30 44 Chapter 7 – Fighters for the 1930s Part 2 Two-seaters, cannon fighters and twin-engine fighters 59 Chapter 8 – Bombers 73 Chapter 9 – Navy Fighters 83 Chapter 10 – A Superabundance of Jet Projects 95 Chapter 11 – Swift and Scimitar 106 Chapter 12 – Beyond the Swift – a Supersonic Fighter 121

Introduction

The Early Years

Noel Pemberton-Billing was one of the more questionable characters to come to prominence during the pioneer years of British aviation, and there are more than a few to choose from. Described by some variously as a maverick, eccentric or visionary his brief time in the aviation spotlight was marked by controversy. Maverick, yes, but only in the most negative definition of the term, eccentric, certainly but in a disagreeable and aggressive way, and visionary, not in the slightest. His arrogance, certainty in his own ability and judgement, total distain for those who held contrary views, and desire to be disruptive proved ultimately to be his undoing. But before that he has to be commended for establishing his own aircraft construction company and for employing

Hubert Scott-Paine as his works manager. ScottPaine would prove to be a most capable leader, steering the fledgling company through the First World War and growing it during the harsh years that followed.

It has to be said that Billing certainly had if not exactly friends then those who admired his energy and were supportive of his efforts in his early years in the world of aviation. Foremost among them were the editorial staff of both The Aeroplane and Flight, and he had no difficulty in getting articles of a favourable nature written about his activities.

In late 1913 Billing established an aircraft construction company, Pemberton-Billing Ltd, at a former ship chandler’s site at Woolston on the river Itchen just outside of Southampton. The company was launched with the clear intent to specialise in the construction of marine aircraft, an aim set out in a brochure issued prior to the Aero & Marine Exhibition at Olympia in April 1914 where its first aircraft was displayed, a small single-seat, singleengine flying boat given the name Supermarine PB-1 or P.B.1. This aircraft failed to fly but before Billing could embark on the construction of further flying boat designs war broke out. To his credit, he threw the resources of his company, distinctly limited as they were, towards war work.

The Seven-Day Bus

Billing, along with his friend and works manager Hubert Scott-Paine, had spent the formative months of the company’s life acquiring at auction a collection of useful material and part-built components from defunct aircraft businesses. They now had a ready stock upon which to draw. Billing said later that he had approached the heads of the new Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), established on 1st July 1914, to seek specifications for the type of aircraft for which they had an immediate requirement. These were duly provided and formed the basis for the first aircraft he set out to build, the P.B.9 or P.B. ‘Scout’ IX, as it appears on the sole remaining company drawing. However this sounds like typical Billing embellishment as the P.B.9 showed every sign of

4 Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers 1 CHAPTER

Noel Pemberton-Billing in 1916

The Pemberton-Billing P.B ‘Scout’ IX. Drawings adjusted from those prepared by the company for publication to reflect the aircraft as it actually appeared

being no more than a cheap, simplistic copy of an aircraft for which the Royal Flying Corp (RFC) had awarded contracts back in 1913 and which was in service already – the Sopwith ‘SS’ Scout or Tabloid.

This aircraft was very well known and had been illustrated and described in detail in the aviation press, not least when an example on floats won the 1914 Schneider Trophy Contest in April. Whether Billing really started by sketching the outline of the P.B.9 on the wall of the works is not verifiable, but stories of this type are common and pepper the narrative of aircraft and racing car design.

As was to be expected, the structure of the aircraft was entirely conventional. The fuselage was built on four longerons which on each side converged at the nose to meet and secure the ends of the forward engine mount beam. This was so similar to the arrangement on the Tabloid that the sketch drawings in Flight, copied from Pemberton-Billing company originals, resemble that aircraft rather more than the P.B.9 as it actually appeared when built. It has been suggested that the wings were modified from a set that Billing had acquired from the dissolved Radley-England company, which may explain how the aircraft was built so quickly. It may also explain the rather crude manner in which the wings attached to the fuselage.

