It’s time to get your ducks in a row!

“Typography, the art of designing with type, is probably the most important subject students will study in school. As professional graphic designers they will be called upon to perform many design tasks, most requiring a thorough knowledge of typography.

Few assignments will be devoid of type, and many will consist entirely of type. Words will always remain central to communication.”

Designing With Type by James Craig (2006)Introducktion

Anatomy of Type

Apex Bowl Serif Diagonal Stroke Bracket Horizontal Stroke or CrossbarLow to Moderate Contrast, Angled Stress

Humanist Serif

Typeface shown: EB Garamond

The first roman typefaces following centuries of handwritten forms. Humanist serifs have close ties to calligraphy. An oblique stress, gradually modulating from thick to thin, shows evidence of a pen held at a consistent angle.

Moderate to High Contrast, Vertical Stress

Calligraphic Terminals

That angle is often echoed in letters topped with calligraphic terminals and finished with asymmetrical serifs that gently transition from the stem.

Humanist Serif

Typeface shown: Bodoni

Ball Terminals Upturned

At the opposite end of the spectrum from the Humanists. Rational serifs have a strong, vertical contrast between thick vertical stems and fine horizontal hairlines.

Because these typefaces are not so much written as constructed, their letterforms are very even in proportion and structure. Serifs are generally symmetrical, and can be bracketed, like Melior and Miller, or thin and abrupt, like the Didones (Bodoni and Didot).

Transitional Serif

Typeface shown: Times New Roman

As we move further away from type’s calligraphic roots, contrast increases and the stress axis turns more upright and variable within each typeface rather than staying consistent as it does in the Humanist serifs.

Letters in these typefaces are more regular in shape and proportion and apertures are slightly smaller. Transitional serifs still have a gradual, bracketed transition from the stem, and terminals are often bulbous.

Contemporary Serif

Typeface shown: Karmina

In the last forty years, type designers have borrowed the most pragmatic aspects of the previous styles to develop a new breed of highly functional Text faces, designed to solve the problems of various substrates and reading environments. These designs generally sport a much larger x-height and lower stroke contrast than traditional serif typefaces, but are otherwise not directly related. They range from the spatially economical Swift to the informal and energetic Doko.

Inscribed/Engraved

Typeface shown: Avara

Grotesque Sans

Typeface shown: Asap

When sans serif printing type first appeared in the early to mid-1800s, some found the style so strange they called it grotesque.

Gothic Sans

Typeface shown: News Gothic STD

These typefaces kept the nickname even after they gained popularity and Grotesque (or Grotesk in German-speakers) is now associated with any sans serif in this early style. The characteristics of Grotesque typefaces are similar to those of the Transitional and Rational serifs: regular proportions, relatively static forms based on the oval and fairly closed apertures, with some strokes turning inward.

Some English and American variants of the Grotesque style are known as Gothics. While the differences are sometimes in name alone, there are a few distinctions that can be drawn. These include a large x-height, forms that are simpler and more static, very low contrast, and often a condensed width with an upright stance derived from flat-sided rounds.

Geometric Sans

Typeface shown: Futura PT

Flared Strokes Narrow ‘R’ from Classical Capital Proportions Minimal Contrast Round Shapes are Nearly Circular Single-Story ‘a’ is common Shapes are ChiseledUnlike the other serif styles, derived from the stroke of a pen or brush, the typefaces in this category have a closer relationship to letters that are carved or chiselled from stone (also known as Glyphic), or engraved on a hard surface like copper or steel. These typefaces can end their strokes with long, graceful serifs (Trajan), sharp wedge serifs (Modesto) or no serif at all, but a thickening flare instead (Albertus).

Neo-Grotesque Sans

Typeface shown: Roc Grotesk

Neo-Grotesques (Neo-Grotesk in Germanspeaking parts of Europe) are even more rationalised extensions of the Grotesque style. These typefaces, pioneered by Helvetica and Univers, have very little stroke contrast, horizontal terminals and quite closed apertures. Their homogenized forms are graphically appealing at large sizes, so they often fare better in Display settings.

Minimal Contrast Vertical Stress

Typefaces like DIN—designed by engineers for industrial use—could be considered Geometric sans serifs but also share many traits with these Gothics.

