The Ted and Judy Harmon Collection Exhibit at the Havre de Grace Decoy Museum

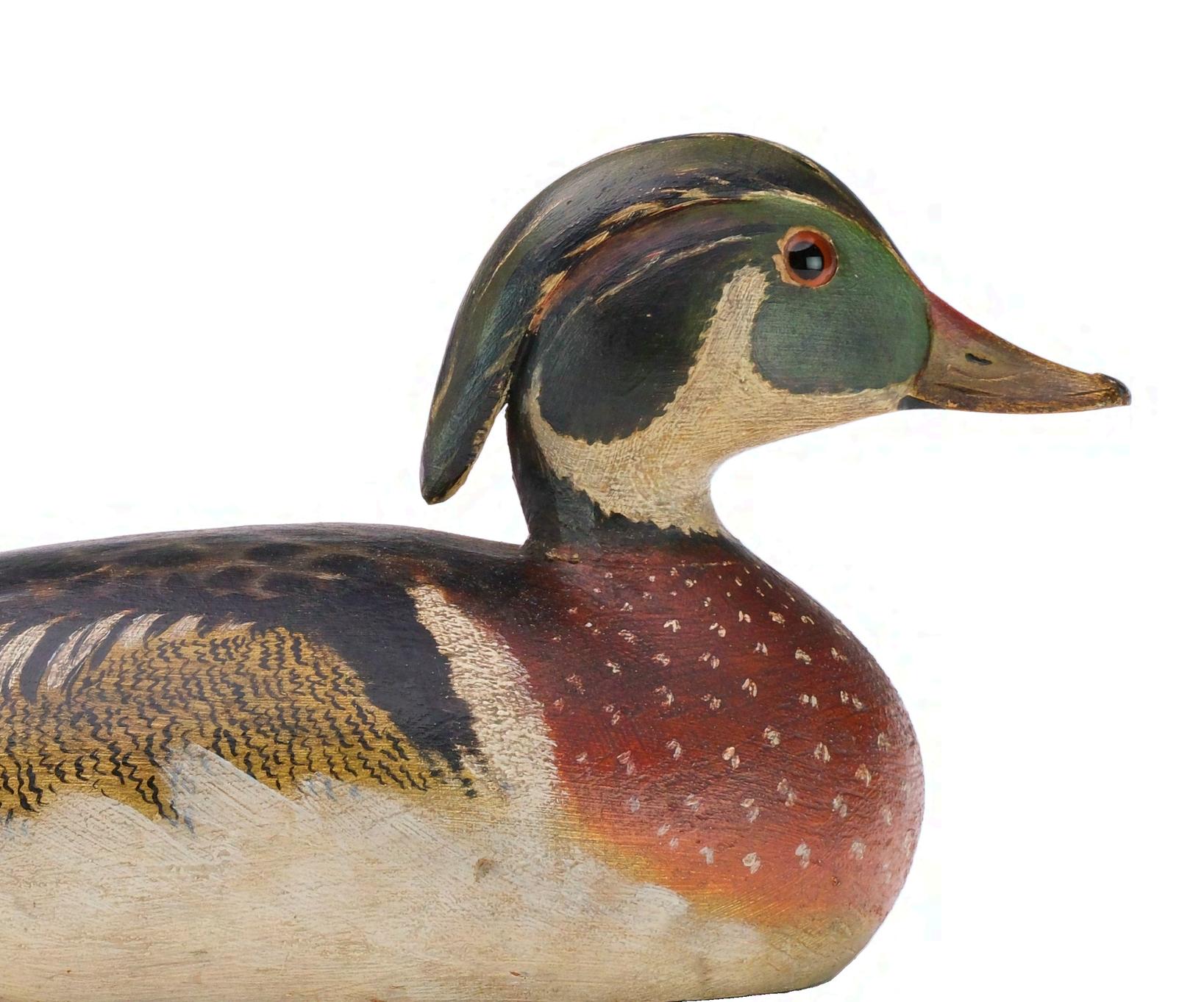

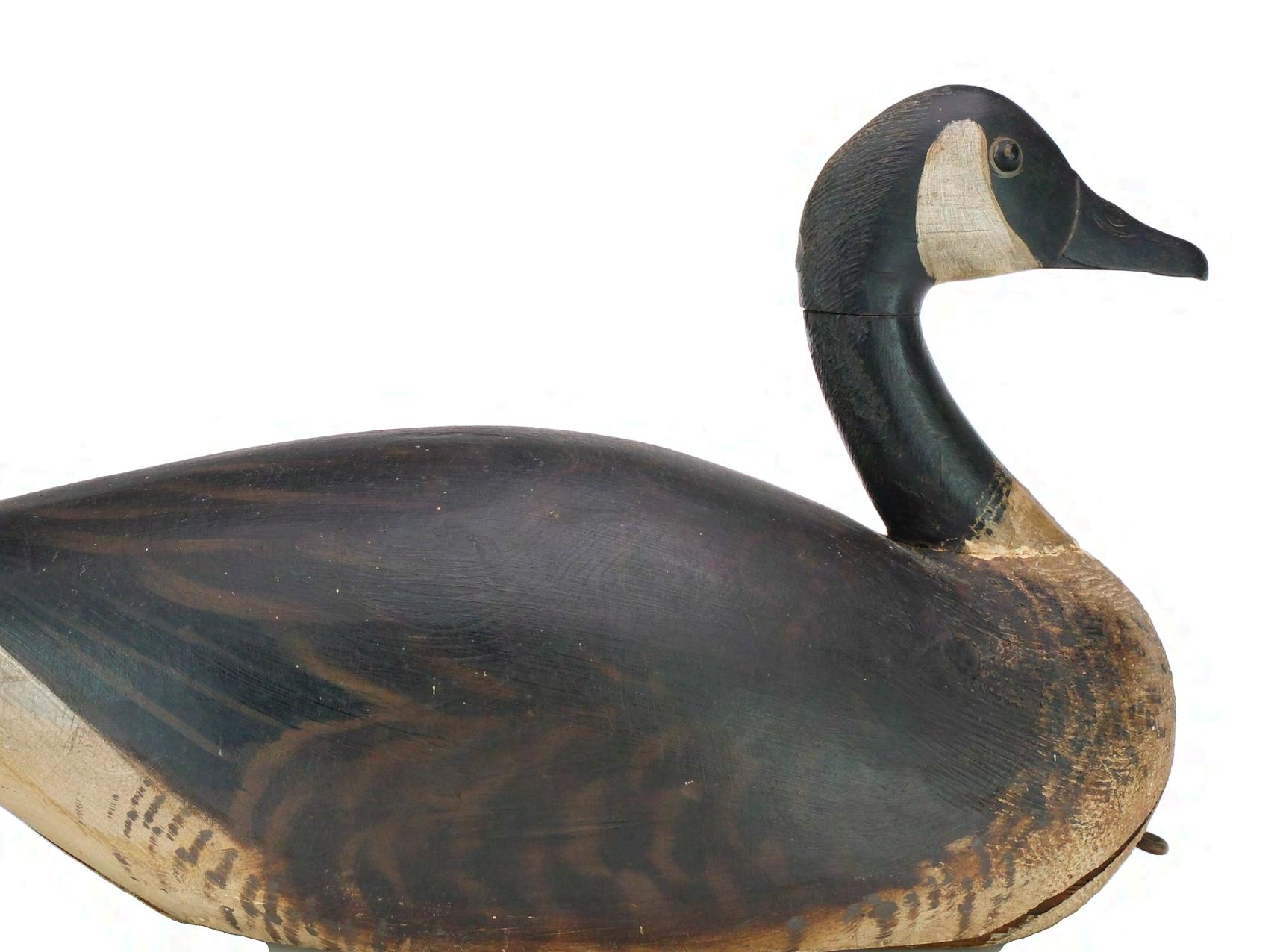

A passion for collecting the finest Massachusetts decoys for over six decades

The Ted and Judy Harmon Collection Exhibit at the Havre de Grace Decoy Museum

A passion for collecting the finest Massachusetts decoys for over six decades

A passion for collecting the finest Massachusetts decoys for over six decades

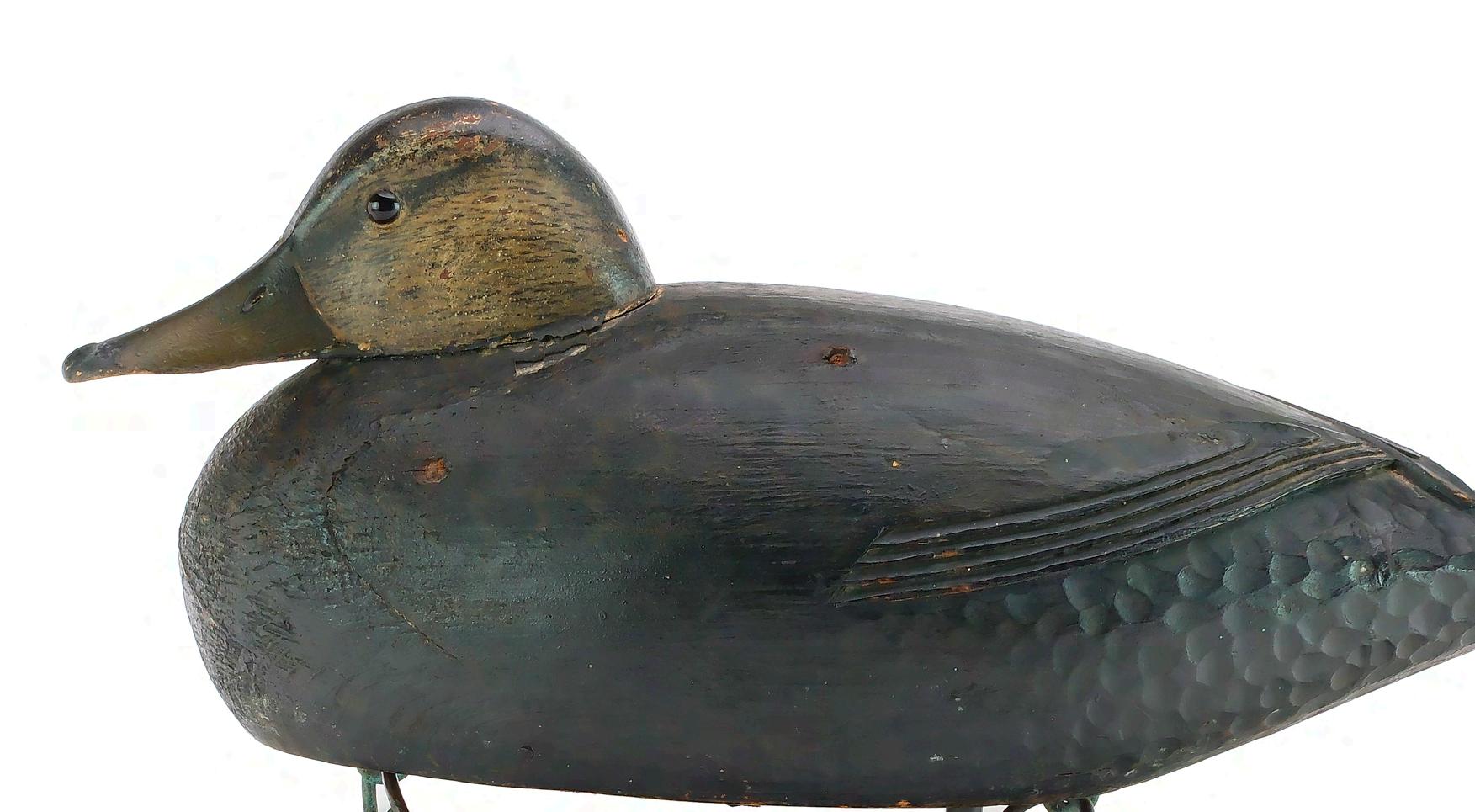

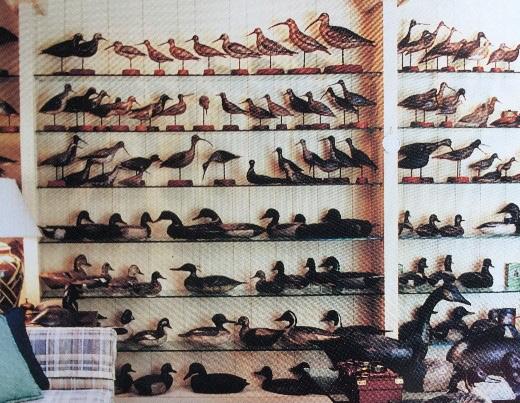

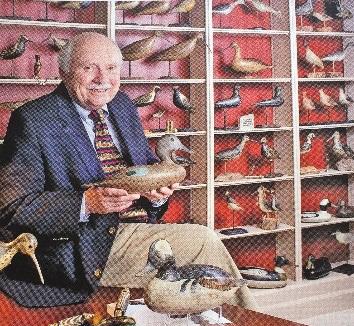

Guyette and Deeter are honored to have been chosen by the Harmon family to assist in the sale of their cherished decoy collection, certainly one of the finest assemblages of Massachusetts decoys ever held in private hands.

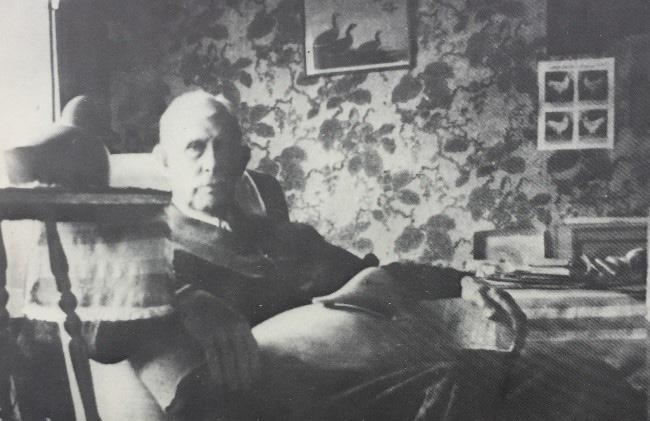

For Ted, his interest in decoys, especially those from his native Bay State, began in his youth and, since the beginning of their marriage, Ted and Judy’s lives have been centered around family and wooden ducks, geese and shorebirds. The Harmon’s truly loved their decoys and the tales they held. Not every bird in their collection needed to be pristine to be enjoyed. The history of their makers’ lives and the times and circumstances surrounding the individual decoy’s use was an equally important part of the story and added greatly to their pleasure. We have tried to use this same approach in developing this exhibition catalog. In so doing we have borrowed liberally from research done by others and gratefully acknowledge the scholarship of these numerous students, authors and institutions and have listed as many of them as possible at the end of this booklet.

Bill Lapointe

Jon Deeter

Zac Cote

First, my family would like to thank the Havre de Grace Museum, Jon Deeter and Zac Cote for their support of this book and exhibition. We also have to extend our heartfelt gratitude to family friend and author Bill Lapointe for his thorough research and expert writing. Thank you all for making this project a reality.

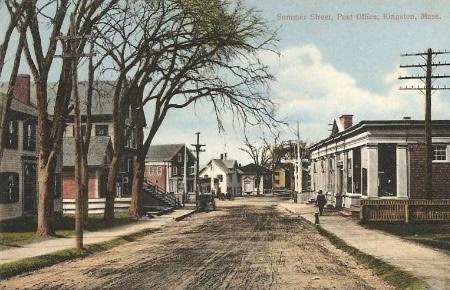

It’s hard to say exactly when my father’s journey into the decoy collecting world began. Had his father not moved the family to Cape Cod when he was a young boy I likely would not be writing this. The family move when he was just a young boy laid the foundation for his love of the outdoors, and ultimately his appreciation for the art of the decoy.

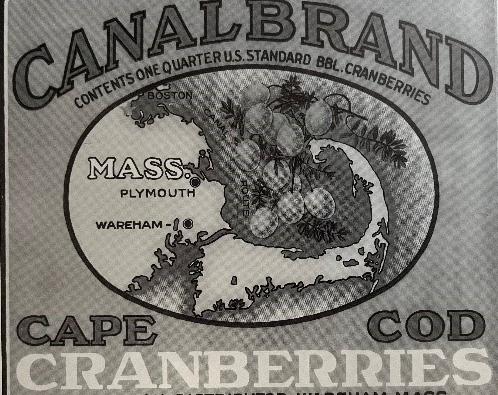

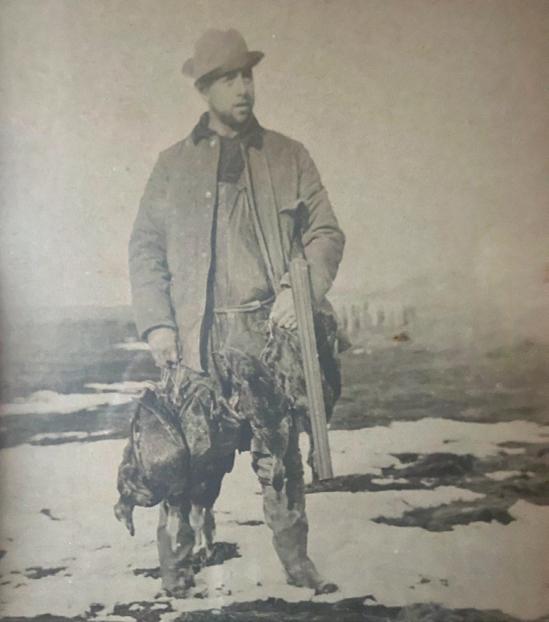

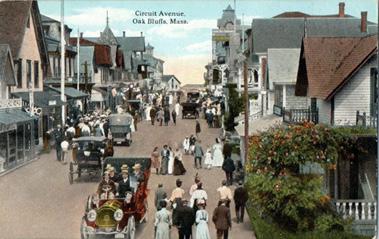

The Cape Cod my father found was a place of dirt roads, cranberry bogs, freshwater ponds and extensive saltmarshes. Most of it was still wild and largely undeveloped. When fall arrived the summer people shuttered their homes and cottages and the motels closed their doors. What they left behind was an outdoorsman’s paradise. His home town of Osterville was full of upland game and its five saltwater bay s teemed with oysters, clams, fish and ducks. His youth was spent in these uplands, pon ds and bays of shellfishing, boating and hunting. As a young man he could throw his decoys, shotgun and trusty

lab Bridie into his old Willys Jeep and hunt any of these places without a worry. There were many nights at Sandy Neck in the duck camps as well as trips to Maine to hunt Merrymeeting Bay and Swan Island. Dad always preferred shooting over decoys with his faithful black lab Bridie by his side. Certainly, this is w here his first appreciation for decoys began.

