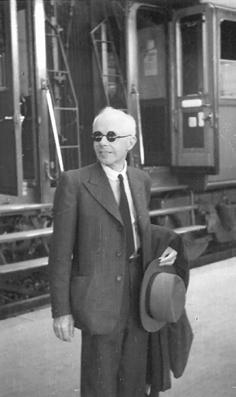

every respect.

I first played in Budapest in the 1980s at a Lieder recital with Hermann Prey, and like everyone else I was deeply impressed by the beauty of the city, especially the fact that it lies on two banks of the Danube, which makes me slightly envious as a Viennese. Unfortunately, for a long time global politics prevented people of my generation from having a sense of how close to Vienna Budapest is – closer than Salzburg, for example. Thankfully, those days are gone and my visits to Budapest have increased significantly, especially since the opening of Müpa. I’ve had the pleasure of playing in Budapest many times with Jonas Kaufmann, Diana Damrau, Michael Volle, Camilla Nylund, Piotr Beczała and others, and I’ve always found the listeners incredibly enthusiastic: you couldn’t ask for a better audience

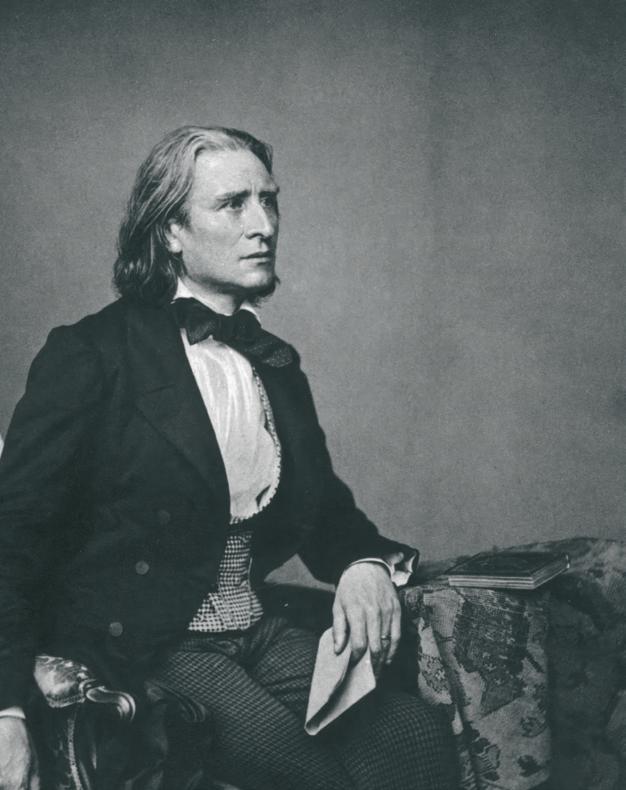

at a Lieder recital. As a chamber musician, I would play Kodály and Bartók with enthusiasm, and as a vocal accompanist I’ve become deeply convinced of my respect for the great songs of Ferenc Liszt, and almost every one of my singing partners has concurred with me. I’ve even stopped arguing with Hungarians about Liszt’s Hungarianness. Born in the Austrian Empire on Hungarian soil, he became a European artist of great stature. Bartók was right when he said that ‘Liszt’s importance for the further development of music is greater than Wagner’s.’ Diana Damrau, Jonas Kaufmann and I are looking forward to meeting the Budapest audience!

Helmut Deutsch

Performing Lieder is the ‘royal class of singing’

Bartók, the Educator

Béla Bartók Around the World

From Bach to Bartók

‘The Hungarian stage will always remain the most special for me’

‘I found the first at dawn...’ – The Loves of Béla Bartók

The Magic of the Moment, the Power of Surprise

From the Isar to the Danube An Evening with the Münchner Philharmoniker at Bartók Spring

Stradivarius and Guarneri: The World’s Most Valuable Master Violins

‘When you can see in their eyes what’s dancing across the invisible rope between the stage and the audience’

Frog Mascots and White Food for Success Artists’ Strange Habits

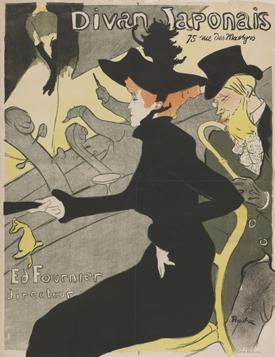

‘The poster is a banner’

It Takes Two Notes to Know Him Jan Garbarek

What If Béla Bartók Were Alive Today?

NATIONAL DANCE THEATRE

1024 Budapest, Kis Rókus utca 16–20.

KRISTÁLY SZÍNTÉR

1138 Budapest, Margitsziget

HUNGARIAN NATIONAL GALLERY

1014 Budapest, Szent György tér 2.

TOLDI MOZI

1054 Budapest, Bajcsy-Zsilinszky út 36–38.

AKVÁRIUM KLUB

1051 Budapest, Erzsébet tér 12.

LISZT ACADEMY

1061 Budapest, Liszt Ferenc tér 8.

BUDAPEST MUSIC CENTER

1093 Budapest, Mátyás utca 8.

MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS

1146 Budapest, Dózsa György út 41.

MÜPA BUDAPEST

1095 Budapest, Komor Marcell utca 1.

VÁROSLIGET –NAGYRÉT

1146 Budapest, Városliget

HOUSE OF MUSIC HUNGARY

1146 Budapest, Olof Palme sétány 3.

LUDWIG MUSEUM – MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART

1095 Budapest, Komor Marcell utca 1.

EXHIBITION

04. 04. The Art of Life

Art Nouveau Posters and Material Culture of the Hungarian Secession (1895–1914)

08. 04. Master MS and His Age

09. 04. In a Field Well-Found Artistic Practices from 25 Years of the Marcel Duchamp Prize

DANCE

05. and 06. 04. Mezőség – Mikrokosmos

10. and 11. 04. María Pagés Compañia: De Scheherezade

12. 04. Hommage à Jeszenszky Endre

JAZZ

05. 04. Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis

07. 04. Jan Garbarek Group | Trilok Gurtu

FILM

04–05. 04. Budapest Ritmo Film Days

CROSSOVER

12. 04. Magdi Rúzsa | János Balázs

13. 04. Pure Source

POPULAR MUSIC

04. 04. Arooj Aftab

04–10. 04. Akvárium Spring Terrace

CLASSICAL MUSIC

04. 04. Barnabás Kelemen | Münchner Philharmoniker

06. 04. Diana Damrau | Jonas Kaufmann | Helmut Deutsch

06. 04. Hommage à Tallér Zsófia

07. 04. Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment

10. 04. Júlia Pusker | Kammerorchester Basel

WORLD MUSIC

10–12. 04. Budapest Ritmo – world music concerts

LITERATURE

04–06. 04. Spring Margó Literary Festival

by Zoltán Farkas

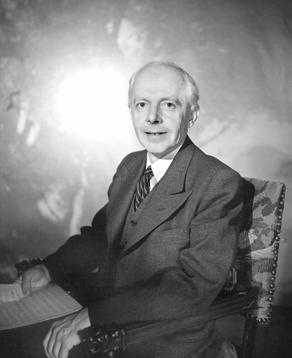

Bartók’s tours collecting folk songs took him to many settlements in the Carpathian Basin, but also to Algeria and Turkey. However, most of his travels were as a concert pianist, performing in 19 countries in Europe (including the Soviet Union) and the United States. Bartók often holidayed abroad, mostly in high mountains, and it was landscapes such as these that proved the most inspiring for him as a composer.

Bartók’s career as a concert pianist took off shortly after his academy years, both in Hungary and abroad: he first took to the stage outside his homeland in Berlin and Vienna in 1903. It was for the première of his symphonic poem Kossuth that he travelled to Manchester in February 1904, where he also took part in a performance of Liszt’s Spanish Rhapsody as a pianist. He first visited Paris in August 1905 as an entrant in the Rubinstein Competition, both as a pianist and a composer, though he did not succeed in either category. He made his debut in Spain and Portugal relatively early, in the spring of 1906, accompanying violinist Ferenc Vecsey on the piano. From 1906, as Bartók started to embark on trips to collect folk songs more regularly, he had less time to perform on stage. On 2 January 1909, he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic in the ensemble’s home city, at the request of Ferruccio Busoni – a special occasion, as this was his first and last time to appear on the podium. Switzerland (Zürich) was the eighth foreign country where Bartók gave a concert before the First World War. He performed very rarely during the war, and when he did, he appeared in Budapest and Vienna. Between December 1919 and August 1931, however, Bartók gave more than 300 concerts in 15 countries on two continents. In 1922, he visited a number of cities in Transylvania (by then part of Romania), and the same year saw him in London and Paris on his most successful foreign tour ever, performing his first sonata for violin and piano with Jelly d’Arányi to great acclaim. In Paris, composers heaping praise on the work and the performers included Ravel, Poulenc, Milhaud, Honegger, Roussel and Stravinsky. In 1923, Bartók toured Germany and

the Netherlands, and gave concerts in the United Kingdom in the spring and December. The latter concert was part of a month-long West European tour, which included performances in Paris and Geneva. In the spring of 1925, audiences in Milan, Rome, Naples and Palermo had the opportunity to hear Bartók play the piano. In the 1925/26 season, he gave another 27 performances, including in the Netherlands, Romania and Italy.

