The New Doctor’s Worklist: Optimizing Patient Safety and Ward Round Efficiency

Liang Zhi Wong, Zoe Hinchcliffe, William Kenworthy, Anthony Wolff, Indraneel Sengupta BarnetHospital,TheRoyalFreeLondonNHSFoundationTrust,London,UnitedKingdom

Liang Zhi Wong, Zoe Hinchcliffe, William Kenworthy, Anthony Wolff, Indraneel Sengupta BarnetHospital,TheRoyalFreeLondonNHSFoundationTrust,London,UnitedKingdom

Introduction

There have been safety concerns regarding the doctor’s list management system within our General Surgery Department Patients were regularly not seen on ward rounds for up to hours or days as they were not coded ‘to be seen’ into the system upon acceptance of referral, meaning that they did not appear on ward round lists The inflexibility of this system also meant that lists were very inconvenient to print, leading to delays in ward rounds and reduced time for urgent patient jobs Doctors even had to skip handovers in order to print lists

Aims

This project aims to improve and simplify list processes, enabling:

1. Easier ward round preparation

2. Reduction in patients missed

3. Potential to be customized to needs of the team

Methods

3 key aspects were identified: ‘Compliance (Of doctors)’ , ‘Safety’ andEfficiency’. 2 Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were conducted based on these aspects, with a third cycle currently in progress

Intervention

A new list system, the ‘General Surgery Care Teams’ was introduced on Cerner to the entire department. Education sessions and materials were prepared to facilitate uptake With this new system, patients need not be coded to appear on lists, and printing is more convenient

Data Collection

Compliance: Doctor adherence to list guidelines

Safety: Number of patients missed in a 2-week window

Efficiency: Time taken to print lists

Across allaspects: Survey & Verbal feedback from doctor

PDSA Cycles

We quantified the ‘Compliance’, ‘Efficiency’ & ‘Safety’ parameters to be used as a baseline for the new list

We collected data on the old list based on ‘Compliance’, ‘Efficiency’ & ‘Safety’

The old list had poor doctor compliance, with 24 4% of patients not coded This made it unsafe, with 6 patients missed and 4 adverse outcomes (AKI, missed medications etc.) in a 2-week period.

The ‘General Surgery Care Teams’ was introduced on 29/11 – completely replacing the old list system Formal education sessions and informal demonstrations were held Instructional videos and FAQs were disseminated

We re-surveyed results after Care Teams implementation, with the aim to identify correctable flaws in the new system

We re-collected data on ‘Compliance’, ‘Efficiency’ & ‘Safety’ on the new Care Teams list system 3 months after implementation

Care Teams was superior in all 3 aspects compared to the old list Doctors voiced concerns about patients being missed when being transferred between lists & lists not indicating patient diagnosis

Customization of Care Teams: Include a new section to ensure doctors know where to move patients + reintroduce coding of patient diagnosis

Results

Compliance: Doctors compliance achieved! – patient info keyed into system increased from 11-95% in 2 weeks

Average weekly compliance was ∼90% over 2 consecutive months (Compared to 75 6% for the oldlist).

Safety: Patients missed in a 2-week period fell by 33% - adverse outcomes fell by 100% System was perceived to be safer compared to old list Patients were still being missed as they were dropping off the system while being moved from one list (On-call, Post Take or Wardlists) to another, or moved to an incorrect list

Efficiency: Care Teams lists took 14 mins less to print than the old list. System was perceived to be more efficient compared to old list Lack of patient diagnosis coding meant lists were not displaying diagnosis, leading to ambiguity

Next Steps

Although the new doctor’s worklist is superior to the old list, it has room for improvement, especially in minimizing patients missed while transferring between lists. A third PDSA cycle is currently underway, trailing the new customizations to Care Teams to improve and clarify patient flow and further optimize ward round efficiency

Oncology Ward Round Sheet

Dr. Justin Tetlow and Dr. Nathalie Webber

Dr. Justin Tetlow and Dr. Nathalie Webber

A tool for oncology ward rounds that improves compliance with domains set by local clinical governance and Good Medical Practice whilst not increasing time spent documenting.

PREVIOUS WARD ROUND SHEET:

Data was collected on whether documentation commented on VTE, antibiotics, resus status, fluid balance, oncological summary and mobility

This was then analyzed by grade of the most senior participant in the ward round.