On one trip to the Great Marshes in Barnstable, not far from where we eventually grew up, he found a Mason standard grade black duck under an old, dilapidated gunning shack. It was of course devoid of most of its paint. As any of the old hunters would do, he repainted it and hunted over it for a few years. He kept that bird for almost sixty years and to this day we still have the “cornerstone” of his collection!

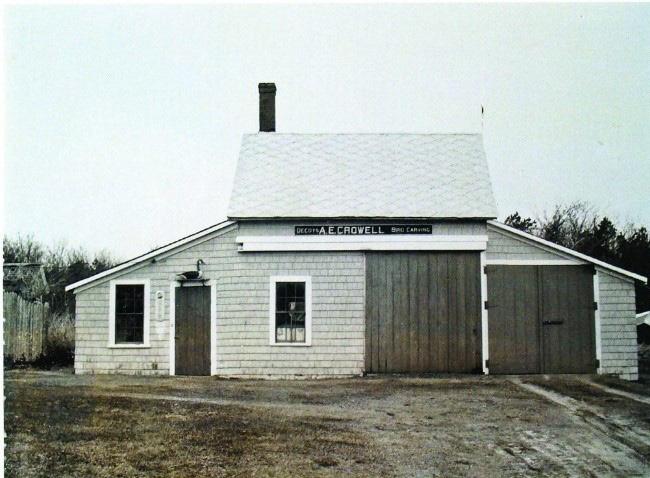

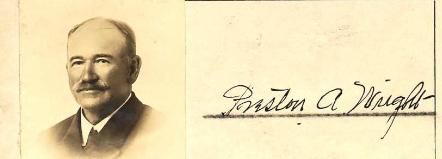

So began my father’s lifelong passion for collecting decoys. Over the years he and my mother traveled throughout the country to decoy shows and auctions where he bought, sold and traded, always looking to “tuck” away a few things for his personal collection. This passion led to him opening his own auction business, Decoys Unlimited Incorporated. The business operated for over thirty years and allowed him to continue learning and sharing his knowledge with his fellow collectors. In time his personal collection grew to represent many of the finest New England shorebi rds and decoys in the country. Decoys from his personal collection have been exhibited at the Heritage Museum and Gardens, Peabody Essex Museum, The Riverfront Museum of Peoria and Massachusetts Audubon, among others.

This book represents many of the best and most important Massachusetts decoys my father acquired during his fifty plus years of collecting. It is also a chronicle of the men that made them, where they were from and how they lived. Our family sincerely hopes that you enjoy looking and learning as you turn through the pages of this unique history. It is a fitting tribute to my father’s lifelong passion for collecting and the importance of these decoys and the men that made them.

Enjoy!

- Steven Harmon

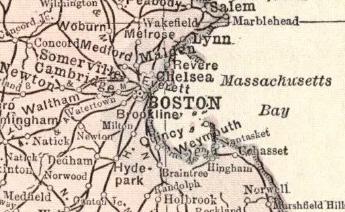

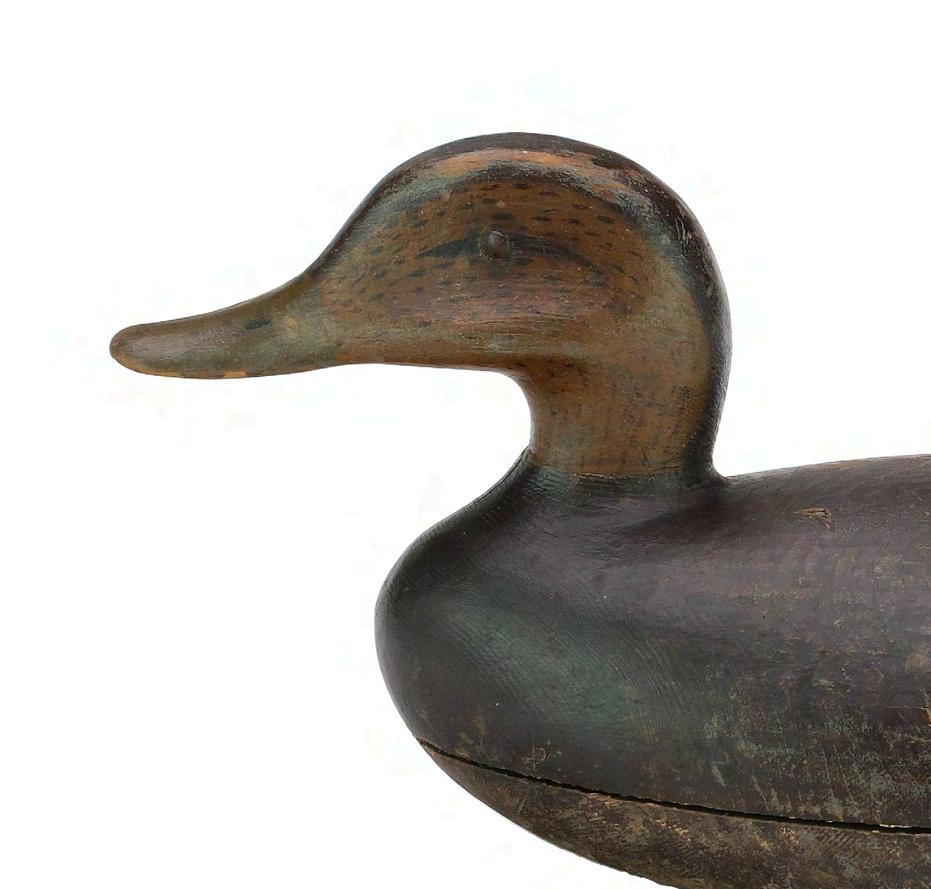

Fundamentally, the hunting of ducks, geese and shorebirds in Massachusetts is no different than pursuing them in any other part of North America. There are, however, some aspects of the hunt that somewhat distinguish the State from other areas. Some of this may be due to its physical location on the migration route(s) of the various species. Eiders, at least during the “golden age of shotguning”, were rarely found much further south than Cape Ann at the northern end of the State. Likewise, species such as the canvasback, so very prevalent and popular in the Chesapeake, were considered rare visitors to Mass. If Massachusetts was to have a State duck it would undoubtedly be the black duck and, perhaps, more decoys were carved for that species than any other. Other waterfowl were also found in abundance, Canada geese were plentiful, provided great sport and were excellent table fare. Scoters were abundant and, so, most decoys found for them today, came from Massachusetts. On Cape Cod, in particular, mergansers were seen in numbers and, although of questionable culinary value by some, many extremely fine decoys meant to attract them were carved. Typical Yankee frugality also entered the carver’s decision making when it came to making a decoy. Why carve a bird for mallards, if they would be easily drawn to a replica of a blackduck and, similarly, goldeneyes would get most other divers to, at least, swing by the rig. Shorebirds of many species were plentiful in great numbers from north to south and the State possessed acre upon acre and mile upon mile of favorable marsh, meadow and beachfront that attracted the birds.

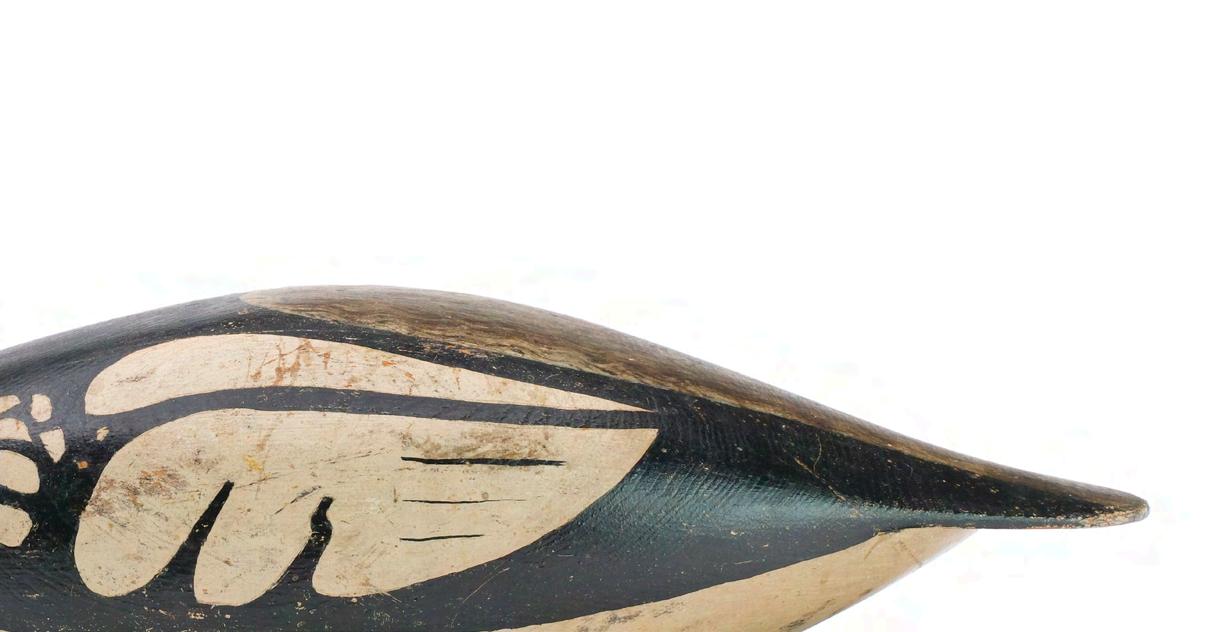

In terms of the decoys, there existed a great deal of diversity. There was no set “school of carving”, and everyone felt free to express their own design ideas. The birds tended to be solid with a some notable exceptions. There were a few unique designs such as Joe Lincoln’s singular “self-bailers” and the canvas covered method

of construction which saw some popularity on a regional basis. Some areas favored the use of keels while others did not. The heads were mounted both directly onto the body or mounted on a slight neck shelf. The hunters favored slightly oversized birds, many of which featured some form of carved wing detail. With the exception of gunners on the North Shore leaning towards the use of skull boats, there was no distinctive watercraft in widespread use, such as New Jersey’s well known sneak boats. Most hunters simple utilized whatever was the locally accepted design for a small, rugged skiff. More so than those for ducks and geese shorebird lures were commonly hollow carved, and hunters tended to favor a split tail design. Because the shorebird decoys had to be carried some distance, weight was a consideration, and “flatties” were very common.

Residents of the Bay State hunted what was available, first for food, then monetary profit and, finally, sport. They simply developed hunting methods that were best adapted to the game being sought. This resulted in activities such as the practice of line shooting for coot and the development of highly specialized camps for specific species, such as Canada geese and brant.

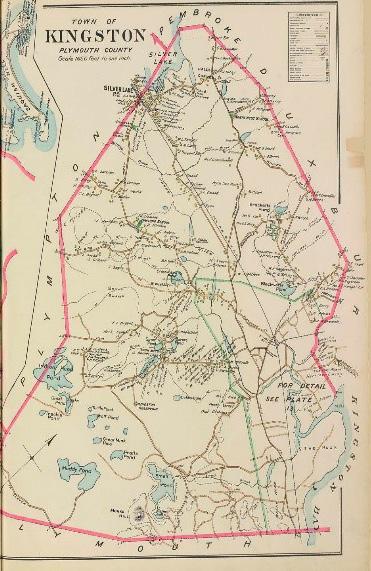

Massachusetts, like all states, has firmly drawn boundaries. Needless to say, these have little effect on the movement of birds. The marshlands and beaches on the State’s northern border blend seamlessly with those

in adjoining southern New Hampshire. Likewise, the salt ponds and other habitats along the southern border continue into and mesh with those in abutting Rhode Island. Just like the birds, the human hunters at both boundaries of the State influenced, and were influenced by, their counterparts immediately across the State lines.

Finally, Massachusetts has a proud and distinguished reputation for conservation. The State has produced many of the most influential individuals at the forefront of wildlife management and habitat protection, and this heritage continues to this day.

