Vol. 7 • No. 1 • Spring 2024

Office of Research and Sponsored Programs

TAKING TIME

Research programs provide resources relevant to Tennesseans

Vol. 7 • No. 1 • Spring 2024

Office of Research and Sponsored Programs

TAKING TIME

Research programs provide resources relevant to Tennesseans

Vol. 7 • No. 1 • Spring 2024

Office of Research and Sponsored Programs

Armed with MTSU grant dollars, one Tennessee county’s battle against an insidious disease—and a lethal stigma—offers hope for recovering opioid addicts

MTSU’s role in preserving a tiny east Tennessee church salvages the unique history of a rural community

Wild ginseng farming in Tennessee is a story of tenacity (and True Blue community)

MTSU’s Fermentation Science program plays a crucial role in Tennessee’s burgeoning distilling industry

University President Sidney A. McPhee • University Provost Mark Byrnes • Vice Provost for Research and Dean, College of Graduate Studies David Butler • Director, Office of Research and Sponsored Programs Rachel McGinnis • Vice President for Marketing and Communications Andrew Oppmann • Senior Editor Drew Ruble • Senior Director of Marketing Kara Hooper • Assistant Director of Marketing Keith Dotson • Design Brian Evans • Associate Editor Carol Stuart • Contributing Editor Nancy Broden • Photographers Andy Heidt, J. Intintoli, Cat Curtis Murphy, James Cessna • Special Thanks Jamie Burriss

Address changes should be sent to Advancement Services, MTSU Box 109, Murfreesboro, TN 37132; alumni@mtsu.edu. Other correspondence should be sent to Drew Ruble, 1301 E. Main St., MTSU Box 49, Murfreesboro, TN 37132. For online content, visit mtsunews.com/magazines. 630 copies printed by Lithographics, Nashville, Tennessee. Designed by MTSU Creative and Visual Services. 1123-2617 – Middle Tennessee State University does not discriminate against students, employees, or applicants for admission or employment on the basis of race, color, religion, creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, disability, age, status as a protected veteran, genetic information, or any other legally protected class with respect to all employment, programs, and activities sponsored by MTSU. The Assistant to the President for Institutional Equity and Compliance has been designated to handle inquiries regarding the non-discrimination policies and can be reached at Cope Administration Building 116, 1301 East Main Street, Murfreesboro, TN 37132; Christy.Sigler@mtsu.edu; or 615-898-2185. The MTSU policy on non-discrimination can be found at mtsu.edu/iec.

Tennessee’s state reptile, the Eastern box turtle (Terrapene carolina), never ventures far from its place of birth during its typical lifespan of 30–60 years. The peaceful creature usually reaches a length of fewer than 6 inches and has a shell of black or brown with spots of yellow, orange, and red.

This familiar terrestrial turtle occurs across the entire state, with the three-toed box

turtle (T.c. triunguis) subspecies found in the extreme southwestern corner of Tennessee and the Eastern box turtle (T.c. carolina) occurring across the rest of Tennessee.

Not unlike the box turtle, MTSU-led research and public service initiatives also canvas the state with localized impact. The often slow but steady progress of such endeavors best yields lasting solutions to the most difficult problems facing Tennesseans.

Transforming the present, discovering the future MTSU’s network of faculty and student researchers leads the way in Tennessee with more than 20 research centers, institutes, and support centers.

MTSU connects researchers with funding opportunities and ways to make a meaningful impact statewide, nationally, and internationally, through partnerships and strategic alliances with businesses and organizations.

• $3.6 million annual faculty research and creative activity investment by MTSU

• $12 million in external funding for sponsored projects in 2022–23

• Research opportunities at every level—undergraduate, graduate, faculty

Higher education research is a great investment for people and society. Researchers, faculty, staff, and students at Middle Tennessee State University are involved in research and public service initiatives that help Tennesseans.

This edition focuses on Taking Time to tell the stories of how MTSU research is impacting fellow Tennesseans in our surrounding communities. Through partnerships from across the state, MTSU is changing lives in key areas of health and wellness, history and heritage, agriculture and agribusiness, and commerce and industry.

This magazine highlights a small number of the many projects for Tennessee ongoing at the University. In this issue, we feature four stories that dive deep into how federal and state grant dollars at MTSU play a pivotal role in battling the opioid epidemic, preserving the history of a tiny east Tennessee church, farming wild ginseng, and expanding the distilling industry through our Fermentation Science program.

These stories of tenacity, preservation, and hope showcase our commitment at MTSU to help the citizens of the state live better and more rewarding lives.

David Butler Vice Provost for Research and Dean, College of Graduate Studies Leeanne Harris at her Wilson County home

Leeanne Harris at her Wilson County home

In 2021, Leeanne Harris gave birth to a boy and gave him away. If he couldn’t go home with her, she thought, he could at least go home with his big brothers, ages 2 and 5. They’d been adopted by a family friend.

“That’s the major thing—I had to sign custody over of my oldest two,” Harris said. “When I had my third, I also gave him up, because I wanted them all together. I didn’t want them to be separated.”

Harris, who lives in Lebanon, lost custody of her three children because she’d lost battle after battle against meth and heroin. She’d tried rehab, including medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with suboxone, several times without success.

That’s the way addiction often looks, said Dr. Josh Wienczkowski, because addiction is a chronic disease. Wienczkowski is medical director at Lebanon-based Cedar Recovery, where Harris had tried and failed to get clean with MAT.

Just like cancer, diabetes, or high blood pressure, substance use disorder (SUD) is characterized by periods of relapse and remission. It’s unrealistic to expect full recovery after a single course of treatment, Wienczkowski said. And with SUD, as with other chronic diseases, recovery can be complicated by depression, financial hardship, or any number of internal or external stressors. The important thing is to keep trying.

“What’s comforting is that current literature shows the vast majority of those with SUD will recover fully—over 70%,” he said. “And time in both treatment and recovery only increases that number.”

Harris can’t recall exactly how many times she tried MAT, and she’s not sure what made the last time different. All she knows is she was desperate to see her kids, including her baby, so she tried it again, and it stuck.

“I WANTED TO BE IN MY KIDS’ LIVES,” HARRIS SAID. “I WANTED TO WATCH THEM GROW. ”

Over the next year, she got clean, got a job, got a car. Then she lost TennCare, her government health insurance. It had been paying for her medication and counseling at Cedar.

The forward momentum stopped.

“I wanted to be in my kids’ lives,” Harris said. “I wanted to watch them grow. But it seems like when one little bump comes up, and you’re in recovery, you want to give up.”

That’s where she was—about to give up—when she got the call from Wienczkowski. Thanks to MTSU and a volunteer group, DrugFree WilCo, he had grant funding to continue her treatment.

Harris is convinced that the grant saved her life. Given how lethal opioid overdose is (see sidebar, page 11), that could very well be true.

The opioid epidemic has hit Tennessee hard. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ranks the state second for the rate of opioid prescriptions dispensed per 100 persons. For people susceptible to SUD, an opioid prescription can lead to fatal addiction. Between 2011 and 2021, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation, opioid overdose deaths increased by 240% in the nation overall and 350% in Tennessee. In 2021 alone, there were 63 opioid-related deaths in Wilson County, where Harris lives.

The Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (RCORP) grant from the Health Resources Services Administration offers a lifeline for people like Harris, who face financial or logistical barriers to MAT. Paul Trivette, chief strategy officer at Cedar Recovery, said even if someone can’t afford inpatient rehab— the ideal first step for treatment—the grant provides continued access to suboxone, which controls opioid cravings but is extremely expensive. Having that medication can keep people from sinking until they learn how to swim.

As Trivette put it, “You can’t treat dead people.”

It was the death of Thomas Tapley, a young Wilson County resident who appeared to have beaten addiction, that inspired the founding of MTSU’s grant partner, DrugFree WilCo. Tapley overdosed days before he was set to play a leading role in The Piano Lesson at Lebanon’s CenterStage Community Theatre.

When Tapley’s mother asked Wilson County Mayor Randall Hutto to do more to address the opioid crisis locally, Hutto assembled a team of civic leaders to explore solutions. One of them was Michael Ayalon—then president of Lebanon’s Rotary Club, and now a doctoral student at MTSU.

The solution they came up with was an innovative collaboration of 12 community sectors from Wilson County, including schools, businesses, faith-based organizations, the health care system, and courts and law enforcement.

