ALPINER EXTREME AUTOMATIC FREERIDE WORLD TOUR

THE ORIGINAL SPORTS WATCH SINCE 1883

ALPINER EXTREME AUTOMATIC FREERIDE WORLD TOUR

THE ORIGINAL SPORTS WATCH SINCE 1883

Glide between skins, scrambles and descents with all-new Firn ski mountaineering packs. Snow-specific organization and an ultra-stable vest-style harness support any winter mission, while an innovative ski lasso carrying system lets you stow your skis without taking off the pack—keeping you on the move for uninterrupted flow.

15%OFF

Save 15% after the slopes with any 2024-2025 Whistler Blackcomb Mountain ticket or pass.

P.27 IN AN INSTANT The Battle to Heal a Brain

P.32 GRINGA'S FUND Legacy of a Good Dog

P.16 NORTHERN EXPOSURE Kari Medig Hits the Road

P.50 TOMORROW IS THE NEW YESTERDAY The State of Snowboarding

P.30 BEHIND THE PHOTO Meanwhile, in Squamish

P.36 MOUNTAIN LIFER Al Crawford

P.59 BACKYARD Sea To Sky Weather Ops

P.78 GALLERY Cream of the Crop

Mountain Life Coast Mountains operates within and shares stories primarily set upon the unceded territories of two distinct Nations—the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh and the Lilwat7úl. We honour and celebrate their history, land, culture and language.

PUBLISHERS

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

EDITOR

Feet Banks feetbanks@mountainlifemedia.ca

CREATIVE & PRODUCTION DIRECTOR, DESIGNER

Amélie Légaré amelie@mountainlifemedia.ca

MANAGING EDITOR

Kristin Schnelten kristin@mountainlifemedia.ca

WEB EDITOR

Ned Morgan ned@mountainlifemedia.ca

DIRECTOR OF MARKETING, DIGITAL & SOCIAL

Noémie-Capucine Quessy noemie@mountainlifemedia.ca

FINANCIAL CONTROLLER

Krista Currie krista@mountainlifemedia.ca

CONTRIBUTORS

Andrew Bradley, Erik Boomer, Jessy Braidwood, Kieran Brownie, Mary-Jane Castor, Tony Carroll, Chris Christie, Andy Dittrich, Josh Dooley, Michael Fox, Gepa, Ben Girardi, Laura Goodwin, KaraLeah Grant, Grant Gunderson, Erin Hogue, Lani Imre, Blake Jorgenson, Justa Jeskova, Justin Kious, Carmen Kuntz, Jesse Lirola, Taylor Loughran, Stu MacKay-Smith, Jordan Manley, Jimmy Martinello, Andrew McAloon, Kari Medig, Emily Nilsen, Alex Pashley, Dano Pendygrasse, Bronwyn Preece, Jake Scharfman, Vanessa Stark, Jon Turk, Anatole Tuzlak, Pat Valade, Sarah Woods.

SALES & MARKETING

Jon Burak jon@mountainlifemedia.ca

Todd Lawson todd@mountainlifemedia.ca

Glen Harris glen@mountainlifemedia.ca

Published by Mountain Life Media, Copyright ©2025. All rights reserved. Publications Mail Agreement Number 40026703. Tel: 604 815 1900. To send feedback or for contributors guidelines email feet@mountainlifemedia.ca. Mountain Life Coast Mountains is published every February, June and November and circulated throughout Whistler and the Sea to Sky corridor from Pemberton to Vancouver. Reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. Views expressed herein are those of the author exclusively. To learn more about Mountain Life visit mountainlifemedia.ca. To distribute Mountain Life in your store please call 604 815 1900.

Mountain Life is printed on paper that is Forest Stewardship Council ® (FSC ®) certified. FSC ® is an international, membership-based, non-profit organization that supports environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the world’s forests. Mountain Life is PrintReleaf certified. It measures paper consumption over time automatically reforested at planting sites in Canada.

People who don’t live in the mountains are often telling those of us who do that we live in a bubble, isolated from what they consider to be “the real world.” And they’re not wrong. Here in the mountains, the weather forecast plays a much bigger role in our lives than the 6 o’clock news.

And that’s the way we like it. A bubble is its own little universe, a contained cosmic swirl of ideas, shared passions and people who do things a little bit differently, who explore and interact with the world and each other in ways that aren’t limited or controlled by rules or tradition. People who lean into the storm and step off the beaten path just to see what happens.

It isn’t for everyone, but for those of us drawn to this mountain life, inside the bubble is where the magic is, because inside the bubble is outside the box.

There’s this famous puzzle from the last century, nine dots that make up a square. And the idea, the challenge, is to connect all nine dots using only four straight lines. Give it

a try. Get loose, get creative, ignore the boundaries of what your brain says you’re supposed to do. Think outside the box. Or better yet, get rid of the box all together. Welcome to the bubble. – Feet Banks

Small, cold and refreshing— the ski hills of Northern BC

photography :: Kari Medig words :: Emily Nilsen

Burned out by hour-long morning lift lines? How about ski hill parking lots packed like a tin of Tesla sardines or day tickets the price of a one-way flight to a beachside mojito? Rest assured, there’s an antidote: the great north.

Far from the uber-luxe crowds, BC’s northern interior ski scene is refreshingly unpretentious, filled with salt-of-the-earth snow sliders who love big open skies and—to aptly stereotype—really big trucks. School-bus cabins, camo hoodies and a rock-solid community feel are just a few traits that give northern ski hills their down-to-earth chops.

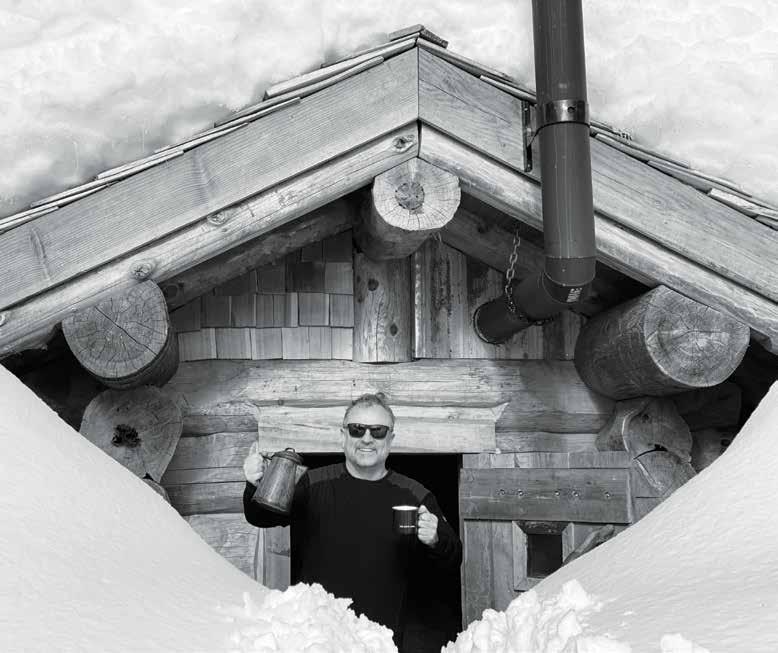

To document this ski culture, photographer Kari Medig set off on a 10-day voyage visiting seven hills of the north, an area close to Medig’s heart. Raised in a log cabin on the shores of Babine Lake, he caught the skiing bug as a kid, soloing runs on Hudson Bay Mountain near Smithers. One of his early childhood memories is of being rescued by ski patrol, after-hours and out of bounds, trembling like a little hare. Fuelled by nostalgia (and he admits, double doubles with non-alcoholic Baileys) Medig spent the bulk of the latest Christmas season going hill to hill, from Troll Ski Resort in the east to Shames Mountain in the west, tuning in to people who make these places tick.

More than half of BC lives in the lower mainland, or snug up against the southern border. To many people, the north is a faraway place where trees are logged, gas is drilled and mines are aplenty. To many more people, the north is vaguely somewhere up there. Sure, it’s remote, but to the people who live there, lack of proximity to a metropolis gives the north something many skiers long for: space.

Medig’s images celebrate the spirit of northern ski hills and offer a glimpse into worlds far from mega-resorts, where the best thing to spend is time: sliding over snow, amongst the evergreens—and occasionally in jeans.

Ryleigh Walker and David Hill, both from 100 Mile House, at the end of their ski day at Mount Timothy near Lac la Hache, BC. Ryleigh, a first-year skier, “loves the wintertime,” she says. “I love snow…it’s just calming, going back and forth.” David, a snowboarder for 15 years, on what’s unique about Timothy: “It’s nice that it's local. You don’t have a lot of people. You’re down to the bottom and you’re back on the lift in a second.”

RIGHT

The chairlift at the base of Mount Timothy, a privately owned north-facing ski hill in BC’s Cariboo region.

LEFT PAGE, CLOCKWISE STARTING TOP LEFT. 1. A stuffed caribou harvested by the mechanic at N&V Johnson Services hangs on the wall of the service station at the junction of Hwy 16 and Hwy 37. 2. Sean and Debbie Scallion share a moment in front of their 2004 International school bus, which has been converted into a temporary ski lodge at the base of Troll Ski Resort, 48 km east of Quesnel, BC. 3. Local Blake Olesiuk takes a break from the ski day on the basement couch in the lodge at Murray Ridge Ski Area overlooking Fort St. James, BC. 4. 81-year-old David Jeffery, owner of the Sunset Theatre in Wells, BC, enjoys a ski day with his daughters at Troll Ski Resort. “I’ve been happily skiing for free here the last 6 years! I’ve paid my dues. This is just a gem of a place to come to. Having skied a lot in Europe and quite a few resorts in the States, this place is to die for. Because it’s a lovely and friendly family environment.” 5. Hudson Bay Mountain Resort ski patroller Kim Preston-Thomas at the summit patrol hut in Smithers, BC. 6. Alyysha Turnbull, the activity leader at Little Mac Ski Hill, a community-operated ski area in Mackenzie, BC. ABOVE. A skier harvests some powder next to the Skyline Connector off of the summit of Hudson Bay Mountain Resort in Smithers, BC.