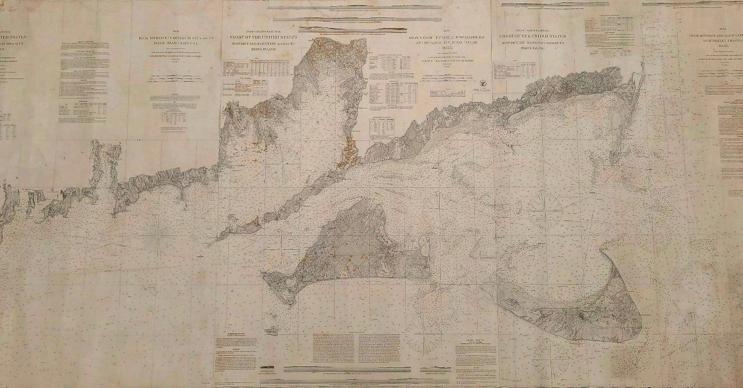

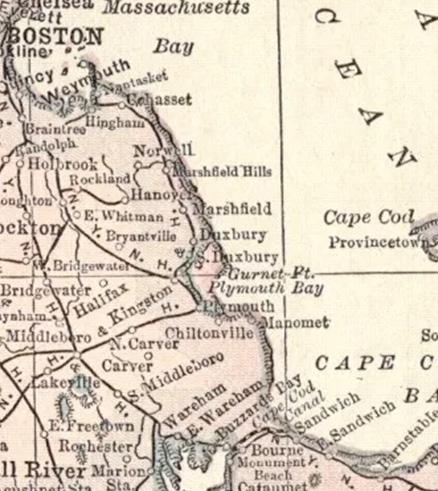

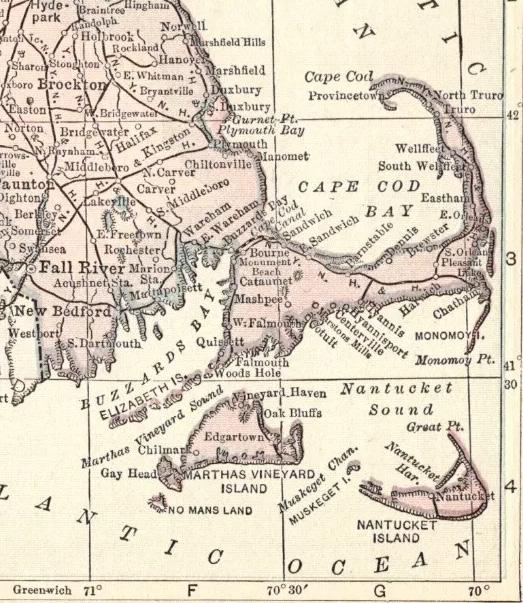

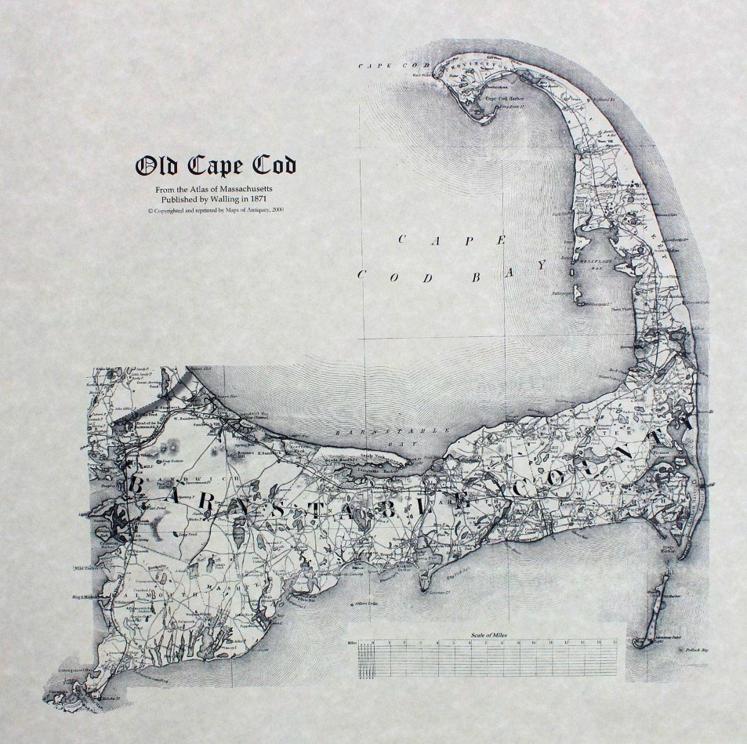

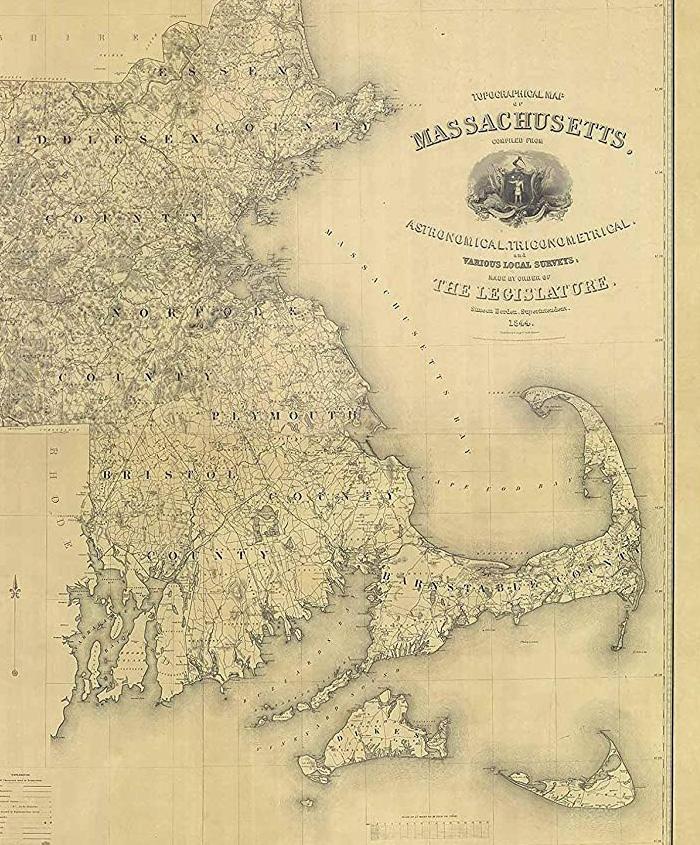

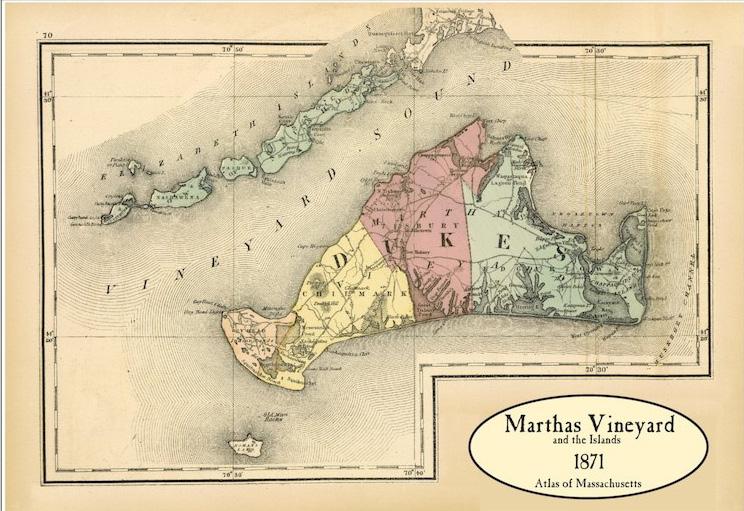

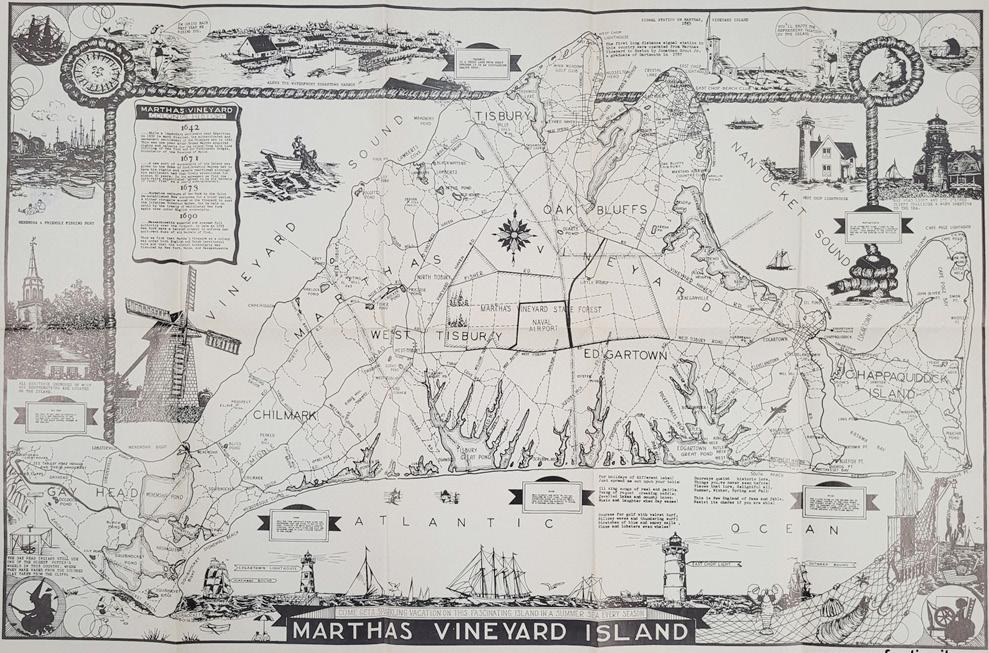

The land mass that we know today as Massachusetts cannot be well understood without a brief mention of the glaciers and ocean currents, both of which played pivotal roles in forming the area. Roughly 12,000 – 15,000 years ago the last of a number of mile high sheets of ice advanced southward. This ice required immense volumes of water in order to form and the state’s shoreline was as much as 400 feet lower than it is today. As the ice advanced, its incredible weight ground down the tops of mountains to the north and absorbed this material either within itself or, pushed it up, bulldozer like, along its advancing face. This can be clearly seen in the piles of earth that are today’s Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and Elizabeth islands. The States most notable landform, Cape Cod, clearly marks the southernmost extent of the most recent glacial advance. The ice would also be instrumental in forming the ultimate path of the area’s rivers, the locations of its many swamps, and the formation of so-called “kettle ponds” on the Cape and elsewhere. The ice is also directly responsible for depositing the tons of materials needed for the hundreds of miles of New England’s iconic stone walls.

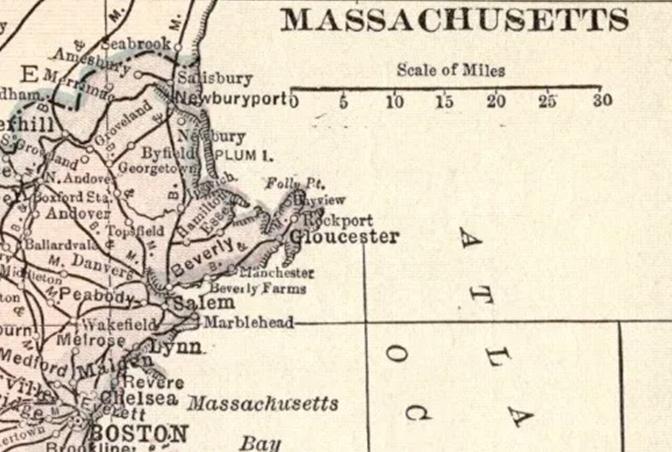

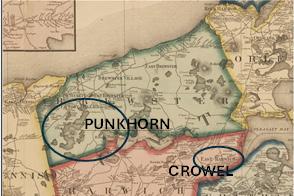

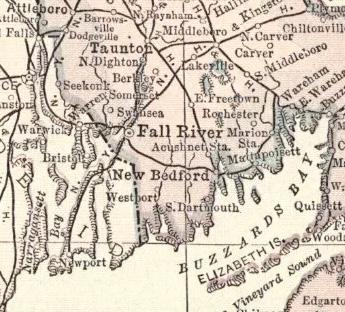

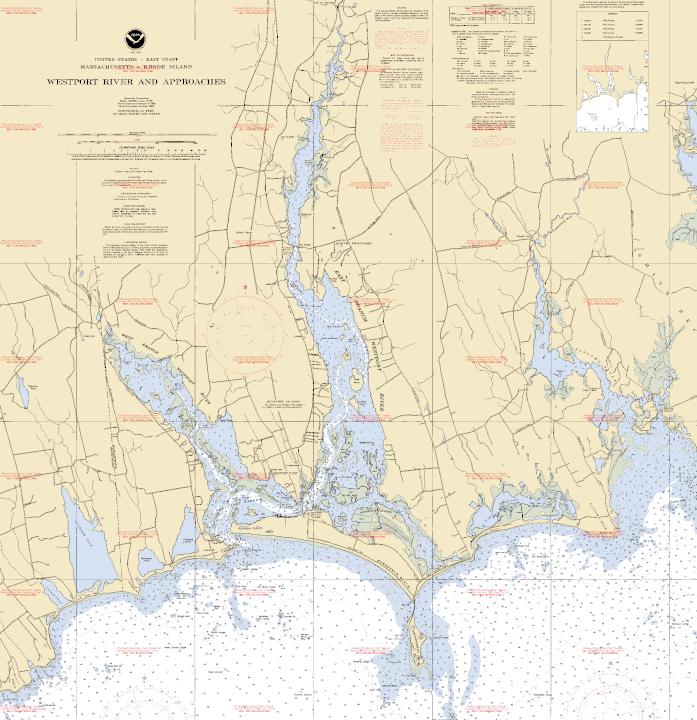

Once the basic shape of the land was developed, major ocean currents, one flowing down from the north and another, even larger, flowing up from the south, carried suspended sediment that would ultimately settle out and result in the formation of major barrier beaches. In turn, these beaches would allow for the development of vast marshlands on their leeward sides. Most notable of these can be seen today in northern Mass in the area of Plum Island, on the Cape with the Barnstable Great Marsh as well as those marshes along the outer arm of the peninsula and, finally, on the south coast in the area of Westport and Dartmouth. Sand -spit islands both large and small can also be attributed to these ocean flows, notably Monomoy on Cape Cod. These wind and water borne shifting sands continue to shape the shoreline of Massachusetts today.

Most people are aware of Massachusetts and its place in history. The story of the pilgrims landing in 1620 is known to every school child in the country. The menu served at the first Thanksgiving may well have included the native cranberry as well as some sort of waterfowl. As the population began to grow, settlement began to rapidly radiate out from Plymouth. The state’s northernmost town, Salisbury, had been settled by 1638 and Westport, to the south, (originally part of Dartmouth) was settled in 1652.

Population growth and the expansion of towns was not without incident. In 1675, animosities and other disputes with the local indigenous people, the Wampanoags, over land ownership reached the boiling point. Metacomet, (the son of chief Massasoit who had initially befriended the English) staged a bloody two-year war with the settlers with devasting results to both sides. The colonists would ultimately prevail, but at the expense of 600 of their own lives. Seventeen white settlements were destroyed, and fifty additional settlements damaged. The native tribes suffered an even worse fate, being practically wiped out. King Phillip’s war, as it was known, was the bloodiest conflicts (per capita) in all of U.S. history.

The road forward continued on its bumpy journey. Internal religious conflict had always been an issue. Roger Williams was banished from the colony in 1636 “for holding four dangerous (religious) opinions at variance with official policy” and he and a group of followers left to establish what was to become today’s Rhode Island. In 1692 – 93, in the town of Salem and neighboring communities, religious hysteria would result in over two hundred people being accused of witchcraft, resulting in the death of around 25 innocent members of the community.

On the local and regional level, political unrest would occupy the lives of the residents for the next few generations. Land disputes would ultimately be resolved, establishing the boundaries of today’s towns and even the current State lines of much of the rest of today’s New England. Internationally, all are familiar with the wellknown stories of the “Ride of Paul Revere” and “The shot heard round the world” resulting in the ultimate split from England and the formation of our country.

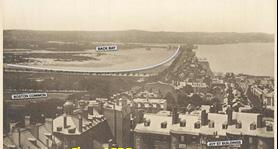

Religious and political conflicts becoming somewhat resolved, economic growth could resume. Early on, Plymouth, due to its shallow harbor, lost its prominence as Boston became the colony’s seat of government, business, education, and the arts.

The glaciers were not overly kind to New England, including Massachusetts. Literally billions of stones, both large and small, covered the thin soil as they were deposited due to the melting of the ice. Traditional crop production was tedious at best and people either planted the few crops that were suited to the existing soils or resorted to the sea. Favorable ports, ranging from those on Cape Ann to the North, to Westport on the South coast, all developed large and profitable fleets plying the rich offshore fishing grounds. Towns such as Nantucket and New Bedford would gain world prominence as centers of the whaling industry. Other towns would develop their own niches as centers for a wide variety of industries, particularly shoe making and textile mills. Many citizens prospered and some became extremely wealthy. Leisure time and financial security meant that hunting for sport could be enjoyed, and this required decoys. Massachusetts carvers responded by producing some of the very finest decoys ever produced in North America.

Conservationist

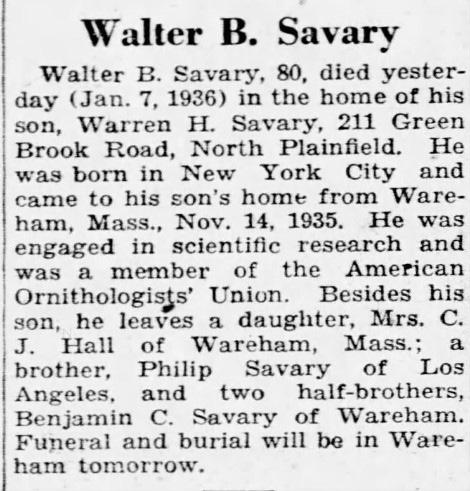

The roll of Massachusetts men and women in the formative years of what we might refer to today as the conservation or environmental movement cannot be overestimated. Many of the State’s early sportsmen and sportswomen were also avid amateur naturalists/ornithologists and, fortunately for us today, many wrote profusely, and many kept detailed diaries or journals. As early as 1854, Concord, MA born Henry David Thoreau (1817 – 1862) published his influential “Walden or A Life in The Woods”. Of the turn of the century sportsmen/naturalists, perhaps the best known would be Dr John C Phillips (1876 – 1938) who wrote extensively in both sporting and scientific publications. He also had the means by which to privately publish so many of the books that we enjoy today which documented the sporting life of the times. He was not alone in his zeal. The Nuttall Ornithological Club, the first of its kind in the country, was formed in Boston in 1873 with William Brewster (1851 – 1919) as its first president. Brewster was, as so many of the ornithologists of the time, a Boston gentleman of means with an insatiable curiosity about the natural world. From 1876 through 1883 the club published its own journal, “The Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club” which recorded many of the early waterfowl collecting trips of club members. In 1883, the Bulletin was handed over to the newly formed American Ornithological Union (AOU) who continued publication under the name of the “AUK”.

In 1896, outraged by the wholesale destruction of birds for the millinery trade, two wealthy Boston women, Harriet Lawrence Hemenway and her cousin Minnie Hall, formed the Massachusetts Audubon Society, the first of its kind in the country. The ladies possessed important connections to Boston society and, perhaps more importantly, their husbands had similar influence with other wealthy Boston businessmen. The group soon drew support from the wives of influential Massachusetts sportsmen, such as Mrs. John C Phillips and others. Their husbands, in turn, were responsible for attracting other Boston hunter/sportsmen to the cause. Men such as George Henry Mackay and Harvard professor Charles Sedgewick Minot (1852 – 1914) served as early directors.

The formation of Mass Audubon fueled the creation of numerous other ornithological clubs throughout the state. These clubs were extremely popular with both birders as well as sportsmen and artists. The Essex County Ornithological Club could be considered typical. It boasted among its many members, men such as John C Phillips, carver extraordinaire Fred Nichols (1854 – 1924) of Lynn and noted Salem sporting artist, Frank W Benson (1862 – 1951).

Harvard University was the preferred institute of higher learning for the Massachusetts elite. Among its repertoire of talented professors was Louis Agassiz (1807 -1873). His zoology courses were extremely popular and decoy carver Newton Dexter (1838 – 1901), of Rhode Island’s Gardner/Dexter decoy fame, accompanied him on a collecting expedition to Brazil in 1865 as the trips head marksman. Similarly, in 1876, Massachusetts Institute of Technology professors Edward Charles Pickering and Samuel Hubbard Scudder joined with other Boston based academics to form the Appalachian Mountain Club to encourage mountain exploration and preservation in the northeast. Again, this was the first group of its kind in the country. It was at institutions such as Harvard and MIT that many of the State’s wealthy sportsmen not only received their education

but also formed lifelong associations with other, similarly trained individuals. The so called “old boy network” was very much alive and well. These were the men that traveled to prestigious hunting clubs on the Chesapeake and further south, and these were the people who had memberships or were invitees to the best of the Massachusetts hunting opportunities. Many of these individuals would become patrons of Elmer Crowell and send him on his meteoric journey to become the father of American bird carving.

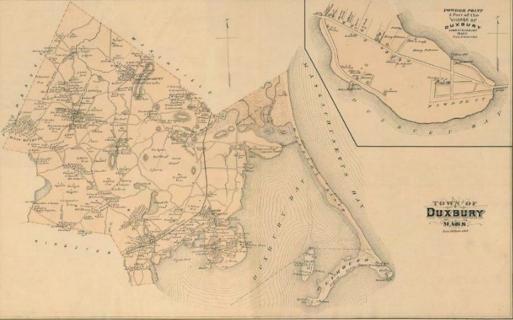

Through the 19th and 20th centuries, Massachusetts continued to play an active role in the conservation of our natural resources. In 1944, The New England Forestry Foundation was founded in Littleton. In the 1950’s, Duxbury’s Olga Owens Huckins had turned her property into a private bird sanctuary. When she noticed many of the birds on the property were dying after the arial sprays for mosquitos, she contacted a person she knew who wrote for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to see what could be done. That person was Rachael Carson who penned the 1962 epic book, “Silent Spring”, which ushered in the beginnings of a national awareness of the dangers of pesticides. These are only a few of the many stories of Massachusetts Sportsmen/ Naturalist that have had a positive impact on conservation nationwide

“Upon ye beach they spied great multitudes of birdes of manie kindes, they being there to pick up ye wormes and little fishes. They ha bills wch they thrust into ye little holes in ye sand and pull up ye fat wormes with great relish. Ye beach birds are verrie shy and quick a-wing but our sportsmen, nevertheless do bring down great plenty for their own use and if need to supply their plantations”.

(Obediah Turner, Lynn, MA 1638)

Shorebirds were actively hunted in Massachusetts from a very early date. Initially, regardless of the above author’s reference to “sportsmen”, the pursuit would have been solely for sustenance. Did the colonists simply ambush the birds or were the indigenous people already using basic decoy forms? Obviously, we can never be certain, but at some point, again presumably very early, the shorebird decoy emerged in Massachusetts. We have to assume that these initial attempts at mimicking a live bird would have been very simple creations, likely a form of basic root head construction. Development probably advanced slowly, after all, there were a multitude of necessary daily activities that would occupy all of the early settler’s time and energies. At some point, likely in the 1700’s, life became a little easier and there were the very beginnings of something that resembled free or leisure time and the decoys that actually looked something like a real bird may have begun to emerge.