In 1926, Bartók travelled to Cologne for the world première of The Miraculous Mandarin. On 30 December 1928, he set out on what was to be his most adventurous tour, 35 days in the Soviet Union, with stops in Kharkiv, Odessa, Leningrad and Moscow. (The train ride from Odessa to Leningrad took 49 hours.) Bartók arrived back home on 3 February 1929, but barely a week later he was off again, this time to Copenhagen. It was such a harsh winter that the sea froze, causing the cancellation of one of his concerts. The first half of March saw him perform in London, Aachen, Karlsruhe and Paris, and in April he appeared in Rome. For a long time at his orchestral concerts, Bartók played the piano part of his Rhapsody No. 1, and then, following the November 1928 première, he was the soloist for his Piano Concerto No. 1. He performed the latter work on 27 occasions in all, in 19 cities.

The longest tour Bartók ever took part in lasted 95 days, between December 1927 and March 1928, during his first visit to the US. It comprised 25 concerts, and took him to the West Coast as well, to California. (Note that at that time a cross-Atlantic journey was only possible by steamship, and took at least eight days. Bartók only took an aeroplane once in his life, in January 1936, travelling from London to Rotterdam.) Until the summer of 1931, near the nadir of the Great Depression, Bartók gave numerous live and radio concerts in Germany, London, Switzerland and Austria, and visited the Iberian Peninsula for the second time. However, the economic crisis significantly reduced the number of concert invitations. The most memorable journey during this period took him to Egypt in spring 1932, where he was invited to a conference on Arabic music. From January 1933, Bartók often appeared in concert as the soloist for his Piano Concerto No. 2. He performed this work live on 29 occasions, in 23 cities.

Bartók travelled to Turkey in November 1936: in Ankara he gave a concert and lectures on folk music, while in Anatolia he collected Turkish folk music. Bartók’s trips to collect folk songs spanned a far shorter period than his concert tours. The beauty of authentic folk songs caught his attention in 1904, and he started his regular collecting tours in 1906, visiting almost 300 settlements in the Hungary of the period, in Transylvania, Upper Hungary and Transcarpathia. Bartók was on the road during almost every school holiday, including Christmas. In 1913, his wife also accompanied him to Algeria, where they spent a few weeks. In three oases around Biskra, he collected 118 cylinders’ worth of

Arabic folk music. Bartók last collected music in the territory of pre-war Hungary in 1916, as after the Treaty of Trianon he was unable to return to regions that lay outside the newly established borders.

During his last years in Hungary, Bartók travelled abroad with increasing frequency for the world premières of his works. Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta, which was commissioned by Paul Sacher, premièred in Basel in January 1937, and the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion in the same city a year later. Luxembourg was the last, twentyfirst country that Bartók visited during his tours.

Bartók’s second, 57-day tour of the United States began on 1 April 1940, and along with live concerts, also included recordings, radio concerts and readings. Bartók and his wife Ditta Pásztory arrived in New York as émigrés on 30 October 1940. During their time in the US, they primarily sought to support themselves through concerts, but only 42 public performances took place during those three and a half years, owing mainly to Bartók’s deteriorating health.

In all, Bartók performed almost 600 times in 19 European countries and the United States. He visited Algeria and Cairo, as well as Canada for visa purposes. He gave nearly half of his concerts in Hungary; abroad he performed most often in Great Britain, Germany and Romania, but he also frequently visited the Netherlands, Italy, Austria and Switzerland.

by Eszter Veronika Kiss

Scholarship has long since established the connections between the musical practice of the Baroque era and folk music traditions. One proof is the similarity in the organisation of instrumental ensembles: while the Baroque consort is preserved in the string band of folk music, the make-up of the Baroque chamber orchestra is echoed in the form of the string band complemented with woodwinds or cimbalom. Another spectacular imprint of the Baroque period is the instrumental performance style and playing technique preserved in folk music, but other musical elements have also been ‘ salvaged’ in folk music, from the Baroque practice of improvisation to its typical motifs and melodic structures. The influence was always mutual, however, since folk music in turn was an important source of inspiration for the composers of the period. Whilst the Baroque era coincided with one of the most difficult periods in Hungarian history, when the country’s division into three parts, the

Ottoman occupation and the uprisings against the Habsburg Empire hindered the development of culture, this was also when Hungarian folk music underwent its most fascinating transformation. Composed music left a clear imprint on the playing of village musicians as the music of Western Europe found its way into Hungarian aristocratic courts, where excellent musicians were employed and taught a great deal to their Hungarian counterparts. Harmonization was introduced and gained increasing ground in the church and music education in secondary schools; as a consequence, Hungarian folk music also started to change imperceptibly. Monophony, inherited from antiquity, gave way to harmonization. Wind instruments were replaced with strings – including the viola, capable of sounding chords, and the double bass, providing a functional bass voice. Thanks to these, melodies were increasingly fashioned in accordance with the functional order typical of composed music;

The Hungarian State Folk Ensemble and the Ballet Company of Győr present their show, Pure Source, at the Bartók Spring. This collaborative effort of the two dance ensembles – which has become a tradition in its own right – reveals connections between European culture and the traditions of the Carpathian Basin through Bach’s orchestral suites and Bartók’s collections of folk music.

Bach wrote his orchestral suites during his time in Leipzig. The genre itself is a fine example of unified European culture born from the interaction of different traditions. The suite is essentially a French invention, comprising a succession of French and Italian dances, naturally in stylized form. The orchestral suite is a German development of this, which was extremely popular in Bach’s time and included many courtly dances of folk origin. Of these dances, the French courante, which has a dotted rhythm, and the North Italian forlane, from Bach’s orchestral suite in C major, are coupled with the Hungarian legényes and forgatós. The polonaise from the B-minor suite, which has a strong Polish character, is counterpointed by a forgós, while the sarabande, which in Bach’s work replaces the slow movement, and which was of Moorish or Arabic origin, gaining popularity in Europe through Spain, has the vonulós as its Hungarian counterpart. The gigue, or jig, which originated in the British Isles and is to this day a popular Irish folk dance, is exemplified by a movement from Bach’s suite in D major, together with its Hungarian parallel, the ugrós (jumping) dance, together illustrating the lasting unity of European culture.

the strophic structure of folk songs changed, and by the end of the Baroque period, a new style of Hungarian folk song had emerged, whose formal structure and scales were entirely similar to those of similar West European folk songs. Along with folk music, folk dance followed a similar path, with partner dances becoming the most popular. These were greatly influenced by courtly dances, which, in turn, had folk roots: thus a perpetual cycle emerged. During the 18th century, Hungarian folk music became European while at once preserving its ancient heritage, thus becoming a melting pot of East and West. All the more so as the period of Johann Sebastian Bach saw parts of Hungary repopulated by large numbers of Germans, and the new arrivals brought with them a culture of which Bach’s art was an integral part. These processes were not, of course, exclusive to Hungary, and parallels can be found in Norway, Denmark, Scotland, Ireland and the English-speaking world.

The second part of the programme draws on Béla Bartók’s collections from the Carpathian Basin, offering an insight into the dances of national minorities in Hungary: Romanians, Roma, Serbs, Ruthenians and Slovaks. Bartók was the first to understand the organic unity of folk tradition in the Carpathian Basin, the building blocks of which are provided by the musical and dance heritage of each of the peoples living here. Lasting coexistence, interaction and the resultant mutually enriching, close cultural ties naturally brought together the peoples of the Carpathian Basin before the First World War. Just as Bach’s suites testify to a common European musical language that draws on the music and dances of these different peoples, so there emerged, in the course of centuries, a shared mother tongue of music and dance in the Carpathian Basin. Bartók used this to create his own compositional idiom, a unique sound that is both Hungarian and European, and based on a synthesis of folk tradition and modern music.

The production is directed by Csaba Káel, and choreographed by Gábor Mihályi, György Ágfalvi and László Velekei. The music is selected and edited by László Gőz, and complemented with two extensive compositions by Kornél Fekete-Kovács, an Overture and a Finale. The performance also features singer Eszter Pál.

13 April | 7.30 pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall PURE SOURCE

An evening of arts based on the works of Bach and Bartók

interview by Nikolett Vermes

How does Béla Bartók’s Violin Concerto No. 1 sound on a 1714 Stradivarius? What does it take for a musician to prepare as well as possible for a concert? Finally, after so many international tours, how does it feel to play in front of a Hungarian audience again? We asked the talented, world-renowned Hungarian violinist Júlia Pusker about these things and her upcoming performance in Hungary as she prepares for a special evening with the acclaimed Kammerorchester Basel.

