7 minute read

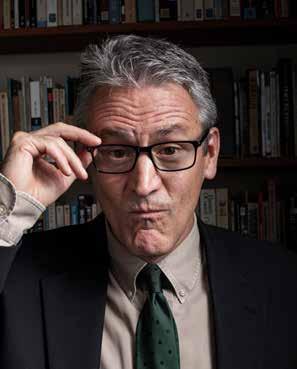

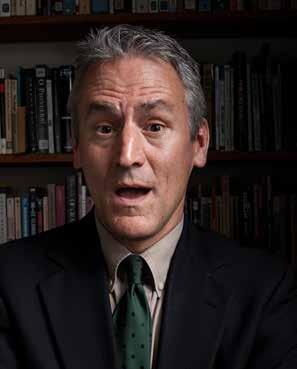

DAVID WEHNER, PH.D

David Wehner, Ph.D. A Stand-Up Professor

By Peter Dorsey, Ph.D.

WHEN MOUNT ENGLISH PROFESSOR DAVID WEHNER, PH.D., graduated from Williams College in 1985, his classmates went off to become doctors, lawyers and investment bankers. He thought, “Comedian; yeah, that would be fun.” At a party two years before, he overheard future Hollywood star Don Cheadle mention he performed on amateur night at a local comedy club. “I turned to Don incredulously,” Wehner recalled, “‘You mean, I could go up on amateur night?’ ‘Yes’ Don answered, and two weeks later, I was on stage.” Wehner didn’t know that he was graduating into an unprecedented comedy boom. In 1980, 20 full-time comedy clubs existed in America; by 1985, there were 200. After college, he returned to the Comedy Works in his home city of Denver—the club where Roseanne Barr got her start—and began by tearing tickets at the front door, performing on amateur nights, and observing as much comedy as he could. In nine months, he began to do stand-up full time and continued for six years. Wehner then became a high school English teacher before going on to earn his doctorate from the University of Minnesota. At Minnesota, he taught an early version of a class on stand-up comedy that has evolved at the Mount into The History, Poetics and Politics of American Stand-Up Comedy.

Kaitlyn Heintzelman, C'19

As the title suggests, Wehner organized the course into three units. The first covered the history of stand-up comedy, decade by decade, from Mark Twain to the present. For example, for the 1930s students studied the radio comedy of George Burns and Gracie Allen, and for the 1960s they studied the album comedy of Bob Newhart. “One of Bob Newhart’s albums,” Wehner says, “actually was number one on the Billboard album charts.” Covering more recent history, Wehner taught students the hierarchy of signals Johnny Carson applied to the performances of comedians who appeared on “The Tonight Show” from quick brush offs to the rare but highly prized invitation to sit on his couch. Wehner associated his own work with the observational comedy which emerged in the 1970s, best known in the work of Jerry Seinfeld. Here “the focus shifted from telling mother-in-law jokes to really commenting on life,” Wehner says. The second course unit, “the poetics of comedy,” addressed the craft of writing a joke and structuring a comedy act. In this section, Wehner taught the rule of the “K” sound. Comedians find that words with the K sound draw more laughs. Comics tell the story of a comedian who performed on “The Tonight Show” and had a punchline about driving a Ford. During the commercial break, Johnny Carson leaned over and simply said, “Say Buick; Buick is funnier than Ford.” That is, Buick follows the rule of the K sound, Ford doesn’t. Theorizing further, Wehner tells students that understanding the 44 phonemes used in English can enhance the comedic effect. Punchlines using phonemes enunciated in the front of the mouth tend to go over as funnier than sounds enunciated in the back of the mouth. Wehner asked his students to apply this principle by discovering five good comedic words and five bad ones. Wehner recalls, "I have sensed some of my fellow professors are skeptical about the connection between stand-up comedy and literary studies. But there is a lot of crossover between the two. Both are linguistic arts: one oral, one written. When we study poetry, for example, we pay attention to the sound of words and the ways they are organized. The same is true of comedians.” If a literature class is studying the sonnet form, the professor will often ask students to write a sonnet so that they can understand the art form from the inside out. When Wehner assigned oral reports in his comedy class, students had to begin their presentations with a joke. “Most of them gave very short jokes,” Wehner reflects, “but I was hoping that they would give more narrative-oriented jokes because I wanted them to struggle with the form as a way of understanding.”