Simple, double-story ‘a’ with diagonally oriented bowl and no tail

Straight Leg ‘g’ is commonly a binocular form

The most static and clinical of all the classifications. Geometric sans serifs are constructed out of geometric forms with round parts that are circular or square. It’s important to note that, while shapes like the ‘o’ appear to be exactly round, most proper typefaces do not contain perfect circles, but are optically corrected to appear as round as possible while harmonious with other letters. Geometrics have minimal stroke contrast, and italics are commonly slanted versions of the romans rather than cursive in form.

Humanist Sans

Typeface shown: Cronos Pro

Like their serif counterparts, Humanist sans serifs have roots in calligraphy.

Their round, dynamic, open forms have higher stroke contrast than the other sans serif classifications (though not as much as most serifs).

These typefaces sometimes share the binocular ‘g’ and variable letter widths of their serif sisters.

Their italics are true italics with cursive forms of ‘a,’ ‘g,’ ‘e,’ and sometimes a descending ‘f.’

That angle is often echoed in letters topped with calligraphic terminals and finished with asymmetrical serifs that gently transition from the stem.

Grotesque Slab

Typeface shown: Clarendon URW

If one were to weigh the typical example of each classification, these bulky beasts would tip the scale furthest.

Although they aren’t simply Grotesque sans serifs with slab serifs slapped on, these typefaces reflect the proportions, structure, and stroke contrast of their serif-less counterparts. Ball terminals are common among Grotesque

slabs, as are heavy bracketed serifs and closed apertures. The effect of these attention grabbers can be decorative and eye-catching, and is usually very bold.

Round Shapes are Circular

Neo-Humanist Sans

Typeface shown: Meta Headline Pro

The digital era gave birth to new sans serifs that share characteristics with other classifications but are individual enough to deserve a label of their own.

Many of these have a dynamic structure that could be considered an evolution of the Humanist sans, but stroke contrast is reduced and apertures are even more

open. The round shapes of typefaces in this category tend to be more square than their predecessors and x-heights are larger on the whole. Letters in these typefaces are more regular in shape and proportion and

apertures are slightly smaller. Transitional serifs still have a gradual, bracketed transition from the stem, and terminals are often bulbous.

Geometric Slab

Typeface shown: Josefin Slab

These slab serifs share the geometrically round or square shapes of their sans counterparts. Rectangular serifs are unbracketed and generally the same weight as the sterns.

Unbracketed Serifs

Minimal Contrast, Only Visible at Junctions

In fact, all strokes are essentially of the same weight, lacking any perceptible contrast. The ‘R’ leg is a straight diagonal and ‘g’ is normally of the monocular form.

Minimal Contrast

Script

Most scripts are slanted. Slant can vary throughout the typeface.

Formal scripts usually have a consistent angle.

Typeface shown: Vladimir Script

Traditionally, a script typeface emulates handwriting, whether its letters are a graceful, connected cursive or the staccato scribbles of a daily shopping list.

Besides formal and informal categories. scripts can also be sorted by the writing tool, such as pen or brush. Script fonts have become increasingly sophisticated in recent years thanks to technical developments like OpenType.

Discretionary ligatures and contextual alternatives yield a more convincing emulation of real handwriting and offer a variety of decorative options.

Humanist Slab

Typeface shown: Adelle

Put simply, you could take a Humanist sans serif and add unbracketed, rectangular serifs and get pretty close to a Humanist slab.

These typefaces often have less stroke contrast than their sans counterparts, and the serifs are sometimes wedge shaped.

Counter- Any interior shape ofa glyph It can be completely enclosed by strokes, such as the eye of an‘e ’ Foundry- A company that designs, manufactures, and /or distributes fonts.

berepresented by different glyphs.

Aperture- The opening ofa counter to the exterior of a glyph. Bracket- Acurvedor diagonal transition between a serif and main stroke. Character- The basic unitof written language. Can be a letter, a number , punctuation, or symbol. Cursive- A style associated with handwriting, typified by slanted stems with curved tails.

Glyph- The graphical representationofacharacter

Font- A collection of glyphs. The fontisthedelivery mechanism, represented by a digital file or a set of metalpieces, for a typeface.