ABOVE. Jesse Gilbert and Tabitha Strykiwski take a cigarette break at the base of Powder King Mountain Resort on a cold ski day in January. It was their first time skiing at Powder King. Jesse, an avid skier, says she “likes how it’s secluded in the middle of the mountains. There’s not a lot around it and it’s absolutely stunning, the views.” Tabitha, a first-time skier, says, “I don’t really have much to compare it to besides the ditches in Manitoba, but ya, the views, the scenery.”

RIGHT PAGE, CLOCKWISE STARTING TOP LEFT. 1. Jillian Playfair entertains her 4-month-old son, Alistair, in the lodge at Murray Ridge Ski Area. 2. Regan Lindores pulls her son, Holden, toward the T-bar at Troll Ski Resort. 3. Jackie Goetz and Alvin Seymour from Port Edward pose for a portrait at the base of Shames Mountain Ski Area, 37 km west of Terrace, BC. “Look at the line, there’s no one there! It’s January 2, a bluebird day, incredible mountain views…It’s just quiet and lovely. We love it here.” 4. A mine worker on his way to work in Wells, BC. 5. Kendra Isaac, from Vanderhoof, BC, is covered in ice after some cold -20 C runs at Powder King Mountain Resort, 195 km north of Prince George. “I’ve only ever skied in the north. I just love the mountains here. It’s good to get out in nature. There’s usually really good powder days [here] and I go into the trees.” 6. Skiers on the green run Big Easy at Mount Timothy.

Experience the Tyax Difference . We are a family-owned heliskiing operation and wilderness lodge, with the hospitality to match. We offer easy ground + helicopter transfers from Vancouver, a full service spa and chalet and lodge buyout options for the ultimate private experience. Oh — and with one group per helicopter and Unlimited Vertical , at Tyax you get more skiing, for free .

We would love to see you this winter, scan the QR code to find out more.

Come home to Pemberton! Born and raised in Pemberton Valley, I am the fourth generation of my family to call this beautiful valley home and this li le slice of paradise has my heart. I know the valley and the people, I truly enjoy sharing my love of Pemberton with others and helping them to find the perfect proper to call home. As a licensed Realtor® with over 19 years of experience, I have the skills, background and knowledge to guide you through the process with confidence.

Let’s connect! www.realestatepemberton.com

Relearning to snowboard (and tons of other stuff) after a traumatic brain injury

words :: Feet Banks

It was a pretty standard sunny morning in the backcountry. Until it wasn’t.

And to those who happened to notice, it looked like a pretty standard snowboard bail—Spenny caught an edge in variable snow and tumbled, ass over teakettle. Most of the crew kept riding; it was the first bluebird day in a while and this wasn’t even a real run, just a quick rip back down to the snowmobiles.

But Spenny, aka Spencer Craig—a born-and-raised Squamish snowboarder/sledder/golfer/mechanic/source of general comic relief—didn’t get up.

“My buddy Tyler [Thompson] was the last rider. He found me and radioed the crew,” Spenny says. “I was fully unconscious, snoring and having a seizure. DCP [David Carrier Porcheron] and the rest of the crew came up. I must have hit something, because when they pulled my toque up they could see my brain. That’s when things got serious.”

"I must have hit something, because when they pulled my toque up they could see my brain. That’s when things got serious.” – Spenny

A second local snowmobile crew was in the area and moved quickly to assist. Firefighter David McKinnon started first aid while Neal Sikkes—Spenny’s riding partner and member of Squamish Search and Rescue—ripped up to a ridge with cell service to call 911.

“I quickly expressed how serious it was and started stressing the need for a helicopter as soon as possible,” Neal says. “I had to stay up on the ridge to coordinate communications and it was difficult to feel like I should be doing more, but overall the two crews worked together and did really well—we activated quickly, did first aid, got his neck stabilized, kept him warm and he was in the heli in under three hours.”

Every minute mattered. “The paramedics stapled my head closed in the helicopter,” Spenny says. “Or that’s what they told me later. I remember almost nothing from that entire day, but I do remember riding in an ambulance from the Squamish airport and hearing the guys up front arguing with the hospital to have the air ambulance ready because I didn’t have time to come inside.”

Rushed to Vancouver General Hospital, Spenny underwent emergency craniotomy surgery for an open depressed skull fracture— essentially an operation to remove fragments of his skull that had been smashed into his brain as well as to repair torn dura mater. The impact also fractured his orbital bone, nose and jaw, and spiderwebbed around to the back of his skull. “It was a good dent,” Spenny says. “I was in the hospital two or three nights. The doctors were awesome, but I was in a room with four other people and a wing with like 27 others. The noise drove me nuts; I couldn’t handle it.

Somehow I passed a couple required tests—I’d torn my knee, too, but I managed to get on and off the toilet single-legged—and checked myself out of there.”

Then the real work began. Dosed with anti-seizure medication and barely able to sleep due to the pain, Spenny began trying to put his life back together with his girlfriend Alyssa Hazelton (aka Lyss) at his side. “I couldn’t do anything. Reading or watching TV gave me headaches and made me dizzy. I couldn’t listen to music. I couldn’t chew food. I kept having seizures. I ended up back in the hospital for a bit with more brain bleeding. The first two weeks was just absolute silence—me, my girlfriend and our dogs. I wasn’t thinking about the future, I wasn’t thinking about anything. I was basically brain dead—just surviving, no activity allowed—for probably six weeks due to risk of seizure.”

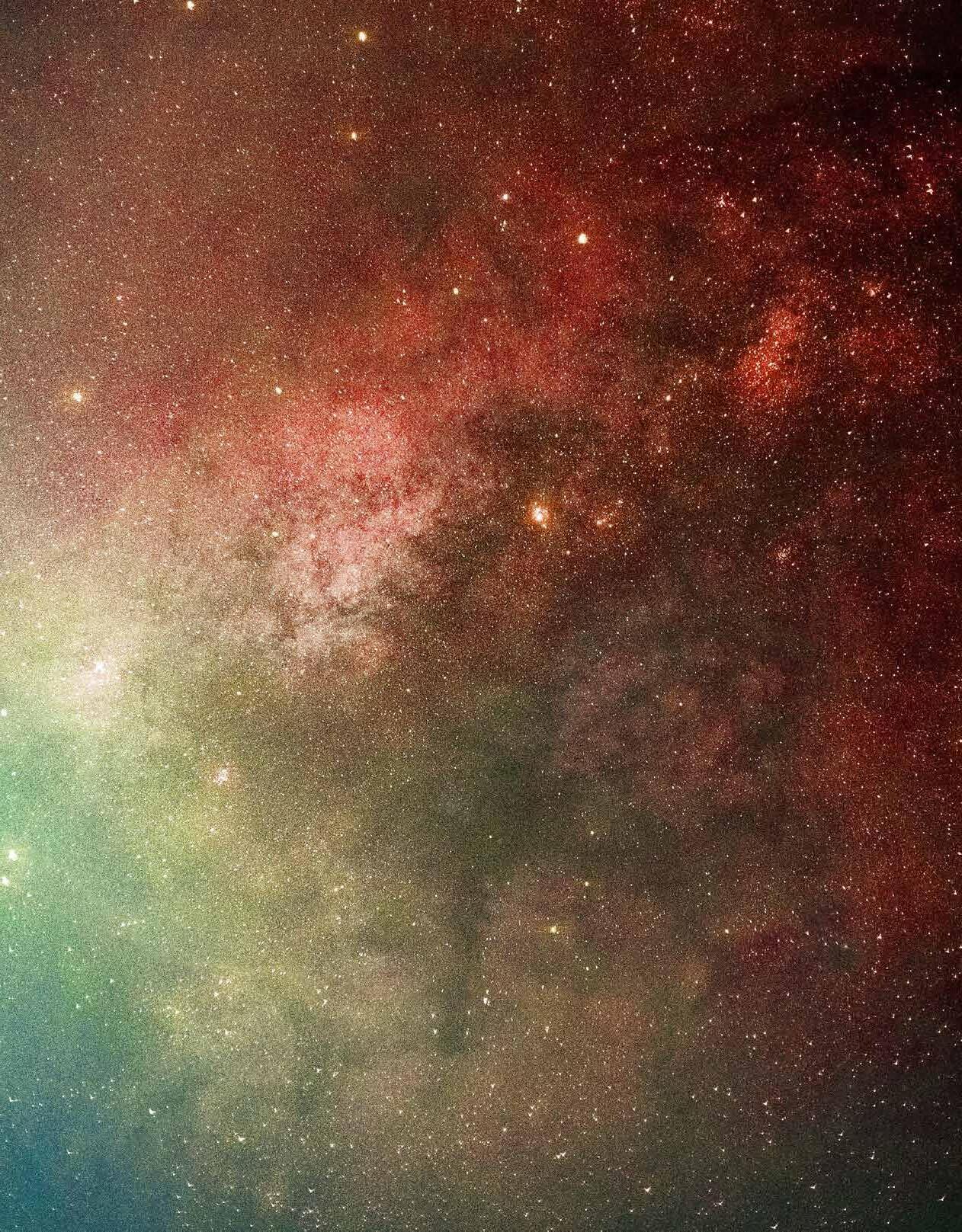

Slowly, and with tons of support from family, friends and Lyss, Spenny began putting the pieces back together. “One of the first things I can remember is seeing stars in the night sky,” he says. “That blew my mind. Next it was relearning how certain foods taste. And being stoked on that. During those months I kind of didn’t have a care in the world. I knew my girlfriend and my dogs, but otherwise it’s hard to worry about stuff when you don’t know it exists.”

It wasn’t all smooth sailing. “My sister would drive me down—five days a week—and I’d take public transit to G.F. Strong Rehabilitation Centre,” Spenny says. “I had to keep the map open on my phone or I’d get lost. And one day getting off the SeaBus I saw a helicopter parked at the Vancouver Harbour and suddenly just broke down crying. The PTSD kicked in hard. Another thing was getting a CT scan—the smell in there, like chlorine in a pool. Suddenly I started crying and had no idea why.”

"The darkness still rises up sometimes, and I feel like now that it has been a year some people expect me to be back to normal—and I’m not."

Supported by a GoFundMe campaign started by friends and with daily physical, emotional, speech, vestibular, cognitive and occupational therapy, Spenny’s healing crept along. “I didn’t know it, but I was so depressed I repressed all my other emotions and became numb. My brain was learning how to work again, and I felt totally alone. That was the most difficult part, not being able to relate to anyone.”