You have won numerous professional accolades, including fifth place at the 2019 Queen Elisabeth Violin Competition in Brussels. You were the only Hungarian entrant to achieve a prominent place among the world’s most distinguished artists. How has this result affected your career?

For me, this is an extremely important milestone, which still has a big impact on my career. Thanks to this competition, I have gained international recognition, countless invitations and collaborations abroad, which have shaped me considerably. I think this competition has influenced my outlook, my dedication to music and my relationship to the stage. The timing was a bit unfortunate, however, as the COVID epidemic broke out shortly afterwards, causing the cancellation of many of the important performing opportunities I had secured as a result of the competition. I tried to make up for some of them after the pandemic, but eighty percent of the planned concerts could not take place. Those were trying months for everyone, I think, but they gave me time to relax and reflect on my priorities.

You may not have had any rest since then. You probably spend all your free time practising. This may change from time to time. During secondary school and university, I did practise a lot, up to six hours a day. I felt this was necessary to properly improve my technique and learn all that was necessary. Since my mid-20s, I’ve needed a bit less practice, but daily intensive work has remained a priority. Today, at 33, I see that the energy I invested earlier has paid off, so I can prepare for concerts in a different way than before. The technical experience allows me to realize my musical ideas more easily on the instrument and to get closer to a deeper understanding of the works. As for resting, it’s also essential to achieve a physical and mental balance, which is often a real challenge in today’s fast-paced world. To the extent that it’s possible, I try to keep the importance of this in mind.

As for your career, it’s worth pointing out that although you began your advanced training at the Liszt Academy, you continued your studies at the Royal Academy of Music in London. This isn’t something we see very often, since it’s extremely difficult to get into the Liszt Academy in the first place, and those who do are reluctant to leave. Why the change?

There were several important factors behind my decision. For five years prior to my university studies at the Liszt Academy, I attended the institution’s School for Exceptional Young Talents. It was during these years that the tutor in my main subject, István Kertész, came up with the idea that my development would benefit from some experience abroad. It was also at this time that I met György Pauk, who was giving a masterclass at the Bartók Seminar in Szombathely. After the first lesson, he spoke to my father personally about how he thought London would be the best place for me to develop. This was a defining moment, as Pauk was an extraordinary artist and it was his words that ultimately cemented my decision. This was how I transferred from the Liszt Academy to the Royal Academy of Music in London, and I was delighted not only to be admitted but to be awarded a full scholarship. This made it possible to continue my musical studies in London as a student of Pauk, and to develop along the lines of Hungarian musical traditions and values despite the geographical distance. The experiences abroad, the new outlook I gained there and the foundations I brought from the Hungarian school have together shaped me into the person I am today.

Let’s now talk about your instrument, which is a special piece. What is there to know about it?

I currently play a 1714 Stradivarius, which belonged to György Pauk. I’m very honoured that, before his death, he gave me the use of the instrument he played until the end of his career. The violin has priceless sentimental value for me. Every time I pick it up, I can feel the spirit and musical legacy of

Professor Pauk. He passed away only a few months ago, so the future of the instrument is uncertain, but I’m grateful every day that I’ve been able to play it.

What is quite certain is that you can be heard at the Liszt Academy on 10 April, where you’ll be accompanied by the famous Kammerorchester Basel. To be honest, I’m already very excited at the thought of the concert because it has special significance in many ways. Firstly, we’ll be performing music by Béla Bartók, which is very close to me. I feel it’s my duty to programme his works in as many places as possible, thus contributing to the promotion of his oeuvre. The piece we’ll be playing, the Violin Concerto No. 1, reflects a very sensitive period of Bartók’s life, and it tells a deeply felt story. This concerto in two movements, which was intended for and dedicated to Hungarian violinist Stefi Geyer, is a true confession of love, full of emotion and passion. The second thing making this concert special is that the Kammerorchester Basel is truly renowned around the world, and although I haven’t had the pleasure of performing with them before, I look forward to an exciting collaboration. Thirdly, it’s a special pleasure for me to return to the Grand Hall of the Liszt Academy, a venue that holds an important place in

my heart. This was where I first heard performers who went on to have a great influence on me, and it’s thanks to them, among others, that I can now stand on that stage as a violinist myself.

It’s no exaggeration to say that you’ve performed all over the world. You’re abroad as we make this interview, and you have 2026 dates in your concert calendar. Do you make a conscious effort to perform in Hungary?

As a rule, I always play wherever I’m invited, but I’m lucky to play in Hungary often enough. The presence and energy of the Hungarian audience give me an emotional boost every time. That said, it may surprise you that nowhere else do I get the kind of stage fright as before concerts at home. Although I’ve performed in the world’s most famous concert halls, the Hungarian stage will always remain the most special for me.

10 April | 7.30 pm

Liszt Academy – Grand Hall

JÚLIA PUSKER | KAMMERORCHESTER BASEL

Conductor: Izabelė Jankauskaitė

THE HOUSE OF MUSIC AWAITS YOU IN 2025!

Concerts

Exhibitions

Educational programs

Pop Cultural Club Library

Sound Dome 360 screenings

Creative Sound Space

zenehaza.hu/en

by Márton Karczag

Lately, the dividing line between the tabloid press and musicologists seems to be getting wider. Journalists serving the former generally cite a few paragraphs of superficial anecdotes that can be scrolled on their phones, while researchers spend hundreds of pages trying to unravel the mysteries of an artist’s oeuvre. And while both approaches have a real basis today, the everyday consumer of classical music prefers to walk the happy medium. Whereas once music was mostly self-explanatory for the listener – who was much closer in time and cultural background to the world in which it was created – today, with changing musical consumption habits, the shrinking time spent on it and the almost unlimited amount of audio material available, it has become essential to have background information that can serve as a reference point to put a given work into context. It is always up to the listener to decide whether this context is important to them or whether, on the contrary, it acts as a constraint on their imagination. What is certain, however, is that while it is becoming more and more common to publicly examine the life of a composer, to (re) interpret the relationship between the private person and their oeuvre, Hungarian scholars still seem to be trying to protect the lives of our most famous composers with a veil of modesty. There has been no effort to reconcile the Ferenc Erkel who so movingly portrayed the pain of Melinda or Erzsébet Szilágyi

with the husband who ‘exiled’ his wife to Gyula, nor has there been complex scrutiny of the love life of a hypersensitive Béla Bartók in light of his oeuvre.

A thick tome, published a few months ago,* aims to fill the latter blank spot, offering detailed insights into the young Bartók’s hitherto unexplored love life – as well as his painful disappointment. The letters published in the volume, previously hidden from public view, reveal the importance to him of his encounter with Stefi Geyer (1888–1956). Even in the 1980s, in presenting Bartók’s oeuvre, the story of the beautiful violinist was eclipsed by the composer’s relationship to pianist Etelka Freund, who was a close friend until they both married, almost at the same time.

The composer met Geyer at the opening of the Academy of Music’s new building on Liszt Ferenc tér, in May 1907. Bartók was twenty-six at the time, Geyer only nineteen. It is little wonder she caught his interest: she was at once young and a mature artist, an unmarried Catholic girl and a soul opening up in her art. She was nonetheless the more sober of the two, realizing in the course of the one and a half years of their intense friendship that she wanted a different man.

* Helga Váradi, László Vikárius: Geyer Stefi hegedűművész életútja. Levelezése Bartók Bélával (The Life of Violinist Stefi Geyer. Her Correspondence with Béla Bartók); Budapest: Balassi Kiadó, 2024

Twenty years passed before they met again, in Switzerland, and after a series of concerts together, they slowly developed a friendship. Just how important he was to her is shown by the fact that it was only on her deathbed that Geyer gave her close friend Paul Sacher, the renowned Swiss conductor, the treasured Bartók letters and the manuscript of his youthful Violin Concerto, which was thought to have been lost, and which will be performed by Júlia Pusker at the Liszt Academy on 10 April 2025. ‘My confession | to Stefi | from what were still happy days. | Though even they were only half-happy...,’ reads the poignant dedication from the composer to his muse.

In November 1909, Bartók took refuge from the disappointment of love in the bonds of marriage. Márta Ziegler (1893–1967) was still a little girl when he taught her, and they met again when he was on one of his folk song collection tours of Transylvania. Their marriage lasted thirteen years, and she was the one to create the first peaceful home for Bartók, in Rákoshegy. A skilled musician herself, Ziegler selflessly served her husband, and eventually even made the sacrifice of letting him marry his piano pupil Ditta Pásztory.

