8 minute read

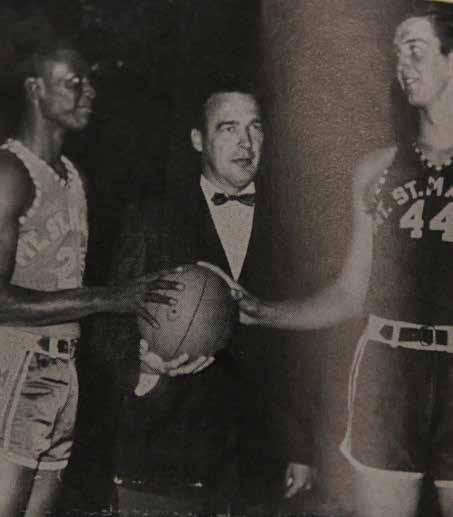

FRED CARTER, C'69, AND COACH JIM PHELAN

God's Plan How Coach Jim Phelan found Fred Carter, C’69, and made Mount history

By Joe Paciella, C’03, MBA’11

COACH JIM PHELAN HAS RECRUITED hundreds of studentathletes during his 49-year career as head coach of the Mount St. Mary’s men’s basketball program. Of them, Fred Carter, C’69, may have been the most significant. Carter came to Emmitsburg in 1965, becoming the first African American student to live on campus, later graduating with a bachelor’s degree in education. This past summer, 50 years since his last game in 1969, Carter paid Coach Phelan and his wife Dottie a visit to reconnect and share their stories about that time in Mount history. “I don’t think the school knows and understands what he did. Because his whole livelihood, reputation and life was on the line,” reflects Carter. “They took a heck of a gamble and it opened the doors to all the black students to come here.” Growing up in Philadelphia, Carter’s work ethic took shape spending time with his father and watching his mother. “Father was a junk man, ok, discarded waste collector. We were Sanford and Son before there was a Sanford and Son.” The duo would wake up early, scouring the city for scrap metal, which they would separate into piles and later sell. His mother worked seven days a week, sometimes at two jobs to make sure Carter and his five siblings were taken care of. But when his father passed away, a young Carter became aimless and dropped out of high school. Fortunately, his mother recognized the situation and stepped in. “And my mom said to me, and I remember her words, she said, ‘Son, you’re making steps but going nowhere,’” Carter recalls. “And from that point on, it changed my life.”