Fig2

enabled the whole wing cell to be assembled as one unit and then slid along the fuselage to be attached. The spars of the lower wing were said to have been secured to the lower longerons by nothing more sophisticated than simple ‘U’ bolts clamped around them, and photographs certainly appear to support this. The tops of the front pair of inner struts were stabilised laterally by a couple of cross wires above the fuselage in front of the cockpit. It was a distinctly crude arrangement but effective. The tail surfaces were broadly similar to those on the Sopwith Tabloid. Billing had intended that the P.B.9 should be powered by an 80hp Gnome rotary engine but none were available. He therefore took the 50hp Gnome from the defunct P.B.1 flying boat and had that installed.

Flight reported that work on the drawings for the aircraft commenced on a Monday and construction the following day. On Tuesday of the following week, 11th August, the aircraft was complete and ready for testing. As a consequence of this truncated timescale it subsequently acquired the nickname of ‘The Seven-Day Bus’.

The only qualified pilot in the company was Billing himself and it is by no means certain that he had made any flights since acquiring his Aviator’s Certificate the previous year. This, famously, was done after no more than two or three hours’ tuition as part of a bet with Fred Handley-Page, a wager that Billing won. The first flight of the P.B.9 would need to be undertaken by a considerably more experienced

The Early Years Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers 5

The wings were both continuous, tip to tip, and were basically of single bay construction except that there were pairs on full length inboard struts that lay immediately adjacent to the fuselage sides. This 0 10ft

pilot. As business had become tight in the summer of 1914, Billing had rented out part of the works to Sopwith who were in need of a waterside facility from which to test their Bat Boat. Through this connection he had met Victor Mahl, one of Sopwith’s top engineers and one of the small group who had been with the company’s support team for their successful challenge for the Schneider Trophy in April.

Mahl had been taught to fly by Howard Pixton, the pilot of the Schneider aeroplane, who had taken over the duties of chief test pilot during Harry Hawker’s sales trip to Australia. He had obtained his Aviator’s Certificate on 14th May and very soon thereafter became an accomplished deputy to Pixton. It was Mahl who was asked to take the P.B.9 up for its first flights, which took place on 12th August. No problems were reported following these flight and it is said that a top speed of around 75mph had been achieved, which is not bad for just 50hp, if indeed the aging engine produced that much.

Little is known about the subsequent history of the aircraft although it was certainly transported to Hendon for further assessment, where it was viewed by Flight in January 1915, but no orders were forthcoming. Claims that it was still in service in 1918 are clearly incorrect as Billing used the airframe, stripped down and covered in slogans, as a pulpit from which to address crowds during his parliamentary election campaigns in early 1916. While the design of the aircraft may not have impressed, especially when compared to similar single-seat tractor types coming from Sopwith, Bristol, the Royal Aircraft Factory and others, the workforce had demonstrated their ability to build to an acceptable standard, quickly and efficiently.

Billing’s military career

Billing’s mercurial nature and desire for action saw him sign up for the Royal Navy Volunteer Reserve, which he joined on 20th October 1914 as a subLieutenant (temporary), reporting to the training depot HMS Pembroke III.

On 21st November Billing was a participant in a raid on the Zeppelin sheds at Friedrichshafen, located on the shores of Lake Constance. His exact role in this is far from certain as he is virtually the sole source for the narrative, but other officers in the RNAS described him as a transport officer. Three BE2c aircraft took off from a French airfield close to the border with Germany, made their way across Lake Constance and dropped nine bombs. One aircraft was brought down by gunfire and the pilot, Briggs, was captured. The other two returned to base, unsure whether they had been successful.