The time of Bartók’s first marriage encompasses the bulk of his composing oeuvre, including Two Pictures, Allegro Barbaro, Bluebeard’s Castle, The Wooden Prince and The Miraculous Mandarin. All

three works for the stage (the works of the composer that have the most tangible content) testify to the difficulties – indeed, the seeming hopelessness – of dialogue between Man and Woman, this being the order that prevails in Bartók’s work. In his symphonic works the composer always hid the initials of the object of his current desire (Felice Fábián, Klára Gombossy or Jelly d'Arányi), and in the case of Stefi Geyer, even a leitmotif that recurs in several works, while the figures of the Prince, Bluebeard (‘When a wound is opened’) and the Mandarin offer a glimpse into the depths of the male soul.

Bartók’s second wife, Edith Pásztory (1903–1982) –whom the composer himself ‘christened’ Ditta – was admitted to the Academy of Music in 1922, where her professor soon recognized her special talent. Though the composer was married (and she a fiancée), and despite an age difference of twenty-two years, their affair evolved into a marriage by the summer of 1923, and it was to last for the rest of the composer’s life.

As a pianist, Pásztory matured into Bartók’s musical companion – occupying the same orbit, rather than being eclipsed by him as Ziegler had been – and she remained his companion when, in 1940, he chose to go into exile in the United States. Of Bartók’s three great loves, she had the greatest responsibility: returning home in 1946, as a living legend, she was to preserve the memory of her brilliant husband for herself and the outside world for decades.

interview by Anna Takács-Koltay

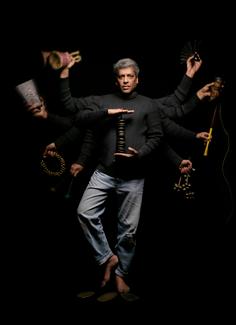

How can you maintain classical values and also create something new and innovative, providing your audience with an experience that’s far from ordinary with the power of surprise? Intuition, small vibrations and dynamics all come into play on 12 April, in Müpa Budapest’s Béla Bartók National Concert Hall.

János, you’re one of those rare classical musicians who love other genres and seek out opportunities to rendezvous with them. When did Magdi’s work catch your attention?

János Balázs: Already as a child, I listened to the greats of jazz and pop alongside the legends of classical music, because at home we’d listen to lighter music, Béla Szakcsi Lakatos and the great bar pianists. It followed that I’d also watch the talent show where Magdi endeared herself to the whole nation. What I found special was her elemental force and her timbre. All this was 20 years ago, but even then I was confident I’d come into contact with this exceptional artistic talent.

You first worked together in 2019, at the Cziffra Festival. Magdi, coming from the pop genre, how did you find a common musical language with János?

Magdi Rúzsa: On the one hand, at home I’ve been listening only to classical music for some time now. On the other hand, I study a lot. With Éva Bátori, my vocal tutor, we started to rebuild my singing skills from the ground up by going back to the basics. Thanks to years of work with her, my singing now has the technical foundations of a classical vocalist.

J.B.: I have an incredible amount of respect for Magdi for doing this, and as a successful artist with a fan base at the peak of her career who takes

singing classes, she’s an example that many people should follow. This is a huge thing.

It’s not necessarily a given that two musicians who are successful and respected in their respective fields can work well together on stage. What does it take for two artists from different genres to work well together?

J.B.: The crossing of genres doesn’t mean that an artist from any given genre can create works in any other. Crossover doesn’t mean that if you put any two people together, good things will come of it. It’s far from inevitable, even if both are artists of high quality. You need similar temperaments, philosophies of life and art that can meet in improvisation. The piano parts of the songs I perform with Magdi are 100 per cent improvised. M.R.: That’s right, and this goes against all that takes place at my concerts. At a Magdi Rúzsa concert, everything has its predetermined place and timing. With János, I still have the reference points, but there’s also the possibility of improvisation, which generates a strange tension and a positive adrenaline rush. Not to mention that there are few people who make you feel safe on stage. It’s enough to look at János and he can signal me with his body language, I understand perfectly what he wants at a given moment. And he feels the same way about

me, so it’s like holding the rope he’s guiding. It’s safe to say that I’ve probably never felt as free on stage with anyone as with him.

The basis and essence of improvisation is to express the vibes of a given moment on the stage, which cannot be practised at rehearsals. How do you prepare for the performance?

J.B.: These are well-known songs, already written. What changes, every time, is their quality, their musical arrangements, the intros, the bridges, the solos, the rhythm and the dynamics. And this is where one artist must really influence or inspire the other. We need a kind of trust between us that cannot be practised. You either have this kind of trust between two people or you don’t.

M.R.: This is chemistry; something strange, intangible. I’ve worked with some fantastic people, great artists, and I’ve had my own band for 20 years, and yet it was János who showed me, for the first time in my life, that it’s also possible to do it this way. I feel I can lean back and let go, and he’d find some way to catch my fall. I think a lot about how this is possible, but there are no words to explain it.

J.B.: There’s an invisible bond. I often tell Magdi to close her eyes and trust her feelings, and then she’ll know when to enter. Trust is what gives these concerts their beauty, while their unplanned nature is responsible for their difficulty. Intuition, small vibrations, exchanged glances, inflections, stepping up the dynamic: all these matter. This unexpected quality is what gives us something extra that allows us to get rid of the compulsion to fit in. It’s important to always have music and a message in your soul. That, of course, makes it necessary for you to keep practising at home, to do your utmost to hone your technical skills, and then, when we get together, there’s a piquancy and sense of novelty. Much of it comes into being at the performance, in the magic of the moment, and what emerges is a distillation of our knowledge and emotions.

J.B.: We’ll certainly perform arrangements of folk songs, and there will be French chansons and old Hungarian film songs. In addition, we’ll also completely transform the well-known Magdi Rúzsa songs. When performed with a single piano, a song has a completely different atmosphere. This instrument can give it something different, sometimes it can ennoble it. The piano can lend a whole new meaning to a radio hit, as it allows you to immerse yourself in the lyrics.

M.R.: During our first concert in 2019, János made me realise that although I come from a pop background, these old music hall songs and chansons suit my register and timbre best. I’ve been researching these types of songs ever since, because János and I have been preparing for a long time to surprise everyone with a joint album!

J.B.: The main message of the concert is that you can turn something traditional into something innovative

and new, while keeping the classical values. That’s an experience for the audience that’s out of the ordinary, that you can’t expect or prepare for, and so it has the power of surprise. None of the musical solutions are an end in themselves: we’re guided solely by our inner musical compass as we perform the songs.

It seems like you get along well not only professionally, in improvisation, but also as human beings.

J.B.: Magdi is extremely reliable. I’ve worked with a lot of people over the last 10 years, and that’s not a quality you can take for granted in every artist. Whatever she does and says has energy and a positive vibe to it. Also, we have children roughly the same age, though I have one and she has three.

M.R.: There are people who have similar values, whose heart beats to the same rhythm. With János, it all started on the stage, that’s where our friendship began. I have found him and his wife a very special little team, so we like to spend time together and bring the kids together as well.

J.B.: It’s very difficult for a woman to build a family and a career at the same time, especially with triplets, especially with such a successful career. The triplets have not halted or derailed her career, which is a fantastic achievement. That’s another proof of the stamina she has, the faith she has in music and in life in general.

In many of your shows, you intentionally blur generic boundaries. Is that in part informed by the desire to do away with the elitism of classical music – whether real or perceived – and free it from its own ivory tower? Is that the idea behind the joint concert with Magdi?

J.B.: My model is György Cziffra. He helped me to live my life with a much more open mind, a broader horizon and artistic attitude. As a classical musician, I’m convinced that my collaboration with pop musicians has enriched me. I don’t want young people today to think of the classical music scene as oldfashioned or outdated. I want to motivate them to go to concerts of classical music. And pop stars help me in that. Magdi is one of the most extraordinary among them. I think it’s important to open up to each other, and to make music accessible for all. If the two ranks don’t meet, don’t communicate, then like it or not they’ll be jealous of each other; classical musicians will say pop musicians are undertrained, while the other side will say classical musicians live in a bubble. It was not my idea to fuse genres: consider Pavarotti, who sang duets with pop stars, or Ferenc Liszt, who played with the greats of his age. We should be aware of our contemporaries and the world around us, and we should get to know each other through artistic adventures. The joint concert with Magdi is meant to serve this very purpose.

12 April | 8 pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall

MAGDI RÚZSA | JÁNOS BALÁZS

The Freedom of Music

AN EVENING WITH THE MÜNCHNER

PHILHARMONIKER AT BARTÓK SPRING

by Szabolcs Molnár

The inauguration of the Isarphilharmonie, the new concert hall of the Münchner Philharmoniker (Munich Philharmonic), was a special moment in the modern history of the ensemble. One of Europe’s newest concert venues was opened on 8 October 2021, naturally with a concert by the Münchner Philharmoniker.