But then, like a beam of sunshine cutting through a swirling mass of mountain clouds, one thought arrived, took hold and stuck: “I wanted

to go snowboarding again. That became my lifeline through all the therapy and the rehab and the tears and the hours at the gym. I want to snowboard again. And then when I finally did, I’d forgotten how!”

Snowmobiling came easier—Spenny has logged a few days already this season—but relearning the motor skills, balance and weight transfer for snowboarding took more time. “I have over 10 days on the ski hill now,” he says. “It’s kind of amazing, though. Simple cruiser runs or even the littlest side hits are so fun again. Sledding and riding—the warmth of the sun, the cool air, the sparkling snow…it feels like home. I have emotions back, not all of them, but some. The darkness still rises up sometimes, and I feel like now that it has been a year some people expect me to be back to normal—and I’m not. Other people who had traumatic brain injuries have reached out and helped me keep realistic expectations. But right now the focus is to get out into the mountains, have fun, get my knee in shape and build cognitive strength. And not hit my head, for sure that.”

Spenny says even 30 minutes of socializing, or anything requiring much focus, can be exhausting and will drain his tank for hours or days. “Even board games are a huge challenge,” he says. “But mostly, I’m just hugely grateful. If my injury had been three millimetres lower, I’d have severed an artery and died. If I’d been out there for 60 minutes longer, I’d have bled out. I’m so thankful to everyone that saved me that day, and to everyone who reached out with help, however that may be. What happened to me, it can happen. Everything can change in an instant. So yeah, wear a helmet even riding the backcountry. Get your wilderness first aid. And most importantly, reach out to your friends. If they cross your mind, there’s a reason for that. You never know what someone is going through or how long they’ll be here. Reach out.”

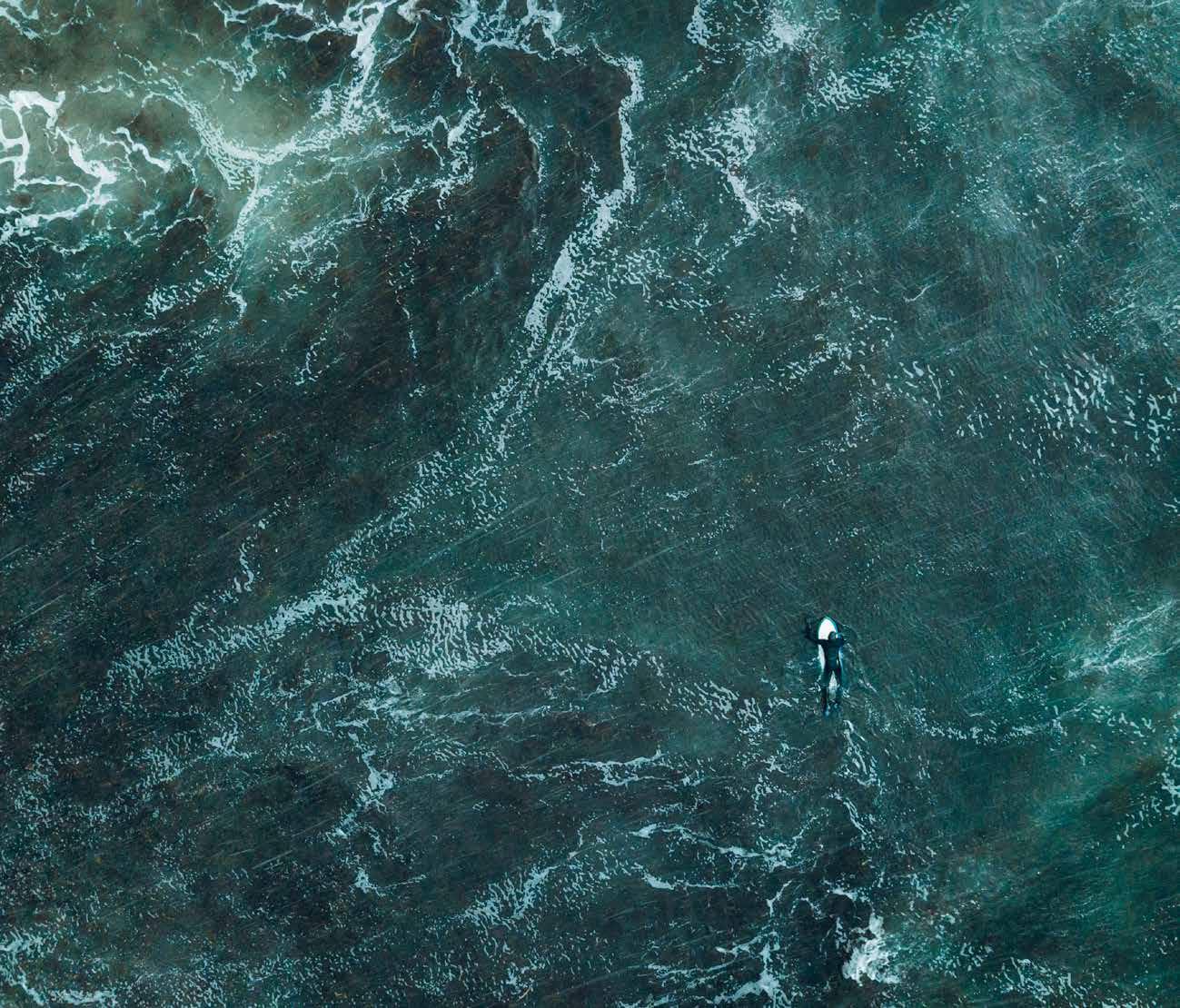

photography :: Jimmy Martinello athlete :: Brooke Dawson

location :: Squamish, January 2025

First jumped by Spencer Seabrooke in honour of a fellow BASE jumper who’d passed away, the name of this exit remains a secret to the uninitiated. In January 2025, photographer Jimmy Martinello made the trek across the mighty Squamish river to capture this shot of local Brooke Dawson, who did more than 200 BASE jumps in her first year of the sport, which is “way more than I expected,” Brooke says, “but I am totally hooked.”

“This jump is one of the most memorable,” she adds. “Not just for the view, but because it’s a mission to get there—a paddle across the river followed by a gnarly bushwhack to the base. After that, it’s a loose-rock climb to the top of the spire—definitely not a casual hike.”

“What makes this jump so unique is the intense focus required,” says Brooke, who originally hails from Calgary and had a lot of skydiving experience before she started BASE.

“You’re perched on a tiny rock platform with just enough space for you and your closest friends. The gear-up process here feels different and there’s a certain energy that builds as you prepare for the jump. That’s when the adrenaline really kicks in. The tiptoe out to the edge, knowing you’re about to take that leap off one of the most beautiful and exposed spots in Squamish, gets the heart racing every time.”

– MJ Castor

words :: MJ Castor

Gringa was a good dog. She could ride a snowmobile, keep up on long bike rides and bound through pow tracks with the best of them. “She was a rescue dog,” says Joe Lammers. “Her mama was an American pit bull, but papa was a rolling stone so I wasn’t sure of his breed. Gringa was six or seven months when I picked her up at the pound—no training, no socialization. She ended up being my best friend and adventure buddy for the next 11 years.”

Dogs play a huge role in mountain communities. They’re a warm companion on cold nights and a reliable alarm/security system if a bear wanders near the campsite. Dogs are loyal, loving, and they give us an excuse to get outside. “Dogs especially can be synonymous with adventure, and they become a part of the family,” Lammers says, “or in some cases the whole family.”

After Gringa contracted lymphoma in 2022, Lammers noticed a change in her behavior that struck a chord with him. “We’d drive to Kelowna together each week for treatment—five hours round trip— and I watched her assume this calmness that really felt like wisdom and acceptance. We went on a journey together. I knew her cancer was terminal and I was just buying time with these trips, but it got me thinking about people who don’t have the financial means to do what we were doing. I came up with the idea for Gringa’s Fund on one of those drives.”

Working with veterinarians in his homebase of Revelstoke, Joe created Gringa’s Fund to help financially challenged senior citizens who are suddenly faced with unexpected vet bills. “The world is only getting more expensive and people on fixed incomes are really feeling the squeeze,” he says. “At the same time, I think pets are critically important for seniors because as you age your social circle contracts—people pass away, they move to homes or to go live with family—or we have less energy or mobility to go out and be social. So life at home, with our pets, becomes that much more important.”

Lammers said losing his own father shortly after Gringa passed really cemented the idea behind Gringa’s Fund. “When my dad was in and out of the hospital, I saw how important my parents’ dog was to both of them. When mom was home alone, she had this furry ball of love and joy that was always happy to see her and do stuff with her. Seeing that firsthand definitely pushed the idea into action.”

An ex-ski industry professional turned successful realtor, Lammers has always donated a portion of his income to local

charities. “I decided to commit all my donations to the fund and then began publicizing it amongst friends and clients and on social media. Donations rolled in and the fund got quite healthy.”

Joe lets the veterinarians at the Revelstoke clinic screen candidates who need support from Gringa’s Fund. “The first one was Rosie the cat,” he says. “She had pyometra, a potentially fatal infection and Gringa’s Fund helped her owners pay for the surgery. I am not sure Gringa would have been that excited about helping a cat, though…”

Get used to it, Gringa, because in its first year the fund also helped cats named Noel and Zigzag, as well as a dog named Ty who was attacked by two other dogs and needed emergency surgery to close lacerations on his neck. “Those owners were on a single pension and obviously had to make a quick decision,” Joe says. “Gringa’s Fund was able to relieve that stress and save the day.”

In just over a year, Gringa’s Fund has helped seven animals and families. Joe admits “scaling anything is tricky” but says he intends to spend 2025 figuring out how to bring Gringa’s support beyond his hometown of Revelstoke, with Squamish on the top of the list for expansion. A proper website is in the works, but anyone looking for more info or to donate to the fund is welcome to reach Joe via Instagram: @joe_lammers_revelstokerealtor.

“I’ve

been to 30-plus countries and haven’t found a better place yet than the Coast Mountains. And even if I did, I would never leave the

words :: Sarah Woods & Feet Banks

photos :: submitted

Legends aren’t born. And they’re not made, either. They arrive from the future.