The three pilots who participated in the raid, Sdr Com E. F. Briggs, Flt Com. J. T. Babington and Flt Lt S. V. Sippe were all mentioned in dispatches and awarded the Distinguished Service Order as well as the French Légion d’honneur. Billing was not mentioned, despite his claims of having made a clandestine reconnaissance trip and other acts of derring-do. German records became available for review after the war and it was found that the raid had caused negligible damage. The reports made at the time, provided by an anonymous Swiss contact of Billing’s that told of both the Zeppelin and adjacent hydrogen generation plant having been destroyed, were total fantasy.

Billing was promoted to the rank of Flight Lieutenant (acting) on 1st January 1915 and on the 14th transferred to the RNAS. It is around this

Chapter 1 6 Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers

The P.B.9 at the time of its first flight. From left to right; Hubert Scott-Paine, works manager, Victor Mahl, Sopwith test pilot, and Carol Vasilesco, chief draughtsman

time that he decided to hyphenate his name, as Pemberton-Billing. What exactly he was engaged upon on behalf of the RNAS after his return to Britain remains somewhat obscure but when he resigned his commission at the end of the year he was promoted again to the rank of Temporary Squadron Commander on 1st January 1916. Some authors have questioned the veracity of that but it was definitely gazetted officially on 7th January 1916. During 1915 his company had been engaged in the design and construction of aircraft that Billing believed were essential for the defence of Britain from aerial attack.

The defence of Great Cities

In 1916 Billing published a book laying out his vision of how the aerial defence of Britain should be structured. This book, Air War: How to Wage it – with some suggestions for the defence of Great Cities, was an assemblage of articles he had written for various newspapers in the preceding years connected by new writing. In this he described the aircraft types that would be necessary for ‘The Defence of Great Cities’ as follows:

“(A) Patrol plane for home defence, especially by night… Horse-power required, 350 minimum, therefore the employment of two engines of 200-horse power will not only meet these requirements but will also provide that duplicate power plant which is essential to night flying.

(B) The observation machine—the eyes of the Navy and the Army. ….The horse-power necessary would be 150-175 minimum. Here I should install one 200-horse power engine.

(C) The bomb-dropper; possibly the most effective method of aeroplane offensive—the ‘longrange gun.’… Horse-power required, 125 minimum. Engine employed same as type B.

(D) The battleplane. Experimental, but must be rapidly developed and designed to carry the largest guns possible, up to 5in. This type should be specialised in and completed by a single firm in contradistinction with the methods of parts manufactured for the small standardisable machines… Horse-power 600 minimum. The design of the battleplane is largely experimental. Some constructors are ‘banking’ on the employment of three or more power plants. In these cases the standard 200-horse power engine can be employed.

“For the rapid development of this type of warplane I personally favour the immediate production of a higher power unit (i.e. 450-horse power). As all practical designs permit the use of two or three power units I would propose for the

duration of this war not to standardise an engine over 450-horse power.”

In a later chapter he went into greater detail on two types that would need to be built – an outline of designs that were already complete or under construction at Woolston.

“A fleet of defending aeroplanes is necessary. Each machine must be so armed as to be capable of destroying an airship at a range equal to the range of its own searchlight, which must be not less than one mile. It must also carry a searchlight driven independently of the engines. It must have at least a speed of 80 miles an hour in order to overtake airships. It must be able to fly as slowly as 35 miles an hour in order to economise fuel and to render accurate gunfire and night landing possible. It must be able to carry fuel for 12 hours’ cruising at low speed, to enable it to chase an airship to the coast.

“It must be able to climb to 10,000 feet in not more than 20 minutes. It must be fitted with control-gear for two pilots, to allow one to relieve the other, and in the event of a gunner not being carried, each or either pilot must have equal facilities for working guns, bombs, and searchlight. The engines must be silenced. The pilots must have a clear view and arc of fire above, in front and below. The pilots must have a clear view and arc of fire above, in front and below.