THE NEW WARD ROUND SHEET:

Improved the quality of the documentation of core domains

Consistent improvement across all medical grades

Staff reported no increase in the time spent documenting

Clinical documentation facilitates the transfer of critical information between health care professionals. This information can also prove invaluable when improving services, reviewing adverse clinical incidents and auditing. Following a critical incident, we recognized that standard ward round information was not being consistently documented. If the correct information is not diligently collected, it hinders what can be learned from medical notes. This can both directly affect patient care by allowing salient information to be missed in the immediate sense; and indirectly by the loss useful data that could identify ways of improving patient care. 1 2 3 4

Nursing Staff report that clinical information is more accessible, and communication improvedDr.Hassan Mallick, ST4 Psychiatry. hassan.mallick@nhs.net | Dr.Isaac Obeng, QI Coach. isaac.obeng1@nhs.net

Transitioning into a community mental health team (CMHT) can be challenging for new trainees (1,2). Contextual factors have a greater impact on healthcare practice than regulatory and management frameworks (3) The local learning environment is crucial to trainee performance, and peer support is a major source of trainee wellbeing , which ultimately would lead to improved patient care (4) Our project aims to improve trainee wellbeing by providing a "humanistic induction" to the CMHT using audio resources (podcasts) for flexible learning, normalising vulnerability and fostering a sense of community.

M O D E L F O R I M P R O V E M E N T

How will we know a change is an imporvement?

What are we trying to accomplish?

To increase wellbeing by 50% among trainees joining the K&C North Kensington Hub CMHT by Jan 2024

Obtain feedback from listeners using online questionnaires and analytics data from hosting platform(s)

Specific S

To increase wellbeing (reduce stress and anxiety) by 50% among trainees joining the North Kensington Hub CMHT

Life QI PDSA involvement CMHT MDT professionals willing to be recorded and have a conversation

Use a narrative based podcast to inform trainees about the CMHT structure, workflow and day-to-day challenges

S M A R T G O A L S

M A Relevant

2 Data analytics from social platforms

Content Creator Host Editor Creative Direction

Involved relevant strakeholders

Improved patient and staff care In-line with trust strategic priority of improving digital infrastructure workforce

T I M E L I N E T

Oversight Educational supervisor Communications

Upload and manage content online Provide analytics Information Governance oversight and review

Medical Education

Utilising available resources and forums

Dissemination via online "health toolbox" and in induction communications

D R I V E R D I A G R A M PDSA

an

effective podcast

R e s u l t s a n d L e a r n i n g

P o s i t i v e q u a l i t a t i v e f e e d b a c k f r o m e x p e r t s o n p o d c a s t " t h i s i s m u c h n e e d e d "

D e d i c a t e d t r u s t i n t r a n e t p a g e l a u n c h e d

5 e p i s o d e s p u b l i s h e d s u c c e s s f u l l y .

B r o a d h o r i z o n s : P o d c a s t s a p p l i c a b l e t o m u l t i p l e C M H T s , a n d p o t e n t i a l f o r r e s o u r c e f o r p a t i e n t s a n d c a r e r s

C h a l l e n g e s

T e c h n i c a l s k i l l a n d e x p e r t i s e f o r r e c o r d i n g a n d e d i t i n g i s a l i m i t i n g f a c t o r

B a s e l i n e q u a n t i t a t i v e d a t a m e a s u r e m e n t w o u l d d e p e n d o n n e w c o h o r t o f t r a i n e e s . S o m e u n s u c c e s s f u l r e c o r d i n g a t t e m p t s a n d d i f f i c u l t r e c r u i t m e n t : p r o f e s s i o n a l s r e l u c t a n t t o b e p a r t o f a “ p u b l i c ” p r o j e c t w h e r e v i e w s m a y b e m i s - c o n s t r u e d

R e c o r d m o r e e p i s o d e s : J u n i o r D o c t o r , C l o z a p i n e C l i n i c , S o c i a l W o r k e r , E m p l o y m e n t A d v i References: 1)https://www theguard an com/ healthcarenetwork/2015/aug/ 4/whathappens- un or-doctors-startwork-nhs-pat ent-care 2)https://www rcpch ac uk/s tes/ defau t/fi es/20 802/recommendat ons for safe tr a nee changeover final 0 pdf 3)https //pubmed ncb n m n h go v/21916940/ 4)https //p bmed ncbi n m n h go v/34162643/

PROCALCITONIN (PCT) IN NEONATAL ANTIMICROBICAL STEWARDSHIP: IS THIS THE WAY FORWARD?

