Design: Burda Druck India Pvt. Ltd.

Publisher: Steve O’Hara

Published by: Mortons Media Group Ltd, Media Centre, Morton Way, Horncastle, Lincolnshire LN9 6JR

Tel. 01507 529529

Printed by: William Gibbons and Sons, Wolverhampton

ISBN: 978-1-911639-94-7

© 2022 Mortons Media Group Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage retrieval system without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Locating information relating to inter-war aircraft projects is proving to be both a rewarding and intensely frustrating endeavour, often in equal measure. On the one hand I have been astounded at the amount of original drawings, brochures, reports and data, in various forms, that are still out there in the world, unseen and ignored for many years just waiting to be unearthed, while on the other hand some of these material turn up in the most unlikely of places, making tracking it down a challenge to say the least.

In the past I have, on occasion, raised an eyebrow at the errors and omissions in many older books on aviation history, but given that the only aids available to these authors were the telephone, the writing of letters, a few helpful librarians and the memories of cooperative individuals, I take a different view now.

The advent of digital resources and the internet has turned research on its head. Paper ledgers and card indexes have been replaced by their digital equivalent in a great many libraries, archives and collections, with many then placed on their websites in searchable form. Who would begrudge a small fee for access and copies if you know what it is you will receive? This is all most welcome and those that have chosen not to do so, and there are many that should know better or are unaware of the benefits both to themselves and researchers, are encouraged to follow suit. There is still a great deal of material yet to see the light of day in many collections; properly catalogued and accessible you have an archive, without it you have a hoard.

The National Archive at Kew and the Department of Research and Information Services at the RAF Museum Hendon are a goldmine of original material but unexpected nuggets can be, and have been, tracked down at numerous museums and libraries around the world to fill gaps in the narrative. Mention should also be made of online antiquarian booksellers and auction site sellers, a further great resource, if a bit pricey at times. The internet also brings with it the ability to dialogue with other researchers, authors and enthusiasts to share information. Questions can be answered in minutes that a few decades ago would have taken weeks.

So, I would like to acknowledge the assistance I have received from the staff at the RAF Museum Hendon, my volunteer colleagues with the Royal Aero Club Trust, fellow authors Tony Buttler and Chris Gibson, and knowledgeable contacts Chris Michell, Dave Key, and many others.

Ralph PegramFlying boats hold a particular fascination for many aircraft enthusiasts in a way that no other type seems to manage. For some reason they conjure up an image of romance and adventure often quite out of step with the roles for which they were designed, and as with any class of aircraft there were good ’uns and bad ’uns, and everything in between. Naturally a great many stayed firmly on the drawing board, the ‘what if’ projects that make up the majority of any designer’s portfolio.

It is distinctly ironic that Supermarine, the company responsible for the design of the Spitfire fighter, an aircraft produced in far larger numbers than any other in Britain, was a business that had been launched with the specific intent to build flying boats. For many years expectations were high that there was a lucrative global market just around the corner for such types, both civil and military, yet it would turn out that flying boats were to represent well under 1% of total British aircraft production. On the positive side, around half of these flying boats were designed by Supermarine but, as is so often the case for aircraft companies, the majority of its projects were destined never to see the light of day.

For the purposes of this review of Supermarine’s flying boat designs, the term ‘secret project’ will encompass not just those unfulfilled ’paper’ projects, of which many were submitted as brochures and unsuccessful tenders to airlines and the military, but also those that were stepping stones on the way to the design of aircraft that the company actually did construct. Among these are a number of ‘one-off’ prototypes built with high expectation for sales and spin-off types, but which underperformed in one way or another and thwarted the company’s plans.

But before embarking on the tale of Supermarine and the flying boat, we must first define what we mean by the term ‘flying boat’ as it tends to vary through time and from country to country. In the early days in Britain there were, among other names, hydro-aeroplanes, waterplanes, seaplanes, float planes, boat seaplanes and flying-boats.

By the end of the First World War, the standard terminology used in British technical reports was to refer to marine aircraft as seaplanes when they were supported on the water by a float or floats that were separate from the main body of the aircraft, and many of these where the direct counterparts of their land plane equivalent where some form of float had been substituted for the wheeled undercarriage. When the aircraft was supported on the water by the main body of the aircraft, generally referred to as a hull, as in a boat, the term used was flying boat. Occasionally, with the intent for greater clarity, official documents would refer to float seaplanes or boat seaplanes. Supermarine produced both seaplanes and flying boats, the former including their celebrated series of racing aircraft for the Schneider Trophy, but their primary focus was always on the latter.

The name Supermarine is inextricably linked with that of the man who served as chief designer for 17 years and director for ten, Reginald Joseph Mitchell, but there are many others who contributed to the success, and a reasonable number of failures, of the company. So, to start, we have to look at the founder of the company and the direction he intended for it to take.