Al Crawford is one of these future humans. Embedded in nature and aligned with cosmic laws, Al has built Whistler’s iconic Canadian Wilderness Adventures from a lifetime of zigging when the world zags, pushing against the “normal” way to do things and, mostly, listening to his heart.

“We just had fun and worked hard,” Al says about building Whistler’s toprated adventure company, which is consistently recognized as one of the best places to work in the province. “But the spiritual stuff works, too—trusting your intuition, manifesting through the law of attraction, self-hypnosis, vivid dreaming and using meditation or journaling to tap into a higher consciousness. Nowadays, spirituality is trending and corporate guys talk about it, but back then, people would have thought I was crazy, talking openly about this kind of stuff.”

Let’s be clear—a future human doesn’t necessarily time travel. Instead, Al has mastered one simple thing: to be in the moment. The future is happening at the end of every moment, so the only way to truly be in the future is to be as wholly in the present as possible. And, like a kid painting on a fresh canvas, it’s about never knowing what the final picture will be—there may never be one—but the gift of imagination and the confidence in the present keeps things going, and suddenly you have an answer to a problem you maybe didn’t know needed solving.

Nowadays, spirituality is trending and corporate guys talk about it, but back then, people would have thought I was crazy, talking openly about this kind of stuff.

But let’s back things up a bit. Before Canadian Wilderness Adventures, before Whistler, before all these present-moment and future-human concepts, Al grew up in his father’s welding shop in a small English-speaking Quebec town of about 600 people, many of whom never left town and that was just fine with them. But Al’s mother talked him into attending Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario, by convincing him it would be the best time of his life.

“And it was,” Al says. “It was a blast. I got a Bachelor of Commerce degree with a major in marketing, but as my four years closed out, I was really worried that the fun was coming to an end and life would be something less. I discussed this with my Uncle Ken—the fun uncle—and he suggested I move to Whistler to keep the good times rolling. And he was right. I showed up in 1992 and it was the time of my life. It still is.”

Fresh in town and armed with a practical mindset absorbed in the welding shop, Al gravitated to a job where he could work with his hands—a lift maintenance helper. “I couldn’t believe they were actually paying me seven or eight bucks an hour to drive snowmobiles and ATVs up and down the mountain, delivering tools. Then I got a job driving food up to the alpine restaurants in a snowcat.

The second season I started as a groomer and life was grand. All my buddies from university were getting married and becoming wellpaid managers and bankers. They’d laugh at me, but I was spending every day of the year on the ski hill. It seemed like ten years later they were all divorced and depressed, asking if they could quit their jobs and come stay with me.”

While working on Blackcomb, Al caught sight of a long row of mountain snowmobiles all lined up neatly and had a vision of one day having a fleet of his own. “That visual threw a switch in my mind. I started thinking and talking about an idea that wouldn’t go away. Then a coworker said, ‘You should connect with Doug Washer,’ who was also working on the mountain and talking about a similar vision. We ended up working as whitewater rafting guides together that next summer and that’s really how it all started.”

That coincidence (was it, though?) spurred Al and Doug to each buy three new Ski-Doo Summit snowmobiles and start an adventure company to tour people around Blackcomb after the lifts closed for the day.

“This is when Whistler as a whole was looking to diversify and add non-skiing activities,” Al says. “We fit right in. We used the kid’s camp building as an evening base and ran tours up the switchback roads we knew were empty to the Crystal Hut for a mountaintop meal—chili and soup at first, and eventually fondue with live entertainment. We were fortunate that our business could use facilities and trails already in place but not being used during those hours. Doug and I both worked four-on, four-off ten-hour shifts as groomers, opposite schedules so we could bring in income to grow the business and still each guide on our days off. Every eight days, you’d have to do a double and miss a night’s sleep.”

Over time, the snowmobile fleet expanded, the team grew, a snowcat and ATVs were added, then a basecamp south of town with a new tenure to explore via dogsled, snowshoe and more. Eventually Doug and Al parted ways, and new partners—Ute and Uli Jordan—came aboard. Currently home to more than 55 employees, with dozens of awards and a 30-plus year track record, Al grew “Canadian” (as it’s locally known) the only way he knew: by instinct and hard work, and alongside good people.

“ It seemed like ten years later all my buddies from university were divorced and depressed, asking if they could quit their jobs and come stay with me.”

“I’d look at resumes, but I rarely needed to check references,” he says. “I’d meet someone, and if they felt right, I’d hire them. Then I’d use my intuition and hear a number in my head that seemed right for their wage. People always accepted it and I truly believe those numbers were coming from a higher intelligence. I have amazing managers to do the hiring nowadays, but the right people still seem to show up and the job creates itself for them. I love to see people grow into their potential here. That’s the gift for me, seeing people shine within their natural abilities. This whole thing—the business, the basecamp, everything—was built one person at a time.”

And so were the tours Al and his teams offer. Forget mass-market analysis studies or brand-building seminars, Al simply spoke with the people who booked his tours and others he’d meet on his own travels. Mostly he listened. “All anyone wants is authenticity. We started growing during a time when Whistler was trying to be really polished, but most of the people I talked to, they wanted the old, rustic Canada—log cabins, snowshoes, forests and axes. We leaned into that, and people love it because a lot of times that’s what they came here for.”

Authenticity is in the heart—which is the moment—but Al found new joys in creating an aesthetic with one foot firmly in the past. “Another reason I moved west in the first place was reading about those old pioneers and cowboys,” he says. “And thankfully, from a business sense, rustic is an easy and affordable theme to pull off.”

Particularly in a region/culture pushing hard for modernity. With a keen eye for opportunity, Al has been able to salvage much of what makes Canadian Wilderness’

“Every day just keeps handing me fun stuff and I just act on the feeling. By the time my brain catches up, we’ve already created something.”

Our team of experienced family law lawyers is here to guide you through life’s changes with expert legal advice and personalized service.

Race & Company LLP has been proudly serving the Sea to Sky and our worldwide clientele with local knowledge and proven integrity since 1973. Our 30+ lawyers and staff are dedicated members of the community, providing volunteer time and expertise to a variety of local charities and organizations.

Family Law

Cohabitation Agreements

Marriage Agreements

Separation Agreements

Divorce

Collaborative Divorce

Property Division

Spousal Support

Parenting Time & Custody

Guardianship

Callaghan Valley basecamp so unique. From vintage axes, moose antlers and snowshoes to a reclaimed (crowd favourite) entire CN Rail caboose. “That thing weighs 40,000 pounds,” Al says. “I got it for a good deal off a couple that were getting divorced, but then the crane company said it was going to take two cranes and $40,000 to move it because there were some power lines to contend with. We didn’t have that kind of money.”

What Al did have, thanks to his childhood in a welding shop, was an ability to connect with the older generation, including a 70-yearold truck driver named John Langus. “John and his buddy—who was also 70 years old—used an excavator to roll the caboose up onto an old stump then pushed it right onto the trailer, smoking cigarettes the whole time. I mentioned it looked pretty tight with the height of the power lines, and John looked up from the truck window and said, ‘It’ll be fine. But if it isn’t, I’ll tell you one thing—I’m sure not stopping.’ It all worked out. No one gets stuff done like a couple old-school loggers.”

That sense of looking beyond the standard limitations or rules of life (and time and space) allows creation to unfold from within. And that vibe—living in the opportunity of the present while staying rooted to older, simpler times—seems to help Canadian Wilderness

“I trust my intuition and act in the moment. It would be boring if I knew what tomorrow is going to bring.”

guests open their own connections to the nature and beauty of the Coast Mountains.

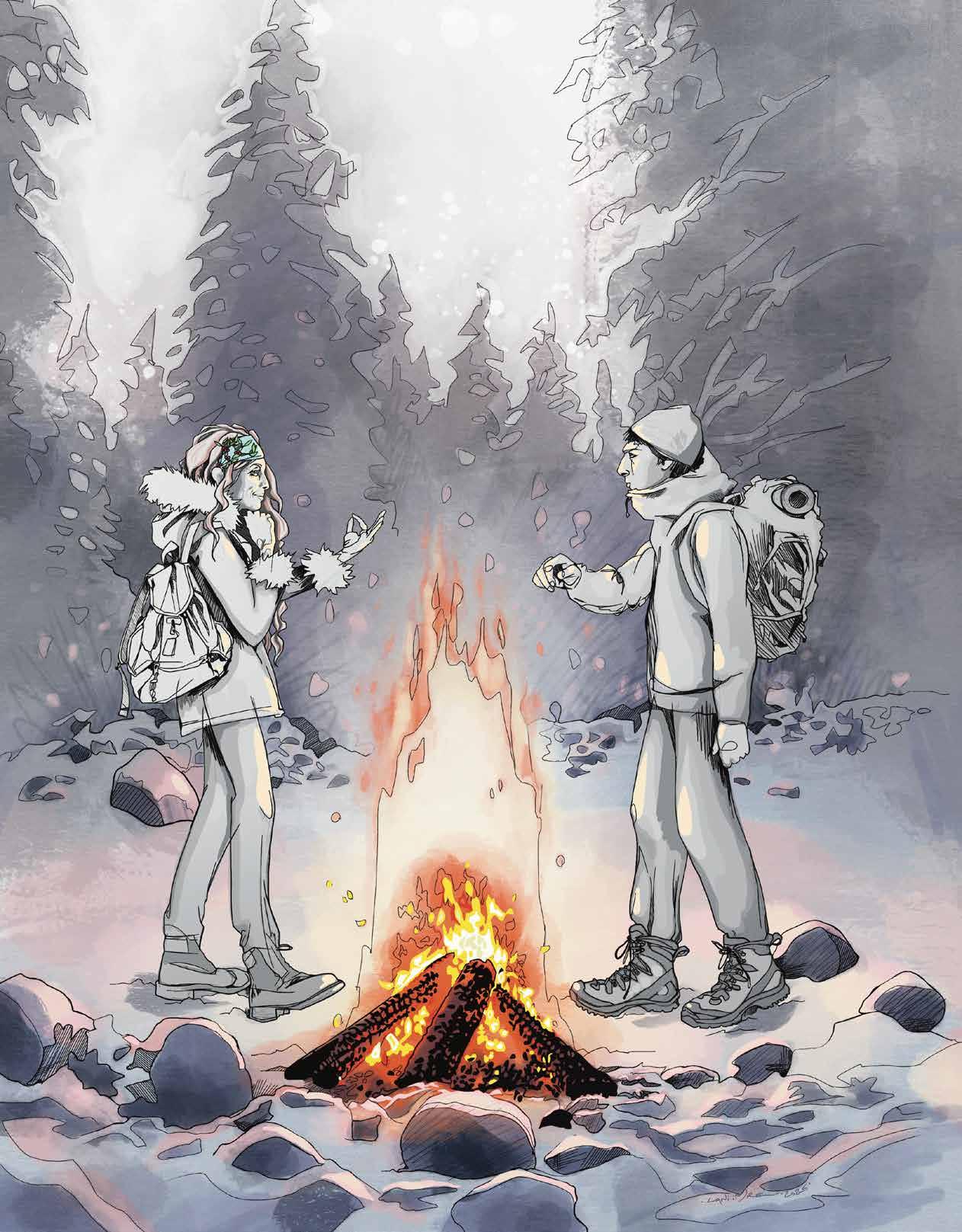

“Actually, you know what’s the craziest, simplest thing that people love the most?” Al asks. “Sitting around a bonfire—a real, wood, burning bonfire. Most places have bylaws against real fires now. So many of the people that come on our tours have never sat around a real fire, that’s baffling to me. Who wants to play pretend around a flaming propane ring? For millions of years, humans, or humanoids, have been sitting around a fire. It should be a basic human right. I’m glad we can still provide that, at least in the winter, anyhow. It’s really important, those moments for people…those can be everything.”