“In addition to these machines each squadron of five patrol machines should have attached to it five high-speed ‘pusher’ fighting machines to act as ‘destroyers’ against the heavier-than-the-air machine. These must have a speed of at least 115 miles per hour, with a climbing rate of 10,000ft in not more than twelve minutes. (As a technical detail of prime importance they must have engines capable of carburettor adjustment to suit variations in atmospheric conditions at varying altitudes, and be very lightly loaded to enable them to retain their speed in a rarefied atmosphere.) They must be single seaters armed with a machine-gun firing explosive bullets. Vital parts must be armoured.”

There was nothing exceptional about Billing’s description of types A, B and C, they were aircraft types already in service or under development elsewhere, but type D was a fight of fantasy. Many self-proclaimed visionaries have made similar proposals over the years – the idea of a massive gunship having considerable appeal – but the practicality of carrying aloft a 5in gun, or similar, and dealing with the stresses and loads imposed when firing it was almost always underestimated or ignored. His notion of two ‘defending’ types had some merit, however.

The Early Years Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers 7

Aerial Attack –the Zeppelin

It is well documented that the political, technical, and to a lesser extent social, changes in the late 19th century converged to create a climate of fear and suspicion that led inexorably to the outbreak of the First World War. By the dawn of the new century it was broadly accepted that war was all but inevitable – it was just a matter of time. The advent of balloons and dirigibles, with the prospect of heavier-then-air aircraft soon to follow, gave future warfare a new dimension and foremost among those warning of the consequences was H. G. Wells. In 1901 he wrote ‘An Experiment in Prophesy’ for the North American Review, wherein he concluded: “Everybody everywhere will be perpetually and constantly looking up, with a sense of loss and insecurity, with a vague distress of painful anticipations. By day, the victor’s aeroplanes will sweep down upon apparatus of all sorts in the adversaries’ rear and will drop explosive and incendiary matters upon them, so that no apparatus or camp or shelter will any longer be safe.”

Then, for the broader readership he wrote ‘The War in the Air’, a story of a catastrophic war that was serialised in the popular Pall Mall magazine in 1908. In the aftermath of a global war and the collapse of society a character says, in the epilogue: “There was a great fight all hereabouts one day, Teddy – up in the air. Great things bigger than fifty ’ouses, bigger than the Crystal Palace – bigger, bigger than anything, flying about up in the air and whacking at each other….”

These and other writings cemented in people’s minds the notion that any future war would draw civilians into the conflict as well as the military, with mass destruction of property and high casualties. Governments were mindful of the threat, many believing the dire predictions to be broadly correct and that the country’s ability to sustain a war would be dealt a lethal blow. There was real fear that under attack the civilian population would be driven to panic, society would collapse and the war would be lost. Equally there were those who feared that the population could rise up and overthrow the government that had failed to protect them, and

again the war would be lost. It did not matter much whether the authorities wished to protect the public or to protect the status quo, and hence themselves, a means to defend against attack would be essential. Billing probably had a foot in both of these camps.

Immediately prior to the outbreak of war it was well known that Germany was engaged in building large dirigibles, mostly of the Zeppelin type, and that the small scout-type single and two seat aircraft in service with the RFC and RNAS would be incapable of engaging them once they were in the air. On the other side, towards the end of 1914 the German high command debated on the merits of launching bombing raids on Britain, and both the Army and Navy were supportive of the idea.

Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz wrote that, “the measure of the success will lie not only in the injury which will be caused to the enemy, but also in the significant effect it will have in diminishing the enemy’s determination to prosecute the war”.

It was the lack of an effective aerial defence against raids by airships that led, in the very first weeks of the war, to the formulation of plans to hit the Zeppelin production facility and sheds at Düsseldorf, Cologne, Cuxhaven and Friedrichshafen, the disappointingly unsuccessful mission in which Billing himself had participated.

The first Zeppelin attacks against the British Isles took place on 19th January 1915. After a few aborted sorties, the first bombing of London occurred on 31st May. These raids would not prove particularly effective but exposed for all to see the country’s inability to defend itself against them.