Interestingly, a concert hall also played a key role in the birth of the orchestra. Franz Kaim (1856–1935), a versatile man who was active in music and literature, started to present concerts in the early 1890s, when he launched piano, Lieder and chamber music recitals to popularize the products of his family’s piano factory. As the concerts became very popular, Kaim established a symphony orchestra in 1893, which by 1895 needed its own concert hall. In 1905, the KaimSaal was rechristened the Tonhalle, and continued to be considered the most important concert venue in the Bavarian capital – until 1944, when it was destroyed in a bombing raid. The one-time in-house orchestra, the Kaim Orchester, was first renamed the Orchester des Münchener Konzertvereins (Orchestra of the Munich Concert Society) before it became the Münchner Philharmoniker.

Very quickly, the orchestra rose to the ranks of the best German ensembles and just as quickly found its own, distinctive voice, repertoire and mission, becoming an institution always sensitive to new developments, holding itself to the highest artistic standards, and making its services available to all strata of society. In 1898, Felix Weingartner became music director, and he regularly took the orchestra abroad. The early phase of the ensemble was marked by world premières of Mahler’s Symphonies No. 4 and No. 8 (‘ Symphony of a Thousand’ ), both conducted by the composer, as well as his orchestral work The Song of the Earth, which was presented posthumously by Bruno Walter.

In addition to its tradition of Mahler, the Münchner Philharmoniker is also a key orchestra of the Bruckner cult, and for good reason. Austrian conductor Ferdinand Löwe, a student of Bruckner’s who often directed the orchestra in the 1890s (and was its principal conductor between 1908 and 1914), laid the foundations of a tradition whose influence can be felt to this day, thanks also to the epochal work of Oswald Kabasta (1938–1944) and Sergiu Celibidache (1979–1996).

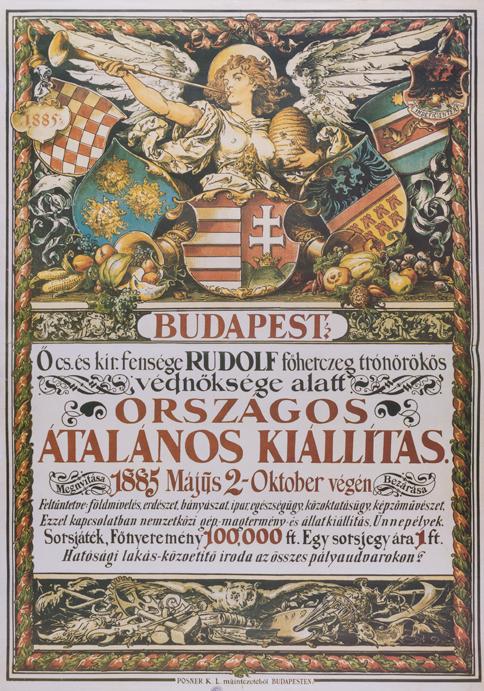

For the past century or more, the Munich orchestra has functioned as the flagship of German cultural diplomacy – regardless of its political and ideological orientation – and it was in particularly tense situations that it gave its first guest performances in Hungary in the summer of 1934, in Debrecen and Szeged. ‘One hundred musicians of the Münchner Philharmoniker and three hundred singers of the Munich Teachers’ Choir, six hundred people in all, together with those who accompanied them, arrived in Szeged shortly after Friday noon on a special train,’ reported the daily Budapesti Hírlap ‘At six in the evening, the orchestra

gave a large-scale concert in the Votive Church to an eager audience, with choirmaster Franz Adam conducting. The programme included Mozart’s Requiem , Bruckner’s Te Deum and Verdi’s Dies Irae .’

The orchestra was placed on a war footing during the Second World War, so that the musicians could perform their military service behind their music stands, and not on the battlefield. The war had already begun when the orchestra gave its first concert in Budapest, in late January 1940. The music director, the Austrian Oswald Kabasta, conducted a long programme, featuring Richard Strauss’s symphonic poem Don Juan, Schubert’s Symphony No. 3, Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5, and Ernő Dohnányi’s Symphonic Minutes. During this period, Kabasta made several radio recordings with the orchestra, which deserve a re-listen because they sound very modern even today. The same recordings substantiate the claims made in a review of the 1940 Budapest concert: ‘It is clear that this orchestra is not only practising, but also learning. The splendid synchrony of the strings and the sounds of the winds, clearly intoned even in the high registers, lent a crystalline purity to the items of the programme. There is an admirable discipline in the orchestra, thanks to which the great precision produces real art, and not some clockwork music. Kabasta, the music director, is a great conductor. His temperament creates glowing tension around him, which captivates the orchestra and audience alike.’

After the Second World War, the orchestra found what was to be its temporary home – but, in fact, became its long-term residence – in Munich’s Herkulessaal, before moving into the Gasteig Philharmonie in 1985. The cultural centre has recently been closed for a major reconstruction and it is uncertain when it will be reopened.

Recent decades have seen such great conductors at the helm of the orchestra as James Levine, Christian Thielemann, Zubin Mehta, Lorin Maazel and Valery Gergiev, while it is currently headed by the young Israeli pianist and conductor Lahav Shani (b. 1989). Currently acting chief conductor, Shani will take over as music director from September 2026.

Shani and the ensemble embarked on a tour of Spain at the beginning of 2025, visiting Madrid, Valencia, Alicante and the Canary Islands, with violinist Hilary Hahn as the featured artist. In March and April, the Münchner Philharmoniker will tour the world under the baton of Lithuania’s Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla, with Vilde Frang as guest soloist. The featured artist at the Budapest concert will be Barnabás Kelemen.

4 April | 7.30 pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall BARNABÁS KELEMEN

| MÜNCHNER PHILHARMONIKER

Conductor: Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla

by Zsuzsanna Könyves-Tóth

Most people know that violins, even beginners’ instruments, are not cheap. And then there are some rarities that count as art treasures of astonishingly high value. What makes these special pieces so expensive? Can they even be used or do they belong in a museum? We explore these questions by looking at the world’s five most valuable violins, as well as highlighting two Hungarian examples.

There are many factors that affect the value of a violin, and some of these go far beyond its quality and practical worth. One of the most important is the maker of the violin and their historical significance. Of the five most valuable violins, four were made in Antonio Stradivari’s workshop and one in that of Giuseppe Guarneri del Gesù. Among Hungarians, Júlia Pusker plays an instrument by the former master, and Barnabás Kelemen one by the latter. Both violin makers lived in Cremona, the Italian birthplace of the modern violin, and were active in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Thanks in part to an extraordinarily long life (he died at 93), Stradivari made around one thousand violins, of which five to six hundred have survived, in varying states of repair. Guarneri, by contrast, died relatively young at age 46, and less than two hundred of his masterpieces are known to be extant. Stradivarius violins typically have a powerful, bright sound, and elegant, symmetrical bodies, while the sound of Guarneri violins is darker, more robust, and their shape less regular. Besides its maker, an instrument owes its price to various other conditions as well, of course: how rare and old the piece is, who its previous owners were, what historically significant performance it is

associated with, its condition and the quality of its sound. Many of these instruments are so valuable that even the most famous violinists cannot afford to buy them. As a result, most specimens are usually owned by wealthy collectors, states or institutions. These masterpieces of instrument making are sometimes exhibited in museums, while some are hidden from the public eye; often, however, they become prizes or donations in the form of loans to the most outstanding violinists of our time. It is no mere altruism on the part of a collector to lend a highly valuable violin, since the fame of the artist who uses it adds to its value. As Barnabás Kelemen said of his Guarneri violin: ‘The playing of the artists who use them comes to inhabit the violins, and in this way they become more and more refined and mature. The wood absorbs the delicate vibrations and transforms and matures over the centuries.’ A particular violin may be named after the person who owned it the longest, but a famous artist may also become its eponym.

Let us now take a look at the violins that are currently the most valuable in the world. (It is important to note that there is no official list, since the precise value is hard to estimate unless an instrument has recently been put up for auction.)

‘JOACHIM–MA’ STRADIVARIUS – $11.3 MILLION

This violin from 1714 went on auction this February, and was sold for a price that secured it a place in the top five. It is named after two of its previous owners, world-famous Hungarian violinist József Joachim and its most recent proprietor, Chinese violinist Si-hon Ma. Ma donated the violin to the New England Conservatory, and stipulated that it could only be sold if the proceeds were used for scholarships, which is exactly what the institution has promised.

‘DA VINCI, EX-SEIDEL’ STRADIVARIUS –$15.34 MILLION

Another violin that has two bynames left Stradivari’s workshop in 1714. Russian violinist Toscha Seidel played this instrument on the soundtrack of several iconic Hollywood films (including The Wizard of Oz). It was baptized ‘Da Vinci’ by Caressa & Français, the Paris-based dealers who sold it in 1923. It fetched the second-highest price ever paid for a Stradivarius when it was purchased by a Japanese collector in 2022.

‘LADY BLUNT’ STRADIVARIUS – $15.9 MILLION

The violin to sell for the highest known price ever is a 1721 Stradivarius, purchased by an unnamed collector in 2011. This masterpiece was named after a former owner, Lady Anne Blunt, the granddaughter of British Romantic poet Lord Byron. It has survived in fantastic condition because throughout much of its history its owners were collectors, rather than musicians.