Legends rarely think about building a legacy, it just happens along the way. And the best way to predict the future—the only way—is to show up and build the one you want. One idea, one moment, one bonfire at a time.

Explorers Børge Ousland and Vincent Colliard trek across the planet’s largest frozen expanses, documenting climate devastation in a bid to save Earth’s “big freezers.”

As destructive wildfires become the new norm in multiple regions of the planet, Ice Legacy—spearheaded by Børge Ousland of Norway and Vincent Colliard of France—stands out like a lone glacier against a burning horizon, a stark reminder of what’s at stake in our rapidly warming world.

That mission? To walk across the world’s 20 largest icefields, collecting samples, specimens and snapshots along the way to document the devastation of climate change and pressure governments to take protective action.

“If we do not care about these big freezers, we will end up having constant fever because the planet will be too warm,” says Colliard. “We must protect ice, and it concerns every living creature on this planet.”

The team is 11 icefields in, and the latest adventure was the Juneau Icefield in Alaska. This field sprawls like a frozen cathedral of ancient blue and white, its glacial rivers carving silent hymns into the stark Alaskan wilderness.

“The transition between blue ice and snow higher on the plateau was pretty crazy!” says Colliard. “The fresh layer of snow forms extremely thin bridges and it’s sometimes impossible to see. It’s treacherous terrain!”

Treacherous—and stunning. Colliard points out that the Juneau landscape, and those of the other icefields, are those rare places on the planet, like oceans, where humans can’t cover the crust with concrete. There is no advertising, no red lights and no casinos—just beauty and wildlife.

That beauty is degrading, though, and Ousland and Colliard are bearing witness to the changes with every new icefield they cross.

“The snow bridges are becoming weaker and weaker,” explains Colliard. “There is more and more algae on the ice, which is a sign that the temperatures are rising. There is more and more black soot, which contributes directly to the ice recession. Now we have to reschedule certain expeditions because the summer comes too early and there is a lack of snow to access and exit the ice.”

The Juneau expedition was rescheduled for the fall because of a different reason. “My wife Caroline gave birth to a little Viking in the spring, so Børge and I had to postpone our trip until fall,” says Colliard. “At that time of the year, we had to navigate extensively on blue ice and we crossed hundreds, maybe thousands, of open crevasses. We covered 172 kilometres in 20 days with no rest day! A fall crossing is much more complicated.”

Colliard and Ousland are not giving up, though, even with the increased risk climate change is presenting. They are clear on their mission, inspired by American Will Steger who led a dogsled expedition across Antarctica that covered 3,741 miles in seven months in the winter of 1989-90. Steger used the mission to get the attention of world leaders, which led to the protection of Antarctica from mining exploitations with the 1991 ratification of the 1961 Antarctica Treaty. – Kara-Leah Grant

Follow the Ice Legacy Project at www.icelegacy.org and on Instagram at @icelegacyproject.

“We hope that Ice Legacy will be a visual example of the glacier recession and will pressurize governments to clean up their acts.” – Vincent Colliard

It was the ‘90s and the Whiskey* flowed like wine. Skiers stopped spitting on snowboarders and started stealing their tricks. And their girlfriends. I was swept up in the hype of a new sport that was born from punk rock and skateboarding, one that had more in common with Minor Threat than mogul fields and had somehow managed to sneak in the back door of the classy resort scene built by skiers. My peers fondly refer to the ‘90s and early 2000s as the Golden Era of snowboarding, with its anti-heroes, relentless innovation and “outcasts to Olympics” storyline. It truly was an incredible thing to live through.

It’s 30-something years later and I’ve recently resigned from a great job to pursue a simple goal: snowboard more. As a

veteran of the rebel years of the snowboard world, I often get asked about those times, and as much as I love telling stories, I refuse to become one of those “it was better in MY day” assholes who never bothers to notice what’s happening today.

So what is happening today? Is there any anarchy in the era of Instagram? Has global homogeneity and personal branding rounded off all the rough corners of the culture of shred? Where does the heart of snowboarding beat today, and is it still worth running away to the mountains?

On a recent Air Time podcast, host Jody Wachniak and I had a lively back and forth about the current state of snowboarding compared to the GoodOlDays™ and I jokingly asked him,

I talked to him about the change from runaways and misfits to personal trainers and soccer moms. What’s it like for a young kid coming up?

“What have you done to our culture?!” I thought it would be a good time to get his take on what is going on today.

A lot of the early generation of snowboarders hold up the outsider and DIY aspects of the punk scene as the reason why snowboarding was so raw. I asked Jody if there is any punk left in snowboarding and, more importantly, does snowboarding need punk rock?

“It needs modern-day badasses,” he replied. “We don’t need people to redo what Johnson and Kearns* did. They did it, it was awesome at the time, it’s what people wanted, but do we need to do it again? I don’t think we do. I think the counterculture, that’s not playing into what society’s norms are right now, is awesome. When I meet a kid that’s not that into social media, but they are good at snowboarding and they still want to make it, that’s kinda refreshing.”

But it’s inarguable that social media has changed the game. Projects that used to be funded and facilitated by sponsors and a team of photographers/filmers/writers/artists are left to the riders themselves, which can hijack a snowboard season worse than a November rain crust. For Jody, it means that being a world-class rider and being sponsored isn’t enough to make it anymore.

“I’m a podcast person, I’m a photographer, I’m a writer, a mentor, a snowboarder, I run events…I wear all those hats now, just to stay in the game. If I could do one of those I’d love to do just that, but

the reason I’m faced with burnout and stress right now is because I’m doing everything I can to be able to follow my passion.”

It’s been said that big money in the boom years ruined snowboarding’s authenticity, but the scene doesn’t have that problem these days. In a lot of ways, we’ve gone back to where we were in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s—there are a handful of people making a living as snowboarders and a whole lot more who are fully committed to trying, whatever it takes.

And there is a freedom in a scene like that, because the stakes are lower when nobody is getting rich, but there is also scrutiny now that didn’t exist prior to social media. If you accidentally grabbed tindy in the old days, your friends might spend

a few minutes making fun of you, but post that clip online today and you could end up being Jerry of the Day to 2 million strangers.

Anyone who can remember the snowboard scene in the ‘90s and early 2000s will recall the name JF Pelchat. His powerful riding and off-hill antics with the Wildcats crew assured his inclusion in the history books. Aside from his stint as a pro, though, he was always tinkering with and building his own equipment, which led to a patented binding innovation that became Now bindings. Legacy aside, JF is also now the father of two badass daughters who are not only following in his footsteps, they’re boot-packing an impressive path of their own.

I asked him about how he approached raising two talented kids in the shred world.

“I think what was important for me was to expose [them] to community events like the Baker Banked Slalom**,” JF says. “Coming at a young age and seeing what the community is…for them to make their own judgement…if they like it, if they want to be a part of it. For them to see that at a young age and immerse into it. And then Whistler, with everyone who is here, they told me it was a no-brainer, they really want to be in snowboarding because of the community and the people. And I think that’s important.”

Jubes and Billy Pelchat not only got involved in snowboarding, they got good, got sponsored and started travelling around the world to shred. But maybe more importantly they’ve started RWK (Real Wild Kittens) to give more girls a path into the skate and snowboard scene through events and camps. This kind of grassroots initiative is the foundation of any thriving scene.

Beyond the progression of the culture, what about the actual riding? The “spin to win” ideology might be reaching its physical limit at 5 full rotations. So where does progression go? I asked JF if you have to be able to do an 1800 to be a pro today.

“No, no. If you look at what Arthur Longo does, the side hits, and look at guys like Jaydn Chomlack and Cannon Cummins… the backcountry freestyle, for men and women, I think there’s a lot there to be conquered and the reason why it hasn’t is because it’s hard as f@#k. It’s not accessible, so it’s hard, but there is a lot of potential there.”

But to get there, you have to start somewhere, and that somewhere is the Whistler Valley Snowboard Club. Rob Picard started the Club in 1997 and built the road that has helped more than a few young rippers go from pre-teen to pro. I talked to him about the change from runaways and misfits to personal trainers and soccer moms. What’s it like for a young kid coming up?

“They’re all very keen,” Rob says. “At young ages they’re very motivated, and you can see it… We try to bring those kids together who aspire to more. When they’re all of the same kind of mentality, the same work ethic, and put the same work in, it’s awesome.”

But it’s not all about becoming the next Travis Rice. If it’s not fun, kids will wash out of the program at some point to chase other priorities. Which is why it’s important to Rob to create a compelling experience for kids like Jubes and Billy Pelchat who came up through his program, and current talents like Kanon Ling and Logan Daling.

“What was important for me was to expose my daughters to community events like the Baker Banked Slalom.”

– JF Pelchat

“One of the big things that we do is to try to make them snowboarders for life, that’s the agenda,” Rob says, adding that a large portion of WVSC kids do stick with the sport. Not just because they make it as pros, but because they develop friendships on the snow that keep them coming back. “When I run into kids I used to coach years ago and they say, ‘Those were the best years of my life,’ that really hits home. I love that shit.”