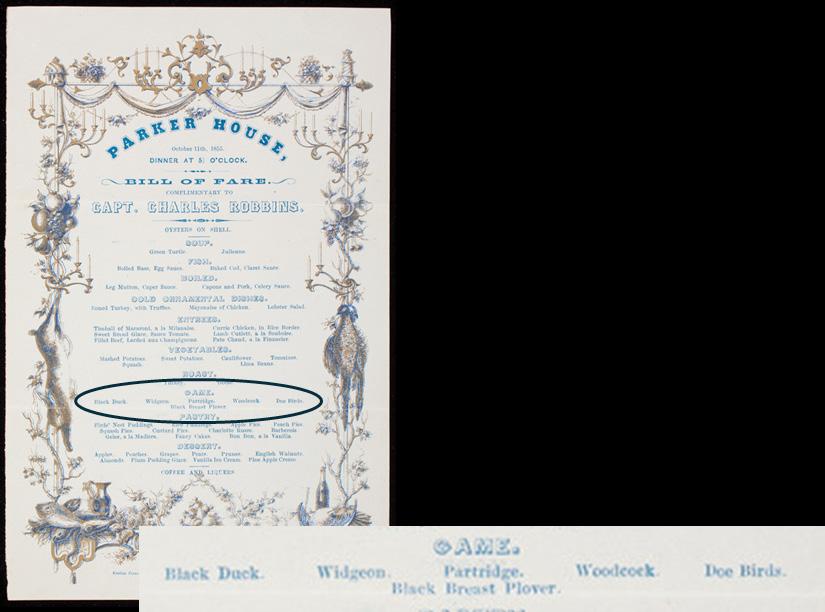

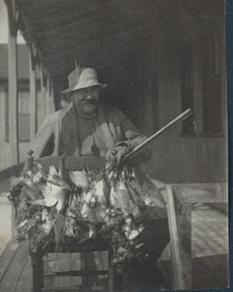

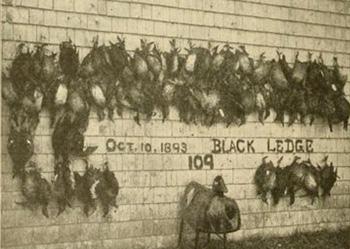

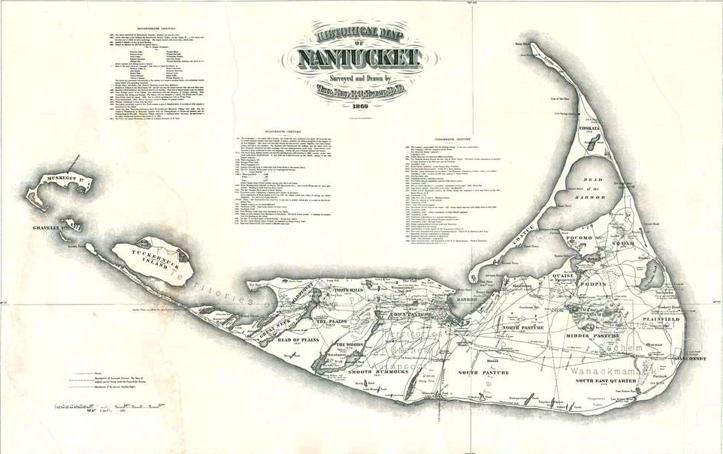

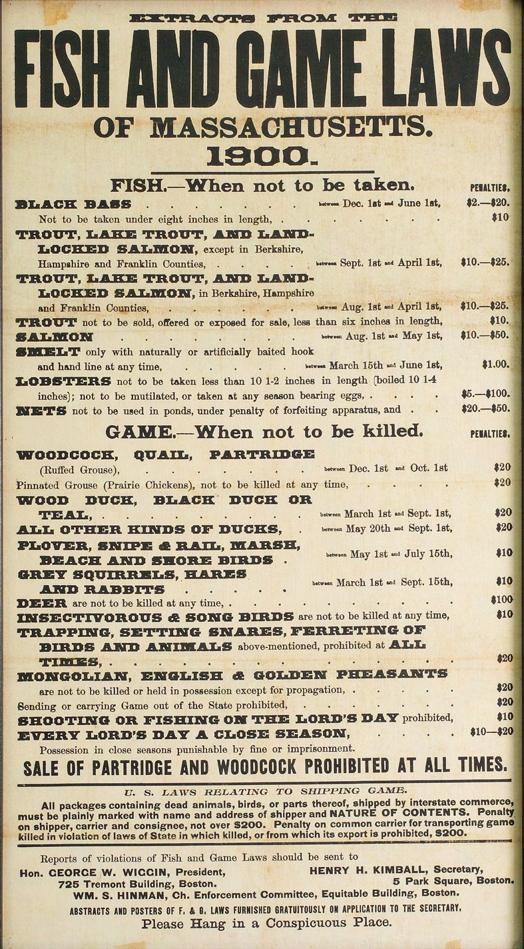

By the early 1800’s, with the rapid growth in population numbers, especially in the cities, the market hunter en tered the scene. Game of all sorts was targeted, includ ing shorebirds. The birds were shot by family members for their own consumption and any excess could be readily sold through local markets. Others pursued the birds purely for profit. There are numerous records of shipments of huge quantities being iced down in barrels and shipped to markets in Boston, Providence (RI), and beyond. Noted Massachusetts ornithologist, Edward H Forbush, reported that on August 29th, 1863, between seven and eight thousand golden plover and eskimo curlew were killed on Nantucket and Tuckernuck and that “- - - all the powder and shot on the Island was expended and the gunners had to send to the mainland for more” . As abhorrent as this may seem today, this was a widely accepted practice that provided income for many rural families and the birds were considered fine table fare, appearing on the menus of some of the

By the mId to late 1800’s the sportsman would rivel the market hunters in the hunt. These individuals certainly had the time and resources to make or purchase decoys of better and better quality. This was not unique to Massachusetts. Certainly a few carvers of distinction emerged at other locations along the coast, notably on Long Island, New Jersey, and Virginia. What would set Massachusetts apart, however, was the number of carvers that went far beyond what would have simply sufficed to lure the birds to the gun. As Elmer Crowell himself once commented, “_ _ _ yellowlegs were so stupid they would decoy to a sock on a stick”

Competition among the hunters would have inspired some to produce decoys that were more lifelike and superior to those used by others and, thus, some extremely fine carvings were created. These individuals not only advanced the painting of the birds, but they produced probably the greatest number of decoys in poses that went far beyond the basic and simple erect, straightahead position. Keen observers of the living birds, the carvers produced birds that were running, feeding, preening, sleeping or gazing to the right, left, or upward. Some even attempted to impart life into the carvings with wings that would flap when activated by a string, or birds that would gently bob and sway in the wind.

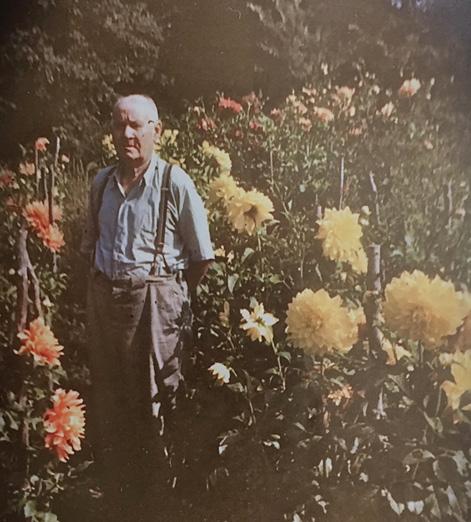

This desire to more closely mimic the live bird was probably due to a number of factors. Most notably, shorebird hunting was extremely popular. Many species of the birds were drawn to the extensive favorable habitats that the State possessed. The Cape and Islands, in particular, jutted out to sea and intersected the migration routes of many of the birds. Presumably, better decoys would draw in more birds, but that alone would not be sufficient cause to produce some of the carvings that were executed. Certainly, for some, the carvings provided an outlet for suppressed individual artistic leanings or a latent creative talent. The one thing that undoubtedly influenced many of the carvers, either knowingly or otherwise, was the upsurgence of interest in all aspects of nature study and ornithology throughout the State. Bird clubs, both large and small, could be found ranging from the halls of Harvard to church and grange meeting rooms from north to south. Avid gunners and carvers such as John C Phillips and Fred Nichols on the North Shore were active members of the Essex County Bird Club, George Henry MacKay of Boston was an early director of the Audubon Society, Charles Safford became the first game warden on Plum Island and Joe Lincoln and Gordon Mann on the South Shore were active members of the local horticultural society. The subjects were considered important enough to be included in many school curriculums statewide and many of Elmer Crowell’s sets of miniature carvings were destined for classrooms or libraries. As a more practical matter, these were the days when travel relied on horseback or on foot. Weight and bulk were concerns, especially as the rigs got bigger and bigger. To address these issues, decoys carved to an eggshell thinness were created as were thin flatties. Some creative individuals experimented with lightweight materials such as paper mâché. The lightweight, collapsible “tinnie” was created in Boston by the firm of Strater and Sohier in 1874 and became extremely popular. What resulted from all this interest and creativity were shorebirds of a quality and variety not equaled in any other part of the flyway.

Decoys for a wide variety of species of shorebird were carved, ranging from the tiny sanderlings and sandpipers (collectively referred to as peeps) to the large willets and curlews. Some species, such as ruddy turnstones, were seldom carved while others, such as plovers, yellowlegs, and dowitchers were produced in abundance. As one would expect, decoys found in any particular area would be indicative of the live birds that frequented that region. Carvings meant to represent golden plover and eskimo curlew for example were most prevalent from the outer Cape to the Islands, especially Nantucket and its two smaller neighbors Tuckernuck and Muskeget.

The birds themselves would arrive in the State at staggered times between late spring and early fall. The two migrations of yellowlegs, for example, did not coincide. The lesser yellowlegs, or summer yellowlegs, would typically appear in mid July and depart by late August, while the greater, or winter yellowlegs, would arrive in late August and, in some years, linger into November. This was contrary to many of the duck and goose species which occupied the gunners from fall through the harsher winter and early spring months. This meant that the shorebird hunter did not need to face uncomfortable weather conditions to be successful. Quite the contrary. The typical shorebird hunt more closely resembled a pleasant day at the shore where the birds were hunted in a comfortable, leisurely fashion and the term

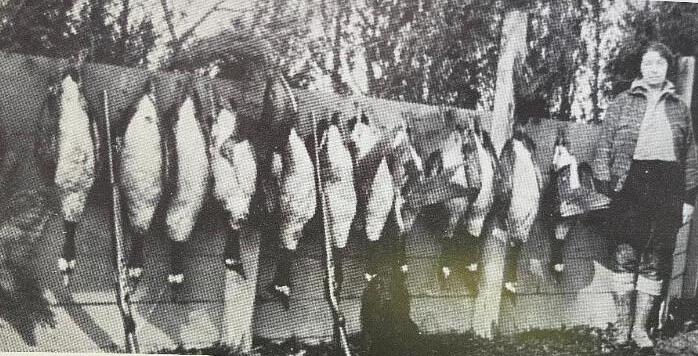

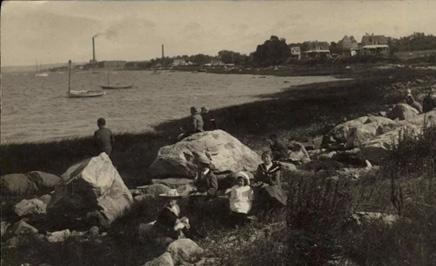

“The genteel sport” best described the pursuit. Certainly, some women hunted ducks and geese in the typical manner, but far greater numbers would have been seen waiting for the whistle of an approaching bunch of shorebirds. Husbands took their wives and fathers took their daughters. Writing in the September 1880 issue of “Scribner’s Monthly”, South Coast Dartmouth summer resident, Alice Wellington Rollins, penned: “ Nor shall you be confined to the silent companionship of flowers and leaves - - -or the white throated plover falling as easy prey to your gun”.

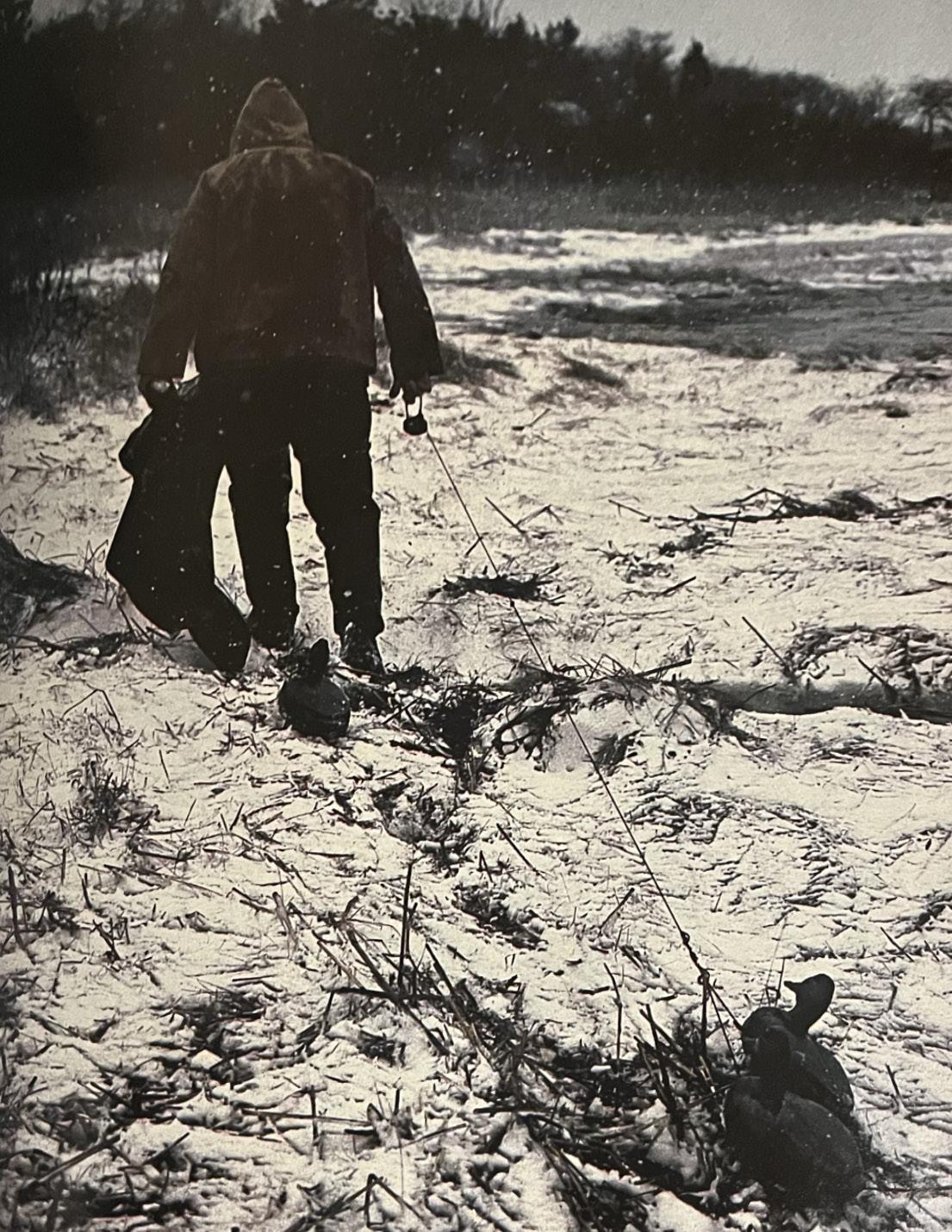

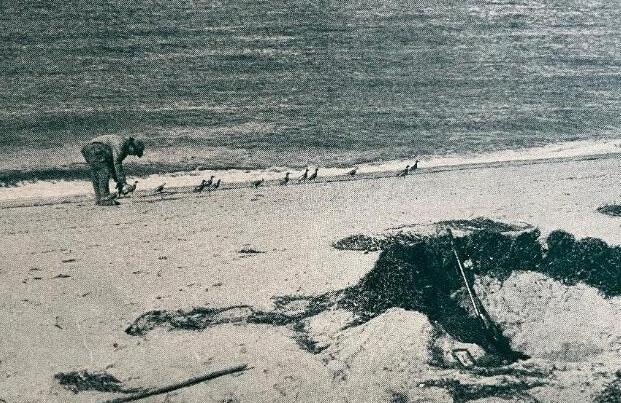

Contrary to the common image of a singular gunner, comfortably crouched behind a few sparse twigs on a sandy beach, a variety of blinds were employed to conceal the hunter. Yes, that simple assemblage of twigs would occasionally be employed but, more commonly, shallow pits were dug in the sand. These would be located along the “wrack line”, that area where the waves deposited loose rows of seaweed and small ocean debris. This placed the hunter as close to the water as possible and made it easy to disguise the pit by ringing it with handfuls of the surrounding seaweed and flotsom. This type of blind would be employed when pursuing those birds that were, truly, beach birds – the peeps, dowitchers and their brethren.

Those species more attracted to the marsh, such as yellowlegs, would usually encounter more elaborate “brush blinds” built on small hummocks in the marsh or, occasionally, a hunter concealed in a sunken barrel (hogshead) on the marsh itself. These barrels were effective but also involved almost daily bailing out.

Where golden plover and eskimo curlew were the targets, such as on the outer Cape and Nantucket, the birds were hunted on the upland moors where they would be found feeding on insects. The hunters would often purposely burn over an area prior to the birds arrival to encourage fresh grass to grow and entice a healthy insect crop. Here pits, again, were employed, and care taken to remove what was dug out so as to make the hides less conspicuous. On Nantucket, the remnants of a number of these are still to be seen today on the moors. As one would expect, there were no hard and fast rules when it came to the hunt, and blinds were adapted to whatever the surroundings required. The majority of the time, these would hold no more than one or occasionally two hunters but there were instances where rigs were combined to accommodate groups of hunters allowing for a larger decoy spread.

Occasionally, when the birds would not decoy, a few more adventurous spirits would creep along the beach and attempt to ambush groups of feeding birds as they moved down the shore. An article printed in a December, 1906 issue of “The Outing Magazine” goes so far as to suggest that the hunter sew large leather pads on their shoes, much like a smaller version of a snowshoe, to aid in working across the soft sand as well as sewing the legs of one’s trousers to the shoes so the sand would not find its way in during the ambush.