‘VIEUXTEMPS’ GUARNERI – CA. $16 MILLION

The most valuable Guarneri was named after a 19th-century owner, and has been played by such legends as Menuhin, Perlman and Zukerman. Made the same year as the Kochánski, this masterpiece is in great condition despite many years of use. The violin was purchased in 2012 by an anonymous collector for an undisclosed sum that was rumoured to be in excess of the Lady Blunt’s price. The instrument is on lifetime loan to American violinist Anne Akiko Meyers.

‘MESSIAH’ STRADIVARIUS – CA. $20 MILLION

This 1716 Stradivarius is considered to be the only instrument by the Cremona master that has survived in virtually new condition. It even owes its name to its ‘ underutilization’ : when Luigi Tarisio, the famous 19th-century collector and trader of violins, was once talking about this exceptional Stradivarius, a violinist exclaimed: ‘Really, Mister Tarisio, your violin is like the Messiah of the Jews: one always expects him but he never appears.’ A later owner bequeathed it to the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford for preservation as ‘a yardstick for future violin makers to learn from.’

Most of the violins mentioned are played very rarely or hardly at all – which is understandable, as this is how their exceptional condition can be maintained. Fortunately, there are still quite a few superb violins around that can find their way into good hands: most violin virtuosos, in fact, play on ‘ borrowed’ instruments. Barnabás Kelemen is a case in point, to whom barely a year ago the Hungarian state granted the right to use the Guarneri once played by János Rolla. Also recently, Júlia Pusker was given access to György Pauk’s 1714 ‘Massart’ Stradivarius, as the retired – and sadly since deceased – artist did not want his master violin to lie around unused. These two outstanding masterpieces of the luthier’s art can be heard live in Budapest in April.

4 APRIL | 8 PM

House of Music Hungary – Concert Hall

Although as a point of reference everyone notes the presence of her song ‘ Mohabbat’ on Barack Obama’s playlist, this only covers a tiny, albeit important, slice of Arooj Aftab’s exciting career. Nor is it saying much that she is a Grammy Award-winning singer, composer and producer; what is truly telling is the variety of audiences that accept and love her, whether she appears at Coachella, Glastonbury, Primavera Sound Barcelona, the Roskilde Festival or the Montreal Jazz Festival. Yet Aftab’s work should not be reduced to the generalisation that whatever is beautiful and emotional is simple: her ethereal songs fuse the Middle Eastern traditions of Sufi music and Hindustani classical music with jazz and a subtle backdrop of electronica and Urdu poetry. Raised in Pakistan and teaching herself the guitar, Aftab grew up in an environment where women had limited opportunities, so she first studied online at Boston’s Berklee College of Music, before attending the university in person, graduating in 2010 with a degree in jazz composition and music production/sound engineering. The seven-time Grammy Awardnominated artist made history in 2022 by becoming the first Pakistani woman to win a Grammy.

5 APRIL | 8 PM Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall

JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER ORCHESTRA WITH WYNTON MARSALIS

The story of the Marsalis family is a multi-generational musical marvel, in which the stunning career of Wynton Marsalis plays a prominent part. Born in 1961, Wynton chose the trumpet, and at a very young age became an ambassador not only of jazz but of classical music, whose abiding motto is ‘all jazz is modern. We attempt to embrace both the legacy and the future of jazz so the history of jazz is present in what is currently being played.’ The Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra (JLCO), as one of Marsalis’s current ventures, is made up of fifteen outstanding instrumental soloists and big band musicians who are driven by the aforementioned motto: they play classic evergreens, original compositions, and even rarities and forgotten works. The featured guest of the evening is Hungarian trumpeter Balázs Szalóky, who was inspired by the JLCO to found his own band.

5 AND 6 APRIL | 7 PM

Müpa Budapest – Festival Theatre

Thanks to Béla Bartók, we are now aware of the special cultural significance of the Mezőség region in Transylvania, whose ethnographic, musical and literary traditions are always worth returning to when looking to create a new production. Bartók’s piano cycle Mikrokosmos and the songs from Mezőség that inspired the composer provide the musical background to this performance that is equally contemporary and authentic, blending theatrical and dance elements, and featuring actors of the Forte Company, dancers of the Corvinus Közgáz Folk Dance Ensemble, and students of the University of Theatre and Film Arts. The production fuses authentic dance and musical heritage with contemporary theatre that holds both language and movement at its focus; an abstract visual representation of peasant culture fused with the movements of Bartók’s work for piano. The performance is a visual report, a staged form of sociography and a piece of drama that seeks to find points of alignment, spiritual security and human stability for renewal and rebirth in an age of cultural decay.

7 APRIL | 7.30 PM

Liszt Academy – Grand Hall

Perhaps the highlight of the Bartók Spring is the guest performance at the Liszt Academy of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, one of the leading period instrument ensembles of our time. Formed in 1986, the British orchestra takes its name from the Age of Enlightenment at the end of the 18th century, a period that forms the heart of its repertoire. Interestingly, the orchestra, which features distinguished soloists at its concerts, does not have a principal conductor. On this occasion, the St Matthew Passion, an important piece in Johann Sebastian Bach’s oeuvre and a work always topical at Easter, will be conducted by Jonathan Cohen, who is also a renowned cellist and harpsichordist, and highly regarded both as a chamber musician and soloist. With Arcangelo, the ensemble he founded in 2010, Cohen has appeared in the world’s most prestigious concert halls, and is a regular contributor to the performances of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

interview by Gerda Seres

Diana Damrau and Jonas Kaufmann, without a doubt, make a great duo on stage, and as they have already proven to the Budapest audience with their previous Lieder recital, are able to reveal the beauty of this intimate genre with fascinating subtlety and variety.

Photo: Jiyang Chen

In an earlier interview, Jonas Kaufmann said that singing Lieder gives him the opportunity to show subtleties because, unlike opera, you don't work with big brushstrokes. What are the special challenges in the songs of Strauss and Mahler?

Jonas Kaufmann: What I find particularly exciting about them is that both Strauss and Mahler, the creators of such lavish, huge orchestral works, achieved a similarly fascinating richness and variety of colours in a minimalist space, with just a voice and a piano. Few other composers can compete with that – Ferenc Liszt is a likely contender. Compared to the classical song repertoire, especially Schubert and Schumann, Strauss’s songs require a more powerful, lush sound, as is also required for his operas. Strauss’s songs are basically miniature operas, and as in operas like Der Rosenkavalier and Ariadne auf Naxos, his songs demand the whole spectrum from the singer, from the finest piano to dramatic intensity. Helmut Deutsch awakened my love for this repertoire: he was my teacher for Lieder singing at the Munich Hochschule für Musik, and in that context we worked on Strauss’s songs in a master class in Garmisch-Partenkirchen with Hans Hotter, the great Lieder singer and famous Wotan. Diana Damrau: Richard Strauss’s music speaks directly to my heart, especially his songs. I have been connected to his work since my early studies. There is beauty in it, virtuosity and drive, depth, philosophy, as well as a lot of humour. I have just debuted as the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier at the Staatsoper in Berlin. It is, in my opinion, really the ultimate role in the soprano repertoire: for the voice there is virtuosity, parlando and great lyrical passages, as well as situations of exposure as in songs, like the so called Zeit-Monolog. There is everything in this role –musically, vocally and in terms of acting.

Mahler’s music is quite different.

D.D.: With Mahler’s wonderful music it was a bit different for me and my coloratura soprano to find an immediate connection. I love his incredible symphonic works – especially because you can find singers as ‘additional instruments’ in them – as well as the whole range of his songwriting, like the ballads, the war songs, but also the simple little treasures of the Wunderhorn. The latter requires an extremely precise reading from the singer and the pianist to reach the complete picture. It is more intellectual and it sometimes does not really carry and move the singer’s voice, I think, so you have to do a lot of ‘additional work.’

J.K.: Mahler’s music is also very close to my heart, it touches me very much, especially in its melancholy and in what we call Weltschmerz. That’s why I tended to choose the sad, melancholic pieces for our recitals. To be honest, I haven’t got the key to his humorous songs. It’s different with Strauss: I also find his humorous songs very attractive, as they have wit and charm.

The songs in the concert were inspired by poems by legendary and lesser-known poets. How important do you think storytelling and lyrics are in songs?

D.D.: Unlike all the musical instruments, the singer has words! And words communicate meaning, feelings and moods. There are a lot of different ways to communicate in Lieder: you can become the lyrical speaker, the person who is talking and thinking, or you can keep your distance, observe and comment and play different characters.

J.K.: At a recital, you have to tell some twenty different short stories, using all the colours and nuances at your disposal. This is just as true for the singer as it is for the pianist. Compared with an opera performance, a completely different level of concentration and fine-tuning is required. That’s why I have always described Lieder singing as the ‘ royal class of singing.’