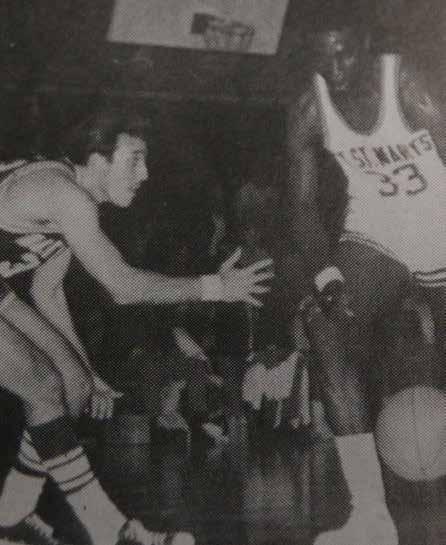

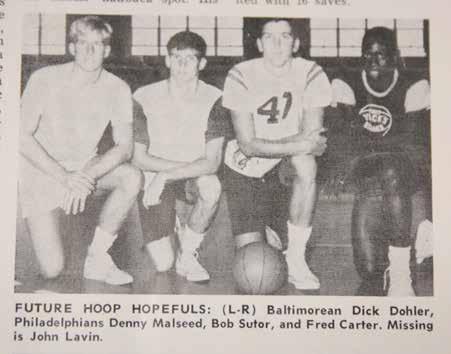

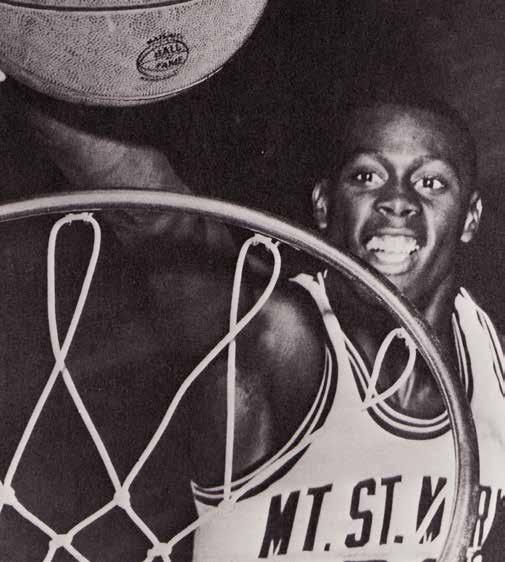

It was then that he decided to take the initiative to earn his high school diploma, going day and night to two different schools. He also continued to play basketball, but despite his athleticism, wasn’t heavily recruited by any of the nearby colleges. After graduation, he intended on enrolling in what’s now known as Cheyney University of Pennsylvania since his girlfriend was going there. Carter now sees there was more at work. “When you look back on life, you recognize all the things that God has done. You can’t see it while He’s doing it. But after it’s done you recognize it. You can’t see His works as He’s doing it. And I know that for some reason God had a plan. Because He brought us together.” Coach Phelan and Buddy Donnelly–a teammate of his at LaSalle– went to Philadelphia on a recruiting trip to see a game with future college standout and NBA player John Baum, who ultimately chose Temple. Carter was playing in this game as well. “Fred’s reputation was that he was not a good student,” recalls Coach Phelan. “Hardly anybody knew that he had finished his high school requirements.” After a brief discussion with Baum, the pair left the game and about a block and a half away, Coach Phelan asked Donnelly if he’d like to go back to talk to Carter. As they approached the court, Carter, taking a break, was smoking a cigarette. “That’s when I noticed his hand quickness,” says Coach Phelan. “He had the cigarette in his hand and put it against his hand and tucked it in his pocket. I said to Buddy, ‘I know he has good hands.’” Coach Phelan later returned to Philadelphia to pick up Carter for his first visit to the Mount. As their drive took them out of the city and eventually into rolling farmland, their conversation turned to the composition of the student body. When Carter asked Coach Phelan how many African American students lived on campus, he simply replied, “Look in the mirror and that’s the only one you’ll see.” It didn’t take long after he arrived at the Mount for Carter to experience adversity, as presented on his first road trip to Randolph-Macon during his freshman year. After a stellar first half, which gave the Mount the lead going into the break, the team headed to the locker room. Suddenly, three men came out of the stands and jumped Carter, hitting him in the back of the head. Thankfully, his teammates came to his defense, led by 6’9” Mount Athletics Hall of Famer Bobby Sutor, C’69. While there were challenges for Carter on the road, things weren’t always easy at the Mount either. Even though he was featured as a “frosh stand-out” in the 1966 Pridwin yearbook and had many friends and supporters when they were winning, once the season was over, many of those same people didn’t speak to him. “So I called my mom one day and I said, ‘Mom, I want to come home. I just want to come home, I can’t do it here,’” admits Carter. “And my mother said to me, ‘Son, do it for me.’ And that changed my whole being, my whole sense of thought.” Staying at the Mount with a renewed focus, Carter began to develop as a player, thanks to Coach Phelan’s mentorship. “I don’t know whether I ever really thought that I could be a pro player, because I didn’t know how good I was,” Carter says earnestly. “But because of the teaching that I got from Coach, I learned how to play the game