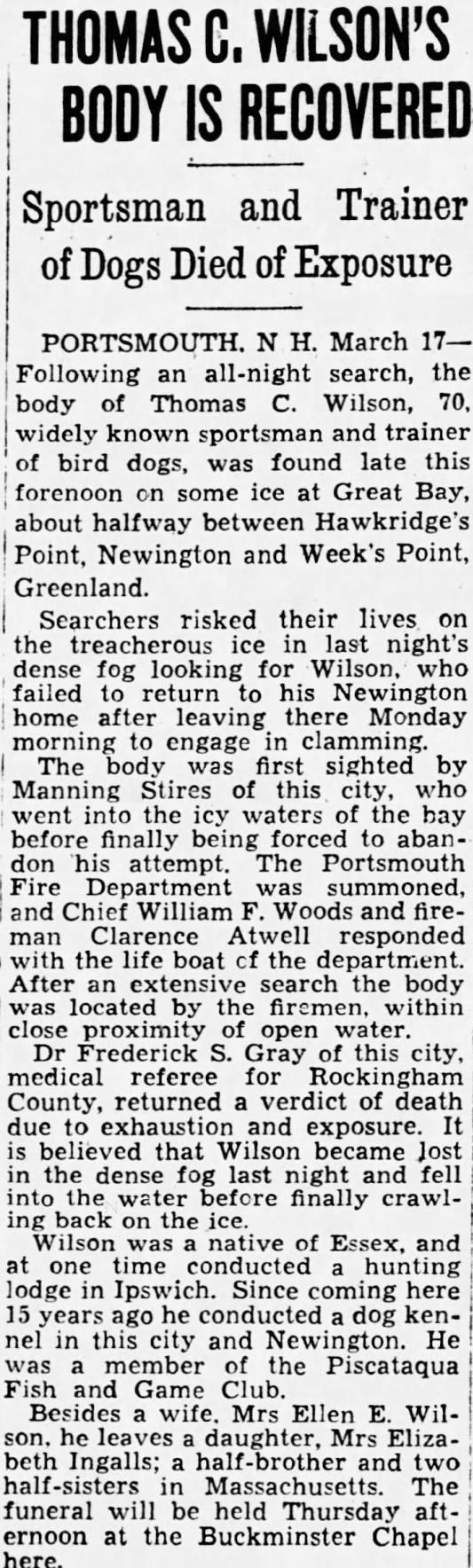

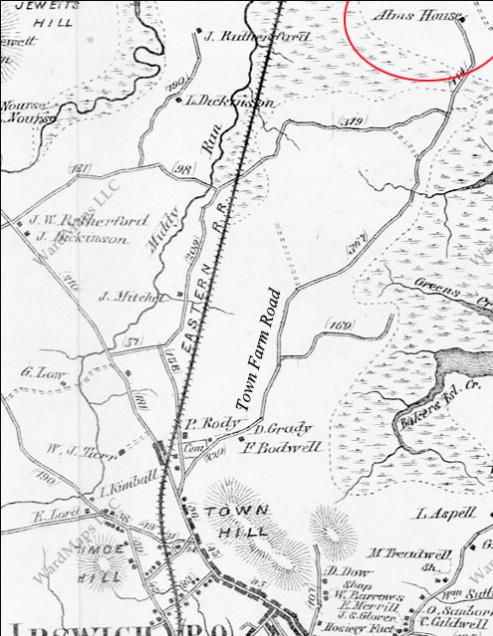

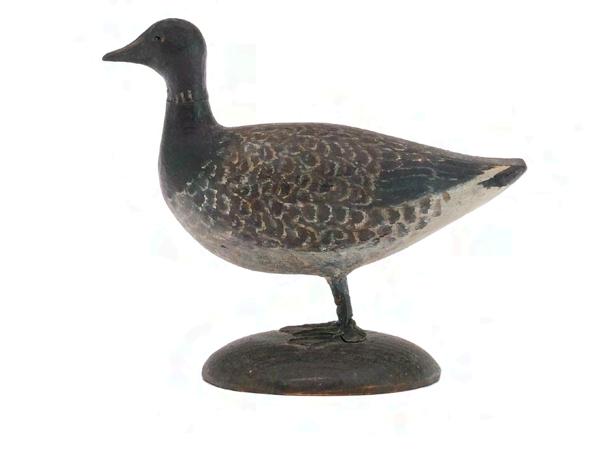

Certainly, shorebirds were hunted from north to south in the State, and decoys of distinction were created in all areas. Just over the border in New Hampshire, George Boyd produced some “finely carved and nicely painted” examples, many of which were sold in Boston sporting goods stores. On the North Shore, outstanding carvers such as Thomas Wilson and Fred Nichols, produced lures that would be the envy of the many ornithologists that frequented the area. On the north fringe of Boston, Melvin Gardner Lawrence produced an almost indestructible array of birds that were a joy to look at. On

the South Shore, commercial carver Joe Lincoln filled orders for a great number of hunters from both Massachusetts and beyond. Close by, Lothrop Holmes carved and painted decoys that today grace the shelves of the finest collections in the country. The Cape probably produced the greatest number of carvers, mostly anonymous, but native son, Elmer Crowell is one name that stands out in decoy fame. On the Islands, names such as Folger, Coffin, Starbuck and others are common and each produced delightful decoys that bear the distinct handiwork of family members. The South Coast seems to have lacked any singular luminary yet was host to untold anonymous carvers that produced some very notable decoys. As with the New Hampshire border to the north, the South Coast hunting areas merge with those of neighboring Little Compton, Rhode Island. Carvers such as the Sakonnet Point team of Clarence Gardner and Newton Dexter produced birds that were appreciated and were the inspiration for many decoys from the Westport, Ma area to the entire eastern shore of Narraganset Bay.

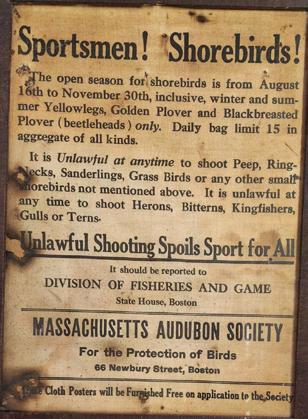

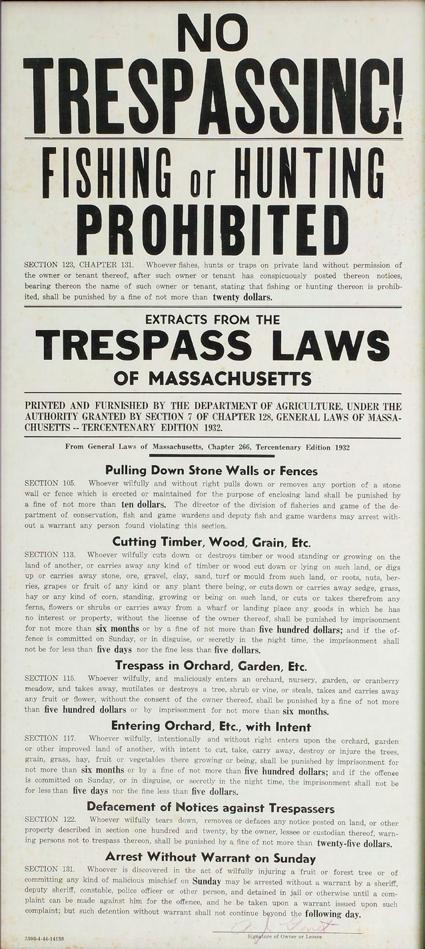

Most of the birds themselves were quite gullible. They were easily drawn to the decoys and responded readily to the commercially available shorebird whistles. Their population numbers slowly began to diminish, and some, such as the eskimo curlew, are now considered extinct or nearly so. Massachusetts began to regulate the hunting season for the birds at least as early as the late 1800s but did not establish any bag limits. The Federal government intervened in 1918 and curtailed the hunting for most species of the birds, but a few, such as yellowlegs and some plovers were still legally hunted until 1928 when, finally, all legal shooting ceased.

In Massachusetts, the three species of Scoters (Melanitta spp), black, white-winged and surf, were practically all grouped under the heading of “coot”. Not to be confused with the much smaller freshwater coot or “mud hen” (Fulica spp), the birds were common migrants along the northern Atlantic seaboard on both their fall and Spring migrations. They presented ready targets for those so inclined to pursue them. However, as noted by Van Campen Heilner in his 1939 “A Book on Duck Shooting”:

“But if you really want to shoot coot, then you’ll have to go down east to Massachusetts where coot shooting is a tradition. It’s just as much a tradition as baked beans and clam chowder, hot apple pie and Parker House rolls, as New England as the lobster and the cod”. (Heilner)

All three members of the group are heavy bodied birds, with thick layers of fat and feathers to shield them from the frigid North Atlantic. They will rest offshore and fly closer to land where they dive to depths to feed on

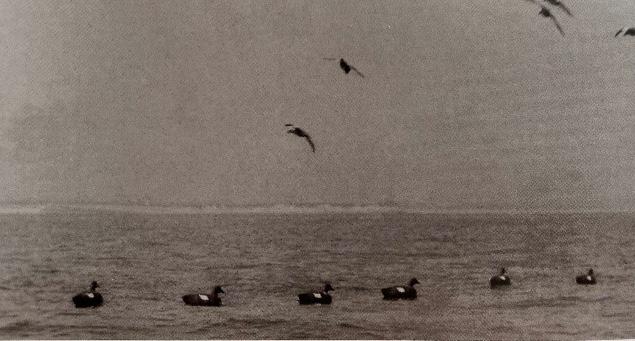

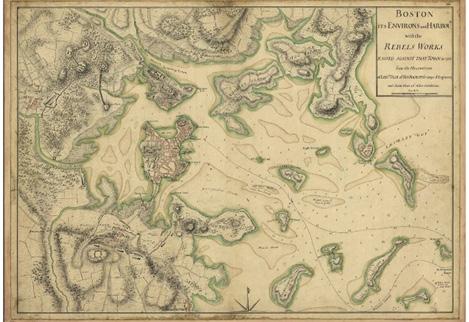

Points of land that jutted out to sea afforded the hunters the opportunity to launch their boats and bring the birds into accessible range. Once the migration started, one or two men would set out from shore in a small dory or flat bottom skiff and anchor themselves at a distance that would, hopefully, place them and the birds on the same path. As more groups of hunters arrived, tradition dictated that they would take up a similar position perpendicular to the coast at a safe distance from boats already on scene. On certain days, this “line” may have extended as far out as a half mile to a mile or more from shore and have up to twenty or more boats aligned parallel to one another. Thus positioned, the group presented a united gauntlet over which the scoters must pass. It was taboo to fall “out of line” as the scoters may think of this as a “hole” and give those shooters a perceived advantage. Usually a stray “accidental” or “wild shot” would bring the offending party back into line.

Coot shooting occurred along the entire coast of the State, but it was particularly popular on the south shore from Cohasset to Plymouth. Bags were often immense

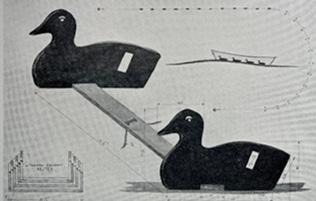

The birds lack of caution often meant that the hunt could be accomplished almost as a type of pass shooting. On most days, however, it was felt that decoys should be employed to increase the chances of success. Elaborate carvings were not needed as the birds would toll to just about any dark shape on the surface. Eventually, the majority of gunners settled on a design that was light, easy and very effective and the “coot nest” was developed. These nests consisted of groups of two simple scoter silhouettes mounted on a single or double pair of parallel boards. Each group (with identical silhouettes) was mounted on gradually longer and longer sets of separation boards so that 5 or 6 could be conveniently attached to one another with about 6 feet of rope and stacked within one another to form a single group of a dozen or so shapes. Usually, each dory would anchor out between one and four of these nests in a string, either directly in front of or directly behind the boat, although there was no set standard. On the North Shore for example, around Cape Ann, the string of silhouettes was set in a “J” shape looping around the rear of the dory. To gain the initial attention of the birds at a distance, the nest(s) may or may not, have been accompanied by six or so full bodied floating decoys. As odd as it may seem, if the birds were not immediately aware of the decoys, waving a hat or gun case in the air would normally get their attention. The boat itself was anchored with a float attached to the line. When it came time to retrieve a downed bird or chase a cripple, all one needed to do was unclip from the float and tie up again upon return without always pulling the anchor and resetting.

The actual hunt was usually difficult even under the best set of conditions. As with other forms of duck shooting, the best days were often those with the worst weather. Off the Massachusetts coast this traditionally would have been accompanied by a sea swell of varying heights with a wind chop on top of that. Add snow or rain to the picture and you have a scenario where both the hunter

and the hunted are in a constant state of motion with less than perfect visibility. Not only did the birds present a trying target, they were tough to kill. It is often said that the hunters could actually see pellets bouncing off the birds (probably at a distance) and a mere two or three pellets would not bring them down. Large size shot and ten gauge guns were pretty much the norm. If a bird was crippled, it would almost instantly dive when it hit the water and, being excellent swimmers, not surface again for fifty yards, only to dive again. Writing in a 1925 edition of “Field and Stream” Frank Hatch wrote, “I am sure that coot were designed for the special benefit of the manufacturers of gun powder and shells”.

Every author of every article on scoters or coot shooting, universally comments on the bird’s reputation for being marginable table fare with many claiming them to be unpalatable at best to totally inedible. Common tongue in cheek recipes usually read something like “bake on plank then eat plank ” or “ boil with an anvil and when you can pierce the anvil with a fork, remove scoter - - - “. By the same token, and often in the same article, reference is made to “ wonderful meals at the end of the day of a plate of steaming coot stew” . Massachusetts State ornithologist, Edward Howe Forbush, reported in 1929 that “ - - - scoters are killed and eaten by people living along the coast, where the woman know well how to prepare them for the table ”. Noted Taunton Ornithologist, and avid gunner, Arthur Cleveland Bent wrote that the “ - - - the young of the year or the grey coot ” when first arriving from their northern breeding grounds “ are fatter, more tender and less strongly flavored - - - “. There must be some truth in Forbush’s statement for when the sale of game was legal, scoters could be found in the Boston markets and, as shown in Dr Starr’s “Decoys of the Atlantic Flyway” a large sign hung in front of Henry Phillips’ fish marke t in Brant Rock (Marshfield) advertising “Coot For Sale Here”. They a pparently must have had a local following but this was certainly not the universal opinion.

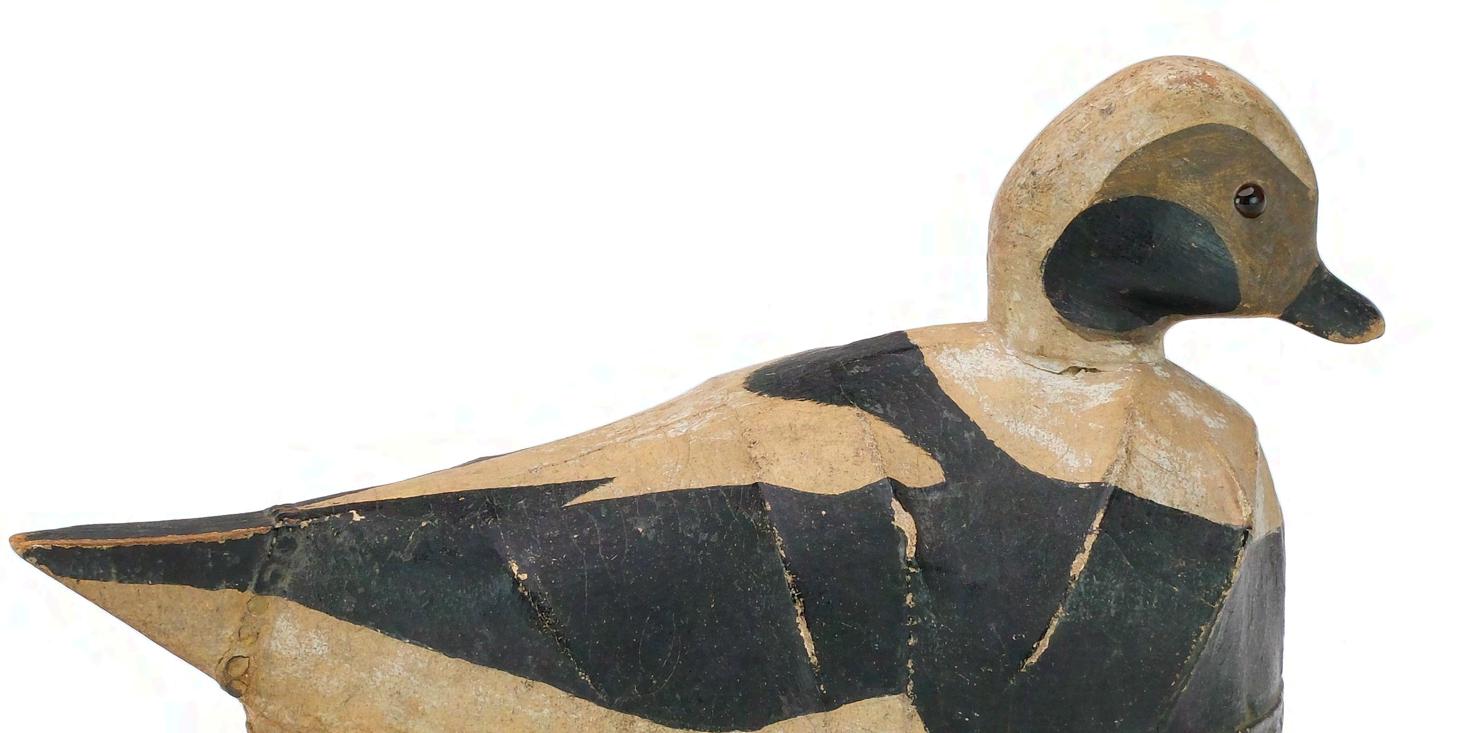

When in pursuit of the coot, other species of waterfowl would also be encountered. On the North Shore, the occasional eider was a possibility and everywhere, one was likely to be surprised by a swiftly passing pair or small darting group of long-tailed ducks. The flights were once huge, and reports of kills of over one hundred on a single tide were fairly common, even on Nantucket and on Narraganset Bay. These handsome birds suffered the same reputation as the coot when it came to their culinary desirability, perhaps even more so. Most were killed, solely in the name of “sport”. In 1929, Forbush reported that: “ Thousands of these handsome ducks are shot annually along the New England coast, and the dead and wounded allowed to drift away on the tide or picked up merely to be shown as trophies and afterwards left on the wharf or thrown away ”. One has to wonder why decoys were constructed specifically for them, as they would toll to the coot decoys. Fo rtunately for the collector, however, a small number of decoys were made, and these now represent some of the finest and most desirable decoys from the State.

On the South Shore, probably the area where cooting was almost a religion, one of the predominant industries was that of shoemaking.