When you sang Hugo Wolf's Italienisches Liederbuch at Müpa Budapest, you also made room for some acting, which was delightful. Do you think you’ll be able to do that again this time?

J.K.: Not as consistently as we did with the Italian Songbook and the love songs by Schumann and Brahms, which were more or less ‘ scenes from a relationship.’ This time there is no such dramaturgy, since the content is far too diverse. But we will act where it is appropriate. The audience likes this kind of action, much more than having us just stand there and sing.

D.D.: I love our Lied duo and the possibilities it offers. Every programme we have performed together was different in this respect. This time we will also have some moments alone on stage, especially with the Mahler songs. We will present a more diverse range of songwriting styles. While Jonas is singing excerpts from the famous Rückert-Lieder, I am in charge of the completely different Wunderhorn Lieder, whose texts come from folk songs. These are simple and sometimes fun stories, handed down through tradition from people to people. These songs are also very different as regards the music writing. When performing with a partner on the concert podium, Lieder allow for the deepest connection, with subtle expression, like close-ups in movies.

Can the audience’s attention and reactions inspire you?

J.K.: Absolutely! Feedback from the audience is incredibly important. Any singer knows that very well, but most of us will only have realized how important it is during the pandemic. We suddenly had to sing in front of empty houses and the only audience was the camera team. And when you’ve given your all, and you get a short ‘ Thank you!’ from the recording manager, that's when you really realize how much you need the audience.

D.D: Music is, above all, a living art. Though it gets deep into your soul and is experienced personally, at concerts the connection with the musicians, the vibes and the atmosphere of the venue give it another dimension. As a performer, it is wonderful to feel and see how people are there with you and the music, how they go on the journey with you and react in the moment. At such times, we all forget about the world around us and are somehow connected in a better place. Sometimes it feels like meditating in the arms of this wonderful art. The laughs, the applause, as well as the tears and pure enjoyment on the part of the audience are very uplifting and inspiring; you always want more of it and want to give more to them. All this makes me very grateful.

How do you find the right balance between the voice, the lyrics and the piano?

D.D.: Well, first of all, it is the rehearsing. But from both sides a deep understanding of poetry, its context and the deep connection of the word and the music is essential. This is not only the singers’ work. In Lieder, the accompaniment and the voice are equal partners, and each has to contribute and explore all their skills. But the basis of all this is the emotion.

J.K.: I’m very lucky that Helmut Deutsch has been my partner on the piano since I was a student. And when you’ve known each other as long as we have, when you’ve played so many evenings together, then a lot of things come naturally during rehearsals, you don’t have to fiddle around for long. Such intimacy is an incredible gift, for which I can’t be grateful enough.

You’ve collaborated together on the opera stage and in recitals on numerous occasions. Diana has said that it’s wonderful to work together, but similarly great to laugh together. What is the secret behind this excellent harmony?

J.K.: I think with us ‘ the chemistry is right,’ as they say. I met Diana as a beginner when I was a guest in Würzburg as Tamino, and she sang the role of Papagena on roller skates. Since then we’ve performed together many times, I really appreciate her and look forward to our next recital tour. Similar to a partner on the opera stage, trust here is a very important ingredient. You need to know that all we try is for the general success, not to put yourself in the limelight.

D.D.: We both search for the total essence in the moment; feeling, listening and reacting to each other and not intruding on the wonderful pieces of art our composers and poets have given us. There is no place for the ego.

6 April | 7.30 pm

Müpa Budapest – Béla Bartók National Concert Hall

DIANA DAMRAU | JONAS KAUFMANN | HELMUT DEUTSCH

by Zoltán Farkas

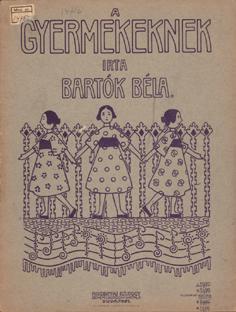

Bartók did not like to teach, but he was a passionate educator of those close to him. He composed a significant repertoire for young people intent on learning the piano, as well as for violinists and choirs. He wrote the lion’s share of Mikrokosmos for his younger son, Peter.

‘One of his characteristics was that he was always teaching...,’ said Márta Ziegler, Bartók’s first wife, in beginning her recollections of the composer. Correspondence and personal memoirs eloquently testify to Bartók’s passion for teaching those closest to him: his loves, his relatives, his own sons. In light of this, it may seem curious that he did not really like teaching in an official context, although it was an important source of his livelihood until 1934. Even though he had taught private lessons since his secondary school days, and was then appointed piano teacher at the Academy of Music in Budapest in 1907, he found teaching a chore and never taught composition. He would refer to the Academy of Music as ‘ an ugly place’ to his son Péter, who was all the more surprised when he first stepped into the beautiful Art Nouveau building. If the obligation of teaching piano did not enthuse Bartók, he was all the more dedicated to music education as a composer. Recalling the genesis of For Children, the first piano cycle he wrote with pedagogical intent, he said: ‘At the very beginning of my career as a composer I had the idea of writing easy pieces for piano students. This idea came from my experience as a piano teacher; I always felt that the material available, especially for beginners, had no real musical value, with the exception of a very few works [...] so I myself tried to write easy piano pieces.’ The inspiration for Bartók was not only to improve children’s piano technique, but to allow them to discover the beauty of real folk music early in their studies. As he explained, ‘I wrote For Children [...] to introduce children who are learning to play the piano to the simple and non-romantic beauties of folk music.’ While the first two volumes of For Children (1908–09) contain arrangements of Hungarian folk songs, Volumes 3 and 4 (1909–11) draw mostly on the Slovak folk songs

the composer himself collected. Bartók considered it ideal for the performer of these short piano pieces to also be familiar with the lyrics of the folk songs. Bartók himself was happy to perform some of the pieces from For Children, while József Szigeti and Tivadar Országh made arrangements for violin and piano. Erich Doflein, a German composer and teacher planning a new violin study method, approached Bartók for violin transcriptions of selected pieces from For Children, for two violins. The composer, however, replied that he would prefer to write new pieces. In the spring of 1931, while working on his Piano Concerto No. 2, he sent over the new compositions in four instalments.

What gives 44 Duos its special significance is that it became the last of his large instrumental cycles based on arrangements of folk music –a compelling fruit of the encounter of Bartók’s most mature style and folk music. Doflein was pleased to notice that Bartók’s style had changed since For Children, noting: ‘…after more thorough study I was filled with an increasing satisfaction on the recognition of how the change that has occurred in your way of writing since you wrote your earlier easy piano pieces also shows its effect in these new easy folk song arrangements. And what inner necessity justifies every harsh sound, every clash of melody. The pieces naturally demand a very fine ear.’ ‘ Harsh sound’ and ‘ clash of melody’ refer to the exquisite polyphony of the duos. Bartók’s sensitive ear analyses and grasps the essence of the arranged folk song, from which he also develops the material for the ‘ accompaniment.’ As László Dobszay put it in an essay, the folk song is practically absorbed in the course of the arrangement. As in the case of the later Mikrokosmos, the most difficult and virtuosic of the 44 Duos were the first to be written – as great pieces fit for the concert stage – and the easier ones were finished subsequently.

The next pedagogical series, 27 Choruses for Children’s and Female Voices (colloquially, ‘ for equal voices’ ) was not commissioned; at most, it was encouraged by a good friend, Zoltán Kodály. In 1934, Bartók was, at his own request, exempted from teaching at the Academy of Music, working instead on cataloguing folk songs at the request of the Academy of Sciences. During this work, he also came across collections of folk poetry that did not contain melodies. This became the source of texts for his cycle of choruses, and when he set them to music he relied on his own invention and did not use any folk melodies. The structure is just as exquisite, the sensitive polyphony of the meeting of the parts just as delightful as in the duos. Bartók himself was proud of these choruses: after a piano recital at the Academy of Music, he invited the conductor Zoltán Vásárhelyi to his flat on Csalán Street and played his newly completed choruses on piano in one sitting. Kodály was again succinct in his praise: ‘Hungarian children do not yet know that at Christmas 1936 they received a gift for life. But that is something that is known by all those who want to lead Hungarian children into a world where the air is cleaner, the sky is bluer, the sun is warmer. Those who have long wished Bartók would join their ranks.’ Bartók’s last, and largest, pedagogical work was Mikrokosmos, comprising 153 pieces in six volumes. The earliest movements were written in 1926, during Bartók’s ‘piano year,’ though most were completed between summer 1932 and 1939. There were personal

motivations this time: ‘In 1933, my son Péter pleaded with us to teach him the piano. I had a daring idea and undertook this unaccustomed task myself. Other than vocal and technical exercises, the child was given only pieces from Mikrokosmos to play. I hope they proved useful for him, but I must admit that this experiment taught me a great deal, too.’ According to Péter Bartók, most of the short pieces were committed to paper by his father during the piano lessons.