The final unit of the course examined the “politics of comedy,” a topic that runs throughout the history of comedy. One question that arises in studying comedy is why is the profession so male dominated. “In law and medicine,” Wehner states, “there were systemic barriers that kept women out of the profession. There’s nothing systemic in comedy. Yet it tends to be male-dominated. There are plenty of funny female comedians today, but the profession is still about 80% men.” Wehner also tells students that women breaking into comedy in the 1970s such as Joan Rivers often emphasized their unattractiveness as a source of their comedy. “Only since about 2000,” Wehner observes, “have female comedians been comfortable enough to not make apologies for how they looked. But the stereotype and the cultural expectations linger.” One theory holds that stand-up comedy originated from two sources: vaudeville and burlesque. In such settings, Wehner explains, “the men were supposed to be funny and the women were supposed to look good—so it could be a result of cultural conditioning.” Another political dimension to comedy is the tendency for comedians to purposely go after topics that many will not find funny. Wehner says, “They talk about things that are not generally the topics of polite conversation.” Sarah Silverman, for example, has a routine where she jokes about 9/11, Christianity, being Jewish, and harvesting babies for their tailbones. "Comedians," Wehner explains "frequently step close to landmines. By the time you get to 1975 with George Carlin and Richard Pryor, everything is fair game in comedy." This concerned Wehner, so he asked his department chair, Indrani Mitra, Ph.D., about it. She wondered whether you could do a PG version of a comedy course. “I didn’t really want to do that,” Wehner says, “because that’s not what comedy is like. It turns out I was more squeamish about such things than the students were.” When planning the course, Wehner also worried about sustaining a full semester studying comedy. Wehner says, “The author E.B. White said dissecting humor is like dissecting a frog: you can do it, but you usually kill it in the process.” Happily, the frog emerged croaking: students roundly enjoyed and appreciated Wehner’s class. Shea Rowell, C'19, an English and music major, says the “class expanded my notion of what literature can be.” Fellow English major Kaitlyn Heintzelman,

C'19, reflects, “Dr. Wehner’s comedy class was unlike any other class I encountered at the Mount. We laughed a lot, but the jokes we analyzed provoked serious discussions about politics and society.” Wehner believes doing stand-up prepared him to be an effective professor. He compares doing multiple shows during the week and multiple routines on any given night with a university teaching schedule. “Performing is like teaching three sections of the same class on the same day. You have your lesson plan, but each class is different. If something works in an earlier class, you can incorporate that into the next class. When I was a comedian, I would have a set list, and I would take notes on each set. If I ad-libbed something that worked, I would write that down. If I tried something that fell flat, I would note that too. I do the same thing when I teach.” He also says that doing comedy taught him how to read a crowd and how to respond to an audience. “When I start to bomb,” Wehner states, “I know how to switch gears. Stand-up teaches you how to do that.” Reflecting on his life on the road, Wehner recalls an evening in Albuquerque, New Mexico, when he was the opening act for Jerry Seinfeld. Between sets, he and Jerry chatted, and Wehner found him to be friendly. A tradition exists in the world of comedy of comedians going out to get an early breakfast after the second set. So when they had finished, Wehner asked Jerry, “Would you like to go grab some breakfast?” Jerry asked, “With you?” Wehner replied, “Well— yeah.” Wehner explained, “Jerry then looked at me and said ‘No.’ So I slowly walked away... but that’s Jerry Seinfeld: honest to a T.” Luckily for the Mount, Jerry wasn’t too hungry that night.

Learn more!

Read about Wehner's impact on Mount students at msmary.edu/2019fulbrights.