Government policy for the defence of Britain at the outbreak of war was that it fell largely within the domain of the Admiralty, while the Army fielded the British Expeditionary Force and the RFC to fight on the continent, and overseas forces defended the Empire. The Navy patrolled the coast, Marines were available to be deployed onshore, as they had been in Belgium during the German’s advance, and they soon had an aerial force almost as effective as that of the Army. Hence it was the Admiralty that took the lead in formulating a defence against the

8 Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers 2 CHAPTER

Zeppelins along the coast and around the cities. Later this was bolstered by the RFC who took over the role inland, manning searchlights, anti-aircraft guns and airfields.

P.B.23E and P.B.25

The first element of Billing’s vision for the defence of Britain to see the light of day was not one of the four types described in his original masterplan but the high-speed ‘destroyer’ single-seat type that was intended to accompany the large patrol machine.

The P.B.23E, the ‘E’ denoting experimental, was, as Billing’s book had described, a single-seat pusher scout. The nacelle was skinned in aluminium, possibly a tentative attempt to provide a small degree of armour protection for the pilot, and set mid-gap between the biplane wings and held by fore and aft strut pairs to the centre section of the upper wing and by a single strut pair at the rear to the centre section of the lower wing. A forward pair of lower struts ran directly to the axle of the undercarriage. The four upper and two lower nacelle struts were also the only support for the wing centre section panels.

An 80hp Le Rhône rotary engine was installed at the rear of the nacelle and drove a two-blade propeller. The outer wings, straight with no sweep-

back, were set in a single bay with a large gap and no stagger. Only the lower wing had dihedral on the outer panels. The monoplane tail held twin fins and rudders and was supported by four struts running from the outer extremities of the centre sections of the top and bottom wings back to the rear spar of the tailplane at the point where the twin fins were attached. These struts were braced laterally by two wires each side that ran from the top and bottom of the rearmost wing struts down to the attachment point on the tailplane. The control surfaces are said to have been actuated via Bowden cables rather than a more conventional cable and pulley system. The aircraft was armed with a single Lewis gun firing through the nose of the nacelle, which placed the breaches low down by the pilot’s feet.

The P.B.23E was sent to Hendon for trials in September 1915 where is was given the nickname ‘Sparklet’ on account of the nacelle resembling the small metal bulbs that held the gas charge for soda syphons. The results of the flight trials do not appear to have been retained but the aircraft is believed to have been sent to the Isle of Grain, the test facility of the RNAS, before returning to Hendon, where it was still present in July 1916. At some point it had been modified with enlarged fins. Billing later claimed that it had a top speed of 120mph, which is highly

Aerial Attack – the Zeppelin Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers 9