The title of Mikrokosmos, said the composer, ‘may be interpreted as a series of pieces in many different styles, representing a small world, or it may be interpreted as a world, a musical world for little ones, for children.’ Very few of the pieces in Mikrokosmos are arrangements of original folk songs. And yet the inspiration of folk music can be found time and again in the melodies, which are reminiscent of the four-line structure of folk song verses; in the scales of folk music; or in the use of rhythms and metres previously unknown to composed music.

Mikrokosmos is much more than a great piano tutor: it is a rich repository of Bartók’s compositional methods and the building blocks of his music. Furthermore, Volumes 4–6 contain numerous pieces that are worthy of concert performance, with superb atmospheric pieces (Bagpipe Music, Boating, Merry Andrew, From the Diary of a Fly), Bartók’s poetic take on night music (Minor Seconds, Major Sevenths), and virtuosic tasks (Ostinato, Six Dances in Bulgarian Rhythm). Bartók himself liked to perform them, having played 64 of the 153 pieces in concert.

Bartók: Gyermekeknek [For Children] –Title page of the first edition (Mus. pr.) 14.752. HNMPCC –

‘WHEN YOU CAN SEE IN THEIR EYES WHAT’S DANCING ACROSS THE INVISIBLE ROPE BETWEEN THE STAGE AND THE AUDIENCE’

interview

by Vera Szabadkai

This year marks the tenth edition of Budapest Ritmo, one of the capital’s most diverse world music festivals, which takes its audience on a global tour every year. On 10 April, the musical voyage of discovery kicks off with such names as Altın Gün, Canadian-Russian diva Michelle Gurevich, and Irish folk duo The Breath. How did an event for a few hundred people turn into an internationally acknowledged world music festival? How are Tuareg rebels, southern Italian trance dance or Anatolian psychedelic rock received in Budapest? We asked the festival’s programme director Balázs Weyer about the ten years of Ritmo and preparations for the event in 2025.

I know it’s hard to choose, but can you describe a favourite moment at Ritmo?

Balázs Weyer: On almost every day of the festival, there’s a moment when you can feel something special is happening, when the atmosphere, the density of the air in the hall is changing. On such occasions, I find myself watching not the stage, but the audience, because what I enjoy most is seeing the euphoria, the astonishment or the tears in their eyes, depending on which of our internal organs has been hit by the moment. My favourite moments are those when you can see in their eyes what’s dancing across the invisible rope between the stage and the audience.

Ritmo is one of the capital’s most diverse festivals, both in terms of musical styles and performers. How is the line-up created?

I’m adding names to a long, long list throughout the year. It includes acts I see here and there, ones we haven’t been able to invite for years but we haven’t given up on, as well as ones I’ve been recommended or I remembered as we go along: I put them all on this list. Now that the 2025 line-up is complete, names are being added to the 2026 list.

It’s an important rule that we only invite people we’ve seen perform live, because the main mission is to try to share with the audience experiences that we’ve already had ourselves: like a tour guide who has walked the route before, knows where and when to stop, which sections to hurry through, where the best photo points are, or where to be careful.

How that long list ends up as a programme is most akin to alchemy, or in more modern terms, is part of the experience design. We keep the whole process in mind: what experiences and impressions a visitor will have, what sensations will be offered to them in one room, and what they’ll experience in another. It’s important how you start the day, where you plan to peak, where you arrive at the end. But this isn’t a science, but rather a question of feelings and empathy.

Whether the proportions are right will turn out on the spot: the line-up at the tenth Ritmo ranges from Indonesia to Canada, from chanson to trance dance. In addition to big names like Altın Gün and Michelle Gurevich, we also offer ultra-niche acts.

Have you ever had an audience react very differently to a performer than you expected?

In general, this doesn’t happen very often, but as we don’t usually bring mainstream world stars, there’s a risk to every choice we make. So we ask the audience to trust us. What we can promise is that no one will like everything, while we’re sure that everyone will discover something or someone that will stay with them for a long time, and that’s no small thing. Now, the fact that this actually works is a pleasant surprise to me every time.

What extra stuff have you prepared for the tenth edition?

Every year is a bit different, and that may be truer on this tenth occasion. The most important thing is a big free concert in City Park on the first day of the festival with Fatoumata Diawara, who we’ve tried to bring every year since Budapest Ritmo started, but who’s been touring mostly in the US during this season. We both really wanted this to happen and now it finally will. Before that, the House of Music Hungary will host a showcase concert by three emerging artists.

This year, for the first time, there will be a separate event called Ritmo Film Days: the film programme has started to grow too big and has already strained the framework of Ritmo. So this event will take place on the first weekend of the Bartók Spring, with more and more interesting films than before, some of which will be related to the performers. Here we aim at the intersection of music and film fans, as film can be used to bring in new perspectives, social contexts and longer stories, such as the documentary portraits of Carlos Santana, Joan Baez and Gogol Bordello, as well as Mali Blues , which I recommend to everyone. The special feature of this year’s Film Days is

Áron Mátyássy’s new film, Nefelejcs (Forget-MeNot), which takes a fresh look at the genre of the imitation folk song (nóta).

We’ll keep our established traditions, such as cooperation between foreign and Hungarian artists, once-in-a-lifetime experiences, and the inclusion of record releases in the programme. This year, for example, Canzoniere Grecanico Salentino will start their 50th anniversary tour in our country. The concert in Budapest will be an unusual one, as it will feature the Roma percussionist Máté A. Kovács.

There’s a professional part of Ritmo that the public knows less about. Can you give a sense of the importance of that, your achievements over the ten years?

Although the conference is not something that strikes the public, for us the two are less separate. The question of what kinds of performers we can invite goes largely back to the fact that over the past ten years Budapest Ritmo has become a meeting place for professionals from East and West. This is primarily because Central and East European and Balkan networks in this genre did not exist before we started to convene them, and by now they’ve become a very important and visible part of the European market. The symbolic focal point of this is Budapest Ritmo. What this means in practice is that we have the concerts in the evening, while in the daytime we hold conferences, present projects in the region, and mentor groups. If I look at the map of Eastern Europe, I can see it in terms of the things contributed by words said or encounters made at Budapest Ritmo, from Žilina to Kragujevac, and from Kraków to Sofia.

10–12 April

City Park | House of Music Hungary | Akvárium Klub BUDAPEST RITMO

April 2025

MASTER SQUARE – INTERACTIVE PLAYGROUND FOR THE FAMILY

THE FIRE TOWER OF GYŐR IS MOVING!

GYŐR PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA

AMARO DUHO

4–6 APRIL

Kristály Színtér

You must read! This is the simple but straightforward motto of the Margó Literary Festival, under which authors and readers can once again take part in new adventures. In 2025, the spring events of Margó are hosted by the Kristály Színtér cultural centre, where we’ll celebrate great literary achievements (György Spiró’s Captivity and Péter Nádas’s Parallel Stories were published 20 years ago), attend classic book launches, enjoy concerts and film premières, get to know the authors of a new generation, and witness the intrusion of technology into everyday life. How did filmstrips and literature connect seventy years ago? The present will, of course, reflect on the past, and artificial intelligence cannot be left unmentioned, which will give rise to many associations, such as the interpretation of poetic thoughts or the dialogue between writers and AI.

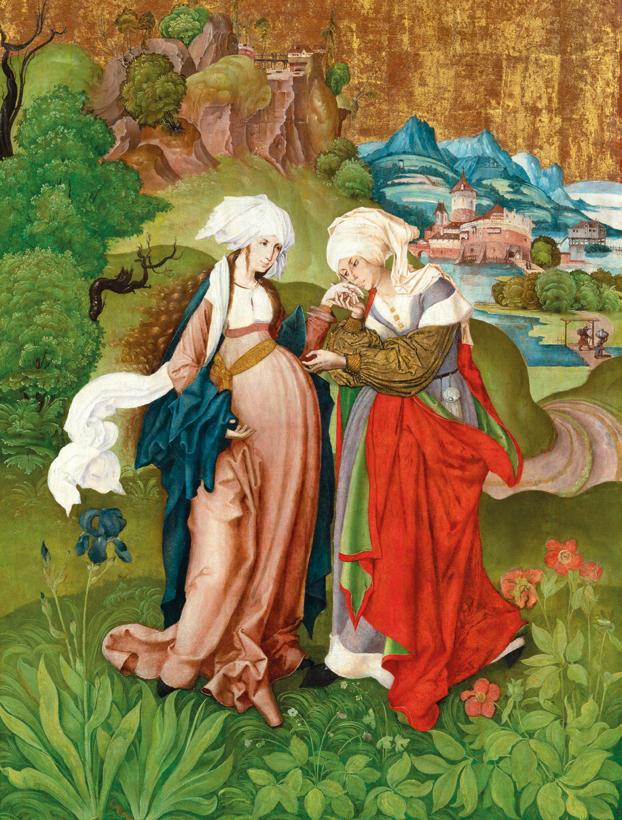

8 APRIL | 2 PM Museum of Fine Arts

MASTER MS AND HIS AGE