Maryiam Zaman, Dyanne Imo-Ivoke, Ourania Pappa, Jenny Naylor, Liz McKechnie Leeds Centre for Newborn Care, Leeds Children's Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, UK

Maryiam Zaman, Dyanne Imo-Ivoke, Ourania Pappa, Jenny Naylor, Liz McKechnie Leeds Centre for Newborn Care, Leeds Children's Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, UK

BACKGROUND INTRODUCTION

Neonatal sepsis is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in newborn infants. The precise identification of neonatal sepsis still remains a diagnostic conundrum. Neonates with suspected sepsis are treated empirically with antibiotics. This however promotes the unnecessary use of antibiotics which is costly, increases antibiotic resistance, and alters the delicate neonatal gut microbiota.

Enhancing the accuracy of diagnostic tests will aid in the early identification and improve the outcomes for neonates with sepsis and will reduce the indiscriminate administration of antimicrobials in those who don’t. Biomarkers aid in the diagnosis of sepsis, with the most commonly used being C-reactive protein (CRP). CRP however lacks specificity and the response to bacteremia is slower1

Promising evidence supporting the use of procalcitonin (PCT) in neonatal sepsis has been shown to identify sepsis earlier. A PCT rise identifies more severe sepsis2 and has a good diagnostic accuracy3. Hence the addition of PCT to CRP improves antimicrobial stewardship4. Despite the evidence, PCT is not commonly used in the neonatal population.

AIMS

To evaluate the use of PCT in all babies older than 72 hours of age, who need to be screened for suspected

Late Onset Neonatal Sepsis (LONS).

METHODOLOGY

Babies with clinical signs of LONS were screened and started on antibiotics as per the neonatal unit’s protocol –PCT was added to the investigations.

PCT was requested alongside the 1st and 2nd (24h) CRP and in the same blood bottle to avoid extra blood sampling.

PDSA CYCLES

Cycle 1: We studied the root cause analyses (RCA) of Klebsiella Pneumoniae and Escherichia Coli cases over six years (20152021).

Prematurity, low birth weight (LBW), mechanical ventilation, central lines, parenteral nutrition, multiple antibiotic courses, and abdominal pathology requiring surgery were risk factors for both cohorts.

Cycle 2: The total number of antibiotic courses for suspected LOS over three months were analysed. Results were presented and the temporary introduction of PCT with 1st and 2nd CRPs was decided to review the enzyme response in LOS. Posters were created to raise awareness.

A Klebsiella Pneumoniae outbreak in our neonatal unit triggered a review of the specific risk factors for Gram Negative Blood Stream Infections (GNBSI). Amongst others, multiple courses of antimicrobials in the preterm population significantly contributed to the problem. A collaborative Quality Improvement PCT Group was initiated to review the use of PCT in reducing antibiotic exposure in neonates.

Cycle 3:

After liaising with the local microbiology department, a sevenweek audit (1/11/202218/12/2022) of 43 antibiotic courses was initiated and completed. 10 out of 43 episodes (23%) had no PCT available; either due to insufficient sample or because it was forgotten. Hence 33 cases (77%) were reviewed. PCT results were reviewed (normal value < 0.5 ng/ml).

RESULTS CONCLUSION

• Neonates who received antibiotics for LOS between OctoberDecember 2021 (46 babies and 75 courses) had ‘true’ positive blood cultures (BC) in 15% of cases (11/75). There was a significant variation on length of treatment with 37% (28/75) of total cases receiving > 36 hours of antibiotics (Fig 1), ranging between 5-14 days.

• The analysis of the PCT audit showed results on 77% of episodes (33/43). 18/33 cases had 2 CRPs < 5 and negative blood cultures. 8/18 had 2 PCTs taken and 10/18 had 1 PCT taken. All PCTs were normal (Fig 2).

• 40% of cases (6/15) had a quicker PCT than CRP response and all six babies had confirmed sepsis with positive BC results (Fig 3).

• 2 neonates with overwhelming sepsis and subsequent death had the highest PCT in the cohort.

Our findings suggest that PCT is a sensitive and specific biomarker of infection. Giving the findings and ongoing concerns with regards to multiple antibiotic regimes, our practice will change and PCT will be requested with the 2nd CRP in cases of suspected LONS, with the aim to stop antibiotics within 24 hours on negative results prior to blood culture results.