While large factories were built that employed great numbers of the population, the shoe industry relied heavily on piece work, done by individual cobblers working out of small, so-called “tinker shops” or “ten footers” at their homes or farms. Obviously, shoe making required skills in cutting and sewing leather and accurately applying numerous small tacks. In addition, in the towns immediately along the coast, the age of sail was still in vogue. Canvas sails often needed to be sewn anew or repaired. Wooden boats had to be built and ribs bent to form their hulls and, finally, wooden hoops needed to be steamed to form the frames of the numerous local lobster pots (traps). All these skills, a knowledge of working with hand tools, the ability to sew heavy cloth, a familiarity with how to steam wood to make it bend and the competence with hundreds of small nails and tacks led to a breakthrough in local decoy design.

Out of necessity, the full-bodied decoys for coot were

placed across the body of the decoy. In the case of the “slats” the supports ran the length of the bird. By covering these longitudinal members, the decoy assumed a much more life-like form while still offering the opportunity to construct a large (in some cases very large) light weight decoy. While no one can be sure if the canvas coot decoys led to the construction of the goose decoys or the other way around, the result was a widely used, highly successful, technique. Occasionally this type of

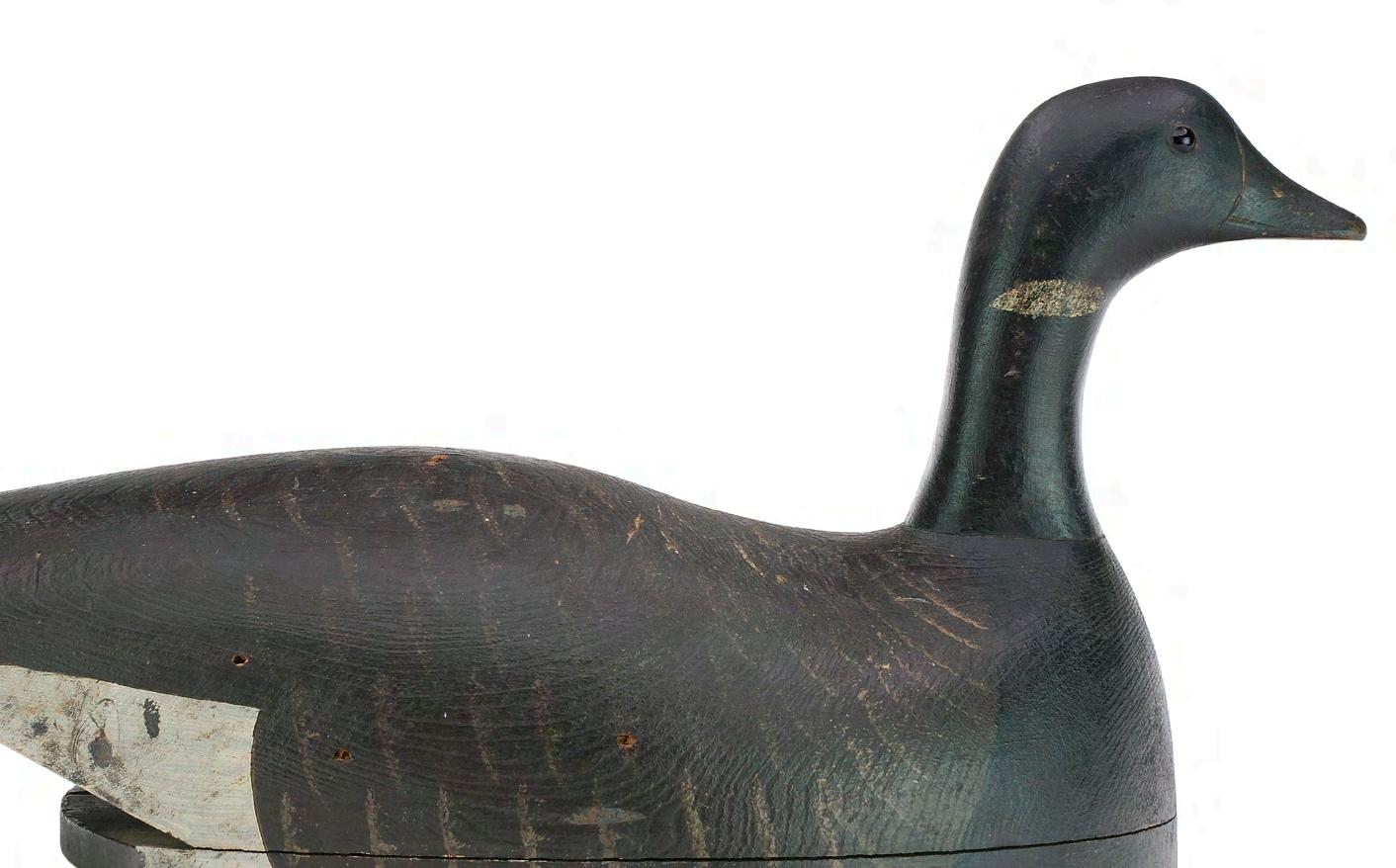

As with any other form of decoy, some men were simply more talented or fastidious than others. While many individuals utilized this type of construction, four that did exceptional work were Massachusetts’ Joseph Lincoln of Accord village (Hingham), Lothrop Holmes and Clarence Bailey of Kingston, and George Boyd of Seabrook, NH, just over the State line. Each of these men achieved a level of perfection in their work that distinguishes them from any and all of their counterparts.

This canvas over frame concept was occasionally used elsewhere in the country such as in the Carolinas. In these instances, however, the construction technique was different, normally utilizing a combination of wire and twine to form the backbone over which the canvas would be stretched. It is probable that this represents a form of convergent evolution where a similar solution to a problem was adopted independent of any knowledge of its use elsewhere.

Compared to the all wooden decoy, many of the canvas covered birds have suffered from the ravages of time or storage under less than ideal conditions. Finding one in excellent original condition today, by one of the best makers must be considered rare.

Addenda 1

“April 9th, 1860 Correspondence of the (New Bedford) Standard – “A GREAT DAY’S SHOOTING”.

Westport, Sat. Evening Mr. Editor:---Agreeable to my promise, and in accordance with your wishes, as implied in this day’s paper; I have learned the particulars relating to the events of this day’s shooting. In order to be fully posted up, your humble servant left home in the good boat Paquachuck, at 3 o’clock, repairing to the gunning ground, and was on the ground, some five miles from the wharves, at early dawn, witnessing all that transpired. There were thirty-five boats, all armed and equipped except your informant’s. As my object was mainly to see the sport, which I could not have done as well in engaged in shooting, I thought best to take no shooting iron. The whole number of fowl obtained 723, the largest number ever killed in a single day by our men. Fourteen boats obtained 79 fowl. These were manned by men less skilled in shooting than others. Twenty-one boats took 644; six of the twenty-one took 305. Mr. Charles Soule, the veteran sportsman, came in high hook, as we term it, having obtained 65. William Soule took 55, Capt. Benj. Gifford and P.G. Wing, 53’; Capt. Geo. Manchester took 48; Capt. E.P. Brightman 44, and Mr. Christopher Davis, 31. It is worthy of mention that Capt. Barney Gifford, who has passed his three score and ten years, was early on the ground and obtained, notwithstanding his great age, thirty-seven birds. This aged man resides at Hicks’ Bridge, 9 miles from the old cock, at the place where most of the fowl were killed. He must have left home in the small hours of the morning, as he was among the first on the ground, perhaps by the first dawn of day. He left home and returned the same day---eighteen miles travel. Had the wind blown on shore instead of off, no doubt 2000 birds would have been taken. Seven-eights of these fowl are what we call Pishaug, called by most persons in other places Coots. It is estimated that 50 lbs. of powder, 200 lbs. of shot and 3000 caps were used, at a cost of $20. The fowl, at the price here, will amount to $100, and the weight, one ton or 2000 lbs. There was at least two thousand shots made.”

No large clubs such as those commonly organized throughout the South, Chesapeake, Illinois River and Canada existed in Massachusetts. Rosters of the clubs at all of these locations, however, bear the names of numerous gentlemen from the Boston area who traveled there to enjoy fine gunning for canvasback, mallards and other fowl. The closest thing to these luxurious accommodations on the home front were a few of the elite striped bass clubs that did exist in the State. On the Massachusetts/ Rhode Island line, the West Island Club off Sakonnet Point and, on the Elizabeth Islands, the Cuttyhunk Bass Club and the Pasque Island Club would be typical examples. These clubs were extremely exclusive and catered to the most rich and powerful businessmen, politicians and professionals of their day. While the pursuit of the large fish was certainly the main objective of the members, a certain amount of waterfowling did occur.

In 1864, three men from New York “- - - purchased East and West Islands in the State of Rhode Island with all the buildings and personal property appertaining, formed an Association for Angling and Shooting purposes - - -“ . Thus was born the West Island Club, by far the most elite of all the bass clubs in New England. Members (limited to 30 at any given point) included US Presidents Grover Cleveland and Chester Arthur as well as business titans such as Cornelius Vanderbilt and Charles Tiffany. Numerous members of the Rockefeller Family and

noted sportsmen such as J.P. Morgan, John L Cadwalader and others often appear on the guest registers. Ultimately occupying eight buildings, accommodations were lavish, complete with private butlers, maids, cooks and waiters. Like all of the clubs, guests would have their own “chummers” who would bait the “stands” (fishing platforms), often with lobster. West Island members were so wealthy and influential that they had a private telegraph line installed to the Island so they could be kept abreast of daily stock reports. When the US government wanted to install a lighthouse on the Island, members were able to have the location of the beacon changed to another island nearby. The club records, now stored at the Newport (RI) Historical Society, list only the daily take of striped bass, but members would have certainly taken advantage of the fine shooting which the Island afforded. Wealthy Boston based East India Merchant, George Henry MacKay documents his numerous visits to the West Island Club between 1869 and 1892 where he and friends returned nearly every April in pursuit of the northern bound spring flights of scoters.

Certainly, one of the most famous of the bass clubs was The Cuttyhunk Bass Club which was founded in 1864 by members of the West Island Club seeking additional fishing ground. Located at the tip of the Elizabeth Island chain, which stretches southwest from Woods Hole, Cape Cod, the members enjoyed some of the finest bass fishing to be experienced anywhere on the coast. Like the West Island Club, membership was selective and included some of the most influential and powerful figures of the day. President Theodore Roosevelt was president of the club between 1901 and 1909 and William Howard Taft then assumed control of the club from 1909 to 1913. As with the West Island Club, members did not want for comfort. Rooms were well appointed, and meals were sumptuous. Each guest maintained their own liquor cabinet where fine wines and spirits were stored. An 1883 article in “Sport with Rod and Gun”, when discussing the club states: ”We hear, too, the notes of the upland plover, wildest of all game birds - - - - . A little later in the season, large flocks of golden plover will stop on their way south and make it lively for the grasshoppers - - - “ . One does not need much imagination to assume that, when the fishing was slow, the club members would have set out decoys in the moors for the migrating birds.

Seeking the company of their wives, or simply female companionship, the Pasque Island Club, was founded in 1866 by disgruntled members of the Cuttyhunk Club, where females were not allowed. There are newspaper articles from 1900, reported by the club, that indicate a female nurse from Fall River (MA) who was summering on the Island accidently shot herself while plover shooting. She was attended to by Dr A.L. Pidge of Philadelphia and well-known New Bedford (MA) hunter Dr E.R Sisson. Since the club owned the entire 853 acre island, and, as one author has commented, “their control over the shoreline was unyielding” , one can rightfully assume that the unfortunate woman and her attending physicians were hunting shorebirds while staying at the Club.

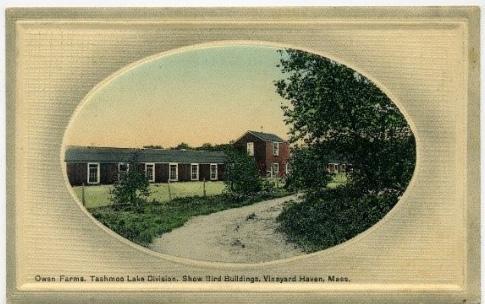

“Camps”

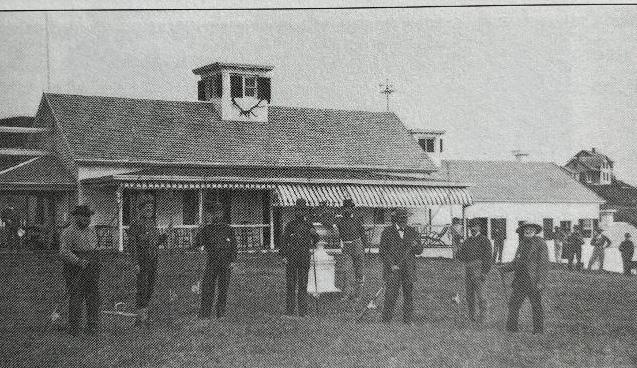

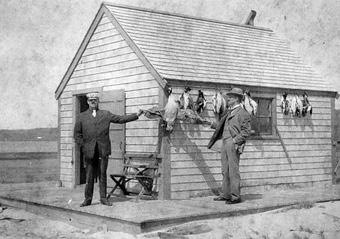

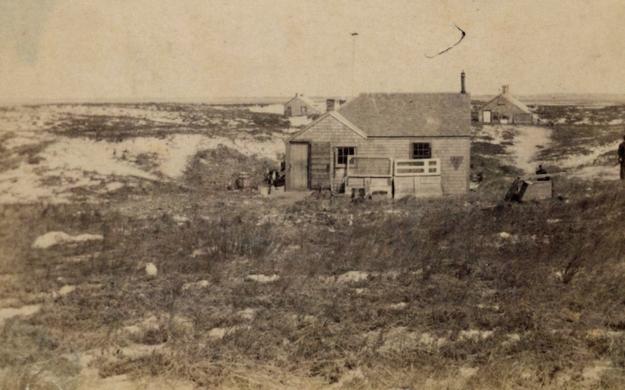

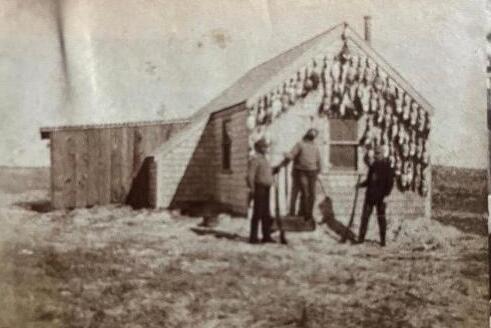

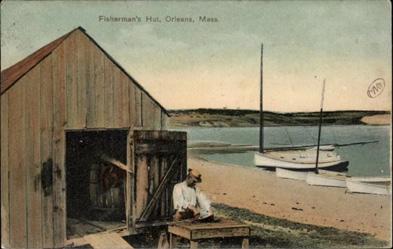

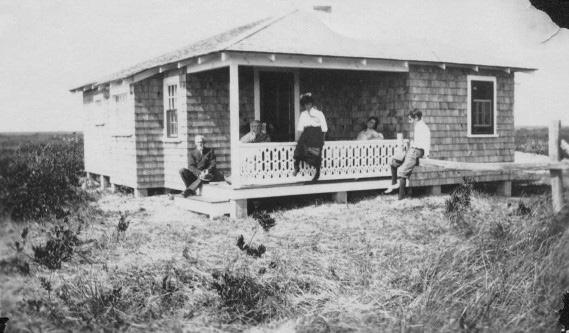

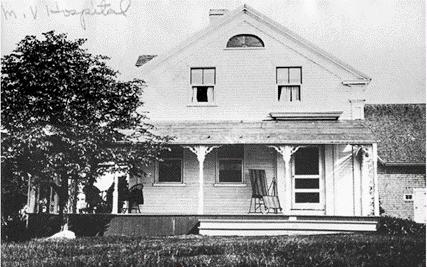

Untold hundreds of private duck camps once existed in the State. These camps were typically the domain of small clubs comprised of a few individuals that banded together to secure somewhat private hunting areas or, at least, ready access to such. The size of the camps ran the gamut from small houses with a few bedrooms, kitchen and living area to rustic one room cabins, some best described as shanties or mere shacks. Accommodations ranged from comfortable to merely adequate, but in all instances, certainly met the needs of the owners after a cold, wet and windy day afield. These buildings were usually located on a favored point or island adjacent to a pond, swamp or marsh that afforded good hunting. These were extremely common in the days of the wooden decoy and would have been familiar sights the entire length of the State and every popular gunning area saw multiple camps. The Cape, due to its relative remoteness, was dotted with these small buildings which served as hunting quarters during the season and as summer retreats when the birds were not flying. The camps differed from the “stands” in that the shooting area(s) were usually separate from the camp itself and the overall operation was far less complicated or involved. Normally, if live decoys were used at all, the flock would have consisted of simply a few ducks.

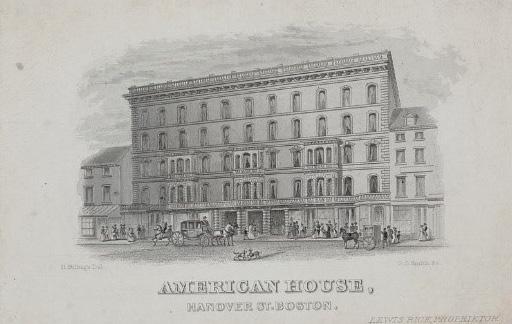

For those who did not have access to one of the numerous “camps”, a number of hotels sprang up at favored gunning areas to cater to individual visiting sportsmen. Often these would also offer guiding services as well as boats and decoys. These hotels could be found at all the major hunting areas from Plum Island in the north to Westport in the south and, as with the camps, these establishments offered various levels of accommodations.

Frederick Burden Head established a hotel on East Beach in Westport in 1876 to cater to hunters. He once boasted “As many as 150 hunters roomed at my house (in a season) in the early years when ducks and other fowl such as loons and quail were plentiful…I shot as many as 86 ducks in one day and shipped them to the markets in New York and Boston.”

As early as 1806, a group of businessmen banded together to build a bridge to Plum Island on the north shore and constructed a hotel there to house the workers. This was expanded over the years to a more elaborate edifice and was a favored destination for gunners who were attracted to the area.