Humanist- A method of letter construction tied to handwritten strokesmade with a pen or brush.

andcan also have alternate forms, suchassingle—and double—story‘a’s or an ‘a’ with a swash tail. In this way, a single character can

. A font can contain several glyphs for each letter— a lowercase ‘a’and small cap ‘A’

Ligature- A single glyph made of multiple characters. The most common examples are functional (Standard), such as ‘fi,’ which is designed to

resolve excessive spacing or an unpleasant overlap of two letters. There are also ornamental (discretionary) ligatures, such as ‘st.’ that are primarily a stylistic option.

Rational- A method of letter construction using shapes that are drawn as opposed to written

Sans serif- A character or typeface without serifs

Serif- A small mark or foot at the end of a stroke. Serifs are lighter than their associated strokes.

Slab serif- Aheavy serif, typically rectangularin shape, with a blunt end. Itis alsoatypeface classification.

Stroke- An essential line or structural element of a glyph. The term derives from the stroke of a pen.

Stroke contrast- The weight differencebetween light and heavy strokes.

Style- A stylistic member (e.g. bold,italic, condensed) of a typ eface family, typically represented

on the digital screens of desktop computers, tablets, and mobile phones

Substrate- The surface material on which type appears. For hundreds of years, type was printed on paper. Now it is increasingly rendedered on

Swash: The extension of a stroke or prominent ornamental addition to a glyph, typically used for decorative purposes.

Typeface- The designofasetofcharacters.

Weight- Thethicknessofastroke. In type design, the geometry of a line (or

using the terminologyofweight .

In simple terms, the typeface is

whatyousee

andthefont.

shape)isusuallydescribed

Rules ofTypography

The

four most important things

Avoid goofy fonts PLEASE!

One of the easiest ways to improve your typography is to use a professional font!

Steer clear of most free fonts available.

System fonts like Times New Roman and Arial (especially Arial) aren’t all they’re quacked up to be.

And try not to use monospaced fonts if you can.

What’s the difference between quotation marks and inch marks?

Butterick says, “Use curly quotes for quotation marks.”

However, foot and inch marks are straight like in this sentence: Did you know the average pekin duck is 1'8" tall?

And don’t forget, apostrophes point downward!

Paragraph and Section Marks

¶ Make sure to use a nonbreaking space after § paragraph and section marks!

Use correct trademark and copyright symbols!

Practical Typography © 2010–23

Symbols & Punctuation

Use ampersands sparingly (unless included in a proper name).

And when using ellipses…

Use the actual character like the one above.

Don’t just use some periods and call it good. . .

And don’t forget exclamation points!

Butterick claims that one (1!) exclamation point is plenty! (for a document longer than three pages!)

Hyphen vs. Dash

- - - - - - - - - - — — —

Don’t use hyphens for a dash -Yeah, don’t do that. You’ll regret it.

Indentation

Use first-line indents that are 1-4x the point size of the text or use 4-10 points of space between paragraphs.

Don’t use both. According to Butterick, The worst way to put space between paragraphs is to insert an extra carriage return. It can have little affect.

Getting Rags Right

A rag is the name of the irregular edge of a block of text. Usually the right side of the test is the “rag.” Many type designers will go in an manually edit their rags for aesthetic appeal.

One general rule is to avoid having a rag that appears to make any obvious shapes. Avoid creating slopes with rags.

A good rule of thumb is to have a long line ollowed by a short line that is followed by another short line... then another long line.

Line Lengths

The average line length should be 45-90 characters (including spaces).

Lines of type should be comfy to read.

If a line is too short it breaks up your text.

If your line is too long, the reader is going to have to search for the beginning of each line which can be

Line and Paragraph

Orphans and Widows exhausting.

That’s an orphan, a poor little duckling left alone.

And that’s a widow.

Use bold or italic as little as possible, and never use them together.

Never underline!

You might use underlining for links, though.

Le Monde Courrier Std Regular

ALL CAPS ARE FINE

(for like less than one line of text. Otherwise, it’ll probably hurt your eyes)

Le Monde Courrier Std Bold

Le Monde Courrier Std Bold Italic

Le Monde Courrier Std Book

Le Monde Courrier Std Regular

Le Monde Courrier Std Book Italic

Make sure to use 5-12% extra letterspacing with ALL CAPS and small caps.