Act Plan Do Studyis your Grown Up?”

Improving documentation of accompanying adults in the Paediatric Emergency Department

Dr Ella Burchill, Dr Richard Berg, Dr Fionnghuala Fuller Department of Paediatrics, North Middlesex University Hospital NHS Trust

Background Aims

In multiple safeguarding serious case reviews, clinicians did not document details of an adult accompanying a child who was later found to be a victim of child abuse

In recent local Child Safeguarding Practice Reviews, it has been highlighted that clinicians were not aware of private fostering arrangements due to not asking who the adult accompanying the child to PED was This was felt to be a 'missed opportunity' for identifying significant safeguarding concerns

Diagnostics

Environment

Clinicians have a duty to safeguard children and we need to know who accompanies them to hospital. We need to know who has parental responsibility for consenting to medical interventions.

Staff Survey

Primary aim:

- Achieve full documentation of accompanying adult with child by multidisciplinary colleagues 100% of the time by August 2023

Additional aims

- Improve staff awareness and understanding of parental responsibility. Improve staff confidence in asking accompanying adults who they are

Equipment People

PDSA 1: Information Gathering

discussions with colleagues around the problem, the aim and change ideas

Run Charts

Assume

PDSA 2: Information Sharing

Action: teaching to staff groups (receptionists, nurses, doctors)

PDSA 3: Teaching

PDSA 4: WhatsApp Teaching

Share the problem and the project with staff groups

P D S A

Data collection (n = 30)

Handover teaching, WhatsApp reminders Staff weekly briefing

Learning

Ø

Action: provide widespread departmental teaching

Questionnaire (21 responses) Sessions cancelled (unwell patients) Data collection (n = 30)

Promote discussion amongst paediatric doctors and link to safeguarding cases

Questionnaire to ascertain barriers

Day-to-day encouragement on shop floor

Action: Continue face to face teaching

Poor engagement.

3 responses to questionnaire (responses positive) Data collection (n = 30)

During junior doctors strikes, provide teaching on WhatsApp to doctors

P D S A

Thread of messages sent to 60 junior doctors on WhatsApp group including links to online videos

In our survey, there was a discrepancy between asking and documenting. Colleagues think they document the accompanying adult more than revealed in our audit of clinical notes.

Ø Receptionists had best documentation throughout Ø Doctors' documentation required most intervention – education sessions have been well received so far, by increasing confidence and awareness

Ø The data collection and monitoring was made more difficult as doctors and nurses use both paper and online notes.

Ø

Teaching is effective but it is difficult to involve all staff. Only 3 junior doctors responded to a questionnaire after the WhatsApp survey, however 2 trainees said that going forward they will document more.

Ø Teaching around parental responsibility is needed

Conclusions

Ø Everyone in NHS organisations have a responsibility to safeguard children.

Ø Despite disruptions with junior doctor changeover and strikes, we were able to demonstrate overall improvement and positive change to clinical practice

Ø Ongoing work is needed to continue, and sustain, improvement

Next Steps

Ø

Regular continued education: ensure attendance by including it as a mandatory part of induction, regular teaching sessions

Ø Multidisciplinary working- most teaching has been targeted at doctors, going forward we will deliver sessions to nurses and receptionists

Ø Prompt staff and families : Information sheets and posters in department

Ø

Long-term sustainable change: with a paperfree future, advocate for child safeguarding to be mandatory fields on the electronic notes system

“Who

Taking the long way to theatres: reassessing delays in trust internal transfer of acute surgical patients

Background Change implemented

During the COVID-19 pandemic, acute surgical services were adapted to a cross-site model to protect elective operation capacities at Site A

In 2021, the first audit cycle evaluated transfer times of acute surgical cases, and a new trust policy for transfer times was created, based on LAS guidelines

Aims:

1. To assess the times and delays in the transfer of an acute surgical patient from Site A to B

2. To assess the risks of patient safety

3. To evaluate the trust policy implemented in Cycle 1

4. To assess transfer proforma

Sep – Dec 2021

Data collected for 200 acute surgical patients transferred in first cycle

PLAN DO STUDY ACT

NOW

IS THE TIME FOR CHANGE

Intervention

Discussion:

March – July 2022

• New transfer protocol

• New proforma

• Education of nursing surgical team

A transfer proforma was developed to identify where the delays were occurring during transfer

Data collection

Data from the second cycle of this audit was collected from July to November 2022.