So what does the culture look like today? I think it’s a little less carefree than it used to be—and a lot more digital—but it seems like it’s becoming possible to make your own path without bowing to the algorithm. I asked Jody what he thought the future looked like.

“I think [Whistler local] Brin Alexander is a really good example of somebody who plays the game of being in the digital world but doesn’t make it his be-all and end-all. His thing is actually being in the mountains… People ask, ‘How is he so good?’ It’s because he lives in the mountains every day. If you want to be it, live it, and then it’ll just happen naturally. Even at the beginning if you’re not the

coolest…. Brin does everything the way he wants to do it and he’s not being defined by these subjective rules about what snowboarding should look like. He just does it his way, and it’s inspiring.”

To me, that sounds a lot like where we came from. So, in the most important ways, the snowboard dream still looks the same. There’s a thriving scene, full of individuality, with a ton of room to progress. DIY is alive and well, maybe more so than ever. The saying is that history doesn’t repeat itself, but it rhymes. I asked Jody if he’d recommend that a kid today should head to the mountains to chase the dream.

“Yes, I 100 per cent recommend chasing the dream, but realize that the dream you’re imagining it to be won’t be the dream. When you get there, it will be very different. I got there and it’s nothing like I imagined. But it was my unique path and I’m glad I did it.”

Dano was a snowboard photographer when you could still make a living at it. Now he’s just a snowboarder. He lives in Whistler with his wife and his dachshund and is trying to get 50 days in this season.

RESIDENTIAL

Construction Management Design & Build

Construction Management Design & Build

Construction Management Design & Build

High-Performance Homes Renovations RESIDENTIAL

Construction Management Design & Build

High-Performance Homes Renovations

High-Performance Homes Renovations

High-Performance Homes Renovations

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com

604-366-8116

604-366-8116

604-366-8116

604-366-8116

info@coastessential.com coastessential.com

604-366-8116

ACUPUNCTURE

ROST THERAPY

CRANIOSACRAL THERAPY HYPOPRESSIVES MANUAL THERAPY

New snow monitoring in Squamish provides S2S locals with more accurate (and safer) backcountry data

words & photography :: Chris Christie

On any given morning, my backcountry decision-making process starts at home. With caffeine in hand, I scroll through favoured links—weather, snow quality, avalanche advisories—to decipher the nuances in the data available and build the best adventure plan. But for the mountains closest to home (Squamish), the information available has never been that local, until recently. Avalanche forecasting for an entire province is tricky. Based out of Revelstoke, professional forecasters at Avalanche Canada (AvCan) receive localized daily submissions of technical snow, weather, avalanche and terrain information from other professionals throughout the province (guides, ski patrols, other avalanche technicians, etc.). The province is divided into regional boundaries daily by AvCan forecasters and then further broken down into subregions to reflect variable conditions within each area. Hazard advisories are posted daily during the winter season. It’s a complicated system and, living in the Sea to Sky, particularly Squamish, we sit on the border of three large regions that often have different danger ratings, despite their proximity.

For most of my ski career, I didn’t think much of the forecasting for Squamish as I rarely skied here, instead driving north to Whistler, Pemberton and beyond. Increased highway congestion has been eating at my desire to leave home, however, and the arrival of the Sea to Sky Gondola opened new terrain and a local mountain culture. When conditions align, skiing above the Salish Sea is a true highlight of living in the Coast Range.

Not far from the gondola’s Summit Lodge, the skin track rises steeply out of the valley, giving the advanced skier an incredible variety of unpatrolled options that require careful assessment and decision-making. While “The Mini Dolomites” (my own nickname for the Sky Pilot Range) have a high concentration of excellent ski mountaineering options, the approach and skiable areas are complex terrain with many uncontrolled avalanche paths. I’ve always wondered if we are receiving consistent data representing our surrounding mountains. And with Squamish essentially falling on a regional borderline, how do we manage the information given to us?

Generally, we have a coastal snowpack in the Sea to Sky, meaning moist, cohesive snow. Counting on that fact alone is a poor risk-management choice, as we don’t have to move far to find

variability in conditions. Each valley has its own unique weather pattern, influenced by ice caps, elevation, aspect, wind, accumulation and of course climate change. All of these factors impact stability. With a newfound concentration of skiers coming to Squamish, there was a need for consistent, professional and focused gathering of data relevant to this area.

When avalanche conditions are at a high hazard level, the Sea to Sky Gondola will not upload skis or snowboards.

To add a new level of clarity, Zenith Mountain Guides Evan Stevens and Eric Carter have been collaborating with the Sea to Sky Gondola since last winter to fill that information void, providing local observations and data to the Canadian Avalanche Association’s professional information exchange, known as InfoEx. Zenith Mountain Guides are out weekly (at least), collecting information with boots on the ground and hands in the same snow we are skiing here in Squamish, while also discussing their findings with local colleagues. All that information is added to data collected by AvCan forecasters in

Revelstoke to create more accurate forecasts for our region.

Zenith Guides’ unbiased field notes update mountain users of current conditions for skiing, including forecast weather models. On top of that, the Sea to Sky Gondola has funded a weather station at the Exit Gulley (1,580 metres), providing hourly weather updates. Combined, these new tools are useful for developing a sense of local conditions and mitigating risk in the Squamish backcountry. Our local avy forecasts still come from 500 kilometres away in Revelstoke, but the information they’re based on is more local than ever before.

One important note: When avalanche conditions are at a high hazard level, the Sea to Sky Gondola will not upload skis or snowboards. This policy is in part for the safety of guests, but also in respect of local SAR resources who would be dispatched in the event of an incident (or multiple incidents).

New and more localized information is an excellent resource, but experience, caution and good decision-making is still ultimately up to each individual. Adding these resources to your morning routine is an excellent foundation in the trip-planning process.

Subscribe to the weekly Zenith reports at snow.zenithguides.ca and get the Avalanche Canada forecasts at avalanche.ca/map.

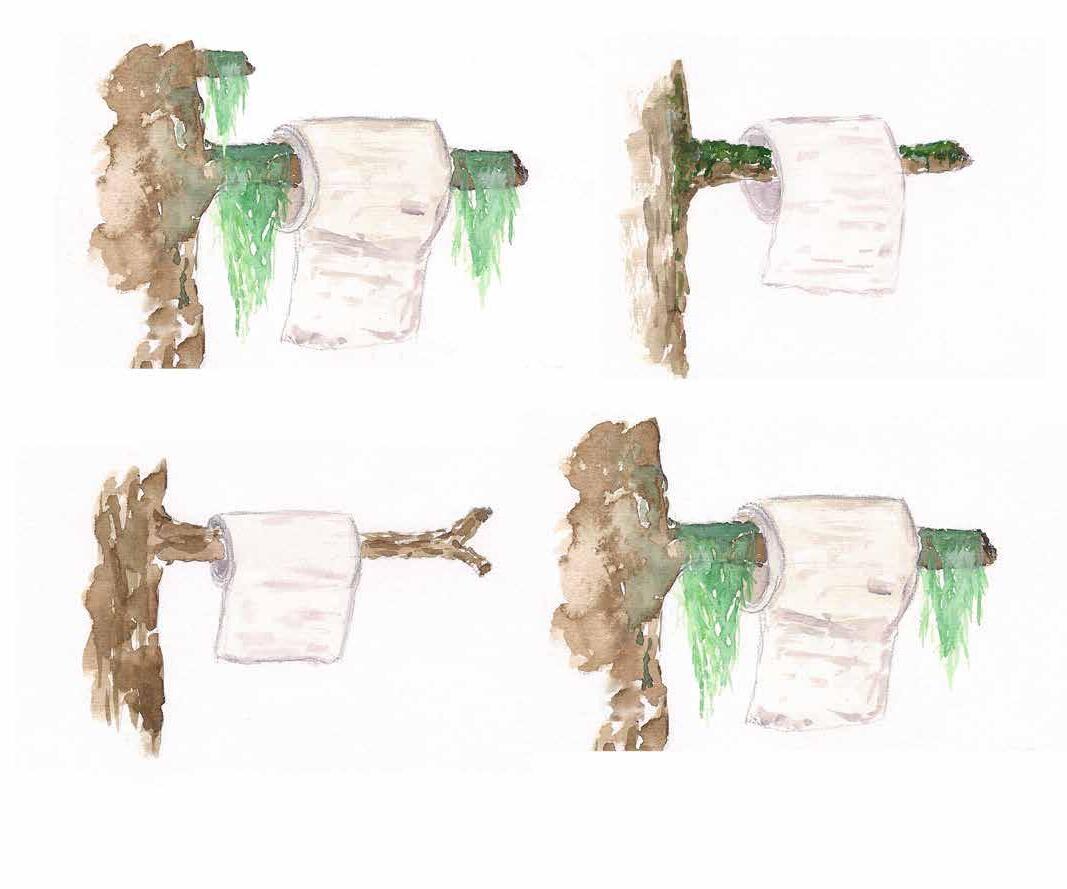

A pile of petrified human dung garnishing delicate alpine flowers. Clumps of rainpocked, off-white toilet paper sprinkled under an ancient cedar. Soft brown sludge oozing out from a strategically placed stone on a gravel bar. Or a soft-serve-esque steamer sunken neatly into the snow just off the skin track. None of these are acceptable ways to deal with your shit.

There is no excuse for behaviour like this in the wild frontcountry, backcountry— any-country. Leave No Trace (LNT) isn’t just for yuppies; it’s for anyone outside with a bladder and bowels. When we play outside (or live in a van), the goal is to have as small an impact on the environment as possible—footprints, ski/sled/bike tracks, that’s about it. When it comes to human effluence, LNT means preventing pollution and contamination, minimizing the chance of someone else finding your deposit and, most of all, maximizing the rate of decomposition.

But when you gotta go, you gotta go. So here’s how to (properly) shit in the woods:

Come prepared.