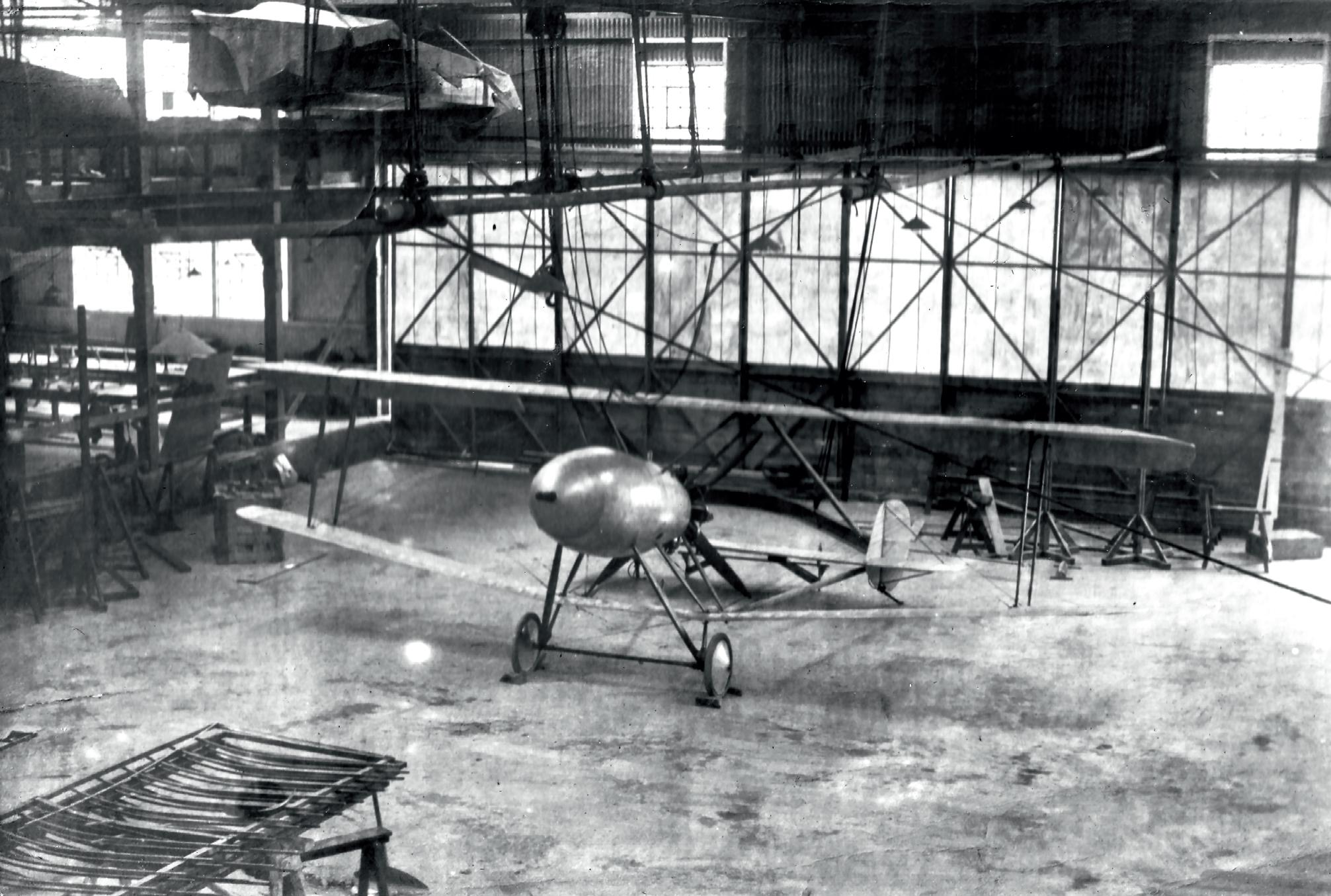

The P.B.23E, nicknamed ‘push-proj’ or Sparklet, photographed in the Pemberton-Billing works at Woolston

improbable, while a contemporary estimate was 90mph. It may have been Billing who later referred to the aircraft as ‘Push-proj’, a contraction of pusher projectile, a nickname to match his exaggerated claim for speed.

The pusher concept must have been viewed by the RNAS as having merit because they contracted the company to build 20 examples of an improved aircraft with the same layout. The P.B.25 was much more than a modified version of the P.B.23E as the entire structure had been redesigned.

The metal-clad nacelle was dropped in favour of one with fabric cover and it was both longer and deeper. The lower support struts now comprised a pair of inverted V struts to the front spar of the wing and single struts to the rear. There was no direct connection between the nacelle and the undercarriage, which was now attached to the lower wing centre section only. The greater depth of the nacelle created space for the Lewis gun in a more convenient position ahead of the windscreen lying within a trough while the increase in length placed the engine to the rear of the wings so that cut-outs for the propeller were no longer required.

The engine in the first example of the aircraft was a 110hp Clerget while the others in the production batch had a 100hp Gnome Monosoupape. The Clerget drove a two-bladed propeller while for the Gnome this was replaced by a four blade type.