Primary outcome: cycle 2 transfer times

• 100 patients were included in the analysis

• 39 patients underwent a procedure post-transfer

July – Nov 2022

• Data collected for 100 acute surgical patients transferred in second cycle

• Transfer times deteriorated from Cycle 1

• Contributing factors include strain on LAS and ED, poor documentation and communication

• Procedures happened quicker in Cycle 2 (specifically category 1 emergency cases) – better at recognising critically unwell patients and transferring them quickly

• Poor uptake of the transfer proforma (13% uptake) –our solution to track the patient is not being utilised

• Cannot infer causation from post-op complications as we have not evaluated patient outcomes at Site B

Intervention:

ü The transfer proforma is now a mandatory standard operating procedure

ü Annual departmental audit

ü Education on surgical transfer for all staff in the MDT

ü Surgical flow coordinator role at Site A

ü Embed the transfer proforma into a mandatory electronic form

ü Trust-wide audit for all specialties

*Time to decision to transfer skewed by large number of 10 minute entries due to time to decision to transfer not being inputted on the surgical admissions proforma

Secondary outcome: patient safety

100 patients

5 deaths (all breached their transfer category time)

4 simple complications (ileus, abdominal drain insertion)

8 significant complications (sepsis, ITU admissions, relook operations)

is feedback

G. Veronesi, L. Foster-Davies, M. Lyons University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire

G. Veronesi, L. Foster-Davies, M. Lyons University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire

Feedback and healthcare

• Communication between colleagues is a key factor in determining staff performance [1]

• Exposure to incivility and rudeness is associated with adverse effects on patient outcomes [2,3]

• Appropriate feedback can help develop clinical performance and establish a positive culture [4]

• Psychological safety in the workplace is also influenced by appropriate feedback [4]

Aims

• Explore how feedback is perceived by FY2s and Consultants

• Compare views - is there congruence?

• Explore how feedback affects performance and wellbeing

Methods

• Two paired questionnaires

• FY2 Doctors (n= 24)

• Consultants (n= 54)

• Anonymous

Next steps

• Highlight findings at

• Grand Round

• QIPs

• Re-audit - expanding to a larger group of trainees and seniors to explore how the perception of feedback might change with the nature of the relationship.

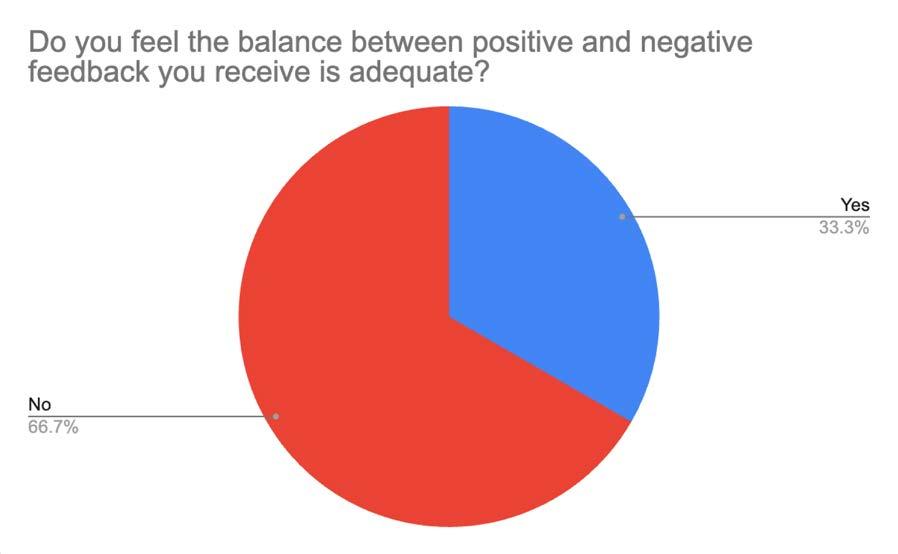

Results

FY2 Consultants

Discussion

• Perception of what defines feedback differs between the groups.

• Majority of trainees don’t believe the balance between positive and negative feedback is adequate with the opposite true for consultants.

• Trainees do not feel comfortable raising concerns in their work environment or asking questions.

• The perception of feedback regularity varies between the groups.