Affluent Bostonian Charles Ashley Hardy knew the Cape well, for he had traveled frequently to the area on hunting trips since his youth. Confident that others would share his passion for the Cape, he encouraged a group of fellow investors to create a rustic hunting lodge in the quaint fishing village of Chatham on the outer arm of Cape Cod. In 1914, his Chatham Bars Inn opened and was immediately successful, attracting equally wealthy sportsmen to the area for the outstanding hunting and sailing it provided. Hardy went on to become one of Elmer Crowell’s earliest admirers and patrons and he was instrumental in introducing Crowell to similarly minded individuals. Expanded multiple times over the years, The Chatham Bars Inn remains today as one of the Cape’s most luxurious destinations.

These exclusive clubs, small camps and various hotels served the needs of the hunters not fortunate enough to live within easy traveling distance to good hunting. These were a necessity at a time when transportation was not as easy and convenient as it is today. Trips from Boston, Providence and beyond to the Cape or other rural areas would have been long, arduous undertakings often involving train or steamboat travel. Once one arrived at a favored destination, stays were usually for multiple days or perhaps even weeks. Fortunately, these were also the days when one could reasonably expect to enjoy good sport, in a pleasant, unspoiled environment, well away from the demands of his or her daily routine.

“ The stand gunner is, to say the best of him, a picturesque creature teaming with pond lore and weather wisdom, half goose, half philosopher. At worst he is a lazy, Rip Van Winkle sort of chap, carrying about with him a disdain for all things modern, and not improbably a taste for drink. As a rule he is harmless, though more or less frowned upon by upland shooters of a more sprightly and progressive type. His long suit is patience, and he lives from week to week hoping for a big storm which never arrives, or a great shot that he will surely pull off if he lives long enough. He sees many things as he leans over the board fence of his blind, things that happen in nature only at rare intervals, and he has some tall stories of remarkable happenings, many of which are true”.

(Dr John C Phillips 1928)

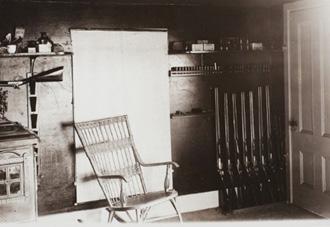

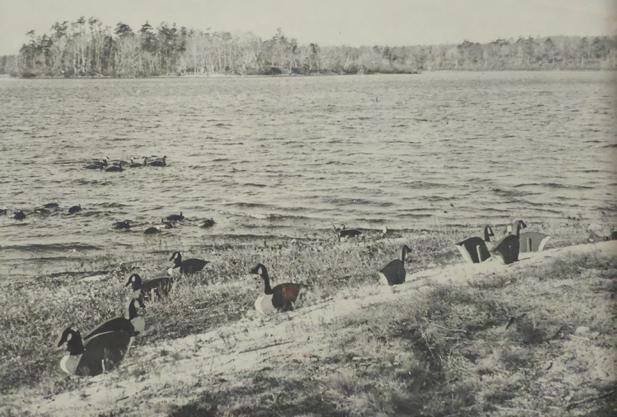

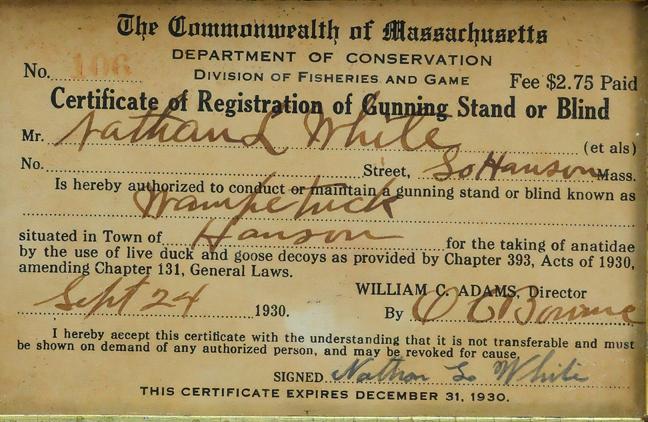

The “Gunning Stands” were considered unique to Massachusetts and the areas immediately adjoining in southern New Hampshire and southeastern Rhode Island. The primary purpose of the stands was to attract and harvest the migrating flocks of Canada geese, although all other species of passing ducks and shorebirds were also shot if the opportunity arose. They were located on large inland ponds, coastal salt ponds, favored marshy points or, occasionally, built directly on the beach. These were elaborate affairs consisting of a good size clubhouse/camp with sleeping, cooking and living areas, usually large enough to house six to eight hunters at a time. This was connected, either directly or indirectly via a covered alleyway or camouflaged “tunnel” to a “breastworks”. This structure varied in length, occasionally reaching perhaps over one hundred feet long, and served as the blind which would shield the hunters from the birds. There was no set design standard for this whole operation and the breastworks may or may not have been a roofed affair. These two core structures were augmented with additional storage buildings for equipment, wooden decoys and pens for the all-important live decoys.

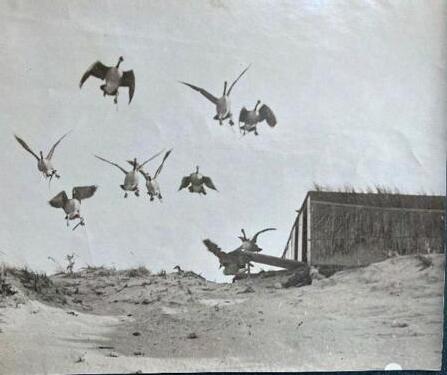

Sizable flocks of tame geese were the key ingredient to the success of the stands. The birds could have been obtained from the wild during molting seasons or they could have been purchased from commercial dealers. Mated pairs were separated into “flyers” and the “beach team”. Other stands favored separating the young from the parents into the two components (see addenda 1). All were labeled in some fashion, usually with leg tethers, to be able to identify them from their wild counterparts and not be accidentally shot, although this did regularly occur. John C Phillips once wrote a poem titled “Crowell’s Lament” where he recalls when the famous carver inadvertently killed one of his own live decoys. If a readily available and highly visible “beach” for the geese did not occur in front of the stand, one would be constructed, usually in the form of an irregular wharf type structure just above the waterline. These “beaches” were always sand covered so as to make the live decoys more visible from the air. The beach team was staked out in front of the breastworks in the area designated for them and the flyers were kept in a separate pen, either imme diately adjacent to the breastworks or, close by. Occasionally they would be staged in a tower. When a live flock was spotted, the flyers were released, either by pulling a string on the pen door, or, in more elaborate setups, by flicking an electrical switch to release the birds. O nce their mates were circling above, the beach team would begin to (hopefully) call aggressively and the flyers would then return to the beach.

This operation was aided by the use of extensive baiting and the flyers were usually withheld food on the day of the hunt so that their hunger would help insure their return to the beach. The number of live birds at the stands usually numbered between 50 and 100 depending on the size of the operation, but a particularly large stand in Plymouth County is known to have utilized between 300 and 400. In addition to carving his own decoys, Jim Look’s stand and guiding operation on Martha’s Vineyard would have been a typical operation (see addenda 1).

As an added attraction, large numbers of wooden decoys played an equal role in the deception. Often times these were grossly oversized “loomers” which were anchored out and left to remain for the entire season to serve as a visual attractor. Other wooden lures were arranged on large triangles in groups of three. These triangles were often attached to a pully line system where the ropes could be pulled, and the decoys would appear to be swimming in towards the beach. There were also one or more “range markers”, floating wooden decoys, set out to mark the 35 or 40 yard mark from the breastworks when the time came to call the initial shot.

The entire operation was not an affair to be taken casually. The camp needed to be maintained and the live geese housed year-round. Each year the breastworks, camp and adjoining structures needed to be newly brushed in. This required bringing in fresh material, either native vegetation or beachgrass from other areas so as not to denude the area of the stand. In addition to a caretaker, a “head gunner” was needed to serve as lookout/guide. This person was also the one responsible for determining when to call the all-important initial group shot. This multi gun barrage was first taken at the wild birds on the water and then additional loaded guns kept behind the blind were quickly put to use for a follow up shot at birds in the air or to dispatch cripples.

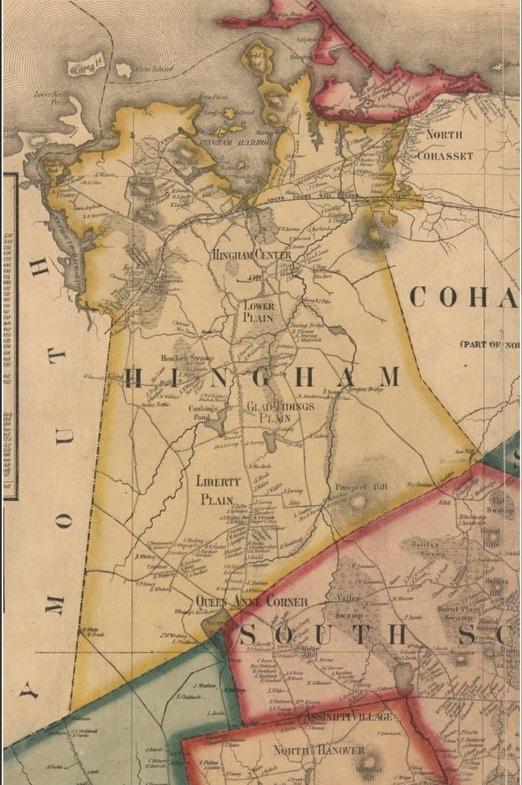

The stands were only occasionally the domain of a singular owner. A few very wealthy individuals such as Dr John C Phillips at his Wenham Lake property maintained their own stands and controlled the visiting guests. More commonly, the stands were maintained by small, tight knit clubs such as Joe Lincoln’s famous North Shore Gun Club on Accord Pond in Hingham. In terms of human convenience and finish, the operations ran the gamut of from simply crude to quite luxurious (see addenda 2).

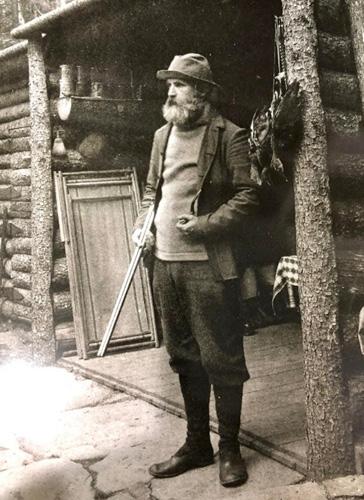

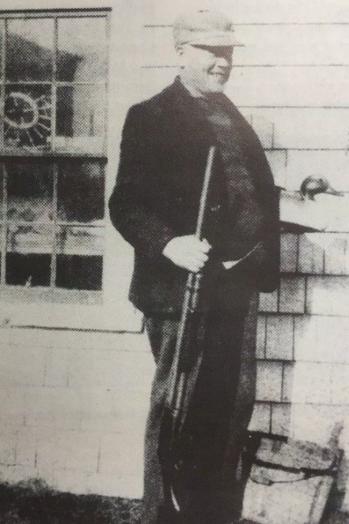

Elmer Crowell was considered one of the very finest of the live bird trainers, stand caretakers and head gunners. He was J.C Phillips private caretaker as well as serving in a similar capacity at the “Three Bears “camp of Charles Ashley Hardy, Loring Underwood and G Herbert Windeler on the Cape. In addition, he was often called upon to visit and gun at numerous other operations from the Rhode Island to the New Hampshire borders.

When discussing the Gunning Stands, one first usually draws a mental image of the live goose decoys and this was certainly the focus. The stands also maintained live duck decoys, and these were practically universally black ducks, although English callers could also be used. The goose beach was traditionally separate from the duck beach.

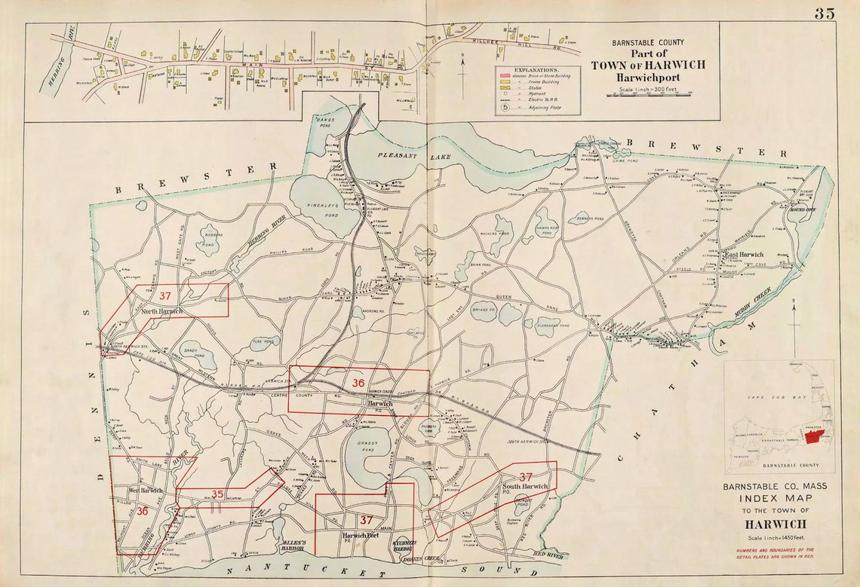

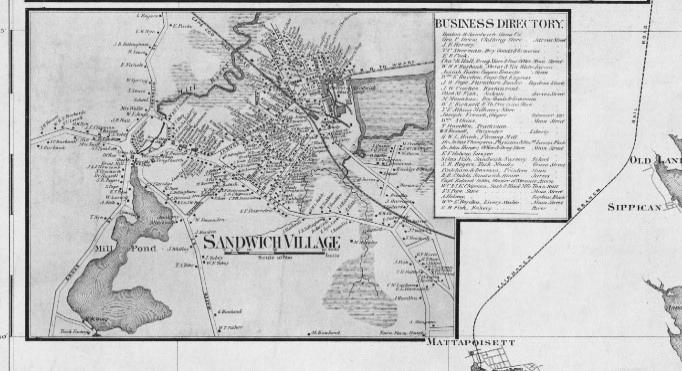

We are fortunate that a number of authors wrote period accounts of these stands. Russell Scudder Nye in his 1895 “Scientific Duck Shooting in Eastern Waters” describes a small stand in today’s Hyannis on Cape Cod. William Hazelton in 1916 described their operation briefly in his “Duck Shooting and Hunting Sketches” and Dr. John C Phillips penned an excellent period record of his knowledge of the Massachusetts stands between 1898 and 1928. In his “Shooting Stands of Eastern Massachusetts”, he reported that he felt that the tradition of the Stand first appeared south of Boston in the area of Bridgewater and Rockland where the shoe industry was the predominant source of income. Local cobblers worked on a piece work basis out of their homes and thus they were able to bring their work with them to the stands. Otis Foster, writing for the “Massachusetts Waterfowlers Association” in 1906, stated that there were stands operating on Oldham Pond on the South Shore as early as 1864.

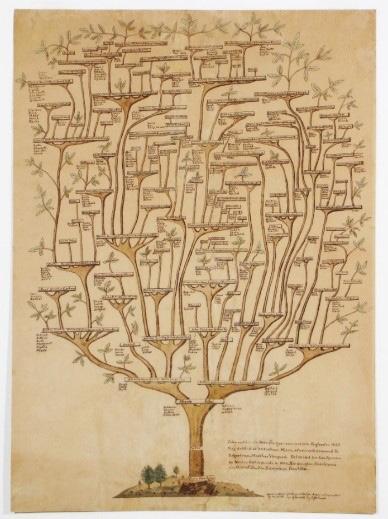

Over the years, individual stands came and went but by 1928, Phillips felt that there were between 180 and 190 in the State, but he was certainly not aware of them all. In his book, he does Include those in neighboring southern New Hampshire, but he does not record known stands in the Dartmouth/Westport area in the southeast part of the State, nor known stands in adjoining Little Compton, RI. He notes far fewer stands north of Boston than the areas to the south or on the Cape and Islands.

Phillips estimated that in 1928 there were between 5000 and 6000 live goose decoys in use in the State, in addition to a little more than half that number of duck decoys. These numbers include just the total for registered stands and not individual small casual blinds. The registered stands were supposed to report their annual bags to the State, but this was voluntary, and many operations were suspicious of reporting particularly large kills, so trimmed their reports while others, in order to appear more successful than they actually were, padded their numbers. Phillips states that he felt there was definitely more trimming than there was padding. Accurate or not, the State records the total number of geese shot at the stands to average about 4200 per year, with poor years numbering about 2500 to 3500 and good years upwards to 8500. Black duck kills averaged about 15,000 per year.

The outlawing of live decoys in 1935 put an end to the Gunning Stand in Massachusetts and the 1938 Hurricane virtually erased all physical evidence of practically all of the stands located in coastal areas.

The method of training utilized by James Look (1862 – 1926) at his stand at West Tisbury on Martha’s Vineyard would have been typical. It was recorded by a writer for the New York Times who interviewed George Magnuson in 1967. Magnuson had worked as a 19-year-old assistant for Look.

“Jim had more than 30 pairs of Canadian geese when I arrived. Their wings were clipped and they nested around the pond. When the eggs hatched out in late spring, Jim would walk up to the goose and gander and goslings with a handful of corn meal. In a few minutes some of the goslings would be eating out of his hand. These were the birds that would become flyers. The other less tractable goslings would become members o f the beach teams, geese that were staked out in front of the blind. But some would eventually be found unsuitable for this purpose also. A beach team member had to stand naturally at his stake. If he flopped around and tried to tug free, he was banished to a pen where his antics wouldn’t jeopardize the hunting. Each flyer team, and Look usually had 12, was a family unit made up of goose, gander and goslings with broods usually running from 4 to 10. In late summer when the goslings were able to fly, their training began. They were given no food for several hours, then released from their pens. The mother was caged at the entrance to the pens and the father staked out on the beach. After a short flight, the young birds would respond to their parents’ cries and their own hunger and return. This family bond functioned without fail for the first year, but few flyers w ere amenable to a two year stint” Look charged each of his paying hunter s a fine of $10 for any of his tame birds they accidentally shot.”

The Birch Point stand on Canton Resevoir was established c1865 by F.B. Jones and expanded upon annually untill shooting ceased in 1935. Initially a mere shack, the first camp was constructed by hand digging a huge cut into a hillside to accommodate the construction of the camp, and the excavated material provided the fill needed to construct a b each which extended practically around the entire point.