Think about where you’re heading to, how many people you’ll be with, and what will be the most appropriate way to manage your fecal matter. Refine your wastemanagement technique by determining the type of soil you will be fertilizing. If you’re in an arid, rocky or alpine zone or busy areas, pack it out. Biodegradable WAG (Waste Alleviation and Gelling) bags contain starches and gelling chemical crystals (similar to baby diapers) that allow you to pack out your solids—mess free and without impacting

HERE’S HOW...

the environment you’re traveling through. In less-trafficked places with rich soil, use a cathole (a hole dug into the ground to dispose of and cover up waste). If you have ample organic soil to bury your business, then here are the steps to follow:

Pick a spot.

Make sure it’s 60 metres away from water, trails and camp, and preferably doesn’t involve wrestling with tree roots or boulders. The softer the ground, the better.

Grab your weapon of choice.

A shovel is ideal, but if you’re feeling creative, a sturdy stick or rock will work in a pinch.

Dig deep.

Excavate a hole at least 15 to 20 centimetres deep (deeper is better) and wide/long enough to fit an average burrito. For larger groups, dig a latrine. When it comes to winter dumps, ideally dig till you hit ground so decomposition can happen faster. Otherwise find a spot well away from the trail and avoid exposed ridges where snow melts quickly, as your little gift will be visible come spring.

Take care of business/make a deposit. Do your business while enjoying the view and contemplating life’s big questions. Don’t even think of looking at your phone. That is wrong.

Manage the paperwork.

Don’t bury it. Burning isn’t always an option (always obey fire bans, also wet paper doesn’t burn well) so bag it, seal it and take it with you. Small paper bags work well to conceal any unsightly colours and filing them

neatly in a Ziplock bag keeps it water- and odour-proof. Double bag as needed. For those of you hardcore enough to go the moss, lichen, leaf, pinecone (!) or snowwiping route—props! Pro tip: Old man’s beard lichen is readily available,100 per cent biodegradable and has broad-spectrum antibacterial and immune-stimulating properties—it’s basically a spa treatment. And to the fancy pants crowd who use wet wipes…they DO NOT biodegrade—if you don’t pack ‘em out, you are a litterbug douche. Facts.

Fill the hole.

You’ve done your part, now cover it up like you were never there. Keeping a small bottle of hand sanitizer with the TP is a good practice— for you and any buddies you might high-five.

Leave a signature.

A small stick standing tall will let others know you’ve been there. But no rock flipping or major destruction—keep it classy.

Just remember: Human waste can pollute waterways, spread disease, disturb local flora and fauna—and leaves an ugly mess. By planning ahead, carrying tools (shovel, WAG bags etc.), and basically just giving a shit about how you treat the place you are visiting, you can minimize your impact. When in doubt (or a hurry), use the 60 rule: 60 m from water sources, 60 m from trails, 60 m from campsites. Leaving landmines for locals (human and/or animal) to find is guaranteed bad karma. The less you leave behind, the better person you are. And experimenting with natural wiping materials might just elevate the experience. Happy trails!

words :: Jon Turk

illustration :: Lani Imre

Planning a ski tour alone in unfamiliar terrain, I park the car, skin up and look around. The car might be hard to find at the end of the day, so I mark a waypoint on my Gaia GPS. Later, as the winter sun drops toward the horizon, friendly snow begs me to take one last run. As darkness sinks in, I pull out my phone and check Gaia. A dialogue box pops up: “To enhance your experience, we are updating your maps.”

Then the screen goes blank. And stays blank. Now where is the car, exactly?

When things go wrong—even little things—who survives? Who spends a night in a hole in the snow, and who dies?

So, as a trivial example, on that day my mapping program failed me, I had been staying aware of the landscape since I left the car. This awareness was not a chore or a task to complete, rather it’s what I do when I’m walking through the woods. It’s why I’m there. So, after swearing at the clueless programmers who shut my phone down, I traversed across the slope until I intersected my uptrack and made it back to the parking lot just before dark. No big deal.

And perhaps these observations are so obvious we don’t need to write about them, but I’m not done yet. I’m reading a book, We Are in the Middle of Forever, which interviews modern Indigenous teachers about a different order of survival—not that of an individual, but of humanity. And beyond humanity, a peaceful transition/survival for Mother Earth, from the polar bears to the butterflies. In the book, Ilarion Merculieff, a Unangan elder from the Bering Sea, argues that humanity has been taking the wrong track since people started thinking with their brains, not their hearts.

I traversed across the slope until I intersected my uptrack and made it back to the parking lot just before dark. No big deal.

My dear friend Bernice Notenboom is a survival consultant for a TV reality show called Alone Participants are sent out into the forest on their own with few tools, little gear and no food. Everyone forages for themselves and the person who stays out the longest wins.

In the last season, Bernice felt that two of the candidates were particularly strong. One was, Bernice told me, “a 50-year-old tree-hugging hippie who was positive about what Mother Nature was going to teach her.” The other was an organized, methodical, goaloriented man who was “determined to win.” Guess who lasted the longest? The hippie.

This should be no surprise because it brings up the old cliché of “It’s the journey, not the finish line.” On a real expedition, careful, methodical organization and planning are essential, but it’s awareness that keeps you alive. And it doesn’t do much good to suddenly realize that you need to be aware only after trouble looms. When you’re caught in an avalanche, somersaulting down the mountain at 100 kilometres per hour in a churning mass of snow, it’s obviously too late to start thinking seriously about the feelings and sounds of the snow under your skis.

Survival happens when you are aware all the time, even—especially—on those glorious days when the sun is shining, the powder is fresh, and the internet app told you that the snowpack is stable. Survival happens when you have accumulated a storehouse of knowledge before bad things start to happen.

And that storehouse of knowledge best accumulates when your journey is joyful, when you’re constantly watching, listening, learning from nature, observing the crystals growing outward on fir needles, seeking the wisdom and the language of those crystals.

When I was in Siberia, I met a few old people who grew up herding reindeer from their earliest infancy, with no urban interruptions. Reindeer herding is not a swashbuckling activity, no cowboy riding and roping. Instead, it’s a slow task of sitting and watching, listening for danger and becoming a quiet comforting presence for the deer—it’s thinking from the heart. When the Soviets took those reindeer herders’ children out of their nomadic camps and put them into schools (similar to the Canadian residential schools) and taught these children to think with their brains and not their hearts, the kids lost something vital. Modern herders told me that no one who was forced into the Soviet schools has the power and wisdom of those who spent their formative years in the camps, watching the deer.

We, children of our own schools, can never truly learn to think with our hearts—but we can journey in that direction.

And this story has a happy enough ending, as long as you don’t take me too seriously. Remember: The world isn’t always fair. Good deeds and noble thoughts are not always rewarded with rosy outcomes. I have too many friends who loved the wilderness, who were aware, alert and super-competent, but just got unlucky and didn’t survive. Buddha said it: Bad things happen to good people.

But maybe there is one guarantee. If you love the trees, act from your heart and travel through the wild spaces with your senses active and brain quiet, you will have a good life, however long you navigate the whims and ravages of this world. (Or at least have a shot at winning a reality TV show.)

Dr. Jon Turk is a scientist, author and National Geographic award-winning explorer. He spends his winters living in a van, biking and playing in the desert with his partner, Nina.

“It

– Amélie

words :: bronwyn preece

The intersection of athletics and the arts in the Sea to Sky corridor has long been established. The area boasts snowboarding painters, music-making mountain bikers, skiers who draw, climbers who craft with kilns and writers who wander outside the margins. Art, sport and life are inextricable for some, while for others artistic expression and sport may serve as a counterbalance. But what happens when the mix—the balance—is thrown off? What happens in the case of injury?

Often known as “the backcountry poet,” I am a solo hiker who was rescued off the Great Divide Trail in 2023 with acute tendinitis in both feet. Unable to walk, dangling from the long line of a helicopter, my hike-and-write dream was vanishing into thin air. Committed to a signed book contract chronicling the trek, I devised a plan to salvage both the athletic and artistic endeavour by taking a creative approach to my rehab. I “completed” the hike by bike, driving a stationary exercise cycle to power through my planned daily kilometres at some of the more scenic and popular spots of the aborted route. From bipedal to by pedal—now surrounded by flocks of tourists—my remote, solo venture suddenly turned into a piece of very public performance art.

Following the project’s lemons-to-lemonade approach, I became curious about Coast Mountain-connected artist/athletes and how their art may have refocused, redeveloped or responded to an injury. What role does creativity play in the rehabilitative process?

Spearheaded by Squamish physiotherapist Emma Clark, the Skill Shift Collective hosts monthly workshops to provide “low-barrier, inclusive spaces to teach non-active skills to injured athletes [and outdoor recreationalists] with the goal of creating community and social connections.”

Emma has been facilitating these gatherings, partially funded by the Squamish Arts Council, for more than a year. Each meetup is led by a different guest expert representing a range of artistic genres. Interested in sports psychology, Emma attests to the inherently therapeutic benefits of these sessions yet insists they are not therapy.

Instead, participants relax into neighbourly chitchat as they learn new creative skills or hone existing techniques. “Social isolation is one of the biggest things I see in my patients post-injury, particularly if they are adventure athletes,” she says. “The Skill Shift Collective allows people to connect and tell their stories through another creative medium that, while less physical in nature, can be just as powerful.” Tales are shared of resilience and recoveries—connectivity being drawn out and opened up through artistic expression.

Downtime can plow our deepest depths. Sidelined by injuries, professional skier, surfer, climber, photographer and guide Chad Sayers began working on his book Overexposure: A Story about a Skier. Chad reflects on recovery by saying it can be a time when you’re “more sensitive and emotional as you start working on yourself. It’s finding a way to stay connected with your passion and career while healing.”

For Chad, one of the most photographed skiers in history, “Writing my book is an example of my healing journey and how I was processing/dealing with it.” He notes this space can be productive, authentic and artistic, saying, “Spending time with what makes you happy” is an integral part of the process.

Spending time with what makes him happy is exactly what celebrated local DJ Mat the Alien did to keep his spirits up following a devastating mountain biking accident in 2020 that rendered him a quadriplegic. Mat’s friends outfitted his room at GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre with music-making gear, and the iconic DJ tasked himself with creating new tracks without the otherworldly hand dexterity and scratching skills he was known for.

“Often, I’d be spinning a record with one arm and pushing forward with the other to stop from falling onto the tables,” he says. In 2023 Mat received a grant to produce and release This Sound, a four-song vinyl record recorded from his Squamish home on his 270-degree adaptive Alien music control panel. He’s also returned to the stage but, limited by accessibility and logistical considerations, now only plays annual gigs at the Bass Coast and Shambhala festivals.