Small CapS

If you don’t have real small caps, don’t use them at all!

Just look at those buggy small caps In the subheadIng.

Le Monde Courrier Std Regular Italic

Rules for Leading

Line spacing (leading) should be 120-145% of the point size! In other words, leading should be 4 points higher than point size.

This is really bad leading or line spacing. According to Designing with Type by James Craig, readability is generally improved by increasing the leading or linespacing.

And this might be too much leading.

“Excessive leading,” Craig claims can cause lines to “drift apart” and feel disconnected.

Linespacing/Leading

Only one space between sentences. Please. Don’t put multiple white--space characters in a row.

Rules for Tracking

Tracking determines the amount of space between the characters or letters.

Craig claims that inconsistent tracking/letterspacing can be pretty distracting for readers.

Tracking can drastically impact readability according to Craig. Like this is ridiculous.

Rules for Kerning

Kerning should ALWAYS be turned on. Generally, it’s a good idea to use optical kerning, but sometimes you will need to go in and kern letter combos individually.

This is type with bad kerning.

Letterspacing/Tracking & Kerning

Left Aligned

In the English language, we read from left to right. The general rule is to use left-aligned text whenever possible because it is the easiest to for to read. Use left-aligned for long chunks of text or paragraphs and most body copy.

Right Aligned

Right-aligned text is much more difficult to read when used for several lines of text or body copy. It forces the eye to search for the beginning of the line because the rag is on the left where the reader will start on each line.

When using centered text both sides of the text will be uneven and have rags. Someone once said that centered text is for weddings and funerals, so use it sparingly.

Centered Justified

Justified type makes it so that each line of text is the same length. The text will align on both sides of the text. Justified type can have its downsides, sometimes leading to awkward wordspacing. Always use hyphenation!

Alignment

Type

Designers

Linn Boyd Benton (1844–1932) was born in the United States at Little Falls, NJ, at a time when type designers were expirimenting with many forms of typographic expression, often to satisfy the needs of advertisers. Merchants wanted typefaces that were new, big, and eye-catching.

The type designers rose to the challenge, producing the wildest assortment of typefaces ever seen—from condensed to expanded, from simple to elaborate. One of the more popular typestyles to emerge was Egyptian, also referred to as slab serif or square serif.

Benton is also credited with the invention of the pantographic punch cutter, which revolutionized type production.

31.

Linn Boyd BentonCentury, the first major American typeface, was designed in 1894 by Linn Boyd Benton for Theodore Lowe DeVinne, the printer of The Century Magazine. After Bodoni, type designers began to search for new forms of typographic expression. Around 1815, a typestyle appeared that was characterized by thick slab serifs and thick main strokes with little contrast between the thicks and thins. This style was called Egyptian. Century Expanded is an excellent example of a refined Egyptian, or slab serif, typeface. The large x-height and simple forms combine to make this a very legible typeface.

Mariela Monsalve

Mariela Monsalve was born in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She studied graphic design at the University of Buenos Aires (FADU) for her bachelor’s degree. She then went on to receive her master’s degree at the Royal Academy of Art in the Netherlands. She has taught about letter making and typography at the University of Buenos Aires (FADU) and the National University of Arts (UNA), a public liberal arts college in Buenos Aires. She creates art installations with a group called Defrenéticas.

Asul

Joshua Darden was born in 1979 in Northridge, California. He designed his first typeface when he was 15. According to Fonts in Use, Darden became the first known African American type designer. He later founded the Darden typography studio in 2004. He has since created several critically acclaimed typefaces. Darden has also taught at several schools across the United States including University of California, Santa Barbara.

He is most known for the Freight font family, which has over 120 fonts in total. Writers at Typographica called Freight one of their favorite typefaces of 2005. Before Freight, Joshua Darden had worked on and designed 10 other fonts. Between 1995 and 2017, Darden released around 19 different typeface families.

Joshua Darden

5 Classic Typefaces

Century CENTURY

This was the first assignment for ART 222. It was a simple project that allowed me to refresh on the basics of letterspacing, wordspacing, linespacing, and readability. The five classic typefaces I was allowed to work with were Garamond, Baskerville, Bodoni, Century, and Arial.