To improve balance, the outer wing panels were set with 11 degrees of sweep. The top wing was of slightly greater chord than the lower and the top ailerons were increased in size by adopting reverse taper. The enlarged tailplane and fins, the tailplane attachment struts and light wire bracing were all carried forward from the modified P.B.23E.

The first P.B.25s were completed and sent for flight testing in September 1916 and the entire batch of 20 had been delivered by February 1917. The pilots found that there was much to criticise. The high centre of gravity and position of the undercarriage presented a high risk of the aircraft tipping onto its nose when landing or traversing rough ground, and the pilot was in a very exposed and poorly protected position should this occur. The aircraft was distinctly unstable in flight too.

The use of Bowden cables for the tail controls may have simplified the difficult problem of running

Chapter 2 10 Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers

The P.B.23E and artwork of the P.B.25 from a Supermarine brochure issued in 1919

cables between the mid-set nacelle, down to the lower wing and across to the tail, while avoiding the arc of the propeller, but it gave a very imprecise movement of the surfaces, initial movement of the stick often resulted in no effect while moving just a tad more would cause a sudden coarse jerk of the elevators. The rudder was similarly less precise but not to the same extent. The airframe was judged as rather flimsy, the tailplane bracing in particular lacking rigidity.

Performance was not acceptable and way below the basic specification that Billing had outlined. Top speed was 89mph at ground level, 83.5mph at 10,000ft. It took 11 minutes to climb to 6,000ft and 21 minutes to reach 10,000ft, the height at which it was intended to operate. By the time it had been constructed conventional aircraft types such as the Sopwith Pup had proven superior. The P.B.25 does not appear to have entered service.

Zeppelin destroyer – the P.B.29E

While the P.B.25 was part of Billing’s defence masterplan it was intended to play second fiddle to the larger aircraft designed specifically to intercept and destroy marauding dirigibles. Billing claimed that he had been summoned by Commodore Murray Sueter at the Admiralty, given indefinite leave from his duties and instructed to design and build such an aircraft. This is almost certainly an exaggeration or even untrue as other aircraft designed for much the same purpose were already being built by Vickers and Armstrong-Whitworth, among others. Regardless of Billing’s narrative no order for the aircraft was ever issued by the Admiralty and it was never allocated an official serial number.

Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers 11

6 0 10ft

Aerial Attack – the Zeppelin

Fig

The P.B.25 was based on the concept of the P.B.23E but with numerous improvements