Mat views music and his love of biking (which he’s been able to return to) and snowboarding (which he has hopes for) as meditations or puzzles that invite him to find creative ways to navigate through the many “dodgy places” of a life-changing injury. DJing provides Mat a way to stay connected with community—his creative backbone and a necessary means of support through the continued challenges.

Facing challenge is equally familiar to acclaimed two-time Olympic snowboarder and visual/music artist Trevor “Trouble” Andrew, who is also the designer behind the GucciGhost line of street fashion.

Forced sedentary by a torn ACL, Trevor found an artistic antidote to the boredom. He recorded an album and his “lo-fi, grimy, darker” sound got him signed to the Virgin record label. Once able to return to his board, he began to ride a continuum of creativity between sport and art. Painting and illustration soon, too, began to emerge as outlets, earmarked by his gritty, bright and fun graffiti style. For Trevor, “It’s a way of life…being creative with your environment.”

Broken ribs followed by a fractured back eventually forced his retirement from professional competition, but Trevor says, “Snowboarding is still very much a part of my art.” In 2016, his renegade GucciGhost artwork caught the eye of the famed fashion house it was based on, and his designs spurred a sudden haute couture culture jam, from halfpipe to catwalk. Recently, Trevor detailed the jacket for Mat the Alien’s summer Bass Coast appearance and spray-painted trench coats for Usher on his latest tour. His art

is featured in international galleries, and he continues to produce new music. Trevor also returns routinely to the Sea to Sky slopes, reminding us, “It’s about following your drive and passion.”

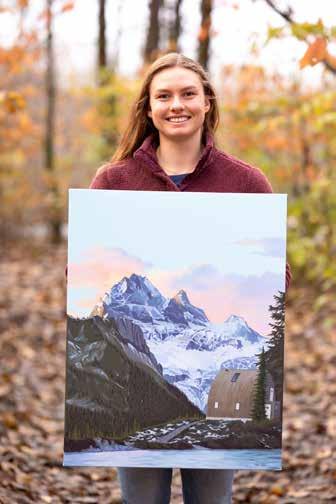

Olympic ski cross racer India Sherret reflects, “Being in the mountains is a spiritual experience” and says painting is a contemplative mechanism for self-discovery. For India, visual art is also an intentional outlet to alleviate the high stress of World Cup competition. The skier’s interest in painting was encouraged when, as a teenager, she underwent residential treatment for bulimia—art therapies were integral to the rehabilitation program. India found herself painting again while healing a broken back in 2018, a torn ACL a few years later, and as a way of processing the loss of her 2022 Olympic dream, which was foiled by a crash. “It’s about connection… creating stuff helped me go through it.”

Refocused, India recently acquired a studio space and took the gold medal at the first FIS Ski Cross World Cup of the season in December 2024. She now has her sights set on the 2026 Olympics.

And all-around shredder/painter Vanessa “Nes” Stark says of her journey: “After 33 years of snowboarding, I’ve had to deal with a few handfuls of injuries and ten surgeries.” She adds that immersing herself in art helped her with the mental challenges and tolls recuperation can take. Injury can be a place of extreme vulnerability and being hurt can be a lonely place. “Art thrives on melancholy,” she says. “It can be like a warm hug on a cold day that will listen wordlessly as the painting appears.”

Injury can thwart dreams, create setbacks and force us to interrogate our sense of self. But in the same breath, those difficult downtimes may offer up invitations for inspiration. For some, injury (though unwelcome) has not been met as a dead end, but as an opportunity—opening the doors of art-making, of rejuvenation, of expression… of creative rehabilitation.

Homemade (and healthier) ultralight meals

words :: Feet Banks

For most of us, it started with those little pouches of instant oatmeal—the gateway drug to “just add water” lightweight food for hiking or touring trips where every ounce mattered. From there, it didn’t take long to realize those (pricey) freeze-dried/dehydrated meals lining the shelves at your local outdoor shop were not only light and easy, some of them weren’t half-bad tasting either. And no pots to scrub.

The trick to those bagged meals is to ensure you have a longhandled spork able to reach right to the bottom of the pouch so you can stir the meal without getting it on the sleeve of your jacket. The other trick is to bring a small container of cracked chili peppers or some fresh cilantro (if you don’t hate it) to turn the blasé into gourmet.

But the real trick is to just make your own.

“Anyone can do it, but there’s trial and error,” says Miléna Georgeault, co-owner and head chef for Terre Boréale, a Yukon-based adventure tour operator that provides only homemade, DIY, dehydrated meals for their clients. “At first, we tried dehydrating tomatoes and mushrooms and eggs, but it was disgusting. The eggs didn’t work for us. But lasagna did; it’s the same recipe I use at home with just a bit less oil.”

As one of the few (only?) B-Corp-rated tourism operators in Canada, Terre Boréale prefers homemade dehydrated meals because it helps them reduce both waste and the impacts of shipping, and it allows them to provide their guests with local ingredients. Clients say it just tastes better.

Miléna says there is definitely a learning curve to what recipes work best (try lasagna), but that any standard food dehydrator is good enough to start. Here are a few dehydration tips she’s learned along the way. Have fun!

1. Spread your fully cooked preparation into a thin layer on the dehydrator trays. For thicker dishes like lasagna and cannelloni, cut them into small bites before spreading on the tray.

2. Set your dehydrator according to your manual and let it dehydrate for fifteen hours or until all pieces are completely dry.

3. Store in an airtight container and away from light for up to six months, or place in the freezer for longer periods.

Plan for about 180 grams of dry mix per person for your portions. For a more precise measurement, estimate the number of portions your dish will serve prior to dehydration.

1. Boil enough water to cover the dry mix or, for more precise measurements, weigh your food before and after dehydration—the difference will determine the amount of water to add. (Takes a bit of math beforehand, but this kind of precision makes for a better meal.)

2. Add the dehydrated mix to the boiling water and bring the whole thing back up to a boil. Then remove it from the heat and place the pot in an insulated cover (see next step).

3. To reduce fuel consumption and optimize rehydration we use custom-made insulated pot covers for our cooking pots. We make them out of bubble insulation and duct tape. Once the pot is off the stove, slide it in the cover and let it rehydrate for 15 to 20 minutes. The insulated pot also makes a great lap-warmer for whomever is holding it.

4. If needed, you can add a bit more water and warm everything again on low heat. (Remove the pot from the insulated cover before putting it back on the stove.)

“Give it a try,” Miléna says. “It’s a great way to have better food and use less plastic. But if you are using rice, don’t use regular rice. Use Minute Rice—it works great.”

Whistler local combines top-tier cosmetic science with spiritual-based beauty processes

words :: Feet Banks

As a middle-aged dude living the Mountain Lifer dream, I contribute very little to the $570-billion-a-year beauty industry. I mean, do whatever makes you feel good. But for me, drinking lots of water seems easier, cheaper (and less batshit crazy) than something like the new hot beauty trend of salmon-sperm facial injections. (And please tell me they aren’t using farmed salmon.)

But medical intuitive and Whistler local Lily Chandra wins me over to the idea of skin care pretty quickly with a common-sense, mountain-fueled philosophy.

“My secret to beauty is not complicated,” Lily says. “Fall in love with yourself. Know who you are and be who you are. When you are happy, that is the beauty you project into the world, and that is what happens to you. We’ve all seen people who just radiate—it comes from within.”

With more than fifteen years of experience in the self-care industry, Lily’s Cosmetic Energy healing facials harness people’s own energy—along with that of herself and the greater cosmos—to help rejuvenate the skin and heal blemishes on a cellular level. She explains this while rubbing one of her Divine Rose skincare creams into the thought lines on my forehead and the crow’s feet by my eyes.

Lily’s signature line of Brahmi products— face cream, magic balm and lip plumper—are all organic and plant-based with no fillers, no added water and are professionally lab-made in Canada. “They can compete with any high-end products out there,” she says, “but I also meditate with each product before I ship it. I say a mantra and give them the sacred frequency to help fuel the self-love, but they are also just top-tier great products for your skin. The energy is in the product, but the science is there, too.”

Born on BC’s Sunshine Coast and raised in Vancouver by immigrant parents,

Lily connected with the mountains at an early age. “We grew up skiing. My family bought our first Whistler property in 1991, and I bought a place and moved here in 2021. There’s just something about these mountains.”

One thing about the mountains, though: They can be hard on our skin. “We get weathered,” Lily says. “All the wind and the sun and the dry cold. So many people are walking around up here with dry skin and it’s not good for you. Your skin is the largest organ in the body. If you have a damaged skin barrier, toxins and allergens can easily enter the body. This may cause chronic skin conditions like acne, eczema and psoriasis.”

After my session in Lily’s Whistler studio (with incredible views of Wedge Mountain and the Armchair Glacier), my skin did indeed seem to have more radiance and glow. The lines on the outer edges of my eyes still appeared when I laughed, but there’s nothing wrong with laughing, is there? Nor squinting to take in a mountain

sunset—if it makes you happy, it probably makes you beautiful, too.

And if not, autumn of 2025 will see strong pink salmon returns in Squamish. See you at the river, fellas. There will be plenty of fish sperm for everyone!

Beyond her in-person facials and shipanywhere beauty products, Lily also offers a line of meditation-guided organic (and delicious) teas to help set your intentions, manifest your dreams and feel/look your best. www.brahmiskincarewhistler.com

Discover the unique magic of spring in Whistler. With a captivating blend of winter wonder, sun soaked slopes, and an après-ski scene that is electric, spring in Whistler isn’t just about warmer weather — it’s a whole new adventure.

Our iconic two-MICHELIN Key hotel puts you right in the heart of it all with seamless ski-in, ski-out access to Whistler Blackcomb, Condé Nast Traveler’s #1 Ski Resort in North America.

This spring elevate your escape. Special memories start here.

SAVE UP TO 20%

Our award-winning dining venues are vibrant hubs of connection for those celebrating a special occasion or simply seeking a memorable culinary experience.

From leisurely breakfasts, to romantic dinners, and unforgettable après, every moment at Fairmont Chateau Whistler is an opportunity to create lasting memories. Discover the true spirit of Whistler hospitality, and book your table today.