For most of its existence, Birch Point was a male only organization, as were practically all the stands. By about 1915, F.B’s sons, Fred E and Tom, ran the camp. When Fred married, his wife insisted on going to the camp and shooting as did the wife of another member, Mrs Walter Smith. This saw the transformation of the stand from a rather shabby operation into one of the more lavish in the State. A new beach was built which was surrounded by a camoflaged concrete wall and the camp and breastwor ks were totally rebuilt, complete with all the comforts of a second home.

As related in the log of the camp ”Many here were who said right out loud that a gunning stand was the last place in the world for a woman to locate herself”. “But - - the ladies came just the same and, wonder of wonders! No longer did the - - - men have to live a week on one can of corned beef, no longer did they have to sweep floors and make be ds, no longer did they wonder how long the dishes would hold out before they were dirty enough to heave in the lake, and no more did the married members of the camp shiver during the long cold nights”. “As for the gunning, they could shoot as well as any of us - - - “.

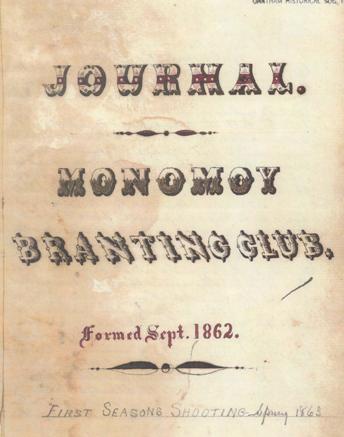

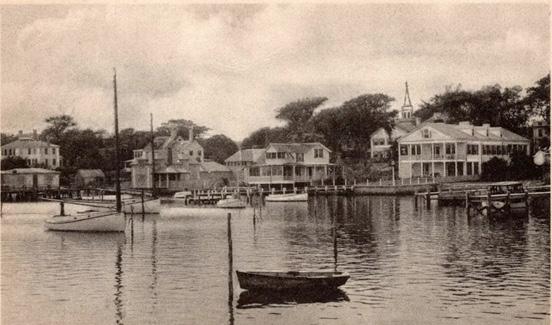

Located off the southern end of Chatham on the outer arm of Cape Cod lies Monomoy. Basically a long sand spit washed up by ocean currents, a great storm in 1887 breached the peninsula and resulted in what is now an eight mile long island surrounded by shifting underwater bars. The area has always drawn waterfowlers and, over the years, an array of small, private duck camps have occupied favored spots on the island. One unusual feature of Monomoy is that it attracted large numbers of migrating brant (Branta bernicla) on both their fall and spring flights. The birds were drawn to the area for its lush beds of eel grass (Zostera marina) which the birds readily fed upon, resulting in their developing a reputation as fine table fare. It was these small geese that drew the attention of both local gunners and sportsmen from as far away as Maine and Connecticut. In the early part of the 1800’s, accommodations near the island were sparse and simple at best. Eventually small groups of men banded together to form clubs for the exclusive purpose of hunting the birds. In many ways these clubs were similar to the famous goose stands throughout the State and in many ways they differed. The two most famous and long standing of the brant clubs were the Monomoy Branting Club and the Bristol Branting Club, both located near the northern end of Monomoy on Shooters Island and Inward Point.

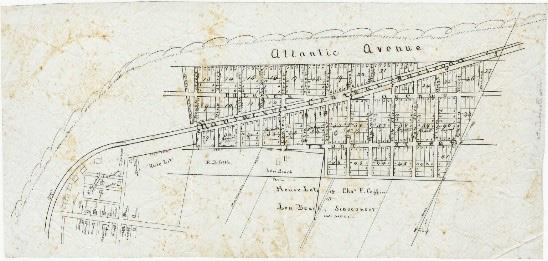

Fortunately, the Monomoy Club kept excellent records and they, as well as a number of period photos, have survived to document its history. Founded in 1862 by four locals or “resident “ members, and fifteen affluent men from the greater Boston area for the expressed purpose “ - - - to associate ourselves together for the purpose of branting at Chatham, Cape Cod under the name of the Monomoy Branting Club ”. The twelve articles that comprised the “Rules and Regulations” nicely outlined the operation of the club. Basically, the nonresident members were to be assessed equally to build and furnish a new shanty large enough to accommodate at least eight persons, purchase a suitable boat, boxes and all necessary implements except guns and gunning apparatus. In return, one or all four “residents” (Alonzo Nye, David B Nye, George Bearse and Washington Bearse) would be present at the club for the entire branting season which would run from the 1st of March to the 1st of May. Alonzo Nye (1823 – 1899) was to serve as general manager and he and the three others were to serve as guides and caretakers of the club as well as all of its boats, boxes, decoys and facilities. They were required to “ supply good and sufficient food for the members ” in addition to doing all the cooking and cleaning and “ looking generally after the welfare and comfort of the nonresidents ”. In turn, they could use all of the club facilities “ free of charge ” and “ have the privilege of inviting a friend ”. The nonresident members agreed to limit their time at the club to no more than 10 times per season, pay a fee of $1.00 per visit, and “ to arrange among themselves that no more be at the shanty at any one time than what it could accommodate ”. They, too, could invite a friend who would pay the same $1.00 per day and all nonresidents and guests would be entitled to “ an equal share of all the game bagged while he is at the shanty” . The remainder of the regulations related to the democratic management of the club where no new members could be admitted without a 2/3rds vote of the membership and members could also be expelled by a 2/3rds vote. The manager, also acting as president and treasurer, could charge assessments upon the membership and he would “ keep an account of all monies as well as a daily log of the “number of ducks killed, the weather, and club members present ”.

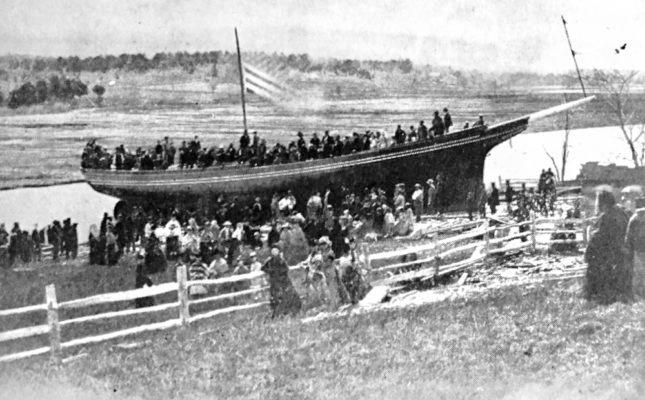

The early shooting at the club was exceptional. In the first yea r of operation, it is recorded that 375 brant were killed by one group of members in nine days and, in that same year, “ single shots which bagged from thirty to forty birds were not uncommon ”. As late as 1890, there are reports of “ stopping 17 brant with one discharge ”. Initially, decoys were not widely used, and pot shooting was common. When shooting on the wing became popular, live decoys were employed. These normally consisted of a few wing clipped birds that could be forced to “ call and flutter ” when a string attached to their legs was pulled. Wooden decoys appear to have been introduced about 1880 and, by 1896, the live decoys had nearly gone out of use. Whenever possible, the first shot was always taken on the w ater. A variety of wooden decoys were used at the clubs, most with a unique style named after the club. The most famous of these were a large number carved by none other than nearby artist A. Elmer Crowell.

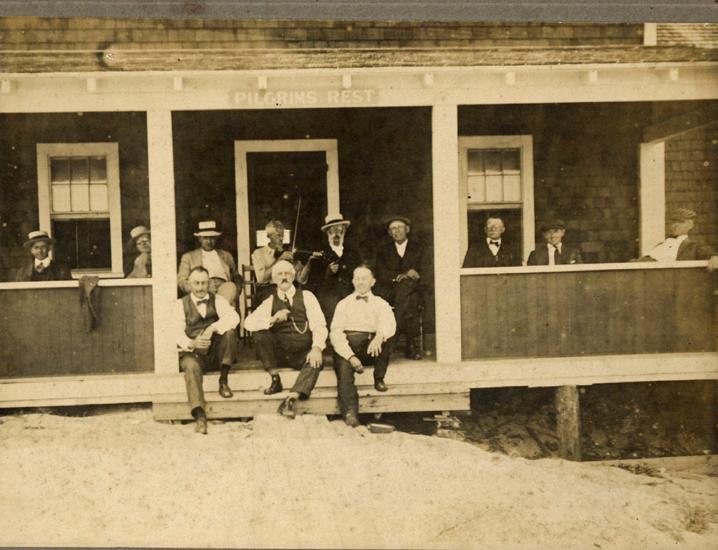

The membership would change multiple times over the years and new facilities would be added. Yearly meetings were held in Boston and many names well known in today’s decoy community, such as John C Phillips and Harry V Long, often were guests. One Joshua Nickerson recounted his visit to the club in November of the mid 1920’s. The rules by that time had been amended so that members “ were assigned to occupy the facilities in groups of their own choosing for a week at a time ”. At the time of his visit, “ the camp consisted of at least three buildings located on a small hillock of hard ground on Shooters Island ” at the northern end of Monomoy. The main building consisted of a kitchen and dining facility while the other two were primarily bunk houses.

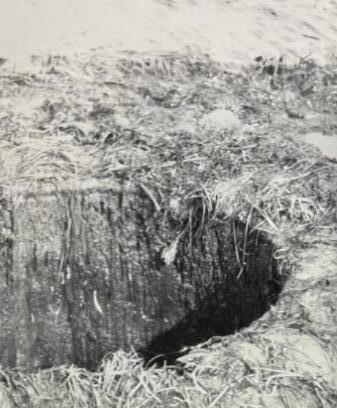

The daily operation was now under the control of a local manager (Will Gould) as well as an assistant manager and cook. All shooting was done from sink boxes. These were wooden structures roughly 6’x4’x3 ½’ sunk into holes dug in the marsh or shoreline at or below

These would normally have to be bailed out prior to their being occupied and would often become unusable as the tide rose, thus ending the shoot for that day and necessitating a wade back to firmer ground.

The Monomoy Brant Club was not alone on the outer Cape. Others existed that were shorter lived or, unfortunately, not as well documented. In 1886, the Monomoy Club merged with two smaller clubs, the Providence (Rhode Island?) Club and the Manchester (New Hampshire?) Club under the name of the parent Monomoy Club. Formed at roughly the same time as the Monomoy Club was the Bristol Club. This group’s buildings existed within eyeshot of the Monomoy holdings and was its biggest and longest lasting competitor. Like Monomoy, Bristol attracted a number of noted sportsmen and naturalists from throughout New England. Artist and taxidermist William H. Hoyt of Connecticut and Florida as well as noted Harvard trained ornithologist, Arthur Cleveland Bent of Taunton, MA, as well as many other sportsmen of note were members. On the mainland of the Cape, just west of the Island, was the Marlborough Brant Club. This was formed in about 1899 by five men, all residents of Marlborough MA, just west of Boston. Like the Monomoy and Bristol Clubs the accommodations at the Marborough Club would probably be considered somewhat spartan by today’s standards but the shooting, clamming, quahoging, and fishing were strong draws for a group of urban businessmen.

Until 1909, the vast majority of the shooting at the clubs was done in the spring. After that date spring shooting was abolished by law in Massachusetts and gunning was now restricted to just the Fall, resulting in greatly reduced bags The eelgrass which the brant greatly favored was decimated by a disease in 1931 and 32 (Wasting disease), and the birds were forced to seek alternate sources of food, greatly diminishing their attractiveness as table fare.

Storms and the never-ending shifting sands of the Cape would ultimately take their toll on the club structures. By the 1940’s, structural remnants of the Monomoy and Bristol Clubs could still be seen on the beach but, by the 1980’s, their location was hundreds of yards offshore under the breakers of Chatham Bars. A hurricane in 1944 saw the Marlborough Club shanty washed off its piers and it was reportedly last seen floating down Bass River. Today, most of Monomoy is a part of Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge which was established in 1944.

The “North Shore” extends from Salisbury on the north to Boston Harbor on the south. It is roughly bisected by Cape Cod’s lesser sister, Cape Ann. This rocky headland was known for its quarries, boatbuilding, lobstering (home to the famous “motif Number 1”), and offshore fishing fleets. To the north of Rockport an d Gloucester, lie the marshes of Salisbury, Newbury, Ipswich, Rowley, Essex and what is, unquestionably, the jewel of the areas duck hunting grounds, Plum Island. These vast salt marshes join with those of Seabrook in southern New Hampshire and are home to the famous Massachusetts soft shell clam. South of Cape Ann lie smaller, yet still important, marshlands bordering the town of Marblehead. Beverly was the home of some of the best known “Gunning Stands”, including that owned by Dr. John C Phillips at

Fortunately, the unique beauty and environmental importance of the area has long been appreciated, and much of the beach and marshlands fell under the jurisdiction of the Parker River National Wildlife Refuge in 1941.

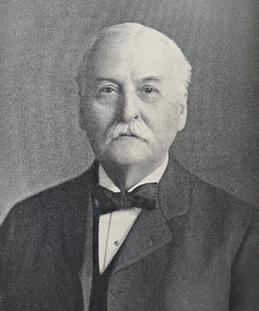

1879 - 1959 |

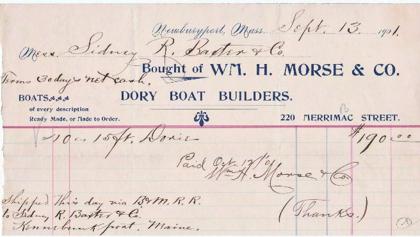

Fred Baumgartner was born on the North Shore, in Salem, MA. In the 1880 census, his Swiss born father, Phillip, listed his occupation as “Master Carbuilder” (aka carriagemaker). These woodworking skills apparently rubbed off on Fred who, by age 21, was living with the family in Worchester, MA and working as a laborer in a chair factory. Moving to Newburyport by 1902, he found work as a boatbuilder, and he would list either boatbuilder or carpenter/boatbuilder as his occupation for the remainder of his working life. On his WWI draft registration (1918), he stated that he was working for Wm H Morse and Co on Merrimac St. in Newburyport, and he remained with that firm through at least 1925. He never m arried and, for most of his life, boarded with the family of his brother-in-law.

Baumgartner was an enthusiastic sportsman and became friends with a similarly minded neighbor, Charles A. Safford (1887 – 1957) who lived a mere two blocks away from where Fred worked on Merrimac St. Safford was a trained silversmith and machinist who, by 1930 listed his occupation, like Baumgartner, as “builder – boat shop”. Reportedly the two men shared a woodworking shop on Merrimac St, so it is conceivable that they worked for the same boat builder. The two men worked off of the same patterns so their decoys are remarkably similar. The main characteristics that differentiate the work of the two men are that Safford, in addition to solid body decoys, would be the only one of the two to occasionally employ a woodworking method known as “scabbing”, where multiple pieces of wood would be joined together to produce the finished decoy. Baumgartner on the other hand, only carved solid body birds. The other defining characteristic is that Baumgartner’s decoys tended to be somewhat flat sided while Safford’s were more rounded. Paint patterns are similar, and both can be found with glass eyes and bill carving, while some of Safford’s omit the eyes and carving. Both can be found with roman numerals on their bases, and both may show evidence of being mounted on triangles. The two friends built neighboring gunning camps on Plum Island and, undoubtedly, occasionally hunted together. Both men carved only a very limited number of decoys and any example of their work is considered scarce.

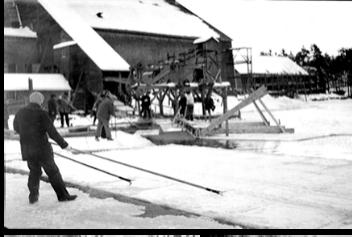

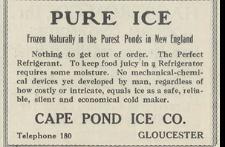

By the 1800’s, Gloucester, located near the top of Massachusetts’ North Shore, had earned its hard-won reputation as one of the premier fishing ports in America. Its schooners and their dories would venture to the Grand Banks and beyond, returning with holds brimming with codfish. As one would expect, many of the industries in town catered to the needs of the fleet. Hart’s father, Francis, was a fisherman, but his son choos e not to follow in that dangerous occupation and, by the time Charlie was 17, he was boarding at the home of ice dealer William A Homans and working “at (an) ice house” (presumably Homans’ “Cape Pond Ice Co”).

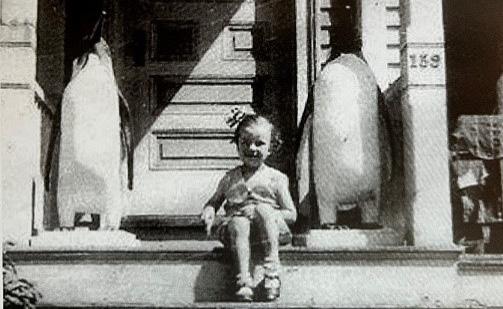

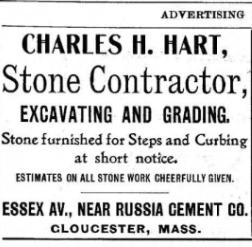

It is unknown how or when Charlie left the ice business and acquired the skills necessary to become a Stone Mason, but this was his listed occupation from at least 1890 through 1940 when he would have been 77 years of age. In 1900 he married Anette Appleyard and, by 1910, the couple had three children (Robert, Charles Jr and Grace). Since at least 1903, he conducted the mason business out of his home at 159 Essex Ave. in Gloucester where he would remain for his entire life.

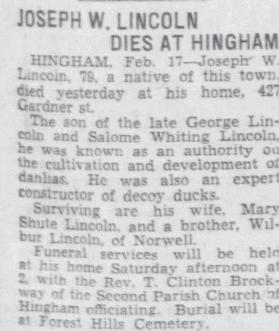

He enjoyed hunting and carved a variety of hollow and solid decoys for his own use. Reports indicate that he also offered some for sale through a prominent Boston store. He carved mostly black ducks, the preferred local target, and he also carved a limited number of other species such as teal and, later in life, whistlers. Perhaps his crowning achievement was a singular, incredible, standing black duck with flapping wings which was prominently displayed in the window of a local hardware/sporting goods store. His working decoys are considered among the finest to be carved on the North Shore.