Type Arrangements

Type Arrangements was the second project of the class. This project encouraged me to play around with the tools I already know and also learn a couple of new things. Using the same five typefaces as the previous project, I explored messing with shapes, alignment, opacity, layering, and more to create interesting and unique layouts using type.

Graphic Arts

The purpose of this project was to kind of pull back on the reins and utilize a grid to create structure and a sense of balance. This time, I also had to take images into account, rather than just using text.

The Anatomy of Type & Classifications

This was one of my favorite assignments because it allowed me to start working in color. The purpose was to get familiar with the names for different parts of letters and glyphs and other key terms.

Historical Event Poster

JUNE 1983

This was my favorite project of the semester. The purpose was to create a poster about a historical event using only type. I created every graphic element using only glyphs in the two typefaces I chose to use.

I ended up creating a triptych of three posters that provide details about the STS-7 mission that made Sally Ride the first American woman to travel to space in 1983.

I based my design off of NASA posters from the 70s and 80s to capture the vibe of the time period.

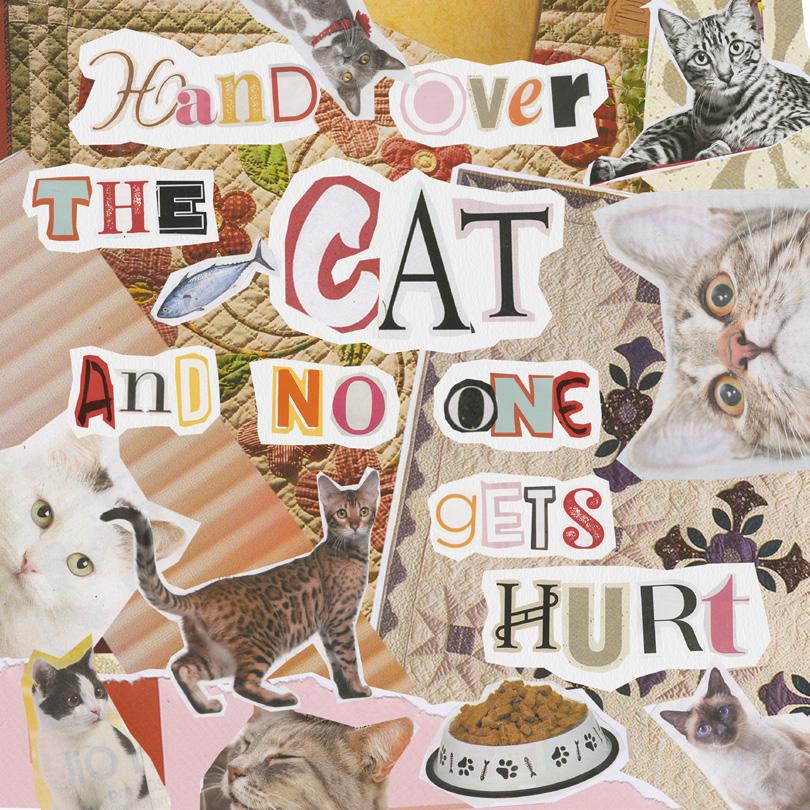

Ransom Note Collage

The goal for this project was to get a little crazy in Photoshop. I cut up several magazines with the goal of creating a collage with a crazy cat lady aesthetic. I chose to cut out pictures of quilts and plenty of cats, sticking to a warm color palette. I then used Photoshop to put everything together to spell out the message “ Hand over the cat and no one gets hurt.”

Content

Designing with Type: The Essential Guide to Typography Fifth Edition by James Craig

The Anatomy of Type by Stephen Coles

“Joshua Darden” by Wikipedia

“The Darden Studio” (dardenstudio.com)

“muk monsalve” (domestika.org)

“Muk Monsalve” by Future Fonts

“Mariela Monsalve” by Identifont

Type

Le Monde Courrier

Chaloops

FreightSans Pro

Century Old Style

Asul

Bubblegum Pop

OCR A Std

Times New Roman

Arial

Design

Madilyn Sleight