DrugFree WilCo tackled the crisis from several angles. With an initial Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Program grant of $532,000, they placed a reentry transition specialist inside the Wilson County Jail, to give inmates with SUD a better chance of staying clean after incarceration. They established the Preventing Incarceration in Communities (PIC) Center, a prison-diversion program designed to decrease crime, reduce recidivism, and combat addiction. They raised public awareness about SUD through educational programs at businesses and schools. They distributed naloxone, the nasal spray that can reverse a potentially fatal overdose.

It was a lot, Ayalon said, but it wasn’t enough. If they were going to solve the opioid crisis in Wilson County, they needed more funds.

So he teamed up with Cindy Chafin, director of MTSU’s Center for Health and Human Services. Chafin secured two RCORP grants—an initial $200,000 for 18 months of planning and then $1 million for three years of implementation—to break down more barriers to MAT, from lack of insurance to lack of transportation to treatment.

Ayalon assumed the role of Wilson County RCORP coordinator, the liaison between MTSU and DrugFree WilCo.

The RCORP grant is what kept Leeanne Harris from giving up and going under. At press time, she was well on her way toward two years clean and sober.

Some barriers to treatment begin as misconceptions. MTSU and DrugFree WilCo are taking those on too.

Viewing addiction as a moral failure rather than a chronic disease can prevent people with SUD from seeking treatment. It can also prevent government investment in effective solutions. So, part of the RCORP grant has gone toward education, Ayalon said. It’s paid for a countywide billboard campaign promoting treatment and recovery. It’s funded MAT training for the county’s law enforcement officers.

Cindy Chafin, director of MTSU’s Center for Health and Human Services

Cindy Chafin, director of MTSU’s Center for Health and Human Services

It’s paid for annual assessments of the effectiveness of DrugFree WilCo’s efforts to destigmatize SUD.

They’re making a measurable difference, Ayalon said. But there’s more work to be done.

“I think there’s still some hesitation and concerns with medication-assisted treatment that need to be answered for the community,” he said.

He hopes to alleviate those concerns by offering educational programs at churches and hosting lunch ’n’ learns with community leaders.

One thing that’s hard to quibble with is the cost-effectiveness of preventing and treating SUD.

“Investment of time, energy, resources, and money into substance use disorder treatment has one of the highest return rates to society of all diseases,” Wienczkowski said.

Every dollar spent on SUD treatment saves $4 in future health care costs and $7 in criminal justice

costs, he said. Every dollar spent on evidencebased interventions—as opposed to “just say no” programs—saves up to $58 in future costs.

Then there’s the incalculable return on investment: lives saved, relationships repaired, families salvaged, trauma averted.

“Investing in substance use disorder treatment means not only helping an individual return to a fully functional member of society; it means generational change where we impact their entire family, support system, and community,” Wienczkowski said.

That can be a hard sell in a country that has historically treated addiction with ostracization and punishment, despite lack of results.

“If incarceration cured substance use disorder, the U.S. would be leading the world in recovery outcomes, not overdose deaths,” Wienczkowski said.

As program director of the PIC Center in Wilson County, , Derrell Seigler has witnessed the transformative power of effective SUD treatment. Since he founded the center in 2021, it’s had 50 graduates—50 successes measured by six-month treatment program completed and prison sentence averted. Every one revealed the human promise behind the disease.

“I have testimonies of people saying how it changed their lives,” Seigler said. “They’ll go to court and the judge will say, ‘You look completely different.’ A lot of these clients have even had their fees and court costs dropped. Everything’s been covered. To me that’s where the recidivism comes in. When someone doesn’t feel like they have support or have somewhere to go . . . they’re going to go back to what they know.”

He recalled one woman who came to the PIC Center having failed three different treatment programs. Seigler found a program that worked for her, and she turned her life around, eventually reuniting with her adult daughter.

Most people don’t see that side of the addiction story, he said. They just see the addict and think, She’s always been that way. And she’s probably going to die in jail

Trivette understands that narrow view as well as anyone.

Before he became an addiction-treatment professional, he was a registered lobbyist. His job was to convince lawmakers that addiction is a chronic disease and that MAT is worthy of public investment.

Before he was a lobbyist, he was a police officer in Bristol, Tennessee. Law enforcement works on the front lines of the opioid crisis. Trivette’s first day as a cop, he got a call from the Los Angeles Police Department. His dad had died of an overdose.

Opioids, a class of drugs naturally derived from the opium plant, include prescription medications like hydrocodone, oxycodone, codeine, and morphine; the illegal drug heroin; and synthetic medications like fentanyl.

It’s not uncommon for someone with substance use disorder (SUD) to become addicted after being prescribed opioids for pain relief, and then turn to street drugs when their legal access dries up.

What makes opioid addiction uniquely dangerous is the high risk of death from a single use, said Paul Trivette, chief strategy officer of Cedar Recovery in Lebanon.

Most drug-related deaths result from the physiological damage caused by prolonged, heavy use, he said. It’s rare for someone to die overnight from drinking alcohol, for example, or from ingesting stimulants like cocaine or methamphetamines.

But one overdose of opioids can cause potentially fatal respiratory depression. And for an opioid addict, the cravings are physically overwhelming.

“If someone is using heroin and they quit cold turkey, or if they go without it for some period of time . . . the brain signals to them, You need more opioids so you don’t die,” Trivette said.

The presence of fentanyl in meth and other street drugs has ratcheted up the danger level, he added. While fentanyl is used medically at microgram strength as anesthesia, it’s used illegally at milligram strength, which is a thousand times more powerful.

“That’s why opioids are such a difficult battle for people,” he said. “Because of the high rate of death, the withdrawal symptoms that it causes, and the fact that you think that you’re taking a certain amount of the opioid, and you’re actually taking a lethal dose and you don’t wake up again.”

The Rural Communities Opioid Response Program (RCORP), which awarded $1.2 million in grant funding to MTSU and DrugFree WilCo, is one of several government initiatives addressing the opioid crisis. As a result, it’s getting a little easier to help uninsured people pay for suboxone, the expensive medication that suppresses the intense symptoms of opioid withdrawal, said Paul Trivette, chief strategy officer at Cedar Recovery in Lebanon. A bigger barrier to treatment now is lack of transportation.

DrugFree WilCo is using the RCORP grant to take on that problem too.

When patients don’t have to worry about how they’ll get their medication, Trivette said, “we can help them focus on getting a job if they need one, getting their children back if they’ve lost their children, maybe building relationships back with their family and friends that they lost, maybe food insecurity. We can start addressing those things because now their mind is not so focused on not being dopesick.”

One of the main reasons people fail to follow through with medication-assisted treatment is that they can’t get where they need to go to receive it, he said.

That’s an especially common problem for clients at the Preventing Incarceration in Communities (PIC) Center, established by DrugFree WilCo at Cedar Recovery as a prison-diversion program for first-time drug offenders. Often people who’ve been ordered to receive treatment don’t have a driver’s license or reliable transportation.

The Wilson County-based PIC Center partnered with Uber Health to get people to their court-ordered appointments. It also uses donated funds to buy bus passes or subsidize personal transportation.

Derrell Seigler, program director at the PIC Center, said they’ve helped about a fifth of their clients get to treatment this way. The most expensive trip was a $118 Uber ride to downtown Nashville.

Not much for a ticket to life and freedom.

Trivette's dad had already served time in Tennessee for stealing from Paul and Paul’s mom. He’d fled to L.A. to avoid arrest after breaking into his brother’s house.

“Two weeks before he died,” Trivette said, “my father left me a voicemail that I still have to this day, telling me that he was sorry, that he loved me. I refused to call him back. I wish I hadn’t.”

It took nearly five years for Trivette to think about his dad, and addiction, in a new light. The change began when Matthew Hill, a state legislator at the time, asked him to work as an advocate for people with SUD.

Trivette initially declined, saying he didn’t accept the premise that addiction was a disease.

“I know what it’s like,” he said. “I see what it’s like on the streets.”

Hill pushed back, acknowledging that he once felt the same way. He invited Trivette to attend a discussion of SUD by clinical professionals, including Dr. Loyd Stephen, chief medical officer of Cedar Recovery.

Learning how opioid addiction rewires the brain was powerful medicine for Trivette. For the first time, he understood what his father had been up against.

EVERY DOLLAR SPENT ON EVIDENCEBASED INTERVENTIONS . . . SAVES UP TO $58 IN FUTURE COSTS.

“That’s why I want to be part of the change now,” he said. “To help other families and other people that have been impacted by addiction maybe have another mindset, maybe not stigmatize their loved one that’s battling an unbelievably powerful illness—so much so that the very thing that your brain desires will be the thing that kills you.”