Noel Pemberton Billing

The years immediately prior to the outbreak of the First World War saw the establishment in Britain of a fair number of partnerships and companies all seeking to capitalise on the anticipated demand for both civil and military aircraft. The Army and Navy had both started to take an interest in the new technology, the Army using its Balloon Factory at Farnborough as a base to support early experiments by aviation pioneers Samuel Franklin Cody and John William Dunne in 1908. The facility was renamed as the Army Aircraft Factory in 1911 and service trials of potential military aircraft were held at Larkhill in 1912. The Navy soon followed suit with an establishment on the Isle of Grain.

Several of the new aircraft companies were established as subsidiaries of, or associated with,

existing businesses, the most prominent being Vickers, Short Bros, Grahame-White, and the four companies formed by Sir George White in Bristol, while others were set up by the pioneers of flying in Britain, financed, in the main, by wealthy family members or friends. This route was taken by Blackburn, Verdon Roe, Handley Page and others. One who would have loved dearly to have been in this latter group was Noel Pemberton Billing.

It is hard to grasp what exactly Billing was aiming to achieve in life. Overwhelmed with selfconfidence and a distinct tendency to exaggerate or even veer towards fantasy, yet possessing a fair degree of inventive imagination, he had made a reasonably comfortable living through a variety of jobs, both in England and South Africa, and by marketing the rights to the various patents he held, the most profitable being for a form of typewriter. On the other hand he was also arrogant, tempestuous, prone to be combative and, unfortunately, easily distracted, lacking tenacity and always on the lookout for the next new venture rather than knuckling down to nurture the one in hand. And so, in late 1908, for reasons none too clear, he determined to enter the world of aviation, not content to be just one of the growing cadre of pioneers but to create for himself a role as a leader and facilitator.

It has to be said that Billing never thought small, not for him the graft of working his way up from the bottom, so his master plan was to establish a “Colony of British Aerocraft” with himself in the forefront. A trusty band of likeminded aircraft builders would beaver away to establish of a fleet of aircraft, which he intended to call the “Imperial Flying Squadron”.

He published a new magazine, also named Aerocraft, to help publicise the venture and as a base for the ‘colony’ he purchased 3,000 acres of wet reclaimed land crossed by numerous drainage ditches at South Fambridge in Essex, adjacent to the tidal stretch of the River Crouch. On this site there were several useful buildings; large workshops formerly used by an engineering concern, a few bungalows, a hotel and club house, a general store and an electricity plant. Billing saw this as a viable base for his venture, everything that would be required for the colony was already in place. It was a grand plan which he hoped would attract many pioneer aviators, and to further advertise the opportunity he managed to get it described in a Flight magazine feature.

The colony was not to be, however. Many of the more prominent and successful pioneers, the Short brothers, Dunne, Charles Rolls and several others, preferred to base themselves at the Aero Club’s

grounds at Shellbeach and later nearby Eastchurch, where the airfields were firmer and not liable to flood. Billing’s venture folded within a year and South Fambridge had to be abandoned. Billing’s own attempts to build and fly an aircraft had also failed, the result being a few brief hops and a crash that put him in hospital. He now lost interest in aviation, or “relaxed his efforts”, as he was to put it later, took up property speculation at Shoreham on the south coast and enrolled to study law. In 1912 he had shifted focus yet again and set up a new venture running a yacht charter business on the River Itchen in Southampton.

What goes around comes around and once the charter business was up and running in the capable hands of his assistant, Hubert Scott-Paine, his mind wandered and returned again to aircraft. On a visit to Grahame-White’s burgeoning flying ground at Hendon in 1913 he got into an argument with pioneer aircraft constructor Fred Handley Page over how easy it would be to learn to fly. Handley Page claimed that his latest aircraft was so stable that anyone could learn to fly on it within a day. Billing scoffed, countering that a competent person could do that on any machine, and a bet was made as to who would be the first to earn their aviator’s certificate.

Heading to Brooklands race circuit and airfield, where his brother ran a restaurant, Billing purchased a Farman biplane and at the crack of dawn engaged the services of Harold Barnwell from the Vickers School to teach him the rudiments of flying. By breakfast time, after little more than a couple of hours training, he decided that he was prepared sufficiently and cajoled the Aero Club examiner to observe his test flights. These he completed and was duly awarded his certificate, the story reported, once again, in Flight. Handley Page, who had yet to even start, paid up.

Billing was now officially an aviator and determined to make a second attempt to join the pioneers. This time he would become a constructor of aircraft and spotting, or possibly being urged to address, a niche that had yet to be filled, he decided to concentrate on marine types. He submitted patent applications for various inventions associated with flying boats. Across the Itchen from his yacht charter business, at Oak Bank wharf in Woolston, there was a ship’s chandler and gravel merchant business that had fallen into receivership. Billing acquired their site on which there were a couple of large sheds, a wharf, several lesser buildings and a small tidal basin. Here he established Pemberton-Billing Ltd.

Pemberton-Billing Ltd.

Billing’s new business began to take shape over the winter of 1913-1914. The sheds were repaired

and extended and named as the Supermarine Works. Construction of the first Pemberton-Billing aircraft, a small single-seat flying boat named as the Supermarine P.B.1, began there at once. Billing produced a souvenir silk-bound brochure to publicise the start-up in which he itemised his grandiose plans: three types of built to order flying boat, a school to teach the subtleties of flying from the water, a tidal dock capable of housing up to 12 flying boats, and an Aerial Marine Navigation passenger service flying to and from the Isle of Wight. The sketch artwork within the brochure gave a grossly exaggerated idea of the size of the site and facilities, a fine match for the equally fanciful text.

