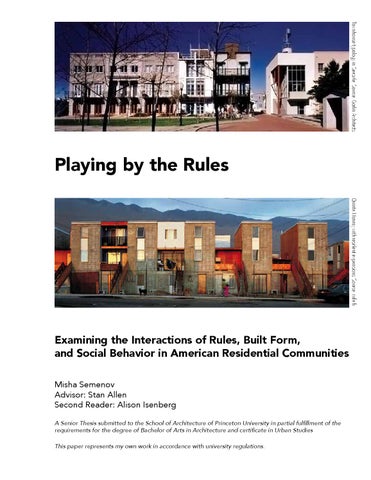

Townhouse typology in Seaside. Source: Gorlin Architects

Playing by the Rules Quinta Monroy with resident expansions. Source: mfa.fi

Examining the Interactions of Rules, Built Form, and Social Behavior in American Residential Communities Misha Semenov Advisor: Stan Allen Second Reader: Alison Isenberg A Senior Thesis submitted to the School of Architecture of Princeton University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Architecture and certificate in Urban Studies This paper represents my own work in accordance with university regulations.