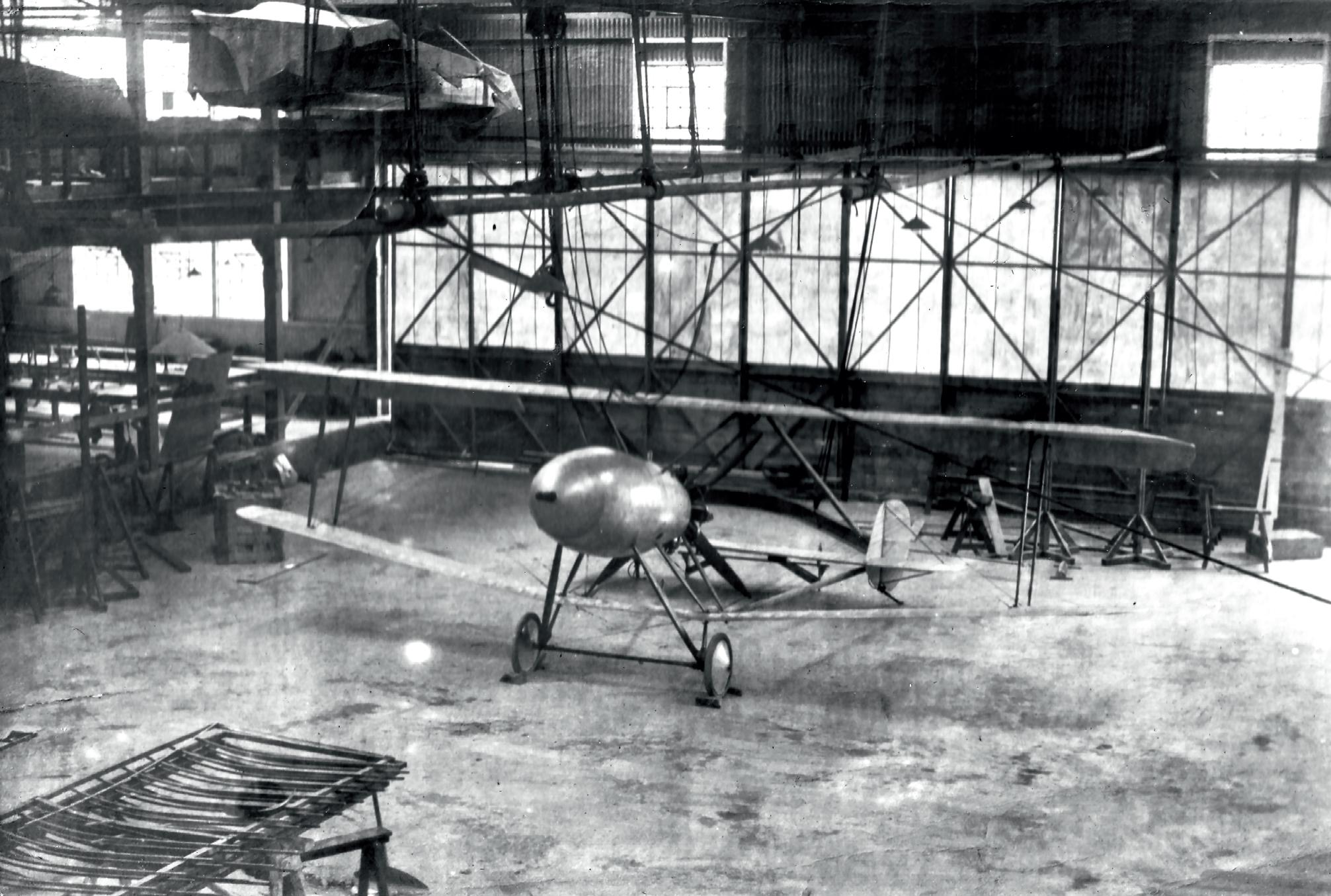

The PB.25 in the works at Woolston

The type of aircraft that Billing had described was not excessively demanding for a competent aircraft designer. A twin-engine, two-seat aircraft with a speed range of 35 to 80mph, and capable of reaching 10,000ft in 20 minutes was certainly well within the bounds of plausibility. Even the provision of a searchlight, long-range gun and fuel sufficient for a 12 hour cruise was not unreasonable. However Billing was to prove incapable of translating this vision into a viable aircraft. His company still lacked a competent trained designer; the Rumanian Carol Vasilesco, who held the role of chief draughtsman in 1914 and who may have been responsible for the detailed design of the P.B.9 based on Billing’s sketches, had died in early 1915

and it was some months before a replacement was found – Cecil Richardson taking over as the head of the small draughting department later that year.

The company did not have a designated chief designer until the beginning of 1916 when William Hargreaves was recruited; he came straight from completion of an apprenticeship in engineering but had no prior experience of the aircraft industry. It was within this void in 1915 that the P.B.23E and P.B.25 had been designed, and also the initial work on the new ‘destroyer’, the P.B.29E.

Surviving layout drawings of the P.B.29E show side elevation and plan only and are dated November and December 1915. These do not show the aircraft exactly as it was built, much like the

Chapter 2 12 Supermarine Secret Projects Volume 2 – Fighters & Bombers

Fig 8 0 10ft

The P.B.29E – Pemberton-Billing’s concept of a Zeppelin destroyer