The name ‘Supermarine’, which Billing had applied first to the works and then to the aircraft he intended to build, had been conjured up by him “… to convey to the mind a craft capable of navigating the surface of the sea as also the air… (his) ultimate object was directed not to the production of a flying machine which under favourable weather conditions could rest on the surface of the water, but to the construction of a sea-worthy boat capable of attaining flight…”

The Supermarine P.B.1 was completed, albeit without an engine, in time to be displayed at the Aero and Marine Exhibition held at Olympia in London during March 1914. Unfortunately, when prepared for flight testing in the early summer, it failed to lift from the water even after a radical modification. It is hard to judge whether there were any fundamental flaws in the design – it certainly appeared sound – but it was definitely underpowered as the only available engine was Billing’s aging 50hp Gnome rotary, plundered from his Farman biplane.

Neither the P.B.2 nor P.B.3, larger flying boats described in the brochure, ever materialised but a completely new and unrelated design, P.B.7, which incorporated Billing’s patented ‘slip-wing’ system, was the subject of advertisements in the aviation press in July. Two were reported to be under construction for the German military. The ‘slip-wing’, a term coined by Billing years later, was a system whereby all the aircraft’s flight surfaces could be detached from the hull by a quick release mechanism thereby allowing it to function as a conventional motor launch.

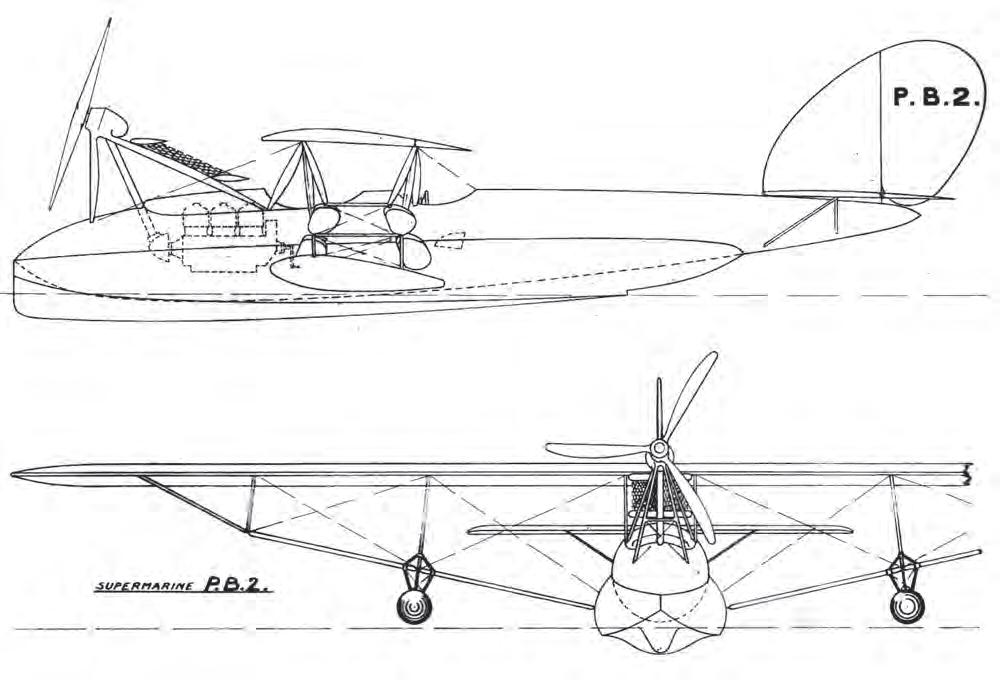

Side and front views of the Supermarine P.B.2 from the brochure

Flying boat construction, what little of it there was, came to an abrupt halt with the outbreak of war and Billing rushed off to join the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). Desperately short of funds, the factory was left in the lands of Scott-Paine. Billing participated in the raids on the Zeppelin factories at Friedrichshafen on the shores of Lake Constance in late 1914 but his military career was cut short when he resigned his commission at the end of 1915.

He returned to Woolston to develop his ideas on defensive and offensive aircraft but by now his zeal for the business was on the wane and he had determined to enter Parliament. His campaign was based on the notion that the whole war in the air was mismanaged; politically, technically and strategically. After fighting one by-election unsuccessfully he was elected at his second attempt and entered parliament as the member

Pemberton-Billing advertisement for the ‘slip-wing’ P.B.7. July 1914

for Hertford East. He also published his views in a book, Air War: How To Wage It, and sold out his part-ownership of Pemberton-Billing Ltd to Scott-Paine in order to avoid any accusation of a conflict of interest. His Parliamentary career was

controversial to say the least and he lost his seat at the first full post-war general election in 1921. Thankfully he was to play no further part in the future of the aircraft manufacturing company he had established.