How

perceived within a team: a comparison between the perspectives of senior clinicians and their trainees

All Views Matter

A QIP to increase patient feedback from patients who cannot provide feedback in English

Dr Tina Dwivedi1, Dr Ashley Jefferies2, Ms Kellie Mason3 & Ms Cath Shelley4

Dr Tina Dwivedi1, Dr Ashley Jefferies2, Ms Kellie Mason3 & Ms Cath Shelley4

Background

Within the 5.1million people in the UK whose main language isn’t English, 20% cannot speak or read English well or at all 1. This equates to approximately 1 million people. Patients who do not speak English well report greater barriers to accessing healthcare, have a poorer patient experience and are more likely to be in poorer health 2. Data shows that 9 out of 10 people who speak English proficiently are in good health compared with only two thirds of people who are not 3 Within the NHS constitution 4; the guiding principles encourage promotion of health equality through services when disparities are present and encourage feedback from the public, patients and staff. The NHS Long Term Plan has placed tackling health inequalities at the heart of NHS goals for this decade5

Problem

In our current system in the sexual health service, there was a significant disparity amongst patients providing feedback on their care . We identified that non -English speaking patients had a lack of opportunity to provide any feedback at all. We have understood that this is likely reflected across the whole trust. This was supported by process mapping, which made it evident that a nonEnglish speaking patient is unable to provide feedback at any point of their clinic journey. Without obtaining patient feedback and therefore engaging with patients who access our care we cannot help to address the health inequalities that they are exposed to

Aim

Our project aim is to increase feedback from patients unable to provide feedback in English from 0% to 5% in 12 months in the sexual health service. This quality improvement project is ongoing

Intervention

Working alongside the Patient Experience team, we identified the trust’s top 6 most commonly requested languages for interpreting services. Using this data we translated feedback forms into these languages and made them available for patients accessing the sexual health service. Our four primary drivers identified through our driver diagram were: An accessible process for providing feedback; Encouraging patient engagement; Increasing staff participation and Data collection. These were used to help plan future PDSA cycles and interventions such as launching a translated promotional poster highlighting to patients who speak another language that there are translated forms available, running a staff ‘design a feedback station’ competition and flags for the patient notes to highlight to staff the need for an interpreter and feedback form.

Measurement of improvement

Our Run chart (below) shows the increasing return of feedback forms over time. This is a quantitative measure but we also have qualitative data which we have equally valued. Patients have been “grateful” that they have had the opportunity to have their voice heard. This data has already been used to feed back to the service on improvements that can be made and has been extremely useful in driving staff enthusiasm for the project. After each PDSA intervention, there was an increase in the number of forms returned on the Run chart, demonstrating a quantitative improvement.

Results of staff and patient survey from Mezzanine event

Sample of translated feedback

Arabic “Good treatment and care for patients”

Romanian “Staff are very friendly with the patients. I was very pleased with what was offered”

Polish “Very professional visit, thank you very much, a very good approach to patients”

Urdu “I have difficulty in speaking English. Due to which an Urdu interpreter was called for me and it was good for me”

Lessons Learned

Social media has been integral in raising awareness amongst staff and the community.

As part of an engagement event, staff and patients from across the trust were asked how important provision of translated feedback forms are. Whilst 100% of patients felt this was an important intervention, this was not reflected in staff engagement. Support from senior management is key to driving a change in culture; by ensuring a top down approach

Conclusion

The first step in helping to address health inequalities in patients who may not be able to speak English is to understand; to listen to patients about their ideas, concerns and expectations about their care. By addressing this need we can help improve patient safety and address health inequalities in this increasing population

1. Consultant in Sexual & Reproductive Health, Blackpool Teaching Hospitals. 2. Community Sexual & Reproductive Health Traine e, Blackpool Teaching Hospitals 3. Patient Experience Information Officer, Blackpool Teaching Hospitals 4. Nurse Consultant, Blackpool Teaching Hospitals.Improving Heart Failure Discharge Summaries

Introduction

Discharge summaries are the main communication links between hospitals and community care. High-quality discharge summaries are important in complex clinical syndromes like heart failure where effective communication between multi-disciplinary teams is necessary.

A quarter of patients who are discharged following hospitalization due to heart failure are readmitted within 30days.

A good quality heart failure summary is associated with lower 30-day readmission.

Materials and Methods

Retrospective data collection

Discharge summaries of patients in 2 cardiology wards

Sample size= 30 in each cycle

Exclusion: Patients who have stable chronic heart failure but the current admission not relating to heart failure will be exclude.