“TWO WEEKS BEFORE HE DIED,” TRIVETTE SAID, “MY FATHER LEFT ME A VOICEMAIL THAT I STILL HAVE TO THIS DAY.”

Harris is now almost two years in recovery, has moved into a a shift lead position at Goodwill, and gets to spend time with her young sons.

Leeanne Photo by Andy HeidtKeeping people alive. For DrugFree WilCo, that’s the bottom line, and they’re always pursuing new strategies to do it.

At the top of Ayalon’s wish list is ODMap, a webbased tool that tracks overdoses in real time. A cluster would indicate the presence of a particularly lethal batch of drugs.

“I DON’T GET TO TAKE THE BOYS AND LEAVE WITH THEM,” SHE SAID, “BUT I CAN VISIT THEM, SPEND TIME WITH THEM, GO WHEREVER THEY GO.”

“If suddenly we see three or four overdoses on the same block, that tells us there’s a problem in that particular community,” he said. “So we would dispatch a mobile unit to that area fully stocked with naloxone and fentanyl test strips.”

Ultimately the goal is to buy time. To give struggling people one more try at living.

Leeanne Harris got another try at motherhood, albeit on new terms.

“I don’t get to take the boys and leave with them,” she said, “but I can visit them, spend time with them, go wherever they go.”

Last Halloween when they went trick or treating, she went with them.

One more try, one more day, one more moment.

“It was amazing,” she said.

The Center for Health and Human Services at MTSU helps improve the health and well-being of Tennesseans and that of the nation by collaborating with public agencies and private nonprofit and for-profit organizations.

• Serves all 95 counties in Tennessee and the campus community

• $12 million+ in grants for community programs and research projects

• Activities ranging from a rural opioid recovery mobile unit to smoking cessation efforts for pregnant women

CHHS relies heavily on external funding

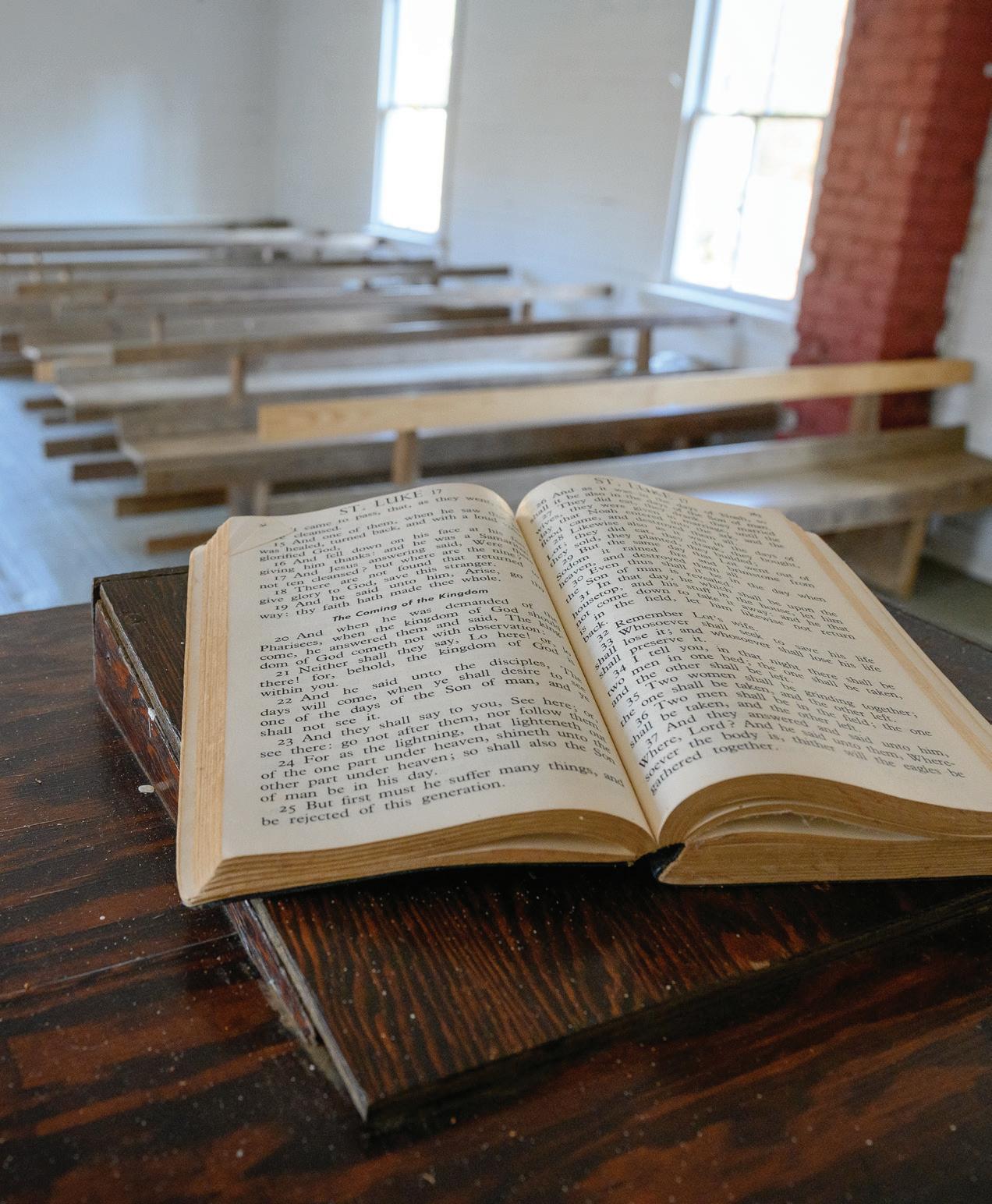

Beth Salem Presbyterian Church in McMinn County

Beth Salem Presbyterian Church in McMinn County

Beth Salem Presbyterian Church is now easy to find. You take the Riceville exit off I-75, just north of Cleveland in east Tennessee, and follow your GPS across and around gentle hills to a flatter area between Athens and Etowah, in McMinn County. On Arbin Watson Road, you’ll pass modest ranch houses separated by fields, then you round a bend and there it is. Closer to the road than the houses were.

It’s not the church itself that’s striking, although the church is the first thing you see. Its lines are so simple (clearly there’s a single room inside) and its coloring so stark (whitewashed weatherboard, plain white front door, white shutters over the windows on both sides) that it stands out against the grass and trees.

What’s striking is the feeling of community even though there’s no one there—unless you count the folks in the graveyard across the road. A few yards away from the church, off to the side, there’s an outdoor kitchen. A respectable distance behind the church, and from each other, sit two sturdy outhouses, doors ajar.

Beth Salem sits there waiting 364 days a year. It’s rewarded at homecoming, the fourth Sunday of August. Every year since 1955, families have gathered at the church from as close as Athens and Etowah, and as far away as Cleveland, Sweetwater, and Loudon, to celebrate a community and a sanctuary.

They also came home to keep the church from falling apart, said Ann Hitchcock Boyd, who still lives close by. A descendant of one of the founding families, she was 5 years old that first homecoming; now she’s 73. The folks who gather there from far away seem to be getting fewer, she said.

Hettie Dickey (l) and Ann Hitchcock Boyd

Hettie Dickey (l) and Ann Hitchcock Boyd

Boyd tends to the church herself much of the year. Her parents and her brother Bennie used to tend it too, before they joined the older generations across the road. The younger generations are busy with living.

What the church represents, and the responsibility to preserve it, weighs heavily on Boyd. The place is tangible evidence of a story that’s been mostly told, not written.

“That was the piece of history that I could walk through,” she said. “I can walk into that church and know that I had ancestors that walked into that church, that had religious services at that church, that walked on those grounds. And you know, sometimes I can feel that presence when I’m there. I can walk over to the cemetery, look at some of the markers, and feel like that’s home.”

There are three markers in front of Beth Salem Church.

One marker, erected in 1999 by the National Register of Historic Places, designates it as the first African American congregation established in the region of Polk, McMinn, and Meigs counties.

The church was organized in 1866. Its members, newly freed and illiterate by design, initially met under a brush arbor, then built a log church on donated land. The original log structure, which also served as a school, was destroyed by fire in 1920. Friends and neighbors pitched in to build a new church. That’s the shuttered one that stands today.

Another marker, erected in 1928, is a monument to the congregation’s original trustees and its founders: the Rev. George Waterhouse and the Rev. Jake Armstrong, two Black ministers; the Rev. Fate Sloop, the white Presbyterian missionary who helped them; and Martha Patsy Fite, the white woman who donated the land.

A third marker, from 2020, tells a little more about the unincorporated area known as Beth Salem.

THE PLACE IS TANGIBLE EVIDENCE OF A STORY THAT’S BEEN MOSTLY TOLD, NOT WRITTEN.

Beth Salem Church was always more than a spiritual sanctuary for its African American congregation. It was their social hub, and for its first decades, it was their school.

After that, but before desegregation, many Black children in the rural South, including east Tennessee, went to Rosenwald Schools. Funded in part by philanthropist Julius Rosenwald, 5,000 of the schools were built in the South between 1917 and 1932 to give Black children a state-of-the-art education.

In 2002, the National Trust for Historic Places put the Rosenwald Schools on its 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list.

There were two Rosenwald Schools in Etowah, where Ann Hitchcock Boyd and her mother were raised. By the time Boyd started school in 1955, it was no longer a Rosenwald School—it had been remodeled. And she didn’t go there long. But what she recalls about it lines up with how her mother used to describe the two-room schoolhouse.

The memories came flooding back when a friend told her about the Dunbar Rosenwald School in nearby Loudon. He’d gone to school there, and it was still intact. Some people were trying to preserve it.

Boyd, who’d been working with MTSU’s Carroll Van West to preserve Beth Salem, offered this advice: “Well, the first thing you need to do is get it approved as a 501(c)(3). Then get Dr. West to do a preservation study.” They took it.

With plenty of elbow grease, a solid preservation plan, three grants Boyd won, and support from the Loudon community, they were halfway through renovations in 2023. Just in time to celebrate the little school’s centennial anniversary.

Once an integrated community of subsistence farmers, it hollowed out as folks left for industrial and service jobs. According to the marker, regular church services ended there in the early 1950s. Boyd thought it was earlier. Either way, it marked the end of a long decline.

“When the railroad and things came to Athens and Etowah, young men didn’t have to farm anymore, and they went to work in the factories,” she said. “So they quit having church in the church altogether. That’s when it fell into disrepair.”

BY THE LATE 1990S, THE CHURCH WAS STARTING TO SHOW ITS AGE . . . PEOPLE AND MEMORIES WERE TRICKLING AWAY.

The marker includes a black-and-white photo of little Ann in Sunday clothes, standing with her family near the church in 1955. She doesn’t remember that first homecoming, she said. But she sure remembers the ones after that, because she got to dress up and eat dinner outside.

“There was no running water, but there was a big spring down at the bottom of the hill,” Boyd said. “I always thought it was fascinating to use a dipper to have a sip of spring water.”

One of the best parts of homecoming was getting to see friends they hadn’t seen in a year.

“It was one of the few Sundays that my dad would get excited about going to church,” she recalled with a chuckle. “He didn’t get excited about going to our local church in Etowah. But when it was time to go to homecoming at Beth Salem, he’d make sure there was plenty of food in the car and we left home early.”

Her dad loved homecoming even though he didn’t grow up in Beth Salem, she added. These were her mom’s people.

Hettie Dickey in the new pew behind where she sat as a young girl

Over the decades, the stories Boyd heard from her mom’s people became as fascinating to her as that dipper of spring water. Some were fluid, as oral histories tend to be.

As Boyd understands it, her great-great-grandmother Sylvia was born into slavery in South Carolina. Near the end of the Civil War, she and her three children were separated, sold to different farms in the McMinn County area in Tennessee. When the war ended and Sylvia was freed, she went in search of her sons and her daughter, Daphne, traveling from farm to farm in a rickety mule-drawn wagon.

When Daphne saw Sylvia drive up, she hadn’t seen her mom in two years.

According to the story Boyd shared with the Black Christian News, 15-year-old Daphne “jumped into the wagon without looking back. Years later, she told family members that even if she lived to be 1,000 years old, she would never forget the day that her mother came to get her.”

To Boyd, she’s Grandma Daphne, her mom’s mom and the family historian. Boyd’s mom passed away more than 20 years ago, and of course Daphne’s been gone longer than that—her resting place across the road from the church.

There are few people left who can give a firsthand account of Beth Salem when it was a thriving community with a vibrant church at its center. One of them is Hettie Dickey.

Dickey remembers how women would gather at the church on Saturdays to stuff ticking after the men had harvested the hay. Changing the mattress straw was part of spring cleaning.

“The hay back then wasn’t as hard as it is now because they had different machinery,” Dickey said. “They used horses and had different machines. It wasn’t like this motor stuff. We got everything motorized now.”

She and her twin sister were 2 years old when their father died, leaving their mother with seven children to raise. Their mom later told them he died of

pneumonia after he began catching rides to work in the back of an open truck.

Dickey still remembers how she and her siblings would run out to the road to meet him when they’d see him walking home from his job in Athens.

“We would always run to meet him, and he would always have some candy. That’s the only thing I remember—except I remember his funeral. Somebody picked me up to view his body. I still remember that. But that’s all.”

At 87, Dickey remembers going to regular church services at Beth Salem. She laughs when she remembers her Sunday-school teachers, widowed sisters named Mary and Mandy, bickering with the preacher, Walter Dotson.

But there’s nobody left to remember the earlier days when Beth Salem was not just a church but a school.

By the time Dickey was old enough for school, there were Rosenwald Schools all over the South, including rural east Tennessee, so Black children could get a formal education (see sidebar, page 20).

The only thing left in Beth Salem Church from those earlier days is the homemade chalkboard behind the pulpit. It hangs high on the wall, and there’s a bullet hole in it. The shot came from outside. Nobody remembers what happened.

By the late 1990s, the church was starting to show its age, and Boyd was getting worried. People and memories were trickling away, but the church was still solid. She wanted to keep it that way.

What Boyd remembers most about MTSU History Professor Carroll Van West when he visited Beth Salem is that he was very excited about the outhouses.

“I do find privies to be important,” said West, who is also the Tennessee state historian. “So she is not the first person to laugh at me about it.”

As the longtime director of MTSU’s Center for Historic Preservation (CHP), West visits important but often overlooked historic sites across Tennessee and the United States—documenting what’s left to

preserve and then developing a preservation plan, usually for free.

When Boyd contacted West, he’d just written a book, Tennessee’s New Deal Landscape, about President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s public works projects in the Volunteer State. One project was the installation of tens of thousands of modern outhouses—around 3,700 in Cleveland alone, he said. The project didn’t just give rural people meaningful employment; it also improved public health.

“THOSE DIFFERENT BUILDINGS, PLAIN AS THEY ARE, WITH THE SETTING AND THE CEMETERY, REALLY DEFINE . . . A COMMUNITY AND PLACE. ˮ

Most New Deal privies are long gone. Discovering two of them behind Beth Salem Church was a rare treat.

But what really captivated West as a historian was the wholeness of the scene he saw. Church, kitchen, privies, graveyard.

“Those different buildings, plain as they are, with the setting and the cemetery, really define a community and a community place,” he said. “Those are really invaluable locations throughout our country, where you can see that here’s a place people gather and share.”

Preserving the sense of place has always been the focus of the CHP—preserving its elements, however humble, so the place can tell the stories when the people no longer can.

Beth Salem tells the unique story of an integrated Southern community that was at its most vibrant during the most volatile era in the American South, save the Civil War itself. Reconstruction and Jim Crow were uniquely dangerous times for Black people in Tennessee, home of the Klan.

“When you look at Beth Salem, it’s the place that really captures your eye,” West said. “It’s off on a secondary road; it would have been a bit hard to find. But that was probably smart for the Black families back during the Jim Crow period, to be out of sight. You know—out of sight, out of mind.”

Oddly enough, that was a little easier for Black people to do in very white, rural east Tennessee.

“The number of African Americans was never, in so much of that region, very large; therefore, they were never perceived as a particular threat,” West said. “That’s very different than in other parts of the state.”

As far as Dickey knows, her family was not affected by racial turmoil. In fact, some of the people who helped her mom after her dad died were white.

“We were safe,” she said. “They were good, nice people. Really, when segregation and all that came up, it didn’t affect us because we were used to them. We were neighbors.”

One thing everyone knows for sure is that Beth Salem was special.

West got the church nominated for the National Register of Historic Places in 1999, in time for Boyd’s mom to see it.

“Thank God she saw that before she passed away,” Boyd said. “That was a wonderful day, to see that letter.”

The National Register preserves the history of the place. Whoever owns the place has to preserve what’s on it. Boyd wasn’t sure who owned the church, but as more years went by and the floor and ceiling started sagging, she decided she had to save it.

That’s the latest unwritten chapter of the Beth Salem story.

What Boyd remembers next about working with West is how thorough he was: measuring, photographing, documenting things in need of repair, crawling under the church’s sagging foundation. And that was just for the Historic Register nomination.

In 2017, at Boyd’s request, West developed a preservation plan. Since then, she’s raised some

Boyd is working on funding to help preserve the church.

ONE

funds and gotten some important work done. The church has new paint inside and new whitewash outside. There are new pews to match the old ones, and new glass in the old windows. Fixing all the sagging things will be the bulk of the expense. Boyd figures it will take at least $70,000 to do that. She’s working on a grant.

In 2022, Boyd discovered who owns Beth Salem. Its last living trustee signed the deed over to the Hiwassee Presbytery of the Cumberland Presbyterian Church. They didn’t know they owned it either, but when Boyd told them, they were glad to hear it. She was relieved to learn that Beth Salem is in bigger hands than hers. Because it isn’t just a building.

“One thing Beth Salem gives us is community artifacts,” she said. “That church is an artifact. That cemetery is an artifact.” They’re artifacts of a history that goes as far back as memories go.

MTSU’s Center for Historic Preservation works with communities to interpret and promote their historic assets through education, research, and preservation. In doing so, the CHP enhances citizens’ sense of place, pride, and identity.

• Focuses on heritage area development, rural preservation , heritage education , and heritage tourism

• Works within state , regional , and national partnerships

• Programs include Tennessee Century Farms , the Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area, and Teaching with Primary Sources—MTSU

HOW TO GIVE

Enter Center for Historic Preservation in the Other box at mtsu.edu/give

Larry Sanderson at his wild ginseng farm in South Pittsburg

Larry Sanderson at his wild ginseng farm in South Pittsburg

The Appalachian ginseng belt spans thousands of wooded miles from Maine to Alabama, which means that Larry Sanderson’s small ginseng farm on the Cumberland Plateau is pretty near the tail end.

Ginseng loves the beautiful, borderline inhospitable landscape. So does Sanderson, for different reasons.

American ginseng grows best in an eastern hardwood forest. It thrives in the dappled light and temperate climate. It gains strength from the roots and rocks it fights for purchase in the soil.

AGRICULTURE and AGRIBUSINESS

Article by Allison GormanSince American ginseng root has become an increasingly valuable commodity in Asian markets, Midwestern farmers have started growing it in open fields under artificial canopies. Wisconsin is now the top exporter of ginseng.

Tennessee, where it grows wild, is a distant third. But ginseng seems to know the difference between fields and forests. Buyers certainly do.

Field-cultivated ginseng is less valuable than wild-harvested because its roots are considered less potent in Chinese medicine, said Professor Iris Gao, director of the International Ginseng Institute (IGI) at MTSU. Her research has lent credence to that theory. In one of the few published studies comparing the potency, her team at the IGI found that wild ginseng contained far more active ingredients than fieldcultivated roots.

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Southern Research Station reported that a dry pound of wild American ginseng was selling for hundreds of dollars, which was 10 to 25 times more than field grown.

The high selling price is a big part of the lure for Appalachian ginseng growers, who cultivate the plant in its natural habitat in the woods.

Another part is knowing you can make a living doing a thing if you work hard enough, because that thing is mostly in your hands.

After losing a lucrative living and his 401(k) with Enron (the energy-trading and utility company that famously went south in 2001), Sanderson decided not to depend on someone else to secure his future.

THE HIGH SELLING PRICE IS A . . . LURE FOR APPALACHIAN GINSENG GROWERS, WHO CULTIVATE THE PLANT IN ITS NATURAL HABITAT.

He’d spent his whole life raising things. As a kid in Montana, he raised vegetables and ducks and rabbits. Even when he was a power-plant operator and making good money, he raised worms in his basement and sold them to fishermen. He trusted himself and he trusted nature. He figured if they worked well together, he could make a career out of ginseng.

In 2017, Sanderson and his wife bought 10.5 forested acres between Monteagle and South Pittsburg. They loved their little slice of mountaintop. They loved the fact that it was so quiet and that if they disturbed the quiet there was nobody around to care.

“We can yell or shoot our guns or whatever we want to do out here,” he said.

It’s hard to imagine Sanderson doing either of those things; he’s a chill guy. Maybe more so since he broke free of the corporate grind. If he has yelled a little, though, he’s had reasons. Nature can be an unreliable partner too. He’d barely gotten started growing when he was diagnosed with a hereditary heart condition that made the hands-on work of

farming challenging. And then there was ginseng’s famously challenging nature.

Fortunately, ginseng is tenacious, like most of Appalachia, and Sanderson is too. He may be trying to make a living in the middle of nowhere, but it helps to know he’s not going it alone. He’s got a partner in Gao and MTSU.

What Sanderson is doing is known as wild-simulated farming. The concept’s not new, but it’s new to ginseng, Gao said. With financial backing from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), she’s been working closely with Sanderson and the budding regional community of ginseng growers to advance the wild-simulated method. They’re breathing new life into an old way for mountain folks to make a living.

Since the 18th century, Tennesseans have put food on the table by digging for ginseng, heading deep into the woods every fall. The work is hard and dangerous and usually doesn’t provide a stable income, especially now that ginseng is getting harder to find.

American wild ginseng has been an endangered species since 1974. Digging on public land has serious legal consequences. Digging on private land—if it’s not your own, that is—can have consequences of its own.

Time for a new business model. One without the Appalachian occupational hazards.

Sanderson was figuring that model out as he went along when he sowed his first 100,000 seeds. He learned from the internet that ginseng don’t like pine needles. He learned from an estimate from a local tree-removal service that he wasn’t going to pay someone to take down those big pines that dropped needles in the area he wanted to plant. He raked the needles back himself.

All but 500 seedlings from that first crop died away. Along the way, he learned something else that was new: Ginseng don’t like ferns either.

SANDERSON HAD PLENTY TO KEEP HIM OCCUPIED UNTIL GAO’S RESEARCH BORE FRUIT.

And so it could have gone for Sanderson, learning one or two devastating lessons at a time, year after year. They might not have been quite so devastating if ginseng were an annual crop. But sowing ginseng is a long-term proposition—more like planting an orchard than a row of corn. Those field farmers in Wisconsin can reap what they sow in four years. Appalachian wild farmers have to wait seven. Luckily, Sanderson found out about Gao.

She didn’t know all there was to know about ginseng either—but like him, she was dedicated to knowing more. So was the USDA, which saw the economic potential of ginseng and the economic need of the region where it grows wild. It invested $148,000 in Gao’s vision of advancing the new model for farming ginseng.

As Sanderson was struggling to raise his first crop, Gao was getting IGI off the ground.

The MTSU institute opened in May 2018. In the nearly six years since, Gao and her team have spent part of their time in the lab, investigating ginseng’s healing properties and working to develop more resilient hybrids, organic fungicides, and other natural ways to combat whatever can kill a valuable crop. They’ve spent the rest of their time talking to growers like Sanderson, wherever they are—at their farms in the woods, at regional meetings, or at the workshops and symposiums the IGI hosts.

In stark contrast to ginseng digging—which is by nature a secretive, territorial, and finite business— wild ginseng farming has flourished in Appalachia through collaboration. Granted, it’s a loose collaboration. Growers and distributors tend to be fiercely independent, which is likely what attracted them to the landscape and the lifestyle in the first place. But they collectively benefit by sharing information and solving problems together, with the help of Gao.

“She’s working towards the good of everybody,” Sanderson said. “I think the world of her and what she’s doing. With her helping out the other growers, everything I’m doing is helping them, and she’s the common thread.”

Gao said she can’t speak for other agricultural communities—the corn farmers or cattle ranchers, for example—but the spirit of camaraderie among the region’s ginseng farmers is strong. Maybe that’s because it’s a fledgling community where everyone seems to know each other. Maybe it’s because they share the same struggles. They’re all small farmers. They’re all growing a uniquely challenging crop.

“Whoever grows ginseng knows how much time and effort it takes,” Gao said. “It takes investment. And courage.”

If you’re in your 50s and you’ve just lost your career and your savings, it takes courage to pick yourself up and try something new. But that’s what Sanderson did after Enron scandalously went bellyup, robbing him of what he’d thought would be a comfortable retirement.

Throw in a far scarier, equally unexpected challenge—a menacing blood clot in his heart—and it’s hard to see how Sanderson was still eager to move to an economically challenged region and learn to grow a challenging plant. But he was.

Doctors were able to dissolve the clot, and he kept planting and learning. In 2018, he sowed his second crop. Thousands of those plants survived. In 2021, he got his first three-prong, the distinctive leaf pattern of the maturing ginseng. You can harvest at four or five prongs. If he kept working hard and nature cooperated, Sanderson figured he’d get his first harvest in 2026.

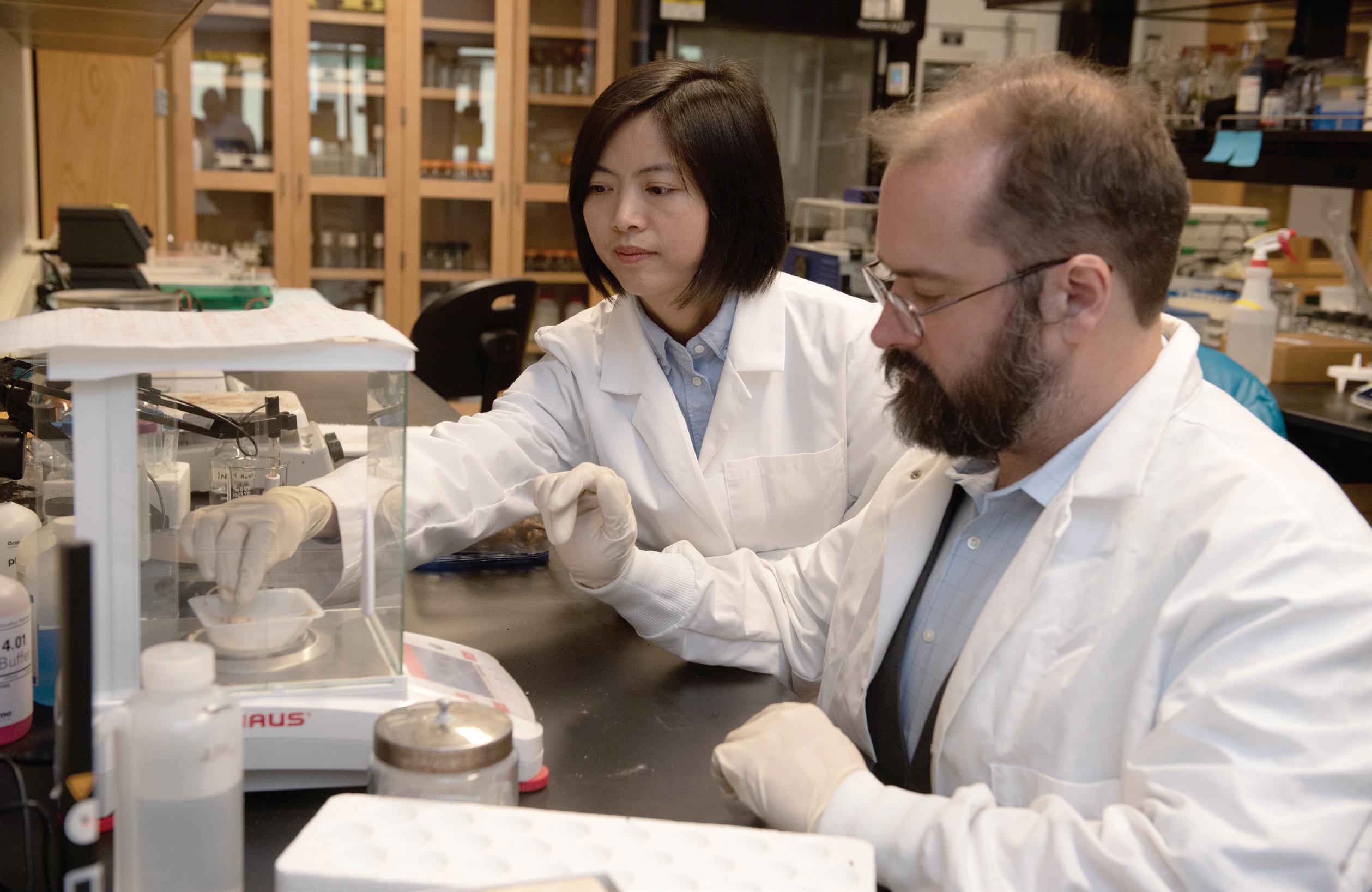

MTSU's Iris Gao (l) and Molecular Biosciences Ph.D. alumnus Shannon Smith

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is a big believer in ginseng and a big believer in MTSU Professor Iris Gao. A USDA grant of $148,000 got the International Ginseng Institute (IGI) at MTSU off the ground, and a second grant of $455,000— combined with $300,000 from MTSU—is funding the development of biocontrol agents to prevent blight.

Along with principal investigators from Penn State and the University of Virginia, Gao is leading a multinational research team. It’s a big project to address a big problem.

“The major diseases in ginseng are soil-borne fungal diseases,” Gao said. “They can spread quickly, wiping out a crop in a very short time. That’s the No. 1 issue with [ginseng farming]. It takes time, seven to 10 years. Imagine getting a fungal disease in your fifth or sixth year that wipes out all your plants. It would be a disaster.”

The easiest way to handle blight—spraying crops regularly with synthetic chemicals—is enormously expensive. It also makes the ginseng less desirable on the Asian market, where it’s used in foods, personal care products, and Chinese medicine.

The IGI is researching the use of goldenseal, a “companion plant” to ginseng, that grows in the

same habitat and has antifungal properties, Gao said. “We have some good results from that,” she said.

Late last year, they submitted a manuscript of the study for publication. Along with a team of collaborators at Tennessee State University, they also published the first reports of three new pathogens that infect American ginseng. Once they confirmed pathogenicity, Gao said, she and the team began working on developing new, sustainable methods of killing the blight that kills ginseng. The botanical extracts showed “wonderful control in vitro.” The next step was to start testing on live plants.

When the results come in, the IGI will share them with regional growers like Larry Sanderson through newsletters, workshops, and symposiums. Those in-person meetings are also a chance for growers to learn from each other, and for Gao to synthesize the information for collective use.

“That way she can help new people coming in,” Sanderson said. “If they ask where they should go, she can say, ‘Here’s what the technology is showing us, this is all the information that we have, so you can decide what you want to accomplish.’ What she’s doing is just phenomenal.”

When he talked to other people about the three-prong, he would gush like a new grandpa. “It has a little flower on it. It’s just as cute as it can be.”

His enthusiasm was only slightly tempered by a new challenge: “My heart went south on me again.”

It had been headed south for a while. In 2020, the previous year, his son had to help him plant his crop. In 2021, instead of planting, Sanderson had heart surgery and then spent the rest of the year in limbo, waiting to learn if he’d need a second surgery. Even if he’d had the energy to plant, he wasn’t sure it would have made sense.

All this time, Gao stayed in regular contact with Sanderson. She told him she’d been looking into another medicinal herb, goldenseal. It wasn’t as valuable as ginseng, but it was fetching a good price on the Asian market, and you could harvest it sooner.

Sanderson is patient and tenacious, as any ginseng grower should be. Still, it probably helped to learn that he didn’t need a second surgery. He felt his energy slowly coming back.

He didn’t plant in 2022. He did become a new grandpa and was tickled to death.

In 2023, he felt well enough to drive to California to see the baby. It would be his first vacation in seven years. Before he and his wife left the mountain, he walked five pounds of seed into the ground, with plans to sow another five when he got home. He was anxious to catch up on all the stuff he couldn’t do when he was sick.

“Now that my health is doing better and I know that I’m not going to die, I need to start actively working this little plot and getting these plants ready for harvest,” he said.

There were lots of things to do. Then again, lots of good things had been happening.

Gao had connected Sanderson with the United Plant Savers, in Ohio, who certified him as a woods-grown ginseng farmer, a governmentrecognized designation.

He’d connected Gao with his sister’s boss, who had an organic antifungal oil that he thought might remove ginseng blight. Organic ginseng fetches a higher price than ginseng sprayed with fungicides or pesticides. Most growers, including Sanderson, have to apply expensive chemicals regularly to keep their crops alive.

If this oil did what Sanderson thought it might, he’d be ready to move on to certified woods-grown organic.

“This is going to blow certified organics wide open,” he said. “I can kill any blight and still be considered organic.”

Gao had agreed to do some testing, although getting definitive results could take time. A lot of herbs are reported to have antifungal properties, she said. She’d start with an initial screening to see if this antifungal, intended for human use, warranted further research.

WHOEVER GROWS GINSENG KNOWS HOW MUCH TIME AND EFFORT IT TAKES.

“It’s worth testing if it works on this certain pathogen,” she said. “It may or may not work, because antifungal pathogens are very specific. Something that works for one does not necessarily work for another.”

Sanderson had plenty to keep him occupied until Gao’s research bore fruit.

From a connection at United Plant Savers, he’d learned how to go from three to four prongs faster. (His oldest plants still had three.) Turned out he just needed to thin his tree canopy, from 90% coverage to 75% or 80%.

He was working out the logistics. He still wasn’t going to pay someone to take down those pines.

“I don’t have a way to snake ’em out of there,” he said. “And I don’t want to just drop them and leave them, because that’s going to cause issues later on.”

When the four-prongs finally came, which meant the roots were finally big enough, he’d harvest them. And then, he said, he’d probably put them in dry barrels and wait.

The market price had gone down since he first planted them. Sanderson seemed unaffected. He’s not going anywhere.

MTSU’s International Ginseng Institute is dedicated to the research, education, and outreach of an Appalachian-grown medicinal herb, wild American ginseng.

• Focuses scientific research to develop strategies, standards, and sustainable products to benefit the community and world

• Studies and addresses issues affecting American ginseng conservation and industry development

• Promotes wild-simulated ginseng cultivation and sustainable rural income

Faculty from Molecular Biosciences

Ph.D. , Plant and Soil Science , and Chemistry programs participate in the IGI and offer opportunities for budding researchers.

Fermentation Science alum Shelby Ziegler at Tennessee Distillery in Columbia

Fermentation Science alum Shelby Ziegler at Tennessee Distillery in Columbia

The Tennessee Whiskey Trail stretches from Memphis to Bristol, with 39 tasting rooms along the way. Each distillery has its own spirits and story to share.

At any given stop, you might learn how a fabled whiskey survived Tennessee’s long prohibition, or how the state’s lush landscape provides the spring water or heirloom grain that makes what you’re sipping extra special.

When you stop by Nashville Craft Distillery, you’ll learn about some of those things. You’ll also learn about chemistry, biology, and physics.

The distillers there give the tours, and head distiller Bruce Boeko likes visitors to know the science behind the process.

Before he founded Nashville Craft in 2016, Boeko worked as a scientist. He spent 20 years in a Nashville lab, doing forensic analysis. When the job became less hands-on and more bureaucratic, he started rethinking his career. When his company asked him to leave Tennessee, he opted to stay and go back to school to study business. A few years later he had a new degree and a business plan.

At that point, whiskey making was both a historic identity and an emerging industry in Tennessee. Just a few years earlier, in 2009, state lawmakers began allowing alcohol production in most counties—not just in the three counties with major distilleries. The changes broadened the scope of the industry to include both custom bottlers for spirits companies, and craft distilleries that make and sell their own product on site.

That traditional model of distilling was what Boeko was envisioning. As a scientist, he said, he was naturally intrigued by the process, although technically you don’t have to understand the process to follow it.

“Whiskey’s been made for a thousand years,” he said. “Microbiology is much more recent; the microscope was invented something like 400 years ago.”

After he opened the distillery and it came time to hire, it made sense to turn to MTSU. He’d regularly trusted the University as a source for new scientists when he was hiring for the forensics lab. His second employee at Nashville Craft was a Blue Raider he had hired right out of college. They’d worked in the lab together for 10 years.

A year after Nashville Craft opened, MTSU launched a Fermentation Science program with bachelor’s and master’s tracks. It was the first degree program of its kind in Tennessee and one of just a few in the United States.

“I haven’t spent a lot of time at MTSU, but I’m certainly familiar with the students and the programs,” Boeko said. “Once we found out that

the Fermentation Science program was opening, we were interested.”

He might have seen himself in the program; he certainly saw future employees. It was exactly the course of study you might enjoy if you love chemistry and biology and physics and hands-on work (and whiskey).

Since MTSU launched Fermentation Science in 2017, Boeko has hired two people from the program. The first came in as an intern and was offered a job upon graduation. The second—“kind of a weekend distiller/apprentice/distiller guide,” Boeko said—is working on his master’s degree. Boeko said he can train new distillers more quickly when he doesn’t have to tell them what saccharomyces cerevisiae (brewer’s yeast) is or explain the differences between a polysaccharide versus an

oligosaccharide versus a mono- or disaccharide (take the tour).

“They come in with a certain basic understanding already,” he said, “and then it’s more about teaching them our specific process and how to present the information to the public.”

It’s also helpful to have the scientific perspective of distillers whose knowledge isn’t specific to whiskey, he said, and Fermentation Science majors don’t just learn about brewing and distilling. You start thinking about fermentation a little differently when you talk to someone who also knows how to make kombucha.

Shelby Ziegler, among the first cohort of Fermentation Science majors, said her favorite part of the program was the hands-on aspect. In one class they made cheese and sausages. For another they tended a vineyard with Professor Tony Johnston, the program director, then later harvested and crushed the grapes to make wine.

But with the popularity of brewing and distilling in Tennessee, those are the most obvious landing places for a Fermentation Science graduate. That’s where Ziegler landed too, even though she faced an otherwise challenging job market upon her December 2020 graduation.

She lived just north of Nashville, a short drive from any number of microbreweries; normally they’d be humming. But all the taprooms were closed during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“They’d gone to making hand sanitizer instead,” she said.

Still, they were hiring. Ziegler ended up turning down offers from microbreweries close to home to take an “enticing” job with a distillery 70 minutes away.

Tennessee Distilling Co is a larger-scale production facility in Columbia that bottles some of the biggest whiskey labels in the world. With another campus in Centerville, the distiller also supports Tennessee

IN 2009, STATE LAWMAKERS BEGAN ALLOWING ALCOHOL PRODUCTION IN MOST COUNTIES—NOT JUST IN THE THREE COUNTIES WITH MAJOR DISTILLERIES.

farming, with the vast majority of grains purchased from within 100 miles of the Columbia facility, including thousands and thousands of pounds of corn every year and some local rye. (Malt and barley usually is grown elsewhere.)

Ziegler said it took her some time to learn all the equipment—that’s unique to each distillery and therefore can’t be taught in class. But thanks to her academic training she walked into the job as a whiskey distiller knowing how to monitor and troubleshoot the organic process.

IT’S ALSO HELPFUL TO HAVE THE SCIENTIFIC PERSPECTIVE OF DISTILLERS WHOSE KNOWLEDGE ISN’T SPECIFIC

“I knew what the different pH means, the sugar content, what a healthy fermentation should look like, what could be off-flavors produced from whiskey, and what bacteria could produce those off-flavors,” she said. “So I learned about how to solve problems with the mash or the distillate, and I knew how to track the process to see if it was fermenting correctly.”

Ziegler is one of several MTSU Fermentation Science majors Mike Williams has hired since he and his business partner launched Tennessee Distilling eight years ago. As master distiller, Williams said, he values the skillset Johnston’s students bring because so many things can go wrong during fermentation.

“You know, you don’t inherently need a degree to run a still,” he said, “but his folks understand the problems in our mash making. They don’t just know what they’re doing; they know why they’re doing everything. So they tend to move up in the company to roles with more responsibility after starting as a brewer-distiller.”

It should be noted that Williams is also a Blue Raider—former cheerleader and student government president, class of 1981 (Economics). His wife, Nancy Sloan Williams, served as editor of the University’s student newspaper, Sidelines . The press box at MTSU’s Floyd Stadium is named for her grandfather.

So it’s natural that Williams would be quick to hire from MTSU. But his professional investment in the Fermentation Science program speaks volumes. He’s so impressed with its graduates that he’s begun reimbursing his distillers who get the master’s degree.

That’s how Ziegler ended up back in school. She’d been employed at Tennessee Distilling about a year when she began mulling the idea of getting her master’s degree. She wanted to expand her knowledge, but not her student debt. An offer from Williams sealed the deal.

“That’s what got me to apply to grad school,” she said. “I didn’t want to take out a big loan to get my master’s, but Tennessee Distilling Group paid for it, and they’ve been super.”

The distillery runs 24/7, so she could attend class in the morning and work the evening shift.

For Williams, investing in his employees’ advanced education is a way to build institutional knowledge quickly and stay on top of his company’s success.

“We’ve grown fairly rapidly,” he said. “Fast growth is a good problem, but it’s still a problem. I’ve felt like I’ve been riding a bull all this time.”

The Fermentation Science program has grown quickly too. From its initial cohort of 17 undergraduates in 2017, it’s now holding steady with 35 undergraduate students, plus 12 to 18 students in the two-year master’s program.

In January 1920, the United States banned the manufacture, transportation, and sale of alcohol from coast to coast. The U.S. didn’t lift the ban for 13 years.

Tennessee shrugged and said, Hold my beer (or something like that). Its prohibition lasted twice as long, predating federal prohibition by 10 years and postdating it by four.

The decision to ban alcohol production was momentous in a state where distilling had a long history and was an important business sector. In 1810, according to the Tennessee Distillers Guild, Tennessee had “hundreds of distilleries, with 30 in Chattanooga alone.”

By 1866 distilling was Tennessee’s largest manufacturing industry, and Chattanooga was a North American distilling hub. But with the state’s 1909 prohibition, all that business came to a stop. Legal business, that is. A banner headline in the Sept. 3, 1915, Hamilton County Herald announced charges against Chattanooga’s police commissioner and a local distiller, who’d been caught smuggling whiskey out of state in coffins.

Two of Tennessee’s legendary whiskey brands left the state too. Jack Daniel’s fled Lynchburg for St. Louis. George Dickel uprooted from Cascade Hollow and moved to Louisville.

Both eventually were welcomed home after Tennessee’s prohibition lifted. But the state’s accommodation to the larger industry was grudging.

Distilling was legal in just three counties—Moore (Jack Daniel’s), Coffee (George Dickel), and Lincoln (Prichard’s Distillery, founded in 1997)—until 2009. That’s when the Tennessee General Assembly passed laws increasing the number of counties to 44, and then 75. The “Whiskey Bill” that allowed distilling in Hamilton County, with the approval of its county commission, wasn’t signed into law until 2013. Finally, Chattanooga Whiskey could be made in Chattanooga, not in Lawrenceburg, Indiana.

“There’s a love-hate relationship with alcohol in Tennessee,” remarked Bruce Boeko, who founded Nashville Craft Distillery in 2016. “A lot of that is religious, and somewhat it’s a rural-urban divide.”

Then again, he noted, urban distillers support rural agriculture. “There are things that bring folks together,” he said.

If a shot of whiskey won’t do it, maybe shared fortune will.

“It’s a revolving door, but we’ve got substantial interest,” Johnston said.

Fermentation Science majors don’t just come from Tennessee, he noted. They’ve come from Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, Ohio, Georgia, and South Carolina.

Ziegler, an Alabama native, said she was originally attracted to the bachelor’s degree because it’s on the Academic Common Market, which lets college students in the southern U.S. pay in-state tuition for degrees not offered in their home states.

SCIENCE HAS ALSO EARNED THE CONFIDENCE OF TENNESSEE DISTILLERS AS A RESOURCE FOR TROUBLESHOOTING.

The master’s degree has drawn even more widespread interest, Johnston said; a quarter of the graduate students are international. In general, he’s been surprised by the diversity of their academic backgrounds.

“My initial expectation was that the majority of the students in our graduate program would be our undergraduates that just stay on, and that has completely not been the case,” he said. “We have a few that do change their career pathway. I’ve had psychology majors, graphic design, biology and microbiology, engineering. . . . I don’t want to say random, but not the pathways I expected people to follow.”

Zieger has carved her own path.

After completing two semesters of graduate-level Fermentation Science coursework, she switched to Biotechnology to get broader training in food science protocols and experiments—knowledge she can apply in the lab side of the distillery. She even moved up in the company from whiskey distiller to quality assurance manager before finishing her master’s in December 2023.

While some Fermentation Science graduates stay in Tennessee, like Ziegler has, others have landed all over the map, Johnston said.

“What impresses me equally is that they’ve gone to take positions in Wyoming, Oregon, Texas, Kentucky, and North Carolina, as well as Tennessee,” he said. “We’re getting students from around the country, and they’re taking jobs around the country.”

Given the growth of the program and the success of its graduates, it was only a matter of time before other universities sat up and took notice. Last fall the first Fermentation Science faculty member Johnston hired went to Texas A&M University to start a program there.

“The way I look at it, they came to the best program to get a really great young man to run their program,” Johnston said. “To me, the fact that a tier-one, high-intensity research institution came and got my secondhand man, that’s a pretty large statement of confidence in our program.”

Five years in, Fermentation Science has also earned the confidence of Tennessee distillers as a resource for troubleshooting. One custom bottler turned to Johnston for help identifying the source of a gauzy film that kept appearing in a certain product.

Johnston and his lab manager isolated the precipitant and ran an analysis that confirmed their suspicion:

“What we were able to go back and explain was that when you make a distilled spirit out of this particular grain, if you don’t decide to collect at the right time when you distill, you can bring in a component that causes this film.”

In other words, the problem was with the product the bottling company received, not with their process.

That was enough for the company rep. She waived further analysis, and Johnston waived the fee. Just make a donation to the program, he told her— whatever you think our work was worth. And she did.

“I was happy, and she was happy,” he said.

Mike Williams, master distiller at Tennessee Distilling Co.

Mike Williams, master distiller at Tennessee Distilling Co.

In Tennessee, Fermentation Science has also established itself as an important part of the craft distilling ecosystem—which, as Boeko describes it, looks like a smaller, younger iteration of craft brewing.

“It’s a very small, concentrated industry of big players, mostly,” he said. “And now, like in the craft beer world, there are lots and lots and lots of small players. We still don’t make up as significant a percentage of market share in the distilling world as craft beer does in the beer world, but I think we’re moving in that direction.”

According to industry research company IBISWorld, the number of U.S. distilleries grew by an average of 9.6% a year between 2017 and 2022, when there were 2,047. There are 30 distilleries in Tennessee, some with multiple locations.

The distilling scene in Tennessee has changed dramatically in the 14 years since the state loosened its laws, Boeko said. The growth of the sector is reflected in the evolution of the Tennessee Distillers Guild. Founded in 2014 with 13 members, it created the Tennessee Whiskey Trail and has become “a very strong, capable” organization, he said.

“We work in contact with the Fermentation Science program at MTSU. We’re in contact with the UT ag extension people. We’re in contact with the Department of Agriculture. . . . And we get together, most of the distilleries, at least four times a year,” he said.

As he spoke, Boeko was preparing for the guild’s final event of 2023, the Grains & Grits Festival in Townsend. Some 1,300 guests would be gathering against the backdrop of the Great Smoky Mountains to enjoy “gourmet grub” and sample whiskey, rum, gin, vodka, and even moonshine from the state’s three great divisions. Sounds like a fitting celebration of the past and the future of Tennessee.

MTSU’s Fermentation Science program, the first of its type in Tennessee, teaches the science and art of fermentation in all applications, from food and beverages to medication and industrial chemicals.

• Develops practical research and outreach initiatives to assist the growing fermentation-related industries in the state and world

• Conducts courses in partnership with local companies

• Provides internships with wineries , distilleries , breweries , cheesemakers , and government agencies

Support the program by purchasing lab analyses from MTSU’s Fermentation Science Analytical Laboratory.

The Tennessee Department of Education recently brought on Tiffany Wilson, coordinator of MTSU’s School Counseling program, as a consultant for a $14 million federal grant project to retain and recruit mental health professionals into high-needs, rural school districts. MTSU was also identified as one of three Tennessee universities that can help with recruitment and retention for Project RAISE (Rural Access to Interventions in School Environments), which will recruit future school counselors, psychologists, and social workers to serve as paid interns to increase the number of mental health personnel in 40 underserved Tennessee school districts.

MTSU’s School of Agriculture developed the Tennessee Digital Agriculture Center—the first of its kind in the state—after landing a three-year, nearly $750,000 grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture. The center features a series of student/non-formal educator projects and community outreach events to forge a strong digital agriculture/ data science education program focused on youth across Tennessee. In summer 2023, 16 high school students attended MTSU’s second Digital Agriculture Camp, building and flying their own drones and learning about data science and precision agriculture.

The first four participants in MTSU’s Medical School Early Acceptance Program— Pierce Creighton, Claire Ritter, Maria Hite, and Kirolos Michael—are finishing their second year at Meharry Medical College. The special partnership is designed to increase the number of primary care physicians serving medically underserved populations and help alleviate health care disparities in rural Tennessee. Adding a new cohort of up to 10 incoming freshmen annually, the state-funded program allows accepted students to attend MTSU tuition free for three years and pay medical school tuition for only two of four years.

Whether it’s business, education, nursing, or many other high-quality options, find your future at MTSU.

• Connect with innovative faculty and peers.

• Retool and create your next opportunity.

• Advance with affordable and convenient options.

• Succeed in one of the nation’s hottest economies.

Engage in real-life research, scholarship, and service with expert faculty, including through partner centers and institutes on campus.