of basketball…But he taught me also the mental toughness of playing the game and being ready and prepared…Coach taught me how to play the game both physically and mentally.” Off the court, the Phelans, whom Carter referred to as his “anchor,” were also instrumental in helping him grow as a person. They aided the young student in navigating the transition to college life in a new town with the added pressure brought about by the racial tension of the time. They shared meals together and introduced him to members of the Emmitsburg community, who also stood by his side (and even baked him the occasional cake). Carter’s faith—something he says his mother helped him develop—is evident when he talks about the time he spent with the Phelans. “God uses who he chooses. And He chose Coach to find me, to bring me here, to Mount St. Mary’s, and He watched over us as a group.” With a career average of 21.9 points per game, Carter’s mark is still the second-best total in Mount history behind only Jack Sullivan, C’57, the Mount’s all-time leading scorer. He’s also fifth on the Mount’s all-time rebounds per game list at 10.8 –lofty enough figures to have his number 33 jersey retired, displayed right next to Sullivan’s above Jim Phelan Court. Soon after his Mount career ended, Carter was selected by the Baltimore Bullets in the third round of the NBA draft, and played eight seasons as a pro, later going into coaching and then television as an analyst for ESPN. Worth noting is the NBA Carter played in looked much different than the league of today. Only 14 teams existed in 1969, as opposed to the current total of 30, so talent was much more concentrated. “Wilt Chamberlain, Dr. J.–I had to play against them every single night,” Carter recounts. And it didn’t stop there. Other NBA legends he suited up against included Kareem AbdulJabbar, Walt Frazier, Dave Bing, Pete Maravich, Oscar Robertson, John Havlicek, Jo Jo White and Jerry West– whose silhouette is used in the NBA’s logo. It should also be pointed out that during this time Carter began to use the “fist bump” on a regular basis, making the handshake alternative more popular. (Some even credit him as its inventor, but it’s been documented that the fist bump was around before his days in the NBA.) While he has many memories of his playing days, the highlight of Carter’s professional career may in fact be his late-game jump shot to win game 7 of the 1971 Eastern Conference Finals in Madison Square Garden against the New York Knicks. “When I came here at the Mount, I couldn’t shoot the basketball,” explains Carter. “Coach taught me how to shoot… And it’s all because of the foundation which I grew from. And it didn’t come just from happenstance or chance, because I had a great, bona fide coach and teacher.” A plaque at the Philadelphia Palestra, the legendary arena in Carter’s hometown, known as the “Cathedral of College Basketball” for its importance to the sport, reads: “To win the game is great… To play the game is greater… But to love the game is the greatest of all.”

It’s this love of the game that Carter sees missing from some of today’s players. “I question the love of the game of basketball,” he says. “I don’t know whether they love the game of basketball. I mean, Coach grew up and I grew up, we’re in the playgrounds playing with holes in our sneakers, sweep the water or the snow off the court and play. I don’t think that today’s kids have the love of the game as we had it.” While his effort, determination and love of the game enabled him to achieve great success in his career, he wants others to know that his foundation, not only as player but as a person, was built by Coach Phelan. “And I can’t say enough of what he’s done for Mount St. Mary’s,” emphasizes Carter. “And at some point, I’d like for it to be acknowledged and recognized, not just a basketball coach–that’s fine, that’s a wonderful part of his life. Great coach, wonderful man, but he’s a humanitarian, a good man, and he did that.” Ultimately, Carter would like to see the legacy of Coach Phelan remembered by the larger impact he made on the university and society in general. “I didn’t integrate Mount St. Mary’s, he did,” Carter states directly. “Because when Coach brought me there, that’s a tremendous gamble. Because if I fail, it all falls on him...and praise be to God, that God gave me the strength to get through it, it wasn’t just Fred Carter…but if I fail, it’s 10 years before that happens again. So, great coach, great father, great husband. But a great humanitarian, that they don’t talk about.”

Hear more!

Listen to Fred Carter and Coach Phelan on the Live Significantly Podcast hosted by President Timothy E. Trainor, Ph.D., at msmary.edu/podcast.