10-points checklist data were collected

Data Analysis

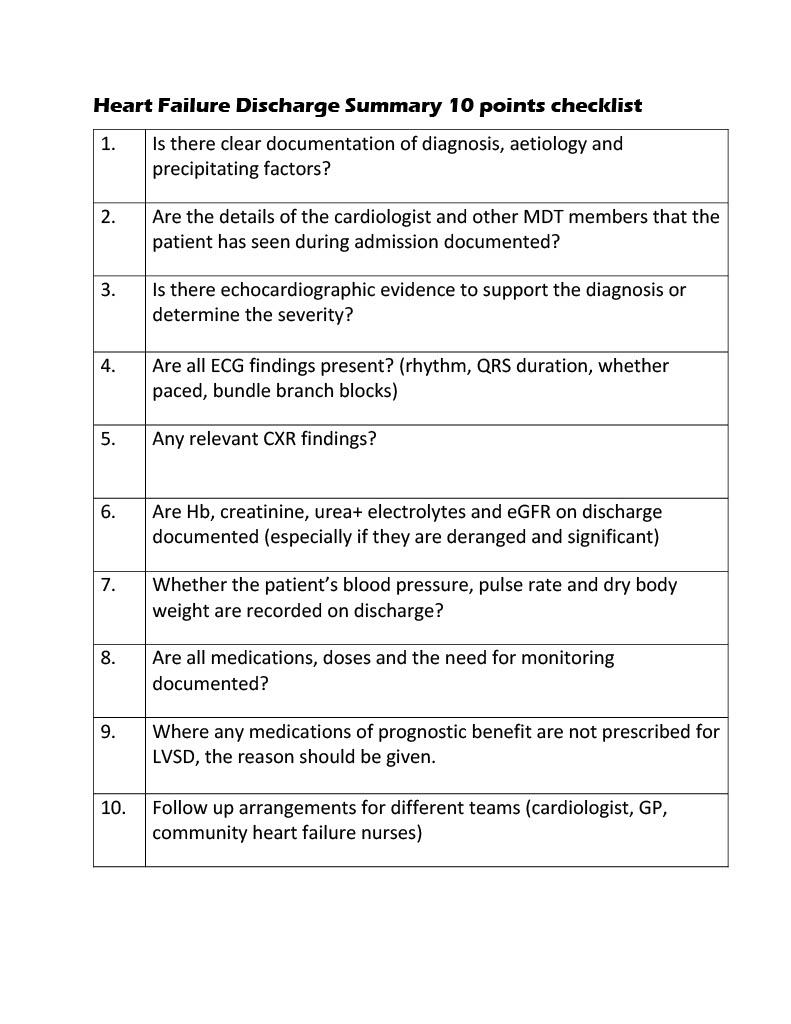

Each checklist point is scored 1mark, minimum achievable score is 0 and maximum achievable score is 10.

Mean discharge summary score= 6.4 (n=30)

1st CYCLE

Objectives

Aim to improve the quality of discharge summaries for heart failure patients in the Trust Aim to provide better communication between hospital care and primary care service

STANDARDS

There is currently no national standard for determining a good quality heart failure discharge Summary.

This version of checklist used in this QI is adapted From BJC publication of checklist of items considered necessary for inclusion in a comprehensive heart failure discharge summary.

IMPLEMENTATIONS

A simple checklist poster placed in doctors’ office_ effective and straightforward to implement_ will offer a source of reference and support to the junior doctor writing a summary

2nd CYCLE

New heart failure discharge template in Trust eDischarge software (will help to save time and manpower)

Departmental presentation about importance of heart failure discharge summaries to get junior doctors awareness

KEY SUCCESSES IDENTIFIED

Mean discharge summary score in 1st cycle= 8.3 (n=30)

Improvement of documentations noted in areas such as ECG, Echocardiogram, CXR, blood tests, patients’ dry body weight, BP and PR.

Improvement in quality of heart failure discharge summaries (as proved by mean discharge scoring points compared)

• New template system developed for heart failure discharges

• Positive feedbacks from users regarding implementations on both checklist and template

Ben Sieniewicz (Consultant Cardiologist/ Supervising Consultant) Hein Htet Zaw (IMT1/ Team leader) University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust

Ben Sieniewicz (Consultant Cardiologist/ Supervising Consultant) Hein Htet Zaw (IMT1/ Team leader) University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust